This chapter analyses the formal organisation of youth affairs across public administrations in the Middle East and North Africa with a focus on the administrative and technical capacities within the ministries responsible for youth affairs. It finds that limited institutional and administrative capacities of these entities present a key challenge for more integrated and inclusive measures targeting young people. It also points to co-ordination challenges between different ministries and with non-institutional stakeholders. To support efforts to mainstream young people’s perspectives and needs across all policy areas, the chapter presents practices from selected OECD and MENA administrations in the collection and use of age-disaggregated data and the application of public management tools in rulemaking and public budgeting.

Youth at the Centre of Government Action

3. Ensuring public administrations deliver targeted policies and services for young people

Abstract

Chapter 2 discussed the efforts by public administrations across the MENA region to deliver more integrated youth policies and services by adopting national youth strategies. This chapter will analyse the administrative and technical capacities as well as co-ordination measures needed to implement these strategies.

It will analyse the formal organisation of youth affairs across public administrations in the MENA region, the resources dedicated to the lead ministry in charge of youth affairs to deliver on its mandate and the co-ordination mechanisms established between all relevant stakeholders. It also highlights innovative public management tools that MENA administrations could adopt to mainstream the perspectives of young people more systematically in policy making.

The organisation of youth affairs in government

Institutional arrangements to assign formal authority for youth affairs vary widely across both OECD governments and MENA administrations.

Across OECD countries, the youth portfolio is most commonly located within the Ministry of Education (8 of 32 countries), followed by a dedicated Ministry of Youth with combined portfolios (i.e. education, sports, family affairs, senior citizens, women and children) (7 of 32 countries) (OECD, 2020[1]). The Centre of Government (CoG)1 leads the youth portfolio in Austria, Colombia, Japan and Italy. In Denmark, there is no single national authority responsible for youth affairs.

Combining the youth portfolio with other ones is the most common arrangement of youth affairs across MENA administrations as well (see Table 3.1), most commonly combining the “youth” and “sports” portfolios. This is the case in Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority, Qatar and Tunisia. Historically, the focus on “sport” has been dominant in many of these entities but with the renewed efforts to elaborate national youth strategies, new ministries, departments and units for youth policy and programming were created. For instance, in the United Arab Emirates, the youth portfolio was located within the Ministry of Community Development until the 1990s. In the early 2000s, the General Authority of Youth and Sports was established to be in charge of youth and sports affairs. In 2016, with increased high-level political commitment to the youth portfolio and the development of a national youth strategy, the first Minister of State for Youth Affairs was appointed, along with the establishment of a separate Ministry of Youth Affairs and its executive arm, the Federal Youth Authority. Since 2021, the youth portfolio was joined in the Ministry of Culture and Youth, maintaining a separate Minister of State for Youth Affairs who represents the portfolio in the Cabinet.

Moreover, a number of ministries other than those officially in charge of youth affairs might have important stakes and programmes in the field of youth policy. For instance, in Egypt, while the Ministry of Youth and Sports is responsible for elaborating and implementing the National Youth Strategy and for adopting youth policies and managing youth centres, the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development has important advisory responsibilities and allocates financial resources to the other ministries based on the government's priorities. Furthermore, the Ministry benefits from the work of the National Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development, its training arm, which designs and delivers programmes and capacity-building for young people.

Table 3.1. Bodies with formal responsibility for youth affairs

|

Economy |

Ministry |

Entity within the Ministry |

|---|---|---|

|

Algeria |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

General Directorate for Youth Affairs |

|

Bahrain |

Ministry of Youth and Sports Affairs |

Youth Empowerment Directorate |

|

Egypt |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

Youth Directorate |

|

Iraq |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

Youth, Culture and Art Department |

|

Jordan |

Ministry of Youth |

General Directorate for Youth Affairs |

|

Kuwait |

Ministry of Youth Affairs Office |

N/A |

|

Lebanon |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

Youth Department |

|

Mauritania |

Ministry of Culture, Youth, Sports and Relations with Parliament |

General Directorate for Youth Affairs |

|

Morocco |

Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication |

Directorate of Youth and Children and Women Affairs |

|

Oman |

Ministry of Culture, Sports and Youth |

General Directorate of Youth |

|

Palestinian Authority |

Higher Council for Youth and Sports |

General Directorate for Youth Affairs |

|

Qatar |

Ministry of Sports and Youth |

Directorate for Youth Affairs |

|

Saudi Arabia |

Ministry of Communications and Information Technology |

N/A |

|

Tunisia |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

General Directorate for Youth |

|

United Arab Emirates |

Ministry of Culture and Youth |

Federal Youth Authority; National Youth Agenda Department |

Note: The principal entity responsible for youth policy and programme co-ordination in each economy is shown in bold.

Source: OECD elaboration based available information from survey replies, meetings with public officials and desk-based research; http://www.mjs.gov.dz/index.php/ar/ministere-ar/organisation-ar (Arabic), https://www.mys.gov.bh/ar/about/Pages/Organizational-Structure.aspx (Arabic), http://moy.gov.jo/?q=ar/node/23 (Arabic), http://www.minijes.gov.lb/Ministry/Hierarchy (Arabic), https://mjla.gov.om/legislation/decrees/details.aspx?Id=1237&type=L (Arabic), https://www.msy.gov.qa/index-en.php, http://www.jeunesse.tn/index.php/ar/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%88%D8%B2%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A9/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%B8%D9%8A%D9%85.html (Arabic).

In most MENA administrations, there is a clear organisational and institutional distinction between portfolios in the cases in which the youth portfolio is combined with others in one ministry. For instance, in Algeria and Jordan, there are separate directorates dedicated to sports and youth affairs respectively. In Morocco, the Directorate of Youth, Childhood and Women's Affairs is in charge of youth affairs, while the Directorate of Sport is in charge of sports.

In terms of strategic planning, in Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia, the minister in charge of youth affairs is assisted and advised in their functions by a dedicated committee created within the ministry. In Jordan, the Committee for Planning, Co-ordination and Follow-up,2 presided by the minister of youth, prepares and submits recommendations to the Minister on the plans, programmes and activities of the ministry, including in relation to draft laws and regulations and spending decisions, as well as in the preparation of the annual budget and job descriptions (OECD, 2021[2]). In Morocco, the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication is assisted and advised by a cabinet (OCDE, 2021[3]). In Tunisia, a cabinet of personal advisors (collaborateurs personnels) chosen by the minister of youth and sports assist the minister in the realisation of their mandate, and is responsible for internal (i.e. between specific services) and external co-ordination (i.e. with other ministries) (République Tunisienne, 2007[4]; OCDE, 2021[5]). In the United Arab Emirates, the Minister of State for Youth Affairs is supported by the Youth Agenda Department and the Federal Youth Authority. The Youth Agenda Department is responsible for co-ordination and mainstreaming of youth affairs and represents the Minister of Youth Affairs on all federal councils and strategic committees. The Federal Youth Authority is the executive arm for youth affairs, working directly on youth programmes and policies.

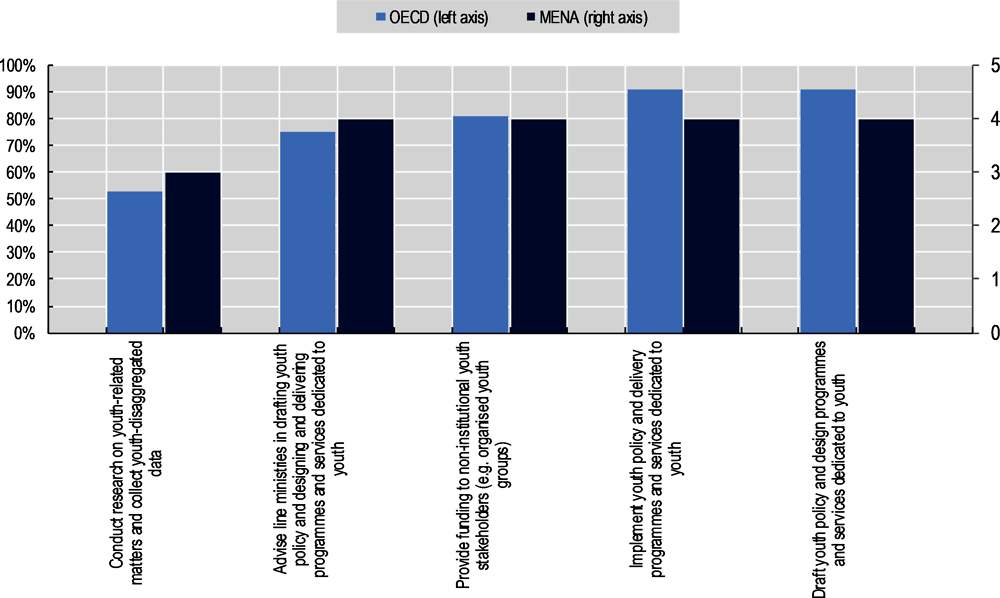

Despite differences in institutional set-up, government entities in charge of youth affairs often assume similar responsibilities across OECD governments and MENA administrations (see Figure 3.1). Evidence finds that nearly all entities in OECD governments (91%) and MENA administrations (4 out of 5 responding entities) implement youth policy and deliver programmes and services dedicated to young people. They also draft youth policy and design programmes and services dedicated to youth (4 out of 5 MENA administrations and 91% of OECD governments) and they advise line ministries in drafting youth policy and designing and delivering programmes and services dedicated to youth (4/5 out of MENA administrations and 75% of OECD governments). These entities also often provide funding to non-institutional youth stakeholders (as happens in 4 out of 5 responding MENA administrations and in 81% of OECD governments). Only around half of all entities in OECD governments (53%) and MENA administrations (3 out of 5) conduct research on youth-related matters and collect youth-disaggregated data (OECD, 2020[1]).

Figure 3.1. Functions of public entities in charge of youth affairs

Note: Data on MENA represents information provided by Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia. Data on OECD represents information from 35 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Youth Governance Survey.

Human and financial resources dedicated to youth affairs

Public authorities need sufficient human and financial resources to develop, implement and monitor youth-responsive policies, programmes and services and to coordinate youth affairs more generally (OECD, 2018[6]). However, evidence collected across more than 40 countries demonstrates that financial and human resources at the government entity steering youth policy and programming are often weak (OECD, 2020[1]). Furthermore, in many countries around the world, up-to-date information about the resources allocated to youth programming is often scarce, making cross-country comparisons difficult and limiting government’s accountability.

Investing in human resources is critical for youth-responsive policies

The development of civil servants is essential to develop better policies, co-create service delivery with citizens, commission service delivery with contracted suppliers, and collaborate with stakeholders in networked settings (OECD, 2017[7]). Ensuring that the civil service is fit-for-purpose, with the right skills and capabilities to work for and with young people in an increasingly complex world is thus crucial to deliver youth-responsive policy making and programming.

The lack of financial and qualified human resources is one of the main challenges identified in the OECD Youth Governance Survey by ministries of youth in Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, and Morocco. For instance, a SWOT Analysis conducted by the Ministry of Youth of Jordan as part of the Strategic and Institutional Development Strategy (2021-24) acknowledges the lack of qualified human resources as a weakness (OECD, 2021[2]). Another challenge underlined by the ministries is the absence of good practices in human resource (HR) management (e.g. recruitment and compensation practices, performance management and workforce planning). For instance, well-defined job descriptions and a performance system based on merits and adequate incentives can be instrumental to strengthen HR management.

An effective and trusted public sector requires adequate capacities and capabilities. The OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability encourages countries to “develop the necessary skills and competencies by creating a learning culture and environment in the public service” including by setting incentives and establishing programmes that support staff’s professional development (OECD, 2019[8]). In Jordan, for instance, the Youth Leadership Centre is in charge of running trainings for new staff in the Youth Directorates and youth centres. Available information suggests that the Centre has organised around five courses annually in recent years, which focus on life skills, internal regulations and the objectives of the National Youth Strategy 2019-25 (OECD, 2021[2]). Training programmes could also support the staff of entities in charge of youth affairs to develop skills in the field of policy and programme design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation. Similarly, in Egypt, the National Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development and the Ministry of Planning and Economic Development have been delivering the annual National Young Leaders Programme since 2015, training 1,500 young government employees for leadership positions within ministries.

The public sector has traditionally been one of the largest employers across the MENA region, with public sector employees representing 25% of total employment and public sector salaries representing 32% of total government spending across the region, which is higher than any other region in the world (Akram Malik and Kromann Kristensen, 2022[9]). By comparison, the public sector represented 18% of total employment across OECD countries in 2019 (OECD, 2021[10]). Relatively higher wages, social protection entitlements and lack of opportunities in the private sector have for long made the public sector a favoured choice for young people entering the labour market in MENA. For instance, among people aged 18-24 surveyed in 2021 across 17 MENA economies3 by the annual ASDA’A BCW Arab Youth Survey, 42% of them highlighted they prefer a job in the public sector, although this preference has attenuated compared to 2019 (ASDA’A BCW, 2021[11]).

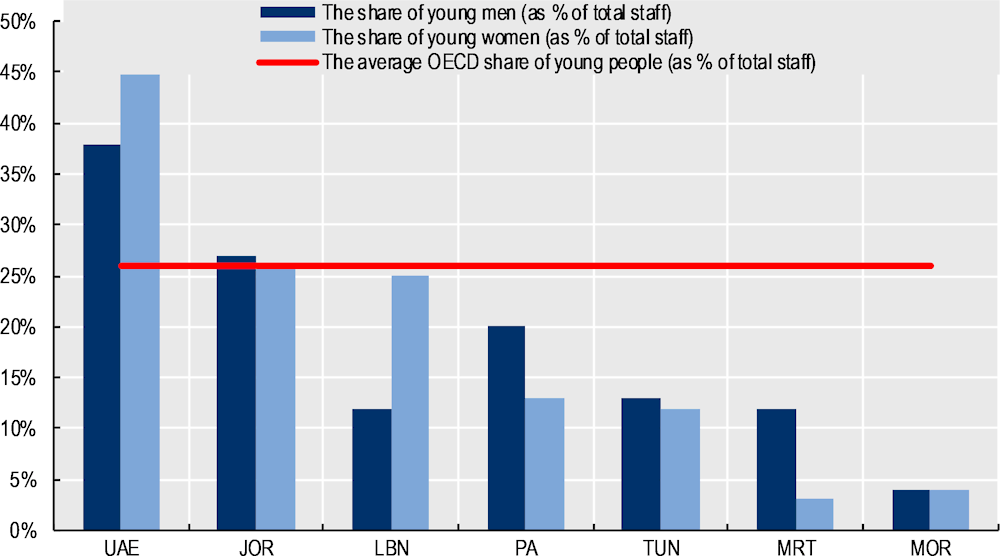

An inclusive public service workforce that represents the diversity of the society it serves, including young people, can benefit from new and diverse skill-sets, innovative ideas, and ultimately contribute to better policy outcomes and stronger citizens’ trust in public institutions. The share of young people in ministries in charge of youth affairs varies considerably, from more than 80% in the United Arab Emirates to less than 10% in Morocco. In Jordan, while only 18% of the Ministry of Youth’s workforce at central level were between the age of 18 and 34, the share rises to 43% in the youth centres at subnational level. In Lebanon, young people account for 37% of the total staff in the Ministry of Youth and Sports. In Morocco, only around 1 in 13 officials in the Ministry of Youth and Sports are 34 years old or younger (see Figure 3.2). Comparatively, as of 2019, 26% of employees across entities in charge of youth affairs in OECD countries were between the age of 18 and 34, on average (OECD, 2020[1]). A considerable gender gap in this age group can be observed in Lebanon (in favour of women) and Mauritania (in favour of men). Chapter 4 further explores the participation and representation of young people in public and political life.

Figure 3.2. Share of young people (aged 18-34) working in the entity in charge of youth affairs in selected MENA administrations and OECD average, 2021 or latest available

Note: The table shows the share of young people aged between 18 and 34, working in the ministry in charge of youth affairs as a percentage of total staff, disaggregated by sex.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]) and OECD calculations based on the replies received from ministries in charge of youth affairs in Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Palestinian Authority, Tunisia and United Arab Emirates.

To promote the diversity of public sector workforce, governments can leverage transparent, open and merit-based processes for recruitment, selection and promotion of candidates (OECD, 2019[8]). The OECD report "Skills for a High Performing Civil Service" highlights development programmes introduced by various OECD member countries to attract and retain public sector talent. For example, in Australia, France and the United Kingdom, among others, partnerships between the civil service and universities offer skills development for talented university graduates to begin careers in the civil service and for high-potential civil servants to progress into leadership positions (OECD, 2017[12]).

Ministries of youth in the MENA region apply different approaches in the recruitment of new talent into the workforce. According to OECD survey results, Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority and the United Arab Emirates have put in place internship and training programmes for young people to join and develop their skills in the public sector. In Egypt, a 2017 presidential decree recommended that each Minister appoints up to four Associate Ministers under the age of 40, whose appointment can be renewed on a yearly basis following a review process: in 2020, a cabinet resolution increased the number of young Associate Ministers for each Minister/Prime Minister to 10. In the United Arab Emirates, a 2019 Cabinet decision made it mandatory for federal government entities to include young Emiratis under the age of 30 in the Boards of Directors of their respective entities for 2-3 year terms.

Governments can also proactively develop their workforce through longer-term, structured graduate programmes aimed at attracting, developing and retaining highly-qualified young talent through training, mentoring, job rotation and accelerated promotion tracks (OECD, 2020[1]). As of 2022, programmes for graduates to join the public sector exist in 42% of government entities in charge of youth affairs across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[1]). Box 3.1 presents innovative efforts of OECD governments and MENA administrations to empower young people in the public administration, including in the context of the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

Box 3.1. Empowering young people in the public administration

Australia: APS Graduate Programs

The APS Graduate Programs allow new graduates in Australia an entry-level pathway into the public sector. The graduate programs generally take 10 to 18 months to complete, with two to three rotations through different work areas, to give participants a range of skills, knowledge and experience at the start of their career. Participants normally follow face-to-face workshops, trainings and simulation activities. Successful completion of the programs can give participants further opportunities of career development within the public sector as well as study assistance for further training.

Portugal: Extraordinary Internship Program in Public Administration

The national COVID-19 response and recovery plan of Portugal includes an EUR 88 million (USD 92 million as of May 2022) provision to increase capacities within the public administration to address modern challenges and build a more resilient, green and digital future. As part of these efforts, the Extraordinary Internship Program in Public Administration offers 500 vacancies to engage young people in public service for up to 9 months. These vacancies are being made available across multiple government sectors, prioritising those with a majority of senior staff to ensure intergenerational knowledge is transferred and service models are rejuvenated.

United Arab Emirates: Youth Empowerment Model

In the United Arab Emirates, the government has elaborated tools to monitor the extent to which the management practices of federal entities are conducive to an environment in which young employees can thrive. In 2021, the Federal Youth Authority launched a Youth Empowerment Model to enable federal entities to assess and improve the way they engage with and empower young employees. The Model has five components: a framework, an assessment, an index, a maturity classification, and best-practice initiatives and innovative practices. The Youth Empowerment Framework defines six pillars of youth empowerment: voice, recognition, purpose, guidance, development and opportunity. It is complemented by a Youth Empowerment Assessment, in which 62 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) with supporting evidence are submitted by each federal entity, while 59 youth KPIs are collected via surveys shared with youth working in each federal entity. The Youth Empowerment Index and the Maturity Classification score federal entities, quantify their achieved level of youth empowerment, and benchmark their year-on-year progress in empowering youth. Finally, the Model recommends different best-practices initiatives that entities can implement to empower young people. Recently, the United Arab Emirates launched the Youth Empowerment Policy, which mandates federal entities to measure and report on youth empowerment annually.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, 2017[7]; OECD, 2022[13]; Federal Youth Authority in the United Arab Emirates, 2021[14])

Financial resources and their transparency remain low, but encouraging trends emerge

In terms of the budget allocated to the ministries in charge of youth affairs, survey results suggest that these resources constitute a small portion of the overall public budget (see Table 3.2), remaining at or significantly below 1% in most administrations with the exception of Tunisia (1.9% in 2020) (Government of Tunisia, 2019[15]), Morocco (2% in 2020) (OCDE, 2021[3]) and Jordan (2.7% in 2020) (General Budget Department in Jordan, 2020[16]). For Bahrain and Lebanon, available information suggests that the resources dedicated to their respective Ministry of Youth and Sports were significantly below 0.1% of the total public budget in 2018 (Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan - Lebanese Ministry of Finance, 2018[17]; Ministry of Finance and National Economy in Bahrain, 2018[18]). Similarly, across OECD countries for which information is available, the share allocated to the entity in charge of youth affairs makes up less than 1% of total public budget in most countries (OECD, 2020[1]). It must be noted that this comparison leaves aside the more significant budgets in ministries of (higher) education, training, employment, social affairs as well as health and others that deliver important programmes and services to young people.

In terms of budgetary allocations to youth ministries over time, available information suggests an increase in recent years in some MENA administrations. In Jordan, the budget allocated to the Ministry of Youth has increased by 43% over three years to reach JOD 33 million (around USD 46.5 million as of May 2022) in 2020, up from JOD 23 million (around USD 32.4 million as of May 2022) in 2017, which is equivalent to an increase in the share of the central government budget from 1.4% to 2.7% in the same period (General Budget Department in Jordan, 2020[16]). In Tunisia, the budget allocated to the Ministry of Youth, Sports and Professional Integration has increased by 16.5% over two years to reach TND 755 million (around USD 247.2 million as of May 2022) in 2020, up from TND 665 million (around USD 217.7 million as of May 2022) in 2018 or an increase in the share of the central government budget from 1.84% in 2018 to 1.93% in 2020 (Government of Tunisia, 2019[15]; OCDE, 2021[5]). In Morocco, reflecting its ambitions for reform and institutional capacity building, the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication’s total expenditures have increased by nearly 60%, from less than MAD 2 billion (around USD 199.5 million as of May 2022) in 2016 to more than MAD 3 billion (around USD 299.2 million as of May 2022) in 2018. This increase appears to be largely explained by a substantial increase in capital expenditures and by the political reshuffle of 2019 that resulted in the integration of culture as a new portfolio of the Ministry. Furthermore, this increase corresponds to a significant increase in relation to overall government spending, from 0.78% in 2016 to almost 2% in 2020 (OCDE, 2021[3]). These rates are significantly higher than the respective allocations in Bahrain, Lebanon and the Palestinian Authority (see Table 3.2).

However, it is important to note that, as most entities in charge of youth affairs also host a second portfolio, only a share of these entities’ budget is allocated specifically to youth policies and programming. For instance, in Tunisia, less than a quarter of the budget allocated to the Ministry of Youth and Sports was dedicated to its youth division in 2020 (equivalent to 0.4% of the total government budget) (Government of Tunisia, 2019[15]).4 In Morocco, 56% of the budget allocated to the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication was dedicated to youth and sports together in 2020 (OCDE, 2021[3]).5 In Jordan, 41% of the budget allocated to the Ministry of Youth was dedicated to its youth development programme in 2020 (General Budget Department in Jordan, 2020[16]).6 Although only 16% of the 41% of the budget allocated to the Ministry of Youth was dedicated to non-infrastructure costs, the vast majority of it covering maintenance of the physical infrastructure owned by the ministry (OECD, 2021[2]). The availability of this information sets Jordan apart from most OECD governments and MENA administrations, as such comparative data is rarely publicly available (OECD, 2021[2]). In the United Arab Emirates, 17% of the budget of the Ministry of Culture and Youth is allocated to the youth portfolio.

Furthermore, proportional cross-government comparisons must be interpreted with caution as total government expenditures vary across governments. For instance, in the United Arab Emirates, the budget allocated to the Ministry of Culture and Youth may appear modest at 0.67% of the total government budget, but the absolute budget is significant at AED 389,743,000 (around 106,110,259 USD as of May 2022).

Transparent and updated information on ministries’ budgets can promote accountability and, in turn, trust in government. For instance, as part of Jordan’s progress in public finance management and fiscal transparency, the General Budget Department, within the Ministry of Finance, set up an online platform to exchange fiscal data across ministries and departments. It makes available online for the public the financial allocations and expenditures by the Ministry of Youth as per each governorate, portfolio and year (General Budget Department in Jordan, 2020[19]). The Ministry of Finance in Tunisia publishes an annual report on the financial allocations and expenditures of the Ministry of Youth and Sports on its website (Ministry of Finance in Tunisia, 2020[20]).

Table 3.2. Share of public budget allocated to youth affairs across MENA, 2018-2021

|

Economy |

Budget allocated to entity in charge of youth affairs (as % of total government budget) |

Budget allocated to youth portfolio (as % of total budget of the entity in charge of youth affairs) |

|---|---|---|

|

Bahrain (2018) |

0.015% |

N/A |

|

Jordan (2020) |

2.7% |

41% |

|

Lebanon (2018) |

0.06% |

N/A |

|

Morocco (2020) |

2% |

16.8% |

|

Palestinian Authority (2020) |

0.19% |

68.8% |

|

Tunisia (2020) |

1.9% |

22% |

|

United Arab Emirates (2021) |

0.67% |

17% |

Note: The table shows the share of budget allocated to the public entities in charge of youth affairs as a percentage of the total public budget and the share of the budget allocated to young people in percentage of the entity’s budget. In Morocco, the budget allocated to young people is for “youth, children and women.”

Source: OECD calculations based on the replies received from the entities in charge of youth affairs of Jordan, Morocco, Palestinian Authority, Tunisia and United Arab Emirates; and on available information on youth budget of the General Budget Department in Jordan (http://www.gbd.gov.jo/GBD/en/Budget/Ministries/general-budget-law-2018); the Ministry of Finance in Tunisia (http://www.finances.gov.tn/fr); Ministry of Youth and Sports in Tunisia (http://www.gbo.tn/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&Itemid=0&gid=109&orderby=dmdate_published&ascdesc=DESC&lang=fr);Jordan(https://jordan.gov.jo/wps/portal/Home/GovernmentEntities/Ministries/Ministry/Ministry%20of%20Youth?nameEntity=Ministry%20of%20Youth&entityType=ministry), Morocco (http://www.mjs.gov.ma/fr), Lebanon (http://www.databank.com.lb/docs/Citizens%20Budget%202018-MoF.pdf), Bahrain (https://www.mofne.gov.bh/Files/L1/Content/CI938-budget%20tables.pdf)

Ensuring coordinated approaches across stakeholders

Youth policy and services are designed and delivered by a variety of governmental and non-governmental stakeholders, at the central and at the subnational level. Avoiding fragmentation and duplication, and promoting synergies, requires strong co-ordination mechanisms across different ministries and agencies (inter-ministerial or horizontal co-ordination) and across authorities at the central and sub-national levels of government (vertical co-ordination) as well as with non-governmental stakeholders.

Inter-ministerial co-ordination on youth affairs

Around half of all OECD countries created an institutionalised mechanism for inter-ministerial co-ordination of youth affairs. Box 3.2 illustrates practices from OECD countries, including inter-ministerial or inter-departmental co-ordination bodies, working groups and focal points (OECD, 2018[6]).

Box 3.2. Examples of horizontal co-ordination mechanisms for youth policy

Inter-ministerial or inter-departmental co-ordination bodies are composed of ministries with a responsibility to implement specific commitments of the national youth policy. The ministry with formal responsibility to coordinate youth affairs is always part of these structures and usually coordinates and prepares its meetings. For instance, Luxembourg set up an inter-department committee for this purpose. It is composed of representatives of the ministers of children and youth, children, children’s rights, foreign affairs, local affairs, culture, cooperation and development, education, equal opportunities, family, justice, housing, police, employment, health and sports.

Working groups are often established on an ad hoc basis and assume responsibility for specific topics. In principle, only ministries with corresponding portfolios are involved in the respective thematic working group. Inter-ministerial co-ordination bodies may be complemented by working groups in which line ministries may take the lead in coordinating its activities. In the United States, an Interagency Working Group on Youth Programs supports coordinated federal activities in the field of youth.

Focal points may be appointed to oversee the work on youth affairs within line ministries and coordinate youth-related programming with the entity in charge of youth affairs. In Slovenia, each Ministry has a dedicated youth focal point to facilitate co-ordination with the Council of the Government of the Republic of Slovenia for Youth (URSM) and other ministries. In Flanders, Belgium, a contact point for youth exists in all agencies and departments.

Source: (OECD, 2020[1])

In the MENA region, effective inter-ministerial co-ordination is one of the key challenges reported by ministries in charge of youth affairs. More specifically, the lack of institutional mechanisms and high turnover of leadership positions are seen as the most important barriers. Frequent leadership changes in the ministries of youth can make it more difficult to create trust and a culture of cooperation between different ministries over the long term.

Public administrations in the MENA region adopt different mechanisms for inter-ministerial co-ordination (see Table 3.3). Mauritania, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority and Tunisia have put in place an institutional coordinating body or committee. For instance, in Mauritania, the draft National Youth Strategy for 2020-2024 includes the structure of an Inter-ministerial Youth Committee. In Morocco, the Consultative Council for Youth and Associative Action (CCJAA) was created in 2017, serving as advisory body on youth issues, and tasked to ensure strong links between ministries, the community, civil society and the highest level of government.7 It prepares quarterly updates and annual reports on the progress made to the inter-ministerial committee and provides youth-led advices and recommendations to the King and the government (OCDE, 2021[3]). Following the creation of an inter-ministerial co-ordination body, it is important to ensure its effectiveness through an inclusive membership, clear distribution of responsibilities and regular meetings.

In Jordan, no such co-ordination body exists yet. Instead, similar to practices that exist in Morocco and Tunisia, Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) are used to facilitate co-ordination with other ministries. In Tunisia, the Ministry of Youth and Sports has signed 10 memoranda of understanding, currently in force, among others with the Ministry of Justice.

Table 3.3. Approaches to inter-ministerial co-ordination across MENA administrations

|

Economy |

Institution responsible for horizontal co-ordination |

Main type of co-ordination mechanisms used |

|---|---|---|

|

Jordan |

Ministry of Youth |

Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) |

|

Lebanon |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

No specific mechanism; Informal and ad hoc meetings |

|

Mauritania |

Ministry of Culture, Youth, Sports and Relations with Parliament |

Institutional co-ordination bodies and committees |

|

Morocco |

Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication |

Memorandum of Understanding (MoU); Institutional co-ordination bodies and committees; Formal meetings |

|

Tunisia |

Ministry of Youth and Sports |

Memorandum of Understanding (MoU); Institutional co-ordination bodies and committees; Formal meetings |

|

United Arab Emirates |

Ministry of Culture and Youth |

Institutional coordinating bodies and committees; formal meetings |

Note: The table shows the entities responsible for the horizontal co-ordination of youth affairs and the main co-ordination mechanisms used in selected MENA economies. Approaches for Mauritania refer to the steering committee elaborating the National Youth Strategy 2020-2024.

Source: OECD work based on the replies received from ministries in charge of youth affairs of Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia and United Arab Emirates.

In the United Arab Emirates, a consultative youth council was created to allow young people to make their voice heard by the government in 2017. The Emirates Youth Council (EYC) serves as an advisory body for the government and the Minister of State for Youth on national issues and engagement with governmental and non-governmental stakeholders. The EYC model has been adopted and replicated in thirteen ministries, where young employees of the respective ministry coordinate with other ministries and different stakeholders on topics related to young people and supervise the organisation of relevant activities and programmes (Federal Youth Authority in the United Arab Emirates, 2020[21]).

Practices from across OECD countries demonstrate that strong institutionalised links between the entity with formal responsibility for youth affairs and Centre of Government (CoG) institutions8 can mobilise political buy-in to place young people’s considerations at the centre of government action. In Canada, for instance, until 2019, the Prime Minister was also the Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs and Youth. This appointment made youth affairs a part of the Prime Minister’s portfolio and hence one of the priorities of the Centre of Government (OECD, 2021[2]). In Austria (Federal Chancellery), Colombia (Presidency of the Republic), Italy (Presidency of the Council of Ministers) and Japan (Cabinet Office), youth affairs continue to being coordinated by CoG institutions (OECD, 2020[1]). To facilitate inter-ministerial co-ordination, in France, the Director in the department in charge of youth affairs is also the Inter-Ministerial Delegate for Youth (see Box 3.3).

The location of the youth portfolio can also have an impact on its specific functions (e.g. monitoring and co-ordination roles), resources (e.g. budgets and human resources) and scope of influence (e.g. convening power) (OECD, 2020[1]). Indeed, across OECD countries, none of the respective units at the CoG in charge of youth affairs report that line ministries and subnational authorities do not show sufficient interest in co- coordinating with them. In contrast, 20% of the entities that are organised as ministries or departments perceive this as a challenge (OECD, 2020[1]).

Box 3.3. Inter-ministerial co-ordination in France

In France, the Director of the Youth, Non-formal Education and Voluntary Organisation Directorate (DJEPVA), located inside the Ministry of Education, is also the Inter-Ministerial Delegate for Youth. The Director chairs the meetings of the inter-ministerial committee for youth which is responsible for coordinating and building partnerships with other ministries, coordinating the implementation of youth-led projects, and facilitating young people’s access to information and their rights.

Source: OECD work based on the official website of the Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sports in France (Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sports in France, 2021[22]).

Co-ordination between central and sub-national authorities

Effective co-ordination across different levels of government is needed to translate and the commitments in national youth strategies into programmes and services on the ground that help improve the situation of young people in their respective local contexts. The first interaction between young people and the public administration often takes place at the municipal level where important services and programmes are delivered in most countries.

Historically, most MENA economies are highly centralised, with local administration expenditure representing about 5% of GDP on average across the MENA region (Kherigi, 2019[23]), compared to about 16% of GDP on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2020[24]). However, in recent years, some MENA governments have engaged in a process of decentralisation (e.g. Jordan and Tunisia) or regionalisation (Morocco) with a view to reinforcing local institutional capacities and creating new elected bodies at the subnational level. These changes were, in part, prompted by the need to bring policies and services closer to people and to address regional disparities and lack of state services outside large cities (OECD, 2016[25]).

In Jordan, the 2015 Jordanian Decentralisation Law and the Municipality Law led to the establishment of elected councils in municipalities and governorates (OECD, 2017[26]). Furthermore, in 2017, the Ministry of Youth of Jordan started to give youth directors at the governorate level greater administrative and financial autonomy in an effort to facilitate procedures and approval processes (OECD, 2021[2]). In Morocco, the 2011 constitution introduced the “advanced regionalisation” reform process (“régionalisation avancée”), which aims to strengthen and ensure the autonomy of local authorities, particularly the regions and municipalities. This was followed by a new set up of the national institutional and administrative organisation by the 2015 organic laws,9 which encourage the involvement of the 12 regions in the design and monitoring of the Regional Development Programme through participatory mechanisms. The laws also envisages the creation of an advisory body responsible for studying youth-related issues (OCDE, 2021[3]). In Tunisia, the 2014 Constitution states that the local level is principally responsible for local development, further specified with the adoption of Law No. 2018-29 in 2018 (République Tunisienne, 2018[27]), and that local authorities should adopt mechanisms of participatory democracy and adopt principles of open governance. Furthermore, in Tunisia, youth commissariats represent the Ministry of Youth and Sports in each of the 24 governorates and have administrative, financial, technical and educational responsibilities on local issues related to youth (OCDE, 2021[5]).

The transfer of competencies to subnational governments can encourage youth participation in decision-making and has already resulted in the creation of local youth councils in Morocco and Tunisia (OECD, 2019[28]). However, the reforms initiated by Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia still need to prove their positive impact for young people as considerable regional disparities persist. Moreover, decision making processes in public administrations across the MENA region continue to remain highly centralised while administrative and technical capacities at the subnational level are generally weak. Qatar identifies the lack of interest among subnational stakeholders as the most important challenge, while Jordan, Mauritania, and Tunisia point to the challenge of insufficient capacities at subnational level. Moreover, in most public administrations across the region, there is no institutional mechanisms (e.g. joint committees) to facilitate co-ordination across the different levels of administration on youth affairs.

National ministries and local authorities also need to coordinate with a large number of institutions, often with varying statuses, working on youth-related aspects. In Tunisia, for instance, the National Youth Observatory (Observatoire National de la Jeunesse, ONJ) is national-level youth institution attached to the Ministry of Youth and Sports that contributes to the preparation and monitoring of youth policies through research and analysis (OCDE, 2021[5]). In the United Arab Emirates, the Cabinet established the Federal Youth Authority, which is headed by the Minister of State for Youth Affairs. The Authority is responsible for coordinating the activities and strategies of seven local youth councils to ensure their alignment with the National Youth Agenda and the United Arab Emirates' Centennial 2071 (Cabinet of the United Arab Emirates, 2018[29]; Federal Youth Authority in the United Arab Emirates, 2022[30]). Furthermore, youth councils and youth houses are important players at the local level: these are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Public management tools to mainstream the perspectives of young people in policy making and service delivery

The previous sections underlined why it is important that youth policy and services are integrated and well-coordinated. In addition to national integrated strategies and institutionalised co-ordination measures, public management tools can help in embedding the perspectives of young people beyond narrowly defined policy portfolios such as education and employment. In the rule making process, through the allocation of public resources and via public procurement practices, governments can use public management tools to achieve broader societal outcomes, notably to improve the situation and opportunities of young people.

The role of disaggregated data for public management tools

As discussed in Chapter 2, the use of evidence in policymaking can improve the design, implementation and evaluation of policy making and service delivery (OECD, 2020[31]). In order to mainstream the needs of young people in policymaking, governments hence need to ensure that the evidence used to inform policymaking is disaggregated by age. At the same time, young people are a heterogeneous group who live in highly different circumstances, for instance depending on their socio-economic status, gender and geographic area among others. As inequalities tend to accumulate over the life cycle (OECD, 2017[32]), governments can make efforts to go beyond age-disaggregation of data and evidence and ensure that evidence is disaggregated by other characteristics as well (OECD, 2021[2]). Collecting and using quality disaggregated data requires human capacities and co-ordination with a number of stakeholders across policy areas: Chapter 2 discussed the efforts and challenges in the collection and use of disaggregated evidence to inform national youth strategies. Beyond NYS, collecting and using age-disaggregated data is necessary to ensure an effective use of the public management tools discussed below.

Anticipating the impact of new legislation on young people and age groups

The OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance (OECD, 2012[33]) recognises regulatory impact assessments (RIAs) as a key tool for evidence-based policymaking and the OECD Best Practice Principles on Regulatory Impact Assessment present guidance on the elements necessary to develop and sustain a well-functioning RIA system (OECD, 2020[34]). While 31 OECD countries used RIAs to anticipate the impact of new legislation on specific social groups as of 2020, evidence shows that the use of impact assessments to anticipate outcomes for young people specifically remains limited. In 2020, 32% of OECD countries reported using general RIAs and providing specific information on the expected impact on young people. In turn, Austria, France, Germany and New Zealand apply ex ante “youth checks” or a similar tool to consider the impact of new laws and policies on young people more systematically (see Box 3.4).

Box 3.4. Youth checks in OECD countries

Established in 2013, Austria was the first country to apply a “youth check” at the national level. The youth check provides for an outcome oriented impact assessment on the effects of policy measures on young people aged 0-30. Along five steps (i.e. problem analysis, defining aims, defining measures, impact assessment and internal evaluation), it obliges all ministries to assess the expected effects of each legislative initiative including laws, ordinances, other legal frameworks and major projects, on children and youth.

In Germany, the youth check (Jugendcheck) acknowledges that the life situation and participation of present and coming youth generations should be considered in all political, legislative and administrative actions of the Federal Ministries. It is considered to be an instrument to support the implementation of the National Youth Strategy and a lens through which other relevant strategies (e.g. on demography and sustainability) should be regarded. Along 10-15 questions (e.g. Does the action increase or alter the participation of young people to social benefits?) and three central test criteria (e.g. access to resources and possibilities for youth to participate), it anticipates the expected impact of new legislation on young people aged 0-27.

Some OECD countries analyse the impact of new laws and policies not only on young people but across different age groups. For example, upon the recommendation of the Social and Economic Council of the Netherlands (SER), the Cabinet of the Netherlands has worked towards a “Generation Test” in order to generate evidence on the expected impact of policy and regulatory proposals across age groups and to consider the interests of young people more systematically in policy design. In the elaboration process, the Cabinet has collaborated with different youth groups, such as the SER Youth Platform (Jongerenplatform) and the Dutch National Youth Council, as well as planning agencies, the Council of State and the SER (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment in the Netherlands, 2020[36]; OECD, 2020[1]).

In 2020, a RIA policy guide was launched in Jordan, in cooperation with the SIGMA Programme,10 who worked closely with government stakeholders in Jordan on the guide and offered technical assistance in its formulation. Based on an overview of good practices, the policy guide aims to build and strengthen the capacities of government institutions and decision-makers on the use and implementation of impact assessment instruments more generally (MENA FN, 2020[37]; OECD, 2021[2]).

Public budgeting for youth-responsive policy outcomes

The OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance characterises the public budget as the “central policy document of government, showing how annual and multi-annual objectives will be prioritised and achieved” (OECD, 2015[38]). Over the past years, many OECD countries have turned to public budgeting to achieve cross-cutting high-level priorities with the introduction of ‘’gender budgeting’’ “green budgeting”, “well-being budgeting” and “SDG budgeting”, among others (Downes and Nicol, 2020[39]). In the MENA region, mainstreaming high-level priorities in public budgeting can build on existing OECD guidance, such as OECD Gender Budgeting Framework (Downes and Nicol, 2020[39]).

The OECD Youth Stocktaking Report describes youth-sensitive budgeting as a way to ”integrate a clear youth perspective within the overall context of the budget process, through the use of special processes and analytical tools, with a view to promoting youth-responsive policies” (OECD, 2018[6]). For instance, among OECD countries, Canada considers youth-specific objectives in the framework of gender budgeting, including in its COVID-19 Economic Response Plan. In Spain, ministries are required to send a report to the State Secretariat for Budget Expenditures to analyse the childhood, youth and family impact of spending programmes in preparation of the General Budget. The Slovak Council for Budget Responsibility considers intergenerational fairness in connection with the long-term sustainability of public finances (OECD, 2020[1]).

In Jordan, efforts have been made towards integrating considerations of specific age cohorts in budgeting. With the support of the National Council for Family Affairs and UNICEF, the Government of Jordan implemented a child-friendly budgeting initiative to support the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in Jordan. Beginning in 2009, a child-sensitive budget analysis was conducted for eight ministries and in the first phase of the project the Ministries of Health, Labour, Social Development, and Education were selected to pilot the study, introduce child budgeting into their budgets and develop Child Budget Engagement Strategies. The initiative also worked on projections of the medium-term expenditure frameworks to monitor future allocations to child and social protection programmes (OECD, 2021[2]).

In Morocco, the experience with gender-responsive budgeting provides important lessons for the use of public budgeting to generate positive outcomes for other social groups, including young people. In 2013, the Centre of Excellence for Gender Responsive Budgeting (CE-BSG) was created to mainstream Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB) through training, coaching and the production of tools. In 2015, laws were passed making GRB mandatory for all ministries and making gender-responsive planning mandatory at the local level (OECD, 2019[40]; OCDE, 2021[3]).11

When public expenditure decisions are communicated in a transparent way, they can also be a powerful tool to restore citizens’ trust in government (OECD, 2021[41]). A number of public administrations across the MENA region have adopted citizens budgets12 annually, such as in Egypt13 (since 2014), Jordan14 (since 2011), Morocco15 (since 2012), Tunisia16 (since 2014), and the Palestinian Authority17 (published in 2016). Furthermore, in Tunisia, performance-based budgeting (Gestion du Budget par Objectifs, GBO) was adopted across 18 ministries (85% of the budget) by 2016 with the objective of increasing transparency and improve government performance (OECD, 2017[42]). Several ministries also began developing a medium-term expenditures framework (MTEF), a key pillar of Tunisia’s public financial management reform to increase accountability (OCDE, 2021[5]). In Jordan, as discussed above, the General Budget Department within the Ministry of Finance publishes on the website of the Ministry the general budget law approved by the parliament, detailed budget reports for all government units, and the Citizen Guide to the Budget issued annually since 2011 (OECD, 2021[2]). Morocco adopted a new Organic Finance Law (Loi Organique relative à la loi de finances, LOLF) in 2015, designing budgets around programmes for pilot ministries, and introduced a multi-annual financial programming (OCDE, 2021[3]).

Public administrations in the MENA region can take additional steps to improve budget transparency by taking proactive steps in making budget information more accessible to young people. For instance, some OECD countries have started to publish their national budgets in more user-friendly ways, for instance by using graphics in Slovenia or using interactive approaches in Australia and Ireland (OCDE, 2021[3]).

Civil-society organisations can also play an important role in promoting budget transparency. Initiatives have been undertaken by civil-society organisations in Lebanon and Tunisia to involve young people in monitoring public expenditures and government performance. In Lebanon, the Gherbal Initiative was founded in 2017 on the idea that sharing accessible data can reduce corruption. The website collects and visualises budget data from state institutions in Lebanon to promote transparency and accountability and to encourage public discourse and political action (Gherbal Initiative, 2022[43]). In Tunisia, the youth-led civil society organisation Al Bawsala initiated the project “Marsad Budget” (Al Bawsala, 2016[44]), a website that aims at simplifying budget data and information to make it understandable for ordinary citizens and to involve them in public debates about it. The website offers easy access to budget and human resources data for the Presidency, the Parliament and the different ministries. It shows the public expenditures for each entity since 2012 and the allocation of resources for the entities in which performance-based budgeting has been introduced (OCDE, 2021[5]).

Engaging young people in deciding how public resources are allocated can increase their ownership in an exercise that is otherwise perceived as technical and disconnected from their lives. Participatory budgeting programmes allow citizens to make a choice about how budgets shall be allocated across specific projects or priority areas. However, across OECD countries, participatory budgeting has had little application at the national level, and mixed results at municipal levels (OECD, 2019[45]). Furthermore, there is a risk that sometimes organised groups may capture the process to serve their own interests (OECD, 2019[45]). As of 2019, OECD countries rely mainly on traditional participatory mechanisms, such as 25 countries that report using public hearings of a permanent committee, with digital tools still being under-utilised (OECD, 2019[45]).

The Netherlands gave an example of an innovative practice introduced in 2017, the “V-100”. Organised by the Dutch Parliament, the “V-100” brings together 100 participants from society who scrutinise the annual budget reports and make suggestions to committees on potential questions for the responsible minister (OECD, 2019[45]). Such programmes can be particularly useful when young people from diverse backgrounds are involved throughout the design, selection and implementation of specific projects (see Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. How to involve young people in public budgeting?

In Costa Rica, a youth committee in each of the 82 cantons receives annual funding from the National Council of Young Persons to develop and implement activities and projects formulated by each committee on the basis of the priorities and objectives set by its young members.

In Portugal, a participatory budgeting initiative was undertaken at the national level in 2017. Young people aged 14-30 were invited to elaborate proposals in fields such as sport, social innovation, science education and environmental sustainability for a total amount of EUR 300,000. Furthermore, at the sub-national level, the Portuguese Municipality of Gaia began implementing in 2019 a three-year participatory budgeting initiative dedicated to young people aged 13-30 with a total budget of EUR 360,000 in 2021.1

1. The initiative falls under the framework of the GOP+Youth 2021 (GOP+Jovem 2021, Gaia Orçamento Participativo) project which focuses on three main areas: i) creativity, culture and sport; ii) environment and sustainability; iii) technology and entrepreneurship.

Early experiences with youth participatory budgeting and budget monitoring and control have emerged in the MENA region, notably in Morocco and Tunisia (OCDE, 2021[3]). For instance, although still limited in number, participatory budgeting initiatives have been set up in recent years across municipalities of Morocco, including Chefchaouen, Larache, Tetouan and Tiznit.18 Several activities, such as training cycles, participatory workshops to propose projects and a day of voting by citizens to prioritise them were organised. At the end of the projects, a public accountability hearing was organised in each of the municipalities to inform citizens of the results, and a charter of principles on participatory budgeting was voted by each municipal council (OCDE, 2021[3]; Open Edition Journals, 2021[47]).

In 2014 in Tunisia, citizens and especially young people in La Marsa, Menzel Bourguiba, Tozeur and Gabes were invited to participate in the allocation of 2% of the municipal budget (OECD, 2019[48]). La Marsa, a community of 110,000 residents, was the first municipality in Tunisia to institute a participatory budgeting programme, with a focus on public lighting. A series of public meetings were held in each of the five districts of the municipality to explain participatory budgeting, provide an overview of the city budget, and present technical information on lighting services delivery. In small groups, participants then discussed, presented and voted on possible projects and priorities to their peers. The projects and priorities were then presented and voted by districts’ delegates in municipal assemblies. As a result, lighting was increased in high crime areas and near schools, as well as in places frequented by women and children. The district delegates were also involved during the implementation stage and maintained communication with their local communities on progress (OECD, 2020[49]; OECD, 2021[2]).

Leveraging public procurement for youth-sensitive outcomes

Accounting for 12% of GDP in OECD countries, public procurement is an important tool to support wider cultural, social, economic and environmental outcomes beyond the immediate purchase of goods and services (OECD, 2020[1]; OECD, n.d.[50]). The OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement also underlines the importance of pursuing complementary secondary policy objectives through public procurement in a balanced manner against the primary procurement objective (OECD, 2015[51]).

Although some MENA administrations have conduced reforms of their public procurement systems, such as in Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia (OECD, 2013[52]), there remains wide scope for MENA administrations to leverage public procurement to promote youth-sensitive outcomes.

In the context of youth policy, public procurement could be leveraged to support the participation of young entrepreneurs or youth-owned businesses in procurement processes and to assess the differentiated impacts of procurement projects on across age groups (OECD, 2020[1]). For example, the Ministry of Children of New Zealand has designed an innovative procurement process to create opportunities for young Māori providers to deliver a more effective community-based youth remand service (Government of New Zealand, 2020[53]). In Wales in the United Kingdom, the adoption of the Well-Being of Future Generations Act in 2015 enshrined in law the pursuit of economic, social, environmental and cultural well-being as the central organising principle of the public service (OECD, 2020[1]). Beginning in 2019, the Office of the Future Generations Commissioner undertook an assessment of procurement practices and their impact on future generations, which culminated in the 2021 report “Procuring well-being in Wales” with recommendations for both the Welsh government and public bodies (Office of the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, 2021[54]).

Policy recommendations

Limited institutional and administrative capacities in public entities in charge of youth affairs at national and sub-national levels make it difficult to implement more integrated and inclusive measures targeting young people. Moreover, co-ordination across different institutional and non- institutional stakeholders is a challenge. Finally, public management tools to mainstream the perspectives of young people across all policy areas, based on age-disaggregated evidence, are often absent or not fully integrated when strategic priorities are defined.

To mainstream the perspectives of young people from different backgrounds in policy making, public administrations could consider:

providing adequate human and financial resources to institutional stakeholders at all levels to design and deliver youth policies, services and programmes;

establishing institutional mechanisms and incentives for horizontal and vertical co-ordination to ensure the coherent delivery of youth policies, services and programmes;

mainstreaming the perspectives of young people and monitoring and evaluating policy outcomes on young people more systematically by collecting and using age-disaggregated data and consider applying public management tools, including regulatory impact assessments and public budgeting tools; and

promoting the representation of young people in the public sector workforce, as well as inter-generational learning, by systematically monitoring age diversity and inclusion in the public sector workforce; adopting measures to proactively attract, develop and retain young talent including through effective on-boarding opportunities and dedicated graduate programmes; and implementing strategies to harness the benefits of a multigenerational workforce.

References

[9] Akram Malik, I. and J. Kromann Kristensen (2022), In MENA, civil service performance matters more than ever, Arab Voices, World Bank, Washington DC, https://blogs.worldbank.org/arabvoices/mena-civil-service-performance-matters-more-ever (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[44] Al Bawsala (2016), Marsad Budget, http://budget.marsad.tn/ar/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

[11] ASDA’A BCW (2021), Arab Youth Survey 2021: Hope for the Future, ASDA’A BCW, https://arabyouthsurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/whitepaper/AYS-2021-WP_English-14-Oct-21-ABS-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[29] Cabinet of the United Arab Emirates (2018), UAE Cabinet approves Federal Youth Authority Board, https://www.uaecabinet.ae/en/details/news/uae-cabinet-approves-federal-youth-authority-board (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[39] Downes, R. and S. Nicol (2020), “Designing and implementing gender budgeting – a path to action”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, https://doi.org/10.1787/689198fa-en.

[30] Federal Youth Authority in the United Arab Emirates (2022), About Federal Youth Authority, Federal Youth Authority, https://youth.gov.ae/en/about (accessed on 8 February 2022).

[14] Federal Youth Authority in the United Arab Emirates (2021), Youth Empowerment Model, https://youth.gov.ae/en/youth-empowerment-model (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[21] Federal Youth Authority in the United Arab Emirates (2020), Youth Councils, https://councils.youth.gov.ae/en (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[19] General Budget Department in Jordan (2020), 3050- Ministry of Youth, http://www.gbd.gov.jo/uploads/files/gbd/draft-min/2020/en/3050.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

[16] General Budget Department in Jordan (2020), Budget of Ministry of Youth, http://www.gbd.gov.jo/uploads/files/gbd/draft-min/2020/en/3050.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2021).

[55] General Budget Department in Jordan (2020), Citizen Guide to the Budget, http://www.gbd.gov.jo/en/citizen-guid (accessed on 8 December 2021).

[43] Gherbal Initiative (2022), Gherbal Initiative, https://elgherbal.org/ (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[53] Government of New Zealand (2020), Designing a procurement process to create opportunities for Māori providers and identify a partner, https://www.procurement.govt.nz/broader-outcomes/creating-opportunities-case-study/ (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[15] Government of Tunisia (2019), Loi n° 2019-78 du 23 décembre 2019, portant loi de finances pour l’année 2020, Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne, http://www.finances.gov.tn/sites/default/files/2020-02/Loi_finances_2020_fr.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

[17] Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan - Lebanese Ministry of Finance (2018), Citizen Budget 2018, http://www.databank.com.lb/docs/Citizens%20Budget%202018-MoF.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

[35] Jugend für Europa (2013), Models and instruments of Cross-sectorial Youth Policy: A comparative survey of 9 countries, European Peer Learning on Youth Policy, https://www.jugendfuereuropa.de/downloads/4-20-3463/130930_JfE__MKP_Ergebnisse.pdf.

[23] Kherigi, I. (2019), The Role of Decentralization in Tunisia’s Transition to Democracy, The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, http://www.fletcherforum.org/home/2018/10/14/the-role-of-decentralization-in-tunisias-transition-to-democracy.

[37] MENA FN (2020), Jordan- Gov’t keen to upgrade public services — PM, https://menafn.com/1100828067/Jordan-Govt-keen-to-upgrade-public-services-PM (accessed on 8 December 2021).

[58] MIFTAH (2021), Fiscal Justice, http://www.miftah.org/Publications2020.cfm?ThemeID=6 (accessed on 9 December 2021).

[59] Ministry of Economy and Finance in Morocco (2021), Citizen’s Budget, https://www.finances.gov.ma/fr/Nos-metiers/Pages/Budget-citoyen.aspx (accessed on 9 December 2021).

[18] Ministry of Finance and National Economy in Bahrain (2018), Recurrent Expenditure by Ministries & Government Agencies for The Fiscal Years 2017 & 2018, https://www.mofne.gov.bh/Files/L1/Content/CI938-budget%20tables.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

[56] Ministry of Finance in Egypt (2021), Citizen’s Budget, https://www.mof.gov.eg/ar/archive/stateGeneralBudget/5fd9d770f0a7ba0007ee0ce9/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%AA%20%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9 (accessed on 9 December 2021).

[57] Ministry of Finance in Tunisia (2021), Ministry of Finance, http://www.finances.gov.tn/fr (accessed on 9 December 2021).

[20] Ministry of Finance in Tunisia (2020), State Budget for the Year 2021 - Ministry of Youth, Sports and Professional Integration, http://www.finances.gov.tn/ (accessed on 5 November 2021).

[22] Ministry of National Education, Youth and Sports in France (2021), La direction de la jeunesse, de l’éducation populaire et de la vie associative (DJEPVA), https://www.jeunes.gouv.fr/La-direction-de-la-jeunesse-de-l (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[36] Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment in the Netherlands (2020), Government response to SER Outlook ’High Expectations, https://www.tweedekamer.nl/kamerstukken/detail?id=2020Z03085&did=2020D06517 (accessed on 4 February 2022).

[46] Municipal Council of Gaia (2021), GOP+Jovem 2021, https://www.cm-gaia.pt/pt/cidade/juventude/gop-jovem-2021/ (accessed on 21 December 2021).

[3] OCDE (2021), Renforcer l’autonomie et la confiance des jeunes au Maroc, Examens de l’OCDE sur la gouvernance publique, Éditions OCDE, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/588c5c07-fr.

[5] OCDE (2021), Renforcer l’autonomie et la confiance des jeunes en Tunisie, Examens de l’OCDE sur la gouvernance publique, Éditions OCDE, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/122f7b9e-fr.

[13] OECD (2022), Delivering for youth: How governments can put young people at the centre of the recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[2] OECD (2021), Empowering Youth and Building Trust in Jordan, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8b14d38f-en.

[10] OECD (2021), Government at a Glance 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1c258f55-en.

[41] OECD (2021), Trust in Government, https://www.oecd.org/gov/trust-in-government.htm (accessed on 8 December 2021).

[1] OECD (2020), Governance for Youth, Trust and Intergenerational Justice: Fit for All Generations?, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c3e5cb8a-en.

[24] OECD (2020), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/959d5ba0-en.

[31] OECD (2020), Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments that Work Well, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c03e01b3-en.

[34] OECD (2020), Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a9638cb-en.

[49] OECD (2020), Supporting Open Government at the Local Level in Jordan, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/open-government/supporting-open-government-at-the-local-level-in-jordan.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2022).

[40] OECD (2019), Achievements, Impacts and Challenges of Implementing Gender Responsive Budgeting in Morocco, Presentaton on July 18, 2019, Caserta, Italy.

[45] OECD (2019), Budgeting and Public Expenditures in OECD Countries 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307957-en.

[48] OECD (2019), Engaging and Empowering Youth in OECD Countries: A youthful summary of the 2018 Stocktaking Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/engaging-and-empowering-youth-across-the-oecd.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2022).

[8] OECD (2019), Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0445 (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[28] OECD (2019), Youth Participation in Public Life: Local Youth Councils, 7th Mediterranean university on youth and global citizenship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/Summary-MEDUNI-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2021).

[6] OECD (2018), Youth Stocktaking Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/youth-stocktaking-report.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

[32] OECD (2017), Bridging the Gap: Inclusive Growth 2017 Update Report, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/inclusive-growth/Bridging_the_Gap.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2022).

[12] OECD (2017), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264280724-en.

[7] OECD (2017), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264280724-en.

[42] OECD (2017), Stocktaking Report: Tunisia, https://www.oecd.org/mena/competitiveness/Stocktaking-Report-Tunisia-Compact-EN.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2021).

[26] OECD (2017), Towards a New Partnership with Citizens: Jordan’s Decentralisation Reform, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264275461-en.

[25] OECD (2016), Youth in the MENA Region: How to Bring Them In, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265721-en.

[38] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Budgetary Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/Recommendation-of-the-Council-on-Budgetary-Governance.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

[51] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0411 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

[60] OECD (2014), Centre Stage: Driving Better Policies from the Centre of Government, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/Centre-Stage-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2021).

[52] OECD (2013), Regulatory Reform in the Middle East and North Africa: Implementing Regulatory Policy Principles to Foster Inclusive Growth, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204553-en.

[33] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/49990817.pdf.

[50] OECD (n.d.), Public procurement, https://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/ (accessed on 8 February 2022).

[54] Office of the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales (2021), Procuring well-being in Wales, https://www.futuregenerations.wales/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/ENG-Section-20-Procurement-Review.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2022).

[47] Open Edition Journals (2021), Special file: The Year of the Maghreb: 60 years of struggle, 24, https://doi.org/10.4000/anneemaghreb.7285.

[61] Petrie, M. and J. Shields (2010), “Producing a Citizens’ Guide to the Budget: Why, What and How?”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, https://doi.org/10.1787/budget-10-5km7gkwg2pjh.

[27] République Tunisienne (2018), Loi organique n° 2018-29 du 9 mai 2018, relative au code des collectivités locales, Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne, http://www.collectiviteslocales.gov.tn/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Code_CL_Loi2018_29.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

[4] République Tunisienne (2007), Decree n° 2007-1124 of May 7, 2007, on the organization of the Ministry of Youth, Sports and Physical Education, Journal Officiel de la République Tunisienne, http://www.iort.gov.tn/WD120AWP/WD120Awp.exe/CTX_6672-14-bwXCZpstjJ/AfficheTexteJuridiqueIntegral/SYNC_-716614264 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

Notes

← 1. The CoG is “the body of group of bodies that provide direct support and advice to Heads of Government and the Council of Minister, or Cabinet”. The CoG is mandated to ensure the consistency and prudency of government decisions and “to promote evidence-based, strategic and consistent policies” (OECD, 2014[60]).

← 2. Regulation No. (78) of 2016 on “the administrative organisation of the Ministry of Youth” defines its organisational structure. The Regulation also stipulates the creation of the Committee for Planning, Co-ordination and Follow-up, which assists and advises the Minister in his functions (OECD, 2021[2]).

← 3. Survey responses were collected across Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, the Palestinian Authority, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

← 4. In Tunisia, the Ministry of Youth and Sports’ 2020 budget was divided into four themes: youth, sport, physical education, and steering and support.

← 5. In Morocco, the Ministry of Youth, Culture and Communication’s 2020 budget was divided, for the first time, into three performance projects concerning: communication, culture and youth and sports.

← 6. In Jordan, the Ministry of Youth’s 2020 budget was divided into three programmes: administration and supportive services, youth development and sport development.

← 7. Bill No. 89-15 establishing the CCJAA was adopted by the House of Representatives in Morocco in 2017 and enacted in January 2018.

← 8. The CoG is “the body of group of bodies that provide direct support and advice to Heads of Government and the Council of Minister, or Cabinet”. The CoG is mandated to ensure the consistency and prudency of government decisions and “to promote evidence-based, strategic and consistent policies”.

← 9. Article 83 of Organic Law no. 111-14 on the Regions, Article 80 of Organic Law no. 112-14 on the Prefectures and Provinces, and Article 78 of Organic Law no. 113-14 on the Municipalities.

← 10. SIGMA (Support for Improvement in Governance and Management) is a joint initiative of the OECD and the European Union.

← 11. Organic Law No. 130-13 made Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB) mandatory for all ministries and Organic Laws No. 111-12, No. 111-13 and No. 111-14 made gender-responsive planning mandatory at the local level.

← 12. A citizens’ budget is an online document prepared by the government designed to reach and be understood by a large a segment of the population in order to provide citizens with a simplified summary of the budget and enhance their participation, discussion and budget consultations (Petrie and Shields, 2010[61]).

← 13. In Egypt, the Citizen’s Budget “Your Right to Know Your Country’s Budget” is available in Arabic on the Ministry of Finance website for every fiscal year from 2014/2015 (Ministry of Finance in Egypt, 2021[56]). At the time of writing, the most recent Citizen’s Budget was for the 2021/2022 fiscal year.

← 14. In Jordan, the Citizen Guide to the Budget has been published in Arabic by the General Budget Department annually since 2011. Since 2016, it has been incorporated with the Budget In-Brief document (General Budget Department in Jordan, 2020[55]). At the time of writing, the most recent Citizen Guide to the Budget was for the 2022 year.

← 15. In Morocco, a Citizen’s Budget has been published in Arabic and French by the Ministry of Economy and Finance annually since 2012 (Ministry of Economy and Finance in Morocco, 2021[59]). At the time of writing, the most recent Citizen’s Budget was for the 2022 year.

← 16. In Tunisia, the Citizen’s Budget has been published annually since 2014 by the Ministry of Finance in French (Ministry of Finance in Tunisia, 2021[57]). At the time of writing, the most recent Citizen’s Budget was for the 2022 year.