At least seven public administrations in the MENA region have adopted national youth strategies to promote a joint vision, coordinated approach and policy coherence in support of young people. This chapter benchmarks the arrangements in place against the eight principles of good governance set out in the OECD Assessment Framework of National Youth Strategies. It finds that, while national youth strategies are more widespread than in the past, their impact has often been limited due to challenges in involving young people in their design and implementation, as well as a lack of administrative capacities, resources, and monitoring and evaluation systems.

Youth at the Centre of Government Action

2. Uniting government stakeholders behind a joint strategy for young people

Abstract

Young people have specific needs and interests across all policy and service areas including in employment, education, health, justice, housing, transportation, sports, gender equality and environment, among others (OECD, 2020[1]). Adopting a whole-of-government approach in youth policy can ease the transition of young people to an autonomous life by ensuring that government action is well coordinated across different departments and agencies. A joint vision can also mobilise subnational government stakeholders as well as non-governmental stakeholders and coordinate their respective interventions. Instead, weak coordination between departments that operate within their own organisational structures risk to result in a fragmented delivery of the public services young people require to manage the various transitions that are characteristic of this period in life.

The COVID-19 crisis has further underscored the need for integrated approaches to the delivery of public programmes and services to young people. Like elsewhere, young people in MENA have faced unprecedented challenges as a result of the crisis (see Chapter 1), notably in the fields of education, employment, mental health and disposable income (OECD, 2020[2]). For instance, OECD estimates show that a lost school year can be considered equivalent to a loss of between 7% and 10% of lifetime income (OECD, 2020[3]). As discussed in Chapter 1, under a pessimistic scenario, approximately 800 billion USD of aggregated lifetime earnings could be lost for the current cohort of learners in MENA (UNESCO, UNICEF and World Bank, 2021[4]).1 Furthermore, youth aged 15-24 were most affected by the rise in unemployment at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis between February and August 2020 (OECD, 2020[5]), adding to already very high levels of youth unemployment in the region (ILO, 2019[6]).

Governments must seek to create an environment in which young people of all backgrounds and circumstances have access to quality public services in order to avoid that inequalities at a young age will compound over the life cycle (OECD, 2020[1]). Disruptions in this period of life create significant long-term costs for societies and economies, undermining social cohesion, productivity levels and inclusive growth (OECD, 2020[1]). Findings from the OECD report “Governance for Youth, Trust and Intergenerational Justice: Fit for All Generations?” demonstrate that adopting an integrated approach to youth policy and service delivery can help address these challenges (OECD, 2020[1]).

This chapter will review the efforts undertaken to design and implement national integrated youth strategies.

It is organised in three sections:

It will discuss the benefits of investing in the quality of national integrated youth strategies and introduce the OECD Assessment Framework of National Youth Strategies;

It will benchmark practices against the eight principles of good governance of the OECD Assessment Framework for National Youth Strategies and provide comparative evidence and practices from across MENA and OECD administrations; and

Based on the assessment, it will present policy recommendations to support the formulation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of national integrated youth strategies.

A glance at constitutional reform in MENA

Young people in the MENA region are key actors for alleviating development challenges and promoting positive change (UNDP, 2017[7]). Following the uprisings in 2011, constitutional reform processes have been launched in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Yemen, which have led to the adoption of new constitutions in Egypt (2012 and 2013) and Tunisia (2014), and constitutional reforms in Algeria (2016), Jordan (2011 and 2022), and Morocco (2011) (Boubakri, 2018[8]). In some countries, these reforms have resulted in more explicit references to young people in the Constitution. Across OECD countries, 7 constitutions list direct references to equality regardless of age as of 2022 and 8 constitutions list direct references to future generations as of 2020 within their constitutions (Constitute Project, 2022[9]; OECD, 2020[1]).

In the MENA region, for instance, Article 8 of Tunisia’s Constitution of 2014 refers to young people as “an active force in nation-building” (République Tunisienne, 2015[10]). It requires the state to provide young people with the necessary conditions to reach their full potential and ensure their participation in the country’s social, economic, cultural, and political development. The constitution also stipulates that the electoral law shall guarantee the representation of young people in local councils (Article 133). In Morocco’s Constitution, Article 33 refers to the needs of young people and recognises for the first time the importance of their participation in civil society. Article 170 stipulates that a Consultative Council of Youth and of Associative Actions shall be formed to develop a national strategy and coordinate policy efforts for youth inclusion in national life and citizenship.

Youth laws can support policy coherence and coordination

National youth laws are legislative frameworks that identify the main stakeholders, fields of action and responsibilities among state institutions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working with and for young people (OECD, 2020[1]). They often define age brackets for what are considered “young people” and youth institutions, indicate the role of the executive branch in terms of delivering policies, programmes and services to young people and to whom they are targeted, as well as financial and budgetary considerations (OECD, 2020[1]). OECD research shows that youth laws can encourage policy coherence and inter-ministerial coordination: OECD countries that adopted a youth law are less likely to report as challenge the lack of clear mandates or lack of incentives among governmental stakeholders to coordinate with each other on youth policy (OECD, 2020[1]).

As of 2020, 14 OECD countries adopted a national youth law (OECD, 2020[1]). In some OECD countries, youth laws also regulate the support provided by the government to non-governmental stakeholders in the youth field. For instance, in Finland, Luxembourg and Slovenia, youth laws clarify the status and functions of the national youth council and outline the conditions that must be met for becoming a member in the council (OECD, 2020[1]). Box 2.1 presents the examples of national youth laws in Colombia and Finland.

Box 2.1. National youth laws in selected OECD countries

Colombia

Colombia adopted a Statutory Law on Youth Citizenship (Ley Estatutaria de Ciudadanía Juvenil) in 2013 to establish the institutional framework of youth policy and youth work and to define young people’s rights. It creates a National Youth System (Sistema Nacional de la Juventudes), which allows for young people’s active participation in the design, implementation, and evaluation of youth policy. The Law also stipulates that the Presidential Council for Youth (Consejeria Presidential para la Juventud) manages the system and promotes the implementation of the national youth policy. Furthermore, it lays out roles and missions of local governments and territorial bodies in implementing youth policies and measures to ensure effective coordination with the Presidential Council.

Finland

In 2016, Finland renewed its Youth Act dating back to 1972. The legislation targets all persons below the age of 29 and covers all aspects of youth work and activities and youth policy across all levels of government. It identifies the Ministry of Education and Culture as the primary state authority responsible for the administration, coordination, and development of the national youth policy, in cooperation with other ministries and central government agencies as well as local authorities, youth associations and other relevant organisations. For each stakeholder, the Youth Act specifies key roles and responsibilities in the youth field. It also clarifies the conditions national youth work organisations must meet to benefit from the transfer of state subsidies.

Source: (European Commission, 2017[11]; OECD, 2020[1]).

As of 2022, none of the public administrations in the MENA region covered in this report had adopted a comprehensive national youth law. However, some governments have passed laws to define the responsibilities of the lead ministry in charge of youth affairs or put in place legislation in different sectors to better define responsibilities. In Jordan, for instance, Regulation No. (78) of 2016 on “the administrative organisation of the Ministry of Youth” spells out its organisational structure after the transition from the Higher Council for Youth to the creation of a dedicated ministry (OECD, 2021[12]).

While Tunisia has not adopted a national youth law, various sectoral laws and youth-specific commitments address youth policy (OECD, 2021[13]). The government has adopted three major texts that shape young people’s representation in public and political life, their participation in policymaking and their involvement in society: the 2014 Constitution (République Tunisienne, 2015[10]), the 2014 and 2017 electoral laws (République Tunisienne, 2017[14]), and the 2018 Local Authorities Code (République Tunisienne, 2018[15]).

The absence of a comprehensive national youth law does not necessarily indicate that governments give less importance to the concerns and perspectives of young people in policymaking and public service delivery. Youth policy can be defined further in sectoral laws instead as is the case in Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia, for instance. Morocco has passed several laws in order to strengthen the representation of young people in politics, encourage their participation in the policy cycle and to involve young people in society. However, as evidence from across the OECD countries presented above demonstrates, national youth laws can help encourage multi-level and multi-stakeholder coordination.

More countries elaborate national youth strategies but results often remain behind expectations

National Youth Strategies (NYS) have emerged as guiding frameworks to shape a vision for young people and deliver programmes and services in a coherent manner across administrative and ministerial portfolios. They can also mobilise public (and private) resources for youth programming and set and communicate the rationale, objectives and expected outcomes of government action targeting youth. Investments in the quality of NYS pay off with a return. In OECD countries that rank high in the OECD Assessment Framework for National Youth Strategies, which will be introduced below, young people are more likely to express greater interest in politics (OECD, 2020[1]).

As of 2020, 25 out of 33 OECD countries that responded to the OECD Youth Governance Survey had an operational national or federal youth strategy in place (OECD, 2020[1]). The three top motivations highlighted in relation to the adoption of a NYS are to support young people in their transition to an autonomous life (100%), to engage them in the decision-making process (88%) and to integrate their concerns across all relevant policy and service areas (84%) (OECD, 2020[1]). They encompass government commitments across various policy and public service areas, covering measures to encourage young people’s participation in public and political life (100%); and improve opportunities and outcomes in the field of employment and economy (96%); education and training (96%); health (92%); and sports, culture and leisure (84%) (OECD, 2020[1]). Youth strategies also exist at subnational level across OECD countries. For example, in 2017, the municipality of Gaia in Portugal adopted a five-year municipal youth plan to foster equal opportunities and social cohesion (Municipal Council of Gaia, 2017[16]).

Box 2.2. Examples of integrated national youth strategies

New Zealand

The Government of New Zealand released its Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy in August 2019 to improve the well-being of young people under the age of 25. The development of the strategy was jointly led by the Minister for Child Poverty Reduction (a portfolio held by the Prime Minister) and the Minister for Children, demonstrating strong political support from the top. The strategy includes six outcome indicators, reported to Parliament annually. For each outcome, data will be disaggregated when possible by household income or socio-economic status and ethnicity to take into account the impact of intersecting identities. The Child Wellbeing Unit within the Department of the Prime Minister acts as the lead institution to monitor implementation. 20 more government agencies have some responsibility for its implementation. Overall, the chief executives of these agencies, and by extension their respective line Ministers, are accountable for more than 110 individual actions.

Austria

In Austria, each federal ministry is required to develop at least one national “youth objective” related to its own sphere of competence to encourage a cross-sectoral approach in the implementation of the Austrian Youth Strategy. Each objective should contribute to improving the conditions of young people. An external agency assisted each federal ministry in defining and formulating their objectives and a cross-sectoral working group was created to foster dialogue. Focus groups with young people called “Reality Check” were organised to receive young people’s feedback and integrate their views.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]).

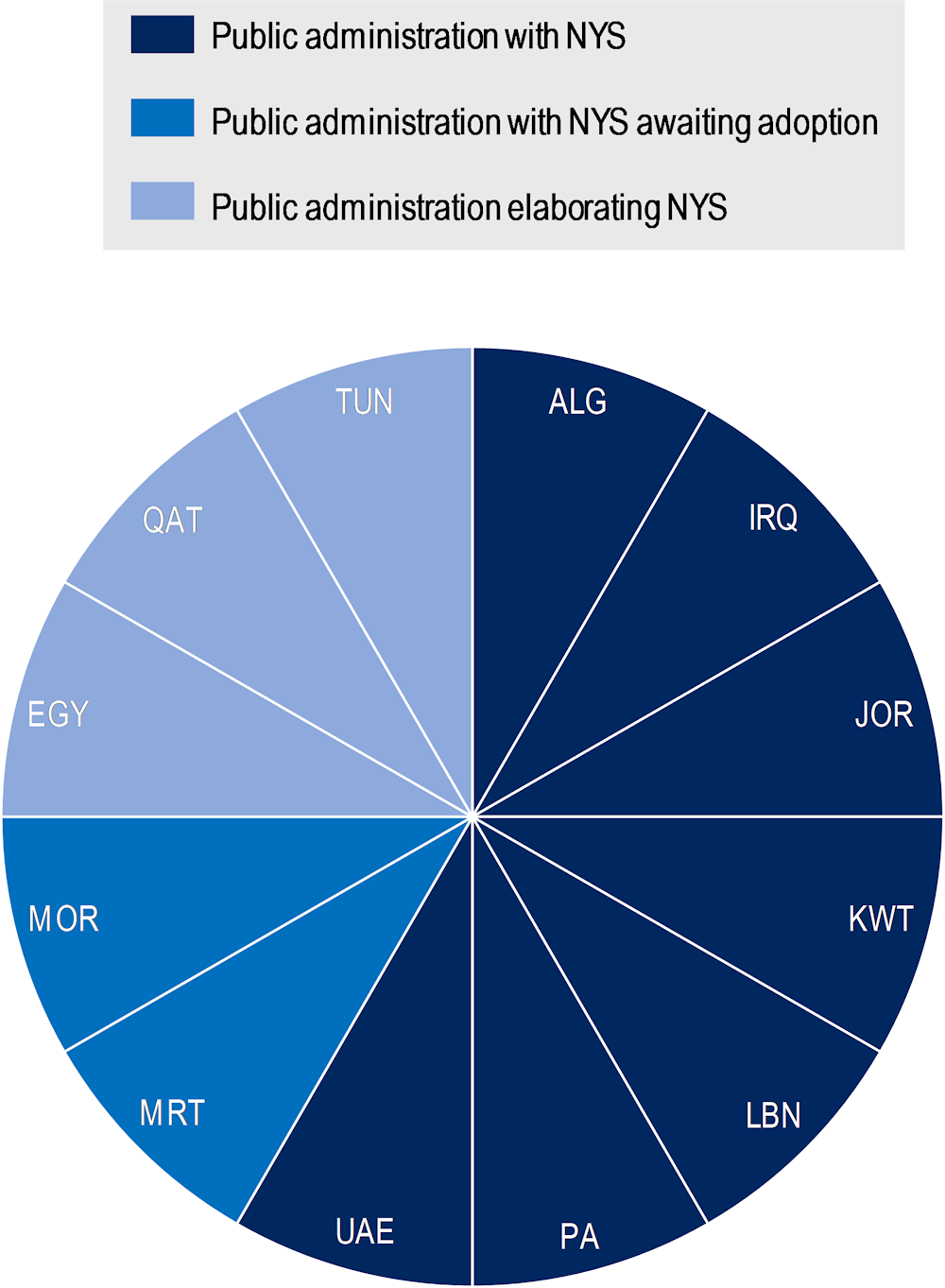

Based on the survey replies of public administrations in the MENA region to the OECD Youth Governance Survey and further desk-based research, as of 2022, at least seven have adopted a national youth strategy: Algeria, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestinian Authority and United Arab Emirates. In Mauritania and Morocco, a national youth strategy has been elaborated but has not been adopted yet. Bahrain, Egypt, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia are reportedly in the process of elaborating a strategy (Figure 2.1).

Some are also sustaining efforts to renew their national youth strategies: for instance, the United Arab Emirates has a National Youth Agenda 2016-2021 in place and is currently elaborating a new one; similarly the Palestinian Authority had a NYS “Youth are our Future” 2017-2022 in place and invested efforts in reviewing, updating and extending it to 2023 in response to the COVID-19 crisis. While more MENA administrations have adopted or are in the process of elaborating integrated youth strategies at the national level, implementation challenges risk limiting their impact.

Figure 2.1. Public administrations in the MENA region with a National Youth Strategy or elaborating one

Source: OECD Youth Governance Survey, interviews and desk research (updated as of January 2022).

Algeria

In Algeria, a National Youth Plan 2020-2024 (Plan National Jeunesse 2020-2024) was elaborated by an inter-ministerial commission established in 2020 (Algérie Presse Service, 2020[17]). A government-wide action plan to support its implementation was adopted in September 2021 (Government of the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, 2021[18]).

Bahrain

Previously, Bahrain developed and adopted a National Youth Strategy (2005-2009) with the support of the UNDP (Al-Wasat, 2009[19]). Currently there is no evidence available about the elaboration of a new strategy. However, one of the objectives of Bahrain's Government Plan 2019-2022 is to "highlight the role of woman, youth and sports in all government programs and initiatives" (Government of the Kingdom of Bahrain, 2022[20]).

Egypt

In 2021, the Ministry of Youth and Sports in Egypt, in cooperation with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport, held consultations with young people across all governorates to inform the development of a National Youth Strategy for 2021-2026 (UNFPA, 2021[21]). A technical workshop with representatives of ministries, government and public agencies was held to contribute to its elaboration (State Information Service of Egypt, 2021[22]).2 The eight axes discussed for the elaboration of a NYS include technology, culture and leisure; health, economy and entrepreneurship; community development and environmental preservation; basic requirements for living; participation in public and political life (citizenship, political participation); and youth sector governance.3 At the time of writing, the NYS is still under elaboration.

Iraq

In Iraq, the National Adolescent and Youth Survey was organised in 2019 with technical support provided by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and UNICEF to inform the elaboration of a national youth strategy (UNFPA, 2020[23]). In 2021, following the participation of 33,000 Iraqis between the ages of 10 to 30 from all provinces of Iraq, the Ministry of Youth and Sports launched the cross-sectoral 2030 National Youth Vision (UNFPA, 2020[23]; UNICEF, 2021[24]). It covers 14 thematic areas, including health, culture and employment, among others (UNICEF, 2021[24]).

Jordan

In 2004, Jordan was the first country in the region to adopt a multi-year strategy focused on young people (2005-09). Due to the absence of an effective monitoring and evaluation system, the strategy was put on hold. More recently, in 2019, the Cabinet adopted the National Youth Strategy 2019-2025 (Ministry of Youth in Jordan, 2019[25]), which was launched in the presence of the Prime Minister and Minister of Youth (OECD, 2021[12]). The strategy was informed by a review of royal directives and national strategies, an evaluation of the 2004-09 strategy, international good practices, a SWOT analysis and results of a survey of Jordanian youth, conducted by the General Statistics Department in 2014 (OECD, 2021[12]). The strategy identifies seven themes, which are further expanded in the form of nine strategic objectives, each of which is linked to one of the Sustainable Development Goals (i.e. poverty reduction; good health and prosperity; good education; industry, innovation and infrastructure; reducing inequalities; peace, justice and strong institutions; entering into partnerships to achieve objectives) (OECD, 2021[12]).

Kuwait

In Kuwait, the Ministry of State for Youth Affairs prepared the first “National Framework for Youth Engagement and Empowerment” in 2012 with technical support provided by UNDP (State of Kuwait, 2013[26]). The framework was endorsed by the Council of Ministers in 2013 and adopted by the Ministry of State for Youth Affairs as a 3-year national youth strategy for 2013-16 (UNDP, 2017[27]). Since 2016, a new national youth policy had been elaborated, which was presented in early 2019 by the Minister of State for Youth Affairs to the Cabinet of Ministers (Kuwait News Agency, 2019[28]) and which, according to available information, was still operational in 2021 (The Times Kuwait Report, 2021[29]).

Lebanon

In Lebanon, the Council of Ministers endorsed the National Youth Policy in 2012, accompanied by an action plan for the Ministry of Youth and Sports (Ministry of Youth and Sports in Lebanon, 2012[30]). The document was developed by the Youth Forum for Youth Policy4, which was one of the stakeholders in the government’s “National Advice over the Youth Policy” initiative (Youth Advocacy Process; Youth Forum for Youth Policies, 2012[31]). The National Youth Policy features policy recommendation to promote active citizenship amongst young people, enhance their sense of solidarity and encourage the participation of youth organisations at the regional level. Currently the implementation status of the strategy is unclear.

Mauritania

In 2015, the Council of Ministers in Mauritania adopted the National Strategy on Youth, Sports and Leisure 2015-2020 (Strategie Nationale de la Jeunesse, Sports et Loisirs 2015-2020). Since then, a new NYS for the period 2020-2024 (Strategie Nationale de la Jeunesse 2020-2024) has been drafted, which is embedded in the more long-term NYS 2020-2030. The NYS 2020-2024 aims to empower young people to accelerate sustainable development through education and training, entrepreneurship and decent employment, increase young people’s access to public services, strengthen their representation in decision-making, promote citizenship, democracy and peace and construct youth-responsive infrastructure (social, cultural and sports facilities). At the time of writing, the strategy is being updated in collaboration with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and is projected to be submitted for adoption in early 2022.

Morocco

In Morocco, following a process of national consultations led by the Ministry of Youth and Sports, the government drafted the National Integrated Strategy on Youth 2015-2030 (Stratégie Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse 2015-2030, SNIJ) with the ambition to provide a reference framework for the co-ordination of public policies affecting young people (Ministry of Youth and Sports in Morocco, 2014[32]). While never formally adopted and now obsolete,5 it has informed subsequent work on the National Integrated Policy on Youth since 2018 (Politique Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse, PNIJ) (OECD, 2021[33]). It is composed of four axes: listening to and communicating with young people, the personal development of young people, their integration into society and strengthening young people’s access to basic services (education, training, professional integration, health, housing, mobility and entertainment) (Agence Marocaine De Presse, 2019[34]). The National Integrated Policy on Youth (Politique Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse, PNIJ) was approved by the Government Council in 2019 and is since awaiting adoption.

Palestinian Authority

The NYS “Youth are our Future”, developed by the Palestinian Authority for the 2017-2022 period, addresses the fields of training and education, social and political participation, employment and economic empowerment, health, sports and culture, and media and information technology. It builds on previous strategies that were elaborated with the support of GTZ (German Technical Cooperation) in 2006, and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in 2010 (Government of the Palestinian Authority, 2011[35]). Following a mid-term review of the current National Youth Strategy in 2019-20, and in light of the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, it was updated and extended to remain in force until 2023 (Prime Minister's Office in the Palestinian Authority, 2021[36]).

Qatar

In 2018, the Cultural Enrichment and Sports Excellence Strategy 2018-22 (CSSS) was launched in Qatar as part of its National Development Strategy 2018-22 (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics in Qatar, 2018[37]). While it does not represent a national integrated youth strategy in the narrow sense, the Cultural Enrichment and Sports Excellence Strategy sets an outcome for “empowered and qualified youth for an active role in society” and it includes targets on the development of young people’s skills, the promotion of youth-responsive programmes and the creation of effective communication channels between young people and decision-makers at all levels (Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics in Qatar, 2018[37]). Notably, the strategy makes a reference to future generations in its strategic objectives. In 2021, the Ministry of Culture and Sports in Qatar started work on a National Youth Document (Ministry of Culture and Sports in Qatar, 2021[38]).

Saudi Arabia

In 2010, the Ministry of Economy and Planning in Saudi Arabia, with the support of the UNDP, elaborated the Saudi National Youth Strategy (UNDP, 2013[39]). The strategy included eight axes: education, training, employment, health, culture, media, communications and information technology (Asharq Al-Awsat, 2014[40]). The Shura Council adopted the strategy in 2014. Currently there is no evidence available about the implementation of the strategy.

Tunisia

In Tunisia, the government has been working on the elaboration of a NYS since 2013. In 2016, the ministry in charge of youth affairs organised a societal dialogue throughout the country, under the auspices of the Presidency of the Republic.6 While the idea of adopting a NYS did not materialise, the outputs of the 2016 national dialogue were instead used by the Ministry of Youth and Sports for the elaboration of the Sectoral Vision on Youth 2018-2020 (Vision Sectorielle de la Jeunesse 2018-2020) (Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports in Tunisia, 2018[41]). With the launch of a new national dialogue in January 2019, organised by the National Observatory for Youth (Observatoire Nationale de la Jeunesse, ONJ), the prospect to work towards a national youth strategy gained new momentum. The national dialogue surveyed 10,000 young people from different backgrounds on matters related to employment, societal education, peace and security, new technologies, information and communication, risky behaviour, and immigration, the results of which were published in a report per theme (OECD, 2021[13]). However, at the time of writing, a NYS has not yet been drafted. Instead, since 2021, the Ministry of Youth and Sports has worked on an annual national youth action plan that would build on the Sectoral Vision on Youth 2018-2020 in support of implementing Tunisia’s National Development Plan 2021-2025 (Plan de Développement National 2021-2025).

United Arab Emirates

In 2016, the United Arab Emirates launched its first NYS, the National Youth Agenda 2016-2021. The National Youth Agenda 2016-2021 was elaborated with evidence gathered from multiple sources, including leadership meetings, feedback provided by young people via local youth councils, youth circles, a youth survey, social media, and an in-person youth retreat, a baseline review of existing youth statistics and national strategies that concern young people, as well as international good practices. In the process of determining the strategic priorities for the youth sector, the key transitions that young people in the United Arab Emirates go through in their transition to an autonomous life were examined. Five pivotal phases were identified and, reflecting these transitions, the final National Youth Agenda 2016-2021 defines five corresponding objectives for youth, ranging from engaging in policy-making and exercising citizenship to education and continuous learning, employment and entrepreneurship, health and safety, growing a family, and planning for the future (Government of the United Arab Emirates, 2016[42]). A second iteration of the National Youth Agenda is being elaborated with the launch expected to take place in 2022.

Benchmarking national youth strategies against the OECD Assessment Framework for National Youth Strategies

Adopting a national youth strategy alone is not sufficient. Creating a vision for young people over a multi-year horizon, a strategy is expected to improve policy coherence and facilitate inter-ministerial and multi-stakeholder co-ordination based on clearly assigned mandates. By integrating young people in all stages of the strategy (from formulation to implementation and monitoring), governments can promote their ownership in the definition of priorities and ensure that subsequent programmes and services are more responsive to their demands. Moreover, robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks are critical to keep track of the implementation and to assess regularly whether the strategy delivers the intended results or whether adjustments might be necessary. The availability of age-disaggregated data across the thematic areas covered by the strategy is another key determinant of its success.

A number of international and regional frameworks exist to guide policy makers in preparing national youth strategies, such as the African Youth Charter, elaborated by the African Union Commission (2006[43]).7 However, these frameworks lack measurable standards and indicators.8 The OECD Assessment Framework for National Youth Strategies, illustrated in Table 2.1, addresses this gap by identifying eight measurable principles of good governance to guide the elaboration of national youth strategies: they shall be 1) supported by high-level political commitment, 2) evidence-based, 3) participatory, 4) resourced, 5) transparent and accessible, 6) monitored, evaluated and accountable, 7) cross-sectoral and 8) gender-responsive (see Table 2.1).

The framework draws on existing guidelines and OECD standards, including the OECD Recommendations on Open Government (OECD, 2017[44]), Gender Equality in Public Life (OECD, 2016[45]), Budgetary Governance (OECD, 2015[46]), Policy Coherence for Sustainable Development (OECD, 2019[47]), the OECD Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance (OECD, 2020[48]) as well as the OECD Recommendation on Creating Better Opportunities for Young People (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. OECD Recommendation on Creating Better Opportunities for Young People

Adopted by its 38 Members in June 2022 at the Ministerial Council Meeting, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Creating Better Opportunities for Young People promotes government-wide strategies and sets out a range of policy principles to improve youth measures and outcomes in all relevant policy areas.

The Recommendation is structured around five building blocks, recommending that Adherents should:

Ensure that young people of all backgrounds and in all circumstances acquire relevant knowledge and develop appropriate skills and competencies;

Support young people in their transition into and within the labour market, and strive to improve labour market outcomes for young people, and especially those in vulnerable and/or disadvantaged circumstances;

Promote social inclusion and youth well-being beyond economic outcomes, with measures targeted at young people in vulnerable and/or disadvantaged circumstances;

Establish the legal, institutional and administrative settings to strengthen the trust of young people of all backgrounds in government, and their relationships with public institutions; and

Reinforce administrative and technical capacities to deliver youth-responsive services and address age-based inequalities through close collaboration across all levels of government.

The Recommendation provides an international standard against which OECD Members and non-member governments can benchmark current practices to identify priority areas for reform and access international good practices.

Source: (OECD, 2022[49])

The principles are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Evidence from a correlation analysis of the results of the OECD Youth Governance Surveys in 2020 confirms that positive outcomes in one quality standard are associated with positive outcomes in others (OECD, 2020[1]). For instance, the more a strategy is transparent about the evidence it builds on and the responsibilities of different stakeholders, the more accountable it will be. OECD evidence gathered during the first and second year of the COVID-19 crisis among youth-led organisations also demonstrates that effective, inclusive and transparent governance is a key driver of trust in government among young people (OECD, 2020[2]; OECD, 2022[50]).

Table 2.1. OECD Assessment Framework of National Youth Strategies

|

Principle |

Definitions and Explanations |

|---|---|

|

Supported by political commitment |

Definition: The government’s leadership has committed to address young people’s needs. Explanation: (i) High-level statements outlining that the needs and perspectives of young people are a government priority; and (ii) youth-specific commitments covered in strategic government documents (e.g. national development strategy). |

|

Evidence-based |

Definition: all stages of youth policy development and implementation are based on reliable, relevant, independent and up-to-date data and research, in order for youth policy to reflect the needs and realities of young people from different backgrounds and circumstances. Explanation: (i) regularly-conducted research on the situation of young people; (ii) age-disaggregated data is collected by the ministry/ministries in charge of youth affairs, line ministries and independent statistics authority; and (iii) system to facilitate data/information exchange between entity in charge of youth affairs and all other stakeholders involved. |

|

Participatory |

Definition: A participatory national youth strategy engages all relevant stakeholders, at all stages of the policy cycle, from the elaboration and implementation to monitoring and evaluation. Stakeholders are youth organisations, young people, and all other organisations as well as individuals who are influencing and/or are being influenced by the policy. Particular attention is to be paid to the participation of young people in vulnerable circumstances. Explanation: (i) meaningful participation of youth organisations, youth workers and non-organised young people throughout the policy cycle; (ii) variety of tools and channels to ensure meaningful participation, such as face-to-face meetings, surveys, seminars and conferences, online consultations, and virtual meetings (webinars); and (iii) focused activities to engage young people in vulnerable circumstances. |

|

Resourced / budgeted |

Definition: Sufficient resources, both in terms of funding and human resources are available for youth organisations, structures for youth work as well as public authorities to develop, implement, monitor and evaluate the national youth strategy. Supportive measures, from training schemes to funding programmes, are made available to ensure the capacity building of various actors and structures involved in youth policy. Explanation: (i) the ministry/ministries co-ordinating the youth portfolio has/have a dedicated budget; (ii) the ministry/ministries co-ordinating the youth portfolio has/have sufficient human resources; (iii) a dedicated budget and dedicated staff is assigned to the national youth strategy; and (iv) grants and other support structures are made available by the government to youth organisations and structures for youth work. |

|

Transparent and accessible |

Definition: The national youth strategy should clearly state which government authority/authorities has/have the overall co-ordinating responsibility for its implementation. It should also be clear which ministries are responsible for the different areas that are addressed in the policy. A transparent policy should be laid out in publicly accessible documents. Explanation: (i) national youth strategy available online in an easily accessible format; (ii) the national youth strategy clearly defines responsibilities for implementation, monitoring and evaluation; (iii) clear description of roles and responsibilities within the entity/entities co-ordinating the strategy are available and easily accessible to other stakeholders (e.g. organisational chart and contact details); and (iv) results of surveys, consultations and reports are publicly available. |

|

Monitored and evaluated / accountable |

Definition: Data is collected in a continual and systematic way. The strategy is systematically and objectively assessed looking at its design, implementation and results with the aim of determining the relevance and fulfilment of objectives, effectiveness, impact and sustainability. An evaluation should provide information that is credible and useful, enabling policy makers to incorporate lessons learned into the decision–making process. Finally, the various stakeholders in the policy-making process take responsibility for their actions and can be held accountable for them. Explanation: (i) measurable objectives and targets are set; (ii) key performance indicators linked to the objectives and targets are defined; (iii) a data-collection system for key performance indicators is established; (iv) specific mechanisms exist to ensure the quality of the data collected; (v) progress reports are prepared on a regular basis; (vi) evidence produced in monitoring is used to inform decision-making; and (vii) evaluations are prepared regularly and made available publicly. |

|

Cross-sectoral / transversal |

Definition: Cross-sectoral youth strategy implies that all relevant policy areas are covered and that a co-ordination mechanism exists among different ministries, levels of government and public bodies responsible for and working on issues affecting young people. Explanation: (i) all relevant policy areas are addressed and put in relation with one another in the national youth strategy; (ii) line ministries are involved throughout the policy cycle; (iii) intra-ministerial co-ordination mechanisms are established; and (iv) mechanisms to involve local and potentially other subnational levels of government throughout the policy cycle of the strategy exist. |

|

Gender responsive |

Definition: The national youth strategy should be assessed against the specific needs of women and men from diverse backgrounds to ensure inclusive policy outcomes. Explanation: (i) explicit reference to gender equality in the strategy; (ii) availability of gender-disaggregated data; and (iii) availability of gender-specific objectives within the strategy. |

Source: OECD.

The degree to which NYS deliver on these principles varies significantly across OECD countries. In fact, as of 2020, only 20% of national youth strategies in place across OECD countries are fully participatory, budgeted, monitored and evaluated (OECD, 2020[1]). In turn, when national youth strategies are formulated without the meaningful engagement of youth stakeholders from diverse backgrounds, when they are not supported by adequate resources and when their implementation is not monitored and evaluated regularly, there is an increased risk that their implementation will fail (OECD, 2020[1]).

Based on the information provided by ministries in charge of youth affairs to the OECD Youth Governance Surveys, interviews with ministerial representatives and accompanying desk research, the following sections will benchmark the efforts of selected public administrations in the MENA region with a NYS (or in the process of elaborating/adopting one) against this assessment framework. Based on an overview of good practices across the region and OECD countries (see Box 2.2), it identifies priorities for reform.

Political commitment: a first and important condition

High-level political commitment is a first and important condition to mobilise various governmental and non-governmental stakeholders behind a joint vision for young people. Such support can help to initiate work on a cross-sectoral youth strategy, mobilise stakeholders in its implementation and raise awareness among the broader public, including civil society and media, about government action targeting young people.

High-level political commitment can be demonstrated in the form of political declarations or pledges prior to elections. To demonstrate that a NYS is aligned with the broader government agenda, explicit references to the synergies between both and to the way in which youth-specific commitments deliver on government-wide national priorities are characteristic of some strategies. In Canada, for instance, since 2015 each cabinet minister, including the minister in charge of steering youth policy, receives a mandate letter from the Prime Minister, which includes the policy objectives to be met. The mandate letters are publicly available (Prime Minister of Canada, 2021[51]). In some countries, notably Austria, Colombia, Japan and Italy, youth policy is steered by Centre of Government (CoG) institutions9 (OECD, 2020[1]) to encourage inter-ministerial coordination based on a cross-sectoral approach and to ensure high visibility. Findings from 2020 indicate that OECD countries in which the youth portfolio is managed and coordinated by Centre of Government institutions neither observe a lack of political will nor an absence of political leadership as a challenge for co-ordination on the design and delivery of youth policy and services (OECD, 2020[1]). Most frequently, formal responsibility for youth affairs in OECD countries is organised in a unit or department inside a ministry with broader responsibilities, such as education or social development (OECD, 2018[52]). In the MENA administrations covered in this report, the youth portfolio is most commonly assigned to a ministry of youth with combined portfolios (see Chapter 3).

Political commitment to improve young people’s situation based on an integrated strategy across the MENA region has varied across countries and time. In Jordan, for instance, the King referred to the young generation as the “greatest asset and hope for the future” in 2000, underlining the need to “tap into our young people’s intellectual, creative, and reproductive potential in order for Jordan to keep up with new developments in global scientific, economic and social factors” (UNDP, 2000[53]). The call to empower young people by developing the state administration and enhancing the rule of law was reiterated in discussion papers issued by the King. In 2016, the Higher Council for Youth was transformed into the Ministry of Youth, which marked an important development to reflect this commitment in the institutional architecture of the government (OECD, 2021[12]). In the Palestinian Authority, a presidential order enabled the transition of the Ministry of Youth and Sports into the Higher Council of Youth and Sports to expand services to young people living in the diaspora (Higher Council for Youth and Sports in the Palestinian Authority, 2017[54]).

In the United Arab Emirates, in 2016, the creation of the position of Minister of State for Youth Affairs and the appointment of one of the world’s youngest ministers to the position at age 22 reflected the commitment by the political leadership to renew its focus on improving the opportunities for young people (Government of the United Arab Emirates, 2021[55]). In the same year, the United Arab Emirates published its first national youth strategy, the National Youth Agenda 2016-2021. In the elaboration of the strategy, several consultations with young people were launched by the Vice President and the Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates and Ruler of Dubai (Government of the United Arab Emirates, 2016[42]). In Egypt, 2016 was declared the “Year of Youth” by the President (State Information Service of Egypt, 2020[56]). Since 2016, National Youth Conferences have been organised and in 2021, the Ministry of Youth and Sports started work on the National Youth Strategy 2021-2026.

Political commitment is an important building block for the successful design and implementation of a NYS. However, it can vary due to emerging challenges that are perceived to be more imminent and a subsequent change in political priorities or different perspectives and interests on the approach to follow. For instance, in Morocco, despite the support by the King for “the elaboration of a new integrated policy dedicated to young people” (Government of the Kingdom of Morocco, 2017[57]) in 2017, the National Integrated Policy on Youth (Politique Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse, PNIJ) has not been adopted. Similarly, despite strong political commitment after the 2011 revolution, the 2016 Carthage Agreement (Accord de Carthage) and its commitments focused on engaging young people in policymaking as well as the attention to the needs of young people in the Development Plan 2016-2020 (Plan de Développement 2016-2020), Tunisia is yet to adopt a NYS.

Evidence-based approaches: Age-disaggregated data in key sectors is lacking

The use of evidence in policymaking can improve the design, implementation and evaluation of public policies (OECD, 2020[48]). An evidence-based youth strategy uses reliable, relevant, independent and up-to-date information and data throughout this cycle. It identifies young people’s needs and perspectives, presents age-disaggregated information in terms of young people’s access to and quality of public services (e.g. education, employment, health, housing, etc.) and thus helps to ensure that public programmes and resources will be allocated to effective use. To overcome silo-based approaches, a system to facilitate data and information exchange between different stakeholders, both at the central and subnational levels as well as between them, is crucial for more integrated and coordinated approaches.

Young people are a heterogeneous group who live in highly different circumstances, depending on their socio-economic status and geographic area, age, gender, race and ethnicity, indigeneity, migrant status, (dis)ability status and others young people associate with, and their intersections. Inequalities that correlate with certain circumstances and backgrounds tend to accumulate over the life cycle (OECD, 2017[58]). Therefore, beyond being disaggregated by age, the evidence to inform national youth strategies should be, whenever possible, disaggregated by other characteristics too (OECD, 2021[12]). Careful consideration should also be given to the collection and use of such data in areas beyond education and employment with an impact on the well-being and opportunities of young people. For instance, income and wealth, work and job quality, housing, health, knowledge and skills, environmental quality, subjective well-being, safety, work-life-balance, social connections and civil engagement are just some of the policy areas the OECD Well-being Framework identifies as critical in this regard.10

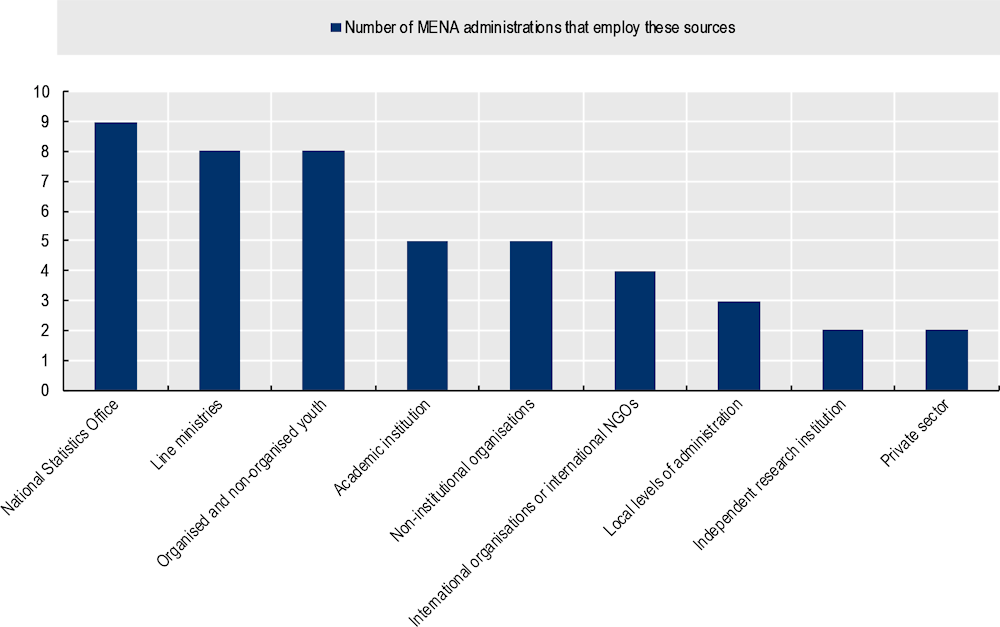

Among the MENA administrations that have designed or adopted a national youth strategy (Figure 2.2), nearly all report to have used evidence from the National Statistics Department (or equivalent) during the elaboration of their strategy, with the exception of Morocco. All, with the exception of Jordan and the Palestinian Authority, report to have used evidence gathered by line ministries, and, other than Morocco and Saudi Arabia, all administrations report to have used evidence gathered from organised and non-organised young people. Some have further collected evidence from academic institutions (Lebanon, Mauritania, Palestinian Authority, Qatar and Tunisia), non-governmental organisations (Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Qatar and Tunisia) and inter-governmental organisations or international NGOs (Egypt, Mauritania, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates). Notably, only Mauritania, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates report to have used data from subnational levels of government and only Lebanon and Tunisia report to have used evidence from independent research institutes. Lebanon and Qatar also stress they have compiled evidence from the private sector.

Figure 2.2. Sources of evidence used by selected MENA administrations in the elaboration of their NYS

Note: The chart builds on data from Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Palestinian Authority, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and United Arab Emirates.

Source: OECD Youth Governance Survey and desk research (updated in January 2022).

The non-participation of the subnational level in the collection and use of evidence in many public administrations covered in this report is striking. It points to a disconnect between public authorities working on either side, the lack of effective channels of information and communication and limited capacities in many subnational contexts to collect such data. This results in a significant risk that young people’s unequal access to public services and broader opportunities in different regions are not addressed.

A closer analysis of the situation in Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia reveals a number of common challenges for evidence-based youth policy making. In Jordan, for instance, the National Youth Strategy 2019-2025 presents data on the demographic situation, youth unemployment levels as well as the physical infrastructure of youth spaces managed by the Ministry of Youth (e.g. youth centres, youth clubs). In turn, there is a significant lack of evidence to underpin the measures listed under the seven thematic and nine strategic objectives. The lack of disaggregated evidence across key sectors is indeed acknowledged in a SWOT analysis that is integrated into the strategy (Ministry of Youth in Jordan, 2019[25]; OECD, 2021[12]). In Morocco, following the adoption of the 2011 Constitution, national consultations were held in 2012 with the participation of more than 27,000 young people and were leveraged in the elaboration of the National Integrated Strategy on Youth 2015-2030 (Stratégie Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse 2015-2030, SNIJ), which is now obsolete, and informed the later elaboration of the National Integrated Policy on Youth (Politique Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse, PNIJ) in 2018, which is awaiting adoption (OECD, 2021[33]). For example, the region of Marrakech-Safi is planning to create a local observatory for the evaluation of the policy areas under its competency, as well as its own regional monitoring and performance indicators (OECD, 2021[33]). Similarly, in Tunisia, according to the government, 40,000 people participated in the national dialogue on youth rolled out in 2016 (Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports in Tunisia, 2018[41]), which fed into the creation of a database on employment, health and other areas benefiting from 35,000 contributions. A first diagnostic of the existing situation for young people was also informed by a survey among 1,200 households including parents and young people aged 18-30 and a survey among 10,000 young people, conducted by the National Observatory for Youth (Observatoire Nationale de la Jeunesse, ONJ) (OECD, 2021[13]). However, as an NYS is being elaborated in Morocco and awaiting adoption in Tunisia, updating the data collected in 2012 and 2016 respectively will be crucial to ensure up-to-date evidence so that the NYS can reflect the current needs and priorities of Moroccan and Tunisian youth.

The challenges that MENA administrations are facing are in fact similar to those many OECD countries report. In a 2020 survey across ministries in charge of youth affairs in OECD countries, 88% reported that the design of their national youth strategy was informed by evidence (OECD, 2020[1]). However, only half of these ministries reported that they gathered age-disaggregated data and information and, among this group, more than two-thirds reported that they found it difficult to collect such data in specific areas (OECD, 2020[1]). Box 2.4 presents the examples from France, Sweden and Canada to invest in measures and institutions for evidence-based approaches to youth policy design and implementation.

Box 2.4. Age-disaggregated evidence in OECD countries

France

In France, the Research Centre for the Study and Observation of Living Conditions (Centre de Recherche pour l'Étude et l'Observation des Conditions de Vie, CRÉDOC) compiles and makes age-disaggregated data available to policymakers. The CRÉDOC has published surveys on the living conditions and aspirations of French people since 1978. In early 2018, it published the third edition of the DJEPVA Barometer, a national survey of 4,500 young people aged 18-30.

Sweden

The Swedish Parliament adopted its current youth policy bill With youth in focus: a policy for good living conditions, power and influence in 2014. The Swedish Agency for Youth and Civil Society (MUCF) is responsible for ensuring that the objectives of the youth policy are achieved. As part of its ongoing effort to monitor the implementation of the youth policy, the MUCF continuously compiles and publishes available age-disaggregated data per indicator on the Ung Idag website (http://www.ungidag.se/). It covers six key sectors of interest for youth: work and housing; economic and social vulnerability; physical and mental health; influence and representation; culture and leisure; and training.

Canada

Recognising the varied impacts of COVID-19 pandemic challenges across demographic groups, the Canadian government will allocate $172 million CAD over five years to Statistics Canada. This funding will support the implementation of a new Disaggregated Data Action Plan to support evidence-based decision-making across priority areas including health, quality of life, the environment, justice, business and the economy by taking into account intergenerational justice considerations and the needs of diverse populations.

Beyond the usual suspects: Involving young people and youth organisations in strategy design

A participatory national youth strategy involves all relevant youth stakeholders, at all stages of the policy cycle, from creation and implementation to monitoring and evaluation. Stakeholders can include youth organisations, young people, and all other organisations as well as individuals who are influencing and/or are being influenced by the strategy. As further explored in Chapter 4, involving young people and youth organisations requires more broadly an enabling environment where civic space is protected and promoted.

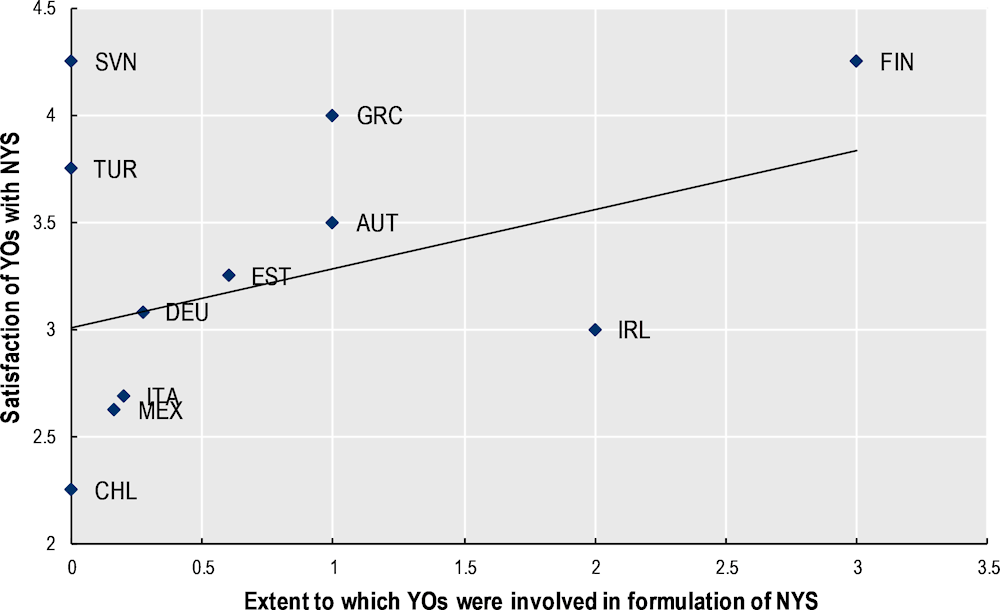

Meaningful engagement of a diverse group of stakeholders enables policymakers to identify their needs and deliver more responsive policies and services. The OECD Recommendation on Open Government emphasises that stakeholder participation increases government inclusiveness and accountability, and calls on governments to “grant all stakeholders equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted and actively engage them in all phases of the policy-cycle and service design and delivery” taking specific efforts to reach to the most vulnerable, underrepresented or marginalised groups in society (OECD, 2017[44]). OECD findings indeed indicate that investments into meaningful youth participation in the policy cycle pay off (OECD, 2020[1]). Figure 2.3 illustrates that youth organisations in OECD countries expressed higher satisfaction with the final national youth strategy in their country when they were involved throughout the definition, drafting and review of the thematic areas of the draft strategy (OECD, 2020[1]). To promote meaningful youth participation in public decision-making and spaces for intergenerational dialogue at all levels, with targeted measures to engage disadvantaged and under-represented groups for more responsive, inclusive and accountable policy outcomes, the OECD Recommendation on Creating Better Opportunities for Young People recommends exploring innovative methods to communicate and engage with diverse organised and non-organised groups of young people, such as through representative deliberative processes and digital government tools (OECD, 2022[49]).

The COVID-19 crisis has brought the challenge of engaging young people from different backgrounds to the forefront. Only 15% of OECD-based youth organisations felt that their government considered the views of young people when they adopted lockdown and confinement measures (OECD, 2022[50]). Box 2.5 outlines examples of government efforts to involve young people in policymaking in the design of national youth strategies and the adoption of measures to respond to and recover from COVID-19.

Figure 2.3. When youth were involved in strategy design, they were more satisfied with results

Note: Correlation coefficient: 0.33; p-value: 0.29. The independent variable is the share of youth organisations (YOs) in each country that indicated to have been consulted to define, draft and review the thematic areas of the National Youth Strategy. The dependent variable is the mean of means of satisfaction expressed by youth organisations with the areas and objectives of the National Youth Strategy.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1])

To ensure greater diversity of views and perspectives, beyond those by youth organisations that may often attract young people from similar backgrounds, involving non-organised groups of young people is crucial. Yet, 4 in 10 ministries in charge of youth affairs in OECD countries did not consult non-organised groups of young people in the preparation of their NYS (OECD, 2020[1]).

Box 2.5. Participatory approaches in youth policymaking in selected OECD countries

The Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy in New Zealand

The Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy in New Zealand benefited from the contributions of 10,000 New Zealanders, including 6,000 children and young people. The Government used a wide range of mechanisms, including face-to-face interviews, focus groups, workshops, academic forums, surveys and a “send a post card to the Prime Minister” initiative. The inclusion of children and young people from vulnerable groups, especially young Māori and other pacific young people as well as disabled youth, young women, refugees or children in care of the state, was a priority. The government also consulted a reference group, made up of child and youth representatives, including non-governmental organisations and academics, and published reports online to report back on the feedback received.

Special Youth Rapporteurs in Japan

The Japanese Cabinet Office appoints students as “Special Youth Rapporteurs” to inform government planning, legislation and regulations related to childhood and youth. The Special Youth Rapporteurs are asked to give their opinion on government thematic priorities, which are selected by the Cabinet Office. Their inputs are then shared across relevant ministries and government agencies and are published online on the website of the Cabinet Office.

Participation of non-organised young people in Mexico

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, in Mexico, the Institute of Youth (IMJUVE), the Ministry of Health and the Population Council surveyed more than 50,000 young people in the areas of education, employment, health, violence and resilience. The evidence gathered was used to create the VoCEs-19 report, which has informed the design, implementation, and analysis of public policies at a sectoral level that are responsive to social sensitivity and the needs of young people. A second survey was planned between November 2021 and February 2022 to identify new trends and needs.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2022[50])

Across the MENA region, according to the OECD survey results, Egypt, Lebanon, Mauritania, the Palestinian Authority, Qatar, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates involved youth organisations and non-organised young people when elaborating their national youth strategies. All except Lebanon indicate that youth workers were also consulted. However, as Chapter 4 will discuss further, the concept of youth work across the MENA region is subject to competing definitions and youth work practice often suffers from limited financial resources and well-skilled trainers.

In turn, across many public administrations in the region, work on the youth strategy was initiated or accompanied by active youth associations. In Lebanon, for instance, the preparatory work for the national youth strategy was initiated in 2000 by a group of youth associations in collaboration with the Lebanese Ministry of Youth and Sports and a United National Youth Task Force. In thematic working groups, these stakeholders prepared a list of recommendations that was submitted to the Ministry of Youth and Sports and fed into the National Youth Policy, which was approved by the Lebanese Council of Ministers in 2012 (Ministry of Youth and Sports in Lebanon, 2012[30]).

In the Palestinian Authority, workshops were run to involve young people (as well as other stakeholders) in preparation for the National Youth Strategy 2017-2022. These workshops were conducted in different areas and in different formats involving young people in the Gaza Strip and in the West Bank as well as targeting young Palestinian refugees. Young people were also consulted as part of the mid-term review of the strategy and their inputs were used to revise it.

In the United Arab Emirates, young people were involved in the elaboration of the National Youth Agenda 2016-2021 through various channels, including through local youth councils, youth circles and a youth retreat. Youth circles were organised across the United Arab Emirates to bring together young people from various backgrounds and each youth circle sought to answer one central question through discussion and recommendations. The two-day youth retreat brought together young people alongside several Ministers. From August to September 2016, an online survey collected responses from Emirati youth and a federal-wide online campaign (#TheNationalDialogueOnYouth) collected input from young people through social media (Government of the United Arab Emirates, 2016[42]).

In Egypt, the elaboration process of the National Youth Strategy 2021-2026 is currently underway. Youth consultations have been reportedly held across all governorates. In addition to hosting youth consultations, the government sought the opinions of young people through discussions in youth centres and through an online survey (Mahmoud, 2021[60]).

In elaborating a NYS, the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports in Tunisia organised a national dialogue and surveyed households between October and December 2016. The national dialogue process culminated in a National Youth Conference (Conférence Nationale de la Jeunesse), organised with participants from associations, NGOs, political parties, young members of parliament, and international partners and organisations (Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports in Tunisia, 2018[41]). Another national dialogue was organised in January 2019 by the National Observatory for Youth (Observatoire Nationale de la Jeunesse, ONJ) (OECD, 2021[13]).

Following the adoption of its 2011 Constitution, the Moroccan government organised national consultations in 2012 with young people in the formulation of the National Integrated Strategy on Youth (Stratégie Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse, SNIJ). Although the National Integrated Strategy on Youth and its action plan are today suspended, the national consultations laid the foundation for and informed the work on the National Integrated Policy on Youth (Politique Nationale Intégrée de la Jeunesse, PNIJ) (OECD, 2021[33]).

In Jordan, young people were involved in the elaboration of the National Youth Strategy 2019-2025 through “tick-the-box” opinion polls and focus groups meetings in 2017 on the main thematic pillars of the strategy. (OECD, 2021[12]).

In Qatar, youth stakeholders were reportedly involved in the formulation of the Cultural Enrichment and Sports Excellence Strategy 2018-2022 through workshops, focus groups and coordination meetings. In 2021, the Ministry of Culture and Sports started to work on a Qatar National Youth Document and an online youth survey was conducted involving young people on the topic of health, education, work, social media, full and active participation, and environment (Ministry of Culture and Sports in Qatar, 2021[38]).

In Mauritania, national and regional consultation days were organised to consult youth organisations and non-organised young people for the elaboration of the National Strategy on Youth, Sports and Leisure 2015-2020 (Strategie Nationale de la Jeunesse, Sports et Loisirs 2015-2020).

Targeted efforts to involve young people in vulnerable circumstances

Young people in vulnerable circumstances, such as those living in poor households, remote conditions and other circumstances that put them at higher risk of exclusion, should receive particular attention to avoid that inequalities at young age compound over their life cycle (OECD, 2021[12]). For example, following consultations with young people with disabilities, Greece set specific objectives and monitoring indicators for this group within its Youth ’17-’27: Strategic Framework for the Empowerment of Youth (Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs in Greece, 2018[61]). However, findings from across OECD countries indicate that a systematic approach to involving young people at risk of social and economic exclusion is often lacking. While 84% of NYS across OECD countries address the social inclusion of vulnerable groups as a topic, only one-third of countries conducted separate consultations with groups considered vulnerable and marginalised groups (OECD, 2020[1]).

Across the MENA administrations covered in this report, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, the Palestinian Authority, Qatar, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates report to have included young people from vulnerable circumstances in the formulation of their national youth strategy such as young women, young people from rural areas, youth lacking basic education, and young people not in education, employment or training (NEET). Tunisia set an interesting example by involving young prisoners. Following the inclusion of young people in vulnerable circumstances in the formulation of a national youth strategy, governments should ensure a systematic approach is in place to further involve young people.

The channels used to involve young people in vulnerable circumstances varies widely. Qatar reports to have organised specific focus groups and workshops in youth centres, as well as online surveys. In the United Arab Emirates, some of the Youth Circles to inform the National Youth Agenda 2016-21 were targeted at including young women, young people from rural backgrounds, youth from religious or ethnic minorities and young people with disabilities. The Palestinian Authority reports to have run workshops with young refugees in Lebanon as well as workshops targeted to young people from “Kaabneh”, a Bedouin tribe. In Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania and Tunisia marginalised groups responded to surveys and participated discussion fora conducted for consulting youth more broadly.

Limited resources put implementation at risk

The effective implementation of a NYS relies on adequate financial and human resources. Given the cross-sectoral nature of youth policy and that resources will need to be mobilised within and across different ministries, a coordinated approach is critical. Yet, across OECD countries with a strategy in place, only 17 of 25 are underpinned by dedicated funding (OECD, 2020[1]).

In the MENA region, available evidence from the OECD Youth Governance Survey suggest that the lack or absence of sufficient funding to implement the NYS is a common challenge across almost all public administrations. For instance, Lebanon has not allocated dedicated resources for the implementation of the national youth strategy. In Mauritania, the implementation of the youth strategy will be financed primarily by the government entity in charge of youth affairs, however, the strategy itself does not clarify the resources that will be allocated for this purpose. Where a dedicated budget has been allocated, such as in the Palestinian Authority (30,000 USD), limited funding poses a challenge. In Qatar, government authorities expected that 1,200,000 Qatari Riyal (around 329,580 USD as of May 2022) would be dedicated to the implementation of the Cultural Enrichment and Sports Excellence Strategy 2018-2022.

In Jordan, 500,000 Jordanian Dinar (around 705,228 USD as of May 2022) were allocated as part of the budget of the Ministry of Youth for strategy implementation. The ministry self-identified the lack of adequate financial resources as a key challenge in a SWOT analysis that accompanies its strategy. At least eight line ministries in Jordan are mentioned as implementation partners or leads within the national youth strategy however, it is unclear if they have mobilised their own financial resources to implement these commitments (Ministry of Youth in Jordan, 2019[25]).

In Jordan and many governments across the region, sustainable funding for the implementation of the NYS is a key concern, even more so in the absence of support provided by national and international partners to cover funding gaps (Ministry of Youth in Jordan, 2019[25]). Moreover, information about the public resources allocated to the implementation of youth strategies and youth policy more generally is not easily accessible. This is a common challenge across the OECD, with such information not being available in 11 out of 17 countries responding to the OECD survey.

Transparency and accessibility of national youth strategies remain limited

Strategies need to be transparent and easily accessible to governmental and non-governmental stakeholders to facilitate coordination, allow for the exercise of public scrutiny and hence strengthen accountability. Transparency and accessibility are also important principles to guide public communication efforts by governments about implementation progress and opportunities for young people and their organisations to contribute to it.

All OECD countries that have a NYS in place make it available online (OECD, 2020[1]). This is the case for most MENA administrations too. For instance, the strategies of Jordan11, Lebanon,12 the Palestinian Authority13 and the United Arab Emirates are available online.14 At the same time, , in some cases, information about the roles and responsibilities within the entity in charge of youth affairs as well as other stakeholders in implementing them is less readily available online or not frequently updated.

Overall, information related to implementation progress and monitoring results is scarce. Among OECD countries with a NYS, 88% publish monitoring and evaluation reports and results online (OECD, 2020[1]), in particular via the ministry/government website (60%). However, only 6% of the ministries in OECD countries report using social media to disseminate such information, which appears to be a missed opportunity given that young people are very active on these platforms (OECD, 2020[1]).

Across the MENA region, only few administrations intend to publish the results of their monitoring and evaluation activities according to the survey results. This does not only present a risk to the transparency and accountability of youth strategies, it also risks undermining efforts to rebuild and retain a stronger relationship between public institutions and young people (OECD, 2020[1]).

Monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are oftentimes lacking

The systematic monitoring of the implementation of NYS and the evaluation of their outputs, outcomes and impact contributes to ensuring that they are responsive to young people’s needs and changing circumstances, and ultimately deliver value for money. For instance, in the event of an external shock, such as the COVID-19 crisis, an evaluation of the impact so far and new measures to be taken in light of the next context, can be instrumental to increase the responsiveness of programmes and the legitimacy for the use of public resources.

To put in place an effective monitoring and evaluation framework, policy makers should set measurable targets and objectives, identify key performance indicators (KPIs) linked to targets and objectives, and establish a system to collect and share data among all relevant stakeholders involved. The system should be underpinned by adequate financial capacities and run by officials with the right skills set and competencies.

Figure 2.4 illustrates various mechanisms put in place by OECD countries to monitor and evaluate their national youth strategies. In OECD countries, around two-thirds of national youth strategies set measurable objectives and targets, as well as mandate the preparation of periodic progress reports (e.g. at least annually) to feed information from the monitoring and evaluation exercise into the policymaking cycle. One in two national youth strategies identifies KPIs linked to objectives and targets and is embedded into a data-collection system to track progress. On the other hand, one in four national youth strategies is monitored and evaluated on an ad hoc basis and only 8% have specific mechanisms in place to ensure the quality of evidence (OECD, 2020[1]).

Figure 2.4. Monitoring and evaluation of national youth strategies, OECD countries

Only a few administrations in the MENA region report to monitor and evaluate their youth strategies.

In Jordan, each project within the National Youth Strategy 2019-25 is linked to a strategic, sectorial and national objective and theme. It is also linked to key performance indicators, mostly at the level of outputs (e.g. number of trainings), and a corresponding implementation period. According to the Ministry of Youth, while a detailed implementation report was expected to be prepared for 2020, none of the implementing partners had submitted their reports as of May 2021 due to the COVID-19 crisis (OECD, 2021[12]).

As of 2022, only Mauritania, the Palestinian Authority and the United Arab Emirates appear to have evaluated the implementation of their national youth strategies. In Mauritania, the implementation of the National Strategy on Youth, Sports and Leisure (Strategie Nationale de la Jeunesse, Sports et Loisirs) was evaluated against indicators listed in the Operational Action Plan, which are linked to the strategy’s objectives. This evaluation also informed and fed into Mauritania’s forthcoming new strategy, which has adapted the monitoring and evaluation plan. In the Palestinian Authority, the mid-term review of the NYS informed the decision to extend the NYS to 2023 and programmatic changes in response to the COVID-19 crisis. In the United Arab Emirates, an internal evaluation of the latest National Youth Agenda is reported to inform the elaboration of the new NYS.

In Qatar, a higher committee on supervision and follow-up was assigned the responsibility of monitoring and evaluating the activities under the Cultural Enrichment and Sports Excellence Strategy 2018-2022 (CSSS), including through intermediary and final evaluations.

Monitoring and evaluation activities can benefit from the inputs of a number of stakeholders, including other line ministries, sub-national authorities, independent state institutions (e.g. independent commissions, Supreme Audit Institutions, Ombudsperson), the legislature and young people. Enabling stakeholders to monitor and evaluate the NYS increases its transparency and accountability and can be an important driver of young people’s satisfaction with public policy and service delivery (OECD, 2020[1]). Box 2.6 illustrates approaches adopted by selected OECD countries to involve independent institutions, parliament and young people in monitoring and evaluation efforts.

Box 2.6. Involving stakeholders in monitoring and evaluating youth policy and programmes in OECD countries

Slovak Republic

In the Slovak Republic, consultations at the national and the regional level with the participation of young people, public officials and non-governmental organisations form the backbone of monitoring and evaluation activities, leading to the elaboration of mid-term and final “youth reports” on the progress and impact of the national youth strategy. M&E activities benefitted from the inputs of a variety of ministries, notably through the inter-ministerial working group on youth policy and the Committee for Children and Youth.

Finland

In Finland, the National Audit Office examined the results and effectiveness of youth workshops in 2013-2016, and the allocation of the resources and cost efficiency of youth work in 2014-2017.

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica, the results of the evaluation exercise are presented to the National Youth Assembly, which is tasked with approving the National Youth Strategy. The Assembly is composed of representatives of different civil society organisations, universities, political parties and ethnic groups and meets on a regular basis.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]; Government of Finland, 2020[62]).

NYS are cross-sectoral and hence require strong coordination

Youth as a policy area cuts across numerous ministerial portfolios from education and sports to employment, health, housing, transportation, civic and political participation and many others. At the same time, outcomes in one area can be closely linked and influence the outcomes for young people in other areas. . For example, the level and quality of education is correlated with the job and future career and income prospects, and it can affect young people’s awareness of health-related issues. Similarly, access to sport, leisure and public spaces dedicated to young people are important to form social connections as well as for their physical and mental health.

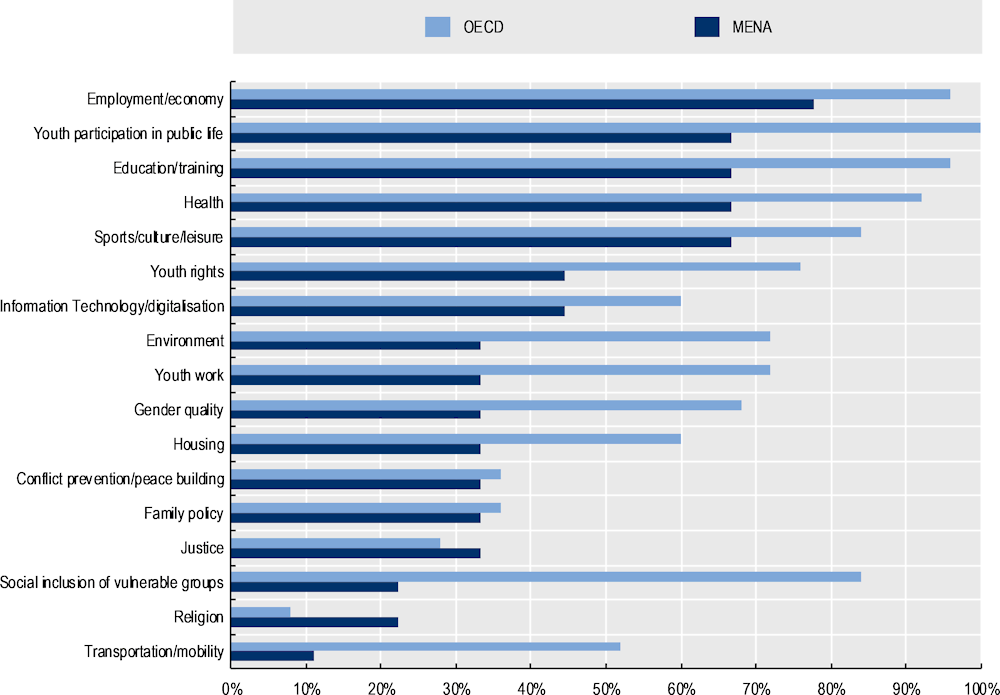

Although the thematic areas vary across governments, existing NYS in the MENA region cover similar topics as NYS adopted by OECD countries (see Figure 2.5). All OECD countries with a NYS in place cover "youth participation in public life", 96% feature commitments in the area of "employment/economy" and "education/training", 92% for "health" and 84% for the “social inclusion of vulnerable groups“, and “sports/culture/leisure“. In the MENA region, 78% feature specific measures and programmes in the area of “employment/economy” and 67% for “youth participation in public life”, “education/training”, “health” and “sports/culture/leisure”. Compared to the strategies in OECD governments, those across MENA administrations are less vocal about the social inclusion of vulnerable groups, youth rights, transportation and mental health.

Interestingly, beyond an outline of thematic priorities and measures to address them, the strategies of Jordan, Mauritania and Qatar also point to the need to strengthen the governance arrangements for their successful implementation. For instance, the youth strategy in Jordan highlights the importance of cross-sector collaboration and the strategies of Qatar and Mauritania include objectives on strengthening institutional capacities for planning, monitoring and evaluation (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Thematic areas addressed in national youth strategies