This chapter examines the strengths of current arrangements in Korea regarding the establishment of a learning health system. These include the availability of national health datasets and their governance which is among the best in the OECD, a track record of successful health system reforms, the development of the Drug Utilisation Review system to provide “real-time” decision support and a strong and committed research community. The chapter discusses how Korea, with a learning health system, could develop better performance measurement and value‑based care. A learning health system will not develop in Korea, however, unless important obstacles to harmonising and sharing data are addressed. Obstacles discussed in this chapter include a lack of trust, social licence and incentives toward data sharing and collaboration, a lack of a framework for research access to data, incoherent EMR systems and a lack of patient-reported data, and laws and policies that block progress toward a learning health system.

Towards an Integrated Health Information System in Korea

3. Appraising the Korean health data infrastructure and information system

Abstract

This chapter outlines the key features of the Korean health system, its structure and organisation, and how these influence the generation, management and use of data. A health system is defined here as the national approach to promote individual and population health through social, preventative and curative means. The scope principally includes public health, medical care, long-term care and social care. However, in terms of information relevant to health policy, data generated and stored outside the traditional health system boundaries are also relevant. As was described in Chapter 2, these include data on social and economic determinants of health inter alia income, employment, and education.

The structure and organisation of the Korean health system influences the national data ecosystem

This section describes the Korean health system, which is unique among OECD countries. The demand side is exclusively managed by the public sector through a national, compulsory insurance scheme (single payer model) with several government agencies responsible for managing and administering the funding and governance of the health system. The supply side, however, is highly reliant on the private sector and dominated by hospitals. It is very fragmented with limited gatekeeping functions at the primary care level and a high degree of consumer choice especially when accessing general and specialist care. As with all health systems, these structural features are important because they determine the way data are generated, managed and exchanged between relevant actors to create the information and knowledge that benefits the health and welfare of the Korean people.

Universal coverage is the cornerstone of Korean health care

The objectives of the Korean health system encompass safety, efficiency and effectiveness (i.e. quality) of care; equity (fairness) in access to care and health outcomes; and sustainability, which comprises a. ensuring the system copes with rising chronic diseases and demographic change (e.g. disease prevention and managing NCDs in non-acute settings), and b. supporting innovation and the development of cutting-edge medical technologies (WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2015[1]). These objectives become important when thinking about monitoring and improving system performance (building a learning health system).

The cornerstone of the Korean system, and a considerable strength, is universal access to health care. Social health insurance was introduced in 1977– first among formal sector workers in large firms, then smaller firms and finally to the self-employed – such that universal coverage was achieved in 1989. The financing system then underwent an important and major structural reform in 2000 with the merging of the three existing insurance schemes (comprising over 350 insurers) into a single payer, the National Health Insurance (NHI).

The NHI is based on a uniform contribution schedule and benefits package. For wage earners, contributions are proportional to income and shared equally between the employee and employer. For the self-employed, contributions are based on both income and the value of assets. Decisions on which health services to include in the benefit package are made centrally. Most health care services are included but cost-sharing is relatively high (20% for inpatient care). There is a ceiling on out-of-pocket (OOP) payments, with differential ceilings applied to different income groups and exemptions for the poor. The ceiling applies only to services in the benefits package and the role of voluntary health insurance is increasing.

Several organisations and agencies feature in the governance of the health system

The Ministry of Health and Welfare

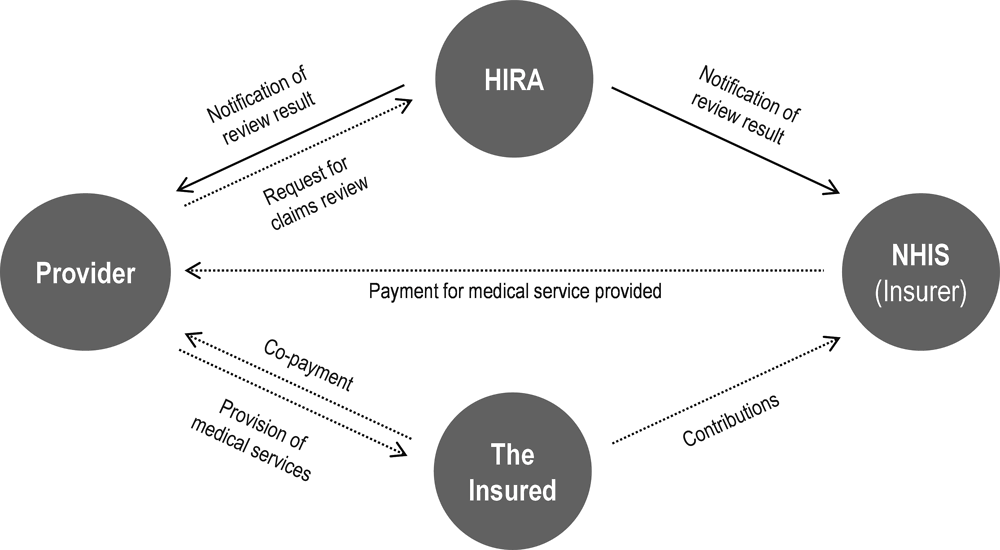

The Ministry of Health and Welfare (MoHW) is responsible for promoting health across the entire population. It plays a central role in health policy implementation at the national level. It implements various public health policies through collaborating with medical and health centres at the regional and municipal level. It also directly manages several national hospitals in areas the private sector fails to meet medical needs (e.g. psychiatric hospitals, tuberculosis). Governance of the Korean National Insurance (NHI) funding scheme is summarised in Figure 3.1. The MoHW has delegated the task of managing the NHI to two quasi‑independent agencies: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) and the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS).

Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA)

HIRA is a de‑facto regulator of health care provided through the NHI. Its stated mission is to address health burden, ensure patient safety and provide the best quality of medical service to the people of Korea. Its strategic direction is built around four pillars: 1. transitioning from volume to value in service provision; 2. Expanding coverage based on what people and populations need; 3. Promoting value through deployment of digital technologies; and 4. Building social value through innovation at all levels of the health system. HIRAs responsibilities concern managing the medical services included under the NHI, assess the quality of health services, as well as reviewing service claims (billing) filed by providers, then sent to the NHIS which reimburses providers.

Figure 3.1. Interaction between HIRA, NHIS, providers and the insured population under the NHI scheme

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from HIRA.

HIRA manages the benefits and services included in (and excluded from) the NHI as well as the fee schedule. It carries out evaluation of cost-effectiveness of medicinal drugs for health insurance reimbursement. The Drug Reimbursement Evaluation Committee (DREC), appointed by the president of HIRA, assesses the cost-effectiveness of drugs and recommends their inclusion or exclusion in the NHI benefit package. The value of these assessments could be greatly enhanced in the future by real-world data from electronic medical records as well as claims data.

HIRA’s claims review function promotes sustainability in health funding by monitoring use of services against expected trends through its Benefits Information Analysis System and a transition towards a value‑based review and assessment framework (see later in this chapter). It analyses health care activity to identify variation and assess quality of care, working with providers to promote quality improvement based on th collaboration with providers to adjust clinical guidelines to promote better care. these efforts have yielded impressive results across several aspects of health care (these are provided in a later section in this Chapter).

Other functions include managing the provider payment system, including Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs) for casemix payment, per-diem payments for long-term care hospitals (see below) and consultation fees for public health care centres (see below). HIRA also develops and manages the Korean disease classification system – the KCD, which is based on ICD with additional information to provide a richer source of data. These activities have enabled successful adoption of new classification system like ICD‑11.

In 2010, HIRA established a drug utilisation review (DUR) system, which uses HIRA’s real-time data on Korean patients to provide real-time alerts to clinicians and pharmacists regarding counter-indicated drug prescriptions due to pregnancy, drug-drug interactions, and counter-indications due to age. The DUR is a prospective, real-time review of each prescription before the medication is prescribed and dispensed to the individual patient to minimise the risk of harm such as drug/drug interactions or ingredient duplication. The DUR is enabled electronically by HIRA and is a good demonstration of the possibilities of using a combination of existing and new data to improve health outcomes using administrative health ese analyses. The mechanisms include a transition to an incentive programme and data (see below).

NHIS is the custodian of data on treatments, procedures and tests (although not results) as well as some socio-economic data to enable risk-adjustment. HIRA therefore has a lot of expertise and experience in collecting, managing, processing and analysing big datasets (including claims, drug prescription/utilisation, disease classification, and hospital activity data) as well as using the information derived from these analyses to promote quality and sustainability of the Korean health system.

However, while certainly more granular and detailed than many national administrative data sets, Korean claims data still lack information on health outcomes including clinical lab and image results, and patient-reported data. While HIRA publishes information on, for example, antibiotic prescription rates, the number of medicines per prescription, and Caesarean-section rate, these indicators could be enhanced by including data on their health outcomes.

National Health Insurance Service (NHIS)

NHIS is the single insurer of the NHI scheme and National Long-term Care Insurance providing health insurance coverage for the public. Roles and responsibilities of NHIS include eligibility management, premium imposition and collection, benefit reimbursement, disease prevention and health promotion as well as the Medical Aid Program, Long-term Care Insurance and integrated premium collection of social insurance programs. With its universal coverage, NHIS is committed to improving public well-being and contributing to the stability of the national health insurance fund by securing additional financial sources and a stable premium collection system. It has an upgraded benefit system to expand coverage and strengthen the social safety net to improve public health and quality of life.

NHIS exchanges national data (person-level data, from birth to death) with 42 organisations including the Ministry of Public Administration and Security, National Tax Service, National Pension Service, and HIRA. Based on these data, NHIS provides various health services, including PHR, management of metabolic syndrome and chronic diseases, and appropriate medication. The socio-economic variables present in the data enable the NHIS to conduct equity assessment based on tracking observed health service use (treatment) and health outcomes by income level or region. Diverse monitoring services are developed and offered based on the research database, which include infectious disease monitoring, chronic disease monitoring, health service use monitoring by region, financial status monitoring and K-ATLAS (health map). The public can access data through the Big Data Open System. This online platform helps alleviate information inequality and facilitate equal access. Sustainable development of health sector is supported by evidence for policy and industrial development.

Regional and municipal governments

Regional governments manage regional medical centres. They also have the authority to build new hospitals for their residents. Municipalities manage smaller, local health centres, subcentres and primary care clinics. Each municipality has one health centre that provides basic medical care as well as population health services such as antenatal care and vaccination. There might also be health sub-centres and primary care clinics to ensure residents’ access to basic health services in areas with limited access.

Funding flows from local taxes and national revenue sharing. Regional governments and municipalities do not have the authority to raise additional revenue for public health or health care. However, they do control resources and revenue is allocated within their catchment.

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS)

The MFDS is the Korean regulator for medicinal drug safety and effectiveness, like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Japan Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). While HIRA carries out cost-effectiveness analysis (see above), the MFDS is responsible for post-market surveillance of medicines – monitoring approved drugs for hitherto unnoticed adverse events, reactions, and other safety concerns. As has been demonstrated by the FDA, real-world data can greatly enhance pharmacovigilance efforts, as well as providing valuable information on how medical technologies perform in post-trial, routine clinical situations (see later section in this chapter).

National Evidence‑based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (NECA)

Established in 2009, NECA is a relatively new quasi-public agency that is in charge of carrying out health technology assessment. It generates evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of various health services, technologies and health products, and informs consumers, health care providers and health policy decision-makers including the payer.

NECA’s Center for New Health Technology Assessment (CnHTA) focuses on evaluating safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of medical procedures and diagnostics. Its Committee for New Health Technology Assessment, overseen by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, consists of 20 health professionals. There are five assessment committees by specialty area: internal, surgical, dental, traditional medicine and other procedures, which prepare review reports for deliberation by the Committee. This work would also be greatly enhanced by access to real-world clinical data from EMRs.

Korean Disease Control Agency (KDCA)

Management of NCDs and their well-known risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, overconsumption of alcohol, lack of physical exercise and obesity have become a major target of Korean public health policy. The main legal framework for public health activities includes the Regional Public Health Act and National Health Promotion Act.

The KDCA – formerly Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) – is responsible for conducting the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) which provides various data on health behaviours and risk factors. KDCA also conducts a community health survey and an ambulatory care survey focussing on particular disease conditions including circulatory diseases. It is the custodian of a national disease registry for diabetes. Provision of public health services is shared between the public and private sectors, due to the dominance of the private sector in the provision of health care (see below). Taking account of the social determinants of health, health in all policies has recently been promoted along with health impact assessments, making the data collected and held by the KDCA a very important resource.

The Korean Health Information Service (KHIS)

Health care providers are predominantly paid through fee‑for-service. All licensed providers are guaranteed a contract with NHIS unless they have committed serious misconduct. Almost all private health facilities have EMRs, principally because this enables electronic submission of claims for care. However, there is little harmonisation and concordance between these two systems in terms of interoperability and potential exchange of data. (Proposals to introduce personal electronic health cards, which enable individual’s health data to follow them wherever they seek care (a de facto national EHR) were resisted by providers due to privacy concerns).

The Korean Health Information Service (KHIS) was established in September 2019. Its main function is to certify EMR software, following the example of the US Office of the National Co‑ordinator (ONC) for Health IT. For an EMR vendor to become certified they must satisfy 86 certification criteria that ensure that patient data are in an electronic format that satisfies government standards for clinical terminology and exchange (electronic messaging). The system of certification of software vendors aims to expand the use of standards and the interoperability of clinical records. KHIS will also have a usage certification for health care institutions (hospitals and clinics) to ensure their EMR software meets government standards.

The KHIS EMR standardisation roadmap (2021-2025) consists of 5 core actions: Standardization of terminology; Adoption of HL7 FHIR; preparation of future oriented data standards; validation and expansion of best practices of standardisation; strengthening the basis for implementation of standardisation.

Key among these is adopting the HL7 FHIR standard for data exchange. As noted in Chapter 2, Korea is among 17 OECD countries that have adopted or are considering the adoption of this standard which supports interoperability and mobile app development. Work is under way between HL7 FHIR and OHDSI to integrate the OMOP CDM into HL7 FHIR, which would perfectly position Korea for global research given Korea’s investments in OMOP CDM.

Korea has also purchased SNOMED-CT licences for clinical terminology and is using other global standards such as ATC and LOINC. These global standards will position Korea to more easily code data to the OMOP CDM and to participate in research with other countries.

KHIS is also establishing the “My Health Way” platform where individuals can efficiently view and share their own personal health data which is otherwise scattered across the systems of each of their health care providers. Currently, patients wanting to share their own health data must visit and request data from each of their health care providers. The My Health Way platform project has been pursued by a Presidential Committee on the Fourth Industrial Revolution (see “Digital New Deal” below). A “My Health Record” App (Android) was launched in February 2021 that allows search, saving, and utilisation of public health data on a smart phone (such as HIRA records). An expansion to also include patients clinical data from private sector EMRs such as health care records and life log is planned (See below).

However, KHIS does not have a mandate to involve health information stakeholders in its work, nor the legal authorisation to support secondary uses of health data. This is addressed further later in this chapter and in Chapter 4.

Care provision is highly fragmented and hospital-centric

Except for a small number of national hospitals, special public hospitals and regional/municipal health care facilities, health care delivery in Korea relies heavily on the private sector. Almost all clinics and about 94% of hospitals are privately owned.

The legal framework for health care provision comprises the Health Care Law and the NHI Law. The role and function of health providers is not well differentiated, particularly between clinics and hospitals. Some clinics have inpatient beds while all general hospitals provide outpatient services. There is no gatekeeper role in the Korean health care system. Individuals are not required to register with any health care provider and have the freedom to choose health care provider at any level according to their preference, as long as they can afford to pay the necessary out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. With nearly unlimited access and patients’ preference for high-tech medical care, patients are increasingly using large general or tertiary hospitals.1

The dominance of the private sector in health care delivery goes back to the early years of the Republic. The Health Insurance Law was enacted in December 1963 by the military government soon after its coup d’état. But the law did not include the requirement of mandatory coverage. Full social insurance was implemented in 1977 as part of a national economic reform programme. Until then, meeting the health needs of the population had been left to market forces.

An incremental approach to extending coverage followed, achieving universal population coverage in 1989. This resulted in a steep increase in health care use over a short time. The private sector expanded rapidly to meet the increased demand.

Concentration of patients in the large metropolitan hospitals has been identified as an issue. Experts interviewed have suggested that retaining market share is a strong disincentive for smaller hospitals to exchange patient data with other providers.

The Korean Government tried introducing a primary care gatekeeping scheme in 1996. This was resisted by the medical professions and failed to gather sufficient support (Sung NJ, 2013[2]). In 2011, the MoHW proposed voluntary registration of hypertensive and diabetic patients with a primary care provider, with incentives to both provider and patient in order to promote care integration for these chronic diseases. The proposal was opposed by the Korean Medical Association and was later rejected.

In 2008, a pilot project for telemedicine dubbed “Ubiquitous health care” (U-health) was implemented in four remote Korean municipalities. The pilot aimed to evaluate the safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of U-health. The government has since tried to extend U-health to the elderly and to patients with chronic diseases. This was criticised by the public for being too business friendly. The KMA also opposed the policy, saying that the extension of U-health would enable the large, metropolitan hospitals to attract even more patients.

Remarkably, much ambulatory care in Korea is provided by hospitals. Even tertiary and specialised hospitals are offering these services, sometimes in competition with primary care providers and community hospitals.

Long-term care is covered by a mix of funding and governance

An amendment of the Medical Service Act provided criteria for long-term care (LTC) hospitals. These hospitals treat chronic illness, and care for patients at a post-acute stage, for example with dementia and disabilities. LTC hospitals are financed by the NHI, in contrast to LTC facilities, which are reimbursed by LTC insurance. LTC hospitals are paid on a modified per diem model compared with LTC facilities which are paid on a fee‑for-service basis. The distinction is significant because data generated by per diem payments lack the granularity of fee‑for-service data.

Residential care or nursing home care is provided by LTC facilities, licensed nursing homes, retirement homes, and licensed residential establishments. Home care or community care includes ADL-supporting care at home, portable bath services, nursing care at home, and day care services. Cash benefits are given to eligible people in remote areas or islands where no regular support is available.

The Korean health system performs well but there is room for improvement

The focus of this report is on using health data to improve the performance of the health system based on its objectives. This section briefly outlines how the Korean system performs on indicators compared to other OECD countries, although it should be noted that Korea does not supply data for several indicators and statistics collected by the OECD (these gaps are discussed in the following section).

Managing chronic diseases, mental health and perceptions of quality can be improved

Korean life expectancy at birth is among the highest in the OECD at 83.3 years compared to the OECD average of 81 years (OECD, 2021[3]). However, life expectancy is a blunt indicator of health system performance (and an even less useful metric for health care) due to the many non-medical factors that contribute to people’s health and longevity. Insofar as life expectancy is a proxy for health, little is known about differences across social strata – therefore about the equity of health and health care – in Korea.

Looking at more granular indicators of health system performance (OECD, 2021[3]):

Avoidable mortality (a more useful metric for how the health care system treats health problems) is lower than the OECD average (97 vs 126 per 100 000 population).

Treatable mortality is among the lowest, second only to Switzerland, at 42 (OECD average is 73 per 100 000 population).

Morbidity from chronic diseases, however, is slightly worse than the OECD average.

Hospital admission rates for diabetes and asthma are among the highest in the OECD (both close to double the OECD average), but among the lowest for congestive heart failure. They are just below average for COPD.

Despite universal health insurance coverage and the freedom to choose their provider, only 71% of Koreans report being satisfied with the availability of quality health care (similar to the OECD average).

The proportion of people who rate their health as “poor” is among the highest in the OECD (15.2% versus an OECD average of 8.5%).

Depression, anxiety and suicide rates in Korea are among the highest in the OECD.

At the time of writing, Korea has excelled at containing COVID‑19, with the number of cases and deaths is among the lowest of all OECD countries.

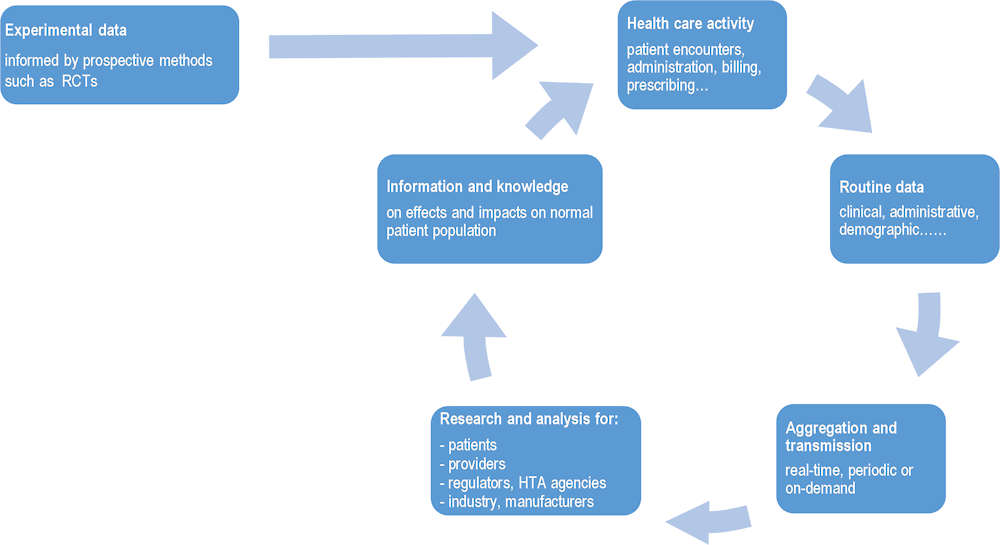

A good health data infrastructure and information system are critical to improving health system performance in three ways. First by providing the necessary data and information on whether objectives are achieved or not. Metrics and indicators are needed to inform policy makers, as well as providers and practitioners, about performance in the domains that are relevant to them. Only through regular monitoring and feedback can improvement occur, and performance be optimised. As was outlined in Chapter 2, a learning health system relies on a solid data infrastructure and health information system that covers all key performance domains.

Second, achieving objectives concerning health care quality and management of NCDs directly relies on health data exchange among relevant actors ranging from patients and their providers to regulators and policy makers, to researchers and industry. These actors can then use the available data to generate information and knowledge that is relevant to them, enabling them to monitor, learn and improve on a continuous basis.

Third, it paves the way for regulatory and policy mechanisms that incentivise better performance and enable more optimal resource allocation. For example, moving from a fee‑for-service remuneration model to one that rewards value for money is only possible with a granular data on outputs (activity) as well as outcomes (including patient-reported outcomes) and costs across entire care cycles that span the acute, non-acute and long-term care settings. These themes are explored later in the report.

Creating a learning health system requires addressing data gaps

A learning health system utilises health data effectively to create a continuous cycle of improvement through reflection, adjustment and evaluation. They are characterised by using all available data to generate metrics that measure performance against its objectives, and feed this information back to relevant actors in a continuous cycle of quality improvement. This is impossible without comprehensive, high-quality data.

Although the Korean system is awash with administrative and activity data, consolidated data on outcomes (e.g. unplanned readmission) beyond where this results in a claim (e.g. admission to hospital) or an end point (e.g. death) are lacking. More subtle clinical outcomes (e.g. test results) as well as patient-reported metrics are not reported consistently. Problems with coding and reporting present-on admission (POA) flags – an important tool to identify patient safety lapses in hospitals – have been described. These and other challenges mean that Korea does not provide several health statistics collected by the OECD (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Selected indicators and statistics not reported to the OECD by Korea

|

Patient safety |

|

|

Care quality |

|

|

Other |

|

These gaps make it difficult, perhaps even impossible, to truly assess how the system performs against the goals of safety, efficiency and effectiveness (i.e. quality) of care; equity (fairness) in access to care and health outcomes; and sustainability. For example, not knowing life expectancy by education level makes it difficult to gauge how equitably health outcomes (some of which will manifest in longevity) are distributed across the Korean population regardless of their socio‑economic status.

Meaningful performance monitoring and improvement

The performance of a health system against relevant domains depends on a variety of factors covering policy and organisational structures, institutional management, workflows and supplies, working conditions and environments, training and patient experiences, values and behaviours. A continuous loop of quality and safety monitoring, reflection, evaluation and improvement must be inclusive of and be relevant to all of the stakeholders involved – from the clinical microsystem to regulators, to high-level decision makers. Some examples are provided in the box below.

A learning health system, by definition, measures and evaluates all relevant domains, acting on the steady flow of information by putting in the necessary structures and capacities to continually improve its performance. The two fundamental steps of creating a high performing, learning health system are:

1. Develop routine monitoring and evaluation of domains relevant to health system objectives.

2. Ensure that the data to allow examination of the important questions are available, and can lead to a continuous loop of evaluation, reflection and adjustment.

In areas where HIRA has a direct mandate, Korea participates fully in OECD data collection and statistics, especially quality and safety. However, the health care quality assessment work of HIRA is limited predominantly to claims data for services reimbursed by the NHI scheme. While these data cover the entire population, they exclude certain outcomes and aspects of health care and quality domains, as is evidenced by Korea’s reduced participation in the OECD reporting of safety indicators. This limits Korea’s capacity to understand and improve health care quality and performance. Some examples of other countries using their data to drive learning are presented in Box 3.1 below.

Box 3.1. Other countries are using data assets to enable continuous learning and improvement

Clinical care quality registries in Sweden have been developed for several chronic diseases. These registries collect data about individual patients including medical interventions, procedures and outcomes where data are integrated into clinical workflows and are available to health care providers in real time. The registries are used by patients, health care providers, and health care institutions in a continuous loop of health care improvement and are considered by Sweden as a reason for the country’s high level of care quality when compared with other OECD countries (Quality Registries, 2021[4]; Oderkirk, 2021[5]).

An additional consideration of the learning health system paradigm (beyond the scope of this report) is that stakeholders must be empowered to act on data/information on their performance. At the Veteran’s hospitals in the United States, a dashboard of relevant quality metrics is provided to clinical teams but, importantly, those teams were integral leaders in the continuous improvement loop who were developing organisational and work process changes. Key outcomes of the process were improvements in both patient health care outcomes as well as in workplace culture and the morale of the health care providers involved (Meredith LS, 2018[6]).

Lastly, Finland’s ministry of health and welfare (THL) has been developing clinical care quality registries over the past five years and serves as a useful example for Korea because, like HIRA, the THL collects health data covering the full population and has a sophisticated programme of national health care quality reporting and is, therefore, planning registries that are national in scope. THL’s aim is to improve patient outcomes by improving care quality, treatment effectiveness and patient safety through services that are patient-centred, timely and equitable regardless of ethnicity, location or socio‑economic status (Peltola, 2020[7]).

The inclusion of patient reported experiences and outcomes (PREMS and PROMS) in Finland are key to measuring patient-centredness. The aim of the new registries is to improve health care by streamlining patients’ treatment paths, comparing, and developing treatment practices, examining effectiveness and safety of different treatments, communicating treatment results openly to patients and other citizens, and steering the service system and service production towards high-quality and effective care (THL, 2021[8]).

The foundation of the information system in Finland is the integration and linkage of high quality and timely real-world data (RWD) from insurance records, clinical records, patient-reported data and contextual data regarding socio‑economic and environmental factors that influence patient outcomes.

Value in health care is typically defined as the ratio between health care outcomes and costs. It can be achieved by improving outcomes, reducing costs, or both. People‑centred and value‑based care models change the orientation of health care systems from paying for sickness care to rewarding a cycle of continuous improvement toward care that delivers value for patients and society. A pre‑requisite to achieve a health care system that delivers value for patients and citizens is a modern, interoperable health data infrastructure that can deliver information on short- and long-term outcomes from a patient and population perspective (the other is to measure the costs of producing not just outputs but outcomes).

For example, under the current Korean fee‑for-service payment system claims data of patients with non-communicable diseases include treatment continuity information (number of visits and number of prescription dates), but does not collect patient treatment outcomes (e.g. HbA1C levels in diabetic patients). In treatment of AMI and acute stroke, 30‑day mortality rate after admission is collected, but pre‑hospital or between hospital data are insufficient.

At the core of making health systems more people‑centred is the ability to systematically collect data on what matters most to patients through patient-reported outcome (PROMs) and experience (PREMs) data collections. Such patient-reported data are among the key elements proposed by Porter and Lee as part of a value agenda to measure and reward value‑based care. Other key elements include multi-disciplinary care teams providing person-centred care, measurement of each patient’s health care outcomes and costs, and the IT infrastructure and data standards necessary to measure and reward value (Porter, 2013[9]). Of course, traditional outcomes are still critical to patient safety, such as measurement of survival after treatment, avoidable hospital admissions and adverse events, but these traditional measurements alone do not give insight on whether the patients’ needs have met and their functioning improved. For example, if the treatment has allowed the patient to re‑join the workforce.

National patient-reported outcomes measurement is still relatively new among OECD countries. However, Norway and the Netherlands, as well as the United Kingdom have national PROMs measurement in place for several conditions and procedures. Denmark is also developing a comprehensive national PROMs monitoring programme (see Box 3.2). Based on the recent OECD survey of health data governance and use as well as interviews with local experts, this is a new area in Korea and needs national-level discussion. In 2019‑20, Korea reported to the OECD that there was no national measurement or regional measurement of PROMs for any disease condition, but there were some initiatives within individual hospitals for hip and knee, breast cancer and prostate cancer patients. Since 2020, HIRA is using symptom and behaviour evaluations in dementia patients (PHQ‑9, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), Global Deterioration Scale (GDS)) as outcome measures. PREMs are partially, but gradually expanding from individual hospital units to national units.

Box 3.2. Patient-reported outcomes measurement is still relative limited in many countries

An OECD 2019‑20 survey indicated that PROMs are still relatively uncommon among OECD countries. Overall, 12 countries out of 23 reported having national PROMs data collections for at least one disease area or patient group.

Australia reported that Australia and New Zealand had a Prostate Cancer Outcome Registry using the SF‑12 and EPIC‑26 PROMs (general health/quality of life and disease‑specific items). Canada reported the ESAS-r as the national standard PROM tool recommended by Canadian Partnership Against Cancer as well as the EQ‑5D quality of life tool. National standards were also developed for PROMS for hip and knee replacement including the EQ‑5D‑5L, Oxford Hip Score, and Oxford Knee Score. France reported utilising the PROMIS‑29 (quality of life PROMS) at the national level. The United States reported using PHQ and GAD measures for severity of depression and anxiety.

Norway has an advanced programme of PROMs monitoring at the national level. Norway reported national PROMs using the following generic instruments: RAND‑12, WHO‑5, EQ‑5D‑3L, and SF‑36; and the following disease specific instruments: COPD Assessment test, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Problem Area in Diabetes Scale (PAID), the Gold Scale, Perceived Competence in Diabetes Scale (PCDS), Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale‑29 (MSIS‑29), Mini Mental Status Evaluation (MMSA-NR3), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), I-ADL, P-ADL, Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline (IQCODE), Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q), Cornell Scale for depression in dementia (CSDD), Mayo sleep form, VAS smerte, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score questionnaire (KOOS), Owestry Disability Index (ODI), Neck Disability Index, ISCoS International SCI Quality of Life data set, AddiQoL, m-HAG, DAS28‑CRP, BASDAI, DLQI, Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE‑Q), Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA), and Sullivans Catasthopizing Scale.

The Netherlands also has an advanced programme of PROMs monitoring at the national level including under the umbrella of the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing (DICA): PROMS for colorectal cancer, oesophagus cancer, gynaecological cancers, low back pain, morbid obesity, head neck cancer, skin cancer (melanoma), and breast cancer. Cataract surgery PROMs are also collected nationally. The National Health Care Institute collects national PROMS for hip and knee osteoarthritis patients and there is a national heart registry collecting PROMS for CVD patients. Under the Netherlands patient federation, every person with a disease or disability is invited to fill in a questionnaire about health and participation.

Denmark has a national PRO Secretariat under the Danish Health Data Authority. Work includes national PROMS for apoplexy, knee/hip osteoarthritis, depression, diabetes, heart rehabilitation, pregnancy/maternity, psoriasis and palliative care.

Source: Oderkirk (2021[5]), “Survey results: National health data infrastructure and governance”, https://doi.org/10.1787/55d24b5d-en; Pro Secretariat (2019[10]), “The Danish National Work on Patient Reported Outcomes, Danish Health Data Authority”, https://pro-danmark.dk/da/pro-english.

A recent example of value‑based health care measurement and improvement can be seen in Massachusetts for breast cancer surgery patients. Longitudinal collection of PROMs at various points along the care pathway is undertaken and the results are made available to patients and integrated within the clinical workflow to support clinicians and patients to make treatment decisions. The purpose is to detect and monitor changes in physical and psychosocial function. Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) have launched an app for breast cancer oncology patients that has an interface to both clinical and administrative systems and gathers PROMs from patients throughout the cycle of care (Brigham Health, 2021[11]). This work has been expanded to develop measures of time and activity-based costing that could support value‑based payments.

In Korea, HIRA is collecting PROMs data for research purposes, examining health outcomes associated with high-cost medications among cancer patients treated in hospitals, in particular pain and impacts on quality of life. The pilot began in 2020 and the results will be used to evaluate the potential usefulness of PROMs data in value‑based payment. Initial plans are that PROMS could be expanded to other health care settings and a broader range of health conditions. The data collection method is expected to be electronic, such as a Web-based (Internet) survey.

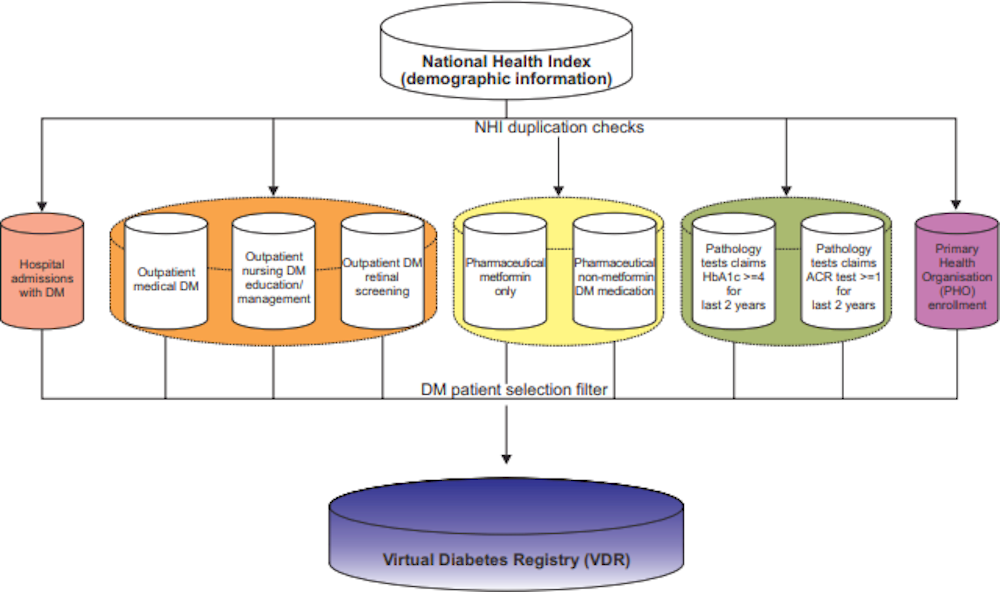

Building ‘virtual’ disease registries from existing data: less costly, more accurate

Disease registries contain data that can yield important information and enable value‑based services and a learning health system. However, registries are often developed and maintained manually and separate to existing data infrastructure, This duplication is costly inefficient. Modern data science and analytics can help. Linking existing datasets to build registries is an economical way to create an information repository that can inform a range of policy and practice decisions. Models based on EMR data have been demonstrated to deliver high predictive accuracy in identifying people with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes (Anderson, 2016[12]).

Health authorities in New Zealand are developing virtual registries for chronic diseases by extracting relevant data from a range of existing sources including EMRs, hospital admissions, primary care and pharmaceutical dispensing (Figure 3.2). The virtual diabetes registry allows for disaggregating prevalence estimates to the level of District Health Boards (local holders of health care budgets in New Zealand) and primary care practices. The information can be used to monitor quality of care and its outcomes across regions. Also, data from the registry allows for predicting who may be at risk of developing diabetes so that health care providers can act accordingly. If Korean health data (especially clinical data) are standardised and/or mapped to a CDM, there is little standing in the way of creating similar registries covering the entire population for all relevant diseases.

Figure 3.2. Databases for a virtual diabetes registry in New Zealand

Source: Jo (2015[13]), “Development of a Virtual Diabetes Register using Information Technology in New Zealand”, https://doi.org/10.4258/hir.2015.21.1.49.

Better payment methods and resource allocation rely on integrated data

An assessment by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2016 found that interest in value‑based care and adoption of bundled payment systems was highest among countries spending over 10% of GDP on health care and was motivated by the need to control rising health care costs. However, if found that there was little implementation of value‑based care models in practice (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2016[14]).

One way to reward value (rather than volume) is to replace a fee‑for-service payment model with a method that provides a bundled payment for an entire care pathway. Bundled payments are a risk-adjusted contract with all providers and services over a full cycle of care (or period of time). Outcome measures are used to reward care cycles that meet or exceed objectives through an incentive payment.

The major impediment to developing value‑based incentive payments in Korea is the lack of health data exchange and interoperability because methods such as bundled payments, for example, require accurate tracking of patients’ progress across multiple settings and providers over a lengthy period of time (see Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Value based payments: Examples from OECD countries

A recent paper provides an assessment of the extent to which value‑based care models have been implemented in the United Kingdom (England), Norway, the Netherlands and the US state of Massachusetts (Mjåset, 2020[15]). The study found that both England and Norway were developing a bottom-up approach to costing that would allow measurement of the costs of a full patient treatment pathway that could then be used to reward value.

In the United Kingdom (England) the approach is called the Patient Level Information and Costing System (PLICS) and was first proposed in 2016 and is being implemented now across the health care system. The motivation for PLICS is that other costing methods are unable to answer the most important questions such as:

Which health care pathways produce the highest value and for which patients?

How do you set limits on variation in clinical care practices when you don’t know what variation in costs and patient outcomes results from them?

How could you assess the benefits of new models of health care delivery without knowing the value each is delivering? (HFMA, 2022[16]).

PLICS data are collected from many different streams of patient-level and service‑level data throughout the health care system and require an IT system and common data standards that are integrated with the local systems of health care providers (NHS, 2022[17]). NHS England has already collected pilot statistics of PLICS in several care areas including acute care and mental health care and intends to move fully to PLICS for all areas of care in 2022.

Norway has introduced bundled payments recently but has not yet tied them to outcomes directly although this is part of a long-term plan. In the United Kingdom (England), a system of best practice tariffs had been introduced several years ago to incentivise health care quality, although they were not tied to patient reported outcomes. The best practice tariff was typically a base rate with additional incentive payment conditional upon performance. The tariff incentives were not significant enough, in light of the complex reimbursement system in the United Kingdom, to have a significant impact on performance (Gershlick, 2016[18]). It will be interesting to see how the PLICS system will contribute to the value‑based payment system in the coming years.

The precursor to value‑based payments were systems of pay-for-performance (P4P) which arose in the early 2000s across many OECD countries. These P4P methods were appealing in concept but were hampered in practice by inadequate inputs, particularly inadequately available and integrated patient-level health data including outcomes of care. As a result, many were unable to demonstrate significant improvements in health care quality (OECD/WHO, 2014[19]). Nonetheless, broader positive impacts from the development of P4P occurred including improved dialogue and agreement among payers and providers regarding the shared goal of health care quality improvement.

Korea is in a strong position to begin working toward measuring valued-based care because of its existing data infrastructure and the potential evolution toward an integrated health information system. The Korean single‑payer model provides an established basis for calculating patient-level costs of care. HIRA could build partnerships with health care providers interested in value‑based care to develop measurement systems and then, in collaboration with the NHIS, pilot test bundled payments with financial incentive bonuses for higher value health care pathways. Such pilot tests should be accompanied by the design of comprehensive evaluation frameworks to ensure that if the payments are tied to improvements in outcomes of care that these improvements can be clearly detected.

A solid data infrastructure can supply multiple purposes, it could for example enable prospective resource allocation that is based on, and adjusted to, health and social need. An enhanced, needs-based resource allocation model covering the entire population has been implemented in Spain. The model is based on Morbidity-Adjusted Groups (Grupos de Morbilidad Ajustados – GMAs). The goal was to transition from a disease‑centred to a patient-centred model of health care delivery, by identifying individual health needs and implementing needs-based models of care and resource allocation (see Box 3.4).

Box 3.4. Grupos de Morbilidad Ajustados – GMAs

The GMA system stratifies the entire population into 31 distinct GMAs. A complexity index is calculated for each person based on analysis of past resource use variables. Each morbidity group except the healthy population is stratified into 5 complexity subgroups. In addition, a label is assigned to each person with information on the most relevant diseases, from a list of 80 prioritised health problems. Data come from EMRs of primary care providers and hospitals and from claims. Every insured person (about 99% of the population) has a unique ID, which allows for data linkage and inclusion of the entire population of each autonomous region.

GMAs serve a variety of purposes. These include designing specific models of care and supporting clinical decision-making in primary care. At the system-level, GMAs are used to predict demand and to set needs-based budgets, determine payments for medicines, health workforce planning, as well as public health monitoring and identifying people to include in epidemiological and clinical studies.

GMAs have been found to accurately predict parameters that are relevant for needs-based planning and resource allocation, such as primary care visits, unplanned hospitalisations and pharmaceutical spending per patient. Policy makers report satisfaction with the ease of use, the versatility of the system for multiple purposes, and in some cases the indirect effect the implementation has had on coding practices by health professionals and data quality.

Source: OECD (2019[20]), Health in the 21st Century: Putting Data to Work for Stronger Health Systems, https://doi.org/10.1787/e3b23f8e-en.

Korea can build on its unique strengths

This section outlines the many strengths and advantages of the current Korean health system. These strengths can be built upon to develop a world-leading, modern health information system. Korea performed well compared with OECD countries in many aspects of health data maturity, use and governance in the 2019‑20 OECD survey discussed in Chapter 2. In most cases, the data needed to achieve an integrated health information system and fulfil the government’s policy objectives exist. All that is needed are a set of consistent rules to connect actors in the information system together and to enable access to the right data by the right people at the right time. The strengths of the Korean system are technical, regulatory as well as political, with a solid track record of major health system reforms.

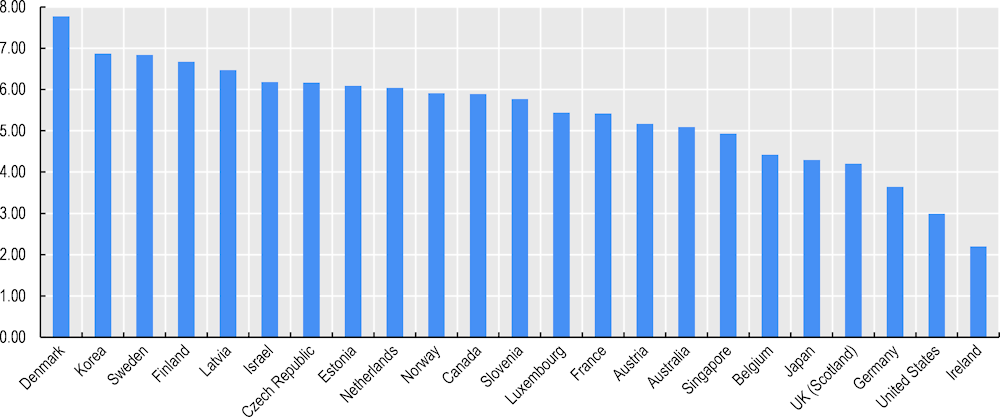

Korea has good health data availability, coverage, and governance

For example, Korea reported all but 1 of 13 important datasets in 2019/20 (inpatient data, mental health inpatient data, emergency care data, primary care data, prescribed medicines data, cancer registry data, diabetes registry data, cardiovascular disease registry data, mortality data, long-term care data, patient experience survey data, population health survey data, and population census or registry data). Korea performed well on the maturity and use of these data assets based on their availability, coverage, automation, timeliness, unique identification, coding, data linkage and regular reporting of indicators of health care quality and system performance (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Korea ranks highly on health dataset availability, maturity and use, 2019‑20

Note: Score is the sum of the proportion of health datasets meeting 8 key elements of dataset availability, maturity and use in this survey. The maximum score is 8.

Source: Oderkirk (2021[5]), “Survey results: National health data infrastructure and governance”, https://doi.org/10.1787/55d24b5d-en.

Korea stands out for having a very short time lapse, of one week or less, between when a data record is first created and when it is included in the national dataset used for analysis for most key national datasets. Korea also was 1 of only 7 countries that reported having a unique patient/person identifying number that could be used for record linkage within 90% or more of their national health datasets.

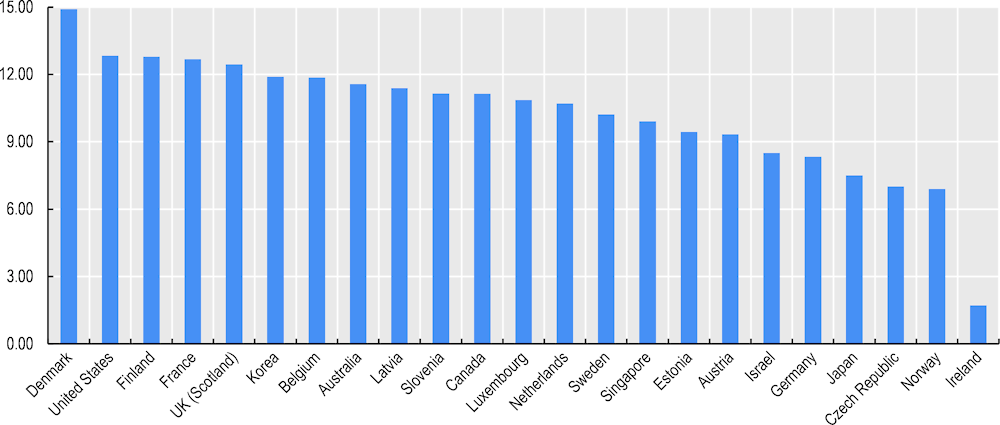

Korea is also among the countries with the strongest data governance across 10 key national health care datasets considered in the 2019‑20 survey based on the following elements: legal authorisation dataset creation, privacy/data protection officers, staff training in data protection, data access controls, data de‑identification, testing for re‑identification attack risks, data sharing within the public sector, data sharing with academia, data sharing with for-profit sector, data sharing across national borders for multi-country research, standardised data sharing agreements, remote data access or research data centre services, and public communication regarding health datasets and their legal basis and requirements to request access to data and to be approved access to data (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Korea compares well on national health care data governance

Note: The score is the sum of the proportion of national health care datasets meeting 15 governance elements. The maximum score is 15.

Source: Oderkirk (2021[5]), “Survey results: National health data infrastructure and governance”, https://doi.org/10.1787/55d24b5d-en.

Korea has a strong track record of health reform and adaptation

Recent reforms demonstrate that Korea has the capability to plan and implement major structural reforms in the health system, overcoming internal and external resistance. This is perhaps the biggest strength to draw on when creating a data infrastructure for the 21st century.

Creating a single payer system

Prior to 2000, the Republic of Korea’s national health insurance system consisted of more than 350 quasi-public health insurers. There were three types of health insurance schemes that were subject to strict regulation by the Ministry of Health and Welfare: health insurers for employees and their dependents, numbering more than 100; a single health insurance society for civil servants, teachers, and their dependents; and over 200 health insurers for the self-employed.

There was little competition among health insurers with enrolees assigned to insurers based on workplace or residential area. Despite identical statutory benefits, contribution rates differed across insurers raising concerns about equity (enrolees in poor or rural areas paid a greater proportion of their income). Risk-pooling/sharing mechanisms across insurers based on demographics and catastrophic medical expenses were introduced, and insurers with a higher proportion of the elderly and greater burden of catastrophic expenditures were cross-subsidised by others. Nevertheless, many insurers continued to face insolvency through structural inequities and inefficiencies that government interventions could not address.

The reform to merge all health insurers into a single payer in 2000 increased efficiency, improved equity, and reduced administrative costs in the system.

But it was not an easy journey. The National Assembly passed legislation to merge all insurance funds in the early 1990s, but the President vetoed the law mainly due to budgetary concerns that a single payer could increase the government responsibility for financing health care. It wasn’t until 2000 that a new government successfully implemented this major policy reform. Civil society were instrumental in the reform process.

Separation of drug prescribing and dispensing

Prior to 2000, physicians and pharmacists both prescribed and dispensed medicines. This system provided strong financial incentives for over-prescribing drugs with higher profit margins. As medical service fees were strictly regulated, dispensing was a sought-after revenue stream. As a result, Korea had comparatively high proportion of total expenditures on pharmaceuticals.

Physicians and pharmacists favoured the status quo as they wanted to keep the right to prescribe and lobbied successfully to block reform. With the active support of civil society, the government successfully separated separating prescribing from dispensing in 2000.

This resulted in a series of nationwide strikes by physicians, leading to weakening some of the elements of the reform package. The government agreed to increase medical fees to compensate for foregone medicines-related revenues resulting from the reform. The dramatic increase in physician fees, as much as 40%, contributed to a fiscal crisis in the national health insurance system when its accumulated financial reserve was exhausted in 2001 (Kwon, 2007[21]).

Responding to pandemics (MERS and COVID‑19)

As part of its response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Korean Government has approved temporary projects that promote using real-time data across key elements of the health care system. Although strictly for pandemic management and population health and separate to the Korean Digital New Deal (see below), these initiatives further illustrate what is possible in Korea with sufficient political will and social license. For example, daily reports are produced on the status of key resources and resource use to guide the health system to deliver care (geographic distribution of patients, the use of treatment wards (ICUs), and the current supply and allocation of key medical supplies (PPE) and medicines).

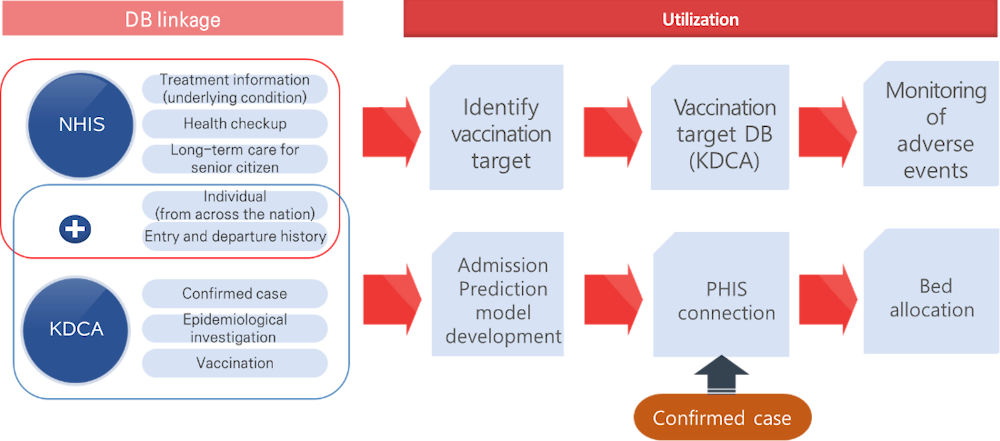

NHIS provides priority vaccination targets using the NHI eligibility and treatment data. NHIS also developed prediction scores for severity level of COVID‑19 confirmed cases by linking COVID‑19 data (confirmed cases, epidemiological investigation, and vaccination) of KDCA with the National Health Insurance Big Data (underlying condition, health checkup, Long-term Care data, etc.). The severity prediction score is added to the Public Health Information System (PHIS) and used for epidemiological investigation and bed assignment. Regarding COVID‑19 oral antiviral Paxlovid, NHIS identified those who requires caution when prescribing the medicine (see Figure 3.5).

Korea also developed an International Traveller Information System (ITS) after the MERS outbreak and is using the system to manage COVID‑19. The ITS is part of the Drug Utilisation Review (DUR) platform, which was outlined previously (and is discussed later in this chapter). The ITS provides real-time data about travellers entering Korea from higher risk countries to health care providers and pharmacies through a patient status checking system so that they may be prioritised for testing for SARS-Cov‑2. Patient data are also linked with databases outside of the health system to track and control disease spread by tracking the movements of individuals who test positive for the virus through credit card usage records and mobile phone GPS, and publicly sharing information about travel routes and locations visited. While this poses privacy concerns, Korea has maintained public support for its pandemic response and has avoided lockdowns, strict stay at home orders and entry bans for foreigners (You, 2020[22]).

Figure 3.5. NHIS data efforts to manage COVID‑19

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from NHIS.

Not all reforms succeeded

In 1997, the government began the pilot programme for case‑mix funding based on Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) for five disease categories for voluntarily participating providers. The government planned to extend the payment model system to all health care providers in 2000, alongside the above financing and pharmaceutical reforms. However, following doctors’ strikes against the pharmaceutical reform, the government decided to give up on nationwide implementation of the DRG-based payment system. Nevertheless, continued efforts with phased-approach resulted in full implementation of DRG at all providers across the nation.

The Korean Digital New Deal

The Digital New Deal is one of the four components of the Korean New Deal initiative aiming to accelerate the digital economy and this initiative highlighted the importance of citizen-friendly data including data gathering, processing, exchange and use. Under the Digital New Deal, real-time insurance claims data should be linked with real-time clinical data. For example, Korea is developing the capability to monitor adverse events from the COVID‑19 vaccination in real time. In response to COVID‑19, the Ministry of Health and Welfare and HIRA have been working together with the international community in sharing COVID‑19 data (see Box 3.5).

As a first step, the government is collecting scattered health sector data into a data lake, which the government plans to use to 1) provide lifestyle‑related guidance to the public using personal information and community care, 2) pseudonymise the data and proactively open the data for researchers in the private and public sectors, to lead the transition to a digital economy. Legislation has been prepared to allow public bodies and private companies to have access to the data lake. Korea aims to link additional repositories to this national initiative. Korea plans to maintain the data lake after the pandemic ends so it may continue to support international researchers’ access to updated COVID‑19 patient data. De‑identification techniques such as pseudonymisation are being used as a safeguard, and qualified organisations will perform data preparation. Engagement with the data lake is by application to qualified agencies (Magazanik, 2022[23]).

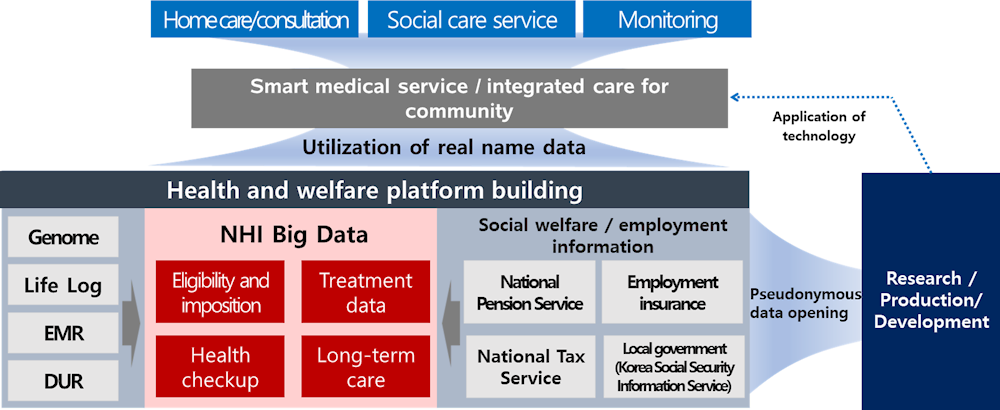

The objectives of the New Deal include creating “smart medical services and caring service infrastructure and opening and using data in the fields closely related to people’s lives.” To build smart medical service and community care infrastructure, MoHW is establishing smart medical service infrastructure at hospitals and promoting smart health management and a virtual community care project. The My Healthway platform will consolidating and connecting genome, treatment history (clinical data), health insurance data.

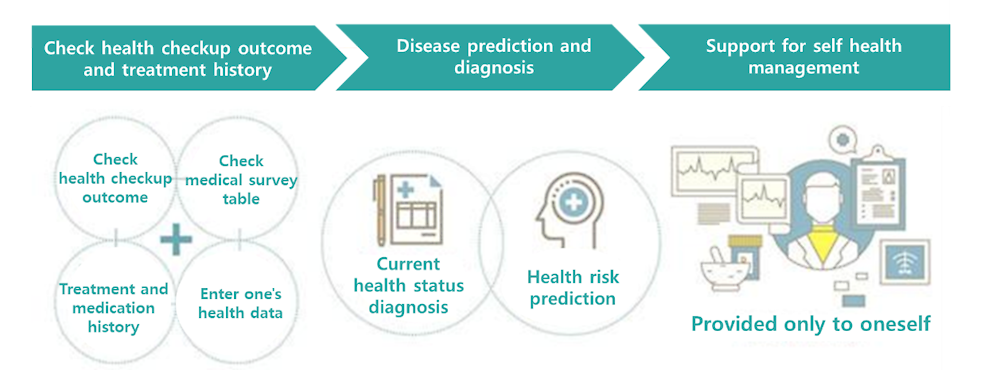

NHIS is consolidating data from 42 organisations for operation of the National Health Insurance and the National Long-term Care Insurance, along with data shared by KDCA, Ministry of Environment, and Ministry of Labour. The data lake consisting of the consolidated data is not only open to the public but also providing services for the public. To realise the digital New Deal and support economic activity, NHIS is opening access to the data lake to the private‑sector. Previously, access was only granted for policy and academic purposes. However, access to data for private insurance companies is still under discussion due to different opinions. Data are increasingly accessible to health service industries, including AI, precision medicine, disease prediction model development, health index development, etc. Private‑sector applicants may be approved access to heterogenous linked data that have been pseudonymised (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6. MyHealthway platform

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from NHIS.

Box 3.5. The “H New Deal” Project

HIRA has taken on the responsibility to implement the digital new deal in the health system (the H-New Deal). The key areas of focus will be creating a digital health ecosystem that promotes an integrated patient health record (My Health Way), enables Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools development, co‑ordination of medical services at a glance, practical assistance for Korea Government’s response (COVID‑19) and (importantly) industry-academia and government collaboration. The centrepiece of the scheme will be the HIRA data platform.

The H-New Deal is expected to benefit society, government, academia and industry. The benefits for patients and citizens will include:

Secure access to personal medical information for individuals and for sharing with their health care professionals, i.e. My Health Way,

Quick response to national health crisis by digital health care resources co‑ordination,

Prevention of patient harms/better safety,

Value through reduction of medical expenses and improvement of health care quality,

Expanding medical access for vulnerable people, and

More convenience through providing digital health care services in real-time.

The project began in 2021 and implementation of all components is expected to show results in 2023.

Source: Material provided to OECD Secretariat by HIRA.

National health insurance agencies should play a central role in these advances. NHIS is the custodian of patient-level data, including the National Health Insurance, medical resources, health checkup, Long-term cares service, etc. In particular, NHIS is building a state‑of-the‑art data platform, which facilitates a favorable environment for data collection, utilisation, and access. In addition to the elements outlined in the Box above, HIRA is well placed to play a fundamental role in the Digital New Deal by providing hub or platform for secure and efficient data exchange. The experience of the DUR and ITS, as well as the pilot PROMs data collection and the value‑based review and assessment project (see next section) gives HIRA a solid grounding to perform fundamental functions.

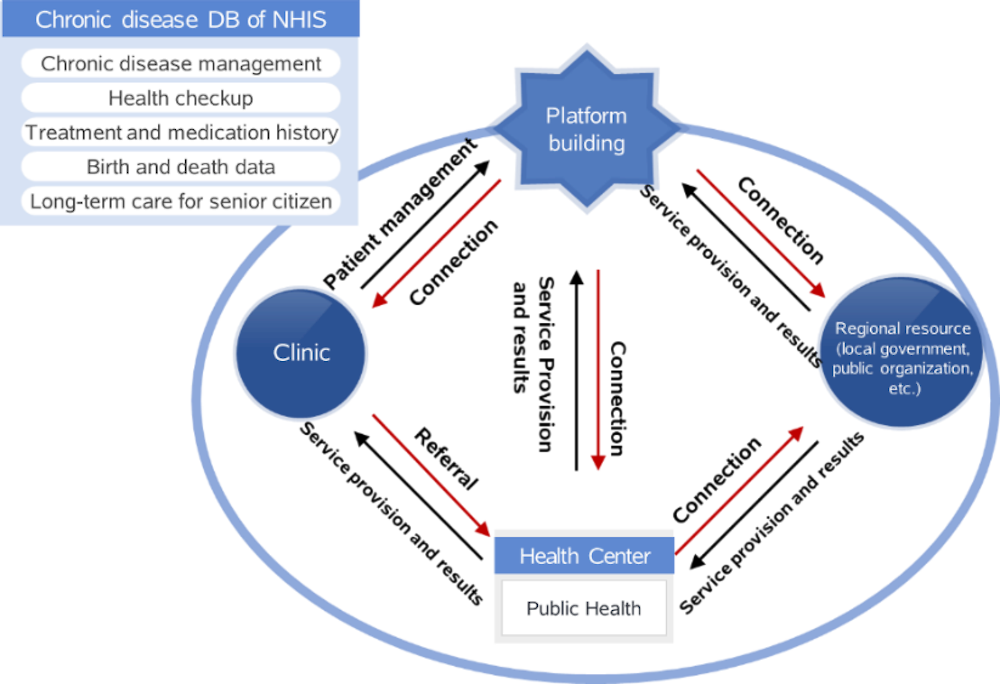

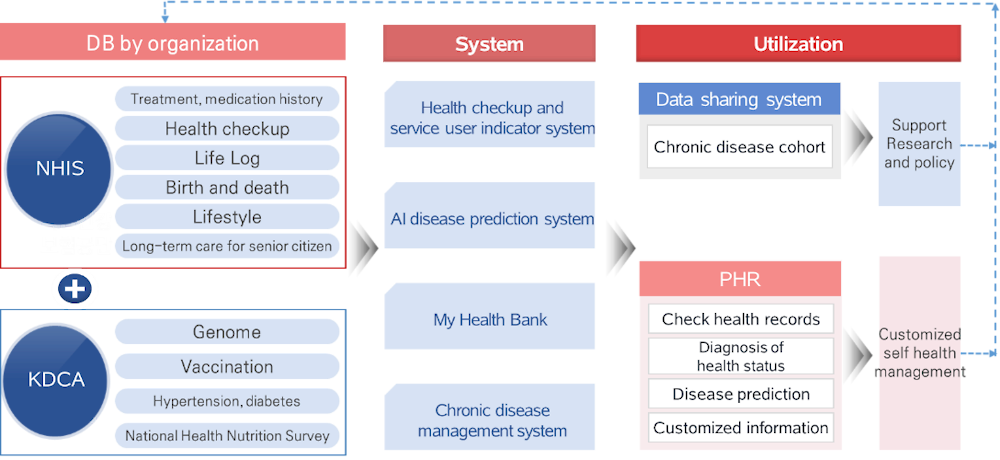

NHIS is building integrated services for chronic disease patients

Korea is attempting to build a comprehensive chronic disease management system by integrating personal health data scattered data across organisations. KDCA has built health behaviour and chronic disease management status data based on the annual national nutrition survey. NHIS has benefit claim data, lifestyle data such as drinking, smoking, and exercise, and actual measurement data from health check-ups.

NHIS analysed its own data to produce condition management indicators including indicators of risk factors, metabolic syndrome, and chronic diseases and complications by small scale region and workplace. The Chronic Diseases Management Registration Program (Figure 3.7) is a public data platform that collaborates with primary care providers to collect and accumulate chronic disease patient data (medical measurement and health management behaviour). My Health Bank contains medical consultation results (personal information, disease history, and complications), physical examination (blood pressure, etc.) clinical tests (blood sugar, etc.), and self-tested data (blood pressure, blood sugar, number of steps, etc.). It supports individuals to manage their health risk factors, and helps policy makers set up tailored measures for their region.

Figure 3.7. NHIS chronic diseases management registration programme

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from NHIS.

Using the Patient Management System, NHIS provides feedback on chronic disease patients’ health management status and supports patient management and outcome improvement activities by sharing monitoring results (structure, process, outcome) by regions. The system helps improve chronic disease management indicators, supports individuals to manage risk factors by themselves based on customised diagnosis information, and supports policy makers to come up with the right solutions for the region. About 460 000 patients are receiving chronic disease management services from this system. Over 5 years, the “diabetes medication adherence rate in 1 year” rose by 5.02% to reach 63.11%.

KDCA and NHIS are attempting to build a national chronic disease management system by connecting the National Health Nutrition Survey and the health check-up and medical treatment system, which is expected to revolutionise the chronic disease monitoring system (Figure 3.8). Previously, NHIS and KDCA have exchanged and connected data for one‑off policy analysis and research projects.

Figure 3.8. National chronic disease management system

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from NHIS.

HIRA is transitioning towards a value‑based assessment and monitoring framework

Through its role in quality assessment and monitoring, HIRA has been able to achieve improvements in several important medical activity. For example, rates of antimicrobial prescribing for viral upper respiratory infections reduced from 73% in 2002 to 38% in 2019. The number of drugs per prescription have reduced from 4.3 to 3.7 over the same period. Meanwhile, antibiotic administered within 1 hour of surgery has increased from 24% to 90%.

More specifically, HIRAs deliberate transition towards a value‑based claims assessments, as well as its Benefits Information Analysis System and the Drug Utilisation Review (DUR) illustrate the possibilities of using routine data to promote continuous learning and performance improvement in Korean health care.

Towards a value‑based claims review and assessment

The current transition by HIRA towards a more nuanced way to assess and review claims that aims to maximise value (as opposed to minimise costs) is also encouraging. This is part of broader reforms to make services covered by the NHI more patient-centric and evidence‑based. Whereas in the past, claim assessments were normalised based on average costs, the new approach builds in the distinct characteristics individual providers and their patients, based on a more detailed assessment of data.

The review process is also being made more transparent. Previously, claims were finalised by an internal committee. Now, clinical experts and academic groups participate in the process through a Professional Review Committee (PRC). A Special Review Committee (SRC) works with HIRA to develop clinical guidelines, standards, and indicators to monitor performance. A broader Review System Operation Committee was established to include providers, experts, and citizens/patients in how the process is designed and overseen.

In short, the previous process accepted or adjusted the benefit paid based on standardised amounts on an item-by-item basis. The new approach is a more comprehensive judgement that considers the local context, quality of service and treatment outcome. It also includes expert participation by providers and academics, creating a “virtuous cycle” of learning development of indicators, fine‑tuning standards and developing indicators that inform continuous learning.

HIRA links health data with other data to provide information for policy, practice and patients

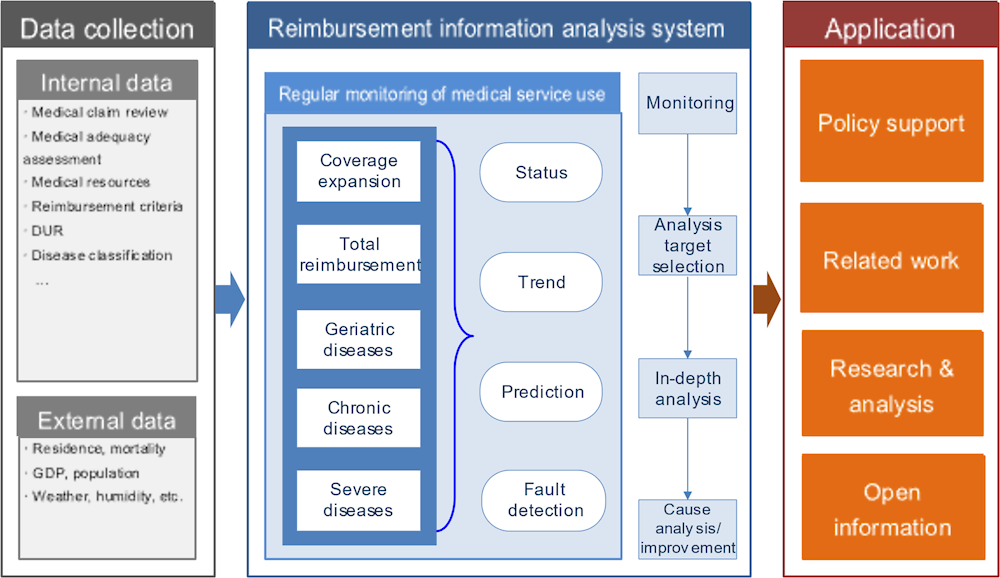

The Benefits Information Analysis System already demonstrates many of the principles and requirements described in the previous chapter of using existing data to promote continuous learning and improvement. The Benefits Information Analysis System draws on claims and other data held by HIRA as well as data held by Statistics Korea and the Korean weather service to analyse trends in the frequency and costs of medical interventions both within and outside the NHI coverage (Figure 3.9). According to HIRA, the aim is to:

prevent unnecessary medical service use by identifying causes and preparing policy measures through medical service use analysis conducted from user and provider perspectives, and

ensure the provision of essential medical treatments and prevent unnecessary financial expenditure to create a sustainable medical environment.

The Benefits Information Analysis System monitors actual use of services and resources against modelled, expected trends for a range of specific diseases (e.g. thyroid cancer), interventions (e.g. MRI scans), and populations groups (e.g. over 75s). The analyses are used to detect of abnormal trends in service provision, generate statistics to promote public health (e.g. heat-related illnesses in summer, fractures/falls in winter), and inform policies (and their evaluation) to guide sustainable coverage expansion. The initiative has driven several successful outcomes.

Figure 3.9. The Benefits Information Analysis System uses various data to support policy, research and public information

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from HIRA.

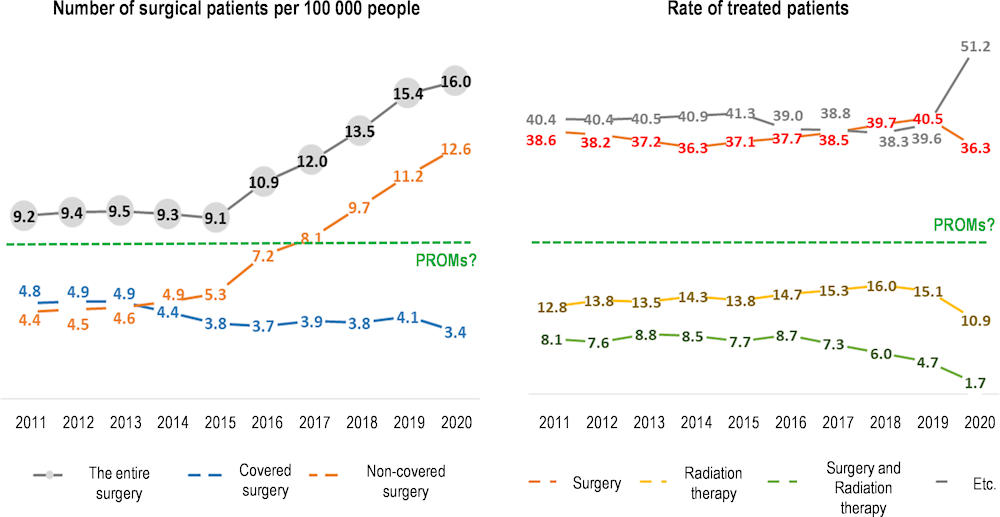

For example, data collected during suggested that MRI was over-used in stroke patients over 2019. Corrective action included meetings with providers and specialist groups where the clinical standards were updated. This resulted in a reduction in MRI use in line with expected rates based on population and cerebrovascular disease trends. In another example, monitoring on thyroid cancer treatment from 2011 to 2020 confirmed the change in treatment pattern, as total thyroidectomy fell, and partial removal and nonsurgical treatment increased.

Analysis of prostate cancer intervention rates over the same period showed a rise in non-covered items (robotic surgery) with a parallel reduction in covered services including radiation and surgery. Rates of non-covered items could be inferred because they generate a hospital admission, which is covered and therefore generates a NHI claim (the NHIS plans to begin collecting data on non-covered items beginning in late 2022 – see below). This may require policy intervention because it is not clear if robotic surgery, which is more expensive, produces superior outcomes. In fact, collecting patient-reported outcome metrics (PROMs) would enable policy makers, providers and patients to ascertain the relative value of these procedures, and provide feedback on performance (if patient-level data could be shared with providers) (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10. Data on prostate cancer intervention rates can be complement with PROMs data

Source: Material provided to the OECD Secretariat from HIRA.

The DUR can be expanded to provide real-world evidence on safety and performance of technologies

The DUR is a prospective, real-time review of drug prescriptions to minimise the risk of harm such as contraindications, drug/drug interactions or ingredient duplication. It uses data held by HIRA to provide the advice and alerts. A review of the DUR found that it has lowered the prescription of counter-indicated drugs and lowered pharmaceutical expenditures by reducing over-utilisation of drugs (Lee, 2019[24]).

HIRA hopes to add the another utilisation of DUR to alarm each person’s side‑effects based on patient’s allergy records. To proceed, the information accumulated by only hospitals needs to be integrated with DUR. The system would be even more useful for clinical decision making if it included information about patient-level diagnostics, pathology, and test results and if this was accessible within hospital and clinic EMRs. For example, for patients with renal failure it would be helpful for clinicians to have guidance from DUR regarding the dosage and how it corresponds to patients’ creatinine levels from their lab test results. But for the DUR to be expanded to include dosage and pathology results, the data collection of HIRA must be expanded to include clinical, pathology and prescription data. If this expansion occurred, then the DUR could offer more nuanced recommendations.

For medical professionals and pharmacists to use DUR to its fullest potential the DUR advice should be integrated into the clinical workflow to support clinical decision-making. This would require DUR to use global clinical terminology standards that align with the national standards recommended by the Korean Health Information Services (KHIS), including clinical terminology standards, for example SNOMED-CT and LOINC, and data exchange standards (HL7 FHIR).

A world-class post-market surveillance system

Moreover, Expanding the DUR to include the following data sources could transform it to serve as a full drug safety information system, able to support regulatory decision making and post-market surveillance of drugs, assisting agencies such as the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS):

Patient-level diagnostics, pathology and test results,

Drug allergy information

Patient-level health care utilisation (claims),

Health outcomes including PROMs and mortality, and

Demographic, social and environmental data.

An example of such a system is the Sentinel Surveillance System of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) where routinely collected data, particularly data from electronic medical records (EMRs) and insurance claims are used to support drug approval and post-approval surveillance and research (see Box 3.6). Further the FDA Sentinel is expanding to include surveillance of medical devices.

The FDA Sentinel System uses a distributed federated network and a CDM to query data of health care providers while preserving the data within the custody of health care providers, thereby enhancing the protection of health data privacy. Korea has recently invested in the coding of both hospital data and health insurance claims data to the OMOP CDM as part of the OHDSI project, a distributed federated research partnership, which constitutes the groundwork for moving to a privacy-protective sentinel surveillance system.

Box 3.6. United States FDA Sentinel Initiative