Chapter 1 provides an overview of Ukraine’s economic performance, strengths and challenges at the subnational level. It analyses regional economic trends from the mid‑2000s to 2015-16 and compares them with those observed in OECD countries and beyond. This chapter, which updates the 2014 OECD Territorial Review of Ukraine, focuses on issues relevant to the decentralisation process, analysed extensively in Chapter 2.

Maintaining the Momentum of Decentralisation in Ukraine

Chapter 1. Regional development trends in Ukraine in the aftermath of the Donbas conflict

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Note by Turkey

The information in this document with reference to “Cyprus” relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Turkey recognises the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Turkey shall preserve its position concerning the “Cyprus issue”.

Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union

The Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Turkey. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

Introduction

The previous OECD Territorial Review of Ukraine (OECD, 2014b), completed just before the Euromaidan events and the eruption of a separatist conflict in the east of the country, concluded that Ukraine was both administratively and fiscally over-centralised. It argued that a more decentralised form of territorial governance was essential to making strength of the country’s size and diversity and to overcoming the much-discussed east-west divide, which was reflected not only in its politics but also in the structure and performance of regional economies. This report updates and extends that analysis. It argues that the geopolitical and economic shocks of recent years have had asymmetric impacts, both sectorally and geographically. To a great extent, they seem to have accelerated a number of trends that emerged in the years following the global financial crisis of 2009. The structural shifts that began after the financial crisis present new opportunities for some regions, especially in the west of the country, but daunting new challenges for others, particularly in the east, where the consequences of armed conflict have exacerbated an already difficult structural adjustment. The asymmetric nature of these shocks across Ukraine’s regions points to the need for a differentiated policy response and thus reinforces the case for more decentralised governance. However, it also underscores the importance – and difficulty – of getting decentralisation right, given the problematic institutional, political and economic environment in which it is being implemented.

The first section of this chapter provides an overview of the macroeconomic context and the state of ongoing structural reforms. The second analyses demographic and economic trends at subnational level, including the evolution of Ukraine’s settlement patterns, production structure and growth performance. This is followed by an analysis of key drivers of economic performance with a strong regional dimension: the functioning of labour markets, transport infrastructure and changes in the manufacturing sector. It formulates diagnoses and recommendations that are relevant to both central and subnational authorities. The final section looks at changing patterns of civic engagement and governance at the subnational level, which are important aspects of decentralisation in Ukraine.

Macroeconomic overview

Ukraine is the largest country in continental Europe and, with 42.6 million inhabitants in 2016,1 one of the most populous. Ukraine has access to the Black Sea mainly through ports in Odessa, Iuzhnoe (in Odessa oblast) and Mykolaiv. It has a comparative advantage in agriculture, particularly in grain production (it is among the top ten exporters of wheat and corn worldwide). Its approximately 320 000 km² of fertile arable land are equivalent to one-third of the arable land of the European Union (OECD, 2014b). Ukraine is also home to abundant mineral resources: it has the second-largest quantity of mercury deposits and sizeable reserves of coal (the seventh-largest in the world) and iron ores, mainly concentrated in Eastern Ukraine.

Ukraine has faced large challenges over the past decade. The global financial crisis hit Ukraine hard, with gross domestic product (GDP) falling by 15% in 2009 (Figure 1.1). The recovery that ensued was weak and short-lived, and gave way to a major economic, financial and political crisis that has been aggravated by the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk (the Donbas). GDP contracted by 16% in the two-year period from early 2014 to late 2015, while inflation surged, reaching a peak of 61% in April 2015; the exchange rate weakened; and the terms of trade deteriorated. The crisis of 2014-15 highlighted a number of fragilities inherent in the Ukrainian economy. Growth in incomes during the decade before the crisis was largely driven by favourable prices for commodity exports (particularly steel and chemicals) rather than much-needed improvements in productivity and competitiveness (OECD, 2014b). Consistent delays in implementing structural reforms and recurrent political instability left the economy stuck in transition and overly exposed to external shocks.

Figure 1.1. Selected economic indicators, Ukraine

Source: IMF (2017b), World Economic Outlook (database), https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2017/01/weodata/index.aspx (accessed April 2017).

With the introduction of a flexible exchange rate regime, strong fiscal and monetary policies, and essential energy and financial sector reforms, the economy appears to have returned to modest growth in 2016, with real GDP rising by an estimated 2.3%. The government took important steps to reduce the fiscal deficit, which reached 10% of GDP in 2014 (including the state-owned gas company’s deficit) before falling to 2.2% in 2016, thanks to tight fiscal policies and the imposition of market-based gas and heating tariffs. The external position also strengthened, with the current account deficit falling from 9.2% of GDP in 2013 to 3.6% in 2016. Gross reserves remain low but have doubled to USD 15 billion.

Continued recovery will depend on the government’s ability to address important structural weaknesses in the economy. Public debt has risen sharply and is forecast to reach 90% of GDP in 2017. To help restore external sustainability and strengthen public finances, the government negotiated a four-year USD 17.5 billion IMF Extended Fund Facility, which has been operational since March 2015. Continued IMF support remains contingent on the implementation of structural reforms to reduce public sector inefficiencies, improve the business environment, increase labour market participation and boost productivity. Reform priorities highlighted by the IMF include attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), reforming the state-owned enterprise sector, developing a market for agricultural land, accelerating anti-corruption efforts, improving fiscal sustainability, further reducing inflation and rebuilding reserves, repairing viable banks, and reviving sound bank lending. To improve medium-term fiscal sustainability, the IMF recommends further fiscal consolidation and the adoption of a comprehensive pension reform, including increasing the effective retirement age to address the pension fund’s large deficits and allow for higher average benefits (IMF, 2017a).

Over the past decade, Ukraine has made important efforts to open up its economy through trade and investment liberalisation. It became a member of the World Trade Organisation in 2008 and signed an Association Agreement with the European Union (EU) in 2014, including a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area, which entered in force on 1 January 2016. Exports to traditional markets in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) have declined markedly in recent years and the EU accounted for more than one-third of export revenue in 2015. In spite of the ongoing conflict, however, the Russian Federation still accounted for the largest share of Ukraine’s exports – at 13% in 2015, followed by Turkey (7.3%), the People’s Republic of China (6.3%), Egypt (5.5%) and Italy (5.2%). Imports predominately originate from the EU (41% in 2015) and CIS countries (28%; Figure 1.2).

Ukraine’s average tariff rate is not particularly high, and the tariff regime does not present a significant obstacle to increasing trade. However, addressing non-tariff barriers such as customs regulations and border clearance issues can play an important role in reducing trade costs (OECD, 2016c). Ukraine ranked 80th out of 160 countries in the 2016 World Bank Logistics Performance Index, scoring below the average for the Europe and Central Asia region across all six dimensions (customs, infrastructure, international shipments, logistics competence, tracking and tracing, and timeliness). Similarly, the 2017 World Bank Doing Business assessment ranked Ukraine 115th out of 190 economies in the trading across borders dimension, which measures the time and cost of logistical procedures associated with exporting and importing goods. Ukraine also came out below the average for the Europe and Central Asia region on 10 out of 11 dimensions of the 2015 OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators. Performance is particularly weak in the areas of governance and impartiality, internal and external border agency co-operation, and document formalities.

Figure 1.2. Evolution of exports, Ukraine

Ukraine’s exports are dominated by primary commodities, particularly agricultural products (cereals) and base metals (iron and steel). The global economic slowdown and ongoing conflict have had a severe impact on the steel industry – base metals constituted 42% of exports in 2008 but just 26% in 2015. By contrast, the share of primary agricultural products has nearly tripled, from 12% in 2008 to 32% in 2015 (Figure 1.3). Exports of sophisticated manufactures are minimal and mainly consist of railway cars, aircraft parts and components, and car parts, predominantly oriented towards the Russian market. The recent adoption of a flexible exchange rate has allowed for a substantial devaluation of the Ukrainian hryvnia (UAH) against the dollar, which has helped to maintain demand for Ukrainian exports. Given the country’s exposure to international markets, weak internal demand, and constraints on labour and capital supply, ensuring a sustained recovery in the long term will require concerted efforts to diversify the export base, attract FDI and support Ukraine’s integration in global value chains.

Figure 1.3. Composition of exports, Ukraine

FDI inflows increased rapidly after the turn of the century, from USD 600 million in 2000 to USD 10.7 billion in 2008. However, Ukraine has faced substantial difficulties in attracting FDI since the onset of the global financial crisis. Gross FDI inflows declined by 55% in 2009 and recovered slightly in 2010-12, before dropping by a further 45% in 2013 and a staggering 81% in 2014, reflecting growing concerns around the escalating conflict in the Donbas and the unstable domestic political situation. A sharp rebound was observed in 2015, bringing FDI inflows up from USD 847 million to USD 3.05 billion. However, this was largely due to the recapitalisation of foreign-owned banks through debt-to-equity conversions (OECD, 2016c). Furthermore, FDI statistics should be treated with a certain degree of caution, due to the prevalence of investment by special purpose entities2 and round tripping (when funds transferred abroad by domestic investors are returned to the home country in the form of direct investment). The extensive use of round tripping is visible in the high share of offshore and low-tax jurisdictions such as Cyprus3, the Netherlands and the British Virgin Islands in the total inward FDI stock (44% as of 31 December 2015).

FDI can play an important role in upgrading Ukraine’s ageing capital stock, supporting job creation, increasing productivity, and facilitating the transfer of knowledge and new technologies. However, Ukraine has faced difficulties attracting FDI in high value-added and technology-intensive sectors. Foreign investors have mainly targeted the domestic market through investments in non-tradable sectors such as financial and insurance activities (27% of the total inward FDI stock in 2015), wholesale and retail trade (13%), and real estate (8%). FDI in manufacturing is highly concentrated in metallurgy (12% in 2015), which is strongly influenced by commodity price fluctuations and global economic conditions. Moreover, inflows predominantly consist of mergers and acquisitions, and there is a need to facilitate efficiency-seeking greenfield investments that will foster the development of export-oriented activities (OECD, 2016c).

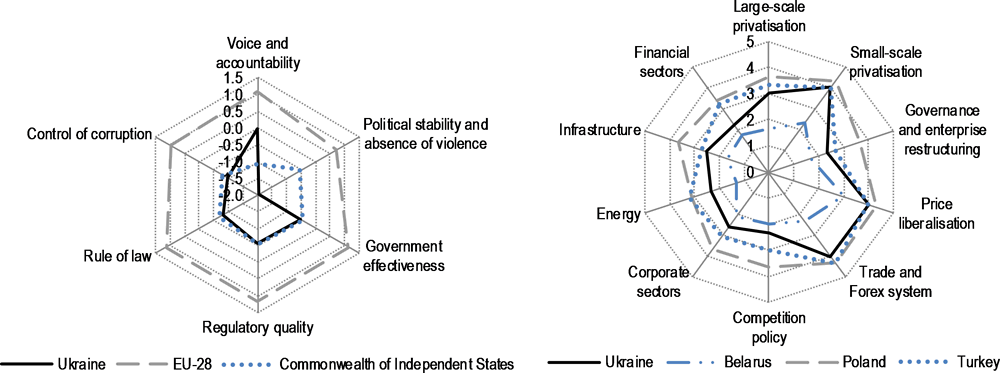

With GDP per capita in PPP terms standing at just 21% of the EU average in 2015, Ukraine needs a long-term strategy to accelerate growth and facilitate sustainable improvements in living standards. Currently, efforts to diversify the structure of exports and attract FDI are stymied by the poor investment climate, weak institutions and endemic corruption. There is, therefore, a pressing need to accelerate the pace of structural reforms in order to support productivity growth, particularly in light of the rapidly ageing population and the gradual decline of the working-age population. Figure 1.4 shows important gaps in Ukraine’s performance across key areas of structural reform, particularly when compared with the EU and benchmark countries such as Poland. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators highlight political instability, corruption and the rule of law as the three most important issues. According to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Transition Indicators, the most crucial priorities include financial sector reforms, governance and enterprise restructuring, competition policy, and energy sector reforms.

There is a broad consensus that reforming the Ukrainian economy will require significant improvements to the integrity and efficiency of public institutions. General government expenditure, which stood at 49% in 2012, has been declining, to a projected 41% in 2016 – but even this is a very high level for a country at Ukraine’s level of per capita income. The public sector accounts for 25% of total employment. Privatisation and the reform of inefficient state-owned enterprises are needed to foster competition and reduce the influence of large and oligarchic business conglomerates. Creating a business environment conducive to competition will also require streamlining the legal and regulatory framework, strengthening the judiciary, and tackling systemic corruption. Corruption remains one of the most significant impediments to doing business, with Ukraine ranking 131st out of 176 economies in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2016.

Chart A Chart B

|

Sources: World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#reports (accessed May 2017); European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2014), “Transition report 2014: Innovation in transition”, www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/transition/tr14.pdf.

Improving the policy environment for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is also necessary to support local development and allow the emergence of a more vibrant and diversified private sector. Access to finance remains a key constraint on SME development, due to the prevalence of high interest rates and collateral requirements, heavy dollarisation of the financial system, high levels of non-performing loans, and the lack of alternative sources of financing. The government should also focus on improving institutional support for SMEs, encouraging innovation through co-operation with research institutes, and supporting the development of linkages between multinational enterprises and domestic companies. The introduction of a targeted export promotion programme could also help Ukrainian SMEs to reap the benefits of the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area with the EU (OECD et al., 2015).

Subnational trends

The political and economic shocks of the last few years have affected regions very differently

The country’s administrative structure (Table 1.1) is a legacy of the Soviet era, but is undergoing a significant reform discussed in detail in Chapter 2. According to the 1993 Constitution, Ukraine comprises:

At the TL2 level4, 24 regions (oblasts), the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and 2 cities with special status and prerogatives: Kyiv (the capital) and Sebastopol.

At the TL3 level, 490 districts (rayon) in rural and suburban areas, and 184 cities of oblast significance. These are the largest cities – with very few exceptions their population is greater than 10 000 inhabitants.

At the municipal (lowest) level, the territory is made up of more than 10 000 local councils: rural councils, councils for urban type settlements and councils of small cities (called cities of district significance) located within a district.

Table 1.1. Ukrainian administrative units as of 1 December 2017

|

TL2 level (oblast) |

Districts (TL3) (rayon) |

Cities with oblast significance and special status (TL3) |

Other cities |

Unified territorial communities1 |

Rural councils |

Councils of settlements of urban type |

Councils of urban districts2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ukraine |

490 |

186 |

235 |

665 |

9 411 |

719 |

47 |

|

Crimea (Aut. Rep.) |

14 |

11 |

5 |

– |

243 |

38 |

3 |

|

Vinnytsya |

27 |

6 |

8 |

33 |

658 |

28 |

|

|

Volyn |

16 |

4 |

6 |

39 |

355 |

19 |

|

|

Dnipropetrovsk |

22 |

13 |

5 |

53 |

231 |

33 |

15 |

|

Donetsk |

18 |

27 |

24 |

9 |

239 |

75 |

9 |

|

Zhytomyr |

23 |

5 |

7 |

45 |

530 |

35 |

2 |

|

Zakarpattya |

13 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

302 |

19 |

|

|

Zaporizhia |

20 |

5 |

8 |

34 |

223 |

19 |

|

|

Ivano-Frankivsk |

14 |

6 |

8 |

20 |

420 |

22 |

|

|

Kyiv |

25 |

13 |

13 |

6 |

601 |

28 |

|

|

Kirovohrad |

21 |

4 |

5 |

13 |

368 |

27 |

2 |

|

Luhansk |

18 |

14 |

23 |

8 |

195 |

87 |

4 |

|

Lviv |

20 |

9 |

34 |

33 |

590 |

31 |

|

|

Mykolayiv |

19 |

5 |

3 |

21 |

285 |

17 |

|

|

Odesa |

26 |

7 |

10 |

23 |

402 |

31 |

|

|

Poltava |

25 |

6 |

7 |

32 |

427 |

19 |

3 |

|

Rivne |

16 |

4 |

6 |

24 |

314 |

15 |

|

|

Sumy |

18 |

7 |

6 |

27 |

351 |

19 |

|

|

Ternopil |

17 |

4 |

9 |

40 |

426 |

8 |

|

|

Kharkiv |

27 |

7 |

10 |

12 |

376 |

59 |

|

|

Kherson |

18 |

4 |

5 |

24 |

255 |

30 |

3 |

|

Khmelnytskiy |

20 |

6 |

4 |

33 |

368 |

13 |

|

|

Cherkasy |

20 |

6 |

8 |

24 |

516 |

14 |

|

|

Chernivtsi |

11 |

2 |

8 |

22 |

224 |

7 |

|

|

Chernihiv |

22 |

4 |

7 |

33 |

508 |

25 |

2 |

|

City of Kyiv |

– |

1 |

– |

||||

|

City of Sebastopol |

– |

1 |

1 |

– |

4 |

1 |

4 |

1. Newly amalgamated communities result from the merger of local councils. This table includes only local councils that have not merged into an amalgamated community.

2. Twenty-four large cities (including Kyiv and Sebastopol) are further divided into city districts.

Source: OECD research based on Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (2017), Адміністративно - територіальний устрій України (Administrative and territorial system of Ukraine), http://static.rada.gov.ua/zakon/new/NEWSAIT/ADM/zmist.html.

Ukraine is currently engaged in amalgamating (merging) these numerous local councils into larger municipal entities called unified territorial communities (UTC). This amalgamation process is one of the pillars of the decentralisation reform. All statistics and comparisons with OECD countries in this chapter are based on the TL2 level (oblasts and cities of Kyiv and Sebastopol) and in a few cases on the TL3 level (districts and cities of oblast significance).

While population is ageing and declining, its concentration remains lower than in most OECD countries

The median population density of Ukraine’s TL2 regions (63.4 inhabitants per square kilometre [km²]) is somewhat lower than the median density of TL2 regions in OECD countries (87.6 inhabitants/km²). Ukraine has a relatively low concentration of population across TL2 regions, meaning that the population is relatively dispersed across all regions. Only three OECD countries (the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovak Republic) have a lower population concentration (Figure 1.5). Many countries in Central and Eastern Europe, such as Bulgaria and Romania, also display low population concentration. The concentration of population increased slightly during 2005-15. The fact that it is still much lower than in OECD countries could reflect both the Soviet legacy of territorial planning and a relatively low rate of interregional labour migration: relatively few workers in Ukraine move to opportunity (i.e. to more affluent regions with better job prospects) (World Bank, 2015). Overall, the low concentration index of population compared to OECD countries suggests that there is still room to increase the size of Ukraine’s largest urban clusters, with substantial benefits for Ukraine’s productivity if urban growth is adequately managed.

Figure 1.5. Geographic Concentration Index of population among TL2 regions, 2015

* Twenty-five OECD countries for which 2015 population data are available.

Note: Geographic Concentration Index formula detailed in Annex 1.A.

Sources: State Statistics Service of Ukraine, Demographic database; OECD (2017c), “Regional demography”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 7 April 2017).

Ukraine has experienced population ageing and population decline since independence in 1991. During 2000-16, the working-age population (i.e. 15-64 year olds) fell by 7.8%, while the population as a whole fell by 8.1%. Ukraine’s population is already older than those of most OECD countries: the 65+ age group accounted for 21% of the population in 2016. Among OECD countries, only Germany, Greece, Italy and Japan had a higher share of residents aged 65 and more the same year, while the OECD median reached 17.7%. As illustrated by Ukraine’s age pyramid in 2016 (Figure 1.6), this trend is expected to continue and even amplify in the coming years, because the relatively large cohorts now in their 50s will soon be replaced by much smaller cohorts born in the 1990s and early 2000s. According to both Ukrainian5 and UN population projections, the overall population will drop by approximately 7-8% over the 2015-30 period (UNDESA, 2015). Another striking feature of Ukraine’s demography is the higher number of females compared to males in the age ranges 35-39 and older (Figure 1.6). Indeed, men have significantly higher mortality rates6 than females after the age of 35: this results in a very high gender gap in life expectancy at birth (around 10 years, i.e. 76.2 years old for females versus 66.4 for males).

Figure 1.6. Age pyramid of Ukraine, 2016*

* Without Crimea and Sebastopol.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Population ageing and population decline have widely varying effects across regions and cities. Out of Ukraine’s 27 TL2 regions, only Kyiv city, and two oblasts in the north-west (Volyn and Zakarpattya) experienced demographic growth during 2007-17. Population in the Eastern and Central-East regions, such as the Donbas, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia, and the north-eastern regions of Sumy and Poltava has been both declining and ageing more rapidly than Ukraine as a whole, with the exception of Kharkiv – Ukraine’s second-largest urban agglomeration, and the only region in the east to benefit from significant positive net migration. In Western Ukraine, the rural border oblasts of the north-west (Volyn and Rivne) and several regions of the Carpathians (south-west) had roughly stable populations, chiefly because of higher fertility rates. No Ukrainian region has a total fertility rate higher than the population replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman (Figure 1.7). Kyiv city and (to a lesser extent) the surrounding Kyiv oblast are the main destinations of interregional migration flows, and their populations are growing rapidly. In Kyiv oblast, this growth is strongest in cities close to Kyiv and thus belonging to the Kyiv urban agglomeration (such as Bucha, Boryspil and Brovary).

Strong demographic decline, be it through low fertility rates or net migratory outflows, or both, are most evident in Eastern and Central Ukraine (Figure 1.7). Regions in the lower left quadrant are the most likely to experience the strongest population decline in the near future, given that they combine low fertility rates and net migratory outflows. Another striking feature is that net migration tends to be positive in oblasts hosting the largest urban agglomerations in Ukraine, such as Kharkiv, Odessa and Lviv, though to a lesser extent. Given the scale of population decline in many regions,7 regional and urban development strategies of Ukrainian oblasts and city master plans need to take more into account future population decline and population ageing and assess its impact on public services, urban infrastructure and regional labour markets.

More generally, however, the accuracy of population statistics is problematic in Ukraine. This is due in part to the fact that a large share of the population does not actually reside at its place of permanent registration, leading to distortions in official statistics regarding the spatial distribution of the population (Box 1.1). These distortions result in an inadequate allocation of public funds because subvention and transfers (such as the healthcare subsidy) to local budgets, as well as the fiscal equalisation mechanism, are tied to official population numbers (CEDOS, 2017). To solve this issue, one priority should be to conduct the next population census as soon as possible (for instance, in 2018 instead of 2020) to provide an accurate picture of the spatial distribution of the population. In the medium term, an overhaul of the residence registration procedure (Ukr. Propiska) is necessary for registration statistics to more accurately reflect internal migration patterns.

Figure 1.7. Regional demographic trends, Ukraine

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Urban agglomerations are drivers of economic and demographic growth

Overall, 80% of Ukrainian cities experience population decline, and are disproportionately concentrated in Eastern Ukraine while growing cities are disproportionately found in the west. In traditionally rural Western Ukraine, many regions are still urbanising, driving the demographic growth of many medium-sized cities and of Lviv city. Rural-urban migration is still a significant factor in urban growth in Western and (to a lesser extent) in Central Ukraine. Unsurprisingly, economic and demographic growth are associated: the 22% of Ukrainian cities that are characterised by growing economic activity (using satellite night lights as a proxy) also record lower declines in population than other cities, or even population growth (World Bank, 2015). Population growth in Kyiv and other cities in Central and Western Ukraine could be positive for national economic development, by fostering further agglomeration economies (Box 1.2). However, for urban growth to translate into enhanced prosperity, it must be managed well (i.e. a scaling up of public services and infrastructure to ensure the integration of newcomers) (World Bank, 2015). Conversely, it is important that public service plans and urban planning in shrinking places take falling population densities into account, as these phenomena create challenges in maintaining and operating urban infrastructure due to decreasing economies of scale. The combination of an overall ageing urban population and declining fertility rates will also likely shift demand from education to health services (World Bank, 2015).

Box 1.1. Population statistics and residential registration (Ukr. Propiska)

The State Statistics Service of Ukraine compiles all official population figures on the basis of administrative data from birth and death certificates and data on permanent residence registration from the State Migration Service of Ukraine. The number of residence registrations and residence “deregistration” with the State Migration Service is the basis to take into account migrations, particularly migrations between different territorial entities. However, several studies based on household surveys found that a major share of the population does not register their actual place of residence. According to a 2010 survey of 1 216 households conducted in 12 regional centres, more than a third of respondents declared that their actual place of residence did not match their permanent residence registration. The Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies used indirect methods to assess Kyiv’s population at the beginning of 2010 and 2011: it found that the actual population of Kyiv is higher than the official estimate, with a difference ranging from 3% to 22% depending on the year and assessment method.

Existing research points to internal labour migrants as the main category that does not register officially, and is therefore not adequately accounted for in official population and migration statistics. According to an International Organisation for Migration survey conducted in 2014-15, the number of internal labour migrants in Ukraine would reach 1.6 million people (without Crimea, and Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts), equivalent to around 4.4 % of the population and 10.4% of the employed population of the survey regions (i.e. excluding Crimea, and Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts). The current system of residence registration hinders the registration of internal labour migrants at their new place of residence due to the complicated procedure which creates obstacles for people who live in households not owned by them or their family members. Indeed, the rental housing market is small and largely informal in Ukraine, and landlords usually refuse to allow their tenants to officially register with the State Migration Service. Migrants not officially registered at their place of residence often face obstacles accessing various administrative and social services, accessing public healthcare, or participating in local elections.

These issues with permanent residence registration translate into substantial inaccuracies and distortions in official statistics regarding the spatial distribution of population. This is compounded by the lack of a recent national census. Indeed, national censuses usually provide a reliable basis for official population estimates and statistics. However, Ukraine conducted its last national census in December 2001: therefore data on natural growth (births and death certificates) and migrations (residence registrations) play a decisive role in shaping official population statistics.

Sources: Solodko, A., A. Fitisova and O. Slobodian (2017), “Residence registration in Ukraine: Issues for public governance and consequences for society” (“Reєstracіja mіscja prozhivannja: vikliki dlja derzhavi ta naslіdki dlja suspіl’stva”; in Ukrainian), www.cedos.org.ua/uk/migration/reyestratsiya-mistsya-prozhyvannya-v-ukrayini-problemy-ta-stratehii-reformuvannia; IOM (2016a), “Migrations as a factor of development for Ukraine” (“Mіgracіja jak chinnik rozvitku v Ukraїnі”; in Ukrainian), www.iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/mom_migraciya_yak_chynnyk_rozvytku_v_ukrayini.pdf.

Box 1.2. Agglomeration economies: Costs and benefits

Large urban agglomerations and dynamic medium-sized cities have enormous potential for job creation and innovation, as they are hubs and gateways for global networks such as trade or transport. In many OECD countries, labour productivity is measured in terms of gross domestic product per hour worked and wages are seen to increase with city size. Stronger productivity levels are a reflection of the intrinsic value of being in a city, known as the agglomeration benefit. On average, a worker’s wage increases with the size of the city where he/she works, even after controlling for worker attributes such as education level. OECD estimates suggest that the agglomeration benefit in the form of a wage premium rises by 2-5% for a doubling of population size (Ahrend et al., 2014).

Higher productivity is due in part to the quality of the workforce and the industrial mix. Larger cities on average have a more educated population, with the shares of both very high-skilled and low-skilled workers increasing with city size. A 10 percentage-point increase in the share of university-educated workers in a city raises the productivity of other workers in that city by 3-4% (Ahrend et al., 2014). Larger cities typically have a higher proportion of sectors with higher productivity, such as business consulting, legal or financial services, etc. They are also more likely to be hubs or service centres through which trade flows and financial and other flows are channelled. These flows typically require the provision of high value-added services.

Living in a large city does provide benefits, but it also has disadvantages (Figure 1.8). While productivity, wages and the availability of many amenities generally increase with city size, so do what are generally referred to as agglomeration costs. Some agglomeration costs are financial: for example, housing prices/rents and, more generally, price levels, are typically higher in larger cities. In addition, a number of non-pecuniary costs, such as pollution, congestion, inequality and crime, typically also increase with city size, while trust and similar measures of social capital often decline. Survey data from European cities confirm that citizens in larger cities – despite valuing the increased amenities – are generally less satisfied with the other aspects mentioned, notably air pollution. To some extent, city size is the outcome of a trade-off between agglomeration benefits and agglomeration costs.

Figure 1.8. Agglomeration costs and benefits

Sources: OECD (2014a), OECD Regional Outlook 2014: Regions and Cities: Where Policies and People Meet, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201415-en; Ahrend, R. et al. (2014), “What makes cities more productive? Evidence on the role of urban governance from five OECD countries”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz432cf2d8p-en.

Cities in all regions have been losing population, mostly to the largest urban agglomerations, which are concentrating the little urban demographic growth that has been taking place in Ukraine. The largest urban centres also display higher productivity per capita and per km2, based on night light measurements (World Bank, 2015). The Kyiv agglomeration is the most prominent example. Kyiv city (2.9 million inhabitants at the beginning of 2017), the largest city in Ukraine, is also one of the fastest growing (0.7% per year during 2007-17). Kyiv attracts significant net population inflows from the rest of Ukraine. Since 2011, Kyiv oblast has also attracted significant net migration inflows (including from Kyiv itself) and its population has been growing again. This demographic growth is concentrated in the cities surrounding the capital, and in the neighbouring rural districts. This suggests that the Kyiv urban cluster is increasingly becoming a large urban agglomeration that spans across administrative units, encompassing both Kyiv city and many areas of Kyiv oblast. World Bank (2015) confirms this by measuring Kyiv’s urban footprint through satellite night light data. The urban footprint of Kyiv city has expanded to merge with the surrounding city and form an urban agglomeration encompassing 11 cities.8 These cities usually have separate geographic and political boundaries and initially had separate markets as well, but they grew together as they developed: their urban footprint was separate from Kyiv in 1996 but they have grown to become a single urban footprint in 2010 (Figure 1.9).

Satellite night light studies tracing the evolution of urban footprint found that 11 out of the 15 largest cities in Ukraine are part of an urban agglomeration (World Bank, 2015). Furthermore, urban agglomerations in Ukraine are not limited to central cities and their suburban secondary cities. Rural districts (rayon) on the outskirts of large cities (such as Kiev-Sviatoshyn rayon to the west of Kyiv or Ovidiopol rayon to the south of Odessa) often displayed higher growth than the central city to which they are functionally related, suggesting a pattern of peri-urban growth. As in OECD countries, urban agglomerations in Ukraine often encompass different administrative units. The OECD-EU definition of functional urban areas (FUAs) allow for a more accurate delimitation of urban areas as functional economic units, which can be a good basis to co-ordinate public policies across administrative entities (Box 1.3). Efficient co-ordination among subnational governments responsible for the same urban agglomeration (core city, suburban secondary cities, rural districts experiencing peri-urban growth and oblast administrations) is critical to the efficiency of subnational public investment, as explored in Chapter 2 of this review. Therefore, applying the OECD-EU definition of FUAs to Ukraine could inform the current municipal amalgamation process, particularly around the largest cities.

Figure 1.9. Kyiv’s agglomeration night light urban footprint, 1996-2010

Note: Agglomerations are defined using night light data and are formed by cities that in 2013 had a merged night light urban footprint.

Source: World Bank (2015), “Ukraine: Urbanization review”, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/213551473856022449/Ukraine-Urbanization-review.

Regional economic performance: Along with Kyiv, western regions are now the main drivers of national growth

Following the Euromaidan revolution and the political transition in the spring of 2014, the armed conflict that erupted in the Donbas area has resulted in the relocation of an estimated 1 million people from the conflict area (UNOCHA, 2016). Box 1.4 provides more details on internally displaced persons (IDPs) and the impact of the conflict on Ukraine’s regions. Furthermore, the Russian Federation’s subsequent trade and transit restrictions against Ukraine, together with the countermeasures adopted by Kyiv, have had a severe impact on industrial activities in Eastern and Southern Ukraine, particularly machine building.

Box 1.3. The OECD-EU definition of functional urban areas

The OECD-EU definition of functional urban areas (FUAs) consists of very densely populated urban centres (“city cores”) and contiguous municipalities with high levels of commuting (travel-to-work flows) towards the core municipalities (“commuting zones”). This definition resolves previous limitations for international comparability linked to administrative boundaries. FUAs are computed by combining geographic (cartographic) information about the administrative boundaries of municipalities and census data at the municipal level. Defining urban areas as functional economic units can help guide how national and city governments plan infrastructure, transport, housing and schools, and space for culture and recreation. Improved planning will make these urban areas more competitive, helping to support job creation and making them more attractive for its residents.

The methodology identifies urban areas as functional economic units, with densely inhabited “city cores” and commuting zones whose labour markets are highly integrated with city cores. In the first phase, the distribution of the population at a fine level of spatial disaggregation – 1 km2 – is used to identify the urban clusters, defined as contiguous aggregations of highly densely inhabited areas (grid cells) with an overall population higher than 50 000 inhabitants. High-density grid cells have more than 1 500 inhabitants per km2 (1 000 inhabitants per km2 in Canada and the United States). City cores encompass all municipalities where at least half of the municipal population lives within the urban cluster.

The commuting zones of these internationally comparable city cores are defined using information on travel-to work commuting flows from surrounding municipalities. Municipalities sending at least 15% of their resident employed population to a city core are included in its commuting zones, which thus can be defined as the “worker catchment area” of the urban labour market, outside the densely inhabited core. The size of the commuting zones relative to the size of the city core gives a clear indication of a city’s influence on surrounding areas.

The definition is applied to 30 OECD countries* and identifies 1 198 urban areas of different sizes. Among them, 281 metropolitan areas (including 81 large metropolitan areas of more than 1.5 million inhabitants) have a population higher than 500 000 and are included in the OECD Metropolitan Database. As of 2014, they accounted for 49% of the OECD overall population, 57% of gross domestic product and 51% of employment. Other FUAs include 411 medium‑sized urban areas (with a population of between 200 000 and 500 000) and 506 small urban areas (50 000-200 000). Digital maps and details about functional urban areas in each country are available at: www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/functionalurbanareasbycountry.htm.

The OECD has already applied the OECD-EU Methodology of functional urban areas to non‑member countries such as Colombia and Kazakhstan. For instance, the OECD Urban Policy Review of Kazakhstan found that the country contained 26 FUAs in 2009, among which 3 metropolitan areas (Astana, Almaty city and Shymkent). Applying this methodology requires a high degree of co-operation between the OECD and the national statistical office and the existence of inter-municipal travel-to work commuting flow data in the national census database.

* Data are not available for Iceland, Israel, New Zealand and Turkey.

Sources: OECD (2016b), “Functional areas by country”, www.oecd.org/gov/regional-policy/functionalurbanareasbycountry.htm; OECD (2016e), OECD Regions at a Glance 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/reg_glance-2016-en; OECD (2012), Redefining “Urban”: A New Way to Measure Metropolitan Areas, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264174108-en.

Box 1.4. The regional impact of the Donbas conflict and internally displaced persons

The Donbas conflict saw intense fighting in the eastern oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk (the Donbas area), until a fragile ceasefire was brokered in February 2015. According to the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, the total death toll is estimated to be at least 10 000, with at least 23 455 people injured. The conflict caused tremendous economic damage and the loss of at least 1.6 million jobs in the Donbas area alone, mainly in heavy industry sectors (mining, machine building and metals) and in services. In 2016, industrial production in government-controlled areas of Donetsk oblast amounted to only 47% of its 2013 (pre-conflict) volumes, and only 27% of 2013 volumes in government-controlled areas of Luhansk oblast.

Firms located in separatist territories were at the epicentre of the war and endured the most damage. An estimated 78% of the industrial capacity in Donetsk is located outside of the government-controlled areas, and the estimate is higher in Luhansk (84%). Economic activity in government-controlled areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts was also severely affected: between 2013 and 2015, gross domestic product per capita fell by 58% in real terms in government-controlled areas of Donetsk oblast and by 70% in Luhansk. Industrial facilities still in operation are extremely vulnerable to any sort of escalation of the conflict. Beyond that, non-government controlled areas (NGCA) were economically integrated with nearby regions of Ukraine (particularly in Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia oblasts), where many industries suffered from supply chain disruptions, for instance in the energy (coke plants for electric power and heat generation) and steel subsectors that both relied on coal supplies from mines in the NGCAs. The unofficial economic blockade and subsequent ban on all trade (except humanitarian assistance) with the NGCAs in early 2017 (as well as the separatist takeover of Ukrainian assets located in the NGCAs) broke the already weak economic ties of the NGCAs with the rest of the country. This further disrupted manufacturing activities in nearby regions in 2017.

The Russian Federation’s annexation of Crimea and the conflict in the east also triggered a massive influx of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Entire families abandoned their homes and fled to government-controlled areas. It is estimated that around 1 million IDPs reside permanently in government-controlled territory, while several hundred thousand more live in the NGCA while periodically entering government-controlled territory to claim pension and social assistance payments. The actual number of IDPs is unclear, because some do not register at all. Three-quarters of the IDPs are registered close to their homes, above all (40%) in government-controlled areas of their oblasts of origin. Outside of the Donbas, the neighbouring oblasts of Kharkiv, Zaporizhia and Dnipropetrovsk received the most significant influx of IDPs (amounting to more than 4% of their 2016 populations in Kharkiv and Zaporizhia). Many IDPs also moved to the city of Kyiv and the surrounding oblast, which offers good employment opportunities in the service and trade sectors. The impact of IDPs on regional labour markets, and their ability to find new jobs matching their skills is a key issue for host regions.

Figure 1.11. Registered internally displaced persons (share of regional population), January 2017

* Many internally displaced persons register in these oblasts while still residing in the non‑government controlled areas: these figures therefore overestimate the actual number of permanent internally displaced persons.

Source: Ministry of Social Welfare, State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

The government has been providing some emergency housing to IDPs and a very limited welfare payment (UAH 884 – approximately USD 35 – for individuals unable to work, half of that for the others) for a six-month period. It should be noted that pensioners make up a large share of registered IDPs (more than half of the IDPs registered by the Ministry of Social Welfare), but many of them still live in the NGCAs. The government has recently tightened the rules to register as an IDP (for instance, IDPs shall not reside in the NGCAs for more than 60 days) and introduced checks and controls to ensure that the IDPs actually live at their stated places of registration, resulting in the suspension of pensions and social payments for some.

In the government-controlled areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, the influx of IDPs led to rapid population growth in cities such as Kramatorsk, Severodonetsk and Sloviansk. There is evidence that the influx of IDPs led to a rise in rental prices. The IDPs have complained about the high level of refusals on the side of lessors due to mistrust of IDPs and about inadequate quality of rental housing. The IDPs face challenges to find employment: according to the International Organization for Migration Monitoring Survey, only 31% of IDPs who worked before displacement could manage to find jobs at their new places of stay. Given the severe economic downturn in government-controlled areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014 and 2015, the Donbas conflict resulted in a concentration of IDPs in host areas that are poorly prepared to receive them.

Sources: UNOCHA (2016), “Ukraine 2017 humanitarian response plan”, https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/humanitarian_response_plan_2017_eng.pdf; European Union, World Bank and United Nations (2015), “Ukraine recovery and peacebuilding assessment: Analysis of crisis impacts and needs in Eastern Ukraine”, http://www.un.org.ua/images/documents/3738/UkraineRecoveryPeace_A4_Vol2_Eng_rev4.pdf; Smal, V. (2016), “A great migration: What is the fate of Ukraine’s internally displaced persons”, https://voxukraine.org/en/great-migration-how-many-internally-displaced-persons-are-there-in-ukraine-and-what-has-happened-to-them-en; IOM (2016b), “National monitoring system of the situation with internally displaced persons: March‑June 2016”, www.iom.org.ua/sites/default/files/iom_nms_cumulative_report_eng.pdf.

In addition to the Donbas conflict and its consequences, regional economic specialisation and international metal prices were major factors determining the economic performance of Ukrainian regions after 2004. Prior to the global crisis in 2009, Ukraine enjoyed sustained economic growth, while Kyiv and the surrounding oblast grew consistently faster than most other regions. Affluent industrial regions in the Donbas and Pridneprovsky areas also contributed significantly to national growth. Meanwhile, poorer agricultural regions in Central and Western Ukraine failed to converge towards the national level in terms of GDP per capita and productivity (OECD, 2014b).

Figure 1.12. Contribution to national growth*, Ukraine, 2004-14

* The contribution of Luhansk (-18.1%) and Donetsk (-45.5%) reflect the negative impact of the Donbas conflict on these regions. 2014 growth rates do not take into account territories controlled by separatists. National growth has been adjusted to reflect the absence of data for Crimea and Sebastopol after 2013.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

After 2010, the geographic pattern of development reversed: Western regions have generally fared better than industrial strongholds in Eastern Ukraine. A clear “growth cluster” emerged in Central and Central-Western Ukraine, comprising Vinnytsya, Ternopyl, Khmelnitsky and Zhytomyr oblasts to the west of Kyiv and Cherkasy and Kirovohrad oblasts to the south of Kyiv (Figure 1.11), along with the Kyiv urban agglomerations itself (Kiyv city and the Kiyv oblast). These rural regions of Central and Western Ukraine, which display lower productivity than the national average, became the main contributors to national economic growth (Box 1.5). By contrast, affluent industrial regions, such as Zaporizhia, Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Poltava, as well as the Donbas area, entered in a recession as early as 2012 and therefore were a drag on national GDP growth (Figure 1.11). The recession was driven by low metal prices on international markets, but also structural issues related to declining heavy manufacturing subsectors (metals, mining and machine building), such as an outdated capital stock and a lack of investment (Saha and Kravchuk, 2015). The Donbas conflict, of course, made matters much worse in the east (Figure 1.11). The Donbas was already underperforming before the conflict began: like in other industrial strongholds of Ukraine, its GDP has contracted continuously since 2012. Meanwhile, some Western and Central regions (Vinnitsa, Zhytomyr, Volyn and Ternopyl) benefited from the growth of “light” industrial subsectors such as food processing, automotive parts and wood processing. As a result, during the 2004-14 decade economic growth was extremely concentrated in a few fast‑growing regions in Ukraine compared to many OECD countries (Box 1.5).

Box 1.5. Low spatial concentration of GDP, but highly concentrated GDP growth

The Geographic Concentration Index of gross domestic product (GDP) (a measure of geographic concentration of economic activities) across Ukraine’s TL2 regions (31.4%) is somewhat lower than the OECD median (Figure 1.12), although as one could expect it to be higher than the Geographic Concentration Index for population (Figure 1.5), reflecting agglomeration economies. In a majority of OECD countries, economic activity is more spatially concentrated than in Ukraine.

Figure 1.13. Geographic Concentration Index of GDP in TL2 regions, 2014

Notes: Data for Japan, New Zealand and Switzerland for 2013. The OECD median is for 22 OECD countries for which 2014 data are available. Geographic Concentration Index formula detailed in Annex 1.A.

Sources: State Statistics Service of Ukraine, regional GDP database; OECD (2017a), OECD Regional Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 7 April 2017).

In spite of a geographic concentration of GDP that is lower than many OECD countries, GDP growth has been extremely concentrated in recent years, i.e. national aggregate GDP growth has relied upon a handful of regions only. From 2004 to 2014, the six oblasts with the highest GDP growth rate (Ternopyl, Cherkasy, Zhytomyr, Vinnytsya, Kirovohrad, Kyiv oblast and Kyiv city) accounted for 93.5% of national GDP growth. Among 21 countries (19 OECD countries, Bulgaria and Romania) with available data, only Denmark displayed a higher concentration of economic growth among TL2 regions (Figure 1.13). In the case of Ukraine, this high spatial concentration is due to: 1) the dismal economic performance of the largest regional economies located in the east, in the conflict-ridden industrial Donbas of course, but also in Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia oblasts, even before the beginning of the Donbas conflict; 2) the strong economic dynamic of Kyiv city and Kyiv oblast (these two regions accounted for 60% of national growth during the 2004-14 decade).

It is worth noting that, if the same calculation is done for 2004-13, excluding 2014 when the Donbas conflict happened, the same oblasts still accounted for around 70% of national growth (dashed line). Thus, even before the conflict, Ukraine displayed a high level of spatial concentration of economic growth compared to OECD countries.

Figure 1.14. Contribution to national GDP growth by the fastest growing TL2 regions, 2004-14

Note: The regions with the highest GDP growth are included until the equivalent of one reaches a threshold of 20% of the national population.

Sources: OECD research based on State Statistics Service of Ukraine (2017), National Accounts database, https://ukrstat.org/en/operativ/menu/menu_e/nac_r.htm (accessed 28 March 2017); OECD (2017c), “Regional demography”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a8f15243-en; OECD (2017d), “Regional economy”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/6b288ab8-en.

In Ukraine, the main driver of regional disparities during the last decade has been the strong growth of the Kyiv metropolitan region. Kyiv city alone accounted for 50% of Ukraine’s aggregate GDP growth during 2004-14, even though its share of national GDP was only 18.4% in 2004. Kyiv oblast was the second-largest contributor to national growth (Figure 1.14). Together, Kyiv city and the surrounding oblast accounted for almost 60% of national growth; their combined share of Ukraine’s nominal GDP increased from 22% in 2004 to 28% in 2015. This clearly points to the strong dynamics of the capital’s urban agglomeration, which benefits from powerful agglomeration economies (see Box 1.2). Ukraine displays a high concentration of economic growth in the capital’s urban agglomeration by OECD standards, but this situation is not unique: in France and Chile, the metropolitan capital regions accounted for 59% and 55% (respectively) of national economic growth during the same period. Capital regions also accounted for 70% of national growth in Romania and Bulgaria.9

This dominance of the metropolitan capital region with a core-periphery pattern of development is actually widespread among European Neighbourhood Policy countries10 (with the partial exception of Belarus and Morocco). Metropolitan regions benefited greatly from a catching-up process in market services in all the transition economies, and capital regions generally did best of all, as the main seats of central public services and higher education and research facilities. They all benefited from being the most attractive to FDI inflows and to the most educated part of the population because they typically hosted the central offices of the main domestic and foreign firms and had the best transport connections domestically and to foreign destinations. In Ukraine, the experience of Kyiv fits into this paradigm very well given its level of economic development and ongoing structural changes arising from economic integration with advanced European partners (Petrakos, Tsiapa and Kallioras, 2016). Therefore, it is expected that Kyiv agglomeration will continue to be a strong growth driver for the country in the near future.

Figure 1.15. Contribution to growth vs. share of GDP, Ukraine, 2004-14*

* 2014 growth rates do not take into account territories controlled by separatists. National growth has been adjusted to reflect the absence of data for Crimea and Sebastopol after 2013.

Source: OECD calculations based on State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Differences in the performance of individual sectors had a clear impact on the spatial distribution of economic growth. After an impressive expansion prior to the 2009 crisis, manufacturing stagnated and then suffered a deep downturn (Figure 1.15). The financial sector also shrank after years of rapid expansion in the 2000s, while the 2014-15 reduction of households’ real incomes depressed retail and service activities. By contrast, high value-added business services recovered after the global crisis, beginning in 2012, but declined in 2014-15. Since 2009, the agriculture and fisheries sector has demonstrated the most consistent growth (Figure 1.15). These patterns of development clearly favoured Kyiv agglomeration (high-end business services) and regions with agricultural specialisation.

The analysis of productivity growth during the decade to 2014 illustrates these patterns (Figure 1.16). OECD (2016d) uses a specific catch-up indicator based on the idea that a region needs to grow faster than the national frontier (the regions with the highest productivity levels) in order to reduce its productivity gap. In Ukraine, the national frontier is composed of Kyiv city and Poltava oblast. This allows us to differentiate three groups of regions: 1) catching-up regions (where productivity grew faster than the national frontier); 2) regions keeping pace with the frontier’s productivity growth; 3) diverging regions, where productivity growth was lower than the frontier or even negative (catch-up indicators and a detailed explanation are available in Table 1.B.1 in Annex 1.B). Most of the regions catching up with the national frontier specialise in agriculture (although some have benefited from light manufacturing, such as Zhytomyr); Ivano-Frankivsk in Western Ukraine is the only agricultural oblast in the diverging group. The decline in productivity in this region with a productivity level among the lowest in Ukraine is atypical and poses a challenge to Ukraine’s regional development policy. By contrast, all regions specialised in mining and heavy manufacturing have been diverging (Figure 1.16). In many cases, regional productivity growth may also have benefited from population shrinking (because the capital per worker ratio increased in the short term), but this is likely to be reversed in the long run, as declining demography reduces incentives for investment and negatively impacts on GDP growth (World Bank, 2015).

Figure 1.16. Real gross value added by sector (index, 2004=100)

* Professional and technical activities (legal, accounting, engineering, R&D and architecture services).

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Figure 1.17. Annual productivity growth across Ukraine’s regions, 2005-14

* Frontier regions (regions with the highest GDP per employee accounting for no less than 10% of employment).

Notes: Productivity is defined as regional GDP per worker. The strong decrease in productivity in 2015 is not reflected on this graph.

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine, National Accounts and Employment series.

Interregional disparities are high and keep increasing, partly because of the Donbas conflict

Economic inequalities among regions are high in Ukraine compared to most OECD countries. The dispersion of GDP per capita across regions as measured by the Gini Index of TL2 regions is comparable to OECD countries with high territorial inequalities, such as Mexico or the Slovak Republic (Figure 1.17). It is also close to countries in Central Europe, but much lower than in the other large post-Soviet countries.11

Since 2004, interregional economic disparities in Ukraine have increased substantially (Figure 1.17). During 2004-14, the interregional Gini Index of GDP per capita rose from 22.3 to 25.1 in Ukraine, a larger increase than was observed in any OECD country except Australia (which has far lower levels of territorial inequality). In 2015, the interregional Gini Index rose again to 26.7 because of the armed conflict and severe economic downturn in Donbas, which caused GDP per capita to fall well below the national average in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

Figure 1.18. Gini Index of GDP per capita in TL2 regions, 2014

* Twenty-one OECD countries for which 2014 data are available, excluding countries with less than four TL2 regions.

Sources: OECD research based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine and OECD (2017a), OECD Regional Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en (accessed 16 February 2017).

The rise of interregional economic disparities in Ukraine is not unique. Like other transition countries, Ukraine inherited significant territorial imbalances from the Communist era: Southern and Eastern Ukraine were specialised in mining and manufacturing (machine building, steel and chemical sectors) and by 1989 had reached a higher level of urbanisation than the Central and Western regions. After the deep economic recession of the 1990s, interregional inequalities in GDP per capita increased continuously from 2000 to reach a peak before the 2008 financial crisis (OECD, 2014b). The rise of territorial inequalities during the 2000s is a common pattern among many European Neighbourhood Policy countries (Petrakos, Tsiapa and Kallioras, 2016). Many Central and Eastern European countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 (particularly Bulgaria, Romania and the Slovak Republic) experienced a similar pattern. In Central Europe, rising territorial inequalities were often associated with intense structural change in the economy, economic convergence with more advanced EU members and the strengthening of the metropolitan capital region. This may be related to some extent to a broader empirical regularity known as the “Williamson curve” (Box 1.6), which suggests that interregional disparities may grow as incomes rise up to a relatively high level, only to decline thereafter.

Box 1.6. Is the Williamson curve applicable to transition economies?

Rising interregional disparities in Ukraine reflect in part an observed regularity discussed in the literature on economic geography since the 1960s – the so-called “Williamson curve”. Williamson (1965) extended the Kuznets hypothesis, which describes the relationship between income inequality and development, to the explanation of regional disparities. Kuznets found that income inequality tended to increase at low levels of per capita income and to decrease at higher levels of development, forming an inverted “U” shaped curve (Kuznets, 1955).

Williamson found a similar pattern at the regional level: national development created increasing regional disparities in the early stages of development, but later on it led to regional convergence, resulting in an inverted U-shaped curve. The primary explanation for Williamson’s finding is that, in a catching-up country, a few regions typically drive growth, and capital and skilled workers are increasingly drawn to them. Rapidly rising productivity causes growth to accelerate still further in these regions, leading to increasing regional disparities. Given the importance of agglomeration economies and the fact that rising investment goes with increasing concentration, there is an obvious link with urbanisation here: fast-urbanising regions will tend to pull away from others. At later stages, higher factor costs and/or agglomeration diseconomies emerge in the leading regions, prompting capital to shift to places where the potential returns to capital deepening are higher (i.e. those with lower capital per worker). Knowledge spillovers and a shift from a growth model driven by capital deepening to one more dependent on human capital may also play a role in this reallocation of productive factors.

Recent research on Central and Eastern Europe suggests that the Williamson curve (or regional Kuznets curve) may not (yet) apply to transition economies. Monastiriotis (2014) compares regional convergence in labour productivity in EU-15 and the ten Central and Eastern Europe countries (CEE) that joined the EU in 2004. His research suggests that while CEE countries faced rising regional disparities, there has so far been no “return to regional convergence” at higher income levels. At comparable levels of development, regions in the EU-15 were already converging. However, since those processes took place a generation or more ago, the countries of the EU-15 were much closer to the leading economies than the CEE-10 are today; in short, they are still converging economies at national level, moving closer towards the international productivity frontier. Monastiriotis concludes that, despite strong growth up to 2009, CEE economies could still be in a phase of development and restructuring where cross-regional inequalities become more acute and persistent. In other words, non-convergence would be attributable to “centripetal forces” instigated by the process of transition.

For Ukraine, this leaves open the question of when the Williamson turning point might be reached. It is possible that even a resumption of strong growth would only lead to a reduction in interregional disparities over the longer term. However, provided that growth is strong and broad-based, both geographically and sectorally, it could provide a boost to prosperity even in lagging regions. It is, moreover, clear that the war in the east has reinforced interregional disparities; a settlement of the conflict could contribute to their rapid reduction, at least to pre-war levels, if not below.

Sources: Williamson, J.G. (1965), “Regional inequality and the process of national development: A description of the patterns”; Kuznets, S. (1955), “Economic growth and income inequality”; Monastiriotis, V. (2014) “Regional growth and national development: transition in Central and Eastern Europe and the regional Kuznets curve in the east and the west”, https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2014.891156.

In Ukraine, high economic growth in the Kyiv urban agglomeration, boosted by the strong dynamic of the tertiary sector (notably financial intermediation and real estate), was the driving force of widening economic disparities among regions, a pattern that was reinforced by the crisis in the east of the country (Figure 1.18). It is not clear whether Ukraine reaching a higher level of economic development will favour a more equal allocation of income across its territory in the near future. However, it should be noted that Ukraine has mechanisms to stimulate the growth of lagging regions, such as the formula-based allocation of funds by the State Fund for Regional Development.12

Figure 1.19. Gini Index of GDP per capita in Ukraine’s TL2 regions

* For 2014 and 2015, Crimea is not included due to a lack of data.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

Economic disparities between Ukraine’s regions have also increased from the standpoint of households. The dispersion index of real disposable income per capita has been on an upward trend since 2002, with a sharp increase in 2014-15 (Figure 1.19). This increase in dispersion is in great part driven by higher growth of real disposable income per capita in Kyiv compared to the national level. However, real disparities in material well-being are lower once the substantial differences in the cost of living across regions are accounted for: price levels are higher in prosperous regions. For instance, there is a rather good correlation (63%) between the price of wheat bread and available income per capita in each region. The largest disparities in price levels across regions are observed in the non‑tradable sector, particularly real estate prices and rents, which is as one would expect. Nevertheless, the material well-being sub-index (part of Ukraine’s official regional development index),13 which attempts to measure material living standards beyond household monetary income, also suggests an increasing dispersion in material well-being across Ukraine’s regions (Figure 1.19). Unfortunately, the index is not available for Kyiv city, and therefore underestimates interregional disparities.

In contrast to real disposable income per capita, the dispersion in real wages fell during the 2000s, up until 2014. It is likely that wage adjustments to economic shocks take place largely in the informal labour market, including through the practice of unregistered wages (OECD, 2014b).

Tackling obstacles to growth across Ukraine’s regions

Regional growth can be influenced by a myriad of interconnected factors such as amenities, geographic location, demographics, size, industry specialisation and agglomeration economies. Like national growth, regional growth is dependent on the availability of inputs – capital, labour and land. The supply of labour is unlikely to support economic growth in the medium term: Ukraine’s active population is gradually decreasing and projected to decrease by around 39% up to 2060 because of low fertility and widespread out-migration (Kupets, 2014). However, improving the functioning of regional labour markets can help mitigate the effects of population ageing and the gradual decline of the working-age population.

Figure 1.20. Regional dispersion trends in Ukraine

*. Base year: 2002.

** The material well-being index is a component of the regional Human Development Index published by the State Statistics Service of Ukraine and Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies. It is a composite index of material living standards in each region. It encompasses monetary poverty; the availability of durable consumption goods; and the relative purchasing power of households, GDP per capita, and the share of households able to save money or invest in real estate.

Notes: The dispersion index is measured as the sum of absolute differences between regional and national values, weighted with regional share of population and expressed as a percentage of the national value. For 2014 and 2015, Crimea is not included due to missing data.

Sources: OECD research based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine (2014), Regional Human Development Index, http://idss.org.ua/ukr_index/irlr_2014_en.html (accessed 28 March 2017) and National Accounts of Ukraine, www.ukrstat.gov.ua (accessed 15 January 2017).

Labour productivity growth is a key driver of performance among OECD regions (OECD, 2016d). Increasing labour productivity in Ukrainian regions from its currently low level (10% of the EU-28 average) is critical to support sustainable economic growth. Beyond labour markets, this would require an improvement in external and internal connectivity, through modernisation of the outdated manufacturing sector, and sustained investments to upgrade the country’s transport infrastructure (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4).

Improving the functioning of Ukraine’s labour markets should be a priority

As a result of the 2014-15 economic downturn, the unemployment and youth unemployment14 rates in 2016 reached their highest levels since 2005 (9.3% and 16%, respectively). The 2014-15 recession led to a drop in employment and a sharp increase in unemployment in all regions, except Kharkiv. In 2013, as in the past, regions specialised in agriculture (largely in Western and Central Ukraine) exhibited higher unemployment rates (Figure 1.20). Two years of recession and the Donbas conflict somewhat altered this pattern: in 2016, the two Donbas regions (Donetsk and Luhansk) had the highest unemployment rates in Ukraine, 16% in Luhansk. Poltava and Zaporizhia, with strong manufacturing and mining sub-sectors, also recorded relatively high unemployment rates (12.6% and 10%, respectively). Employment in regions surrounding large urban centres was usually lower, particularly Kyiv, Kharkiv (the lowest unemployment rate in Ukraine) and Odessa (Figure 1.20).

In all but one of Ukraine’s 25 regions, labour force participation rates have decreased since 2013.15 The higher the unemployment rate in a given region, the sharper the drop in labour market participation.16 This suggests that the drop in labour market participation is mostly due to discouraged workers, who could join the labour force again if it became easier to find a job. The decrease in labour market participation has been particularly strong in Donetsk oblast and in some agricultural oblasts of Western Ukraine (Volyn, Khmelnytskiy and Ternopyl), where labour force participation fell below 60% (corresponding to the 15% of TL2 regions in the OECD with the lowest labour market participation rates). In some oblasts (Odesa, Donetsk), female participation rates fell as low as 52% (this is lower than all OECD countries except for Turkey). Therefore, increasing the female labour market participation in these regions could help mitigate the effect of a declining labour force over the next few years.

Figure 1.21. Impact of the 2014-15 recession on regional unemployment, Ukraine

The Donbas conflict contributed to increasing spatial fragmentation of Ukraine’s labour market: the dispersion index of regional unemployment rates, which went down after 2009 because unemployment increased particularly in low-unemployment regions, reached 24% in 2016, the highest level since 2005 (Figure 1.21). This would place Ukraine in the upper quartile among OECD countries as regards the dispersion index of unemployment rates.17 Annex 1.C provides an analysis of regional labour markets based on vacancy statistics from the State Employment Service. While further research and more reliable data are needed, analysis of the limited available data provides further evidence of spatial fragmentation and of inefficiency in some regional labour markets. For instance, a few oblasts – such as Zhytomyr, Ternopyl and Poltava – have a higher unemployment rate than the national average while their vacancy rate (an indicator of firms’ labour demand) is also above the national level (Figure 1.C.1 in Annex 1.C). This could be due to mismatches between workers’ skills/qualifications and labour market needs.

Figure 1.22. Regional dispersion of unemployment rates, Ukraine

* Holding the 2013 unemployment rate and population share constants in 2014-15-16 for Luhansk and Donetsk.

Notes: The dispersion index is measured as the sum of absolute differences between regional and national values, weighted with regional share of population and expressed in per cent of the national value.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine (2017a), “Labour Force Survey”, www.ukrstat.gov.ua.

There is also evidence that the matching between labour demand and labour supply degraded during 2013-16: contrary to what one would expect, while unemployment rates increased in all regions, vacancy rates also increased in 12 regions out of 25. Moreover, there is a positive correlation between the increase in unemployment and the rise of vacancy rates (Figure 1.22). Three regions (Volyn, Kirovograd and Luhansk) entirely determine this correlation, because they experienced both a substantial increase in unemployment and in their vacancy rate, suggesting an increasingly poor matching between firms and workers. In the case of Luhansk this could be due to the relocation of many qualified workers to other regions of Ukraine in the context of the armed conflict.

Figure 1.23. Change in unemployment and vacancy rates by region, Ukraine, 2013-16

* Data for government-controlled territory.

Source: State Statistics Service of Ukraine, State employment Service of Ukraine, Labour market indicators, www.ukrstat.gov.ua.