Abstract

The COVID-19 global health emergency and its economic and social impacts have disrupted nearly all aspects of life for all groups in society. People of different ages, however, are experiencing its effects in different ways.

For young people, and especially for vulnerable youth, the COVID-19 crisis poses considerable risks in the fields of education, employment, mental health and disposable income. Moreover, while youth and future generations will shoulder much of the long-term economic and social consequences of the crisis, their well-being may be superseded by short-term economic and equity considerations.

To avoid exacerbating intergenerational inequalities and to involve young people in building societal resilience, governments need to anticipate the impact of mitigation and recovery measures across different age groups, by applying effective governance mechanisms.

Based on survey findings from 90 youth organisations from 48 countries, this policy brief outlines practical measures governments can take to design inclusive and fair recovery measures that leave no one behind

To build back better for all generations, governments should consider

Applying a youth and intergenerational lens in crisis response and recovery measures across the public administration.

Updating national youth strategies in collaboration with youth stakeholders to translate political commitment into actionable programmes.

Partnering with national statistical offices and research institutes to gather disaggregated evidence on the impact of the crisis by age group to track inequalities and inform decision-making (in addition to other identity factors such as sex, educational and socio-economical background, and employment status).

Anticipating the distributional effects of rulemaking and the allocation of public resources across different age cohorts by using impact assessments and creating or strengthening institutions to monitor the consequences on today’s young and future generations.

Promoting age diversity in public consultations and state institutions to reflect the needs and concerns of different age cohorts in decision-making.

Leveraging young people’s current mobilisation in mitigating the crisis through existing mechanisms, tools and platforms (e.g. the use of digital tools and data) to build resilience in societies against future shocks and disasters.

Aligning short-term emergency responses with investments into long-term economic, social and environmental objectives to ensure the well-being of future generations.

Providing targeted policies and services for the most vulnerable youth populations, including young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs); young migrants; homeless youth; and young women, adolescents and children facing increased risks of domestic violence.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting every aspect of people's lives in an unprecedented manner. While many of its implications, such as confinement-related psychological distress and social distancing measures, affect all of society, different age groups experience these impacts in distinct ways. With the gradual transition of government responses from immediate crisis management to the implementation of recovery measures, several concerns are emerging, such as increasing levels of youth unemployment and the implications of rising debt for issues of intergenerational justice, as well as threats to the well-being of youth and future generations.

An inclusive response to and recovery from the crisis requires an integrated approach to public governance that anticipates the impact of response and recovery measures across different age cohorts. “Building better” requires decision makers to acknowledge generational divides and address them decisively in order to leave no one behind.

OECD evidence demonstrates that the pandemic has hit vulnerable groups disproportionally and is likely to exacerbate existing inequalities (see e.g. (OECD, 2020[1]), (OECD, 2020[2]) and (OECD, 2020[3])). This paper looks at the impact of the crisis on young people (aged 15-24)1 and across different age cohorts, as well as its implications for intergenerational solidarity and justice. For instance, young women and men already have less income at their disposal compared to previous young generations; they are 2.5 times more likely to be unemployed than people aged 25-64 (OECD, 2018[4]), and less than half of young people (45%) across the OECD countries express trust in government (Gallup, 2019[5]). Intersecting identity factors, such as sex, gender, race, ethnicity, and intellectual or physical disability, and socio-economic disadvantage may exacerbate the vulnerability of young people (e.g. homeless youth, young people not in employment, education or training (NEETs), young migrants). Governments must therefore seek to anticipate the impact of mitigation and recovery measures both within and across different age cohorts to avoid widening inequalities.

Economic and health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have been asymmetric across age groups. Current evidence suggests that young people are less at-risk in terms of developing severe physical health symptoms linked to COVID-19 than older age cohorts (WHO, 2020[6]). However, the disruption in their access to education and employment opportunities as a result of economic downturn is likely to put the young generation on a much more volatile trajectory in finding and maintaining quality jobs and income2. The 2007-2008 financial crisis already left youth shouldering a significant share of the social and economic consequences as the number of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) rose to 18% and the number of unemployed young people increased by 20%, leaving one in eight young people (aged 18-25) in poverty (OECD, 2019[7]).3 Being unemployed at a young age can have long-lasting “scarring effects”4 in terms of career paths and future earnings. Young people with a history of unemployment face fewer career development opportunities, lower wage levels, poorer prospects for better jobs, and ultimately lower pensions (OECD, 2016[8]). The economic effects of the pandemic risk aggravating the existing vulnerability of young people in labour markets, as they are more likely to work in non-standard employment, such as temporary or part-time work, facing a higher risk of job and income loss (OECD, 2019[9]). Young people also have limited financial assets, which puts those living in economically vulnerable households at an increased risk of falling below the poverty line within 3 months, should their income suddenly stop or decline (OECD, 2020[3]). These economic effects are likely to affect youth in various ways ranging from their access to housing to paying back school loans.

The disruptive nature of the COVID-19 pandemic puts the ability of governments to act decisively and effectively under the public spotlight. Difficult trade-offs concern the balancing of public health and economic considerations at the present time, and the allocation of large-scale economic stimulus packages across different sectors and beneficiaries. In the context of ageing populations, considerations about intergenerational solidarity and justice have been permeating debates on social, fiscal and environmental policy in different policy areas long before the pandemic struck. These considerations are likely to gain further traction, as the repercussions unfold over the coming months and years.

Making different voices in society heard, both younger and older, is critical to delivering a more inclusive response. For example, several OECD countries, including Estonia, Germany, Poland and Switzerland, have launched e-participation initiatives to engage citizens in the COVID-19 response and recovery efforts, while Italy established a multi-stakeholder task force to address the spread of disinformation linked to the pandemic (DW, 2020[10]) (E-Estonia, 2020[11]) (Polandin, 2020[12]). Some of these initiatives used open government data to inform, engage and innovate in collaboration with citizens (OECD, 2020[13]). Involving youth stakeholders from diverse backgrounds can rebuild trust, generate their interest in politics and integrate long-term considerations in crisis response and recovery strategies.

This policy brief draws on OECD’s work on youth empowerment and intergenerational justice mandated by the OECD Public Governance Committee and Regulatory Policy Committee and the findings of the OECD Global Report on Youth Empowerment and Intergenerational Justice (OECD, 2020[14]).

It presents the results from an online survey run by the OECD between 7-20 April 2020 with the participation of 90 youth-led organisations from 48 countries (see Annex 1.A). The policy brief is structured in three sections:

An assessment of the immediate, medium and long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people and vulnerable groups;

Elements for an integrated public governance approach for a fair and inclusive recovery and resilience; and

The role of young people as catalysts of inclusive and resilient societies in crisis response, recovery, and in preparation of future shocks.

1. The impact of COVID-19 on young people and vulnerable groups

Young people express concerns about the toll on mental health, employment, disposable income and education

While the trajectory of the pandemic varies across countries, most governments in OECD countries have implemented social distancing, confinement, and social isolation measures to contain the spread of the virus.

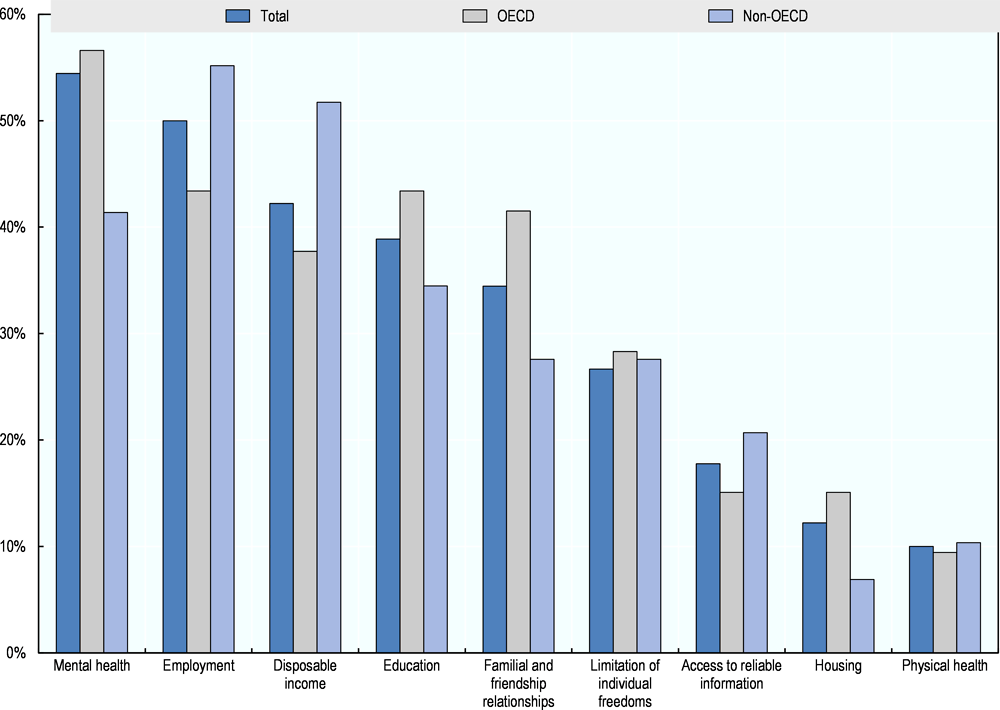

In this context, youth organisations expressed greatest concern about the impact of COVID-19 on mental well-being, employment, income loss, disruptions to education, familial relations and friendships, as well as a limitation to individual freedoms (Figure 1). A significant share of respondents also expressed concerns about access to reliable information (OECD, 2020)5.

Note: Respondents were asked to identify three aspects they find the most challenging to mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 crisis. "OECD" refers to the average response across 52 respondents based in OECD countries. "Non-OECD" refers to the average response across 29 respondents based in non-OECD countries. "Total" refers to the average response of all 90 respondents: these include respondents from OECD and non-OECD countries, as well as 9 international youth organisations, which are not separately shown in this figure.

Source: OECD Survey on COVID-19 and Youth.

Employment and disposable income

Low-paid and temporary employment in sectors most severely affected by the crisis (e.g. restaurants, hotels and gig industry) are often held by young people, who are now facing a higher risk of job and income loss. 35% of young people (aged 15-29) are employed in low-paid and insecure jobs on average across OECD, compared to 15% of middle-aged employees (30-50) and 16% of older workers (aged 51 and above) (OECD, 2019[9]). Evidence from the beginning of the crisis demonstrates that young people (15-24) were the group that was most affected by the rise in unemployment between February and March (OECD, 2020[15]). In the face of a loss or a drop in income, young people are more likely to fall into poverty, as they have fewer savings to fall back on (OECD, 2020[3]). In addition, as illustrated by previous economic shocks, young people graduating in times of crisis will find it more difficult to find decent jobs and income, which are likely to delay their path to financial independence.

More than a decade after the financial crisis, the youth unemployment rate across OECD countries remains above pre-crisis levels, demonstrating the long-lasting impacts that economic shocks have not only on the current youth cohort but also on future generations (OECD, 2020[3]). The economic shock caused by the Covid-19 crisis also risks compounding existing inequalities between young people. For instance, during the 2007-2008 financial crisis, young people with low levels of educational attainment (below upper-secondary) were hit the hardest by unemployment and inactivity, which persisted during the slow recovery (OECD, 2019[16]). Recent figures show that young people with no more than lower-secondary education are three times more likely to be NEET compared to those with a university degree (OECD, 2019[16]), which, in turn, takes a toll on future employment prospects and earnings (OECD, 2015[17]).

Disruptions in access to education

The closure of schools and universities has affected more than 1.5 billion children and youth worldwide and has significantly changed how youth and children live and learn during the pandemic (UN, 2020[18]). Some of the innovative teaching and learning tools and delivery systems schools and teachers experimented with in response to the crisis may have a long-lasting impact on education systems. On the other hand, OECD evidence shows that every week of school closure implies a loss in the development of human capital with significant long-term economic and social implications (OECD, 2020[19]).

Despite the flexibility and commitment shown by schools and teachers in securing educational continuity during school closures, not all students have been able to consistently access education. An OECD study across 59 countries demonstrates that although most countries put in place alternative learning opportunities, just about half of the students were able to access all or most of the curriculum (OECD, 2020[20]). The learning loss that has occurred is likely to take an economic toll on societies in the form of diminished productivity and growth. OECD estimates show that a lost school year can be considered equivalent to a loss of between 7% and 10% of lifetime income (OECD, 2020[20]).

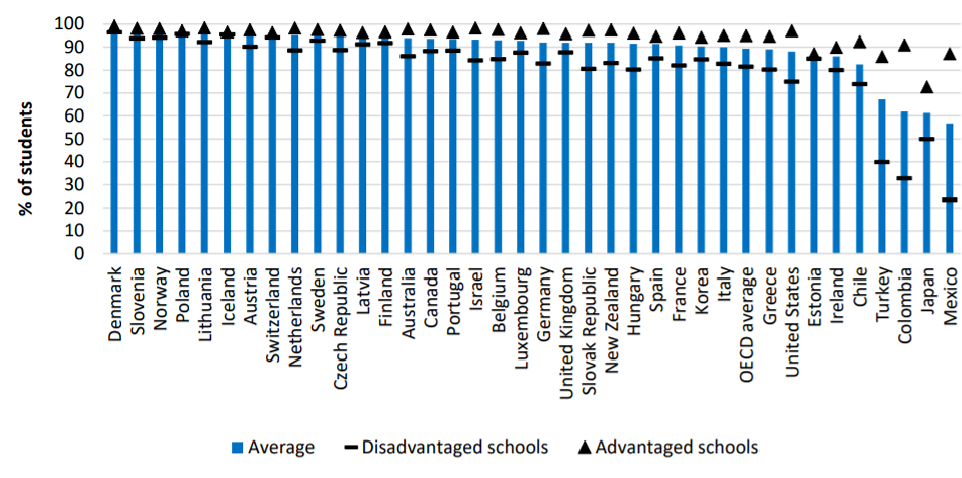

In the context of school closures, the quality of the home learning environment becomes even more important. A digital divide in connectivity and access to electronic devices risks further amplifying inequalities among young people during the pandemic. For instance, students from less well-off families are less likely to have access to digital learning resources and parental support for home learning (OECD, 2020[2]). Across OECD countries, more than one in ten 15-year olds from socio-economically disadvantaged schools do not have a quiet space to study at home nor an internet connection. One in five do not have access to a computer for schoolwork (OECD, 2020[21]) (Figure 2).

Note: Socio-economically disadvantaged (advantaged) school is a school whose socio-economic profile (i.e. the average socio-economic status of the students in the school) is in the bottom (top) quarter of the PISA index of economic, social and cultural status amongst all schools in the relevant country/economy.

Source: OECD (2020), “Learning remotely when schools close: How well are students and schools prepared? Insights from PISA”, www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/.

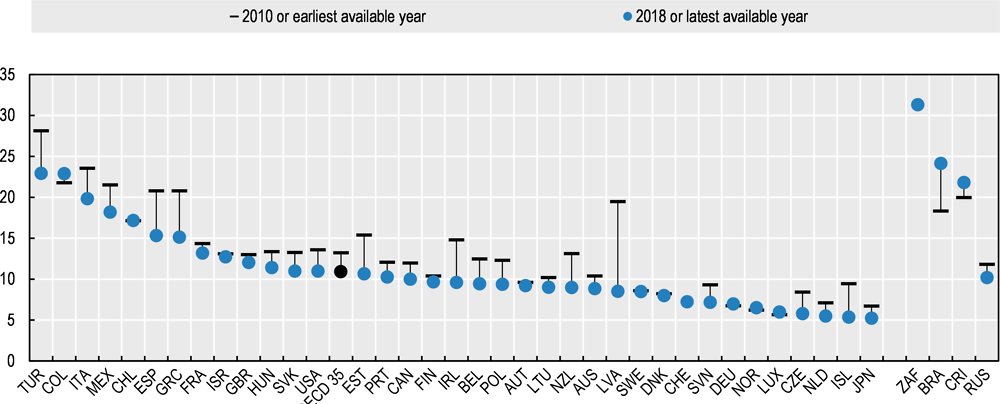

Lack of physical learning opportunities and economic distress are increasing the risk of disengagement and dropout from education and training. Already prior to the crisis, 1 in 10 youth aged 15-24 years on average across OECD was not in education, employment or training (Figure 3), which represents a major economic cost equivalent to between 0.9% and 1.5% of OECD GDP (OECD, 2020[3]). School closures have a more significant impact on the well-being of vulnerable youth, in particular for youth with special educational needs (e.g. disabled people) and those relying on the social and emotional support services provided by schools, as well as school meals for a reliable source of daily nutrition (OECD, 2020[22]).

Note: The OECD average excludes Korea and Switzerland due to incomplete time series.

Source: OECD (2020), How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

Toll on mental health

The findings from the OECD survey also confirm significant psychological impacts of social distancing and quarantine measures on young people causing stress, anxiety and loneliness. This is also affirmed by the findings of studies conducted in the UK (Etheridge B., Spanting L., 2020[23]) and the US (McGinty EE et al., 2020[24]) showing that young adults (aged 18 to 29) experience higher level of distress compared to other age groups since the onset of the pandemic.

Evidence from previous pandemics suggests that exposure to domestic violence increases during lockdown measures, leaving adolescents, children and women vulnerable to violence by family members and intimate partners with long-lasting psychological impacts (OECD, 2020[1]). For instance, 55 percent of children interviewed reported increased violence during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014 (UN, 2020[18]). Since the outbreak of COVID-19, online enquiries to violence prevention hotlines have risen up to 5 times while emergency calls reporting domestic violence against women and children have increased by 60% compared to the same period of the previous year in Europe according to the WHO (WHO, 2020[6]).

The closure of schools affects students’ mental well-being as teachers and classmates can provide social and emotional support. Education professionals also play an important role in helping detect and report abuse against children (Campbell, 2020[25]). In addition, the postponement or cancellation of exams in around 70 countries, including high-stake final school exams, exposes youth and children to uncertainty, anxiety and stress (UN, 2020[18]).

The impact of the crisis on the psycho-social and subjective well-being of young people also depends on the household they live in and individual circumstances such as prospects of job and income losses; housing quality; the illness or loss of loved ones; and the presence of existing medical conditions and vulnerable persons in the household (OECD, 2020[3]).

Prospects for future well-being, international co-operation and solidarity are major concerns in the long-run

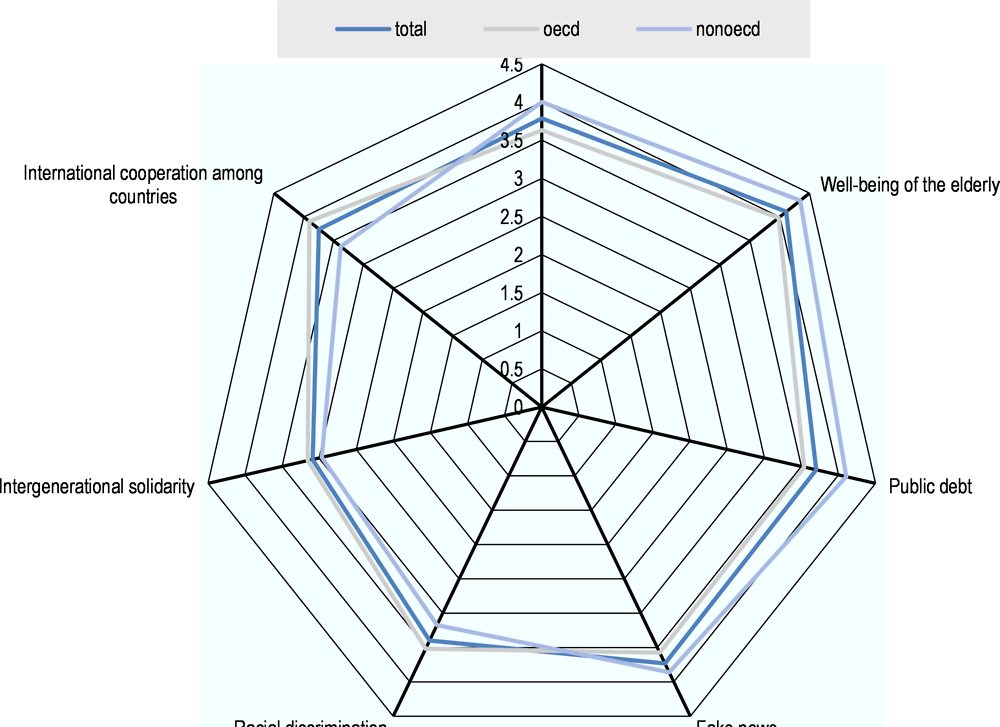

When asked about the long-term implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, surveyed youth-led organisations from OECD countries expressed greatest concerns about the well-being of the elderly. This was followed by negative prospects for international co-operation, the well-being of youth, the spread of disinformation (fake news), increasing levels of public debt and racial discrimination and, to a somewhat lesser extent, intergenerational solidarity. A similar picture emerges when the views of youth-led organisations in non-OECD countries are considered (Figure 4).

The findings of the OECD policy brief on disinformation about COVID-19 reaffirm these concerns (OECD, 2020[26]). Evidence across ten countries6 in early March 2020 shows that half of citizens found it hard to obtain reliable information about the virus, pointing to the lack of timely and trustworthy information (Edelman, 2020[27]). Youth are more likely to use social media as their main source of news, which, according to a recent study, accounts for 88% of the misinformation related to the pandemic (Brennen, 2020[28]). This increases the likelihood of young people to be exposed to disinformation, while also raising fears and undermining trust.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, the number of reported cases of racism and discrimination targeting people from different origins has increased (UNESCO, 2020[29]). Survey findings suggest that young people are concerned about racial stigma and widespread disinformation associated with the COVID-19 pandemic to persist in the long-term. Some of the initiatives led by young people (see Section 3) tackle these challenges by disseminating information and providing support to the most vulnerable and marginalised groups, including minorities, indigenous communities and migrants.

Note: Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which your organisation is worried about the long-term impact of the COVID-19 crisis, on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is not worried at all and 5 is very worried. "OECD" refers to the average response across 52 respondents based in OECD countries. "Non-OECD" refers to the average response across 29 respondents based in non-OECD countries. "Total" refers to the average response of all 90 respondents: these include respondents from OECD and non-OECD countries, as well as 9 international youth organisations, which are not separately shown in this figure.

Source: OECD Survey on COVID-19 and Youth.

As shown in Figure 4, a large majority of young people also express concerns about public debt levels. According to the IMF, countries around the world have approved more than USD 4.5 trillion worth of emergency measures as of early April (BBC, 2020[30]). Across the OECD, fiscal stimulus packages are estimated to amount to up to 20% of GDP in some countries in mid-April (Elgin, C. et al., 2020[31]). Across 33 OECD countries, the average general government gross debt is projected to reach between 128% of GDP (single-hit scenario) and 137% of GDP (double-hit scenario) in 2021, compared to 110% of GDP in 2019 (OECD, 2020[32]). The scale of fiscal policy measures is likely to create long-lasting effects on society and the economy, which brings questions of intergenerational justice to the forefront. In the context of ageing societies, increasing public debt levels due to the COVID-19 crisis may further exacerbate existing challenges to sustainable public finances (Rouzet et al., 2019[33]). This raises questions about the distributional impact of decisions and choices made today and whether the costs associated with mitigation and recovery measures will be allocated fairly across society and generations.

2. Governance responses to build back better and deliver for all generations

Trust in governments and their response to the pandemic

Despite a gradual lifting of confinement measures across most OECD countries recently, changes in everyday behaviour will still be crucial in the coming months to avoid new waves of infections. Building trust among young people remains crucial to create buy-in and determine the success of response and recovery measures in the long-term. The forthcoming OECD Global Report on Youth Empowerment and Intergenerational Justice (OECD, 2020[14]) demonstrates that public governance is instrumental in building trust among young people, supporting their transition to an autonomous life, strengthening their relationship with public institutions, and ensuring intergenerational justice. Indeed, OECD evidence shows that public governance measures that promote, among others, principles of transparency, integrity, accountability and stakeholder participation are strong predictors of trust in institutions ( (OECD, 2017[34]); (OECD, 2017[35])). In the context of COVID-19, these principles are preconditions to build back better.

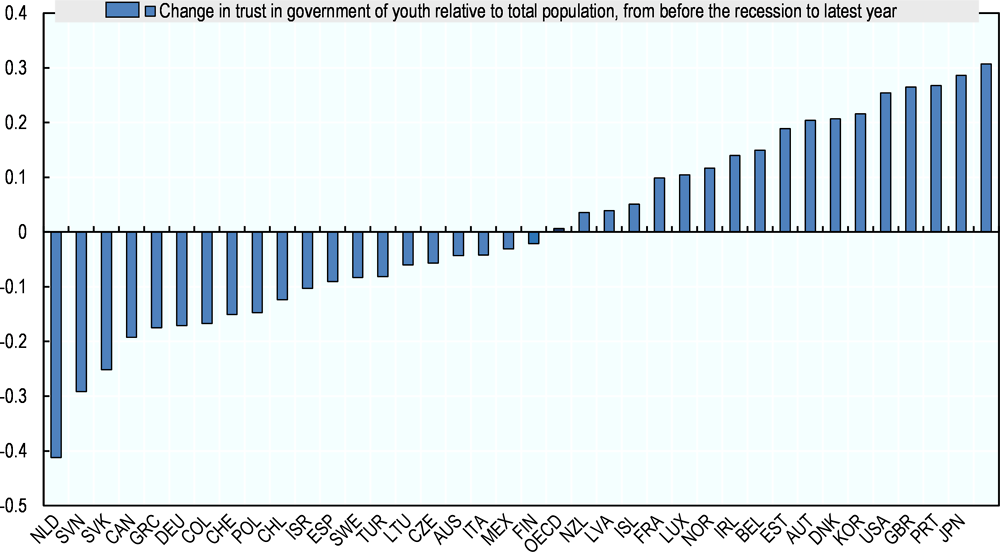

After a general deterioration in the aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, trust in public institutions has barely recovered over the last decade. In 2019, less than half of the OECD population (43%) trusted their national government (OECD, 2020[3]). The erosion of trust has been especially significant among young people. In 2018, young people reported the lowest level of trust in national governments compared to middle-aged and elderly citizens in most OECD countries for which data is available (OECD, 2019[36]). Furthermore, in more than half of the OECD countries (20 out of 37), the trust expressed by young people in national governments, compared to the total population, has decreased since 2006 (Figure 5). While the financial crisis differs in numerous ways from the COVID-19 crisis, lessons learnt in the past can provide important insights to design recovery measures that do not leave young people behind.

“Youth” here refers to people aged 15-29. Age-disaggregated data across years is not available for Iceland.

OECD calculations based on Gallup World Poll (Database).

In the current context, people’s trust in government as well as their confidence in the government’s ability to handle and recover from the outbreak are particularly volatile. For instance, survey data presented by the European Parliament on 27 April 2020 (European Parliament, 2020[37]) shows that support for government measures remains high in a majority of polled countries although there are some declines, especially as citizens’ concerns are shifting from more immediate health concerns to worries about the financial and economic impacts of the crisis. A recent study for the G7 countries (conducted on 9-13 April) also highlights such volatility by reporting significant changes in trust levels when comparing results to a survey conducted one month earlier (Kantar, 2020[38]).

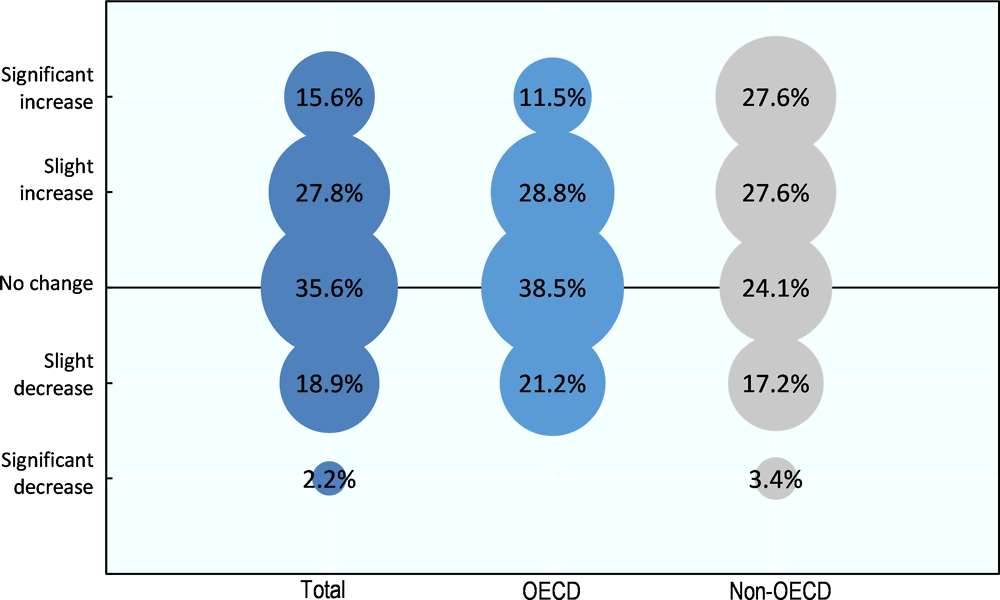

Snapshot data from the OECD Survey, conducted on 7-20 April, shows that, on aggregate, trust in government has increased since the outbreak of COVID-19 for 43% of the youth organisations surveyed worldwide. Trust has remained stable for 36% of them, whereas it has decreased for 21%. While on aggregate most youth organisations have expressed higher (or unchanged) levels of trust in government, this varies significantly across countries. For instance, while 40% of youth organisations based in OECD countries reported an increase in trust, the figure was 55% for those based in non-OECD countries (Figure 6). The figure also shows that trust in government did not change for 38% of youth organisations in OECD countries, neither positively nor negatively.

Note: "OECD" refers to the average response across 52 respondents based in OECD countries. "Non-OECD" refers to the average response across 29 respondents based in non-OECD countries. "Total" refers to the average response of all 90 respondents: these include respondents from OECD and non-OECD countries, as well as 9 international youth organisations, which are not separately shown in this figure.

Source: OECD Survey on COVID-19 and Youth

There is no straightforward explanation for the recorded differences in trust levels across OECD member and non-member countries, with some intervening factors being countries’ different exposure to the crisis itself and people’s different expectations regarding the role of government. Work on the drivers of trust further points to effective public institutions, policy outcomes, and government’s ability to deliver on the needs of their citizens as potential explanations for changes in trust (Bouckaert, 2012[39]).

In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, governments have taken a variety of immediate response measures to mitigate the effects for young people, such as by collecting age-disaggregated evidence and creating volunteering platforms to leverage the support of the youth sector (Box 1).

New Zealand’s Ministry of Youth Development has conducted surveys with children and youth under state care to understand how they were coping in confinement to guide the interventions of social workers. The UK National Youth Agency has published a report highlighting how the pandemic is amplifying existing vulnerabilities among young people as well as providing suggestions on the role of youth work in the current context.

In numerous countries, including Germany, Ireland, Portugal and the UK, governments have provided and disseminated practical advice for parents as well as children and young people on how to cope at home during confinement. The Irish Government, for instance, has provided practical advice including suggestions of online and offline activities that children and young people can do at home. Similarly, the Portuguese Institute of Sports and Youth has provided information, videos, trainings, and webinars to keep youth active at home.

In Germany and other countries, governments launched initiatives via their social media accounts to raise awareness for the importance of protecting particularly vulnerable groups, such as older people and people with pre-existing conditions, given the asymmetric exposure to health risks across age groups. The initiative explicitly calls for solidarity from all generations.

Around the world, young people have stepped up to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. Governments have also promoted youth volunteering at this critical time through dedicated programmes. The French government, for instance, has created a national volunteering platform called “Je veux aider” focused on urgent distribution of food and hygienic products, exceptional childcare for health staff, maintenance of social relationships with isolated elderly, and practical help for fragile neighbours. The Canadian government has also established a similar platform dedicated to COVID-19 volunteering called “I Want to Volunteer.” New Zealand has established a network with major youth organisations to strengthen collaboration for responding to COVID-19 more effectively. Youth workers have also continued to provide support to vulnerable youth in innovative (and often digital) ways. Governments, such as in the UK, have supported youth workers’ safety, for instance, through practical guidelines and tips.

Sources:https://nya.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Out-of-Sight-COVID-19-report-Web-version.pdf; https://ipdj.gov.pt/enquadramento; https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-supporting-children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-and-wellbeing; https://covid19.reserve-civique.gouv.fr/; https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/606da7-coping-at-home-during-covid-19/; https://volunteer.ca/index.php?MenuItemID=420; https://youthworksupport.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Covid-19-Youth-Workers-final1.pdf; https://twitter.com/BMFSFJ/status/1240592699142651904

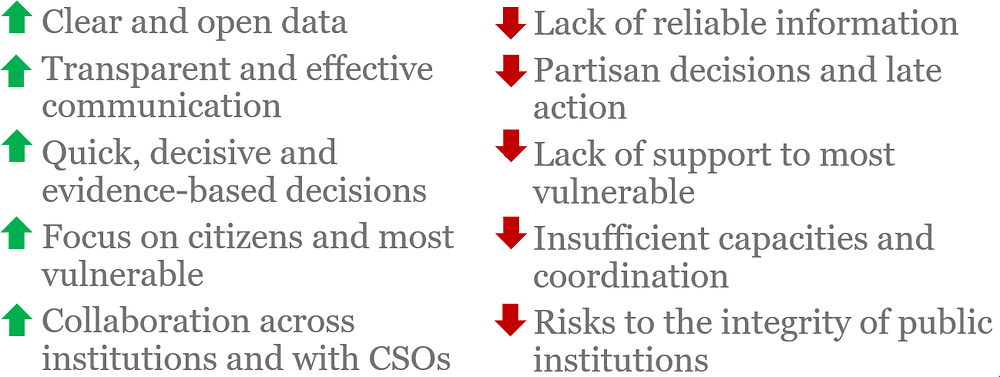

The way in which governments have responded has been a driver of trust, both positively and negatively (OECD, 2017[35]; OECD, 2020[14]). In line with the OECD Trust Framework (OECD, 2017[35]), the elements highlighted by survey respondents point to the importance of government’s responsiveness (e.g. ensuring access to public services during the pandemic through digital means among others) and reliability (e.g. emergency measures based on evidence (see Figure 7). The significance of integrity, openness (e.g. the provision of clear and open data), and fairness (e.g. support to the most vulnerable) were also reported frequently by respondents.

Notes: “CSOs” refers to civil society organisations. The elements highlighted in the figure summarise answers of survey respondents to an open question asking them to motivate the change in trust in government that they reported.

Source: OECD Survey on COVID-19 and Youth

Public governance for a fair recovery and resilience

Government plans and strategies to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic will mobilise considerable resources, while also creating long-lasting effects on society and the economy (see Section 1). In this context, governments have the opportunity to “build back better” from the crisis and reinforce trust by ensuring that recovery plans not only address the fallouts of the crisis, but also take into account the well-being of current and future generations.

The rule making function and fiscal and budgetary measures are powerful levers at the disposal of governments to ensure no-one is left behind.

Government-wide commitment for intergenerational justice

Some countries have already made commitments to include considerations on fairness and inclusiveness in measures to recover from the COVID-19 crisis. For instance, climate and environmental ministers from European Union’s countries,7 as well as members of the European Parliament,8 have called for making environmental improvements an integral part of the long-term recovery strategy of the EU. Commitments to intergenerational justice need to be anchored within government structures, tools and institutions that are independent of short-term considerations. For instance, the Next Generation EU plan proposed by the European Commission (EC, 2020[40]) outlines a green path out of the COVID-19 crisis by integrating the European Green Deal in the recovery and by reinforcing the Just Transition Fund, both of which explicitly highlight the importance of intergenerational justice. As another example, in the United Kingdom, the Welsh government has adopted a framework (Welsh government, 2020[41]), collecting general principles against which recovery measures will be evaluated. This framework includes principles of intergenerational justice through a reference to the Future Generations Act (2015), which is mandated to mainstream intergenerational and long-term considerations across the work of public bodies in Wales.

Strategic vision

Around three out of four OECD countries have adopted national youth strategies to shape a vision for youth and deliver youth programmes and services in a coherent manner across administrative boundaries. For instance, Canada, Greece, New Zealand, and Slovenia have operational national youth strategies that already cover aspects of youth resilience at the individual as well societal level. These strategies can now be leveraged to mobilise resources and run targeted programmes. For instance, the Office of the Republic of Slovenia for Youth has conducted online surveys on the activities run by Slovenian youth organisations to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis and to monitor developments in the digital youth work sector (Office of the Republic of Slovenia for Youth, 2020[42]).

At the same time, governments are likely to adjust numerous sectoral plans, from strategies covering public services (such as transportation, social services, urban planning etc.) to plans covering economic sectors (such as the agricultural and tourism sectors). This provides a large window of opportunity for policymakers to integrate a stronger focus on young people and future generations in government action across sectors. Youth and intergenerational considerations could also be mainstreamed in governments’ strategies for the economic response to COVID-19. For instance, Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan (2020[43]) includes measures to help youth receive emergency income benefits, develop their skills, gain professional experience, and contribute to their communities through volunteering within the current context.

Tools to deliver for all generations

The availability of age-disaggregated evidence is critical to assess the impact that COVID-19 has on the well-being of different age groups (OECD, 2020[14]). For instance, Austria, France, Germany and New Zealand can leverage existing “youth checks” to conduct ex-ante assessments of the likely impact of recovery measures on young people, and promote inclusivity in policy outcomes. Countries can also leverage existing sustainability impact assessments. For example, the Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) framework in Switzerland aims at incorporating intergenerational considerations of environmental, social and economic sustainability into laws, action plans and public projects. Where thorough ex-ante assessments are not applied, governments could include sunset clauses and obligatory review clauses in recovery measures and regulations (OECD, 2020[44]).

In Canada, the government is examining how government spending and policies, including the emergency aid and recovery measures for the COVID-19 crisis, will affect women and men differently through the lenses of its Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) framework (Wright, 2020[45]). The framework is used to assess the impact of policies and programmes across social groups, acknowledging intersecting identity factors such as gender and age. Beyond ex-ante assessments of measures, age-disaggregated evidence and indicators will also be necessary to track progress in the recovery phase in order to avoid widening gaps across generations.

Governance tools can also help in allocating public resources for recovery in a fair manner across generations. For instance, New Zealand's Living Standard Framework ([46]) is concerned about policy impacts across different dimensions of well-being, as well as the long-term and distributional implications across age groups, sexes, and population groups from different socio-economic backgrounds. The Living Standard Framework has been integrated holistically in governance structures, which has resulted in the first-ever national budget built around well-being priorities in 2019.

Governments can also apply an intergenerational lens to the COVID-19 recovery measures through national budgeting, performance reporting, and fiscal sustainability analysis more widely, also leveraging the expertise present in independent fiscal institutions (IFIs) (OECD, 2014[47]).9 For instance, the Slovak Council for Budget Responsibility (CBR) considers intergenerational justice in connection with the long-term sustainability of public finances (OECD, 2017[48]). Korea’s National Assembly Budget Office produces analysis of how fiscal burdens associated with its baseline projection are distributed among different generations using generational accounting techniques (OECD, 2017[48]). As countries are mobilising significant financial resources in response to the crisis, restoring the sustainability of public finances will become a necessity in the medium- to long-term.

Institutional co-ordination to put words into action

A few OECD countries have established dedicated institutions to monitor the performance of governments in delivering on intergenerational justice. The main objective of these institutions is to address short-termism in politics and shed light on how government action affects the well-being of today’s young and future generations. Although significant differences exist with regard to their level of independence, specific functions and enforcement mechanisms, they can play an important role as governments are planning for recovery and analysing the lessons from COVID-19. Institutions such as the Committee for the Future in Finland, the Parliamentary Advisory Council for Sustainable Development in Germany and the Future Generations Commissioner in Wales, among others, play an important role in scrutinising government action and increasing public awareness about the compliance of government action with intergenerational and other sustainability commitments.

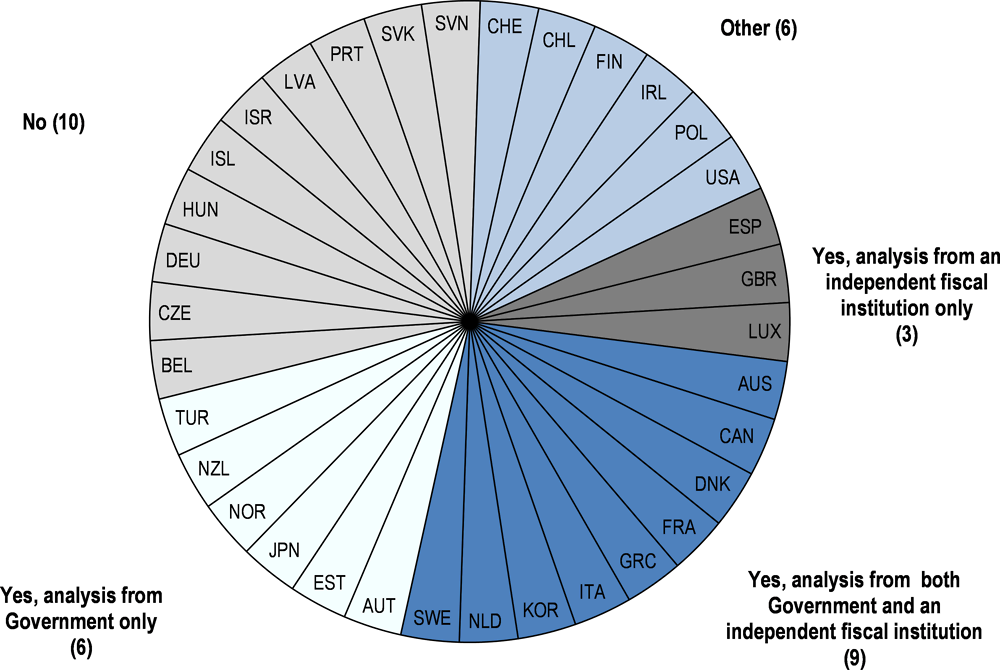

Similarly, governments can use analysis from IFIs that have integrated age-differentiated lenses in the analysis of the fiscal sustainability of recovery measures, such as those mentioned above, following the OECD (OECD, 2014[47]) Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Independent Fiscal Institutions. This is an area in which substantial progress remains to be done: as of 2019, only nine OECD countries systematically debated long-term sustainability analyses prepared by both the government and the IFI (Figure 8). Finally, governments can co-ordinate with existing audit and regulatory oversight institutions to build up the capacity to monitor, report, and evaluate the implementation of the recovery measures (and their impact on youth) in a transparent way, hence also limiting risks to public sector integrity.

Notes: In Finland the parliament receives long-term sustainability analysis from government and can also ask the IFI for additional long-term analysis if it wishes. While the Latvian Fiscal Discipline Council is not required to produce long-term sustainability analysis, it is beginning to undertake this type of analysis at its own initiative. Data for Colombia and Mexico are not available; Information on data for Israel: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2018), OECD PBO Network Survey on Parliamentary Budgeting Practices, Question 4, OECD, Paris

Inclusive decision-making

The outbreak of the pandemic has been matched by an increase in solidarity in the form of volunteering, especially among young people. In the UK, for instance, the Guardian recently reported that around 750,000 people signed-up to the National Healthcare Service volunteer scheme, and another estimated 250,000 joined local volunteer centres (Butler, 2020[49]). In this context, governments have the opportunity to harness young people’s sense of agency by engaging them in the formulation, co-creation and/or implementation of policy responses and recovery plans. Numerous governments have promoted digital initiatives to engage (younger) citizens in the government’s COVID-19 response and recovery efforts, for instance in the form of virtual hackathons (Box 2). Some government officials, such as the Prime Minister of the Netherlands, have recently committed to involving children, young people, and youth organisations in the design of recovery measures (Pieters, 2020[50]). Moreover, at the political level, the African Union Youth Envoy convened 12 virtual consultations with youth leaders from 40 African countries to amplify youth-led initiatives and consult young people for the recovery phase (2020[51]). The African Union has also launched the African Youth Front on Coronavirus, an African Union framework to engage youth in decision-making for recovery (2020[52]).

National governments of, among others, Germany, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland and Switzerland have organised or supported virtual hackathons to involve citizens in generating innovative ideas for how to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. For example, about 28,000 people participated in the German government's #WirVsVirus (We Vs. Virus) hackathon from March 20 to March 22, presenting ideas to use electronic means to spread information and slow the spread of COVID-19. In Estonia, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications launched a fully online hackathon on March 13: over the following 48 hours, more than 1,000 innovators had contributed to Hack the Crisis. A similar Hack the Crisis online event was organised in Lithuania: the government committed to some of the projects presented at the event within their COVID-19 response. Similarly, the Polish governmental technology agency GovTech Polska organised a three-day hackathon (April 3-5) to collect new ideas on promoting security, business, science, e-commerce, education and leisure during the pandemic.

Governments can also set up mechanisms that bring youth, adults and elderly together in intergenerational dialogues to enhance more inclusive and longer time-frames in decision-making, for instance by leveraging existing bodies. According to preliminary evidence from the OECD Global Report on Youth Empowerment and Intergenerational Justice (OECD, 2020[14]), national youth councils exist in 25 OECD countries. Youth councils at subnational level are more common, as they are present in 27 OECD countries. Several OECD countries (17) have national youth advisory councils affiliated to the government or specific ministries. In Slovenia, for instance, national and municipal authorities are obliged by law to inform the Youth Council about draft regulations that will affect the life and work of young people.

Government strategies and youth resilience

The COVID-19 crisis has proven that youth workers, youth organisations as well as non-organised youth can be partners in providing support to people’s well-being, especially for vulnerable groups and for people that are unlikely to be aware of relevant government services and support. It is critical for governments to capture, retain and build on current youth mobilisation to strengthen society’s resilience and readiness for future shocks.

National youth volunteering programmes and strategies that allocate clear responsibilities, provide capacity building opportunities, as well as adequate financial resources can help in keeping youth mobilised for their communities. According to preliminary data from the OECD Global Report on Youth Empowerment and Intergenerational Justice (OECD, 2020[14]), almost 7 out of 10 OECD countries have such programmes in place (68%). Preliminary analysis also confirms that in countries with a youth volunteering programme, young people are in fact more likely to volunteer. In a similar way, youth workers that engage young people (especially vulnerable groups) in non-formal education and out-of-school activities can be mobilised by governments in building up youth’s resilience. Currently, less than half of OECD countries (44%) for which preliminary data is available (OECD, 2020[14]) have youth work strategies in place. Governments should adapt existing strategies and formulate new ones to ensure that the youth work sector is ready to deal with the fallouts of the COVID-19 crisis and address emerging areas such as digital youth work.

3. Youth as catalysts of inclusive and resilient societies

Youth organisations and their role in mitigating the disruptions of the crisis

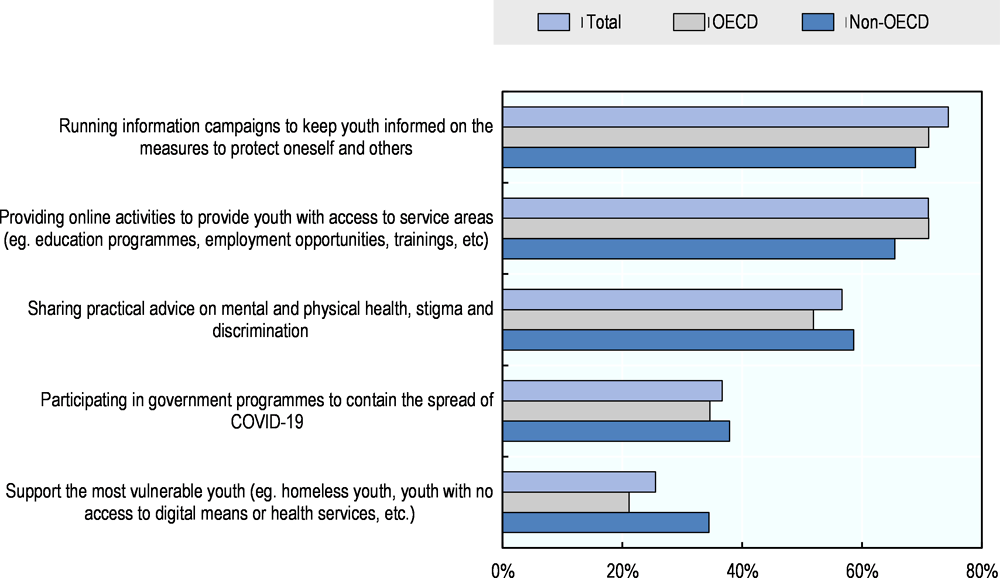

Youth organisations have swiftly stepped in to disseminate information among their peers and help contain the spread of the virus. They also provided access to educational, peer-to-peer mental health advice and other programmes to support adolescents and young adults in confinement. New initiatives have focused on providing support to the elderly and other groups at increased risk of becoming infected, and by combatting stigma and discrimination (Figure 9). These initiatives have been crucial to mitigate the closure of schools and support services, addressing loneliness and anxiety, and promoting social cohesion.

Note: "OECD" refers to the average response across 52 respondents based in OECD countries. "Non-OECD" refers to the average response across 29 respondents based in non-OECD countries. "Total" refers to the average response of all 90 respondents: these include respondents from OECD and non-OECD countries, as well as 9 international youth organisations, which are not separately shown in this figure.

Source: OECD Survey on COVID-19 and Youth, launched in April 2020.

Figure 9 illustrates the kind of support provided by youth-led organisations based on the survey findings. Around three in four organisations have created online campaigns to keep young members informed on the measures to protect themselves and others. More than half of organisations have turned to digital and online tools to provide practical advice to young people on how to deal with mental and physical health, stigma and discrimination.

For instance, to combat false information in the wake of the crisis, youth organisations launched the international campaign #youthagainstcovid19 to map and share myth-busting, fact-checking websites and resources. Similar campaigns were launched at national level such as #QuédateEnCasa in Mexico.

In Denmark, youth-led organisations have collaborated with the national government in mitigating the crisis through the initiative “What can youth do under COVID-19” (Danish Youth Council, 2020[53]) and in Romania, youth have collaborated with government in the “Do not isolate yourself from education!” (National Alliance of Student Organisations, 2020[54]) campaign. These initiatives provide practical advice for young people on how to cope with working and studying from home, and disseminated guidelines for conducting online meetings. Youth organisations in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have used digital tools to engage young people in dialogue sessions and in skilling up youth during confinement. The “Youth & Smart Confinement” (European Association for Local Democracy, 2020[55]) initiative in Morocco has organised regular webinars on social media to discuss topics such as “Art & Confinement” and “What are the best uses of digital tools” to keep youth socially engaged. In Tunisia, the International Organization for Youth Development has organised an online course for young people to acquire entrepreneurial skills from home (2020[56]).

Youth organisations have also been pivotal in ensuring the continuity of day-to-day activities, especially for vulnerable groups. For instance, the Italian youth-led NGO “Nous” disseminated videos in different languages to inform individuals facing language barriers about the measures taken by government (Nous, 2020[57]). Numerous organisations have launched initiatives to support the elderly during the crisis through volunteering campaigns to shop for basic needs, groceries or medication, such as the “Neighbourhood Watch” (Hayat Center for Civil Society Development (RASED), 2020[58]) and “Nahno” (2020[59]) in Jordan. A programme to help combat loneliness of the elderly was established in the Netherlands with the “Youth Impact” (Dutch National Youth Council, 2020[60]) campaign, which connects younger and older generations through online platforms and phone calls.10

Brick by brick: Partnerships between youth and governments in recovery measures

Youth-led organisations have also been active in building for recovery, sometimes in partnership with government. For instance, the Finnish National Youth Council published “7 goals to keep young people involved” (2020[61]) to strengthen the youth sector by ensuring health services for all ages, training and employment support on a temporary basis. The Finnish Council has also organised online press briefings targeting government officials to inform them on how to best support youth-led organisations amid the crisis (2020[61]).

Within the framework of the Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth (DJY), the European Youth Forum (EYF) has launched a survey targeting young people worldwide about how the COVID-19 outbreak has impacted their lives. The results of the survey aim to amplify the voices of young people.

The global initiative “Youth Speak” (AIESEC Portugal, 2020[62]) and the Appeal Paper (National Youth Council of Ukraine, 2020[63]) in Ukraine, provide online platforms that enable youth to inform decision-making in matters that concern them, and to ensure that organisations and centres within their communities, which provide activities and programmes to the public, are supported by governments.

The International Youth Foundation (IYF) has launched the “Global Youth Resiliency Fund” to financially support initiatives from local and national youth organisations that aim at protecting human rights, unlocking access to livelihoods, and expanding access to reliable information (2020[64]). In the MENA region, Project DAAM (Research, Advocacy and Capacity) is providing research grants for papers on the impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable people, with a particular focus on youth (2020[65]).

Preparing for future shocks: Strengthening resilience and antifragility measures with youth

Young people born between 1990 and 2005 have already experienced two major global shocks within the first 15-30 years of their life – the financial crisis 2008/09 and the COVID-19 pandemic, that either affected them directly (for example, as a student or job seeker) or indirectly (e.g. through the repercussions of the crises on their family). The exposure to such shocks has long-lasting consequences for their access to decent employment, health and other dimensions of well-being and the opportunities ahead. Strengthening the resilience and anti-fragility of public institutions and governments against future shocks is crucial to ensure the well-being of today’s young and future generations. Already prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, young people have been at the forefront of calls for a longer-term perspective in policy making and in building more inclusive and sustainable societies, for instance through a transition to greener economies.

For instance, the pan-European Recovery Action Plan developed by the European Students’ Union (2020[66]) advocates for a green transition while addressing the repercussions of the crisis. The plan was developed with student-led organisations worldwide and calls for a global response to the crisis in collaboration with young people. Representatives of the Y7 have requested G7 leaders to provide health equity, protect human rights and adopt a youth-sensitive approach in the aftermath of the Covid-19 crisis (2020[67]). As a lesson from the current crisis, the group calls for increased investments in mental health support, the digitalisation of educational programmes, and investments in the digital skills of young people.

Moreover, a number of youth-led organisations have analysed the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), pointing out that youth-related commitments in the SDGs are at severe risk of not being achieved due to the crisis.

Youth-led organisations have also called on their national governments to reinforce the representation of youth-related issues at the level of cabinet. For example, the British Youth Council is urging their government to create a Minister for Young People to bring the voice of youth into policymaking amidst COVID-19 (2020[68]).

Young people can act as a “connective tissue” in public institutions, decision-making processes and public consultations to bridge short-term concerns and long-term objectives and build more fair and inclusive policy outcomes and societal resilience (OECD, 2018[69]). Building resilience and anti-fragility of public institutions and empowering young people should therefore be pursued in tandem.

References

[52] African Union (2020), “African Youth Front on Coronavirus”, https://auyouthenvoy.org/ayfocovid19/.

[51] African Union (2020), “Virtual AU Youth Consultation Series”, https://auyouthenvoy.org/vaucs/#context.

[62] AIESEC Portugal (2020), “Youth Speak”, https://aiesec.org/youth-speak.

[30] BBC (2020), “Coronavirus bailouts: Which country has the most generous deal?”, BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52450958.

[39] Bouckaert, G. (2012), “Trust and public administration”, Administration, Vol. 60/1, pp. 91-115.

[28] Brennen, J. (2020), Types, sources, and claims of COVID-19 misinformation, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation.

[68] British Youth Council (2020), “Young people’s voices must not be ignored”, https://www.byc.org.uk/news/2020/young-peoples-voices-must-not-be-ignored.

[49] Butler, P. (2020), A million volunteer to help NHS and others during Covid-19 outbreak, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/13/a-million-volunteer-to-help-nhs-and-others-during-covid-19-lockdown.

[25] Campbell (2020), An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7152912/.

[78] Carcillo, S. et al. (2015), “NEET Youth in the Aftermath of the Crisis: Challenges and Policies”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 164, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5js6363503f6-en.

[53] Danish Youth Council (2020), “Corona info”, https://duf.dk/.

[60] Dutch National Youth Council (2020), , https://www.njr.nl/en/.

[10] DW (2020), “German government hosts coronavirus pandemic hackathon”, https://www.dw.com/en/german-government-hosts-coronavirus-pandemic-hackathon/a-53080512;.

[40] EC (2020), Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation – Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication-europe-moment-repair-prepare-next-generation.pdf.

[27] Edelman (2020), Edelman Trust Baromter 2020, https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2020-03/2020%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Coronavirus%20Special%20Report_0.pdf.

[11] E-Estonia (2020), “Innovation to combat the Covid-19 crisis”, https://e-estonia.com/innovation-to-combat-the-covid-19-crisis/.

[31] Elgin, C. et al. (2020), Economic Policy Responses to a Pandemic: Developing the COVID-19 Economic Stimulus Index, COVID Economics, http://web.boun.edu.tr/elgin/COVID_19.pdf.

[23] Etheridge B., Spanting L. (2020), The Gender Gap in Mental Well-Being During the Covid-19 Outbreak: Evidence from the UK, https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/research/publications/working-papers/iser/2020-08.pdf.

[55] European Association for Local Democracy (2020), , https://www.alda-europe.eu/newSite/lda_dett.php?id=20.

[37] European Parliament (2020), PUBLIC OPINION MONITORING at a glance in the time of COVID-19, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2020/covid19/en-public-opinion-in-the-time-of-COVID19-27042020.pdf.

[66] European Student’s Union (2020), , https://www.esu-online.org/.

[74] France, A. (2016), Understanding youth in the global economic crisis, Policy Press, http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89fwf.

[5] Gallup (2019), Gallup World Poll, https://www.gallup.com/analytics/232838/world-poll.aspx.

[43] Government of Canada (2020), Canada’s COVID-19 Economic Response Plan, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/economic-response-plan.html.

[58] Hayat Center for Civil Society Development (RASED) (2020), , http://www.hayatcenter.org.

[56] International Organization for Youth Development (2020), “Online Course”, https://www.facebook.com/IOFYD/.

[64] International Youth Foundation (2020), , https://www.iyfnet.org/blog/global-youth-resiliency-fund.

[81] Ipsos (2020), EARTH DAY 2020: How does the world view climate change and Covid-19?, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-04/earth-day-2020-ipsos.pdf.

[38] Kantar (2020), G7 countries perceptions of COVID-19: Wave 2, https://www.kantar.com/-/media/project/kantar/global/articles/files/2020/kantar-g7-citizen-impact-covid-19-charts-and-methodology-17-april-2020.pdf.

[24] McGinty EE et al. (2020), Psychological Distress and Loneliness Reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020, http://doi:10.1001/jama.2020.9740.

[79] Murphy, K. (2004), The role of trust in nurturing compliance: A study of accused tax avoiders, Springer, http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:LAHU.0000022322.94776.ca.

[59] Nahno (2020), , https://www.nahno.org/.

[54] National Alliance of Student Organisations (2020), “Nu ne izolați de educație!”, https://www.anosr.ro/nu-ne-izolati-de-educatie/.

[61] National Youth Council of Finland (2020), “Kannanotto: Seitsemän tavoitetta koronakehysriiheen, joilla pidetään nuoret mukana”, https://www.alli.fi/uutiset/kannanotto-seitseman-tavoitetta-koronakehysriiheen-joilla-pidetaan-nuoret-mukana.

[63] National Youth Council of Ukraine (2020), , http://nycukraine.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Zvernennya-do-Zastupnitsi-Minstra-molodi-ta-sportu.docx.

[57] Nous (2020), , http://www.nousngo.eu.

[2] OECD (2020), Combatting COVID-19’s effect on children, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/.

[22] OECD (2020), Coronavirus school closures: What do they mean for student equity and inclusion?, https://oecdedutoday.com/coronavirus-school-closures-student-equity-inclusion/.

[3] OECD (2020), COVID-19: Protecting people and societies, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/.

[19] OECD (2020), Education responses to COVID-19: Embracing digital learning and online collaboration, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/education-responses-to-covid-19-embracing-digital-learning-and-online-collaboration-/.

[14] OECD (2020), Global Report on Youth Empowerment and Intergenerational Justice, forthcoming.

[83] OECD (2020), How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

[21] OECD (2020), Learning remotely when schools close: How well are students and schools prepared? Insights from PISA, http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/.

[32] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Outlook,, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0d1d1e2e-en.

[44] OECD (2020), Regulatory Quality and COVID-19: Managing the Risks and Supporting the Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-policy/Regulatory-Quality-and-Coronavirus%20-(COVID-19)-web.pdf.

[20] OECD (2020), Schooling disrupted, schooling rethought: How the Covid-19 pandemic is changing education, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=133_133390-1rtuknc0hi&title=Schooling-disrupted-schooling-rethought-How-the-Covid-19-pandemic-is-changing-education.

[26] OECD (2020), Transparency, communication and trust: Responding to the wave of disinformation about the new Coronavirus, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/.

[15] OECD (2020), “Unemployment Rates, OECD - Updated: May 2020”, http://www.oecd.org/sdd/labour-stats/unemployment-rates-oecd-update-may-2020.htm.

[13] OECD (2020), Use of Open Government Data in response to the coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak,, https://www.oecd.org/governance/use-of-open-government-data-to-address-covid19-outbreak.htm.

[1] OECD (2020), Women at the core of the fight against COVID-19 crisis, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/.

[9] OECD (2019), Employment Outlook, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

[36] OECD (2019), Government at a Glance 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8ccf5c38-en.

[7] OECD (2019), OECD Short-Term Labour Market Statistics (database), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=35253.

[16] OECD (2019), Society at a Glance 2019: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2019-en.

[71] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[4] OECD (2018), OECD Labour Force Statistics 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/oecd_lfs-2018-en.

[69] OECD (2018), State of Fragility, OECD Publishing.

[48] OECD (2017), “Long-term fiscal sustainability analysis: Benchmarks for Independent Fiscal Institutions”, OECD Journal on Budgeting, Vol. 17/1.

[73] OECD (2017), OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278219-en.

[34] OECD (2017), The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, https://www.oecd.org/gov/oecd-recommendation-of-the-council-on-open-government-en.pdf.

[35] OECD (2017), Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en.

[8] OECD (2016), Society at a Glance, https://doi.org/10.1787/19991290.

[17] OECD (2015), OECD Employment Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/19991266 (accessed on 2 May 2020).

[47] OECD (2014), “Recommendation of the Council on Principles for Independent Fiscal Institutions”, https://www.oecd.org/gov/budgeting/OECD-Recommendation-on-Principles-for-Independent-Fiscal-Institutions.pdf.

[72] OECD (2014), “The crisis and its aftermath: A stress test for societies and for social policies”, in Society at a Glance 2014: OECD Social Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/soc_glance-2014-5-en.

[80] OECD (2013), Government at a Glance 2013, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-en.

[70] OECD (2010), OECD Employment Outlook 2010: Moving beyond the Jobs Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2010-en.

[77] OECD Development Centre (2019), Risk and Resilience - OECD, https://www.oecd.org/development/conflict-fragility-resilience/risk-resilience/ (accessed on 2 May 2020).

[42] Office of the Republic of Slovenia for Youth (2020), “Solidaren in inovativen odziv mladinskih organizacij v času epidemije”, Mladim, https://www.mreza-mama.si/solidaren-in-inovativen-odziv-mladinskih-organizacij-v-casu-epidemije/.

[50] Pieters, J. (2020), PM PRAISED FOR ASKING CHILDREN TO HELP SOLVE CORONAVIRUS PROBLEMS, https://nltimes.nl/2020/05/20/pm-praised-asking-children-help-solve-coronavirus-problems.

[12] Polandin (2020), “Gov’t launches virtual hackathon to fight COVID-19”, https://polandin.com/47367920/govt-launches-virtual-hackathon-to-fight-covid19.

[65] Project DAAM (2020), , http://projetdaam.org/.

[82] Queral-Basse, A. (2020), Responding to Covid19: Building social, economic and environmental resilience with the European Green Deal, http://eeac.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Responding-to-Covid19-Building-social-economic-and-environmental-resilience-with-the-European-Green-Deal.pdf.

[33] Rouzet, D. et al. (2019), “Fiscal challenges and inclusive growth in ageing societies”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 27, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/c553d8d2-en.

[75] The Economist (2020), What would eynes do? The pandemic will leave the rich world deep in debt, and force some hard choices., https://www.economist.com/briefing/2020/04/23/the-pandemic-will-leave-the-rich-world-deep-in-debt-and-force-some-hard-choices.

[46] The Treasury, N. (2019), “Our living standards framework”, https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/nz-economy/higher-living-standards/our-living-standards-framework.

[18] UN (2020), Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on children, https://un.org.au/files/2020/04/Policy-Brief-on-COVID-impact-on-Children-16-April-2020.pdf.

[29] UNESCO (2020), European cities call for inclusive measures during COVID-19 crisis, https://en.unesco.org/news/leavenoonebehind-european-cities-call-inclusive-measures-during-covid-19-crisis.

[41] Welsh government (2020), Leading Wales out of the coronavirus pandemic: A framework for recovery, https://gov.wales/leading-wales-out-coronavirus-pandemic.

[6] WHO (2020), Statement – Older people are at highest risk from COVID-19, but all must act to prevent community spread, http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/statements/statement-older-people-are-at-highest-risk-from-covid-19,-but-all-must-act-to-prevent-community-spread.

[76] WIcrramanayake, J. (2020), Meet 10 young people leading the COVID-19 response in their communities | Africa Renewal, https://www.un.org/africarenewal/web-features/coronavirus/meet-10-young-people-leading-covid-19-response-their-communities (accessed on 1 May 2020).

[45] Wright, T. (2020), COVID-19 has greater impact on women advocates say, https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/04/10/news/covid-19-has-greater-impact-women-advocates-say.

[67] Y7 Representatives (2020), “Young delegates Y7 2020 Summit website”, https://www.ypfp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Y7-COVID-Communique-FINAL-4.23.20.pdf.

Annex 1.A. Survey

This policy paper draws on the results from an online survey run by the OECD between 7-20 April 2020 with the participation of 90 youth-led organisations from 48 countries. The assessment surveyed respondents about the disruptions of COVID-19 to youth’s access to education, employment, mental health, and participation in public life among others. The assessment also enquired about their long-term worries as well as changes in their trust in government since the outbreak of the crisis and the reasons underlying such changes. Finally, responding youth organisations were asked about the type (and description) of the initiatives they put in place to mitigate the impact of the crisis.

The survey designed for this purpose is presented below. It was disseminated via networks of youth-led organisations, youth policymakers, and delegates to the Public Governance Committee of the OECD. While the survey does not represent jurisdictions or stakeholder groups, its goal was to include the perspective of a diverse group of youth-led organisations operating at the international, national and local level. The survey respondents do not constitute a representative sample statistically speaking and the analysis does not investigate respondents’ self-selection biases, hence making statistical inference not possible.

Respondents were asked to provide information that served to characterise their organisation and the country their responses referred to (if not internationally-based organisations). They were also asked to provide a link to the website of their organisation. All questions on substance as well as on respondent information were compulsory. Only those responses that included a valid URL/website presenting the work of a youth organisation were included in the final analysis.

- 1.

First name

- 2.

Last name

- 3.

Name of your organisation

- 4.

Website of your organisation

- 5.

Email

- 6.

In which country is your organisation based? Note: please specify if your organisation is operating internationally.

- 7.

How is your organisation participating, or planning to participate, in the efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19?

- a.

By running information campaigns to keep youth informed on the measures to protect oneself and others

- b.

By sharing practical advice on how to deal with mental and physical health, stigma and discrimination

- c.

By implementing specific programmes to support the most vulnerable youth (eg. homeless youth, youth with no access to digital means or health services, etc.)

- d.

By participating in programmes implemented by the government in your country to contain the spread of COVID-19.

- e.

By providing online activities/workshops/dialogue sessions to keep youth engaged with service areas (eg. education programmes, employment opportunities, trainings, etc)

- f.

Other, please specify (or insert n.a. if none of the above):

- a.

- 8.

Please share a brief description of up to three initiatives that your organisation is implementing in response to the COVID-19 crisis (eg. to promote intergenerational solidarity). Should your organisation not implement any programmes, please insert n.a. Please include links in your response and/or send supporting documents to GOVyouth@oecd.org

- 9.

In your organisation's opinion, in which 3 areas will young people find it most challenging to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis? (Please select 3 options maximum)

- a.

Familial and friendship relationships

- b.

Education

- c.

Employment

- d.

Disposable income

- e.

Housing

- f.

Physical health

- g.

Mental health

- h.

Access to reliable information

- i.

Limitation of individual freedoms

- j.

Other, please specify (or insert n.a. if none of the above):

- a.

- 10.

On a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is not worried at all and 5 is very worried, please indicate the extent to which your organisation is worried about the long-term impact of the COVID-19 crisis:

[1: Not worried at all ; 2: little worried; 3: Moderately worried; 4: Worried; 5: Very worried

- a.

Well-being of young people: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- b.

Well-being of the elderly: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- c.

Public debt: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- d.

Fake news: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- e.

Racial discrimination: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- f.

Intergenerational solidarity: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- g.

International cooperation among countries: [your rating from 1 to 5]

- h.

Other, please specify (and rate from 1 to 5):

- a.

- 11.

How has your trust in government evolved since the outbreak of the crisis?

- a.

Increased significantly

- b.

Slightly increased

- c.

Neither increased nor decreased

- d.

Slightly decreased

- e.

Decreased significantly

- a.

- 12.

Please explain your answer to the previous question:

- 13.

What do you think the OECD could do for young people and intergenerational solidarity in the context of the COVID-19 crisis?

Contacts

Miriam ALLAM, (✉ miriam.allam@oecd.org)

Moritz ADER, (✉ moritz.ader@oecd.org)

Gamze IGRIOGLU, (✉ gamze.igrioglu@oecd.org)

Notes

For the purpose of this report, “youth” is defined as a period towards adulthood which is characterised by various transitions in one person’s life (e.g. from education to higher education and employment; from the parental home to renting an own apartment, etc.). Where possible, for statistical consistency, the report employs the United Nations' classification of "youth" as individuals aged 15-24.

The OECD Job Quality Framework measures and assesses the quality of jobs based on three objectives: earnings quality, labour market security, quality of the working environment. Cazes, S., A. Hijzen and A. Saint-Martin (2015), Measuring and assessing job quality: The OECD Job Quality Framework, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 174, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/measuring-and-assessing-job-quality_5jrp02kjw1mr-en

Data is compared between 2007 and 2014.

Contributory factors in the “scarring effect” are human capital depreciation and the loss of professional networks during out-of-work periods. Employers might also see early periods of unemployment as a sign that a young person is less productive or motivated. Scarring might even negatively impact young people’s preference for work (Heckman and Borjas, 1980; Ellwood, 1982)

OECD Survey on COVID-19 and Youth (2020)

Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Africa, South Korea, the U.K. and the U.S

The original letter was published on 9 April and signed by government representatives of Austria, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Sweden. France, Germany and Greece joined in the following two days. Most recently, Ireland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Malta joined the appeal.

The “Green Recovery Alliance” was launched on 14 April at the initiative of Pascal Canfin, chair of the European Parliament’s committee on environment and public health. Members of the European Parliament from across the political spectrum, companies’ CEOs, business associations, the European trade union confederation, NGOs and think tanks have joined the alliance.

Independent fiscal institutions exist in a majority of OECD countries. “Independent fiscal institutions (commonly referred to as fiscal councils) are publicly funded, independent bodies under the statutory authority of the executive or the legislature which provide non-partisan oversight and analysis of, and in some cases advice on, fiscal policy and performance.”

Further good practices on intergenerational justice can be found at: www.youthworkgalway.ie, www.ccfug.net, www.projetdaam.org, https://www.nuis.co.il/, https://www.unige.ch/asso-etud/sdsa/.