Trade in counterfeit goods represents a longstanding, global socio-economic risk that threatens effective public governance, efficient business, and the well-being of consumers. At the same time, it is becoming a major source of income for organised criminal groups. It also damages economic growth, by reducing business revenue and undermining businesses’ incentive to innovate. Counterfeiting not only has a corrosive impact on the sales and profits of affected firms and on the economy in general, but also poses threats to social welfare and public safety. In addition, in some high-risk sectors, such as that of illicit pharmaceuticals, food or alcohol, the presence of counterfeit goods poses particularly severe health and safety threats for citizens.

Factors that drive imports of counterfeits include those that shape unknown and known demands. Unknown demand is expressed by unaware consumers who are deceived by bad actors, and who buy a fake believing it was genuine product. Known demand is generated by consumers who consciously opt for counterfeits. Existing customs seizures data suggest that around 54% of imported counterfeit and pirated products between 2017 and 2019 were sold to consumers who knew that they were buying fake products. while the remaining 46% was purchased unwittingly. The proportion of consumers who knowingly demand counterfeits differs by product type, ranging from 11% for chemicals to 57.3% for electronic appliances.

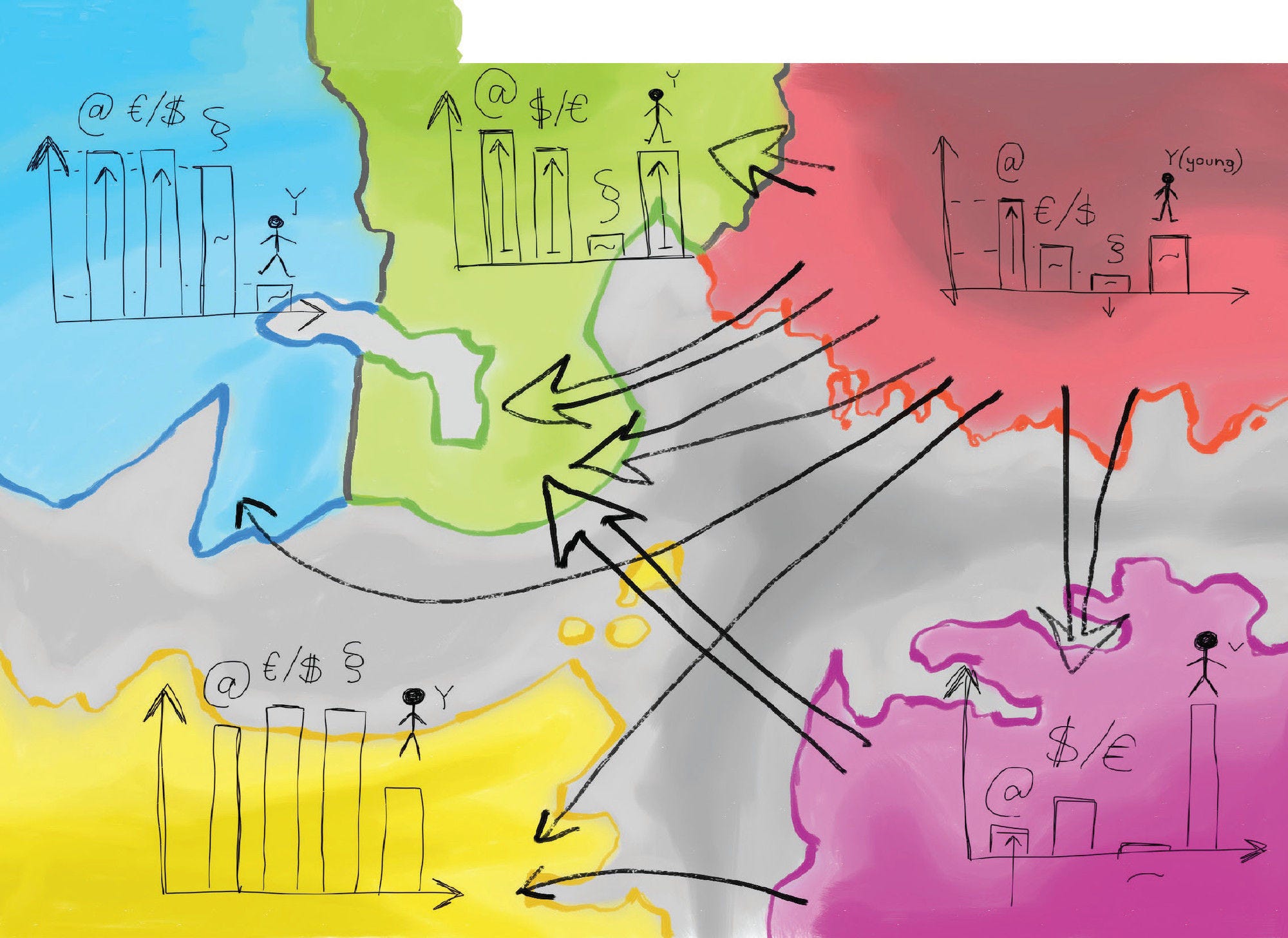

Existing microeconomic research identifies several drivers that shape both intentional demand and unintentional propensity to buy fakes. Most of these factors are related to the individual consumer, including his or her general economic situation, knowledge about counterfeiting and piracy and attitude towards it, and concerns related to the purchase and consumption of a counterfeit or pirated good. Other factors are related to the product itself (e.g., its price or perceived quality), and the institutional environment in which the consumer operates.

These factors were determined at an individual level, but the macroeconomic analysis presented in this report attempts to verify these claims at a macroeconomic, country level. Looking at import statistics and seizures data, the analysis confirms some microeconomic patterns. While some links are clear, others are more difficult to determine and interpret, and require further analysis.

Factors that are clearly correlated with the value of imports of fakes include:

The value of imports of a country. The analysis shows a very strong and positive correlation between the value of fake imports and the value of genuine imports.

GDP per capita. The analysis finds that, combined with other factors, a higher GDP per capita of a country is associated with fewer imports of fakes to those countries. Importantly, according to numerous studies, GDP per capita is positively correlated with the overall level of respect for intellectual property (IP) in a country. Indeed, countries with a low GDP per capita, which have both economic constraints and weak regulation of intellectual property protection, have a higher propensity to import counterfeit products. Consequently, this finding suggests that strengthening the level of IP protection in a country could lead to a reduction in counterfeit imports.

The quality of trade and transport infrastructure. The analysis in this report finds that the quality of logistics and transport-related infrastructure tends to facilitate counterfeit imports to the same extent they facilitate licit trade, in countries with relatively low governance standards related to IP respect and protection. This result corroborates the trends already highlighted by the OECD and the EUIPO that counterfeiters abuse modern logistical solutions designed to facilitate licit trade.

The share of population aged 65 and over is negatively linked with the amount (in terms of value) of fake imports. There could be several mechanisms to explain that pattern, including a greater awareness of the threat of counterfeiting, relatively lower economic constraints for the elderly compared to younger people, and fewer online purchases by older people.

The percentage of people using the Internet. The analysis shows that the use of the Internet is positively correlated with the value of fake imports; it confirms prior findings about the rising role of the Internet in facilitating trade in counterfeit goods. It also reflects the overall ease of deception in the online environment.

Tertiary education. The data show a positive relationship between the gross graduation ratio of tertiary education and the value of imports of counterfeit goods. Several underlying factors can explain such a relationship, including possible lack of awareness about this risk (including the presence of counterfeit goods in all sectors and not only in the fashion or luxury goods sectors), combined with a higher ability to look for bargains online. More research to understand this relationship is needed, however.

While all the factors identified above are important, it should be noted that none of these factors alone can explain the propensity of a given economy to import fakes – rather, it is the combination of numerous factors that shapes the known and unknown demand for fakes, and, consequently, the propensity for importing counterfeit goods. Also, many of the factors presented above can be extremely beneficial for trade in general, and – more broadly – for a country’s welfare. These include good logistics facilities and Internet access. It is the misuse of these facilities, and the abuse of opportunities they create, that can result in higher flows of trade in fake goods. The degree to which this misuse occurs greatly depends on governance issues, particularly the degree of IP protection. The policy challenge is to reduce the scope for misuse, while ensuring the benefits of trade.