This chapter highlights the importance of responsible business conduct (RBC) for the SADC region and presents the key elements of RBC. It then provides an overview and analysis of policies and initiatives relevant to RBC at both regional and national levels within SADC.

Sustainable Investment Policy Perspectives in the Southern African Development Community

6. Promoting and enabling responsible business conduct

Abstract

In recent years a combination of regulatory, political and market pressures have driven uptake of responsible business practices globally. In SADC, policy makers, civil society, and business have recognised the importance to strengthen responsible business conduct (RBC) at both regional and national levels. SADC institutions and governments have established frameworks and policies that can serve as a foundation to further promote and enable RBC. However, there is a discrepancy in the pace at which countries and businesses have moved forward with the RBC agenda. Gaps remain to implement and enforce policies, to develop government action plans in line with international RBC standards, and to enhance stakeholder awareness and business capacity to conduct due diligence.

Importance of promoting and enabling RBC for SADC

Terms such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Business and Human Rights (BHR) have been used to reflect the expectation that businesses should consider non-financial impacts as part of their core business considerations, rather than treating them as add-ons. RBC is more specific in that it sets the expectation that all businesses, regardless of their legal status, size, ownership structure, or sector, should avoid and address negative consequences of their operations while contributing to sustainable development wherever they operate. This means that businesses need to consider impacts on people, the planet, and society, such as human rights, labour rights, environmental and corruption risks that may be caused or contributed to by their business activities, their supply chains, and their business relationships.

Enabling RBC is key to attract quality investment, foster trade, and ensure that business activities contribute to broader value creation and sustainable development. The importance of implementing and enabling RBC has gained international recognition from business, trade, and investment perspectives. Enterprises have confirmed that implementing RBC practices and considering risks beyond financial materiality can be beneficial for their business. For example, the implementation of due diligence and higher sustainability requirements has proven to make companies more resilient to external shocks and crises. In a response to an OECD firm-level survey on RBC in Latin America, 75% of firms indicated that responsible practices such as due diligence have helped them navigate the COVID‑19 crisis, notably by mitigating risks (OECD, 2021[1]). Similar results were found in a global study conducted by the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA, 2021[2]).

For the 16 SADC countries, RBC is particularly relevant due to the structure of their economy and their integration into value chains, which relies on the extractive and the agricultural sectors. These industries have the potential to generate significant revenues and employment opportunities, but they are also associated with significant RBC risks such as human rights abuses and environmental degradation.

Agriculture plays a significant role in the socio‑economic development of most member countries in SADC. It contributes to 70% of employment, 13% of exports and 66% of the intra-regional trade value (SADC, 2020[3]). The sector relies on smallholder farmers, and particularly women in the crop, livestock, and fisheries value chains and is almost entirely based on informal labour in SADC (ILO, 2020[4]). It is highly vulnerable to risks such as food insecurity and climate change, especially given that 90% of the region’s crop production such as maize, millet and sorghum depends on precipitation. Agriculture’s contribution to GDP varies greatly among SADC Member States. In Botswana, South Africa, Mauritius, and Zambia, agriculture accounts for less than 3% of GDP. On the other hand, in Madagascar, Mozambique, and Malawi, it makes up more than 26% of GDP. Except for South Africa, which also produces wine and citrus fruits, SADC economies are generally at similar levels of agricultural development and produce comparable products such as grains (maize, wheat, and sorghum), nuts, and vegetables (SAIIA, 2021[5]).

The region’s economy and exports are heavily focussed on its abundant natural mineral resources and extractive products. Southern Africa is home to half of the world’s vanadium, platinum, and diamonds, along with 36% of gold and 20% of cobalt (SADC, 2020[6]). Oil, gold, platinum, diamonds, copper, and cobalt accounted for around 72% of the region’s total exports in 2021 (OEC, 2023[7]). More than half of the world’s cobalt is sourced in DRC, which multinational companies use to manufacture rechargeable lithium-ion batteries, electronic devices, and electric cars (ILO, 2019[8]). Moreover, copper, cobalt, and platinum, for instance, have rapidly gained importance in the world economy being indispensable for the climate and green energy transition. The extractive sector is therefore crucial to the region’s economy, employment, and foreign exchange earnings.

The agricultural and mining sectors in SADC have been associated with adverse social and environmental impacts in the past. The agricultural sector in SADC is linked to pertinent RBC risks, such as deforestation, weak land tenure rights for women, and child labour (SADC, 2020[9]; WFP, 2021[10]). Child labour is also an issue in mining, involving extremely hazardous working conditions and exploitation such as in cobalt supply chains in DRC (ILO, 2019[8]). Another negative impact of the mining sector in SADC is the spread of lung diseases such as tuberculosis and silicosis. The incidence of tuberculosis among miners is three to four times greater than that of the general population, and 89% of miners are believed to have latent tuberculosis due to exposure to silica dust, poor living and working conditions, and co‑infections (NEPAD, 2023[11]).

Implementing and enabling RBC is key for SADC to address environmental, labour, and human rights risks in the minerals and agricultural sectors and thereby improve market access opportunities. This importance is further reinforced by increasing regulatory expectations related to RBC. In Southern Africa these expectations are driven notably by regulatory developments related to RBC in key exports markets such as the EU. Moreover, the ongoing implementation process of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and its Protocol on Investment (in particular Article 38 on CSR) represents a key opportunity to further leverage RBC given the projected increase of both intra- and extra-African trade in a single continental market (UNECA/ FES, 2022[12]).

In addition to improved export market access, strong RBC policies dealing with labour standards, tenure rights over natural resources, human rights, anti-corruption, and integrity can contribute to attract more and higher quality investment to SADC countries. An OECD survey on FDI decisions found that strong and effective laws governing RBC- related issues represented the area, which had the strongest positive effect on encouraging investment in foreign agri-food markets (Punthakey, 2020[13]). Regional panel data analyses have further found that African and SADC economies having companies with robust RBC practices including on anti-corruption tend to attract more FDI (Agyemang, et al, 2020[14]; Chamisa, 2020[15]).

Key elements of RBC

The three main international instruments on RBC

The three main instruments that have become key reference points for responsible business globally, are the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (the OECD MNE Guidelines), the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), and the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy. These instruments are aligned with and complement each other in the following areas (UN; OECD; EU; ILO, 2019[16]):

Framework for all companies. International RBC standards set the expectation that all companies, regardless of their size, sector, operational context, ownership, and structure, should avoid and address adverse impacts and contribute to the sustainable development of the countries in which they operate.

Common understanding of impact. The instruments set out that the impact of business activities goes beyond the impact on the company itself and refers to the impact business activities may have on human rights – including labour rights – the environment and society, both positive and negative. The instruments establish a common understanding that enterprises can cause, contribute to, or be directly linked to adverse impacts, and they provide a framework for how enterprises should avoid and address them.

Conducting due diligence. Businesses should undertake due diligence to identify, prevent, and mitigate their actual and potential negative impacts and account for how those impacts are addressed. This process involves meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups and other relevant stakeholders.

Responsibility throughout the supply chain. Responsible business covers not only impacts that a company may cause or contribute to through its own activities but also those impacts directly linked to an enterprise’s operations, products, or services through its business relationships. This includes business partners, entities in the value chain such as subsidiaries, suppliers, franchisees, joint ventures, investors, clients, contractors, customers, consultants, financial, legal, and other advisers, and any other non-state or state entities.

Access to remedy. As part of their duty to protect against business-related adverse impacts, states are expected to take appropriate steps to ensure, through judicial, administrative, legislative, or other appropriate means, that those affected have access to effective remedy when such abuses occur within their territory and/or jurisdiction. In addition, where companies identify that they have caused or contributed to adverse impacts, they are expected to address them by providing remedy, and they should provide for or co‑operate in this remediation through legitimate processes.

The OECD MNE Guidelines on RBC are the most comprehensive international instrument on RBC, providing recommendations to businesses in all areas of RBC. The Guidelines are part of the OECD Declaration on International Investment and Multinational Enterprises, which has 51 adherent countries. These countries have set up a unique implementation mechanism, the National Contact Points for Responsible Business Conduct (NCP), which promote the MNE Guidelines and handle cases referred to as “specific instances” as a non-judicial grievance mechanism in case of alleged violations of the OECD MNE Guidelines. This mechanism is accessible for stakeholders worldwide. Any trade union, civil society organisation or community can file a complaint which involves companies headquartered in one of the 51 adherent countries (OECD, 2023[17]).

While no SADC Member States has adhered to the Guidelines yet, several cases have been filed with respect to RBC issues that have arisen in the region. Between 2001 and 2022, 47 specific instances have been submitted in relation to business operations in SADC host countries. Most of them concern the mining sector and are linked to employment and labour issues. An example of a concluded specific instance relating to business operations in the SADC region is summarised in Box 6.1.

Box 6.1. Specific instance submitted to the Dutch NCP

In December 2015, the Dutch NCP received a submission from three individuals involving Heineken, a Dutch multinational and its subsidiary Bralima operating in the DRC. The three individuals stated that Bralima had not observed the OECD MNE Guidelines in the dismissals of 168 former employees in the DRC between 1999 and 2003.

In its initial assessment published in June 2016, the Dutch NCP accepted the specific instance for further consideration. The NCP offered its mediation services which both parties accepted. The dialogue was conducted under the chairmanship of the NCP and resulted in an agreement between the parties. The NCP was asked by the parties to monitor these next steps to ensure an objective, neutral and due process. Heineken also indicated that it would draw up a policy, including guidelines, on how to conduct business and operate in volatile and conflict-affected countries.

In April 2022, the Dutch NCP published a follow up statement acknowledging that the company had made important progress in developing and implementing RBC policies within the Heineken Group. The NCP further noted that compliance with the corporate governance principles should continue to be part of an ongoing monitoring process within the Heineken Group. The NCP concluded that the agreement reached by the parties had been fully implemented.

Source: Former employees of Bralima & Heineken and Bralima, http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/database/instances/nl0027.htm

Risk-based due diligence

As laid out in the international instruments on RBC, due diligence stands at the heart of the implementation of RBC, which requires companies to identify, prevent and mitigate adverse impacts, and account for how they address these impacts. This process means considering risks not only to the company but also those that companies can cause or contribute to along the supply chain.

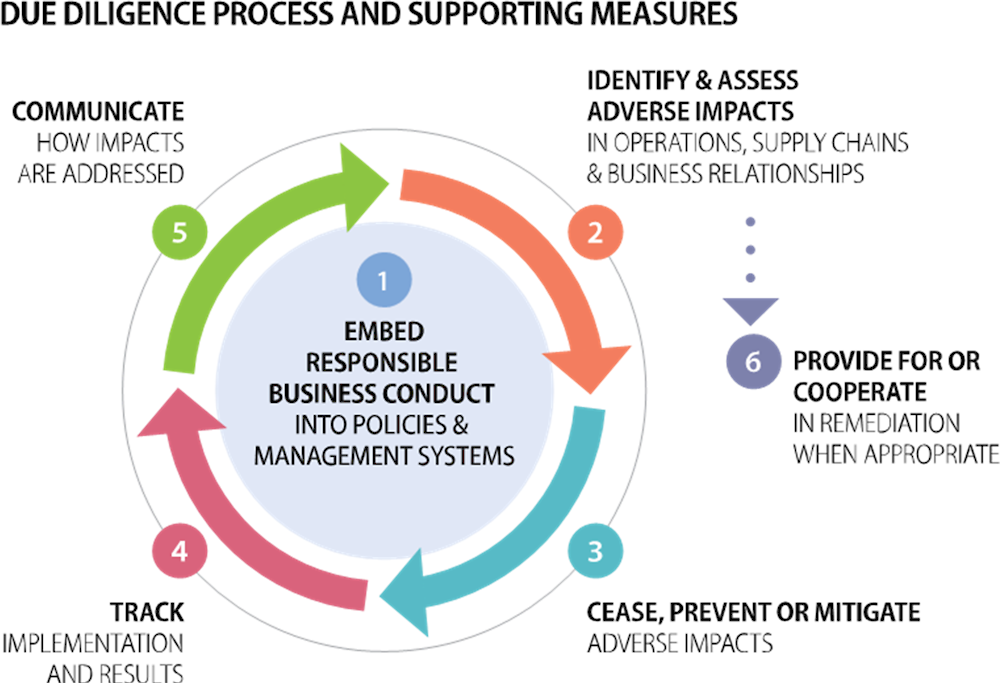

The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for RBC provides a six‑step process for conducting risk-based due diligence that can be used by any enterprise, irrespective of its size, location, or industry. The steps include embedding RBC into the enterprise’s policies and management systems, identifying and assessing adverse impacts, ceasing, preventing, or mitigating adverse impacts, tracking implementation and results, communicating how impacts are addressed, and providing for or co‑operating in remediation when appropriate. The OECD also provides tailored recommendations for specific sectors, including agriculture, minerals, garments and footwear, and finance (OECD, 2018[18]).

Figure 6.1. The risk-based due diligence process and supporting measures

Governments worldwide are increasingly enshrining due diligence expectations in their laws. As of now, 75% of OECD countries have either introduced or are in the process of introducing some form of regulation that incorporates due diligence requirements, such as disclosure laws, conduct requirements, and product and trade bans. France, Germany, Switzerland, and Norway are among the first countries to have introduced comprehensive legislation that mandates companies to carry out effective due diligence processes. At the regional level, in 2022 the EU adopted a legislative proposal which aims to establishes mandatory due diligence that applies to both EU and non-EU companies, named Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (OECD, 2023[19]; EC, 2022[20]).

Policies and initiatives relevant for RBC in SADC

To promote the implementation of responsible business practices, it is necessary to have a supportive legal and policy environment at both national and regional levels. Governments have a role to play in creating conditions that drive, support, and encourage RBC. This involves establishing and enforcing legal frameworks in all relevant areas where businesses interact with people, the planet, and society, as outlined in the OECD’s Recommendation on the Role of Government in Promoting Responsible Business Conduct (OECD, 2023[21]).

SADC policy frameworks to promote and enable RBC need further development

At the regional level, SADC has developed overarching, thematic and sectoral policies, which relate to RBC and international RBC standards. While these frameworks provide an important first step towards acknowledging and addressing RBC issues, SADC policy frameworks to promote and enable RBC need further development.

Overarching frameworks at SADC level

SADC has developed common policies and frameworks notably the SADC Protocol on Finance and Investment and the SADC Investment Policy Framework, which aim to create a favourable environment for investment in the region. These frameworks broadly refer to RBC and the use of international RBC standards, but do not provide further guidance on the promotion of RBC in different policy areas.

The SADC Protocol on Finance and Investment signed in 2006 aims to foster harmonisation of the financial and investment policies of the Member States. It requires all SADC countries to develop strategies for attracting and facilitating investment in their legislations. Annex 1 of the protocol regarding co‑operation on investment includes Article 10 on “Corporate Responsibility”. However, this article solely refers to the fact that foreign investors shall abide by the laws of the Host State and does not specify the scope or definition of corporate responsibility (SADC, 2006[22]).

The 2016 SADC Investment Policy Framework is based on the OECD Policy Framework for Investment and has become a reference instrument for investment-related reforms among SADC Member States. The framework directly refers to the promotion of RBC. SADC has also developed indicators to benchmark and monitor the Members States’ progress in implementing the Investment Policy Framework in collaboration with the OECD, which includes RBC as one of the action areas (AUC/OECD, 2022[23]).

Moreover, SADC has developed a Model Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) Template in 2012, which aims to guide Members States through any given investment treaty negotiation. The second and updated version of the Template was published in 2017. It includes provisions that deal with the respect for human rights, the promotion of labour standards, the protection of the environment, or the fight against corruption without making direct reference to the OECD MNE Guidelines. For instance, Article 10 includes a common obligation against corruption. Article 13 further requires investors to conduct environmental and social impact assessments prior to investments. Article 15 sets out minimum standards for human rights, environment, and labour. It specifically refers to the corporate duty of investors to respect human rights and related international standards. Moreover, Article 22 establishes the mandatory obligation of states not to lower labour or environmental standards to attract investment (SADC, 2017[24]). According to publicly available information regarding the BITs of SADC Member States concluded since 2017, it remains unclear whether these RBC related provisions of the SADC Model BIT Template have been included in any recent agreement (UNCTAD, 2023[25]).

Further overarching SADC frameworks refer to issues related to RBC but do not make a direct link to business conduct. The SADC Vision 2050, for instance, includes the objective to achieve the sustainable utilisation and conservation of natural resources and effective management of the environment without referring directly to the role of the private sector (SADC, 2020[26]). Similarly, the SADC Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan 2020‑30 sets out the strategic objective to strengthen human rights but does not refer to RBC in this context (SADC, 2020[3]).

Thematic frameworks at SADC level

Putting in place and maintaining an appropriate legal and regulatory framework that is continuously implemented and effectively enforced in the areas of the OECD MNE Guidelines is key to enable RBC. SADC has developed a range of thematic frameworks, in this regard, in particular on human rights, labour rights, the environment, anti-corruption, and consumer protection (see overview in Table 6.1). At the same time, many of these frameworks do not refer to the role of business in relation to these issues or to the need to adopt responsible business practices in accordance with international instruments.

Table 6.1. SADC thematic policy frameworks related to RBC

|

SADC framework |

Launch date |

Content |

|---|---|---|

|

Human rights |

||

|

Charter of Fundamental Social Rights in SADC |

2003 |

Charter aimed at promoting and protecting basic human rights, freedom of association and collective bargaining, gender equality, children’s rights, protection of health, safety, and environment. |

|

SADC Protocol on Gender and Development |

2008; revised in 2016 |

Protocol encouraging Member States to develop and implement legislation and policy to address gender issues. |

|

SADC Regional Strategy and Framework of Action for Addressing Gender-Based Violence (2018‑30) |

2018 |

Framework to prevent, combat, and end all forms of gender-based violence. |

|

SADC Declaration on Gender and Development |

1997 |

Declaration to foster gender equality in the region by establishing policy and institutional frameworks within Member States, creating advisory systems to monitor gender-related issues, and establishing a Gender Unit in the SADC Secretariat. |

|

Labour rights |

||

|

SADC Code of Conduct on Child Labour |

2000, revised in 2022 |

Regional code of conduct to combat child labour. |

|

SADC Protocol on Employment and Labour |

2014 |

Protocol on labour rights including freedom of association and collective bargaining, equal treatment, working conditions, occupational health and safety, health care, children’s rights. |

|

Environment |

||

|

SADC Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan 2020-2030 |

2021 |

Regional plan to address and mitigate the environmental impacts of climate change. |

|

SADC Forestry Strategy (2020‑30) |

2020 |

Strategic framework for national and regional co‑operation to address challenges linked to the management of forest resources in the SADC region |

|

SADC Green Economy Strategy and Action Plan for Sustainable Development |

2015 |

Policy framework, strategy, and action plan to guide the integration of resilient economic development, environmental sustainability, and poverty eradication for green economy. |

|

SADC Regional Biodiversity Strategy |

2008 |

Strategy and guidelines to implement provisions of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and to foster consensus on key biodiversity issues and co‑operation between Member States. |

|

Anti-Corruption |

||

|

SADC Protocol against Corruption |

2001; amended in 2016 |

Protocol to promote co‑operation amongst Member States to develop mechanisms that prevent, detect, punish, and eradicate corruption in the public and private sector. |

|

Strategic Anti-Corruption Action Plan for 2018‑22 |

2018; currently updated for 2023‑27 |

Framework for operationalisation of the SADC Protocol against Corruption |

|

Consumer Protection |

||

|

SADC Declaration on Competition and Consumer Policies |

2009 |

Protocol for Member States aimed at fostering competition, prevent unfair business practices, and establish a mechanism for consumer protection. |

Regarding human and labour rights, certain overarching policies and commitments are of relevance to the promotion of an enabling policy environment for RBC. The Charter of Fundamental Social Rights in SADC and the SADC Protocol on Employment and Labour recognise basic human rights and labour rights building on the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Moreover, the 2016 Protocol on Gender and Development, among others, demands Member States to ensure equal access to employment and equal pay for work of equal value for all women and men in all sectors. The SADC Code of Conduct on Child Labour sets out the aim to create public-private and multistakeholder partnerships to encourage and promote responsible business and to prevent child labour in Article 6.8 (SADC, 2022[27]). At this stage, it is unclear from publicly available sources where the implementation process of this Code of Conduct stands.

With respect to the environment, SADC has several frameworks in place addressing various issues such as climate change and biodiversity protection, which mention the role of the private sector. The revised SADC Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (2020‑30) sets out objectives with respect to sustainable business conduct, for instance, identifying opportunities to reduce emissions, to improve waste management and to adopt sustainable techniques in the energy, agricultural and other key sectors. The SADC Forestry Strategy 2020‑30 sets out the objective to put into place regional mechanisms to enable protection, sustainable management, and restoration of all forest types. It also identifies the conversion of forest land to agricultural areas, grazing land, infrastructure, and other land use as an ongoing challenge across SADC, and highlights the important role of the private sector and local communities in forest management (SADC, 2020[28]).

In relation to anti-corruption, the 2001 SADC Protocol Against Corruption aims to end all forms of corruption in both the public and private sector in all Member States. The Protocol refers among others to the importance of regional co‑operation, participation of civil society, adequate access to information, and transparency in public procurement to prevent corruption (SADC, 2001[29]). Moreover, SADC is currently updating its Anti-Corruption Strategic Action Plan for the period 2023‑27, which provides the framework for the operationalisation of the Protocol (SADC, 2022[30]).

Sectoral frameworks and initiatives at SADC level

In addition to thematic policies and frameworks relating to areas covered by the OECD MNE Guidelines, SADC has developed sector-specific policies which link to RBC, notably for the extractive and agriculture industries. Both sectors are key for the socio‑economic development in SADC, yet also prone to human rights, labour rights, environment, anti-corruption, and conflict risks.

SADC has developed several policies and frameworks in the mining sector, which relate to responsible business practices. The SADC Protocol on Mining entered into force in 2000 and mandates Member States to harmonise their policies and procedures for mineral extraction. Its goal is to promote the mineral industry in Southern Africa and encourage private sector developments, including small-scale projects that empower disadvantaged groups in the mining sector. As outlined in Articles 8 and 9, Member States agreed to promote workers’ health and safety, as well as environmental protection standards in line with internationally recognised standards. To facilitate these goals, the Protocol on Mining calls for the establishment of an organisational structure consisting of a Committee of Mining Ministers, a Technical Committee of Officials, and a Mining Co‑ordinating Unit to oversee mining operations and ensure that applicable standards are upheld (SADC, 1997[31]).

In the agriculture sector, SADC has adopted the Regional Agriculture Policy in 2013 which is operationalised through the Regional Agricultural Investment Plan (2017‑22) and the Food and Nutrition Security Strategy (2015‑25). The Policy sets out the aim to improve sustainable agricultural production including through private sector engagement and investment in agricultural value chains (SADC, 2013[32]). The strategy also foresees to reduce vulnerabilities and risks related to RBC in the sector notably climate change, gender inequality, health, migration, and food insecurity (SADC, 2014[33]). At present, there is limited information available to the public regarding the implementation and monitoring process of this strategy.

Member States’ national frameworks and initiatives relating to RBC

SADC governments have developed various policies and initiatives at the national level that address RBC issues and, in few cases, have started to integrate RBC instruments into their legal frameworks. However, comprehensive domestic regulation and specific action plans on RBC, for example, setting out due diligence expectations are not yet developed and adopted in the region.

SADC Member States have adhered to several international instruments in areas covered by the OECD MNE Guidelines, such as human rights, labour rights, the environment and anti-corruption. Table 6.2 illustrates that all SADC Member States have ratified key climate and anti-corruption related agreements such as the Paris Agreement, as well as the UN Convention against Corruption. However, gaps remain for the human and labour rights instruments, since several SADC countries have not adhered to all Core UN Conventions on Human Rights nor to all Fundamental ILO Conventions.

In addition to the adherence to international frameworks relevant for RBC, some Member States in SADC have started to develop national strategies to explicitly promote RBC. National Action Plans (NAPs) on Responsible Business Conduct or Business and Human Rights can provide an important overarching policy framework for concrete state action for RBC, developed through inclusive stakeholder engagement. NAPs have been adopted by 30 countries around the world including Kenya and Uganda in Africa (DIHR, 2023[34]). They are policy documents setting out a common and evolving national RBC policy framework to protect against adverse human rights impacts by businesses (UNWGBHR, 2016[35]). In SADC, the development of NAPs has been limited so far. No Member State has yet published a NAP up to this point. Processes to develop a NAP are currently ongoing in four out of 16 countries: Mozambique, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zambia.

Table 6.2. Ratification of key international frameworks and development of National Action Plans

|

Core UN Conventions on Human Rights |

Fundamental ILO Conventions |

Kyoto Protocol |

Paris Agreement |

Convention on Biological Diversity |

UN Convention against Corruption |

Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative |

NAP on RBC / BHR |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AGO |

7/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

BWA |

6/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

COM |

5/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

COD |

7/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

SWZ |

7/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

LSO |

9/9 |

9/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

MDG |

8/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

MWI |

9/9 |

10/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

MUS |

7/9 |

10/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

MOZ |

7/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

|

NAM |

7/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

SYC |

9/9 |

9/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

ZAF |

7/9 |

9/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

▣ |

|

TZA |

6/9 |

8/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

|

ZMB |

8/9 |

10/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

▣ |

|

ZWE |

6/9 |

9/10 |

■ |

■ |

■ |

■ |

□ |

□ |

Note: ■ = Ratified / member / developed; ▣ = Partially ratified/ under development; □ = Not ratified / not member / not developed.

NAP development processes have been driven mostly by civil society and non-state initiatives in the region. In Mozambique, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce expressed interest in leading the NAP process, however, it was initiated by the Mozambique Bar Association’s Human Rights Commission in 2017. In South Africa, the initiative to develop a NAP is led by civil society and academia. The Centre for Human Rights at the University of Pretoria published a “Shadow” National Baseline Assessment of the Current Implementation of Business and Human Rights Frameworks in 2016. In Tanzania, the Human Rights Action Plan (2013‑17) of the government tasked the Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance to develop a National Baseline Study on Business and Human Rights to support the NAP development. In Zambia, similar efforts have been led by the national human rights institution, the Zambia Human Rights Commission (ZHRC). The ZHRC published a National Baseline Assessment on Business and Human Rights in 2016 as well as a supplement to this assessment in the mining and agriculture sectors in 2020. As of March 2023, it has been reported that both the Tanzanian and Zambian Government has made a commitment to develop a NAP according to the most recent information available from the Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR, 2023[34]).

Aside from the limited number of NAPs, SADC Member States have put forward various national frameworks relating to RBC issues. Most Member States have established legislation with respect to labour and environmental issues in the mining and agricultural sectors. For instance, national mining codes in SADC generally include overall provisions and required authorisations with respect to the protection of the environment. Moreover, SADC governments have legislations in place addressing forced and child labour in their countries and set up obligations for companies to conduct environmental impact assessments prior to investment projects. Some governments have set up initiatives with philanthropic purposes rather than relating directly to business impacts. For instance, Mauritius created a CSR fund based on a certain percentage of a business taxable income, which are used for programmes relating to the environment and sustainable development (MRA, 2021[36]). An overview of policies relating to RBC across SADC countries is listed in Annex 6.A.

Several governments have already started to promote the observance of the OECD RBC and due diligence instruments. Notably, the DRC has integrated the OECD Minerals Guidance into its legal framework covering tin, tungsten, tantalum, gold, copper, and cobalt via Ministerial Decree in 2011 (Government of DRC, 2011[37]). Moreover, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, which includes among others Angola, DRC, Tanzania, and Zambia has set up a regional certification mechanism for minerals, which requires traders to undertake due diligence aligned with OECD instruments (OECD, 2011[38]). In 2022, Mauritius submitted an official request to adhere to the OECD MNE Guidelines and started the adherence process in 2023, which would make it the first adherent country not only in SADC, but also Sub-Saharan Africa.

Several SADC Member States have also signed trade and investment agreements or partnerships, which include provisions relevant to promote and enable RBC. As the nature of trade and investment agreements evolves, they include increasingly provisions on the responsibility of business with respect to human rights, the environment and sustainable development, which has been driven notably by the EU trade and investment policies. The Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between the EU and the SADC EPA States (Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, and South Africa) concluded in 2016, includes a chapter on Trade and Sustainable Development. This chapter refers among others to the commitment to multilateral environmental and labour standards such as the ILO conventions but does not refer explicitly to RBC (EU, 2016[39]). In addition, the EU and Angola concluded in 2022 the first-ever Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement. The agreement explicitly highlights the need to promote RBC and implement risk-based due diligence in Article 5.7 with a view to contribute to sustainable development. In this context, the agreement also supports the dissemination of the main international RBC instruments from ILO, OECD, and OHCHR (EC, 2022[40]).

SADC stakeholders’ awareness of RBC

In addition to government policies in SADC, business and civil society are engaged in a range of RBC-related initiatives. However, many of these actions are still in their early stages and stakeholder awareness of RBC standards and due diligence approaches remains limited in the region.

Businesses in SADC are increasingly aware of the importance of RBC and engage in responsible business practices. UN Global Compact regional networks exist in Angola, Botswana, DRC, Mauritius and Indian Ocean Region (Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles), South Africa and Tanzania. A total of 207 businesses participates in these networks, which work towards sustainable development in the areas of human rights, labour, environment, and anti-corruption (UNGC, 2021[41]). Moreover, national initiatives in SADC promote sustainable and responsible business practices such as the National Business Initiative in South Africa. The initiative is a voluntary coalition of over 100 South African and multinational member companies. It provides a platform for businesses to share best practices, collaborate, and develop solutions to social, economic, and environmental challenges (NBI, 2022[42]). Moreover, companies in minerals supply chains, for example in DRC, have been involved in various initiatives to implement due diligence processes over the last years. However, the advancement of these implementation programmes has been challenging so far (OECD, 2015[43]; OECD, 2019[44]).

Several civil society organisations in SADC are also leading initiatives to promote RBC. For example, the Legal and Human Rights Centre in Tanzania (LHRC) has set up the programme “Human Rights and Business”, which seeks to promote responsible business among government and business in line with international RBC instruments including the UNGPs and the OECD MNE Guidelines (LHRC, 2022[45]). In Zimbabwe, the “Publish What You Pay” Coalition is a group of civil society organisations aiming to improve business transparency and accountability in the minerals sector (PWYP, n.d.[46]). In Mozambique, the Fórum da Sociedade Civil para os Direitos da Criança promotes children’s rights and aims to reduce child labour via advocacy, capacity-building and partnerships with stakeholders including the private sector (ROSC, 2023[47]).

Several multi-stakeholder initiatives have started to reference and promote the implementation of the OECD due diligence guidance in SADC. For instance, in the context of cobalt mining in DRC, the Responsible Cobalt Initiative aims to address the risks associated with the cobalt supply chain through collaboration between business, the Government of DRC, civil society, and affected local communities. The initiative was founded by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce for Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers and Exporters and the OECD. It seeks to have downstream and upstream companies align their supply chain policies with the OECD Minerals Guidance (RCI, 2016[48]).

Although stakeholders in Southern Africa are becoming more aware of the importance of responsible business practices, gaps remain to collaborate across stakeholders and to build capacity of businesses to implement RBC practices. SADC governments can provide this support and guidance by creating a policy and regulatory environment for RBC and strengthening companies’ capacity and ability to conduct due diligence. This is key to build more sustainable value chains, attract high-quality investments, and move towards sustainable development. Co‑operation among governments, businesses, and civil society will be necessary to achieve this.

References

[14] Agyemang, et al (2020), Country-level corporate governance and foreign direct investment in Africa, https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-07-2018-0259.

[23] AUC/OECD (2022), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2022: Regional Value Chains for a Sustainable Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris/African Union Commission, Addis Ababa, https://doi.org/10.1787/2e3b97fd-en.

[15] Chamisa, M. (2020), Does Corruption Affect Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Inflows in SADC Countries?, https://doi.org/10.30871/jaat.v5i2.1873.

[34] DIHR (2023), National Action Plans on Business and Human Rights, https://globalnaps.org/.

[20] EC (2022), Corporate sustainability due diligence, European Commission, https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/doing-business-eu/corporate-sustainability-due-diligence_en.

[40] EC (2022), EU-Angola Sustainable Investment Facilitation Agreement, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_6136.

[39] EU (2016), Economic Partnership Agreement between the European Union and its Member States, of the one part, and the SADC EPA States, of the other part, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22016A0916(01)&from=EN.

[37] Government of DRC (2011), Note Circulaire numero 002/CAB.MIN/MINES/01/2011, https://cdn.globalwitness.org/archive/files/library/note_circulaire_oecdguidelines_06092011.pdf.

[4] ILO (2020), The Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy in Africa, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_792078.pdf.

[8] ILO (2019), Child labour in mining and global supply chains, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---ilo-manila/documents/publication/wcms_720743.pdf.

[45] LHRC (2022), Human Rights & Business, https://humanrights.or.tz/en/post/resources-center/HRBReport21_22.

[36] MRA (2021), Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Guide, Mauritius Revenue Authority, https://www.mra.mu/download/CSRGuide.pdf.

[42] NBI (2022), Introducing the National Business Initiative, https://www.nbi.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/NBI-Brochure.pdf.

[11] NEPAD (2023), TB in the Mining Sector in Southern Africa (TIMS), https://www.nepad.org/content/tb-mining-sector-southern-africa-tims.

[7] OEC (2023), SADC, https://oec.world/en/profile/international_organization/sadc.

[19] OECD (2023), OECD Due Diligence Policy Hub, http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/due-diligence-policy-hub.htm.

[17] OECD (2023), OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct, https://doi.org/10.1787/81f92357-en.

[21] OECD (2023), OECD Recommendation on the Role of Government in promoting Responsible Business Conduct, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0486.

[1] OECD (2021), Survey Results on Responsible Business Conduct in Latin America, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/oecd-business-survey-results-on-responsible-business-conduct-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean.pdf.

[44] OECD (2019), Interconnected supply chains: a comprehensive look at due diligence challenges and opportunities sourcing cobalt and copper from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Interconnected-supply-chains-a-comprehensive-look-at-due-diligence-challenges-and-opportunities-sourcing-cobalt-and-copper-from-the-DRC.pdf.

[18] OECD (2018), OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

[43] OECD (2015), Mineral Supply Chains and Conflict Links in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Mineral-Supply-Chains-DRC-Due-Diligence-Report.pdf.

[38] OECD (2011), The Mineral Certification Scheme of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, https://www.oecd.org/investment/mne/49111368.pdf.

[13] Punthakey, J. (2020), “Foreign direct investment and trade in agro-food global value chains”, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 142, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/993f0fdc-en.

[46] PWYP (n.d.), Zimbabwe, https://www.pwyp.org/pwyp_members/zimbabwe/.

[48] RCI (2016), Responsible Cobalt Initiative, https://respect.international/responsible-cobalt-initiative-rci/.

[47] ROSC (2023), Áreas de Actuação, https://www.rosc.org.mz/index.php/areas-de-actuacao.

[27] SADC (2022), CODE OF CONDUCT ON CHILD LABOUR (REVISED), https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2022-10/EN-%20Revised_SADC_Code_on_Child_Labour_30%20March%202022.pdf.

[30] SADC (2022), Heads of SADC Anti-Corruption Agencies resolve to strengthen fight against graft, https://www.sadc.int/latest-news/heads-sadc-anti-corruption-agencies-resolve-strengthen-fight-against-graft.

[9] SADC (2020), Information Brief, Agriculture in the SADC Region Under Climate Change, https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/110100/SADC%20Information%20Brief_FINAL.pdf.

[6] SADC (2020), Mining, https://www.sadc.int/pillars/mining.

[28] SADC (2020), SADC Forestry Strategy 2020-2030, https://amis-fis.jp/about-sadc/pdf/Draft_SADC_Forestry_Strategy.pdf.

[3] SADC (2020), SADC Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan, https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2021-08/RISDP_2020-2030.pdf.

[26] SADC (2020), SADC Vision 2050, https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2021-08/SADC_Vision_2050..pdf.

[24] SADC (2017), SADC Model Bilateral Investment Treaty Template, https://www.civic264.org.na/images/pdf/SADC_BIT_template_final.pdf.

[33] SADC (2014), Food and Nutrition Security Strategy 2015-2025, https://www.resakss.org/sites/default/files/SADC%202014%20Food%20and%20Nutrition%20Security%20Strategy%202015%20-%202025.pdf.

[32] SADC (2013), Regional Agricultural Policy, https://www.inter-reseaux.org/wp-content/uploads/Regional_Agricultural_Policy_SADC.pdf.

[22] SADC (2006), Protocol on Finance and Investment, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements/treaty-files/2730/download.

[29] SADC (2001), SADC Protocol against corruption, https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2021-11/Protocol_Against_Corruption2001.pdf.

[31] SADC (1997), Protocol on Mining in SADC, https://www.sadc.int/sites/default/files/2021-08/Protocol_on_Mining..pdf.

[5] SAIIA (2021), Optimising Agricultural Value Chains in Southern Africa After COVID-19, https://saiia.org.za/research/optimising-agricultural-value-chains-in-southern-africa-after-covid-19/.

[16] UN; OECD; EU; ILO (2019), Responsible business: key messages from international instruments, United Nations, OECD, European Union, International Labour Organization, Social Justice Decent Work, https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/Brochure-responsible-business-key-messages-from-international-instruments.pdf.

[25] UNCTAD (2023), International Investment Agreements Navigator, https://investmentpolicy.unctad.org/international-investment-agreements.

[12] UNECA/ FES (2022), The Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) in Africa – A Human Rights Perspective, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Globalization/TheCFTA_A_HR_ImpactAssessment.pdf.

[41] UNGC (2021), Un Global Compact Africa Strategy 2021-2023, https://ungc-communications-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/docs/publications/UNGC_Mobilising%20Business%20in%20Africa_2021_2023.pdf.

[35] UNWGBHR (2016), Guidance on National Action Plans on Business and Human Rights, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Business/UNWG_NAPGuidance.pdf.

[2] WBA (2021), COVID-19 and Human Rights, World Benchmarking Alliance, https://assets.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/app/uploads/2021/02/CHBR-Covid-Study_110221_FINAL.pdf.

[10] WFP (2021), Climate Change in Southern Africa, https://executiveboard.wfp.org/document_download/WFP-0000129015.

Annex 6.A. National frameworks related to RBC

|

Specific Frameworks/Policies Related to RBC |

|

|---|---|

|

Angola |

|

|

Botswana |

|

|

Comoros |

|

|

DRC |

|

|

Eswatini |

|

|

Lesotho |

|

|

Madagascar |

|

|

Malawi |

|

|

Mauritius |

|

|

Mozambique |

|

|

Namibia |

|

|

Seychelles |

|

|

South Africa |

|

|

Tanzania |

|

|

Zambia |

|

|

Zimbabwe |

|