The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region is characterised by its high vulnerability towards extreme weather events and climate disasters, as well as its richness in biodiversity and abundant natural resources. LAC countries have developed and are implementing National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). Yet more needs to be done to manage increasing risks from climate change and climate variability. Based on the discussions in a series of Regional Policy Dialogues and Workshops on these issues among LAC and OECD experts in the context of the OECD LAC Regional Programme (LACRP), this chapter maps challenges to addressing climate change adaptation in the LAC region and presents options on policy initiatives that could be undertaken to this end.

Towards Climate Resilience and Neutrality in Latin America and the Caribbean

2. Achieving climate resilience in the Latin America and Caribbean region

Abstract

Introduction

The LAC region is highly vulnerable to climate change. It is considered one of the top disaster-prone regions in the world, with the average number of extreme climate-related weather events increasing by 62% in the LAC region during 2001-2022, when compared to the period 1980-2000 (OECD, 2023[1]).

Climate events are already impacting ecosystems, food and water security, human health and poverty as well as urban areas, agricultural productivity, hydrological regimes, coastal livelihoods, and biodiversity (Figure 2.1). LAC countries are facing serious challenges when protecting vulnerable populations and ecosystems. High climate change scenarios – with high levels of uncertainty on the physical impacts of climate change and local adaptation policies – estimate that 5.8 million people will fall into extreme poverty between 2020 and 2030 in the LAC region, increasing the average poverty headcount by more than 300%, when compared to a no climate change scenario (Arga Jafino et al., 2020[2]). Such impacts may vary between LAC countries and sub-regions, as there are large differences on the natural disasters and climate change impacts at the local level, as well as on the impact to the local population.

Figure 2.1. Key socio-economic and environmental impacts in LAC

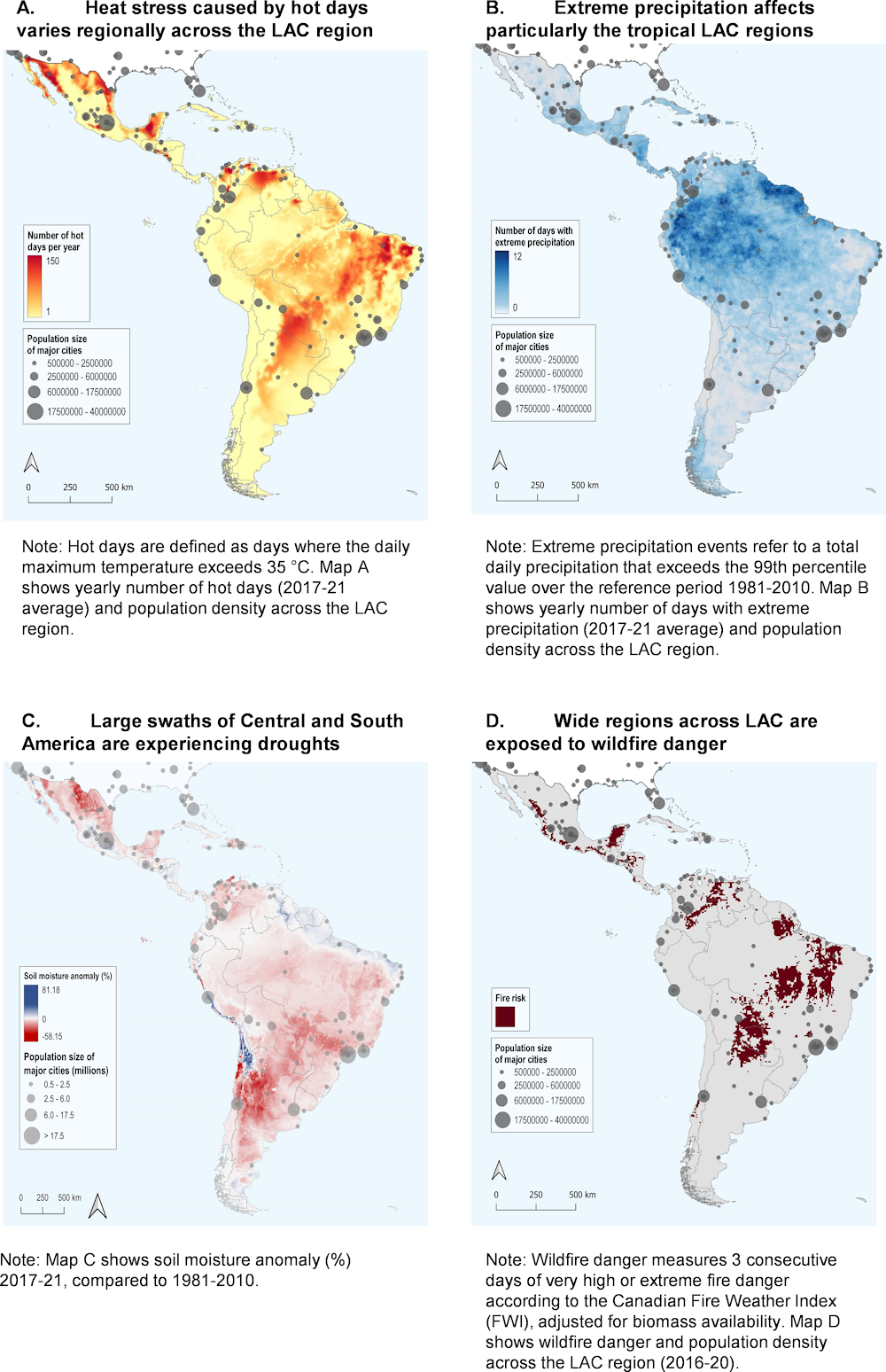

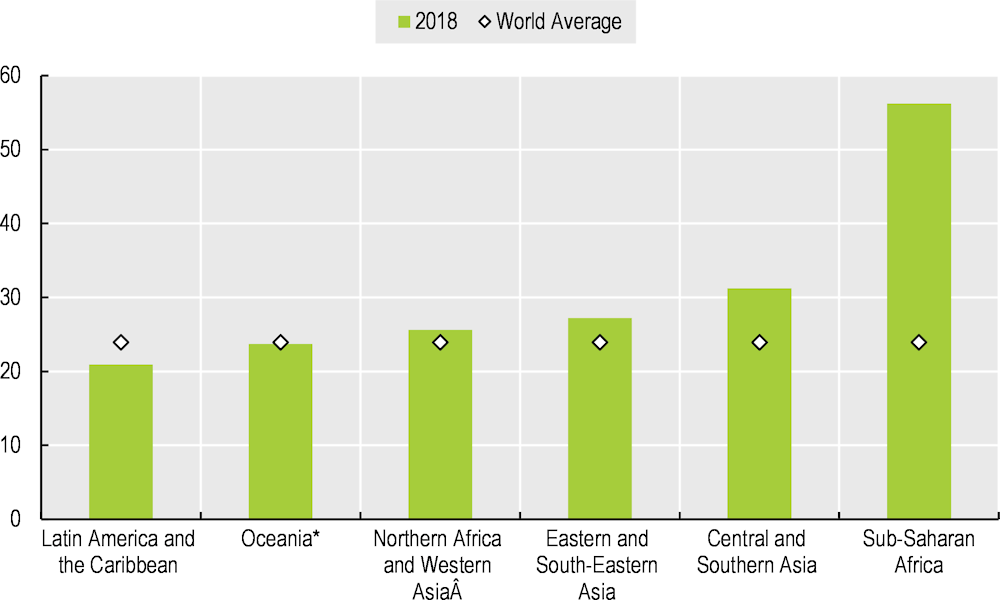

Data show that population in the LAC region is increasingly exposed to heat stress from hot summer days (especially in Paraguay and El Salvador), extreme precipitation (such as in Suriname, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago), droughts (Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil), wildfires (Jamaica, Paraguay, Mexico and El Salvador), wind threats (Caribbean), river flooding (Suriname, Guyana, Argentina) (Figure 2.2; Figure 2.3); (OECD, 2023[1]). The region is also particularly vulnerable to biodiversity loss, as many of the economic activities in LAC are linked to natural resources and the quality of ecosystems, such as tourism and agriculture (OECD, 2023[1]).

Figure 2.2. Climate-related hazards in Latin America and the Caribbean (1/2)

Source: (Maes et al., 2022[7]), “Monitoring exposure to climate-related hazards: Indicator methodology and key results”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 201, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/da074cb6-en.

Figure 2.3. Climate-related hazards in Latin America and the Caribbean (2/2)

Source: (Maes et al., 2022[7]), “Monitoring exposure to climate-related hazards: Indicator methodology and key results”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 201, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/da074cb6-en.

Between 1970 and 2021, South America accounted for 3% of globally reported deaths, with floods being the leading cause of reported deaths. These disasters resulted in USD 115.2 billion in economic losses (WMO, 2021[8]). In total, 17.1% of the 11 933 climate‑related extreme weather events registered worldwide between 1970 and 2022 occurred in LAC (OECD et al., 2022[3]). Furthermore, the impacts of climate change are unevenly distributed, with vulnerable communities, including women and children, indigenous peoples, and poor households, often bearing the highest impacts.

The climate change impacts are extensive as they concern vulnerable populations, especially children. In LAC, approximately 169 million children live in areas where at least two climate and environmental shocks overlap and 47 million children, or 1 out of 4, live in areas impacted by at least 4 shocks. Furthermore, about 55 million children are exposed to water scarcity, 60 million are exposed to cyclones, 85 million are exposed to the Zika virus, 115 million children are exposed to Dengue fever, 45 million children are exposed to heatwaves and 105 million are exposed to air pollution (UNICEF, 2021[9]). Hurricanes in the Caribbean, for instance, destroy critical infrastructure for children’s well-being and development, such as schools and health facilities. Floods can damage homes, compromise water and sanitation facilities, contaminate drinking water sources, and contribute to the spread of diarrheal diseases, which disproportionately affect young children. Additionally, vulnerable families are forced to migrate due to shocks and scarcity of water and resources. In 2020, weather events internally displaced 2.8 million people in LAC (UNICEF, 2021[9]).

Vulnerabilities to climate change are having direct impacts to national and local economic development and economic sectors in the LAC region. Argentina is already experiencing the climate impacts to agricultural economic activities (Straffelini et al., 2023[10]); (Müller, Lovino and Sgroi, 2021[11]). For Mexico, the present value of crop yield changes, due to high temperatures and precipitation, is estimated at about USD 40 million, twice the national agricultural production of the country in 2012 (Estrada et al., 2022[12]). Peru has estimated the cost of inaction against climate change at between 11%-20% of its gross domestic product (GDP) until 2050, and habitat loss around 9% until 2050 and 22% until 2100 (OECD, 2023[13]).

The LAC region is also highly sensitive to climate system tipping points, i.e. possible catastrophic events that could occur because of current levels of global warming, even if the Paris Agreement targets of 1.5oC and 2oC are achieved. For LAC the tipping elements expected to manifest as changes in the climate system are the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet; the dieback of the Amazon Forest; as well as the El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Atlantic overturning collapse. Tipping of one of these elements – as well as others occurring in other parts of the globe – could potentially trigger tipping cascades, with global impact (OECD, 2022[14]). Climate tipping points would have further effects on socio-economic systems, as forest loss, rising sea-levels, and damages to infrastructure would impact people’s livelihoods and health.

Such challenges require urgent action in adapting to climate change and increasing resilience at the regional, national and local level, as well as integrating adaptation policies and tools to sectoral policies, economic instruments and innovative solutions, including those based on nature or new technologies. Actions to adapt to present and future impacts of climate change would need to be accompanied and aligned with strong mitigation measures, to avoid the worst of global warming (see Chapter 3). This chapter focuses on the challenges discussed during a series of Regional Policy Dialogues in 2023, involving LAC and OECD experts. The analysis is not exhaustive, as it focuses on the points highlighted as a priority for LAC countries during the discussions.

LAC contributions to the international framework for climate change adaptation

Reaching the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), as set out in the Paris Agreement (UN, 2015[15]), is a priority for LAC countries. Setting the road to reaching the goal is also important and requires countries to assess their strengths and weaknesses to better respond to the impacts of climate change (Climate Analytics, 2021[16]). At the twenty-sixth United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26), countries agreed to create a comprehensive two-year Glasgow–Sharm el-Sheikh work programme to address the GGA. The programme emphasises the importance of country-driven, gender-responsive, participatory, and transparent approaches to adaptation action. It considers vulnerable groups, communities, ecosystems, and is guided by the best available science, as well as traditional and local knowledge. It aims to achieve objectives such as the full implementation of the Paris Agreement, enhancing understanding of the GGA, and contributing to the review of overall progress through global stocktakes. It also focuses on improving national planning and implementation of adaptation actions, facilitating communication of priorities, plans, and actions, and establishing robust monitoring and evaluation systems (UNFCCC, n.d.[17]).

In January 2021, the Adaptation Action Coalition was formed with the objective of accelerating global action on adaptation to achieve a climate resilient world by 2030. Out of the 33 LAC countries, 8 are now part of the coalition: Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia, Jamaica, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay (Adaptation Action Coalition, 2022[18]). Finally, the Glasgow Climate Pact included a goal for developed countries to double the funding provided to developing countries for adaptation by 2025, which would represent USD 40 billion for adaptation. It also recognised the critical role of restoring nature and ecosystems in delivering benefits for climate adaptation (UNEP, 2021[19]).

During the twenty-seventh UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP27), countries approved the Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, which included the decision to create a Losses and Damages Fund with over USD 230 million in new pledges. The fund aims to assist developing countries affected by extreme climate change events. It also encourages countries to consider Nature-based Solutions (NbS) for their mitigation and adaptation actions. Additionally, countries approved the institutional arrangements to operationalise the Santiago Network, a portal which links international organisations, experts and bodies with regions, countries and communities that wish to minimise and address losses and damages from climate change. The Santiago Network catalyses technical assistance, and it should be fully operational by the twenty-eighth United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP28). The United Nations unveiled a USD 3.1 billion plan to ensure universal coverage of early warning systems within the next five years. However, countries did not define the GGA, instead established a framework for its formulation to be considered and adopted at COP28. Finally, the Sharm El-Sheikh Adaptation Agenda was launched at COP27, aiming to accelerate transformative solutions through system interventions and achieve a set of adaptation outcome targets by 2030 (Adaptation Action Coalition, 2022[18]); (UNFCCC, n.d.[20]); (Carver, 2023[21]).

At a regional level, LAC adopted the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean known as the Escazú Agreement, the first environmental agreement in LAC and the world’s first legally binding instrument to include provisions for environmental human rights defenders (UN, 2018[22]). The agreement was adopted in Costa Rica, on 4 March 2018 with the objective to ensure the full and effective implementation of rights related to environmental information access, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice in environmental matters. It also focuses on capacity building, co-operation, and the protection of the right to a healthy environment and sustainable development. Currently, 25 of the 33 LAC countries invited to participate are signatories to the Escazú Agreement. Even though the Agreement has entered into force, implementation requires technological, human-based and NbS, as well as a high level of transboundary collaboration and co-operation on environmental management (López‐Cubillos et al., 2021[23]); (UN ECLAC, 2023[24]).

LAC is the second most disaster-prone region in the world. Managing increasing risks from climate change and climate variability is a growing need in the region. The adoption of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030 (Sendai Framework) and the Paris Agreement has resulted in the need to expand coherence in countries’ approaches to climate and disaster risk reduction. Nationally, countries have spread the responsibilities regarding climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction across different institutions and stakeholders, while internationally they are supported by separate UN agencies and related processes resulting in overlaps and gaps. However, countries have been recognising the benefits of increased coherence. They have been increasingly integrating the two concepts, by developing joint strategies or putting in place processes that facilitate co-ordination across climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction. There is also a need to ensure that some enabling factors are in place, including strong leadership and engagement of key government bodies, broad stakeholder participation and co-ordination, clear allocation of roles, responsibilities and resources, and monitoring, evaluation and continuous learning. These elements can support the identification of trade-offs and synergies, while minimising redundancies (OECD, 2020[25]).

The LAC region has unevenly reported on indicators of the Sendai’s Framework. LAC has notably reduced global disaster mortality and increased the number of national and local disaster risk reduction strategies, as well as expanded international co-operation to support their national actions for the implementation of the Sendai’s Framework. Nevertheless, LAC still needs to enhance efforts to substantially reduce the number of affected people to the impacts of climate change and reduce its direct disaster economic losses in relation to GDP. Additional efforts can be made to reduce disaster damage to critical infrastructure and the disruption of basic services, as well as with respect to increasing the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk information and assessments to people (UNDRR, 2022[26]).

Linking climate change to biodiversity loss is well-engraved in the international framework, both through the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The CBD fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP15) in 2022 highlighted once more the interconnectedness of climate change and biodiversity loss. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), adopted at CBD COP15, includes four goals to 2050 and 23 targets to be achieved by 2030, including a target for minimising the impact of climate change and ocean acidification on biodiversity, through NbS, ecosystem-based approaches and climate action on biodiversity. Beyond climate change and fundamental to climate resilience, the GBF includes other targets for safeguarding biodiversity and ecosystems, such as to effectively conservate and manage at least 30% of the world’s lands, inland waters, coastal areas and ocean; to progressively phase out or reform subsidies that harm biodiversity by at least USD 500 billion per year; to scale up positive incentives for biodiversity, and to cut global food waste in half and significantly reduce over consumption and waste generation (CBD, 2022[27]).

Snapshot of National Adaptation Plans in LAC

NAPs provide a policy tool for countries collecting, developing, adopting and implementing adaptation actions. They serve as a framework, under which countries aim to reduce vulnerability, derived from climate change, strengthen their resilience and increase their adaptive capacity. The development of a NAP has also proven to be a much-accepted process, through which countries align their adaptation actions with other international frameworks and goals, such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs.

Since 2010 up until 2022, only 36% (12 out of 33) of LAC countries had submitted their NAPs under the UNFCCC process. A few LAC countries have adopted national legislation or policy frameworks on climate adaptation or resilience, while the majority have preferred introducing general legislation or frameworks on climate change. Several LAC countries are also including adaptation considerations in sectoral or other specialised legislation or plans (Annex A). However, overall, there is still a gap between introducing a national plan or framework on climate adaptation, and implementing it. LAC countries are identifying the following major challenges in strengthening their national adaptation pathway: difficulty in aligning the objectives and priorities identified in NAPs with sectoral and sub-national development plans; defining and securing the budget for implementing the NAPs; and ensuring the availability of country-wide, downscaled information on projected climate change impacts.1 Evidently, only 12% (4 out of 33) of LAC countries have already submitted sectoral NAPs and other outputs, such as a monitoring and evaluation strategy or a communications strategy, supporting implementation (Annex A).

NAPs are not the only tool available for countries wishing to advance with setting and implementing climate adaptation policy measures and actions. Countries are also including climate-resilient or climate adaptation policies in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) or their Long-Term Strategies (LTS) (Annex A). Despite the fact that all LAC countries have submitted and updated their NDCs, only a few have made progress on their adaptation actions included in their NDCs, and even fewer have submitted or updated their LTS (World Bank, 2022[28]); (NDC Partnership, n.d.[29]). In any case, what is important is to guarantee that policies introduced are aligned with contributions to international targets and national environmental commitments. There is also a need to examine trade-offs and complementarities with sectoral and non-climate policies and to build on synergies with climate mitigation measures. Frequently updating the NAPs and other national plans and strategies related to climate adaptation and based on evidenced-based analysis on global warming, tipping points, and losses and damages, such as provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the OECD, could help countries to adjust their climate measures and actions to reflect the rapidly changing environment.

Recommendation

Develop and progressively update National Adaptation Plans submitted to the UNFCCC, and support their implementation through robust legal and regulatory, institutional and financial frameworks.

Aligning adaptation priorities with national commitments and addressing adaptation needs with national policies.

LAC countries are identifying climate change adaptation as a key policy priority for the region. To successfully address the issue, specific climate adaptation actions need to be identified by countries. Several LAC countries have introduced legislation or action plans and roadmaps with specific climate adaptation actions, either under the general climate change policy framework or through sectoral non-environment related policies and strategies, building on the interlinkages between the effects of climate adaptation with vulnerability, economic growth and development (Annex A).

Countries follow differentiated policy approaches, to accommodate national circumstances, vulnerabilities and needs, not allowing direct comparability between the policy options selected. This is especially the case in the LAC region, which is very diverse in terms of economic growth, social development, geography, distribution etc. Irrespective of the particularities in different countries and sub-regions within the LAC region, there are some principal considerations to be taken into account when developing legislation, policies and actions that address climate change adaptation:

Align national and local adaptation priorities with countries’ commitments. In many cases, LAC countries have been introducing policy frameworks and legal instruments to reach their pledges towards internationally determined adaptation targets, with clear assignment of responsibilities between national, sub-national and local stakeholders. In the case of Peru, for example, the framework law on climate change establishes not only objectives, but also processes on governing climate change programmes and projects, with special attention paid to cross-cutting actions, which involve different stakeholders throughout the country (OECD, 2023[13]). Paraguay is prioritising specific environmental sectors for action under its NAP and has also set up a plan for its operational implementation (Box 2.1).

Align mitigation and adaptation priorities, to safeguard balance between the two aspects of climate change. Climate mitigation has long received more attention and prioritisation, in both international negotiations and national decision-making, as well as through financing and investments. Measuring the impact of mitigation measures has much advanced, especially since greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated from human activities are being calculated, and their decoupling from economic growth is advancing (see Chapter 3). However, measuring vulnerability to climate change and the effects of the often-unprecedented climate phenomena, and quickly updating adaptation policies and aligning them with mitigation measures remains a struggle. Argentina has a legal framework and governance structure overseeing both mitigation and adaptation, also measuring the effectiveness of the measures adopted (Box 2.1).

Mainstream adaptation considerations in sectoral policies. Addressing climate change requires not only climate action, but also alignment of various policy domains, such as finance, taxation, investment, infrastructure, trade, innovation etc, with climate goals (OECD, 2015[30]). Aligning legal, regulatory and policy frameworks, currently outside the climate policy portfolio, with climate objectives requires a series of commitments and possibly acceptance of short-term trade-offs, which would provide for a more sustainable policy framework in the long term.

Box 2.1. Aligning priorities to address climate change adaptation

Paraguay’s prioritisation for climate adaptation

Paraguay has set climate change adaptation as a national priority, with measures introduced in the NDC, NAP and national strategy. In its NAP 2022-2030, Paraguay has identified seven key sectors and has set 25 objectives with the aim to increase resilience at the local and national level in these sectors. The sectors identified are i) resilient urban and rural communities; ii) health; iii) ecosystems and biodiversity; iv) energy; v) agriculture, forestry and food security; vi) water resources; and vii) transport. The objectives set are aligned with the SDGs and the Sendai Framework. The operational implementation of the plan is also introduced, emphasising the roles and links between national and sub-national levels of governance, and setting up a monitoring and evaluation system.

Argentina’s plan on climate mitigation and adaptation

In December 2019, Argentina introduced a Law (No. 27520) on climate change, which sought to establish minimum environmental budgets that guarantee actions, instruments and strategies for adaptation and mitigation to climate change, in line with the country’s commitments. The law makes provisions for setting up a National Plan for Adaptation and Mitigation to Climate Change, which should cover, among others, i) identifying vulnerabilities and short- medium- and long- term adaptation measures; ii) developing climate scenarios based on vulnerability and socio-economic and environmental trends; and iii) establishing monitoring and evaluations processes of measuring the effectiveness of policy measures and actions adopted. It also sets up a governance structure, headed by a National Cabinet of Climate Change, responsible for monitoring the application of legislative provisions, and supported by an External Advisory Council which consults on a permanent basis on the National Plan. Argentina also recently launched a National Climate Finance Strategy, mainstreaming climate adaptation in financing policies.

Legal certainty and targeted planning over climate adaptation policies can provide a solid ground to accentuate action for climate change adaptation. However, advancing the implementation of adaptation measures requires a more holistic approach, which covers other challenges that several countries, including in the LAC region, are facing:

Firstly, implementing the NDCs and NAPs requires a balanced and people-centred approach for the adaptation measures pursued to benefit local communities, indigenous people and vulnerable groups, and benefit from their knowledge in addressing climate adaptation. For example, in the case of Peru, 84 adaptation measures have been identified to date, with a special focus on early warning systems, actions to address public health issues and strengthening capacity in fishing and agricultural sectors (OECD, 2023[13]). The successful implementation of these measures highly depends on location and the incorporation of local communities needs in the solutions proposed.

Secondly, financing must be secured to be able to implement specific policies and advance the adaptation agenda. Often in LAC countries, the measures proposed are not tied to specific budget lines. In some cases, measures’ implementation depends on financing mechanisms, such as the Global Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund, and their role in mobilising resources on adaptation. Introducing more creative financing tools – namely micro-insurance on green bonds, green taxonomies, climate risk incorporation in financing processes – could also help transform good adaption proposals into bankable projects, with the involvement of the private sector (OECD, 2023[13]).

Thirdly, capacity building is needed. Building critical skills in public administration to be able to identify adaptation projects which are suitable for financing, and which could be implemented is necessary to advance climate adaptation. In parallel, enhancing national and local capacities to develop climate-related project ideas which consider private sector engagement, local stakeholder acceptance and promote resilience in various sectors, would secure the viability of solutions proposed.

People – Environmental Justice – Communities

Climate change is a global phenomenon, yet it has local impacts. Solutions to climate change adaptation need to be inclusive of local communities and address local vulnerabilities. This applies both in urban and rural areas, which may vary in morphology, vulnerabilities to different climatic and weather events, productive activities that drive the local economy, and therefore local well-being.

Early warning and civil protection systems in LAC

There is a close link between the interventions for climate change adaptation and for disaster risk reduction. These policy areas often share common goals towards increasing resilience, such as protecting communities and infrastructure from the impacts of natural hazards, and minimising losses caused by disasters. They also face overlapping risks, whereby increasing and more intense climate hazards increase the disaster risks and impacts. Increased coherence between the two policy areas, through co-ordinated action between all relevant stakeholders could help improve policy interventions, (OECD, 2020[25]) and support a climate risk-informed local development.

Early warning systems (EWS) are acknowledged as a key element of disaster risk reduction, which aim at supporting people to adapt to climate change and build resilience. Even though EWS have been characterised as a “low-hanging fruit” for adaptation, being an efficient and effective way to protect people, their application requires several prerequisites to reach success. These concern mainly people-centred technology development and transfer, data management and forecasting, enabling innovation, and guaranteeing sustainable funding for constant updates in technology. The UNFCCC launched in 2022 a Rolling workplan of the Technology Executive Committee for 2023-2027, highlighting the need for further collaboration to support accelerated action in innovation and technology development for the wide application of EWS. The Executive Action Plan for the Early Warnings for All presented during COP27 identifies key areas for advancing universal disaster risk knowledge, prioritises the top technical actions to enhance capacity on data and information collection, and sets the ground for aligning and co-ordinating financing instruments to scale-up investments for EWS (WMO, 2022[34]).

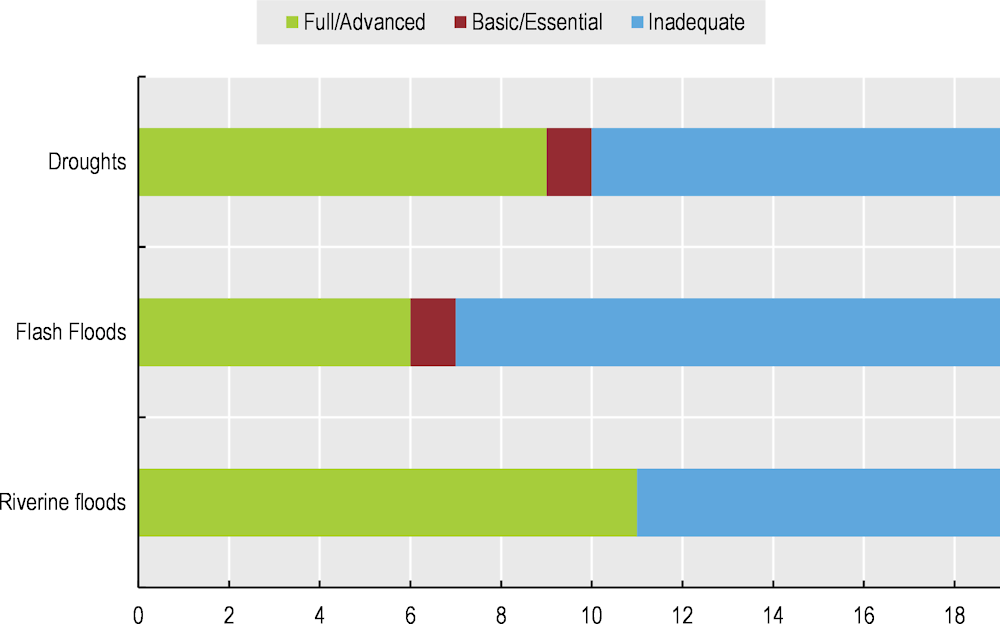

EWS are mentioned in over 60% of NDCs submitted by LAC countries, highlighting the need to address climate change phenomena and extreme weather events, as well as reduce water and food security risks. Due to the multiple types of hazards occurring in the region, Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems (MHEWS) are considered essential tools to address high risks from weather, water, and climate extremes. Yet a recent report from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) shows that, despite LAC countries facing vulnerabilities ranging from droughts to floods, to landslides, sea-level rise, storms and hurricanes etc, they are also facing early warning capacity gaps. In fact, from the 19 LAC countries that responded to the WMO survey, at least 8 countries have inadequate EWS in place for riverine floods, flash floods and droughts (Figure 2.4). A closer look at the LAC countries shows that the major needs in the region are disaster risk knowledge; detection, monitoring, analysis and forecasting, and disaster preparedness and response. Warning dissemination and communication is also an issue for South America (WMO, 2020[35]).

Figure 2.4. Early Warning System capacity in LAC countries

Island States in the Caribbean have been frontrunners in developing their EWS, due to the region’s high vulnerability to various natural hazards (hurricanes, floods, droughts, forest fires, volcano eruptions and earthquakes). With the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), International Federation of Red Cross (IFRC), Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) and Cuba, islands such as Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, Saint Lucia and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines applied the Cuban Early Warning Systems Toolbox, which offers tools and activities that countries could undertake to improve their risk knowledge, monitoring and warning systems, dissemination and communication, and response capacities. The programme also included technical trainings, test runs for newly installed meteorological forecast products, a regional measurement tool for monitoring of progress, and information sharing, to spread the lessons learned more broadly in the region (Gazol, 2019[36]).

In addition to EWS, mechanisms to manage the aftermath of extreme weather events or other climate-related hazards are also necessary. The urgent need for primary healthcare, shelter, food, water, sanitation and basic relief items requires appropriate disaster preparedness at the national and local levels, with co-ordination mechanisms set in place and sufficient funding for emergencies. In the medium and long-term, building resilient infrastructure could also help adapt to such events; while investing more on ecosystems’ preservation could increase resilience against natural hazards (see below).

Several LAC countries, such as Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela, have established civil protection mechanisms to address risk management, preparation and prevention activities, together with co-ordination on emergency and reconstruction systems. Most of these countries have clearly prioritised co-ordination between different government levels for better civil protection, as well as set up funds which cover, among others, natural or climate-related disasters. However, there are still gaps in managing natural disasters, as well as accessing the financial resources available in case of a climate emergency, or even in-kind supplies for the needs of those affected. To overcome such challenges, better co-ordination of actions between different government levels, and dedicated sufficient financial resources to support both risk reduction and emergency response for climate change are needed (Szlafsztein, 2020[37]).

When introducing EWS, or other climate risk reduction mechanisms, considering the particularities of vulnerable groups is key to increasing resilience. Indigenous people, displaced persons, persons with disabilities, rural communities, the elderly, women and children are experiencing differently any social, economic, cultural and environmental change. If not taken into consideration, this could result to increasing inequalities, exacerbating existing ones (Box 2.2). Active collaboration with vulnerable groups can provide additional information on local climate hazards and weather events and assist in prevention and preparedness for local communities. In the case of Costa Rica, active and effective engagement with indigenous communities allows their voices and proposals to be taken into consideration for better early warning. Additional investment in climate-resilient infrastructure and capacity building for responding to such phenomena, would further help improve EWS (OECD, 2023[38]).

Box 2.2. Gender-responsive actions to climate disaster risks in LAC

Climate hazards are not gender-neutral events. Their impacts vary based on gender roles, access to resources, income and other intersecting social identities. Women are usually the ones evacuating last during an extreme weather event, due to their care-giving responsibilities over children and elderly. They are also often less trained on preparedness and response to an extreme weather event. Finally, they may experience less access to information or less capacity to receive and act on early warnings, because of lack of education and illiteracy or lack of technical training. These characteristics apply also to the LAC region.

Transforming climate disaster risk reduction policies and EWS mechanisms to be gender-responsive requires:

Collecting gender-disaggregated data and setting gender-sensitive indicators. Antigua and Barbuda, Chile, Costa Rica and Ecuador are already providing such disaggregated data form the monitoring of the Sendai Framework.

Including a gender perspective in climate risk governance. Increasing women’s participation in the decision-making processes would help raise their concerns in planning and in reducing vulnerability. Grenada is including women in the discussions at the stages of design, implementation and evaluation of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Investing in EWS and other mechanisms for climate resilience with a gender perspective. Often investments targeting climate-risk reduction are lacking a gender or inclusiveness perspective, thus missing the opportunity to address inequalities, or even exacerbating them. The Climate Risk Early Warning Systems (CREWS) Caribbean project prioritises investments that support EWS developed with the participation of local communities, including women.

Providing technical assistance, capacity-building and long-term multi-hazard preparedness. Acknowledging the differentiated impacts of climate disaster to women and men requires incorporating both groups in the preparedness and response interventions. Jamaica includes women in identifying high-risk areas and critical infrastructure that could be affected by a climate disaster. Peru supported financially female-headed households for reconstructing their communities after the 2017 floods.

Recommendation

Improve early warning systems to ensure that all people, especially those in communities at greater risk of climate-related extreme weather events in LAC, have access to vital information in real-time, at the individual level, and that local communities participate in the design and implementation of EWS.

Strengthen or create civil protection systems in LAC, which are equipped and prepared with supplies, trained personnel, infrastructure, and sufficient funds to provide immediate attention, shelter, and comprehensive medical assistance before, during, and after natural disasters.

Reducing vulnerability in urban areas

Urban areas and cities are inevitably gaining more traction in relation to climate change adaptation, as projections show that by 2050 two-thirds of the world population will be living in urban areas. Managing the impacts of this trend would require NAPs revisions, bringing to the forefront the role of urban areas and cities in addressing climate change adaptation.

The LAC region is one of the most urbanised regions worldwide. Despite the disparities between the different types and sizes of cities, it is apparent that many of them are struggling with similar problems such as urban growth, restrictions in urban planning capabilities, and lack of climate risk assessments, which could help identify the type of improvements necessary to combat climate change at the local level.

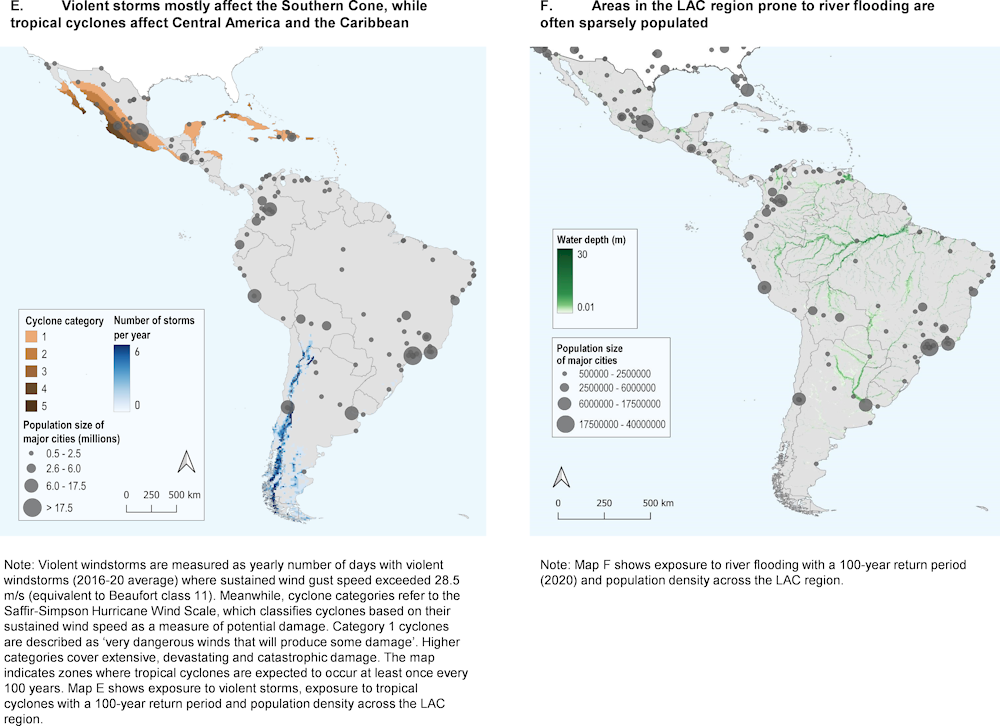

Almost 21% of the LAC urban population live in slums. Even though this percentage may be less than the world average, which is at 23.9%, it is still not acceptable, considering the residents’ living conditions (Figure 2.5). Slums in the LAC region are often affected by natural disasters such as landslides and floods, with the already limited infrastructure (water and sanitation services, electricity, transport and roads etc) being damaged and requiring upgrading (Fay et al., 2017[43]).

Figure 2.5. Percentage of urban population living in slums

Note: Oceania does not include Australia and New Zealand. World average at 23.9%.

Source: (UNSD, n.d.[44])

From the 12 LAC countries that have submitted a NAP, the majority include targets related to urban planning and land use, though different perspectives are presented. Chile links urban planning with biodiversity and ecosystems’ conservation. Costa Rica and Paraguay link it with green corridors in urban areas. Grenada and Saint Lucia present interconnection of urban planning with water resources. Uruguay refers to needed improvements in land use administration and data collection. Overall, there is limited local evidence of connection between urban planning and land use regulatory frameworks with climate risk assessments.

In the case of Caribbean Island states, the issue of urbanisation demands immediate transformative action. Caribbean Small Island Developing States (SIDS) face limitations in formal housing, rising haphazard settlement structures, and inadequate infrastructure for water and sewage treatment, and transport services. These challenges are further aggravated by climate change and extreme weather events in the Caribbean region. Caribbean SIDS are focusing their urban planning measures in NAPs on accessing water resources, expanding green spaces in urban areas, and tackling the effects of increasing migration from rural to urban areas. Mainstreaming climate change mitigation and adaptation into urban planning requires more than simple changes in urban development and land use. It requires improvements in data collection, in climate risk assessments, and in including local communities in the planning, design and development of sustainable infrastructure, as well as securing adequate financing for such works (Mycoo, 2022[45]).

An integrated approach, by which urban planning measures address climate adaptation and help build more climate-resilient cities is needed. Such an approach should include sufficient data collection and monitoring, risk assessment and risk management tools, as well as sufficient budget allocation. Assessing vulnerability at the local level, including local economic activities, would also help local governments improve their management and planning. International development banks and development co-operation agencies are actively supporting climate change adaptation at the local and city level in LAC. Focusing on information collection, monitoring and capacity building, they aim at strengthening resilient urban and local planning (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. International actors supporting resilient urban and local planning in LAC.

Strategic climate adaptation investment and institutional strengthening plans

The World Bank is supporting medium sized cities in the LAC region in developing Strategic Climate Adaptation Investment and Institutional Strengthening Plans for each of them. The exercise also included three assessments: on climate related risks, on institutional adaptive capacities, and on socio-economic capacities to adapt to climate change. In the cases of Castries in Saint Lucia, Cusco in Peru, Esteli in Nicaragua, El Progreso in Honduras and Santos in Brazil, the World Bank activities included mechanisms for data collection and better climate monitoring and risk planning; cross-scale integration of risk management practices; capacity building for local officials working on climate change planning and risk management; better budgetary allocations and private climate financing to build resilience; and a change in risk governance systems from disaster management to long-term risk reduction.

Multi-level governance and planning processes

The German Agency for International Co-operation (GIZ) is also working with LAC countries to improve multi-level governance, to strengthen planning processes and to include land use as a factor affecting several economic activities in the region, such as tourism and agriculture. A necessary part in GIZ projects is developing tools for data collection which allow for vulnerability analysis, as well as identifying strategic frameworks and adaptation models at the local level. For example, on water resources, the exercise not only limits at mapping water basins, but also includes the information in municipality plans for water use. At the same time, capacity building at the municipality level is necessary, to allow for better management and planning.

Source: (World Bank, 2014[46]); (OECD, 2023[13])

Recommendation

Align regional and urban planning with NAPs and promote an integrated approach to overcome the risk management, capacity and financing gaps.

Sectoral approaches to climate adaptation

Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure

Infrastructure is severely impacted by climate variability and extreme weather events, which may cause damage to buildings, roads and bridges, disruption to transport, water and electricity supply, and possible loss of businesses and people. Climate impacts will have implications on infrastructure investment needs, not only relating to cost but also in guaranteeing that new infrastructure is resilient (OECD, 2018[47]). At the same time, investing in resilient infrastructure has a multiplier effect for the economy, as it reduces the GDP losses (due to reduction of capital destroyed during natural disasters) (Fernández Corugedo, Gonzalez and Guerson, 2023[48]). It is therefore essential to reduce climate risks towards infrastructure, as well as to effectively manage trade-offs between risk minimisation and cost. Prioritising climate-resilient infrastructure is expected to improve both the reliability of service provision and increase asset life. Introducing adaptive approaches to infrastructure, using climate model scenarios, could also reduce uncertainties and risks in the future. Including other socio-economic changes in the analysis would genuinely help achieving climate resilience (OECD, 2018[47]).

Investment needs for infrastructure globally have been estimated at around USD 6.3 trillion annually between 2016 and 2030 (OECD, 2017[49]). Considering countries would have to expedite their actions to achieve their Paris Agreement goals of 1.5°C and 2°C, the infrastructure investment needs are expected to be even greater. However, annual investments do not even reach close to this amount. Only for G20 countries, i.e. the bigger infrastructure investors, estimates of annual investments fall short of the actual needs, emphasising the necessity to close the investment gap (Zelikow and Savas, 2022[50]).

Infrastructure investment needs in the LAC region by 2030 have been estimated at 3.12% of GDP, while from 2008 to 2019 average investment was only 1.8% of GDP (Brichetti et al., 2021[51]). To cover this investment gap and also guarantee that new investment will be resilient to climate change, the mobilisation of additional resources is required. Most of the climate finance mobilised by developed countries in developing countries is tied to climate mitigation projects (67% annual average for the period 2016-2020), while about 24%% covers climate adaptation projects. Despite an increase over the past few years in adaptation finance, the gap between mitigation and adaptation remains significant. Specifically in the LAC region, 74% of climate finance focused on mitigation, with the main targeted sectors being energy (25%), transport (11%) and water supply and sanitation (10.5%) (OECD, 2022[52]).

Increasing climate finance directed to adaptation projects is not only necessary to build resilience against climate change, but also to guarantee more inclusive and sustainable growth. Investing in climate-resilient infrastructure would help not only avoiding losses, but also reducing risks to existing infrastructure and safeguarding social and environmental benefits; the so-called “triple dividend” (Global Center on Adaptation, 2021[53]).

Investing in resilient infrastructure could reduce social inequality. It could provide better water and sanitation services in areas affected by drought, improve forest management with the inclusion of local communities, or improve living conditions in coastal areas. Sustainable infrastructure investment projects which are transparent and take into consideration the local circumstances and the needs of vulnerable communities in the planning, design and implementation phase, would better serve the recipient communities and recognise their expertise and traditional knowledge. Finally, assessing and evaluating the impacts of infrastructure projects with respect to the needs of the most vulnerable, from the investors’ perspective (public, private, multilateral, national, subnational), would help revise future prioritisation of investment decisions (Faria, Perutti and Villalba, 2021[54]).

Countries should also consider introducing climate adaptation considerations in investments traditionally financed under the mitigation agenda. Better aligning infrastructure investment planning and financing with long-term, low-emission, resilient and inclusive development pathways will allow for scaling-up energy, transport and industry infrastructure investments. Creating the enabling environment for climate-resilient infrastructure investment also requires alignment between short- and long-term prioritisation of projects, project-level assessment, and capacity building.

Yet, only a few countries around the world are already developing long-term low-emission development strategies, integrating climate considerations in infrastructure planning. In many cases, there is a need for capacity building towards planning, designing and assessing bankable infrastructure projects that are in line with climate goals, both short-term and long-term. Moreover, the approach needs to be holistic and not broken down between the different institutional authorities that may be in charge of infrastructure in different sectors. Whole-of-government planning can help avoid investments with conflicting climate impacts. Creating a 'pipeline’ of infrastructure projects, to streamline the process between project conception and financing can also help secure sufficient investment flows for climate-resilient infrastructure (Box 2.4) (OECD, 2018[55]).

Box 2.4. Climate-resilient infrastructure development in Saint Lucia

In the case of Saint Lucia, a Caribbean island which faces many climate-related challenges, long-term planning for infrastructure across different sectors is imperative. Saint Lucia is applying the following tools to benefit the most from climate-resilient infrastructure development:

1. A National Infrastructure Assessment that ensures economic, environmental and social needs are met in future infrastructure planning;

2. Strategic Infrastructure Planning in energy, water supply, wastewater and solid waste sectors; which analyses future changes in demand for these sectors in an integrated manner, taking into consideration the effects of tourist flows;

3. Aligning assessment and planning with the SDGs and the Paris Agreement, guaranteeing that the National Infrastructure Assessment prioritises measures included in the country’s NAP;

4. Cross-ministerial co-ordination under the National Integrated Planning and Programme Unit, which is responsible for defining the overarching vision, strategy and roadmap for the island’s infrastructure agenda.

Source: (UNEP, 2021[56]); Saint Lucia’s National Infrastructure Assessment – Case Study

Recommendation

Better align infrastructure planning, development, and investments with short- and long-term low emission, climate-resilient and inclusive development strategies at the national level.

Enhance an enabling environment for the development of climate-resilient infrastructure to limit vulnerability to climate damages.

Achieving climate-resilient water resources management and financing

Global warming, one of the symptoms of climate change, is expected to have uneven impacts on water resources around the globe, with rising frequency of both floods and droughts. Economic activities linked to industry, agriculture and infrastructure development also lead to deforestation and land degradation, phenomena which in their turn affect water sources. Protecting the water cycle and better managing water supplies is essential to address the negative effects on water resources (Rockström et al., 2023[57]).

The LAC region is not homogeneous in the impact of climate change to water resources. The region is both water-rich, being home to over 30% of the world’s freshwater resources, but also has arid and semi-arid areas affected by droughts, not to mention the glaciers in the Andes (World Bank, 2013[58]). While in many LAC countries extreme precipitation is an issue, leading to crops’ destruction, landslides etc., in others severe droughts and poor water availability and quality are more of a concern. Suriname, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago suffer most from extreme precipitation events, while Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil are the countries the most affected by droughts (OECD, 2023[1]).

Climate change adaptation has a severe impact on water resources in the LAC region, having a negative effect on biodiversity and ecosystems, as well as on the quality of life for local populations. Destruction of land, forests and ecosystems compounds water risks. In the LAC region, water that evaporates in the Amazon rainforest drives precipitation in most of the continent. Affecting that evaporation-shed, through continuous deforestation, will have consequences on rainfall in several LAC countries, including Argentina, Bolivia and Colombia (Rockström et al., 2023[57]). This interdependence needs to be considered when designing policies on water resources. Further research and data collection on such phenomena would help support policymaking.

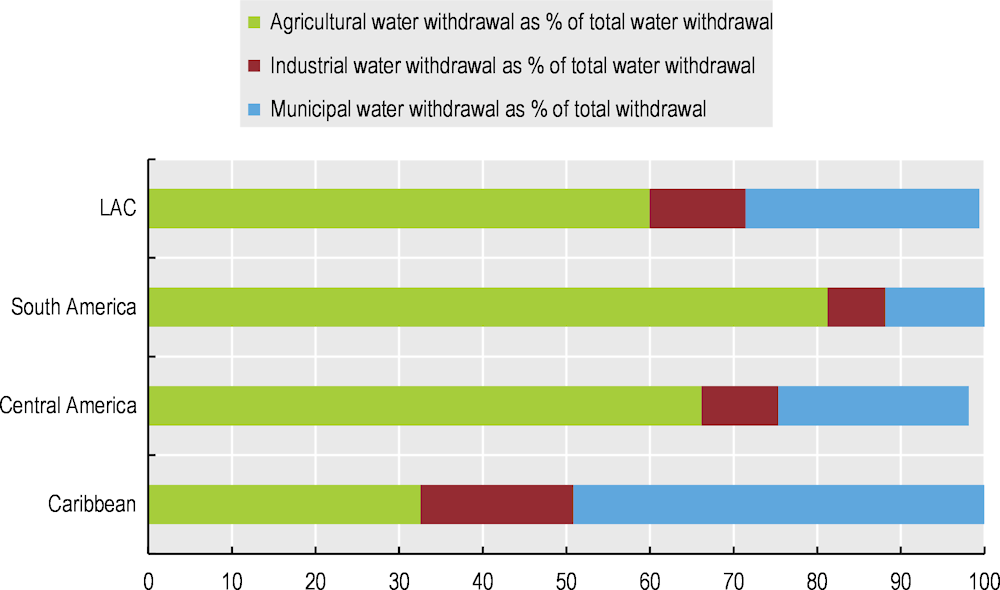

Agriculture is overall the major economic activity behind water withdrawal in South and Central America, with 81% and 66% of total water withdrawal respectively. For the Caribbean, about half of total water withdrawal is for municipal use (Figure 2.6). Water, however, is not an infinite source, therefore changes in economic activities, such as agriculture, energy and mining, will affect water allocation. The same applies in cases of increased water demand due to changes in demographics, where a sudden influx of population can create additional stress, especially in areas that suffer from restricted water resources.

Figure 2.6. Agricultural water withdrawal is high in Central and South America

Note: 2020 data. When water withdrawal in a sub-region does not total to 100, this is because of country data available in the AQUASTAT FAO database.

Source : (FAO, n.d.[59]) AQUASTAT dissemination system

Good water demand management is crucial for the region. Countries in Central America showcase the largest gaps in water resources management governance, with the main points missing being river basin management plans, financing instruments for water resources managements, and an integrated information system. In some cases, issues of overlapping responsibilities between different government institutions persist. In South America, institutional, legal, and management tools for water resources management do exist; however, challenges remain, often leading to fragmentation or gaps in water resources management (World Bank, 2022[60]).

Good water management requires a combination of water allocation regimes and economic policy instruments. Water allocation regimes could address issues of water scarcity. They set the process of sharing water resources among different water users, both long-term and short-term, while they may also incorporate seasonal adjustments, depending on cyclical events which impact water supply. LAC countries should reform their water allocation regimes, to better cope with future risks of water resources changes. In the case of Brazil, the OECD has highlighted three sets of measures to address existing weaknesses in water allocation. These could apply, with some flexibility and adaptation, to other LAC countries as well. Suggestions focus on (i) clearly defining available water resources and water use, and encouraging multi-purpose efficient use of water from reservoirs based on water use rights; (ii) introducing or revamping policy instruments such as water use permits with clear issuance criteria, and introducing pricing instruments to facilitate reallocation of water between users; and (iii) clarifying the water governance framework between national and local level, by improving monitoring and enforcement mechanisms for water allocation, strengthening capacity at the local level to better define priorities and plans, and include water users in the decision-making (OECD, 2022[61]).

Economic policy instruments signal the value of water. They can support the sustainable management of water resources, especially when considered together with water allocation regimes. They can also support managing water-related risks, therefore increasing water security, while reflecting externalities in water usage. Abstraction and pollution charges are such type of instruments already applied in some OECD countries. Mexico applies abstraction charges both for ground and surface water, for domestic, industrial, and energy production use. Chile’s allocation management regime allows transfer of water entitlements between users, so that water can be used for higher value uses (OECD, 2021[62]). Though the application of such charges may differ depending on target, tax base and structure, when introduced the following should be primarily considered (OECD, 2017[63]):

Water charges should be analogous to water use and water source. A good inventory of water users per water source can help set a fair water charge system, and could help frame exceptional cases for differentiated pricing, if needed.

Clear guidance on how to set and implement economic instruments, from the central government to the stakeholders involved in water resources governance and management, could help overcome capacity.

Economic analysis on resources management, affordability, effect of charges on competitiveness could help design more targeted water charges.

Transparency in the use of revenues from water charges will allow for better acceptance from local stakeholders. Reusing revenues to further finance improvements in water infrastructure would also help cover the potential financial gap that usually exists in water resources management.

Sustainable urban design could help mitigate flood and scarcity risk in urban environments. On average, about 5% of the population and 4% of the buildings in the LAC region are exposed to risks of river flooding, with Suriname, Guyana and Argentina showing the highest percentages of exposure in the region (OECD, 2023[1]). Reducing the effects of water-related events requires improvements in physical infrastructure, which in turn requires adequate financing and investment. The city of Cartagena in Colombia has set sustainable, resilient economic development as a target. A project aiming at stimulating resilient and sustainable innovations and generating investments for innovative and integrated urban water projects, is being launched. Analysis will cover the complete urban fabric from a physical, social, economic and cultural point of view. Local governmental and non-governmental stakeholders, ranging from investors to indigenous people, are participating in the process, from the analysis and design phase to the development of physical infrastructure (World Water Atlas, n.d.[64]).

Improving the operational performance of water supply and sanitation services can help both with enhancing the operational efficiency of the water management system, and with improving the services offered to the end-consumer. Water management in the LAC region faces low capacity challenges, often leading to technical gaps that hamper the quality of service provided and losses of revenue (World Bank, 2022[60]).Improving the operational performance requires strong, independent economic regulation, that sets performance standards, benchmarks performance of service providers, challenges investment plans, and sets tariffs that drive performance (OECD, 2022[65]); (OECD, 2022[66]).

Investing in a climate-resilient water sector can support efforts to achieve water security. Yet, undervaluing water resources is limiting financial opportunities in such investments. Accelerating finance for water in the context of adaptation requires enabling conditions to be in place. The OECD is developing a score card to assess whether these conditions are in place at national level (OECD, 2023[67]). The score card could be used across countries in the LAC region to review enabling conditions for financing water. In the region, international financing institutions and public development banks have a role to review these enabling conditions and promote alignment with practices than can accelerate finance for water and adaptation and minimise transaction costs.

Recommendation

Improve water demand management to tackle water scarcity and signal the value of water, through reformed water allocation regimes and better use of economic policy instruments.

Review the enabling conditions for water financing and sustainable investments in water security.

Biodiversity protection for climate mitigation and adaptation

Biodiversity loss and climate change are interlinked; both constitute threats towards the planet and peoples’ well-being, with negative impacts affecting especially the most vulnerable communities and groups. Climate change is one of the five key pressures on biodiversity loss (S. Díaz et al., 2019[68]); (IPBES and IPCCC, 2021[69]), and the loss of biodiversity (e.g. forest loss) is a contributor to climate change.

Biodiversity can also play a key role in limiting climate change. Ecosystems are natural carbon sinks, which can absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This is especially the case for LAC, one of the richest regions worldwide in biodiversity, with a large forest area, the Amazon, as well as a large ocean basin in the Caribbean Sea. At the same time, adaptation measures, such as restoring mangrove forests, can protect local communities from floods, as well as enhance ecosystems resilience. Due to the interconnectedness, fighting climate change should go hand in hand with minimising biodiversity loss, and vice versa. Acknowledging the interlinkages and mutually addressing the negative impacts would provide for optimal solutions. Maintaining biodiversity requires focused conservation and sustainable use efforts, co-ordinated action, and innovative solutions with strong adaptation characteristics (IPBES and IPCCC, 2021[69]).

Simultaneously addressing climate adaptation and biodiversity challenges, through an integrated approach, would be an opportunity for governments, especially in the LAC region, to address climate-related risks while at the same time building more resilient environments for local communities (OECD, 2021[70]); (UNFCCC et al., 2022[71]). Mainstreaming biodiversity considerations in economic sectors, such as forestry, agriculture and fisheries, can help address underlying causes of biodiversity loss (OECD, 2018[72]). Setting or reviewing existing policy instruments, such as economic incentives (e.g., taxes, fees and charges), and further promoting NbS, could help elevate biodiversity’s role in policy making.

Biodiversity conservation through protected areas and biological corridors

Connected and biodiverse ecosystems tend to be more resilient to the effects of climate change. The LAC region is one of the most biodiverse regions globally, with about 40% of the world’s species, 16% of the Earth’s forests, 40% of freshwater sources, and the second largest coral reef (The Nature Conservancy, 2021[73]).

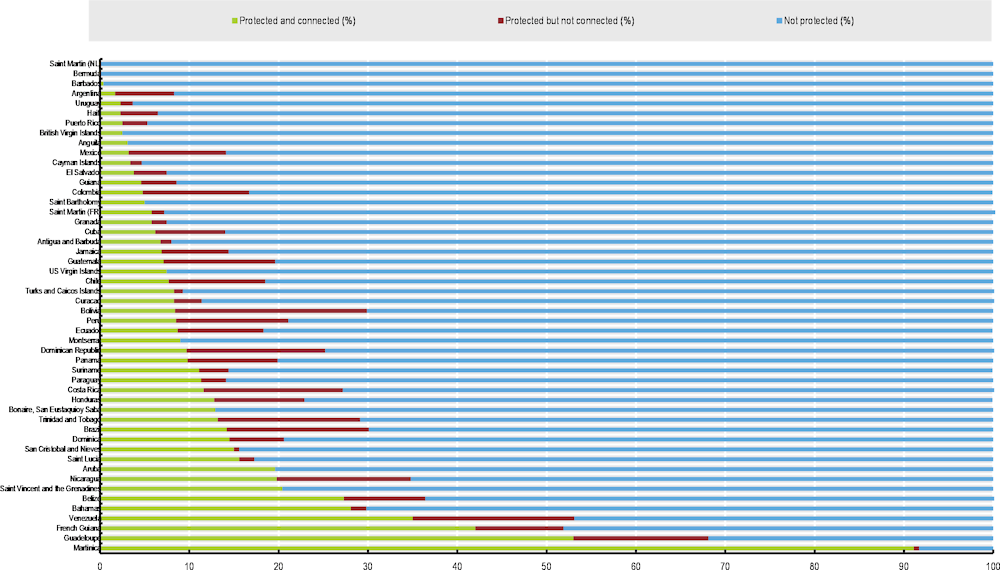

LAC is the most protected region in the world in terms of coverage (with the exception of the polar region) , and LAC countries have worked to increase the protected surface (land and sea) (Alvarez Malvido et al., 2021[74]). Yet, more efforts are required so that Protected Areas (PAs) are also representative of ecological biodiversity, and that there is sufficient connectivity between them. Such efforts would also help countries reach the CBD Kunming-Montreal global target 3 which calls for the effective conservation and management, though ecologically representative, well-connected and equitably governed systems of protected areas, of at least 30% of terrestrial, inland water, and coastal and marine areas (CBD, 2022[27]). Currently only nine countries in the region have over 17% of their protected area coverage connected, while on average 33% of PAs are not well connected (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7. Protected Areas in the LAC region

Despite efforts to increase PAs, especially by island states in the Caribbean, more needs to be done to guarantee biodiversity conservation in the LAC region. Connecting the various PAs, via biological corridors, and the adoption of Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) outside of protected areas, would help build better conservation methods in the future. Such efforts would require enhancing political commitment, engaging local communities who often have knowledge on local ecosystems, and securing necessary technical and financial resources to advance with holistic biodiversity conservation strategies (IPBES and IPCCC, 2021[69]).

Recommendation

Enhance connectivity of terrestrial and marine Protected Areas (PAs) as it is vital for the conservation of species.

Effectively protect, expand and maintain the biological corridors of Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, the Amazon, the Andes, and Patagonia, among others, to reverse degradation and restore the integrity of their natural ecosystems.

Mainstreaming biodiversity across economic sectors

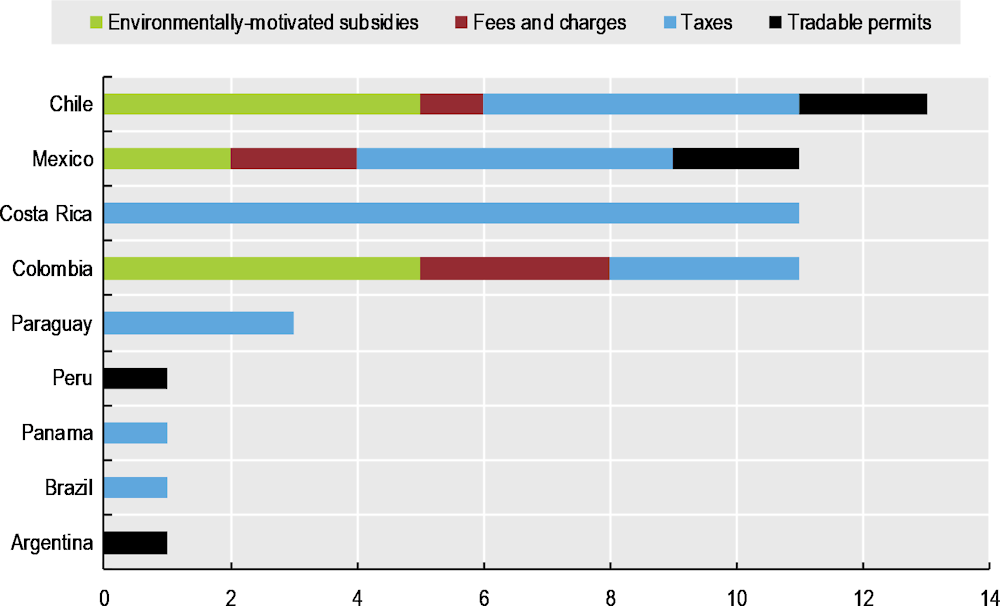

Mainstreaming biodiversity across different economic sectors can be achieved through economic instruments, such as taxes, charges, environmentally motivated subsidies, which provide positive incentives to shift to more sustainable behaviour and actions. In the LAC region, seven countries already have biodiversity relevant taxes in place, namely Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Panama, and Paraguay. However, only Chile, Colombia, and Mexico have introduced biodiversity-relevant fees and charges that is a payment by the payer to the general government for a good or service in return (such as a wastewater payment which varies based on the volume of water consumed). The same three countries have also introduced biodiversity-relevant environmentally motivated subsidies (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Biodiversity-related economic instruments in LAC countries

Recommendation

Establish policy instruments that regulate the use and intensity of use of natural resources, respecting the natural cycles and promoting the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and ecosystems services. These policies could include objectives of reducing ecosystems vulnerability and GHG emissions, thereby increasing resilience to multiple anthropogenic pressures.

Considering land use, biodiversity and climate change adaptation in agriculture

The LAC region has more than 30% of all forest globally, with high levels of vulnerability due to ecosystems’ degradation. At least 20% of the land of these ecosystems is destroyed and another 20% is severely damaged (OECD, 2023[13]). Key factors affecting land degradation in LAC are the expansion of large and small-scale agriculture and livestock, unsustainable infrastructure construction, the expansion of sprawled territories and (illegal) mining (UNCCD, 2019[76]).

LAC countries have incorporated Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) targets at national level, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals and the LDN initiative driven by UNCCD, while all LAC countries are a party to the UN Convention on to Combat Desertification. Even though degradation goals have been set, and there is also rich traditional knowledge on sustainable land management in the region, it is critical to better protect natural capital and strengthen resilience of ecosystems. Prioritising policy initiatives that serve such purposes will also help address climate change adaptation issues, considering for example the contribution of the Amazonian Forest in controlling global temperatures (UNCCD, 2019[76]).

Land degradation, together with droughts and excess precipitation, also severely affect the agriculture sector. Overall, about 14% of the LAC rural population, that is about 44 000 people, live on degraded agricultural land (OECD, 2023[13]), while in 2021 agriculture covered 15% of total employment in the region (World Bank, n.d.[77]). Climate events, such as landslides, wildfires, temperature increases, storms, droughts and floods, affect most agricultural regions and crops. In cases where such events decrease yields, as in the case of Argentina, the results are reduced agricultural economic activity and increased food insecurity (World Bank, 2022[78]).

LAC is world’s largest food net exporting region, as well as the largest producer of ecosystem services, being home to vast forests and savannahs that shape global weather patterns and mitigate climate change. LAC countries, whose GDP and exports highly depend on the agricultural sector, should prioritise land restoration and climate adaptation policies in agriculture and propose measures that will transform the food systems – going beyond planting and harvesting to packaging and consuming - and improve the health of land and soil, by creating certainty on land rights and land access, and using traditional knowledge more effectively. More broadly, countries should investigate the synergies and trade-offs between land use, biodiversity, climate change and food, and move to more coherent and sustainable land use solutions at the national and local level (OECD, 2020[79]). To scale up agriculture, LAC countries can develop long-term processes involving local organisations, share collective learning, and support on developing capabilities of workers in the agriculture and food system. Countries can also strengthen agricultural research and extension systems to generate innovations that increase productivity gains in the region, simplify intellectual property laws and stream product prototype development processes and support research on unattractive productive opportunities like orphan crops or smallholders. Moreover, it is important that LAC countries develop and implement policies aiming to modernise agricultural infrastructure, including information and communications technology, and enact policies with the objective to ensure the establishment of climate-smart agriculture practices (Le Coq, Sabourin and Fouilleux, 2020[80]); (Morris, Sebastian and Perego, 2020[81]).

Recommendation

Prioritise land restoration and climate adaptation policies in agriculture and introduce measures that will transform the food systems and improve the health of land and soil.

Nature-based Solutions to address climate change

NbS have been introduced by many LAC countries as part of their NDCs. They are measures which protect, sustainably manage and restore nature, while maintaining or enhancing ecosystem services to address socio-economic and environmental challenges (OECD, 2020[82]). Their benefits are undisputable: they provide additional benefits to those gained by ecosystem services, they can be cost-effective, provide multiple co-benefits, and can complement existing non-green infrastructure, while responding to the impacts of climate change with some flexibility. Integrating NbS in long-term climate-resilient infrastructure planning can also contribute in better managing some climate-risks (OECD, 2018[55]).A recent report by the World Resources Institute (WRI), on NbS in the LAC region identified about 150 NbS projects, on water, energy, transport and urban development. In many cases, these projects show multiple benefits in parallel, such as local job creation, improving livelihoods, achieving biodiversity benefits and carbon sequestration (Ozment et al., 2021[83]).

However, there are still challenges that limit a wider adoption and implementation of NbS (OECD, 2021[84]); (Ozment et al., 2021[83]). These are also present in the LAC region:

NbS are yet to be fully integrated in sectoral policies, therefore complementarities and trade-offs between NbS and sectoral policy objectives are not always clear.

A clear policy framework and investment opportunities, which allow for NbS to be adopted and implemented are often missing, therefore traditional solutions (i.e. for infrastructure) is maintained.

Multiple government agencies are supporting NbS, yet without the necessary co-ordination. Efficiency and effectiveness may be lost due to unclear responsibilities, duplication of efforts, and scattered funding.

Technical capacities at the local level may often delay the implementation of a project, which requires first capacity building and training.

The existing funding and financing framework does not acknowledge NbS’ special characteristics, therefore there are limited financing mechanisms to which NbS are eligible for funding.

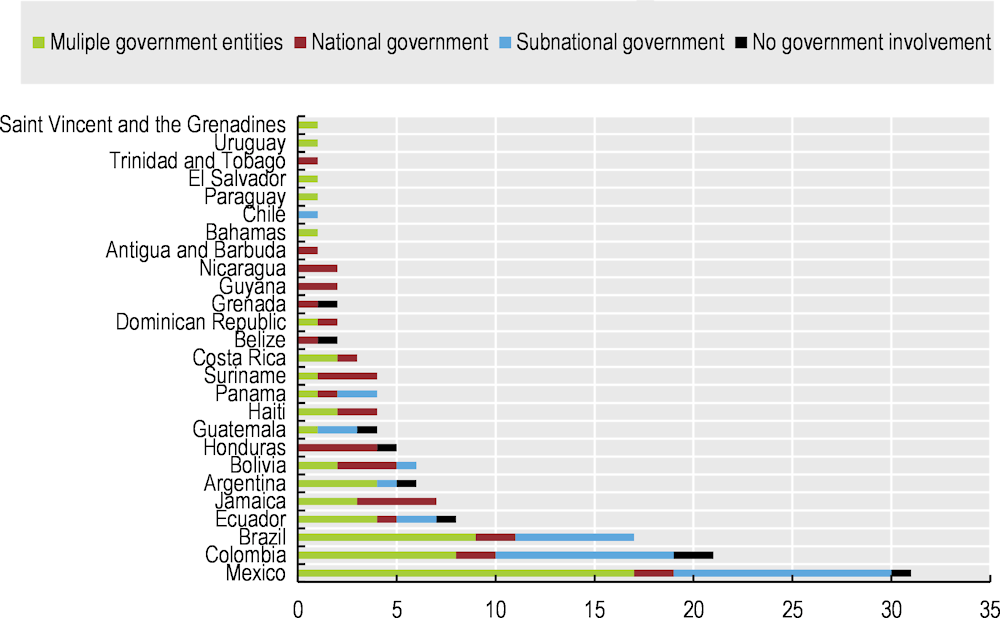

There is limited private sector involvement in NbS, which hampers scaling up the efforts. In LAC 94% of the NbS projects have government participation (national or local), with the engagement of civil society, while about 75% depend on grants, with insufficient funding.

Chile, Colombia and Mexico acknowledge the importance of NbS for climate adaptation, through specific references in their NDCs (OECD, 2021[84]). Other LAC countries have also introduced NbS projects, with a high level of participation from civil society and national governments (Figure 2.9). In the case of Colombia’s National Development Plan, NbS are to be designed with a community focus, as they could help achieve objectives such as eliminating deforestation, preserving ecosystems and transforming productive sectors through green pathways. Special focus is given in integrating NbS in agriculture, mining and energy, and tourism policies, as means of addressing both climate mitigation and adaptation (OECD, 2023[13]).

Figure 2.9. The vast majority of NbS projects in LAC have some form of government participation

Note: Figure shows stakeholder groups that are leading or participating in the NbS projects. Subnational government include municipalities, cities and states.

Source : (Ozment et al., 2021[83])

Further efforts are required, so that LAC countries can overcome the abovementioned challenges, and successfully upscale NbS to address climate change in a more coherent, co-ordinated manner. Including NbS in policy frameworks is only a first step. Piloting projects is an opportunity to see in practice how to best improve the existing policy instruments, so that they are more inclusive of NbS, especially in economic sectors that require eminent actions to be taken to reduce their GHG emissions and their negative impact to natural resources.

Recommendation

Integrate and upscale the use of Nature-based Solutions in policy instruments that address climate change mitigation, adaptation and ecosystems’ protection.

Properly value ecosystem services to generate economic compensation for the use of nature, particularly, to channel the revenues to entities and communities that protect nature.

Effective control and zero-tolerance for illegal trade

Illegal trade in environmentally sensitive products can be a major factor leading to the disruption of ecosystems and undermine climate change adaptation and mitigation measures, as well as challenge national and local economies. Illegal wildlife trade can threaten biodiversity and can have negative implications for ecosystem functions. Reducing the population of a species may lead to changes in the ecosystems, depending on the role these species play and what effects these may have to resilience (Phelps, Board and Mailley, 2022[85]). A major driver of such illegal trade is often the high demand from foreign markets and the large profits for those involved in such exporting activities (OECD, 2012[86]).

Illegal trade in fauna and flora is not adequately monitored, as there is a lack of adequate taxonomic information available, making it difficult to identify species. In addition, there is lack of data and evidence on illegal wildlife trade activities and wildlife crime, limiting the understanding of the vastness of the issue in LAC (UNODC, 2020[87]). In Peru alone, which records illegal wildlife trade activity, around 102 000 live animals of protected species have been confiscated since 2000 (Jabiel, 2002[88]).

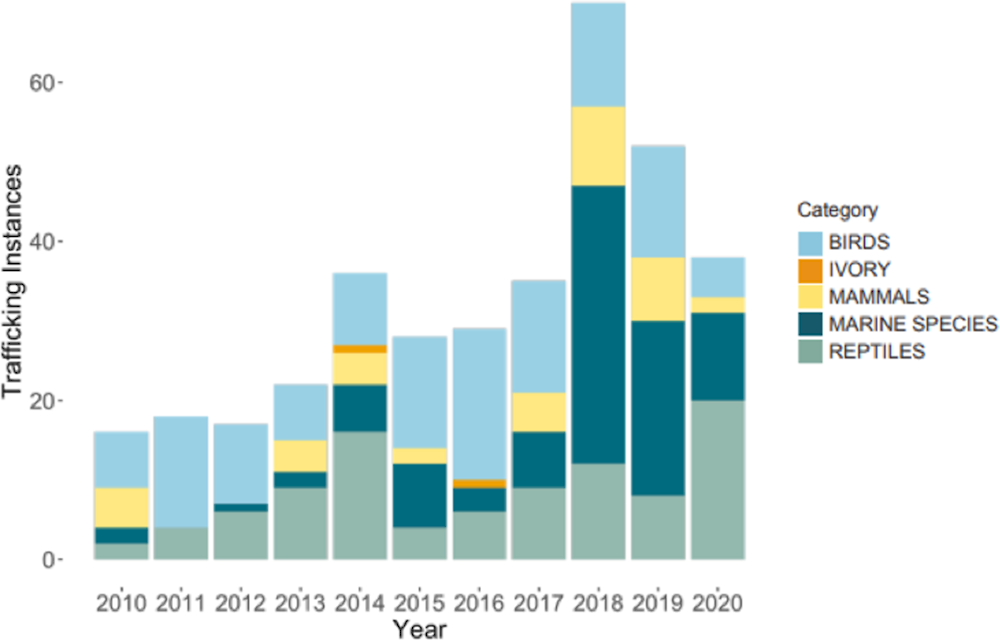

Unavailability of scientific information which helps classify species and organisms may impede efforts on safeguarding biological diversity. The Global Taxonomy Initiative, established by CBD COP in 1998, provides training and knowledge exchange between countries, while enriching the database of animal, plant and fungal species (CBD, n.d.[89]). Efforts in the LAC region had intensified to reach the Aichi targets on illegal trade in wildlife, through the enforcement of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (UNEP-WCMC, 2016[90]). However, wildlife trafficking persists (Figure 2.10); and together with illegal mining, timber harvesting and illicit crops, cause serious pressure on biodiversity in the region (OECD, 2018[91]). In parallel, the LAC region is showing an increase in numbers of species threatened with extinction, because of overexploitation, habitat fragmentation and loss, and disease (WWF, 2020[92]). Additional measures to combat such activities, in combination with illegal trade, would help minimise biodiversity loss in the region.

Figure 2.10. LAC Wildlife Trafficking 2010-2020

While not always the case, illegal trade of wildlife is often intertwined with other criminal activities and organised crime, either because criminal groups expand their activities to other illegal trading markets than those they originally covered (for example from trading solely drugs to also trading wildlife) or because they use the same trafficking/smuggling networks (van Uhm, South and Wyatt, 2021[94]).

International co-operation is necessary for combatting illegal wildlife trade. Countries in the Americas have signed the 2019 Lima Declaration on Illegal Wildlife Trade, which calls for strengthened collaboration across source, transit and destination countries; improvements in national regulations for preventing, combatting and eradicating illegal trade; as well as enhancement in the criminal justice system for better response to wildlife trafficking. However, the declaration is not binding, and implementation has been slow (Guynup, 2023[95]).

The LAC region is also home to natural resources such as metals and minerals, including those that are deemed critical for the transition to more sustainable energy resources. Extractive activities in the region often present environmental and social impacts, negatively affecting water, air and soil, biodiversity loss, and affecting local (and indigenous) communities’ livelihoods and health. Informal and illegal mining is also linked to organised crime, such as in the case of Colombia, Panama and Peru, where illegal gold mining is used for money laundering and illegal drug trade (OECD, 2022[96]).

Several multilateral and bilateral policy initiatives have been launched in the LAC region or with LAC countries, to increase co-ordination, joint operations and investigations against illegal mining. The International Criminal Police Organisation (INTERPOL) supports LAC countries in developing national, regional and international co-ordinated law enforcement responses, in an attempt to tackle illegal mining. With a focus on Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Panama and Peru, INTERPOL proposes the creation of national multi-agency illegal mining taskforces; and to appoint focal points in enforcement agencies that will be responsible for enforcing and investigating illegal mining crimes (INTERPOL, 2022[97]).