The Assessment and recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Hungary and identify 36 recommendations to help Hungary make further progress towards its environmental policy objectives and international commitments. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance reviewed and approved the Assessment and recommendations at its meeting on 13 February 2018. Actions taken to implement selected recommendations from the 2008 Environmental Performance Review are summarised in the Annex.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Hungary 2018

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1.1. Environmental performance: Trends and recent developments

After Hungary joined the European Union (EU) in 2004, its economy grew at a faster pace than the OECD average until it was hit by the global downturn. Growth picked up in 2012 and reached its pre-crisis level in 2014. It is expected to continue at a rate above 3.5% in 2017-18. However, convergence of income levels towards the OECD average has stalled since the crisis, reflecting weak productivity growth and low levels of investment (OECD, 2017a). The poverty rate and overall inequality are below the OECD average. They had been rising until 2013 but have started to decrease in recent years. There are wide regional disparities in income levels, employment and access to basic services.

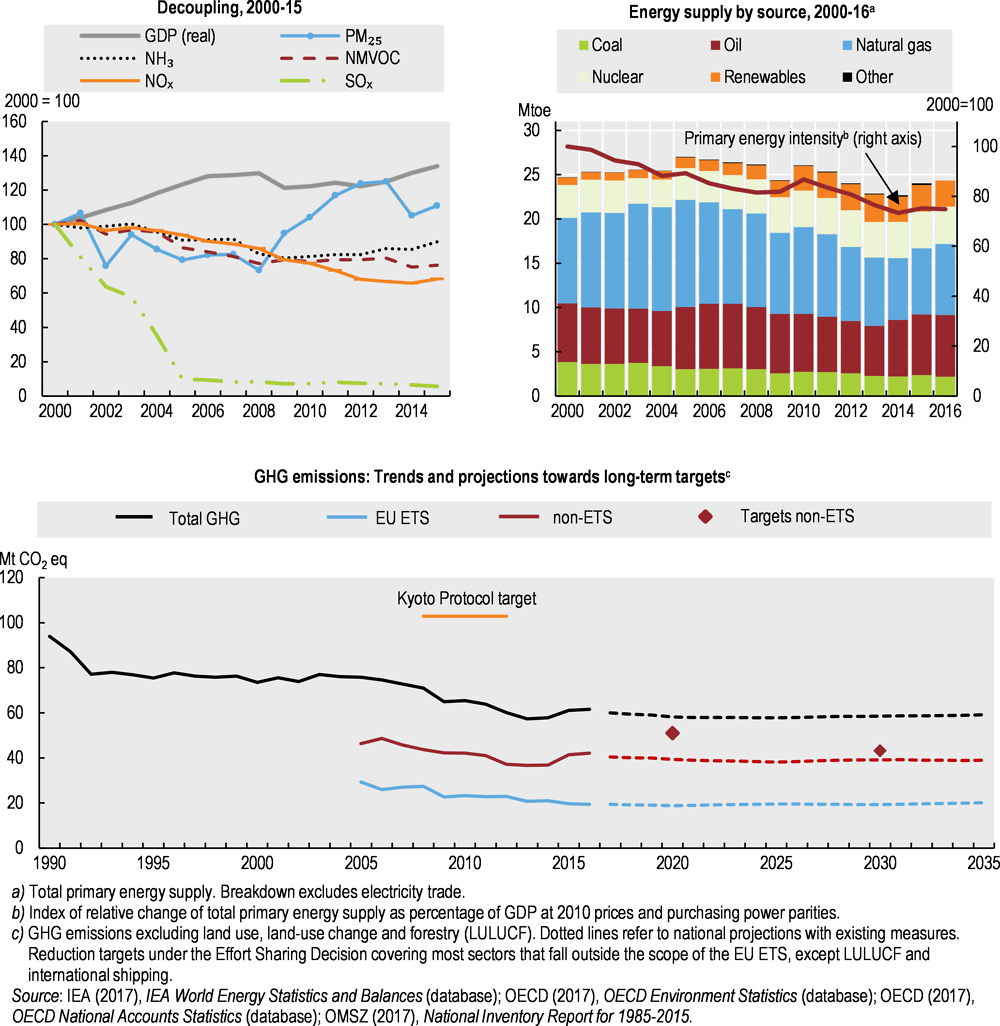

The country has made significant progress in decoupling its output growth from main environmental pressures (Figure 1), largely due to implementing requirements of EU directives. However, the recent rebound of economic activity is intensifying pressures on the natural environment. Energy consumption and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have started to pick up. Local air quality has not improved significantly, making Hungary’s mortality rates due to air pollution exposure among the highest in the OECD. Despite the growing wastewater treatment coverage of the population, water quality remains at risk from pollution from agriculture and wastewater discharges. Shrinking water flows caused by prolonged droughts aggravate the problem. Most Hungarians are concerned about climate change, air and water pollution, and growing waste generation, recognising them as serious issues (EC, 2015, 2014).

Figure 1. Selected environmental performance indicators

1.1.1. Transition to an energy-efficient and low-carbon economy

Hungary has gradually reduced its reliance on coal and natural gas in favour of low-carbon energy sources. Over 2000-16, the use of coal dropped by 43%, while the use of natural gas fell by 17%. However, fossil fuels still make up about 70% of the energy supply, and the share of oil has started to pick up again (Figure 1). The share of nuclear energy in the total primary energy supply (TPES) has increased since 2000, albeit not as much as its share in power generation, which grew by 25%.

The National Energy Strategy 2030 and the National Renewable Energy Action Plan 2010-2020 aim at reducing Hungary’s energy dependence. Specifically, they seek to boost the share of renewable energy sources in gross final energy consumption to 14.7% by 2020 (beyond the EU target of 13%). This share already stood at 14.5% in 2015 (Eurostat, 2017), a threefold increase since 2000, and is likely to exceed the national 2020 target. The increase of renewable energy supply is, however, likely to slow down due to its heavy reliance on biomass (93% in 2016). Further stimulus should focus on developing other renewable sources such as solar, wind or geothermal energy (IEA, 2017).

The National Energy Strategy 2030 also aims at reducing Hungary’s energy dependence by increasing energy efficiency economy-wide. Since 2000, primary energy intensity has declined by 25% and is now on par with the OECD average. It remains significant, primarily due to the energy-intensive chemical and steel industries, and poor energy efficiency in buildings. Recent measures have led to an improvement of space heating efficiency in the residential sector. However, this sector remains the biggest energy consumer, with 80% of the building stock lacking modern and efficient heating systems. Energy consumption in the transport sector has grown the fastest since 2000 and is expected to continue to increase along with a rapid expansion of the private motor vehicle ownership, which is currently one of the lowest in the OECD. The Transport Energy Efficiency Improvement Action Plan (TEEIAP) and the E-mobility Programme (the Jedlik Ányos Plan) envisage a wide array of measures to enhance the use of electric vehicles (EVs), including tax incentives and subsidies for the purchase of such vehicles (Section 1.3).

Total gross GHG emissions have decreased by 35% since 1990 (Figure 1). About 80% of this reduction came from the power sector due to the change in the fuel mix. Other factors included the restructuring of the chemical industry and modernisation of the building stock. Yet emissions have recently started to increase: in 2015, they grew by almost 6% over the previous year, driven by transport and, to a lesser extent, agriculture. According to government projections, the country is on track to reach its 2020 and 2030 targets for sectors outside the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) with existing measures. However, further progress in energy savings, development of renewable energy resources and transport are needed in the context of economic recovery and the recent increase in GHG emissions.

Hungary was the first EU member state to ratify the Paris Agreement. The first National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS) for 2008-25 aims at further reducing GHG emissions through improved energy efficiency in buildings, the use of renewable energy sources, increased environmental sustainability of transport and afforestation. The second NCCS to 2030, with an outlook to 2050, awaiting parliamentary approval, will include a National Decarbonisation Roadmap and a National Adaptation Strategy. These will be supported by a Climate Change Action Plan to monitor implementation. However, the second NCCS does not manifest climate policy ambition beyond EU requirements or set national emission reduction targets.

Hungary is vulnerable to flooding caused by extreme climate events, with a quarter of the territory and 18% of the population exposed to flood risks. Since 2008, the country has taken measures to address flood risks. It adopted a national Flood Risk Management Plan, completed the High Water Riverbed Management Plan and constructed emergency storage reservoirs. Hungary also needs to strengthen measures to address droughts, which affect both the quality and quantity of groundwater resources.

Hungary has reduced emissions of sulphur and nitrogen oxides, ammonia and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOC) significantly since 2000, decoupling them from economic growth (Figure 1). Major drivers of the emission decline have been the shift from coal to natural gas in power generation, technological improvement in heating systems of the residential sector fleet and the reduction in livestock. Hungary has met its 2010 targets under the EU National Emission Ceilings Directive for these pollutants. However, additional efforts will be required to meet the 2020 objectives, particularly for ammonia emissions from agriculture and NMVOC emissions from industry.

Emissions of particulate matter have been increasing significantly since 2000, worsening air quality in Budapest and several towns in northern Hungary. The average exposure of Hungarian citizens to PM2.5 is more than double the annual guideline limit set by the World Health Organization (WHO) (EEA, 2016). The cost of premature death in Hungary due to exposure to PM2.5 and ozone attained an estimated 9% of gross domestic product (GDP), the second highest value in the OECD (Roy and Braathen, 2017). In 2011, the government launched an Action Programme to reduce PM10. The programme focuses on transport and residential heating, which rely heavily on burning lignite and wood. However, the government needs to do more to address emissions of PM2.5 and meet the respective EU targets for 2020 and 2030.

1.1.2. Transition to efficient resource management

Hungary is relatively poorly endowed with raw materials and relies heavily on energy and material imports. Its economy is less resource-intensive than that of other OECD member countries: domestic material consumption (DMC) per capita is significantly below the OECD average, but close to the average for OECD Europe countries. Total DMC decreased by 20% between 2008 and 2016. In terms of material productivity (GDP per unit of DMC), Hungary is below the OECD Europe average. This indicates that the country could use material resources more efficiently to produce wealth.

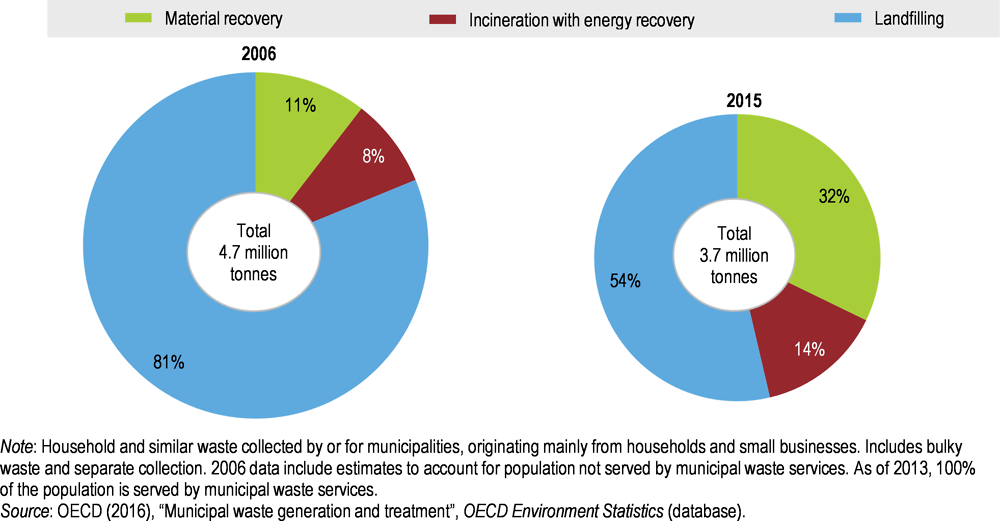

From 2008 to 2015, total waste generation decreased by 17% while GDP increased by 3%, which is a significant achievement. Hungary has also achieved decoupling between economic growth and municipal waste generation. Material recovery is on the rise for construction and demolition waste and municipal waste. Landfilling is declining, but still accounts for 54% of municipal waste generation (Section 1.4).

Agriculture uses about 60% of the total land area, with important environmental implications. The consumption of nitrogen fertilisers increased between 2000/02 and 2012/14 by 25%, while crop production grew by about 40%. However, the intensity of nitrogen fertiliser use per hectare of agricultural land increased by almost 40%, much faster than in other European countries of the OECD. Sales of pesticides have also increased (by 11% over 2011-15). The share of organic farming in the total farming area increased from 2.4% in 2010 to 3.5% in 2016 (HCSO, 2017). Still, this rate is small compared to other OECD member countries (Section 1.5).

1.1.3. Management of natural assets

Hungary ranks high among OECD member countries in water abstraction per capita. The government recently changed its water pricing policy to reduce consumption and take into account the economic value of the resource. In January 2017, water abstraction charges were extended to all uses, including agriculture.

The share of the population connected to wastewater treatment reached 78% in 2016 thanks to massive EU-funded investment in new treatment facilities and sewerage networks. However, this share remains one of the lowest in the OECD and is uneven across the country. Although better access to wastewater treatment has helped improve water quality, a large proportion of rivers (88%) have a bad to moderate ecological status. Nitrate pollution from fertilisers and resulting eutrophication remain of concern, and nitrate-vulnerable zones cover about 70% of the national territory. In addition, according to national estimates, 38% of the population receives drinking water of unsatisfactory quality.

The National Water Strategy, the pillar of Hungary’s water, irrigation and drought management policy, was revised in 2017. It aims at integrating agriculture and nature conservation issues into water resources management, as well as developing climate change adaptation measures. The Fourth National Environmental Programme (NEP) for 2015‑20 includes objectives for conservation of water resources and prevention of water pollution.

Over the last decade, Hungary has made several improvements in the area of biodiversity. It was one of the first EU member states to have its Natura 2000 network of protected areas declared complete in 2011. However, most habitats remain in an unfavourable state. Further effort is needed to reduce pressures on biodiversity from land-use change, habitat fragmentation, pollution, invasive species and climate change (Section 1.5).

Recommendations on climate change, air pollution and water management

Climate change

Strengthen efforts to co‑ordinate the implementation, including monitoring and reporting, of energy- and climate-related strategies and action plans; develop ambitious targets for reducing domestic GHG emissions and analyse the economic, environmental and social impacts of different scenarios to achieve them.

Integrate adaptation concerns into the National Climate Change Strategy and infrastructure investment plans; address the risk of increased flooding and resulting vulnerability of the water supply and sanitation systems through improved engineering and water management practices.

Air quality

Significantly reduce particulate emissions from solid fuel combustion in residential heating and mitigate related adverse health impacts by introducing more efficient and less polluting heating and cooling systems and better insulation of buildings.

Water

Reinforce measures to reduce the abstraction of freshwater through enhanced water use efficiency in irrigation and other agricultural practices.

Reduce diffuse water pollution from agriculture by promoting sustainable use of fertilisers; complement EU funds with increased national public and private investment to upgrade wastewater treatment; increase the share of population connected to the sanitation infrastructure and improve access to drinking water fully compliant with EU requirements.

1.2. Environmental governance and management

Since the 2008 Environmental Performance Review, Hungary has not demonstrated substantial progress in environmental governance. A broad administrative simplification reform since 2010 has consolidated central and territorial government bodies. This process has had a considerable impact on the institutional capacity in the environmental domain. Although the regulatory framework has been strengthened, serious institutional challenges impede more effective implementation of environmental law and uptake of good practices. Certain regress has occurred regarding environmental democracy.

1.2.1. Institutional framework

Hungary has a centralised system of environmental governance, where most powers are exercised by the national government and its territorial institutions. Hungary is one of the few EU member states without a dedicated environment ministry. The environment-related responsibilities are fragmented across several large ministries. The Ministries of Agriculture, National Development and Interior play key roles in the water domain. A major overhaul of the government’s territorial institutions has, among other measures, abolished the national and county (regional) environmental inspectorates and divided permitting and compliance assurance functions between consolidated county and district government offices and, in the water domain, disaster management authorities.

Dismantling of the environment ministry and associated inspectorates coupled with other frequent changes in the institutional framework have led to fragmentation of environmental responsibilities at the national level, policy uncertainty and loss of human resource capacity. Horizontal co-operation between institutions of national and territorial governments, facilitated by the creation of consolidated county and district government offices, has improved in line with a recommendation of the 2008 Environmental Performance Review. However, this happened primarily to compensate for the break-up of the former environment ministry’s functions.

1.2.2. Regulatory framework

Hungary has firm constitutional guarantees in the environmental domain. The strengthening of its environmental laws and regulations has been heavily influenced by the transposition of EU directives. Regulatory and policy evaluation tools, including regulatory impact assessment and strategic environmental assessment (SEA), have been used more extensively over the last decade.

The environmental permitting system complies with the EU Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control Directive for high-risk industrial installations. However, there is no coherent regime for regulating lower-impact facilities across environmental media. National, regional, county and local spatial plans consider environmental impact, but SEA in land-use planning is only applied in larger cities or in connection with applications for EU funding.

1.2.3. Compliance assurance

Recent institutional changes have made compliance monitoring and enforcement more complex. District government offices often have insufficient human and technical resources to do the job adequately. The number of inspections has been declining in recent years, which has led to lower rates of detection of non-compliance. The relative risk level (including compliance record) of individual installations is not explicitly considered in inspection planning. Competent authorities do not follow good enforcement practices such as multifactor guidance for application of sanctions. There are no adequate data collection arrangements to track the use and effectiveness of different compliance assurance interventions, including administrative fines.

At the same time, Hungary actively implements its system of strict (i.e. independent of fault) liability for damage to the environment. It has made progress in the remediation of old contaminated sites using budgetary and EU funding. It has also introduced a system of mandatory financial security, but this is currently limited to hazardous waste management. The environmental insurance market is underdeveloped (EC, 2017a).

Environmental authorities do not engage in compliance promotion activities. Although the 2015 National Action Plan on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) emphasises environmental performance, there are no voluntary agreements with individual economic sectors on achieving environmental targets. Several CSR initiatives emanate from the business community, but the government does not recognise or reward them. The potential of green public procurement and environmental management systems certifications to promote green business practices and generate economic opportunities is not fully exploited. For now, there is little domestic market demand for good environmental performance.

1.2.4. Environmental democracy

The government has improved management of environmental information by establishing a data collection and processing network. However, it does not do enough to disseminate it to the public. There are restrictions and fees (since 2011) for accessing environmental information held by public bodies and state-owned enterprises. In addition, civil society has expressed concerns that privately-held environmental information is excessively protected on the grounds of commercial confidentiality. Environmental education is part of the National Core Curriculum. However, Hungary has not fully implemented the 2008 Environmental Performance Review recommendation to ensure environmental training of public servants and justice officials. Despite several targeted campaigns, the public’s low environmental awareness remains a challenge.

Hungary has made little progress in implementing the 2008 recommendation to further promote citizen participation in environmental decision making and access to justice on environmental issues. The Deputy Commissioner for Fundamental Rights, Ombudsman for Future Generations – whose role is highly appreciated by civil society groups – has repeatedly raised concerns about environmental democracy in his reports. Public consultations are insufficient on draft environmental legislation. Public participation in environmental impact assessment (EIA) of large government-sponsored infrastructure and industrial projects is also weak (EC, 2017a). Access to justice is complicated by restrictions on legal standing of individuals and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that limit possibilities to take government agencies to court on environmental matters. The high cost of administrative and judicial appeals also undermines access to justice.

Recommendations on environmental governance and management

Institutional and regulatory framework

Raise the political profile of the environment by renaming the Ministry of Agriculture as the Ministry of Agriculture and Environment; reduce the fragmentation of policy and regulatory responsibilities in the water domain by consolidating them within that ministry; continue to integrate environmental aspects into other ministries’ mandates and enhance horizontal co‑ordination at the national level; merge all environmental compliance assurance functions at the territorial level within respective government offices.

Build capacity of government staff, particularly at the local level, on best practices in implementation of environmental law; enhance the technical resources in support of their functions.

Streamline and simplify the environmental permitting regime for installations not subject to integrated pollution prevention and control permits; consider introducing sector-specific, cross-media regulations for facilities with low environmental impact.

Strengthen the implementation of SEA by applying it systematically to all spatial plans and territorial development concepts, as well as to all government policies and programmes with a potential environmental impact.

Compliance assurance

Introduce risk-based planning and targeting of environmental inspections; enhance the use of economic sector-specific guidance, certifications and recognition awards to promote compliance and green business practices.

Evaluate the deterrent effect of administrative fines and consider reforming them to account for the economic benefit of non-compliance; develop enforcement policies and guidance for inspectors on proportionate application of sanctions; expand use of financial security instruments such as insurance, security deposits and letters of credit to help enforce liability for damage to the environment.

Environmental democracy

Enhance opportunities for meaningful public participation as part of environmental rule-making and EIA; restore government funding for environmental NGOs; remove restrictions for individuals and NGOs to access justice on environmental matters and ensure that it is free of charge.

Make environmental information, including facility inspection records, more accessible to the public online; remove all restrictions and fees for public access to environmental information held by public bodies and review confidentiality-related restrictions of access to enterprise data.

Strengthen vocational environmental training for public officials; step up environmental awareness-raising campaigns on energy- and climate-related issues, as well as biodiversity protection, and increase budgets for them.

1.3. Towards green growth

Hungary has significant opportunities for accelerating the transition towards a low-carbon, greener and more inclusive economy, especially by investing in residential energy efficiency, renewables, and sound waste and material management (EC, 2017a). To seize these opportunities, it should make better use of economic instruments and scale back state aid to environmentally harmful sectors. At the same time, it could improve efficiency in using the EU structural and investment funds to extend access to basic services, better leverage investment in the business sector, invest in research and development (R&D) and education, and better target social programmes.

1.3.1. Framework for sustainable development and green growth

The government approved the second National Framework Strategy on Sustainable Development (NFSSD) for 2012-24. The government’s 2017 second biennial review of the NFSSD recommended that it be harmonised with the Sustainable Development Goals. Hungary has also developed a wide set of sectoral and cross-sectoral strategies, such as the National Environmental Technology Innovation Strategy (NETIS) 2011-20. In 2012, the government approved a decree requiring harmonisation of strategic planning documents and monitoring of their implementation. However, it is not always clear how it ensures coherence across policies to guide action towards a low-carbon, resource-efficient and greener economy.

1.3.2. Greening taxes and subsidies

Hungary has long applied a wide range of environmentally related taxes and charges and has further extended their use. In addition to energy and vehicle taxes, which are commonly applied in OECD member countries, Hungary imposes levies on air emissions, water abstraction, water/soil pollution, waste disposed of in landfills and several environmentally harmful products. The revenue from environmental taxes is relatively high in international comparison, although it has grown at a lower rate than GDP and total tax revenue since the mid-2000s. It accounts for about 7% of total tax revenue and almost 3% of GDP. However, these taxes mainly raise revenue; there is no evidence that they have delivered tangible environmental outcomes. Their design needs to be improved, and their rates should be better aligned with environmental costs and regularly increased to provide stronger incentives for sustainable consumption, resource efficiency and pollution abatement, as well as to maintain revenue. Given high spending needs for investment, education and health (among others), and the government’s focus on reducing taxes on labour and businesses (OECD, 2016a), additional and less distortive revenue sources such as environmentally related taxes may be appropriate.

The government recently raised tax rates on energy products, but the carbon price signal remains weak. To stabilise revenue from consumption taxes, the standard tax rates on petrol and diesel temporarily increase when the world oil market price is below USD 50/barrel. Tax rates on energy products do not fully reflect the estimated environmental costs of carbon emissions: tax rates on transport fuels are relatively low; rates on other fuels are set at or only slightly above the EU minimum rates; and fuel use in some sectors is fully tax exempt. Tax rates are not systematically adjusted for inflation. All this puts Hungary among the ten OECD member countries with the lowest effective tax rate on energy on an economy-wide basis (OECD, 2015).

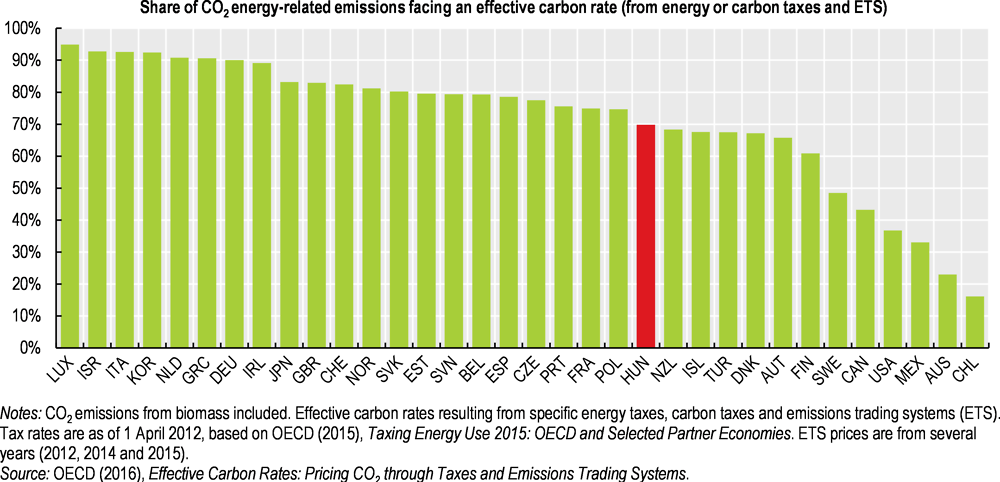

In addition to putting a price on carbon via energy taxes, Hungary participates in the EU ETS. However, as in many other countries, the effects of the EU ETS on low-carbon investment in Hungary’s energy and manufacturing sectors have been limited. This is due to a systematic surplus of emission allowances, free allocations to the manufacturing sector and low carbon prices in the market. When accounting for both energy taxes and the CO2 emission allowance price emerging in the EU ETS, about 70% of CO2 emissions from energy use face a carbon price signal in Hungary (OECD, 2016b). This share is below that observed in many other OECD member countries (Figure 2). In all sectors other than transport, CO2 emissions are either priced below EUR 30 per tonne of CO2 (a conservative estimate of the climate costs from 1 tonne of CO2 emissions) or not at all.

Figure 2. A relatively low share of carbon emissions faces a price signal

The structure of vehicle taxes does not fully take into account the environmental performance of vehicles, discourages the renewal of the vehicle fleet and encourages acquisition of second-hand cars. Partly due to these contradictory price signals, the car fleet in Hungary is outdated and more carbon-intensive than the EU average. Removing the tax depreciation for old vehicles and linking vehicle taxes to emission standards would encourage the switch to cleaner cars, including EVs. A company car tax based on emission levels of the vehicle applies at the company level. This provides an incentive to businesses to choose less-emitting vehicles for their company car fleets. However, Hungary is among the few OECD countries that do not tax benefits arising from the personal use of company cars. This tends to encourage private car use and long-distance commuting, potentially leading to higher emissions of GHGs and local air pollutants, noise and congestion (Harding, 2014).

As in many other EU countries, road tolls do not fully reflect the environmental and social costs of infrastructure use. Hungary has put in place a distance-based electronic road toll system for heavy goods vehicles, with tolls based on vehicles’ emission standard, and a time-based electronic toll system for passenger and small commercial vehicles (so-called e-Vignette). However, Hungary is the only EU country among those implementing the e-Vignette system that does not differentiate tolls by vehicles’ Euro emission class.

Hungary is among the few EU member states that have introduced or increased taxes on pollution and resources in recent years. These taxes account for about 10% of environmentally related tax revenue, well above most other OECD member countries. Some of these, such as the water-related taxes, have a sophisticated design. However, the effectiveness of pollution and resource taxes has generally been limited. Rates are relatively low and not systematically adjusted, and the exemptions and rebates may hinder their effectiveness.

Hungary supports fossil fuel consumption in several ways. These include support for electricity production from coal, for fuel used in agriculture and for residential use of heat (OECD, 2016c). In addition, since 2013 the government has cut prices of natural gas, heating and electricity for households at levels below costs, while raising those for industrial users. This reduces the incentive to invest in the energy sector, including in renewables (IEA, 2017). It undermines the government’s efforts to improve energy efficiency in buildings, and contravenes the recommendations of Hungary’s own National Energy Strategy to 2030.

Energy price cuts and subsidies for residential use of heat aim to address increasing risks for energy affordability. While these risks are common to other Central and Eastern European countries, they seem to be more acute in Hungary, where over a fifth of households spend more than 10% of their income on energy and fall under the poverty line after paying their energy bills (Flues and van Dender, 2017). However, below-cost energy prices and subsidies for energy use are not an effective way of increasing energy affordability. They risk locking households into fuel poverty, as artificially low prices do not encourage efficient energy use. Moreover, these types of support for energy bills do not target the people most in need. Government-imposed price controls benefit all users, including well-off households. Meanwhile, subsidies for heat consumption mostly benefit people in urban areas, where the natural gas and district heating networks are developed (Tirado Herrero and Ürge-Vorsatz, 2012). These subsidies could be removed, and the resulting budget savings used for cash transfers to poor households.

1.3.3. Investing in the environment to promote green growth

Hungary has significantly benefited from EU structural and regional funds to finance public investment. Over 2007-20, EU funds allocated to Hungary represented 3% of GDP a year, on average. These funds have contributed to considerably increasing public environment-related expenditure since the mid-2000s, including in wastewater, waste and transport infrastructure. However, business environmental investment has declined. This indicates that price signals and financial incentives have not been effective in stimulating private investment to improve energy and resource efficiency in production processes. More generally, a high administrative burden alongside frequent and unpredictable regulatory changes reduce the country’s attractiveness to potential investors (EC, 2017b). A wide range of financial support schemes is available to encourage environment-related investment. However, there is high dependence on EU funds for financing both public and business environment-related investment. There is a risk that national and EU funds are not used cost-effectively to finance investment that would occur even without public support.

Investment needs remain high despite increased investment and tangible progress in expanding environment-related infrastructure such as wastewater treatment. The quality of infrastructure varies by region and is perceived to be low relative to local expectations. User fees for water supply, wastewater discharges and waste management have been either frozen or cut in recent years; in most cases, user fees only partly cover the costs of these services. As a result, many water utilities have been struggling to ensure adequate maintenance of the ageing water infrastructure (World Bank, 2015).

Hungary has promoted renewable energy through various forms of financial assistance for capital investment and feed-in tariffs. The new renewable energy support scheme (METÁR), which partly replaced the feed-in tariff system in 2017, is significant progress. However, the development of renewables faces non-financial barriers such as strict technical requirements for wind energy. The electricity network needs to better integrate increasing renewable generation (IEA, 2017).

There is still significant potential for improving buildings’ energy performance. Incentives for energy efficiency in buildings should be better aligned: although the government provides financial support for energy efficiency investment, below-cost end-use prices of energy lead to lower returns on investment in renewables and energy efficiency (IEA, 2017). Recent actions have helped reduce space heating needs and the energy intensity of the residential sector. These include the Warmth of Home programme, local tax incentives, awareness-raising and energy certification of buildings. Additional measures are needed to address non-pricing barriers to adopting energy-efficient technology in industry, transport and buildings.

Most transport investment has been in the road network. While this is needed to meet increasing transport demand, Hungary should ensure investment priorities for transport infrastructure are consistent with long-term climate and environmental objectives. Hungary’s TEEIAP foresees investment in, among others, railway electrification and network modernisation, public transport services, bus replacement and bicycle lanes. The 2015 E-mobility Programme (the Jedlik Ányos Plan) aims to extend use of EVs nearly tenfold by 2020. The programme lays out a wide range of measures, including generous subsidies to purchase EVs that tend to support mostly well-off people. Overall, investment needs and financing sources for fully implementing the E‑mobility Programme, as well as the programme’s impact on electricity generation and cost-effectiveness, are not clear.

1.3.4. Promoting eco-innovation

Hungary has made considerable efforts to improve its innovation system, but R&D investment remains low and the skill base is often inadequate (OECD, 2016a). Focus on eco-innovation has increased, including by targeting environmental technology in strategic documents such as the NETIS. However, eco-innovation performance lags behind. As for other research fields, the government is the main source of funding for environmental research. However, the share of government R&D outlays dedicated to environment-related R&D declined by about 25% between 2008 and 2014/15. On the other hand, research in renewables and energy efficiency attracts nearly the entire small, public energy-related R&D budget. Overall, Hungary spends nearly 5% of its government R&D budget on environment- and energy-related research, lower than the OECD average. Patent applications related to environmental management and climate-change mitigation technologies made up about 7% of all patent applications in 2012-14. This is among the lowest shares in the OECD and below the shares observed in the other countries of the Visegrád Four (Czech Republic, Poland and Slovak Republic).

Similarly, the environmental goods and service sector has grown in Hungary, but seems to be less developed than in most EU countries. A lower percentage of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) produce greener products and services in Hungary than on average in the European Union (EC, 2017a). The government plans to make the green industry more competitive and enlarge environmental markets as part of the 2016 Innovative Industry Development Directions (so-called Irinyi Plan).

Co‑ordination among environmental, innovation and education policies remains challenging. The economic efficiency of the environment-related innovation policy and its contribution to improving environmental performance, resource productivity and energy efficiency are not systematically evaluated. As in most OECD member countries, the policy mix for innovation and eco-innovation is biased towards supply-side measures such as R&D funding. More efforts are needed on the demand side, such as green public procurement, aligning market incentives with environmental objectives and enforcement of environmental legislation. This would help make the green industry more competitive, stimulate innovative investment and enlarge environmental markets.

1.3.5. Contributing to the global environmental agenda

Hungary has a long tradition of international, regional and bilateral co‑operation in the environment field, especially to address transboundary issues related to the Danube River Basin. Hungary has an excellent record in signing and ratifying the international environmental agreements to which the European Union is party (EC, 2017a). In line with the OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits, Hungarian authorities have developed screening and monitoring procedures to assess the environmental, social and human rights impact of the export projects that are publicly financed.

In December 2016, Hungary joined the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). The volume of its official development assistance (ODA) has almost doubled since Hungary’s accession to the European Union. At 0.13% of the country’s gross national income (GNI) in 2016, ODA is in line with the efforts of the other Visegrád Four countries. However, it is considerably below the target of 0.33% of GNI by 2030 common to all member states that have joined the European Union since 2002 (OECD, 2017b). Environmental protection and climate change are among the priority areas of Hungary’s development co‑operation. While modest, ODA flows devoted to address global environmental issues have increased. They focus on adaptation to climate change, mainly on water management infrastructure and flood management. With its good economic and fiscal performance, Hungary has an opportunity to increase its ODA volume, particularly bilateral ODA targeting the environment, in line with international goals and its new DAC membership. It must also ensure systematic evaluation of the environmental and social impact of development co‑operation projects.

Recommendations on green growth

Strategic framework

Ensure alignment of the National Framework Strategy on Sustainable Development with sectoral strategies; develop a framework for monitoring their implementation and progress towards green growth objectives, based on a targeted set of indicators linking economic activity and social welfare with environmental performance.

Price signals

Improve the design of environmentally related taxes to reinforce their incentive function: i) take advantage of the low world oil price to permanently raise the tax rates on petrol and diesel to levels that reflect the environmental costs of driving; ii) consider introducing a carbon tax on sectors outside the EU ETS; iii) link vehicle taxes to fuel economy and air emission standards and progressively untie them from the age of vehicles; iv) gradually raise the rates of pollution and resource taxes to align them with the environmental costs of pollution and resource use; v) regularly adjust tax rates for inflation.

Remove incentives to private car use and long-distance commuting; reform the tax treatment of the personal use of company cars and parking spaces; link road tolls for passenger vehicles to the vehicles’ emission standards; consider introducing congestion charges in major cities.

Establish a process for systematic review of environmentally harmful subsidies and regularly evaluate proposals for new subsidies and subsidy removals against their potential environmental, social and economic impacts.

Re-introduce market-based energy prices and gradually phase out the heat subsidy, while compensating vulnerable groups through social benefits that are not linked to energy consumption.

Green investment and innovation

Increase, better prioritise and enhance the transparency and cost-effectiveness of national public spending on environment-related infrastructure while reducing reliance on EU funds; leverage private funding and revise tariffs for energy and water to ensure better cost recovery.

Align transport infrastructure investment with long-term environmental objectives; identify investment needs and financing sources for implementing the E-mobility Programme; analyse its impact on electricity generation; compare its cost-effectiveness with other options to reduce GHG emissions from transport.

Strengthen energy efficiency standards for new buildings; set rules for dividing the costs and benefits of energy efficiency improvements between tenants and landlords; scale up investment in raising energy efficiency of public buildings; develop energy networks to connect additional renewable generation capacity.

Reduce transaction and administrative costs to facilitate investment decisions in green technology; increase public R&D funding for environment-related innovation and evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of its allocation; swiftly adopt and implement a national action plan for green public procurement.

1.4. Waste, material management and circular economy

Since the 2008 Environmental Performance Review, Hungary has experienced positive trends for waste and material management. However, its overall performance remains average. The instability of the governance structure and its recent re-centralisation could be counterproductive in fostering further improvements and investments in a circular economy.

Hungary has achieved decoupling of waste generation from GDP, especially for municipal waste. In another achievement, the rate of recycling and recovery has increased since 2006, although it remains low compared to neighbouring EU countries. Landfills not complying with EU standards were closed by 2009. However, most waste (54%) still ends up in landfills (Figure 3). Hazardous waste generation is on the decline despite substantial yearly variations. DMC is low and decreased substantially between 2008 and 2012, mainly due to the economic crisis. However, DMC is now growing quickly in line with the economic recovery.

Figure 3. Municipal waste generation and the share of landfilling have decreased

1.4.1. Policy, legal and institutional framework

Hungary’s waste management policies are mainly driven by EU objectives and targets. The legal framework for waste management was updated in 2012: the Act on Waste transposes the EU Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), while the Environmental Product Fee Act targets a wide range of environmentally harmful products.

Since 2008, Hungary has centralised and nationalised the waste management system. The central government has progressively taken over the responsibilities of municipalities for establishing waste tariffs and paying public waste service providers. This move risks limiting municipalities’ flexibility to tailor waste management services to their needs, possibly slowing down improvements in waste performance.

This major reform coincided with an important reorganisation of the institutional framework at the national level. Administrative responsibilities for waste management have been reallocated on several occasions, and the National Waste Agency has been dismantled. The Ministry of Agriculture is now the leading ministry for waste management and circular economy policies, while the Ministry of National Development oversees municipal waste services. A new central state entity, the National Organiser of Waste and Asset Management Plc., was established in 2016.

The new centralised waste management system was meant to improve implementation of national waste management policies at the local level. However, national objectives and targets are not always well incorporated into local priorities. The elimination of local waste management plans could make it more difficult to address the specific challenges of local territories. Indeed, there are wide discrepancies in performance across counties and municipalities, particularly regarding separate collection of municipal waste.

Regarding the information system for waste and material management, waste and material flows data are collected in line with EUROSTAT requirements. Hungary monitors some resource-efficiency achievements as part of the NETIS. However, waste and material flows data are not well integrated.

1.4.2. Environmentally sound management of waste, recovery and recycling

Hungary has met its objective to increase diversion of biodegradable municipal waste from landfills. It is on track to recycle half of municipal paper, plastic, metal and glass by 2020. Door-to-door collection systems for municipal paper, plastic and metal waste have been mandatory for municipalities since 2015. This is likely to improve separate collection, which is quite low in many areas of the country. The illegal burning of household waste for heating remains an important issue despite ongoing awareness campaigns.

Regarding hazardous waste, Hungary strengthened control of its transboundary movements by increasing inspections and creating a 24-hour service to detect illegal international shipments. Nevertheless, Hungary experienced several accidents related to questionable hazardous waste management practices during the review period.

The share of landfilling of construction and demolition waste has significantly decreased (by 53% since 2009), while material recovery has increased. Hungary is on track to meet its objective of 70% of material recovery by 2020 for this waste stream. It is now emphasising waste prevention in construction, particularly through selective demolition to remove recyclable and reusable parts of waste.

1.4.3. Economic instruments for waste management

Hungary further expanded use of economic instruments with the introduction of a landfill tax in 2013. The tax successfully diverted construction and demolition waste from landfills, where it has encouraged recovery in backfilling operations. However, the landfill tax rates were frozen at 2014 levels. As landfilling costs remain low, the market signal to divert waste from landfills is insufficient.

Waste management tariffs for households, set at the national level, were first frozen in 2012 and then reduced in 2013 for social reasons. This has raised questions of long-term financing of municipal waste management and capacity of waste businesses to recover their costs when they contribute to public service operations (EC, 2017a).

A state-controlled extended producer responsibility system based on product fees recently replaced producer-funded producer responsibility organisations for packaging, industrial and automotive batteries, and some waste electrical and electronic equipment. For Hungarian authorities, the new system shows positive short-term impacts with more reliable waste management data and enhanced recycling. However, difficult access to waste market information and limited flexibility to adapt to recycling market developments may increase operating costs and be detrimental in the longer term. Companies and operators claim the system has removed incentives for private investments in recycling infrastructure, and that product fees do not reflect the costs of end-of-life management.

1.4.4. The shift to a circular economy

Hungary has taken steps to improve the resource intensity of its economy. There are ongoing efforts to include resource efficiency and circular economy considerations into some sectoral policies. For example, the National Environmental Technology Innovation Strategy includes 17 targets for sustainable resource management to be achieved by 2020. Some material use and material productivity indicators are included in environmental strategies such as the NFSSD and the fourth NEP. However, these targets are indicative and often remain disconnected from other policy measures and mechanisms.

There are several non-governmental circular economy initiatives and a growing interest in this issue from the private sector. So far, however, the Hungarian government perceives the transition to a circular economy as an aspect of waste management, particularly in terms of increased recycling. There is limited consideration of other circular economy aspects such as sustainable material management. There is no institutional platform dedicated to the circular economy: co‑ordination between the Ministries of Agriculture, National Development and National Economy on this issue appears limited.

Recommendations on waste, material management and circular economy

Introduce a whole-of-government approach through collaboration between relevant ministries to steer the transition to a circular economy; develop a national circular economy action plan with measurable targets and timelines; improve the prominence and visibility of resource efficiency targets and circular economy measures in the Waste Management Plan and the Irinyi Plan on Innovative Industry Development Directions; establish a platform for broader co-operation between businesses, financial institutions and other stakeholders to promote development of a circular economy.

Design and implement additional incentives for municipalities to strengthen waste management performance and allow for greater flexibility for municipalities in waste management planning; encourage best practice exchanges between municipalities by supporting associations of local authorities or environmental NGOs in developing guidelines, training and best practice recognition initiatives.

Continue improving door-to-door separate waste collection; introduce deposit-refund or pay-as-you-throw schemes for glass.

Evaluate the impact of new fixed waste tariffs for households on waste management performance and on the viability of waste management companies and infrastructure projects; consider raising waste tariffs, while compensating vulnerable households for the costs of waste management services; continue increasing the landfill tax to levels initially foreseen to encourage more separate collection and recycling efforts by municipalities.

Monitor the impact and evaluate the performance of state-operated extended producer responsibility schemes on long-term waste management performance, overall costs and promotion of eco-design of products; ensure that product fees reflect end-of-life management costs, are predictable and encourage private sector investment.

1.5. Biodiversity

Hungary’s vast grasslands, caves, rivers and wetlands are home to an abundance of biodiversity, including species that are found nowhere else in the world. The region is particularly significant to birds, with hundreds of thousands using the salt marshes and shallow alkaline lakes to rest and feed during annual migration. The region harbours 17% of the priority species listed in the EU Habitats Directive and 36% of species listed in the Birds Directive, despite representing only 3% of EU territory. This gives Hungary great responsibility for protecting biodiversity.

1.5.1. Trends and pressures on biodiversity

Like most countries, Hungary did not achieve the objective set by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) to significantly reduce the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010, despite improvement between 2007 and 2013. In 2013, over 80% of Sites of Community Importance remained in an unfavourable state, although Hungary’s performance was better than the EU average. The status of forests improved the most, with other habitat types seeing modest improvement. Around 56% of 1 026 natural and artificial water bodies have been classified as at risk from organic, nutrient or priority substances listed under the EU Water Framework Directive (GoH, 2014). Draining of flooded areas, impacts from agriculture and forestry, land-use change, fragmentation from development, municipal effluent, climate change and invasive species are among the greatest sources of pressures to habitats.

The status of species under the EU Habitats Directive improved between 2007 and 2013. However, 62% remain in bad or unfavourable condition. Invasive species are a significant issue, with over 13% of natural or near-natural habitats heavily infested (GoH, 2014).

1.5.2. Strategic and institutional framework

Hungary has a strong legislative framework to support biodiversity, and EU directives continue to heavily influence biodiversity policy. Its National Biodiversity Strategy for 2015‑20 is comprehensive and ambitious, with 20 objectives, 69 measurable targets and 168 related actions, including a set of indicators to measure progress. The strategy is linked to the Aichi targets under the CBD, which Hungary has been a party to since 1994. However, the strategy has insufficient influence over other ministries beyond the Ministry of Agriculture. The interim evaluation expected in 2018 will provide an important indication of progress in implementation. International agreements have played a role in influencing biodiversity measures. Indeed, Hungary has prepared its own national regulation to implement the Nagoya Protocol on access to genetic resources and fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from their use. All but one native species listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) are strictly protected. Hungary’s co‑operation with countries sharing the Danube River Basin has also been important to its protection and rehabilitation.

As noted in Section 1.2, Hungary has significantly transformed its governance systems relating to the environment and biodiversity. Biodiversity policy is now the responsibility of the Ministry of Agriculture, following its merger with the Ministry of Environment in 2010. Water management was transferred to the Ministry of Interior. While biodiversity governance is mainly centralised, environment and nature regulatory enforcement has been transferred to consolidated government offices at the county and district levels. This move provides a growing role for local authorities. The merger of biodiversity responsibilities within the same ministry that is responsible for agriculture, forestry and fisheries has resulted in some positive co‑ordination benefits. However, the changes have also led to confusion regarding roles and responsibilities and a lack of capacity at district offices. Greater effort is needed for clear overarching policy direction, effective co‑ordination across relevant organisations, and monitoring and evaluation of the results of policies and programmes. District offices require more financial and human resources.

There are 50 to 60 NGOs in Hungary working on nature conservation, employing 80 to 120 staff. The Ministry of Agriculture’s Green Fund that supports nature conservation activities of NGOs was reduced by one-third between 2011 and 2014 (Thorpe, 2017). In addition, recent legislative changes have increased requirements for NGOs receiving foreign financing. The drop in financing is ill-timed, given the growing need for NGOs to play a role in overseeing progress in nature conservation and fill gaps in government monitoring and evaluation.

1.5.3. Information systems

Hungary has a relatively well-developed monitoring system for habitats and species in protected areas. It has made significant investments in the conservation of genetic resources. However, ecological data at the local level, outside of protected areas, is limited. This lack of information can hinder adequate assessment of the impacts of development projects such as transportation infrastructure. Hungary has launched a project to improve data collection, monitoring and research related to biodiversity. It will map and assess ecosystems and their services within and outside protected areas by 2020. This information will be invaluable to support policy making and environmental impact assessments. This could serve as a foundation for the determination of monetary values associated with ecosystem services. With only 10% of Hungarians familiar with the term biodiversity, further effort is needed to improve public awareness. Gaps in the availability and accessibility of data should also be addressed. This should allow for greater involvement of NGOs and academic researchers in the assessment of progress and identification of priorities for action.

1.5.4. Protected areas

Protected areas are the main tool for biodiversity conservation and sustainable use. Hungary has already surpassed the Aichi target to protect 17% of land and inland waters by 2020, with a total protection of over 22% (GoH, 2014). It was one of the first EU member states to have its Natura 2000 network of protected areas declared complete. The proportion of protected grasslands is double the EU average.

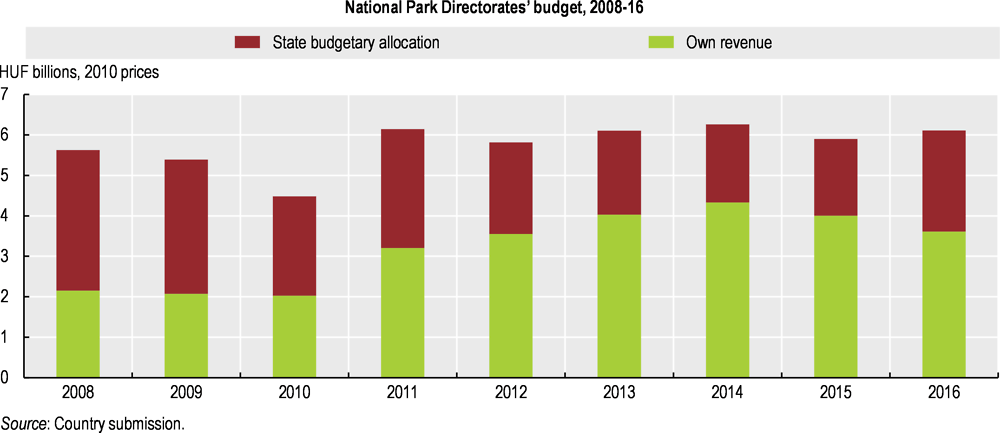

The total area protected has remained relatively stable since 2008, but work remains to complete management plans for all the protected areas. While there have been significant improvements since 2008, only 8% to 10% of protected areas had binding management plans in 2016. There is also less coverage of species types than habitat types across protected areas, and a shortage of park rangers. Habitat reconstruction and development have been carried out on 5% of Natura 2000 areas and 10% of nationally protected areas. In addition, some targeted species conservation projects have proceeded with EU funding. Efforts to manage invasive species have taken place within and outside of protected areas. Further effort is needed to improve the status of species in Hungary, both within and outside of protected areas. The most significant issue appears to be a lack of public financing for National Park Directorates. These directorates are driven to expand ecotourism facilities and seek EU subsidies for environmentally friendly farming in protected areas to raise sufficient revenue to fund operations (Figure 4). Programmes outside of protected areas are also very limited.

Figure 4. National Park Directorates increasingly rely on non-budget revenue sources

1.5.5. Economic instruments and other policy tools

Economic instruments that support biodiversity conservation and sustainable use include several taxes, fees and charges for use of protected areas, water use, fishing licences and land conversion. Subsidies encourage good environmental practices in agriculture, forestry and aquaculture. These instruments could be expanded to address pressure on biodiversity from pesticide use.

1.5.6. Financing biodiversity

The Ministry of Agriculture does not allocate an independent budget to the Department of Nature Conservation or the Department of National Parks and Landscape Protection. Capital, county and district government offices receive a general budget with no specified allocation for nature conservation. The National Park Directorates do receive dedicated funding. However, they generate a significant proportion of their budget through revenue raised from environmentally friendly farming eligible for EU agricultural grants and ecotourism.

EU nature conservation funding under the Environment and Energy Efficiency Operational Programme and the Competitive Central Hungary Operational Programme is lower for 2014-20 than for 2007-13. However, it is still significant (HUF 34.3 billion compared to HUF 45.3 billion). The drop in EU funding is due to shifting priorities and the near completion of projects such as nature education facilities. Hungary continues to receive significant funding from the Nature and Biodiversity Component of the EU LIFE programme, with 19 projects financed between 2008 and 2016. Hungary should consider gradually reducing its reliance on EU funds, potentially through revenue raised from new or enhanced economic instruments.

1.5.7. Mainstreaming biodiversity across sectors

Hungary has done relatively well at mainstreaming biodiversity into the strategic plans for agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors. These sectors are included in the National Biodiversity Strategy and managed under the same ministry. However, it has been less successful at implementation, and in integrating biodiversity considerations into other sectoral strategies, notably for energy, transportation, tourism and industry.

Agriculture features prominently in the National Biodiversity Strategy. However, additional measures are needed to address ammonia emissions, pesticide use and cultivation of flooded land. While Hungary’s preferred policy tools for the agricultural sector are information and subsidy programmes, a shift towards regulation or taxation may be needed if these do not yield results. Subsidies for environmentally beneficial practices should extend to the modernisation of irrigation systems. Hungary has committed to review support policies detrimental to the preservation of agricultural biodiversity. These could include measures supporting flood protection that encourage the drainage of wetlands important to birds and other species. The 2014 Action Plan for Developing Organic Farming sets a target to double the organic farming area by 2020, but this will be difficult to achieve.

Aquaculture production in Hungary grew by almost 35% between 2000 and 2015 (FAO, 2017). Fish farms can help support biodiversity, including the birds and otters that feed from them. However, there are also risks from the escape of non-native species, disease transmission to wild fish, effluents that cause eutrophication and use of ecologically sensitive lands, particularly for intensive aquaculture. The Fisheries Operational Programme of Hungary 2014-20 incorporates objectives related to biodiversity protection, and aquaculture producers are eligible for EU subsidies for conversion to environmentally friendly aquaculture practices.

Hungary’s forest area has increased from a low of 11% in the mid-20th century to almost 23% today. The government has set a goal of reaching 25-26% by 2050 (GoH, 2014). However, over 40% of the forest consists of plantations of mainly non-native species, including some that could be harmful to biodiversity. Recent changes to the Forest Act have raised concerns about a weakening of biodiversity safeguards and a shift from sustainable forest management. Afforestation on protected areas can only be done with native tree species, but there are fewer restrictions elsewhere. The proportion of production forest with sustainability certification did, however, increase from zero in 2000 to 25% in 2014. There is potential to further improve coverage (FAO, 2015).

Outside the agriculture, forestry and fishery sectors, a key tool for mainstreaming is spatial planning. Hungary’s National Spatial Plan, developed by the Prime Minister’s Office in consultation with different ministries, defines specific zones. It provides detailed regulation of development that can take place within each zone. For biodiversity protection, a National Ecological Network includes habitats of national importance and a system of ecological corridors and buffer zones that link the core areas together. In 2016, the network covered an impressive 36.4% of the country. Energy and transport infrastructure is permitted within the zone if technical solutions that ensure the survival of natural habitat and functioning of ecological corridors are incorporated. In practice, however, it is not always clear that biodiversity considerations are given the same weight as economic interests. This may be due to a lack of biodiversity expertise and territorial-level indicators to support decision making.

The network of roads and rail poses a significant cost in terms of habitat loss and fragmentation, estimated at HUF 54 billion per year in 2009 (Lukács et al., 2009). Between 2009 and 2016, Hungary built an additional 394 km of new highways. Biofuels and biomass production for electricity and heat can also encourage agricultural expansion, as well as associated impacts on biodiversity. Hungary is one of the largest bioethanol producers in the European Union. However, the use of land for conventional biofuel production in Hungary decreased by 4% between 2000 and 2014, while production and sales of biofuels increased significantly. The volume of biomass used for electricity and heat is too small to have a significant impact on land-use change, but future growth in tree plantations could become an issue. It will be important to monitor the impacts of biofuel production on land use and biodiversity regularly, ideally through the development of publicly available indicators.

Tourism is increasingly a pressure on biodiversity in Hungary. Overall visits increased by almost 20% between 2009 and 2016, and there was significant interest in protected areas. There is, however, limited restriction on tourist activities outside of protected areas. Hungary’s National Tourism Development Strategy 2030 and the National Environmental Programme emphasise growth in tourism, but without specific measures to address potential negative environmental impacts. Industry can also have a significant impact on biodiversity, as demonstrated by the spill of red sludge from an alumina factory in 2010. The potential for growth in mining and fossil fuel extraction in Hungary also increases the importance of adequate measures to protect vulnerable ecosystems and species in areas of possible development. Better integration of biodiversity considerations into sectoral strategies relevant to industry, with specific commitments and indicators, will be important to limit impacts of growth on biodiversity.

Recommendations on biodiversity protection

Strategic and institutional framework

Expand the National Biodiversity Strategy to incorporate specific commitments and indicators related to energy, transport, tourism, industry and mining; improve policy coherence and cross-linkage with sectoral strategies and plans; ensure clear accountability for achieving targets; identify financial and human resources for specific actions to achieve targets.

Information systems

Continue to improve knowledge of the extent and value of ecosystem services and habitat and soil maps within and outside protected areas, sectoral data sharing, and accessibility and communication of information to the public.

Biodiversity protection and financing

Ensure measures are in place to enhance the conservation status of threatened species, both in and outside protected areas by improving wildlife corridors and restricting infrastructure expansion to reduce fragmentation of habitats.

Complete management plans of protected areas with legal force and ensure sufficient financial resources for effective implementation; provide dedicated budgets for nature conservation departments to improve the predictability of financing and reduce the risk of shifting short-term priorities; increase budget funding for National Park Directorates to reduce the need for substantial revenue-raising activity that may be contrary to biodiversity objectives.

Mainstreaming biodiversity across sectors

Implement additional measures in the agricultural sector to reduce ammonia emissions, curb pesticide use and limit cultivation of flooded land; use subsidies and payments for ecosystem services and information provision to promote the modernisation of irrigation systems, nature conservation and restoration activities outside of protected areas; significantly increase the share of organic farming.

Expand afforestation of indigenous species beyond protected areas; increase sustainability certification of forest companies; maintain sustainable forest management objectives.

Improve the effectiveness of the National Ecological Network Zone instrument and other spatial planning policies by developing regional-level biodiversity indicators and using biodiversity experts to support informed decisions; avoid destruction of green space and fragmentation of habitat where possible, including in areas with no formal protection.

Monitor the impact of biofuel and biomass production on land-use change and other factors influencing biodiversity, producing publicly available indicators to help inform decision making; give preference to added-value organic farming over biofuel and biomass production.

References

EC (2017a), The EU Environmental Implementation Review, Country Report – Hungary, Commission Staff Working Document, SWD (2017) 46 final, European Commission, Brussels, 3 February 2017, http://ec.europa.eu/environment/eir/pdf/report_hu_en.pdf.

EC (2017b), Country Report Hungary 2017, Commission Staff Working Document accompanying the document “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Central Bank and the Eurogroup 2017 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011”, Staff Working Document, SWD (2017) 82 final/2, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2017-european-semester-country-report-hungary-en_1.pdf.

EC (2015), “Climate change”, Special Eurobarometer, No. 435, May-June 2015, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/sites/clima/files/support/docs/report_2015_en.pdf.

EC (2014), “Attitudes of European citizens towards the environment”, Special Eurobarometer, No. 416, April-May 2014, European Commission, Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/archives/ebs/ebs_416_en.pdf.

EEA (2016), Air Quality in Europe: 2016 Report, EEA Report, No 28/2016, Publications Office of the European Union, European Environment Agency, Luxembourg, www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2016.

Eurostat (2017), Shares 2015 (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/energy/data/shares (accessed 20 November 2017).

FAO (2017), FAO Statistics, Global Aquaculture Production website, www.fao.org/fishery/statistics/global-aquaculture-production/en (accessed 18 June 2017).

FAO (2015), Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 website, www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/en/ (accessed 25 June 2017).

Flues, F. and K. van Dender (2017), “The impact of energy taxes on the affordability of domestic energy”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 30, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/08705547-en.

GoH (2014), Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity – Hungary, Government of Hungary, April 2014, www.cbd.int/doc/world/hu/hu-nr-05-en.pdf.

Harding, M. (2014), “Personal tax treatment of company cars and commuting expenses: Estimating the fiscal and environmental costs”, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No. 20, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz14cg1s7vl-en.

HCSO (2017), STADAT (database), www.ksh.hu/?lang=en (accessed 25 November 2017).

IEA (2017), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Hungary 2017, IEA, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278264-en.

Lukács, A. et al. (2009), “The social balance of road and rail transport in Hungary”, joint study prepared by the Institute for Transport Sciences and the Clean Air Action Group (Hungary), commissioned by the Hungarian Ministry of Economy and Transport in 2008, www.levego.hu/sites/default/files/1988-2015_caag_history.pdf.

OECD (2017a), “Hungary”, in Economic Policy Reforms 2017: Going for Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/growth-2017-25-en.

OECD (2017b), Development Co-operation Report 2017: Data for Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2017-en.

OECD (2016a), OECD Economic Surveys: Hungary 2016, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-hun-2016-en.

OECD (2016b), Effective Carbon Rates: Pricing CO2 through Taxes and Emissions Trading Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260115-en.

OECD (2016c), Fossil Fuel Support Country Note – Hungary, September 2016, http://stats.oecd.org/wbos/fileview2.aspx?IDFile=37348365-0442-4dd3-8d38-706eb3ad2dfa.

OECD (2015), Taxing Energy Use 2015: OECD and Selected Partner Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264232334-en.

Roy, R. and N. Braathen (2017), “The rising cost of ambient air pollution thus far in the 21st century: Results from the BRIICS and the OECD countries”, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 124, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d1b2b844-en.

Thorpe, N. (2017), “Hungary approves strict regulations on foreign-funded NGOs”, BBC News, 13 June 2017, www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-40258922.

Tirado Herrero, S. and D. Ürge-Vorsatz (2012), “Trapped in the heat: A post-communist type of fuel poverty”, Energy Policy, Vol. 49, pp. 60-68, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421511006884.

World Bank (2015), Water and Wastewater Services in the Danube Region – Hungary Country Note, May 2015, World Bank and International Association of Water Supply Companies in the Danube River Catchment Area, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/653681467998782643/Water-and-wastewater-services-in-the-Danube-region-Hungary-country-note.

Annex 1.A. Actions taken to implement selected recommendations from the 2008 OECD Environmental Performance Review of Hungary

|

Recommendations |

Actions taken |

|---|---|

|

Environmental performance: Trends and recent developments |

|

|

Further improve the pollution, energy and resource intensities of the Hungarian economy; promote sustainable production and consumption patterns. |

Energy and resource efficiency are key elements of the Framework Strategy on Sustainable Development 2012-14, and of the Environmental Technology Innovation Strategy 2011-20. The strategies include resources management and efficiency targets and related monitoring indicators, supporting the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. |

|

Identify priority measures for mitigation of and adaptation to climate change based on an analysis of their cost effectiveness; ensure the co-ordinated implementation of the National Climate Change Strategy with energy, transport, agriculture and water policies. |

Specific financing schemes have been introduced to support the energy, climate and green growth objectives indicated in the NCCS (e.g. the Green Investment System and Green Financing Schemes). More needs to be done in the areas of co-ordination with sectoral strategies and in the assessment of the costs and related investment needs. |

|

Ensure competitiveness in the energy sector, in the EU context, to improve its environmental and economic performance; take further steps to increase energy efficiency in all sectors of the economy. |

Main measures implemented under the National Energy Strategy to 2030 include incentives for more efficient heating systems, improved insulation of buildings in the residential and public sectors; and support of electro-mobility and low-carbon modes of transport. Large enterprises must conduct energy audits every four years. Energy efficiency investments are eligible for a tax allowance. However, the implementation of different objectives across sectors needs to be better co-ordinated and monitored. |

|

Strengthen measures for reducing air emissions, especially from the transport and residential sectors, so as to meet national emission ceilings and limit values for ambient air quality. |

The requirements of the EU Air Quality Directive have been transposed into the national legislation and entailed the revision of air quality standards. Hungary reduced emissions of main air pollutants in most sectors, decoupling them from output growth. However, PM2.5 concentrations remain above the WHO standards in many cities, and mortalities rates due to air pollution are among the highest in Europe. |

|

Further develop traffic management in urban areas (e.g. traffic restrictions in city centres, parking and road pricing) and continue to promote integrated public transport in major cities; give municipalities better control over their revenue sources and traffic management tools. |

Sustainable urban mobility plans have been developed in most cities, driven by EU financing requirements. Traffic management systems have been introduced in Budapest, Miskolc and Debrecen and include parking fees. The E-mobility Programme also contributes to better transport management. |

|

Speed up implementation of the Drinking Water Quality Improvement Programme, with the aim of having all public water supply comply with drinking water quality limit values. |

Despite considerable improvements in the drinking water quality and the increased compliance with the microbiological parameters (95% to 99%), there are still some areas not complying with the requirements of the Drinking Water Directive (e.g. for chemical parameters). |

|

Further strengthen the flood prevention and control efforts; further enhance the ecosystem and land use approach to flood management; develop a flood insurance policy. |

Hungary has designed flood hazard maps, a High Water Level Riverbed Management Plan. The development of a Flood Risk Management Plan is ongoing. Water storage reservoirs have been developed along the Tisza river, and further increases of storage capacity for flood emergency management are planned. |

|

Pursue efforts to connect the population to waste water treatment so as to prevent widespread bacterial contamination of large rivers. |

The length of the public sewerage network almost doubled since 2000 and the cleaning efficiency of the sewerage network improved. The share of population connected to public wastewater treatment increased to 78% in 2016, albeit unevenly spread across regions. However, it remains one of the lowest rates in the OECD. In 2011, the government passed a regulation requiring compulsory connection of property owners to public sewers. |

|