[57] Amarante, V. (2022), “Fortalecimiento de los sistemas de protección social de la región: aprendizajes a partir de la pandemia de COVID-19”, Documentos de Proyectos, CEPAL, https://hdl.handle.net/11362/47830.

[51] Antiporta, D. and A. Bruni (2020), “Emerging mental health challenges, strategies, and opportunities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives from South American decision-makers”, Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, Vol. 44, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.26633/rpsp.2020.154.

[41] Arsenault, C. et al. (2022), “COVID-19 and resilience of healthcare systems in ten countries”, Nature Medicine 2022 5, pp. 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01750-1.

[29] Bermudi, P. et al. (2021), “Spatiotemporal ecological study of COVID-19 mortality in the city of São Paulo, Brazil: Shifting of the high mortality risk from areas with the best to those with the worst socio-economic conditions”, Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, Vol. 39, p. 101945, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101945.

[45] Bernabe-Ramirez, C. et al. (2022), “HOLA COVID-19 Study: Evaluating the Impact of Caring for Patients With COVID-19 on Cancer Care Delivery in Latin America”, JCO Global Oncology 8, https://doi.org/10.1200/go.21.00251.

[31] Bilal, U., T. Alfaro and A. Vives (2021), “COVID-19 and the worsening of health inequities in Santiago, Chile”, International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 50/3, pp. 1038-1040, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab007.

[50] Borges, F. et al. (2020), “Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in patient admission to a high-complexity cancer center in Southern Brasil”, Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, Vol. 66/10, pp. 1361-1365, https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.10.1361.

[35] Cabieses et al. (2020), “Migrantes venezolanos frente a la pandemia de COVID-19 en Chile: factores asociados a la percepción de sentirse preparado para enfrentarla”, Notas de Población, No. 111, CEPAL, https://hdl.handle.net/11362/46554.

[6] Carinci, F. et al. (2015), “Towards actionable international comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD framework and quality indicators”, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv004.

[44] CCSS (2020), Effects on health services, https://www.ccss.sa.cr/.

[64] CCSS (2020), Informe de resultados de la Evaluación de la Prestación de Servicios de Salud 2019 y monitoreo 2020, https://www.binasss.sa.cr/informeservicios2019.pdf.

[47] Chávez Amaya, C. (2021), Demanda asistencial de pacientes crónicos supera la capacidad de los servicios de salud | Ojo Público, Ojo Público, https://ojo-publico.com/3088/demanda-asistencial-de-pacientes-cronicos-supera-al-sistema-de-salud (accessed on 27 May 2022).

[65] Cho, M. and R. Levin (2022), “Implementación del plan de acción de recursos humanos en salud y la respuesta a la pandemia por la COVID-19”, Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, Vol. 46, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.26633/rpsp.2022.52.

[25] Di Gennaro, F. (ed.) (2021), “On the analysis of mortality risk factors for hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A data-driven study using the major Brazilian database”, PLOS ONE, Vol. 16/3, p. e0248580, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248580.

[55] Di Paolantonio, G. (2020), “Fostering resilience in the post-COVID-19 health systems of Latin America and the Caribbean”, in Shaping the COVID-19 Recovery: Ideas from OECD’s Generation Y and Z, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/about/civil-society/youth/Shaping-the-Covid-19-Recovery-Ideas-from-OECD-s-Generation-Y-and-Z.pdf.

[5] Donabedian, A. (1988), “The quality of care. How can it be assessed?”, JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 260/12, pp. 1743-1748, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.260.12.1743.

[13] Dong, E., H. Du and L. Gardner (2020), “An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time”, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Vol. 20/5, pp. 533-534, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30120-1.

[42] Doubova, S. et al. (2021), “Disruption in essential health services in Mexico during COVID-19: an interrupted time series analysis of health information system data”, BMJ global health, Vol. 6/9, https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2021-006204.

[3] ECLAC (2022), The sociodemographic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America and the Caribbean, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, https://hdl.handle.net/11362/47923.

[16] ECLAC (2021), “Estadísticas e indicadores”, CEPALSTAT Bases de Datos y Publicaciones Estadísticas, https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/dashboard.html?indicator_id=4409&area_id=2313&lang=es.

[59] ECLAC/CEPAL (2022), “Suriname”, in Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2022, CEPAL, https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/48078/10/ES2022_Suriname_en.pdf.

[28] ECLAC/PAHO (2021), The prolongation of the health crisis and its impact on health, the economy and social development, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, https://hdl.handle.net/11362/47302.

[24] Gebhard, C. et al. (2020), “Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe”, Biology of Sex Differences, Vol. 11/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9.

[2] Herrera, C. et al. (2022), Building Resilient Health Systems in Latin American and the Caribbean: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic, World Bank, Washington DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099805001182361842/P1782990d657460cb0a2080ac0048f8b98f.

[23] Huang, B. et al. (2021), “Sex-based clinical and immunological differences in COVID-19”, BMC Infectious Diseases, Vol. 21/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06313-2.

[22] IHME, 2021 (2021), Global Burden of Disease Study 2019, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Seattle, United States, https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

[60] IMF (2021), Database of Country Fiscal Measures in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Fiscal-Policies-Database-in-Response-to-COVID-19.

[43] INEI (2021), Perú: Enfermedads No Transmisibles y Transmisibles, 2020, https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1796/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

[37] Kuehn, B. (2021), “Despite Improvements, COVID-19’s Health Care Disruptions Persist”, JAMA, Vol. 325/23, p. 2335, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.9134.

[63] LeRouge, C. et al. (2019), “Health System Approaches Are Needed To Expand Telemedicine Use Across Nine Latin American Nations”, Health Affairs, Vol. 38/2, pp. 212-221, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05274.

[30] Macchia, A. et al. (2021), “COVID-19 among the inhabitants of the slums in the city of Buenos Aires: a population-based study”, BMJ Open, Vol. 11/1, p. e044592, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044592.

[66] Maier, C., L. Aiken and R. Busse (2017), “Nurses in advanced roles in primary care: Policy levers for implementation”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 98, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8756593-en.

[17] Mathieu, E. et al. (2021), “A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations”, Nature Human Behaviour, Vol. 5/7, pp. 947-953, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01122-8.

[34] Migration data portal (2022), Datos sobre migración relevantes para la pandemia de COVID-19, https://www.migrationdataportal.org/es/themes/datos-sobre-migracion-relevantes-para-la-pandemia-de-covid-19 (accessed on 4.08.2022).

[46] MINSA (2021), Boletín Epidemiológico del Perú 2021 - Volume 30-SE24, https://www.dge.gob.pe/epipublic/uploads/boletin/boletin_202124_23_145452.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

[21] Morgan, D. et al. (2020), “Excess mortality: Measuring the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 122, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c5dc0c50-en.

[52] Nepogodiev, D. et al. (2022), “Projecting COVID-19 disruption to elective surgery”, The Lancet, Vol. 399/10321, pp. 233-234, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02836-1.

[33] NU. CEPAL/German Agency for International Cooperation (2021), The impact of COVID-19 on indigenous peoples in Latin America (Abya Yala): Between invisibility and collective resistance, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, https://hdl.handle.net/11362/46698.

[58] OECD (2023), Inflation (CPI) (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/eee82e6e-en (accessed on 17 February 2023).

[38] OECD (2023), Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Resilient Health Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1e53cf80-en.

[18] OECD (2022), OECD Health Statistics, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

[39] OECD (2022), Primary Health Care for Resilient Health Systems in Latin America, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/743e6228-en.

[27] OECD (2021), Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ae3016b9-en.

[67] OECD (2021), Primary Health Care in Brazil, OECD Reviews of Health Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/120e170e-en.

[54] OECD (2020), “Flattening the COVID-19 peak: Containment and mitigation policies”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e96a4226-en.

[36] OECD (2020), SIGI 2020 Regional Report for Latin America and the Caribbean, Social Institutions and Gender Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cb7d45d1-en.

[69] OECD/The World Bank (2020), Health at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6089164f-en.

[62] OIT/ILO (2021), Respuestas de corto plazo a la COVID-19 y desafíos persistentes en los sistemas de salud de América Latina, Organización Internacional del Trabajo, https://www.ilo.org/lima/publicaciones/WCMS_768040/lang--es/index.htm.

[4] OPS/PAHO (2021), Resultados de salud desglosados por sexo en relación con la pandemia de COVID-19 en la Región de las Américas. De enero del 2020 a enero del 2021, Organización Panamericana de la Salud, https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/53603.

[15] Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (2022), , https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-containment-and-health-index (accessed on 1 August 2022).

[40] Pacheco, J. et al. (2021), “Gender disparities in access to care for time-sensitive conditions during COVID-19 pandemic in Chile”, BMC Public Health, Vol. 21/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11838-x.

[26] PAHO (2021), EU CARIFORUM Climate Change and Health Project, https://www.paho.org/en/eu-cariforum-climate-change-and-health-project.

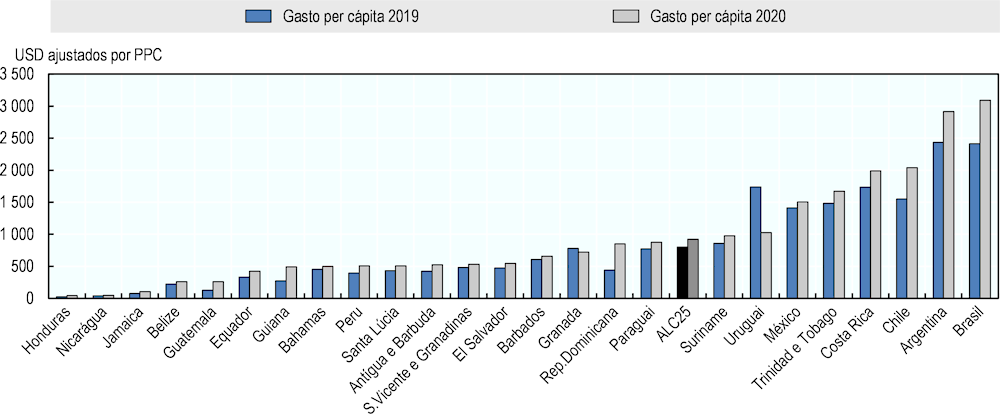

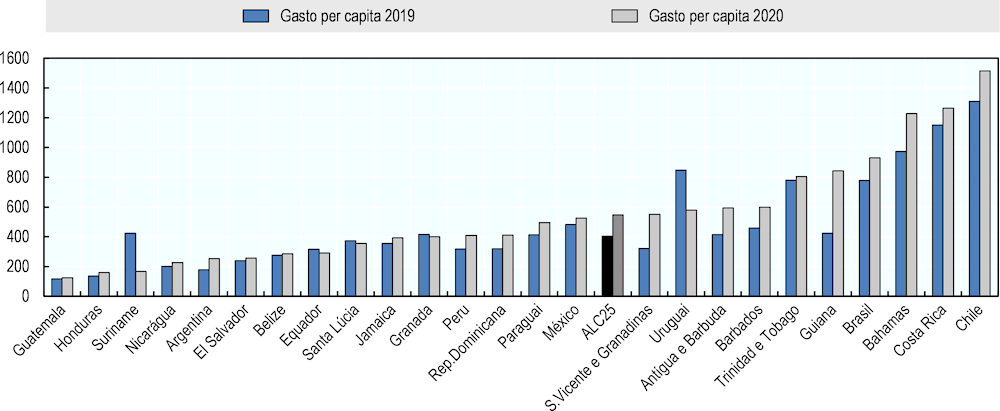

[56] Restrepo, J., D. Palacios and J. Espinal (2022), “Gasto en salud durante la pandemia por covid-19 en países de América Latina”, Grupo de Economía de la Salud, https://www.andi.com.co/Uploads/Documento%20de%20Trabajo%20Gasto%20en%20salud%20y%20covid-19.pdf.

[68] Ritchie, H. et al. (2020), Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19), https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

[49] Superintendencia de Salud (2022), Casos GES (AUGE) acumulados a diciembre de 2021 - Biblioteca digital. Superintendencia de Salud. Gobierno de Chile., https://www.supersalud.gob.cl/documentacion/666/w3-article-20904.html (accessed on 7 July 2022).

[32] SUS (2022), Open Data SUS, Sistema Único de Saúde, Brazil, https://opendatasus.saude.gov.br/dataset/srag-2021-e-2022.

[53] The Economist (2020), “Covid-19 Flattening the curve”, The Economist, Vol. Vol. 434/No. 9183 - It's going global.

[14] The University of Maryland Social Data Science Center & Facebook (2020), The University of Maryland Social Data Science Center Global COVID-19 Trends and Impact Survey, in partnership with Facebook, https://covidmap.umd.edu/ (accessed on 23 August 2022).

[12] The University of West Indies (2022), Climate Change and Health Leaders Fellowship Program, https://sta.uwi.edu/cchsrd/empowering-caribbean-action-climate-and-health-each.

[11] The World Bank group (2021), Covid-19 High-Frequency Monitoring Dashboard, https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2020/11/11/covid-19-high-frequency-monitoring-dashboard.

[19] UN (2022), World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results, https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022.

[20] Wang, H. et al. (2022), “Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–21”, The Lancet, Vol. 399/10334, pp. 1513-1536, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02796-3.

[7] WHO (2022), Global excess deaths associated with COVID-19 (modelled estimates), https://www.who.int/data/sets/global-excess-deaths-associated-with-covid-19-modelled-estimates.

[1] WHO (2022), Global tuberculosis report 2022, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/363752.

[8] WHO (2022), “Pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic”, World Health Organization, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/351527 (accessed on 4 July 2022).

[61] WHO (2021), Role of primary care in the COVID-19 response, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331921.

[9] WHO (2021), WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) detailed surveillance data dashboard, World Health Organization, https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYWRiZWVkNWUtNmM0Ni00MDAwLTljYWMtN2EwNTM3YjQzYmRmIiwidCI6ImY2MTBjMGI3LWJkMjQtNGIzOS04MTBiLTNkYzI4MGFmYjU5MCIsImMiOjh9.

[48] WHO (2020), Peru, https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/604-peru-fact-sheets.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

[10] WHO (2020), Vector-borne diseases, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases.