This “outcomes” chapter illustrates the existing gender inequalities in Estonia and discusses their possible causes and consequences. More precisely, it considers how key labour market outcomes have evolved over the longer term and how they have been affected by the ongoing COVID‑19 pandemic in the shorter term. In some regards, men and women enjoy more equal conditions on the Estonian labour market than on average in their OECD counterparts. For instance, participation in the labour market is high, and women are working similar number of hours as men are. However, there are some key challenges where it is not clear that the labour market will correct at a similar pace as in other countries, which means that Estonia risks falling behind. These areas include gaps in wage and education, as well as occupational and sectoral segregation. These differences in gender outcomes are compounded by existing ethnic inequalities. To correct outcomes in these areas, Estonia needs decisive policy action clearly informed by a gender perspective. The analysis is based on data from cross-country databases and, where needed, complemented by in-depth inquiries into Estonian administrative and survey data.

The Economic Case for More Gender Equality in Estonia

2. The labour market situation for men and women in Estonia

Abstract

2.1. Introduction and main findings

Estonia has made great strides in economic development since it regained independence in 1991. However economic and labour market gender differentials remain persistent. In recent decades, there has been a sectoral transformation away from family-based agriculture and manufacturing and toward a market style economy with a large service sector. Women have gained from this transition and are now experiencing increased returns to education (Meriküll and Tverdostup, 2021[1]). However, this evolution has not equalised conditions on the labour market. Despite similar overall participation rates, Estonia has one of the larger gender wage gaps in the OECD. This will in large part be caused by segregation of men into mathematics-focused and high-paid sectors and women into social and lower-paid sectors, in combination with a hard glass ceiling and prevailing traditional gender norms.

Women still shoulder the majority of unpaid work in the home in Estonia, and pressures are mounting. An ageing population leads to an increasing number of people in need of care, and the current health care system is already overburdened and faces budgetary pressures. Given the still prevailing belief that a woman’s most important role is to care for her family, the pressure is building on working-age women to shoulder responsibility of this increasing unpaid work. Care burdens increased with the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic, which caused some women to accept shorter hours or leave the labour market. There are pertinent questions about how to deal with care and other domestic work challenges so women can engage in paid work on parity with men.

There is a lot to gain from more economic equality between men and women and policies to address gender inequalities are part of the broader national effort to tackle income inequality and poverty. Since many women are low-paid, an increase in the minimum wage, support for elderly poor, and a decline in overall income inequality will disproportionally benefit women (Meriküll and Tverdostup, 2021[1]). Opening up more opportunities to women will also play an important part in supporting overall increases in economic growth and productivity (OECD, 2021[2]). Estonia is in a good position to design and support successful policies: central government debt is the lowest among OECD countries and with the (planned) allocation from the EU recovery fund, there appears to be more fiscal space to invest in policies for gender equality (OECD, 2021[3]; Eamets, 2012[4]; OECD, 2021[5]).

Main findings

The female employment rate (72%) was higher in Estonia than across the OECD (61%) in 2019, and the gender gap in favour to men is relatively small at 7 percentage points – half the OECD average. At 87%, Estonia stands out among OECD countries with its high proportion of employed women who work full-time. During the COVID‑19 pandemic women’s employment took the initial hit relative to men’s, but the gender employment gap shrunk in the second half of 2020.

Estonia’s gender wage gap is large. Despite a recent decline, it remains at 17%, well above the OECD average of 12%. This gender wage gap between men and women is wider among minority nationalities.

The role of women as unpaid workers in the home is one important reason why gender inequalities on the labour market are so persistent. The difference between men’s and women’s hours spent doing work in the home is smaller in Estonia (1.5) than across the OECD (2.1), but not as small as in the least unequal country, Sweden (0.8). 36% of women reported that they felt overburdened by housework before the pandemic (compared to 16% of men).

The pressure of unpaid house work – falling most heavily on women – has increased during the pandemic, raising immediate questions about women’s ability to engage in the labour market on parity with men, particularly during early and mid-career when wage increases and promotions are common. Looking ahead, increased longevity, poor (male) health, low health care funding look set to increase the demands on women to do unpaid work, unless there is a change in attitudes and policy.

Another important reason for different outcomes is that women tend to work in places with lower financial rewards. Young women are underrepresented as graduates in the generally well-paid jobs that follow studies in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Just 17% of information and communication technology graduates were women in 2019. In contrast, only 8% of graduates in education studies are men. Similarly, men make up just 14% of jobs in health and welfare sectors. There has been very little change in any of these proportions over time.

Vertical segregation is another source of labour market inequality, and the so-called glass ceiling is thick in Estonia: with 9% it had the fifth smallest share of women on boards among OECD countries in 2019. One reason for this could be that it is not widely believed that business would benefit from more female leaders: while a majority of women (56%) agree. only 36% of men agree that businesses would benefit.

Inequalities between Estonians and non-Estonians persist today and compound with gender to lead to greater disadvantage in labour market outcomes for non-Estonian women.

On average, people in Estonia have traditional views regarding gender equality relative to OECD averages, but particularly compared to leading countries such as Sweden. Seventy eight percent of Estonians (compared with 71% across the OECD) believe that women are more likely than men to make decisions based on their emotions. Beliefs about how women make decisions are core to how women are perceived in their education and careers – and particularly with regard to how much weight one can assign to a woman’s professional opinions.

2.2. Gender gaps in labour supply and earnings

2.2.1. Women are only slightly less likely than men to be in paid work

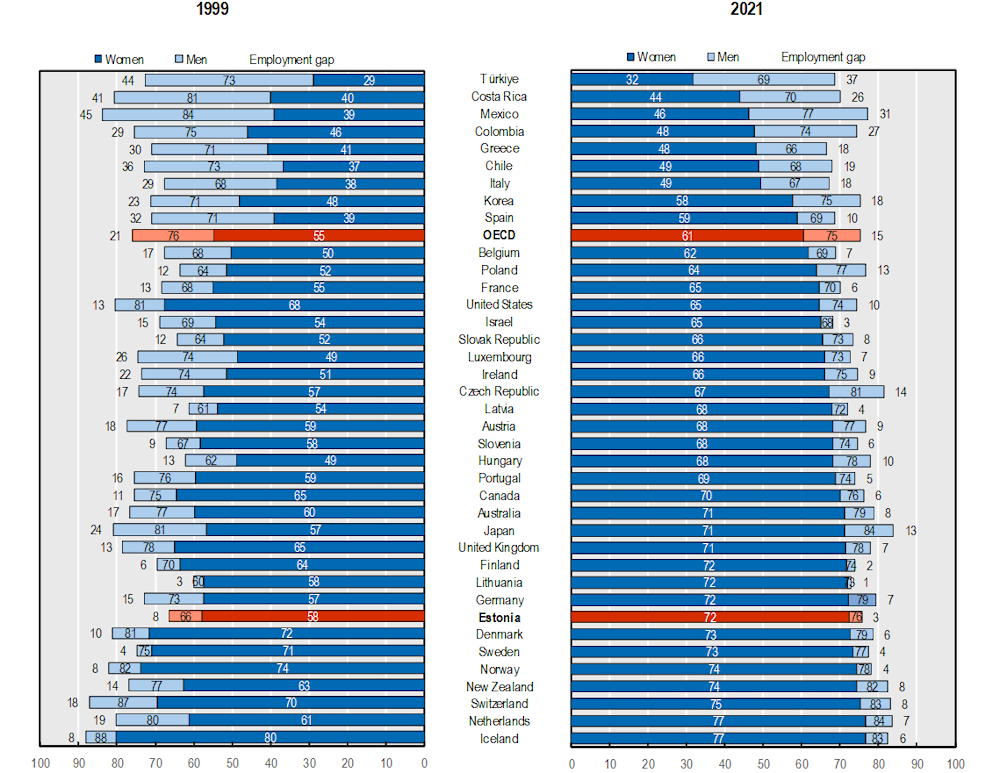

This section exposes existing complexities and contradictions for women in the Estonian labour market. A good starting place is overall participation rates in paid work. Women in Estonia are relatively likely to be employed compared to women OECD-wide During the COVID‑19 crisis in 2021, data shows that 72% of women were working in the labour market in Estonia, compared to the considerably lower OECD average rate of 61%. The employment rate in Estonia was similar to that in the United Kingdom and Denmark, but lower than that in countries like Iceland and Switzerland (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Gender employment gaps in Estonia are small but persistent

Note: Persons in employment divided by the population. Data refer to the population aged 15‑64. Instead of 1999, data refer to 2000 for Latvia, Lithuania and Slovenia and to 2001 for Colombia.

Source: OECD Employment Database.

The difference between male and female employment rates – 3 percentage points – is small relative to other OECD countries where the average is 15 percentage points. This gender gap in Estonia was similar to its neighbouring countries: in 2021 the employment gaps were as low as 1 and 4 percentage points Lithuania and Latvia, respectively (Figure 2.1). Puur (2000[6]) suggests that the relatively small gender gap in employment rates is due to Estonia never fully developing a breadwinner-homemaker system (where men engage in paid work while women take unpaid responsibility for the home) as those observed in western Europe and the United States. In other words, women have traditionally participated in paid work to a similar degree as men, so it is unsurprising that gender employment gaps are small.

Since 1999,1 the female participation rate in Estonia increased by 14 percentage points to 72% in 2021 and male participation grew by 9 percentage points to 76% over the same time period. Employment increased faster in Estonia than across the OECD on average where female employment increased by 6 percentage points and male employment rate fell by 1 percentage point (Figure 2.1). The rise of the service economy in Estonia benefited women’s employment and wage opportunities in the years before the COVID‑19 pandemic. Growing activity in this sector in recent decades accounts for an important share of the observed trends in the increasing number of hours that women work and their pay relative to men (Ngai and Petrongolo, 2017[7]; Blau and Kahn, 2017[8]).

In addition, net migration from Estonia between 2000 and 2014 can have played some part in tightening labour markets at home (Eurostat, 2022[9]). Between 2000 and 2014, Estonia experienced negative net migration, which means that more people tended to leave the country than arrive to it. After 2014 the tide turned and from 2015 and onwards, Estonia has had positive net migration. The share of women migrating out of Estonia was slightly lower after 2014 than before, but has remained stable in recent years (Statistics Estonia, 2022[10]). Overall, 2.8 per 1 000 people arrived to Estonia in 2020, which is similar to the figure in Norway (2.8) and Germany (2.9). The figure is lower than that in neighbouring Lithuania (7.2). However, Latvia has not yet managed to turn the trend of negative net migration with 1.7 per 1 000 people overall leaving the country in 2020 (see Annex Table 2.A.1).

The war of aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine has led to an inflow of a great number of refugees from February/March 2022 and onwards. By 5 September 2022, Estonia has received 54 197 Ukrainian war refugees. This is around 4% of Estonia’s total population. It is as yet unclear how many Ukrainian refugees will end up staying in Estonia, for how long, and what the socio‑economic effects of this inflow might be.

2.2.2. Women bore the initial shock of the COVID‑19 pandemic, but female employment rates have already surpassed pre‑crisis levels

The COVID‑19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis hit Estonia with its export-oriented economy hard in early 2020, but since then the economy has started to recover. There was an immediate hit to the labour market in the first half of 2020 but due to some recovery in the second half, the employment rate only fell by just under 2 percentage points between 2019 and 2020, to 74%. This fall was of similar magnitude to the OECD-wide average (nearly 3 percentage points) over the same time period. By the end of 2021, the employment rate had reached 75%, just 1 percentage point below pre‑COVID levels.

The employment crisis in 2020 hit women, young people and those with lower levels of education harder than their male, prime‑aged (25‑54) and well-educated counterparts. In large part this is because they tend to be overrepresented in sectors that were hardest hit by restrictions on social interaction, including leisure, hospitality and non-food retail (OECD, 2020[11]; Gustafsson and McCurdy, 2020[12]). In addition, the additional care needs that have arisen partly due to school closures have fallen heavily on mothers (OECD, 2021[3]). Many women therefore have been forced to take on fewer hours, assume part-time work or leave the workforce entirely even though they still had an active job (see Section 2.3.1 for more on unpaid work during the pandemic).

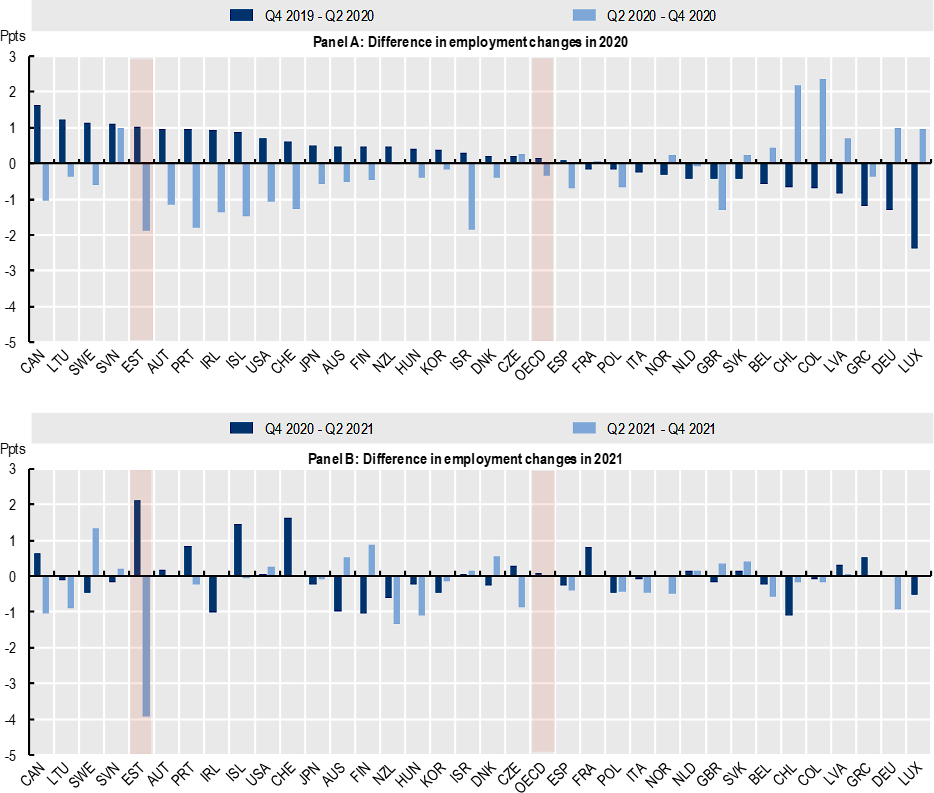

Figure 2.2 illustrates the initial shock on female employment participation. The immediate negative changes to female employment rate resulted in increases in the gender employment gap. The gender differences in these shocks were among the largest across the OECD in Estonia (Figure 2.2 Panel A, dark blue bars). As would be expected, women also lost more hours of work on average than men in the beginning of the crisis: women worked 13% fewer hours in the second quarter compared to the year before, and men worked 11% fewer hours. These declines in Estonia are slightly smaller than the average falls in hours worked in the OECD: 16% for women and 15% for men (OECD, 2021[13]).

Longer-term effects on employment differed from the immediate hit, however. The employment gap declined immediately as the economy started its recovery in the second half of 2020 and women came back to work (Figure 2.2 Panel A, light blue bars). At the same time, men experienced a slightly greater negative impact on their working hours (down 4% year-on-year) in the fourth quarter than women did (down 3% year-on-year) (OECD, 2021[13]). As a new wave hit in spring 2021 and new emergency measures were put in place, employment rates decreased for both men and women – with women again taking the bigger hit – in the first half of 2021 (Figure 2.2 Panel B, dark blue bars). Female employment rates subsequently recovered and the employment gap shrank. By Q4 in 2021, female employment had surpassed pre‑COVID levels (at 74.5%), and the gender employment gap was smaller than the pre‑COVID gap (Figure 2.2 Panel B, light blue bars).

Figure 2.2. The gender employment gap widened in the two initial months of COVID‑19

Note: The gap is calculated as the difference in employment rate changes between men and women aged 15‑64 years old. There have been some changes introduced to the EU Labour Force Survey from 2021 onwards. These include a harmonisation of classifying the absences from work, especially for people on parental leave and seasonal workers. See more detail on this here: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_Labour_Force_Survey_-_new_methodology_from_2021_onwards#Main_changes_introduced_in_2021.

Source: OECD Short-Term Labour Market Statistics database.

2.2.3. Women typically work full-time in Estonia, unlike in other high-employment countries

It is not just whether people are in employment or not that matters for the pay packet, but the number of hours worked can be just as important. In addition, working fewer hours per week or on a part-time contract is associated with lower wage growth, slower career progression and higher risk of job loss in a downturn. The conditions in Estonia are conducive for full-time work for both men and women.

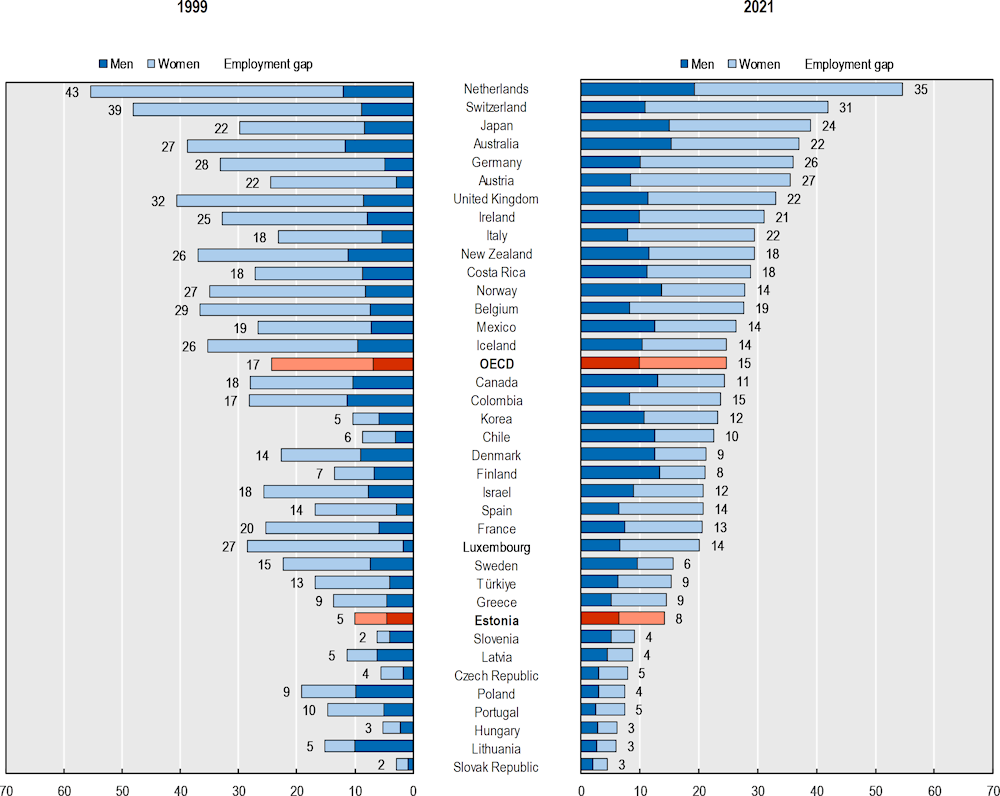

Estonia distinguishes itself from other high-employment countries: the relatively high female employment rate in Estonia does not rely on a high share of women working on a part-time basis, as in Switzerland, the Netherlands or Germany. Instead, the incidence of employed women working part-time is considerably lower than the OECD average (14% compared to 25%), but slightly higher than among its Baltic neighbours Lithuania (6%) and Latvia (9%) (Figure 2.3). Part-time work had increased slightly for both female and male workers in Estonia between 2000 and 2021: by 3 percentage points for women and by 1 percentage point for men.

Figure 2.3. More women work full-time in Estonia than across the OECD

Note: Instead of 2021, data refer to 2019 for Australia. Instead of 1999, data refer to 2000 for Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia, 2001 for Australia and Colombia and 2010 for Costa Rica. Data refer to the incidence of part-time work in total employment. Part-time employment is based on a common 30‑usual-hour cut-off in the main job.

Source: OECD Employment Database.

The high participation in full-time work among women in Estonia means that the gap between the proportion of male and female workers on part-time contracts is relatively low: 7 percentage points in Estonia compared to 15 percentage points across the OECD (Figure 2.3). Correspondingly, the average working week is similar for men and women in Estonia: the mean hours per week is 36.7 for women and 39.1 hours for men. Compared to the OECD averages, women in Estonia tend to work longer hours than across the OECD, while men work shorter hours in Estonia compared to the OECD average. Based on participation in the labour market and the number or hours worked per week, women in Estonia seem to be in a good position to enjoy relatively equal labour market outcomes to men. However, the following sections show that women face significant disadvantage on other measures of gender equality.

2.2.4. The gender wage gap is relatively large in Estonia

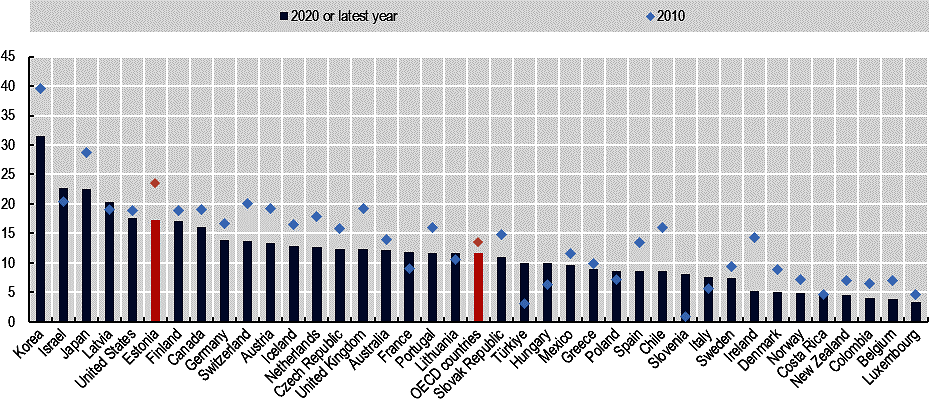

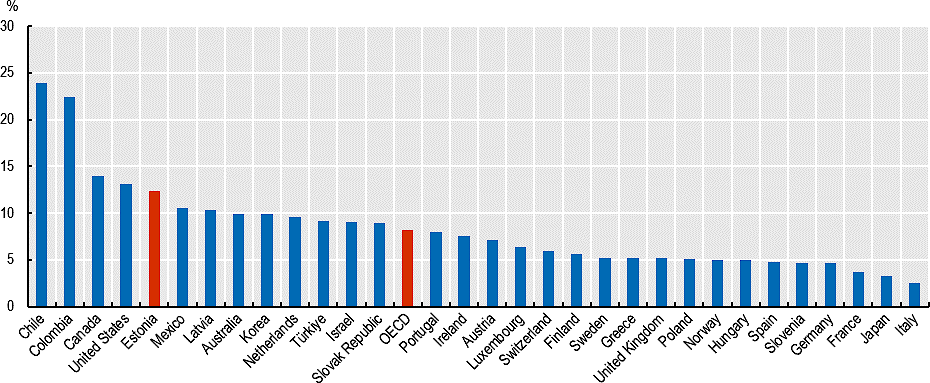

Even though women and men in Estonia are similarly likely to be in a job and tend to work a similar number of hours in that job, women receive significantly less money than men each month. Figure 2.4 shows the gender gap for median monthly wages among full-time employees. The most recent data shows that at median earnings, the gender wage gap was 17% in Estonia, compared with 12% on average across the OECD.

It is encouraging that the gender wage gap has shrunk faster in Estonia than in the OECD since 2010 (6 percentage points compared to 2 percentage points). There has been strong wage growth since the financial crisis: between 2008 and 2019, average real wages grew by 33%, placing Estonia among the countries with the highest wage increase in the OECD (OECD, 2021[14]). However, it remains to be seen how Estonia’s current high inflation will affect real wage growth in coming years (Eurostat, 2022[15]). This could be important as Estonia still has some way to go before the wage gap has shrunk to the levels seen in leading countries like Belgium or Norway (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. The gender wage gap is large but decreasing

Notes: Instead of 2010, data refers to 2011 for Chile and Costa Rica. Instead of 2020, data refers to 2019 for Belgium, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland and Italy; 2018 for Costa Rica, Estonia, France, Iceland, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain and Türkiye; 2014 for Luxembourg.

Source: OECD (2022), Gender wage gap indicator, available at www.oecd.org/gender/data/employment.

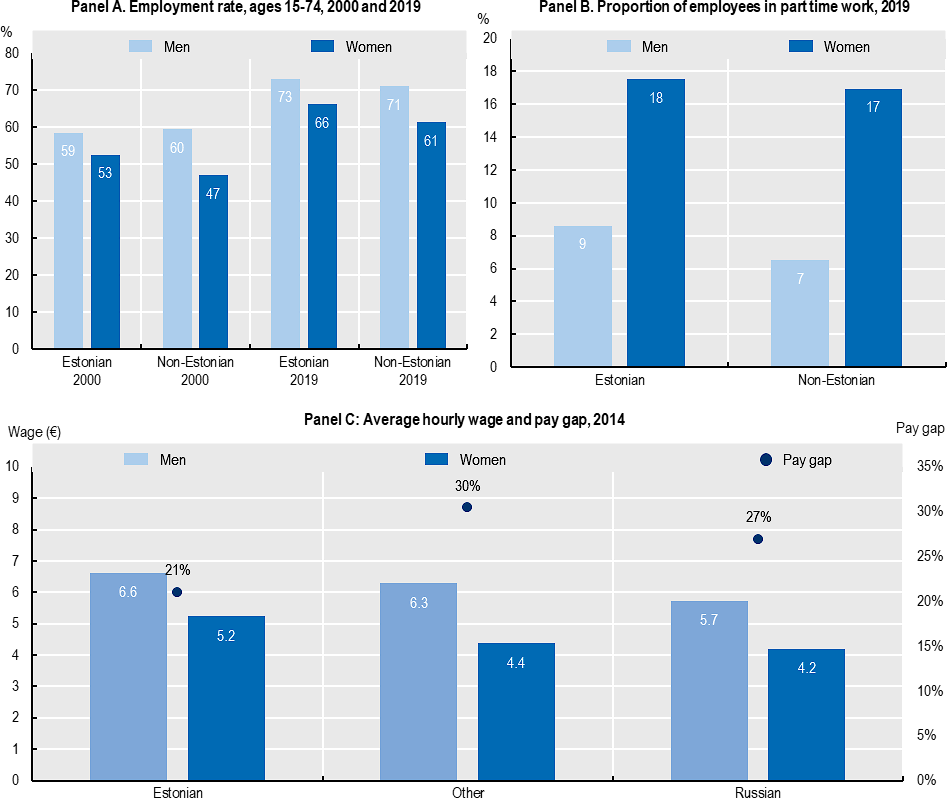

2.2.5. Gender gaps are larger among the non-Estonian population

Figure 2.5 shows that the gender employment gap was consistently larger among the non-Estonian than the Estonian population (Box 2.1). Additionally, non-Estonian women were 5 percentage points less likely to be in work than Estonian women. At the same time, Russian and other non-Estonian women are receiving less pay per hour relative to their male counterparts compared to Estonian women: the hourly pay gap was 30% among Russians and 27% among other non-Estonians, compared with the considerably lower 21% gap among Estonians. For every hour worked, Russian and other non-Estonian women receive lower pay (about EUR 1) compared to their Estonian counterparts. (These figures relate to the hourly wage gap and are therefore not directly comparable with the data in Figure 2.4 which relate to the monthly wage gap).

Figure 2.5. Gender gaps in labour market outcomes are larger for non-Estonians

Note: Hourly wages refer to gross hourly wage.

Source: Panel A and Panel B: Statistics Estonia. Panel C: Based on Structure of Earnings Survey, 2014, used in Täht, K. (Toim.) (2019). Soolise palgalõhe kirjeldamine ja seletamine – tehniline ülevaade. RASI toimetised nr 10. Tallinn: Tallinna. Ülikool.

It is encouraging that Figure 2.5 shows that the overall decrease in the gender employment gap has been driven by non-Estonians. While employment has increased rapidly for non-Estonian women, Figure 2.5 does not show any large differences in the proportions of employees in part-time work. Although it is clear that more can be done to address the intersectionality between ethnic and gender inequalities in Estonia, some improvements have materialised.

Box 2.1. Socio‑economic inequalities by “ethnic nationality”

Differences between Estonians and non-Estonians – throughout, the terms “Estonian” and “non-Estonian” refer to ethnic origin and not citizenship. Such differences today largely originate from events in the aftermath of the Second World War as the former Soviet Union started to integrate Estonia into the Union. Between 1945 and 1989 the number of Russian speakers living in Estonia grew. For largely administrative reasons, Russian-speakers tended to settle in their own, separate communities. This contributed to sustained segregation of population groups in terms of employment participation, education systems and residential areas (Saar, Krusell and Helemae, 2017[16]; Vetik, 1993[17]).

In 2020, Russian people still constituted a large minority in Estonia, making up almost one‑quarter of the population (Statistics Estonia, 2021[18]). However, “Russians” are no longer a homogeneous group, and some, particularly young, urban and economically better off Russians are well integrated into Estonian society (Koort, 2014[19]). Other minority ethnic groups in Estonia include Ukrainians, Belarusians and Finns (Statistics Estonia, 2021[18]).

2.2.6. Gender gaps in entrepreneurship activity are relatively large in Estonia

Small businesses and entrepreneurs make up a large portion of business activity in Estonia. Overall, micro- and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) contribute to 78% of employment and 76% of value added (OECD average, 69% and 59%) (OECD, 2021[20]). There are also more female entrepreneurs in Estonia than elsewhere in OECD (Figure 2.6). The country has among the highest proportion of working-age women who are actively involved in starting a business or are owner-operators of young businesses (12%) across the OECD (8%). Another way to estimate innovativeness is to consider the number of patents filed. Looking at the number of European patent applications per million people, for instance, Estonia ranks 24th, ahead of its neighbours Lithuania and Latvia (31st and 32nd) (European Patent Office, 2020[21]).

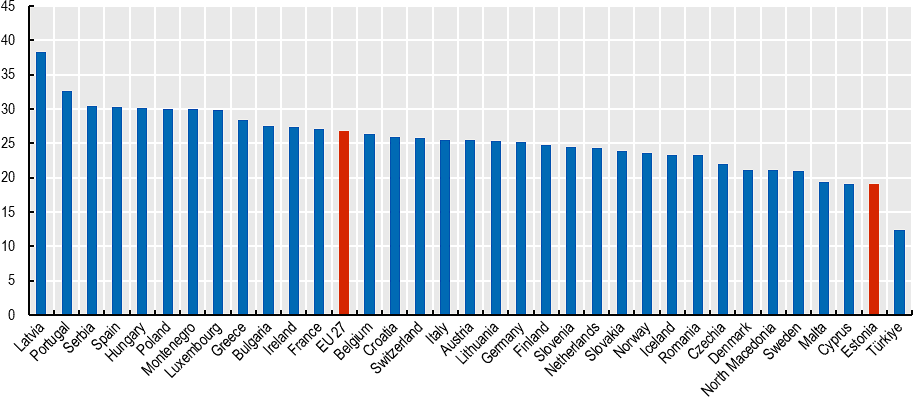

Despite high overall levels of entrepreneurship, Estonian is still lagging behind its comparators in terms of gender equality (Figure 2.7). In 2020, 28% of self-employed workers in Estonia were women, compared to 33% across the EU. Female‑run firms are also more likely to be small-scale, solo self-employed, than male‑run firms in Estonia. This reflects what women expect from their businesses too. Fewer self-employed women report expecting to see high employment growth in their firms, compared to their female counterparts in the EU (OECD, 2020[22]). Indeed, out of all self-employed business owners that also employ others, the proportion of women in 2020 was lower in Estonia than across most of the OECD: at 19% in Estonia, it was only higher than in Türkiye at 12%, and lower than the EU-wide average at 27%. It may therefore be justifiable that initiatives to improve the opportunities for female entrepreneurs focus on helping women to scale up their businesses, hire employees and increase profitability.

A favourable business environment for start-ups will have contributed to high overall numbers of entrepreneurs. Estonia ranked among the most favourable in the EU for regulatory environment due to the low start-up costs and ease of complying with taxes (OECD, 2021[23]). While Estonia ranks around the same as the EU-average in terms of the administrative burden experienced by businesses, the government is actively working to reduce it. The Zero-Bureaucracy project initiated in 2015 and the Reporting 3.0 programme implemented in 2018 to automate business reporting will both play a role in easing the administrative burden and facilitate entrepreneurship (OECD, 2020[24]).

Figure 2.6. A relatively high proportion of women are engaged in early-stage entrepreneurship

Notes: The total early-stage entrepreneurship rate presents the proportion of the adult population (18‑64 years old) that is actively involved in starting a business or who is the owner-operator of a business that is less than 42 months old. All OECD countries participated in the GEM survey between 2016 and 2020 except for Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Iceland, Lithuania and New Zealand. The following countries did not participate in the survey in every year (years of participation are indicated): Australia (2016‑17, 2019), Austria (2016, 2018, 2020), Estonia (2016‑17), Finland (2016), France (2016‑18), Hungary (2016), Ireland (2016‑19), Japan (2017‑19), Latvia (2016‑17, 2018‑19), Mexico (2016‑17, 2019), Norway (2019‑20), Portugal (2016, 2019) and Türkiye (2016, 2018).

Source: GEM survey.

Figure 2.7. Estonia is lagging behind its European counterparts on female entrepreneurship

Source: Eurostat.

Estonia has also focused on improving conditions to increase innovation within Small, Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and to support entrepreneurs to scale their businesses (OECD, 2020[22]). Initiatives have focused on increasing innovation and support growth, with some initiatives having been specifically tailored to under-represented groups including women, youth and unemployed people (OECD, 2021[23]). For instance, in 2012, the ETNA Microcredit scheme was launched to provide mentoring and training support to female rural entrepreneurs (OECD, 2014[25]). The Estonian Women’s Studies and Resource Centre (ENUT) also leads a network of NGOs that support women’s entrepreneurship, for instance by organising an annual conference where around 200 female entrepreneurs participate. Another wide‑reaching project was the 5by20 initiative launched in 2010 by the Estonian Association of Business and Professional Women with a number of partners, notably Coca-Cola. It set out to help female entrepreneurs to overcome some of their most common challenges, and by 2020 1 780 women had participated.

2.3. Drivers of gender gaps in labour supply and earnings

This section examines some possible causes of gender gaps in labour supply and earnings. First, it considers unequal work-life balance opportunities for men and women in Estonia relative to in the rest of the OECD countries. Second, it discusses horizontal segregation, that is, the fact that women are overrepresented in sectors and occupations characterised by lower earnings. It considers vertical segregation, in other words, that women progress more slowly than their male counterparts in the same industry and occupation as men, and ends with indications on the prevailing attitudes in Estonia regarding the role of men and women.

2.3.1. Women shoulder the majority of unpaid work

Across OECD countries, women do more of the unpaid work in the home, such as cleaning, cooking and caring for children and other relatives in need (Meriküll and Tverdostup, 2021[1]). The norms dictating women to take on this labour often prevent women from focusing on their careers or paid activities to a similar extent to men. Women often end up doing more total (paid and unpaid) work than men, and Estonian women spend 70 minutes a day more in total work than men do, which is considerably higher than the OECD average of 27 minutes. Gender gaps are larger in Estonia than in the OECD since women and men tend to spend a similar number of hours in paid work, but on top of this, women also spend significantly more time than men doing unpaid work in the home while men take leisure time. Meanwhile, in other countries across the OECD, women’s longer hours in unpaid work tend to be counterbalanced by shorter number of hours in paid work (such as Japan and Australia). Alternatively, in some countries (such as Denmark and Sweden), women and men spend a similar number of hours in paid work and also a similar number of hours in unpaid work (OECD Gender Data Portal, for a detailed analysis on the United Kingdom, see (Bangham and Gustafsson, 2020[26]).

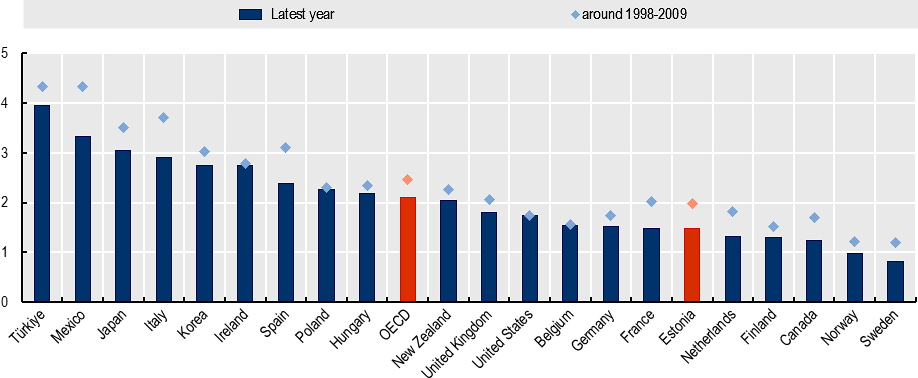

Before the pandemic, women spent on average 2.1 hours more than men doing unpaid work across the OECD. In Estonia, the difference is smaller, with women doing 1.5 hours more on unpaid house work compared to men (Figure 2.8). This places Estonia close to France and the Netherlands but still some distance from the leading countries Norway and Sweden where women did 1.0 hour and 0.8 hours more than men, respectively.

Figure 2.8. Women are shouldering the heaviest burden of unpaid housework

Note: Time spent in unpaid work includes: routine housework; shopping; care for household members; childcare; adult care; care for non-household members; volunteering; travel related to household activities; other unpaid activities. For more information on the exact categories used for each country and a detailed breakdown by sub-activity refer to the OECD Time Use Database available via the following link: OECD Time Use Database., https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54757.

Source: OECD Time Use Database for latest year and OECD (2011), “Cooking and Caring, Building and Repairing: Unpaid Work around the World” in Society at a Glance 2011: OECD Social Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2011-3-en, for data around 1998‑2009.

This unequal sharing of unpaid work is consistent with the variation of gender gaps in employment rate and labour earnings by age. During their prime career years, women to a larger extent than men work in less intensive or time‑consuming jobs, move to part-time work, have flexibility in work hours, and accept shorter commutes. This translates into fewer options during job search, slower wage growth and sluggish progression, see Chapter 3 and OECD (2021[13]).

As would be expected, considerably more women than men report that they feel overburdened by housework in 2021:2 half of women in Estonia (50%) answer positively to the question “Have you ever felt that you have too big a share of household chores on you?”, while only a minority of men (20%) do. The survey results also suggest that people are ready for change: a large majority (74%) of men believe that men should be more involved in the care and parenting of children (Estonian Gender Equality Monitoring, 2021[27]).

During the pandemic, the time that needed to be spend on homework increased, and it was women who picked up the majority of the extra work. For instance, while children had previously had meals in school, now parents had to prepare three meals a day instead of two, and provide extra support with learning and homework. In focus groups, women in Estonia also emphasised the extra “invisible” work that was required during the pandemic, including home planning and management (Haugas and Sepper, 2021[28]). Both seen and unseen unpaid labour increase if there are several children in the household or if some children have special needs. Women reported different ways of coping with the extra time pressures: some reported reducing the hours they sleep, decreasing their hours of paid work or giving up their employment completely. This can be contrasted against how men talked about additional pressures on their time during the pandemic. Rather than reallocating time from sleep or paid work, fathers lamented having less time to themselves (Haugas and Sepper, 2021[28]).

2.3.2. Gender health gaps mean headwinds for women’s labour market engagement

Estonia has seen dramatic increases in life expectancy since the beginning of the transition period: life expectancy at birth has risen from 70 year in 1989 to 79 years in 2020 (OECD, 2021[29]). While these gains should be celebrated, they also pose particular challenges for women. The official pension age for both men and women is 63 year since 2016 (up from 61 for women). However, because women typically live for almost 9 years longer than men, they will spend longer in retirement and are more exposed to poverty risks (OECD, 2021[3]). Old-age pension payment rates are not high and old-age relative poverty – the share of people whose income falls below half of the overall median income – in Estonia, at 38% was among the highest across the OECD countries in 2018, third after Korea (43%) and Latvia (39%) (OECD, 2021[30]).

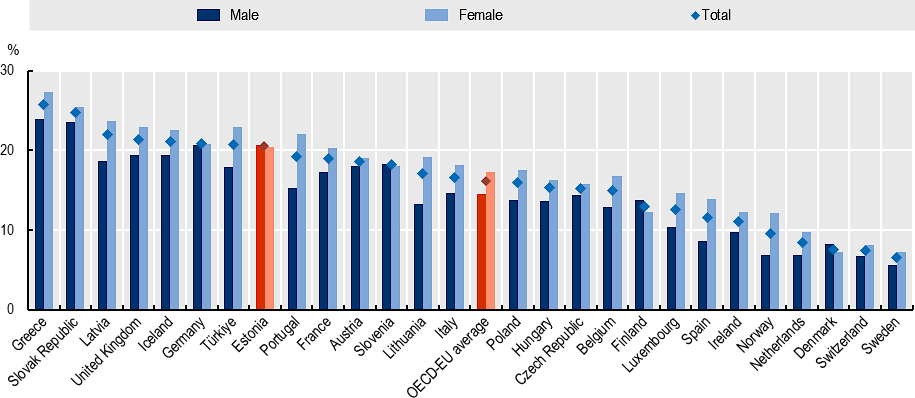

Population ageing also leads to increased age‑related care needs. The proportion of people age 65 had grown to 20% of the population in 2020 and its old-age dependency ratio was already 5 percentage points higher than that in the OECD (Annex Table 2.A.2). The expected number of years in old-age poor health (calculated as the overall life expectancy at birth minus the expected healthy life expectancy at birth) increased from 8 in 2000 to 10 in 2019 (WHO, 2020[31]). In Estonia, around one in five (21%) individuals aged 65 years or over reported long-standing severe limitations in usual activities due to health problems in 2020, as opposed to one in six (16%) on average in other OECD countries which are also EU members (Figure 2.9). Figure 2.9 shows that when self-reported poor health is considered there are small gender differences in Estonia. However, it should be kept in mind that this refers to people’s own opinions. When looking at specific outcomes, men’s health tends to be significantly worse than women’s in Estonia, which represents a significant barrier to men’s employment in later life (Box 2.2).

Figure 2.9. The Estonian population is experiencing worse health in later life than in most other EU countries

Note: Data for Iceland and the United Kingdom refer to 2018.

Source: Eurostat, Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem by sex, age and income quintile, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/HLTH_SILC_12__custom_1368548/default/table?lang=en.

An ageing population and worse health in old life can mean that the “sandwich generation” of women caring both for children and elderly parents become even more squeezed. In Estonia, informal care is the backbone of current long-term care provisions. Indeed, Estonia had among the highest proportion of people in the EU with care responsibilities for children and adult relatives, second only after Ireland (Eurostat, 2019[32]). According to the Estonian Social Survey, women made up almost 60% of informal long-term carers in 2020, and women assisting elderly relatives and family members with disability were more than twice as likely as their male counterparts to devote 20 hours or more per week providing such care. These long care responsibilities can curtail family members’ – especially women’s – ability to participate actively in the labour market at an increasing rate. Further increases in longevity (especially when this means more years in ill health) in future may well put more unpaid work towards the already squeezed women in mid-career.

Caring for elderly family members is not a choice in Estonia, but a legal obligation. According to Article 27 of the Constitution of the Republic of Estonia, “the family is required to provide for its members who are in need”, i.e. typically elderly individuals and non-elderly individuals with disability. In addition, Chapter 8 of the Family Law Act establishes a duty to provide maintenance “arising from filiation”. It stipulates a two generations up and down legal obligation to assist family members unable to cope by themselves: “adult ascendants and descendants related in the first and second degree are required to provide maintenance” (Article 96(1)). Changes to the Social Welfare Act and Family Law Act – the second quarter of 2022 – remove second degree relatives from the list of persons required to provide care and assistance. Nevertheless, these legal provisions contributes to the view that care should primarily be undertaken in the household; public authorities should first make sure that the family of the person in need is not capable of giving assistance themselves before providing tax-financed public support.

The lower priority given to long-term care becomes clearer when considering public spending on the health care system. Estonia spent 7% of GDP on health care in 2018 compared to 10% in the EU on average (Eurostat, 2021[33]). The health care system is instead funded by private funds to a larger extent than in other European countries. Out-of-pocket spending is 24% of costs in Estonia compared to 16% on average across the EU (European Commission, 2019[34]). At the same time, people in Estonia report having one of the highest levels of self-reported unmet medical need in the EU with 12% of Estonians reporting that their health needs were not met in 2017 (compared with just under 2% across the EU (European Commission, 2019[34]).

To support increased female labour supply it is important to complement efforts to counter the fragmentation of long-term care between health and social services by strategies to significantly increase public spending in order to improve coverage of formal health and long-term care services. From an efficiency and equity point of view, there is limited room for additional public funding for long-term care to flow from social security contributions and payroll taxes. The tax wedge, which measures the extent to which labour income is taxed, is higher in Estonia than on average in other OECD countries (OECD, 2021[35]). Further increasing the tax burden would be detrimental to employment, especially for low-income workers, and thus to equity in a context where Estonia already lags behind in terms of income inequality and poverty (OECD, 2017[36]). Another area for intervention could be to address some of the underlying causes for the gender health gap, such as macho behaviour, dangerous workplaces and high alcohol consumption.

Box 2.2. Men’s poor health is an obstacle to employment in later life

One area where men are underperforming relative to women is in personal health. Traditional gender norms negatively affect the health of both men and women, but men are hit the hardest. On one hand, the overt social and economic inequalities more commonly experienced by women, such as lower rates of employment, less pay for work of equal value, under representation in leadership positions, and the higher level of psychosocial stressors and problems, from caregiving burden to intimate partner violence, are all viewed as negatively affecting women’s mental and physical health. Meanwhile, the average man enjoys more economic opportunities, privileges and power than the average woman.

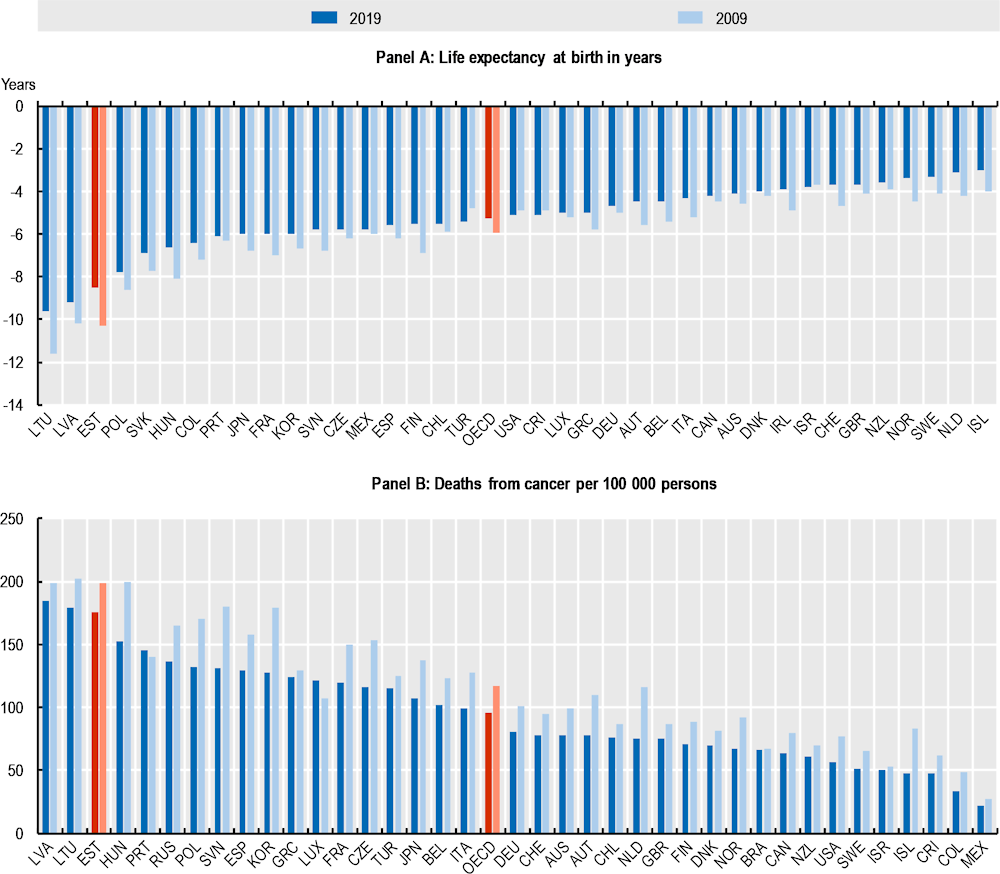

Figure 2.10. Men’s poor health is an obstacle to later-life male employment

Note: Data in Panel B refers to 2019 or closest year. Closes year is 2016 for Belgium, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom; 2017 for Canada, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Italy, Mexico, Spain and the United States; 2018 for Austria, Chile, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Israel, Japan, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal and Sweden.

Source: OECD.Stat.

However, on the other hand, men are overrepresented in occupations with higher rates of workplace fatalities and injuries, such as construction, mining, and the military (Courtenay, 2000[37]). Moreover, masculinity norms encourage risky and unhealthy behaviours, including violence, reckless driving or excessive consumption of unhealthy food, alcohol, tobacco, or drugs. Despite this, men are less likely to consult a doctor when in need (Murray-Law, 2011[38]; Barker, 2005[39]). Partly as a result of the greater risks to personal health among men, women live on average until 84 while men on average live 5 years shorter, to 78 years across the OECD. Estonia has among the largest gender gaps observed across the OECD: life expectancy at birth was 9 years shorter for men than women in 2019 (Figure 2.10, Panel A). Gender differences in the proportional number of deaths from cancer (Figure 2.10, Panel B) is close to the mirror image of life expectancy. Again, large gender health gaps can be observed in Estonia: there were 176 more men than women per 100 000 persons who died from cancer in 2019. More can be done to build on the small improvements that have happened in Estonia since 2009.

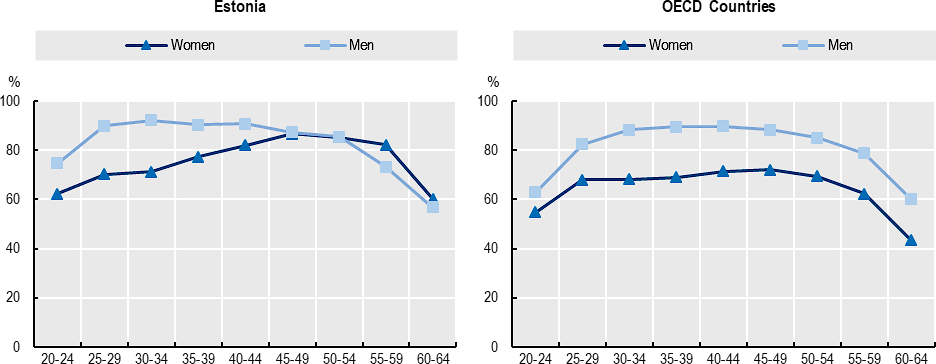

2.3.3. Women are more likely than men to work in later life

Although women are less likely to be employed than men in their early and mid-careers because of care responsibilities, this changes later on in working life: among older workers (age 55‑64) women are more likely to work than men (Figure 2.11). This stands in sharp contrast with the average OECD pattern: the probability of employment of 55+ women is more than 15 percentage points lower than that of their male counterparts OECD-wide, but in Estonia older women are nearly 5 percentage points more likely than older men to be employed. The employment rate of older women also catches up with that of older men in Finland, Latvia and Lithuania (although Estonia is the only OECD country where the gender employment gap reverses permanently from age 55 onwards). This pattern is consistent with the significantly lower number of healthy life years of Estonian men.

Figure 2.11. Women’s employment rates continue to increase into older ages than men’s

Source: OECD Employment Database, http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/onlineoecdemploymentdatabase.htm.

While poor health among older men will be a significant contributor to the lower employment rate in this group (Box 2.2), there are some other key factors as well. Just after the start of the transition period in 1989, inactivity rates rose dramatically, especially among older workers. Part of the reason might be that firm sizes were shrunk and workers let go to address the overindustrialisation sustained during the Soviet era. At the same time, there was significant industrial transformation, encouraged by economic policy, away from industry and agriculture and toward service sectors. Owing to the worker composition in declining sectors, blue‑collar, lower-educated and older workers were particularly affected (Saar and Täht, 2006[40]; Klesment and Leppik, 2012[41]). In addition, the labour market has become more flexible and insecure, with increasing lay-offs and job-to-job moves, which increased the risk of unemployment and the labour market has increasingly become oriented to skills profiles of young people, which means that older workers are struggling to remain in work and become rehired when laid off (Saar and Täht, 2006[40]). However, it seems that pension reforms and strengthened labour markets through the 2000s have had positive effects on the employment of older workers (Unt, Kazjulja and Krönström, 2020[42]).

Current employment is not just a determinant for present living standards but is also a source of pension contributions or a complement to low pension incomes, and women often need to keep working to reduce the stark poverty risks (see above). While the level of pension payments are low in Estonia, the gender pension gap is the lowest in the OECD (OECD, 2021[43]). This is because pension income in Estonia hardly depends on lifetime earnings. The pension system is currently undergoing a change which is expected to make the system even less dependent on previous earnings (Box 2.3), although some critics have warned of the opposite (see Piirits (2022[44])).

Box 2.3. The Estonian pension system

The current Estonian pension system is built on three pillars. The first is state‑funded and calculated by summing up a base part which is the same for everyone; years of pensionable service; insurance part depending on the social tax paid for one’s income. As such, it is based on the number of years worked, taking into account life events like childbirth. The second pillar is also state‑funded but depends more on contributions made by the individual. This has been compulsory for those born after 1983. The third is privately-funded and completely voluntary.

This system will start to change from 2021 as the calculation for the first pillar is modified by replacing the insurance part is replaced by a joint part which is decided in part by an insurance component and in part by a solidarity component. The state has also temporarily suspended the second pension pillar contributions between 1 July 2020 and 31 August 2021. From 2021 onward, the contributions to this pillar are voluntary.

Overall, these changes mean that pension incomes will in future be more equal and determined to a smaller degree by the sum of lifetime earnings from paid work than in the previous system.

Source: Design your own pension, Estonia, https://pension.sotsiaalkindlustusamet.ee/en/main.

2.3.4. Horizontal segregation between men and women

Women are overrepresented in industries and occupations characterised by low earnings and slow wage growth and this has a significant impact on gender gaps in the labour market. Indeed, the three areas of education, occupation and industry sector have been found to explain a large proportion of the gender wage gap in Estonia (Meriküll and Tverdostup, 2021[1]). This section illustrates some of these issues.

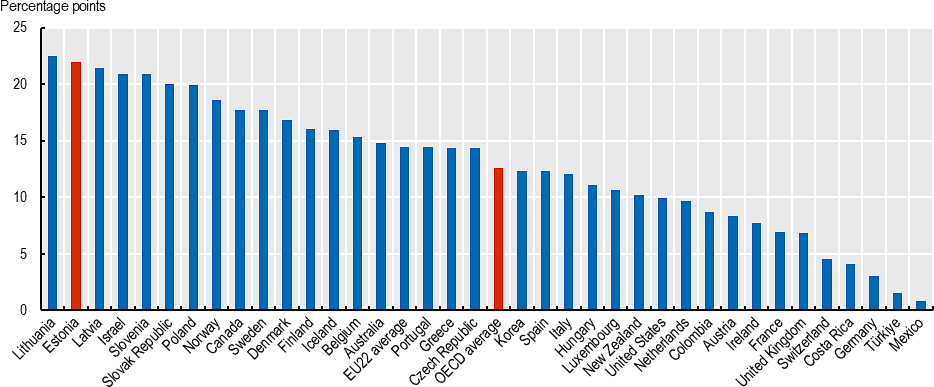

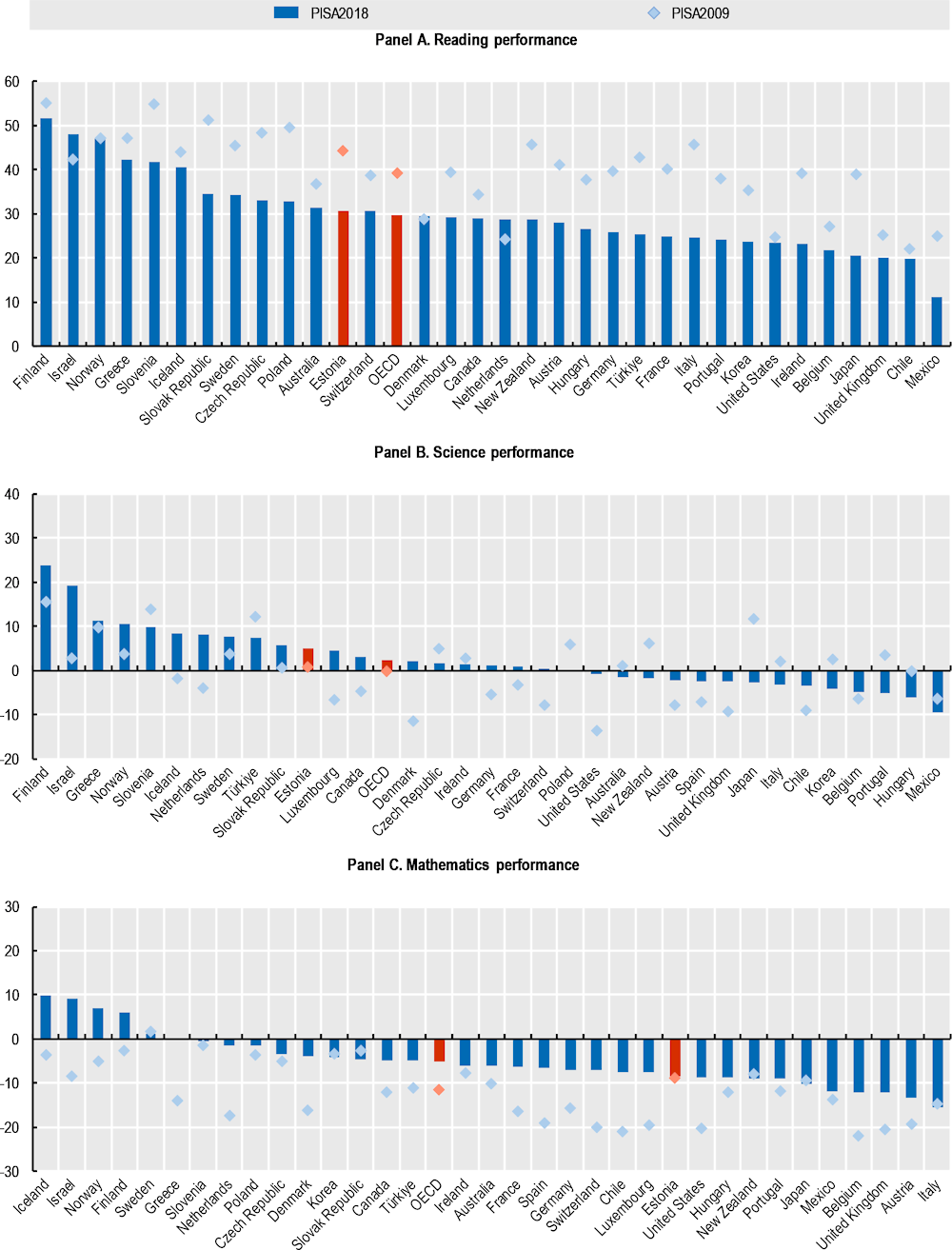

The Estonian education system stands out as very high performing OECD-wide: in 2018 it ranked first among the OECD countries in OECD PISA scores on reading literacy and science and third in mathematics. In more gender-equal societies, the gap in PISA results for boys and girls is smaller than in countries with low gender equality rates (Chivite Monleón, 2020[45]). In Estonia, the system in place ensures that students from different socio‑economic backgrounds achieve similarly high results and the gender gap in the OECD PISA scores has decreased over time (Tire, 2020[46]). In Estonia this translates to high proportions of young women with tertiary education: the difference in the proportions of young women and young men who have attained tertiary education is 22 percentage points. This gender gap to the disadvantage of young men is similar to that in Lithuania and Latvia but is considerably higher than the OECD average difference of 13 percentage points (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. Educational attainment is higher for young women than young men

Note: A data point above 0 means there are more women than men attaining tertiary education. A data point below 0 means there are more men than women attaining tertiary education.

Source: OECD, Education at a Glance 2021, Table A1.2, https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf.

How well a university-level education pays off in the labour market depends partly on the subjects that are studied and the choice of subjects for specialisation start to take shape in childhood. In school, girls outperform boys in reading and science, but boys outperform girls in mathematics (Figure 2.13). Across all OECD countries, girls tend to score higher than boys in reading (Figure 2.13, Panel A). In Estonia the gender gap in reading is greater than the OECD average to the advantage of girls, albeit that the gap has decreased over time. In Estonia, girls are also more likely to outperform boys in science than across the OECD (Figure 2.13, Panel B) and girls’ performance has improved relative to boys’ over time, resulting in a growing gap to girls’ advantage. In mathematics, boys are most likely out of the three subjects to perform better than girls across the OECD Figure 2.13, Panel C). In Estonia the gender gap to the advantage of boys is even larger than the OECD average, and there has been no improvement since 2009.

Figure 2.13. Girls are better in school but boys still outperform in maths

Source: OECD, PISA 2018 Results: What Students Know and Can Do: Student Performance in Reading, Mathematics and Science (Volume I), https://www.oecd.org/pisa/Combined_Executive_Summaries_PISA_2018.pdf.

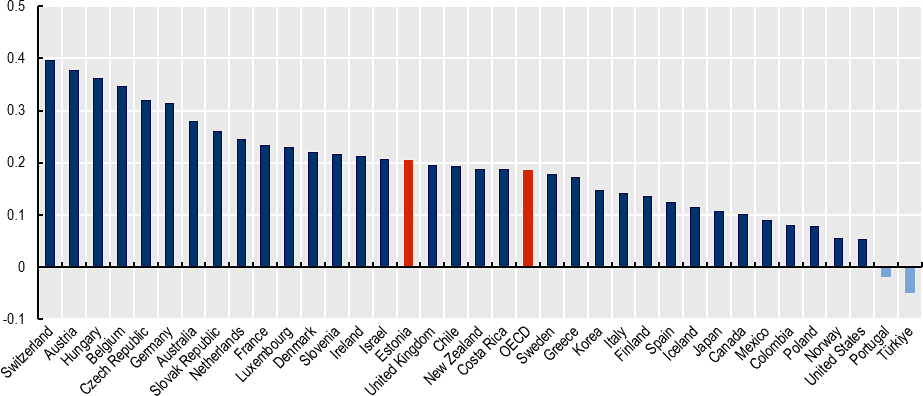

The stereotype that “math is not for girls” remains widespread. To gauge the extent of this stereotype, consider whether mathematics is viewed by parents as a more appropriate educational and career choice for their sons than for their daughters. Figure 2.14, based on Breda et al. (2020[47]), shows the difference in the share of boys and girls who, conditional on their math performance, report in the PISA survey that “[their] parents believe that math is important for [their] career”. The mathematics-related stereotypes are strong for children in Estonia: at 0.21 the gender gap is slightly greater than that across OECD countries, which is 0.19 (see Chapter 6 for a policy discussion on how to change these trends).

Figure 2.14. The belief that “maths is for boys” still prevails

Notes: Light blue bars indicate that results are not statistically significant. OECD is the simple cross-country average. Regressions are done country by country, and systematically include a variable accounting for math performance whose estimated effect is given in Table S1 in: (Breda et al., 2020[47]). All variables are standardised to have a weighted mean equal to 0 and a weighted standard deviation equal to 1 in each country. Estimates and standard errors involving measures of ability are based on plausible values and account for measurement error in these abilities on top of standard sampling error.

Source: Table S2 in Breda et al. (2020[47]), “Gender stereotypes can explain the gender-equality paradox”, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008704117.

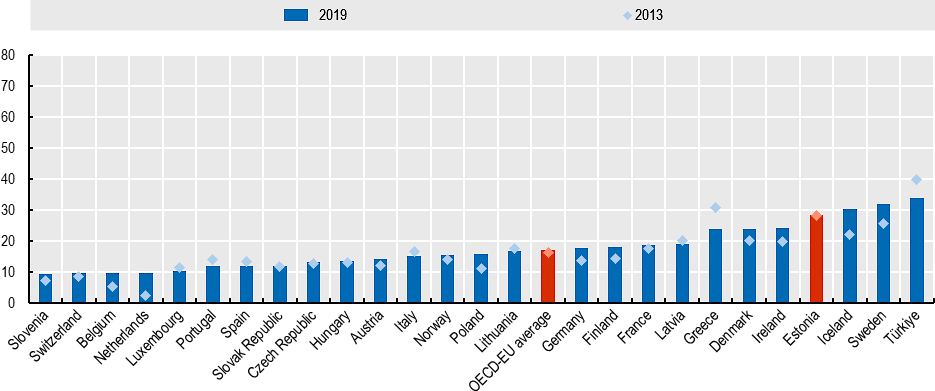

In part because of girls and boys attain different mathematics scores, young women and men grow up to make different educational choices. Across the OECD, young women are underrepresented among science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduates in information and communication technologies (ICT): under one in five graduates (17%) were women in 2019, and there had been practically no change since 2013 (Figure 2.15). Relatively more women graduate in ICT in Estonia, but women still constituted a small minority (28%) of STEM graduates in ICT in 2019, without any improvement since 2013.

The gender gaps in the ICT education have various implications. First, women are missing out on highly paid jobs since employees in the ICT sector receive the highest average gross monthly income in Estonia: on average 69% more each month than the average worker. By comparison, employees in accommodation and food service activities, where women are overrepresented, receive just under half (48%) of the average wage (Statistics Estonia, 2021[18]). Second, the jobs in the ICT sector are generally relatively safe to labour market disruption caused by robotisation and automation, so in future can mean that women are more likely to work in relatively insecure jobs compared to men (OECD, 2016[48]). Third, the gender gap in this sector will in part be due to young women who were not encouraged to develop their interest and talent and subsequently end up working in a different sector. This is a potentially high opportunity cost for the country as it needs to meet the growing demand of skills related to the development of information technology and artificial intelligence.

Figure 2.15. Young men are more likely than young women to study ICT

Note: Data refer to tertiary education (ISCED 5‑8) and VET (ISCED 35 and 45).

Source: Eurostat (2021) Database on Graduates by education level, programme orientation, sex and field of education, https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=educ_uoe_grad02&lang=en.

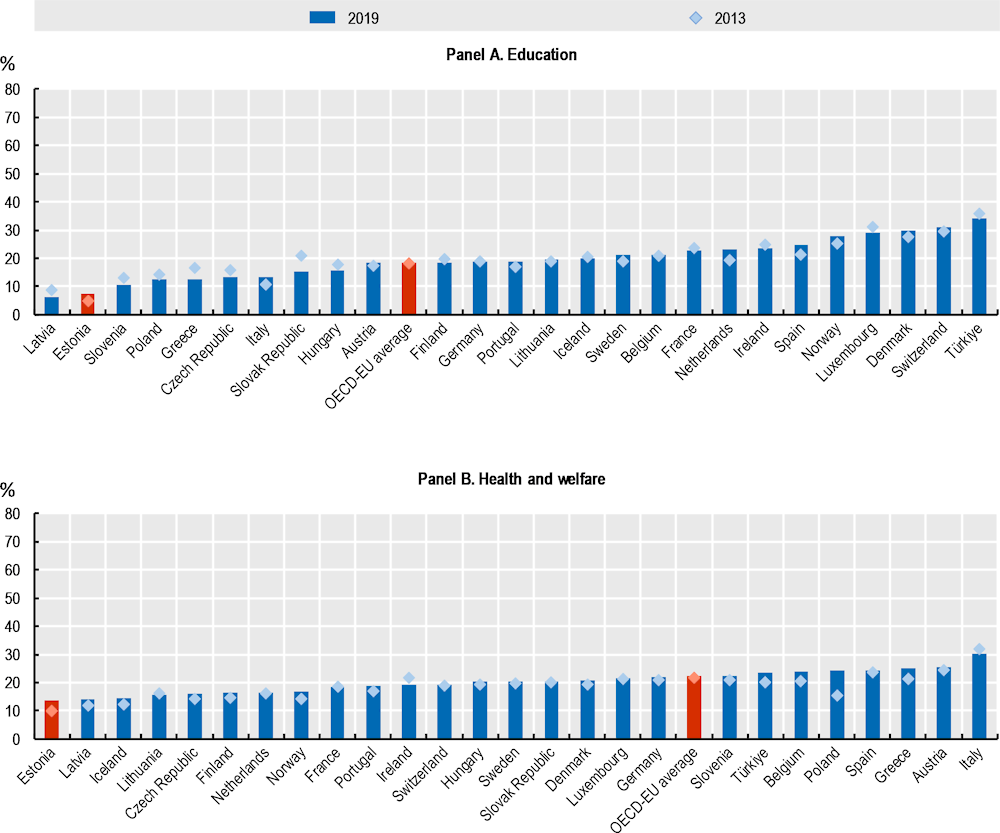

Whereas men are overrepresented among graduates studying ICT, women are overrepresented among graduates studying to work in the sectors of education and welfare. Only 8% of graduates in education are men, and similarly, men make up just 14% of graduates in health and welfare (Figure 2.16). Estonia has the lowest representation of men in these two sectors compared to OECD countries in the EU (Chapter 6 details policy to achieve better gender balances in this area). The concentration of women in these sectors mean that women are set to earn less than men from the start. While ICT is the highest-paying sector overall, monthly gross pay in education and human health and social work is close to the average (5% and 14% above the mean, respectively).

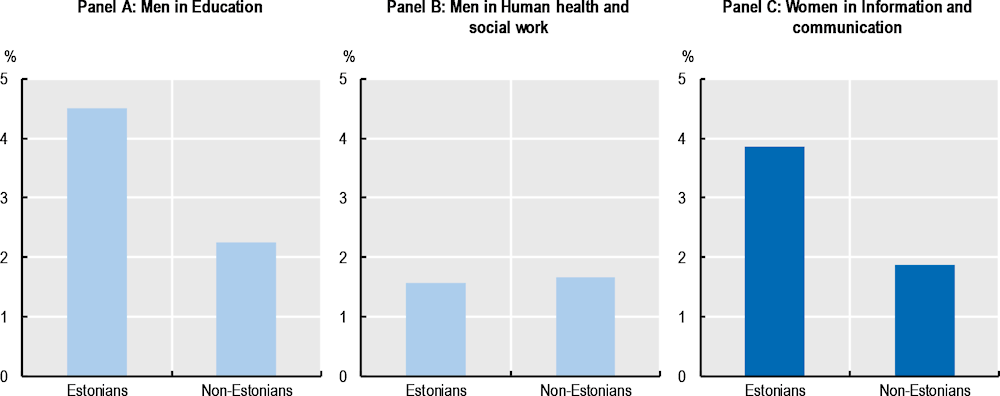

The large gender differences in education is mirrored in the labour market. Men are overrepresented in industry sectors such as information, technology and manufacturing whereas women are more likely than men to work in education, human health and social work activities (Statistics Estonia, 2021[18]). This labour market segregation is slightly different for Estonian and non-Estonian employees (Figure 2.17). A slightly higher proportion of Estonian men than non-Estonian men work in education while equally few Estonian as non-Estonian men work in human health and social work. Conversely, a slightly higher proportion of Estonian women work in information and communication than non-Estonian women.

Since the selection of boys and girls into different subject specialisms starts early and there are strong parental gendered expectations regarding school-age children, Estonia will need some ambitious policies to start decreasing the gender gaps across study fields and work specialisms (see Chapter 6). Attitudinal evidence shows there is some appetite for this. A small majority of Estonians (57% of Estonian men and 58% of Estonian women) agree that “There should be more men working in social services and health care”. A smaller share of non-Estonians support this claim too (45% of non-Estonian men and 49% of non-Estonian women) (Estonian Gender Equality Monitoring, 2021[27]).

Figure 2.16. Female students are overrepresented in education, health and welfare

Note: Data refer to tertiary education (ISCED 5‑8) and VET (ISCED 35 and 45). Instead of 2013, data refer to 2014 for EU and Türkiye and to 2015 for Poland.

Source: Eurostat (2021) Database on Graduates by education level, programme orientation, sex and field of education https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=educ_uoe_grad02&lang=en.

Figure 2.17. Gender-based segregation intersects with ethnic differences on the labour market

Note: This figure shows proportions of a group that works in each sector so is not directly comparable to the previous figure.

Source: Statistics Estonia.

2.3.5. Vertical segregation between men and women

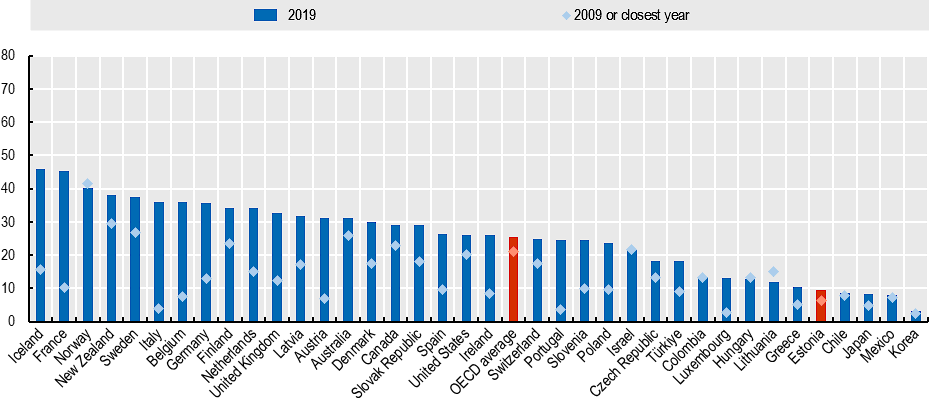

Women in a given job tend to experience slower career progression than their male counterparts in the same sectors and occupations. Considering the top of the pyramid first – the boardroom – the gender gap in Estonia is remarkably large. While leading countries like Iceland and France have women on nearly half (46% and 45%) of their boardroom chairs, only 1 in 10 (9%) of boardroom seats are held by women in Estonia (Figure 2.18). Moreover, there has been a dramatic change over the past 10 years in leading countries (with the exception of Norway where it was relatively common for women to be on boards back in 2009) whereas not much has happened in Estonia or countries like Greece, Lithuania and Hungary.

Figure 2.18. Estonia has among the most male‑dominated boardrooms in the OECD

Note: Instead of 2009 data refers to 2016 for New Zealand, Australia, Canada, United States, Switzerland, Israel, Colombia, Chile, Japan, Mexico and Korea.

Source: OECD Gender Data Portal: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/employment.

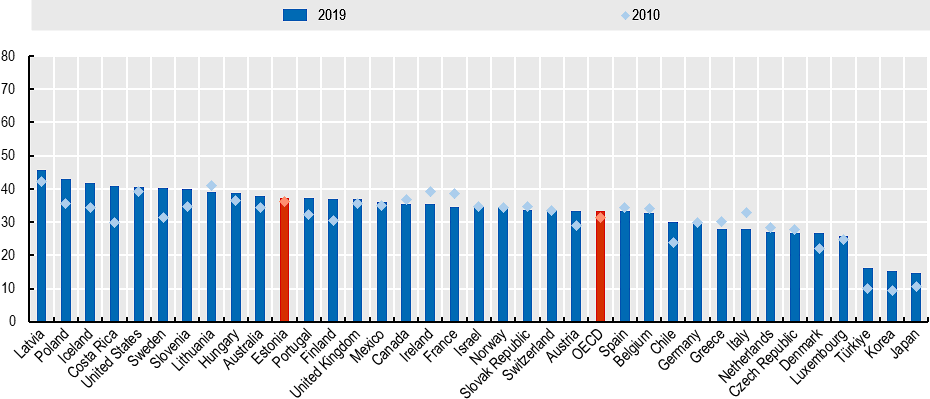

Going down one step on the hierarchy and consider the share of managers who are female, the gaps are smaller: 37% of managers in Estonia are female, which is slightly above the OECD-wide average of 33% (Figure 2.19). However, among the top performers, Estonia, Lithuania and the United States and Lithuania have not seen an increase in the share of female managers since 2010: while Estonia ranked 8th in 2010, it had fallen to rank 11th by 2019.

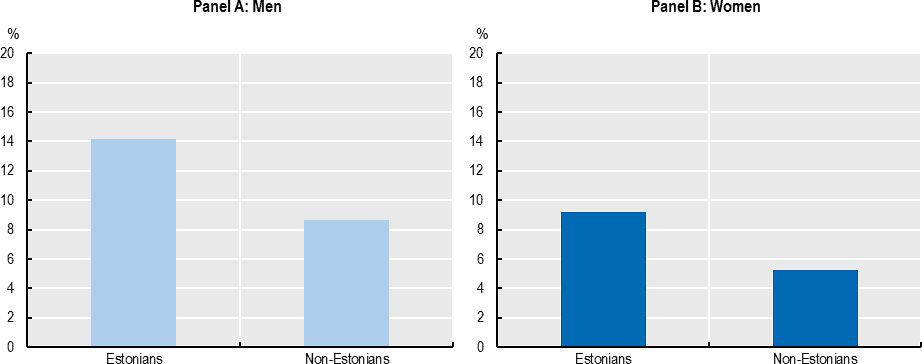

Disadvantage compounds if nationality is taken into account, since non-Estonians are less likely to work in managerial positions than Estonians (Figure 2.20). In fact, the gap between the share of Estonian and non-Estonian men who work in managerial positions is similar to that between Estonian men and Estonian women. It follows that non-Estonian women are facing double disadvantages: while nearly 3 in 20 (14%) Estonian men work in managerial positions, only 1 in 20 (5%) non-Estonian women do.

Considering attitudes reported in the (Estonian Gender Equality Monitoring, 2021[27]) around the value of women for businesses it is not so surprising that the observed overall gender gaps are so large. While a majority (59%) of Estonian women agree with the statement that “Businesses would benefit from more women in executive positions compared to the current situation”, only 36% of Estonian men agree. Similar gender gaps in attitudes were observed among non-Estonian women (52% agree) and men (36% agree). While these findings lack rigorous statistical significance they suggest there may be some scope for improvement in supporting conditions that allow women to break through the glass ceiling.

Figure 2.19. There has been no increase in the proportion of female managers since 2010

Note: Instead of 2010, data refer to 2013 for Mexico. Instead of 2019, data refer to 2018 for Australia, 2017 for Israel, and 2014 for Canada.

Source: OECD Gender Data Portal: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/employment.

Figure 2.20. Gender inequalities intersect with ethnicity-based disadvantages

Note: This figure shows the proportion of women and ethnic nationality in managerial positions, not the proportion of managers by gender and ethnic nationality.

Source: Statistics Estonia.

2.3.6. Current gender stereotypes are rooted in history and culture

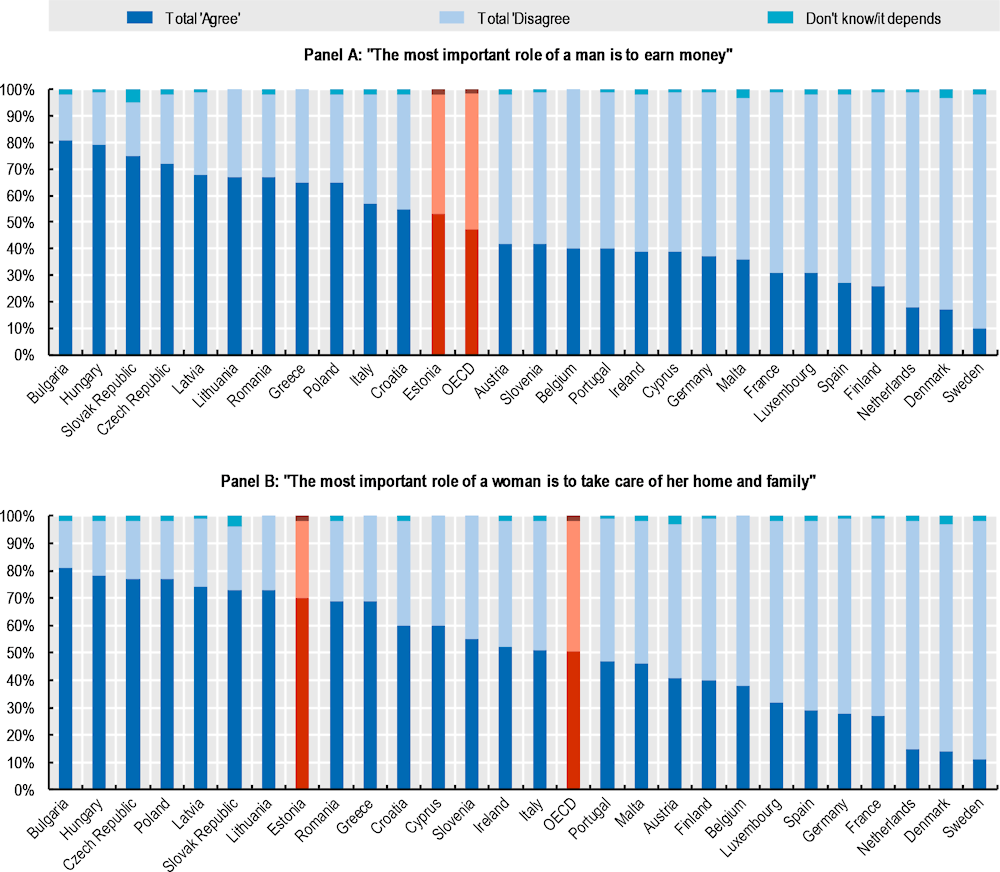

Part of the remaining differences in labour supply and earnings could be reinforced and maintained by norms and beliefs about how things should be. Survey evidence suggests that people in Estonia tend to have more traditional views than other OECD countries that are in the EU where men are traditionally seen as wage‑earners and women are seen as carers and home‑makers (Figure 2.21). For instance, men and women are a little more likely than men and women OECD-wide to agree with the traditional view that the most important role of a man is to earn money (53% in Estonia compared with 47% OECD-wide) (Figure 2.21 Panel A). People in Estonia have even stronger views of the role of women: 70% of respondents in Estonia agree with the statement that the most important role of a woman is to take care of her home and family, whereas half (50%) of respondents agree with this statement OECD-wide.

Figure 2.21. Gender views are more traditional in Estonia than in the rest of the EU

Note: OECD average refers to the simple country average of OECD countries that are also in the EU.

Source: 2017 Eurobarometer on Gender Equality, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=63613.

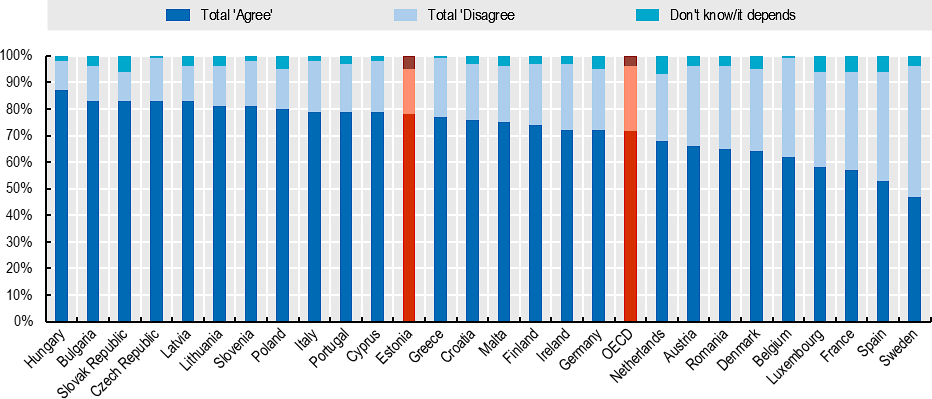

Pervasive gendered norms and stereotypes disadvantage women relative to men in the labour market. They include beliefs that women and men inherently have different intellectual skills, for instance, the idea that men are more rational than women who instead are governed by emotions (Figure 2.22). These beliefs are still common in public opinion across the OECD. For example, in all surveyed OECD countries but one (Sweden), a majority of people agree with the statement that “women are more likely than men to make decisions based on emotions”. People in Estonia are relatively traditional, with 78% agreeing with this statement compared to 71% across OECD countries in the EU. The belief that women’s decisions are governed to a larger extent by emotions than men’s decisions is an important barrier to their access to leadership positions in firms and to careers that involve sophisticated rational thinking such as STEM occupations (Chapter 6 proposes ways to encourage a quicker development of more equal norms).

Figure 2.22. Relatively few people in Estonia trust that women make rational decisions

Note: OECD average refers to the simple country averages of OECD member states in the EU.

Source: 2017 Eurobarometer on Gender Equality, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/api/deliverable/download/file?deliverableId=63613.

References

[26] Bangham, G. and M. Gustafsson (2020), The time of your life: Time use in London and the UK over the past 40 years, Resolution Foundation, https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/the-time-of-your-life/.

[39] Barker, G. (2005), Dying to be Men, Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203425664.

[8] Blau, F. and L. Kahn (2017), “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations”, Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 55/3, https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995.

[47] Breda, T. et al. (2020), “Gender stereotypes can explain the gender-equality paradox”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 117/49, pp. 31063-31069, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2008704117.

[45] Chivite Monleón, A. (2020), The gender gap in PISA 2018 Test scores in the European Union and the transmission of gender role attitudes, https://academica-e.unavarra.es/xmlui/handle/2454/37486.

[37] Courtenay, W. (2000), “Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 50/10, pp. 1385-1401, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1.

[4] Eamets, R. (2012), “Labour Markets in Estonia: Responding to the Global Finance Crisis”, CESifo DICE, https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/dicereport212-forum6.pdf.

[27] Estonian Gender Equality Monitoring (2021), “Estonian Gender Equality Monitoring Survey”.

[34] European Commission (2019), State of Health in the EU Estonia: Country Health Profile 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/state/docs/2019_chp_et_english.pdf.

[21] European Patent Office (2020), European patent applications, https://www.epo.org/about-us/annual-reports-statistics/statistics/2020/statistics/patent-applications.html#tab2.

[15] Eurostat (2022), Flash estimate - August 2022: Euro area annual inflation up to 9.1%, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/14675409/2-31082022-AP-EN.pdf/e4217618-3fbe-4f54-2a3a-21c72be44c53.

[9] Eurostat (2022), Population and social conditions, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/explore/all/popul?lang=en&subtheme=migr.migr_cit&display=list&sort=category&extractionId=MIGR_EMI2__custom_3283656.

[33] Eurostat (2021), Healthcare expenditure statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Healthcare_expenditure_statistics.

[32] Eurostat (2019), Reconciliation of work and family life - statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Reconciliation_of_work_and_family_life_-_statistics#One_in_three_in_the_EU_had_care_responsibilities_in_2018.

[12] Gustafsson, M. and C. McCurdy (2020), Risky business: Economic impacts of the coronavirus crisis on different groups of workers, Resolution Foundation, https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/risky-business/.

[28] Haugas, S. and M. Sepper (2021), COVID-19 pandeemia sotsiaal-majanduslik, Praxis, http://www.praxis.ee/tood/covid-19-sotsiaal-majanduslik-moju/.

[41] Klesment, M. and L. Leppik (2012), “Transition to Retirement in Estonia: Individual Effects in a Changing Institutional Context”, Estonian Institute for Population Studies, Vol. RU Series B No 65, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344162021_Transition_to_retirement_in_Estonia_Individual_effects_in_a_changing_institutional_context.

[19] Koort, K. (2014), “The Russians of Estonia: Twenty Years After.”, World Affairs, Vol. 177/2, pp. 66-73, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43556204.

[1] Meriküll, J. and M. Tverdostup (2021), “The Gap that Survived the Transition: The Gender Wage Gap over Three Decades in Estonia”, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Working Paper 206, https://wiiw.ac.at/the-gap-that-survived-the-transition-the-gender-wage-gap-over-three-decades-in-estonia-dlp-5884.pdf.

[38] Murray-Law, B. (2011), “Why do men die earlier?”, Monitor on Psychology, Vol. 42, http://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/06/men-die.

[7] Ngai, L. and B. Petrongolo (2017), “Gender Gaps and the Rise of the Service Economy”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 9/4, pp. 1-44, https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20150253.

[5] OECD (2021), General government debt, OECD, Paris, https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-debt.htm.

[3] OECD (2021), Improving the Provision of Active Labour Market Policies in Estonia, Connecting People with Jobs, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/31f72c5b-en.

[2] OECD (2021), Inequality, https://www.oecd.org/social/inequality.htm#gender.

[49] OECD (2021), Labour force participation rate (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/8a801325-en (accessed on 10 November 2021).

[29] OECD (2021), Life expectancy at birth, https://data.oecd.org/healthstat/life-expectancy-at-birth.htm.

[13] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[20] OECD (2021), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/97a5bbfe-en.

[30] OECD (2021), Poverty rate, https://data.oecd.org/inequality/poverty-rate.htm.

[14] OECD (2021), Recent trends in the Estonian labour market, Improving the Provision of Active Labour Market Policies in Estonia, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bf4a7892-en.

[35] OECD (2021), Taxing Wages 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/83a87978-en.

[23] OECD (2021), The Missing Entrepreneurs 2021: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship and Self-Employment, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/71b7a9bb-en.

[43] OECD (2021), Towards Improved Retirement Savings Outcomes for Women, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/pensions/towards-improved-retirement-savings-outcomes-for-women-f7b48808-en.htm.

[24] OECD (2020), “Boosting social entrepreneurship and social enterprise development in Estonia: In-depth policy review”, OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2020/02, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8eab0aff-en.

[22] OECD (2020), Inclusive Entrepreneurship Policies: Country Assessment Notes - Estonia, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/Inclusive-Entrepreneurship-Policies-Country-Assessment-Notes.htm.

[11] OECD (2020), “Women at the core of the fight against COVID-19 crisis”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/553a8269-en.

[36] OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Estonia 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-est-2017-en.

[48] OECD (2016), “The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlz9h56dvq7-en.

[25] OECD (2014), “Estonia: ETNA Microcredit scheme for women entrepreneurs in rural areas”, in The Missing Entrepreneurs 2014: Policies for Inclusive Entrepreneurship in Europe, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264213593-21-en.

[44] Piirits, M. (2022), “The Impact of Pension Reforms on Pension Inequality in Estonia: An Analysis with Microsimulation and Typical Agent Models”, Tartu University, forthcoming.

[6] Puur, A. (2000), “Female labour force participation during transition: The case of Estonia”, Estonian Interuniversity Population Research Centre, https://www.popest.ee/file/B44.pdf.

[16] Saar, E., S. Krusell and J. Helemae (2017), “Russian-Speaking Immigrants in Post-Soviet Estonia: Towards Generation Fragmentation or Integration in Estonian Society”, Sociological Research Online, Vol. 22/2, pp. 96-117, https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.4228.

[40] Saar, E. and K. Täht (2006), Late careers and career exits in Estonia, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263187171_Late_careers_and_career_exits_in_Estonia.

[10] Statistics Estonia (2022), RVR03: Migration by year, sex, age group, indicator and type of migration, https://andmed.stat.ee/en/stat/rahvastik__rahvastikusundmused__ranne/RVR03/table/tableViewLayout2.

[18] Statistics Estonia (2021), Work life, https://www.stat.ee/en/find-statistics/statistics-theme/work-life.

[46] Tire, G. (2020), “Estonia: A Positive PISA Experience”, in Improving a Country’s Education, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59031-4_5.

[42] Unt, M., M. Kazjulja and V. Krönström (2020), “Estonia”, in Extended Working Life Policies, Springer, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-40985-2_17.

[17] Vetik, R. (1993), “Ethnic Conflict and Accommodation in Post-Communist Estonia”, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 30/3, pp. 271-280, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343393030003003.

[31] WHO (2020), Life expectancy and Healthy life expectancy, Global Health Observatory data repository, https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.688?lang=en.

Annex 2.A. Additional tables

Net migration to Estonia was middling in the latest data. After 2014, the trend of overall out-migration from Estonia turned and then the country has had positive net migration, meaning that more people arrive to Estonia than leave. Up until 2014, there were slightly more women than men migrating out of Estonia while after 2014, there were slightly more men than women leaving. The proportion of female migrants has changed little in recent years (Statistics Estonia, 2022[10]). Overall, 2.8 per 1 000 people arrived in Estonia in 2020, which is similar to the figure in Norway (2.8) and Germany (2.9). The figure is lower than that in neighbouring Lithuania (7.2). However, the trend in Estonia is notably different compared to that in Latvia. Latvia remains the only OECD country in the EU that has not yet managed to turn the trend of negative net migration, and 1.7 per 1 000 people overall left the country in 2020 (Eurostat, 2022[9]).

Annex Table 2.A.1. Net migration per population is middling in Estonia

Annual net migration per 1 000 inhabitants, 2011‑20

|

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Latvia |

‑9.7 |

‑5.8 |

‑7.0 |

‑4.3 |

‑5.4 |

‑6.2 |

‑4.0 |

‑2.5 |

‑1.8 |

‑1.7 |

|

Denmark |

2.0 |

1.9 |

3.0 |

4.3 |

6.0 |

3.8 |

2.1 |

0.7 |

‑0.9 |

0.6 |

|

Greece |

‑2.9 |

‑6.0 |

‑5.4 |

‑4.4 |

‑4.1 |

1.0 |

0.8 |

1.5 |

3.2 |

0.6 |

|

Slovak Republic |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

|

Hungary |

1.3 |

1.1 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

2.9 |

3.6 |

4.0 |

0.8 |

|

Poland |

‑2.9 |

‑1.5 |

‑1.5 |

‑1.2 |

‑1.1 |

‑0.7 |

‑0.2 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

|

Italy |

5.1 |

4.1 |

3.0 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

2.6 |

1.5 |

|

France |

0.4 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

2.3 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

2.1 |

|

Czech Republic |

‑2.7 |

‑1.1 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

3.7 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

|

Norway |

10.2 |

9.5 |

8.3 |

7.4 |

6.1 |

5.1 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

4.8 |

2.8 |

|

Estonia |

‑1.9 |

‑2.8 |

‑2.0 |

‑0.6 |

1.8 |

0.8 |

4.0 |

5.4 |

4.1 |

2.8 |

|

Germany |

3.0 |

4.4 |

5.4 |

6.9 |

15.2 |

6.0 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

3.7 |

2.9 |

|

Finland |

3.1 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

2.9 |

2.3 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.2 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

|

Sweden |

4.8 |

5.4 |

6.8 |

7.9 |

8.0 |

11.9 |

9.9 |

8.5 |

6.7 |

3.3 |

|

Switzerland |

6.6 |

5.7 |

6.7 |

5.6 |

4.5 |

3.4 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

|

Belgium |

5.7 |

3.2 |

1.6 |

2.6 |

5.1 |

2.8 |

3.3 |

4.3 |

4.1 |

3.7 |

|

Ireland |

‑5.6 |

‑4.5 |

‑2.4 |

0.5 |

2.9 |

4.9 |

3.0 |

9.1 |

4.8 |

3.7 |

|

Portugal |

‑2.3 |

‑3.5 |

‑3.5 |

‑2.9 |

‑1.0 |

‑0.8 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

4.3 |

4.0 |

|

Netherlands |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.0 |

1.9 |

3.2 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

6.2 |

4.6 |

|

Austria |

3.7 |

4.7 |

5.7 |

7.4 |

12.8 |

7.5 |

5.2 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

4.6 |

|

Spain |

‑0.8 |

‑3.0 |

‑5.4 |

‑2.0 |

0.0 |

1.9 |

3.5 |

7.2 |

9.7 |

4.6 |

|

United Kingdom |

3.4 |

2.8 |

3.3 |

4.9 |

5.1 |

3.8 |

4.3 |

3.9 |

4.7 |

|

|

Iceland |

‑2.3 |

0.6 |

6.3 |

4.0 |

4.8 |

13.7 |

25.0 |

21.4 |

14.8 |

7.0 |

|

Lithuania |

‑12.5 |

‑7.1 |

‑5.7 |

‑4.2 |

‑7.7 |

‑10.4 |

‑9.7 |

‑1.2 |

3.9 |

7.2 |

|

Slovenia |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

‑0.2 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

7.2 |

7.8 |

8.8 |

|

Luxembourg |

21.5 |

19.1 |

19.3 |

20.1 |

19.8 |

16.4 |

17.9 |

17.7 |

18.0 |

12.2 |

Notes: Net migration refers to the number of people who migrate into the country less the number of people who migrate out of the country.

Source: Eurostat, Population and social conditions.

The old-age dependency ratio is high and increasing rapidly in Estonia. In 2020, Estonia’s old age dependency ratio (32%) was already 5 percentage points higher than that in the OECD (27%). The path ahead also looks challenging for Estonia with its dependency ratio set to increase faster than those across much of the OECD. Between 2020 and 2060, the dependency ratio is expected to increase by 24 percentage points in Estonia compared with 18 points in the OECD. Despite fast increases, Estonia’s dependency ratio in 2060 (56%) is set to remain below that in its Baltic neighbours Latvia (63%) and Lithuania (63%).

Annex Table 2.A.2. Estonia’s dependency ratio is set to increase rapidly in coming decades

Old age dependency ratio, outturn and projected, 2010‑60

|

|

Outturn |

Projection |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

2010 |

2015 |

2020 |

2025 |

2030 |

2035 |

2040 |

2045 |

2050 |

2055 |

2060 |

|

Korea |

15 |

17 |

22 |

30 |

39 |

49 |

60 |

70 |

79 |

83 |

90 |

|

Japan |

36 |

44 |

48 |

51 |

54 |

58 |

66 |

70 |

73 |

74 |

74 |

|

Latvia |

27 |

30 |

33 |

37 |

42 |

45 |

49 |

53 |

57 |

62 |

63 |

|

Poland |

19 |

22 |

28 |

33 |

36 |

37 |

41 |

46 |

53 |

59 |

63 |

|

Lithuania |

26 |

28 |

31 |

36 |

41 |

47 |

51 |

54 |

57 |

60 |

63 |

|

Portugal |

28 |

31 |

35 |

39 |

44 |

49 |

55 |

60 |

63 |

63 |

62 |

|

Greece |

29 |

33 |

35 |

39 |

42 |

48 |

53 |

59 |

63 |

63 |

62 |

|

Italy |

31 |

34 |

37 |

39 |

44 |

51 |

57 |

61 |

62 |

61 |

60 |

|

Slovak Republic |

17 |

20 |

25 |

29 |

33 |

35 |

40 |

46 |

52 |

57 |

60 |

|

Slovenia |

24 |

27 |

32 |

36 |

40 |

43 |

47 |

52 |

55 |

57 |

56 |

|

Estonia |

26 |

29 |

32 |

35 |

37 |

39 |

42 |

46 |

50 |

54 |

56 |

|

Finland |

26 |

32 |

36 |

40 |

43 |

45 |

46 |

47 |

49 |

52 |

55 |

|

Czech Republic |

22 |

27 |

31 |

33 |

35 |

37 |

41 |

47 |

50 |

53 |

54 |

|

Chile |

14 |

15 |

18 |

21 |

25 |

29 |

33 |

37 |

41 |

47 |

53 |

|

Spain |

25 |

28 |

30 |

33 |

37 |

43 |

49 |

54 |

56 |

55 |

53 |

|

Hungary |

24 |

27 |

31 |

33 |

34 |

36 |

40 |

45 |

48 |

50 |

52 |

|

France |

26 |

30 |

33 |

37 |

40 |

44 |

47 |

48 |

49 |

50 |

50 |

|

Norway |

23 |

25 |

27 |

30 |

34 |

38 |

41 |

43 |

45 |

47 |

50 |

|

Austria |

26 |

27 |

29 |

32 |

37 |

42 |

44 |

45 |

47 |

48 |

50 |

|

Germany |

31 |

32 |

34 |

37 |

43 |

47 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

49 |

50 |

|

Luxembourg |

20 |

21 |

21 |

24 |

27 |

31 |

35 |

39 |

42 |

46 |

49 |

|

Switzerland |

25 |

27 |

28 |

31 |

35 |

38 |

40 |

41 |