This chapter discusses the specific enabling conditions for green investment in SADC, including key elements of the broader framework for environmental protection, and targeted financial, technical and information support to attract and facilitate green FDI.

Sustainable Investment Policy Perspectives in the Southern African Development Community

5. Promoting investment for green growth

Abstract

Investment for green growth is central to the SADC Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan 2020‑30 and needs to be scaled-up significantly to advance sustainable development in Southern Africa, and achieve national economic, social and environmental policy goals. Green growth means fostering growth and development while preserving natural assets and ensuring that they continue to provide the resources and environmental services on which our well-being relies. Beyond mainstreaming green growth considerations into investments in general, so as to minimise their environmental footprint, this requires investments in new technologies, services and infrastructure that make more sustainable claims on natural resources (green investments). Under certain circumstances, foreign direct investment (FDI) can contribute the needed financial and technological resources to deliver green growth. But foreign investors can also deteriorate environmental outcomes and hamper sustainable development. This chapter discusses the specific enabling conditions for green investment in SADC and targeted policies designed to attract and facilitate green FDI.

Green growth and climate change in Southern Africa

The Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) path to green growth faces both challenges and opportunities. Challenges include a heavy dependence on natural resources and unsustainable use of these resulting in degradation of land and water, a major investment gap for basic infrastructure and increasing vulnerability to climate change and extreme weather. Addressing these challenges also presents an opportunity for SADC to promote green investment. The imperative to urgently scale up access to electricity and promote energy security, the region’s high renewable energy potential and the need to improve the efficiency of how natural resources are used illustrate the potential for green investment in Southern Africa. A measured and inclusive approach, based on a sound policy framework that promotes investment in green sectors and facilitates the greening of investment overall, can help address challenges and promote sustainable development in SADC.

Natural resources are critical for continued development in Southern Africa

Southern African countries are at different stages of development, but almost all their economies, have grown by over 50%, and six have more than doubled since 2000 (Table 5.1). SADC countries have relied heavily on natural resources to support economic development in past decades, and primary sectors continue to contribute substantially, despite the rising importance of industry and services across the region. In 2020, rents from natural resource amounted to over 10% of GDP in Angola, DRC, Mozambique and Zambia, while agriculture, forestry and fishing made up over 20% of GDP in Comoros, Tanzania, Mozambique, Madagascar, Malawi and DRC (World Bank, 2023[1]). Due to illegal logging and export of timber, in some SADC countries the impact of forestry and fishing on the economy is likely to be underestimated in national statistics (Browne, Kelly and Pilgrim, 2022[2]).

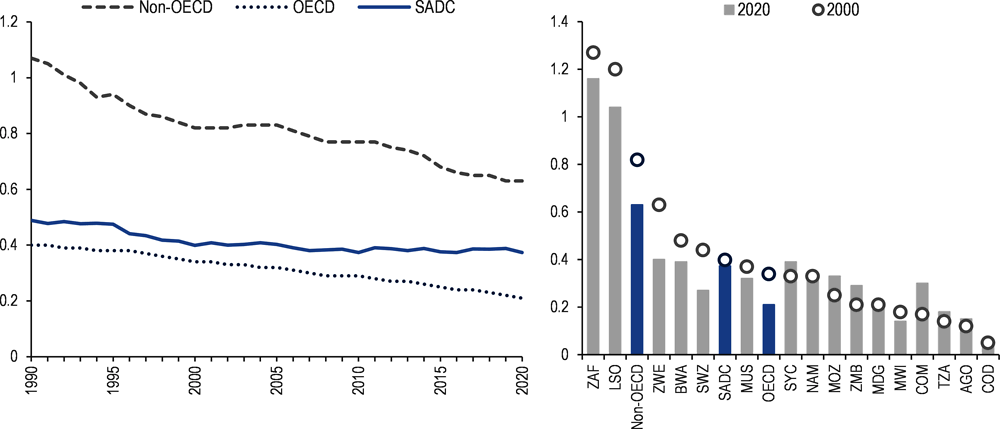

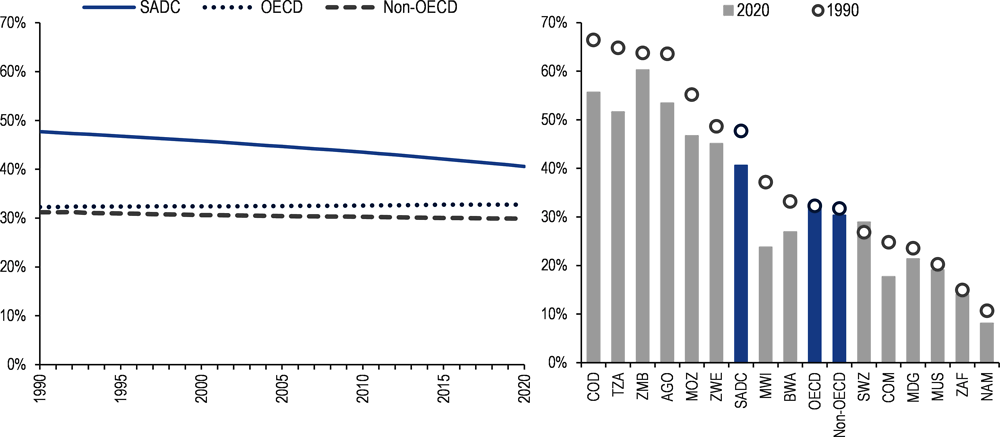

Heavy reliance on natural resources for development, coupled with unstainable use of these resources, means that the environment costs of growth have been high. Since 1990, Southern Africa has experienced the highest rate of deforestation in Africa, contributing 31% to Africa’s deforested area. Forest cover in the region has shrunk by 15% over the last 30 years, compared to a 4% decrease in non-OECD countries and a 2% increase in forest cover in the OECD (Figure 5.1). The largest decrease in forest cover is observed in Malawi (‑36%), Comoros (‑29%), and Tanzania (‑20%), while forest cover has increased slightly in Eswatini (8%). In Madagascar, more than 80% of the original forest cover has been lost, with primary forests covering only 12% of the country at present (SBDC, 2014[3]). Deforestation has also been a major driver of carbon emissions in the region. Southern Africa still generates only 1% of global carbon emissions, and a quarter of Africa’s emissions, yet emissions per unit of GDP are declining at a slower rate than other non-OECD economies, and have risen in six SADC countries (Figure 5.2).

Table 5.1. Selected economic and environmental indicators

|

MS |

GDP growth over 2000‑20 (%) |

Agriculture, forestry & fishing (% of GDP) |

Natural resource rents (% of GDP) |

Poverty rate (% of population) |

2022 EPI Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AGO |

164% |

9.1 |

25.5 |

32.3 |

151 |

|

BWA |

94% |

2.2 |

0.7 |

19.3 |

35 |

|

COD |

191% |

20.9 |

14.9 |

63.9 |

85 |

|

COM |

73% |

35.8 |

1.5 |

42.4 |

119 |

|

LSO |

53% |

4.8 |

5.1 |

49.7 |

141 |

|

MDG |

66% |

24.7 |

5.3 |

70.7 |

167 |

|

MOZ |

252% |

26.2 |

11.7 |

46.1 |

144 |

|

MUS |

83% |

3.1 |

0.0 |

10.3 |

77 |

|

MWI |

136% |

22.7 |

4.0 |

50.7 |

97 |

|

NAM |

89% |

9.2 |

2.0 |

17.4 |

44 |

|

SWZ |

88% |

8.1 |

3.9 |

58.9 |

75 |

|

SYC |

82% |

2.1 |

0.2 |

25.3 |

32 |

|

TZA |

247% |

26.7 |

3.9 |

26.4 |

134 |

|

ZAF |

59% |

2.5 |

3.9 |

55.5 |

116 |

|

ZMB |

204% |

3.0 |

11.8 |

54.4 |

69 |

|

ZWE |

4% |

8.8 |

6.8 |

38.3 |

106 |

Figure 5.1. Forest cover as a share of land area in SADC, 1990‑2020

Source: FAOStat, Agri‑environmental indicators – Land use, http://www.fao.org/faostat/, accessed 6.02.23.

Figure 5.2. Carbon emissions in Southern Africa, 1990‑2020

Urbanisation has exacerbated land degradation and biodiversity loss and brought additional environmental challenges. According to the 2022 Environmental Performance Index that covers 180 countries worldwide, most SADC countries rank poorly in terms of progress toward improving environmental health, protecting ecosystems, and mitigating climate change, with eight countries ranking among the lowest 50 scores. Greater vehicle ownership, burning of agricultural and other waste and construction activities have increased air pollution in urban areas, and mining activities accompanied by the discharge of untreated wastewater and solid waste into water bodies is impacting water quality in rivers and lakes. According to some estimates, an estimated 50% of South Africa’s wetlands have been destroyed and 82% of its main river ecosystems are threatened.

Southern Africa’s land, forests, rivers and coasts support employment and livelihoods for most of the region’s people and are especially critical for continued progress on reducing poverty. Over a third of the population lives in extreme poverty in ten countries in the region (UNDP-OPHI, 2022[4]). The number of people living in poverty is particularly high in remote rural areas where peoples’ livelihoods rely on small-scale agriculture, fisheries and forest resources. Escalating deforestation, soil degradation, biodiversity loss and over-exploitation of wild-life, fisheries and rangelands undermine the development prospects for present and future generations in many SADC countries.

Southern Africa remains highly vulnerable to climate change

The developmental challenges facing SADC countries, exacerbated by poor economic and political governance, make the region highly susceptible to the effects of climate change. The 16 SADC states have recorded 37% of all weather-related disasters in Africa in the past four decades. These affected 228 million people, left 2.7 million homeless and inflicted damage in excess of US$ 26 billion (ISS, 2021[7]; CRED, 2023[8]). Climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of extreme hazards such as floods, droughts, storms and wildfires, damaging infrastructure, destroying agricultural crops, disrupting livelihoods and causing loss of lives. Many communities in the region have little ability to adapt, and their dependency on natural resources and exposure to repeated and extreme hazards render them extremely vulnerable.

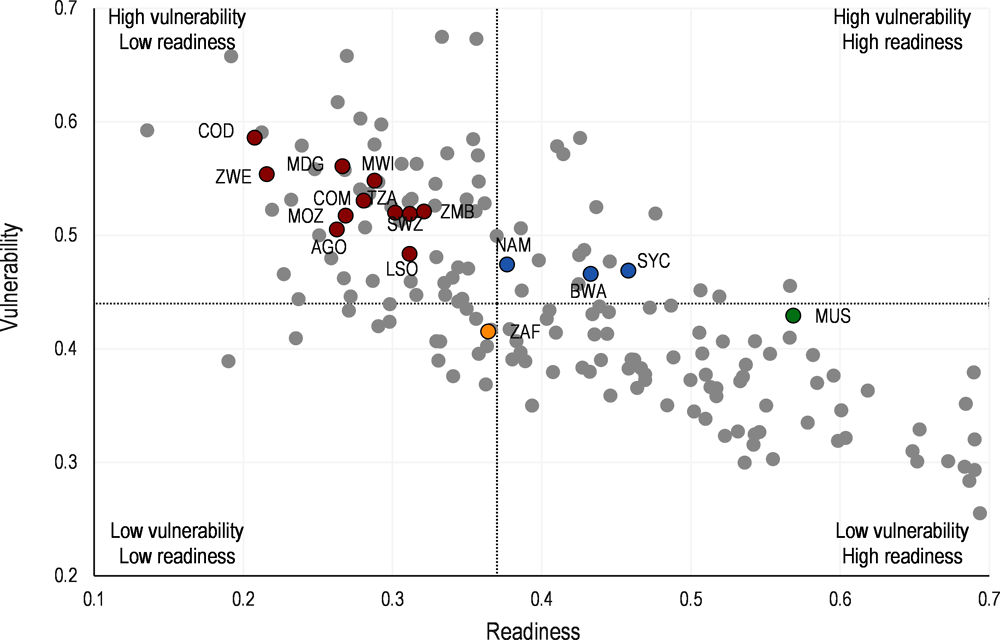

The Notre Dame‑Global Adaptation Index (ND-GAIN) measures the predisposition of countries to be negatively impacted by climate‑related hazards across life‑supporting sectors, like water, food, health, and infrastructure (i.e. vulnerability), against their economic, social and governance ability to make effective use of investments for adaptation actions thanks to a safe and efficient business environment (i.e. readiness). The index suggests that the majority of SADC countries exhibit high levels of vulnerability combined with low levels of readiness, with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zimbabwe and Madagascar among the least resilient (Figure 5.3). Seychelles, Namibia and Botswana are somewhat more resilient with high levels of vulnerability paired with high readiness, while South Africa is relatively less vulnerable but also less ready. With moderate levels of vulnerability and significantly higher levels of readiness, Mauritius is the only SADC country considered to be resilient to the effects of climate change.

Figure 5.3. Resilience to climate change in SADC

FDI can improve access to clean and affordable energy in the region

The SADC region faces a huge power deficit due to lack of investment in the power sector. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has sent food, energy and other commodity prices soaring, increasing the strains on SADC economies already hard hit by the COVID‑19 pandemic. The overlapping crises are affecting many parts of SADC’s energy systems, including reversing positive trends in improving access to modern energy, with 4% more people living without electricity in 2021 than in 2019. Over 80% of the electricity is generated from coal, and the energy sector is responsible for 65% of CO2 emissions in the region (IEA, 2022[10]). A disruption to power supplies is a major threat to sustainable development in the region.

Accelerating investment in clean energy is critical to urgently scale up access to electricity, and at the same time mitigate climate change. Private investment, and in particular FDI, can play a key role in advancing the energy transition and supporting rural electrification. Thanks to their financial and technical advantages, multinational enterprises (MNEs) are key players in the deployment of capital- and R&D-intensive clean energy technologies across borders, accounting for 30% of global new investments in renewable energy (OECD, 2022[11]).

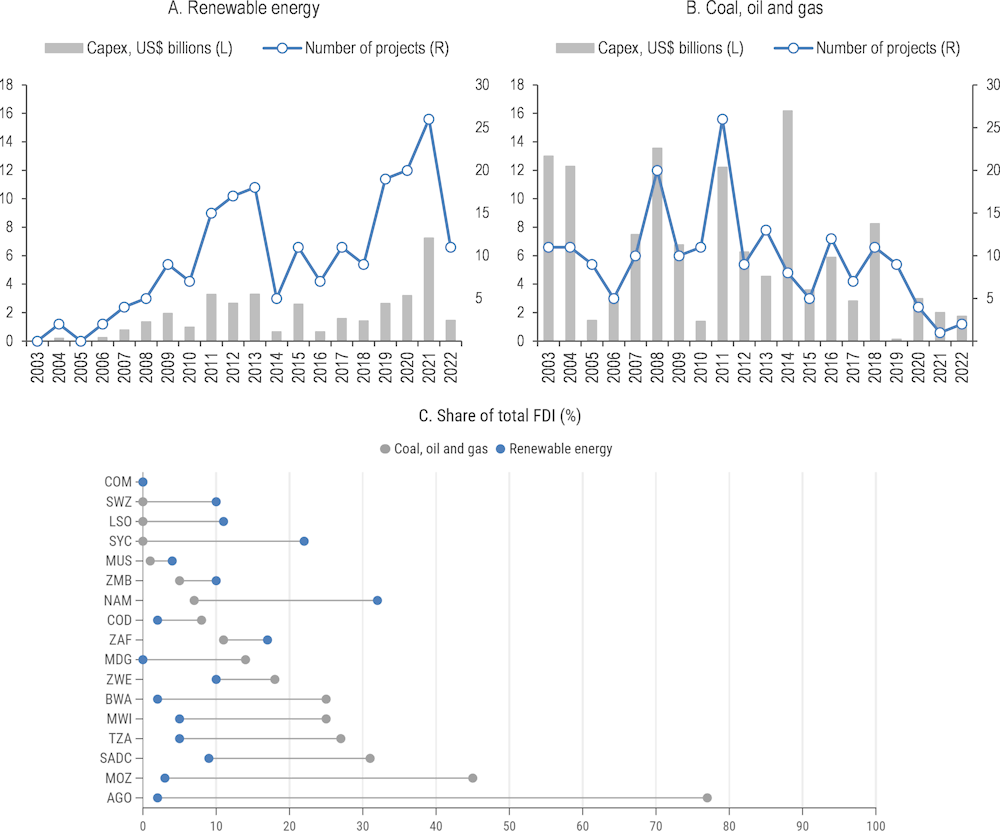

In Southern Africa, new (or greenfield) FDI projects in renewable energy have been rising steadily over the last two decades, although the value of these investments remains small in comparison to greenfield FDI stocks in fossil fuels, which still account for 78% of energy FDI stocks in the region (Figure 5.4). Nevertheless, since 2018, FDI flows to renewables have surpassed FDI flows to fossil fuels, both in volume and value, showing promising signs in terms of FDI’s growing contribution to the energy transition. The variation across countries remains wide. In Angola and Mozambique, fossil fuels account for 78% and 45% of total greenfield FDI accumulated since 2003, and over 94% of FDI stocks in the energy sector. In Tanzania, Malawi, and Botswana, fossil fuels account for over a quarter of overall greenfield FDI stocks and also dwarf renewable energy FDI. Madagascar, Zimbabwe and DRC also lag behind in terms of attracting renewable energy FDI. Conversely, in Namibia, Seychelles, Lesotho and Eswatini, renewable energy FDI dominates the energy sector and has attracted a sizeable share of greenfield FDI, ranging from 10% in Eswatini to 32% in Namibia. In Zambia and South Africa, the gap between renewable and conventional energy in terms of FDI attraction is smaller, but there is a clear trend toward greener energy.

Figure 5.4. FDI in renewable energy is rising

Note: Figure C is calculated using greenfield FDI flows accumulated over 2003‑22.

Source: OECD based on Financial Times FDI Markets (2022[12])

Policy framework for green growth and climate change

Strong government commitment to combat climate change and to support low-carbon growth, underpinned by a coherent policy framework and clear decarbonisation targets, provides investors with encouraging signals regarding the government’s climate ambitions. Setting a clear, long-term transition trajectory that is linked to the national vision or goals for growth and development is critically important to build capacity for investors to understand transition risks, and to attracting foreign investment that contributes to the country’s climate agenda.

SADC’s international commitments to green growth

SADC recognises the importance of sustainable use and management of the environment in the fight against poverty and food insecurity. SADC Member States have committed themselves to integrated and sustainable development, and climate change adaptation and mitigation. This commitment is reflected by the SADC Treaty establishing the organisation, and active participation in the negotiations and ratification of major Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs). All SADC Member States have ratified the three Rio Conventions: the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). There is, however, currently a lack of cohesive regional target-setting across all three Rio Conventions within SADC. These targets are often expressed differently between countries, while the level of detail varies in terms of commitments and implementation plans.

In addition to the Rio Conventions, SADC members have ratified or acceded to most major global MEAs on biodiversity, climate and atmosphere, land and water resources, and chemicals and waste, though some exceptions remain (Table 5.2). Four countries in the region are neither parties to the Convention on Migratory Species nor the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA), and only three have ratified the Lusaka Agreement on Co‑operative Enforcement Operations Directed at Illegal Trade in Wild Fauna and Flora, suggesting that more progress can be made in terms of protecting biodiversity. Three countries have yet to accede to the Rotterdam Convention on prior informed consent for hazardous materials and pesticides (Angola, Comoros and Seychelles), and four countries to the Minamata convention on Mercury (Angola, DRC, Malawi, Mozambique), while less than half of SADC countries are parties to the Bamako Convention remaining potentially vulnerable to illegal dumping of spent chemicals, hazardous wastes and banned pesticides. Only two countries (Namibia and South Africa) have ratified the UN Watercourses Convention, although all mainland SADC countries are party to the SADC Protocol on Shared Watercourse (discussed in greater detail below).

As of 2018, all SADC Members signed and ratified the Paris Agreement under the UNFCCC and submitted their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to the convention, joining the global collaborative effort to mitigate and adapt to climate change. All SADC members have committed to reducing their GHG emissions, albeit to varying degrees, and all but three countries in the region have submitted updated NDCs, in line with the five‑year cycle mandated by the Paris Agreement. These updated NDCs have universally provided additional information for clarity, transparency and understanding. Twelve SADC countries strengthened the adaptation component in their revised NDCs, and 11 have strengthened or added policies and actions. Only nine revised NDCs have strengthened or added sectoral targets while only five have reduced the total emissions target for 2030.

Collectively SADC NDCs are not yet aligned with the objectives of the Paris Agreement of limiting the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C. Only five countries in the region have committed to achieving net-zero GHG emissions by 2050, including Comoros which has already achieved net-zero (Table 5.3). Emissions reduction targets are specified in ways that are not directly comparable across countries, due to different time frames and business-as-usual scenarios. Eight countries have both an unconditional target, and a significantly more ambitious conditional target, and six countries only commit to emissions reductions conditional on international support. The conditions of these targets differ across countries, but frequently include access to international aid in the form of financial resources, technology transfer and capacity building. Five countries in the region do not specify any sectoral targets for emissions reductions.

South Africa is the only country to have submitted a long-term strategy document in addition to its NDC. Ambitious long-term strategies are vital since current near-term NDCs are only sufficient enough to limit warming to 2.7‑3.7°C. Moreover, long-term strategies provide a pathway to a whole‑of-society transformation and a vital link between shorter-term NDCs and the long-term objectives of the Paris Agreement. Given the 30‑year time horizon, these strategies offer many other benefits, including guiding countries to avoid costly investments in high-emissions technologies, supporting just and equitable transitions, promoting technological innovation, planning for new sustainable infrastructure in light of future climate risks, and sending early and predictable signals to investors about envisaged long-term societal changes.

Table 5.2. Multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) ratified by SADC Member States

Year of ratification / accession

|

MEA |

AGO |

BWA |

COD |

COM |

LSO |

MDG |

MOZ |

MUS |

MWI |

NAM |

SWZ |

SYC |

TZA |

ZAF |

ZMB |

ZWE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Biological diversity |

||||||||||||||||

|

AEWA |

|

2017 |

|

|

|

2007 |

|

2001 |

2019 |

|

2013 |

|

1999 |

2002 |

|

2012 |

|

Cartagena Protocol |

2009 |

2003 |

2005 |

2009 |

2003 |

2004 |

2003 |

2003 |

2009 |

2005 |

2006 |

2004 |

2003 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

|

Convention on Biodiversity |

1998 |

1996 |

1995 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1995 |

1993 |

1994 |

1997 |

1995 |

1993 |

1996 |

1996 |

1993 |

1995 |

|

CITES |

2013 |

1978 |

1976 |

1995 |

2003 |

1975 |

1981 |

1975 |

1982 |

1991 |

1997 |

1977 |

1980 |

1975 |

1981 |

1981 |

|

Convention on Migratory Species |

2007 |

|

1990 |

|

|

2007 |

2009 |

2004 |

2019 |

|

2013 |

2005 |

1999 |

1992 |

|

2012 |

|

Lusaka Convention |

|

|

|

|

1995 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1996 |

1995 |

|

|

Nagoya Protocol |

2017 |

2014 |

2015 |

2014 |

2015 |

2014 |

2014 |

2014 |

2014 |

2014 |

2016 |

2014 |

2018 |

2014 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

Chemicals and waste |

||||||||||||||||

|

Basel Convention |

2017 |

1998 |

1995 |

1995 |

2000 |

1999 |

1997 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

2005 |

1993 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

2012 |

|

Bamako Convention |

2016 |

|

1998 |

2004 |

|

|

1999 |

|

|

|

|

|

1993 |

|

|

1992 |

|

Minamata Convention |

|

2017 |

|

2019 |

2017 |

2017 |

|

2017 |

|

2017 |

2017 |

2017 |

2021 |

2019 |

2017 |

2021 |

|

Rotterdam Convention |

|

2008 |

2005 |

|

2008 |

2004 |

2010 |

2005 |

2009 |

2005 |

2012 |

|

2004 |

2004 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Stockholm Convention |

2007 |

2004 |

2005 |

2007 |

2004 |

2006 |

2006 |

2004 |

2009 |

2005 |

2006 |

2008 |

2004 |

2004 |

2006 |

2012 |

|

Climate and atmosphere |

||||||||||||||||

|

Kyoto Protocol |

2007 |

2005 |

2005 |

2008 |

2005 |

2005 |

2005 |

2005 |

2005 |

2005 |

2006 |

2005 |

2005 |

2005 |

2006 |

2009 |

|

Montreal Protocol |

2000 |

1992 |

1995 |

1995 |

1994 |

1997 |

2994 |

1992 |

1991 |

1993 |

1993 |

1993 |

1993 |

1990 |

1990 |

1993 |

|

Paris Agreement |

2021 |

2017 |

2018 |

2017 |

2017 |

2016 |

2018 |

2016 |

2017 |

2016 |

2016 |

2016 |

2018 |

2016 |

2017 |

2017 |

|

UNFCCC |

2000 |

1994 |

1995 |

1995 |

1995 |

1999 |

1995 |

1994 |

1994 |

1995 |

1997 |

1994 |

1996 |

1997 |

1994 |

1994 |

|

Vienna Convention |

2000 |

1992 |

1995 |

1995 |

1994 |

1997 |

1994 |

1992 |

1991 |

1993 |

1993 |

1993 |

1993 |

1990 |

1990 |

1993 |

|

Land and water resources |

||||||||||||||||

|

Ramsar Convention |

|

1997 |

1996 |

1995 |

2004 |

1998 |

2004 |

2001 |

1997 |

1995 |

2013 |

2005 |

2000 |

|

1991 |

2013 |

|

UNCCD |

1997 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1996 |

1997 |

1997 |

1996 |

1996 |

1997 |

1996 |

1997 |

1997 |

1997 |

1996 |

1997 |

|

UN Watercourses Convention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2014 |

|

|

|

2014 |

|

|

|

UN Convention on the Law of the Sea |

1994 |

1994 |

1994 |

1994 |

2007 |

2001 |

1997 |

1994 |

2010 |

1994 |

2012 |

1994 |

1994 |

1998 |

1994 |

1994 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on https://www.informea.org/en.

Table 5.3. NDC targets of SADC Members

GHG reduction relative to Business-As-Usual (BAU) levels

|

MS |

Unconditional target |

Conditional target |

Net-Zero Target |

LTS |

Sector Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AGO |

15% by 2025 |

25% by 2025 |

None. |

None |

Energy, AFOLU, Industry, Waste |

|

BWA |

15% by 2030 |

None |

None. |

None |

None |

|

COD |

2% by 2030 |

19% by 2030 |

None. |

None |

Energy, AFOLU, Waste |

|

COM |

1.15% by 2030 |

23% by 2030 |

Achieved |

None |

Energy, FOLU, Waste |

|

LSO |

10% by 2030 |

35% by 2030 |

None. |

None |

Energy |

|

MDG |

None |

14% by 2030 |

None. |

None |

None |

|

MOZ |

None |

40 MtCO2eq between 2020 and 2025 |

None. |

None |

FOLU |

|

MUS |

14% by 2030 |

40% by 2030 |

2070 |

None |

Energy, Transport, Waste, IPPU, AFOLU |

|

MWI |

6% by 2040 |

51% by 2040 |

2050 |

None |

Energy, IPPU, Waste, Agriculture |

|

NAM |

9% by 2040 |

91% by 2040 |

2050 |

None |

Energy, IPPU & RAC, AFOLU, Waste |

|

SWZ |

5% by 2030 |

14% by 2030 |

None. |

None |

Energy, Waste, Industry, AFOLU |

|

SYC |

None |

73.7% by 2030 |

2050 |

None |

Energy, RAC, transport, waste |

|

TZA |

None |

30‑35% by 2030 |

None. |

None |

None |

|

ZAF |

to 350‑420 MtCO2e by 2030 |

None |

2050 |

Yes |

None |

|

ZMB |

None |

25‑47% by 2030 |

None |

None |

None |

|

ZWE |

None |

40% by 2030 |

None |

None |

Energy/transport, IPPU, AFOLU, Waste |

Note: Details on the conditions of the targets can be found in the source. BAU scenarios and base years vary by country. IPPU = Industrial Processes and Product Use; AFOLU = Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use; RAC = Refrigeration and Air Conditioning.

Source: NDCs were retrieved from the official registry (https://www4.unfccc.int/sites/ndcstaging/Pages/Home.aspx).

Regional environmental co‑operation

Several legal instruments for regional co‑operation and integration in environment and climate change have been developed in SADC. These include the Protocol on Environmental Management for Sustainable Development (2014); the Protocol on Forestry (2002); the Protocol on Fisheries (2001); the Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems (2000); the Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement (1999); and Protocol on Development of Tourism (1998).

The overall objectives of the Protocol on Environmental Management for Sustainable Development are to promote sustainable use and transboundary management of the environment and natural resources, and to harmonise all existing regional instruments that deal with environmental issues. The Protocol covers environmental issues such as climate change, waste and chemicals, biodiversity, land management, and water resources, as well as cross-cutting issues on gender, science, technology, trade and investment. A total of 14 SADC Member States have signed the Protocol and ratification is at various stages, with 11 Members required to operationalise the Protocol. Despite the fact that the Protocol is not yet in force, the region has made some strides in implementation of some of the targets. These include the development of the: Regional Climate Change Strategy, the Regional Green Economy Strategy and Action Plan for Sustainable Development and the Global Climate Change Alliance Plus in the SADC region.

The Revised Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems in SADC (Revised Protocol) was the first binding agreement amongst SADC member states, illustrating the important role water plays within the region. The Revised Protocol stresses the importance of taking a basin-wide approach to water management rather than that of territorial sovereignty. It outlines specific objectives including improving co‑operation to promote sustainable and co‑ordinated management, protection and use of transboundary watercourses, and promoting the SADC Agenda of Regional Integration and Poverty Alleviation. The Revised Protocol allows countries to enter into specific basin-wide agreements, which is the approach promoted under the UN Watercourses Convention. For instance, the governments of Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa formalised the Orange‑Senqu River Commission (ORASECOM) following the regional ratification of the Revised Protocol.

Southern Africa is bestowed with forest resources covering 41% of the region’s total land area, which provide timber and non-timber forest products, domestic wood energy, and a habitat for wildlife. Forests are also important for soil protection, water conservation, food, and climate change mitigation through carbon sequestration. The 2002 Protocol on Forestry provides a policy framework for sustainable forest management in the SADC region. Objectives addressed in this protocol include increasing public awareness of forestry and capacity building. More specifically, the framework addresses research gaps, laws, education and training, the harmonisation of regional sustainable management practises, increasing efficiencies of utilisation and facilitation of trade, equitable use of local forests and a respect for traditional knowledge and uses.

The Protocol on Wildlife Conservation and Law Enforcement is an inter-state regulation affirming that member states have the sovereign right to manage their wildlife resources and the corresponding responsibility for sustainable use and conservation of these resources. The aim is to establish a common framework for the conservation and sustainable use of wildlife resources in the SADC region and to assist with the effective enforcement of laws governing those resources.

Policy framework for environmental protection

SADC countries have recognised the mutually reinforcing relationship between human rights and environmental rule of law. The constitutions of six SADC Members explicitly state the right to a healthy or balanced environment, while another eight contain clauses to ensure the protection of the environment and natural resources by the State and its citizens. Only the constitutions of Botswana and Mauritius omit these rights but have afforded them through a variety of laws, policies and visions.

SADC’s Policy and Strategy for Environment and Sustainable Development (1996) called for a departure from fragmented sectoral approaches to environmental management and urged the region to pursue a unified strategy to achieve the consistent integration of environmental impact assessment (EIA) in decision-making. Since then, SADC Members made great strides in formalising EIA into their legal frameworks, with all SADC countries now having promulgated laws in this regard. Two countries in SADC, Lesotho and Mauritius, do not have any specific EIA regulations, but have detailed guidelines for the EIA process.

SADC Members have adopted the same general approach to EIA, which is mandated under an environmental agency (e.g. the Ministry of Environment) or the Vice‑President’s Office in the case of Tanzania. EIA processes consist of similar procedures in line with principles set out by the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA), involving screening, scoping, impact assessment, approval, and monitoring. The exceptions are Angola, the DRC, Namibia and Zimbabwe, which combined the screening and scoping phases into one, and Comoros, where the environmental law does not have a system in place for screening or pre‑evaluation of small-scale projects and there is no mention of scoping or follow-up.

With few exceptions, laws and policies of SADC countries provide for the three critical procedural rights of access to information, public participation, and access to remedies, including grievance redress mechanisms and other project specific complaints processes (Table 5.4). These procedural rights are necessary to ensure that EIAs can effectively identify community concerns about development projects, and therefore critical for environmental governance. They also ensure that the human rights obligations to a clean and safe environment are protected.

Table 5.4. Common elements of EIA systems in SADC

|

Year of Act / Regulation |

Screening list |

Public participation |

Access to information |

Access to justice |

EMP & monitoring |

SEA |

Transboundary EIA |

Certified consultants |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AGO |

1998 / 2020 |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

BWA |

2005 / 2012 |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

|

COD |

2011 / 2014 |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

COM |

1995 / 2008 |

□ |

□ |

▣ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

LSO |

2008 |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

|

MDG |

1990 / 2004 |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

|

MOZ |

1997 / 2015 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

MUS |

2002 |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

▣ |

▣ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

|

MWI |

2017 / 2019 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

|

NAM |

2007 / 2013 |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

SWZ |

2002 / 2000 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

▣ |

■ |

|

SYC |

1994 / 1996 |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

■ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

▣ |

|

TZA |

2004 / 2018 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

▣ |

■ |

|

ZAF |

1998 / 2017 |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

■ |

|

ZMB |

2011 / 1997 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

■ |

□ |

|

ZWE |

2002 / 2007 |

■ |

▣ |

■ |

▣ |

▣ |

□ |

□ |

□ |

Note: ■ = Clear legal requirement in EIA laws and regulations; ▣ = Partial legal requirement (e.g. no regulations or guidelines); □ = No legal requirement. SEA = Strategic Environmental Assessment; EMP = Environmental Management Plan.

Source: Authors based on national EIA legislation and Walmsley and Patel (2020[13]).

EIA processes are most effective where key interested and affected parties are consulted at an early stage of the process, and empowered to contribute to assessing alternatives, identifying community issues and concerns and ensuring that these are addressed in the EIA report. While some level of public consultation is required as part of the EIA process in almost all SADC countries, the timing and mode of consultation vary significantly. The scope of participation ranges from full engagement of interested and affected parties to various means, including public meetings and focus groups (e.g. in South Africa), to the passive placement of the EIA report for public review and comment (e.g. in Mauritius). It is generally considered best practice to consult the public as early in the EIA process as possible, that is, in the scoping phase. Eight SADC countries (Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia) require this. Ten SADC countries require the proponent to undertake public participation during the preparation phase of the EIA. In Madagascar, Mauritius, and Seychelles, the authorities will hold public hearings as the sole means of public consultation, while in Comoros there are no regulations or guidelines on specific measures to be followed for public participation and consultation.

Lack of effective post-EIA follow-up and implementation of an Environmental Management Plan (EMP) reduces the value of the EIA process. In all SADC countries, the EIA must include measures setting out how the proponent proposes to avoid, reduce, manage or control the adverse impacts of the development on the environment in an EMP. In practice, the general standards of EMP formulation are often poor due to a lack of guidance. Compounding the situation is the general lack of post-EIA follow-up and compliance monitoring. Ten SADC countries make provisions for inspections, audits and monitoring by the authorities. In practice this is seldom achieved due to a range of factors including lack of public sector resources. Four countries (DRC, Eswatini, South Africa and Zambia) place the responsibility for project compliance monitoring and auditing on the proponent, who is required to submit regular monitoring and auditing reports to the authorities. This approach requires that the project proponent take ownership of the environmental monitoring process and the management of related risk. Only Botswana formally requires joint monitoring and auditing, with the proponent doing the day-to day compliance monitoring activities, and the authorities carrying out periodic inspections.

Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) continues to gain momentum, and much of the newer legislation requires SEAs for policies, plans and programmes, notably in ten SADC countries. South Africa has a long history of SEA practice dating back to the mid‑1990s; however, this practice has been voluntary with no formal legal framework. With the exception of Botswana, DRC and South Africa, currently no regulations or guideline set out the procedures for the implementation of SEAs, leaving considerable room for interpretation. The legislation in Madagascar and Malawi does not refer to SEAs specifically, but both countries require an EIA of new national policies, plans and programmes. The Environmental Protection Act of Mauritius lists the activities that require a SEA, but no other mention is made in the main body of the act. The only reference to SEA is a definition in Seychelles, and no mention of SEAs is made in the environmental laws of Angola, Comoros, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe. In Namibia and Mozambique, several SEAs have nevertheless been carried out for a variety of sectors, including mining, agriculture, forestry development, and coastal zone planning.

The application of EIA principles to the assessment of transboundary impacts of investment remains limited in SADC, and only Zambia provides a framework for the control and restriction of any contaminants that may have a regional or global effect. In Botswana, Eswatini and Tanzania, environmental authorities are required to initiate a consultative process with the relevant authorities of countries that may be significantly adversely affected by a proposed activity. In Lesotho, the EIA report must include an indication of whether the environment of any other State is likely to be affected by the proposed project and what mitigation measures are to be undertaken, but there is no reference to consultation with the concerned countries. In Malawi, the EIA Guidelines mention transboundary assessment as one of the components to be included in the EIA report but there is no mention of it in the corresponding legislation. All other SADC countries do not require transboundary EIA in their environmental laws, but may be signatories to trans-boundary agreements which require sharing of information (e.g. Orange‑Senqu River Commission, the SADC Protocol on Shared Watercourse Systems), as well as some trans-frontier conservation initiatives.

Ensuring a high level of professional quality and conduct of EIA practitioners is central to the effectiveness of the EIA process, and for this reason, it is good practice to introduce a certification scheme for EIA practitioners and consultants. At present, only South Africa, Botswana, Eswatini and Tanzania have a statutory requirement for certification of environmental assessment practitioners. Angola, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe have put in place registration systems for EIA practitioners based on professional criteria, which also afford some degree of quality control. Mauritius and Zambia require EIA consultants and their qualifications to be sent to the authorities for approval before commencing the EIA, affording a lower level of quality control that hinges on the accuracy of the information provided by the consultants. The lowest level of quality assurance is provided in DRC and Malawi, where the environmental agency has a list of approved consultants. In Comoros and Madagascar there is no certification or registration system for EIA practitioners. There is, therefore, little control over the professionalism and conduct of EIA consultants in the region.

Policy approaches to promote green investment

Uncertainty and unpredictability are among the greatest barriers to green investment. Too often the reason governments fail to attract green investment is due to the lack of an enabling environment for investment. Green investors are no different than any other in requiring a stable, predictable, and transparent investment environment in which to identify bankable projects. Thus, efforts to mobilise green investment will fail to meet their intended target unless governments ensure a regulatory climate that provides investors with fair treatment and confidence in the rule of law. The widely accepted features of this enabling environment are detailed in the OECD Policy Framework for Investment (PFI) which helped to inform SADC’s own Investment Policy Framework.

At the same time, openness, stability, and fair treatment are not enough to channel private investment towards green growth and decarbonisation objectives. In other words, policies conducive to FDI will not automatically result in a substantial increase in green or climate‑aligned FDI. Policymakers will also need to improve specific enabling conditions for green investment by developing policies and regulations that systematically internalise the cost of environmental externalities like carbon emissions. Targeted financial, technical and information support can also help address market failures reduce the competitiveness of climate‑aligned investments.

Stimulating investment in green technologies

Private investors do not internalise the positive spillovers of low-carbon investments and are likely to under-invest in related technologies and skills compared to socially optimal levels. Targeted financial and technical support by the government is therefore warranted but must be transparent, time‑limited and subject to regular review. Studies have shown that the variations in the cost-effectiveness of these technology support policies depend on the country context rather than on the specific tool used. In general, government support should decrease over time as the technology matures (OECD, 2022[11]). As noted previously, FDI in renewable energy is picking up in some SADC countries, but still considerably lags behind FDI in fossil fuels overall. Targeted measures to accelerate investments in the renewable energy sector can be an effective way to decarbonise the region and promote green growth.

Many SADC Member States have put in place incentives for renewable energy products and technologies. The most widely used forms of financial support include subsidies and grants for electrification programmes, tax exemptions on renewable energy equipment and generation, and tariff-based schemes like feed-in-tariffs (FiTs), public auctions and net-metering schemes (Table 5.5). Only South Africa has developed a carbon offset market since 2005, and has recently introduced a carbon tax to curb GHG emissions across sectors (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. South Africa’s carbon tax and offset market

Carbon pricing instruments (e.g. carbon tax) internalise the climate costs of carbon emissions and provide a technology-neutral case for low-carbon investment and consumption. Carbon offset markets allow companies to reduce the volume of taxable emissions by investing in specific projects or activities that reduce, avoid, or sequester emissions, and are developed and evaluated under specific methodologies and standards, which enable the issuance of carbon credits. Combining carbon offset markets and carbon pricing provides incentives for emissions abatement where it can be done at least cost, and also supports investment into the innovation required to lower the cost of emerging climate technologies. However, setting the carbon price too low results in little incentive to invest in carbon abatement.

South Africa introduced a carbon tax in June 2019, as one of the mix of measures for supporting climate change mitigation action. A key design feature of the carbon tax is the carbon offset allowance which provides flexibility to firms to reduce their carbon tax liability by either 5% or 10% of their total GHG emissions by investing in specific projects that are eligible for the issuance of carbon credits. The carbon offset system seeks to encourage GHG emission reductions in sectors or activities that are not directly covered by the tax, like public transport, agriculture, forestry and other land use, and waste. The new draft framework seeks to keep the domestic market in line with international standards which must be measurable, permanent, independently verifiable, unique and traceable.

Placing an adequate price on GHG emissions is of fundamental relevance to internalise the external cost of climate change in the broadest possible range of economic decision making and in setting economic incentives for clean development. There are, however, concerns that South Africa’s current price on carbon is not enough to significantly contribute to reductions. According to the WWF, the current effective rate, paid once all allowances are taken into account, is equivalent to only 0.1‑0.5% of the turnover of the highest emitters and will not be sufficient to meaningfully curb emissions. Moreover, the carbon tax rate was set to increase annually by inflation plus 2% until 2022, and annually by inflation, thereafter, meaning that the carbon tax no longer increases in real terms. Further raising the carbon tax and redistributing the revenues to lower-income households and help deliver a just transition.

Source: OECD (2022[14]); Republic of South Africa (2022[15]); WWF (2018[16])

The most widely used tax incentives to promote renewable energy include import tax and VAT exemptions on related machinery and equipment, provided by the majority of SADC countries. Four SADC Members (Mauritius, Seychelles, South Africa, and Zambia) also provide accelerated depreciation allowances on capital investment, which have the advantage of naturally providing diminishing fiscal benefits as an investment project matures. Angola, Mozambique and Zimbabwe offer corporate income tax (CIT) reductions or exemptions for a predefined period of time, which are potentially very costly in terms of forgone revenues. The same three countries simultaneously offer similar CIT tax reductions for investments in fossil fuels, eroding the tax base and reducing the ultimate effectiveness of efforts to promote clean energy investment. A similar misalignment is observed in Madagascar, Zambia and South Africa, where fossil fuels and renewable energy enjoy comparable tax allowances. In addition, many of these countries subsidise fossil fuel consumption either explicitly or implicitly, hampering the effectiveness of climate policies more generally (Box 5.2). These countries would benefit from categorising green and non-green activities according to emerging taxonomies and phasing out or scaling down financial and fiscal incentives granted to non-green activities, while implementing more targeted measures to ensure energy access and affordability.

Tariff based schemes like renewable energy FiTs and auctions have become an integral part of policy instruments to promote renewable energy investment in Southern Africa, and are provided by all SADC Members with the exception of DRC and Comoros. These instruments reduce the risk of private investments by guaranteeing a predetermined price (or tariff) for the electricity generated for a predefined period of time. FiTs schemes have been put in place by nine SADC countries and are typically combined with guaranteed access to the grid for renewable generators. A key drawback of FiTs is that setting the right tariff is a complex exercise with the rapidly decreasing cost of the technologies, particularly in young markets where government capacity in the design of FiTs may be low and there may be asymmetry of information between regulators and companies. Indeed there has been evidence of limited effectiveness of the FiT scheme in Malawi (OECD, forthcoming[17]).

Public auctions have the advantage of overcoming such informational asymmetries and promoting cost efficiency by allowing for a market-based and competitive determination of tariffs. This has led a number of SADC countries including Botswana, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Zimbabwe to opt for auctioning renewable capacity to determine the price of the FiT. While auctions are well-suited for established projects, they transfer higher risk to investors, and a number of SADC countries (Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia) opt for a hybrid approach combining FiTs and auctions.

Net metering is a billing mechanism that credits solar energy system owners for the electricity they add to the grid. As such, net metering schemes can be a vital policy option to encourage community-based small scale renewable energy producers, while also encouraging energy efficiency. Growing populations and increasing shares of SMEs in Southern Africa have amplified the demand for small-scale decentralised renewable energy projects. South Africa and Namibia were the first countries to use net-metering schemes, but they have now been adopted by ten SADC countries.

Table 5.5. Financial support for renewable energy

|

|

Grants & loans |

Tax incentives |

Tariff-based schemes |

Carbon markets |

Taxes on energy use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AGO |

|

CIT, Import tax |

FiT, Net-metering |

|

|

|

BWA |

National PV Rural Electrification Programme |

|

Auctions |

|

|

|

COD |

National Electrification Fund |

Import tax, VAT |

|

|

|

|

COM |

PASEC |

Import tax, VAT |

|

|

|

|

LSO |

|

Import tax, VAT |

FiT, Net-metering |

|

|

|

MDG |

|

Tax allowance, Import tax, VAT |

Auctions |

|

|

|

MOZ |

|

CIT, Import tax, VAT |

FiT, Net-metering |

|

|

|

MUS |

Technology & Innovation Scheme, Energy Scheme for SMEs |

Accelerated depreciation |

FiT 2010 (ended 2012), Auctions, Net-metering |

|

|

|

MWI |

Rural Electrification Fund |

Import tax, VAT |

FiT, Auctions, Net-metering |

|

Vehicle Tax |

|

NAM |

|

|

FiT 2015, Auctions, Net-metering |

Under development |

|

|

SWZ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

SYC |

SEEREP, SME Laon, PV rebate, Solar Cooling Storage Project |

Accelerated depreciation, VAT |

Auctions, Net-metering |

|

|

|

TZA |

TEDAP, SREP |

Import tax, VAT |

FiT, Net-metering |

|

|

|

ZAF |

REFSO, GEF Special Climate Change Fund |

Accelerated depreciation, Import tax |

FiT, Auctions, Net-metering |

Carbon market since 2005 |

Fuel Levy, Carbon Tax, Environmental Levy |

|

ZMB |

|

Accelerated depreciation, Import tax, VAT |

FiT, Auctions |

|

|

|

ZWE |

|

CIT, Import tax, VAT |

Auctions, Net-metering |

|

|

Source: OECD FDI Qualities Mapping

Box 5.2. Reforming fossil fuel subsidies to align incentives with climate goals

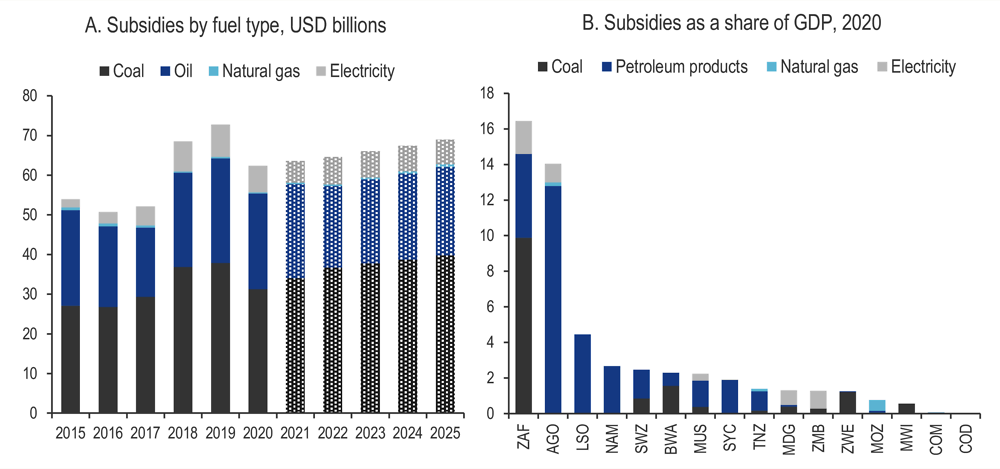

Overall, fossil fuels remain highly subsidised in Southern Africa, with total explicit and implicit subsidies amounting to USD 62 billion in 2020, and projected to rise in subsequent years (IMF, 2023[18]). The level of subsidises varies considerably across countries, reaching as high as 16% and 14% of GDP in South Africa, and Angola, respectively, and lower than 2% of GDP for the majority of SADC countries. The majority of countries subsidies petroleum products, albeit to varying degrees, although coal still dominates subsidised fuels in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Malawi. Following the surge in fuel prices since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic and exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, subsidy levels are set to rise with fuel prices, which may reduce government capacity to promote clean energy.

Governments may resort to more targeted tools than subsidies on energy use to improve energy access and affordability. Phasing out subsidies could free up public funds for targeted support to low-income groups to ensure that vulnerable groups, which also tend to be those that are disproportionately affected by climate change, will be able to access clean and affordable energy (OECD, 2021[59]). However, potential adverse social impacts of phasing out the subsidies must be taken into consideration in order to deliver a just and green transition. Adequate compensation and support measures for those affected by subsidy reform should be put in place.

Figure 5.5. Fossil fuel subsidies in SADC

Note: Time series in constant 2021 prices; values from 2021 to 2025 are projections.

Source: Authors based on IMF Climate Change Indicators (2023[18]) https://climatedata.imf.org/

Building green capabilities and addressing informational barriers to green investment

Technical support is a useful tool for reducing the environmental footprint of investments, building capabilities related to green technologies, and promoting green innovation and spillovers. The majority of SADC countries offer technical support to develop renewable energy capabilities, in particular of workers, often delivered in partnership with development co‑operation agencies (Table 5.6). For instance, the Southern African Solar Thermal Training & Demonstration Initiative (SOLTRAIN) is a regional capacity building programme implemented in Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia and Zimbabwe, with financial and technical support from the Austrian Development Agency. Similarly, the Green People’s Energy for Africa initiative aims to improve the conditions for decentralised energy supply in rural areas in Mozambique, Namibia, and Zambia, and is implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale (GIZ). Malawi and Tanzania also have dedicated renewable energy training and testing centres. Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa and Zambia additionally offer technical support to improve the energy performance of SMEs and facilitate technology transfer. These kinds of initiatives are particularly useful to promote spillovers from foreign to domestic firms and further accelerate the green transition.

Green technology parks, incubators and accelerators can also be tailored to support businesses in finding innovative solutions to reducing GHG emissions, and create green innovation hubs that attract talent and investors. South Africa is the only country in the region to have developed a variety of different types of green technology parks. The Atlantis Greentech Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the Western Cape is a noteworthy example that makes use of a range of investment attraction tools, including streamlined investment facilitation, preferential land use, infrastructure provision, easy access to major transport hubs, and SEZ-specific customs and fiscal regimes. The Global Eco-Industrial Parks Programme (GEIPP), launched in 2020, seeks to transform traditional industrial parks into Eco-Industrial Parks by improving resource use and fostering industrial synergies in existing industrial parks in the country. Through this programme, South Africa is striving to develop the first zero solid-waste eco‑industrial park in Africa, known as the Limpopo Eco-Industrial Park. The South Africa Renewable Energy Business Incubator (SAREBI), established in 2012, seeks to help energy entrepreneurs in the renewable energy and energy efficiency sectors to build scalable, profitable and sustainable businesses. By upgrading the capabilities and innovation potential of domestic industry, these parks and incubation facilities can heighten competitive pressures and encourage FDI spillovers that arise from imitation of foreign technologies and operating procedures.

Table 5.6. Technical and information support for green investments

|

MS |

Technical support |

Information support |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Training & skills development |

Business & supplier development |

Science & technology parks |

Green promotion & facilitation |

Public awareness campaigns |

Disclosure, certification & labelling |

|

|

AGO |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard |

||||

|

BWA |

SOLTRAIN |

EELA campaign |

||||

|

COD |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard |

||||

|

COM |

EELA campaign |

|||||

|

LSO |

SOLTRAIN |

EELA campaign |

||||

|

MDG |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard |

||||

|

MOZ |

SOLTRAIN, Green People’s Energy |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard |

|||

|

MUS |

EELA campaign |

|||||

|

MWI |

Testing Centre in Renewable Energy Technologies |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard |

|||

|

NAM |

SOLTRAIN, Green People’s Energy |

Concentrated Solar Power Tech Transfer |

EELA campaign |

|||

|

SWZ |

EELA campaign |

|||||

|

SYC |

Grid-connected Rooftop PV Systems project |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard, SYC Sustainable Tourism Label |

|||

|

TZA |

Renewable Energy Training Centre |

EELA campaign |

EITI Standard |

|||

|

ZAF |

Green Skills Program, Solar Training, SOLTRAIN |

Industrial Energy Efficiency Program |

Atlantis SEZ, SAREBI, GEIPP, Limpopo Eco-Industrial Park |

Atlantis SEZ, Greentech Guide, WISP Investment Prospectus |

Illegal dumping awareness campaign, EELA campaign |

National GHG Emissions Reporting Reg., Green Star Rating |

|

ZMB |

Green People’s Energy Training, Green Jobs in Construction |

Online Course on Green Tech for MSMEs, PDDREP Training for SMEs |

Energy Sector Profile |

EELA campaign, Keep Zambia Clean, Green and Healthy campaign |

EITI Standard |

|

|

ZWE |

SOLTRAIN |

|||||

Source: OECD FDI Qualities Mapping.

In addition to technical support, information and facilitation services can help reduce informational barriers and asymmetries that lead to sub-optimal investment and consumption choices, and generally result in under-investment in green technologies. For instance, lack of awareness on the energy performance of household appliances leads to an inability of consumers to interpret the impact of energy prices on the operational costs of one product relative to another, meaning that price signals do not influence purchasing behaviour as expected. Measures to raise public awareness and understanding of energy and environmental performance, including information campaigns, product labelling schemes, certification and disclosure requirements can help alleviate these information barriers.

Environmental awareness raising campaigns focus predominantly on energy efficiency. For instance, the SADC Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency (SACREEE) is responsible for implementing the Energy Efficient Lighting and Appliances (EELA) project in Southern Africa, to raise awareness about the benefits of energy efficient technologies through television, radio, social channels and outreach events. South Africa and Zambia also publish sector-specific guidebooks and green investment opportunities listings to overcome information barriers that might hinder green investments. In terms of voluntary disclosure and reporting, ten SADC countries have committed to strengthening transparency and accountability of their extractive sector management by implementing the EITI Standard, which can play an important role in building awareness of how the transition will affect extractive sector activities and revenues and in supporting the responsible and transparent production of minerals that are critical for a sustainable future. South Africa furth introduced a system for the transparent reporting of GHG emissions, which will be used to maintain a National Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

References

[2] Browne, C., C. Kelly and C. Pilgrim (2022), Illegal Logging in Africa and Its Security Implications, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/illegal-logging-in-africa-and-its-security-implications/.

[8] CRED (2023), EM-DAT: The International Disaster Database, https://www.emdat.be/.

[12] Financial Times (2022), FDI Markets: the in-depth crossborder investment monitor from the Financial Times, https://www.fdimarkets.com/.

[10] IEA (2022), GHG Emissions from Energy, http://iea.org.

[6] IEA (2022), Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy.

[18] IMF (2023), Climate Change Indicators, https://climatedata.imf.org/.

[7] ISS (2021), Climate finance isn’t reaching Southern Africa’s most vulnerable, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/climate-finance-isnt-reaching-southern-africas-most-vulnerable.

[11] OECD (2022), FDI Qualities Policy Toolkit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7ba74100-en.

[14] OECD (2022), Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Turning Climate Targets into Climate Action, OECD Series on Carbon Pricing and Energy Taxation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9778969-en.

[17] OECD (forthcoming), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2023.

[15] Republic of South Africa (2022), South African Carbon Offsets Programme: Draft Framework for Approval of Domestic Standards for Public Comment, https://www.energy.gov.za/files/esources/kyoto/2022/Draft-Framework-for-Approval-of-Domestic-Standards-for-Public-Comment.pdf.

[3] SBDC (2014), Country profiles - Madagascar, https://www.cbd.int/countries/profile/?country=mg.

[4] UNDP-OPHI (2022), Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2022: Unpacking deprivation bundles to reduce multidimensional poverty, https://hdr.undp.org/content/2022-global-multidimensional-poverty-index-mpi#/indicies/MPI.

[9] University of Notre Dame (2022), “ND-GAIN Index”, https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/matrix/.

[13] Walmsley, B. and S. Husselman (2020), Handbook on environmental assessment legislation in selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) and Southern African Institute for Environmental Assessment, https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/2eb50196/files/uploaded/SADC%20Handbook.pdf.

[5] Wolf, M. et al. (2022), 2022 Environmental Performance Index., Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy, http://epi.yale.edu.

[1] World Bank (2023), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/.

[16] WWF (2018), Everything you didn’t know and should ask about the carbon tax, https://wwfafrica.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_carbon_tax_qanda_final.pdf?24601/Everything-you-didnt-know-you-should-ask-about-the-carbon-tax.