Maintaining and developing the skills of workers throughout their working lives is essential to ensure they continue to have good employment opportunities at an older age. For Japan, the challenge is two-fold. First, its system of continuous vocational training needs to be strengthened to ensure workers can use and upgrade their competencies and skills throughout their careers. Second, employment services and active labour market policies will need to play a more important role in helping workers to make successful employment transitions, especially after retiring from their main jobs.

Working Better with Age: Japan

Chapter 3. Skills development and activation in Japan

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Japan needs to promote training throughout working lives

The skills of older workers and how they are utilised are key determinants for the productivity of workers and companies. This section gives an overview of the skills of older workers. Several factors determine how skills evolve over the life cycle. A key determinant is the skills obtained at a younger age through education and training as well as those skills acquired through participation in further training. The learning content of jobs also has an important impact on skills development over the life cycle. Some skills are likely to decline over age, although experience may compensate for this decline.

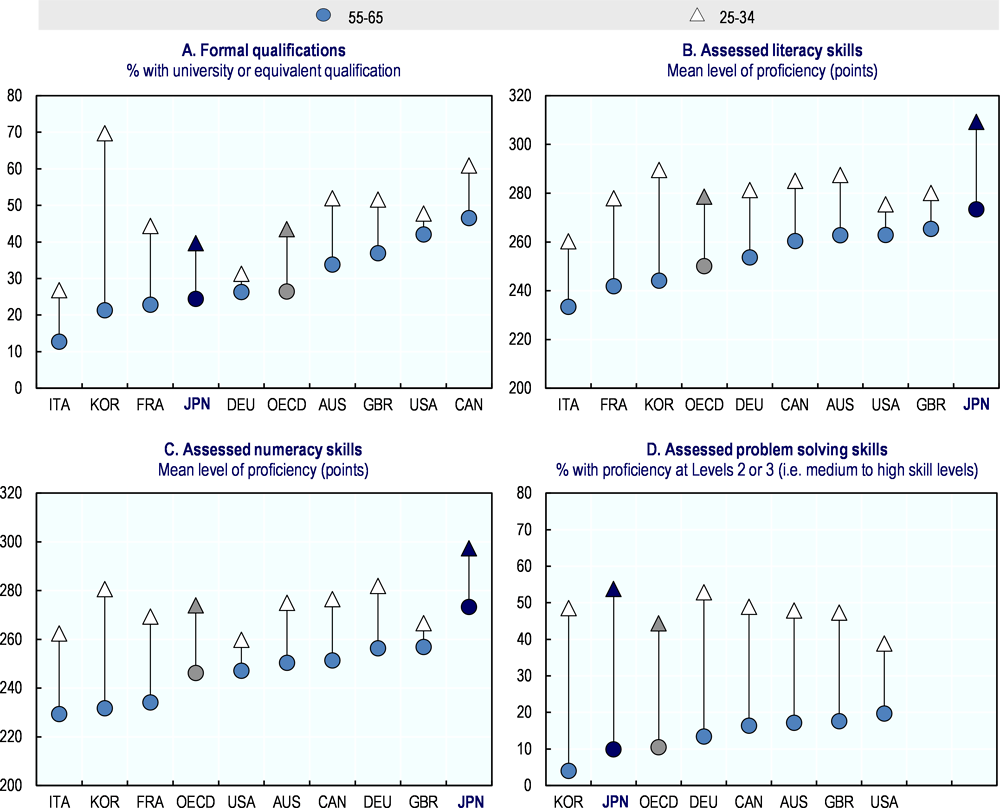

The skills of older people in Japan will rise over the next 30 years but need to be strengthened in some dimensions

A proxy measure of the level of skills that people have is their level of educational attainment. A higher level of educational attainment generally implies a higher level of skills. Currently, many older Japanese have no formal qualifications above a high-school level. The proportion of older people in Japan aged 55-64 who have a university-level (tertiary) qualification is slightly below the OECD average and well below the proportion in Canada and the Unites States (Figure 3.1, Panel A). This is also true for younger Japanese people even though educational attainment has been rising for successive generations of Japanese. Therefore, in 30 years time, the propoprtion of older people in Japan with a university-level qualification will be higher than today but it is likely to remain below the OECD average and well below the level in Korea.

In contrast to their formal qualifications, results from the OECD’s Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) suggest that Japanese adults have strong foundation skills in terms of literacy and numeracy relative to adults in other large OECD economies (Panels B and C). This is true for both younger and older people in Japan, so that older people in Japan are likely to continue to enjoy this comparative advantage for at least the next 30 years. However, in terms of problem-solving skills in a technology-rich environment (i.e. solving problems in a simulated internet environment), relatively few older Japanese were assessed as having medium to good skills (Panel D). This could put them at a disadvantage in the context of rapid change in Information and Communication Technology (ICT). Nevertheless, the proportion of younger Japanese with medium-to-good skills in problem solving in a technology-rich environment was assessed to be high relative to other large OECD economies. Therefore, tomorrow’s generation of older workers are likely to be better prepared for the digital economy than the current generation.

Figure 3.1. Skill levels of older (55-65) and younger (25-34) people

Note: In Panel A, the older age group refers to people aged 55-64 not 55-65; for Panel D, the data refer to problem solving skills in a technology-rich environment. The OECD average excludes Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Mexico, Portugal and Switzerland. Data for the United Kingdom refers to England.

Source: Panel A: OECD Dataset on Educational Attainment and Labour Force Status, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=76794 and the Japanese Labour Force Survey; Panels B-D: Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

With advances in technology and automation, jobs and activities outside of work increasingly involve sophisticated tasks, require analysing and communicating information. Hence, poor proficiency in information-processing skills not only restrains employment opportunities but also limits access to many services. More than ever, lifelong learning is of key importance, for all workers in all kinds of jobs. Workers in low‑technology sectors and those performing low‑skilled tasks must learn to be adaptable, because they are at higher risk of losing their job, as routine tasks are increasingly performed by machines, and companies may relocate to countries with lower labour costs. In high-technology sectors, workers need to update their competencies and keep pace with rapidly changing techniques. The job prospects of older workers will be increasingly dependent on the skills they have acquired and kept up to date over their careers.

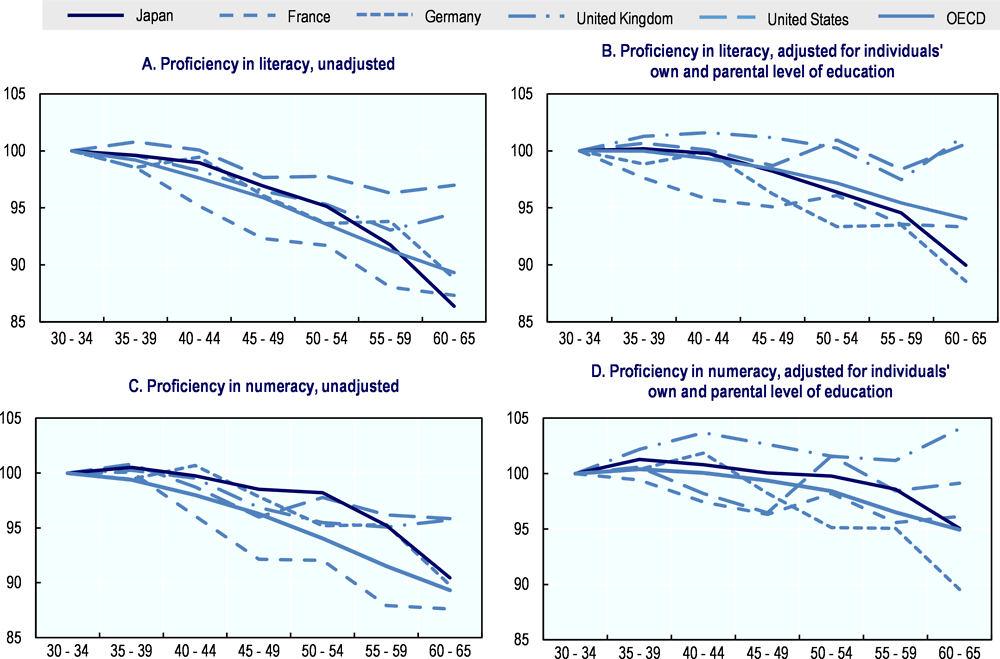

Skills levels decline steeply at older ages in Japan

In all countries there is some evidence of a decline in cognitive skills by age. However, the decline in both literacy and numeracy proficiency scores appears to be steeper in Japan than in some other OECD countries even when controlling for differences across age cohorts in individuals’ own and parental level of education (Figure 3.2). This could adversely affect the ability of some older workers to learn new things. It may also point to issues of a lack of learning opportunities both on and off the job at younger ages.

Figure 3.2. Literacy and numeracy skills of Japanese decline steeply at older ages

Note: The OECD is a weighted average and excludes Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Mexico, Portugal and Switzerland. Data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland. For Panels B and D, the estimated levels of proficiency control for individual differences in own and parental educational attainment.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

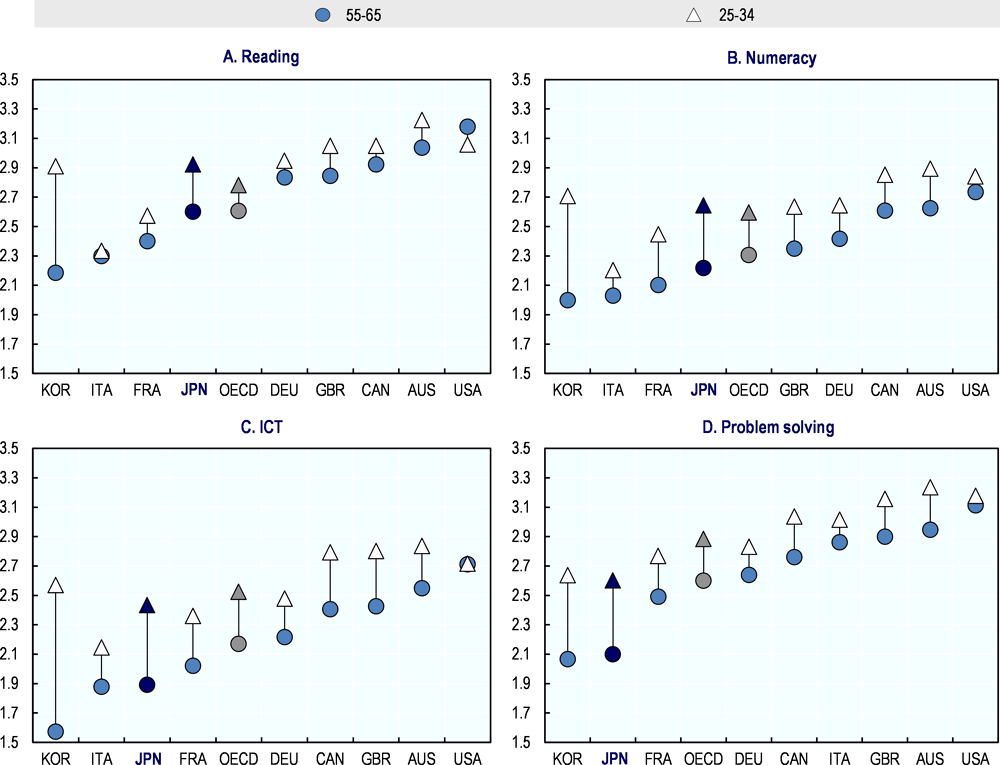

Skills of Japanese workers are underutilised

Making good use of the skills that workers have not only improves their productivity but can also help to prevent a depreciation of these skills with age. However, the PIAAC data on skill proficiency and skill use at work suggests that the skills of both younger and older Japanese workers are not fully utilised (Figure 3.3). While they have relatively high numeracy and literacy skills, this does not translate into higher use of these skills at work in comparison with other major OECD economies. For example, the literacy proficiency of older people in Japan is considerably higher than in the United States (Figure 3.1, Panel B) but the use of reading skills at work (i.e. the frequency of performing various tasks involving reading) by older Japanese workers is lower than for older American workers (Figure 3.3, Panel A).

The PIAAC data also suggest that the use of ICT and problem-solving skills by older workers is particularly weak in Japan (Figure 3.3, Panels C and D). The comparative situation of prime-age workers (aged 25-54) in Japan is not much better, although they record higher skill use on average than older workers, as in other countries. This suggests that Japanese workers of all ages will need to be better prepared for an increasingly digitalised economy.

The gap in skill use between prime-age workers and older workers is large in Japan relative to most other large OECD economies, with the notable exception of Korea. This gap remains even when controlling for differences in education and skill proficiency. It is also not accounted for by the more intensive use of other skills by older Japanese workers. As discussed in Chapter 4 (see Figure 4.6), there is also a large drop-off after the age of 60 in the use of supervising, planning and influencing skills. One explanation for this is that Japanese older workers move into less demanding positions prior to retirement (see Chapter 2). Another reason is that they do not get sufficient further training over the life course.

High-performance work practices can boost skill use and promote training

Not fully utilising the skills that workers have represents a loss of learning opportunities as well as a loss of potential productivity gains. Research points to the impact of work organisation on the learning potential of the workplace (for a literature review see e.g. (Vaughan, 2008[1])). High-performance work practices (e.g. the use of teamwork, performance pay, etc.) contribute to higher skills use at work (OECD, 2016[2]) and promote workplace learning (Ashton, 2002[3]).

Multi-skilling and the use of self-managed work groups have a positive impact on workplace related learning (Cedefop, 2010[4]) Furthermore, the learning environment varies with the type of tasks and with the type of work organisation (see e.g. (Ashton, 2002[3])). Basically, it is argued that “tayloristic” forms of work organisation diminish the learning capacities of workers and offer few learning opportunities. The opposite occurs when workers have greater autonomy and are able to concentrate. Research in the area of industrial sociology and training further shows that workplace-based learning and learning on the job contribute importantly to the skills of workers (Meil, Heidling and Rose, 2004[5]).

Based on the results of the PIAAC survey, it was estimated that only about 25% of workers in Japan were employed in jobs involving high-performance work practices compared with almost 30% in the United States and close to 40% in Sweden (OECD, 2016[2]). Therefore, there is scope in Japan through changes in work organisation to foster greater skill use of workers and better learning opportunities. This would help older workers ensure they have the skills required by employers and can more fully use these skills. A range of country initiatives to promote the development of high-performance work practices is summarised in (OECD, 2016[2]).

Figure 3.3. Skill use at work by older (55-65) and prime-age (25-54) workers

Note: In Panel A, the older age group refers to people aged 55-64 not 55-65; Panel D: the data refer to problem solving skills in a technology-rich environment. The OECD average excludes Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Mexico, Portugal and Switzerland. Data for the United Kingdom refer to England.

Source: Panel A: OECD Dataset on Educational Attainment and Labour Force Status, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=76794 and the Japanese Labour Force Survey; Panels B-D: Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

Participation of workers in training at mid-career and older ages is low in Japan

The job prospects of older workers not only depend on the skills they have acquired early on in their lives but also on the extent to which they have kept these skills up to date over their careers. A well-functioning system of lifelong learning helps workers to adjust to changes in the labour market and contributes to the productivity of firms. This is becoming increasingly important in the context of the rapid digitalisation of the economy and longer working lives over which workers may have to change jobs more frequently.

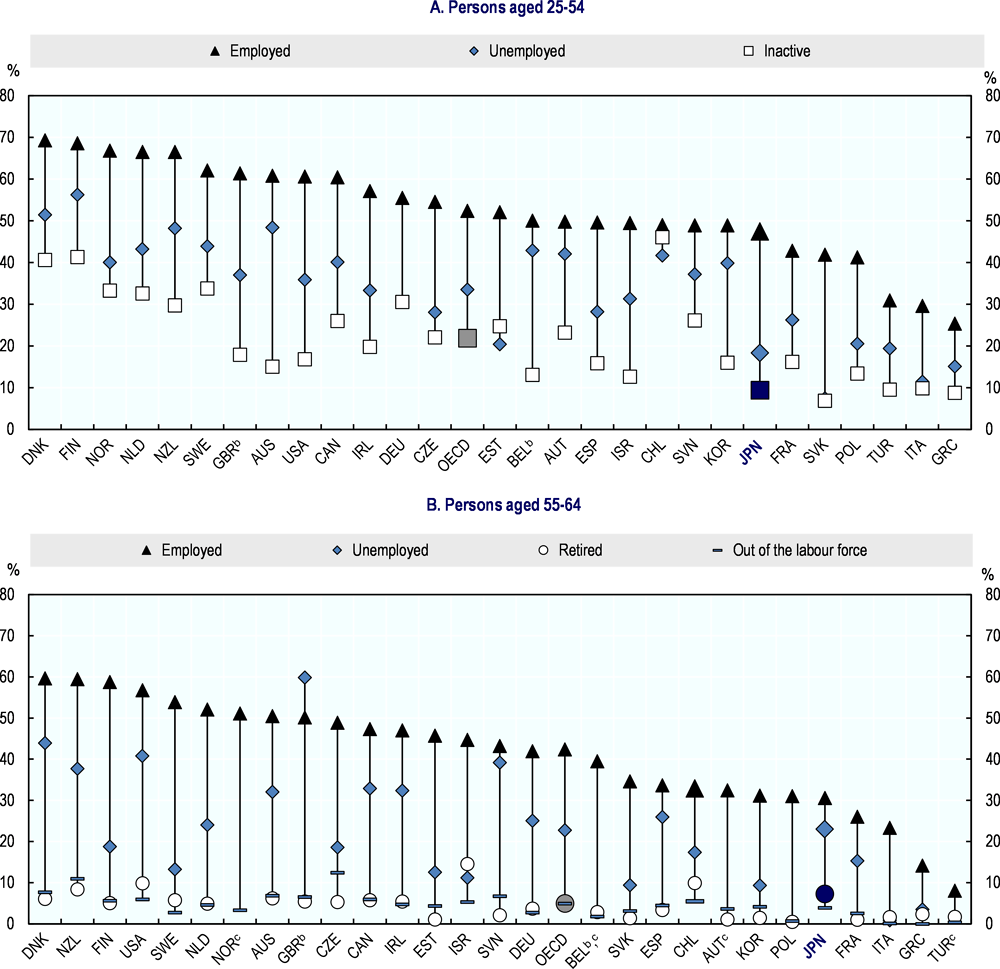

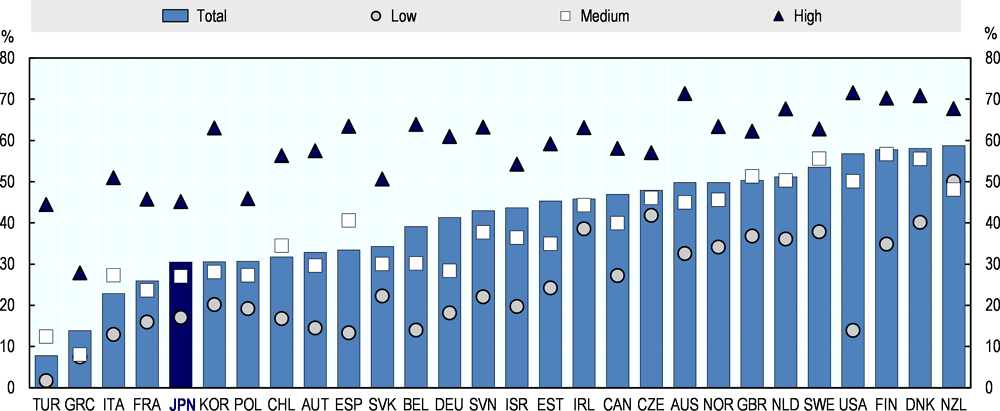

The evidence on training participation suggests that Japan’s system of lifelong learning is less well developed than in many other OECD countries, especially with respect to off‑the‑job training (OFF-JT). In Japan, the participation of both prime-age and older workers in job-related training is among the lowest among OECD countries which participated in the PIAAC survey (Figure 3.4). Japan obtains a middle ranking in the case of older unemployed but remains close to the bottom for inactive prime-age persons.

Figure 3.4. Participation in job-related training is higher for employed than for unemployed and decreases with age

Note: The OECD is an unweighted average.

a. Year 2015 for Chile, Greece, Israel, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey; for all other countries, 2012.

b. Data for Belgium refer only to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland jointly.

c. No estimates of participation in training for the unemployed aged 55-64 are shown because there are not enough observations to generate reliable estimates.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

Data on investment in training also suggests that Japan invests less than some other countries. In 2010, the investment in human capital made by Japanese companies was considerably lower than in Germany and the United States (MHLW, 2015[6]). Investments made by firms in off-the-job training (OFF-JT) have dropped sharply in Japan over time as the share of non‑regular workers in total employment has risen.1

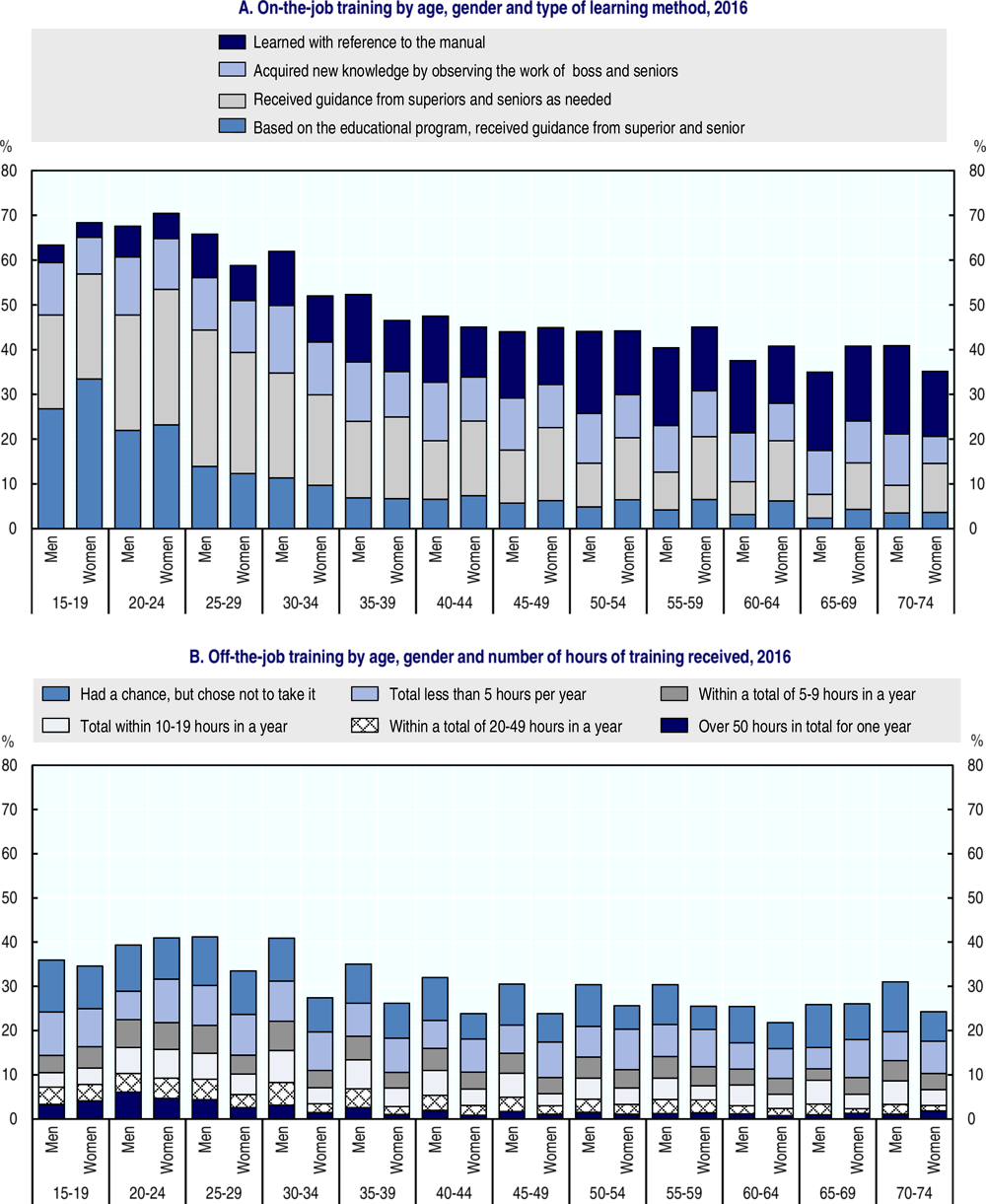

Older women are receiving more often on-the-job training and less often off‑the‑job training than men

A key feature of Japan’s training system still consists in the predominance of on-the-job training (OJT), mainly for young people, which is provided in-house in large companies. The system gives flexibility for mobility of regular workers within large firms, mainly in the first half of their careers, but not between firms as it is difficult for workers to obtain recognition of the skills they have acquired through this informal type of learning.

A closer look at participation in training by age, gender and type of training received in Japan shows that older women aged 55-69 are more likely than older men to participate in on-the-job training. After age 35 participation in OJT decreases markedly for both men and women, which can be a result of the fact that workers have already learnt much of what they need to know for their jobs (Figure 3.5, Panel A). After the age of 40, participation in OJT declines more for men than for women. One reason for the relatively higher participation of women than men in training at mid‑career and older ages may be linked to return to work after child-rearing breaks. The type of learning method also varies by age and gender. Older workers tend to learn more often while using a manual than younger ones. Older women more often receive guidance from superiors and seniors, while older men tend to learn more often by observing the work of boss and seniors.

The Basic Survey of Human Resources Development 2015 asks firms about what kind of agencies are used to provide OFF-JT for their employees. The result (based on multiple‑answer) shows that most of OFF-JT for regular workers2 is provided by firms themselves (75.0%). This is followed by private educational training facilities (46.0%), affiliated companies (26.6%), public vocational training facilities (5.2%) and technical college and university (1.9%).

Figure 3.5. Participation in on-the-job and off-the-job training decreases with age

Source: Japanese Panel Study of Employment Dynamics (JPSED) provided by the Recruit Works Institute for Japan.

Non-regular workers receive less training

As in other OECD countries, non-regular workers are less likely to receive employer‑sponsored training than regular workers. However, data from the Basic Survey of Human Resources Development in FY 2015 show that the gap in training is substantial in Japan. The proportion of companies providing on-the-job trainng (OJT) for regular employees was 62%, and for non-regular employees it was 31%. The share of companies providing OFF-JT for regular employees was to 72%, while the corresponding share for non-regular workers was 34% (JILPT, 2017[7]). Thereare several possible reasons for this. First, the expected rate of return to training may be lower for non-regular workers relative to regular workers because they are expected to remain less time in the company. Second, non‑regular workers are more concentrated in sectors which have lower than average rates of training. Third, company size may play a role. Most non-regular workers in Japan are employed in SMEs. SMEs often have fewer capacities to invest in training than large companies and are less likely to have strategic human resource development approaches. Fourth, investment in training of workers is traditionally linked to the life-time employment model in the case of Japan.

Figure 3.6. Temporary workers and employer-sponsored training

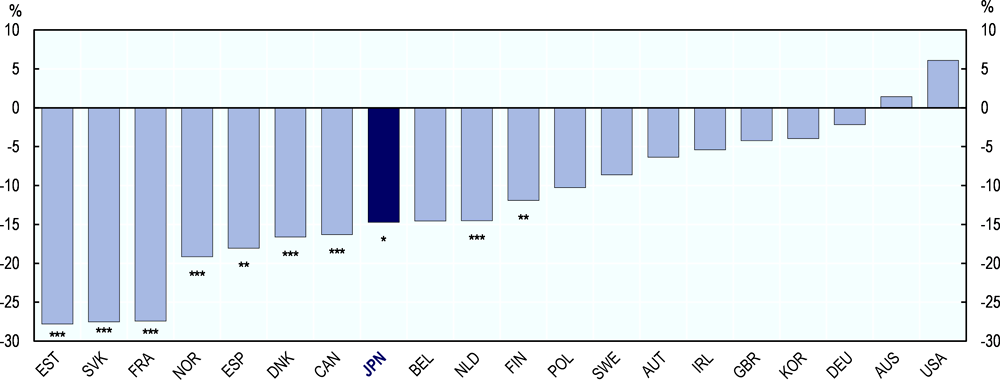

***, **, *: significant at the 1%, 5%, 10% level, respectively – based on robust standard errors.

Note: Estimated percentage difference between temporary and permanent workers in the probability of having received training paid for or organised by the employer in the year preceding the survey, obtained by controlling for literacy and numeracy scores and dummies for gender, being native, nine age classes, nine occupations, nine job tenure classes and five firm size classes. Data are based only on Flanders in the case of Belgium and England and Northern Ireland in the case of the United Kingdom.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/ as reported in the OECD Employment Outlook 2014, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2014-en.

However, even when controlling for a number of these factors as well as differences in numeracy and literacy proficiency, the gap in training between workers on temporary contracts and those on permanent ones persists in Japan and is relatively large compared with the gap in other countries (Figure 3.6). For example, the gap is much lower in Germany, Korea and the United Kingdom, or even positive in Australia and the United States. Reducing this gap could help many non-regular workers in Japan to obtain more training which could facilitate their transition to better quality jobs and more sustainable employment at older ages.

Participation in further training increases with educational level

As in other OECD countries, high-skilled workers in Japan tend to participate more often in work‑related training3 than the low skilled. In general, people who have already built up a substantial stock of human capital learn more easily and their rates of return to learning tend to be higher. Nevertheless, the share of high-skilled older workers who participated in training is much lower in Japan than in most other OECD countries (Figure 3.7). Older low-skilled Japanese workers are at a particular disadvantage with respect to training, as less than 20% of them reported in 2012 that they had participated in training during the previous year.

Figure 3.7. Work-related training by skill level, 2012 and 2015

Note: Data for Belgium refer to Flanders and data for the United Kingdom refer to England and Northern Ireland.

a. Year 2015 for Chile, Greece, Israel, New Zealand, Slovenia and Turkey; for all other countries, 2012.

Source: OECD calculations based on the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) (2012, 2015), www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/.

Identifying training needs is important

The need to train workers over the whole working life cycle rests on the continuous adoption of new technologies and forms of work organisation which are changing the skills needed in jobs. Training needs are also linked to changing jobs, functions or duties within the company. In many cases training needs to be identified. Good practice among companies starts with identifying skills needs through dialogue with employees, e.g. through regular performance dialogue and mid-career interviews which take a more strategic view (see Box 3.1). The training of human resource management staff to increase their sensitivity towards older workers is also a good practice. It is also important to ensure that managers have accurate perceptions about the value of training both mid‑career and older workers (Lindley and Duell, 2006[8]; Duell, 2015[9]). Conducting mid-career interviews is one instrument to detect skills needs and thus training needs of workers.

Box 3.1. Identifying training needs of mid-career and older workers in OECD countries

Conducting mid-career interviews can help to identify training needs and promote job mobility within a company. Increasing career flexibility thus includes changing tasks and functions, e.g. moving from a managerial post to an expert status, as is the case in some Swiss companies. In the United Kingdom, the use of mid-career plans around the age of 50 is promoted as part of a pilot project carried out from 2013-15 by the National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (NIACE). In an increasing number of countries, participation in training has become part of collective bargaining agreements. For example, in France, for the period 2009-12, 18 industry‑wide agreements were signed that contain career and skills development arrangements. Firms with more than 300 employees were under a three-year obligation to negotiate on forward-looking management of employment and proficiencies (called gestion prévisionnelle de l’emploi et des compétences (GPEC). Some more recent agreements seem promising. They include intergenerational arrangements for taking on board new employees and for the professional development of older workers (such as the generation contract), as well as job mobility. In Finland, the framework agreement of 2011 concluded between the social partners includes the employees’ right to participate in further training three working days annually

Mid-career interviews and counselling exists also in some Japanese companies. The focus of these interviews is mainly oriented towards providing advice about future employment options and conditions after reaching a certain age. The Japan Organisation for employment of Elderly, Persons with Disabilities and Job Seekers (JEED)4, provides companies, in particular SMEs, with this type of counselling. JEED should envisage to develop further its role in lifelong learning counselling combined with other age management tools in order to promote training activities for those aged 45 and above. More generally, a key challenge consists in strengthening skills needs identification and anticipation at all levels (company and local and national administrations). This would involve: skills needs assessments by individual companies; and carrying out skills assessment and anticipation exercises at the economy-wide, regional and industry levels.

Japan is promoting the establishment of career and lifelong learning counselling in companies. Practically, employers can introduce a mechanism “The Self-Career Doc system” that periodically provides employees with opportunities for various career workshops and career consultations, based on human resources development policies. In this way, employees can independently promote their own career development. In some OECD countries, training leave schemes exist, e.g. in Austria, where it has yielded positive results. (OECD, 2018[13])

In Japan, certified career consultant agencies have been established since 2001. They can be found operating in private employment service agencies, private companies and educational institutions. An online system to search for career consultants is available. From April 2016, several career service qualifications were subsumed into a single government certification of career consultants. This was done to ensure quality of the career services provided. Career consultants are obliged to be re-certified every five years. Up to the end of FY 2015, 53 000 persons had obtained career consulting certification.

Incentives for employers to invest in training

In some OECD countries, there are mechanisms in place to set incentives for individuals and employers to invest in training. These mechanisms can be established by governments or by companies, e.g. in a specific sector, and may involve different sources of financing from employers, individuals and governments (see Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Establishing mechanisms to set incentives for individuals and employers to invest in lifelong learning

(i) Individual learning accounts (ILAs)

ILAs are used in several OECD countries. They encourage savings for training. In general, ILAs can be used to develop knowledge, skills and abilities. There are different types of accounts, including individual saving accounts, individual drawing rights (which may be considered as “virtual accounts”), and vouchers (customized or lump-sum). The schemes can be universal or targeted at specific groups. The schemes vary with regard to the financial participation structure of the state, the government and the workers and the type of accompanying services (information, counselling, guidance of the beneficiary; certification and evaluation of training providers). The advantage of ILAs is that they provide some time flexibility, time being one important barrier. The portability of learning accounts from one employer to the other as well as the modularisation of certified training is likely to increase their usefulness and effectiveness.

(OECD, 2017[14])points out that it is important to combine demand-led financing mechanisms with a system of quality assurance through which providers are certified. With regard to tackling unequal participation in training by workers with different skill levels, ILAs suffer from self-selectivity into training activities. They are more likely to be used by high- than low-skilled individuals. One reason of unequal take up in those OECD countries where they have been implemented is likely to be the lack of information as well as financial illiteracy. Therefore, countries have moved towards including the provision of information and guidance in ILA schemes in order to better cover different groups of workers as well as to steer the choice of training. In some cases, they have included more generous provisions for the low-skilled.

In the case of France, lifelong career guidance is a central element for implementing the new individual learning account scheme.In France a new individual learning account scheme (compte personnel de formation), was introduced with the national multi-sectoral agreement of 11 January 2013 and taken up by a new law in 2014 (OECD, 2018[15]). This law introduced individual training accounts, career advice (from 1 January 2015) and an assessment interview at least every two years. The law sought to extend access to training to the loww-skilled and to employees of small businesses. A fund was set up to help finance individual training accounts for jobseekers and training plans for companies with fewer than ten employees. Each individual training account is credited with hours that employees may use throughout their working life for training leading to a qualification. Upon entering the labour market, every person will have a personal training account. This account is used by the person, whether employed or looking for work, to access training on an individual basis. Each member of the workforce has a “credit” of training hours that he (she) could use at every moment for vocational training leading to “a certification”. This credit is portable from one company to another. The first results are positive, but are limited among the employed, as take up has been highest among jobseekers (Cnefop, 2016[16]).

(ii) Payroll levies

Payroll levies on employers are used in some countries as a way to pool resources from employers and earmark them for expenditure on vocational training. It is expected that they help avoid the “free-riding” of some companies, stemming from the fact that some employers invest considerably in their workforce (with expected benefits for the whole economy) and other do not but can “poach” trained workers from other companies. They can either be introduced by public policy or through collective bargaining (OECD, 2017[14])

Levies can be regarded as an obligation for employers to invest in further training. It may prevent some firms from disengaging in further training. However, given the different nature of economic activities, the need for the volume for training differs between the companies. Therefore, it makes sense to regard it as a basic financial contribution of employers to training. One problem that has been identified with this approach is that companies can use the funds for other activities and charge them to training. The net impact of these levies also remains unclear, as the policy may encourage employers to provide more internal training than they otherwise would have (Falch and Oosterbeek, 2011[17]). These schemes may also not be sufficiently targeted, e.g. to promote training for the more disadvantaged groups, namely those with a low skill level and those who have a poor previous participation in further training. There is no evaluation evidence on how effective these schemes are for incentivising training for older workers. Further, if not targeted at SMEs, they are likely to benefit more large companies as these have more capacities to identify training needs of their workers and organise training.

One way for achieving greater employer buy-in in the use of training-levy schemes is to involve them more closely in the governance of such schemes, including on decisions on training priorities and funding allocation (OECD, 2017[14]). This is likely to be better achieved if the levy schemes are organised at the sector level, at the potential cost that sector interests may outweigh the priorities of national skills strategies.

Since 2004, a number of Inter-Professional Funds for Continuing Training have been established in Italy, partly funded by payroll levies, which provide training programmes that benefits a large share of workers aged over 45.

Government support for training of employed mid-career and older workers is limited

The Japanese government has three types of schemes in place to support the training of the labour force: i) subsidies for employers to train their workers; ii) subsidies for individual training for “self-training” or “self-development”; and iii) subsidies for training of the unemployed (see the section below on employment services for the unemployed for further details).

The Career Development Promotion Subsidy provides subsidies to employers for part of training expenses and wages paid during the training period for implementing accredited vocational training. In April 2017, changes have been introduced to the programme, which is now named the “subsidy system to support human resource development”. Employers who provide a highly effective training programme can receive a subsidy. Subsidised specialised training programmes are, for example, those that contribute to improve labour productivity, have both OJT and OFF-JT components, or are targeted at younger workers. The subsidy is basically provided on an hourly wage basis, and in some cases the cost of the training is subsidised. The amount varies depending on company size and type of training.5 Industries, such as construction and IT industries, receive an increased subsidy (subsidiszed percentage for the cost of OFF-JT programs is increased by 15 percentage points). Subsidies for general training are lower. One of the measures that are subsidised concerns training for newly hired middle‑age persons who had no regular employment over the past two years. Annex Table 3.A.1 gives an overview of existing subsidies in Japan to support employers to provide training to their workers.

The Japanese government has been actively promoting “self-development” of both, employed and unemployed, and, to this end, introduced the Education and Training Benefit (ETB)6 in 1998 which covers part of the training fees paid by individuals. To be eligible, people need to have been contributing to the Employment Insurance (EI) for at least three years (or at least one year in the case of first-time participation in training). The subsidy is available from Hello Work (Public Employment Service). It is a lump-sum payment equal to 20% of the cost of attending and completing an education and training course designated by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare, up to a maximum of JPY 100 000. It is available for numerous courses ranging from those designed for computer‑related qualifications and bookkeeping examinations. In 2014, an Education and Training Benefit for the courses entitled to “the benefit for professional practical education and training” was introduced for workers who contributed at least for three years to EI (or two years in case of a first training). In this case the benefit amounts up to 70% of the cost of course attendance, up to a maximum of JPY 560 000 per year.7 The scheme is available for courses ranging from professional graduate school to specific occupations such as nurse, care worker or childminder. From 2016, courses to acquire mid or high level IT skills have also been made available.

In FY 2016, about JPY 4.2 billion was spent for general education and training courses and JPY 2 billion on professional practical education and traning courses. In total 111 800 people received the ETB for general courses. Only 9% of participants were aged 55 and above, while 23% of participants where aged 45-54. In the same year, 21 000 people received the ETB for professional courses. In the latter case the majority of beneficiaries are women, while this is not the case among those participating in the general courses. According to the 2016 administrative survey, 60% of beneficiaries were in employment (almost all as regular workers) and the remaining 40% were unemployed. The motivation for the employed to take up this benefit was to increase their skills and abilities in order to get a better compensation/evaluation in their firms (only 12.6% answered that the reason why they use benefits is wishing to change jobs). The overall low take up of the benefit may be linked to long working hours.

JEED and the prefectures have been establishing and operating public facilities for vocational ability development in order to provide: i) long-term training for graduates of junior and senior high schools; ii) training for workers to provide them with high-level skills and knowledge required to cope with technological innovation and changing industrial structure; and iii) training for the unemployed. In FY 2015, 303 570 people participated in these Public Vocational Training Plans, of whom slightly more than half were unemployed and 38% were employed and 7% were graduates.

Other OECD countries have started to focus on promoting training of mid-career and older workers at all skills level. A number of countries have developed lifelong learning strategies and have reformed their institutions. Providing access to vocational education and training (VET) to all age groups is one key element for building up lifelong learning system. Countries that have opened their VET system to adults and have promoted adult apprenticeships include Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. With the introduction of New Zealand Apprenticeships, all apprentices now receive the same level of government support regardless of age.8 In Finland, a new adult VET programme was started in 2014 for low qualified adults aged 30-50. Within the system of Competence Based Qualifications, an extra possibility to study for a vocational qualification or part of it (a module) is offered to this target group (OECD, 2018[20]). In Denmark the adult training system contains many programmes. Although they are based on legislation, the social partners are heavily involved in implementation (OECD, 2018[21]). In Sweden, in 2009 the government initiated temporary measures for vocationally oriented upper secondary adult education (yrkesvux), including older workers. The main purpose was to counter the effects of the recession and labour shortages, and to reach individuals who lack upper secondary education or who need to supplement their upper secondary vocational education. Vocational training may be offered within the framework of municipal adult education, as well as education for intellectually challenged adults. All higher vocational education programmes are offered free of charge and entitle students to financial support, and any associated fees for course materials must be reasonably priced (OECD, 2015[22]).

Some lessons can be learned from the government-supported adult apprenticeship programme in the United Kingdom. In 2012/13, about 45% of people starting a government-supported apprenticeship (mainly at Level 2 and 3), lasting for at least 12 months, were aged 25 and above and a fifth was aged 40 and above (with 13% of all participants being aged 40-49). Older apprentices are more likely than their younger peers to start a Level 3 or above programme. The programme may be linked to the certification of prior learning. In an evaluation of the UK apprenticeship programme, adult apprentices were found to be quite heterogeneous regarding their previous work careers (Fuller et al., 2015[23]). Case studies point to a latent demand from adults for training and qualifications, including in English, maths and Information Communication Technology (ICT), with a view to career advancement.

Many OECD countries have also offer subsidised adult literacy and numeracy programmes (Windisch, 2015[24]). One example is the UK “Skills for Life” strategy, which was launched in 2001 to create a new infrastructure to support free adult basic skills learning opportunities over a seven-year period and improve the basic skills of adults. The programme was evaluated on the basis of a longitudinal approach (Meadows and Metcalf, 2007[25]). It was found that college-based adult literacy and numeracy courses had a range of positive effects over a period of three years after terminating training, including increased learner self-esteem and improved commitment to education. In Ireland, the objectives of the Adult Literacy programme are to increase access to literacy, numeracy and language tuition for adults whose skills are inadequate for participation in modern society and the social and economic life of their communities. The aim is also to increase the quality and capacity of the adult literacy service. In 2010, approximately 21% of participants in the Adult Literacy programme and 18% of participants of the Back‑to‑Education Initiative (a part-time training scheme leading to a certification through the National Framework of Qualifications) were over 55 years of age (OECD, 2018[26]). Others (e.g. Germany) have introduced financial support to promote upskilling of older and low-skilled workers (OECD, 2018[27]).

Improving the system of recognition and validation of prior learning

In 1959, Japan introduced the National Skills Test, a skills assessment system to test and certify the skills that workers have acquired through formal (but not certified) or non‑formal learning. It is regulated by the Human Resources Development Act. The MHLW specifies grades or skills levels for different job categories through an Ordinance. There are 126 job categories, as specified by a Cabinet Order (in 2017). Most job categories are classified in three grades. Each job category is reviewed on a yearly basis in order to adapt standards for the practical and theoretical examinations. The MHLW and the Japan Vocational Ability Development Association prepare the National Skills Test examinations, which are implemented at prefectural level. During FY 2016, there were 757 400 applicants, of whom 303 500 were successful (success rate of 40%). These have become “certified skilled professionals”. The majority of applicants took the national skills test for the job category “financial planning”.9 Other main categories include manufacturing occupations. According to the experience of the public employment service, Hello Work, being a certified skilled professional is helpful for finding an adequate job. There is room for improvement and extension of the National Skills Test system, and the preparation for passing the test, as failure rates are high. The system as such is crucial as company-based training is still the dominant form of training for adults and standardisation of vocational training rather weak. Also, given the risk of demotion of older workers when they change jobs, the National Skills Test system could be an important instrument to keep skills use of older workers at the highest possible level.

In 2008, the Job Card system was introduced, initially for young people. It has later been extended to all age groups. The Job Card system can be used, with the support of career consultants and other personal support, as a tool for career planning throughout the life‑course and as evidence of vocational ability in job-search activities and skills development. The system initially aimed to help young people with little experience to find a full-time position. The Job Card is used as the basis for: providing career counselling; providing vocational training combining practical workplace training and classroom lectures; and compiling after-training evaluation of vocational abilities and other information including the person’s employment record. Usage and acceptance of the system by companies is low so far. Developing further the Job Card system in a manner that upskilling and recognition of non-formal learning is accepted and used by companies would help increase take up by mid-career and older workers.

In 2002, the MHLW introduced vocational ability evaluation standards. These were developed to systematically evaluate the knowledge, skills and ability to carry out the tasks required for jobs in four skill levels, ranging from junior staff levels to the heads of organisations. Companies can use these standards as objective measures to evaluate vocational skills of their employees. The standards were developed in cooperation with industry associations. From August 2015, vocational ability evaluation standards had been set for 53 types of jobs including cross-industrial clerical work such as accounting and human resources, electrical manufacturing, and hotel services. The results are also utilised for a model evaluation sheet of the Job Card System. The companies can also customise the standards. Using the standards is voluntary. According to administrative surveys in FY 2016, 84% of companies using these standards say they helped improve the employment evaluation system and the human resource development system as well as recruitment activities.

Across OECD, some countries have introduced programmes that link upskilling of mid‑career (and older) workers to recognition and validation of prior learning. One example is Finland, where a new adult VET programme was introduced in 2014 for low‑skilled adults aged 30‑50. It is embedded in the system of Competence Based Qualifications, which recognises competencies acquired in a variety of ways and which offers the possibility to complete a vocational upper secondary qualification, further vocational qualifications and specialist vocational qualifications as a competence-based qualification. With the new programme, an extra possibility to study for a vocational qualification or part of it (a module) is offered to this target group (OECD, 2018[20]). In Portugal, the former New Opportunities Initiative (INO) (2005-10), which extensively implemented adult training measures, provided low-qualified adults whether employed, unemployed or not in the labour force with a way of obtaining formal recognition of non‑formal and informal learning and skills acquired through their working lives. This process was complemented by formal learning at the 4th, 9th or 12th grades of education and/or vocational certification. A system for recognition, validation and certification of qualifications (Reconhecimento, Validação e Certificação de Competências, RVCC) was set up.10 Most of participants in the programme were employed workers (Duell and Thévenot, 2017[28]). Evaluations found that certification had a positive impact on income and employment but only when combined with training courses (Carneiro, 2011[29]).

Enhancing transparency of the VET and education system – lessons from Europe

In order to render the VET and education systems more transparent and comparable across Europe, the European Commission has set up a European Qualification Framework (EQF), which entered into force in 2008. The implementation of the EQF was based on the Recommendation on the European Qualifications Framework for lifelong learning adopted by the European Parliament and the Council on 23 April 2008. It has since then been transposed by Member States into National Qualification Frameworks (NQFs). In 2017, a new set of Recommendations to implement the EQF have been adopted. Before 2005, NQFs have been set up in three European countries (France, Ireland and the United Kingdom). By 2017, NQFs have been introduced in all 39 EQF participating countries.

The EQF distinguishes between eight qualification levels. Most importantly, it has promoted two principles supporting the modernisation of qualifications systems and directly contributing to NQF developments. First, the learning outcomes perspective focuses on what a holder of a qualification is expected to know, be able to do and understand. Second, it is based on a comprehensive approach covering all levels and types of qualifications: formal education and training (VET, general education, higher education) as well as qualifications awarded in non-formal contexts.

The importance of the transparency of the VET system, which makes qualification easily tradable, has been widely acknowledged in the case of the initial vocational training system in Germany. With the development of the Deutscher Qualificationsrahmen (DQR), which transposes the EQF in Germany, this has been extended to further (vocational) training. Thus Germany, as well as some other European countries such as Austria, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden, have started working on procedures for including non‑formal and private sector qualifications and certificates (Cedefop, 2018[30]). A recent study carried out in Germany on the potential use of the German qualifications framework (BMBF et al., 2017[31]) identifies several areas where the DQR can add value. It can be used to support human resource development (recruitment and development of employees) in particular in SMEs. However, this will require raising employer awareness of the DQR. A survey conducted by this study among training and education institutions, business associations and employers showed that its usefulness is mainly valued by private further training institutions, but less by companies. According to (Cedefop, 2010[4]), the most successful example of good framework visibility in the labour market is the French NQF (Répertoire national des certifications professionnelles, i.e. national register of vocational qualifications), where qualifications levels are linked to levels of occupation, work and pay (Allais, 2017[32]).

Improving digital and entrepreneurial skills at all ages and preparing workers for new forms of work

Some countries have started to promote the development of the ICT skills of older workers. Fore example,in Greece, since 2012, 50plus Hellas (www.50plus.gr) has been providing free ICT training to older people with the support of a national telecommunications company and local authorities. Other countries are promoting a broader approach to adapting the skills of older workers to changing skill needs. In Germany, the programme “Corporate Values People Matter” (UnternehmensWert Mensch) was initiated in 2014, funded by the European Social Fund and the Federal Ministry for Labour and Social Affairs. The programme’s objective is to help SMEs develop future‑oriented, employee‑centred human resource management strategies with a holistic approach, including diversity management, work organisation, training and health measures. In particular, one objective of the training measures is to help prepare and adapt to the digital economy. The programme subsidises consultancy services for SMEs for up to 50% or 80% of these costs. On-site consultancies in a company may last about ten days. During the first two years, about 3 000 companies benefited from the programme, Which included entrepreneurship education at schools, technical colleges and universities.11

Preparing future generations for a changing world of work in which self-employment may become more important should include developing and fostering their entrepreneurial skills. The OECD has recommended to develop entrepreneurial education at school in Japan (OECD, 2015[33]).

Since the 1990s, entrepreneurship education has grown substantially, in particular in countries already known as entrepreneurial such as the United States, Canada and Australia as well as in Nordic European countries (Schoof, 2006[34]). It takes place at different levels of the educational systems, mainly at the secondary educational level and universities, but also outside the formal education system. While entrepreneurship training at secondary schools aims primarily at developing an entrepreneurial mind-set. Programmes that seek to promote immediate enterprise creation for young people can be run at vocational schools or universities (Hofer and Potter, 2010[35]; European Commission, 2008[36]). These programmes are often delivered within a partnership framework. Training centres, universities, development banks, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as well as business persons, have been involved in establishing curricula, providing the training or developing training material. Entrepreneurship skills can also be built up at a later stage. For people from disadvantaged groups entrepreneurial skills can be built up through a combination of general entrepreneurship training for all and more targeted start-up training, or with other measures to support start‑ups (OECD/EU, 2015[37]).

Rendering employment services more efficient

There is a need to help older jobseekers back into quality jobs

Improvements in vocational education and training are critical for Japan to keep older workers employable and make it possible for them to stay in their jobs longer. Even then, some older workers will face job loss as a result of current retirement rules and human resource strategies of companies. Providing older jobseekers with effective support to move back into rewarding and productive jobs, is therefore essential to foster a more inclusive labour market. In the context of Japan’s rapidly ageing population, combined with a high degree of labour mobility of older workers, it is important that middle-aged and older jobseekers have access to good employment services and effective active labour market programmes (ALMPs) to help them make successful job transitions and to minimise the costs of those transitions. This is also important in a view of overcoming labour shortages in Japan.

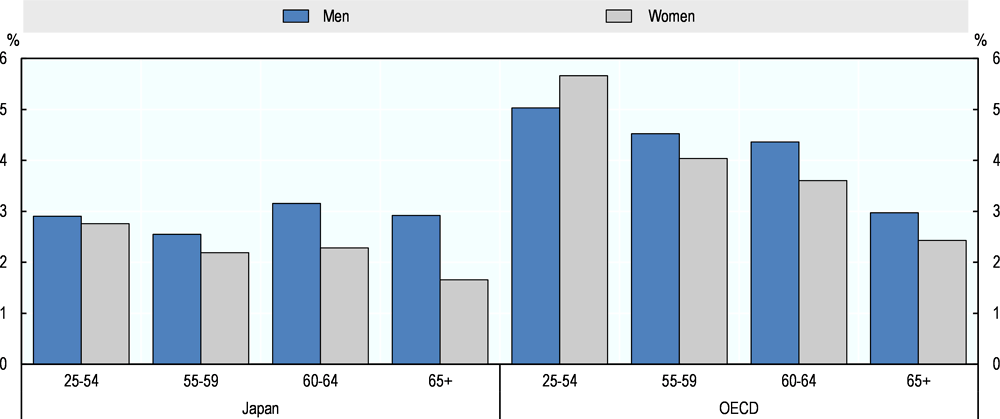

In contrast to OECD average, the unemployment rate in Japan is low, as shown in Figure 3.8. However, the unemployment rate increases for the age group 60‑64 refelcting rules around mandatory retirement age as well as the difficulties older workers face in finding new employment compared to prime age workers. The unemployment rates are higher for older men aged 55 and above compared to older women . This is partly explained by the higher incidence of women in part-time and non-regular work as well as their higher likelihood of leaving the labor market when they cannot easily find a job.

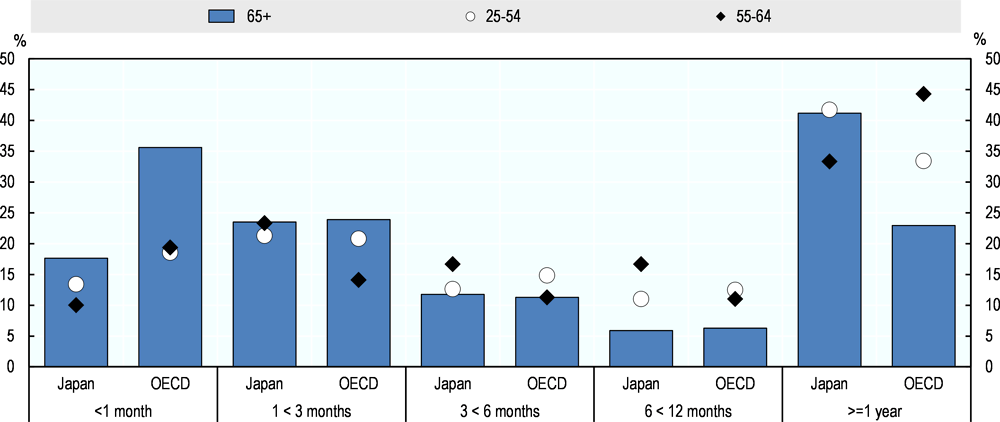

Once unemployed, older workers aged 55-64 on average, are likely to stay out of work for shorter periods than their counterparts in other OECD countries and younger workers in Japan. This could be attributed to additional government policies namely the Act on Stabilisation of Employment of Older Persons that mandates employers to either retain or re-hire older workers when they reach mandatory retirement age. However employment prospects are still much harder for those aged 65 and above as they make up 40% of the long-term unemployed in Japan - nearly double the OECD average (Figure 3.9).

Figure 3.8. Unemployment rate by broad age group and gender, Japan and the OECD

Note: The OECD is a weighted average.

Source: OECD Dataset LFS by sex and age - indicators, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=54218.

Figure 3.9. Unemployment by age and duration, Japan and the OECD

Note: The OECD is a weighted average.

Source: OECD Dataset on Incidence of Unemployment by Duration, http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=9593.

Supporting older workers in job-search activity and placement through Hello Work

Hello Work, the Japanese Public Employment Service (PES), consists of 544 locations nationwide. Hello Work provides vocational counselling, job search guidance, referrals to active labour market programmes, including participation in vocational guidance, and placement services.

Main Hello Work offices in prefectures have a special corner for older jobseekers aged 55 and above and special corners for those aged 65 and above. At these corners older jobseekers can make appointments with the advantage that they avoid waiting; are followed-up by a caseworker and the caseworker can prepare counselling in advance. Also at these corners, age-adapted computer screens are available for job-search though not all older jobseeker are using the special desk. Overall, older jobseekers are more likely to come to the Hello Work offices than younger jobseekers, as they more often lack digital skills to search for jobs online. If they claim unemployment benefits they have to show up every four weeks.

There is no evidence on the effectiveness of counselling and guidance services provided to older workers in Japan. However, they have shown to be effective, according to the scarce evaluations that exist across OECD countries. In Switzerland an evaluation of intensive counselling provided to older jobseekers has proved to yield positive results (Arni, 2012[38]). In Australia, the Experience+ Career Advice Service, implemented in 2010, enabled Australians over the age of 45 to receive additional career counselling and résumé services. The effectiveness of measures may be further increased if different measures and tools are combined (e.g. combining subsidies, training elements and counselling). In Austria, the PES also provides a counselling programme to employers with special emphasis on the development of life-cycle oriented educational programmes and the dissemination of the concepts of “diversity management” and “productive ageing” (OECD, 2018[13]). In Germany, the Programme “Perspektive 50+”, running from 2005 to 2015, was implemented by the PES for unemployed means-tested minimum income recipients aged 50 and above focused on providing counselling. The programme worked also to change the attitudes of employers. Regional employment pacts were set up, in partnership with nearly all jobcentres as well as with a wide range of local stakeholders such as companies, chambers and various associations, trade unions, municipalities, training institutions, churches and social service providers. Evaluations of this programme showed positive results (OECD, 2018[27]).

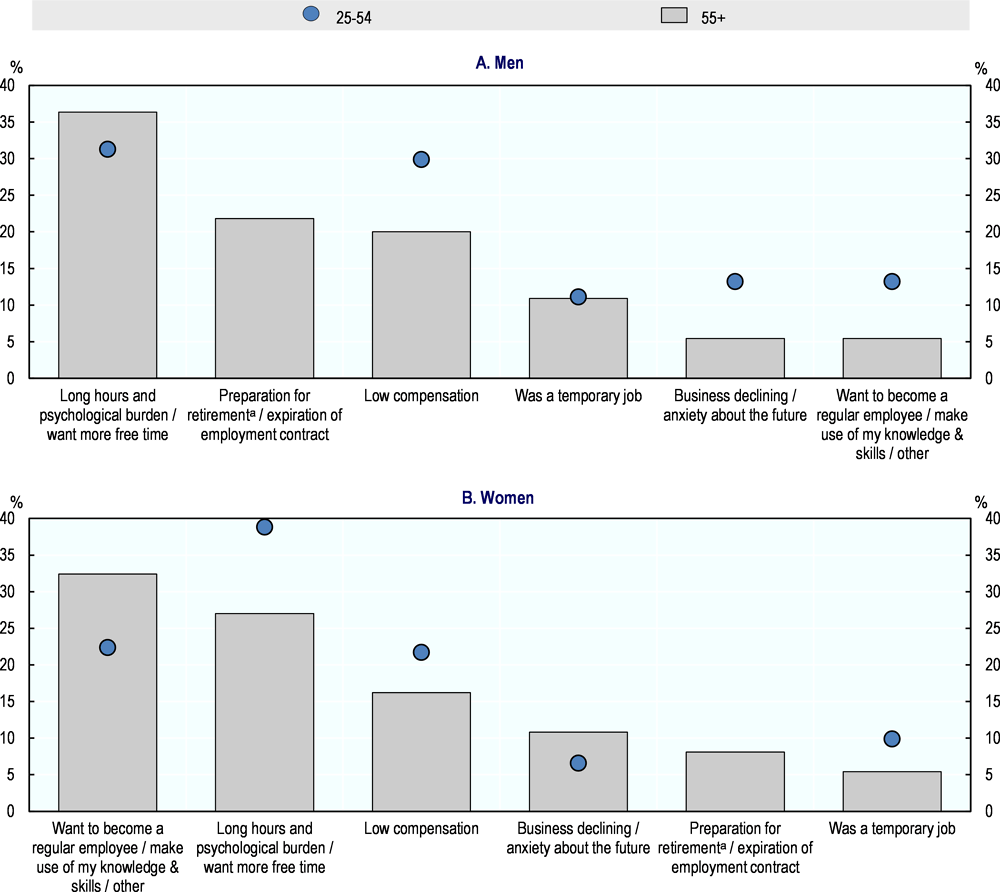

Major challenge facing Hello Work are to match older unemployed workers to jobs that fully utilises their experience and skills as well as meeting their job preferences. For instance, the main reason for job changes for older men as well as younger and prime age men are long working hours and psychological burden (Figure 3.10, Panel A). A low compensation was less often a driving force for changing jobs for older as compared to younger men. (Figure 3.10, Panel B). This indicates that Hello Work would need to make greater efforts in matching older workers with job opportunities with shorter working hours and low job strain.

Figure 3.10. Reasons for wanting to change job, by broad age groups and gender

a. For ages 25-54, the cell size was too small for this category.

Source: Japan Household Panel Survey (JHPS/KHPS) provided by the Keio University Panel Data Research Center.

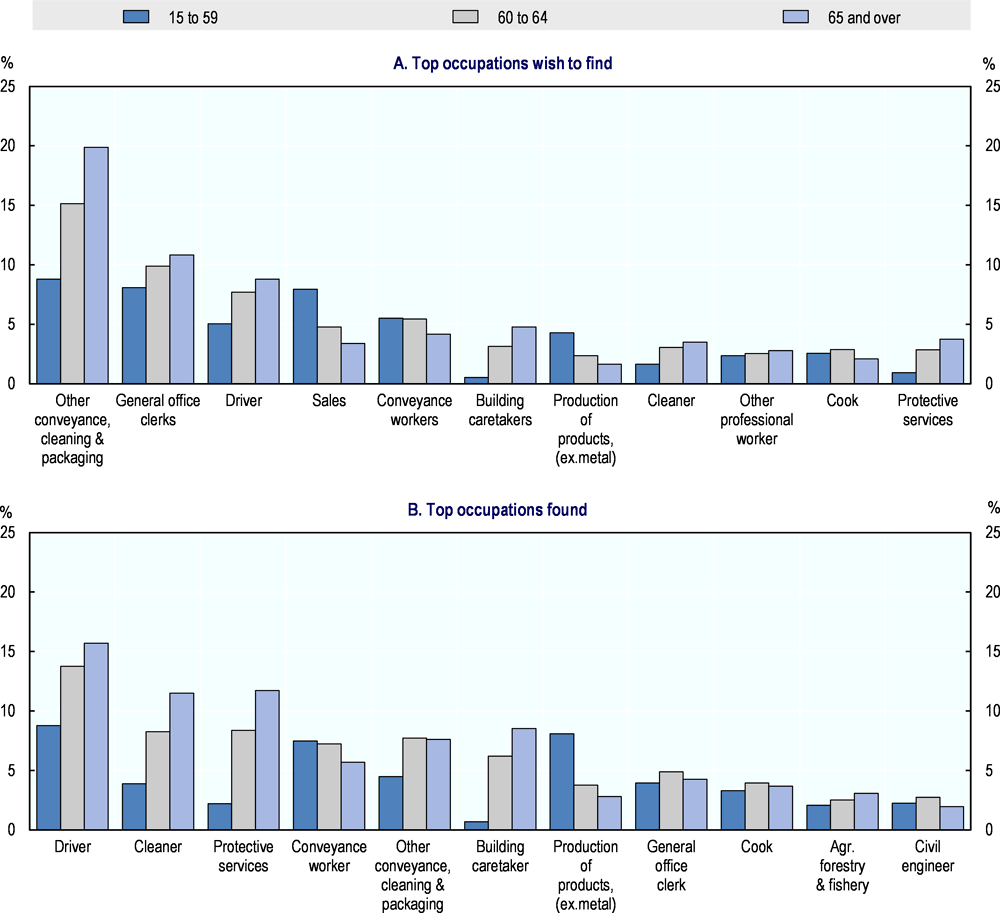

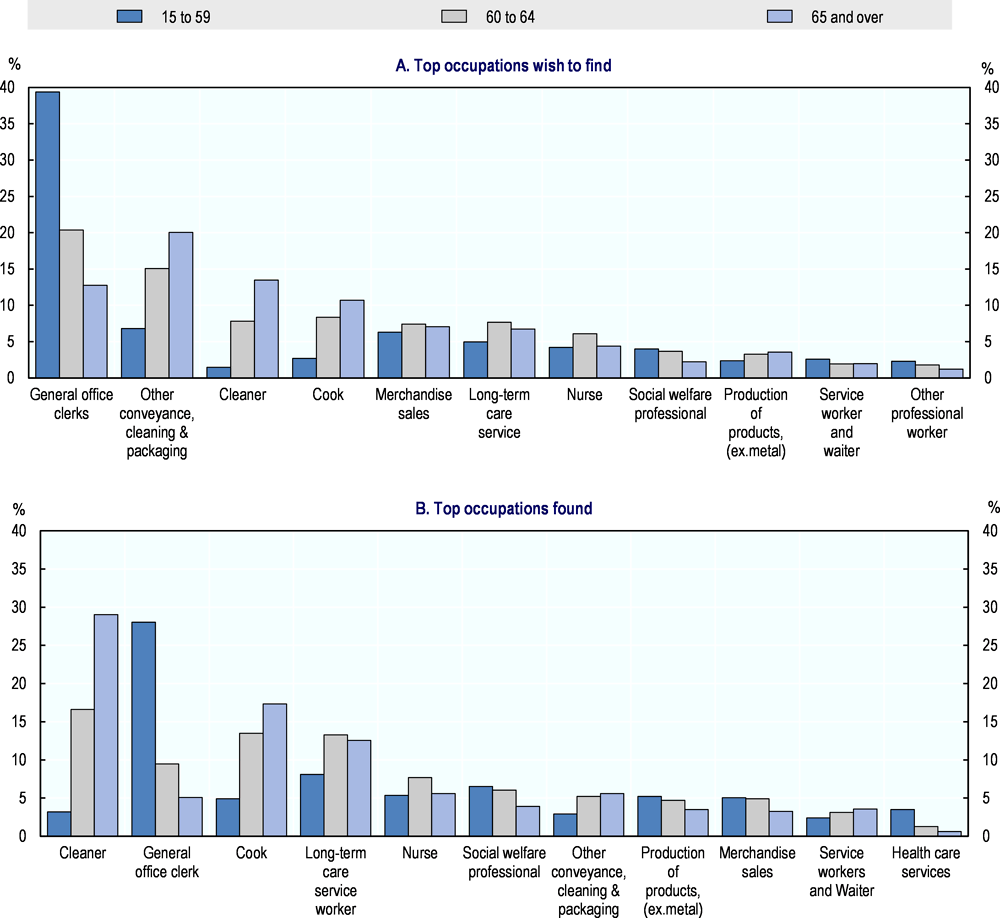

Upon registration at Hello Work, jobseekers are asked about their job preferences. However, in many cases their wishes are not fulfilled, and older jobseekers often have to take up jobs that do not correspond to their qualification and experience gained over the working life. Older jobseekers are steered towards occupations for which there are shortages and which younger workers would not be interested (Annex Figure 3.A.1 and Annex Figure 3.A.2 in the Annex). According to administrative data of Hello Work, in FY 2016, among those searching for work using Hello Work services, men typically found an employment as drivers, cleaning, packaging, conveyance and related workers. Women at this age eventually found most often a job as cleaning worker (16.6%), as long-term care service workers (13.2%) and as a cook (13.5%), while for roughly half them these were the occupations they wished to perform. At the same time, Hello Work counsellor find it difficult to change mindset of jobseekers, so that they accept this kind of job jobseeker use to come often to the Hello Work office. Hello Work offices may have a special desk for job offers in shortage occupations such as in the area of childcare and nursing (information provided to the Secretariat during the mission to Japan).

Among other factors, stigma and stereotypes as well as lack of concise information on employment barriers can undermine efforts to good quality job referals and job placement. While the specialised counselling desks for older workers have their advantages, they also run the risk of reinforcing age stereotypes. To complement knowledge and experience of caseworkers, Hello Work can develop statistical profiling tools as used in many other OECD countries to help PES workers diagnose employability of jobseekers, and to assist in prescribing the type, intensity and duration of services needed to get them back to work in a more systematic way.

Moreover, older workers are often confronted with complex and inter-related employment barriers, such as skills deficiencies, health problems, or care responsibilities. Collecting systematic and good-quality information on the nature and extent of these obstacles which is currently missing can also provide a better match between individual needs and available support, and make associated policy interventions more effective and less costly. It can also enhance efforts to integrate support across different services of Hello Work and across institutions. Hello Work can use individual and family-level data to provide concise statistical portraits of the circumstances of individuals with labour-market difficulties by using the OECD methodology developed under Faces of Joblessness.

Preventing older workers from becoming inactive

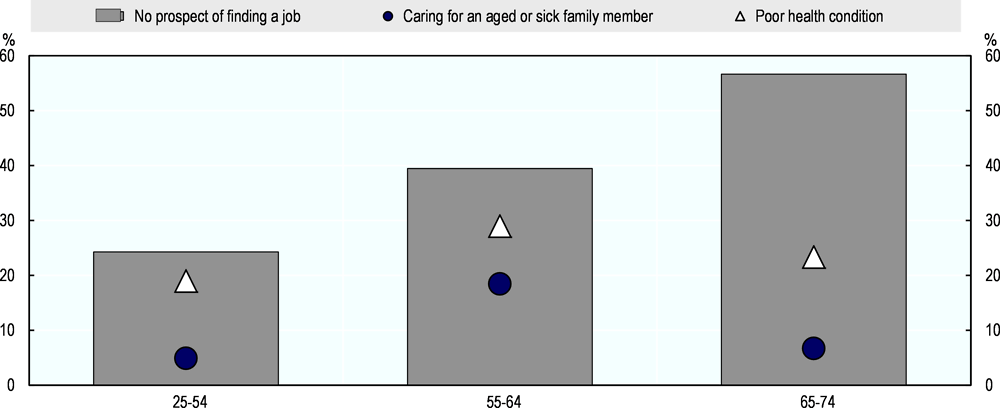

In view of the daunting challenge of population ageing, it is also important to mobilise those who are not searching work but who would wish to work. This group accounts for10% of inactives aged 55-64 and 3% of inactives aged 65-74. However, according to the Japanese Labour Force Survey more than half of inactives wishing to work aged 65 and 40% of those aged 55-64 percieve there is no prospect of finding a job.

Caring for an aged or sick family member and poor health conditions both are other major factors for not searching for jobs among older workers. However, care responsibilities are bigger employment obstacles for 55-54 years olds than for those aged 65 and above given that caring for older parents is more likely to occur before reaching the age 65. Age differences are less marked for those wishing to work but not searching because of poor health conditions. Still almost a quarter of those aged 65 and above and 29% of those aged 55‑64 indicate that poor health refrain them from searching for work (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.11. Reasons for inactives wishing to work but not searching employment

In order raise employment rates of older workers and to avoid that older workers transit from employment to inactivity when reaching (mandatory) retirement age, there are various measures in place to motivate them while they are still at work. These activities tackle one of the main the employment barrier that is the prospects for not finding a job. These activities also have the objective to increase the motivation, and thus the willingness to stay in the labour market (see e.g. (JEED, 2018[39]), see section 3.1).

The Industrial Employment Stabilisation Centres (IESC), which were set up in the past in the context of industrial restructuring (decline of steel and shipbuilding industry), have been assigned new tasks in order to promote job mobility between companies. IESC operate throughout the country and provide services for employers and employees by proactively contacting and visiting companies. Notably, IECS has established a database with people close to retirement age. They are contacted and encouraged to continue to work. IESC includes in its data base companies that are willing to hire workers aged 65 (information provided to the Secretariat during the mission to Japan). Activities of these centres are financed through the government, membership fees of companies and fees for seminars. MHLW is assessing their achievements on the basis of the number of people being transferred. In recent years, the number of open positions increased, and the number of available workers interested to be transferred decreased. In FY 2016, the ratio of opening positions to the number of workers available for being transferred was 5.7.

IESC has also run a work trial programme for mid-aged workers aged 40-50, where workers are placed on a trial bases for one year in another company. After the trial, workers either re-integrate into their old company or quit job and stay with the new company. Subsidies for this programme are available. IESC has set-up a labour intermediation data bank for this purpose. However take-up has been low as companies perceive a risk of losing talents. If workers come back after the trial, it might be difficult to find an adequate job within the company. Further, companies have concerns about confidentiality. Sometimes, it is in the interest of companies to displace workers. From the point of view of the receiving company one year is not enough to make the trial worker productive and uncertainty on whether the worker will stay will refrain the companies to invest much in the training of the trial worker (information provided to the Secretariat during the mission to Japan). Instead of having different agencies in charge of the labour mediation for employed and unemployed it could be considered to concentrate these efforts at the PES and develop there capacities to ease job-search of the employed.

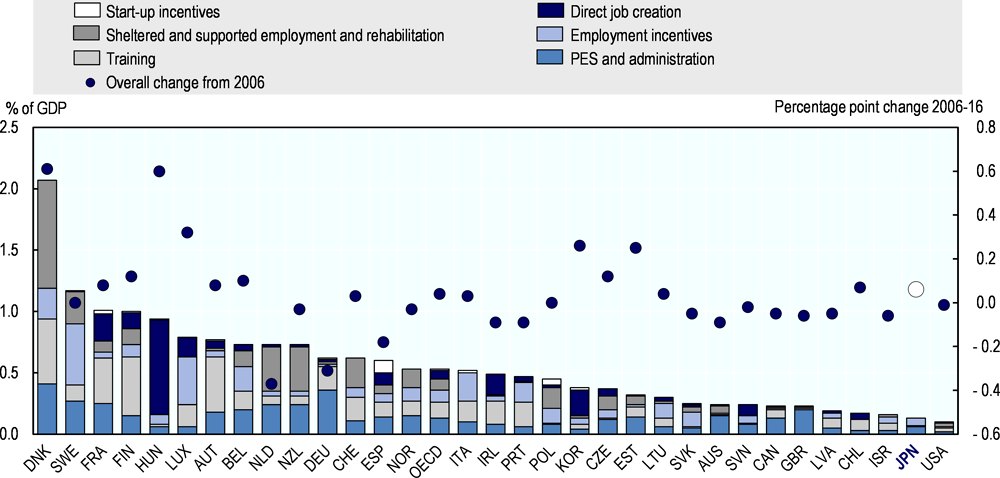

Japan is spending little on active labour market programmes

Spending on active labour market programmes is low as compared to other countries albeit they have increased markedly in recent years from a low base (Figure 3.12), In 2016, Japan spent 0.14% of its GDP on active labour market programmes (ALMP), considerably below the OECD average (0.54%). Half of Japan’s ALMP spending is on PES and administration activities i.e. administration of benefits and job-search support. This suggests there is a strong emphasis on information and counselling as primary tool to help unemployed older workers and other jobseekers alike.

Figure 3.12. Despite more than doubling public spending on active labour market programmes over the past decade, Japan has one of the lowest expenditures among OECD countries in 2016

Note: Data refer to 2011 for the United Kingdom (change 2006-11), to 2015 for France, Italy and Spain (change 2006-15) and the change from 2008-16 for Chile.

Source: OECD Ddatatset on Public expenditure and participant stocks on LMP, (http://stats.oecd.org//Index.aspx?QueryId=8540).

Almost another half is spent on employment incentives although expenditure in this area is still much below the OECD average. The measure includes a range of subsidies targetted at improving employment of jobskeers aged 65 and above and to meet the cost towards improving environment for hiring older workers e.g. employers who convert older temporary workers status to permanent status.

Public works have continued to play an important role in Japanese employment policies, but as a demand-side measure and a regional development policy, rather than a labour market programme where jobs are reserved for the unemployed. Only 0.01% of the ALMP spending was reported in 2016.

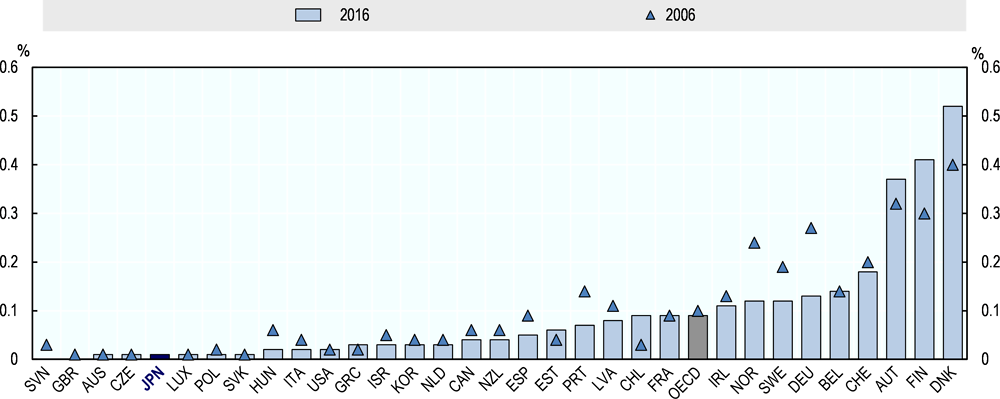

Finally, as compared to other OECD countries, Japan spends very little on institutional training as compared to most OECD countries (Figure 3.13). One major factor for this is that on the job training in Japan is traditionally more dominant than public led training.

Figure 3.13. Public expenditure over the past decade on institutional training across OECD countries

Note: Data for 2006 refer to 2008 for Chile; data for 2016 refer to 2011 for the United Kingdom and to 2015 for France, Greece, Italy and Spain.

Source: OECD Dataset on Public expenditure and participant stocks on LMP, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=LMPEXP.

About 40% of participants in public vocational training are unemployed. In FY 2017, the earmarked budget is JPY 96 billion. The national council on training annually decides the volume of public vocational training based on national budget, taking human resource needs of growth industry and regions into account. Efforts have been made to anticipate the skills needs of regional industries and companies. Councils are established in each prefecture, comprising local labour-management organisations, the prefectural government, Hello Work and private educational/training institutions, cooperation and coordination are promoted so that the state, prefecture and private institutions can offer training programs leveraging their own features and eliminate overlap with the programs provided by other organisations. Skills anticipation of local and regional labour markets are essential for providing meaningful training for the unemployed. Training of mid-aged and older workers should, however, also capitalise on prior learning and competencies of the worker in order to avoid demotion and increase productivity.

Public vocational training is organised by the national and prefectural agencies. One example of a public facility that provides training to older jobseekers is the Tokyo Vocational Skills Development Center (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Tokyo Vocational Skills Development Center providing short-term training courses for older jobseeker

Tokyo Metropolitan Vocational Skills Development Center, provides as a public entity public vocational training for jobseekers and employees, with a specific focus on those who work in SMEs. There are currently four Vocational Skills Development Centers in Tokyo, eight schools, and one Vocational Skills Development School for persons with disabilities in Tokyo. In 2017, in Tokyo about 15 800 training places were available for “ability development training”, of which 20% were provided in-house and 80% were commissioned. In FY 2017, 5.6% of training places in these courses got specific courses were earmarked for older jobseekers aged 50 and above. These can be trained for three to six months in 13 areas, such as building management, livelihood support services, cleaning staff training, garden construction management, equipment maintenance, electrical facility maintenance, hotel and restaurant service (5.6% of all participants in “ability development training” for jobseekers). Older jobseekers can also participate in the general courses, which includes basic computer courses (among the “ability improvement training” measures) 4.1% of participants were older jobseekers). One of the four Vocational Skills Development Centers, the Chuo-johoku Vocational Skills Development Center, offering training to seniors since the 1990s (at that named Tokyo Metropolitan Senior Otsuka Occupational and Technical School for elderly), has specialised in providing training older jobseekers in their interior finishing department, building management department and hotel and restaurant service department (all six months courses). The school provides placement services in cooperation with Hello Work. Placement rates are high, as the training offers have been developed based on close contacts with and skills need information provided by local industry associations.

Source: Information provided to the Secretariat during mission to Japan

There is limited number of studies to analyse the effect of public vocational training based on the quantitative model. (Kurosawa, 2001[40]) estimated wage changes of trainees before and after taking public vocational training. Taking into account sample selection bias, she revealed that training has positive impact on getting a new job, but wage of male over aged 45 was changed to negative direction after training. (Kurosawa and Hotokeishi, 2012[41]) compared effects of national and prefectural institutional training and entrusted training on placement rate after training. They showed that public institutional training resulted in higher placement rate than entrusted training, and national vocational training showed better performance than prefectural training. They recommended closer communication and cooperation between national, prefectural and private training institution to share best practices on ways of organising training curricula, training methods and placement assistance12. Assessing the outcome of the Support System for Jobseekers (for all age groups), (Fujimoto, 2016[42]) finds that employment were relatively high in the fields of long-term care, medical administration, construction, hairdressing and beauty. When controlling for the course’s field, the author finds that counselling, guidance, support in job-search, finding job offers and leading participants in joint briefing sessions held outside the training institution helps improving the labour market outcome. Effectiveness is increased when the training agencies actively engage in information exchange and partnerships with industry associations.

Closer cooperation of various actors providing placement services for older workers needed

Some municipalities provide job creation programmes, guidance, or training programmes for older worker and may run their own employment programmes. They can apply for a three year grant in order to tackle local labour market problems, such as labour shortages and promotion of employment of older worker. One example is the Kashiwa Liaison to promote the “ageless society” set up in the city of Kashiwa (Chiba Prefecture), which has the objective to improve access to employment, create better working environment for older people, and tackle the negative attitude of employers towards older workers. The first two projects were run from FY 2009‑13 and from 2014‑15. The current “Kashiwa” project is running from 2017‑20 with the aim to to place older unemployed into work and provide training if necessary. Main partners are Kashiwa’s city Silver Human Resources Center (see below), the chamber of commerce, companies, Institute of Gerontology of Tokyo University, Second Life Factory (see below), Japan Finance Corporation, Kashiwa’s city government and the city’s council for social welfare. Companies and workplaces are visited before making job referrals to check the work environment, working conditions and job duties. One advantage of the jobs offered to older workers through this project is that they are part-time jobs (based on a work contract). Priority areas for placement have been identified in the area of child and old-age care, livelihood support, retailing and services and manufacturing. In addition to job creation and placement activities, the project provides training opportunities in the second life factory (e.g. trainings for cutting trees). The project is subsidized with a maximum budget per year of JPY 20 million; nearly three quarter of this budget is provided by MHLW

While the tasks of Hello Work should not be duplicated by municipal employment programmes, it is useful if municipalities develop integrated approaches to tackle ageing (including providing elderly care, social integration programmes, etc). To improve the efficiencies of such programmes, municipalities could outsource the delivery of social integration through a tendering process. Nevertheless, in such an integrated approach, Hello Work should be a strategic partner.

Silver Human Resource Centers (SHRC) started to operate on an experimental basis in 1974. The 1971 Act entrusts Silver Human Resources Centres with providing “easy task for older retirees”. The programme was formally established in 1989 and expanded rapidly. The SHRC programme is being promoted to provide convenient community based temporary and short-term job opportunities for their members (Duell et al., 2010[43]). Workers who accept jobs through SHRC are not always protected by labor laws as they are classifies as contract workers. This means that sometimes they can be paid below the minimum wage despite guidelines not to do so. In, 2015, there were 1 272 centers with approximately 720 000 members, who are in general retired. Most of the work that they undertake consists of indoor and outdoor general work (e.g. park clean‑up, cleaning in household, administrative work such as administration of car-parking lots). SHRCs work closely with local stakeholders, such as the municipalities. From FY 2016, a new project for creating employment opportunity has been started with cooperation among local public agencies and economic associations. Furthermore, while persons finding jobs through SHRCs enabled to work for less than 20 hours per a week, the revised act 2015 allow them to work until 40 hours.

The role of SHRCs is highly valuable for the social integration of retirees. However, the work provided through the SHRC should not be in competition with services provided at the market, it should not lead to unfair competition, e.g. in the area of gardening, housekeeping, etc). Setting-up local competition councils with representatives of the local economy and social partners would be an option to avoid unfair competition. A close cooperation with Hello Work would be advisable in order to provide jointly labour market and social integration services.

Summary and recommendations

A mixed picture emerges of the skills of older people in Japan. In comparisons with other OECD countries, they have strong literacy and numeracy skills but weak problem-solving skills in a technology-rich environment. The proportion of both younger and older Japanese with a university-level education is quite low. There is also some evidence of a large decline with age in the literacy and numeracy skills of Japanese people. Japan faces a number of challenges. First, Japanese adults skills are underutilised at work representing a loss of learning opportunities as well as a loss of potential productivity gains. Second, Japan’s system of lifelong learning is less well developed than in many other OECD countries, hindering job prospects of older workers. Finally, older low-skilled Japanese workers are at a particular disadvantage with respect to training and there are strong inequalities in access to training between regular and non-regular workers.

At the same time, there is a pressing need to improve the quality of job matches for older jobseekers, who often move into low skilled, low-paid and insecure jobs after retiring from their main job. In particular more can be done to provide tailored and well‑coordinated employment services.

Box 3.4. Key Recommendations

Raise awareness among employers about the value of experience and productivity of older workers as in other OECD countries. This would also include raising awareness of the importance of work organisation and the learning environment.

Encourage firms to do more to identify training needs of mid-career and older workers through mid-career interviews and as part of regular performance reviews.

Strengthen JEED’s role in providing firms with lifelong learning counselling combined with other age management tools in order to promote training activities for those aged 45 and above.

Improve information on current and future skills needs through regular skills assessment and anticipation exercises at company, industry, local and national levels.

Develop further the recognition and certification system of prior learning acquired at work as well as a qualifications framework. This would help to standardise training and make it more transferable between companies for workers of all ages. A qualification framework would help achieve this and both actions should be carried out in partnership with employer and worker representatives.

Make Job Card obligatory for employers when requested by employees at the time of mandatory retirement. This will allow for recognition of skills and experiences and as a result improve their transition of older workers to better matched jobs.

Set stronger incentives for employers to invest in training and to include social partners for the implementation of a lifelong learning strategy. In particular, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have few resources for workforce development and lack instruments to identify their skills needs. Thus, government support for training, in particular of non-regular workers and targeted at SMEs, should be leveraged up.

Provide training in transversal skills irrespective of age. This includes investing in ICT skills as well as in soft skills for all age groups.

Strengthen training in entrepreneurship. This would help to promote entrepreneurship as an alternative employment opportunity for older workers through targeted courses for them. Ideally, it would start early on with entrepreneurship education provided in schools and universities.

Build a statistical profiling tool to help caseworkers at Hello Work diagnose employability of jobseekers, and to assist in prescribing the type, intensity and duration of services needed to get them back to work in a more systematic way and overcome any age stereotypes.

Develop a comprehensive assessment of potential employment barriers including detailed information on people’s skills, work history, health status, household circumstances and incomes as recommended in OECD Project on Faces of Joblessness. This would contribute to a better match between individual needs of older workers and available support to help them make successful job transitions.