Chapter 5 assesses the relationship between population density and political violence within North and West Africa. The chapter finds that violence is indeed spatially associated with urban areas, occurring most frequently near cities. Using disaggregated conflict data for 21 states across 22 years, the analysis shows that while only one-third of all violent events occurred in locations designated as urban, nearly half occurred within just 10 kilometres of urban areas. The chapter also notes significant differences in the way that violence has evolved in North Africa and West Africa. In West Africa, conflicts are increasingly rural, due to the emergence of jihadist organisations, while urban violence was more common overall in the highly urbanised countries of North Africa. There are also important differences in the relationship between violence and distance to urban areas across states. States with major conflicts, such as Nigeria and Libya, exhibit a clear pattern of violence increasing with proximity to urban centres, while others, such as Mali, do not. Violence tends to be predominantly clustered in small urban areas of less than 100 000 inhabitants, rather than in medium or large areas.

Urbanisation and Conflicts in North and West Africa

5. Is violence becoming more urban in North and West Africa?

Abstract

Key messages

Rural areas are more violent than urban areas: more than 40% of all events and fatalities recorded since 2000 occurred in areas with fewer than 300 people per square kilometre.

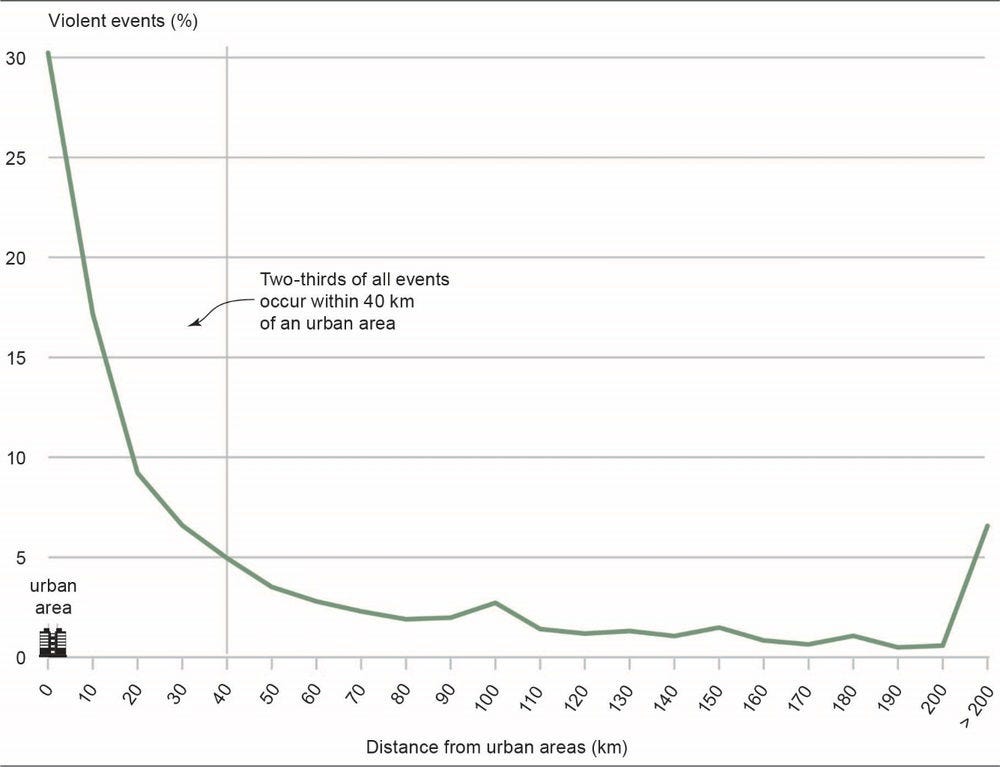

Violence tends to decrease with distance from urban areas. More than two-thirds of all events occur within just 40 kilometres of urban areas.

Violence is more frequent in small urban agglomerations of less than 100 000 inhabitants (70% of violent events and 64% of fatalities) than in medium or large urban areas.

Violence has become far more rural over time, even as urban populations continue to grow.

Rural violence is particularly widespread in the Sahel, where jihadist insurgencies tend to be both attracted by cities and to reject their perceived moral corruption.

North and West Africa have experienced unprecedented levels of violence in the last two decades. A significant proportion of the violent events and fatalities observed in the region occur near urban areas, at rates that have not been precisely measured. This chapter provides an exploratory spatial analysis of the relationship between political violence and urban areas in North and West Africa. It examines whether political violence is predominantly rural or urban, whether the intensity of violence in urban areas has increased over time, and why certain cities or their hinterland have transformed into hotspots of violence since 2000. The analysis of 22 years of disaggregated conflict data suggests that violence decreases with distance from urban areas. It is also becoming more intense in rural areas, especially in West Africa. The spatial analysis also suggests that urban and rural violence are unevenly distributed across the region, underlying the need to understand the local roots of conflicts and the specificities of jihadist insurgencies in a growing number of countries.

Violence decreases with distance from urban areas

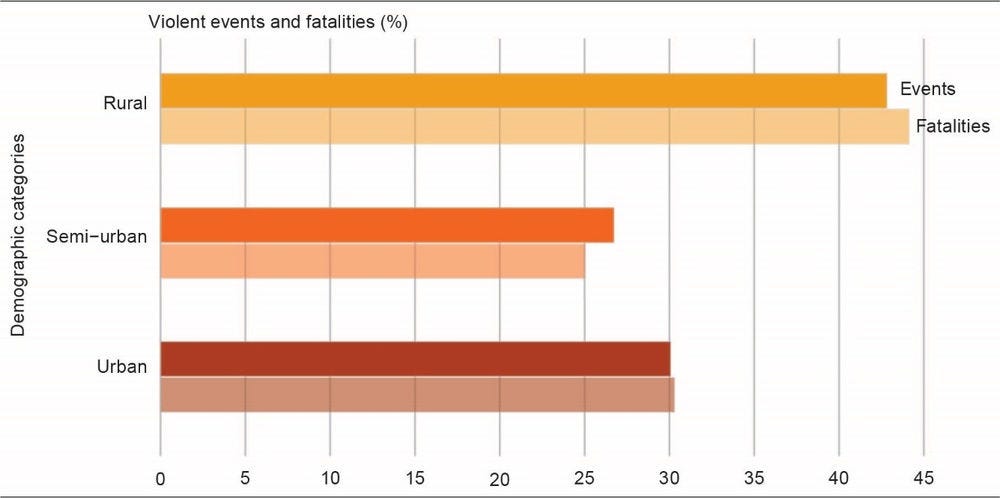

Violence is predominantly rural, across the region. The data available shows that 43% of violent events and 44% of all fatalities recorded from 2000-22 occurred in areas with fewer than 300 people per km2 (Figure 5.1). Urban areas, or those with at least 1 500 people per km2, accounted for 30% of all events and deaths, while semi-urban areas that transition between rural and urban population densities had the lowest proportions, with 27% of events and 25% of fatalities. Violent events are as deadly in urban areas (3.8 fatalities per event) as in rural areas (3.9) at the regional level and over a long period of time, and slightly less lethal in semi-urban areas (3.5).

Figure 5.1. Violent events and fatalities by demographic categories in North and West Africa, 2000-22

Note: Data is available through 30 June 2022. Under the United Nations definition, cells of 1 500 or more people per square km are classified as urban, those between 300 and 1 499 as semi-urban, and those below 300 are rural (United Nations, 2020[1]).

The proportion of violence and fatalities per demographic category (Figure 5.1) is also consistent across two main types of violence tracked by ACLED: battles, and violence against civilians. One exception was noted, with remote violence and explosions, however. While urban areas accounted for 30% of these types of violence, they included 36% of the fatalities from these events. This was the largest gap between the proportion of events and fatalities of any event type. The relatively high population density in the vicinity of these events within an urban setting is a reasonable explanation for this difference. Battles are the most lethal type of violence, with 4.6 fatalities per event across the region since 2000, particularly in rural areas, where nearly 5 people are killed on average in such events. Explosions and remote violence, and violence against civilians, kill 3.2 people per event on average, without significant differences in event types.

Violence tends to decrease very sharply with distance from urban areas. Violence exhibits a clear distance decay from urban areas (Figure 5.2). While most of the violence did not occur in urban areas, the overwhelming majority occurred relatively close to them. More than two-thirds of all events (68%) occur within just 40 km of an urban area, and 47% within 10 km. A secondary peak can be observed at a distance of around 100 km of an urban area. In other words, the closer one gets to an urban core, the more violent events can be found, in aggregate, but these events are occurring in rural areas per United Nations (2020[1]) population density guidelines. These patterns are nearly identical for percentage of fatalities, and invariant across the main types of violence identified by ACLED (battles, violence against civilians, and explosions and remote violence).

Figure 5.2. Violent events by distance from urban areas in North and West Africa, 2000-22

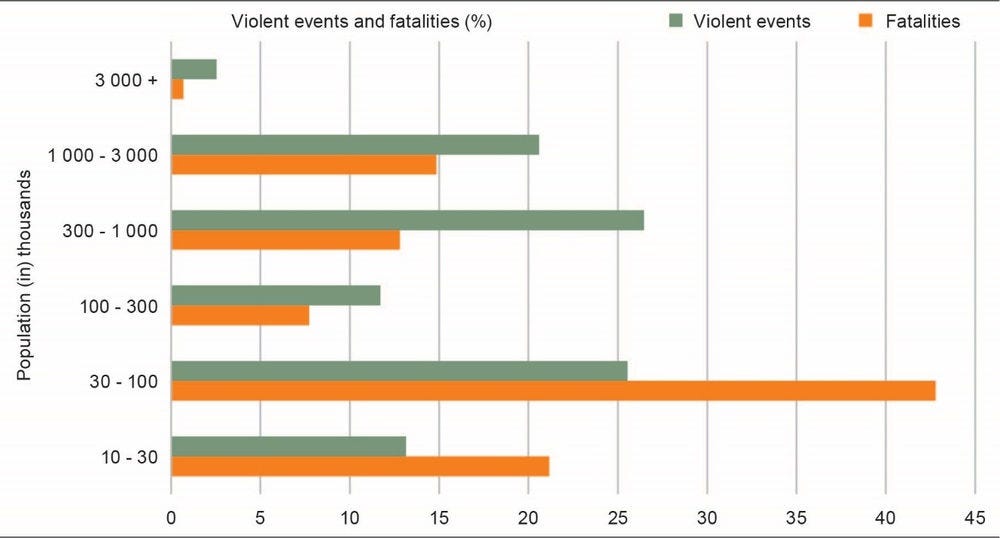

Violence tends to be predominantly clustered in small urban areas. The proportion of violent events and fatalities varies widely according to the size of urban areas. More than half of violent events observed in 2015 occurred in urban areas of between 30 000 and 100 000 inhabitants (26%) and in urban areas of between 300 000 and 1 million people (27%) (Figure 5.3). Fatalities are far more clustered in urban areas from 30 000 to 100 000 inhabitants (43%) than anywhere else in the region. Politically motivated violence is particularly rare in large cities of more than 3 million people, where it accounts for only 3% of violent events and 1% of fatalities. Overall, violence is more frequent in small urban agglomerations of less than 100 000 inhabitants than in medium or large ones. Nearly 40% of violent events and 64% of fatalities occurred in small urban areas, which represent 92% of the cities and 32% of the population of the continent in 2015 (OECD/SWAC, 2020[4]).

Figure 5.3. Violent events by urban categories in North and West Africa, 2015

Note: These results build on the Africapolis database, which maps the perimeter of each urban agglomeration and calculates its population. Africapolis population estimates in both North and West Africa are only available for 2015 (see Chapter 3). The 2020 update will be available in 2023.

The aggregate findings suggest that the rapid urbanisation of the region does not necessarily lead to an increase in urban conflict. This surprising result is due, first, to the fact that North and West Africa is a vast region that includes countries with high levels of conflict and relatively low levels of urbanisation, such as Mali and Niger, and countries with high levels both of urbanisation and conflict, such as Nigeria and Libya. The variations in the regional urbanisation process reduce the importance of certain urban areas. In addition, the report studies conflict over 22 years, a relatively long period, in which conflicts have ended in some places, such as Liberia and Sierra Leone, emerged or spilled over in others, such as Mali and Burkina Faso, and persisted in others, such as Nigeria.

Given the size of the region and the duration range of the study, these initial findings are reviewed in two interrelated ways. First, the conflict data provided by ACLED is disaggregated temporally, to see whether certain years exhibited an unusual annual pattern. Second, the data is spatially divided by country, to study how the outcomes in specific national contexts may differ from the general pattern.

Violence is becoming increasingly rural

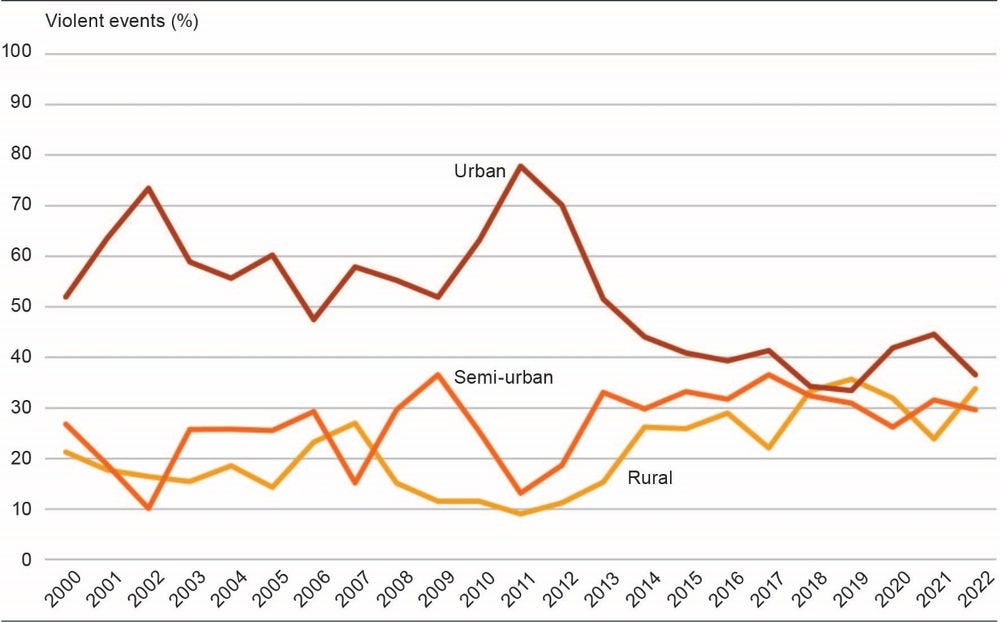

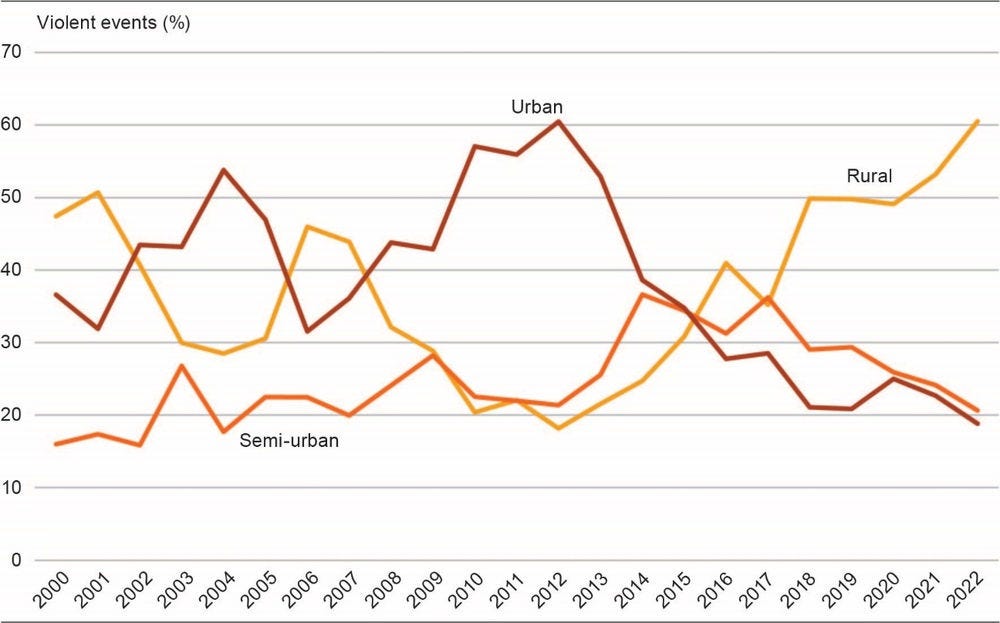

Violence has become far more rural over time, despite the growth of the urban population. The relationship of violent events to urban areas has varied widely as episodes of conflict have waxed and waned in the region, some with clear rural elements (Figure 5.4). Urban violence surged in 2004 and again in 2012. During the first peak, in the First Ivorian Coast Civil War, the key cities of Korhogo, Bouaké and Abidjan suffered a high number of fatalities, and in the Nigerian cities of Yelwa and Kano, 1 700 people were killed in religious violence in May 2004.

The second peak corresponds to the beginning of the Malian Civil War in 2012, when a coalition of secessionist rebels and jihadist groups took over the key cities in the north of the country. Nevertheless, despite these peaks, in only half of the last 22 years was urban violence the most common setting. In 2012, urban violence peaked at 60% of all events, but by 2022, it had fallen sharply, to its lowest point, of just under 20%. Rural settings were the second most common, with the largest share of violence in 10 years. In 2021, 53% of all events and 56% of all fatalities occurred in rural areas. Semi-urban settings were the most common only once, in 2017, and even then, narrowly so. This was true for each type of violence and for fatalities.

Figure 5.4. Violent events by demographic categories in North and West Africa, 2000-22

Note: The figure summarises the relationship between violent events and the United Nations’ “degree of urbanisation” categories between 2000 and 2022 for the three types of violence tracked by ACLED: battles, violence against civilians, and explosions and remote violence. The data is available through 30 June 2022.

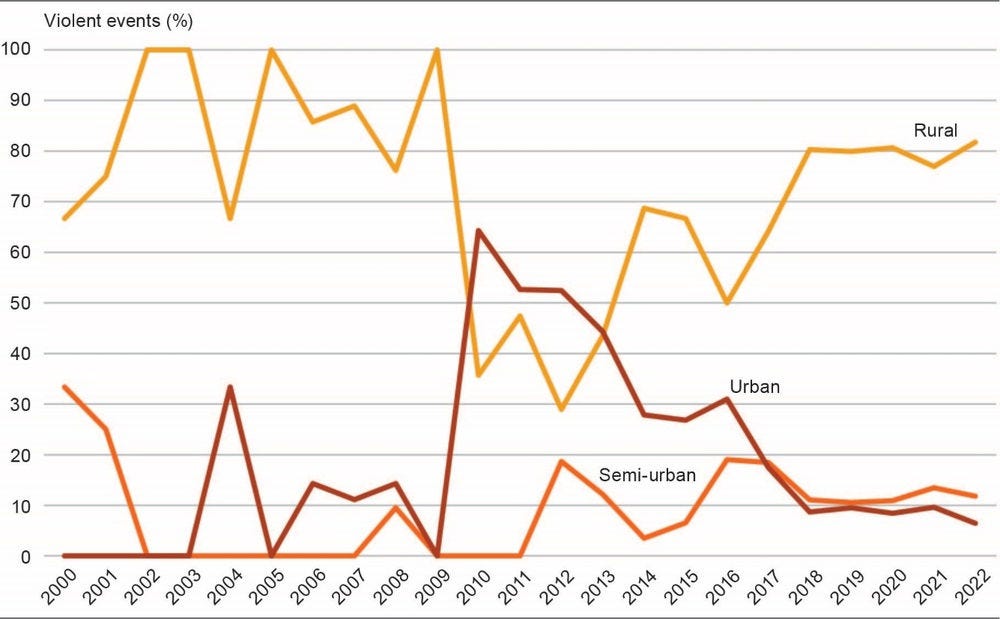

The temporal variability of urban violence is also connected to the shifting geography of conflict over time. For example, in Nigeria, urban violence is the predominant category in all but a single year since 2000. The proportion of violent events in rural areas of Nigeria, however, has slowly increased since the early 2010s, when the Boko Haram insurgency emerged around Lake Chad (Figure 5.5). Rural violence was predominant in Mali, except for just three years between 2011 and 2013, the peak years of the most recent Tuareg rebellion (Figure 5.6). It thus seems likely that as conflict waxes or wanes in one area of the region, so too does the importance of either rural or urban spaces to the belligerents. This suggests that not only the temporal but the spatial variability of these regional patterns may play a role.

Figure 5.5. Violent events by demographic categories in Nigeria, 2000-22

Figure 5.6. Violent events by demographic categories in Mali, 2000-22

Urban violence varies across states and sub-regions

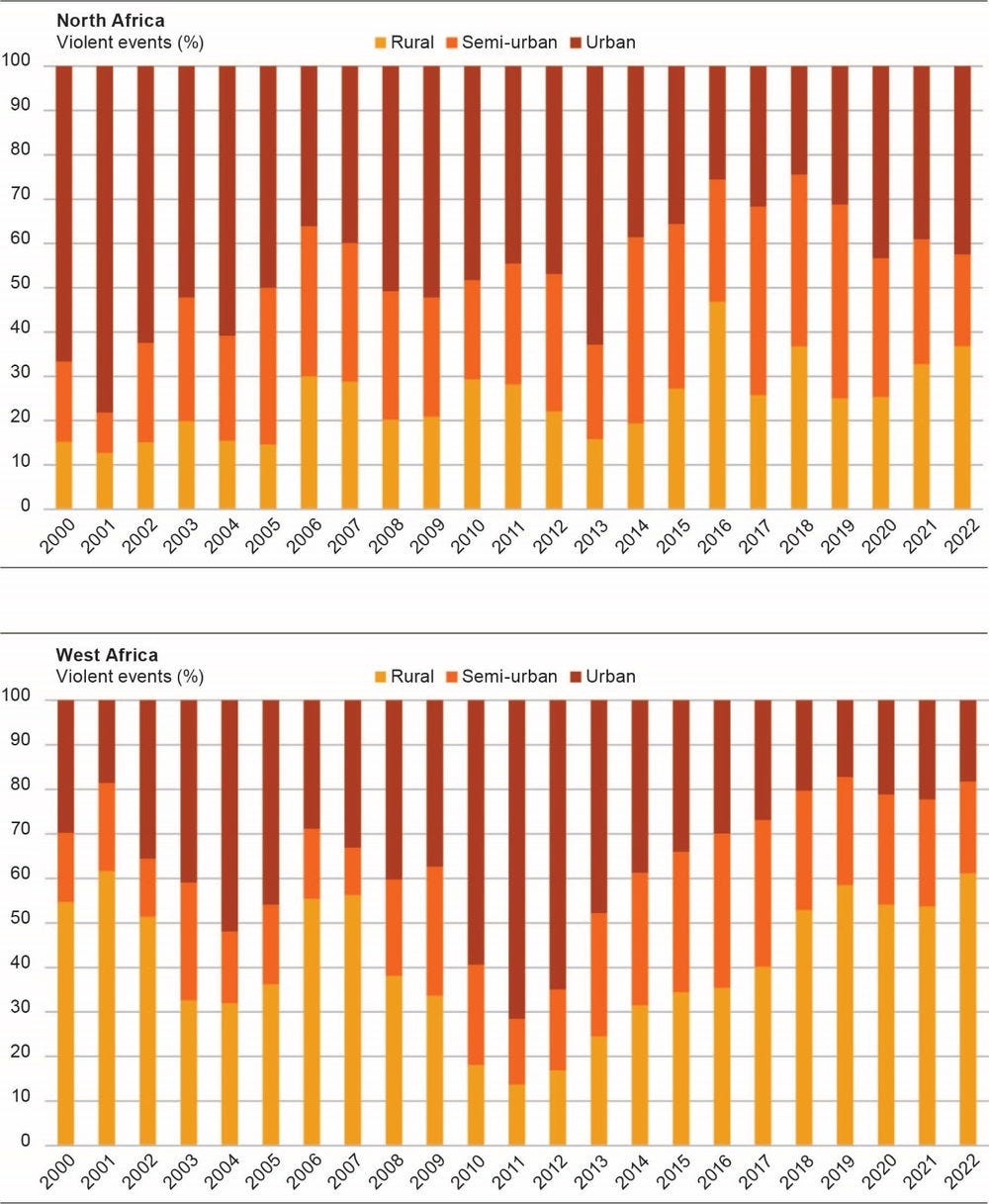

Urban violence is more common in North Africa than in West Africa, but its share is declining in both. To understand where political violence is predominantly rural or urban, the data is first disaggregated into two sub-regions, North Africa (comprised of Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco) and West Africa (the remaining states). In each sub-region, the report examines the changing proportion of urban violence over time. North African states tend to have higher urbanisation rates (70% in 2021 according to the United Nations) than those in West Africa (48%), suggesting that violence may be more urbanised north of the Sahara.

Urban violence has indeed been more common overall in North Africa in the past two decades (Figure 5.7). However, the rates closely tracked each other from 2003 to 2009 and again from 2013 through 2018. The latter period is particularly telling, given the simultaneous occurrence of major conflicts in both areas: the Libyan Civil Wars (2011, 2014-20) started only two years after the Boko Haram insurgency in 2009, and only a year before the Malian conflict (2012-present). Each sub-region’s conflicts were urbanised, with violent events affecting a larger share of urban areas in West Africa between 2010 and 2012. This suggests that the notable sub-regional differences in urbanised population between North and West Africa cannot fully explain why conflict in both regions would similarly affect urban areas.

Figure 5.7. Violent events in urban areas by sub-region, 2000-22

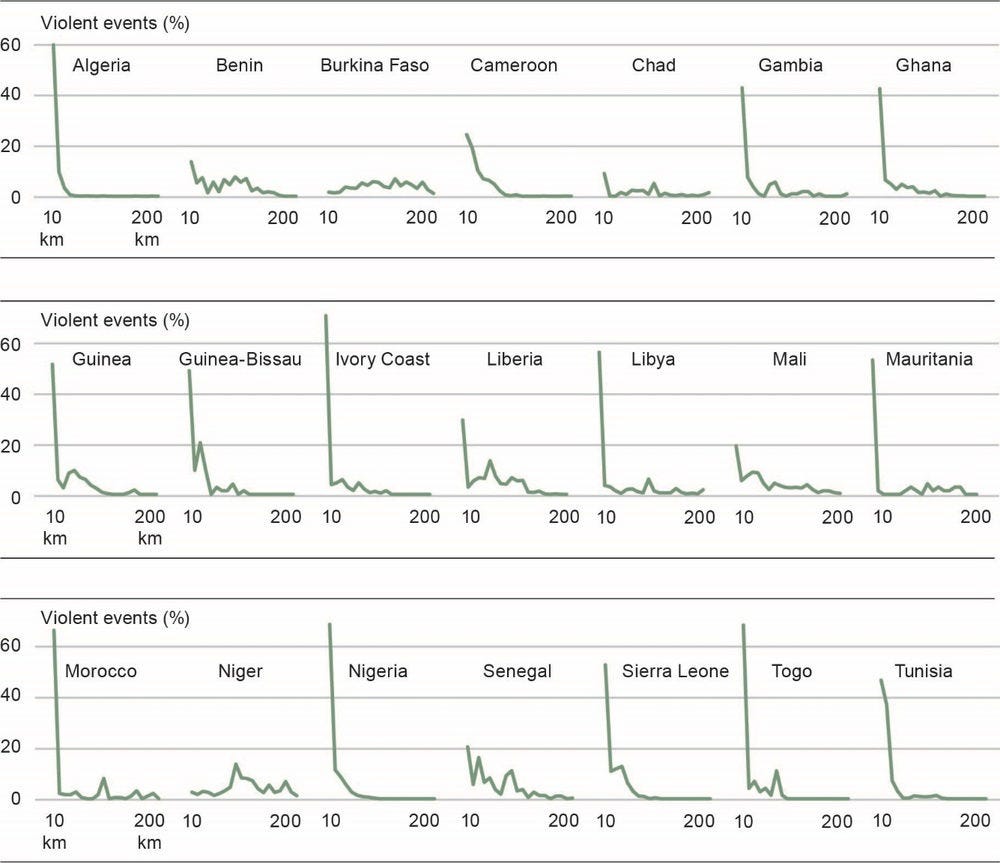

States vary significantly in the relationship between violence and distance to urban areas. Reviewing the distance to urban areas in each of the 21 states in the region separately (Figure 5.8) reveals wide variations. Several states exhibit a clear distance decay pattern, including many with major conflict episodes in the past 22 years, such as Algeria, Cameroon, Libya, Nigeria and Tunisia. The general pattern is observable, if less marked, in several additional states, such as Cameroon, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. In a few other states, both with and without episodes of conflict, the relationship between violence and distance to urban areas was inconsistent. Notably, in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, the current overlapping conflicts are largely rural. For all three countries taken together, the highest proportion of events occurred between 90 and 100 km from the nearest urban area.

Figure 5.8. Violent events by distance from urban areas and by state, 2000-22

The next section examines the geography of urban violence by mapping violence and its relation to urban areas in three of the most affected areas of North and West Africa: the Central Sahel, the Lake Chad region and Libya. In each region, the analysis focuses on a detailed analysis of places that have experienced a high number of fatalities since 2000: Djibo, Gao, and Kidal in the Central Sahel, Gwoza, Maiduguri and the Sambisa Forest around Lake Chad, and Benghazi, Sirte, and Tripoli in Libya. The case studies confirm that much of the violence in urban areas has occurred since the early 2010s, and that the number of fatalities observed in urban areas of the Lake Chad region and Libya has been consistently higher than in the Central Sahel, with major peaks corresponding to uprisings by violent extremist organisations and corresponding military counter-offensives.

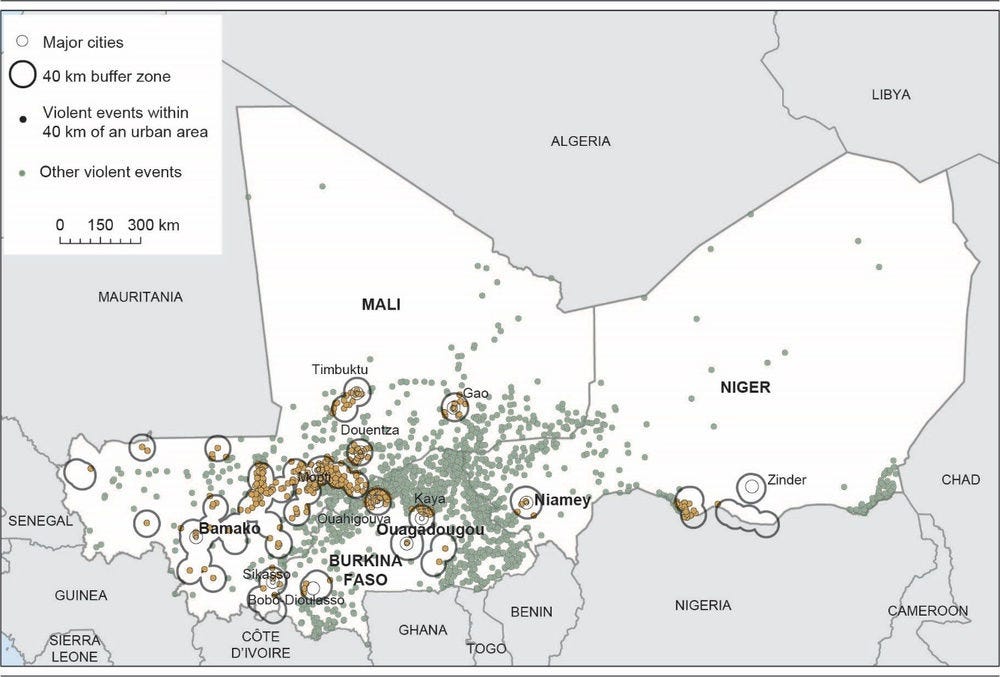

Ruralisation of conflict in the Central Sahel

The Central Sahel is the zone of North and West Africa where violence is the most likely to occur in rural areas.1 The region is confronted with a myriad armed groups whose primary activities take place in rural hinterlands. Only 23% (1 050 out of 4 732) of violent events in 2020 and 2021 occurred within 40 km of an urban area. The fact that violence predominantly affects rural areas does not mean, however, that urban areas and their immediate peripheries are immune to violent events. Event concentrations are associated with many urban areas (Map 5.1). The string of urban settlements running from northwest to southeast, between Mopti in Mali and Ouahigouya in Burkina Faso, saw 440 events within 40 km in 2020 and 2021. Smaller event clusters have occurred near Maradi in Niger, and Douentza, Gao and Niono in Mali. Notably, even as violence has intensified recently, it has not clustered near the national capitals of each country (Box 4.1). To the extent that some evidence of conflict urbanisation appears within an otherwise mostly rural context, it has been associated with smaller and perhaps more marginal cities, including several near international borders.

Map 5.1. Violent events and urban areas in the Central Sahel, 2020-22

Saharan and Sahelian cities such as Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu have played a strategic role at the beginning of insurgencies that have emerged in northern Mali and progressively affected neighbouring countries in the past decade. In such a sparsely populated region, capture of territory is fruitless, given the impossibility of garrisoning it. This principle was formulated more than a century ago by T.E. Lawrence (1920[5]), who famously wrote that desert warfare is comparable to naval war, in the sense that insurgents are mobile, ubiquitous, independent of military bases and relatively indifferent to the constraints of their environment. This is true, of course, of many irregular forces. What makes Saharan insurgents peculiar is that, like seafarers, they have developed a conception of space in which strategic areas, fixed directions and localised resources matter less than tribal allegiances, networks of cities and control of roads (Walther, 2015[6]). In the Sahara-Sahel, the control of movement has historically proved the most efficient way to defeat regular forces and control the local population, which explains why so much of the violent activities observed in the first stage of the Malian civil war occurred in or around urban areas, as well as along strategic trade corridors (Retaillé and Walther, 2013[7]).

Kidal, the political centrality of the margins

Kidal is one of the most important cities of the heartland of the Kel Adagh Tuareg confederation in remote north-eastern Mali. Despite its small size, of only 31 800 inhabitants in 2015, Kidal was the launching pad for four major rebellions in Mali in 1963-64, 1990-96, 2006-09 and 2012-13. The first of the rebellions was brutally repressed in Kidal by the Malian military, while the other three each ended with peace agreements that ultimately proved unable to prevent resumption of the conflict.

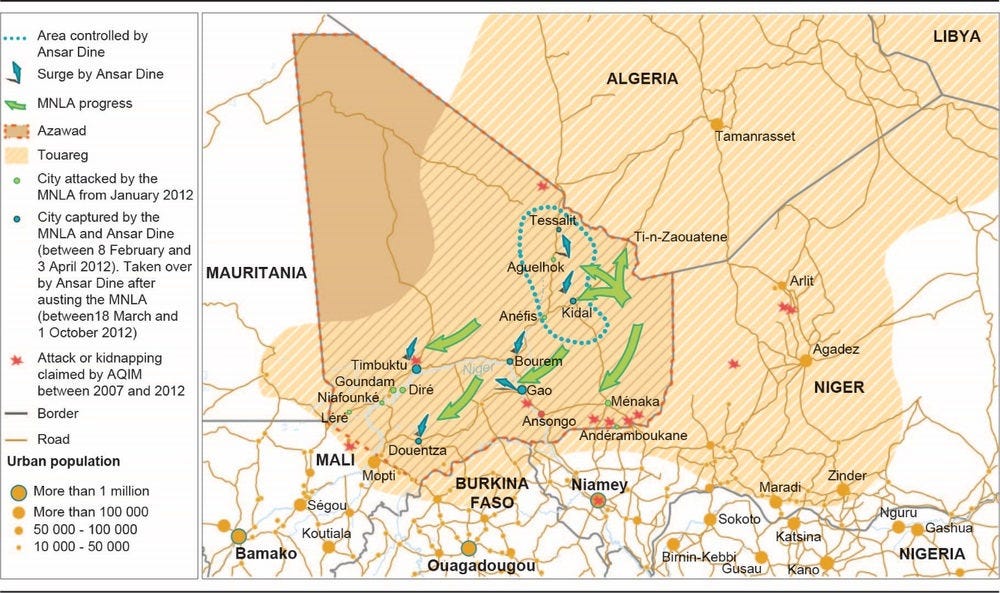

In the 2012 rebellion, Kidal was controlled first by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), a Tuareg-led separatist movement, and was then taken over by a jihadist coalition that included Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), and Ansar Dine (Defenders of the Faith), which became the dominant faction in Kidal (Map 5.2). In January 2013, the French military and its coalition partners launched Operation Serval, to frustrate a southward advance by jihadists and expel them from northern cities. The dynamics of the recapture of Kidal from jihadists have proven enduringly controversial. On 28 January 2013, the MNLA and a group of high-level defectors from Ansar Dine, calling themselves the Islamic Movement of Azawad (later renamed the High Council for the Unity of Azawad, or HCUA), announced that they had taken control of Kidal. On 30 January, French forces captured Kidal airport, and Malian authorities complained publicly that they had not been informed or included. Chadian troops entered the city on 5 February, and Kidal was the last major northern Malian city to fall to Operation Serval.

The MNLA and the HCUA then formally shared control of Kidal with Malian government forces in a tense arrangement. In May 2014, the visit of then-Prime Minister Moussa Mara to Kidal triggered direct fighting between the MNLA and Malian forces, a conflict the MNLA won. The same year, the MNLA, the HCUA and a segment of the Arab Movement of Azawad formed a coalition called the Coordination of Movements of Azawad (CMA), which became one of three signatories to the 2015 Algiers Accord, along with the Malian government and a coalition of anti-rebel militias called the Plateforme. The CMA consolidated political and military control of Kidal and much of the surrounding region, beating back challenges from the Plateforme’s leading component, the Imghad Tuareg Self-Defence Group and Allies (GATIA).

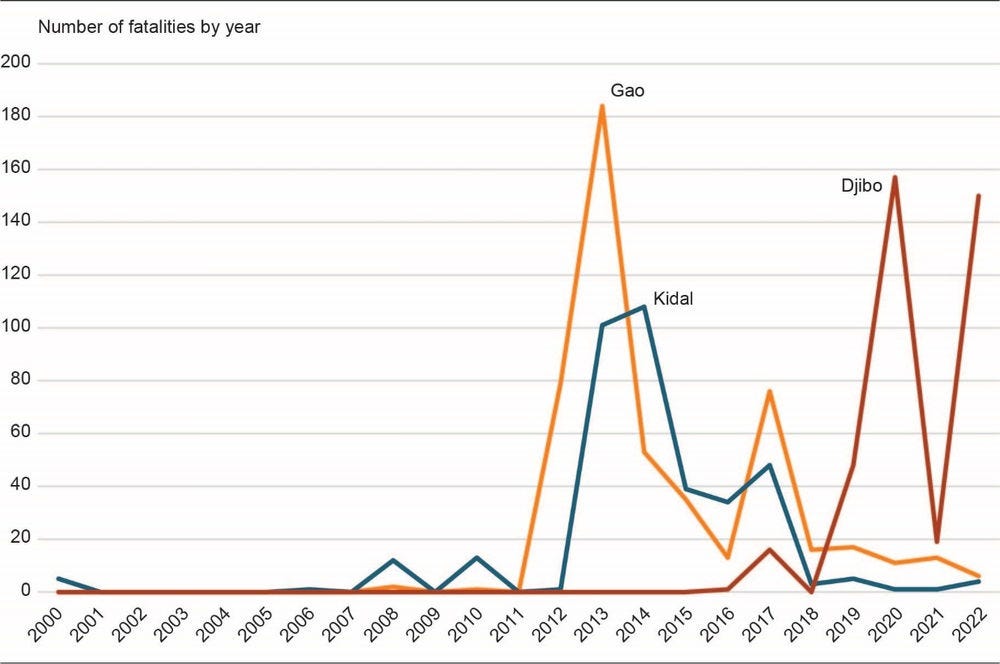

Despite its political centrality in the Malian conflict, Kidal has been strikingly free of violence by comparison with other zones of conflict, with 372 fatalities in 1997-2021. The major peak of violence in the city came in 2013 (101 fatalities) and 2014 (108), reflecting the turbulence of Serval and its immediate aftermath, along with the violence of the May 2014 clashes and of the CMA’s overall efforts to consolidate control of the city. Subsequent violence involving the CMA has often been in the Kidal region rather than in Kidal city itself. For example, July 2017 clashes between the CMA and GATIA concerned control of the city of Kidal, but the fighting took place 50 km south-east of the city. In addition to the relative peace that the CMA brought to Kidal, the city is also the hometown of the top Malian jihadist leader, Iyad ag Ghali, who has headed the Al Qaeda-linked Group for Supporting Islam and Muslims (JNIM) since its creation in 2017. Although JNIM has conducted numerous attacks in the Kidal region, the group’s violence is primarily directed at central Mali and northern Burkina Faso.

Map 5.2. The early stage of the Malian conflict, 2012

Gao, epicentre and target of jihadist violence

With an estimated population of 105 900 in 2015, Gao is an important political and cultural centre in north-eastern Mali. The city was badly affected by the northern Malian rebellions of 1990, 2006 and 2012. In 2012, the city was captured first by the MNLA, and later by the jihadist coalition that took over northern Mali. The MUJAO came to control Gao. Both the MNLA and the jihadists inflicted serious human rights violations on the population of Gao. Notably, the Tuareg-led MNLA may have been willing to inflict greater predatory violence on multi-ethnic Gao, where there are Songhai, Arabs, Tuareg, Fulani and others, than in Tuareg-dominated Kidal. MUJAO and the jihadists perpetrated harsh corporal punishments in line with the jihadist interpretation of Islamic law, including amputations and beatings (HRW, 2012[9]).

The violence unleashed in Gao in 2012 set the stage for enduring intercommunal tensions after the town was liberated from MUJAO and the jihadists in 2013 (Figure 5.9). Ethnic tensions flared in incidents such as the 2020 intercommunal clashes involving what appeared to be Songhai-led lynching of Arabs accused of theft. Further complicating the picture is the alleged widespread activity of Arab-dominated drug trafficking networks in the Gao region from the mid-2000s on. Journalists wrote exposés of the “Cocainebougou” neighbourhood in the city (Dreazen, 2013[10]). The town of Tarkint, in the Gao region, was the site of the infamous 2009 “Air Cocaine” incident, in which a plane was discovered laden with cocaine, implicating various businessmen and local officials (Tinti, 2020[11]). More recently, key Gao-based politicians, such as Mohamed Ould Mataly, have been accused of involvement in drug trafficking and in political sabotage and placed under United Nations sanctions (United Nations, 2019[12]).

Meanwhile, Gao remained a target for jihadist violence even after the city’s liberation. In February and March 2013, there was more jihadist resistance against the French and Malian military presence in Gao than there was in Kidal and Timbuktu. Gao was the site of what has been called Mali’s first suicide bombing, in February 2013. Gao was also the location of the deadliest suicide bombing of the entire Malian conflict, targeting a mixed patrol of CMA, Plateforme and Malian army personnel in January 2017. Gao has been repeatedly targeted by jihadists, in part because the city emerged as the nexus point of various security initiatives in northern Mali (Traoré, 2017[13]). Gao hosted the Malian headquarters of France’s counterterrorism mission for the Sahel, Operation Barkhane, and is also the eastern headquarters of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA).

In recent years, violent activities have largely shifted from Saharan to Sahelian regions, and further south. The Kidal region is one of the least affected regions of Mali, with fewer than 70 fatalities recorded from January 2021 to June 2022, compared with more than 2 100 in the Mopti region and 906 in the Gao region (see Chapter 4). As armed groups move south, Burkina Faso has become the most violent country of West Africa after Nigeria, with more than 4 500 fatalities recorded by ACLED from January 2021 to June 22. Accordingly, Burkinabè cities such as Djibo, Dori and Ouahigouya, have been new hotspots of violence for the region.

Figure 5.9. Fatalities in the Central Sahel by (urban) area, 2000-22

Note: 2022 data are projections based on a doubling of the number of events recorded through 30 June.

Source: Authors, based on ACLED (2022[2]) data. ACLED data is publicly available.

Djibo, point of origin for a wider insurgency

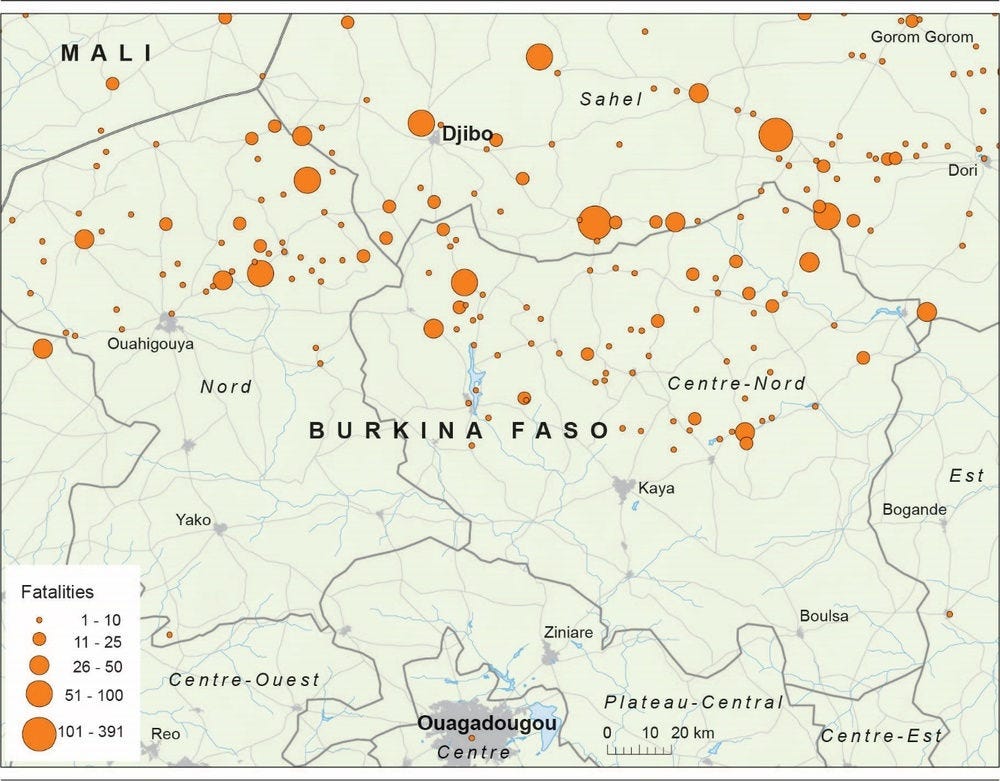

Djibo is the capital of Soum Province, one of four provinces in the Sahel region, the northernmost part of the country. The city is approximately 210 km north of Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, by road and lies less than 70 km by road from the border with Mali. Soum is adjacent to some of the most violence-prone areas of central Mali, a zone engulfed by crisis since 2015 (Map 5.3).

Within Burkina Faso, Soum Province became the point of origin of a wider insurgency initially conducted by the Burkinabè jihadist group Ansaroul Islam. Ansaroul Islam’s founder, Ibrahim Dicko, was born in a village in Soum, and in the 2000s and 2010s, he built a career centred in Djibo, leading Friday prayers at a mosque there, speaking regularly on two Djibo-based radio stations, marrying into the family of a prominent local imam, and creating an Islamic association called al-Irchad (from the Arabic irshad, meaning “guidance”). After Dicko’s contacts with Mali-based militants increased and had a radicalising effect on him and segments of his following in al-Irchad, his local acceptance in Djibo slipped (Thurston, 2020[14]). Ansaroul Islam conducted its first major attack in December 2016 at a military outpost at Nassoumbou, a Soum town approximately 35 kilometres north of Djibo. Ansaroul Islam, first under Dicko and then under his brother Jafar, has had a close relationship with JNIM in Mali.

Map 5.3. Fatalities in Djibo and northern Burkina Faso, 2021

The city of Djibo itself has experienced relatively low levels of violence, with 241 fatalities over the period 1997-2021. The peak year for violence in Djibo was 2020, with 157 fatalities recorded. Yet Djibo has been profoundly affected by the crisis in Soum and beyond. From an early point in the insurgency, poor infrastructure, rivalries within the local elite and accumulated neglect by successive central Burkinabè governments all combined to leave Djibo vulnerable and isolated (ICG, 2017[15]). Violence escalated in areas surrounding the town, including violence inflicted not just by jihadists, but also by the security forces and by self-defence militias known as Koglweogo. For example, in 2019-2020, residents reportedly discovered graves around Djibo containing a total of 180 bodies, with the security forces the prime suspects in the killings (HRW, 2020[16]). The violence on all sides created dynamics that put civilians in the position of being accused by each armed faction of collaborating with the enemy (Koné, 2020[17]).

As the crisis in Burkina Faso escalated and spread across the north and then the east of the country, mass displacement ensued, starting in 2019. The number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) grew from 87 000 in January 2019 to over 1.9 million as of 30 April 2022, including over 574 000 in the Sahel region (UNOCHA, 2022[18]). Many of the displaced flocked to Djibo, whose population had soared above 200 000 by the first quarter of 2022 (Solidarités International, 2022[19]), compared with 38 300 in 2015, according to Africapolis. As of that period, Djibo housed 17% of Burkina Faso’s IDPs. Meanwhile, endemic violence has caused the closure of numerous health centres and schools in Djibo itself, especially from 2018 on.

Starting in 2020, jihadists blockaded Djibo, and assassinated the deputy mayor and the chief imam when they tried to leave; other areas in the north were also blockaded (Koné, 2020[17]). Such blockades appeared designed to reinforce control over key transportation routes, deprive the state of a major administrative centre in the north, and contribute to a wider pattern of intimidation and jihadist shadow governance. In the intervening years, the city has been repeatedly cut off from its surroundings by jihadists. Due to its strategic importance, meanwhile, Djibo has also been the site of complex efforts at negotiating truces with jihadists conducted by local and even national authorities. In late 2020, the government of then-President Roch Kaboré reportedly brokered a truce near Djibo with JNIM (and, presumably, Ansaroul Islam) with the aim of allowing national elections to go forward that year. Those talks appeared to succeed at that limited objective (Mednick, 2021[20]) but proved fragile and temporary, as demonstrated by the resumption of the blockade on Djibo later.

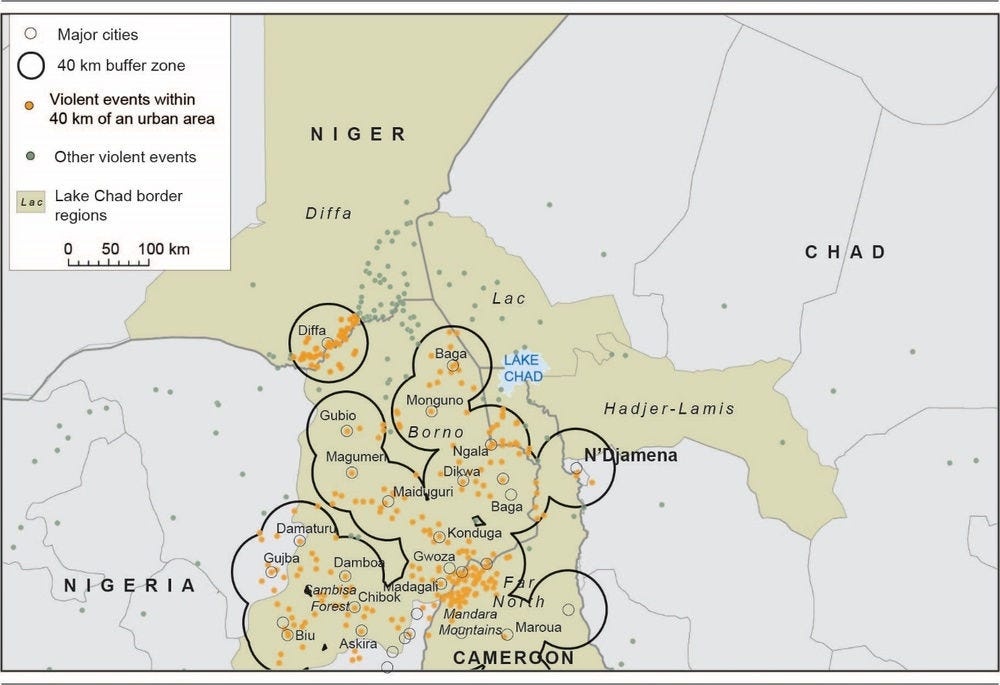

Intensification of violence in the Lake Chad region

The Lake Chad region has recorded the highest number of violent events and fatalities since the late 2000s in West Africa. Twice as many people have been killed in the worst affected regions of the Lake Chad basin (Adamawa, Borno, Diffa, Extreme North and Yobe) than in the whole of Mali and Burkina Faso from January 2012 to June 2022. The four states bordering Lake Chad are facing one of the most violent insurgencies ever recorded in West Africa, led by Boko Haram and its splinter group, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) (Map 5.4).

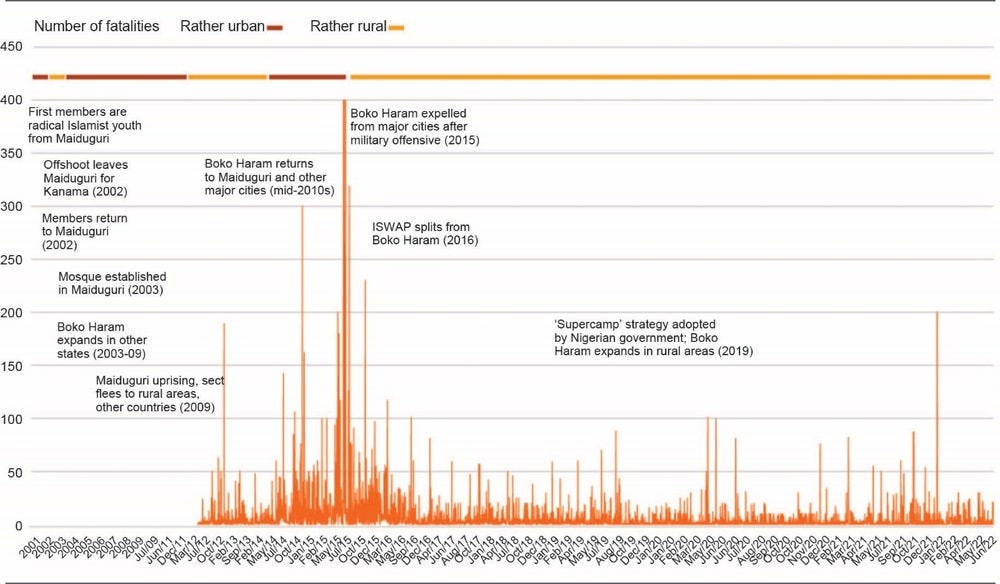

These groups entertain a conflicting relationship with cities. In the early 2000s, the first members of the Boko Haram sect were radical youths from the Alhaji Muhammadu Ndimi Mosque in Maiduguri (Agbiboa, 2022[21]). After declaring the city establishment corrupt, a hard-line offshoot attempted to establish a kind of commune or training camp near the village of Kanama in neighbouring Yobe State, but the hard-liners’ short-lived uprising against authorities was crushed in late 2003 (Thurston, 2017[22]). The survivors returned to Maiduguri and established their own mosque near the railway station (Chapter 2). In 2009, Boko Haram launched a series of spectacular uprisings in Maiduguri, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Yobe, Kano and Katsina. The group was eventually expelled from urban areas and expanded in rural areas. In 2015, as a result of a series of major offensives by the Nigerian military and its regional allies, Boko Haram lost much of its territorial gains and retreated to rural and remote areas such as the islands of Lake Chad or the Mandara Mountains in Cameroon. In recent years, the strategy of the Nigerian government to move its troops (and some civilians) to fortified camps has encouraged Boko Haram and ISWAP to expand their activities in rural areas and along major transport axes (Figure 5.10).

Map 5.4. Violent events and urban areas in the Lake Chad region, 2020-22

Figure 5.10. Fatalities involving Boko Haram and ISWAP, 2001-22

Note: Data is available through 30 June 2022.

Source: Authors, based on ACLED (2022[2]). ACLED data is publicly available.

Maiduguri, the most violent city in West Africa

Maiduguri, the capital city of Borno, Nigeria’s second-largest state, is the most populous city in far north-eastern Nigeria, with an estimated population of 1 012 100 in 2015. Given the extent of Borno State and the large distances between Maiduguri and other major metropolitan areas in Nigeria, Maiduguri is a key economic node linking Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon and Chad.

Maiduguri has played a central role in the Boko Haram conflict. The city is the most violence-prone urban agglomeration in West Africa (5 483 fatalities during the period 1997-2021). According to most accounts, Boko Haram emerged in Maiduguri between the late 1990s and the early 2000s under the charismatic leadership of the preacher Muhammad Yusuf (1970-2009), himself a migrant to Maiduguri from Yobe State (Bukarti, 2020[23]). Yusuf built a large following in Maiduguri and beyond during the 2000s, treating the city as his base and establishing a network of mosques and centres there. Maiduguri was the epicentre of Boko Haram’s violent mass uprising in 2009, in which Yusuf was killed. That uprising proved to be the most decisive turning point in the group’s history, transforming it from a dissident anti-systemic movement with violent elements into a full-blown insurgency.

After Boko Haram re-emerged in 2010 under the leadership of Yusuf’s deputy, Abubakar Shekau, Maiduguri was initially the most frequent target of the group’s violence. Boko Haram staged assassinations, bombings and other attacks there, including the assassination of a major gubernatorial candidate in January 2011 and the targeting of a beer garden in June 2011. That year, the deployment of a new military Joint Task Force (JTF) contributed substantially to the escalation of violence in Maiduguri, with the JTF accused of systematic human rights violations and collective punishment (Amnesty International, 2011[24]).

In June 2013, the emergence of a government-backed vigilante force called the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) further changed the dynamics of the conflict. The CJTF recruited thousands of volunteers, with its centre of gravity in Maiduguri and a substantial presence elsewhere in northern Nigeria. CJTF members’ local knowledge helped to root out Boko Haram cells in Maiduguri, but the CJTF was accused of summary justice and harsh treatment for accused Boko Haram members, many of whom did not receive any due process (Agbiboa, 2022[21]). These abuses then became further triggers for Boko Haram reprisals. One particularly severe Boko Haram attack during this period came in March 2014 at Giwa Barracks, a military prison in Maiduguri.

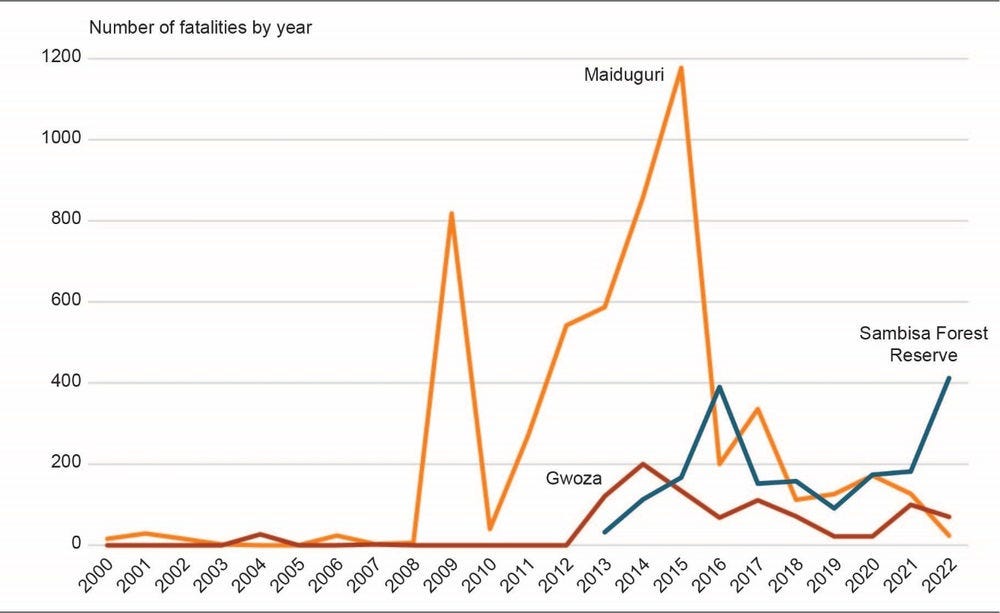

Boko Haram’s physical presence in Maiduguri appeared to weaken starting in 2013-2014, amid the rise of the CJTF, yet the group nevertheless repeatedly targeted the city. Violence in Maiduguri has had two peaks during the Boko Haram crisis: 2009 and 2015. The 2009 peak represents Boko Haram’s mass uprising (818 fatalities, although some estimates are much higher). 2010 was a low point in violence in Maiduguri (40 fatalities) as Boko Haram recovered, and then violence ticked upwards each year until 2015 (1 177 fatalities). A substantial portion of the violence represents casualties inflicted on Boko Haram and on civilians accused of being Boko Haram supporters; for example, the Nigerian Army reportedly killed an estimated 600 people in crackdowns after the 2014 Giwa Barracks attack.

In 2014-2015, Boko Haram carved out a “proto-state” in north-eastern Nigeria that partly encircled Maiduguri. Although Boko Haram never captured Maiduguri, the group inflicted numerous attacks on the city during and after that period. The most infamous attacks, although not always the ones with the highest casualties, were a spate of suicide bombings often involving women and girls as bombers under varying degrees of coercion and manipulation (Warner and Matfess, 2017[25]). Another, more recent trend is rocket attacks on the city. The area around the city has also been a site of serious violence, for example a November 2020 massacre that killed an estimated 110 agricultural workers in the village of Koshebe near Maiduguri.

Maiduguri has also seen an influx of displaced persons during the Boko Haram crisis, with the relative safety and denser humanitarian infrastructure of the city providing some relief to those fleeing Boko Haram and ISWAP attacks in smaller towns and in the countryside. As of April 2022, Borno State had over 1.6 million IDPs (IOM, 2022[26]). Nigerian authorities, however, have consistently and often controversially tried to promote resettlement of IDPs (and refugees), including controversial plans announced in 2020 to resettle an estimated 1.8 million people from camps in Maiduguri, with a wave of closures affecting camps in late 2021 (HRW, 2021[27]). As of April 2022, Borno State had 1.8 million returnees (IOM, 2022[26]), although returnees often faced dangerous conditions in their hometowns and villages.

Gwoza, a key flashpoint of the Boko Haram insurgency

Gwoza is the administrative centre of a Local Government Area (LGA) of the same name in Borno State, also in far north-eastern Nigeria. As of 2015, the Gwoza urban agglomeration had an estimated population of 69 600. Gwoza lies at the foot of the Mandara Mountains, a range along the Nigeria-Cameroon border, and the rugged geography around Gwoza has compounded both counterinsurgency and humanitarian access challenges there.

Gwoza has been a key flashpoint in the Boko Haram conflict. An early source of Boko Haram recruits, it was a site where members and fighters attempted to regroup after facing setbacks in other parts of the north-east in 2003. In Boko Haram’s formative period in the early 2000s, a segment or offshoot of the group – dubbed the “Nigerian Taliban” by the media – was involved in violence in Yobe and Borno States, including a September 2004 attack on Gwoza’s police station and a police station in Bama. After crackdowns on Boko Haram in Maiduguri by the military starting in 2011, and by the government-backed CJTF starting in 2013, some Boko Haram members again fled to the area around Gwoza, including the nearby Sambisa Forest. Boko Haram then launched a rapid series of assaults on schools and civilians in Gwoza, and southern Borno more broadly, which has a significant Christian population. Boko Haram preyed on civilians in general, and frequently killed Muslims it labelled apostates and enemies, but some of the violence in Borno, including in Gwoza, was specifically anti-Christian.

Boko Haram’s violence around Gwoza in 2013-2014, and in south-central Borno during that period, set the stage for Boko Haram’s overt territorial conquests beginning in summer 2014. Boko Haram began seizing towns, such as Damboa in July 2014, in part to deprive the CJTF of bases. Gwoza became the de facto headquarters of Boko Haram’s “proto-state” from August 2014 to March 2015. It was one of the last towns held by Boko Haram to fall to a multinational campaign, although areas around Gwoza remained under Boko Haram control even after the formal liberation of the town itself (HRW, 2016[28]).

Overall, 2013-2015 brought significant violence to Gwoza, with 121 fatalities in 2013, 200 in 2014 and 134 in 2015 (Figure 5.11). The surrounding area has been even more violent, and several villages in the Gwoza LGA saw one of the worst massacres of the conflict. Almost 1 700 people were killed within 20 km of Gwoza from 2011-2021 and nearly 8 500 within 50 km, according to ACLED. The town of Pulka, approximately 18 kilometres north of Gwoza and within Gwoza LGA, has also suffered heavily in the crisis (UNOCHA, 2020[29]).

Figure 5.11. Fatalities in the Lake Chad region by (urban) area, 2000-22

Note: 2022 data are projections based on a doubling of the number of events recorded through 30 June.

Source: Authors, based on ACLED (2022[2]) data. ACLED data is publicly available.

Boko Haram’s predatory and destructive occupation of Gwoza caused long-term challenges for residents and returnees, with an estimated 70% of the town “razed” by occupiers (Caux, 2016[30]). In the years after 2015, Gwoza and its region faced severe and persistent food security challenges. Through the time of writing in 2022, much of Gwoza LGA was classified as “hard to reach,” and the limited data available to humanitarian groups indicated that people were dying of hunger in Gwoza and other nearby LGAs, as they exhausted coping strategies, such as foraging (REACH, 2020[31]). As of the 2022 lean season (June-September), the worst food insecurity in Borno was in far northern LGAs – classified as level 4, “emergency,” on a widely used five-point scale – but Gwoza and much of the rest of the state were at level 3, “crisis” (FEWS Net, 2022[32]).

After its recapture by the Nigerian military in 2015, Gwoza became one of the military’s “garrison towns” with a “super camp” – part of a strategy the military began implementing in the north-east and particularly in Borno in 2017 (Carsten and Lanre, 2017[33]), with the idea of defending strategic towns against Boko Haram and ISWAP. The disadvantage of the “garrison towns” strategy was that it effectively meant ceding the countryside to militants, as occurred in the area around Gwoza, with significant disruption to farming activities (Ugoh, 2021[34]). The arrival of Nigerian soldiers also brought its own risks for residents, including reported patterns of sexual violence by soldiers. Some “garrison towns,” moreover, have been overrun by ISWAP, such as Dikwa in March 2021.

The Sambisa Forest as an enduring safe haven

The Sambisa Forest is a former colonial-era game preserve that is part of Nigeria’s Chad Basin National Park. The forest covers a band of forestation and scrubland in south central Borno State, of approximately 518 square kilometres. It became an integral part of the Boko Haram conflict from approximately 2013 on, as the group sought refuge in rural areas and medium-sized north-eastern Nigerian towns, amid a military and vigilante campaign against it in Maiduguri (Marama, 2014[35]). The safe haven Sambisa offered allowed Boko Haram to inflict mass violence in a swath of south-central Borno. Some of its most infamous attacks occurred in the vicinity of Sambisa, particularly the April 2014 kidnapping of 276 girls from the Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok, many of whom were held in Boko Haram hideouts in Sambisa.

Some urban agglomerations around Sambisa have been among the most violence-prone areas in northwest Africa in the period 1997-2021, including Damboa (1 490 fatalities), Konduga (1 122), and Gwoza (891). From its base in Sambisa, Boko Haram was eventually able, in 2014-2015, to temporarily conquer some towns in the area at the edges of the forest, including Damboa, Gwoza and Bama, although its proto-state reached far beyond the forest. The 2014 apex of violence in areas around Sambisa reflects Boko Haram’s territorial conquests and almost indiscriminate violence at the height of its power.

The forest has also been the target of recurring air and ground campaigns by the Nigerian military, including in 2015, when Nigeria, Chadian and Niger joined forces to dismantle Boko Haram’s proto-state. In December 2016, partly to fulfil campaign promises made in 2015, Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari announced that Boko Haram’s last camp inside Sambisa had been destroyed. Nevertheless, the forest remained the key stronghold for Boko Haram, especially the faction of Abubakar Shekau (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. Internal struggle within the Boko Haram insurgency

The group’s top leader from 2009 to 2016, Shekau’s power was dramatically challenged in 2015-2016, in what became an enduring split. The internal conflict within Boko Haram concerned Shekau’s authoritarian ruling style and expansive use of violence both against outsiders and internal dissidents. This conflict intersected with internal disagreements over how to manage the relationship with the Islamic State, to which Boko Haram pledged allegiance in March 2015, despite some reluctance by Shekau. Boko Haram’s territorial losses in early 2015, and the desperate conditions the group found itself in during 2015-2016, as it regrouped in Sambisa, widened the internal tensions.

In August 2016, Boko Haram split, and the Islamic State shifted its patronage to a faction formally headed by Abu Musab al-Barnawi, reportedly a son of Boko Haram’s founder, Muhammad Yusuf. The breakaway faction, ISWAP, took most Boko Haram fighters with it, and concentrated its operations in northern Borno and the wider Lake Chad Basin. Shekau’s faction of Boko Haram kept on fighting, under the name Jama‘at Ahl al-Sunna li-l-Da‘wa wa-l-Jihad or JAS. The split left Sambisa and parts of southern and eastern Borno to Shekau’s rump Boko Haram faction, although discerning whether ISWAP or Shekau’s Boko Haram/JAS was responsible for any given attack in the period 2016-2021 could be difficult.

In May 2021, an ISWAP offensive on Sambisa ended in the death of Shekau and an exodus of Boko Haram/JAS fighters to Nigerian military surrender programs. That it was ISWAP that was responsible for Shekau’s death – rather than the military – spoke to Nigeria’s long-running inability to curtail Boko Haram’s activities, including within Sambisa. As of 2022, Boko Haram/JAS persists in some form.

Source: Alexander Thurston for this publication.

Nigerian authorities and vigilantes continue to mobilise to fight Boko Haram in the Sambisa Forest, and not just from the air. In 2019, Borno State’s new governor, Babagana Zulum, backed an initiative to organise traditional hunters to chase Boko Haram to its remote hideouts, with the goal of mobilising as many as 10 000 hunters (Umar, 2019[36]). Hunters’ efforts have reportedly resulted in some disruptions to Boko Haram’s activities in and around Sambisa, killing Boko Haram fighters and seizing their supplies.

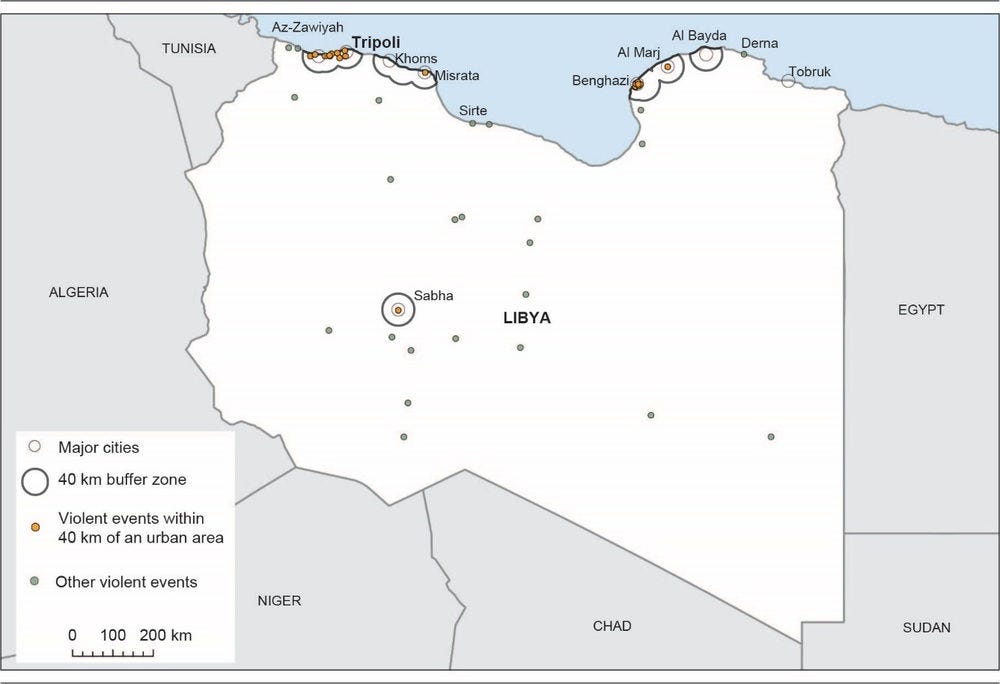

Declining urban violence in Libya

Libya has experienced more than a decade of political instability since popular protests against the regime of long-time ruler Muhammar Gaddafi (in power 1969-2011) started in February 2011. The First Libyan Civil War ended after nine months of intense battles between the government and various rebel forces. This first conflict was marked by the military intervention of NATO’s Operation Unified Protector, which ultimately resulted in a bombing campaign to destroy government forces and enforce the United Nations-mandated no-fly zone.

The First Libyan Civil War was followed by a second conflict initiated with the launch of Operation Dignity in May 2014 by Khalifa Haftar, a retired military officer. Tensions rose further in 2014 with disputed parliamentary elections in June, which split the country’s political class into two main rival governments. One government was the internationally recognised House of Representatives, based in Tobruk and aligned with Haftar and what came to be called the Libyan National Army (LNA) or Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF). The other government was the National Salvation Government, supported by a coalition of anti-Haftar militias called Operation Dawn.

After a lengthy military campaign essentially focused on urban areas, the Second Libyan Civil War ended with the signature of a permanent ceasefire between the LNA and the Government of National Accord (GNA) in October 2020, and the formation of a Government of National Unity (GNU) in March 2021. Unlike in the Central Sahel and Lake Chad region, where violence is intensifying and becoming more rural, violent events have reached historic lows in Libya in recent years and remained urban in character (Map 5.5).

Tripoli as site of both local and national contestation

Tripoli is Libya’s most populous city, with an estimated population of 2 million in 2015. The urban agglomeration has been the most violence-prone in North and West Africa, with 6 045 fatalities during the 1997-2021 period, virtually all from the beginning of the First Libyan Civil War, according to ACLED. This violence reflects the political prize that Tripoli represents amid the severe fragmentation of post-Gaddafi Libya. Tripoli is a site of local contestation between different locally based militias as well as national contestation between different major factions.

The three peaks of violence in Tripoli correlate with moments of national upheaval. First was the 2011 revolution, which brought intense violence to the city and its suburbs (2 035 fatalities) as Gaddafi loyalists sought to hold the capital against the revolutionaries. NATO-backed rebels captured the city from the Gaddafi regime in August. Second, in the 2014 civil war (857 fatalities in Tripoli), intense fighting took place in the agglomeration between Operation Dawn-affiliated militias and their rivals in July and August. In this period, a battle for Tripoli International Airport pitted Operation Dawn against militias from the city of Zintan, who had controlled the airport until then. The fighting at the airport spilled over into densely populated civilian neighbourhoods, with many casualties from shelling, land mines and street fighting (United Nations, 2014[37]).

Map 5.5. Violent events and urban areas in Libya, 2020-22

The third peak of violence in Tripoli came amid Haftar’s unsuccessful 2019-2020 campaign to capture Tripoli (1 173 fatalities in Tripoli in 2019, and 725 in 2020). The campaign, which pitted Haftar’s LNA against forces of the United Nations-backed GNA, also involved substantial outside interventions by a range of actors sponsoring different sides of the conflict; the Republic of Türkiye's intervention was ultimately key in repulsing Haftar’s forces (Pack and Pusztai, 2020[38]). In March 2021, the GNA was dissolved and subsumed into the GNU, an internationally recognised structure meant to unify the GNA and the Tobruk-based House of Representatives. The compromises underlying the GNU, however, broke down after interim Prime Minister Abdulhamid al-Dbeibah announced, in November 2021, that he would run for president in the anticipated 2022 elections. The fracture between Tripoli and Tobruk re-emerged, with the House of Representatives seeking first to oust Dbeibah in February 2022 and then to create (or resume) its own parallel government (Mcdowall, 2022[39]). Conflict between Dbeibah and the parliament’s new choice for prime minister, Fathi Bashagha, started fighting in Tripoli in March 2022.

Amid national-level contestation, Tripoli has also been a key site for local militia activities. Libya’s early post-revolutionary authorities sought to tame the many militias formed during and after the revolution. However, the decision to pay and legitimate some militias inadvertently incentivised the further spread of militias as a political force in many cities, including Tripoli. Hybrid government-militia initiatives such as the Libya Shield Force and the Supreme Security Committees failed to generate a cohesive security structure for the country (Wehrey and Cole, 2013[40]). In the capital, the number of major militias fell over time, as a few groups consolidated power. By 2018, the city had a “big four”, made up of the Tripoli Revolutionaries Battalion, the Abu Salim Battalion, the Nawasi Battalion and the Special Deterrence Forces.

These militias reflected a mix of personalistic, ideological, geographical and political interests. All of them came to a degree of accommodation with the UN-backed GNA after its establishment in 2016 (Eaton et al., 2020[41]). For example, the Special Deterrence Forces of Abd al-Ra‘uf Kara, which have a Salafi character, developed affiliations with the GNA’s Ministry of the Interior in 2018 and later with the GNA’s Presidential Council in 2020. Relations between militias have been unstable; for example, in June 2022, there was fighting in Tripoli between the Nawasi Battalion and the Stability Support Authority, a successor structure to the Abu Salim Battalion, as the militias aligned themselves with Dbeibah and Bashagha. The way that national rivalries reverberate in Tripoli has been particularly lethal for civilians there. All of Tripoli’s major militias have committed human rights violations (Amnesty International, 2021[42]).

Benghazi, the initial epicentre of the 2011 revolution

Benghazi is Libya’s second most populous city, with an estimated 594 300 people in 2015. The city is the political hub of eastern Libya, a region sometimes referred to as Cyrenaica, which was the political base of the Libyan monarchy from 1951 to 1969. Under Colonel Gaddafi, however, Benghazi and Cyrenaica faced marginalisation and repression. Partly because of these longstanding grievances in the east, Benghazi was the initial epicentre of the 2011 revolution beginning in February, amid the Arab Spring revolutions. Concerns that Gaddafi was planning to massacre protesters in Benghazi became a key justification cited for NATO’s intervention in Libya starting in March. French, British and American airstrikes were instrumental in repulsing Gaddafi’s offensive against Benghazi that month (Abbas, 2011[43]). Holding Benghazi then allowed rebels to advance, link up with other rebelling cities and, with continued NATO support, capture Tripoli and topple Gaddafi. Benghazi was also the first headquarters of the National Transitional Council (NTC), which became Libya’s interim government in 2011-2012.

Benghazi is the third most violence-prone urban agglomeration in this study, with 3 842 fatalities recorded in the period 1997-2021, per ACLED data. The city has remained a key site of violence through successive iterations of civil war. As militias proliferated in post-Gaddafi Libya, Benghazi was initially home to numerous militias, including a branch of the jihadist-leaning group Ansar al-Sharia (Supporters of Islamic Law). An idiosyncratic figure loosely affiliated with Ansar al-Sharia, Ahmed Abu Khattala of the Abu Obeida bin al-Jarrah Brigade, played a leading role in the 2012 violence that led to the deaths of four Americans at the United States consulate in Benghazi (United States Department of Justice, 2018[44]). Meanwhile, the early years after the 2011 revolution saw waves of assassinations in Benghazi, amid a murky competition for power. The assassinations often targeted civil society activists and media personalities. Several of the most visible victims have been women (HRW, 2014[45]), such as the lawyer and human rights activist Salwa Bughaighis, who was shot on election day, 25 June 2014.

In May 2014, the retired Libyan officer Khalifa Haftar launched Operation Dignity, an ostensible counterterrorism operation but with political goals. Haftar, from the eastern Libyan city Ajdabiya, made the east his base. In 2015, Libya’s eastern-based government, the House of Representatives, appointed Haftar head of the LNA. Haftar has received support at various points from outside powers such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, Russia, France and the United States.

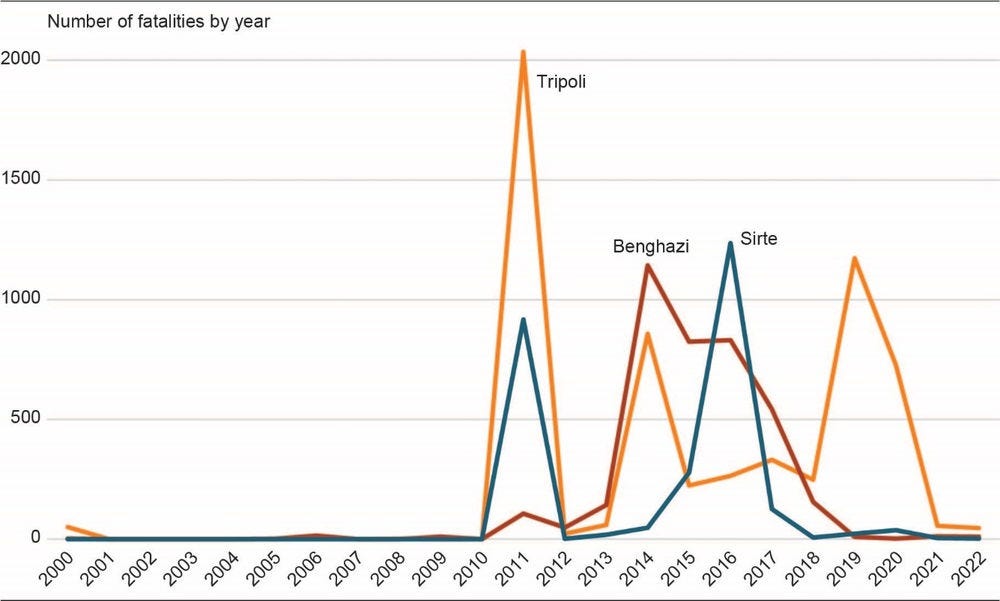

After launching Operation Dignity, Haftar began seeking to consolidate control over Benghazi as part of his eastern Libyan power base. He clashed with Islamist and jihadist militias, especially the coalition called the Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries (SCBR), which included Ansar al-Sharia as well as more mainstream rebel and Islamist groups. Such fighting made 2014 the most violent year in Benghazi, with 1 143 fatalities, and the three following years also saw substantial fatalities (824 in 2015, 831 in 2016 and 542 in 2017, according to ACLED (Figure 5.12). The fighting over individual neighbourhoods in Benghazi, such as Ganfouda, was often protracted and fierce, with substantial casualties on both sides and with significant use of LNA airstrikes. In July 2017, Haftar announced the “liberation of Benghazi”, which in turn allowed him to focus on capturing other eastern Libyan cities, such as Derna, and then prepare his (ultimately unsuccessful) bid to capture Tripoli in 2019-20.

Figure 5.12. Fatalities in Libya by (urban) area, 2000-22

Note: 2022 data are projections based on a doubling of the number of events recorded through 30 June.

Source: Authors, based on ACLED (2022[2]) data. ACLED data is publicly available.

Haftar’s forces committed massive human rights violations amid their campaign to control Benghazi and conquer other eastern Libyan cities. The International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants in 2017 and 2018 for one of Haftar’s top lieutenants, Mahmoud Al-Warfalli, after evidence emerged of summary executions by him and his forces in Benghazi and elsewhere. The case was dropped when Al-Warfalli died in 2021. Outside observers also charged that Haftar’s rule produced “a half-ruined city beset by corruption, where security agents trailed foreign journalists, residents cowered in fear of arbitrary arrest, and pro-government militias answered to no one” (Kirkpatrick, 2020[46]). There have been periodic anti-Haftar protests in Benghazi and elsewhere, for example in September 2020. Haftar’s own coalition, meanwhile, included diverse factions: loyalists, former revolutionaries, eastern secessionists, certain tribes and certain Salafi; this coalition proved fractious at times (Eaton, 2021[47]).

Sirte, the Islamic State’s longest-lasting urban base

Sirte is a mid-sized city on Libya’s Mediterranean coast, with an estimated population of 59 100 in 2015. Sirte was the adopted hometown of Colonel Gaddafi and his last stronghold during the 2011 revolution. Gaddafi was captured and killed in October by a militia of fighters from the Libyan city Misrata, a key revolutionary bastion, as he was attempting to flee Sirte. Misratan militias were accused of committing serious human rights violations in Sirte, including extrajudicial killings, which targeted not just Gaddafi and his fighters but also perceived Gaddafi loyalists more broadly (HRW, 2012[48]). Residents of Sirte accused Libya’s new authorities of blocking compensation and reconstruction efforts there in the aftermath of the revolution (Westcott, 2018[49]).

Revolutionaries’ harsh treatment of Gaddafi’s perceived support bases helped set the stage for a backlash. Beginning in 2014, Islamic State fighters began circulating in Sirte. In 2015-16, Sirte formally fell under the control of the Islamic State’s Libyan affiliate (IS-L) and proved to be the group’s longest-lasting urban base, especially after IS-L fighters were driven from the city of Derna in 2015 by rival jihadists and militias. In Sirte, IS-L took advantage of the way the city fell between the emerging zones of control for the two main rival governments in Libya, and assembled a coalition of jihadists, former Gaddafi loyalists and tribes, while inflicting substantial violence and human rights violations on ordinary residents. IS-L abuses in Sirte included summary executions of alleged spies and apostates, as well as a broader system of intimidation, looting, hoarding of basic supplies and interference with education and other elements of daily life (HRW, 2016[50]).

In May 2016, Libya’s then-GNA, based in Tripoli, launched Operation Bunyan Marsus (“Solid Structure”) to defend Misrata against creeping IS-L incursions and to crush IS-L in Sirte, using fighters from Misratan militias (Wehrey, 2016[51]). The United States carried out an estimated 495 air and drone strikes on Sirte to support the campaign (Bergen and Sims, 2018[52]). The campaign to dislodge IS-L was successful, and Sirte was recaptured from IS-L in December 2016 by GNA forces. However, it also showcased rivalries between the GNA and the forces of Khalifa Haftar, with both factions vying for the anti-jihadist mantle.

The violence inflicted by IS-L, Bunyan Marsus and the airstrikes made 2016 the most violent year in Sirte (1 236 fatalities, even higher than the 917 fatalities during the revolution in 2011) and helped make Sirte the fifth-most violent urban agglomeration included in this study (2 691 fatalities during the period 1997-2021). Two-thirds of Sirte residents fled the city due to the combination of IS-L abuses and the violence of the anti-IS effort, and at least 19 000 families were displaced between June 2015 and December 2016 (Zargoun, 2016[53]). The campaign left Sirte in “utter destruction” (Westcott, 2018[49]). Politically and militarily, the GNA left Sirte awkwardly governed by rival militias, such as the Misratan-staffed Protection Force and the tribal-based, Salafi-leaning 604th Infantry Brigade. After its defeat in Sirte, IS-L conducted some attacks in nearby areas, with Haftar’s forces targeting the jihadists, and concentrated its efforts in more remote areas of southern Libya, where IS-L and rival jihadists in Al Qaeda were repeatedly targeted by American airstrikes (Salyk-Virk, 2020[54]).

Since the fall of IS-L in Sirte, the city has periodically played major roles in Libyan politics and warfare. Amid Haftar’s campaign to capture Tripoli, his LNA targeted Sirte from September 2019 on. In January 2020, the LNA announced that it had captured Sirte in a “lightning” offensive. Haftar’s forces displaced the GNA-aligned Sirte Protection Force, which abandoned the city without a serious fight. Haftar also secured the defection of the 604th Infantry Brigade and other key Sirte-based factions (Al-Hawari, 2021[55]). Indeed, 2020 fatalities were relatively low (37) in the city. Amid GNA efforts to advance eastward and push back Haftar’s LNA, Sirte became a bargaining chip in the negotiations over a ceasefire, in part due to its strategic location near key oil fields and terminals in Libya’s “oil crescent.” Ultimately, the October 2020 agreement included a provision that the parties would guarantee the reopening of a coastal highway linking Tripoli and Benghazi, running through Misrata and Sirte (United Nations, 2020[56]). In March 2022, amid a breakdown of efforts at a national unity government, one of Libya’s rival prime ministers, Fathi Bashagha, based his government in Sirte after he was blocked from taking over Tripoli.

Jihadist insurgencies and cities

This study suggests that the relationship between cities and political violence varies considerably across and within states in North and West Africa. While most violent events tend to occur in close proximity to urban areas at the regional level, some states, such as Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, seem to involve more rural conflict than others. The fact that these three countries follow the same trend is hardly surprising, since all of them are currently confronted with major jihadist insurgencies.

Since they emerged in the region in the 2000s, jihadist organisations have maintained an unusual relationship with cities. Some jihadist groups began as urban movements – notably Boko Haram, whose epicentre was Maiduguri until 2009, but also Burkina Faso’s Ansaroul Islam, whose founder, Ibrahim Dicko, initially used Djibo as a base. Other jihadist groups, such as AQIM, deliberately sought out remote hideouts during the 2000s, raiding military outposts and kidnapping Westerners and others in the deep Sahara. Jihadists also sometimes adduce moral reasons for preferring the countryside, condemning cities for their alleged vices, the financial and moral corruption of urban elites, and the visibility and prevalence of Western values in fashion, culture, education and politics. Cities in the region have also sometimes been denounced by jihadists as bastions of secularism.

When the opportunity arises, however, jihadist organisations have sought out urban footholds, as AQIM and its allies did during the 2012 crisis in northern Mali. In some cases, these movements also reshape the physical and moral landscapes of cities, for example by destroying the religious manifestations of older religious orders, like the shrines in Timbuktu destroyed by Ansar Dine and allies in 2012. Sporadic terrorist attacks on capitals and other major cities, meanwhile, can have serious propaganda value for jihadists, temporarily capturing the attention of national governments and making national and even global headlines. Some jihadist groups have oscillated between urban and rural orientations, meanwhile, depending on the opportunity structures and levels of repression.

Such oscillation reflects, in a loose way, broader patterns in the relationship of Islamic reformist movements and cities. Islam has been called a fundamentally urban religion, given its origins in Mecca and Medina and the constellation of cities and garrison towns – Damascus, Kufa, Fustat and elsewhere – that anchored the early Islamic empire. In north-west Africa, Islamisation was a heavily urban phenomenon as well, as traders and scholars clustered in sites from Fez in present-day Morocco to the Hausa city-states in present-day Nigeria (Last, 2013[57]). In some rural areas of West Africa, mass Islamisation in the countryside only occurred in the twentieth century, partly due to the unplanned consequences of colonialism and the attendant rise in the circulation of people and ideas due to forced labor, migration, military service and other factors (Peterson, 2011[58]).

At the same time, the spiritual pull of rural areas and more limited interaction with the mass of humanity has been strong since the earliest moments of Islam, starting with the Prophet Muhammad’s retreats to the cave of Hira immediately preceding the advent of his prophethood, and continuing with the social withdrawal of ascetic-minded Companions such as Abu Dharr al-Ghifari. In north-west Africa, too, major spiritual figures and reformers have sometimes sought out retreats in desert and rural areas, like Muhammad bin Ali al-Sanusi in what is now Jaghbub, in present-day Libya, and Usman dan Fodio in Gudu, the launching point of his 1804 jihad, in today’s northern Nigeria. The idea of making a religious emigration (hijra) from a corrupted city to a new destination, urban or rural, is a core Islamic concept, and one that reformers have repeatedly used to link their own careers to that of the Prophet Muhammad and his hijra from Mecca to Medina in CE 622. Jihadists, too, have played on those early Islamic vocabularies, depicting their own withdrawal from mainstream society as a form of hijra and depicting foreign fighters as “Ansar,” or helpers, a reference to the Medinan Muslims in the time of the Prophet.

Colonial and postcolonial reformist movements in north-west Africa, which have had a major impact on Muslim religiosity on the continent (Loimeier, 2016[59]), have also had a complex relationship with cities and the countryside. On the whole, Islamic reformism in the region has had an urban orientation, from the “Wahhabiyya” of late colonial Mali and Guinea, whose network spanned cities such as Ségou, Bamako and Kankan, to the Izala movement of northern Nigeria and southern Niger, whose centres include Jos, Kano and Maradi (Grégoire, 1993[60]; Kane, 2003[61]; Ben Amara, 2020[62]). Cities are connected to each other through trade routes, moreover, allowing reformist movements to spread from one location to another.

Not only have cities provided bases for mass recruitment and for the funding opportunities represented by an urban merchant elite, but they are also laboratories where reformist movements try out new social norms, prohibitions and dress codes, especially those for women (Masquelier, 2009[63]). The cosmopolitan character of cities has allowed reformists to recruit along ethnically diverse lines and to benefit from generational fault lines that sometimes predispose youth to challenge traditionalism. Cities also provide arenas where reformists can demonstrate their political and social relevance in mass mobilisations and protests, for example amid the protests against revisions to the family code in Mali in 2009-12. The sharia movement in northern Nigeria, partly driven by reformist activism, was also predominantly urban.

The importance of cities in the spread and the life of religion means that the current ruralisation of conflict in the Sahel can only be temporary. If reformist or jihadist movements wish to achieve their goal of profoundly reforming Sahelian societies, recruitment from rural populations cannot be sufficient. Moreover, the weakening of Sahelian and other West African states could widen opportunities for jihadists to make renewed bids for conquering urban areas. The evolution of jihadist tactics can also be seen in the blockades set up around Djibo and other Sahelian cities in recent years; jihadists are developing approaches that apply profound pressure to major towns without bidding for overt governance there. It can therefore be expected that conflicts over the control of cities will intensify.

Perspectives

This report suggests how varied the importance of cities and urban areas are over the duration of a conflict. Urban settings may prove to be crucial to a deeper understanding of the overall life cycle of conflict, as noted in Chapter 2. The spatial conflict life cycle theory holds that conflicts in the region tend to be more spatially diffuse and less intense as a conflict emerges, more intense and concentrated as it matures, and then again more diffuse and less intense near its end. Interrogating the relationship of certain typologies of political movements would be a productive way to assess the role of urban areas in this broader notion of a conflict life cycle.

As a consideration of jihadist movements suggests, certain types of movements and groups will have distinct relationships, motivations and overall goals related to urban areas, which can produce spatial patterns of violence. For instance, Boko Haram’s ambivalence about urban contexts has led to a proliferation of more diffuse, although still quite intense, violence in rural and semi-urban locations. Conversely, the early stages of the MNLA’s revolt in Mali led to concentrated and intense episodes of attacks on major cities, thanks to its objective of seizing key sites of political and economic control. Similar dynamics have played out throughout the Libyan Civil Wars.

More work is needed to unravel the complexities surrounding the importance of cities and urban areas in the conflict life cycle, but starting with an interrogation of the kind of violent non-state groups involved and the different motivations that underpin their efforts would be a good way to begin. For example, it remains unclear whether secessionist rebels and jihadist groups share the same strategic objectives when it comes to attacking urban areas. From this perspective, it is reasonable to expect that urban areas are likely to remain strategic places to conquer or control for a given conflict episode, but that they should also be expected to matter differently, and at different moments in time, from state to state and conflict to conflict within North and West Africa.

References

[43] Abbas, M. (2011), “Remains of Gaddafi’s force smolders near Benghazi”, Reuters, 20 March, https://www.reuters.com/article/ozatp-libya-east-devastation-20110320-idAFJOE72J08C20110320.

[2] ACLED (2022), Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (database), https://acleddata.com.

[21] Agbiboa, D. (2022), Mobility, Mobilization, and Counter/Insurgency: The Routes of Terror in an African Context, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11472497.

[55] Al-Hawari, O. (2021), “How Sirte Became a Hotbed of the Libyan Conflict”, Middle East Directions, No. 5, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2870/177834.

[42] Amnesty International (2021), “Libya: Ten Years After Uprising Abusive Militias Evade Justice and Instead Reap Rewards”, 17 February, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/libya-ten-years-after-uprising-abusive-militias-evade-justice-and-instead-reap-rewards-2/.

[24] Amnesty International (2011), “Nigeria: Unlawful Killings by the Joint Military Task Force in Maiduguri Must Stop”, 14 July, https://www.amnesty.org/fr/documents/afr44/013/2011/fr/.

[62] Ben Amara, R. (2020), The Izala Movement in Nigeria: Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival, Göttingen University Press, Göttingen, https://doi.org/10.17875/gup2020-1329.

[52] Bergen, P. and A. Sims (2018), “Airstrikes and Civilian Casualties in Libya Since the 2011 NATO Intervention”, New America, 20 June, https://www.newamerica.org/international-security/reports/airstrikes-and-civilian-casualties-libya.

[23] Bukarti, A. (2020), “The Origins of Boko Haram – And Why It Matters”, Hudson Institute Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, 13 January, https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/the-origins-of-boko-haram-and-why-it-matters.

[33] Carsten, P. and O. Lanre (2017), “Nigeria Puts Fortress Towns at Heart of New Boko Haram Strategy”, Reuters, 1 December, https://www.reuters.com.

[30] Caux, H. (2016), “Fear and Shortages as Boko Haram Displaced Return to Ruins”, United Nations High Commission for Refugees, 23 September, https://www.unhcr.org/fr-fr/news/stories/2016/9/57e93991a/crainte-penuries-personnes-deracinees-boko-haram-retour-maisons-ruines.html?query=boko%20haram.

[67] CSIS (2022), “Massacres, Executions, and Falsified Graves: The Wagner Group’s Mounting Humanitarian Cost in Mali”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, D.C., 11 May, https://www.csis.org/analysis/massacres-executions-and-falsified-graves-wagner-groups-mounting-humanitarian-cost-mali.

[10] Dreazen, Y. (2013), “Welcome to Cocainebougou”, Foreign Policy, 27 March, https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/03/27/welcome-to-cocainebougou.

[47] Eaton, T. (2021), “The Libyan Arab Armed Forces”, Chatham House, 2 June, https://smartthinking.org.uk.

[41] Eaton, T. et al. (2020), “The Development of Libyan Armed Groups Since 2014: Community Dynamics and Economic Interests”, Chatham House, March.

[32] FEWS Net (2022), “Nigeria: Key Message Update”, May, Famine Early Warning Systems Network, https://fews.net/fr/west-africa/nigeria/key-message-update/may-2022.

[60] Grégoire, E. (1993), “Islam and identity of merchants in Maradi (Niger)”, in Brenner, L. (ed.), Muslim Identity and Social Change in Sub-Saharan Africa, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp. 106-115.

[27] HRW (2021), “Nigeria: Halt Closure of Displaced People’s Camps”, Human Rights Watch, 21 December, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/12/21/nigeria-halt-closure-displaced-peoples-camps.

[16] HRW (2020), “Burkina Faso: Residents’ Accounts Point to Mass Executions”, Human Rights Watch, 8 July, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/07/08/burkina-faso-residents-accounts-point-mass-executions.

[28] HRW (2016), “‘They Set the Classrooms on Fire’: Attacks on Education in Northeast Nigeria”, Human Rights Watch, 11 April, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/04/11/they-set-classrooms-fire/attacks-education-northeast-nigeria.

[50] HRW (2016), “‘We Feel We Are Cursed’: Life Under ISIS in Sirte, Libya”, Human Rights Watch, 18 May, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/05/18/we-feel-we-are-cursed/life-under-isis-sirte-libya.

[45] HRW (2014), “Libya: Assassinations May Be Crimes Against Humanity”, Human Rights Watch, 23 September, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/09/23/libya-assassinations-may-be-crimes-against-humanity.

[48] HRW (2012), “Death of a Dictator: Bloody Vengeance in Sirte”, Human Rights Watch, 17 October, https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/10/16/death-dictator/bloody-vengeance-sirte.

[9] HRW (2012), “Mali: Islamist Armed Groups Spread Fear in North”, Human Rights Watch, 25 September, https://www.hrw.org.

[15] ICG (2017), “The Social Roots of Jihadist Violence in Burkina Faso’s North”, International Crisis Group, 12 October, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/burkina-faso/254-social-roots-jihadist-violence-burkina-fasos-north.

[26] IOM (2022), “Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM) Lake Chad Basin – Monthly Dashboard #43”, International Organization for Migration, 30 April, https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/regional-displacement-tracking-matrix-dtm-lake-chad-basin-crisis-monthly-dashboard-48-30-september-2022.

[65] ISS (2020), “Nigeria’s Super Camps Leave Civilians Exposed to Terrorists”, Institute for Security Studies, 30 November, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/nigerias-super-camps-leave-civilians-exposed-to-terrorists.

[61] Kane, O. (2003), Muslim Modernity in Postcolonial Nigeria: A Study of the Society for the Removal of Innovation and Reinstatement of Tradition, Brill, Leiden, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047401551.

[46] Kirkpatrick, D. (2020), “A Police State With an Islamist Twist: Inside Hifter’s Libya”, New York Times, 14 April, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/20/world/middleeast/libya-hifter-benghazi.html.

[17] Koné, A. (2020), “Burkina Faso: ces villes du nord sous embargo djihadiste”, Sahelien, 9 June, https://sahelien.com/burkina-faso-ces-villes-du-nord-sous-embargo-djihadiste.

[57] Last, M. (2013), “Contradictions in Creating a Jihadi Capital: Sokoto in the Nineteenth Century and Its Legacy”, African Studies Review, Vol. 56/2, pp. 1-20, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43904924.

[5] Lawrence, T. (1920), “The evolution of a revolt”, Army Quarterly and Defense Journal.

[59] Loimeier, R. (2016), Islamic Reform in Twentieth-Century Africa, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g050r6.

[35] Marama, N. (2014), “Inside Boko Haram’s Hideout: The Story of Sambisa Forest”, Vanguard, 27 April, https://www.vanguardngr.com/2014/04/inside-boko-harams-hideout-story-sambisa-forest.

[63] Masquelier, A. (2009), Women and Islamic Revival in a West African Town, Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

[39] Mcdowall, A. (2022), “Libya’s Dbeibah: The Ambitious Politician Who Promised Not to Be”, Reuters, 10 February, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/libyas-dbeibah-ambitious-politician-who-promised-not-be-2022-02-10.

[20] Mednick, S. (2021), “Burkina Faso’s Secret Peace Talks and Fragile Jihadist Ceasefire”, The New Humanitarian, 11 March, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/2021/03/11/exclusive-burkina-faso-s-secret-peace-talks-and-fragile-jihadist-ceasefire.

[64] OECD/SWAC (2022), Borders and Conflicts in North and West Africa, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6da6d21e-en.

[4] OECD/SWAC (2020), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en.

[8] OECD/SWAC (2014), An Atlas of the Sahara-Sahel: Geography, Economics and Security, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264222359-en.

[38] Pack, J. and W. Pusztai (2020), “Turning the Tide: How Turkey Won the War for Tripoli”, Middle East Institute Policy Paper, 10 November, https://www.mei.edu/publications/turning-tide-how-turkey-won-war-tripoli.

[58] Peterson, B. (2011), Islamization from Below: The Making of Muslim Communities in Rural French Sudan, 1880-1960, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

[31] REACH (2020), “Food Security and Livelihoods in Hard-to-reach Areas of Borno State, Nigeria”, August-September 2020, https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/food-security-and-livelihoods-hard-reach-areas-borno-state-nigeria-august-september.

[7] Retaillé, D. and O. Walther (2013), “Conceptualizing the Mobility of Space through the Malian Conflict”, Annales de Géographie, Vol. 694/6, pp. 595-618.