This chapter takes a look at the institutional capacities required for the sound implementation of the Brazilian digital government policy, in line with Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies. It starts by focusing on the digital skills panorama in Brazil’s federal public administration. It then assesses the institutional mechanisms in place to streamline information and communication technology (ICT) investments in the public sector, namely cost-benefit analysis, business cases and project management standards. The chapter closes with a section dedicated to the analysis and discussion of the ICT procurement context in Brazil, focusing on the institutional tools in place to reinforce the coherency of ICT spending in the country’s federal government.

Digital Government Review of Brazil

Chapter 3. Strengthening institutional capabilities for the sound implementation of digital government policy in Brazil

Abstract

Introduction

As the digital transformation reaches more policy areas and government sectors, effective, coherent and sustainable implementation requires alignment among policy planning, design, development, implementation and monitoring. Governments are required to adapt their models of leadership, institutional set-ups and co-ordination (see Chapter 2) as well as their policy capacities to support the transformation across sectors and levels of the public administration (OECD, forthcoming[1]).

This chapter focuses on the analysis of the digital government context of Brazil in light of Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies, which invites governments to build and/or strengthen the institutional capacities required to seize the opportunities and tackle the challenges of a progressive digitalisation of the public sector (OECD, 2014[2]). A set of key recommendations calls on governments to ensure their capabilities to implement projects and initiatives through strategic building blocks and policy levers that can promote co-ordinated and coherent policy actions.

The chapter starts by examining and discussing the digital skills panorama in the Brazilian civil service. It then analyses the policy mechanisms and tools in place to streamline information and communication technology (ICT) investments in the public sector. The third section and final section of this chapter discusses the ICT procurement context in Brazil, and in particular, the existence of a strategy and guidelines that can reinforce the coherency of ICT spending in its public sector.

Building digital capacities and skills

Transforming governments through skills

Increasing citizens’ expectations on efficiency, openness and inclusiveness of the public sector and the services delivered demands new skills across all sectors and activities, which requires governments to strongly invest in civil service talent, capacities and competences for a sustainable digital transformation.

Nevertheless, the discussion on the skillsets required for a digital government to be fully functional remains open, and governments worldwide continue to be deeply involved in the debate around the actions they can take to be prepared for the digital transformation. What capabilities do public sectors require to shift from an e-government approach to a digital government imperative? What are the consequences for a strategic management of public employment? What role should civil servants play in a digitally transformed public sector and what will the civil service look like in the future (OECD, forthcoming[1])?

Assuming the digital disruption underway is an irreversible process, public servants will be required to obtain and maintain digital skills that can allow them to be part of a digital economy and a digital government.

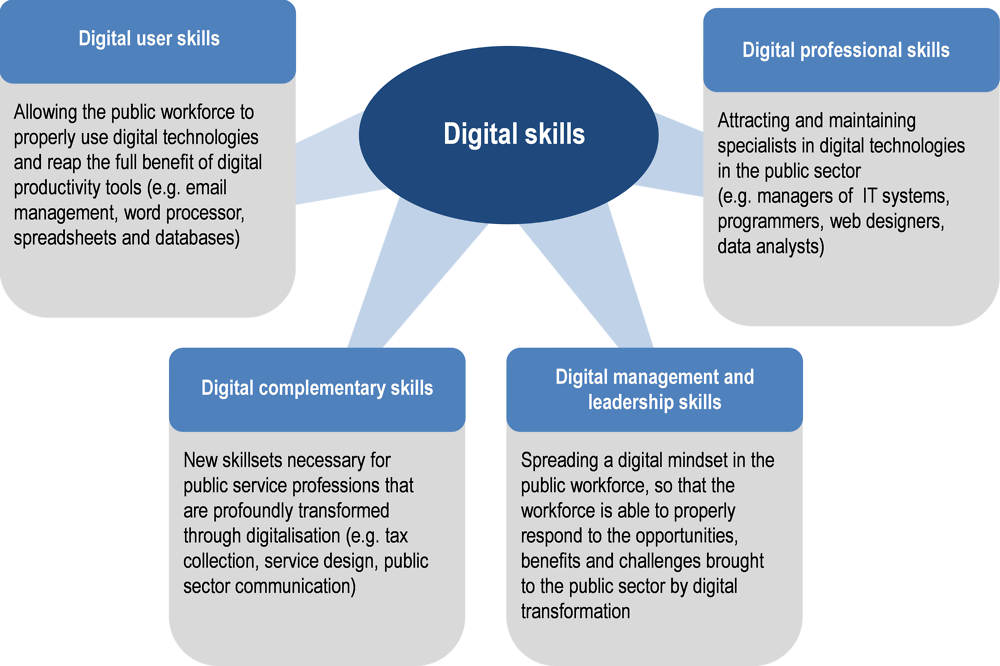

Figure 3.1. Types of digital skills required by civil servants in the context of a digital transformation of the public sector

Source: Author, based on OECD (2017[3]), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

The types of skillsets presented in Figure 3.1 reflect the necessary change of paradigm when considering the competences and abilities that civil servants will need in the context of digital transformation. The majority of civil servants’ profiles require more or less developed digital user skills, as being productive increasingly implies using specific information technology (IT) tools. On the other hand, in the context of the digital transformation of public sectors, the wide use of technology (including emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence [AI]) and data means the introduction of new specialised IT roles. Establishing new professions to bring in the right capabilities (or retraining existing staff) therefore becomes a requirement for governments to be able to count on a public sector workforce ready to adjust and leverage the opportunities brought about by rapid technological evolution (see the section on “ICT career paths and other instruments to attract and retain ICT professionals”, below).

A third group of digital skills is increasingly considered essential. Digital complementary skills based on strong digital awareness and dexterity are now required in diverse professional roles. For example, core government functions such as communications, tax collection, project management, audit, and citizen engagement (to name just a few) are being fundamentally transformed to take advantage of new digital technologies, and each of these areas will require new skills and competencies to perform these functions effectively in a digital environment. This gets to the heart of a digital transformation culture, which recognises the broad impact of digital disruptive trends and positions the public sector to better seize its innovative potential and tackle its risks.

Establishing such a culture is an urgent challenge for organisational leadership, suggesting a fourth group of digital skills. Senior level public servants do not need to be digital experts, but it is clear that traditional notions of public service leadership, based on legal compliance and bureaucratic process management, will need to be updated in light of the digital transformation. In a parallel project, the OECD is working with senior officials in the federal government of Brazil to identify the kinds of leadership competencies and skills needed to strengthen a culture of innovation, and to lead a successful digital transformation (OECD, forthcoming[4]).

The strategic investment in digital complementary skills and digital leadership skills among public officials should reflect governments’ clear recognition that the digital transformation is not a technical issue, but also contains a cross-cutting people-management challenge that needs to be addressed with skills that go far beyond technical domains.

Policies to cultivate a culture of digital skills in the public sector

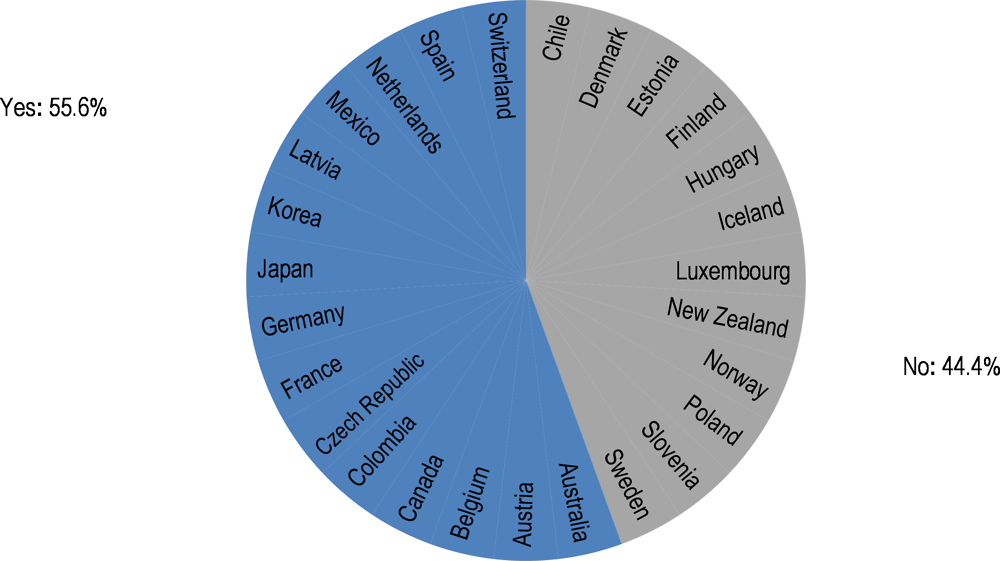

Although the context presented above demonstrates the importance of strategic policies to promote digital skills and adjust job profiles in the public sector, almost half of OECD countries confirmed not having strategies to attract, develop or retain ICT-skilled public servants (see Figure 3.2). Digital skills are, in this sense, a policy issue that deserves increased attention and support from governments.

In Brazil, evidence gathered for this review points to the fact that skills are generally considered a key requirement for the implementation of a bold and sustained digital government policy. Different actors interviewed in the context of this review recognised that civil servant capacities to properly work in digital transformation contexts are critical.

Figure 3.2. Existence of strategies to attract, develop or retain ICT-skilled civil servants in government

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating countries that responded yes or no to the question, “Do you have a dedicated strategy to attract, develop or retain ICT-skilled civil servants in government?”

Source: OECD (2014[6]), “Survey on Digital Government Performance”, OECD, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796.

A vast majority of Brazilian federal and state government employees uses the Internet in their activities. Data show that 85% of federal government institutions report that 76‑100% of their employers used the Internet in the last 12 months and 77% of state institutions report the same range of use (see Table 3.1). Similarly, 100% of federal-level public sector organisations report having an IT department or sector, and 83% at the state level also report having one (see Table 3.2).

Table 3.1. Civil servants using the Internet in Brazil

Federal and state government organisations by percentage range of employed persons who used the Internet in the last 12 months

|

|

Percentage (%) |

Up to 25% |

26-50% |

51-75% |

76-100% |

Does not know |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Branch |

Executive |

3 |

6 |

12 |

77 |

1 |

|

Legislative |

0 |

9 |

16 |

68 |

7 |

|

|

Judiciary |

1 |

1 |

10 |

83 |

5 |

|

|

Public Prosecutor's Office |

0 |

0 |

14 |

83 |

3 |

|

|

Level of government |

Federal |

1 |

1 |

9 |

85 |

4 |

|

State |

3 |

6 |

13 |

77 |

1 |

Source: CETIC (Brazilian Internet Steering Committee) (2017[7]), “ICT Electronic Government 2017 - Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in the Brazilian Public Sector”, http://cetic.br/publicacao/pesquisa-sobre-o-uso-das-tecnologias-de-informacao-e-comunicacao-tic-governo-eletronico-2017/.

Table 3.2. Public sector organisations with an IT department in Brazil

|

|

Percentage (%) |

Yes |

No |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Branch |

Executive |

81 |

19 |

|

Legislative |

100 |

0 |

|

|

Judiciary |

100 |

0 |

|

|

Public Prosecutor's Office |

100 |

0 |

|

|

Level of government |

Federal |

100 |

0 |

|

State |

83 |

18 |

Source: CETIC (Brazilian Internet Steering Committee) (2017[7]), “ICT Electronic Government 2017 - Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in the Brazilian Public Sector”, http://cetic.br/publicacao/pesquisa-sobre-o-uso-das-tecnologias-de-informacao-e-comunicacao-tic-governo-eletronico-2017/.

Digital complementary and leadership skills were also widely recognised during the fact-finding interviews for this review as a requirement for more effective and co-ordinated development of digital government in Brazil. The stakeholders underlined the need to cultivate and spread a digital transformation culture across the public sector, namely in leadership positions across the Brazilian federal administration. Policy makers, decision makers and policy implementers should have the digital mindset that would allow government to reap the full benefits of digital technologies in the design and implementation of policies, initiatives and projects.

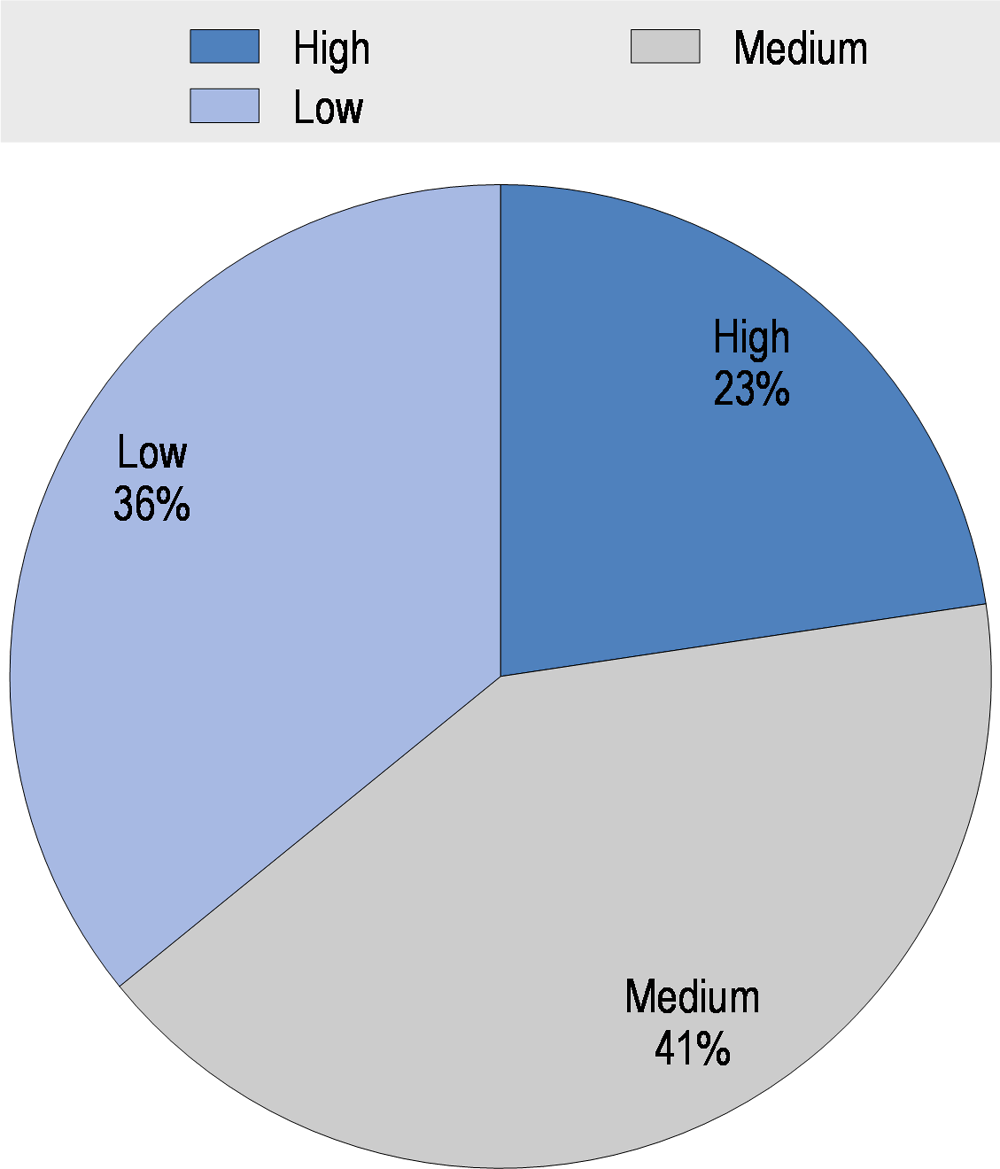

Despite the fact that the data and stakeholder perceptions mentioned above show the relevance and need for strategic digital skills in the Brazilian public sector, the Digital Governance Strategy (Estratégia de Governança Digital, EGD) doesn’t foresee any specific actions to reinforce the digital capabilities of Brazilian civil servants. Furthermore, when questioned about the level of priority given to the improvement of digital skills in Brazil’s digital government policy, 77% of the public sector organisations that responded to the OECD Digital Government Performance Survey consider it a low or medium priority (see Figure 3.3).

Although the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD) fails to include actions related to building digital skills, some initiatives highlight the Brazilian government’s willingness to reinforce digital skills capabilities in the public sector.

The Information Technology Servants Improvement Programme (Programa de Aperfeiçoamento dos Servidores de Tecnologia da Informação, PROATI) provides training courses to public sector IT professionals in order to keep up to date and improve their digital skills. The programme is an initiative of the Secretariat of Information Technology (SETIC) of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, which provides a wide range of courses focused on areas such as IT procurement, management of IT systems, information security management and data and information governance (Ministério do Planejamento,(n.d.)[10]) (SISP, 2018[11]). In the same line, the National School of Public Administration (ENAP), in partnership with SETIC, also provides several training programmes to improve the skills of IT public servants, including post-graduate courses (OECD, 2018[12]).

Figure 3.3. Perceptions about the priority attributed to digital skills in the digital government policy of Brazil

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded High, Medium or Low to the question, “How would you classify the level of priority given to the improvement of digital skills and competencies in Brazil’s digital government agenda?”

Source: OECD (2018[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

ICT career paths and other instruments to attract and retain ICT professionals

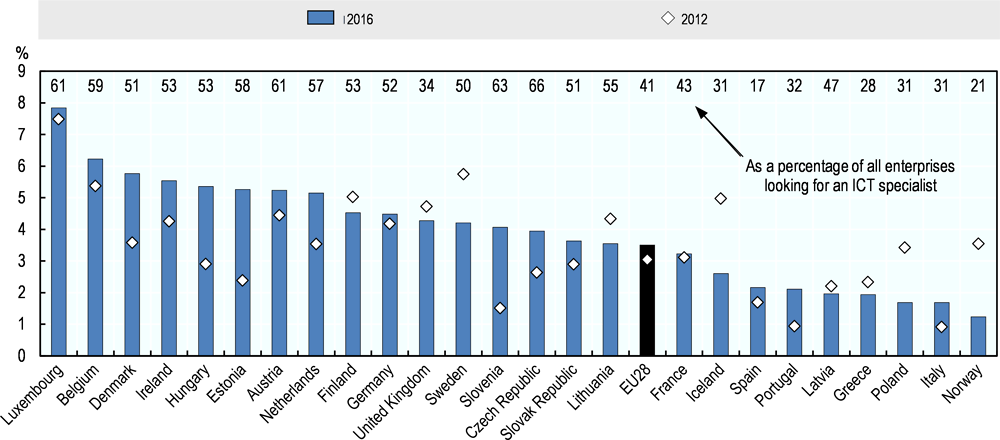

As previously mentioned, the rapid uptake and the growing diversity and complexity of digital technologies required across different sectors and levels of government pose increasing challenges for public sectors to attract, retain and keep updated IT professional civil servants (see Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4. Firms that reported hard-to-fill vacancies for ICT specialists in OECD countries

Source: Eurostat, Digital Economy and Society (database), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/digital-economy-and-society/data/comprehensive-database (accessed June 2017), in OECD (2017[3]), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

A specific and clear career path can be a strategic instrument to attract, retain and develop skilled IT professionals in the public sector. Managing the careers of ICT professionals as a group can help to establish appropriately competitive conditions in terms of salaries and career progression, and help set expectations and opportunities for continuous lifelong skills development. This reinforced attractiveness of IT posts can contribute to improved recruitment and upgraded conditions to retain these professionals in the public sector.

In Brazil, there is a specific public administration job profile for IT professionals within the federal government called an IT Analyst (Analista em Tecnologia da Informação). Created in 2006, the job profile covers professionals focused on “planning, supervision, coordination and control of information technology resources related to the operation of the federal public administration” (Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão, 2018[13]).

Through evidence gathered for this review and from the results of the Digital Government Survey of Brazil, it appears that compensation offered by this career path makes it difficult to retain IT professionals Additionally, in the context of this review, the following concerns emerged:

1. Similarly to what happens in other career paths in the Brazilian public administration, the recruitment process of these professionals lacks the necessary accuracy and flexibility to attract and retain the best professionals, as well as the ability to respond rapidly and with agility to dynamic IT demands.

2. Due to a general lack of IT professionals in the federal government, most of them are not mobilised for specialised IT functions that might be more relevant to fostering a modern public sector (e.g. software development, user design, data analysis).

3. Given that other comparable careers in the public sector have better compensation packages, there is high mobility. This can be positive both from an individual, as well as an institutional, perspective (e.g. to share knowledge and foster horizontality), but it can jeopardise the institutions’ stability and capacity to retain knowledge.

An earlier OECD (2010[14]) review of human resource management (HRM) systems in the federal government of Brazil found that the career system, which regulates job professions, is highly rigid and limits job mobility, performance management processes and professional development opportunities. Given the cross-cutting and multi-faceted challenges posed by the digital transformation, efforts should be taken to ensure that ICT professionals are highly mobile and agile, and encouraged to upgrade their skillsets regularly to keep up with the fast pace of change. This may suggest a need to thoroughly revisit the career system as it functions in the Brazilian public administration.

Transformative skills for a 21st-century public sector in Brazil

Counting on adequately skilled public servants is critical to seizing the opportunities and tackling the challenges of the digital transformation of the public sector.

Considering its strong commitment to developing a robust digital government, the Brazilian government could consider prioritising the inclusion of digital skills development in future skills policies or frameworks for the public sector. If properly aligned with the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD), this would allow the government to better co-ordinate goals, initiatives and projects and develop the necessary digital capacities across the Brazilian public sector that would support the goal to transform its way of functioning. This would help the Brazilian administration better respond to the expectations expressed by the digital government ecosystem and to citizens’ increasing demands for efficiency, quality, openness and inclusiveness of the public sector.

In this respect, any updated skills policy for the public sector could benefit from input from the Secretariat of Information Technologies (SETIC) of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management. The necessary human and financial resources should also be in place to properly support the updated skills policy.

Given the assessment presented above, future-oriented skills policies should prioritise the development of digital skills based on the four types of digital skills presented in Figure 3.1 (user, professional, complementary and leadership). A mapping of the existing skills and of the short, medium and long-term needs for the Brazilian public sector would allow the government to take proper actions considering the present and avoiding future shortages.

Additionally, an IT-profession framework building on OECD country experiences (see Box 3.1), establishing clear IT professional roles in the public sector, could help update the IT careers framework in the public sector, and structure a future training strategy to support this. With an improved recruitment process and better career management, the Brazilian government would be better able to attract the best candidates available in the market and better adapt the diverse roles foreseen to the growing demands in the digital economy. This would also provide a basis to review compensation conditions to ensure that they are adapted, so as to attract the best professionals in the public sector and promote continuous career development.

Box 3.1. The Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework and the Government Digital Service in the United Kingdom

Two interesting initiatives from the UK government focus on the active promotion of digital skills in the public sector.

The Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework

Within the United Kingdom’s Civil Service, the Digital, Data and Technology (DDaT) function supports all departments across government to attract, develop and retain the people and skills to understand and contribute to government transformation. The function works namely on career management, attraction and recruitment, learning and development, and pay and reward. The Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework describes the roles of the DDaT profession, helping civil servants and civil society understand the required skills for certain jobs and also work on career progression. A data engineer, IT service manager, delivery manager or software developer are examples of the more than 30 roles identified. The DDaT Profession Capability Framework provides a good example of how a government can better manage digital professional skills in the public sector.

The Government Digital Service Academy

The Government Digital Service (GDS) Academy offers digital skills courses for specialised and non-specialised professionals. User research, user-centred design, and digital and agile awareness for analysts are some of the courses provided in the academy for civil servants and local government employees. The academy acts as an important instrument to disseminate digital skills across the public sector.

Source: GOV.UK (2017[15]), “Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework”, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/digital-data-and-technology-profession-capability-framework; GDS (2018[16]), “GDS Academy”, https://gdsacademy.campaign.gov.uk/.

Last but not least, building on the needs identified during the review, a clear priority should be attributed to the promotion of digital leadership skills, namely for top-level civil servants and decision makers. Supporting public sector leaders’ better understanding of the digital transformation underway is a strategic objective to support digital-by-design policies in the Brazilian public sector, able to integrate the benefits of digital technologies from the start in public sector initiatives and projects. This is a particular challenge in Brazil, where public sector leadership is mostly politically appointed, and there are no minimum criteria to ensure that leaders have the necessary skills. The OECD is currently working with key stakeholders to better assess the leadership skills necessary to drive innovation and the systems that need to be in place to support them.

Initiatives to build digital skill capacity among top-level civil servants have begun, however. ENAP has partnered with American institutions such as Harvard and Georgetown University. In 2018, ENAP offered a course for top-level civil servants on Digital Transformation in Government, in partnership with the University of Harvard. An annual course directed at top-level civil servants focusing on Innovation, Leadership and Digital Government has been offered by ENAP with Georgetown University.

Streamlining digital technology investments

Cost-benefit analysis

The rapid penetration of digital technologies in all sectors of government, streamlining internal processes and improving service delivery, means that the acquisition of IT goods and services assumes an increasing role in public procurement. Strategic and dynamic planning of the procurement of digital goods and services is required to ensure the efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability of investments and to avoid gaps and overlaps, as outlined in the principles of the 2015 OECD Council Recommendation on Public Procurement (OECD, 2015[17]). Strategic planning can also help overcome agency-thinking approaches that anchor silo-driven decisions and often do not consider interoperability requirements or common standards for improved integration and sharing (e.g. data exchange) across different sectors and levels of government.

ICT investments are also becoming increasingly complex. Governments today face multifarious choices due to the constant evolution of technologies that require different domains of expertise to be properly installed and managed. Additionally, governments need to be able to make critical decisions about opting among different alternatives, e.g. governments find themselves having to choose between the internal or external development of systems and tools, open or proprietary software, local or cloud-based hosting, etc. Different cost structures also need to be considered (e.g. specialised human resources, specific hardware, development of tailored software, security tests, usability tests, load tests, legal consulting services) to address dependencies on multiple variables (e.g. economic or social sector to be applied, profile of final users, expected demands, foreseen technological evolution, national or international regulations) (OECD, 2017[19]).

As highlighted in Chapter 2, the existence of an adequate digital government strategy, of proper institutional leadership and effective cross-sector co-ordination committees or steering groups are important requirements to guarantee the effective implementation of a digital government policy. Nevertheless, in line with Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies, governments across OECD countries and partner economies increasingly report the need to have policy levers ‑ including the pre-evaluation of ICT expenses, business cases and project management models – to ensure a coherent and sustainable digital transformation of the public sector. These policy tools can support governments to better plan, manage and monitor IT investments.

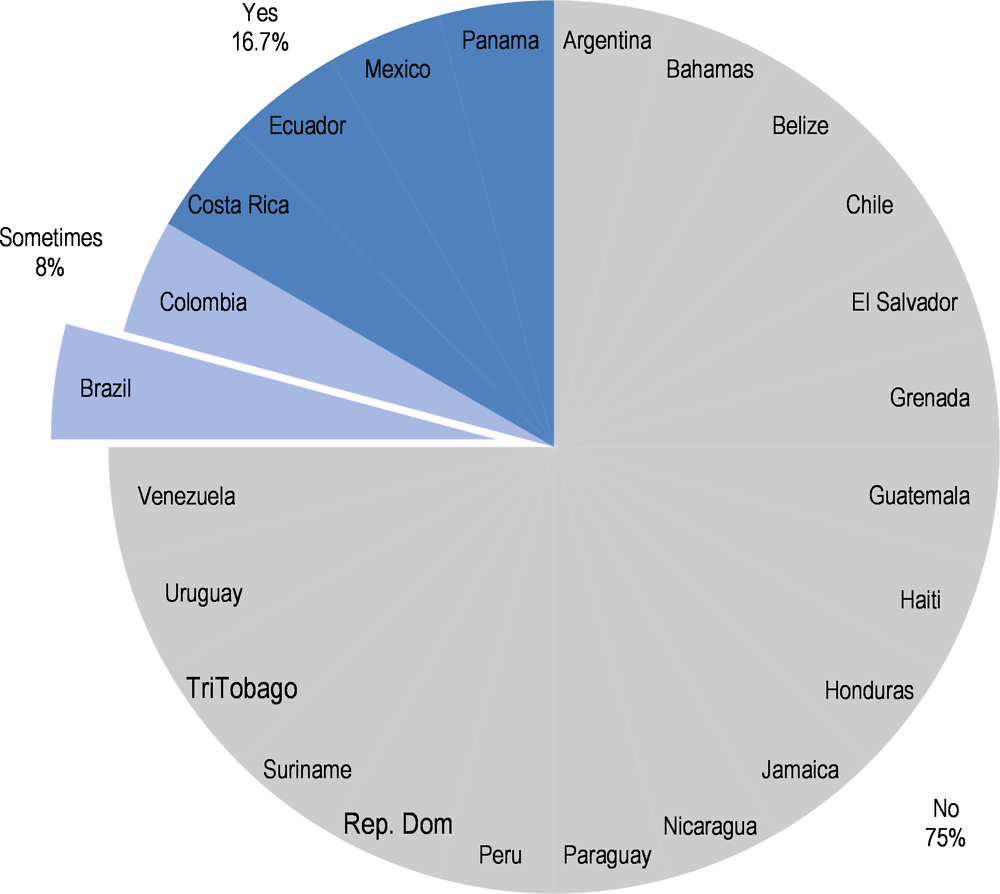

According to the OECD Digital Government Performance Survey, 33% of participating countries reported measuring the financial benefits of ICT projects in the central government, against 52% that reported doing it “sometimes” and 15% that reported not having this policy practice (OECD, 2014[6]). In the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) region, 17% of countries reported measuring the financial benefits of ICT projects in the central government, 8% reported doing it “sometimes”, but the vast majority (75%) reported not doing so (see Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. Cost-benefit assessment of ICT investments in the LAC region

Source: OECD (2016[18]), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

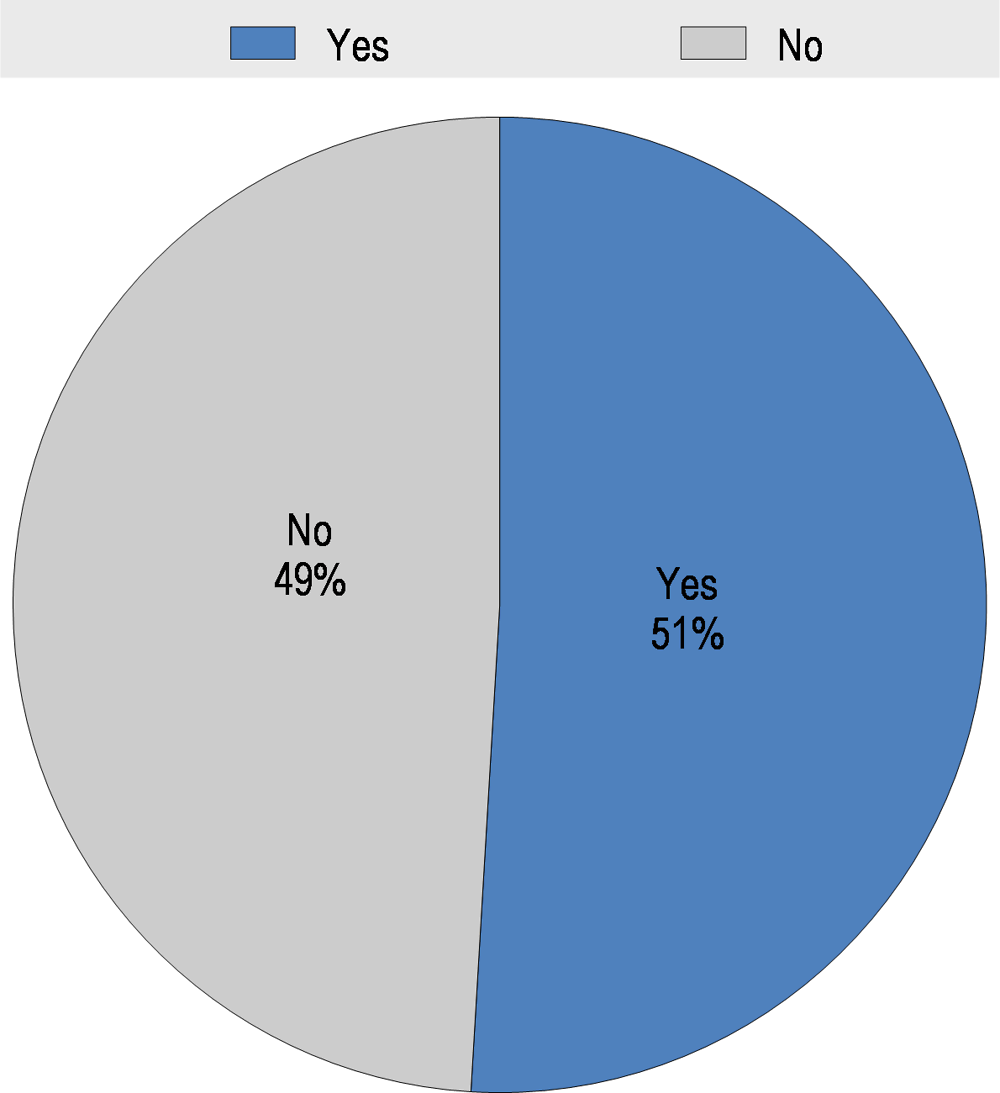

In Brazil, measurement of financial benefits for ICT projects in the federal government does not happen on a regular basis. It depends mostly on the practices of project development within each federal institution (see Figure 3.6). The same applies to the measurement of the financial benefits of ICT investments to citizens, businesses and specific population groups (OECD, 2018[12]).

The Ministry of Planning has defined a method for calculating services called the "Modelo de Levantamento de Custos do Usuário de Serviços” (Standard Cost Model), which is a methodology that measures the (often hidden) costs of using public services "with the objective of the model considering some variables, such as: time and resources spent to fulfill the requirements (multiple visits, queues, absences at work); diversity of documents and forms requested (xerox, endorsements, notary's office); and, production and maintenance of records / information1.

Figure 3.6. Estimation of financial benefits of ICT projects within the Brazilian public sector

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded yes or no to the question, “Does your institution estimate (ex ante) the direct financial costs and benefits of ICT projects?”

Source: OECD (2018[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

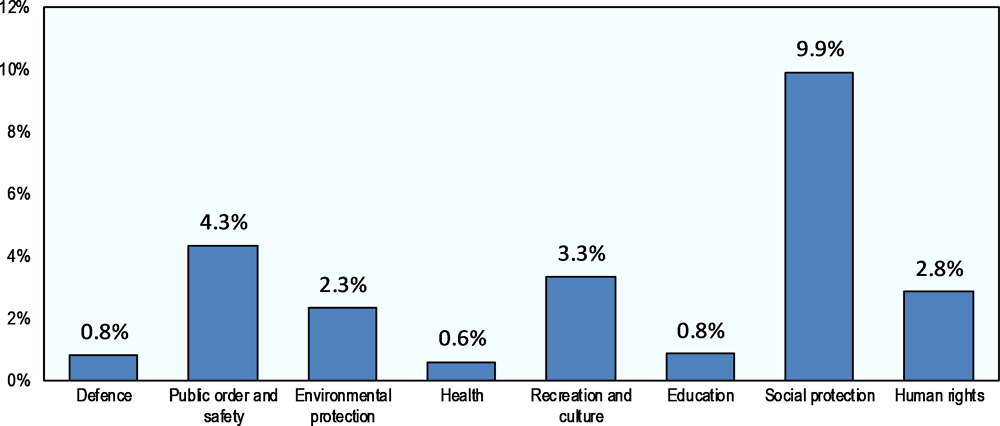

However, given the increasing volume of ICT expenses ‑ due to the pervasive and progressive digitisation of several sectors of activity (see Figure 3.7) ‑ there seems to be significant room for improvement in measuring financial benefits When questioned about the main challenges to the full realisation of direct financial benefits, the Brazilian public institutions that responded to the survey identified the following (OECD, 2018[9]):

insufficient knowledge of the final benefits expected when budgeting

insufficient political or high-level attention to the realisation of financial benefits

different objectives and priorities across the parts of the public administration engaged in the projects.

Although ICT expenses are typically around 3% or 4% when considering the total budgets per government sector in Brazil, their absolute value shows that strategic policy action is required to spread a culture of cost-benefit analysis.

Figure 3.7. Estimated breakdowns of federal government ICT spending in Brazil

Source: OECD (2018[12]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Central version, unpublished.

Pre-evaluation of ICT expenses and business cases

In line with the experience of some OECD countries (e.g. Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, Portugal), the establishment of budget thresholds for digital technology projects above a determined budgetary value can be used as a strategic policy lever for improved coherence and sustainability of ICT expenses. Budget thresholds can help promote a culture of cost-benefit evaluation and serve as critical policy instruments to enable leadership to ensure proper co-ordination and coherent decisions across sectors and levels of government.

Budget thresholds requiring the pre-evaluation of ICT expenditures can also help avoid overlaps of ICT investments, encourage synergies and improve co-operation among public sector organisations (e.g. demand aggregation, shared services culture). They can also help monitor and closely follow how digital governments and ICT-related priorities are being targeted by public sector organisations.

Frequently associated with the existence of budget thresholds, the mandatory use of standardised business case methodologies for ICT investments also contributes to streamlining public financial efforts in this area. Key Recommendation 9 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]) highlights the importance of this institutional policy tool to improve the planning, management and monitoring of digital technology expenditures in the public sector.

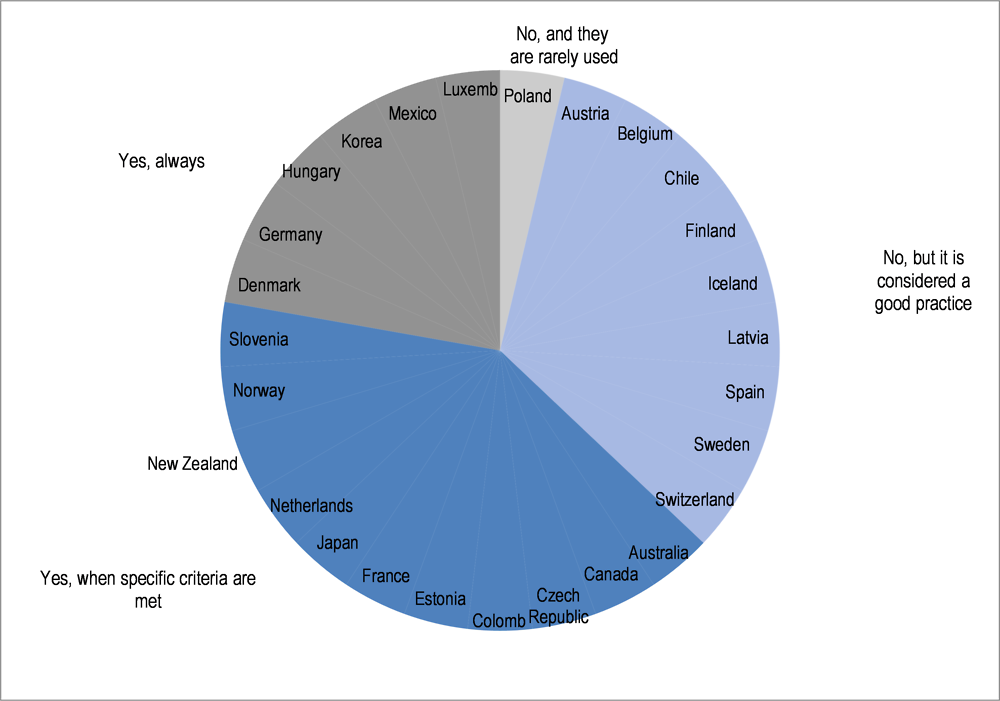

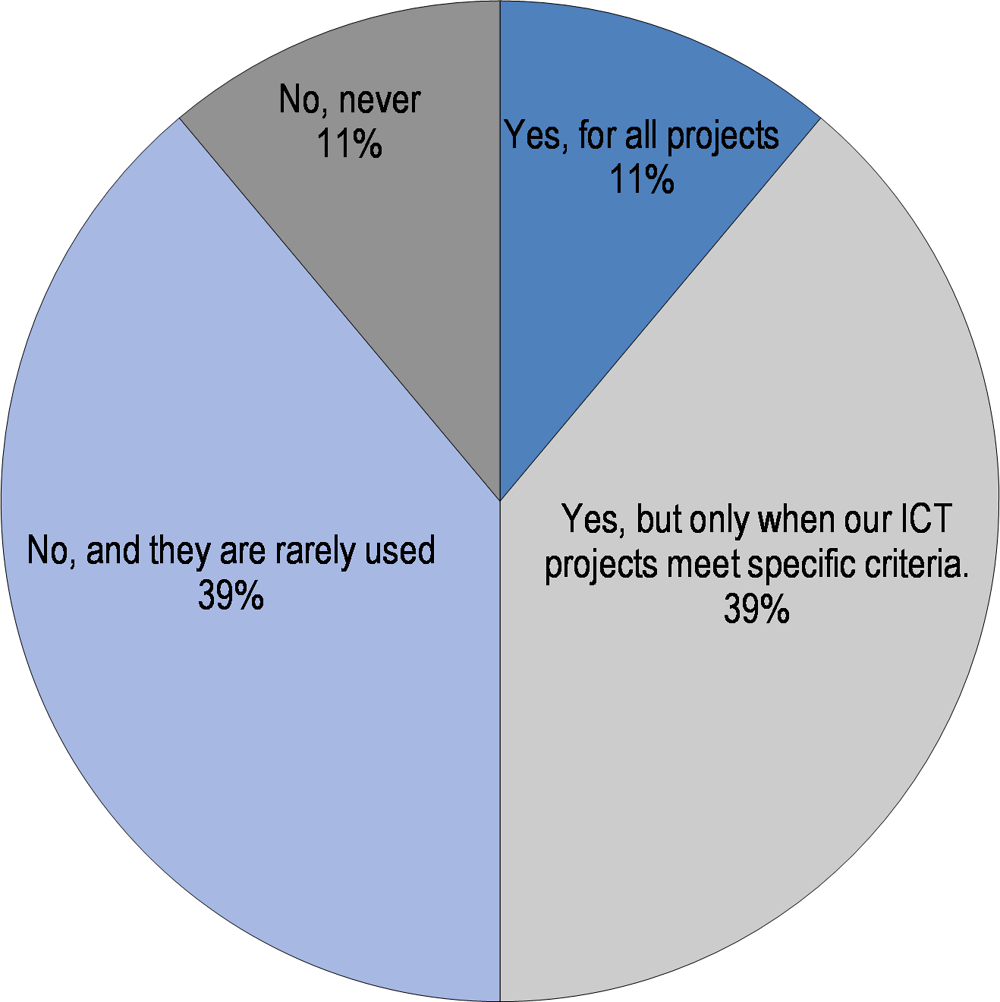

The majority of OECD countries that participated in the 2014 OECD Digital Government Performance Survey reported having mandatory business cases for ICT, whether applicable to all ICT projects or when specific criteria are met (e.g. above a certain threshold) (see Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8. Use of business cases for ICT in OECD countries

Source: OECD (2014[6]), “Survey on Digital Government Performance”, OECD, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796.

In Brazil, there isn’t an established budget threshold for ICT investments and the use of business case methods is not mandatory, even though 39% of surveyed institutions claimed they had business cases for ICT investments under certain criteria (see Figure 3.9) (OECD, 2018[12]). Nevertheless, when questioned, half of the public sector organisations that participated in the Digital Government Survey of Brazil stated that overall, they regularly use business cases or similar value proposition methods to assess ICT projects (see Figure 3.9). This reported practice reflects a significant level of maturity of the Brazilian public sector organisations when planning ICT investments.

Although a budget threshold for ICT investments is not in place and a standard and mandatory business case methodology is not currently being adopted by the Brazilian federal government, Brazil does have some general instruments of budget control and monitoring also applicable to ICT investments in place (OECD, 2018[12]):

The Secretariat of Federal Budget (Secretaria do Orçamento Federal) of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Administration is in charge of controlling the budget of the entities of the federal public administration, including the budget for ICT projects.

The Secretariat of the National Treasury (Secretaria do Tesouro Nacional) of the Ministry of Finance is in charge of defining norms related to the management of public investments, which includes the funding of ICT projects.

The Civil House of the President of the Republic is responsible for evaluating and monitoring government action as it oversees federal-level entities, including the monitoring of the execution of ICT projects.

Figure 3.9. Use of business cases in Brazil’s central government

Note: The figure shows the percentage of participating public sector organisations that responded to the question, “Does your institution regularly develop business cases or similar value proposition assessments for ICT projects?”

Source: OECD (2018[12]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Central version, unpublished.

Building on their current budget control and monitoring instruments, Brazil may wish to take example from OECD country best practices in this field as well, as presented in Box 3.2 below and Box 3.4 later in the chapter.

Box 3.2. ICT project assessment in Portugal

The Portuguese Agency for Administrative Modernisation (AMA), an executive agency located at the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, has substantive powers in terms of the allocation of financial resources and approval of ICT projects.

The AMA manages the administrative modernisation funding programme, which is composed of EU structural funds and national resources (SAMA2020). These funds are an attractive source of funding for agencies planning to develop ICT projects. This gives the agency important leverage as the approval of funding for digital government projects through this programme is conditioned on compliance with existing guidelines.

Similarly, every ICT project of EUR 10 000 or more must be pre-approved by AMA, which verifies compliance with guidelines, the non-duplication of efforts, and compares the prices and budgets with previous projects in order to ensure the best value for money.

Source: OECD (2016[20]), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

Project management standards

As previously mentioned, the coherent and sustainable implementation of digital government policies requires institutional instruments that can ensure co-ordinated public sector efforts across sectors and levels of government. Following some OECD country experiences (e.g. Denmark, Norway) (see Box 3.3) and in line with Key Recommendation 10 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]), the availability and effective use of ICT standardised project management models can strategically promote technical, financial, legal and institutional alignment across the public sector.

Standardised ICT project management methods, properly combined with the identification of budget thresholds and standardised business case methodologies (see the above section), can become strategic policy instruments to ensure alignment of initiatives with the digital government strategy and help public sector organisations to organise and administrate their projects in a more coherent and streamlined way (OECD, 2015[17]). Within agile and dynamic central monitoring platforms, project management standards can contribute to improved performance and comparability across the administration. Provided that a wide stream of management information related to project implementation is collected, transparency and accountability platforms can also be put in place to promote better knowledge exchange and peer-learning processes across the public sector, alongside with increased openness to citizens.

Box 3.3. Project Wizard in Norway

In 2016, the Norwegian government established the mandatory use of a best practice project management model for ICT projects over NOK 10 million, in order to maintain high levels of performance in the development of digital government, providing new opportunities for coherence and promoting synergies across the administration.

The Agency for Public Management and eGovernment’s (Difi) Project Wizard is the recommended (although not mandatory) project management model (http://www.prosjektveiviseren.no). Understood and conceived as a shared service, this online tool directed to project managers aims to reduce complexity and risks in public ICT projects. Based on the internationally renowned PRINCE2® (PRojects IN Controlled Environments) projection method, Project Wizard describes a set of phases that projects must go through, with specific decision points. It covers full-scale project management, including benefits’ realisation.

Although its implementation across the Norwegian public sector is still very recent, the way the platform is structured and the fact that its adoption benefits from substantial institutional support, it appears that Project Wizard has become a strategic tool to improve the development and monitoring of digital government projects across the Norwegian government.

Source: OECD (2017[19]), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

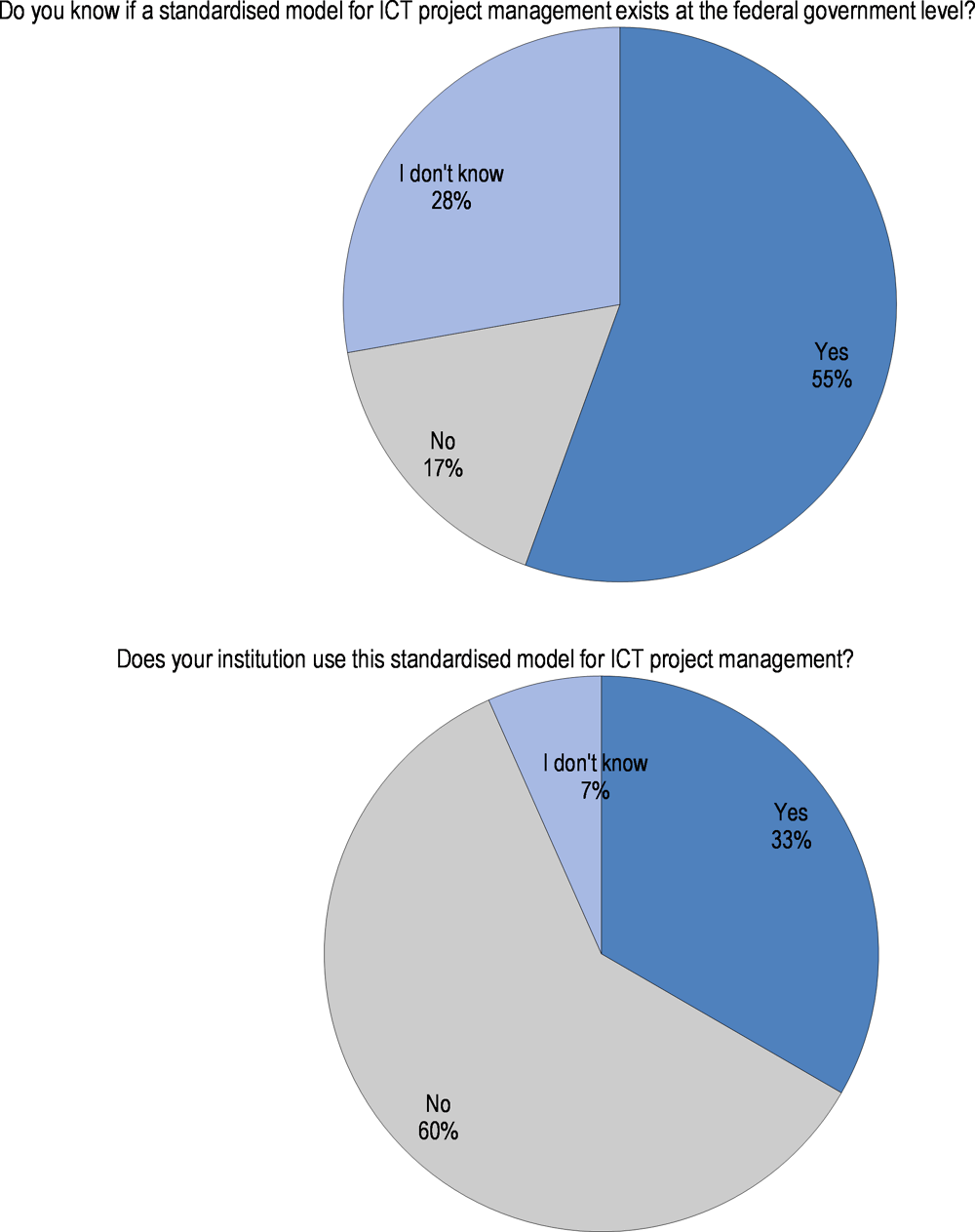

According to the 2014 OECD Digital Government Performance Survey, 59% of the respondents confirmed that they had a project management standardised model for the central government (OECD, 2014[6]), demonstrating the relevance of this kind of policy instrument for the coherence of ICT projects across the public sector.

In Brazil, although its use is not mandatory, public sector organisations are recommended to use a project management methodology. The SISP Project Management Methodology (Metodologia de Gerenciamento de Projetos do SISP, MGP-SISP) is a set of good practices and steps to be followed in the project management of ICT projects in public sector organisations. It aims to assist public organisations involved in the System for the Administration of Information Technologies Resources (Sistema de Administração dos Recursos de Tecnologia da Informação, SISP) (see Chapter 2).

Very detailed, the SISP Project Management Methodology, guides users on the steps for the correct development of IT projects and initiatives. Nevertheless, as stated in its online presentation, “the adoption of the methodology will depend on some factors, such as: reality, culture and maturity in project management, organizational structure, size of projects, etc.” In this sense, the processes and procedures described in MGP-SISP are recommended to be customised to each organisation’s situation (SISP, 2011[21]). To facilitate its use, SETIC has designed diagrams and made available a set of templates such as a demand formalisation document, a project measurement worksheet, a project opening term, a project management plan, a schedule and a risk sheet, among others (SISP, 2018[22]).

When questioned about the existence of a standardised model for ICT project management within the federal government, 55% of the Brazilian public sector organisations that participated in the Digital Government Survey responded positively. However, of those organisations, only 33% confirmed using the model, which clearly demonstrates room for improvement to better inform and involve Brazilian federal government stakeholders around the importance of having a co-ordinated project management approach (see Figure 3.10).

Management of ICT investments as a strategic policy lever

The existence of a project management methodology in Brazil, aligned with the main digital government co-ordination body ‑ System for the Administration of Information Technologies Resources (SISP) – demonstrates that important foundations are already in place to adopt a systems-thinking approach when developing ICT projects in the federal administration. The several steps for the development of an ICT project foreseen in the SISP Project Management Methodology and the available templates reflect the willingness of the Brazilian government, namely the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, to promote a strategic planning culture around ICT investments.

Yet, in line with the assessments presented in the previous sections, the Brazilian government could consider taking some additional measures to further improve the streamlining of ICT investments. In line with relevant practices in some OECD countries (e.g. Denmark, Norway, Portugal), the Brazilian government could consider establishing budget thresholds for the pre-evaluation of ICT investments at the level of federal government. The budget threshold would have to be connected with a standardised business cases methodology to facilitate and ensure the cost-benefit analysis of IT investments. This institutional co-ordination mechanism should be comprised of two distinct levels: a first level directed to projects of medium ICT budget where the pre-evaluation should be considered a best practice; a second level focused on ICT projects with a larger budget for which the pre-evaluation should be mandatory.

Figure 3.10. Existence and use of a standardised model for ICT project management in the Brazilian public sector

Source: OECD (2018[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

The establishment of a budget threshold should also be considered as an opportunity to properly update the SISP Project Management Methodology, namely ensuring:

the involvement of the digital government stakeholders, promoting co-ownership and shared responsibility in the design of the new methodology

alignment with the objectives and priorities of the Digital Governance Strategy (EGD)

synchronisation with legal, institutional and technical guidelines and requirements (e.g. interoperability, digital identity, open government data, data protection)

a web-based platform where federal public sector organisations could manage their projects according to simple and standard requirements and guidelines.

The Brazilian government could also consider establishing co-funding mechanisms for ICT projects to enable prioritisation and coherence of efforts and investments made by the federal government (see Box 3.4). This kind of policy tool would function as an important incentive for an effective and co-ordinated implementation of the digital government strategy.

Box 3.4. Developing the strategic assessments in New Zealand’s Better Business Cases Methodology

New Zealand has developed a robust and structured approach to the development of business cases for large public investments. The strategic assessment of the typical investment project follows the following steps:

1. Initiate the investment proposal and appoint the senior responsible owner to take the leadership role in the development of the strategic assessment.

2. Identify key stakeholders, analyse their interest and influence, and complete a stakeholder management plan. This will inform the choice of attendees for the initial stakeholder workshops required to identify investment drivers.

3. Describe the proposal and draft the strategic context. Use this as the basis for briefing workshop attendees.

4. Arrange facilitated workshops with key stakeholders to identify and agree on investment drivers (problems/opportunities).

5. Finalise the workshop outputs and draft the strategic assessment document.

6. Present the final draft strategic assessment (and any supporting documentation required) for review, including a Gateway Review Panel where required. Incorporate feedback.

7. Finalise the strategic assessment, seek final signature.

Source: Treasury of New Zealand (2015[23]), “Better Business Cases: Guide to Developing the Strategic Assessment”.

The suggested establishment of a budget threshold, the development of a standardised business case methodology and the update of the standard project management methodology would help improve co-ordination and coherence across the different policy sectors, and contribute to reinforcing the leadership and co-ordination capacity of the Secretariat of Information Technology (SETIC) of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management. The attribution of the responsibilities for the development and management of the above-mentioned policy tools to SETIC would set important and useful conditions for reinforced and co-ordinated implementation of the country’s digital government strategy.

From ICT procurement to digital commissioning

Better procurement for better government

In line with the recognised importance of better planning ICT investments in the public sector, ICT procurement is a critical element for the coherent and sustainable development of digital government. Key Recommendation 11 of the OECD Recommendation on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[2]) underscores the importance of this policy dimension to better sustain overall objectives for the modernisation of the public administration.

The benefits of a strategic and co-ordinated approach to ICT procurement are very diverse:

Through demand aggregation and framework agreements, important efficiencies can be obtained in ICT investments.

There can be reinforced alignment of ICT investments with the digital government strategy, namely by enforcing overall objectives, technical standards and guidelines (e.g. digital identity, interoperability, open standards).

Improved oversight capacities can help avoid gaps and overlaps of ICT acquisitions.

There can be strengthened capacity to monitor and access the impacts of ICT investments made across the public sector.

There can be enhanced conditions to increase the transparency and accountability of ICT investments through the possible publication of structured information and data on public tenders and on the entire procurement process.

New topics such as data ownership and sovereignty or transition from legacy systems pressure public sectors around the world to respond to the new demands of the digital economy. Given the rapid development, diversity of trends and the high complexity of digital technologies nowadays, governments face the challenge of ensuring agility and adaptability within their regulatory procurement frameworks.

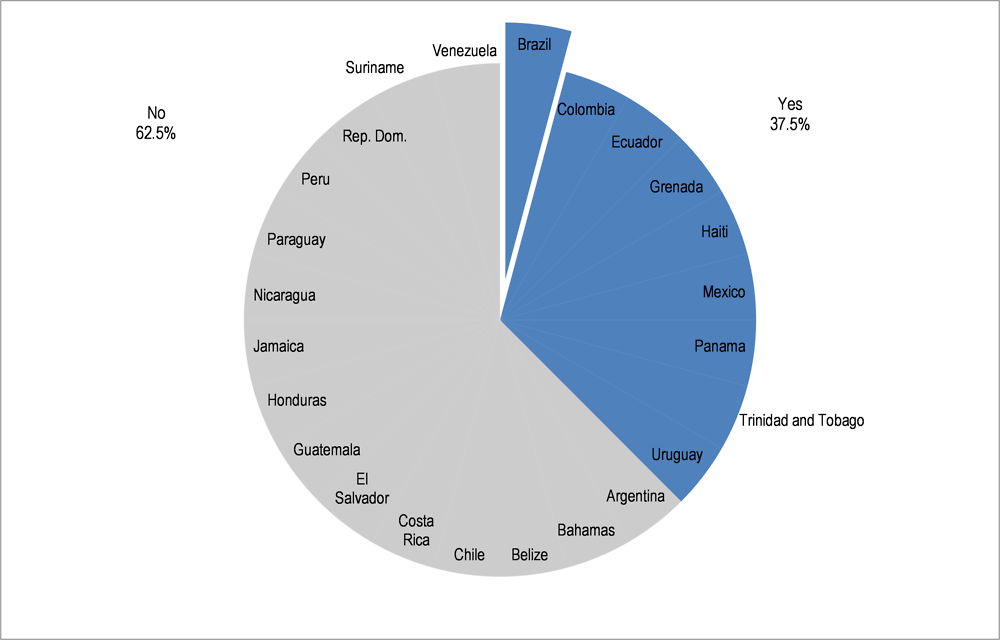

According to the OECD Digital Government Performance Survey, 52% of OECD countries have an ICT procurement strategy applicable to the central government (OECD, 2014[6]). Although that percentage decreases when analysed in the Latin America and Caribbean context, where 37% of countries report having such a strategy (Figure 3.11), it reflects a substantial commitment of the governments of the region to use ICT procurement as a relevant mechanism for the implementation of digital government policies.

Figure 3.11. Existence of an ICT procurement strategy in LAC countries

Source: OECD (2016[18]), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

Efforts underway for co-ordinated ICT procurement

Brazil has an ICT procurement strategy for the whole federal government. The strategy is defined by a regulation approved in 2008 (IN no. 4/2008) and is updated periodically that normalises the processes of acquisition of ICT solutions by all the members of the System for the Administration of Information Technologies Resources (SISP) (Secretaria de Logística e Tecnologia da Informação, 2014[24]). The regulation determines the main stages of the procurement process (e.g. planning, selection of the supplier, contract management) and details the mandatory procedures to be followed in each one of the procurement phases.

According to the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, the strategy is mainly focused on efficiency gains through the use of standardised solutions. Demand aggregation is also one of the priorities, together with the use of off-the-shelf solutions, as opposed to the development of in-house solutions or outsourcing new development. The strategy also prioritises the acquisition of solutions to small- and medium-sized enterprises (OECD, 2018[12]).

In line with the priority attributed to demand aggregation and shared services approaches, the Secretariat of Information Technology (SETIC), in partnership with the Procurement Unit of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management, centralises the procurement process of some services that are of mutual use to the many federal-level institutions, such as telecommunications services, network equipment, personal computers, security equipment or cloud storage (OECD, 2018[12]).

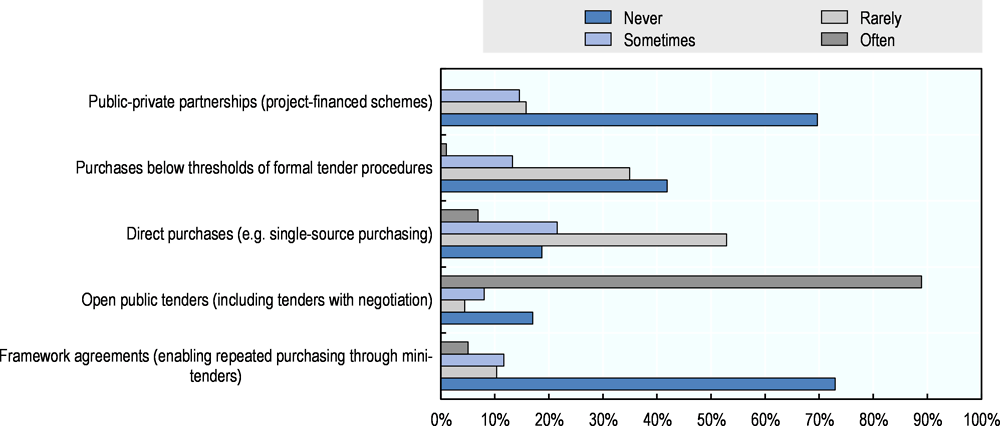

When questioned about the main methods used to procure ICT goods and services, the public sector organisations that participated in the Digital Government Survey of Brazil reported using open public tenders (including tenders with negotiation) the most (see Figure 3.12), reflecting strong compliance with the regulations in place.

Figure 3.12. ICT procurement methods used in the federal government of Brazil

Source: OECD (2018[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Brazil”, Public sector organisations version, unpublished.

Although the Brazilian public sector context benefits from clear and specific regulations on ICT procurement, public stakeholders interviewed during the OECD fact-finding mission to Brasilia in July 2017 and the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management agree that the strong focus of the current framework on efficiency limits the public sector’s capacity to innovate and disrupt existing practices and forms of collaboration. The strict configuration of the current regulation to prioritise options based on the “lowest price” criteria limits the willingness of public institutions to assume the risks of procurement processes focused on innovation (OECD, 2018[12]). Recently, providing for more simplified means of purchasing technology, there has been significant progress in this area with the new Innovation Legal Framework. The Federal Decree no. 9,283/2018, which regulates Law no.. 10,973/2004, acknowledges the inherent risks in the procurement of innovative goods and services while providing simpler and more streamlined instruments of procurement and partnership in such cases.

In order to promote openness and accountability in federal government public procurement, the Secretariat of Management of the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management (SEGES) is responsible for a repository of contracts in the public sector ‑ the Procurement Panel of the Federal Government. Although the platform is not focused specifically on ICT contracts, it provides relevant information about ICT procurement dynamics in Brazil (e.g. main services procured, main providers). However, a federal database presenting previous ICT contractors’ performance evaluations is not available as a reference for future ICT procurement decisions (OECD, 2018[12]).

Additionally, in order to better monitor ICT spending in the public sector, the Comptroller General of the Union launched in 2017 an online interactive dashboard on ICT Spending (Painel Gastos de TI). The online tool allows the user to access information on IT expenses in the federal government, presenting the budgets, previous procurement processes and the corresponding costs. Given its interactive functionalities, the user can use different indicators and filters to compare the expenses of several federal government units. The initiative is an important practice that reflects the Brazilian government’s commitment to transparency in ICT spending through openness and integrity-driven policies.

The role of public IT companies

One of the particularities of the Brazilian public sector IT context is the existence of two state-owned companies that assume a pre-eminent role in the provision of IT services to the public administration: Serpro and Dataprev. According to the Digital Government Survey of Brazil, almost 60% of the purchases of IT services at the federal level are supplied by these state-owned companies, through direct purchase (OECD, 2018[12]).

Serpro (Serviço Federal de Processamento de Dados), created in 1964, and Dataprev (Empresa de Tecnologia e Informações da Previdência Social), created in 1974, are independent state companies. They have a certain amount of autonomy that keeps them at arm's length from any ministry in the federal government. However, the Ministry of Finance, under the terms of Article 20 and 27 of the Law Decree no.. 200 supervises the operations of both companies. Both companies were founded with the purpose of supporting the IT operations of the ministries, but their roles have evolved significantly during past decades. Currently both provide a wide variety of services (e.g. software development, data hosting, operation and support, consultancy and business intelligence) to public institutions across different sectors and levels of government.

Besides providing general ICT services, both companies maintain in their portfolio of operations the management of important public base registers, acting as service providers of different ministries. For instance, Serpro manages several critical taxes and justice registers, and Dataprev is responsible for social security registers. On the other hand, due to their state-owned status, both companies benefit from special public procurement rules that allow public entities to easily contract their services.

The existence of two public companies with the primary mission of providing services to the public sector can bring several advantages to the country’s digital government development process. ICT goods and services are developed and delivered based on the public sector’s specificities and requirements. This has eventually allowed the government to strategically gear both companies’ efforts towards specific goals and demands of the public modernisation agenda. However, the combination of beneficial procurement rules, management of critical base registers and management of structural public ICT legacy systems puts Serpro and Dataprev in a very privileged position with regard to the larger Brazilian ICT market that delivers goods and services to the public sector.

During the OECD fact-finding mission organised in Brasilia in July 2017, several public sector stakeholders raised very concrete concerns about inefficiencies caused by the Brazilian current model of ICT services provision where Serpro and Dataprev have a dominant position. The problems identified by the ecosystem of stakeholders are aligned with the results of the recent inspection of the Brazilian Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União) (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2018[25]). The following critical aspects were identified with regard to the activities of both companies:

1. low levels of efficiency, with ongoing difficulties responding to services’ requests

2. non-transparent and non-competitive prices when considering similar offers available in the market

3. low levels of service satisfaction reported by clients

4. a critical financial situation that required the recent injection of public capital to face sustainability problems (applicable only to Serpro).

Evidence and insights gathered as part of this review seem to point to the fact that both companies also have room for improvement in the use of open source solutions and to reduce vendor-locked situations.

In order to reverse this critical situation, the Federal Court of Accounts recommended that both companies adjust their business models to become more competitive and thus secure efficiency gains to their public sector contractors.

The dominant role played by Serpro and Dataprev in the delivery of IT services to the public sector is not common in OECD country contexts, where free market approaches are conciliated with the provision of shared services by public institutions with associated business models. Although the Brazilian model of two dominant public companies should in principle not be considered problematic for the development of digital government in the country, its maintenance can only be justifiable if Serpro and Dataprev clearly demonstrate their added value. In this sense, both companies should prioritise addressing the four problems identified by the recent report of the Brazilian Federal Court of Accounts and increase the use of open source solutions to address the identified vendor-locked situations.

ICT commissioning as an opportunity

As previously mentioned, the increasing complexity of ICT investments requires agile ICT procurement frameworks capable of responding to governments’ specific needs. New digital trends challenge public sectors to consider several cost structures (e.g. specialised human resources, specific hardware and software, usability and security) and diverse variables (e.g. sector of government to be applied, national and international regulations). Additional uncertainties such as dominant standards, vendor-locked concerns, data ownership and sovereignty, are adding extra density to already complex contexts. Last but not least, citizens’ rising expectations with regard to efficiency, openness and collaboration create a particularly demanding test to governments’ delivery capacities.

Although value for money, integrity and accountability are still fundamental requirements for public procurement, new acquisition approaches are being increasingly required to allow private contractors to partner in developing solutions and services that create public value, as per the principles of the 2015 OECD Council Recommendation on Public Procurement (OECD, 2015[17]). In this context, public sectors are increasingly required to embrace more agile techniques, involving providers and stakeholders earlier in the commissioning process and iteratively throughout delivery, in order to better understand user needs and contexts, and potential benefits and barriers, and to adjust constantly in order to develop more agile solutions to realise benefits. Governments across the OECD are developing and testing new approaches embedded with an ICT commissioning rational of goods and services (see Box 3.5). A shift from closed and strict procurement approaches to commissioning, and collaboration-oriented imperatives, are increasingly perceived as key by the governments of OECD countries and partner economies.2

Box 3.5. The United Kingdom’s Digital Marketplace

Developed by the Government Digital Service, the United Kingdom’s agency responsible for leading digital government policies, the Digital Marketplace is a portal where public sector organisations can find people and technology for digital projects. Three kinds of agreements are available between government and suppliers:

1. Cloud services: Around 20 000 cloud services on the Digital Marketplace through the G-Cloud framework (cloud hosting, cloud software and cloud support).

2. Digital specialist services: More than 1 000 suppliers provide digital specialist services, including digital outcomes (e.g. booking system or an accessibility audit), digital specialists (e.g. product managers or developers), user research studios, user research participants and data centre hosting services.

3. Data centre hosting services: One supplier provides data centre hosting to the government. It offers namely a flexible, pay-for-what-you-use model, and ensures facilities and leading environmental performance.

The Digital Marketplace is considered today a reference due to the amount of government frameworks agreements, making the buying of services faster and cheaper than entering into individual procurement contracts.

Source: GOV.UK (2017[26]), “Digital Marketplace”, webpage, www.digitalmarketplace.service.gov.uk.

Given the previously identified need to update and improve the country’s ICT public procurement framework, the Brazilian government could consider embedding this commissioning mindset in future reforms, as doing so could help spur more innovative and strategic practices and approaches for the identification of collaboration and solutions that best respond to the needs of the public sector. In addition, understanding user needs as a basis for designing procurements and contracts should be incorporated into procurement regulations. For that, the involvement of the providers should be considered throughout the entire procurement lifecycle.

References

[7] CETIC - Brazilian Internet Steering Committee (2017), ICT Electronic Government 2017 - Survey on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in the Brazilian Public Sector, http://cetic.br/publicacao/pesquisa-sobre-o-uso-das-tecnologias-de-informacao-e-comunicacao-tic-governo-eletronico-2017/ (accessed on 22 July 2018).

[16] GDS (2018), GDS Academy, https://gdsacademy.campaign.gov.uk/ (accessed on 20 July 2018).

[26] GOV.UK (2017), Digital Marketplace, http://www.digitalmarketplace.service.gov.uk.

[15] GOV.UK (2017), Digital, Data and Technology Profession Capability Framework, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/digital-data-and-technology-profession-capability-framework (accessed on 20 July 2018).

[13] Ministério do Planejamento, Desenvolvimento e Gestão (2018), Analista em Tecnologia da Informação (ATI), https://www.governodigital.gov.br/transformacao/sisp/nucleo-de-gestao-de-pessoas/analista-em-tecnologia-da-informacao-ati (accessed on 22 July 2018).

[8] Ministério do Planejamento, D. (2018), Estratégia de Governança Digital (EGD) — Versão Revisitada, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/EGD (accessed on 15 July 2018).

[10] Ministério do Planejamento, D.((n.d.)), Programa de Aperfeiçoamento dos servidores de TIC — Governo Digital, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/transformacao/sisp/nucleo-de-gestao-de-pessoas/plano-de-gestao-de-pessoas (accessed on 22 July 2018).

[12] OECD (2018), Digital Government Survey of Brazil, Central version.

[9] OECD (2018), Digital Government Survey of Brazil, Public sector organisations version.

[27] OECD (2017), “Core Skills for Public Sector Innovation”, https://www.oecd.org/media/oecdorg/satellitesites/opsi/contents/files/OECD_OPSI-core_skills_for_public_sector_innovation-201704.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2018).

[19] OECD (2017), Digital Government Review of Norway: Boosting the Digital Transformation of the Public Sector, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264279742-en.

[28] OECD (2017), Innovation Skills in the Public Sector: Building Capabilities in Chile, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273283-en.

[3] OECD (2017), OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276284-en.

[20] OECD (2016), Digital Government in Chile: Strengthening the Institutional and Governance Framework, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258013-en.

[18] OECD (2016), Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265554-en.

[17] OECD (2015), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/OECD-Recommendation-on-Public-Procurement.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2018).

[2] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/Recommendation-digital-government-strategies.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2018).

[5] OECD (2014), Survey on Digital Government Performance, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796 (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[6] OECD (2014), Survey on Digital Government Performance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=6C3F11AF-875E-4469-9C9E-AF93EE384796 (accessed on 16 July 2018).

[14] OECD (2010), OECD Reviews of Human Resource Management in Government: Brazil 2010: Federal Government, OECD Reviews of Human Resource Management in Government, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264082229-en.

[1] OECD (forthcoming), Creating a Citizen-Driven Environment through Good ICT Governance – The Digital Transformation of the Public Sector: Helping Governments Respond to the Needs of Networked Societies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[4] OECD (forthcoming), Review of the Innovation Skills and Leadership in Brazil’s Senior Civil Service, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[24] Secretaria de Logística e Tecnologia da Informação (2014), Instrução Normativa n. 4, de 11 de Setembro de 2014, https://www.governodigital.gov.br/documentos-e-arquivos/legislacao/1%20-%20IN%204%20%2011-9-14.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2018).

[22] SISP (2018), MGP-SISP - Artefactos, http://www.sisp.gov.br/mgpsisp/wiki/Artefatos (accessed on 23 July 2018).

[11] SISP (2018), Programa de Aperfeiçoamento dos Servidores de Tecnologia da Informação e Comunicação - PROATI, http://www.sisp.gov.br/gestaodepessoas/wiki/aperfeicoamento (accessed on 22 July 2018).

[21] SISP (2011), Metodologia de Gerenciamento de Projectos do SISP, http://www.sisp.gov.br/mgpsisp/wiki/download/file/MGP-SISP_Versao_1.0.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2018).

[23] Treasury of New Zealand (2015), Better Business Cases: Guide to Developing the Strategic Assessment.

[25] Tribunal de Contas da União (2018), Serpro e Dataprev possuem baixos índices de eficiência, constata TCU, https://portal.tcu.gov.br/imprensa/noticias/serpro-e-dataprev-possuem-baixos-indices-de-eficiencia-constata-tcu.htm (accessed on 24 July 2018).

Notes

← 1. Information provided by the Ministry of Planning, Development and Management.

← 2. An OECD E-Leaders Thematic Group co-ordinated by the United Kingdom and gathers representatives of several countries (e.g. Australia, Canada, New Zealand) is currently developing a Playbook for ICT Procurement Reform. The document is closely based on the ICT commissioning rational. Building on the experience of the countries involved in the thematic group, the playbook will present several principles and lines of action to be followed for improved procurement processes.