This chapter outlines the different strategies that guide and frame the Irish vision for policy development in the civil service and public sector and presents an overview of the institutional framework for government reform and policy development. It highlights current strengths in policy development and concludes with an assessment of how current reform initiatives could be enhanced, leveraged and joined up to improve the overall policy development system.

Strengthening Policy Development in the Public Sector in Ireland

1. Ireland’s Policy Development Vision and Landscape

Abstract

A number of strategies guide and frame the Irish vision for policy development in the civil service and in the public sector more broadly.

Civil Service Renewal 2030 (Government of Ireland, 2014[1]) is an ambitious strategy that builds on the strengths of the Civil Service and the achievements under the previous Civil Service Renewal Plan and related reform programmes. It is underpinned by a commitment to achieve the vision to be an “innovative, professional and agile civil service that improves the lives of the people of Ireland through excellence in service delivery and strategic policy development”. The strategy is informed by the findings of the Civil Service Employee Engagement Surveys; learnings from the response to the COVID-19 pandemic; the overall strategic context in which the civil service operates; experience with previous reform programmes; and the lessons learned from the Organisational Capability Review Programme. The strategy was developed to ensure that the civil service can build on its strengths to respond to today’s environment, address future challenges and continue to deliver for the government and the people. It has three core themes:

delivering evidence-informed policy and services

harnessing digital technology and embedding innovation

building the civil service workforce, workplace and organisation of the future.

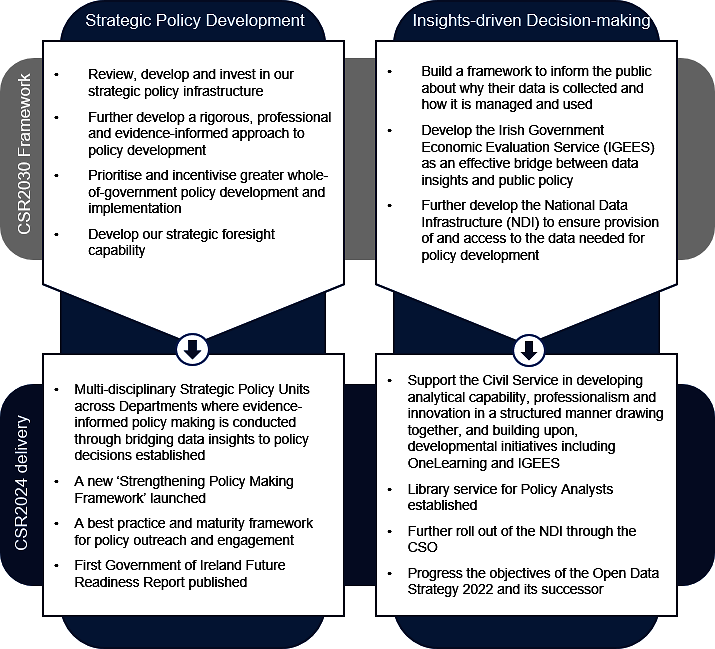

Civil Service Renewal 2030 was developed collaboratively and is expected to also be delivered collaboratively. The strategy is implemented through a series of three-year action plans. The first of these action plans, Civil Service Renewal 2024 (CSR2024), “aims to ensure that the Civil Service makes better use of data, further develops analytical skills and capacity of the Civil Service and invests in our policy development infrastructure” (see Figure 1.1) (Government of Ireland, 2014[1]). It sets out actions related to both strategic policy development and insights-driven decision making to develop and leverage data as an input to policy. The plan refers to a “Policy Development Infrastructure” designed to “facilitate a joined-up approach to evidence informed policy development through Strategic Policy Units and stakeholder engagement”.

Figure 1.1. Civil Service Renewal 2024: Action Plan to deliver the Civil Service Renewal 2030 Strategy

Source: Adapted from (Republic of Ireland, 2014[2]), Civil Service Renewal 2024: Action Plan to deliver the Civil Service Renewal 2030 Strategy.

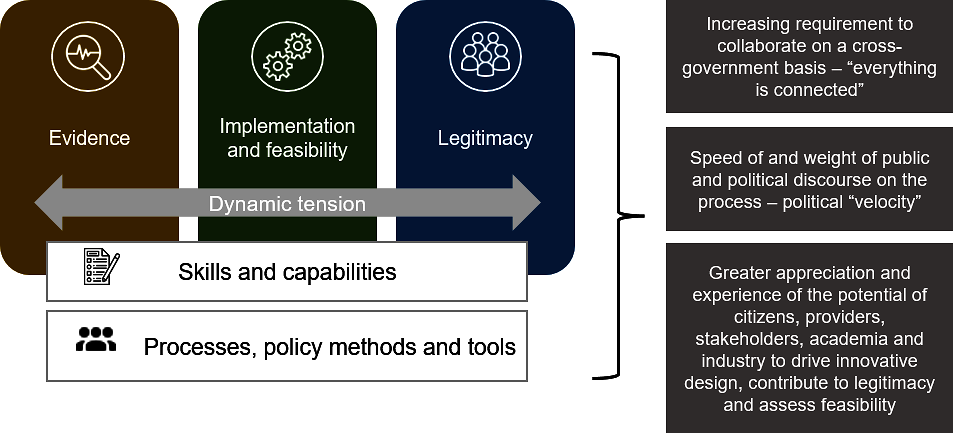

The report “Strengthening Policy Making in the Civil Service” takes a unified and joined-up approach to policy development. The report is structured around the interrelated pillars of evidence, implementation and feasibility, and legitimacy (see Figure 1.2) and offers guidance on enablers and best practices for policy development. Central to the “Strengthening Policy Making in the Civil Service” report is that the three pillars are mutually reinforcing. For example, the Civil Service would find it difficult to gather and analyse and share data if there isn’t sufficient legitimacy; feasibility depends in part of the availability of good data; and legitimacy depends, in part, on government being able to show they can deliver. As this stage, however, although the framework has been endorsed by the CSMB, it has not yet been launched or shared widely across the civil service. The implementation of the framework is pending the development of a strategic, structured and well-supported plan to ensure the promulgation, capacity-building and embedding of the approaches, skills and competences it proposes.

Figure 1.2. Civil Service Management Board framework “Strengthening Policy Making in the Civil Service”

Source: Adapted from figure provided by the Department of the Taoiseach, Government of Ireland.

The Public Service Reform Plan aims to make the work of the public service more transparent, decision making more accountable and service delivery more effective. Our Public Service 2020 (Government of Ireland, 2019[3]) is the most recent framework for reform. It is the government’s framework for development and innovation in the public service and contains 18 actions, including new initiatives and actions focused on building on reforms already in place. There are three pillars: Delivering for Our Public, Innovating for Our Future, and Developing Our People and Organisations.

The implementation of these strategies is guided by a rich institutional framework, support structures and co-ordination bodies. In relation to government reform and policy development, the following play an important role:

The government establishes cabinet committees to assist in addressing government-wide policy issues, such as COVID-19, environment and climate change, housing, and accommodation and support for Ukrainian refugees. Cabinet committees, of which there are currently 11 in place (Government of Ireland, 2022[4]), comprise two or more members of government and may also include the attorney general and ministers of state.

The Department of the Taoiseach, in particular its Social Policy and Public Service Reform Division (Government of Ireland, 2021[5]), supports the Taoiseach on social policy and public service reform and related matters, including the work of a number of cabinet committees; assists with the Civil Service Renewal programme, including providing the secretariat to the Civil Service Management Board; and has the departmental oversight role for the National Economic and Social Council.

The goal of the Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform (DPENDR) is to serve the public interest through sound governance of public expenditure and by leading and enabling reform across the civil and public service. The DPENDR Transformation Division (Government of Ireland, 1997[6]) is responsible for developing, driving, co-ordinating, supporting and evaluating the government’s programme of Public Service Reform and Innovation and Civil Service Renewal. It is also responsible for legislative and other government reform commitments to promote and support open, accountable and transparent government. The implementation of Our Public Service 2020 (Government of Ireland, 2019[3]) is a key priority, as is the development of a culture of evaluation across the public service. An important part of the work of the Transformation Division in driving reform is implementing the Civil Service Renewal Plan and supporting the Civil Service Management Board, which has collective responsibility for delivering the plan. It also has responsibility for managing the Civil Service wide Employee Engagement Surveys, the Annual Civil Service Excellence Awards and for the Organisational Capability Review Programme.

The Civil Service Management Board (CSMB) oversees the implementation of the priorities set out in the Civil Service Renewal Plan. The CSMB is made up of all secretaries general and heads of offices and is chaired by the Secretary General to the Government.

To promote shared ownership of the Public Service Reform Plan across the public service, both civil service and public service leaders and managers are directly involved in the public service reform governance structures. The Public Service Leadership Board (Government of Ireland, n.d.[7]), with Secretary General/CEO-level participation drawn from the Civil Service Management Board and representatives from a broad range of public service organisations, provides overall leadership and is supported by the Public Service Management Group (PSMG). PSMG membership comprises assistant secretaries and equivalents from across the civil and public service.

Enabling institutions and bodies within the civil service include the following:

The Central Statistics Office (CSO) is Ireland's national statistical office, and its role is to impartially collect, analyse and make available statistics about Ireland’s people, society and economy. CSO’s mandate under the Statistics Act 1993 (Government of Ireland, 1993[8]) is "[t]he collection, compilation, extraction and dissemination for statistical purposes of information relating to economic, social and general activities and conditions in the State". At the national level, CSO official statistics inform decision making across a range of areas including construction, health, welfare, the environment, and the economy. The CSO offers, for instance, access to a “Data Room” for policymakers and researchers, to meet the data needs of policy departments. At the European level, the CSO provides an accurate picture of Ireland’s economic and social performance and enables comparisons between Ireland and other countries. The CSO is also responsible for co-ordinating the official statistics of other public authorities.

The National Data Infrastructure (NDI) Champions Group, chaired by the CSO with representatives from all departments and agencies with high-value data, monitors and promotes coverage of unique identifiers across public sector data holdings. The Group identifies gaps in the coverage of unique identifiers while also acknowledging the value of the NDI in meeting known and emerging data needs in the public service.

The Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service (IGEES) (Government of Ireland, 2022[9]) is an integrated cross-government network, also anchored in DPENDR, to enhance the role of economics and value-for-money analysis in public policy development. Created in 2012, IGEES demonstrates the strong commitment of the government to a high and consistent standard of policy evaluation and economic analysis throughout the Irish civil service. In that regard, IGEES has an important role to play in the reform and strengthening of the civil service and in supporting the government in progressing major cross-cutting policy challenges such as economic growth, social inclusion, service delivery and policy design. IGEES goals include: (1) to develop a professional economic and evaluation service that will provide high standards of economic and policy analysis to assist the government decision making process; (2) to ensure the application of established best practices in policy evaluation in support of better value for money and more effective policy and programme interventions by state authorities; (3) to facilitate more open policy dialogue with academia, external specialists and stakeholders across the broad socio-economic spectrum. The IGEES network comprises approximately 200 economists and public analysts working within departments across the civil service to instil a culture of and expertise in policy development across the government.

OneLearning, the Irish Civil Service Learning and Development Centre, is situated in the Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform. It is responsible for the provision of learning and development, which supports the improvement of skills and competencies across the civil service. The Centre seeks to enable a high-performing workforce by encouraging new skills and behaviours, facilitating ongoing professional development and ensuring that staff have access to learning and development when required. It was established in September 2017, with new courses becoming available on an incremental basis over the years.

The Office of the Government Chief Information Officer (OGCIO), anchored in DPENDR, has the leadership role for the digital agenda across government. OGCIO works in collaboration with organisations across the civil and public service and has a growing involvement in supporting sectoral digital development such as increased cyber security, the Contact Tracing App and the COVID-19 vaccination roll-out. OGCIO also leads the implementation of a number of strategies, legislation and European Union Regulations.

The Government Information Service (GIS) is based in the Department of the Taoiseach and works to foster strong collaboration and co-ordination among press and communication officials in other government departments and agencies. It co-ordinates, supports, and amplifies communication around key government priorities such as Housing for All, Brexit, the Shared Island initiative, Climate Action, COVID-19 and Ukraine. It also supports and encourages capacity-building in the area of communication and engagement across the civil and public service (including through the Government Communications Network) and manages the “Government of Ireland” identity and unified web presence of gov.ie.

Policy development also benefits from a number of prominent independent institutions. They include the following:

The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) produces independent, high-quality research with the objective of informing policies that support economic sustainability and promote social progress. To this end, the ESRI brings together leading experts from different disciplines who collaborate across a number of research initiatives, focusing on a broad range of topics ranging from macroeconomics to taxation, education and social inclusion.

The National Economic and Social Council (NESC) was established in 1973 and advises the Taoiseach on strategic policy issues relating to sustainable economic, social and environmental development in Ireland. The members of the NESC are representatives of business and employers’ organisations, trade unions, agricultural and farming organisations, community and voluntary organisations, and environmental organisations, as well as heads of government departments and independent experts. The composition of the NESC plays an important and unique role in bringing different perspectives from civil society together with government. This helps the NESC to analyse the challenges facing Irish society and to develop a shared understanding among its members of how to tackle them. The Secretary General of the Department of the Taoiseach chairs the NESC meetings. At each meeting, the NESC discusses reports drafted by its secretariat. The NESC decides its work programme on a three-year basis, with inputs from the Department of the Taoiseach.

The Institute of Public Administration (IPA) is Ireland’s public service development agency focused exclusively on public sector development. It delivers its service through:

education and training – building people’s capability to meet challenges

direct consultancy – solving problems and helping plan, and shape the future

research and publishing – understanding what needs to be done and making these findings readily available

international projects and co-operation.

Building on current strengths in policy development

The policy development ecosystem in Ireland, as evidenced by its institutional framework, is well developed. The interviews and survey undertaken for this assessment report highlighted a number of ongoing good practices in the country’s policy development process, including in relation to:

collaborative approaches for policy development across departments and agencies

stakeholder engagement (both ad hoc and permanent/institutionalised)

organisational culture for evidence-informed policy-making development

policy co-ordination at the departmental level.

Some of the evidence of good practices has emerged during times of crisis. The response to the global financial crisis was mentioned as an example of how evidence and lessons learned helped Ireland be better prepared in facing the COVID-19 pandemic. Civil servants interviewed for this project felt that the COVID-19 response showed the system working at its best, with various parts of the system coming together to address the common challenge and displaying agility, responsiveness and resilience. The COVID-19 response also led to significant progress in the area of digitalisation. In particular, digital connectivity served to fast-track delivery of elements of the Civil Service Renewal programme, including in relation to digitalisation and remote working. For both crises, interviewees mentioned the following as key to this success: strong central leadership and direction, a joined-up political-administrative interface (the political and official sides working as one) supported by whole-of-government structures for providing decision making advice and for monitoring and reporting progress, alongside the use of “special” cabinet committees in tackling complex, cross-cutting policy issues (such as dealing with the challenges associated with Ukrainian refugees).

“Back in 2008 with the financial crash, unemployment escalated rapidly in Ireland. Government brought an action plan for jobs which cut across all departments. It was driven by the centre, by the prime minister. There was a real drive and focus on delivering the actions. Unemployment lowered in a relatively short period.”

“I think our reaction to the pandemic showed that we had a policy system that was able to come up with proposals to deal with this unprecedented crisis in a very short order. And I think it probably did so more effectively than a lot of other countries in terms of protecting public health, but also in terms of protecting the economy.”

Interviews and surveys report numerous examples of sound policy processes for the preparation of this assessment report, including in areas such as well-being (A Wellbeing Approach for Ireland), a strategy for children (First 5), health policies (National Cancer Strategy), rural development policy (Our Rural Future), employment (Action Plan for Jobs), housing (Housing for All) and water policies (River Basin Management). A number of good tools and methods were also highlighted, for instance, in the evaluation at the Department for Social Protection and the Environmental Protection Agency Research Programme. All these demonstrate where the civil service has successfully developed and delivered effective policy. Some span across different departments and policy areas, highlighting the capability for effective cross-departmental collaboration. They provide insights into the critical factors for successful policy development.

Challenges in the area of policy development in Ireland

Despite current reform initiatives, strategies and examples of good practice, this assessment has revealed a number of areas of opportunity to further strengthen policy development practices and tools in Ireland. These include how current reform initiatives could be enhanced, leveraged and joined up to improve the overall policy development system. Although there are many good practices (or examples of “positive deviance”), these are not always widely known or shared, and not all are mainstreamed across departments. There are also a number of gaps and duplications that appear as a result of inconsistency in applying policy development practices and tools.

These challenges resonate with “areas for further improvement” identified by the CSMB (Government of Ireland, n.d.[10]):

ensuring a consistent and measured approach to develop and manage policy skills to meet the needs of the civil service

promoting greater innovation and openness to new ideas or alternative solutions that may involve a risk of failure but could lead to useful learning

providing opportunities for enhanced engagement with co-production partners in policy design, where such stakeholders are integral to implementation and delivery

developing a centralised approach to commissioning research and best practice mechanisms for engaging with research bodies and academics, helping to increase the quality of inputs and evidence during policy development

creating cross-government policy network supports, similar to other professional networking initiatives that are being advanced across government.

Overall, several themes – both good practices and areas of opportunity – emerged in the context of this research and are discussed further below in this report. They include:

further strengthening the evidence base for policy development, including balancing short-term demands for quick solutions to problems against working towards long-term policy priorities and the use of strategic foresight

continuing to bridge the policy and implementation divide

further improving the legitimacy of policy development both with respect to the political and technical interface and with respect to stakeholder engagement, including mechanisms for the co-creation and co-design of policies

articulating and developing the necessary skills for policy practitioners and collective capabilities across the system

ensuring that policy professionals have access to tools, methods and data for policy and effectively use them in their day-to-day work.

The subsequent chapters in this report will discuss these topics in more detail.

References

[4] Government of Ireland (2022), Cabinet Committees of the 32nd Government, https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation-information/48fd2-cabinet-committees-of-the-32nd-government/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[9] Government of Ireland (2022), Irish Government Economic and Evaluation Service - About Us, https://igees.gov.ie/about-us/# (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[5] Government of Ireland (2021), Social Policy and Public Service Reform Division, https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation-information/3d167e-social-policy-and-public-service-reform-division/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[3] Government of Ireland (2019), Our Public Service 2020 - Reform Plan, https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/cc5b1f-our-public-service-2020/.

[1] Government of Ireland (2014), Civil Service Renewal, https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/fd9c03-civil-service-renewal/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[6] Government of Ireland (1997), Reform Division, https://whodoeswhat.gov.ie/division/per/reform-division/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[8] Government of Ireland (1993), Statistics Act, https://www.cso.ie/en/aboutus/lgdp/legislation/statisticsact1993/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[7] Government of Ireland (n.d.), How is it governed?, https://www.ops.gov.ie/what-is-ops2020/how-is-it-governed/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[10] Government of Ireland (n.d.), “Strengthening Policy Making in the Civil Service”.

[2] Republic of Ireland (2014), The Civil Service Renewal Plan, https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/4392/121218123825-6313c8a415794e9da83c5d8709b5903e.pdf#page=null.