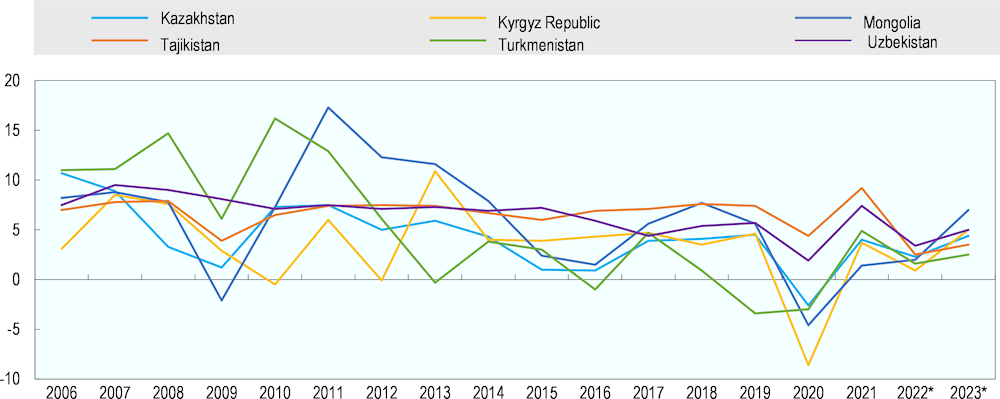

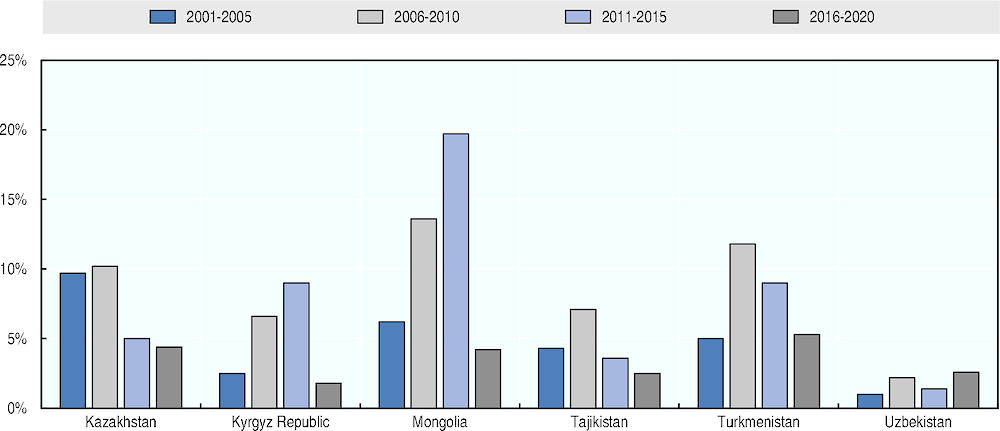

Given Central Asia’s close economic relations with Russia and anticipations for a strong and immediate contraction of the latter’s economy, many observers expected the cascading effects of international sanctions against Russia to derail the post-pandemic recovery trend that had emerged in 2021 in Central Asia (Figure 7) (OECD, 2021[4]).

Weathering Economic Storms in Central Asia

Economies of Central Asia seem to have withstood the shock created by the sanctions

GDP continued to grow across Central Asia in the first half of the year

Figure 7. Real GDP growth in Central Asia (%)

Compared to projections from autumn 2021, growth was forecasted to more than halve in 2022, except for Mongolia, and Turkmenistan (Table 1). The largest drop was anticipated in the region’s most vulnerable and non-commodity exporting countries, especially Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, where the effects of the war in Ukraine were expected to exacerbate high debt distress risks (OECD, 2021[4]; IMF, 2022[22]).

Table 2. The 2021 post-pandemic recovery trend in Central Asia is likely to slow down

The deviation from the original forecasts underscores the depth of the estimated economic shock across the region

|

GDP growth 2021 |

GDP growth forecast 2022 |

GDP growth forecast 2023 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Estimates as of October 2021 |

Estimates as of April 2022 |

Estimates as of October 2022 |

Estimates as of April 2022 |

Estimates as of October 2022 |

||

|

Kazakhstan |

4.0 |

3.9 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

3.7 |

5.6 |

0.9 |

3.8 |

5.0 |

3.2 |

|

Mongolia |

1.4 |

NA |

2.0 |

2.5 |

7.0 |

5.0 |

|

Tajikistan |

9.2 |

4.5 |

2.5 |

5.5 |

3.5 |

4.0 |

|

Turkmenistan |

4.9 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.2 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

|

Uzbekistan |

7.4 |

5.4 |

3.4 |

5.2 |

5.0 |

4.7 |

Source: (IMF, 2021[41]; IMF, 2022[22]; IMF, 2022[24]).

Fears that the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine might derail the post-COVID recovery have not yet materialised. On the contrary, growth number projections have been revised upwards since for the economies of the region (Table 1). Revisions have been highest for Tajikistan (+3pp), Kyrgyzstan (+2.9pp) and Uzbekistan (+1.8pp), and more moderate for Mongolia (+0.5pp) and Kazakhstan (+0.2pp). Only Turkmenistan saw a downward revision for both 2022 and 2023 forecast. Growth in the first half of the year was supported by an important boost to consumption driven by public sector wage hikes, high remittance flows to Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, a sharp increase in trade flows, suggesting possible shadow trade with Russia, and important gains for commodity exporters Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan (EBRD).

However, downward revision for 2023 growth numbers, even if they remain strong in global comparison, remind of the fragility of post-COVID-19 recovery consolidation across the region. If the Russian economy is set to further contract, it is not to be excluded that the impact on economies of Central Asia might be negative and of a stronger magnitude. Unprecedented levels of political and economic uncertainty make growth patterns and predictions more fragile than ever, pointing to the need for Central Asia to address long-term structural needs and diversify its foreign trade and investment relationships to secure a strong and sustained growth trajectory.

Table 3. Overview of the expected and actual transmission channels to the economies of Central Asia

|

|

Initial expectations Spring 2022 |

Observed impact September 2022 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

TRANSMISSION CHANNELS |

MACROECOOMIC |

Drop in growth rates across the region Significant price increases, especially of basic food products

Higher energy costs for Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia and Tajikistan due to high dependence on energy imports from Russia |

Strong upward revisions for 2022 growth rates

Record-high price increases for food and energy products High revenue gains for commodity exporters, esp. Kazakhstan |

|

LABOUR |

Strong fall in labour remittances across Central Asia, especially for Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan Increased strain on the lower-skilled segments of labour markets due to returning migrants Relocation of labour from Russia and Belarus, especially in the IT sector |

Record high remittance inflows to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan

No surge in the levels of returning migrants Relocation of highly skilled Russian speaking workers and businesses to IT-parks and special economic zones across the region |

|

|

FINANCIAL SECTOR |

Operational difficulties for Russian owned banks, or affiliates of Russian banks Potential disruptions in the banking sector as many banks have strong correspondent account ties with Russia

Destabilisation of payment systems in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan if Mir system to be sanctioned by the US Strong depreciation and volatility of national currencies in tandem with the ruble |

No observed disruptions to the banking sectors across the region

Shift to payments in national currencies by businesses Stabilisation of exchange rates

|

|

|

TRADE AND ENERGY |

Higher revenues from energy and mineral commodities as commodity prices surge, especially for Kazakhstan (oil), Mongolia (mineral commodities) and Uzbekistan (gold) Lower export revenues for Central Asia following Russia’s economic contraction Supply-chain disruptions as Central Asia relies largely on Russia for sourcing of inputs Reduced grain imports, due to Russia’s export restrictions

|

Strong increase in commodity exports

Increase in “shadow” trade with Russia, especially in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan where re-exports of (mostly) Chinese goods to Russia seems to have become a major business activity Higher costs for businesses due to disruptions in sourcing inputs from Russia impacting profitability and access to credit |

|

|

INVESTMENT |

Falling investments due to reduced Russian investments and higher uncertainty (risk sentiment) Risk of exposure to secondary sanctions |

No trend observed so far China is pursuing investment projects in the region Increased FDI inflows to Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia, following the settlement of long-standing disputes over mining projects (Kumtor mine in Kyrgyzstan and Oyu Tolgoi mine in Mongolia) |

Source: OECD analysis (2022).

The main engines of growth have not yet been negatively affected

Remittances have continued to support consumption across the region

Migrant remittances represent a significant source of revenue for households, and indirectly governments, across Central Asia and are primarily used for immediate consumption by the poorest among the latter. At the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine, initial expectations pointed towards a sharp reduction of remittance flows in 2022 in terms of both value and volume. For instance, in Kyrgyzstan remittances were projected to drop by 33%, and by 22% in Tajikistan. Such expectations were widespread among migrant workers themselves, with surveys indicating that about 40% of labour migrants from Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan in Russia planned on returning home in Spring 2022. Financial difficulties, encompassing both loss of employment and initial fears of a lasting devaluation of the ruble against the dollar were cited among the main reasons for this decision (State Migration Agency of Uzbekistan, 2022[42]; Insan-Leilek Foundation, 2022[43]). This echoes what occurred in the mid-2010s, when remittances to the region dropped by 40% as Russia was hit by a combination of sanctions following the illegal annexation of Crimea and the end of the commodity-price “super-cycle” (KNOMAD, 2022[10]; World Bank, 2022[44]).

Contrary to expectations, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan experienced an increase in remittances in the half of 2022, providing a substantial contribution to consumption and growth figures (EBRD, 2022[45]). The most drastic increase was in Uzbekistan, where remittances are estimated to have increased by 96% year-on-year (yoy). The increase has been more modest in Kyrgyzstan (+11%) but is relatively more important to its economy given the higher share of remittances in GDP. However, reasons for this increase remain unclear. Even if demand for migrants workers, mainly employed in the construction sector, was on the rise in Russia, this is unlikely to account for the total of additional remittances. Moreover, newspapers and observers across Central Asia report a fall in employment and incomes of migrant workers in Russia. For instance, in the first quarter of 2022, 60,000 Tajik and 133,000 Uzbek migrants returned from Russia to their home countries (IOM, 2022[46]). Frontloading of savings transfers back home from some migrant workers worried by their future prospects, as well as the inability to statistically distinguish labour remittance transfers from other monetary transfers from Russia, to circumvent restriction of foreign currency purchases, might also contribute to explain these numbers. Especially for Kyrgyzstan in the first case, and Uzbekistan in the second. On the contrary, in Tajikistan, remittances seem to have decreased by 10% up to May 2022, in line with reports of job losses among Tajik migrants in Russia. However the rapid rebound of the Russian ruble and the Tajik somoni vis-à-vis the US dollar mitigated the remittance decline (ADB, 2022[47]), while Tajik migrants are also increasingly turning to Kazakhstan as a safer work destination (Radio Ozodi, 2022[48]).

The increase in energy prices has benefitted commodity exporters in the region

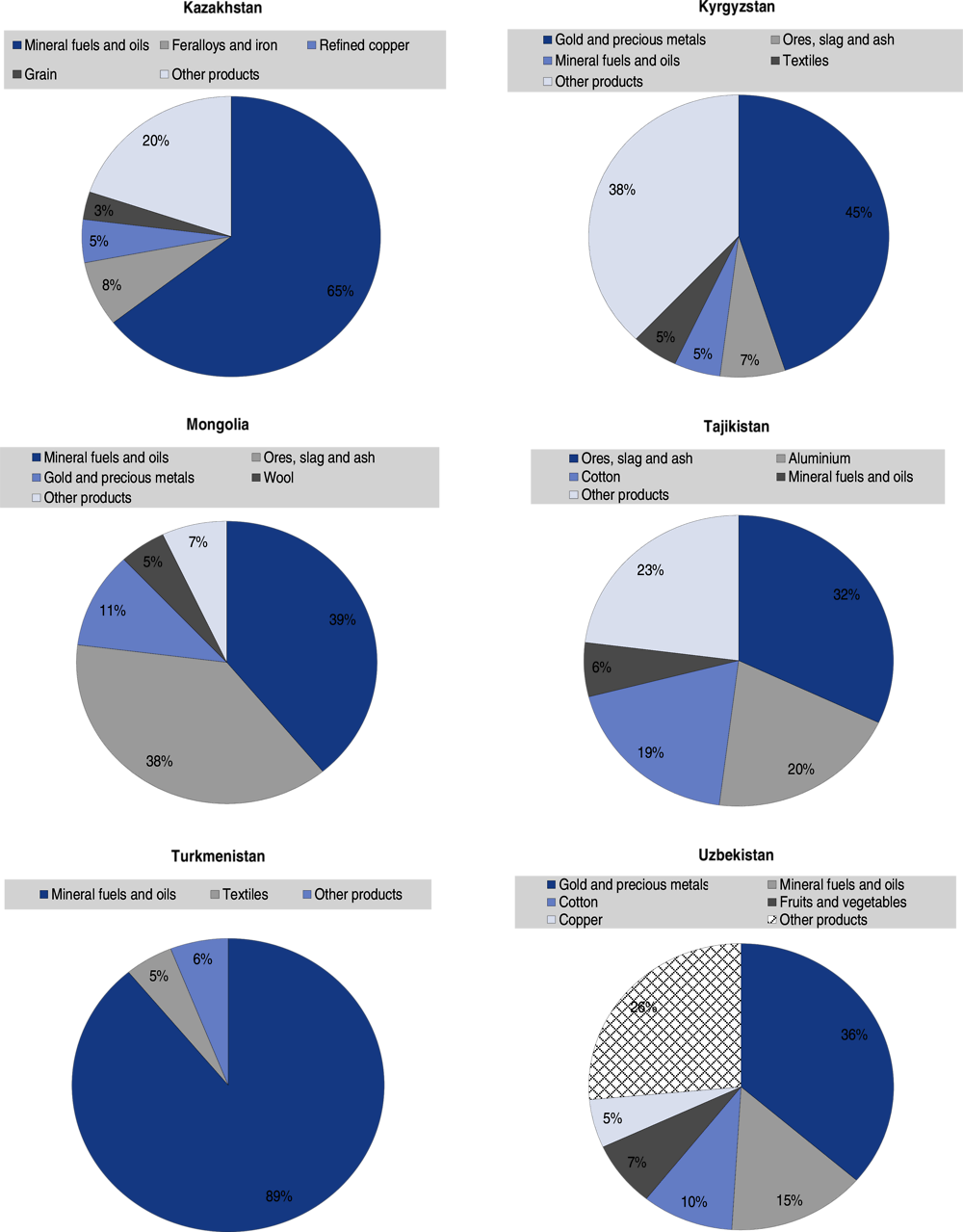

Central Asian economies remain highly concentrated, as protracted and stalled reforms have failed to expand export profiles and diversify production, with most countries relying heavily on the export of raw extractive goods (Figure 8). Commodity exports, such as energy and metals, represent on average more than 60% of total exports across the region, reaching 80% in Mongolia and Kazakhstan (UNCTAD STAT, 2022[1]). More broadly, exports constitute over a third of GDP across the region, and within each country’s export basket the top three products account for over two-thirds of all exports (OECD, 2021[4]). In addition, with the exception of Kazakhstan, the countries of the region export to a very narrow range of markets in which Russia holds a significant place. Such lack of diversification leaves the region highly vulnerable to external shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and large price fluctuations in commodities.

Figure 8. Export decomposition, average 2016-2020

The drastic increase in global commodity prices observed over the past months, in particular for energy and metals, has so far had an overall positive impact on Central Asian economies. The impact has been particularly pronounced for large commodity exporters such as Kazakhstan. The first half of the year saw an 85% yoy increase in the value of oil exports, and a 10% yoy increase in volumes as purchase volumes of China, South Korea and Singapore increased. Kazakhstan therefore is expected to benefit from a strong economic and fiscal performance, with a current account surplus of about 3 % of GDP in 2022, and an annual increase of government revenues by 3.4 pp to 20.5% of GDP, of which 6.6 pp is attributable to oil revenues only (IMF, 2022[49]). However, a durable interruption of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium pipeline could reduce the country’s oil exports, while a worsening of adverse global conditions could lower oil prices and raise borrowing costs.

A similar trend can be observed in Uzbekistan, where the value of exports has almost tripled since February 2022, with the highest increase seen in the value of energy and chemical exports, which were multiplied by, respectively, 13 and 7.5 times, while the value of metal exports has risen fivefold. Combined, these three commodity groups represent about a third of the country’s exports, and might result in a large increase in trade revenues. Finally, gold, the country’s largest single export good, saw a more modest, albeit important, increase in value (+26%), mainly attributable to an increase in the volume of exports given that gold prices have been declining since the beginning of 2022 (State Committee on Statistics, 2022[50]).

The situation of the remaining economies of the region is more diverse. In Mongolia, for instance, the volume of coal exports declined in 2021 and until February 2022 due to trade restrictions with China, while increased prices compensated for that decline. Since February, the volume of coal exports seems to have caught up with the increase in prices, as both have been multiplied by 14. Copper exports seem to follow a similar dynamic (National Statistics Office of Mongolia, 2022[51]). Finally, the effect of commodity prices has been the lowest for Kyrgyzstan, as its export structure is more diversified and less reliant on energy, while gold exports even decreased in Tajikistan in the first half of the year (Tajstat, 2022[52]; National Bank of Kyrgyzstan, n.d.[53]).

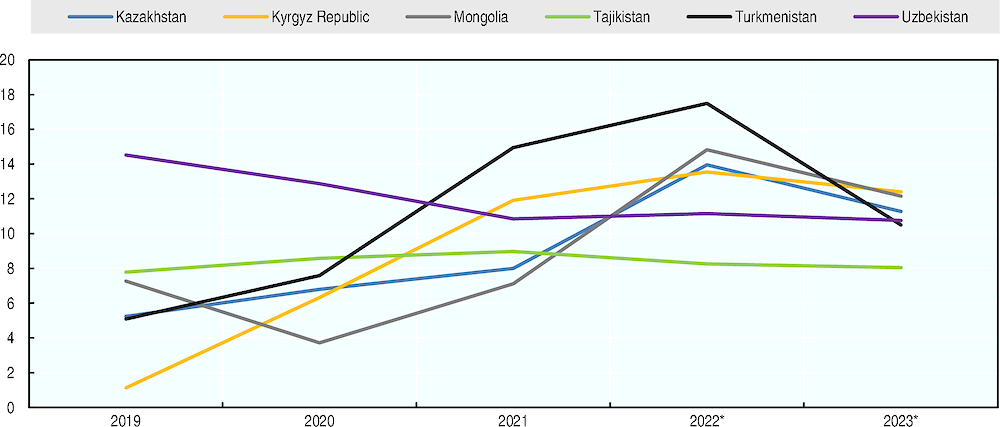

Rising inflation is weighing negatively on firms and households

High levels of inflation are so far the most immediate and important effect of Russia’s war in Ukraine on Central Asian economies (Figure 9). In August 2022, consumer price inflation reached 16.1%, and in July 15.7% in Mongolia (after a peak at 16.1% in June), 14% in Kyrgyzstan, and 12.3% in Uzbekistan (EBRD, 2022[45]). Indeed, the global rise in cereal prices and fertiliser costs translated into higher prices of both imported and domestically produced food, while supply chain disruptions also drove up firms’ production costs. The most recent World Bank Business Pulse Survey indicates indeed that 87% of firms in Kyrgyzstan, 56% in Uzbekistan and 53% in Tajikistan have increased their production costs since February 2022, as they source many inputs from Russia (World Bank, 2022[54]). Energy is another important expenditure item for households and businesses alike, given that Russian energy imports accounted for 60% of total energy utilisation in Kyrgyzstan, a bit less than 30% in Tajikistan and 15% in Mongolia in 2019 (Figure 4).

Figure 9. Average consumer prices in Central Asia, October 2022 estimates (%)

According to national statistical offices, food inflation has soared across the region, reaching 22.2% in Kazakhstan (August) and 9.7% in Tajikistan (July), where food represents more than 50% of household expenditures, 21.5% in Mongolia (July), and 16.5% in Uzbekistan (June). For the latter two, food represents 26% and 40%, respectively, of the consumption basket of households (Tajstat, 2022[55]; National Statistics Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic, 2022[56]; Bureau of National Statistics, 2022[57]; State Committee on Statistics, 2022[58]; National Statistics Office of Mongolia, 2022[59]; EBRD, 2022[45]). Even if inflation is expected to slow down in 2023, this outlook is subject to several negative risks, rising food and energy prices therefore add to food insecurity risks already raised by the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2021[4]; OECD, 2021[60]; World Bank, 2022[44]). The situation might become most acute for the poorest households, for whom food and energy account for the largest share of the consumption basket. In Tajikistan for instance, these risks were already on the rise in 2021, with 33% of households reporting reduced food consumption in the first half of 2021, representing a 5% increase compared to the year before (World Bank, 2021[61]). This followed mainly from a strong increase in inflation (+9.2%) in the first half of 2021 and a decline in household wages.

The trade channel has remained robust across Central Asia, but the region’s close ties with Russia leave it vulnerable to political and supply risks

Trade has remained dynamic in Central Asia, but suspicions of shadow trade with Russia might expose the region’s economies to secondary sanctions

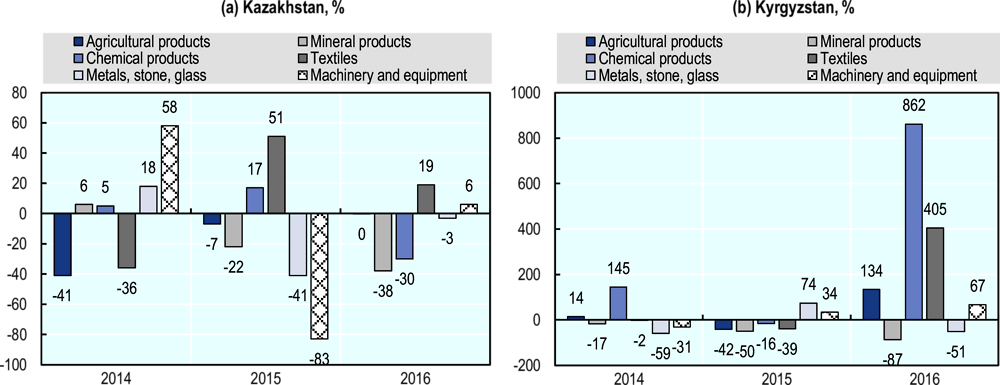

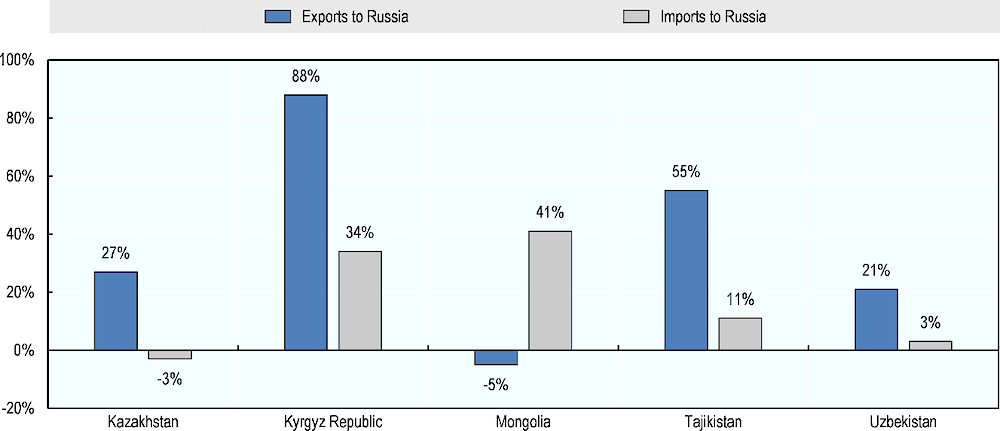

Given the region’s composition of trade with Russia (Figure 2), a decline in Russian demand for mineral commodities and chemical imports was expected when the war began, in line with the projected contraction in Russia’s infrastructure, construction and industrial sectors (Pestova, 2022[62]; IMF, 2022[5]). However, since food and manufacturing products also account for a non-negligible share of exports to Russia, Central Asian products were seen as potential cheap substitute for some European exports.

Figure 10. Annual change in trade flows with Russia in the first half of 2022 (%, yoy change)

Note: Data for Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan covers January-June, while covering also July for Kyrgyzstan, and August for Mongolia. No data is available for Turkmenistan.

National data for the first half of 2022 show a strong increase in exports to Russia for all countries of the region except Mongolia (Figure 10), whereas on the import side, increases mainly reflect the rise in energy and cereal prices. Interestingly enough, the overall export dynamic does not seem to follow the one observed after a first wave of sanctions against Russia following the annexation of Crimea in 2014 (Figure 11). Given the large difference in magnitude between both sanction regimes, this could indicate that Central Asia might currently be seen as a short-term alternative supplier of critical goods to the Russian economy.

Figure 11. Evolution of commodity exports to Russia following the first wave of international sanctions in 2014 (%, 2014-2016)

Kazakh exports to Russia have been on the rise, mainly due to the global increase in commodity prices. In the first half of 2022 alone, crude oil exports rose by 85% in value, with 89% of this increase attributable to higher prices rather than increased volumes (National Bank of Kazakhstan, 2022[63]). On the contrary, a reduction in Russian demand for mineral and energy exports is noticeable, especially for iron ores, gold, silver and rolled ferrous metals. Beyond Russia, Kazakhstan also benefits from increased oil exports to European countries (EBRD, 2022[45]). The picture is more mixed for Uzbekistan, as the value of the country’s monthly global exports decreased by 47% since February 2022, and by 10% yoy, while bilateral trade with Russia has remained strong. Monthly exports to Russia rose by 78% between February and July, representing a 21% yoy increase in the first half of 2022 (State Committee on Statistics, 2022[50]). Finally, record increases in Kyrgyz and Tajik exports to Russia seems to be indicative of shadow trade patterns (EBRD, 2022[45]). In Kyrgyzstan indeed, increased bilateral trade with Russia coincides with falling exports to the rest of the world. Exports to Russia have mainly consisted of industrial goods and production inputs, while the value of imports of interim goods, mainly from China, increased by 65% between the first and the second quarter of 2022, and by 69% yoy (National Bank of Kyrgyzstan, n.d.[53]).

However, supply-chain disruptions are affecting some industries and likely to increase the costs of trade

Central Asia’s reliance on a small portfolio of trading partners and goods leaves the region highly vulnerable to external shocks, since the impact of any decrease in demand for key export or import products is magnified by a small range of trading partners and a lack of alternative sourcing opportunities. Trade disruptions at the Russian and Chinese borders in early 2020 were a reminder of this vulnerability, amplifying shortages of food and basic necessities during the first months of the pandemic (OECD, 2021[4]). Since the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine, disruptions of supply chains stemming from or integrating both countries have led to shortages of inputs for Central Asian businesses. Overall, 43% of firms participating in the World Bank Business Pulse Survey indicated that imports from Russia or Ukraine have decreased or that they stopped sourcing from these countries altogether. It is also interesting to note that firms that used to sell to exporters or multinationals from Russia or Ukraine experience, an average decline in sales between 5 and 13%, while firms not selling to these countries have seen their sales increase by 5% on average (World Bank, 2022[54]).

Russia, and to a lesser extent Ukraine, remain a major source of essential inputs for Central Asian economies, which remain concentrated in the lower stages of value chains (World Bank, 2020[64]). The former provides about a third of the region’s mineral product imports, 13% of base metals and about 10% of chemicals, electric machinery and food (Figure 2). It also represented in 2018 the first foreign input provider to Kazakhstan, with its contribution concentrated in inputs to mining (both energy and non-energy) products and basic metals exports (WTO, 2020[65]). While Central Asia could benefit from some trade diversion at the global level, estimates suggest that in the short-term increased export demand would not compensate for the loss of trade opportunities with Russia (Korn, 2022[66]).

Beyond the direct impact on imports from Russia, the cost of trade for Central Asian economies is likely to further increase, which might further increase consumer goods prices, due to the disruption of transit routes via Russia. The latter remained a major transit nation for many goods entering and leaving the economies of Central Asia. While recent research suggests that global supply chains, especially for agricultural goods and the mining sector, adapt quickly to economic disruptions brought by conflict (Korn, 2022[66]), it might prove more difficult for Central Asia, due to both a persistent connectivity gap and the structure of Central Asian economies. The evidence suggests that manufacturing supply chains adapt more slowly, which could exacerbate the effect of supply-chain disruptions reliant on these products from Russia. In addition, since the region’s isolation from global trade routes stems mainly from inadequate transport networks, lack of affordable transport services for containers, and missing links along major infrastructure corridors, developing alternative transit routes is likely to take time (OECD and ITF, 2019[67]).

Greater uncertainty might reduce Central Asia’s investment attractiveness

Alongside public finances and firms’ own funds, FDI remains a primary source of capital formation across the region, and Russia remains an important investor in the region contributing to know-how and the building of critical infrastructure, particularly in the mining and energy sectors, where most of the region’s FDI remains concentrated. Russian FDI and portfolio investments has been growing especially in Kazakhstan in recent years, even if it represents a comparatively lower share of total investments in the country (Figure 12). Recent investment projects, amounting to several billions of dollars, include the development of Kazakhstan’s Kalamkas-Sea and Khazar offshore oil fields with Russia’s Lukoil, while Uzbekistan has been discussing plans for the construction of a nuclear power plant by Rosatom (Eurasianet, 2022[68]; Lukoil, 2021[69]). These investment projects are likely to be delayed, while smaller projects might be scaled-back or even cancelled (EBRD, 2022[7]; World Bank, 2022[44]).

Figure 12. Net FDI inflows as a share of GDP in Central Asia (5-year average)

Preliminary data for the first half of 2022 suggest a scaling back of Russian investments. In Kazakhstan for instance, as the country registered outflows of Russian FDI in the second quarter of 2022, for the first time since the height of the pandemic in 2020 (National Bank of Kazakhstan, 202[71]). If this trend were to persist or strengthen, it would further compound a general downward trend in both FDI inflows and greenfield investment since the end of the commodity “super-cycle” in 2014-15. The dynamic of this decline largely reflects Central Asia’s fragile investment environment, long-standing issues in the region’s banking sectors, and the over-representation of extractive sectors in total FDI inflows and capital formation (OECD, 2021[4]). The COVID-19 pandemic led to an 18% decline in FDI inflows to Central Asia in 2020, which was nevertheless a smaller decline than in most other regions of the world, thanks mainly to a 35% increase in net FDI inflows to Kazakhstan related to the Tengiz hydrocarbon project. Nonetheless, the pandemic has highlighted the challenges Central Asian economies face in attracting new and more sustainable investment into those sectors of the economy that are more likely to contribute to job creation and diversification. The most marked declines in FDI inflows and greenfield investments were concentrated in the traditional recipient sectors for FDI, such as petroleum extraction, oil refining, and production of coke and chemicals, without seeing a redirection to sectors such as pharmaceuticals or technology offering opportunities for diversification (UNCTAD, 2021[72]).

Looking forward, the exceptionally high level of economic uncertainty, including major downside risks in the case of an intensification of the war, might lead to a global fragmentation of investment and add to a further decline of investment inflows to Central Asia. The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic gave a first insight into such a possible scenario: while the world’s most advanced economies saw a rise in investments as early as 2021, inflows to Central Asia were projected to begin rising only in 2022. Remaining issues in the region’s business climate might explain the lag, reducing the region’s attractiveness for investors amid heightened global competition for FDI (OECD, 2021[4]).

Box 1. Central Asia’s banks have coped well with Russia’s financial sector disruptions

Early expectations anticipated significant disruptions to the functioning of Central Asia’s banking system following the exclusion of major Russian banks from the SWIFT international payment system, and the large correspondent relationships between Central Asian and Russian banks. In Spring, subsidiaries of Russian banks in Central Asia fell under international sanctions, such as Kazakh branches of VTB Bank, Sberbank, Alfabank which were either sold to local competitors or decided to pursue operations in national currency. In addition, sanctioned Russian oligarch Usmanov had to sell his stake in Uzbek privately-owned Kapitalbank to prevent the bank from falling under sanctions, and the sale of UzAgroExportBank to a Russian bank was cancelled.

Limited banking exposure to the Russian ruble may have explained Central Asia’s financial sector resilience following the exclusion of ten Russian banks from the SWIFT international payment system. Whilst the ban initially affected cross-border money transfers and increased the cost of remittances, Central Asian banks rapidly switched to payments in national currencies and reinforced compliance measures not to fall under secondary sanctions: amongst other measures, several financial institutions across the region restricted or banned altogether the use of Russia’s Mir payment card, as the United States stated that non-US financial entities entering into or expanding relations with the Russian operator could be deemed to be supporting Russia’s efforts to evade sanctions. Banks also benefitted from significant currency savings transfers and demand for international payment cards from Russian citizens relocating to Central Asia, which boosted margins and profitability

An influx of highly skilled workers might support raising the human capital profile of selected labour markets across the region

Persistently high levels of economic informality and labour migration, predominantly to Russia and Kazakhstan, remain a defining feature of Central Asia’s economies, particularly Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. This follows mainly from a lack of quality jobs and labour-market pressures generated by rapidly expanding labour forces. In Uzbekistan, for instance, about half a million new labour market entrants are predicted annually for the next decade (ADB, 2020[79]). Labour migration, seasonal or more permanent, therefore represents an opportunity for countries that are struggling to create enough jobs to reduce unemployment and ease strain on public services. In 2021, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan sent an estimated 7.8 million workers to Russia (Hashimova, 2022[80]). A large number of Central Asian labour migrants in Russia are employed in low-skilled sectors, such as construction, delivery services, and taxi driving, leaving them vulnerable to economic contractions (OECD, 2021[4]). Following the withdrawal of many Western businesses from Russia and the reduction in activity in certain sectors of the Russian economy in the first quarter of the year, Tajikistan reported about 60 000 returning migrants, 2.6 times as many as in the corresponding period of 2021, while Uzbekistan reported 133 000 retuning migrants over the same period (Asia-Plus, 2022[81]; IOM, 2022[46]).

Beyond these initial numbers, the evolution of the situation is hard to predict. The number of returning migrants seems not to have increased drastically until the third quarter of 2022, while some sources report increased Russian demand for Central Asian workers. The latter are also increasingly targeted to join the Russian military forces, in exchange of a fast-track citizenship process (Carnegie, 2022[82]). If Russia were to enter a protracted slowdown, migrant returns to Central Asia could increase further, heightening competition among the lowest-skilled segments of the labour market.

In parallel, since the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine, with an apparent acceleration since the announcement by the Russian government of a partial mobilisation in September 2022, Central Asian countries have witnessed an influx of Russians, and, to a lesser extent, Belarusians and Ukrainians. Actual numbers are difficult to estimate for each country, as Kazakhstan registers the most arrivals but acts also as a transit country, and some countries, such as Kyrgyzstan, offer visa-free regimes to Russian citizens. However, official numbers from Rosstat have indicated a net outflow of about 420 000 people from Russia in the first three quarters of the year, a doubling compared to the same period last year. Among these, about 80 000 have left for Ukraine, 58 000 for Tajikistan, 49 000 for Armenia, 44 000 for Kyrgyzstan, 41 000 for Kazakhstan and 39 000 for Uzbekistan. In comparison to the numbers communicated by the national press agencies of Central Asia, these numbers appear low, and they may constitute a sort of lower-bound estimate.

Among these new arrivals, many are highly skilled workers, mainly active in knowledge-intensive sectors as entrepreneurs or developers, supporting the knowledge industry, in particular in the IT sector, without putting additional pressure on local job markets. However, this massive influx is shifting the social equilibrium across Central Asia, contributing in particular to soaring housing and food prices in capital cities, raising fears of social tension (CABAR, 2022[83]). So far however, governments across the region have encouraged the relocation of businesses and highly-skilled workers. Uzbekistan for instance has created a three-year visa targeted at IT specialists, entrepreneurs and their families, in addition to the provision of free legal and administrative support services during their business journey (Government of Uzbekistan, 2022[84]). Kazakhstan is developing a number of measures to support and give preferences to foreign investors, and a newly signed presidential decree in Kyrgyzstan allows entrepreneurs from Russia to become residents of the creative industries park and conduct business in the country with a simplified tax regime (Government of Kyrgyzstan, 2022[85]). Looking forward, it will be important for governments across the region not to distort the level playing field with domestic businesses, and to integrate the current measures to support the relocation of Russian businesses into their longer-term reforms to the business environment. In addition, retaining these new talents, while maintaining social peace, will require policies to prevent the further polarisation of labour markets.