The spill-over effects of the war and sanctions have reverberated globally, through commodity price increases, trade disruptions, financial decoupling, migration, and humanitarian impacts. Central Asia’s trade and remittance connections with Russia are particularly tight, which made it one of the regions likely to be most affected.

Weathering Economic Storms in Central Asia

Introduction

Central Asian economies are closely integrated with Russia

Trade linkages

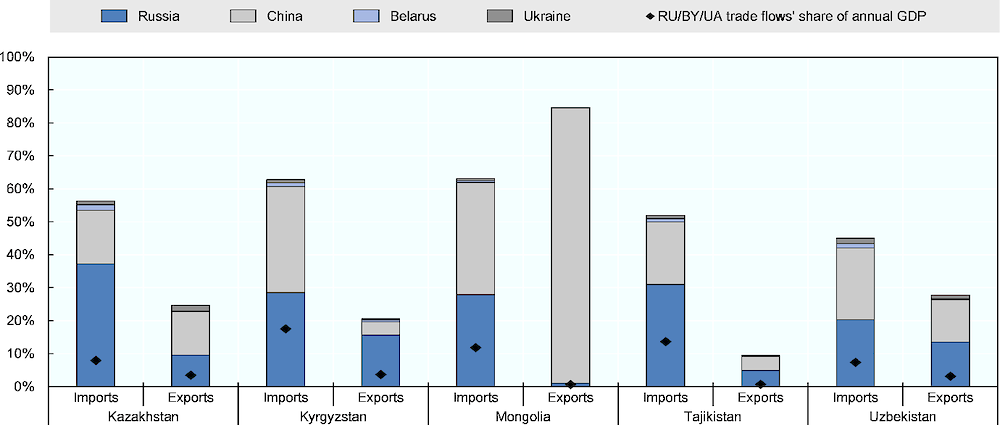

The trade profile of most Central Asian countries remains concentrated on a small number of partners and products for both imports and exports. In particular, Russian imports greatly outweigh exports across all Central Asian countries, the country being the region’s largest source of imports, except for Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia, where Russia ranks second behind China (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of trade flows from/to Russia, Belarus and Ukraine (average 2016-2021)

Note: Exports include both energy and non-energy goods. Belarus is responsible for 0% (Mongolia) to 0.5% (Kazakhstan) of Central Asia exports. Data for Turkmenistan has not been included due to reporting inconsistencies.

Source: (UNCTAD STAT, 2022[1])

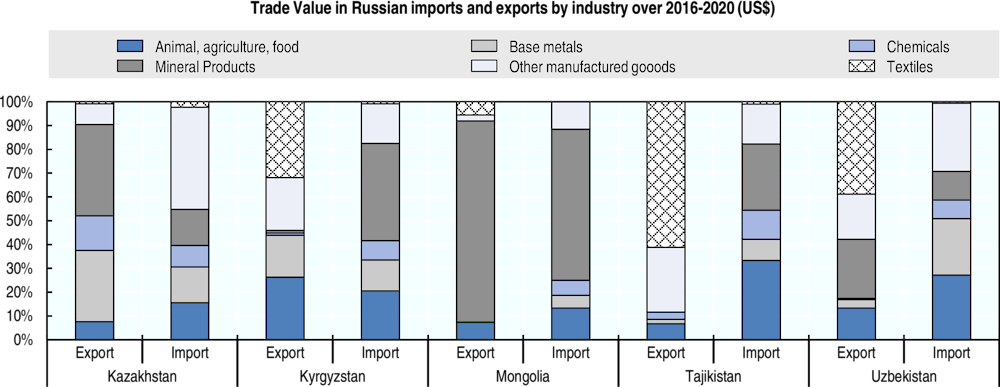

Imports are predominantly composed of mineral products, base metals and chemicals as well as electric machinery and food. On the export side, Russia is the largest destination for Kyrgyzstan and second for Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, buying mainly mineral products, textiles, base metals, and vegetables (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Sectoral composition of Russian imports and exports from/to Central Asia (2016-2020 average) and trade value (% of GDP, rhs)

Note: No data available for Turkmenistan. "Other manufactured goods" as defined by the European Commission includes Chemicals and Textiles. However, due to the importance of these two segments for the region, these two sectors are separated for visualisation purposes.

Source: (UN Comtrade, 2022[2]).

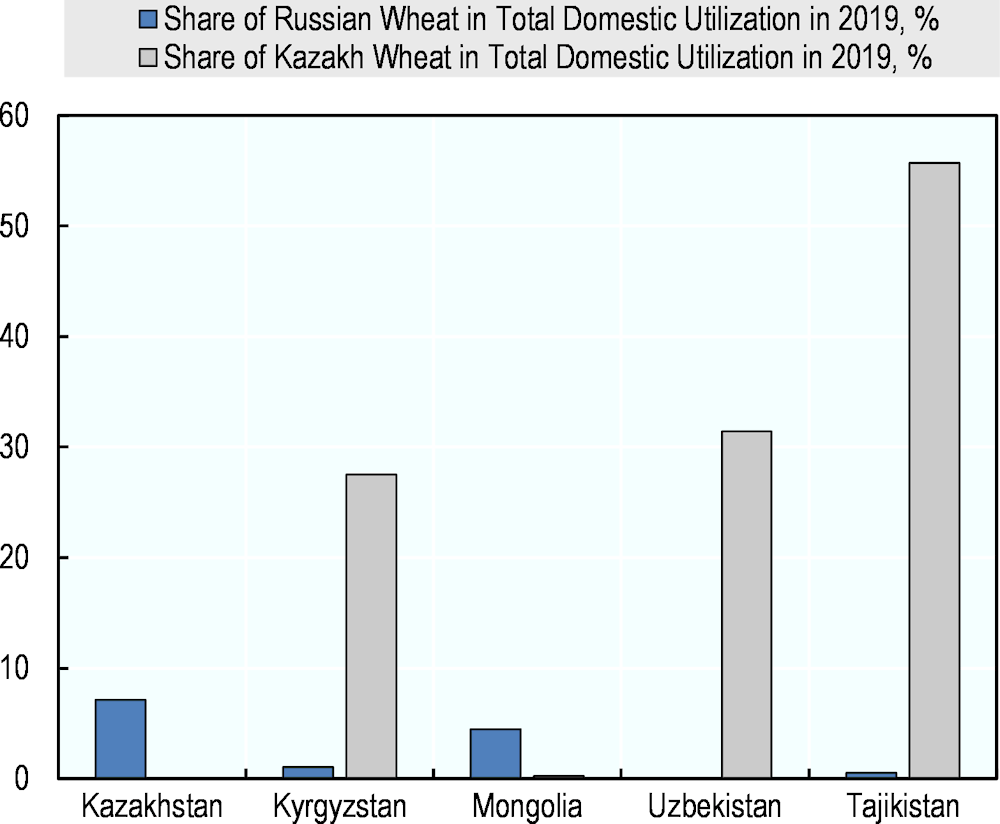

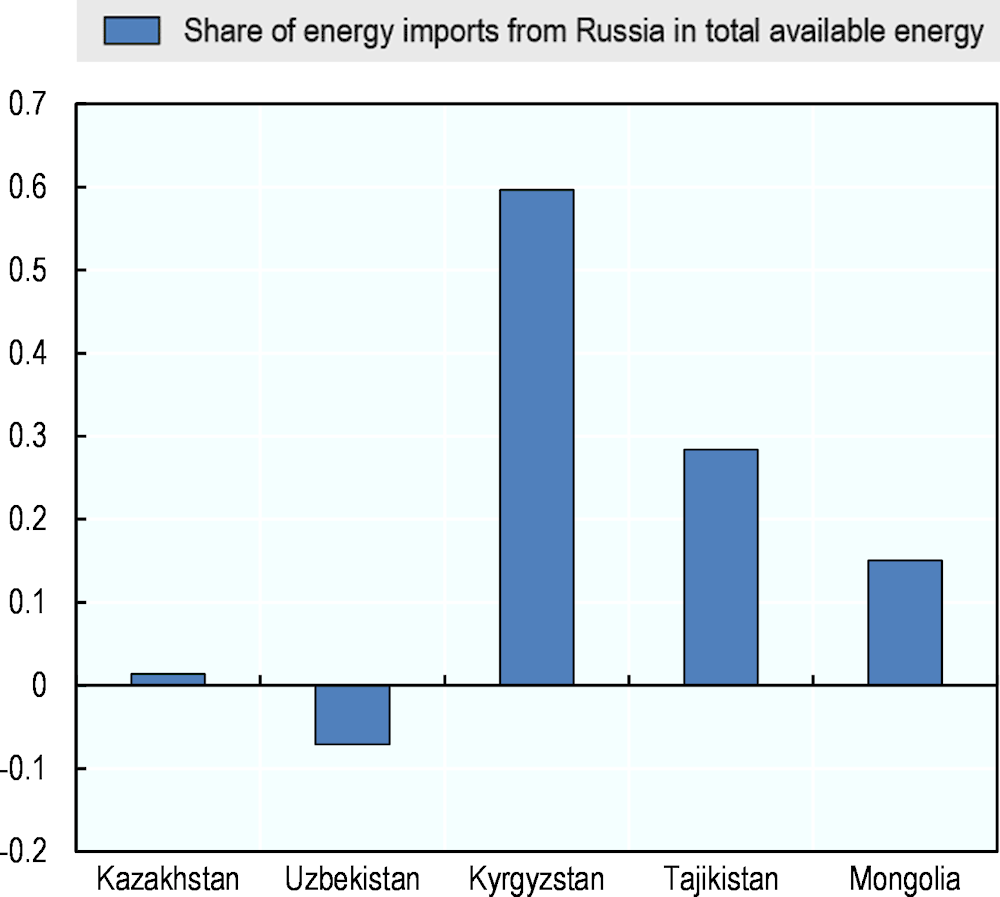

With the exception of Uzbekistan, Central Asian economies have become more dependent on wheat imports from Russia since 2020 (Figure 3). Tajikistan and Mongolia imported close to 100% of their wheat needs from Russia in 2020, while that figure reached close to 55% in the case of Kyrgyzstan in 2021. Energy dependence is also substantial for those three Central Asian economies: energy imports from Russia account for 60% of domestic utilisation in Kyrgyzstan, close to 30% in Tajikistan and 15% in Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan do not rely on Russian energy in 2022 (Figure 4)

Figure 3. Share of wheat imports from Russia and Kazakhstan in total domestic utilisation (%)

Note: No data available for Turkmenistan.

Source: OECD calculations based on (UNCTAD STAT, 2022[1]; FAO, 2022[3]).

Figure 4. Share of energy imports from Russia in total available energy in Central Asia

Note: No data available for Turkmenistan. Due to data limitations, gross available energy is calculated as primary production + imports – exports, without taking into account recovered and recycled products or stock variation.

Source: IEA (2022).

Financial sector

Financial systems in Central Asia have been relatively stable in recent years, but the region has a history of banking crises, most recently against the backdrop of global shocks in 2008-09 and 2014-15. The effects of COVID-19 have further exacerbated the existing vulnerabilities, as liquidity provision issues in 2020 were met with an easing of prudential regulation and non-performing loan ratios throughout the region went up (OECD, 2021[4]; IMF, 2022[5]). Overall, the weakness of banking sectors across much of the region has been a drag on the development of the private sector due to limited access to finance and an absence of deep, well-functioning capital markets.

However, Central Asia’s banking sector exposure to soft currencies represented less than 15% of claims and liabilities in 2021, which indicates that banks’ exposure to the ruble was most likely below this threshold before the war (BIS, 2022[6]). Nevertheless, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan had close banking ties with Russia, with all of their banks having Russian accounts among their top four correspondents1, compared to 50% of banks in Mongolia and Uzbekistan, while Tajik financial credit institutions held three-quarters of their correspondent accounts with Russian banks at the onset of the war (EBRD, 2022[7]).

Foreign Direct Investment

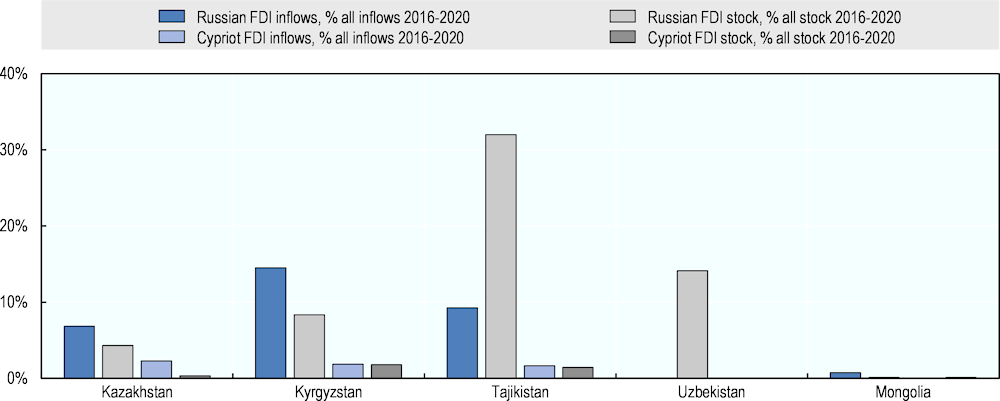

Although exact numbers may vary substantially between inward figures reported by the national statistical offices (NSOs) of Central Asian countries and outward data reported by the Central Bank of Russia (CBR)2, the stock of Russian FDI between 2016 and 2020 remained substantial in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, where it averaged 32% and 14.1% of the total FDI stocks respectively. However, Russia’s share of FDI stock might be overestimated in Uzbekistan, as data are lacking for some countries, including important players such as France and Japan. By contrast, actual stocks and inflows of Russian FDI might be slightly underestimated in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan where FDI from Cyprus, a well-known offshore location amount to almost 2% of total stocks and inflows (Bulatov, 2017[8]). Russian net FDI inflows to Kyrgyzstan have been the highest in the region over the period, representing about 15% of total inflows (Figure 5). In Kazakhstan, a relatively low base of Russian FDI stock suggests that while FDI inflows are rising, the importance of Russian investment remains limited, except for large-scale mining projects. Mongolia is scarcely exposed to Russian investment, as Russian FDI stock amounts to just 0.1% of all stock, and its share of net inflows was negative over the period, indicating that Russia has been disinvesting over recent years.

Figure 5. Share of Russian investment in total FDI stock and inflows to Central Asia, 2016-2020

Notes: (1) For comparability purposes, stock data refers to direct investment positions as reported by the receiving economy, taken from the IMF CDIS database, since inflow data is taken from the National Statistical Offices of the displayed countries. (2) Uzbekistan FDI stock data refers to outward data reported by the counterpart economy. Russian share in FDI stock for Uzbekistan may be overestimated as some countries (including Cyprus, France and Japan) kept FDI outflows to Uzbekistan confidential. (3) No available data for Turkmenistan nor for FDI inflows to Uzbekistan. (4) Tajikistan FDI inflow data is only available for 2017-2019.

Source: (IMF, 2022[9]).

People: labour migration and remittances

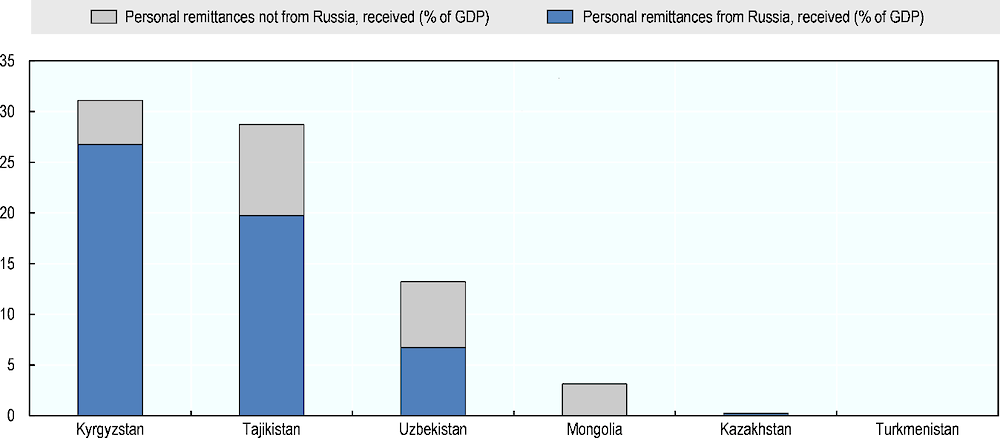

Remittances remain a major source of income and foreign currency earnings for Central Asian economies, representing 32.7% of GDP in Kyrgyzstan, 33.4% in Tajikistan, and 13.3% in Uzbekistan in 2021 (Figure 6) (KNOMAD, 2022[10]). The bulk of these remittances stems from Russia, reaching, for instance, 26.9% of GDP in Kyrgyzstan, 19.5% of GDP in Tajikistan, and 7.4% in Uzbekistan in 2021, accounting for more than 50 per cent of the total remittances received that year (KNOMAD, 2022[10]; World Bank, 2022[11]; Central Bank of Russia, 2022[12]).

Figure 6. Share of remittances from Russia to Central Asia as % of GDP in 2017-2021

Note: Share of remittances from Russia to Tajikistan is based on 2020 and 2021 data only.

The impact of international economic sanctions on the Russian economy has so far been less severe than initially anticipated

International sanctions led by the European Union and the United States aim at pressuring Russia to end the war

In response to Russia’s decision to recognise as independent the non-government controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the United States, the European Union, the G7 and other Western and non-Western partners imposed sanctions on Russia in an effort to thwart the latter’s ability to finance the war. Measures target both the internal real economy and external, macro-financial stability, and add to the more limited sanctions imposed in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Since February 2022, the EU has issued eight packages of sanctions or restrictive measures against Russia, some of which also target Belarus (European Commission, 2022[13]). Leading sanctions apply to the technology, financial and energy sectors and target a wide range of Russian entities and individuals such as state-owned media channels and agencies; high-ranking governmental officials, business people linked to the Russian regime, and other influential figures; government ministries, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and private banks. In addition, sanctions apply to financial assets held in Western jurisdictions; transactions involving the Russian Central Bank, the export of arms, oil and gas machinery, luxury goods, and advanced technology items; and various import restrictions (Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2022[14]). The latest sanctions package, in particular introduces a price cap on Russian oil imports, complementing the EU’s plan to stop importing Russian oil as of 2023 by banning European companies from transporting Russian crude above a certain price to third countries (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022[15]; European Council, 2022[16]).

The United States has also imposed wide ranging sanctions on Russia’s largest financial institutions, banks, state-owned enterprises, elites, and family members, as well as prohibiting new investments in the country. US sanctions include a prohibition on the import of Russian oil, natural gas, and coal into the US, sanctions on more than 400 individuals and entities, and various financial restrictions on Sberbank, VTB, and Alfa Bank; and a ban on the export of US dollar banknotes and many US technologies to Russia (The White House, 2022[17]).The United States also issued secondary sanctions guidance, signalling its readiness to apply sanctions to organisations outside Russia which would trade with or provide financial, technological, or material support for its military or its annexation of Ukrainian sovereign territory (US Department of the Treasury, 2022[18]).

The co-ordinated and relatively swift adoption of comprehensive sanctions against Russia’s financial system rendered Russian assets toxic for many foreign investors, triggering an asset sell-off that led to capital flight, an initial ruble depreciation by close to 60%, excess deposit outflows from the country, and stock market plunge (Interfax, 2022[19]; Central Bank of Russia, 2022[20]; Central Bank of Russia, 2022[21]). While European sanctions are particularly affecting the supply of consumer goods, as the EU is Russia’s largest trading partner in goods (European Commission, 2022[13]), the complexity of navigating sanctions and negative perceptions of operating in Russia have led more than 1000 international firms to curtail operations on the Russian market since the beginning of the war, particularly in aviation, finance, software, and agriculture. This has added to supply-chain disruptions, while Russian traders have been facing barriers to continued operations, and will have to find substitutes for imports (IMF, 2022[22]). In turn these disruptions have led to delayed deliveries, shortages of goods, and higher prices, resulting in a supply-side crunch (Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2022[14]).

The Russian economy is contracting, yet is proving more resilient than initially expected

Russia’s economy was expected to contract sharply in 2022, with IMF April 2022 estimates predicting a “large contraction” of 8.5% in 2022 due to the impact of the sanctions on international trade, disrupted financial systems and a loss of confidence (IMF, 2022[22]; OECD, 2022[23]; Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, 2022[14]). However, the latest projections upgraded the forecast for Russia’s economic decline in 2022 by 5.1 percentage points to envisage a 3.4% decline (IMF, 2022[24]). The economy is proving more resilient so far than planned, due to i) soaring commodity prices: the energy market has indeed priced in the decrease in oil supply following the embargo announcement, although Europe has continued to buy oil, while Russia also found alternative buyers in China and India, which boosted fiscal revenue and offset European losses (Meduza, 2022[25]); ii) targeted monetary policy interventions from the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) preventing capital flight from banks, a wave of bankruptcies, and high inflation through a sharp increase in the key rate, iii) and a resilient labour market (IMF, 2022[24]).

However, several factors indicate a potentially more severe, longer-term decline. First among them is the shortage of technological inputs. An increasingly closed economy, subject to technological and other specialised import bans that are needed by Russian industry is likely to significantly alter technological advances, industrial production and long-term growth. The Russian automotive and aviation sectors have already shown signs of subsidence, with reports of Russian airlines having to strip airplanes to use spare parts they can no longer purchase abroad (Reuters, 2022[26]), and car production registering an 80% decrease year-on-year in August 2022 (EIU, 2022[27]).

EU sanctions targeting Russian oil coming into effect in 2023 as well as the gas supply cuts are expected to curb Russia’s energy revenue. Whilst the oil price cap is unlikely to lead to a collapse of Russia’s oil production and exports, it will deprive it of a significant source of revenue – the EU accounted for roughly 50% of oil sales before the war – and increase the risk for tier countries to trade with the former. The Russian government already expects export earnings to fall by almost 10% in 2023. As for gas, significant infrastructure investments will be needed to increase supplies to the East, as current infrastructure does not allow to redirect falling volumes from the European market to Asia (Energy Monitor, 2022[28]).

Last but not least, the transition to a war economy and the partial mobilisation announced on September 21st are expected to have a structural impact on GDP growth: a reduction of the available labour force, lower household spending, a drop in revenue collection, and significant human capital flight of highly-skilled workers from Russia are all likely to have a negative impact on growth (Meduza, 2022[25]). More than 250,000 people have reportedly fled the country since the mobilisation announcement (Novaya Gazeta Europe, 2022[29]); adding to the hundreds of thousands who already left following the beginning of hostilities in February (BBC, 2022[30]). The departure of young entrepreneurial talent in academic, finance, and tech and the reduction of the labour force will negatively impact the country’s capacity to innovate, demographic trends and ultimately the economy’s long-term trajectory.

Table 1. Overview of the main types of sanctions imposed on Russia as of October 2022

|

TARGETED INSTITUTIONS, SECTORS, AND PERSONS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Technology sector |

Trade and energy sector |

Central Bank |

Financial institutions |

SOEs |

Oligarchs |

|

|

TYPES OF SANCTIONS |

Export ban in the defence, aerospace, marine, oil refining, aviation, transportation equipment, luxury and electronics sectors Export controls on dual-use technologies (microchips, semiconductors, servers) products using Western-made or designed chips |

Import ban on crude oil and refined petroleum products (with limited exceptions), coal and other solid fossil fuels, gold, steel, iron, wood, cement and certain fertilisers, seafood, liquor Price cap on Russian oil Ban on EU companies to provide shipping insurance, brokering services, or financing for oil exports from Russia to third countries Freeze of the Nordstream 2 gas pipeline project |

No access to assets held at private institutions and central banks in the EU and US Ban on banks providing loans, services, or assistance to the government and CBR Ban of all transactions (asset transfers, foreign exchange transactions, etc.) with the CBR |

Asset freeze and prohibition to make funds and economic resources available to entities and individuals on the sanctions list Decoupling of certain Russian banks from the SWIFT system (including Sberbank, Russia's largest bank) Prohibition of investments in projects of the Russian sovereign wealth fund (Russian Direct Investment Fund) |

Prohibition of all transactions with certain Russian SOEs Prohibition of the listing and provision of services on trading venues Prohibition of new debt and equity provision |

Asset freeze and prohibition to make funds and economic resources available to listed individuals Prohibition for banks to accept deposits exceeding €100,000 Travel bans and visa restrictions Seizure of luxury goods, property and asset management and service companies |

|

EXPECTED IMPACT ON THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY |

Limited equipment and technology procurement for the defence sector that can double for civilian use, impacting war industry and high-tech sectors Atrophied industrial development |

Cut in Russia’s oil revenue Containment of possible Russian oil price spike |

Complication of international payments Ruble exchange rate volatility, increased inflation and reduced purchasing power Increased government borrowing costs No access to foreign assets stored in other central banks and private institutions |

Complication of international payments Reduction of investments and economic activity Exclusion of Russia from global markets |

Reduced revenue and tax sources Reduction of investments and economic activity Exclusion of Russia from global supply chains |

Increase in the political cost of support to the Russian government More difficulty in attempts to evade sanctions |

Source: (De Nederlandsche Bank, 2022[31]) (Central Bank of Ireland, 2022[32]) (European Commission, 2022[33]) (NPR, 2022[34]) (US Department of the Treasury, 2022[35]) (EUR-Lex, 2022[36]) (European Commission, 2022[37]) (Interfax, 2022[38]) (Office of Foreign Assets Control, 2022[39]) (European Council on Foreign Relations, 2022[40]).

Notes

← 1. A correspondent bank defines a financial institution providing and facilitating services to another financial institution, often in another country. Corresponding banks are mainly used by domestic banks to service transactions from or completed in foreign countries, allowing domestic banks to access foreign financial markets without having to open branches abroad.

← 2. Differences in reported figures between both sources can be substantial in some cases. For instance, Kyrgyzstan reports Russian FDI inflows amounting to almost 15% of total FDI inflows to the country, while the CBR reports inflows amounting to 55%. Except for that extreme case, differences between both datasets still reflect the same dynamics over the period we consider here (2016-2020). For data availability and comparability purposes, we chose to use FDI stock and inflow data as reported by NSOs.