Tackling major challengs, population ageing and shrinking labour force, is crucial for Japan to achieve more growth and ensure the financial sustainability of its public social expenditures. Wide range of policy efforts including reform of the Japanese traditional employment system should be taken to increase the elderly and female participation in the labour market to mitigate the negative impact of shirinking population on Japan’s economy.

Working Better with Age: Japan

Chapter 1. Employment of older workers in times of transition in Japan

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Rapid population ageing and a shirinking labour force in Japan are major challenges for achieving further increases in living standards and ensuring the financial sustainability of public social expenditures. With the right policies in place, there is an opportunity to cope with these challenges by extending working lives and making better use of older workers’ knowledge and skills. Chapter 1 highlights that there is still scope for increasing further the participation of older people in the labour market. However, as discussed in the following chapters, the current conditions under which older people work are not always very satisfactory. Chapter 2 investigates the barriers to retention and hiring of older workers and suggests several policy responses. Chapter 3 focuses on a particularly important aspect: increasing the employability of older workers. This includes encouraging skill development amongst older workers as well encouraging and helping older jobseekers to find work. Finally, Chapter 4 considers what policy measures are required to improve working conditions for older workers.

Employment of older workers in times of transition

Around the world, rapid population ageing has driven the development of policies to extend working lives. There are a number of policy levers, many on the side of retirement policies to strengthen incentives to retire later. But an increasing number of countries are also focusing on employment behaviour of firms and the employability of older workers, including: extending or abolishing the mandatory retirement age; fighting age discrimination; promoting further training over the whole working life; encouraging age‑management approaches by employers; strengthening employment services for older job‑seekers; and improving the health of older workers through good workplace practices throughout working careers.

The policy measures that need to be taken and their effectiveness will depend on macro‑economic, institutional, and cultural context and the actual labour market situation of older workers in each country. Therefore, this chapter thus reviews the current and future situation of older workers in the Japanese labour market. A number of key issues are highlighted. First, the current tight labour market in Japan is creating favourable macroeconomic conditions for the employment of greater numbers of older workers, which would contribute to reducing the decline in the labour force and help support the financial sustainability of the pension system. Second, the policy responses to encourage longer working lives and higher employment at older ages will need to be tailored to the different labour market situations that older Japanese face.

Given rapid population ageing, promoting work at an older age is more important than ever

Longer working lives could help limit the decline in Japan’s workforce

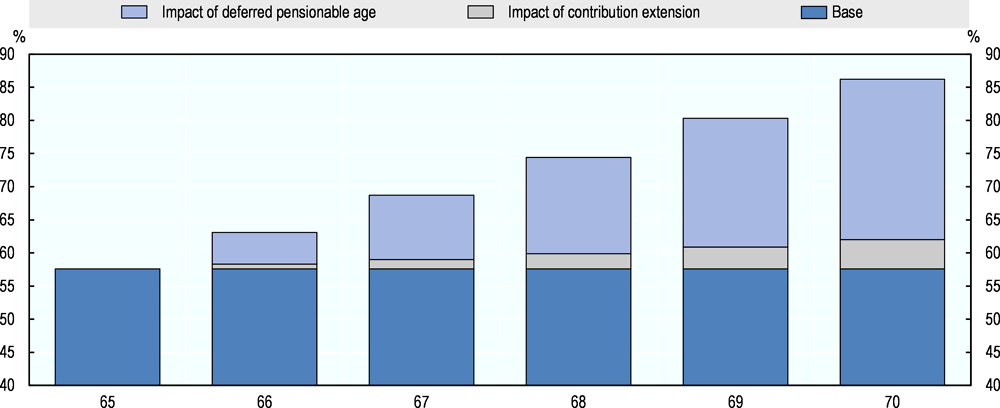

Population ageing in Japan has progressed further and more rapidly than in most other countries. Japan displays the highest old-age dependency ratio of all OECD countries, with a ratio in 2017 of over 50 persons aged 65 and over for every 100 persons aged 20 to 64 and this ratio is expected to increase further to 79 per hundred in 2050 (see Figure 1.1).

This trend is putting considerable pressure on the financial sustainability of Japan’s social security system. The basic old-age pensionable age is 65 years old, although people can choose to start taking pensions at any point between aged 60 and 70 with less or greater monthly payments compared to those who start at age 65. Thus, an increase in the population after the age of 65 has a direct impact on pension expenditure. In addition, medical expenses tend to rise steeply at older ages. In particular, expenses increase sharply after the age of 75 (MHLW, 2016[1]). Key crunch years will occur in 2025 when the first baby boomers will be 75 years or older and in 2035 when the second baby boomers will reach the age of 65. Extending working lives would help to limit the decline in the workforce and boost social security contributions to finance rising health and pension expenditures.

Figure 1.1. Population ageing is already well advanced in Japan and will progress further

Note: The OECD is a weighted average.

Source: OECD Population and Labour Force Projections Database (unpublished).

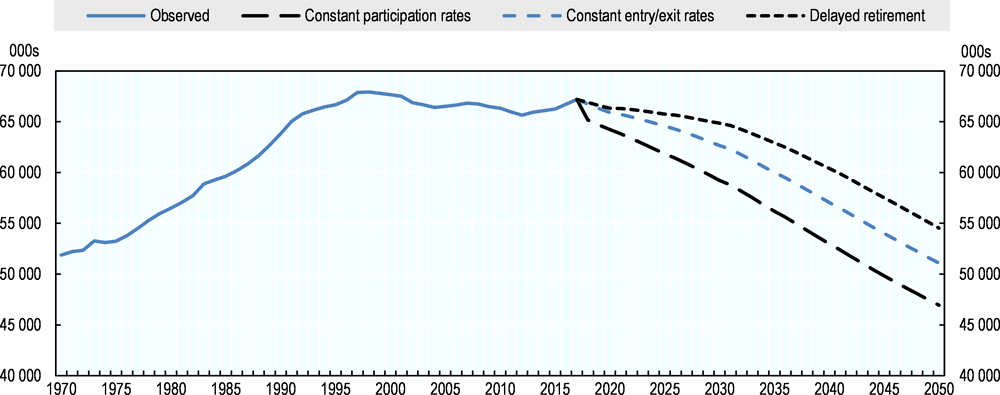

It would also help to relieve concerns about current and future labour shortages (Bank of Japan, 2014[2]). Japan’s working-age population (persons aged 15-64) has already been declining since the late 1990s and this decline is likely to feed through to a considerable decline in the total labour force over the next few decades. If labour force participation rates by age and gender remain unchanged at their 2017 levels, the labour force could contract by 8 million between 2017 and 2030 and by 20 million by 2050 (Figure 1.2). Unemployment is at a very low level currently and so there is little scope to offset this decline through further falls in its level. Instead, given that older people will account for a large and increasing share of the population, they would make the biggest contribution to reducing the decline in the overall labour force if more of them were working. This can be illustrated through two scenarios.1

The first “baseline” scenario for the projection period 2017-50 assumes that labour force entry and exit rates over a 5-year period by 5-year age groups and gender remain constant at their average rate observed for each 5-year period 2007-12 to 2012-17.2 In this case, there will be some increase in participation rates, especially for older women (and older men aged 65 and over), as these fixed exit rates will apply to participation rates that are higher currently for these groups than previously. This is quite a realistic scenario in that it simply implies unchanged retirement behaviour. In other words, older people who are in the labour force at any period continue to withdraw from the labour force at the same rate as occurred over the recent past. Similarly, those outside of the labour force for each age‑group and gender continue to enter the labour force at the same rate each year. Under this scenario, the labour force would contract by around 4.5 million by 2030, i.e. 3.5 million less than if participation rates remain unchanged.

The second “delayed retirement” scenario takes into account the fact that retirement behaviour has not remained unchanged over the recent past and that there is scope for government policies to encourage and facilitate later retirement. It therefore assumes that the average effective age of retirement rises by 1.1 and 0.7 years for men and women, respectively, by 2030. It does this by adjusting exit rates downwards for both men and women by 10% from the age of 55 onwards. Under this scenario, the labour force would contract by only around 2.4 million by 2030, i.e. 5.6 million less than if participation rates remain unchanged.

Is this second scenario plausible? The increase in the effective retirement age by gender between 2017 and 2030 would, in fact, be similar or lower than the increase of 1.1 years for men and 3.2 years for women that occurred over the period 2004‑17. Moreover, the projected increase in the effective age of retirement would still be slightly less than the projected increase in life expectancy. Thus, the expected number of years in retirement would increase marginally from 15.2 years in 2017 to 15.4 years in 2030 for men and from 20.5 to 21.0 years for women.

Figure 1.2. Later retirement by older people would reduce the decline in Japan’s labour force

Note: The projections based on constant participation rates assume that participation rates by gender and 5-year age groups remain fixed at their 2017 levels. The projections with constant entry/exit rates assume that labour force entry and exit rates over a 5-year period by gender and 5-year age groups remain constant at their average rate observed in the period 2008-17. The projections with delayed retirement are the same as for the projections with constant entry/exit rates but with exit rates from age 55 onwards adjusted downwards by 10%, phased in over the period 2017-30.

Source: OECD projections based on data from the OECD Population and Labour Force Projections Database (unpublished).

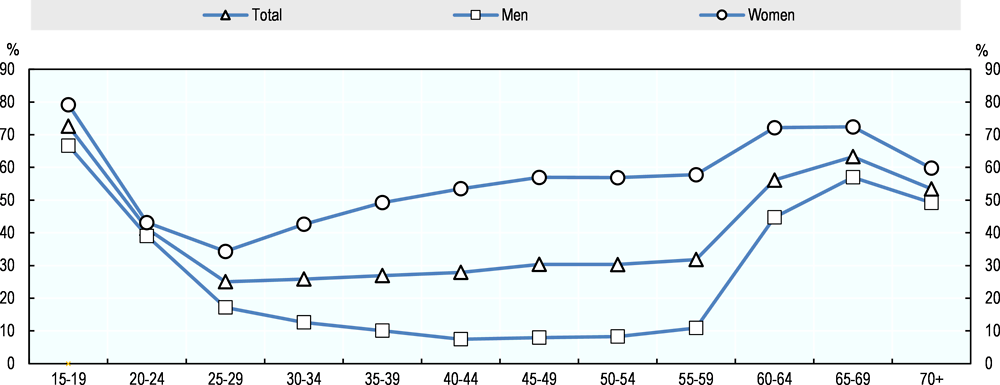

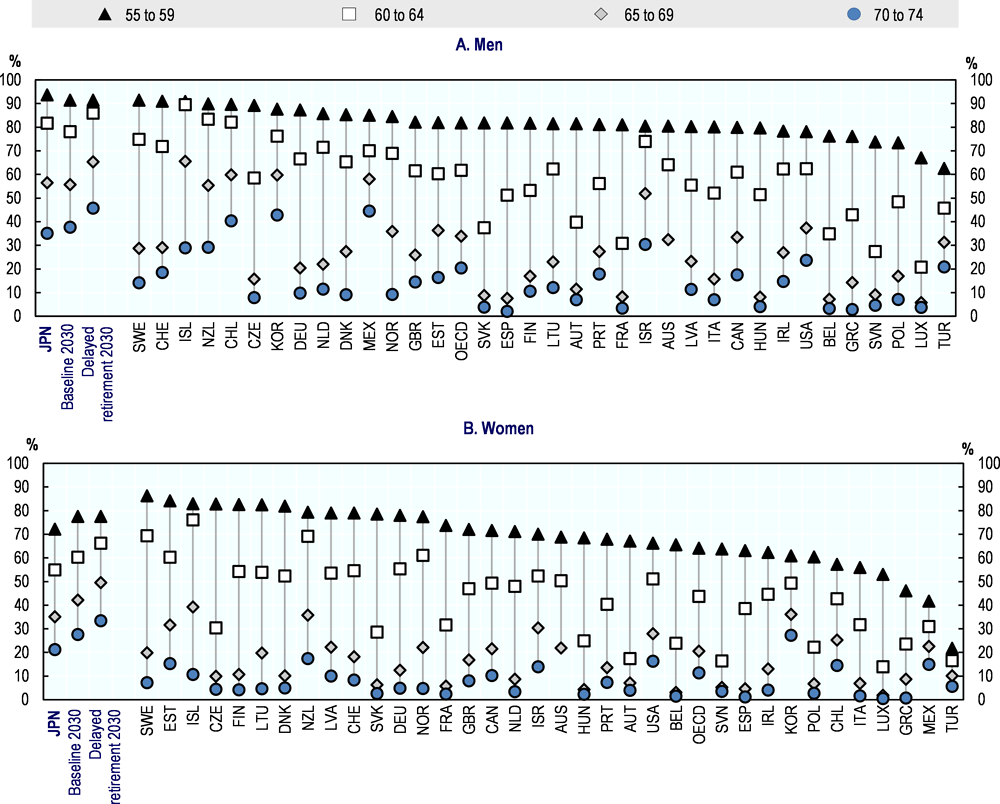

Figure 1.3. Japan already has some of the highest participation rates for older people among OECD countries

Note: The OECD is a weighted average. The baseline and delayed retirement variants refer to projections for Japan for 2030. The baseline projections assume unchanged labour force entry and exit rates by age group and gender. The delayed-retirement variant assumes that exit rates from the labour force after the age of 55 decline by 10% in each age group, leading to a rise in the average effective retirement age of 1.1 and 0.7 years for men and women, respectively, by 2030.

Source: OECD LFS by sex and age - indicators dataset: http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=64198; and OECD projections (unpublished) for 2030 for Japan.

The projected labour force participation rates by gender and broad age group under the second “delayed retirement” scenario can also be compared with their current values in Japan and other OECD countries (Figure 1.3). Currently, participation rates are already higher for older men in Japan than in nearly all OECD countries, except for Chile, Iceland and New Zealand. Thus, the challenge for Japan will be to not only maintain this gap but raise participation rates further as indicated by the projected rates for 2030. Participation rates for older women are also higher currently in Japan than in most other OECD countries. However, a number of countries have higher rates for women in their late 50s and early 60s, such as Estonia, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden. Under the delayed retirement scenario, participation rates for women in these age groups would be higher than previously but still below the highest rates current observed among OECD countries. In contrast, the rate for women in their late 60s and early 70s would exceed those observed currently for any OECD country. In addition, for women aged 25-54, participation rates are lower in Japan than in a number of other OECD countries. This suggests that in order to fully mobilise its labour resources, Japan will need to raise labour force participation of women both at younger ages as well as at older ages.

Increased labour force participation by older Japanese would also contribute significantly to the fiscal sustainability of social security

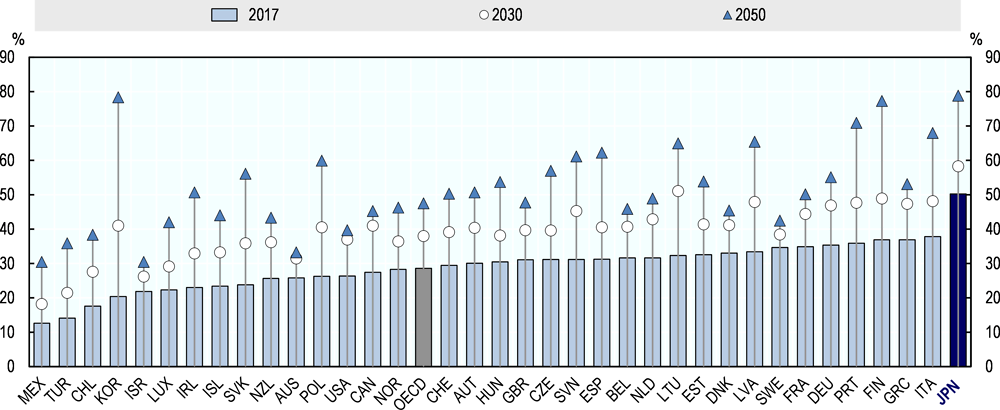

An increase in the labour force participation for older people and prime-age women in Japan would not only serve to partially offset the negative effects of population ageing on the size of the workforce, but would also help to bolster incomes and pensions at older ages. This is particularly important in Japan, where the relative poverty rate of people aged over 65 years is 19.6% against 12.5% on average in the OECD (OECD, 2017[3]). The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has estimated the impact of a longer working life on the maximum pension replacement rate (MHLW3, 2014). The current maximum rate is 51% assuming the current maximum contribution period of 40 years, e.g. between the ages 20-60, and a pensionable age of 65. If instead, workers contribute for 50 years (e.g. working throughout ages 20-70), the replacement rate would reach 86.2% (Figure 1.4). The increase is attributed largely to the deferred pensionable age in the estimation. This may appear ambitious, and in reality many individuals do not currently contribute for 40 years (especially women). Record low unemployment and a further increase in life expectancy that is already high relative to other countries may nevertheless create the space for a rise in the number of contribution years in the future.

Figure 1.4. Impacts of contribution extension and deferred pensionable age on pension replacement rate as of 2058

Tailoring policies to the specific situation of older workers

How then can public policy foster higher labour market participation at older ages? Other countries facing rapid population ageing and labour shortages have developed strategies to increase labour supply. One example is Germany (see Box 1.1), However, the policy responses required by Japan will depend on the specific situation of older people with respect to the labour market. Three groups stand out: i) those workers who have benefited from Japan’s system of lifetime employment but who face and uncertain transition into retirement after the age of 60; ii) the rising share of non-regular workers outside of the lifetime system; and iii) the situation of many older women who have been involved in non‑regular work at younger ages or left the workforce completely. Each of these groups faces different barriers to continuing to work at an older age which must be addressed.

Box 1.1. Germany’s strategy for dealing with labour shortages

The German government’s strategy for “Securing Skilled Labour” (Fachkräftesicherung) was announced in 2011 (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, 2011). Five pathways and objectives have been defined: i) activating and retaining older workers and activating unemployed; ii) improving reconciliation of work and family life; iii) promoting access to education starting from childhood for all groups in society; iv) encouraging initial and further vocational training; and v) improving the integration of immigrants as well as attracting skilled immigrants. The government regularly publishes monitoring reports evaluating the implementation of this strategy

Japan’s traditional lifetime employment system is under strain

In part, high rates of employment for Japanese men in their 50s can be explained by Japan’s lifetime employment system. Under this system, large corporations will typically hire graduates to work as generalists across different jobs with the promise of seniority‑based wage increases until workers are in their 50s and guaranteed employment until the mandatory retirement age of 60. This system has been considered to contribute to the productivity of companies and their competitiveness. Companies acquire company specific skills by investing in their workers from a long-term perspective and they gain from high-levels of motivation by their workers who will see their wages rise the longer they stay with the company (i.e. with seniority) (Koike, 1988[4]). However, this system is coming under increasing strain because of structural changes in the economy which are making it harder for companies to guarantee a job for life.

This model is far from universal in the Japanese labour market (Table 1.1). It is typically more prevalent in large firms, where it covers between one third and one half of workers, and much less common in small firms. While this type of contract is most often associated with the manufacturing sector, it is also extensively used by large firms in other sectors. The proportion of workers who have worked continuously with the same employer since leaving education tends to decline with age as it becomes more likely that some individuals will change their employer (either voluntarily or involuntarily) the longer they have been in employment. Many do not move: in large manufacturing firms, 48% of graduates aged 50‑59 have never switched employer. While school graduates benefit much less frequently from lifetime employment contracts than university graduates, gender differences are small for graduates before the age of 40 (Table 1.2) but diverge substantially thereafter as many women quit their career jobs for family reasons and if they re-enter the labour market it will often be in a new job.

Table 1.1. Lifetime employment is frequent in large firms and not only in manufacturing

Lifetime employees as a share of all employees by age, firm size and sector, 2016

|

Age |

Large firms |

Medium firms |

Small firms |

|---|---|---|---|

|

15-29 |

52.4 |

49.9 |

32.4 |

|

30-39 |

31.0 |

24.6 |

11.8 |

|

40-49 |

36.8 |

23.3 |

8.9 |

|

50-59 |

38.9 |

20.6 |

7.3 |

|

Manufacturing |

|||

|

Age |

Large firms |

Medium firms |

Small firms |

|

15-29 |

52.3 |

52.3 |

33.4 |

|

30-39 |

31.2 |

27.9 |

13.1 |

|

40-49 |

42.4 |

29.3 |

10.5 |

|

50-59 |

46.1 |

26.0 |

7.9 |

|

Non-manufacturing |

|||

|

Age |

Large firms |

Medium firms |

Small firms |

|

15-29 |

52.5 |

48.8 |

32.0 |

|

30-39 |

31.0 |

23.3 |

11.4 |

|

40-49 |

34.3 |

21.1 |

8.3 |

|

50-59 |

35.7 |

18.7 |

7.1 |

Note: Lifetime employees are all employees who were continuously employed by enterprises directly after graduating from school or university. Large firms: more than 1 000 employees; medium firms: between 100 and 999; small firms: between 10 and 99.

Source: Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Basic Wage Survey, 2016.

Table 1.2. Graduates more often have lifetime employment contracts and women as frequently as men before age 40

Lifetime employees as a share of all employees by age, gender and graduate status, 2016

|

Age |

Female junior or high-school graduates |

Female university graduates |

Male junior or high-school graduates |

Male university graduates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

All ages |

14.3 |

43.9 |

21.0 |

37.9 |

|

15-29 |

32.1 |

69.2 |

37.8 |

58.2 |

|

30-39 |

11.0 |

34.0 |

15.9 |

32.3 |

|

40-49 |

10.1 |

22.2 |

18.5 |

33.1 |

|

50-59 |

6.3 |

14.5 |

17.1 |

33.9 |

Note: Lifetime employees are all employees who were continuously employed by enterprises directly after graduating from school or university.

Source: Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Basic Wage Survey, 2016.

Lifetime employment is somewhat rarer today than it used to be (Table 1.3). For workers in their 30s and 40s in large firms, there has been a reduction of the proportion employed with the same employer since leaving education of 9 to 15 % points between 2006 and 2016. This is consistent with an earlier study by (Kawaguchi and Ueno, 2013[5]) using both the Employment Status Survey and the Basic Survey on Wage Structure which found a continued decline of job stability for men across all firm sizes.

Table 1.3. Lifetime employment is less prevalent today than ten years ago in most age groups

Change in the share of employees who are lifetime employees by age and firm size, 2006-16 (in percentage points)

|

Age |

Large firms |

Medium firms |

Small firms |

|---|---|---|---|

|

15-29 |

1.1 |

2.9 |

2.1 |

|

30-39 |

- 15.0 |

- 7.6 |

- 1.2 |

|

40-49 |

- 9.4 |

- 4.3 |

- 1.5 |

|

50-59 |

-1.9 |

- 0.8 |

0.0 |

Note: Lifetime employees are all employees who were continuously employed by enterprises directly after graduating from school or university. Large firms: more than 1 000 employees; medium firms: between 100 and 999; small firms: between 10 and 99.

Source: Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Basic Wage Survey, 2006 and 2016.

Workers after mandatory retirement face a difficult transition to full retirement

Not only is the lifetime employment system becoming less common but it only provides for stable employment up to the mandatory retirement age. After that age, many firms may require workers to leave because they have a policy of mandatory retirement or they will re‑hire their older workers but in a different job function at a much lower wage. Firms do this because as part of their lifetime employment system they have a seniority‑based pay system that rewards workers for each additional year of service. However, as discussed further in Chapter 2, this makes older workers expensive relative to their productivity which creates a barrier to their continued employment (Frimmel et al., 2015[6]).

Following mandatory retirement many older workers are required to switch job duties as well their status from regular employees to non-regular employees. In 2017, the share of all employees who were non-regular employees jumps from only 12% for men aged 55‑59 to 52% for men aged 60-64 (Figure 1.5). Thus, not only do many older workers face a large cut in wages following mandatory retirement from their lifetime jobs but they also switch to jobs that are more precarious. Moreover, as discussed in Chapter 4, this can have negative consequences for their productivity as they may be less motivated because of lower job satisfaction and also because they may not be fully utilising the job-specific skills they acquired prior to mandatory retirement.

Labour force participation of women at all ages can be improved

In Japan, many women leave employment following marriage and child birth. Some of them subsequently come back to work and indeed the typical “M” shape in women’s participation rates by age (starting to rise after completion of initial education, then falling after childbirth prior to rising again in their 40s and 50s and subsequently declining once more as they retire) has become less pronounced over recent decades. Nevertheless, women’s participation in the age group 25-54 remains well below the levels in many other advanced OECD countries.

Moreover, most women re-entering the labour force find jobs in non-regular employment rather than regular employment and from the age of 35 onwards, the majority of female employees are non-regular employees (Figure 1.5). Consequently, there is a double challenge for policy with respect to women which is to both raise their participation rates at all ages and to improve their access to regular employment. These issues are discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, especially the need to improve work-life balance for women, tackle long hours of work and reduce labour market duality.

Figure 1.5. Many workers become non-regular employees after reaching 60 years old

References

[2] Bank of Japan (2014), Deflation, the Labor Market, and QQE.

[6] Frimmel, W. et al. (2015), “Seniority Wages and the Role of Firms in Retirement”, http://hdl.handle.net/10419/114065 (accessed on 24 May 2018).

[5] Kawaguchi, D. and Y. Ueno (2013), “Declining long-term employment in Japan”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2013.01.005.

[4] Koike, K. (1988), Understanding industrial relations in modern Japan, Macmillan, https://www.palgrave.com/us/book/9780333426869 (accessed on 02 August 2018).

[1] MHLW (2016), Basic Statistics on Health Care Insurance 2014, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-12400000-Hokenkyoku/kiso26_teisei_3.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2018).

[3] OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

Notes

← 1. In all cases, the labour force projections are based on Japan’s national population projections produced by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

← 2. More specifically, it is assumed that labour force entry and exit rates over a 5-year period by 5‑year age groups and gender remain constant at their average rate observed in the period 2008-17. Labour force exit rates over a 5-year period are calculated as the ratio of the participation rate for each 5‑year age group at the end of the period relative to the participation rate of the same age group aged 5 years younger at the beginning of the period. Entry rates are calculated in the same way except the rate of non-participation is used,