The economy’s growth potential has declined in recent years and the income gap vis-à-vis advanced economy has widened, mainly due to comparatively weak labour productivity. Following years of falling investment that can explain almost 40% of the decline in labour productivity, Brazil has one of the lowest investment rates among OECD and emerging market economies. As a result, growth is likely to fall substantially below current levels unless new sources of growth are tapped into. Strengthening investment will be one key avenue to maintain solid growth and build on the social progress of the past. The ability of firms to pay better wages without jeopardising their competitiveness will depend crucially on stronger investment and productivity. One area of investment with particularly wide ramifications into other sectors is infrastructure and almost all areas of infrastructure are characterised by quality shortcomings and bottlenecks. Explanations for Brazil's low investment are related to a lack of profitable business opportunities in which the private sector could invest, owing to structural policy settings that act as a drag on the investment climate. Areas where reforms could significantly improve the business climate include red tape and licensing procedures, legal uncertainty, tax compliance costs, labour costs and improvements in workforce skills. Strengthening competition would allow a reallocation of resources to more productive firms and sectors, freeing labour and capital from low-productivity and low-remuneration activities. Financing has also been a constraint and a second important explanation for low investment. Long-term investment lending has so far been dominated by one single public-sector financial institution. Recent policy changes have paved the way for developing private long-term credit markets and tapping into more diverse sources of financing. For infrastructure financing, using a wider array of financial instruments would allow drawing institutional investors, including foreign ones, into financing infrastructure projects in Brazil.

OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil 2018

Chapter 1. Raising investment and improving infrastructure

Abstract

Stronger investment is a key requisite for solid growth

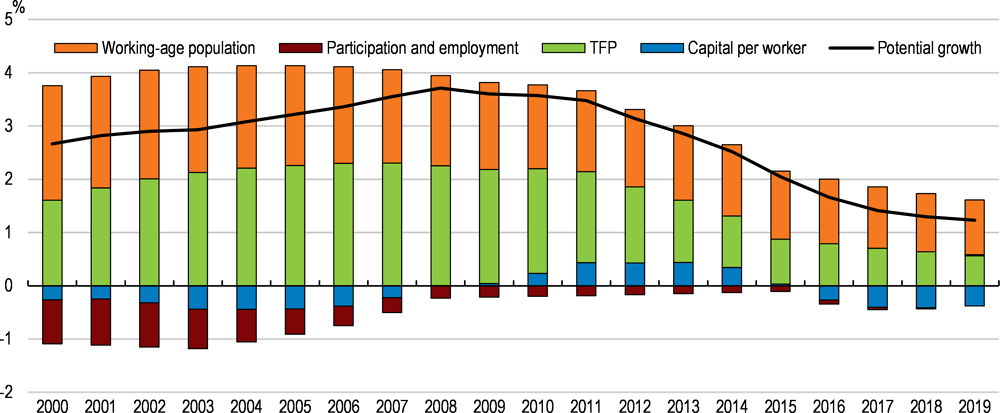

Over the last ten years, the growth potential of the Brazilian economy, which measures how fast GDP can grow over a longer horizon, has declined substantially, from around 3.8% per year in 2008 to now less than 2% (Figure 1.1). This growth differential makes a noticeable difference for material well-being. Growing at the current potential growth rate, income per capita would double over the next 40 years, reaching approximately the level where Greece or Estonia are today. By contrast, if the economy grew at 3.8% per annum, per capita incomes would be more than 4 times higher in 40 years, reaching approximately the current levels of Japan or New Zealand.

Figure 1.1. The economy’s growth potential has declined

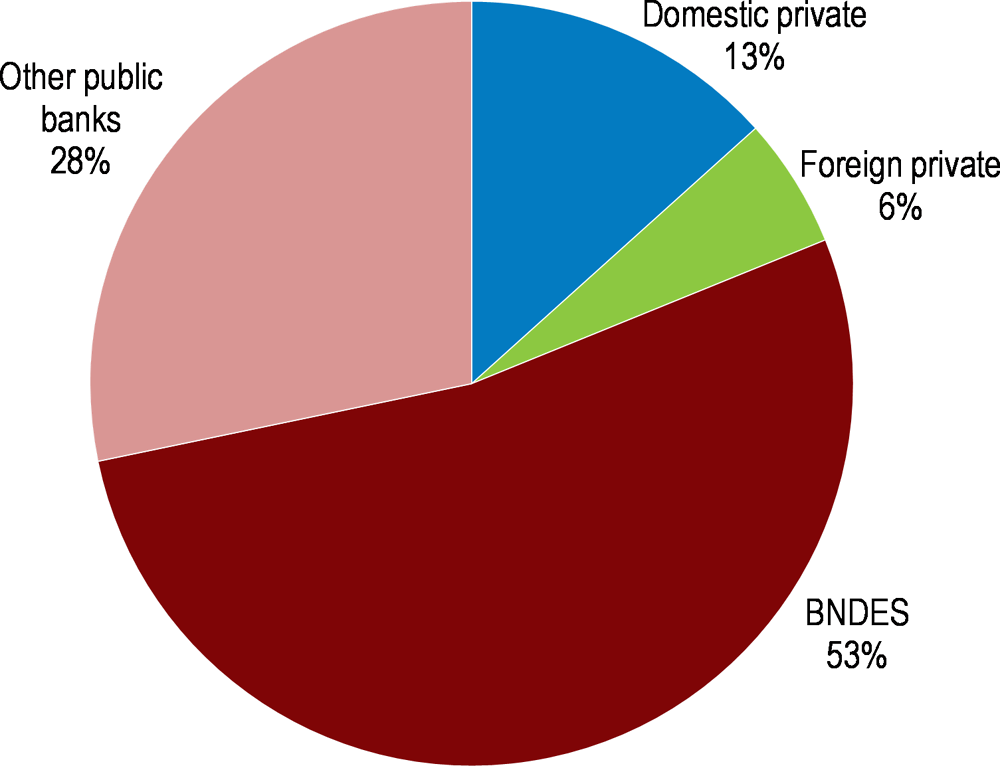

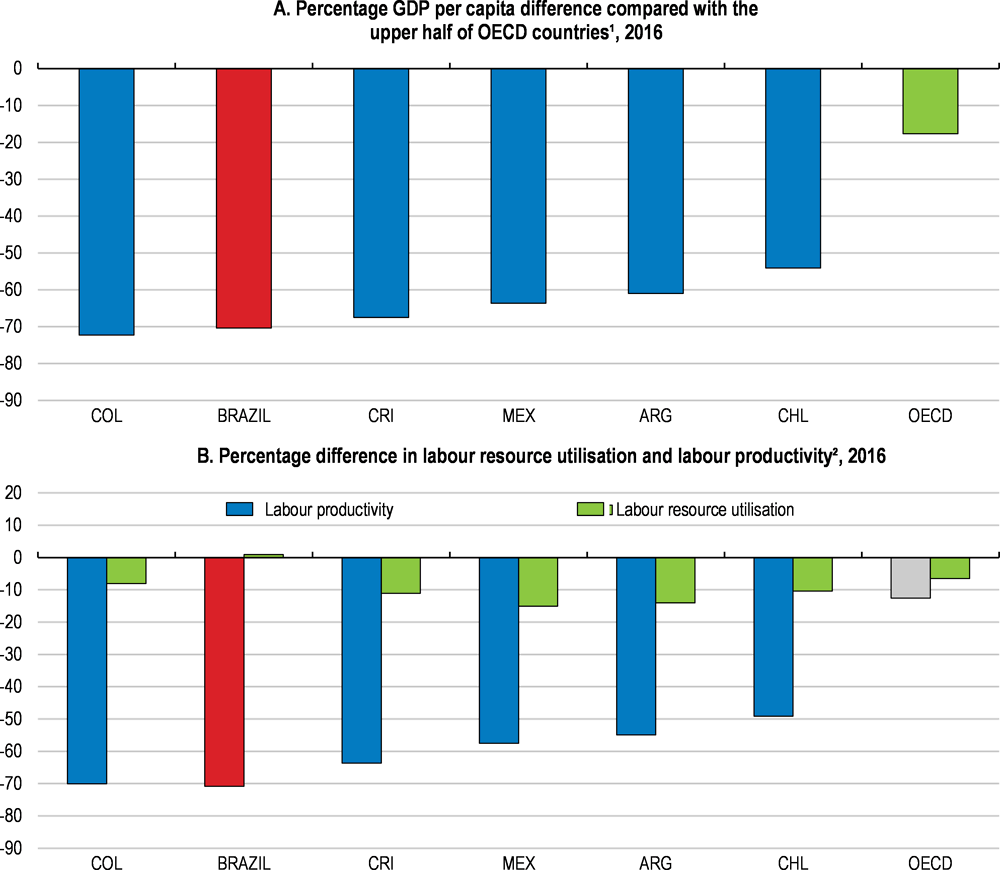

Consistent with the lower growth potential, the narrowing of Brazil’s significant GDP per capita gap with advanced OECD countries has stalled in recent years. This is the result of comparatively weak labour productivity (Figure 1.2). Productivity will have to become the principal engine of growth and is intimately linked to inclusiveness, as raising productivity is also about expanding the productive assets of an economy by investing in the skills of its people, allowing everyone to contribute to stronger productivity growth and ensuring that it benefits all part of society (OECD, 2016d; World Bank, 2018). At the same time, there is no guarantee that the benefits of higher levels of growth, or higher levels of productivity in certain sectors, when they materialise, will be broadly shared across the population as a whole. This calls for a comprehensive policy framework to account for the multiple interactions between inequalities and productivity and how these interactions play out across countries, regions, firms and between individuals.

Raising labour productivity can be done through two channels: stronger investment to equip each worker with a larger capital stock or higher multi-factor productivity, which measures how effectively factors of production are combined to produce goods and services. In fact, the falling investment has explained almost 40% of the decline in labour productivity since 1995 (Considera, 2017). Multi-factor productivity is itself partly related to investment, as technological progress embedded in new capital goods often allows improvements in the use of other resources or a better organisation of production processes. Moreover, many of the policy reforms that would be conducive to stronger investment are likely to also have beneficial effects for multi-factor productivity.

Figure 1.2. Income gaps with OECD countries remain large due to low productivity

1. Compared to the weighted average using population weights of the 17 OECD countries with highest GDP per capita in 2015 based on 2015 purchasing power parities (PPPs). The sum of the percentage difference in labour resource utilisation and labour productivity do not add up exactly to the GDP per capita difference since the decomposition is multiplicative.

2. Labour productivity is measured as GDP per employee. Labour resource utilisation is measured as employment as a share of population.

Source: OECD National Accounts and Productivity Databases; World Bank, World Development Indicators (WDI) (Database); ILO (International Labour Organisation), Key Indicators of the Labour Market (KILM) Database.

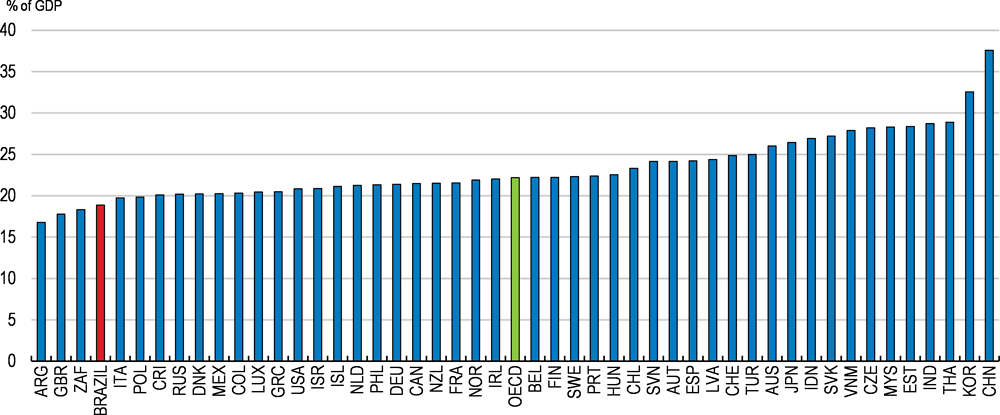

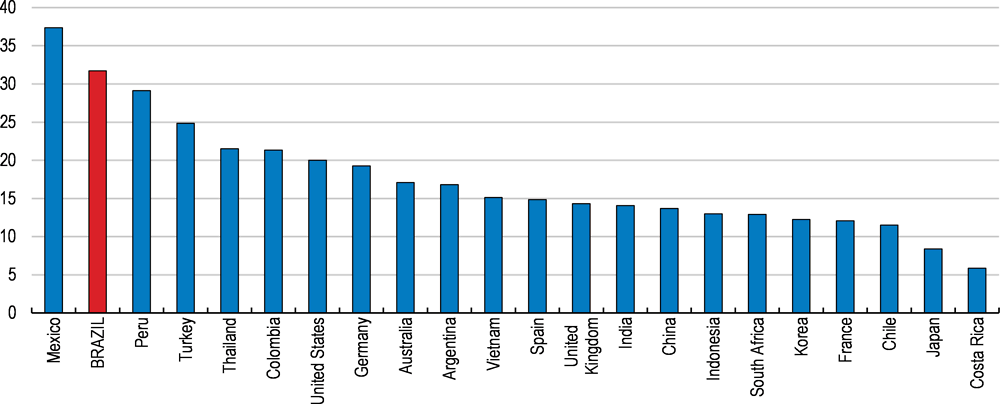

Brazil invested only 13.7% of GDP in 2016, which is one of the lowest investment rates among OECD and emerging market economies (Figure 1.3). Even though investment has never contributed as much to economic growth as in other economies, notably in Asia, a decline in investment is one of the reasons why the economy’s growth potential has declined so sharply. Over the last years, investment has hardly exceeded the depreciation of the existing capital stock, meaning that growth of the productive capital stock has stalled if not declined.

Figure 1.3. The investment rate is low in international comparison

Gross fixed capital formation as % of GDP, 1990-2016

This comes in addition to declining labour inputs, which are largely the result of demographic changes. Going forward, the boost to economic growth from demographic changes is going to diminish continuously as Brazil embarks on a process of rapid population ageing. As a result, the economy’s growth potential is likely to fall substantially below current levels unless new sources of growth are tapped into, such as stronger investment.

Strengthening investment will therefore be one key avenue to maintain solid growth and build on the social progress of the past. In fact, the recent emergence of a new Brazilian middle class owes much to the combination of new employment opportunities arising from economic growth and improving access to education, which enabled more people to move into better paid jobs (Chapter 2 of OECD Economic Survey of Brazil 2013). Boosting investment also matters for wage and productivity developments. Low investment limits the growth of labour productivity, which represents the wage increases that Brazilian workers can pocket without deteriorating the competitiveness of domestic producers.

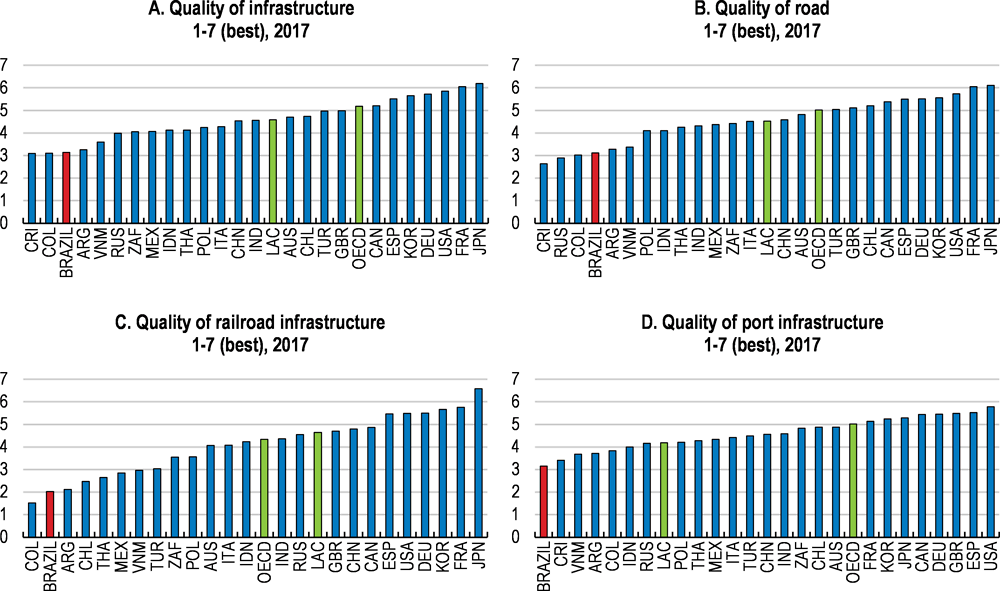

One area of investment with particularly wide ramifications into other sectors is infrastructure. For households, and especially those with low incomes, the availability of transport, electricity, safe water and sanitation and other basic facilities have a direct bearing on their quality of life. Brazilian businesses are suffering competitive disadvantages from high transport and logistics costs. On infrastructure quality, Brazil ranks 116 out of 138 countries in the latest World Economic Forum survey, following years of losing ground to other countries. Quality shortcomings are common to several aspects of infrastructure (Figure 1.4). For example, transport costs for soy exports to China are three times higher from Brazil than from the United States, with the bulk of that explained by the cost of road transport, which is used for transporting 60% of agricultural commodities due to an underdeveloped rail network.

Figure 1.4. Infrastructure quality is low

Why has investment been so weak?

Investment implies foregoing consumption opportunities today in the hope of greater benefits in the future. Hence when an economy does not invest much, it can be either because the future benefits of doing so are low or uncertain or because there are not enough resources to be put aside today. Explanations in the former area call for improving investment opportunities, including by improving the business climate, while the latter type of explanations have to do with savings and the capacity of the financial sector to channel them to those with lucrative investment opportunities.

Possible explanations for Brazil’s low investment rate can be found along both of these dimensions. Much can be done to create more profitable business opportunities in which the private sector could invest. This includes a variety of measures that could reduce the by now well-known “Brazil cost”, such as reducing the costs of complying with unnecessarily cumbersome regulations and complex tax rules, a more effective judiciary, or further progress in alleviating skill scarcities. All of these factors have contributed to low productivity in tradable sectors (Figure 1.5). In the infrastructure sector, a better performance of public institutions could make it significantly easier for the private sector to engage in the execution and the financing of infrastructure projects. Better incentives and more opportunities for strong-performing enterprises to grow, including at the expense of less efficient incumbents, would also create new investment opportunities with higher returns. These issues will be discussed in the section on raising the returns on investment.

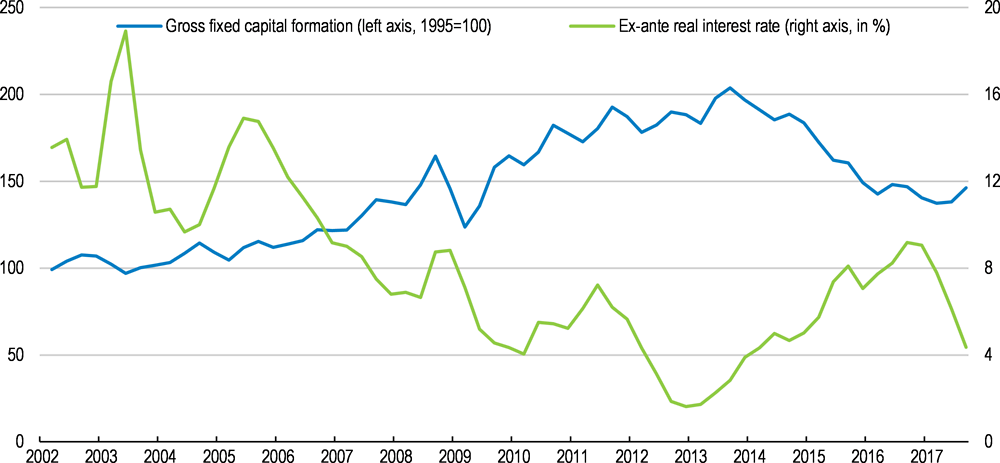

Figure 1.5. Productivity is low in international comparison

Labour productivity in thousands of 2010 USD per employee, 2015

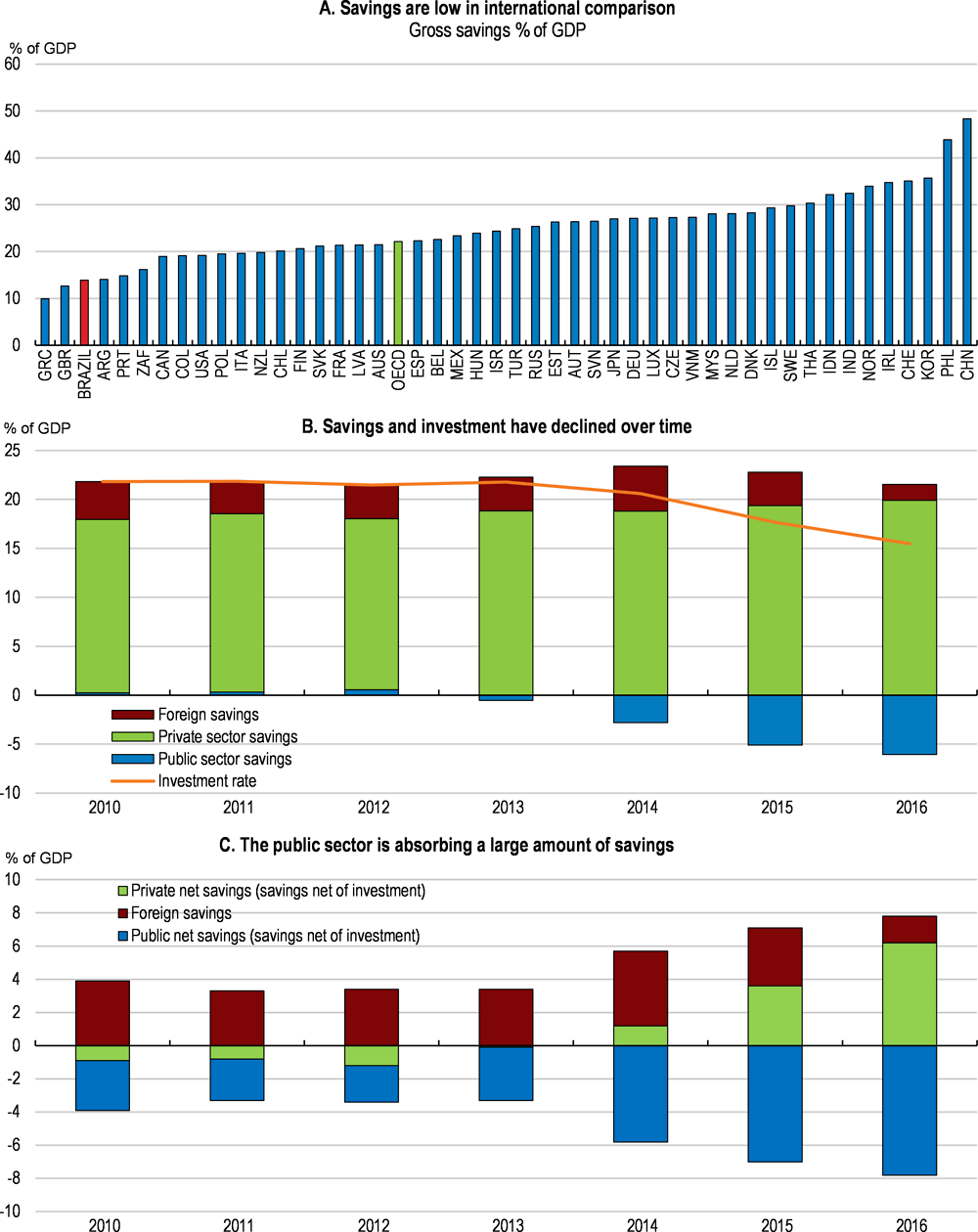

On the financing side, Brazil has traditionally been characterised by low domestic savings, lower than in other emerging economies, particularly in Asia (Figure 1.6). The scarcity of saving is also reflected in the high real interest rates with which Brazil remunerates saving (Bacha, 2010a). At the same time, already low saving has declined markedly since 2013, reflecting primarily a steep decline in public sector savings. This means that an increasing amount of private saving has been absorbed by the public sector, estimated at 6.2% of GDP in 2016. Since the public sector has invested less and less over time, potential private investment has been crowded out by public consumption, not public investment. Empirical work suggests that whenever domestic savings, which include public savings, increase or decline by one percentage point of GDP, investment increases or declines by half a percentage point of GDP (Considera, 2017). Increasing public savings through a reduction of the fiscal deficit would therefore alleviate financing constraints for investment. At the same time, even in the years when public savings were higher, investment was still low, suggesting that additional policy action is required to strengthen investment.

Figure 1.6. Saving is low and has declined

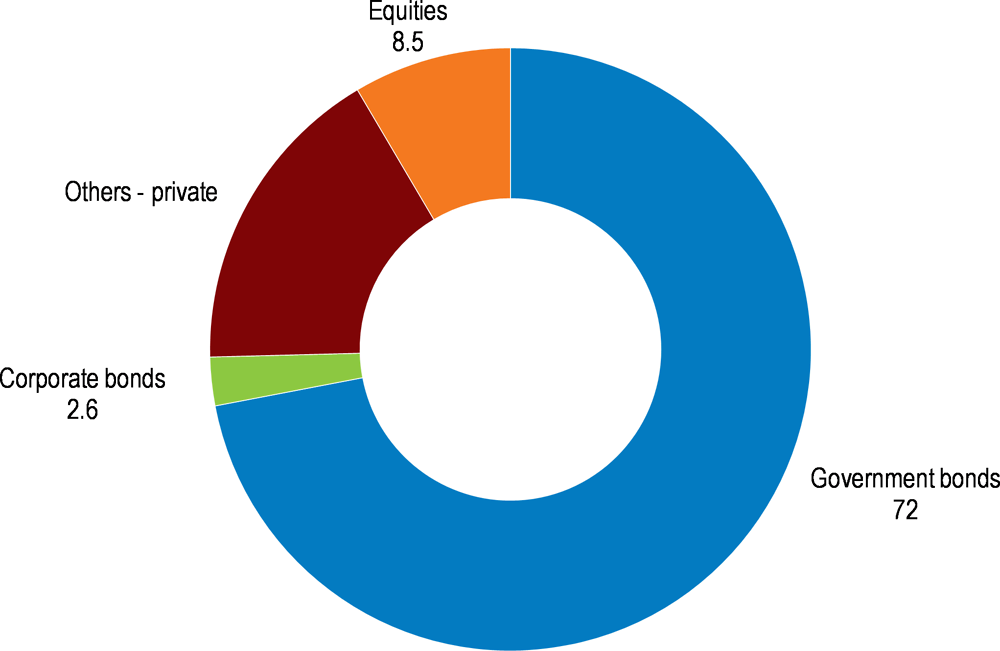

Brazil also has a few peculiar features in the relationship between the public and private sectors with respect to savings. While most countries use private savings to finance private investments, much of private savings in Brazil flow into public debt. The portfolio of Brazil’s asset management industry consists to more than 70% of public-sector bonds and has risen by almost 10 percentage points of GDP over the last years (Figure 1.7). At the same time the public sector is the single largest source of financing for private investment (Canuto and Cavallari, 2017). Possible reforms affecting the financial sector and its role in intermediating between savers and investors will be discussed in the next section on improving access to financing.

Figure 1.7.Private sector assets under management

In percent of total, January 2017

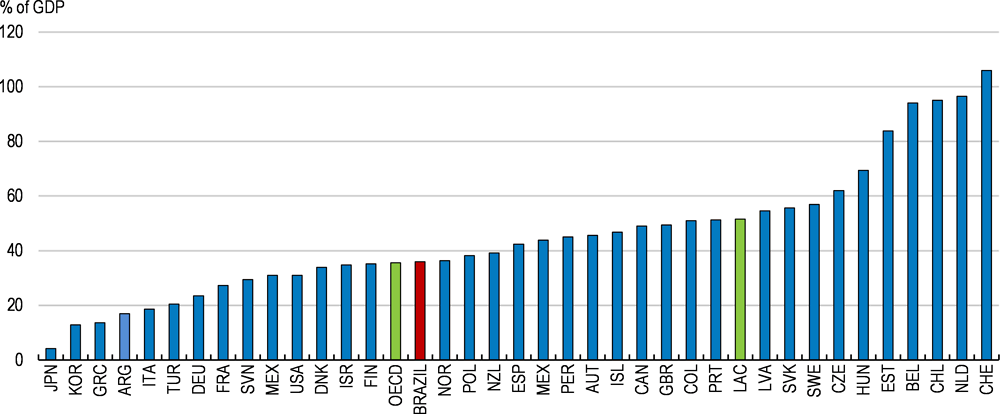

Foreign savings can be a complement to domestic savings as capital inflows can finance domestic investment, in particular when it comes in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI). In theory, this should decouple investment in a given country from its own capacity to save since in a frictionless world, capital would simply flow to where its returns are the highest. In reality, however, foreign savings are an imperfect substitute to domestic savings and domestic investment tends to be highly correlated with domestic savings. This empirical regularity has become known as the Feldstein Horioka (1980) puzzle. In Brazil, the correlation between domestic savings and domestic investment has been 67% since the turn of the millennium. Although FDI inflows have been resilient even in the face of the major recession that the economy has gone through, the stock of foreign direct investment is below those observed in other Latin American countries, such as Chile, Peru or Mexico (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Brazil attracts less direct investment than other countries in the region

Stock of FDI, 2015

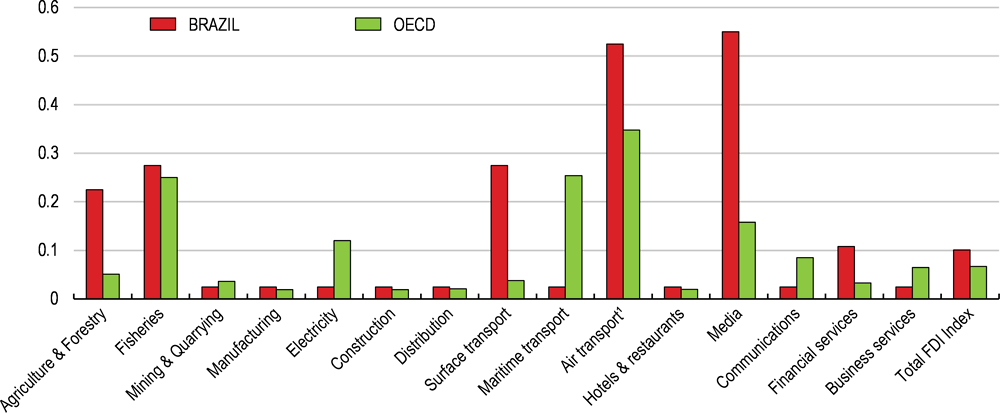

The economy is fairly open to international investment flows. Particularly restrictions on foreign direct investment are at comparable levels with OECD economies and concentrated in only a few sectors (Figure 1.9). A recent presidential decree has temporarily removed ceilings on foreign capital in airlines, although this has yet to be approved by Congress. Without this, Brazil’s FDI restrictions in air transportation are still high in international comparison.

Figure 1.9. FDI restrictions are low compared to OECD countries

Only sectors with significant restrictions in Brazil shown

1. Could move to 0.025 if the recent temporary removal of foreign capital restrictions in airlines became permanent.

Source: OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index database.

However, more can be done to attract more FDI. Adopting a comprehensive and coherent approach to investment climate reforms, which are essentially the same as those that would raise domestic investment, would allow Brazil to use foreign savings more than it has in the past to finance its investment needs. Among the different aspects of the business climate, foreign investors may be particularly sensitive to judicial uncertainty and the stability of rules. Bolstering foreign direct investment in the agriculture sector could be a valuable avenue to bolster Brazil’s participation in global value chains, particularly in the agro-food sector. In the area of infrastructure, structural changes on financial markets and a wider variety of financial products tailored to the needs of specific foreign investor profiles would allow tapping into international financial markets in a way previously unseen.

Raising returns on investment

Better policy settings could result in substantially lower costs of operations for most Brazilian companies. Brazil’s high cost of production is the result of complicated regulatory procedures, ineffective contract enforcement, judicial uncertainty, high tax compliance costs, labour costs and infrastructure bottlenecks. Costs beyond the influence of firms make it harder for them to compete and reduce returns to investment.

Reducing red tape and regulatory barriers would reduce costs and improve incentive structures

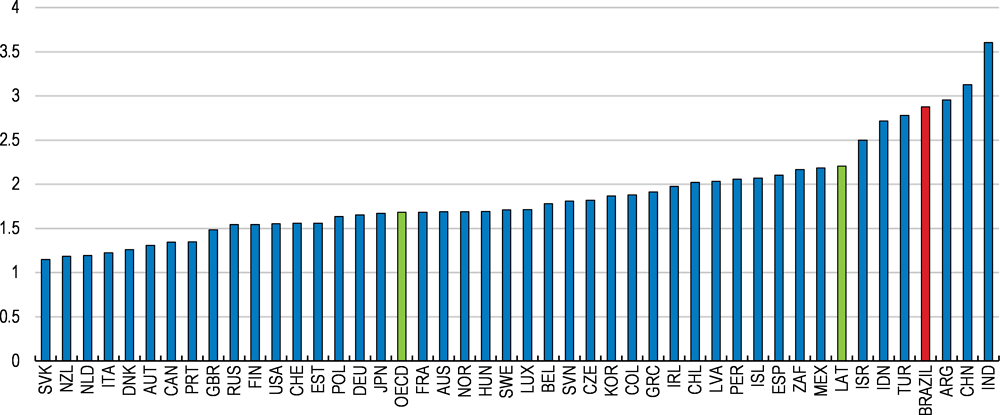

Brazil’s regulatory procedures for market entry and licensing have long been significantly more cumbersome and restrictive than in OECD countries, and lack transparency and simplicity, according to the OECD Product Market Regulation indicators (Figure 1.10).

Figure 1.10. Regulatory barriers to entrepreneurship are high

Indicator scaled from 0 (least restrictive) to 6 (most restrictive), 2013

Note: LAT includes Argentina, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. Data for Argentina are for 2016.

Source: OECD Product Market Regulation Indicators, 2013, available at www.oecd.org/eco/pmr .

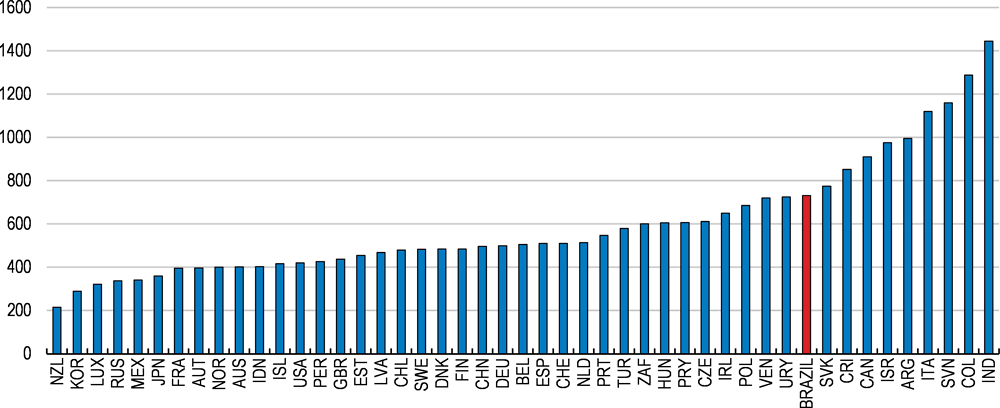

The widely used World Bank Doing Business indicators confirm this picture, positioning Brazil at rank 123 out of 190 economies surveyed for the ease of doing business. Brazil is particularly far behind best practice in areas such as the licensing process to start a business, dealing with construction permits or registering property. Starting a business requires 12 procedures in Brazil and takes 83 days, while Chile, Colombia and Mexico require fewer procedures that can be accomplished in less than 11 days (Figure 1.11).

Figure 1.11. Ease of starting a business

Days required to start a business, 2017

Recent government initiatives have included pilot projects, including in the capital city of Brasilia and in São Paulo, to allow opening and closing a company within a few days. In São Paulo, for example, the time to open a business fell from 101 days to 7 days. A nationwide rollout of such fundamental reforms has not happened yet, but would be a major improvement. Besides the procedures to open a business, streamlining licensing procedures is also crucial. In this regard, Portugal has recently made positive experiences with applying a silence-is-consent rule in areas without major safety or environmental concerns. Brazil could apply easier administrative procedures and streamline licensing procedures more widely, to make sure its regulations do not unnecessarily hinder entry and competition.

In addition, environmental licensing is often adding to the costs and regulatory uncertainty of investment projects. Despite recent improvements, overlapping responsibilities between understaffed environmental agencies at the federal, state and municipal levels and cumbersome licensing procedures create delays and regulatory uncertainty, including about the length of the delay. The licensing process could be streamlined significantly without detriment to legitimate environmental concerns, for example by rolling out single-window facilities, making use of on-line tools or improving the sharing of information across government agencies.

Several regulatory agencies have made progress in launching regulatory impact assessments before making changes to existing regulation, although this is not yet a consistent practice across the whole administration. Applying such assessments more widely and in a harmonised manner could help to avoid further regulations with detrimental effects on entry. In addition, systematic use of ex post evaluation to assess whether regulations achieve their objectives is mostly unexplored.

One factor that delays licensing is that public sector managers can be held personally liable for their decisions. In fact, officials have much to lose if ex-post a judge takes a different view on the impact of a specific license than the official had at the time of granting it. As a result, public officials tend to be overcautious and try to back up any decision with long legal analyses. Limiting the possibilities to take public officials to court over their decisions to cases of abuse or bad faith would have significant potential to speed up licensing procedures.

Empirical results from firm-level analysis suggest that easing these administrative burdens is likely to improve the productivity of Brazilian firms as the number of procedures required for starting a business and the associated delays are negatively associated with firm level productivity (Box 1.1, Arnold and Flach, 2018a). These findings are confirmed by cross-country panel regressions that control for other time-invariant differences across countries and for time effects (Ferreira Mation, 2014). Their work suggests that if Brazil’s labour productivity could be 11% higher if its business climate were to improve to the level of Chile’s, for example. The prospects for the entry of new and innovative firms could also improve with the development of deeper capital markets (Kerr and Nanda, 2009; Hubbard, 1998; Beck, 2007; Aghion et al., 2007).

Brazil’s tradable sector would also benefit from more competition in upstream non-manufacturing sectors, as access to cost-effective and innovative services inputs can play an important role for manufacturing productivity (Arnold et al., 2011; 2015; World Bank, 2018). As measured by the OECD Product Market Regulation (PMR) indicators, regulations that curb competition in non-manufacturing sectors are more restrictive in Brazil than in the average OECD country, but less so than in the average of the BRIICS countries. While Brazil scores 2.54 on a scale of 0 to 6 in 2013, similar to the average values of China, India, Russia and South Africa, but significantly higher than the OECD average of 1.51.

Box 1.1. Identifying constraints to productivity growth using firm-level data

In order to explore the link between structural policy variables and productivity, a large data set of accounting data from over 16 000 firm observations across Brazilian industrial and services sectors has been analysed. Using data from firms’ annual balance sheets and profit and loss accounts from the ORBIS database, total factor productivity (TFP) is calculated as a multilateral index with industry-specific factor intensities, following Griffith et al. (2004). The main advantage of the index approach of measuring TFP is that it makes the comparison between any two firm-year observations possible, since each firm’s inputs and outputs are calculated as deviations from a reference firm. Robustness checks with other TFP measures have also been used to confirm the findings. The data have been cleaned for obvious outliers and reporting mistakes, which has resulted in dropping less than 1% of the original sample. A few sectors have been excluded from the analysis due to their monopolistic nature such as in the case of utility sectors, or due to their the strong degree of public control, such as in public administration, defence, education and health services, or because they are subject to strong cyclical swings such as financial services or mining.

In a second step, firm-level TFP is then used as a dependent variable and related to policy measures or variables that are directly influenced by policies. The empirical strategy follows closely the difference-in-differences approach proposed by Rajan and Zingales (1998). The rigour of this approach stems from the fact that it draws on comparisons only across comparable units, such as firms within the same state of Brazil and the same year. In a typical estimation set-up, and there are minor differences across the estimations due to data availability, the policy variable varies across time or across states, and is interacted with an industry-specific variable that is assumed to measure the relevance of this policy aspect for the sector to which the firm belongs. For example, in the case of energy costs that vary across states, the interaction factor is the energy intensity of industries. This set-up assumes that firms in sectors that are more energy-intensive are more affected by regional differences in energy costs than other sectors. The estimation coefficient is hence identified only from comparisons across firms in different industries within the same state. State industry combinations are the level at which the interaction measure varies, while fixed effects control for all idiosyncratic productivity influences specific to combinations of states and years and specific to industries. The resulting estimation equation in this case is the following:

TFPit = α + β energy_costreg*energy_intensitys + sizeit + ageit +Dreg,t + Ds + εit

where subscripts i denote the firm, t the year, reg the region or state, s the sector. Size and age denote a firm’s size in number of employees and age since its date of incorporation. D are binary variables and ε is a white-noise error term. Whenever possible, and following the strategy of Rajan and Zingales (1998), the interaction factors at the industry level have been taken from international benchmarks, for example the United States, rather than from Brazilian data, to ensure a maximum degree of exogeneity. This empirical strategy means that the estimated effect can be interpreted as causal under acceptance of the identifying assumption, i.e. the relevance of the interaction factor chosen. Estimation results have been obtained for the effects of energy prices, transport and road infrastructure, the tax burden, several aspects of administrative burdens, labour regulations and skill availability. Detailed estimation results including regression results are presented in the Annex to this Chapter.

Reducing legal uncertainty and strengthening contract enforcement

The investment climate could also be improved by reducing uncertainties related to the judicial system and to regulation. Both an ineffective court system and frequent regulatory changes in recent years have made legal uncertainty a key concern among investors. Clear, transparent and stable legal and regulatory frameworks help reducing legal risks, which can be a strong deterrent for investors as the possibilities for insuring against such risks are usually very limited. In regulated sectors such as utilities, communications and transport, the principle responsibility for this lies with sectoral regulatory agencies, which have been characterised by heterogeneous degrees of institutional capacities and independence in the past. Building up confidence in regulatory frameworks will take time, but avoiding ad-hoc changes and political interference, including through political appointments, is key for confidence to improve.

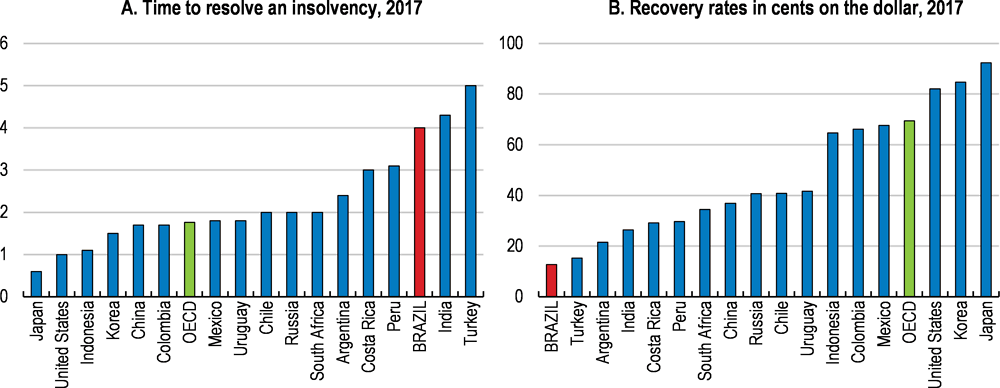

Enforcing contracts through the judicial system is lengthy and the outcome is often uncertain due to the significant discretionary power of judges. The cumbersome procedures of dealing with courts can substantially add to firms’ costs and reduce their productivity. Enforcing a standard debt contract takes 731 days in Brazil, compared to 230 in Korea, 338 in Mexico, 426 in Peru or 480 in Chile (Figure 1.12). The time and value losses resulting from inefficient processes of resolution of contractual conflicts and insolvency situations have repeatedly been mentioned as a key constraint for the investment climate (Canuto, 2016). Empirical evidence from firm-level data suggests that higher enforcement costs hamper firm productivity, and this effect becomes particularly pronounced when focusing young firms that have been in business for less than 5 years (Box 1.1, Arnold and Flach, 2018a).

Measures to enhance the efficiency of the judicial system adopted across OECD countries include reorganising courts, implementing electronical judicial files and promoting out-of-court solutions to conflicts. The latter is particularly important, as mediation arrangements can provide faster and more efficient resolution of commercial disputes. Increasing competition in the legal profession can also induce lower litigation and hence have a positive effect on the efficiency of the system.

Figure 1.12. The court system is slow to resolve commercial disputes

Time required to enforce a contract (in days), 2017

Effective insolvency procedures can play a crucial role to boost investment and productivity (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2016). A well working insolvency framework is crucial to restructure companies that are still viable and to allow a speedy recovery of non-viable companies’ assets before they lose value or can be abducted from the insolvent company. It can also boost entrepreneurship by providing second chance opportunities to entrepreneurs.

Brazil reformed its insolvency law in 2005. The reform aimed at providing creditors with a more rapid liquidation of distressed firms and allocated higher priority for secured creditors vis-à-vis workers and tax authorities. It resulted in credit expansion and business investment growth, especially in high productivity firms (Arnold and Flach, 2018b). However, Brazil’s insolvency procedures continue to be less efficient and more costly than those found in OECD and in peer Latin America countries (Figure 1.13). A typical bankruptcy resolution takes 4 years in Brazil, compared to 2.9 years in LAC countries and 1.7 years in OECD countries. Since assets of distressed companies tend to lose value quickly, it is not surprising that Brazil’s recovery rate on debt with insolvent companies is only 15.8 cents on the dollar, while it is 31 cents in Latin America and Caribbean and 73 cents in OECD high-income countries (World Bank, 2017b).

Figure 1.13. Insolvencies are slow and recovery rates low

Faster and more efficient insolvency procedures would lower the credit risk of corporate borrowers and contribute to boost private investment. Acknowledging this, authorities are reviewing insolvency procedures to make them clearer and to facilitate quicker processes. Among new features being considered is the possibility for tax authorities to take a haircut, facilitating that firms can access finance during the recovery processes and strengthening out-of-court procedures. The latter is particularly important, as bottlenecks in the judicial system prevented that the 2005 reform boosted investment and productivity more strongly. Firms operating in districts with more congested courts experienced lower access to loans and lower increase in investment and productivity than firms operating in districts with less congested courts (Ponticelli, 2015). Overall, planned changes seem to go in the right direction to improve insolvency procedures.

Reducing the cost of complying with taxes

Brazil’s tax system is a major cost driver for companies and substantially reduces investment returns, both because of the level of taxes and compliance costs. Corporate taxes with a peak rate of 35% are high in international comparison. A combination of unifying several parallel corporate tax systems, broadening the base and reducing the rate may help to simplify corporate taxes and reduce distortions. In addition, several consumption taxes drive up overall tax levels on formal sector companies. In part, this is owing to the weak design of consumption taxes which, when properly designed, do not constitute a burden on businesses. However, in the current fiscal context, the scope for reducing public revenues is extremely limited. Still, even within the realm of revenue-neutral tax reforms, Brazil can improve investment returns significantly by making the tax system more efficient and easier to comply with.

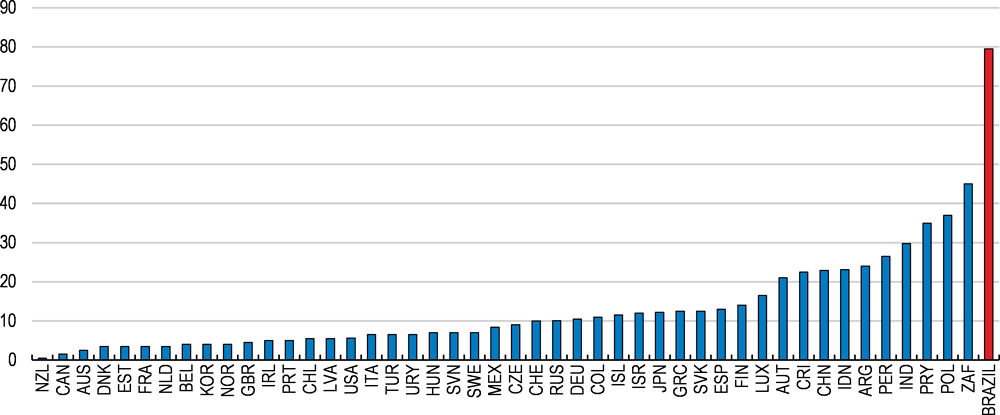

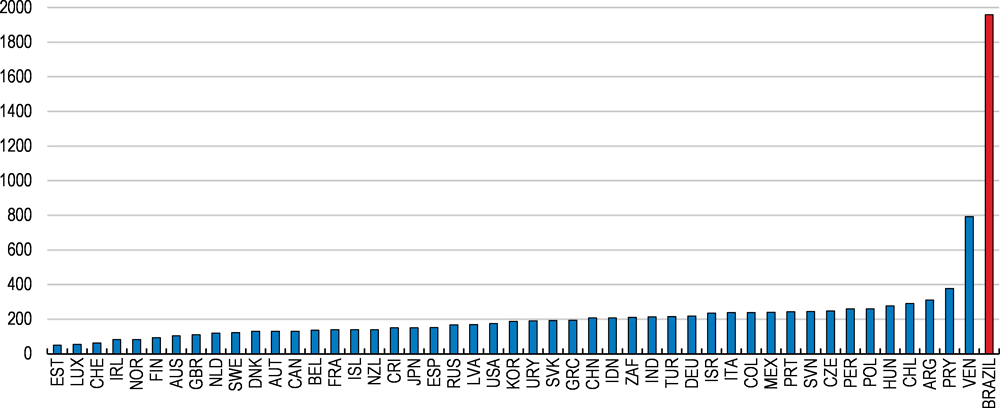

When measuring the time requirement to comply with taxes for a benchmark manufacturing company in 190 jurisdiction across the world, the World Bank finds that Brazil comes out as one of the last, with 2 600 hours required, as opposed to 356 in the average Latin American country or 184 in the average OECD country (Figure 1.14). Tax departments of companies are consequently huge in international comparison, adding substantially to fixed costs. Some estimates suggest that for the whole economy, tax compliance costs alone amount to 0.43% of GDP (Appy, 2013), while other estimates have calculated that tax compliance costs for industrial companies as 2.6% of consumer prices (Coelho, 2015).

Figure 1.14. Hours required to prepare taxes

2017

Scope for simplification exists primarily in the area of indirect taxation. Brazil has 6 different kinds of consumption taxes, which generate more than half of public revenues. The industrial sector stands to gain particularly from a comprehensive consumption tax reform, as it is heavily affected by the complexity and weak design of consumption taxes, including the lack of refunds for taxes paid on fixed assets. For example, about a third of consumption tax revenues comes from manufacturing firms, which account for only 13% of value added, according to industry estimates (Coelho, 2015). In contrast, the services sector is facing a lighter tax burden.

The largest of Brazil’s 6 consumption taxes, called ICMS raises revenues of around 8% of GDP. It is levied by Brazil’s states and each state applies its own tax code, tax base and tax rates. Brazil applies a mixture of the origin and destination principles to interstate commerce and companies wishing to offer goods and services nationwide are required to comply with each state’s individual tax rules. Credits for interstate transactions are regularly delayed or refused (CNI, 2014a).

Another reason why compliance costs are high relates to the imprecise definition of tax credits for inputs, which gives rise to excessive litigation. Tax credits for consumption taxes paid on inputs follow the so called “physical credit” principle, by which tax credits are granted only for inputs embodied in the final good sold. This rules out tax credits for overhead expenses and in particular fixed assets. As a result, it raises the cost of capital and breaks the usual “neutrality” of a well-designed VAT. The “physical credit” principle requires companies to prove that every input for which they claim a credit goes directly into the final product. A practical example is that industrial companies often hire tax accountants to identify how their electricity consumption is divided between the part that powers the machines and the part that lights the companies’ offices, with the former being deductible and the latter not. Lawsuits over disputes are common and use up resources that could be employed more productively. Recent initiatives to allow tax credits for all intermediate goods should be implemented swiftly.

The ICMS tax base is narrowed by the exclusion of many services, which are instead subject to a municipal service tax called ISS, which does not allow any credit for inputs, making it effectively a sales tax T. The uneven tax treatment of the industrial and the services sector should be eliminated. This could even lead to some increase in revenues, given that the services sector is currently taxed less than the industrial sector.

Another large consumption tax is a set of federal “contributions”, including those known as PIS/Pasep, and Cofins. Together these contributions account for 7.5% of GDP in revenues. Tax credits for intermediate inputs are also subject to the “physical credit” principle, as in the case of the ICMS. In addition, PIS/Cofins is often applied on the value of a good including ICMS tax already paid on it, thus making the two taxes cumulative.

A special sales tax called IPI is levied on certain industrial products. The IPI has been used for temporarily protecting Brazilian producers in specific sectors, for example the automobile sector, against international competition since 2011, by charging differential rates according to the share of local content. Finally, another special federal tax called CIDE has been levied on select goods and services, most notably on imports of services and financial transactions including remittances abroad. CIDE contributes to the very high taxation of imported services, for which effective tax rates range between 40% and 50% (Ernest and Young, 2013). This is not only a very high tax burden but also a barrier to competition and it precludes Brazilian companies from the competitive advantages associated to international trade in tradeable services. The tax distortion against imported services is further aggravated by the relatively low tax burden on domestically produced services relative to goods. CIDE has also been levied on petrol, on which the effective tax burden is lower than in other countries and could be raised further to promote responsible use of fossil fuels and incentivise the use of ethanol for powering cars (see Assessment and Recommendations).

A sensible tax reform would be to consolidate the different consumption taxes into one value-added tax with simple rules. The federal government could lead the way by consolidating its own consumption taxes into a single value added tax with a broad base, full refund for input VAT paid and zero-rating for exports (OECD, 2017c). Once such a tax were established, it might be easier to integrate the state-level ICMS into this system, possibly as state-specific surcharges on the same tax base that preserve current revenues. While tax reforms involving different levels of government are typically politically difficult, other countries like India has recently managed to unify state-level consumption taxes (OECD, 2017b).

In principle, it is possible to accommodate the desire for different states to tax at different rates, once taxation strictly follows the destination principle and tax credits are refunded swiftly for interstate transactions. Such a system is applied in the European Union, for example, where different member states apply different tax rates but consumers are normally subject to VAT in the destination country.

For many years now, the central government has discussed plans to harmonise the state-level ICMS. The challenge, however, is to find a political consensus among the states, some of which are threatened by revenue shortfalls from a rationalisation of the system as they effectively tax consumption taking place in other states. Moving towards a destination principle would make this impossible, so that a temporary compensation of some states via the federal government may help to allow these states to adjust gradually and would make it easier to reach a consensus, as has been done in India (OECD, 2017b). In light of the political difficulties involved in reforming the ICMS system, there has not been any progress since the unification of ICMS rates for imports in 2012, which had put an end to unproductive tax competition among states to attract import shipments.

Labour costs and complex labour regulations have curbed investment incentives

Labour regulations have been reported as the fifth most important obstacle to growth and competitiveness by Brazilian firms, and as the second highest by large firms (World Bank, 2014). Brazil’s labour justice alone costs 0.3% of GDP, more than twice as much as the whole justice system in Argentina (Da Ros, 2015; CNJ, 2016). The 1943 labour code contains many very detailed rules whose benefits to either employees or employers are no longer evident. Prior to a labour market reform passed in July 2017, alternative firm-level agreements on some of these details would not be recognised by courts, resulting in 4.4 million court cases pending (BNDES, 2017). The recent reform has provided more scope for firm-level agreements while keeping essential employee rights non-negotiable.

In the area of collective bargaining, the reform implements the principle of derogation of collective agreements and individual contracts above a certain pay threshold from the labour code. The reform allows derogation in a number of areas such as annual leave organisation, working time, incentive pay and other issues of internal flexibility. However, the minimum wage, the mandatory 13th salary, unemployment insurance and 27 other key employee rights explicitly remain non-negotiable. In addition, the reform lifts the obligation to pay affiliation fees to a union for formal workers and enhances the scope for outsourcing, which can now be done in all areas of activity of a company, while before it was permitted only for cleaning and security services.

In the area of employment protection for open-ended contracts, the reform introduces a new form of separation (by mutual agreement), which should result in lower compensation for workers and lower cost to employers with respect to dismissal without just cause. The reform also reduces the incentives for workers to file a complaint since the overall cost of the procedure is now charged to the losing party -either the employer or employee- with no more public financial aid, except in a few cases. Prior to the reform, essentially all costs of an employee’s complaint were covered by public money, regardless of whether the case was lost or won.

In principle, the labour reform should diminish legal uncertainty and litigation, thereby reducing labour costs. It will likely result in greater flexibility with advantages for both employers and employees. By regularising a number of de facto situations and reducing the cost of formal labour it might result in a reduction of informality, more inclusive growth and higher productivity. However, it will be important to ensure that outsourcing does not result in greater informality due to a possible higher prevalence of informal employment among subcontractors. In order to avoid this risk, sufficient resources should be given to the competent authorities to fight informality. Moreover, it will be important to evaluate the effectiveness of the reform after a few years and see if additional measures are needed to ensure a reduction in informality.

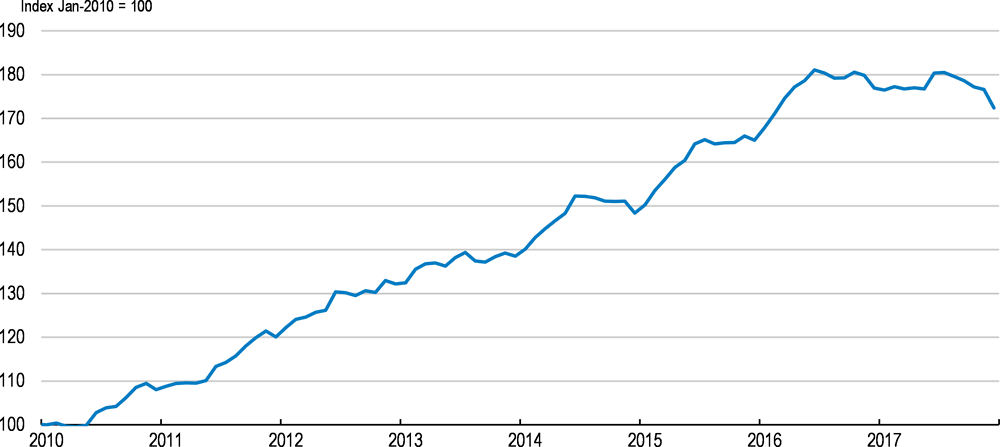

Labour costs, both wage and non-wage costs, have outpaced productivity for several years which has resulted in rising unit labour costs (Figure 1.15). This has eroded returns on capital among large firms, with concomitant effects on corporate savings and investment (Rocca and Santos Junior, 2014; Considera, 2017). Estimates suggest that 88% of the variation in average wages can be explained by changes in the minimum wage (Considera, 2017). The current rule for yearly adjustments of the minimum wage is based on the previous year’s inflation and GDP growth two years back and has led to real increases of 80% over the past 15 years. At 75% of the median wage, Brazil’s minimum wage is higher than in any OECD country by that measure (Figure 1.16). Allowing a progressive reduction of the minimum wage relative to the median wage by limiting future real increases would help to improve international competitiveness and reduce informality.

Figure 1.15. Unit labour costs have risen

Index January 2010=100

To ensure future wage developments that are compatible with strong investment and employment, the current minimum wage rule, which is set to expire in 2019, could be replaced by a rule that indexes annual minimum wage increases to the consumer price index for low-income households for some time. Such a rule would protect the purchasing power of minimum-wage earners, and imply reducing but not halting future real increases in the minimum wage.

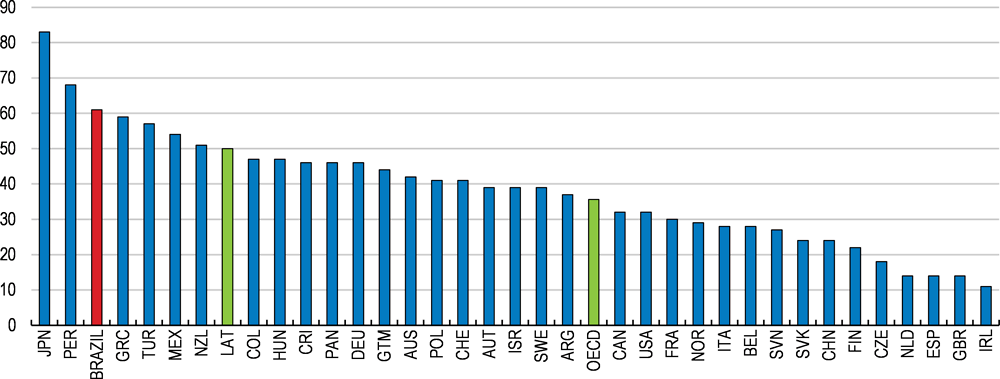

Figure 1.16. Minimum wages are high in international comparison

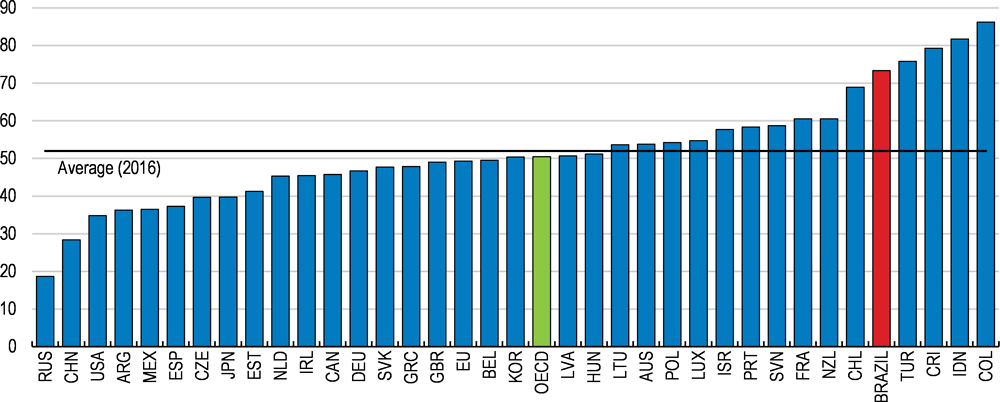

Minimum wage as a percentage of median wages, 2016¹

1. Exactly half of all workers have wages either below or above the median wage for the OECD countries. Percentage of minimum to average wage for Argentina, China, Indonesia and the Russian Federation.

Source: OECD, OECD Employment Outlook Database; China Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, National Bureau of Statistics; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios); International Labour Organisation (ILO) Database on Conditions of Work and Employment Laws; Ministry of Man Power and Transmigration of the Republic of Indonesia and Statistics Indonesia (BPS); Russia Federal State Statistics Service; National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina.

The federal minimum wage is defined only as a monthly payment, with no hourly equivalent. This severely limits the scope for low-wage earners to work part-time, or pushes work opportunities with less than full time into the informal sector. Given that the minimum wage is a binding floor for a large share of Brazil’s workforce, the lack of an hourly definition may have a significant impact. This may be particularly relevant for women, who are almost 5 times more likely to work part-time across OECD countries. Moving towards an hourly definition of the minimum wage would make it easier to combine work and childcare without losing the benefits associated to formal employment.

It is also important to note that individual states can set a state–level minimum wage above the federal level, which could be used to reflect differences in labour market conditions and productivity, across Brazilian states. Moreover, state-level minimum wages have no fiscal implications through linked social benefits, while the amount of the federal minimum wage acts as a floor for several social benefits.

Other labour market policies have rightly placed a priority on reducing gender and race gaps, including the 2012–2015 National Plan for Women and a 2014 law establishing race-based affirmative action in filling federal civil servant positions (World Bank, 2016). Just like income inequality, gender or racial discrimination tends to reduce growth and hold back development by crippling a part of society´s human capital.

Improving skills

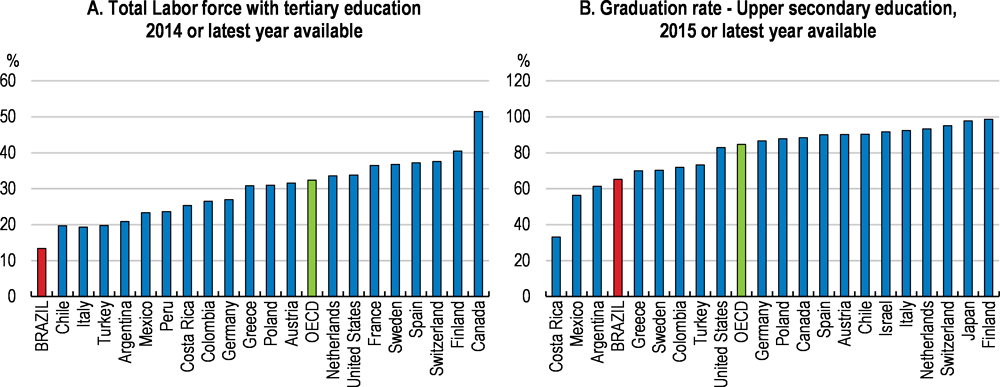

Brazil has progressed substantially over the last decades in facilitating access to education, but attainments and the quality of education remain low in international comparison (Figure 1.17). More than 50% of Brazilians have not attained secondary education, and 17% did not even complete primary education, well above the OECD average of 2%. Low performance on the OECD PISA tests suggests quality challenges, but also large disparities in outcomes depending on socio-economic background.

Figure 1.17. Skill gaps are significant

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators database; OECD Education at a Glance database; and UNESCO Education database.

Survey results suggest that employers are finding it particularly hard to find technicians, skilled trades and engineers (Figure 1.18). Empirical analysis suggests that a lack of skills is a significant factor behind low productivity levels (Arnold and Flach, 2018a). Wage premiums of up to 20% for those with technical training and of 120% for those with tertiary degrees reflect a dearth of skills (CNI, 2014b, OECD, 2016c).

Figure 1.18. Many firms struggle to fill jobs

Firms identifying difficulty filling jobs, 2015, in percent

Higher spending on education is not a guarantee for success; how money is spent is critical. In fact, Brazil increased spending on primary and secondary education by 58% per student between 2010 and 2014, while across OECD and partner countries it increased by 5% on average. But these increases in spending still need to translate into better learning outcomes. Other low-spending countries, such as Colombia, Mexico and Uruguay, spend less per student than Brazil does, and perform better (OECD, 2015a).

Many students in Brazil repeat grade and finally drop out of secondary education. Grade repetition has high costs and its benefits are highly disputed (Ikeda and García, 2014). Focusing on early and targeted support to those students with a higher risk of leaving the education system would be more efficient and produce better outcomes, as drop-outs often lack basic cognitive and social skills that are acquired during early childhood. Brazil has reached near universal enrolment of 5 and 6 years old but lags behind in the participation of younger children (OECD, 2017d). An education reform passed in December 2016 has provided some room for offering relevant content to the less academically inclined into secondary curricula by reducing the number of mandatory subjects. Inspiration for further reform could come from interesting experiences in some Brazilian state, such as the north-eastern state of Ceará, which have demonstrated the potential power of incentives and regular evaluations, together with teacher training and management support for schools (Box 1.2).

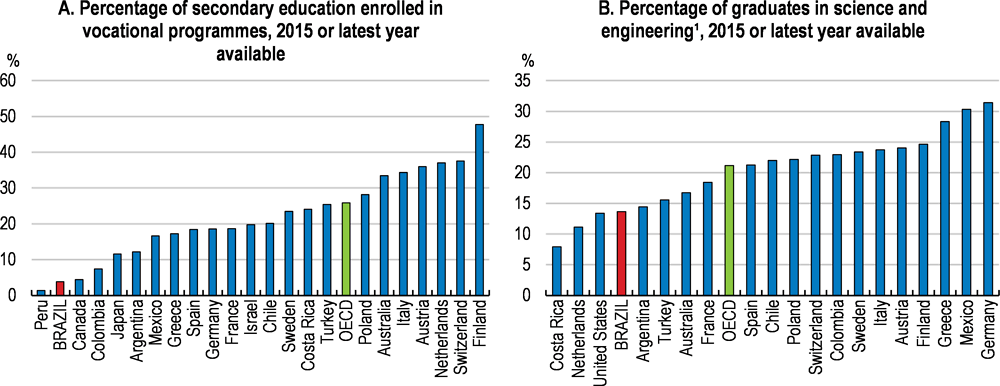

Enrolment in professional training and technical degrees is low in international comparison (Figure 1.20). Only 3.8% of secondary students choose technical courses, with the rest being academically focused. Brazil has started to address this issue by creating additional vocational training opportunities under the umbrella of the Pronatec programme. The programme has also contributed to gender equality, as 67% of participants have been women (World Bank, 2016). It has also supported youths, with 47% of participants being under the age of 29. While progress has been made, the programme has often missed labour market demands, as witnessed by dropout rates of above 50%. One reason for dropping out is that participants found a job in another industry than the one they were training for. Systematic consultations of local labour market and evaluations of labour market outcomes of participants of vocational education and training are therefore crucial to guide the supply of training courses, but have only recently been introduced. Demand-driven programmes initiated by requests from employers have proven significantly more effective in raising the chances of finding employment (O’Connell et al., 2017). Dropout rates are substantially lower in integrated secondary programmes with vocational content, suggesting that these may be avenues worth exploring further. Given that many Brazilians with training needs have already left formal education, it is crucial to ensure access to the Pronatec programme to adults that are either unemployed or looking for new opportunities.

Box 1.2. The power of incentives in education policies: Lessons from the state of Ceará

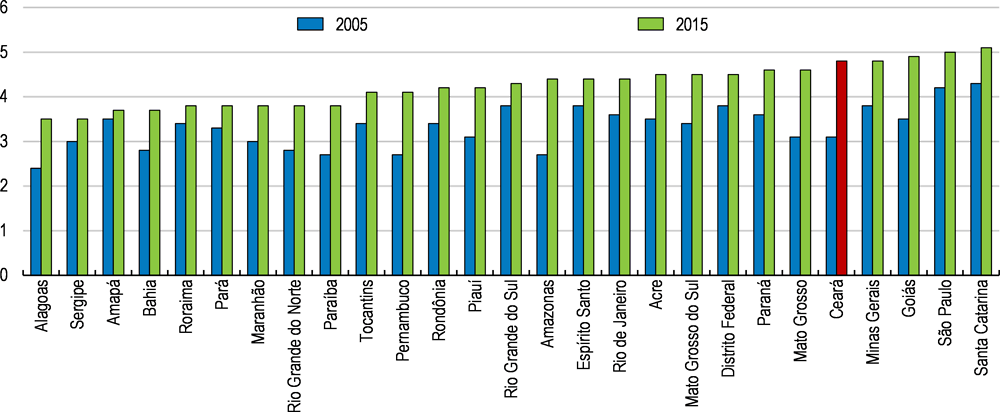

The experiences of some of Brazil’s states show that progress is possible with well-designed policies and good governance. Educational outcomes have improved visibly in the relatively poor north-eastern state of Ceará. Starting from a very low base, the state of Ceará has become one of the top performers with respect to the quality of education (Figure 1.19). This progress was based on an effective mix of increasing resources and introducing incentive mechanisms (OECD, 2011, Boekle-Giuffrida, 2012). Practices included an early extension of compulsory schooling to nine years, production and distribution of structured course materials to all schools and performance-based pay for teachers and principals, coupled with teacher training and management support for schools. The state of Ceará has even tied the distribution of consumption tax revenues across municipalities to educational outcomes, which created competition of municipalities for improving their schools. In all cases, incentive-based measures were coupled with periodic evaluations based on student test scores. It is likely that many of these local experiences could be successfully expanded nationwide.

Figure 1.19. The state of Ceará has made substantial progress in education quality

Basic Education Development Index (IDEB) by state¹

1. IDEB is a synthetic indicator of education quality, based on the academic passing rate and the results of student assessments for each municipality in Brazil.

Source: Observatório do Plano Nacional de Educação.

Figure 1.20. The share of students in vocational and technical programmes is low

2015

1. This includes all the tertiary graduates in the fields of Engineering, Manufacturing, Construction, Natural Sciences, Mathematics and Statistics.

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics

International experience suggests that workplace training and employer participation in the design and delivery of the training are key elements for a successful development of VET. Currently, training institutions are the dominant players of the Brazilian VET system and the involvement of employers is minimal. Giving employers a more central role, both in the design of courses and in the delivery of workplace training, would bring the Brazilian VET system closer to international standards.

On-the-job training could be expanded by eliminating distortions originating from the individual unemployment insurance account system FGTS. Given that dismissals or resignations disguised as dismissals are the usual strategy to access these accounts, less than 20% of jobs have a tenure of more than 2 years. These high job turnover rates significantly reduce incentives for employers to invest in training.

As in many OECD countries, there is also scope for a better alignment of university curriculums to the type of occupations prevailing on the labour market (OECD, 2017d). Deepening integration to the world economy, together with global trends such digitalisation, demographic shifts and other changes in work organisation are constantly reshaping skill needs, creating challenges for the education system, in particular universities, to update curriculums regularly (OECD, 2016c). The tertiary education system produces relatively few graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Sciences and Engineering account for 13% of graduates, below the OECD average of 20% or Mexico at 26%.

Reallocating spending from tertiary to earlier levels of education would also make spending both more inclusive and efficient. Students from high-income families are those who tend to reach virtually free public tertiary education in Brazil, while attendance of pre-primary education decreases the likelihood of low performance in secondary education for students from low-income households (OECD, 2016b).

Strengthening competition and shifting resources to firms with the best investment opportunities

Competition is key for creating incentives to invest and for allowing those firms with the best investment opportunities to thrive. However, policies such as entry barriers, directed lending, low integration into the global economy and targeted industrial policies have led to low competitive pressures in the Brazilian economy (Lucinda and Meyer, 2013; Clezar et al., 2011; World Bank, 2018).

For existing firms, low competition has reduced incentives to invest into the adoption of the most efficient production technologies, to introduce new innovative products and to reach global best practice (Pinheiro, 2013; IEDI, 2011; IEDI, 2014).

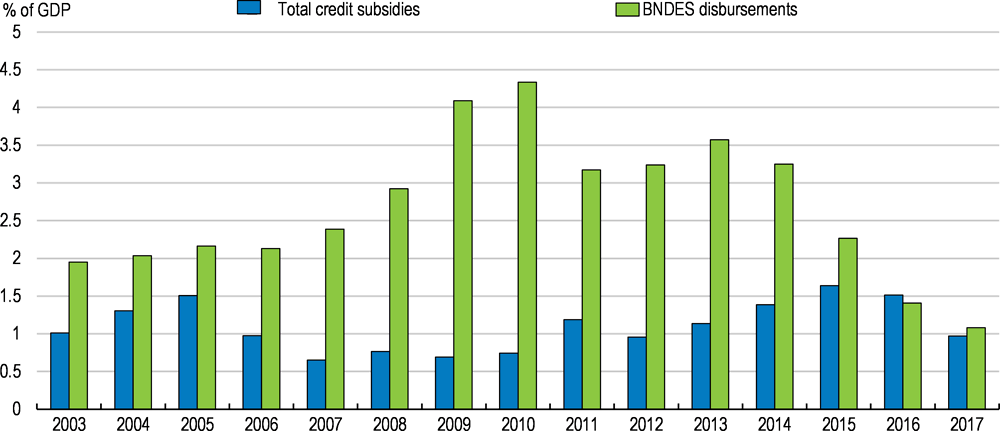

But besides affecting incentives for existing firms, such policies also affect entry and exit, and the reallocation of resources. Brazil’s policies towards the business sector have often tended to defend the status-quo rather than to accompany productivity-enhancing changes in industry structures. This has been the case for targeted industrial policies that conferred benefits, in the form of tax breaks or subsidies, to a handful of established incumbents at the expense of potential entrants. Targeted benefits also reduce the pressure for the exit of less productive firms, which is essential for releasing the resources that more successful firms need to grow to an efficient scale (Andrews et al, 2017). Subsidised directed credit has had a similar effect. Although financing conditions for incumbent and new clients are equal, incumbents with a standing business relationship with the national development bank BNDES probably found it easier to get access to subsidised loans than new entrants. Moreover, much of the directed lending volumes have flown to large firms up until 2015. In 2017, 42% of disbursements were to small and medium enterprises.

Low competition tends to foster rigid industry structures, characterised by low entry rates, and a misallocation of resources. Evidence suggests that reallocation mechanisms, including entry and exit, are an essential element of aggregate productivity growth (Hopenhayn, 1992; Melitz, 2003; Aghion et al., 2005). In fact, these reallocations can often account for a larger share of aggregate productivity growth than developments within individual firms (Olley and Pakes, 1996; Foster et al., 2001; Bartelsman et al., 2008; Andrews and Cingano, 2014). Those Brazilian firms with strong productivity growth are on average significantly younger and smaller than others (De Negri and Ferreira, 2015, Criscuolo et al., 2014).

Reallocation mechanisms do not seem to work well in Brazil, and it is often the less productive firms within a sector that enjoy large and even increasing market shares (Gomes and Ribeiro, 2015, OECD 2015c). Start-up rates in Brazil’s manufacturing sector are low in international comparison, and new firm entry has been on a constant decline over the last 15 years (Calvino et al., 2015). This has reduced profitable investment opportunities in potential new entrants, as some of those few firms that manage to enter the market tend to have particularly strong productivity and employment growth (Calvino et al., 2015). These firms would have significant investment opportunities. Instead of making full use of this potential, however, rigid industry structures have trapped resources in low-productivity firms with fewer investment opportunities, and with lower pay prospects for workers.

A boost to competition could come from lower barriers to market entry, but also stronger foreign competition as a result of lower trade barriers (see Chapter 2 of this Survey). In addition, policies to support the business sector should be mindful not to inhibit the natural selection process of firms and provide neutral treatment across incumbents and entrants, and across different sectors of activity. The OECD’s Competition Assessment Toolkit (OECD, 2010) can assist the government by providing a flexible methodology not only for identifying but also for revising policies that unduly restrict competition.

Brazil is using specific support policies in several areas. Brazil’s support policy for the information technology sector (Lei de Informática), for example, required foreign companies in the computer and information technology business to become minority partners in joint ventures with Brazilian firms and move production activities to Brazil in order to sell in the domestic markets. Only very few major companies did so. On the whole, the policy has not enabled Brazilian made computers or communication equipment to become globally competitive. The resulting price distortions may well have slowed down economic growth more generally, given the widespread use of information and communication technology throughout the economy (IDB, 2014).

Tax breaks for specific sectors can also distort relative prices across activities in the domestic markets. The Information Technology Law of 1991 allocates tax breaks worth BRL 5.5 billion per year to domestic electronics producers (almost 0.1% of GDP), but evidence suggests that it has failed to stimulate R&D or raise productivity in the sector (Kannebley and Porto, 2012). Tax benefits related to the Manaus Free Trade Zone located in the state of Amazonas, far away from major consumer markets, cost BRL 25 billion per year (0.4% of GDP), but no systematic analysis of the economic benefits of this tax expenditure has been made. While employment and industrial activity have risen in these special zones, the corresponding fiscal costs of USD 47 500 per job created are a multiple of workers earnings (World Bank, 2017).

Targeted policies are generally designed with learning effects in mind, but learning will only occur if their temporary nature is made clear from the very outset, ideally with a clearly defined phase-out schedule for specific support measures. Looking at the international experience, the temporary nature of support is what has often drawn a line between the structural upgrading achieved in East Asia and the creation of uncompetitive industries that remained dependent on public support. The Brazilian case illustrates that the political economy of withdrawing public support can easily become complicated if the temporary nature of the measure was not made clear from the beginning.

One example for the effect of local content rules can be seen in the case of equipment for generating electricity from wind and solar sources. Brazil’s unique geography and wind resources imply a significant comparative advantage for wind and solar energy (IRENA, 2013). The average capacity factor of the country’s wind farms, a measure of how much they actually produce compared with what they could produce under perfect wind conditions, is more than 50%, twice the world average (Abeeólica, 2016). However, local content rules (LCRs), some of which have been attached to financing from BNDES, have made wind turbines more expensive than in other emerging economies, such as India and China (IRENA, 2017). This has hampered investment in generation capacity. By raising prices, LCRs have led to the emergence of a domestic wind power equipment industry, but so far, there are no signs that this industry is becoming more competitive or could at some point survive without LCRs. In addition, the LCRs created upward price pressure on Brazilian steel, an industry that is dominated by a single supplier (Azau et al., 2011). Empirical evidence shows that LCRs have a significant detrimental effect on global investment flows in renewable energy sectors (OECD, 2015b). LCRs add also significant rigidity, which is especially detrimental in an industry such as the wind energy in which technology is evolving quickly and is dependent on global supply chains.

Horizontal policies to boost productivity across the economy have recently gained momentum. The government has launched a support programme called Brasil Mais Produtivo (More Productive Brazil) to help firms to adopt new technologies (MDIC, 2017). The program is being evaluated by the public-sector think tank IPEA, which is in itself a novelty, and has shown positive outcomes. Plans exist to scale it up. This is a move in the right direction to raise productivity without favouring specific sectors.

Attracting private investment into infrastructure projects

Infrastructure bottlenecks are acting as a drag on productivity, export performance and the integration of the domestic market. Infrastructure needs are sizeable in almost all sectors although they are most pronounced in transportation and logistics, and sanitation (Frischtak and Mourão, 2017). Brazilian companies suffer from high costs of transport and logistics, which reduce the profitability of many otherwise viable investment projects. For domestically oriented producers, infrastructure shortcomings limit the possibilities to exploit economies of scale, while exporters are put at a comparative disadvantage.

Brazil scores low in international rankings in terms of quality of infrastructure. It ranked at 116 out of 138 in the latest World Economy Forum ranking. Brazil scores have been persistently worsening over the last decade. Recent estimates put total infrastructure stocks at a value of 36% of GDP in 2016, while a reasonable mid-range infrastructure stock target for Brazil would be around 60% of GDP, which would still be far below international best practice (Frischtak and Mourão, 2017).

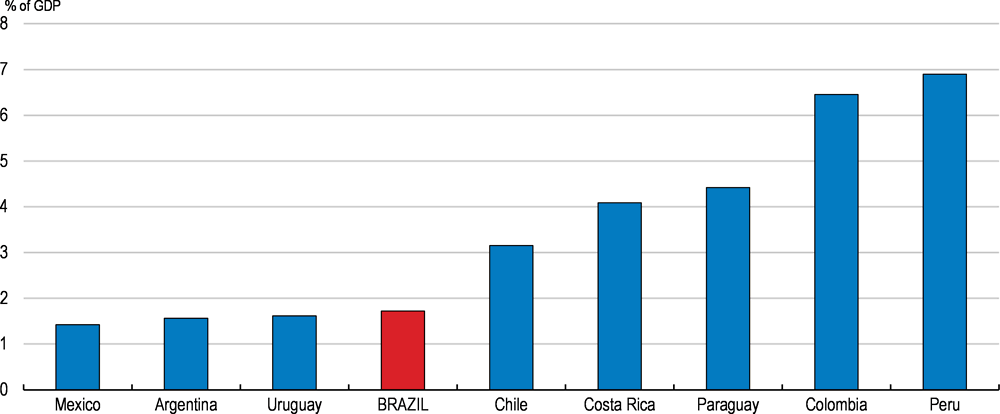

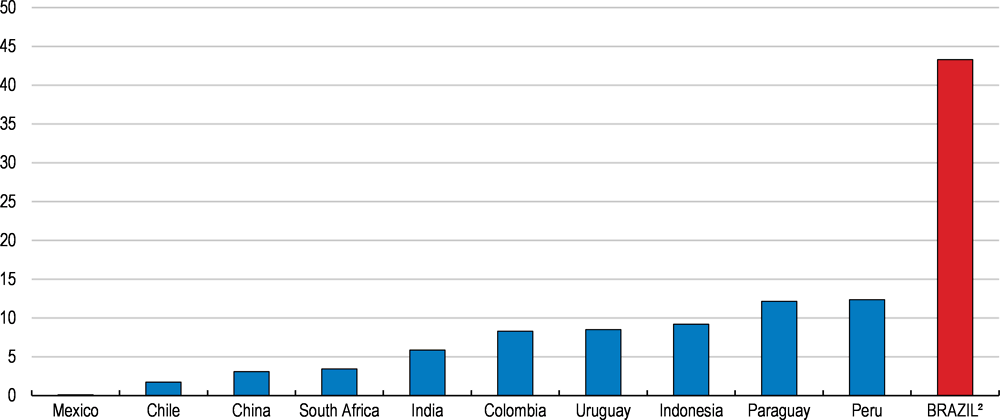

The relatively poor state of infrastructure reflects low spending over the last decades (Figure 1.21). Three decades of low infrastructure investment have left a strong mark, and compared to its significant needs in the area of infrastructure, Brazil still invests too little. Doubling infrastructure investment from currently around 2% of GDP to slightly above 4% of GDP would allow Brazil to reach this target over a period of 20 years (Frischtak and Mourão, 2017). By contrast, current levels of infrastructure investment are not even sufficient to offset depreciation, estimated to be around 3 per cent of GDP per annum (World Bank, 2016). While comprehensive comparable data are not available, existing evidence suggests7 that Brazil’s infrastructure investment has been well below the levels observed in other Latin America and emerging market countries, such as Chile, China and India (Calderón and Servén, 2010; Frischtak, 2013).

Figure 1.21. Investment in infrastructure is low

2015 or latest year

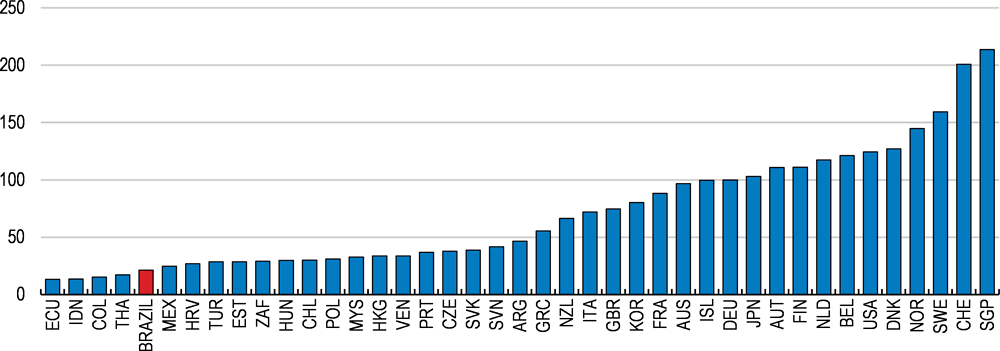

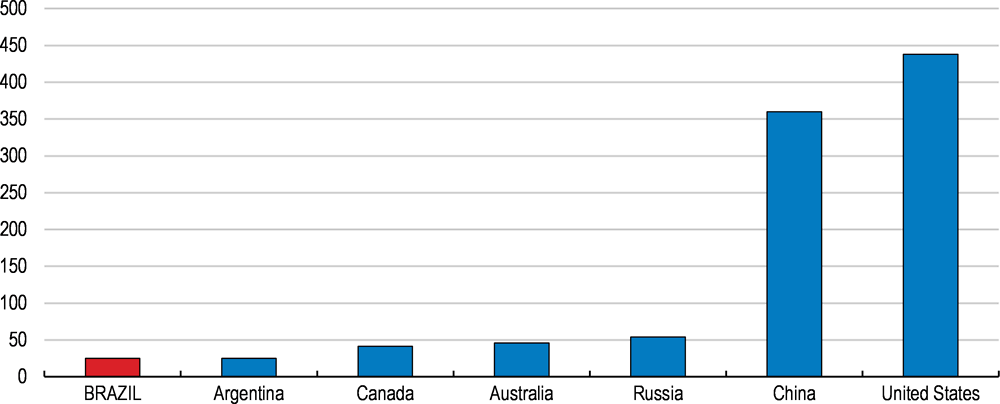

The impact of the lack of investment in infrastructure can be seen most clearly in transport. While Brazil scores lower than any of its main trading partners in all transport categories, road conditions are a particular bottleneck as two thirds of all cargo transportation is via road. Only 13.5% of the total road network in Brazil is paved and 8% has dual-carriage. This implies that Brazil compares poorly to other large countries and has a direct impact on logistic costs (Figure 1.22). For example, transport costs to export soy to China from Brazil are approximately USD 190 per ton, three times the cost from the United States. The difference is entirely accounted for by the cost of transport from the interior to the ports.

The relatively poor development of Brazil’s rail network also contributes to high transportation costs. Inter-urban railway transport, almost exclusively dedicated to cargo, has a relative low extension and has not increased since the 1950s (World Bank, 2016). In addition, the use of different gauges fragments the railway network. Rail transportation is particularly well-suited for high-volume, low-value-added commodities and most other commodity-producing countries use it extensively. By contrast, Brazil moves 60% of agricultural commodities by road, with only iron ore exports traveling predominantly by rail (Credit Suisse, 2013). This transportation mix limits export competitiveness, particularly given the poor state of roads.

Figure 1.22. Density of paved road network by country

Values in km / 1,000 km2

Entry regulations have contributed to the poor development of rail transportation. Although different operators exist, each of them has exclusive rights to a geographic area, which limits competition and investment. Providing better opportunities for entry on the basis of regulated access fees and allowing different franchisees to compete in the same area would allow economies of scale and reduce rail transportation costs.

Port operations are another aspect of transport infrastructure characterised by high costs and low efficiency. Governance shortcomings in public ports are reflected in the fact that the port of Santos, South America's largest port, recently had to restrict the loads of large vessels because the drainage had not been properly ensured by the public operating company (Financial Times, 20/8/2017).

Many public ports are suffering from underinvestment and inefficient management under public operating companies, which are proving hard to reform. Terminals are usually managed as private concessions, granted through public tenders. However, some contracts have been signed before the 1993 Ports Law and these have not gone through an open and transparent process. Concessions have often lacked well-defined investment commitments by concessionaires and have not led to a considerable expansion of port capacity. A tendency towards automatic renewals has failed to harness the benefits of competition. Public ports are also subject to a special labour regime under which port labour can only be contracted through a monopoly entity (OGMO) rather than hired directly under regular labour laws. Despite a reform in 2013, inter-port competition remains insufficient (Lodge et al., 2017).

The strategy to improve the current situation includes both an enhanced efficiency of publicly managed ports and new licenses for entirely private ports. While in the past, ports could only be managed by private companies if they would commit to providing 70% of the cargo volume through own merchandise, new port licenses can now be obtained without any vertical integration requirements. Given how difficult it is to reform public port operating companies, private ports may be a powerful option for raising port efficiency. Another strategy currently discussed is the privatisation of the public operated port companies (Companhias das Docas). The Central Government has conducted the necessary studies to implement the first privatisation of a public port company in combination with a service concession for a predetermined period, mimicking the successful airport concessions programme launched in 2011.

There is also significant scope to reduce red tape and bureaucratic obstacles facing port users. Despite some progress in selected areas, there is not generally a one–stop shop for all the permissions and payments required to dock, load and unload cargo in Brazilian ports. A recent initiative is the “Paperless port programme” based on an online system already in operation in all public ports. The system collects all required documents from various government agencies and reduces the administrative burden by eliminating paper forms and multiple repeated requests for the same information. It is still not a “one-stop shop” solution because it still lacks integration with customs procedures, but it has drastically reduced the time required for filling out paperwork.

Significant progress has been made with respect to the opening hours of government bodies such as customs, which now operate on a 24–hour basis. Still, customs clearance processes involve the work of several government agencies and take an average of two weeks. These long delays imply that a significant amount of space in the ports is used for storage areas. Storage fees have become an important and increasing source of revenues for the ports, creating clear incentives against speeding up the clearance process (World Bank, 2016).

One area of logistics that has not received much attention is cabotage, i.e. the shipment of goods by sea between domestic ports. Given that the bulk of Brazil’s population lives close to the coast and distances are large, cabotage could be a cost efficient means of transporting industrial goods. Some actions are being taken to streamline procedures. Cabotage shipments used to require the same documentation as international ones, which amounted up to 44 different documents. A joint task force of three ministries has revised many of the documentation requirements and substantially reduced administrative burdens. Still, significant room for further improvements remain. Currently, cabotage is overwhelmingly used for shipping mineral oils and metal ores, especially to servicing off-shore oil platforms. Both further progress in reducing administrative burdens and improvements in port infrastructure would help to exploit the potential of cabotage shipments.

The reduction in infrastructure investment is mostly explained by a decline in public investment, which is currently only around 0.9% of GDP and mostly concentrated on state-owned enterprises and highways built by states. Against the background of budget rigidities, rising mandatory spending and falling revenues, discretionary public investment expenditures have proven to be the only remaining margin of fiscal adjustment. Attempts of fiscal consolidations have almost always resulted in cuts to capital outlays, affecting significantly spending on infrastructure. The current fiscal situation implies that the funding available for public investment in infrastructure are unlikely to improve in the medium-term. Filling infrastructure gaps primarily through private financing will therefore become a key challenge and necessity.

Reviewing some of the regulations and practices for infrastructure projects could significantly accelerate private investment in infrastructure. Given the extremely limited fiscal space, the focus should be on improving the procedures for attracting private actors. Brazil can build on almost 20 years of experience, but reforms could improve the ability to tap into private funds, which has fallen short of other Latin American countries, in particular Chile.

Most private participation has been in the area of electricity and telecommunication, two areas where Brazil compares relatively well to other emerging economies in terms of regulation (Prado, 2012). This provides hope that better regulatory frameworks can attract more private investment if the framework conditions are improved. In roads and ports the focus of private participation has been on improving and managing existing infrastructure.

Getting the most out of concessions and PPPs

Concessions, whereby private partners are remunerated exclusively from user charges, have been the delivery model of choice in Brazil, whereas there are only few cases of public-private partnerships (PPPs), which involve payments from public entities. So far, these have mostly involved subnational governments. A greater use of PPPs as an additional tool would facilitate private sector engagement in a wider array of infrastructure projects, including those where user fees are hard to implement, such as sanitation or public lighting projects. However, in some countries, PPPs have been attractive in the past because the associated future liabilities were not properly recorded in the budget. As a lesson from these experiences, the full budget implications of PPPs over their whole life-cycle should be incorporated into the medium-term budget framework.

A key challenge for the public sector is to build up credibility through stable, well-defined and standardised procedures to reduce uncertainty and costs for investors. Despite a federal PPP law, policies and processes on how to prioritize, prepare, structure, and conduct bidding for PPPs vary widely across states (World Bank, 2016). Canada, for example, uses standardised bidding documents and guidance manuals for local governments (CCPP, 2011). Avoiding sudden changes in the contract terms, such as those that occurred in 2014 when the government tried to negotiate lower electricity tariffs in return for renovation of concessions without a new tender call, is also important for investors (OECD, 2015c, World Bank, 2016).

Improvements could also be made in the design, structuring and preparation of projects before the tender call. Expertise and technical capacity for project structuring tend to be scarce, particularly at the state and municipal levels. In many cases, insufficient planning and structuring has resulted in significant regulatory uncertainty, cost overruns and delays. Tenders for public works and concessions should be better prepared and include all relevant details and contingencies to make costs more predictable. This would imply dedicating more time and resources to the planning phase, which has often been cut short against the perception of urgency in delivering progress.

As a result of bottlenecks in structuring capacity, projects have regularly been structured by the same firms (or their subsidiaries) that later submit tenders (World Bank, 2016). This opens the door for anti-competitive behaviour such as selective passing on of information to affect competitors’ valuation of the contract or gauging technical requirements to exclude competitors from the tender. Such projects receive fewer bids and are often won by the firm engaged in the structuring. Some projects have even failed to attract bidders (World Bank, 2016).

By contrast, projects structured by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) or the recently founded structuring agency EBP (Estruturadora Brasileira de Projetos), a joint venture between public and private banks, have on average received 5 bids, similar to tenders in the UK, Canada and the EU, as compared to only one for projects structured by a bidder (Pinheiro et al., 2015). Competition among multiple bidders is key for maximising value for money and international experience shows that at a minimum, there should be at least three proponents with the ability and capacity to deliver. At the local level, there may be a need also for municipalities to proactively look for proponents beyond local boundaries.

Taking better account of physical, legal, environmental and judicial details and risks in the project structuring would also help to avoid costly renegotiations once a contract has been signed and competition can no longer be harnessed. Where risks exist that are beyond the influence of the private sector, the public sector should consider providing insurance or including the possibility of direct compensation payments into the contracts, rather than just contract period extensions or reduced investment requirements as in the past. These compensation regimes introduce significant uncertainty and discourage potential investors from bidding for certain projects.

Looking ahead, a diversification of the type of assets and services delivered by the PPP mechanisms, including healthcare, education, prisons, street lighting, and management of environmental and several other social infrastructure projects is likely (Infraescope, 2017). This diversification beyond traditional areas will exacerbate bottlenecks in technical capacity to appraise and structure projects and of insufficient bidders. The need to develop or bring technical capacity to government at all levels is therefore paramount and urgent. The benefits of providing more training to officials involved in infrastructure structuring would be substantial. The national development bank BNDES also has significant technical capacity that could be tapped into to support subnational governments in the structuring of infrastructure projects. BNDES already has a division for this, but the uptake of this available expertise by states and municipalities has been limited so far.

A new 2016 investment partnership law has created a new central entity attached directly to the presidency, tasked with selecting and prioritising projects and monitoring their implementation. The PPI Secretariat (Secretaria Executiva do Programa de Parceiras de Investimentos) is in line with international best practices and similar units exist in some OECD countries. It is fundamental that the PPI unit remain well resourced, both financially and in terms of human resources. The new law has also established a project preparation fund to finance and procure professional services to assist Brazilian contracting authorities in preparing and structuring projects.

Beyond the PPI unit, other measures should be taken to develop capacity and expertise across government. Independent external advisers, whether they are technical, financial or legal, can also bring deep transactional experience and understanding of the PPP landscape, especially at subnational level. Advisors should be involved throughout a project’s lifetime and can help to build government technical capacity over time. In Canada successful projects at municipal level have benefited from participation by external advisers (CCPP, 2011), which have ultimately proved to be an effective way to save government resources.

Transparency and accountability standards for PPPs and concessions must also be further developed in order to shield the mechanism against the kind of corruption cases that affected the infrastructure market in 2016. Otherwise the procurement process will become less competitive and it will be challenging to achieve value for money (Infraescope, 2017).

Improving sectoral regulation