This chapter provides an overview of how the Swedish non-financial corporate bond market has developed over the past two decades with respect to size, risk profile and issuer characteristics. It also examines the investor base and provides a description of secondary market activity. The chapter includes a case study of the COVID‑19 pandemic’s effect on the Swedish non-financial corporate bond market, as well as an overview of the real estate sector’s increasing use of corporate bond markets.

The Swedish Corporate Bond Market

2. Mapping the Swedish corporate bond market landscape

Abstract

2.1. Introduction and universe of analysis

This chapter provides an overview of developments in the Swedish corporate bond market. The analysis is limited to bond-issuing companies headquartered in Sweden that are active in the non-financial sector. Companies operating in the real estate sector are not considered part of the non-financial universe (sections 2.2 to 2.8) but are analysed separately in section 2.9. No restrictions are applied with respect to currency or market of issuance unless specifically stated.

2.2. Market size

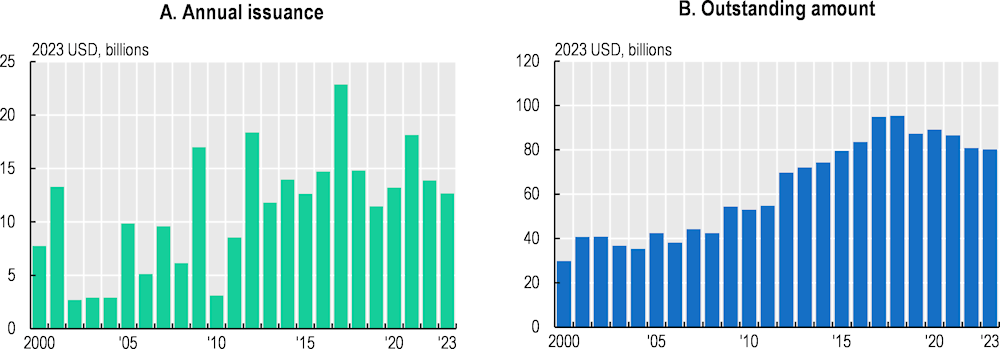

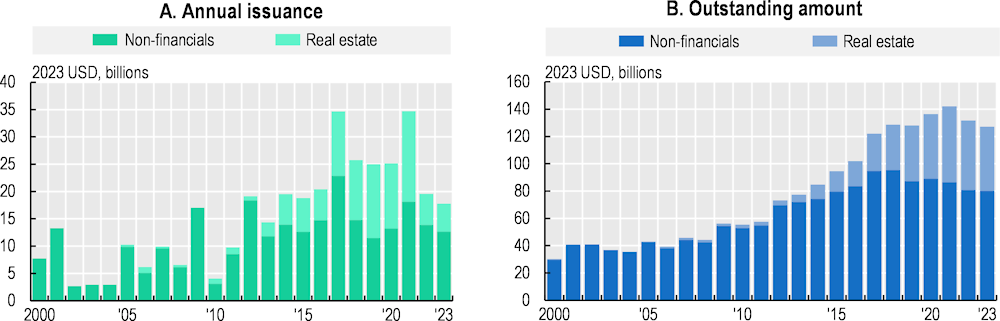

The Swedish corporate bond market for non-financial companies is relatively young and has changed significantly over the past two decades. Between 2000 and 2008, growth was muted and the market was largely characterised by a small number of large companies within a limited number of industries. However, in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, notably as access to bank lending diminished, the market began expanding. In real terms, issuance by non-financial companies averaged USD 6.7 billion annually between 2000 and 2008. This more than doubled to USD 13.8 billion in the period between 2009 and 2023 (Figure 2.1, Panel A).

As a comparison, the average total annual amounts of equity (primary and secondary offerings) issued by non-financial companies during these periods were USD 7.4 billion and USD 9.4 billion, respectively. In other words, bond issuance surpassed equity issuance. This is notable given the prevalence of equity financing in Sweden, which has one of the most active equity markets in the EU, both with respect to size and the number of listed companies (Eurofi, 2023[20]). However, the size difference between corporate bond and equity markets remains much smaller in Sweden than in larger markets. For example, since 2009, average annual bond issuance in Sweden has been 1.5 times larger than total average annual equity issuance, compared to 5.9 times in the United States and 3.7 in the EU. The fact that bond issuance has overtaken equity issuance in size is nevertheless an illustration of the pace at which the Swedish market is growing. At the end of 2023, the total amount of outstanding non-financial corporate bonds was USD 80 billion, almost twice the amount in 2008 (Figure 2.1, Panel B).

Figure 2.1. The size of the Swedish non-financial corporate bond market

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

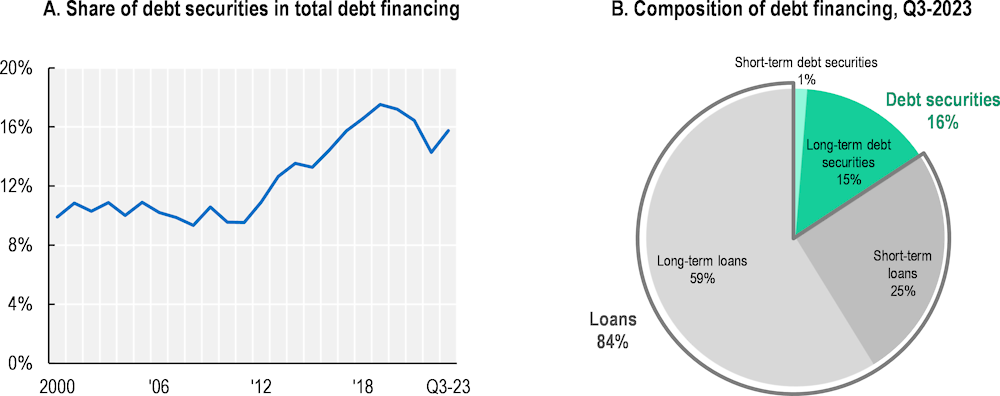

As a consequence, debt securities, notably corporate bonds, have increased as a share of total corporate debt financing, meaning that market-based debt financing has grown faster than bank loans. Having remained remarkably stable between 9% and 11% from 2000 to 2012, the share of debt securities in total debt financing had grown to 16% in the second quarter of 2023, the vast majority of which is made up by long-term securities (Figure 2.2, Panel A). The share of debt securities in total debt financing is slightly higher than in the euro area, but lower than in other regions where market-based financing is more developed (see further discussion under Chapter 3). Sweden remains a largely bank-dependent economy, with loans representing 84% of non-financial companies’ aggregate debt financing (Figure 2.2, Panel B).

Figure 2.2. Swedish non-financial companies’ use of debt securities and bank loans

Note: Panel A shows the share of debt securities (long and short-term) in total debt financing (the sum of total loans and total debt securities) for non-financial companies. Securities with original maturities below one year are classified as short-term.

Source: ECB.

2.3. Credit risk profile

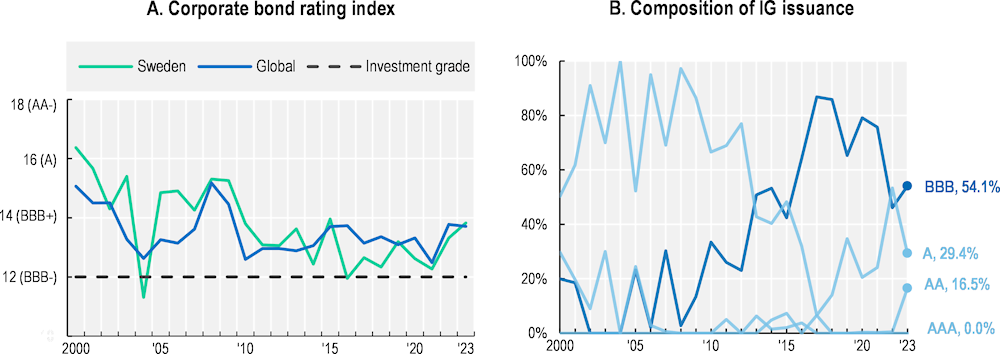

Looking at the risk profile of the Swedish corporate bond market reveals several notable trends. Firstly, as seen in Panel A of Figure 2.3, the credit quality of Swedish bond issuances has followed the global decreasing trend in credit quality starting, in 2000 and more notably since 2009 when market growth accelerated. For bonds issued in 2023, the average value‑weighted rating was just below BBB+. This is an increase of a full notch since 2021, when the average rating was just above BBB-, the lowest investment grade rating. This increase reflects more restrictive financial conditions following the increase in interest rates during 2022 and 2023.

To some extent, the longer-term decrease in credit quality is driven by investors accepting higher risk in search for higher yields in the general low-yield environment that prevailed following the extensive expansionary monetary policies implemented by several central banks around the world in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, and more recently in response to the euro and COVID‑19 crises. Notably, the Swedish Riksbank was the first central bank to bring its main repurchase rate into negative territory in early 2015.

Another notable development is the prevalence of BBB rated bonds in the composition of investment grade issuance. In 2023, BBB rated bonds accounted for 54% of total issuance, up from an average of less than 11% over the period 2000‑08. In 2021, BBB issuance represented 76% of total rated issuance (Figure 2.3, Panel B). Over time, by far the largest corresponding decrease has taken place in the A grade category. This increase in the weight of the lowest credit quality category within investment grade issuance is also in line with global trends.

Figure 2.3. Credit ratings of Swedish non-financial bonds

Note: Refers to ratings by S&P, Moody’s and Fitch. The index shown in Panel A is constructed by assigning a score of 1 to a bond if it has the lowest credit rating and 21 if it has the highest rating. The corporate bond rating index is then calculated by averaging individual bond scores, weighted by issue amounts.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

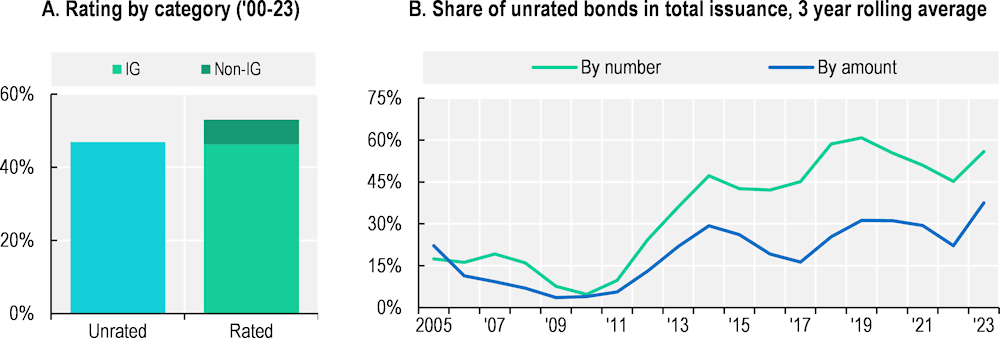

A significant portion of Swedish bonds are unrated. Of the total number of issues between 2000 and 2023, 48% did not have a rating by one of the three major international rating agencies. Including ratings from the local credit rating agency, Nordic Credit Rating, only makes a marginal difference, bringing the unrated share down to 47%. Of the rated bonds, 87% were investment grade (Figure 2.4, Panel A). It is worth noting that when looking at amounts rather than number of bonds, the share of unrated bonds is significantly lower at 21%. This is to be expected, since larger issuances typically target a broader, often international investor base that require the bonds they invest in to have credit ratings from the major agencies. As shown in Panel B of Figure 2.4, the share of unrated bonds has increased rather significantly over time, notably since 2010. This is in line with the expansion of the market to smaller companies that are less likely to obtain a credit rating (see Figure 2.11 and related discussion). In 2023, the median issuer with a credit rating in Sweden was well above twice as big as the median unrated issuer.

According to the Swedish Riksbank (2014[21]), in 2014 about two‑thirds of the unrated bonds issued in Sweden were categorised as investment grade by domestic banks in their internal ratings. However, this practice of domestic banks supplying so‑called “shadow ratings” has since been discontinued, after the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) found it to be in breach of the Credit Rating Agencies Regulation (CRAR) and consequently fined five major Nordic banks (ESMA, 2018[7]).

Having a credit rating from one of the main international rating agencies is often a prerequisite for accessing capital from many types of institutional investors, especially foreign, who use credit ratings as an aggregate risk management tool for large portfolios and do not necessarily have business models that allow for detailed due diligence of individual bonds. Certain institutional investors, notably pension funds and insurance companies, are also constrained by regulation to holdings above a certain rating.

One reason for the high proportion of unrated bonds in Sweden is likely the fact that obtaining a rating from the major international rating agencies involves significant costs that may be prohibitive for smaller issuers. For example, S&P Global Ratings has disclosed that credit ratings for most transactions involve a fee of up to 7.1 basis points of the total transaction value, with a floor of USD 110 000, meaning that any issue below USD 155 million will carry a cost above 7.1 basis points.1 For a bond issue of USD 71 million – the median size in Sweden in 2023 – the cost would be 15.5 basis points. In addition, all else equal, a larger company size is associated with a higher rating, possibly further discouraging smaller issuers from obtaining ratings. Scale (e.g. total sales) is one of the five factors Moody’s uses to assign its ratings (OECD, 2021[6]).

In 2016, rating company Nordic Credit Rating was set up by large banks and institutions in the region to lower the threshold for small and mid-sized issuers to obtain a credit rating. Recognising the existence of the dynamics favouring larger issuers as well as the need for an active market for research on creditworthiness of smaller companies, some countries have implemented systems where ratings are provided nationally at reduced cost. This is done with the understanding that smaller size issues are typically not intended for large, international investors who would require a rating from (at least) one of the established agencies, but that it is beneficial to have easily accessible information that can help investors gauge default risks. For example, in France the Banque de France provides a form of credit score for individual firms for a fee through the FIBEN system (OECD, 2020[22]). In Norway, self‑regulation has recently been introduced to incentivise the use of ratings by so called “bond funds” (VVF, 2023[23]).

Figure 2.4. Rated and unrated issues, Swedish non-financial corporate bonds

Note: Includes ratings from S&P, Moody’s, Fitch as well as local agency Nordic Credit Rating. Panel A shows shares by number of bonds.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, Nordic Credit Rating, see Annex for details.

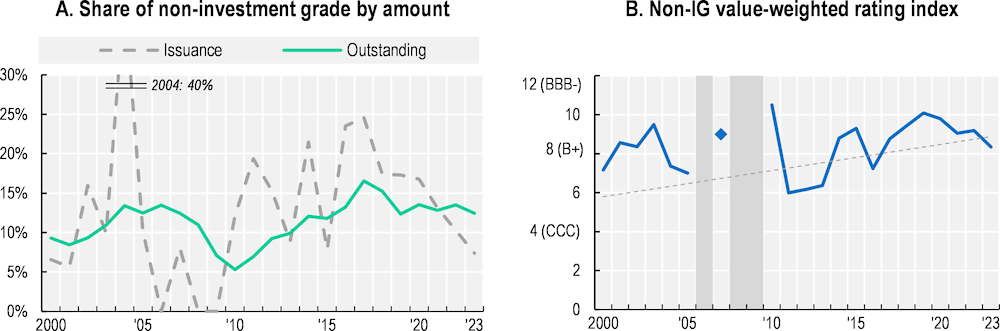

At the end of 2023, the non-investment grade segment of the Swedish non-financial bond market made up 12.4% of total outstanding amounts, including unrated bonds. This is roughly in line with the share of outstanding non-investment grade bonds globally, which is 13.6%. The Swedish share has increased somewhat as the market has grown. The lowest share was recorded in 2010 at 5.3%, after three years without non‑investment grade issuance in 2006, 2008 and 2009. It peaked at 16.5% in 2017 (Figure 2.5, Panel A).

While the outstanding share of non-investment grade bonds has increased since 2010, this only partially explains the downward trend in the rating index shown in Panel A of Figure 2.3. This indicates that the main driver of lower ratings is a change in the composition of investment grade issuance, as shown in Panel B of Figure 2.3. Notably, the value‑weighted average rating in the non-investment grade category has not been declining (Figure 2.5, Panel B). If anything, it has shown a slight upward trend, although with relatively significant swings over time.

Figure 2.5. The Swedish non-investment grade corporate bond market

Note: Shaded areas in Panel B represent years with no non-investment grade issuance. The index shown in Panel B is constructed by assigning a score of 1 to a bond if it has the lowest credit rating and 21 if it has the highest rating. The corporate bond rating index is then calculated by averaging individual bond scores for non-investment grade issuers (< 12), weighted by issue amounts.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

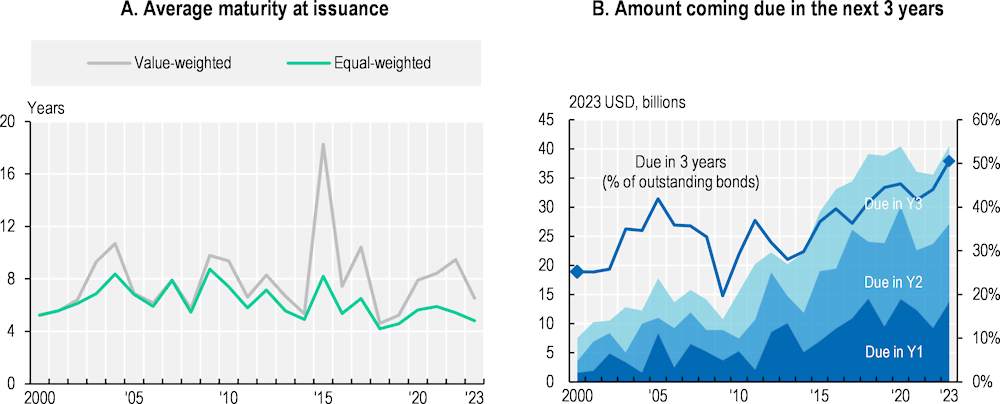

An important aspect of the risk level of a bond market is the aggregate maturity and repayment profile. Equal-weighted average maturity at issuance has been decreasing over time. Between 2000‑07 the average maturity was 6.6 years, compared to 6.0 years between 2008-23 and 4.8 years in 2023. The median maturity is slightly lower at 4.2 years at the end of 2023, and lower still when considering only bonds denominated in the domestic currency, for which it was 4.0 years.

Since 2008, Swedish investment grade bond maturities have on average been 2 years longer than those of non‑investment grade bonds, a difference which is smaller than the global one during the same period (4.1 years). Since the ratio between the average maturity of investment grade and non-investment grade bonds in Sweden is similar to the global ratio, it follows that the divergence is driven by generally shorter average maturities in Sweden.

When companies have large amounts of debt coming due within a short time period, they may be exposed to refinancing risk, especially when financial conditions are significantly tighter than when the existing debt stock was issued. If a large share of total outstanding bonds is coming due under such conditions, it may amplify existing shocks with detrimental effects on the real economy. Panel B of Figure 2.6 illustrates the bond debt coming due within the next three years and its share of the total outstanding bond debt. The amount due in the next three years has increased substantially since the 2008 financial crisis, almost quadrupling since 2009. It has also increased as a share of total outstanding bonds, although the increase is less pronounced than for absolute amounts. In 2023, it stood at 51%. It is worth noting that the share was at its lowest in 2009 (at 20%), when crisis-induced risk aversion likely drove investors towards safer issuers who were able to issue at longer maturities. The Swedish non-investment grade market was effectively frozen in both 2008 and 2009, with zero issuance in both years.

Figure 2.6. Maturity and repayment profile of Swedish non-financial bonds

Note: The peak in 2015 in Panel A is driven by a set of four large bonds (between USD 344 million to USD 1.05 billion) issued by state‑owned power company Vattenfall with maturities between 62 and 63 years.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

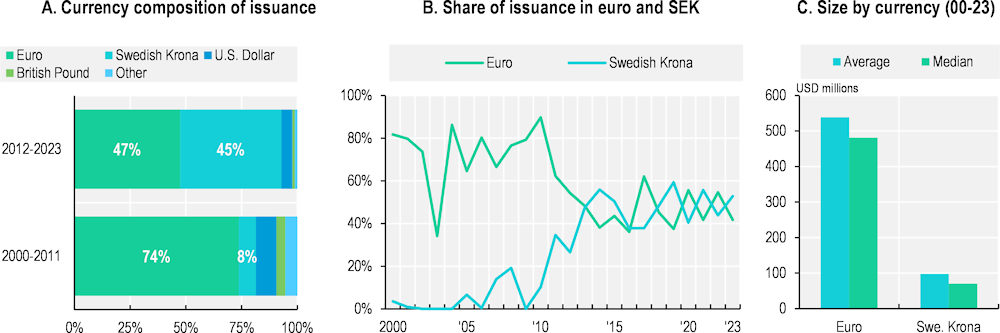

Between 2000 and 2023, bonds denominated in euros made up 56% of total Swedish non-financial issuance, followed by the Swedish Krona (SEK) at 33%. Most of the remainder was issued in US dollars (Figure 2.7, Panel A). Until 2010, issuance in SEK was minimal (with the exception of 2007 and 2008) and the market was dominated by euro denominated bonds.2 However, as the market expanded and became accessible to a larger number of companies around 2010, the share of domestic currency bonds increased sharply. Between 2010 and 2023, the share of SEK-denominated bonds in total issuance averaged 45%, compared to 8% in the period from 2000 to 2011. In 2023, the share was 53% (Panel B). Panel C shows the average and median size of bonds issued in the two different currencies, clearly illustrating how bonds (and issuers) issued to the international markets (proxied by euro denomination) and the domestic ones (in SEK) differ in character. The average (median) size of Swedish corporate bonds issued in euros between 2000 and 2023 was USD 539 (481) million, more than five times the amount in SEK, which was USD 98 (70) million. With this in mind, the increasing share of SEK issuance shown in Panel B is another indicator of the growing access of smaller, domestic companies to the Swedish bond market.

Figure 2.7. Currency composition of Swedish non-financial bond issuance

Note: Panels A and B both show shares of the total amount issued.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

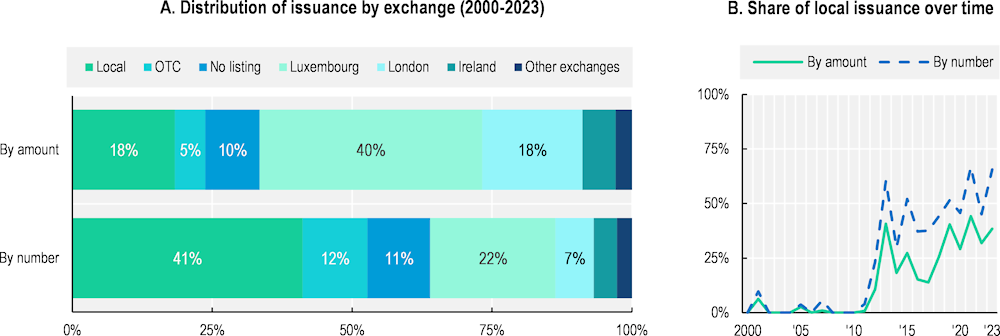

Data on the exchanges used for listings are consistent with this development. Whereas international exchanges are dominant when looking at total issuance amounts between 2000 to 2023, local exchanges is the largest category when looking at number of issues. Specifically, Luxembourg is the most important foreign exchange, with 40% of the listed amount during the last two decades, followed by London at 18%, equal to the share of Swedish exchanges. A relatively sizeable share of bonds is classified as unlisted (10%) and over-the‑counter (5%). Non-investment grade bonds are more commonly unlisted than investment grade ones (18% versus 7% by amount from 2000 to 2023). Looking at the number of issues, 41% are listed on domestic exchanges (Figure 2.8, Panel A).

Also in line with the growing prevalence of domestic currency denominated bonds shown above, Panel B of Figure 2.8 shows how the share of local exchange issuance has increased over time. Similar to the development in SEK-denominated issuance, the share of locally listed bonds was effectively zero up until 2011, after which it has grown substantially, peaking at 44% in 2021. It bears mentioning that while most Swedish corporate bonds are listed on an exchange, trading is effectively exclusively done OTC (see section 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Issuance by exchange

Note: The following exchanges are included in the Local category: Stockholm/Nasdaq Nordic and NGM Nordic MTF.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

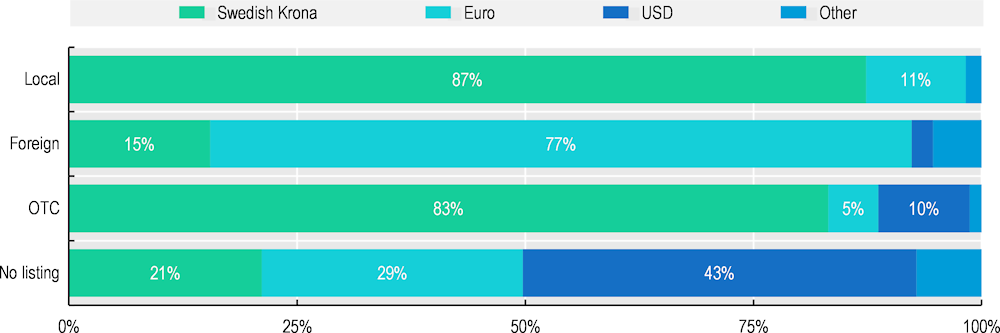

Looking at exchanges and currency denomination in conjunction shows more clearly the types of bonds that are issued in different markets. Figure 2.9 shows the significant difference in currency composition by exchange. On local exchanges, 87% of all bonds issued (by amount) between 2000 and 2023 were denominated in SEK, with euro-denominated issues making up the clear majority of the remaining 11%. The domestic currency share is also substantial for bonds classified as OTC, at 83%. Contrarily, on foreign exchanges euro-denominated bonds represent as much as 77% of issuance and the Swedish krona 15%. For bonds without listings the US dollar is the single largest currency, representing 43% of issuance.3

Figure 2.9. Currency distribution of issuance by exchange, 2000‑23

Note: The following exchanges are included in the Local category: Stockholm/Nasdaq Nordic and NGM Nordic MTF.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

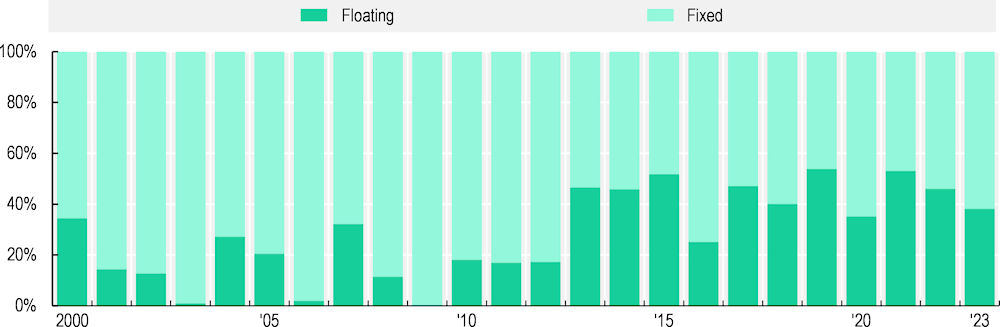

Turning to interest rate structures, the share of floating-rate bonds in total amounts issued in Sweden has increased significantly in the past decade, from 18% in 2010 to 38% in 2023 (Figure 2.10). This is substantially higher than in other advanced economies, where the aggregate share of floating rate issuance for non-financial companies since 2008 has only been 6% (OECD, 2024[24]). Issuing floating rate bonds can help increase investor demand, and thereby liquidity, for a security since it offers investors positive exposure to higher interest rates if broader market conditions change, limiting the risk of being locked into lower than currently prevailing rates. However, from an issuer perspective it also increases the exposure to rate hikes which would lead to increased debt servicing costs. These risks can be addressed with hedging instruments, but these carry additional costs for the issuer. From a broader economic perspective, a high share of (unhedged) floating rate debt can also have financial stability implications. If debt servicing costs become unsustainable for a large enough number of companies, it may put upward pressure on default levels.

Figure 2.10. Split between floating and fixed rate bonds over time

Note: By amount issued.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

2.4. Issuer characteristics

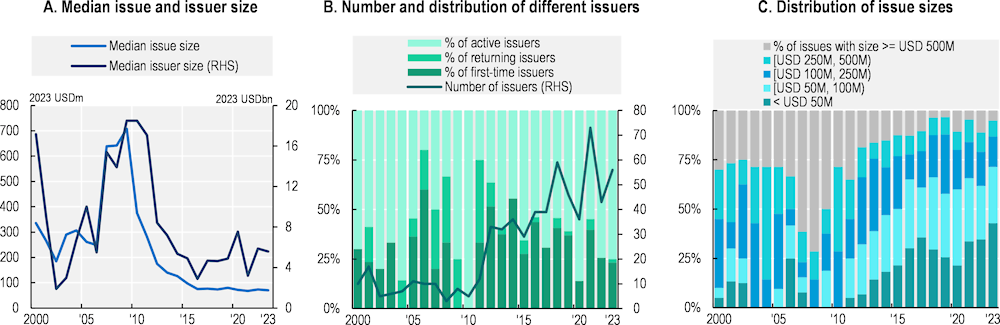

In addition to market-level developments, it is useful to consider changes at the issuer level. Figure 2.11 below provides an overview of the composition of issuers on the Swedish bond market during the past two decades.

Before the global financial crisis, the corporate bond market in Sweden was clearly dominated by large companies issuing significant amounts. As with many of the trends shown thus far, there is a clear change after the 2008 financial crisis, and in particular after 2010. As shown in Panel A, both the median size of issuers and issues grew between early the 2000s and 2010. After that, both issuer and issue sizes have been declining. Panel B classifies issuers into three groups depending on their previous experience with bond markets: first-time issuers are issuers that have never issued a bond before; returning issuers has previously issued bonds, but more than five years ago; and active issuers have issued at least one bond within the last five years. Between 2000 and 2010, the average share of active issuers was 63% with first-time issuers representing 23%. On average, there were only eight issuers per year. In sharp contrast, the share of first-time issuers averaged 35% between 2011 and 2023, with an average of 41 issuers annually. In 2020, the number of issuers dropped sharply and the market was dominated by active issuers. In 2021 a record 73 companies issued bonds. However, similar to the dynamics seen in 2020, this number fell sharply in 2022 as market conditions grew less accommodative, with active issuers once more dominating.

Panel C shows the corresponding change in the distribution of issue sizes. Similarly, up until 2009 the market was clearly dominated by large companies. Issues larger than USD 500 million represented as much as a third of issues between 2000 and 2010. In 2007 it was as high as 62%. The two smaller categories below USD 100 million made up no more than 7% on average during this period. The dominance of large companies was particularly evident during the 2008 financial crisis when only very large and creditworthy Swedish companies had access to this type of market-based financing (Panel A). This led to a remarkably high median issue size, which peaked at USD 708 million in 2009 – higher than recorded in either Europe or the United States during the same period (OECD, 2021[6]). This dropped sharply after 2010, reaching USD 71 million in 2023, a decrease of around 80% compared to roughly a decade earlier. In the same year, issues below USD 100 million made up 71% of total issuance while the largest category (above USD 500 million) only represented 5%.

Figure 2.11. Characteristics of issuers/issues on the Swedish non-financial corporate bond market

Note: Issuer size is defined as total assets. A company is defined as a first-time issuer if its bond issue in a given year is its first issue since the start of the data series (January 1980). A “returning issuer” is a company which made its last bond issue more than five years ago. If the company issued bonds in at least one of the past five years, it is defined as an “active issuer”.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

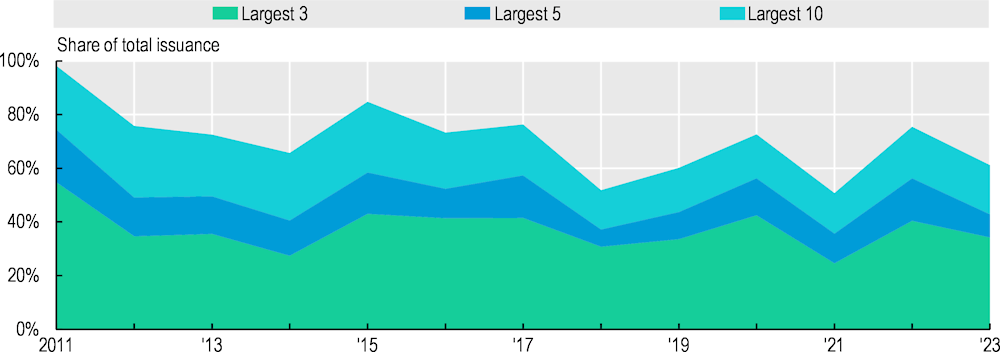

The increase in the number of issuers and general broadening of the market is also reflected in the concentration of issuers. Figure 2.12 below shows the share of the top three, five and ten largest issuers in total issuance over time. The share of the ten largest issuers has fallen sharply over the past decade, from an average of 78% in the period from 2011-2016 to 64% in the period from 2017-2023, with the three largest issuers’ share falling from 39% to 35% in the same period. Notably, as an effect of tightening financial conditions, in both 2020 and 2022 the share of the ten largest issuers increased to 73% and 75% respectively, similar to the levels seen back in 2012. This follows from the sharp decrease in the number of issuers in these years, as shown in Figure 2.11. Within the investment grade category of the Swedish bond market, in 2020 only one of 132 issues came from a new issuer (Nordic Trustee, 2020[25]).

Figure 2.12. Largest issuers’ share in total issuance

Note: 2011 is used as the starting point since the average number of annual issuers prior to that was no more than 8. In the period from 2011 to 2022, the annual average number of issuers was 40, with a peak of 73 issuers in 2021.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

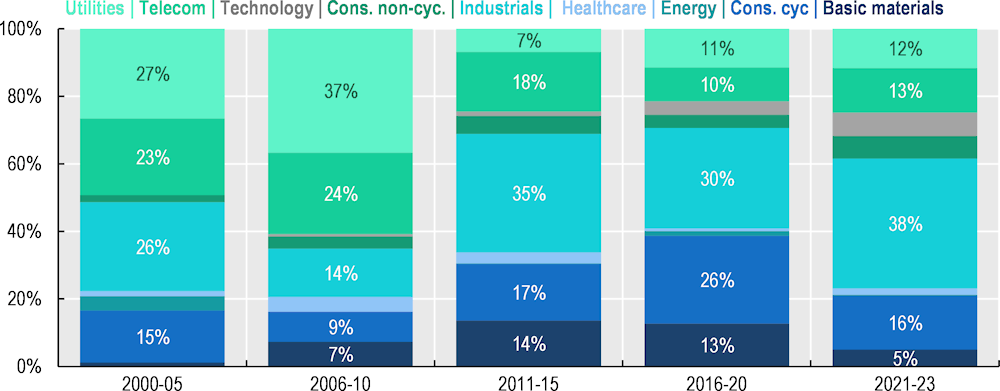

As the market has grown, its industry composition has changed. However, despite significant variation between years, certain industries have remained dominant. Notably, industrial companies make up a substantial share of the total amount issued through corporate bonds throughout the analysed period, averaging 27% of annual issuance from 2000 to 2023, and reaching as much as 38% during the last three years. Consumer cyclicals, utility and telecom are also large issuers (Figure 2.13).

It should be noted that bonds issued by real estate companies are not included here. A separate section (2.9) is devoted to an analysis of the real estate sector. More generally, it bears mentioning that the financial industry, which is not considered in this report, represents a significant share of the Swedish bond market, accounting for as much as 73% of total issuance in 2023.

Figure 2.13. Industry composition of the Swedish non-financial bond market

Note: Shares in total issuance for each period. Real estate companies are not considered in the above graph. Refer to section 2.9 for an analysis including the real estate industry.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

2.5. Corporate bond investors

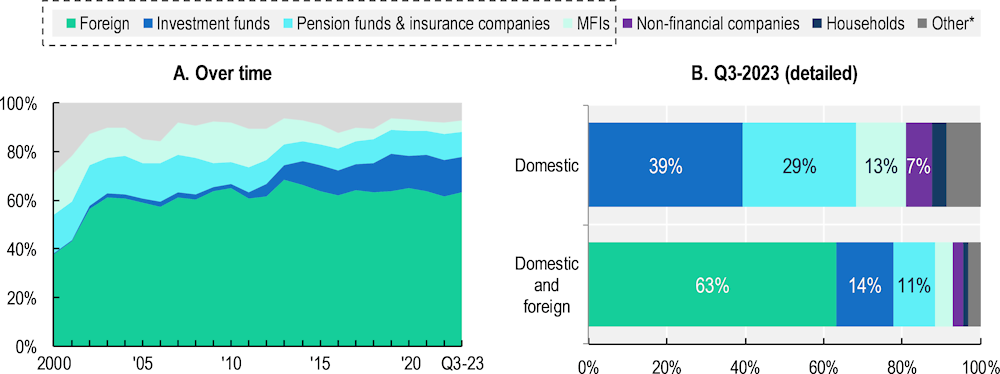

Foreign investors are the largest owners of Swedish non-financial corporate bonds. By the end of Q3-2023 they held 63% of the total outstanding amount. This share has remained quite stable since 2003. The composition of domestic ownership, however, has changed. An important development is the growth of investment funds as owners since about 2012. In 2011, they held about 2% of total outstanding amounts, a figure that had grown to 14% by Q3-2023 (Figure 2.14, Panel A). Their portion of domestic ownership represents 39%, compared to 6% in 2011 (Panel B). The use of aggregate statistics does not allow for a breakdown of the foreign investor category. However, this is also likely to include a substantial amount of investment funds (Becker et al., 2020[26]).

Monetary financial institutions (MFIs, e.g. banks, money market funds and other credit institutions) represent 13% of domestic ownership, a decrease from 46% in 2009. This is significant and reflects the overhaul of the regulatory landscape, in particular for banks, after the 2008 financial crisis, notably the new Basel accords. Higher capital and liquidity requirements for banks have made it increasingly capital-intensive to hold inventories of corporate bonds. This has led to a reduction in proprietary inventories and a decrease in dealer intermediation (FSB, 2021[27]). Non-financial companies themselves represent 7% of domestic ownership of non-financial bonds. Direct retail (household) participation in bond markets is very low, but retail investors are still exposed to the market through e.g. investment and pension funds.

Figure 2.14. Ownership structure of outstanding Swedish non-financial bonds

Note: In Panel B, the “Other” category includes: the Swedish central bank, public administration and other financial intermediaries (original classification in raw data). In Panel A, the “Other” category includes all of these, plus those shown in Panel B but not in Panel A (non‑financial companies and households). Data refer only to corporate bonds (not short-term securities). All values are as of year-end except 2023.

Source: Financial Accounts from Statistics Sweden (SCB).

2.6. Covenant protection

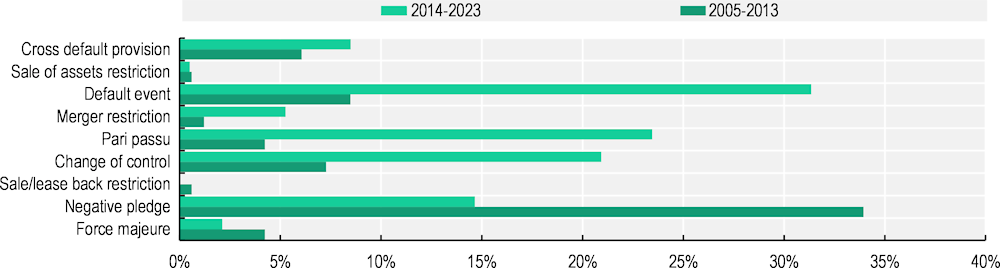

Covenants are constraints placed on an issuer and are stipulated in the bond indenture (contract) at the time of issuance. They are bondholders’ main corporate governance tool and serve to ensure that issuers do not engage in activities that would reduce creditors’ claims or reduce the probability that they are repaid. A breach of covenant will give the bondholders certain legal remedies specified in the indenture, often to accelerate the bonds. Previous OECD analysis (2021[6]) has shown a clear decrease in covenant protection over time for non‑investment grade bonds issued in the United States.

The availability of covenant data for Swedish non-financial bonds through commercial databases is very limited, making it difficult to provide an assessment of developments over time. Based on available data, Figure 2.15 shows how the prevalence of certain covenants in Swedish bond indentures has changed over time, by comparing two nine-year periods. While incomplete, certain trends are visible. For example, the prevalence of negative pledge covenants, preventing issuers from using encumbered assets as collateral for new borrowing (which would dilute the existing creditors’ protection), has decreased markedly over time. Contrarily, change of control covenants – under which a material change in a corporate ownership (definitions may vary) would trigger an obligation to repay the outstanding debt – have become much more common. The same is true for pari passu covenants, which are meant to guarantee that existing creditors are covered by potential additional guarantees the issuer offers to creditors in future borrowing. However, it should be noted that there are substantial differences in the prevalence of different covenants between consecutive years, making it difficult to determine the exact trends. Several market participants have suggested the commercially available data do not reflect their understanding of market trends, noting that e.g. negative pledge and cross default provisions are present in the vast majority of issues. These data can thus be interpreted primarily as an indication of a lack of readily available information.

Figure 2.15. Prevalence of different covenants in Swedish non-financial bond indentures

Note: There are significant data availability restrictions for covenants on Swedish non-financial bonds. This figure should be interpreted considering this limitation. It is based on 1 171 bonds issued by Swedish non-financial companies between 2000 and 2023 with covenant indicators available. Only covenants that are included in at least one bond indenture are displayed.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

2.7. Investment banks and market structure

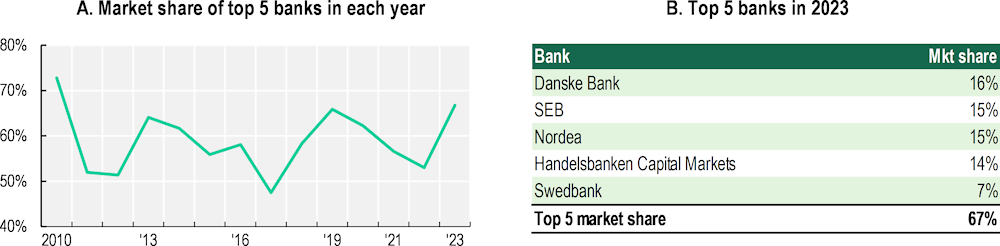

Investment banks play important roles in corporate bond markets, providing underwriting and advisory services. Their services are related to e.g. origination, distribution, risk bearing and certification, as well as advice on pricing, timing of issuance and preparation of relevant documentation. As a general trend, the market concentration of investment banks underwriting non-financial bonds in Sweden has decreased somewhat in the past decade, although the trajectory has been uneven. In 2023, the top five banks had a market share of 67%, compared to 73% in 2010 (Figure 2.16, Panel A). In 2023, all of the top five banks by market share were Swedish or Nordic (Panel B). This is a relatively recent phenomenon. While local banks were always relatively high up in the league tables, up until 2017 the top five always included, and was often dominated by, foreign banks, notably from the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and France. This increase in the share of local investment banks can also be observed in other regions, notably in a number of Asian jurisdictions (OECD, 2019[28]).

Figure 2.16. Composition of underwriters of non-financial bonds

Note: Ranked based on gross proceeds. Panel A shows the share of the top five banks in any given year. However, the composition of the top five differs over time, meaning there can be changes in which banks are included.

Source: LSEG.

When a bond is issued, the issuer normally assigns an independent trustee to supervise the implementation of the bond indenture (contract), in Sweden called an agent. The role of the agent, typically a bank or a specialised institution, is to ensure the contract is followed, including to review instances of covenant breaches, and to handle communication between bondholders and the issuer, as well as to manage bondholder meetings, when held.4 In terms of specialised agent institutions, the Swedish market is dominated by two main players, Nordic Trustee and Intertrust, and by the former in particular. In many markets, the agent/trustee often also plays the role of paying agent, handling collection and disbursements of principal and coupon payments. This is also the case in Nordic markets such as Norway. In Sweden, however, there are no paying agents. Instead, disbursements to bondholders are typically handled by the central securities depository, generally Euroclear (which only provides settlements in euros and Swedish krona). It also bears mentioning that the role of the agent is not specifically regulated, which is the case in, for instance, Finland, Denmark and Norway, as well as in the United States and the United Kingdom through fiduciary duties.5

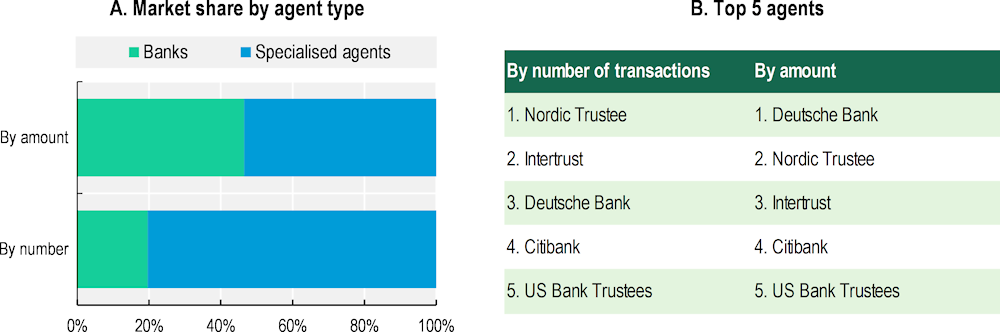

Based on bond issues for which agent information were available between 2012–2023, Figure 2.17 provides an overview of agents active in the Swedish market. By number of transactions, specialised and independent agents – notably Nordic Trustee – dominate the market. Looking at transaction amounts, banks supplying agent services are more prevalent, due to the larger average size of investment grade bonds for which banks more often play the role of agent.

Figure 2.17. Agents on the Swedish bond market, 2012-2023

Note: Based on 356 deals by non-financial companies (excluding the real estate sector) domiciled in Sweden between 2012-2023 for which agent information is available. Cases where the agent was not defined (labelled "Other Trustees") have been excluded.

Source: Nordic Trustee.

2.8. Secondary market liquidity

A liquid secondary market is an important aspect of all market-based financing, facilitating efficient price discovery and enabling investors to enter and exit at any given time, thus also supporting the primary market.

Generally, liquidity is significantly lower on corporate bond markets than on equity markets. Partly, this has to do with the nature of the instrument. For many investors, bonds serve the purpose of long-term liability matching, making it a suitable instrument for institutional investors with long-term portfolio structures. This reduces liquidity, since the largest investor categories are not liquidity suppliers but rather liquidity takers through buy-and-hold strategies. Trading in corporate bonds is typically concentrated in a short period after a bond is issued, following which it drops significantly. Evidence from the US market suggests that most trading takes place in the first 90 days after issuance (Mizrach, 2015[29]). Moreover, the vast majority of outstanding bonds do not trade on any given day. Even for the most traded bonds, the number of trades per day is limited (Çelik, Demirtaş and Isaksson, 2015[30]).

Low liquidity also has to do with trading mechanisms. As opposed to equities, bonds are typically traded in large increments. For example, in the United States the average bond trade size from 2014‑16 was USD 1.2 million. This is compared to an estimated USD 3 000 to 5 000 for equities, less than 0.5% of the size of an average bond trade (Bessembinder, Spatt and Venkataraman, 2020[31]). Similarly, in 2022 the average corporate bond trade size in the secondary market in the EU and UK was EUR 829 000 (ICMA, 2022[32]). This is because most bond markets target large institutional investors, who trade in large minimum sizes. The retail component of the market (at least for direct investments) is typically small. In addition, electronic trading, although increasing, makes up a relatively small part of the market. Phone‑based negotiations remain dominant, in particular for larger bonds, in sharp contrast to equity markets where electronic trading is ubiquitous (FSB, 2021[27]).

Finally, bond market trading has historically been dominated by dealer intermediation by banks, which therefore play an important part in creating liquidity. In 2014, 95% of secondary market trading in Sweden was made up by trading between banks and their customers (Riksbanken, 2014[21]). However, in many places the growth in bond dealer balance sheets has not matched the growth of the corporate bond market. In addition, partly following more stringent regulation in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis as well as increased risk aversion, banks hold smaller inventories of bonds and have reduced their activities as market makers, further reducing liquidity. Riskless principal trading – where the dealer finds both a buyer and a seller before going ahead with a trade – is now a more common business model than regular principal trading (FSB, 2021[27]).

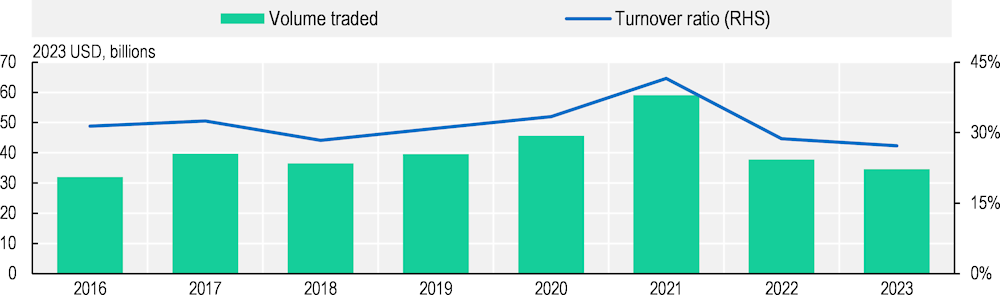

In recent years, the annual volume traded on the Swedish market has slightly outpaced the growth of the market more broadly. Figure 2.18 provides an overview of annual volumes of Swedish non-financial corporate bonds traded on the secondary market and the turnover ratio (measured as annual traded volumes as a share of the outstanding amount at the end of the year). Trading volumes generally increased up until 2021, after which there has been a notable decrease. The Swedish turnover ratio is lower than the European aggregate. In the European Economic Area (excluding the United Kingdom), the turnover ratio in 2020 was 46%, compared to an average of 32% in Sweden from 2019-23 (ESMA, 2021[33]). It should be noted, however, that the Swedish Riksbank’s statistics on corporate bond turnover refers only to bonds denominated in Swedish crowns. This may understate the aggregate market liquidity, given the significantly larger size of the average Swedish foreign currency denominated bond (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 2.18. Turnover in the secondary corporate bond market

Note: Refers to SEK-denominated non-financial corporate bonds. The turnover ratio is calculated as the annual traded volume as a share of the outstanding amount of corporate bonds at the end of the year. See endnotes for commentary on data used in this figure.

Source: Sveriges Riksbank (SELMA Statistics), OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG.

According to Wollert (2020[13]), a lack of transparency in pricing and trading has led to unreliable pricing in the Swedish market. Analysis by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority has shown that part of this reduction in transparency has been a result of implementing the European Union’s directive MiFID II and MiFIR in 2018. Prior to its implementation all bond trades, with the exception of trades exceeding SEK 50 million, had to be disclosed no later than 09.00 (AM) the following day. MIFiD II and MiFIR have, on the face of it, more stringent disclosure requirements, mandating such disclosure both pre‑trade (orders) and post-trade (transactions) effectively in real time. For pre‑trade disclosure, the main rule states that buy and sell bids as well as order depth should be disclosed continuously by market operators and investment firms operating a trading venue during market hours.6 However, due to waivers included in the directive, all investment firms trading in Swedish bonds are exempt from pre‑trade disclosure (it should be noted that pre‑trade transparency was very low also prior to the implementation of MiFIR). When it comes to post-trade disclosure, MiFIR lists three conditions under which disclosure of non-equity transactions may be deferred. They apply to transactions that are: 1) larger than normal market size; 2) related to instruments for which there is no liquid market; or 3) above an instrument-specific size. For trades subject to deferrals based on these criteria, information is to be disclosed at latest 19:00 (7:00 PM) the second working day after the trade. In practice, since only a handful of Swedish bonds are considered liquid under this regulation, essentially all trades are eligible for deferrals. In August 2019, only one Swedish ISIN bond was considered liquid. The effect of this has been reduced transparency on the Swedish bond markets. According to a survey of market participants, well above 60% find that MiFID II/MiFIR has decreased transparency, with just under 30% saying it is unchanged (Finansinspektionen, 2019[34]).7

The Financial Supervisory Authority’s analysis further shows that the reduced transparency is due to fragmentation in data provision (such as turnover data, which was previously available in one place), caused by the lack of one entity compiling all published information (a “consolidated tape provider” or CTP). However, as part of the MiFIR/D II review, there is now political agreement at the EU level for an EU-wide consolidated tape, which includes post-trade data for bonds (European Commission, 2023[8]).

In line with the objectives of MiFIR/MiFID II, trading on regulated venues has increased. Before their implementation in 2018, effectively all Swedish corporate bonds were traded OTC. By 2019 the OTC trading had fallen to below 40% while trading on regulated venues has increased. Much of this increase refers to systematic internalisers (executing orders against their own books or client orders), but increases can also be seen on trading venues including regulated markets, MTFs and OTFs.8 Data show that in practice, transactions executed by systematic internalisers are published two days after the trade. For transactions executed on an MTF, the delay is normally four weeks or more for all types of bonds, although in Sweden this deferral only applies to sovereign and covered bonds and not for corporate bonds. However, most MTF trades in Swedish corporate bonds are executed on platforms that fall under other EU country regulations. Different jurisdictions apply different waivers, and the Swedish FSA has found discrepancies between the transaction data it receives and the publicly available data, meaning the latter gives an incomplete view of the market (Finansinspektionen, 2019[34]). It remains to be evaluated what the effect of the MiFIR/D II revision will be on market transparency.

In response to their findings, in 2020 the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority tasked the Swedish Securities Markets Association (SSMA) with examining ways to improve transparency. As a result, the mandatory rules set out in MiFID II and MiFIR were complemented by a self‑regulatory recommendation on bond market transparency, which applies voluntarily. The recommendation entails e.g. the daily publication of aggregate transaction information executed on the Swedish market, which is to be made public through a single data provider. Notably, the self-regulatory provisions are more stringent than the mandatory national rules applied prior to the implementation of the EU directive (Swedish Securities Markets Association, 2020[35]). Survey results evaluating the self-regulatory approach indicate that it has had a positive effect on transparency.

It bears mentioning that while increased transparency in bond markets is generally beneficial to liquidity, a balance needs to be struck between transparency and dealer incentives to intermediate. Typically, if a trade leads a dealer to add bonds to its inventory, it will want to resell these bonds in the inter‑dealer market. Forcing dealers to show their hand in terms of inventory may compromise their bargaining position in that market, in turn reducing their incentives to intermediate. This is particularly pertinent for high‑yield, illiquid bonds (Çelik, Demirtaş and Isaksson, 2015[30]). However, it is difficult to establish which way the causality runs. Limited transparency may be required to maintain dealer incentives for markets with low liquidity, but low liquidity may equally be an effect of low transparency.

While corporate bonds are typically traded OTC, in certain markets they trade primarily on-exchange, similar to equities. This model is applied for example in the Israeli and Chilean markets. With respect to the Israeli market, some research has found that these features encourage retail investors9 to participate more actively in corporate bond trading and contribute to increased liquidity. Notably, retail investors account for 8.8% of the double‑sided volume traded in Israel (Abudym and Wohl, 2018[36]). In 2021, the on-exchange traded volume on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE) was USD 56 billion, compared to USD 1 billion off-exchange, meaning more than 98% of the volume traded of corporate bonds took place on-exchange (TASE, 2022[37]). TASE has 24 members, consisting of banks and brokers, who can connect directly to the TASE trading system. An investor, i.e. TASE member clients, can submit orders online and check the status and the order book. Unlike OTC trading, the accessibility and transparency offered by the exchange allows retail investors with small investments to participate in the corporate bond market, which in most countries is accessible only to institutional and qualified investors.

Similarly, in Chile, although the market is only open to qualified investors, corporate bonds trade on the Santiago Stock Exchange (BCS) through two open systems. The first system, called TELERENTA, automatically matches buy and sell orders through a continuous order book, giving priority to the lowest market-clearing price (BCS, 2016[38]). The second system, also operated by the exchange, is a periodic English Auction system. Like in Israel, on‑exchange transactions make up the lion’s share of trading, accounting for 75% of all traded volume in 2022 (BCS[39]).

While on-exchange trading systems may have important benefits in terms of broadened access to the bond market (notably for retail investors) and in terms of reduced spreads, it is not evident that it is beneficial to liquidity (measured as turnover). From 2019 to 2021, the average turnover for corporate bonds on TASE was 49%, similar to the levels in the EEA (excluding the UK) (TASE[40]).

2.8.1. The Swedish corporate bond market during COVID‑19

This subsection provides an overview of the dynamics of the Swedish corporate bond market during the COVID‑19 crisis, including subsequent initiatives to improve market functioning, both from regulators and private sector representatives.

Well-functioning capital markets serve to provide an economy with increased resilience in times of crisis, allowing companies to access financing even as risk aversion increases, typically resulting in contractions in both bank credit and consumer demand, simultaneously increasing the need for financing and decreasing the availability of capital. In 2009, non-financial companies globally issued record amounts of bonds, and the same dynamics played out in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic. The same pattern can be seen for equity markets (secondary public offerings, i.e. already listed companies tapping equity markets, are of particular importance) (OECD, 2021[6]). These developments are indicative of the ability of market-based financing to help economies overcome periods of financial and general economic distress. However, a prerequisite for this is that markets are sufficiently flexible, liquid and deep. When they are not, they offer less resilience in times of crises.

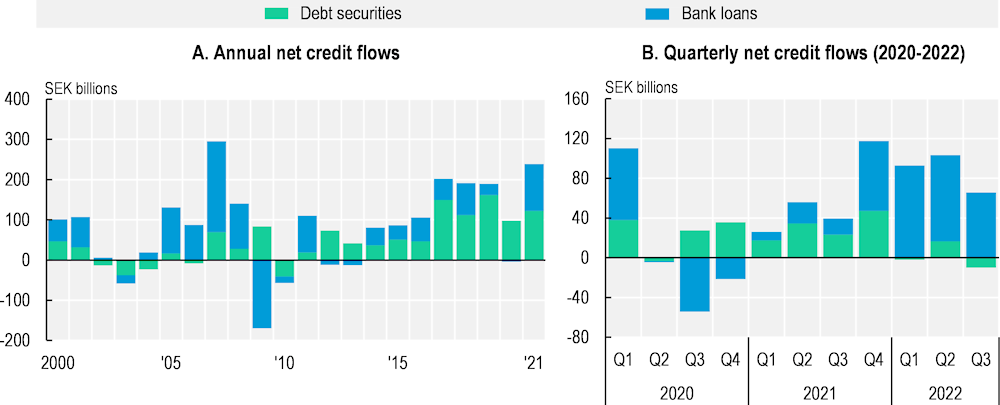

Figure 2.19 shows net credit flows to Swedish non-financial companies over time. Panel A illustrates the same broader Swedish trend seen in previous figures, namely a shift from bank financing towards debt securities around 2011. It also gives an indication of the pro- or counter-cyclicality of different types of borrowing during crises. In 2009, as bank lending contracted sharply, debt security issuance actually increased. However, two points need to be considered when interpreting these data. First, the year after, in 2010, credit flows from debt securities contracted more than bank loans in absolute terms, despite being a much smaller market segment. Second, the Swedish bond market of 2009 was very different from the one of today. As illustrated in Figure 2.11, in those years the market was dominated by a small number of large, established issuers issuing significant amounts. While market access for such companies is indeed important, it is not necessarily a good indicator of the extent to which a market provides resilience more broadly. The COVID‑19 crisis provides a better test of this, since by 2020 the market had expanded significantly to include a larger number of companies. Panel B below shows quarterly net credit flows from 2020 to 2023. Notably, it shows debt securities contracting in the second quarter of 2020 during the peak of the pandemic-related market uncertainty. These flows turned positive again in the third quarter, notably as the Riksbank’s corporate bond purchasing programme began in September, instilling a degree of trust in the continued functioning of the market.

Figure 2.19. Net credit flows to non-financial companies in Sweden

Note: See endnotes for commentary on data updates relating to this figure.

Source: Financial Accounts from Statistics Sweden (SCB).

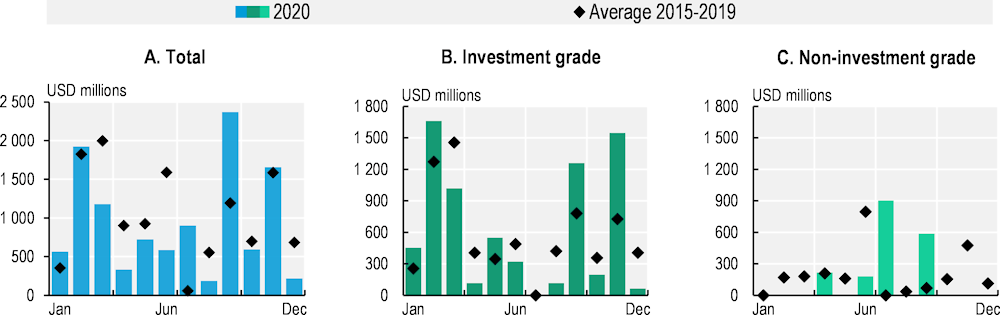

Figure 2.20 provides a more detailed account of primary market issuance during the COVID‑19 crisis. In the early months of the pandemic, issuance was significantly lower than its five‑year average for the market as a whole (Panel A). With the exception of July and September (when the central bank’s purchasing programme began and issuance increased sharply), this held true for the full year. February and November saw similar numbers as previous years. This is in sharp contrast to global developments, where total issuance markedly exceeded historical averages, in particular in the crucial months of March, April, May and June (OECD, 2021[6]). To an extent, this is likely driven by the US Federal Reserve’s intervention in March 2020, which was much earlier than the Swedish equivalent.

However, as Panels B and C reveal, the dynamics differed substantially between the investment grade and non-investment grade segments of the Swedish market. Notably, investment grade issuance was in line with previous years’ issuance for the full year, and significantly higher in February, September and November. Total issuance in 2020 was 63% higher than in 2019. Contrarily, non‑investment grade issuance was non-existent in the first three months of 2020. It remained below historical averages in every month, with the exception of April, July and September. However, issuance in these months was driven by a handful of large bonds by no more than one issuer per month.10 In total in 2020, there were no more than five non-investment grade bonds issued by Swedish companies, and the full-year amount was 24% lower than historical averages.

Figure 2.20. Swedish non-financial bond issuances during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Note: Panel A includes unrated bonds. Not adjusted for inflation.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

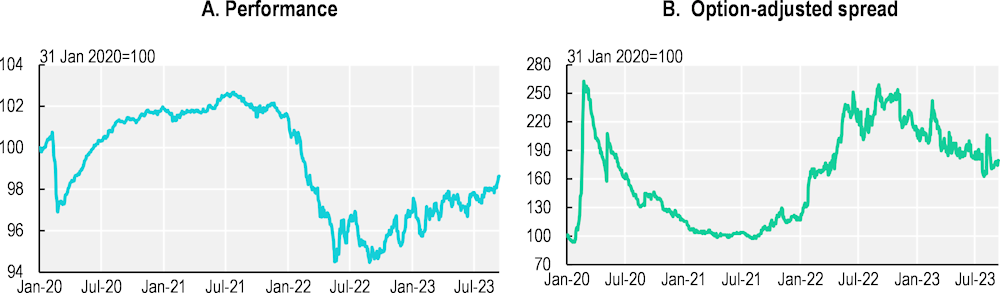

The significant impact of the COVID‑19 crisis can be seen even more clearly in the secondary market. Figure 2.21 below shows how an index of investment grade bonds issued in SEK developed during 2020 and more recently. The index fell very sharply in March 2020, gradually recovering over the year, assisted by significant fiscal and monetary support at the national and supranational levels (Panel A). Panel B shows the option‑adjusted spread, which increased 2.5 times from 31 January to 24 March. These developments are both indicative of a major sell-off and liquidity crunch. These dynamics were not unique to Sweden. The S&P 500 Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index (effectively the US equivalent of the index presented below) fell even deeper and spreads increased more than for the Swedish index. However, this should be considered with two points in mind. Firstly, substantial parts of the Swedish market are unrated (as seen in Figure 2.4) or rated non-investment grade. Since the index does not reflect these bonds, it gives only a partial picture of the market which is likely skewed towards its strongest part. Secondly, the US index recovered much faster (both in terms of performance and spread) and more strongly after the initial downturn, indicating less uncertainty about the market’s continued functioning (again aided by substantial fiscal/monetary support). In addition, the figure illustrates the significant pressure the market has been subject to with the tightening of monetary policy since 2022, with valuations falling below the 2020 nadir and spreads reaching similar levels. Comparable developments can be seen globally, although Swedish spreads appear to be very elevated compared to e.g. the S&P 500 index mentioned above, for which spreads did not come close to reaching 2020 levels in 2022.

During the COVID-induced crisis, a lack of liquidity was arguably the most pressing issue on the Swedish corporate bond market. During times of financial distress, supply and demand on capital markets tend to be lopsided as large parts of the market rush to sell riskier assets and to buy safe ones. These dynamics lead to e.g. the increased spread seen in the market, typically coupled with a widened bid-ask spread for most corporate bonds. However, in a resilient market, the price formation process should not break down entirely in such a scenario. When it does, it is indicative of a completely one‑sided market where prospective sellers are not certain they will be able to find a buyer at all for their investments. These tendencies were visible in the Swedish bond markets in 2020 (and indeed in Europe more generally), as roughly 30 investment funds, with aggregate assets under management equivalent to some SEK 120 billion, temporarily froze owing to lacking information on closing prices and trading volume (Riksbanken, 2021[41]). In addition to domestic investment funds, foreign investors also offloaded significant holdings of Swedish corporate bonds (Becker et al., 2020[26]).

Figure 2.21. S&P Sweden 1+ Year Investment Grade Corporate Bond Index

Note: The index includes investment grade bonds (as determined by ratings from S&P, Moody’s or Fitch) denominated in SEK with a minimum notional outstanding amount of SEK 250 million and a maturity of more than one year.

Source: S&P Global.

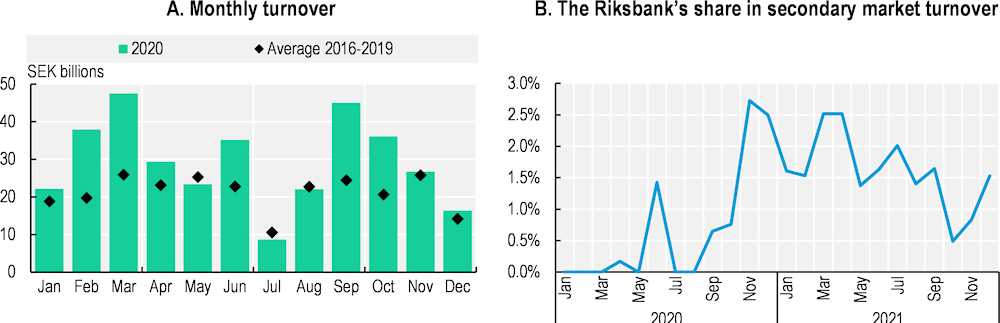

These adverse developments were to an extent an effect of the ownership structure on the Swedish market. As shown in Figure 2.14, investment funds represent a significant share of domestic ownership. Similar to banks, open-ended investment funds engage in liquidity transformation, since they offer investors share liquidity which exceeds that of the underlying assets. There is evidence that in the EU as a whole, the share of non-liquid assets in bond funds’ total assets has increased substantially over time (ESRB, 2019[42]). The potential threat of this type of activity to financial stability is typically not visible as long as there is not a significant demand from investors to liquidate their assets simultaneously. This is, however, precisely what happened during the COVID‑19 crisis. Panel A of Figure 2.22 shows how market turnover increased over historical averages, roughly doubling in February and March of 2020. Panel B shows the Riksbank’s share in total secondary market turnover, following its intervention in the markets. It should be noted that these increases are not indicative of improved general liquidity, since they do not take account of the increased selling pressure (i.e. they do not say anything about the development of the share of trades that could not – at least not at a price deemed acceptable to the seller – be executed), nor of the difference between types of bonds (e.g. investment grade and non-investment grade).

Figure 2.22. Turnover in the Swedish secondary corporate bond market during the COVID‑19 pandemic

Note: Refers to spot contracts for SEK-denominated corporate bonds. Monthly figures are sums of daily data. Secondary market trading is calculated as total turnover subtracted by transactions identified as primary market trading. See endnotes for commentary on data used in this figure.

Source: Sveriges Riksbank (SELMA Statistics).

The FSA’s analysis concludes that the corporate bond market has not offered more flexible financing than banks in times of crises in Sweden, meaning it does not provide the same type of counter-cyclical financing as the EU and US markets. However, issuers who could access bond markets in foreign currencies were able to benefit from greater flexibility. Over the past decade, the vast majority of SEK denominated bonds issued by Swedish companies (around 90%) were not traded on any given day, compared to a figure of about 60% for foreign currency denominated bonds. However, it bears mentioning that Sweden has a stable and profitable banking system that exited the 2008 financial crisis (and the subsequent euro crisis) in a comparatively strong position. Notably, while bank lending was below trend in Sweden both following 2008 and the euro crisis, this was driven by a decrease in foreign currency lending, whereas domestic currency bank loans remained remarkably stable (Becker et al., 2020[26]).

2.8.2. Policy responses to improve market resilience and liquidity

Shortcomings in the Swedish bond market during the COVID‑19 crisis have prompted initiatives by several regulators and public bodies to reform the market and increase its resilience. Notably, in 2021 the government tasked the FSA with investigating the need for additional liquidity management tools to deal with liquidity risk for investment funds. It reviewed three such tools: swing pricing (adjusting the fund unit value or sales and redemption price of the units up/down depending on the costs associated with the fund’s net flows); anti-dilution levies (a fee levied on investors when they sell/redeem fund units); and redemption gates (allowing funds to postpone redemptions above pre‑defined thresholds). The FSA’s assessment was that the application of anti‑dilutions levies is possible within the existing legal framework, along with a certain type of swing pricing.11 It also believes that the use of redemption gates should be allowed. The conditions for applying these tools should be regulated “in legislation and related regulations”. Swing pricing has been identified as a priority area. The FSA also recommends that a requirement for investment funds to be open for redemption at least twice per month be reflected in law, along with the longest allowed redemption time (Finansinspektionen, 2021[43]).

In an article in the financial press, the Director General of the FSA has also urged market participants to improve their conduct, notably with respect to disclosure and transparency, and encouraged the development of a self-regulatory regime by the SSMA. The article stresses the need for investment funds to improve their liquidity management by designing their portfolios with scenarios of market pressure in mind, for example increasing the share of liquid assets or making clear to investors that they do not offer daily redemptions (Finansinspektionen, 2021[14]). These discussions are reminiscent of those that took place in the United States during the so-called “taper tantrum” in mid‑2013 when the substantial selling pressure had large effects on corporate bond prices and officials considered imposing exit fees on bond funds (Çelik, Demirtaş and Isaksson, 2015[30]).

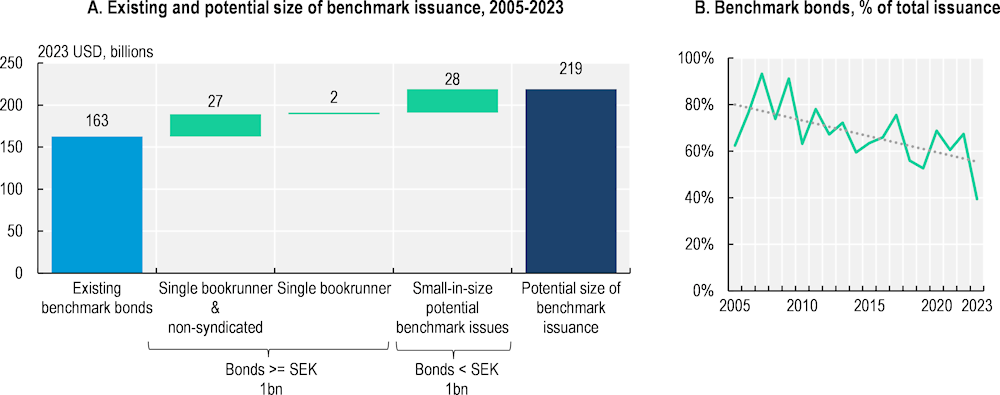

Further, the Riksbank, the Swedish National Debt Office and the FSA have jointly called for the introduction of a Swedish standard for benchmark bonds. Their proposed benchmark standard has three key elements: a minimum issuance of SEK 1 billion (corresponding to roughly USD 100 million at the time of publication of the proposal – as shown in Figure 2.11, in 2023 more than 70% of the number of bonds issued by Swedish companies were below USD 100 million); a minimum of two bookrunners to broaden the investor base; and issued through syndicated public transactions in line with the Eurobond market standard. The institutions argue that this would help develop a base of long-term investors such as insurance companies and pension funds that contribute less to liquidity crunches in times of financial distress compared to the currently dominant investment funds. In addition, they suggest that moving towards a benchmark standard would increase liquidity in the market, to the benefit of e.g. investment funds that depend on liquid markets to meet redemptions (Finansinspektionen, 2022[15]).

Panel A of Figure 2.23 illustrates the total amount of existing issuance made up of bonds that comply with the proposed benchmark criteria and explores the extent to which this could be increased based on the existing market structure. Potential benchmark issues are identified in two different ways. The first refers to bonds that already have a denomination that is larger than or equal to SEK 1 billion but that use less than two bookrunners and/or are not syndicated. The second category instead looks at bonds with denominations below SEK 1 billion that are issued by companies that could reasonably issue benchmark standard bonds. These companies are defined as those whose total issuance, based on several bonds, exceeds SEK 1 billion over a one-year period. Only the small-in-size bonds by these issuers are considered in the amount of potential benchmark bonds. From 2005-2023, the total actual benchmark issuance by Swedish companies amounted to USD 163 billion (67% of total issuance during this period). Using the above provided definitions of potential benchmark issues suggests that an additional USD 56 billion could have been issued through benchmark bonds, an increase of over one-third, bringing the total to USD 219 billion (90% of total issuance). The potential benchmark amounts are roughly evenly split between bonds with a denomination above SEK 1 billion and small-in-size bonds issued by potential benchmark issuers. Since benchmark issues by definition are large in size, when looking at the number of bonds issued rather than amounts, benchmark bonds made up 23% of all issued bonds during the same period.

Panel B shows the share of benchmark issues in total issuance over time, which has fallen from an average of 77% from 2005-2010 to 64% from 2011-2023. This is in line with the broadening of the market to include smaller issuers.

Figure 2.23. Existing and potential Swedish benchmark issuance, 2005-2023

Note: Refers to non-financial companies. The definition of a benchmark issue is in line with the proposal by the Swedish Riksbank, the Financial Services Authority and the National Debt Office and is defined as any bond that: has an (inflation-adjusted) issuance amount above or equal to 1 billion SEK; a minimum of two bookrunners; and is syndicated. There are two categories of potential benchmark bonds. The first is bonds that already fulfil the size criterion (>= 1bn SEK), but that are not syndicated and/or use a single bookrunner. The second category is bonds that are smaller in size than SEK 1 billion but that are issued by a company that is identified as a potential benchmark issuer, defined as having issued at least SEK 1 billion and more than one bond in a one-year period. Only the small-in-size bonds by these issuers are considered in the amount of potential benchmark bonds.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, LSEG.

In addition to encouraging the development of such a standard, the central bank has outlined a number of recommendations of measures that can be taken by different market participants, which are summarised in Box 2.1.

Box 2.1. The Riksbank’s proposals for a better functioning corporate bond market

In its 2021 report Towards a better functioning corporate bond market, the Swedish Riksbank outlined a number of possible action points for different market participants (issuers, investors and banks). Its nine recommendations are briefly summarised below.

Issuers

Companies issuing bonds may contribute to market development and liquidity by: issuing fewer but larger bonds, thus establishing a credit curve; involving more banks (bookrunners/arrangers) in the issue process, thereby expanding the investor base; and obtaining credit ratings for more issues.

Investors

Investors, most notably investment funds, may: communicate more clearly to retail investors the liquidity risk and limitations of investing in fixed income funds (notably by reporting spread exposure1 in fact sheets, on websites, etc.); limiting the offering of daily redemptions (exchanges/fund platforms can play an important role in this regard); and by ensuring they are adequately managing liquidity risk, e.g. by increasing the share of liquid assets and possibly applying liquidity management tools such as swing pricing.

Banks

As advisors and dealers, banks can: encourage issuers to obtain a credit rating and discourage the issuance of a large number of smaller bonds; publish price data in a timely manner (including for private placements); and finally possibly enter into resale agreements whereby issuers pay them to be more active in the markets, although the report notes that this may also bring disadvantages such as increased borrowing costs, since the pricing of such services may be difficult.

Note: 1 The value reduction of the fund as a share of its current value in a scenario where the interest rate spread between its holdings and government bonds doubles.

Source: Riksbanken (2021[41]), Towards a better functioning corporate bond market, https://www.riksbank.se/globalassets/media/rapporter/riksbanksstudie/engelska/2021/towards-a-better-functioning-corporate-bond-market.pdf.

2.9. The role of real estate companies in the Swedish corporate bond market

The real estate sector represents an important part of the Swedish corporate bond market, accounting for almost half of total outstanding bonds issued in domestic currency by amount (Wollert, 2020[13]). This has raised concerns that a fall in real estate prices could reverberate through other sectors of the corporate bond market, threatening financial stability more generally (Riksbanken, 2021[41]). This is particularly relevant given the very steep increase in property valuations in Sweden since the mid‑1990s, and has been further exacerbated by the sharp increases in interest rates since 2022. Work within the OECD Capital Market Series typically does not include the real estate sector. However, given the size, concentration and importance of real estate companies in the Swedish bond market, this section provides an overview of the sector’s use of corporate bond financing and how it compares to that of other non-financial companies. The Annex provides details on the types of companies that are included in this analysis.

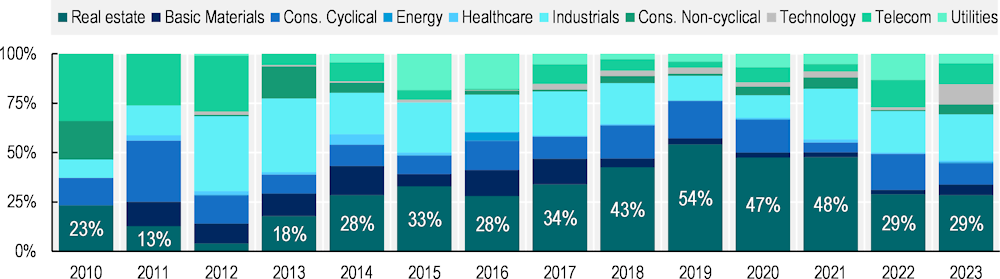

Real estate companies have gone from representing a negligible share of the Swedish bond market to becoming very substantial, accounting for 37%12 of outstanding amounts at the end of 2023. In 2021, they represented as much as 48% of total issuance (Figure 2.24, Panels A and B).13 Issuance has been particularly high since 2017, averaging USD 10.8 billion annually between 2017 and 2021, up from an average of USD 3.3 billion from 2010 to 2016. However, because the real estate industry is typically very interest rate-sensitive, issuance contracted 66% in 2022, down to representing 29% of total issuance. Issuance contracted by another 11% in 2023.

Figure 2.24. The real estate sector’s role in the Swedish corporate bond market

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

Including real estate companies in the analysis significantly changes the industry composition shown in Figure 2.13. As shown in Figure 2.25, between 2019 and 2021 real estate companies made up roughly half of annual issuance, up from 20% on average between 2010 and 2015. This degree of concentration exposes the bond market as a whole to fluctuations within the dominant industry. Given the real estate sector’s particularly strong link to the financial sector (e.g. because of the amount of real estate collateral held by banks), this lack of diversification may be a financial stability concern, especially when considering the prospect of longer periods of stricter financial conditions and its likely impact on real estate prices. A protracted downturn could impact the two main sources of credit, the banking sector and the bond market, simultaneously. The impact of tighter credit conditions on the sector can be seen in 2022 and 2023, when its share in total issuance decreased sharply.

It bears noting that real estate companies do not seem to issue foreign currency denominated bonds to a greater extent than non-financial companies. In fact, they have issued a larger share of SEK-denominated bonds in the last decade.

Figure 2.25. Industry composition of the Swedish corporate bond market (% of amount issued)

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

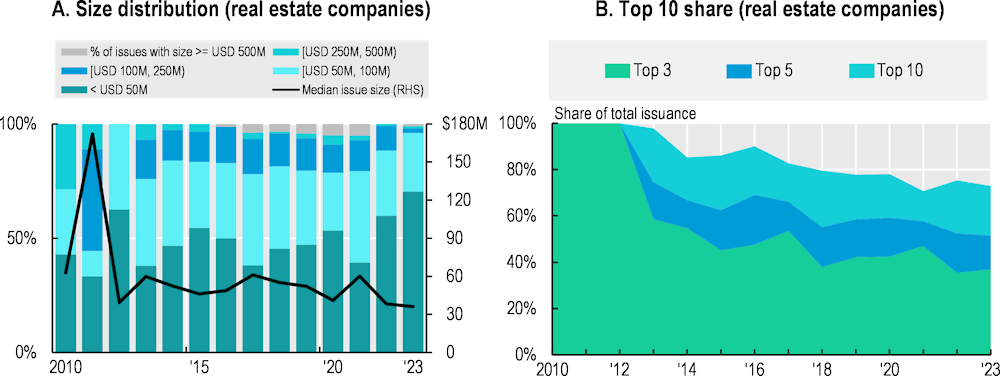

The median issue size by real estate companies has remained relatively constant since 2012, averaging USD 49 million between 2012 and 2023 (Figure 2.26, Panel A). The distribution of issue sizes is weighted more towards smaller issues among real estate companies than is the case for the broader non-financial universe. While the two smallest size categories (below USD 100 million) made up 71% of the total number of issues by non-financial companies in 2023, for real estate companies it was as high as 96%. In spite of this, the concentration of total issue amounts by the top ten real estate issuers is higher than for non-financial companies (Figure 2.26, Panels A and B). The top three real estate companies have represented an average of 41% of total issuance by the sector in the past five years, compared to 35% for the top three non-financial companies. This is partly a natural effect of a smaller sample of real estate companies, but it is also because many of the largest real estate companies issue several smaller bonds in any given year rather than issuing fewer, but larger bonds. This can be seen when comparing the share of the three largest bonds in total issuance in a year with the share of the total amount issued by the three largest issuers. For example, between 2015 and 2023, the three largest real estate bonds made up an average of 18% of total issuance annually. However, the three largest issuers made up an average of 43% of annual issuance, meaning their total issuance is made up by a set of smaller bonds.

This happens because companies want to issue bonds with different profiles (e.g. with respect to maturities to smooth their repayment schedule or in different currencies to attract different investors) and is not limited to the real estate sector. However, Swedish real estate companies issue a larger number of bonds per issuer than non-financial companies do. Between 2015 and 2023, non‑financial companies (those issuing bonds) issued an average of 2.2 bonds per year. The corresponding figure for real estate companies was twice as high at 4.4 bonds per issuer and year, indicating it is composed of active issuers to a greater extent than the broader non-financial group. Similarly, when looking at the median issue size (the bond) as a percentage of the median issuer size (the company) between 2015 and 2022, the average figure for real estate companies is lower (1.4%) than for non-financial companies (1.7%), meaning the former group of companies tends to issue smaller individual bonds relative to their size.

Figure 2.26. Size distribution and concentration of real estate issuers

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, LSEG, see Annex for details.

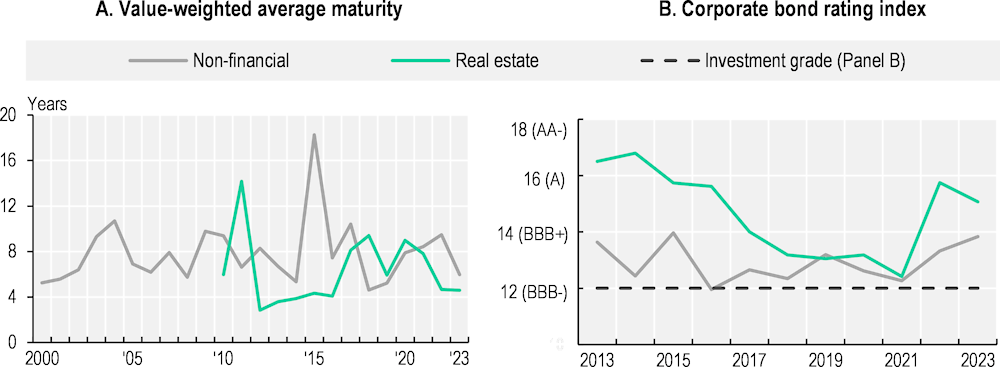

The real estate sector has generally converged with the non-financial sector over time both in terms of credit ratings and maturity profile, although there was some divergence in 2022. In 2021, the value‑weighted average maturity of real estate bonds was 7.8 years, compared to 8.4 years for the non-financial sector. In 2022, however, the average maturity decreased sharply to 4.7 in the real estate sector years whereas in the non-financial sector it increased to 9.5 years. In 2023, maturities for the non-financial sector decreased to 6 years and for real estate remained similar to that in 2022 (Figure 2.27, Panel A). As noted in section 2.3, when considering equal-weighted averages, maturities are shorter. This also holds for real estate companies, for which the simple average maturity in 2023 was only 3.9 years. The median was as low as 3.0 years.

The groups were even closer in terms of credit ratings in 2021, with the average value‑weighted rating for real estate company bonds at 12.4 (about half a notch above BBB-) compared to 12.3 for non-financial companies. In 2022, the average rating for real estate companies increased much more sharply, to 15.7, than that of non-financial companies (13.3). The two converged somewhat again in 2023. These developments are likely an effect of the particular difficulties faced by the real estate sector in a context of increased remote work and rising interest rates, leaving primarily higher-rated companies with (affordable) access to funding. Historically, the real estate sector had substantially higher ratings than the non-financial sector, in the order of three full notches on average between 2013 to 2016 (real estate company bonds had an average rating corresponding to A, compared to BBB for non-financial company bonds) (Figure 2.27, Panel B).

Figure 2.27. Maturity and credit rating profile of the real estate sector

Note: The real estate time series starts in 2010 in Panel A because issuance before that year was very small. The same applies for rated bonds in Panel B (from 2013). The peak for non-financial companies in 2015 in Panel A is driven by a set of four large bonds (between USD 344 million to USD 1.05 billion) issued by state‑owned power company Vattenfall with maturities between 62 and 63 years. See Figure 2.6 for equal-weighted maturities.

Notes

← 1. These figures are based on transactions involving US companies.

← 2. There were a number of sizeable domestic currency denominated bonds issued in 2007 and 2008, notably by manufacturing company Scania and state‑owned power company Vattenfall.

← 3. Notable USD denominated issues (>USD 500 million) without listing include Ellevio (2016), Atlas Copco (2007) and Stena (2014).

← 4. In practice, the incentives of the trustee to conduct any significant covenant compliance due diligence are rather weak, owing to a fixed fee structure and potential professional liability concerns. Their tasks are therefore often limited to administrative procedures. See e.g. (Çelik, Demirtaş and Isaksson, 2015[30]) for a more thorough review.

← 5. See Finish law 25.8.2017/574, and the regulation pertaining to the “repræsentant” in Danish law LBK nr 1 229 af 07 September 2016.

← 6. These requirements normally do not apply to investment firms trading only bilaterally. However, for so-called systematic internalisers (executing orders against their own books), it is mandatory to quote bids and offers. Such trading has increased since 2018, with corresponding reductions in OTC trading.

← 7. The survey includes market participants dealing in government bonds and covered bonds, in addition to corporate bonds.

← 8. An OTF is an Organised Trading Facility. MiFID II introduced OTFs as a new trading venue category, a multilateral system in which multiple third-party buying and selling interests in bonds, structured finance product, emissions allowances or derivatives are able to interact. An OTF is neither a regulated market nor a multilateral trading facility (MTF).

← 9. Defined as a low-volume investor with less than NIS 2 million (USD 559 000) in all TASE securities excluding options.

← 10. April and September: Verisure; June: Ellevio (two bonds); September: Volvo Cars.

← 11. The FSA calls this “adjusted sale and redemption price”, a method whereby the price of the fund units is adjusted up or down depending on net flows. Another type of swing pricing, which it calls “adjusted net asset value”, involves adjusting the value of the fund, which is not allowed in current fund-related legislation.

← 12. This share differs from that shown in the central bank’s staff memo (Wollert, 2020[13]). This is this is due to the following differences in methodology: 1) the central bank’s figures refer only to outstanding bonds issued in the domestic currency, while the present report also includes bond issued in foreign currency; and 2) possible differences in the industry classification used.

← 13. Throughout this subsection, “total issuance/outstanding amounts” refer to the sum of issuance/outstanding bonds by non-financial companies and real estate companies.