This chapter assesses the nexus between the civil service and the political space in relation to policy development and the processes and practices for stakeholder engagement, digitalisation and user-centric policy development. It concludes with areas of opportunity to clarify the role of the civil service in policy development and improve legitimacy in the policy development process.

Strengthening Policy Development in the Public Sector in Ireland

4. Strengthening the Legitimacy of Policy Development in Ireland

Abstract

The third pillar of the framework focuses on the legitimacy of policy development, which relates to the democratic basis of support throughout the policy development process. As highlighted by the 2021 OECD Trust Survey, the trust in government is closely linked with the legitimacy of public policies (OECD, 2022[1]). In recent years the legitimacy of policy choices has been under increased scrutiny across OECD countries and beyond partly in relation to the COVID-19 response (OECD, 2020[2]). Important questions emerge about how the public interest is integrated into the policy decisions, design and implementation. Or as the Civil Service Management Board (CSMB) has phrased it, reflecting on the context in Ireland: “In more recent years there has been a considerable challenge to the legitimacy of certain policy choices. This raises the question as to whether the debate on complex issues is sufficiently robust which raises the question as to whether public views, understanding and engagement are being sufficiently factored into the design and implementation processes (Government of Ireland, n.d.[3]).”

Although public policy development is essentially part of a broader democratic mandate, the legitimacy of public policy goes beyond the electoral cycle and the related political commitments; legitimacy is also grounded in the underlying support that a government or public body has for the policy or programme that it is proposing to deliver. This includes necessary engagement with the Oireachtas to build broad political support over the entire political cycle effective public communication, based on audience insights and social listening as well as consultation with and ownership from stakeholders and citizens, as end-users of public policy. Understanding the views and demands of the public is vital for ensuring policies are supported, complied with and ultimately considered legitimate. Mark Moore offers an analytical framework, the strategic triangle, as a guide to public sector leaders for optimal delivery of public value (Moore, 1995[4]). Legitimacy and support are a key element of this strategic triangle. Policy challenges that require action over medium to longer-term horizons and span election cycles will require the civil service to develop ongoing deep engagement with the community, sector groups and the wider public as well as with elected representatives. Ultimately, as also noted by the CSMB (Government of Ireland, n.d.[3]), “[t]he [other] essential component of legitimacy is public confidence; the trust displayed by the wider population in government to act in the general interest.”

Indeed, results from the 2021 OECD survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (OECD, 2022[1]) indicate that there is a need to better communicate the results of government action to citizens. In this context, the OECD trust survey finds that people in OECD countries see access to government information positively: almost two-thirds (65.1%) feel that information about administrative procedures is easily accessible. Governments should strengthen and consolidate information-sharing, making information and data publicly available and encouraging re-use and feedback. Yet people are far less satisfied with opportunities to engage in the policy-making process and with the government’s accountability to public feedback and demands. Around 40% of respondents believe they could voice their views about a local government’s decision concerning their community. And fewer than one-third (32.9%) of respondents believe that the government would adopt opinions expressed in a public consultation.

Yet, policy choices are often debated in public, which is a sign of a healthy democratic tradition, strengthening government accountability. Partly due to the social media culture, the public debate has accelerated in the last decade, with short life cycles of trending topics. Citizens expect instant information and answers, including from the government. This puts pressure on politicians to give an immediate response sometimes with little time for them (or their advisors) to reflect. Being responsive without simply being reactive is a constant challenge (OECD, 2018[5]). As the political dynamics are influenced by the headlines of the day (and aim to influence the debate at the same time), it can be challenging for the civil service to navigate and keep the set course.

The civil service is no longer a neutral actor or bystander in the public debate and can apply a number of approaches to contribute to the public debate in a constructive way. As demonstrated by the award-winning COVID-19 Lockdown Communications 2020 programme – jointly delivered by the Department of Health, the Government Public Information and Communications response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Department of the Taoiseach in collaboration with other government departments and agencies – transparency about decision making is critical, as is explaining why decisions were taken. Transparency includes recognising that evidence is incomplete and evolving and that mistakes are possible yet contribute to improving policies. The civil service may mitigate the risk of counterproductive public debates by helping shape the narrative, by defining what the key problem is (problem definition), by clarifying what the evidence says and does not say, and by using language that is clear, accessible and apolitical. Moreover, genuinely engaging stakeholders and citizens in the “problem-solving” process in an open way may further deepen the public discourse and pursue transparency and accountability. This would also contribute to building trust, as highlighted by the recent roundtable (Rafter et al., 2022[6]) in Ireland on assessing government communication.

A good example of legitimacy-building through broad dialogue is the Shared Island Unit, created in 2021 by the Department of the Taoiseach. It acts as a driver and co-ordinator of the whole-of-government initiative called Building Consensus on a Shared Island, which was defined as a strategic priority of the department over the period of 2021-23 (Government of Ireland, 2022[7]). The work of the Shared Island Unit involves supporting the delivery of commitments regarding this key priority across the government and fostering dialogue with other government departments, as well as civil society.

Furthermore, legitimacy is also derived from the ability of the government to transpose international commitments into domestic policy. The integration with the European Union (EU) in the context of legislative proposals and the development of Ireland’s policies is an ongoing challenge. EU timeframes and agendas do not always align with local timeframes and agendas. While Ireland can often rely on EU collective analysis, regulation and legislation, there are times when local issues demand more urgency, including the development of regulation and legislation which require significant resources.

This section will address the nexus between the civil service and the political space in relation to policy development and the processes and practices for stakeholder engagement.

Navigating the interface between the civil service and politics

Political-technical interface and the update of policy advice

The increased complexity of the policy development environment, given recent crises coupled with the 24-hour news cycle, has made it more challenging to co-ordinate across the government, bring in additional stakeholders and provide policy options to resolve multi-faceted problems. In Ireland, this also in turn, as was mentioned in a number of interviews, has led to challenges in the uptake of policy advice by politicians if they are expected to respond to immediate questions from the press. This may also crowd out the possibility of long-term issues being given the attention they need. The interviews at the political level highlighted the importance of focusing on a “band of outcomes” so that politicians can make informed choices in the public interest. This includes presenting data in a format that enables decision makers to take the appropriate decisions.

From the perspective of civil servants, interviews suggested there is pressure at times from ministers to fast-track policies without adequate analysis and advice which end up being hard to implement and/or have undesired side effects (see the section below on challenges of implementation). Other short-term demands as part of the democratic system, such as Freedom of Information requests, Parliamentary Questions and ministerial briefings, can also leave less time for focusing on longer-term strategic policy work. Interviewees also reported that in certain instances they had a concern that the advice provided was not accorded the weight it might have by ministers, i.e., rather than seen as an effort to sift, analyse and assess a range of evidence and advice from a variety of quarters, it was simply one other view alongside others within and outside the system proffering advice. Some officials felt they were not always able to influence priority setting, seen as a “very political process” as exemplified also by the responses of some at the political level.

“One of the things that drives so much behaviour within government departments is the freedom of information requests and the parliamentary questions – it is phenomenal the amount of work that that generates.”

“The political system wants stuff done immediately. So the demand, if you’re a senior civil servant, is that the system wants you to do stuff in relation to x or y or z and work on and develop proposals now. They don’t really want you disappearing off to do excellent work.”

Uptake of policy advice is also variable across ministries, and formats and timing for providing that advice vary – with the political level demanding advice and policy options that are politically realistic and reflecting the interest of citizens. Interviews at the political level showed very different approaches to the evidence used but also when and how it is gathered. Some preferred the use of more informal networks (business breakfasts), whereas others consulted under the auspices of more formal processes, networks/commissions or councils (including the National Economic and Social Council).

As in many countries, the context of a coalition government adds additional dynamics and layers of complexity, including in terms of following quality assurance processes on policies or procedures (time needed for review before placing an item on a cabinet meeting’s agenda, for example). It was also noted that at times trade-off decisions were made during the budgetary process which involve unrelated policy choices. In this context, it is helpful to strengthen practices that build ownership beyond the political cycle and beyond the traditional party lines, such as building alliances early on, to create broad buy-in and co-create with the political level. Policies such as First 5 and the National Cancer Strategy are a testimony that investing in a broad ownership base can yield comprehensive multi-year policies.

These issues at the political interface are not unique to Ireland. However, there are ways in which officials can manage the “authorising environment” to better navigate relationships with elected officials and politicians to have influence over policy agenda. Officials can support ministers in prioritising and using advice. As one interviewee noted, officials needed “to build up credibility with evidence-based policies and policy advice”. Officials can build trust by understanding the operating environment ministers work in (try to “walk in their shoes”), anticipating and being ready for future demand, and being proactive in their advice with a focus on opportunities for improvement, not just problems to be solved. Being able to have courageous conversations with ministers, including highlighting the longer-term impacts of policy that might eventuate outside the term of their government, also requires a certain type of skill from those working at the juncture between the civil service and the political system (political astuteness), as the political level demands advice and policy options that are politically realistic. Understanding the political achievability of policy options are policy skills that can be learned and developed and may be included in any future policy skills framework.

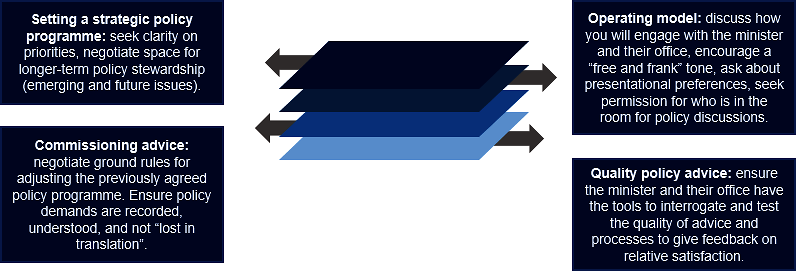

Examples from other OECD countries as well as good practices in Ireland could be included to guide civil servants in the future policy development platform. These examples could include quality assurance processes, having criteria related to ministerial satisfaction with advice from officials and processes for ensuring advice is presented in a way that resonates with and meets the diverse needs of decision makers (the customers of advice). It might also include guidance on how to establish trusted relationships and an agreed operating model with ministers, such as agreed ground rules on what policy work is undertaken and when, and some mechanisms for negotiating space in work programmes and budgets for longer-term policy stewardship.

In addition to the relationship between ministers and officials, the political-technical interface is also characterised by relationships between officials and political advisors, between advisors, including chiefs of staff, and between government ministers and senior officials on the one hand and members of parliament on the other, be it from coalition parties or from the opposition.

The role of political advisors in policy development is currently unclear, although the role of advisors is provided for under the Public Service Management Act (1997) (Government of Ireland, 1997[8]). The Act stipulates that special advisors shall assist the minister or minister of state by “providing advice” and “monitoring, facilitating and securing the achievement of Government objectives that relate to the Department”. Both the selection and performance of advisers continue to be regarded critically, as there is an expectation that this staffing complement should demonstrably bring added value, relevant expertise to the policy development process and an ability to learn “how government works” in a short period of time (Connaughton, 2017[9]).

The OECD’s interviews showed that the skills of political advisors are increasingly focused on political communication and achievability rather than policy. As in other OECD countries, the key could be to develop a collaborative relationship between the civil service and political staff, characterised by a responsive and proactive civil service that engages in regular, informed discussions and interactions with the minister and the minister’s office. Guidance for political staff may support this partnership approach. For example, Australia has issued guidance on the roles and responsibilities of political staff vis-à-vis civil servants (Government of Australia, 2021[10]). New Zealand has developed a code of conduct for political advisors and political office staff (Government, 2022[11]). The responses to the survey highlighted some areas of opportunity in this regard. The Senior Official’s Group (SOG) meeting was referenced as a safe space where senior officials take on board the views of political advisors on the achievability and saleability of proposals. Equally, the SOG meetings provide an opportunity for the administrative system to relay to the political side what is feasible and what is not.

In this context, the Australia and New Zealand School of Government has recently laid out measures that can support ministers to prioritise and use policy advice and ways that departments can support them, focusing on some key components of the relationship between ministers and their departments (Figure 4.1). This could provide a framework for discussing relationships between departments and between ministers and their offices and how those relationships can be improved.

Figure 4.1. Minister-department relationships: Key components to negotiate

Research also showed that the uptake of policy advice can be variable across departments in Ireland and that the formats and timings for providing that advice also vary. The use of evidence/data in influencing the political discourse also depends on the ability to centre it within a broader narrative used by politicians and the general public. There are nonetheless good practices and examples in this area from within Ireland and in other OECD countries that could populate the future policy development platform.

Stakeholder engagement, digitalisation and user-centric policy development

New forms of citizen engagement, representation and public participation are emerging in all OECD countries. In this context, digitalisation has provided a new medium for engagement with citizens on various sides of the policy debate. Ireland ranks 5th of the 27 EU Member States in the 2022 edition of the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI 2022 Ireland Country report). Ireland’s average yearly relative growth of its DESI score between 2017 and 2022 is approximately 8.5%, one of the highest in the EU. Ireland performs well regarding the human capital dimension, as the share of people with basic digital skills and digital content creation skills, as well as the share of ICT specialists, including female ICT specialists, is above the EU average. Ireland is a top performer for mobile broadband take-up.

The commitment of Ireland to drive the digital agenda is also demonstrated in the “Connecting Government 2030: A Digital and ICT Strategy for Ireland’s Public Service”, which sets out an approach to deliver digital government for all, benefitting both society and the broader economy. The Public Service in Ireland aims at harnessing digitalisation to drive a step-change in how people, businesses, and policymakers interact, ensuring interoperability across all levels of government and across public services. A key objective is to ensure that in digitalising public services a “user first” and “business first” approach is taken. As a key reform initiative of the Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform, delivering on Connecting Government 2030 will help achieve these ambitions. It will also drive the wider GovTech priorities as well as bring significant public value benefits.

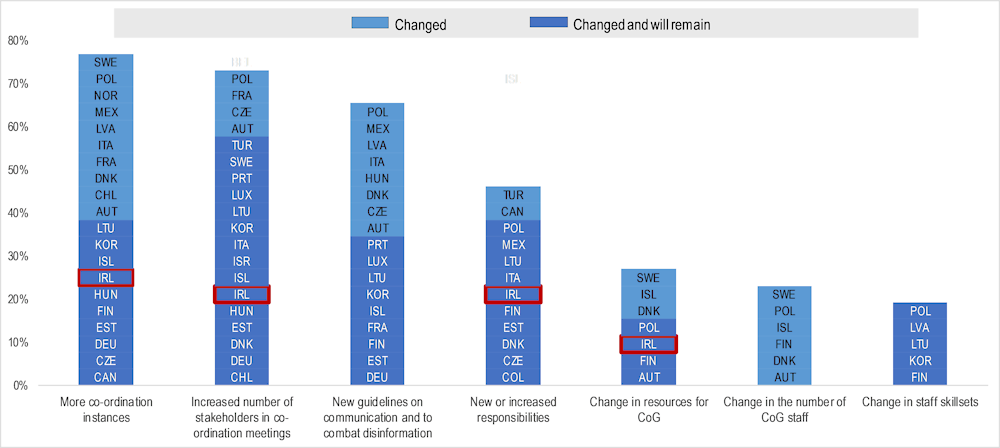

The COVID-19 crisis has only served to increase expectations from citizens about bringing them to the decision making table as evidenced by the OECD Centre of Government Recovery Survey in 2021 (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Changes experienced by centres of government since the COVID-19 outbreak that will remain when planning the recovery from the crisis, 2021

Note: Based on OECD (2021), “Survey on Building a Resilient Response: The Role of Centres of Government in the Management of the COVID-19 Crisis and Future Recovery”; Data for Australia, Greece, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States are not available.

Source: (OECD, 2021[13])

At the same time, these developments have expanded the expectations that citizens participate more fully in policy development within the overall framework of representative democracy. Citizens are increasingly demanding greater transparency and accountability from their governments and want greater participation in shaping policies that affect their lives (OECD, 2016[14]). Citizens expect governments to take their views and knowledge into account when making decisions on their behalf. As highlighted by the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, engaging citizens in policy development allows governments to respond to these expectations and, at the same time, design better policies and improve their implementation (OECD, 2017[15]) (OECD, 2022[16]). While the information and consultation of stakeholders and citizens are initial levels of participation, governments should also promote innovative ways to effectively engage with stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions during all phases of the policy-cycle and in the service design and delivery (OECD, 2017[15]).

This perspective is recognised by the civil service in Ireland and articulated as part of the legitimacy pillar in the document “Strengthening Policy making in the Civil Service” by the Civil Service Management Board (p.12): “Two [other] features, which have been highlighted both within the Irish context and internationally as an element of policy making that needs to be strengthened, are necessary. The first is stakeholder engagement whereby policymakers understand the role and perceptions of interested parties and how they might assist in ensuring that policy objectives are translated into concrete action. The [other] essential component of legitimacy is public confidence; the trust displayed by the wider population in government to act in the general interest.” Past policy “failures” have frequently not engaged and obtained buy-in from stakeholders and customers or have missed to develop a more sophisticated debate to avoid widespread public opposition.

Interviewees pointed out that public consultation processes to capture views of citizens have been strengthened significantly in recent years.

“I think there is better engagement with citizens. The strength of the citizen’s assembly and the strength of consultation have substantially increased in my understanding over the last number of years, so there’s a better recognition across various different organizations that there is a need to consult not just for the sake of it but to listen and to take all of that on board and into account when developing the policy.”

However, despite recognition that consultation practices have increased and matured, the OECD’s project survey highlighted mixed views on stakeholder engagement. Some respondents stated that this capacity is not developed within their department, while others stated that stakeholders are indeed largely involved in policy development. Others referred to the consultation process as an exercise often biased towards well-established/organised stakeholders and engagement happening mostly in urban and less in rural areas. And still others viewed stakeholders as mostly “being involved only after decisions are taken” and found co-creation limited. While these represent a snapshot of diverse views, they also highlight areas where there are expectations for improvement and where the sharing of good practices across the government (see below) could be beneficial. Stakeholder engagement should not be considered a checkbox exercise but be purposefully designed and conducted with adequate time and at minimal cost for the participating stakeholders, while avoiding duplication to minimise consultation fatigue. It is also important that participation opportunities are adequately communicated, and that communication is inclusive, accessible and compelling, while also ensuring adequate communication around the results of these engagements. Moreover, the sharing of good practices may enhance the number of instances where stakeholders are given the opportunity and the necessary resources (e.g. information, data and digital tools) to collaborate during all phases of policy development and not only after decisions are taken. Further, specific efforts should be dedicated to reaching out to the most relevant, vulnerable, underrepresented, or marginalised groups in society, while avoiding undue influence and policy capture.

Interviewees also raised the issue of whether expectations are created that may not be met given political realities or practical implementation challenges. Listening to the views of citizens does not mean automatically that these views will be taken forward in the process. Moreover, policymakers are confronted with the challenge that suggestions from citizens may be contradictory (by different interest groups of individuals, raising the question of which suggestion has more legitimacy than others), in conflict with the available evidence, or unrealistic, as they may not take into account other perspectives nor the legislative processes that can implement these policy expectations. Therefore, when not carefully curated, citizen consultations may paradoxically further erode trust in government instead of restoring it. Therefore, the civil service needs clarity about when and how to involve the public and about how much input/influence they are going to have.

In Ireland, guidance on public consultation was previously developed by the Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform (DPENDR) (Government of Ireland, 2016[17]) as part of the objectives of the first Civil Service Renewal Plan 2014, which aims to “promote a culture of innovation and openness by involving greater external participation and consultation in policy development”. This “Consultation Principles & Guidance” document dates from 2016, and since then new initiatives have been taken (such as The Citizens’ Assembly). In line with a commitment under the Open Government Partnership National Action Plan, the public consultation guidelines are currently being updated by DPENDR with the support of IPA, who are undertaking public consultations in this regard. Various departments have also developed guidelines and tools for staff on citizen engagement.

In terms of a more developed and systemic approach to government communication and citizen engagement, the Government Information Service (GIS) – which is based in the Department of the Taoiseach – works to foster strong collaboration and co-ordination among press and communication officials in other government departments and agencies. It co-ordinates, supports and amplifies communications around key government priorities such as Housing for All, Brexit, Shared Island, Climate Action, COVID-19 and Ukraine. It also supports and encourages capacity-building in the area of communication and engagement across the civil and public service (including through the Government Communications Network) and manages the “Government of Ireland” identity and unified web presence of gov.ie. Gov.ie went from strength to strength during the COVID-19 pandemic and came to be regarded as a trusted source of authoritative public information on COVID-19. For example, in 2019, gov.ie had just over 6 million page views whereas this figure grew to just over 117 million in 2020. More recently, GIS has been able to use the gov.ie platform to provide coherent information to the public on Ireland’s response to the war in Ukraine, and there will be other opportunities in the future to do likewise.

Communicating relevant, timely and accessible information to citizens is a pre-requisite for stakeholder engagement. Today, digital technologies have made communicating easier than it has ever been, but many governments are often missing the opportunity to effectively engage with their citizens and face multi-faceted challenges as they attempt to do so (OECD, 2021[18]). In particular, radical transformations to the information ecosystem have upended traditional communication methods and enabled the spread of mis-and disinformation at an unthinkable scale. The dominance of online channels, where every individual can be both a producer and consumer of content, means that governments face greater competition for the finite attention of citizens. At the same time, constructive public debates and well-informed engagement from stakeholders are needed in order to address the climate emergency and other pressing reform agendas.

Public communication plays an important role in this regard. It can increase the reach and visibility of engagement opportunities, such as consultations or deliberative processes on specific policies. It can also multiply the occasions and avenues that citizens have to provide feedback and participate in shaping policies and services through online and offline channels. Developing better capacities to turn such feedback into insights for policy-makers, and responding to it, is essential in achieving stronger engagement and a greater dialogue between governments and citizens. The latter also requires communications that is more targeted and compelling, based on audience insights that provide communicators with a real-time understanding of public concerns and sentiment. Beyond simple demographic traits, understanding the habits, attitudes and information consumption patterns from different segments of society is key to designing communications that are more effective, especially for vulnerable or hard-to-reach groups.

In Ireland, individual departments have some well-developed engagement and communication approaches at a sectoral level, e.g., the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications, for instance, has a well-developed system of citizen and stakeholder engagement, which are also a central part of the Civil Service Renewal Plan and the Open Government Partnership National Action Plan. The department has created a guidance document for staff on stakeholder engagement, which outlines how to create a five-step stakeholder engagement plan by defining the purpose of the engagement, identifying the stakeholders, carrying out the analysis, communicating well and doing a risk assessment as well as a contingency plan. The document also offers case studies and a detailed guide on the implementation process.

The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage has also conducted an extensive public consultation on the National Marine Spatial Planning Framework, an exercise that has been praised by the European Commission (Box 4.1). To support government departments, public bodies and local authorities to effectively engage with disabled people in decision making processes, the National Disability Authority published updated participation guidelines in 2022 (National Disability Authority, 2022[19]).

DPENDR and the National Adult Literacy Agency also developed a communication toolkit “Customer Communications Toolkit for the Public Service - A Universal Design Approach” to inform the design and procurement of customer communication in the Public Service, and as a support to those working in contact with the public (Government of Ireland, 2019[20]). This toolkit complements the Plain English Style Guide for the Public Service.

Box 4.1. Local public consultation on Marine Spatial Planning in Ireland

Ireland held a three-month public consultation on its Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) baseline report. This was part of the broader consultation process that resulted in Ireland’s first MSP. The MSP team hosted public engagement events in almost all coastal counties across Ireland.

These events were aimed at raising awareness of:

the concept of MSP

the Irish government’s plans to develop a marine plan for the country

how people could engage with the plan-making process

the timeframe for the various phases of this process.

During the consultation period, five regional public engagement events were held across coastal communities. In total, over 170 responses on the baseline report were received, and these had a significant impact on the content of the draft MSP. This consultation process was also expanded and repeated for Ireland’s draft plan. This practice focuses on a participatory and transparent process, enabling the public to engage in the MSP process and to provide their views on the report and the MSP draft.

Source: (European Commission, 2022[21])

Civil society organisations (CSOs) can be characterised as diverse and proactive actors engaged with the public policy development process in Ireland. The ability of Irish CSOs to mobilise public opinion and influence policy development on a wide array of issues depends to a large degree on their analytical capacities and resources. Irish CSOs’ success in inducing societal change derives in part from their resilience and agility, which enables them to adapt to evolutions within the Irish public policy process (Hogan and Murphy, 2021[22]).

Changes in the Irish political environment, or “political opportunity structures”, have inevitably influenced CSOs’ engagement practices, leading to new challenges and opportunities. While the 2008 global financial crisis inherently shrunk the overall space and legitimacy of some public policy actors, including CSOs, this post-crisis era can also be characterised by a new political environment where inclusive and consultative processes are increasingly integrated into policy formulation and analysis. This shift in political culture required transformative changes in CSOs’ models of action and policy-analytical capacities – resulting in increased levels of formalisation and professionalisation, as well as new avenues of engagement for CSOs to shape policy development processes in Ireland.

Recent evidence demonstrates the growing influence of CSOs on Irish public policy processes, such as the successful 2018 referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1983. Besides investing significant time and resources in policy influencing, CSOs are often acclaimed for their capacity to translate lived experience into policy analysis. This success of CSOs’ engagement and policy contribution, however, lies in their capacity to set agendas, frame narratives, collaborate with other CSOs and raise the public interest to build rational argumentation and persuasive capacity. For this purpose, CSOs increasingly examine innovative avenues for public participation such as electronic survey instruments as a way to gather relevant cross-cutting data, provide critical analysis and hence gain tactical political traction. Among others, the successful 2018 referendum highlighted the instrumental role of CSOs – and their capacity to collaborate with each other – in the provision of facts and comprehensive evidence, personal testimony and international perspectives.

However, several challenges remain for their involvement in the policy development process, including funding, capacity, skills and staffing, regulation and compliance, public perception, and innovation. Despite funding pressures and regulatory constraints, CSOs remain committed to advocacy and influencing public policy, although they do not always feel heard despite the consultation process – in particular in some cases for social partners’ not seeing their comments reflected or responded to formally. Their influence on public policy formulation in Ireland will notably depend on their ability to develop advanced policy capacity and to demonstrate best-practice innovation, responsiveness and effectiveness to public authorities and civil society actors, in line with political opportunity structures that may emerge in the future.

Another participatory methodology to further engage CSOs in policy development is co-creation. A common example of this kind of methodology is the Open Government Partnership (OGP) Action Plans, which are the result of a co-creation process in which government institutions and civil society work together to design commitments that aim to foster participation, transparency, integrity and accountability (Open Government Partnership, n.d.[23]). Launched in 2011, the OGP has 77 member countries and 106 local governments, including Ireland which joined in 2013 and is currently implementing its co-created 3rd OGP Action Plan (2021-23) (Open Government Partnership, n.d.[24]). While good examples of this new form of collaboration between government and stakeholders from across society in the co-design and co-creation of policies exist, the concept has also been misunderstood in some cases, where groups may see it as determining policy rather than seeking to influence it, alongside evidence and other considerations that government may have to consider such as resourcing, prioritisation and unintended consequences. And while deepened co-operation is redefining roles and the relationship between government and stakeholders, co-creation does not replace applying formal rules and principles of representative democracy (OECD, 2016[14]). It thus does not take away the responsibility and the authority/agency of government to decide on difficult policy choices, to assess all of the evidence and wider implications, and ultimately to decide on both the direction and pace of policy implementation. Proper rules of application and a shared consistent approach to how this type of collaboration with society can work and where its use is appropriate and necessary for sound policy are thus needed.

Increasingly, public authorities are reinforcing democracy by making use of deliberative processes in a structural way, beyond one-off initiatives that are often dependent on political will. Structural changes to make representative public deliberation an integral part of countries’ democratic architecture is a way to effectively promote true transformation, as institutionalisation anchors follow-up and response mechanisms in regulations. Creating regular opportunities for more people to have the privilege to serve as members in citizens’ assemblies not only improves policies and services, but it also scales the positive impact that participation has on people’s perception of themselves and others, strengthening societal trust and cohesion (see Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy

The OECD has developed a guide for public officials and policymakers outlining eight models for institutionalising representative public deliberation to improve collective decision making and strengthen democracy. The guide provides examples of how to create structures that allow representative public deliberation to become an integral part of the way certain types of public decisions are taken.

Eight models to consider for implementation:

1. combining a permanent citizens’ assembly with one-off citizens’ panels

2. connecting representative public deliberation to parliamentary committees

3. combining deliberative and direct democracy

4. establishing standing citizens’ advisory panels

5. sequencing representative deliberative processes throughout the policy cycle

6. giving people the right to demand a representative deliberative process

7. requiring representative public deliberation before certain types of public decisions

8. embedding representative deliberative processes in local strategic planning.

While each of these models has its strengths and weaknesses to be considered, they can yield important benefits, such as allowing public decision makers to take more complex and difficult decisions better, enhancing public trust, increasing public ownership and support, and strengthening society’s democratic fitness.

Source: (OECD, 2021[25])

A notable Irish example of capturing views of citizens is the Citizens’ Assemblies (Citizens’ Assembly, n.d.[26]), a deliberative democracy model reporting to parliament. Citizens’ Assemblies bring longer-term issues into the present, with deliberations on issues such as biodiversity loss and gender equality, constitutional issues such as the length of parliamentary terms, and areas such as ageing populations and climate change (see Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Consultation with citizens: “The Citizens’ Assembly of Ireland”

The Citizens’ Assembly is a body formed by common citizens to deliberate on important issues. It was established in 2016 as a successor to the Constitutional Convention, which was originally conceived to discuss amendments to the Irish Constitution. The Assembly is a form of participatory and deliberative democracy that directly engages citizens who are called to vote on a specific topic. The Assembly’s primary objective is to gather a representative and random group of citizens to discuss important policy and legal issues and then make recommendations reporting to the Oireachtas. It is composed of 99 citizens and a chairperson.

The Assembly gathered 12 times between 2016 and 2018 to discuss 5 main issues. The first was the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution, as set out in the Resolution of the Houses of the Oireachtas approving the very establishment of the Assembly. After the first Assembly about the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution, 4 other issues were considered between 2017 and 2018. These included sessions on how to best respond to challenges and opportunities of an ageing population, fixed-term parliaments, the structure and modalities of referenda, and climate change.

How these processes translate into cross-government policy goals and shape the priorities of civil service policy efforts is less evident. Responses in interviews with civil servants suggested these were only truly useful when dealing with very circumscribed yes/no issues rather than complex policy problems. Using them to drive policy in such areas would create expectations that would be hard to meet.

The results from the survey also suggest that, although there are good examples of co-creation, tools to support these practices are not always well known across the government. Innovative tools such as behavioural insights are not widely used, and if they are, the results and impact of their use are not widely shared across departments. And yet, there is a demand for these lessons learned, as some respondents to the survey placed the focus on the need to strengthen “meaningful cross-departmental collaboration with customer-centric service design at its core. Impact on end users must be the focus of policy-making decisions”.

Various countries have processes in place to ensure that feedback from stakeholders has been enacted and followed up on, closing the feed-back loop through effective communication (see Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. Systematic follow-up on stakeholder consultations in selected OECD countries

Colombia

The Colombian Environment Ministry publishes responses to stakeholders’ comments online. If a comment is rejected, the website provides an explanation as to the decision. If a comment is accepted, it explains how the comment is taken into account in the regulatory proposal.

Iceland

Icelandic policymakers publish consultation conclusions on the government’s consultation portal. A report highlights the main points raised by stakeholders as well as their suggestions for improvement and areas of concern.

Slovak Republic

After a comment on a draft regulation open for public consultation in the Slovak Republic reaches 500 reactions from other stakeholders, the regulator is required to react to the comment and, furthermore is required to talk to these stakeholders. In addition, policymakers indicate for every comment whether it is major or minor and whether it has been accepted, rejected or partly accepted with the corresponding reasoning for the decision.

Source: (OECD, 2018[28])

Areas of opportunity to improve legitimacy in the policy development process

This chapter articulated the changing role of the civil service in driving the public policy debate and in steering the policy dialogue in the technical-political interface in a context that is often shaped by the 24-hour news cycle and, as in other OECD countries, a focus on the short term in response to political calendars rather than on sustainability and longer-term challenges. It also identified various innovations and excellent case examples of structural collaboration with citizens and other stakeholders, underscoring the relevance of co-creation practices and tools such as behavioural insights, which may contribute to a more grounded legitimacy of public policies. This chapter also highlighted the pivotal role of the Government Information Service in public communication around key government priorities, as well as the added value of regulatory oversight for the legitimacy of proposals requiring legislative expression.

Despite a number of good practices that were shared, including the building of broad alliances to support the development of policies (such as First 5), consultations and interviews with public officials pointed to several areas that can benefit from further improvement:

A clearer articulation of the specific policy advice role of the civil service.

While there are tools and processes in place to support a clear technical-political interface, a number of these could be updated or reviewed, including the Cabinet Handbook and the DPENDR “Consultation Principles & Guidance” (currently being updated).

A partnership approach with political advisors, formalising rules of engagement and strengthening skills to understand the political achievability of policy options, may render the civil service more effective in navigating the complexity of policies in the current environment.

Additional training and support could be given to the civil service in public engagement and communication by articulating a clear narrative and defining the key problem, by clarifying what the evidence says and does not say, and by using language that is clear, accessible and apolitical.

Improving the ways in which stakeholders are consulted and what they should be consulted for, alongside better use of co-creation practices and tools such as behavioural insights, may also contribute to a more grounded legitimacy of public policies.

References

[26] Citizens’ Assembly (n.d.), Citizens’ Assembly - An Tionól Saoránach, https://citizensassembly.ie/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[9] Connaughton, B. (2017), “Political-administrative relations: The role of political advisers”, Administration, Vol. 65/2, pp. 165-182, https://doi.org/10.1515/admin-2017-0020.

[21] European Commission (2022), Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council outlining the progress made in implementing Directive 2014/89/EU establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0185&qid=1652648587198.

[10] Government of Australia (2021), State of the Service Report 2020-21 - Strengthening partnerships, Australian Public Service Commission, https://www.apsc.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/workforce-information/research-analysis-and-publications/state-service/state-service-report-2020-21/chapter-2-harnessing-momentum-change/strengthening-partnerships.

[27] Government of Ireland (2022), Citizen information, https://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[7] Government of Ireland (2022), Shared Island Initiative Report - Action on a Shared Future, Department of the Taoiseach, https://www.gov.ie/en/campaigns/c3417-shared-island/.

[20] Government of Ireland (2019), Customer Communications Toolkit for the Public Service (Plain English Guide), Department of Public Expenditure, NDP Delivery and Reform, https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/1f22bc-customer-communications-toolkit-for-the-public-service/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[17] Government of Ireland (2016), Consultation Principles & Guidance, Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, https://assets.gov.ie/5579/140119163201-9e43dea3f4b14d56a705960cb9354c8b.pdf.

[8] Government of Ireland (1997), “Public Service Management Act”, https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1997/act/27/enacted/en/index.html.

[3] Government of Ireland (n.d.), “Strengthening Policy Making in the Civil Service”.

[11] Government, I. (2022), Special advisers, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/our-work/topics/ministers/special-advisers (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[22] Hogan, J. and M. Murphy (eds.) (2021), Policy Analysis in Ireland, Policy Press, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1hhj11n.

[4] Moore, M. (1995), Creating Public Value - Strategic Management in Government, Harvard University Press.

[19] National Disability Authority (2022), Participation Matters - Guidelines on implementing the obligation to meaningfully engage with disabled people in public decision making, https://nda.ie/uploads/publications/NDA-Participation-Matters_Web-PDF_092022.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[1] OECD (2022), Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy: Main Findings from the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions, Building Trust in Public Institutions, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b407f99c-en.

[16] OECD (2022), Open Government Review of Brazil: Towards an Integrated Open Government Agenda, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3f9009d4-en.

[25] OECD (2021), Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy, OECD, https://doi.org/10.1787/4fcf1da5-en.

[13] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[18] OECD (2021), OECD Report on Public Communication: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/22f8031c-en.

[2] OECD (2020), “Building resilience to the Covid-19 pandemic: the role of centres of government”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/building-resilience-to-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-role-of-centres-of-government-883d2961/.

[5] OECD (2018), Centre Stage 2 - The organisation and functions of the centre of government in OECD countries, OECD, https://www.oecd.org/gov/report-centre-stage-2.pdf.

[28] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[15] OECD (2017), “Recommendation of the Council on Open Government”, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0438.

[14] OECD (2016), Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268104-en.

[23] Open Government Partnership (n.d.), Action Plan Cycle, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/process/action-plan-cycle/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[24] Open Government Partnership (n.d.), Open Government Partnership - Ireland, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/members/ireland/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

[6] Rafter, K. et al. (2022), “Assessing government communication – A roundtable”, Administration, Vol. 70/3, pp. 159-178, https://doi.org/10.2478/admin-2022-0024.

[12] Washington, S. (2021), “Fixing the ’demand side’ - helping ministers perform”, The Mandarin, https://www.themandarin.com.au/168304-fixing-the-demand-side-helping-ministers-perform/.