Turkey has strengthened its regulatory framework for environmental management. However, institutional capacity constraints impede more effective implementation of environmental law and the uptake of good regulatory practices. More needs to be done to enhance environmental democracy. This chapter analyses Turkey’s environmental governance system, including horizontal and vertical institutional co‑ordination, and setting and enforcing environmental requirements. It also addresses public participation in decision-making and access to environmental information, education and justice.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019

Chapter 2. Environmental governance and management

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

2.1. Introduction

Turkey has strengthened its environmental regulatory framework since 2008. This progress is primarily due to continued efforts to harmonise environmental legislation with directives of the European Union (EU) as part of the accession process. Progress in implementing EU standards and best practices has been better in some areas (e.g. environmental impact assessment and permitting) than in others (e.g. compliance monitoring and liability). However, the country’s ambition to upgrade and modernise its environmental regulation is commendable and should be pursued further.

At the same time, according to the World Bank 2016 Worldwide Governance Indicators, Turkey’s scores on all measured parameters – accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption – had deteriorated since 2011 (World Bank, 2018). This trend has undoubtedly had ramifications for the country’s environmental governance, particularly environmental democracy.

2.2. Institutional framework for environmental governance

Turkey has a distinctly centralised governance system with ministries playing a strong executive role at the central and provincial level. The 81 provincial administrations represent the decentralised organs of central government authorities (in addition, several ministries have regional directorates). The central government appoints provincial governors. Provincial directors representing ministries are formally subordinated to the governors, but responsible to the minister for execution of sectoral policy.

Turkey has about 1 400 municipalities, including 30 metropolitan municipalities (which are also provincial centres), 51 non-metropolitan provincial centres, over 900 district municipalities and about 400 town municipalities. The law establishes a relation of tutelage between metropolitan and district municipalities within the same province. In non-metropolitan provinces, there is one-tier local government: all municipalities in these provinces have the same organisation, functions and powers. About half of municipal budget revenues comes from the central treasury; the other half is raised primarily through user fees on municipal services.

2.2.1. Central government and horizontal co‑ordination

In 2011, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry was divided into two separate ministries: Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (MEU) and Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs. The MEU is in charge of environmental regulation, environmental impact assessment (EIA), permitting and inspections. In 2018, the Ministry of Forestry and Water Affairs was merged with the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock to form the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF).

The MEU determines and oversees almost the entire workload of its 81 provincial directorates. Although these directorates are part of provincial administrations, their staff are employed by the MEU. The ministry has started to develop performance indicators for its activities. However, so far there are very few such indicators, and all of them are focused on activities rather than their results.

Water-related competencies are divided between the MEU and the MAF. The MEU oversees wastewater management, monitors and controls water pollution. The MAF is responsible for river basin management, protection of water resources, water quantity management, and ambient water quality monitoring.

Other ministries also have environment-related responsibilities. The Ministry of Health oversees the protection of drinking and bathing water quality in collaboration with the MEU. The Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources is, among other competencies, responsible for energy efficiency and renewable energy policies. In addition to its water-related responsibilities, the MAF oversees biodiversity protection, natural parks and forest management, and promotes good land management and agricultural practices.

Environmental boards are the main mechanism of horizontal co‑ordination. Until recently, the Supreme Environmental Board, chaired by the MEU, promoted integration of environmental considerations into economic decisions and arbitrated disputes regarding environmental matters that concern more than one ministry. However, it was disbanded in August 2018. Its inter-ministerial co-ordination function has been transferred to the President and the Presidential Council for Local Administration Policies.

Local environmental boards, chaired by the provincial governor, co‑ordinate implementation of environmental policies at the provincial level. They convene every three months and send their decisions to the MEU and other relevant institutions. Representatives of trade unions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and academic and scientific institutions are invited to these meetings on an ad hoc basis.

A Water Management Co‑ordination Board (WMCB) at the ministerial/vice-ministerial level was established by the Prime Minister’s ordinance in 2012. It is chaired by the MAF and includes key stakeholder ministries. It is supposed to determine national water policies, but had met only four times as of early 2018. There are also river basin councils chaired by a governor of one province within the basin and provincial water management councils chaired by the provincial governor. Both provincial and river basin councils report to the WMCB (Chapter 5). The membership of water management councils largely overlaps with that of environmental boards.

The July 2018 decree law transferred the responsibilities of most co-ordination and advisory boards established under ministries or other public institutions to newly created presidential councils. These councils are chaired by the President, who also appoints their members. The Council for Local Administration Policies is responsible for “developing policy and strategy recommendations for efficient environmental management”. However, implications of this reform on local environmental boards remain unclear. The MEU may need to create another mechanism to better align environmental and sectoral policies, such as those related to climate and energy.

The National Sustainable Development Commission, established in 2004, does not meet often. It includes only the MEU, the Strategy and Budget Office of the Presidency (former Ministry of Development) and ministries of Foreign Affairs and Interior, and does not have a clear operational role (Chapter 3). The government plans to expand the commission’s institutional membership and specify its responsibilities in a new regulation.

2.2.2. Municipalities

The core responsibilities of municipalities are planning, development control and promotion, and provision of public services (including transport, water supply and sanitation, and non-hazardous solid waste management). Metropolitan municipalities oversee land-use plans of district municipalities in the same province, as well as water supply and sanitation in both urban and rural areas across the province. In other provinces, Special Provincial Administrations oversee water supply and sanitation in rural areas, and smaller municipalities – in urban areas (Chapter 5). With regard to waste management, district municipalities are responsible for collecting waste, while its treatment and disposal are under the remit of metropolitan municipalities. In provinces without metropolitan municipalities, district municipalities are increasingly pooling resources through waste management unions, in line with good international practices.

The MEU delegates the power of inspection on noise, construction and demolition waste and residential air pollution to metropolitan municipalities if they have environmental inspection units. The municipalities of Istanbul, Kocaeli, Mersin and Antalya have been delegated powers to control marine pollution from ships.

2.3. Setting of regulatory requirements

Environment Law No. 2872 (1983), substantially amended in 2006, is Turkey’s main environmental statute. There are more than 50 regulations (by-laws) under the Environment Law, including Water Pollution Control Regulation (2004), Regulation on Management of Surface Water Quality (2012), Regulation on the Control of Industrial Air Pollution (2009, revised in 2014), and Regulation on Waste Management (2015). Turkey has aligned its surface water quality standards with EU ones, and plans to do the same for ambient air quality standards by 2024. Following a recommendation of the 2008 EPR, a new comprehensive Water Law based on a holistic watershed management approach has been prepared and is pending approval in parliament. It is also expected to clarify institutional responsibilities in the water domain (Chapter 5). Turkey has also adopted regulations on energy performance of buildings (2008, amended in 2013) and on energy efficiency (2011). These make an important contribution to its energy efficiency policies (Chapter 4).

Most regulatory changes over the review period have been driven by the strategy of approximation with legislation of the European Union after the environment chapter of EU accession negotiations was opened in December 2009. The EU Integrated Environmental Approximation Strategy for 2007-23 was last updated in 2016. This legal harmonisation process is in line with a recommendation of the 2008 EPR. However, Turkey has yet to align completely with directives on air and water quality, waste management and industrial pollution (EC, 2016). Despite the uncertainty of Turkey’s EU accession process, aligning the country’s legislation with best international practices needs to continue.

2.3.1. Regulatory and policy evaluation

Turkey introduced regulatory impact analysis (RIA) in 2006. It carries out RIA only for laws and decree laws (promulgated by the government and then approved by parliament), but not for regulations. According to the 2007 RIA guidelines, the analysis should consider potential impacts on air, water and soil pollution, land-use change, loss of biodiversity and climate change. If a regulation’s total potential impact is estimated at less than TRY 30 million, only partial RIA is undertaken. In principle, the full RIA includes cost-benefit analysis (this rarely happens in practice) and evaluates the draft law’s economic, social and environmental impacts more in-depth than in a partial RIA. It also includes stakeholder consultations. Turkey does not conduct ex post evaluation of legislation or policies.

A regulation on strategic environmental assessment (SEA) entered into force in April 2017. SEA is supposed to be conducted by the authority developing the plan or programme. It targets agriculture, coastal zone management, forestry, fisheries, energy, industry, transport, waste and water management, telecommunications, tourism and land-use planning. For several of these sectors (e.g. waste management and energy), implementation has been deferred until 2023. However, even for sectors subject to SEA as of 2017, the regulation has yet to be implemented. So far, Turkey has only carried out several donor-funded pilot projects and prepared an SEA manual. The government complains it lacks institutional capacity to implement the SEA regulation (MEU, 2016).

2.3.2. Environmental impact assessment

Turkey introduced EIA in the Environment Law, but the first regulation implementing this instrument went into force in 1993. The latest regulation on its administrative and technical procedures was adopted in 2017. The EIA system is mostly in line with EU EIA Directive 2014/52/EU. An online electronic system for EIA documentation was put in place in 2013, significantly simplifying the procedure.

However, Turkey is not party to the Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context and has no legal provisions in this matter. Several OECD Council acts also recommend EIA as a key tool to address transfrontier pollution.1

According to the EIA regulation, Annex 1 projects (major infrastructure and industrial developments) are subject to mandatory EIA, conducted by the MEU’s central office. Annex 2 projects (with a potentially smaller environmental impact) undergo screening by the MEU’s provincial directorates. In practice, only 1.5% of over 55 000 EIA screenings between 1993 and 2016 resulted in a decision to require an EIA. Some facilities operating as of June 2013 are exempted from the EIA regulation (Roy, 2015). In addition, a September 2016 law allowed waivers for licensing and other restrictions for “strategically important” investment projects (EC, 2016).

Following an EIA, a positive or negative decision is issued by a commission comprising representatives of ministries with competencies over the project and of the local municipality. Only 1% of about 4 500 EIAs between 1993 and 2016 received a negative decision. A positive EIA decision refers to measures for mitigating expected environmental impacts in the EIA report, but there is no effective mechanism to ensure their implementation.

Developers must start construction within seven years of a positive EIA decision or within five years if an EIA is not required. A new EIA study is required if the facility increases its production capacity beyond a certain threshold. These long validity periods and limited review requirements reduce the effectiveness of EIA in mitigating environmental impacts.

2.3.3. Permitting

In line with the 2008 EPR recommendation, Turkey has made progress in moving from permitting from individual environmental media to integrated pollution prevention and control (IPPC). According to the 2010 regulation on environmental permitting and licensing (updated in 2014), all facilities are divided into two categories (Annexes 1 and 2) based on the degree of potential impact. Annex 1 facilities receive their permits from the central office of the MEU; Annex 2 facilities receive theirs from the MEU’s provincial directorates.

The regulation introduced a single online environmental permit (for air emissions, wastewater discharges, noise and waste recovery and disposal) for Annex 1 and 2 facilities, based on an electronic application. However, this consolidated permit is not based on best available techniques (BAT) and tends to favour end-of-pipe pollution control over process-oriented solutions. Emission and effluent limit values in permits are set based on sector-specific standards, and rarely consider ambient air quality and quality of receiving water bodies, respectively. An environmental permit is valid for five years. Over 14 000 such permits were issued in 2010-15.

In a peculiar feature of Turkey’s environmental permitting regime, a temporary operation certificate (TOC) – a pre-permit valid for up to one year – can be approved. Applicants for a TOC must have cleared requirements for an EIA or an Environmental Monitoring and Management Programme. The rationale behind the TOC is to provide real pollution data from the operating installation as an input for the permit application process. A TOC cannot be appealed by the public (IMPEL, 2016). A TOC in effect allows operation of a facility without an environmental permit, which is inconsistent with good international practice.

In addition to a consolidated permit, permits for other environmental impacts may be needed. For example, operators discharging wastewater into the sewerage system require a wastewater connection certificate from the competent municipal body. Municipalities determine standards and permitting requirements for wastewater connection certificates and their validity terms.

A hazardous waste storage permit must be obtained from the MEU; a licensed waste management company must collect such waste at least once every six months. This permit is valid for the facility’s lifetime unless its operation is expanded. Generators that produce less than 1 000 kg of hazardous waste are exempt from this permit.

With respect to the EU accession process, Turkey had deadlines for transposing, partially implementing and fully implementing the Industrial Emissions Directive (2010/75/EU) for 2012, 2015 and 2018, respectively. The National Action Plan for EU Accession Phase 2 (2015‑19) makes transposing the acquis in the field of industrial pollution control and risk management a priority. A regulation on IPPC was planned for publication by the end of 2018. It would cover an estimated 6 000 installations, primarily in the chemical industry, production and processing of metals and minerals, and waste management. Most heavy industry is located in Istanbul, Kocaeli, Izmir and Hatay provinces.

The first IPPC permits are expected to be issued in 2024. Emission/effluent limit values would be set in accordance with BAT Conclusions specified in the EU Commission Implementing Decision 2017‑1442. Turkey is planning to apply the high-end (least stringent) of the value ranges for emission/effluent levels specified in the EU decision.

2.3.4. Land-use planning

Turkey has made only limited progress in implementing the recommendation of the 2008 EPR to integrate environmental concerns into all levels of land-use planning. All spatial plans in Turkey should be in line with development plans, which weakens their environmental dimension. The Strategy and Budget Office of the Presidency prepares a National Development Plan in co-operation with the Ministry of Treasury and Finance, while the 26 regional development agencies produce regional development plans.

According to a 2011 decree law, the MEU is supposed to elaborate a national spatial strategy plan, but the work on it started only in 2018. Territorial development plans (TDPs) can be prepared at different scales and in different geographical borders. At the provincial level, they are prepared by the metropolitan municipality or, in non-metropolitan provinces, by the MEU. TDPs cover the country’s entire territory and determine land-use decisions such as settlements, housing, industry, agriculture, tourism and transportation.

TDPs are expected to protect environmentally sensitive areas. They are particularly important in Turkey’s coastal zones (Chapter 4), where the main challenges are increasing pressure of urban settlements, poor environmental awareness in their development and marine pollution, as well as jurisdictional overlaps in planning and management. At the end of 2017, integrated coastal zone plans (ICZPs) covered 82% of coastal zones. The remaining ones are expected to be completed by the end of 2023.

At the local level, zoning plans and implementation plans are made by municipalities or by special provincial administrations for areas cutting across municipalities. The MEU controls the development of zoning plans through its provincial directorates. Territorial development plans are (in theory, but not yet in practice) subject to SEA. However, zoning and implementation plans are not creating an important gap.

2.4. Compliance assurance

Compliance assurance covers the promotion, monitoring and enforcement of compliance, as well as liability for environmental damage. Most compliance assurance activities are conducted by the MEU’s provincial directorates. The police and gendarmerie also have the power to detect environmental crimes and misdemeanours and forward the respective cases to prosecutors or the MEU.

2.4.1. Environmental inspections

Environmental inspections are governed by a 2008 regulation. Integrated (combined) inspections are conducted for high-risk sites, while medium-based inspections are carried out for lower-risk sites. The regulation does not define minimum inspection frequency for any type of installation.

Turkey started developing a risk-based approach to inspection planning, consistent with good international practices, in 2013. The risk assessment of a facility is based on its environmental impacts and compliance record and results in a score that determines the frequency of inspection. Risk-based planning had been implemented in 22 provinces as of early 2018; it is expected to be extended to 12 more provinces in 2019 and to the entire country by 2023.

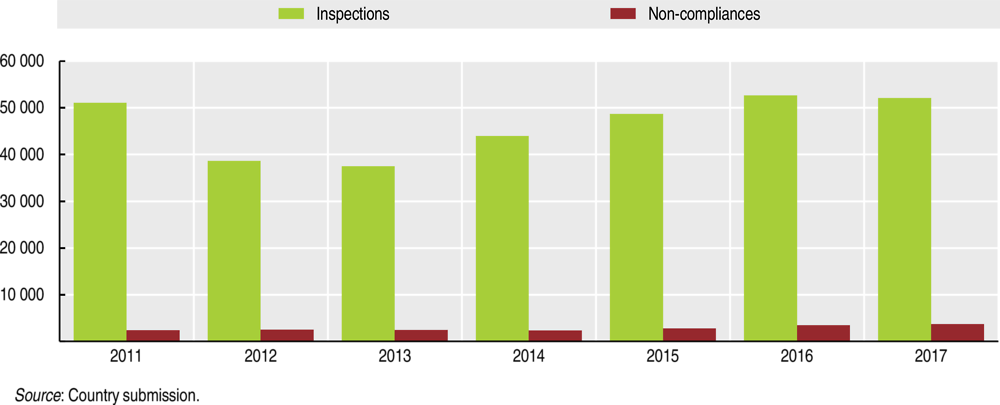

The number of inspections rose from about 37 500 in 2013 to 52 600 in 2016 after a decrease caused by the split of the environment ministry in 2011 (Figure 2.1). Although the MEU strives to expand risk-based targeting (a slight decline in the number of inspections in 2017 may stem from this), only 20% of resources are dedicated to planned inspections in an annual programme. Complaints triggered more than 16% of inspections. The rest of the inspections were conducted as part of a new permit application or renewal procedure, or in response to accidents (MEU, 2016). Planned combined inspections are announced to operators concerned; other types of inspection are not. The number of complaints, especially online ones, has been growing in recent years (IMPEL, 2016). As a result, responding to complaints is consuming an increasing amount of resources for Turkish inspectors.

Only 7% of inspections detected a violation in 2017. This is low compared to many OECD member countries, but may also signify poor targeting of compliance monitoring. Non‑compliance is highest with waste regulations (21% of cases).

Figure 2.1. Inspection numbers are rising faster than non-compliance detection

A software called “e-inspection” was developed in 2014 to plan, report and evaluate inspections. Consistent with good international practices, it includes inspection checklists, on-site inspection reports, information on sanctions and court cases. Annual inspection reports have been prepared since 2010. Training for inspectors has been expanded, as recommended by the 2008 EPR.

2.4.2. Enforcement tools

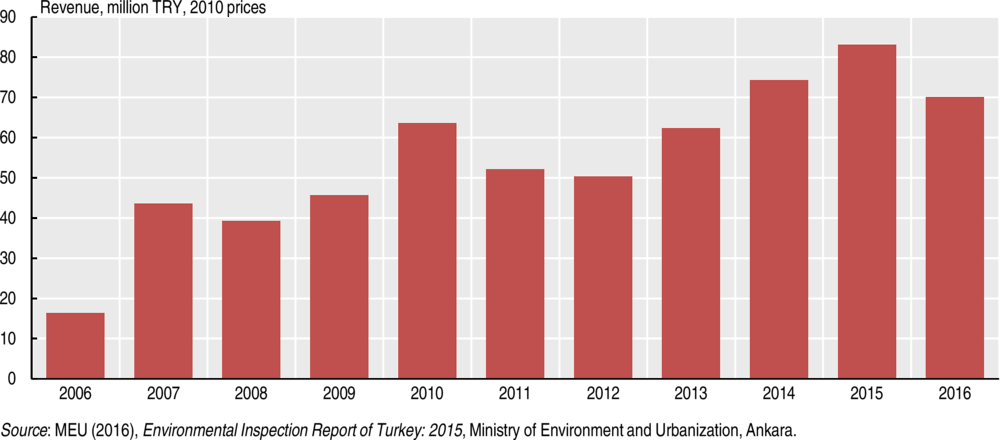

The Environment Law stipulates administrative sanctions (fines and activity cessation orders). The average administrative fine in 2016 was TRY 31 450 (over USD 6 700), which is relatively high compared to other OECD member countries. The amount of fines imposed annually has nearly doubled in constant prices since 2008 (Figure 2.2) because of the increased use of fines and annual adjustment of their rates. The rates increased by 125% over 2008‑18 (by 14.5% in 2017‑18 alone), on par with inflation, thereby maintaining their deterrent effect. Half of the revenue from fines goes to the MEU revolving fund that finances pilot projects, research, training and other ministry expenses; the other half goes to the general government budget.

The size of an administrative fine is set in the law. If the law specifies a minimum and a maximum fine, the actual amount depends on the gravity of the environmental impact. However, the fine does not reflect the operator’s economic benefit from non-compliance. If a facility has started operation without an EIA process, it is shut down permanently, and an administrative fine equal to 2% of its investment value is imposed. Almost 40% of the fines’ volume comes from EIA-related infringements (MEU, 2016). If the infringement is repeated within three years, the fine is doubled.

Figure 2.2. Administrative fines are increasingly used in enforcement

The 2004 Criminal Code defines criminal sanctions for intentional or negligent pollution. The Code provides for imprisonment of between two months and five years for environmental crime, depending on the intent and gravity of the violation. Judges may replace a prison sentence with a fine at their discretion. In 2016, 33 of 204 criminal convictions for environmental offences were imprisonments. The number of prison sentences for environmental crimes has increased significantly since 2010, when only four were delivered (Ministry of Justice, 2017). Criminal sanctions may be imposed on top of administrative ones, which is rare in international practice.

2.4.3. Environmental liability

Liability for damage to the environment

According to the Environment Law, polluters are responsible for environmental damage regardless of any misconduct on their part (i.e. are subject to strict liability). In cases of damage to human health and property, compensation can be claimed in accordance with the Obligations Law. However, environmental liability is limited to five years from the moment of discovery of the damage and cannot be enforced thereafter.

Turkey has few liability provisions for damage to the environment itself. If the responsible party fails to stop pollution or mitigate environmental damage, competent authorities undertake those actions directly and then recover costs from the violator. However, a draft Environmental Liability Law that would create a legal framework for assessment and remediation of damage to soil, water bodies and ecosystems and implement the EU Environmental Liability Directive (2004/35/EU) is still under development. The government has postponed its enactment pending complete transposition of the EU Water Framework Directive, Marine Strategy Framework Directive, Habitats Directive and Birds Directive into Turkish law.

Operators handling hazardous chemicals or wastes are required to obtain liability insurance for bodily damage or loss of third parties, but not for damage to the environment. There is also compulsory insurance for coastal facilities against damage to the marine environment. However, such insurance in Turkey covers only accidental pollution, but not gradual pollution as part of routine operations (Steward, 2010).

Contaminated sites

The Regulation on Controlling Soil Pollution and Point-Source-Polluting Fields of 2010 governs the detection, monitoring and remediation of contaminated sites, including soil and groundwater. All contaminated sites are registered via the online Contaminated Sites Information System, established in 2015. Each potential contaminated site is evaluated. One of 21 accredited firms undertakes any needed clean-up at the polluter’s expense. The clean-up plan must be approved by the MEU. If the responsible party is unknown or financially insolvent, MEU provincial directorates are expected to carry out assessment and remediation. However, there is no planning and no regular budget allocated for remediation of such abandoned sites. Turkey could follow Estonia’s example of earmarking revenues of environmental taxes for this purpose (OECD, 2017). Alternatively, it could impose decontamination fees on hazardous industrial installations and earmark the revenue for a fund to clean up past land and water pollution.

2.4.4. Promotion of compliance and green practices

Compliance promotion does not get the attention it deserves from Turkish environmental authorities. The government offers little guidance, if any, to economic entities on good environmental management practices. At the same time, several green certification initiatives have recently been launched in collaboration between government authorities and the private sector.

Greening public procurement

The integration of environmental aspects into Turkey’s public procurement policies is at a very early stage. Basic environmental compliance is required: if an EIA is compulsory for the activity, a positive EIA decision must be obtained before procurement can begin. In addition, it is possible (but not mandatory) to consider environmental factors as non-price selection criteria. In a positive development, the Ministry of Treasury and Finance has recently issued an instruction for public institutions to consider energy efficiency criteria in purchasing goods or services.

Environmental management system certifications

The Environment Law requires organisations and facilities with a potentially significant environmental impact to establish environmental management units. They must also either have a designated environmental representative (for higher-impact facilities), or procure services from institutions authorised by the MEU. Environmental representatives must prepare monthly environmental reports and an annual internal audit report. These requirements contribute to better corporate environmental management. Over 2010-17, the MEU issued almost 14 000 environmental representative certificates and 300 qualification certificates for environmental management units.

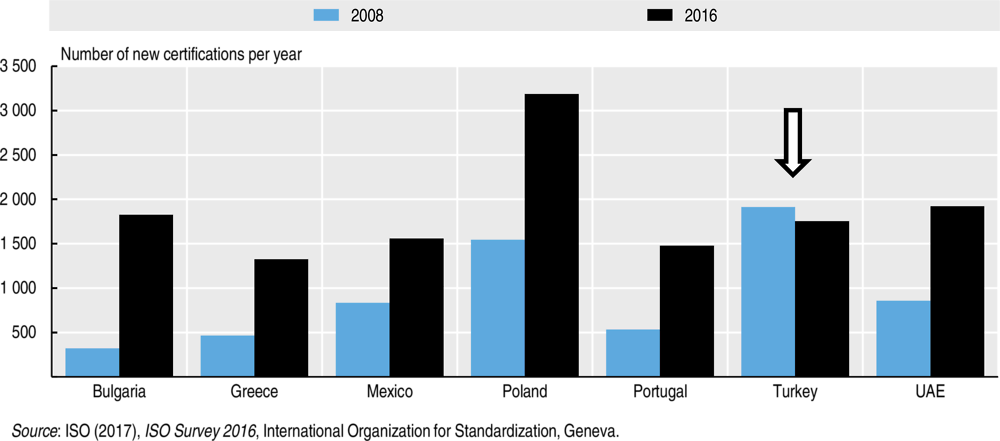

The number of new certifications to the ISO 14001 environmental management system (EMS) standard sharply declined in 2009‑11 due to the economic crisis. Although their number has somewhat recovered, it was still lower in 2016 than in 2008 (Figure 2.3). This certification rate is close to that of Mexico and of European countries with much smaller economies, where EMS certifications have increased considerably since 2008. It is second to that of the United Arab Emirates among Middle Eastern countries (ISO, 2017). The government does not provide any incentives for EMS certification.

Figure 2.3. Turkey lags behind in EMS certifications

A Green Star Certification Programme for environmentally friendly hotels was launched by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in 2008. As of 2018, 443 Turkish hotels had obtained the certificate, which emphasises sustainable water, energy and waste management (Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2018). There are also several green building certification schemes: the Turkish Green Building Council Association governs the “Green Building Certification System”; the Turkish Standards Institute manages the “Safe Green Building Certificate”; and a state university runs “Sustainable Energy Efficient Buildings-Turkey” (Cetik, 2014). The MEU is preparing legislation on a national eco-labelling system modelled after the EU system.

2.5. Promoting environmental democracy

Turkey ranks 47th in the world (next to Guatemala and Bolivia) according to the Environmental Democracy Index (WRI, 2018). It scored particularly low on public participation. Turkey has not signed the Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters. A recent EU accession progress report (EC, 2016) noted Turkish civil society’s complaints with respect to court rulings on environmental issues, public participation (particularly in EIA) and the right to environmental information.

2.5.1. Public participation in environmental decision making

The EIA regulation provides clear opportunities for public participation in site-specific environmental decision making. The EIA process includes a local public hearing. A draft EIA report is published on the Internet or on billboards for comments, which are considered by an evaluation committee charged with evaluating the project. SEA, when implemented (Section 2.3.1), will also be open to the public. However, there is no public participation in the permitting process.

Territorial development and zoning spatial plans, including ICZPs, are prepared through a participatory process that includes on-site information meetings with the involvement of the private sector and NGOs. They are also publicly announced for comments on the MEU website. Public participation in drafting environmental legislation and policies takes place through special consultative committees.

2.5.2. Access to environmental information

The 2003 Law on Right to Information and its 2004 implementation regulation cover access to environmental information held by public institutions. This law explicitly excludes information or documents whose disclosure could “harm economic interests of the state” or “cause unfair competition”. Public institutions have a right to charge fees for “research, copying, postage and other costs” related to information requests. Applicants refused information can appeal to the Review Board on Information Access; if the refusal is confirmed, applicants can appeal again to an administrative court. These appeals are free of charge. However, the law fails to ensure that the review board is independent or impartial (WRI, 2018).

The MEU publishes a state of the environment report every four years. Some additional environmental information is available to the public on the MEU and TurkStat websites and the e-government portal. The use of recently created electronic information management systems (for EIA, waste management, etc.) is expected to enhance data access. However, only synthesis reports rather than original data would be made public. Furthermore, the government is not obliged to make relevant and timely information available to the public during environmental emergencies (WRI, 2018).

Despite several EU-funded pilot projects since 2005, Turkey has not yet established a pollutant release and transfer register (PRTR) (Chapter 1).2 It has committed to creating a PRTR only upon accession to the EU, citing resource constraints. Privately held environmental information is not publicly accessible.

2.5.3. Access to justice

Judicial review on environmental matters is conducted by civil courts for matters of liability and compensation, and by administrative courts for administrative decisions. There is restricted standing for the public and NGOs to bring environmental claims to court. The Council of State (top administrative court) has stipulated that a person must have “legitimate, actual and personal” interest to sue in an administrative court. Class action suits on environmental matters are not possible in Turkey, and the public cannot challenge decisions by private actors that affect the environment.

Environmental NGOs usually act through the courts. They have brought legal actions to invalidate environmental permits granted to major projects (e.g. gold mines, highways, power plants and dams). In recent years, the government has started to co‑operate with NGOs to benefit from their environmental expertise (Mavioglu et al., 2017). However, no legal assistance is available to the public or NGOs in their pursuit of environmental justice.

The 2013 Law on the Ombudsman established an independent Ombudsman Institution under the auspices of parliament. This office audits the performance of government agencies and investigates complaints against administrative decisions, publishing reports about both. However, it has not been active in the environmental domain.

2.5.4. Environmental education

The tenth Development Plan (2014‑18) aims to increase environmental awareness through education on sustainable development. A protocol signed in 2014 between the MEU and the Ministry of National Education calls for information dissemination and awareness-raising activities for students, teachers and parents. It also introduced a “Turquoise Flag” award for schools with best environmental performance (particularly with respect to energy efficiency and waste management). The new curriculum announced in 2017 by the Ministry of National Education integrates environmental aspects into science and social studies courses of the primary and secondary education curricula. A textbook for a dedicated (albeit elective) environmental education course for grades seven and eight was developed in 2018.

The MEU has provided an “Environment Handbook” covering waste management, air quality, water pollution and climate change to all primary and secondary school students (its third edition was published in 2010). Over 50 000 environmental awareness booklets were published and disseminated in 2012‑13. Since 2015, almost 480 000 posters on waste management, pollution prevention and sustainable use of natural resources have been distributed to over 61 000 schools and 15.7 million students by MEU provincial directorates. In addition, the Ministry of National Education, MEU and Regional Environmental Centre (with donor support) jointly carried out the Green Pack project. This included publishing a variety of environmental educational materials such as a teacher’s handbook.

Recommendations on environmental governance and management

Institutional and regulatory framework

Strengthen the role of environmental boards in horizontal co-ordination of environmental aspects of energy, transport and other sectoral policies; reinforce the National Sustainable Development Commission and expand its institutional membership.

Implement the regulation on SEA for public plans and programmes, including all local spatial plans, and build related institutional capacity; expand regulatory impact analysis to secondary legislation and ensure consideration of potential environmental impacts of all regulatory proposals; introduce ex post evaluation of policies and legislation.

Strengthen the EIA system by systematically reflecting identified impact mitigation measures in environmental permits and implementing EIA in a transboundary context.

Make best available techniques the basis for setting conditions in environmental permits for high-risk installations; phase out temporary operation certificates.

Compliance assurance

Implement risk-based planning for environmental inspections in all provinces and define minimum inspection frequencies for different categories of installations.

Adopt legislation to impose strict liability for damage to soil, water bodies and ecosystems and establish appropriate remediation standards; create a fund for remediation of abandoned contaminated sites.

Use different information channels to deliver advice and guidance on green practices to the business community; expand sector-specific green certification programmes; establish binding environmental criteria for public procurement.

Environmental democracy

Enhance mechanisms for public participation in drafting environmental legislation, policies and programmes, as well as in the permitting process.

Remove restrictions and fees for access to environmental information held by public institutions; give the public access to environmental permits and compliance records using recently created electronic information systems; establish a PRTR open to the public.

References

Cetik, M. (2014), “The governance of standardisation in Turkish green building certification schemes”, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2435160.

EC (2016), Turkey 2016 Report, Commission staff working document SWD(2016) 366 final, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2016/20161109_report_turkey.pdf.

IMPEL (2016), A Voluntary Scheme for Reporting and Offering Advice to Environmental Authorities, European Union Network for the Implementation and Enforcement of Environmental Law, Brussels, www.impel.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/FR-2016-22.1-IRI-Turkey.pdf.

ISO (2017), ISO Survey 2016, International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html.

Mavioglu, O.Y. et al. (2017), Environmental Law and Practice in Turkey: Overview, Thomson Reuters, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/7-522-2040?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true&bhcp=1.

MEU (2016), Environmental Inspection Report of Turkey: 2015, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara, www.csb.gov.tr/db/ced/editordosya/INSPECTION_REPORT_2015_ENG.pdf.

Ministry of Culture and Tourism (2018), “List of environmentally friendly hotels certified according to the communique on issuance of Environmentally Friendly Hotel certificate” (in Turkish), Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Ankara, http://yigm.kulturturizm.gov.tr/TR,9579/turizm-tesisleri.html.

Ministry of Justice (2017), Judicial Statistics 2016, General Directorate of Judicial Record and Statistics, Ministry of Justice, Ankara, www.adlisicil.adalet.gov.tr/AdaletIstatistikleriPdf/Adalet_ist_2016.pdf.

OECD (2017), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Estonia 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268241-en.

OECD (2008), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.sourceoecd.org/environment/9789264049154.

Roy, M. (2015), “Turkey: New environmental impact assessment regulation: Essential information for all new projects”, Gide Loyrette Nouel, www.gide.com/fr/actualites/turkey-new-environmental-impact-assessment-regulation-essential-information-for-all-new (accessed 2 February 2018).

Steward, M. (2010), “Sea pollution liability insurance in the EU and Turkey”, presentation at the conference on the implementation of coastal facilities, Istanbul, 19 October 2010, www.tsb.org.tr/images/Documents/Marcel_Steward.ppt.

World Bank (2018), Worldwide Governance Indicators website, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/WGI/index.aspx#reports (accessed 27 April 2018).

WRI (2018), Environmental Democracy Index: Turkey, World Resources Institute website, www.environmentaldemocracyindex.org/country/tur (accessed 4 January 2018).

Notes

← 1. OECD Council Acts C(74)224, C(77)28/FINAL and C(78)77/FINAL recommend that member countries harmonise their environmental policies with a view to solving transfrontier pollution problems based on the principles of equal right of access and non-discrimination, exchange of information and consultation.

← 2. A 2018 OECD Council Recommendation recommends that OECD member countries establish and maintain a PRTR.