To address the challenge of rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), Japan has increased the focus on primary prevention. The Health Japan 21 strategy provides a nation-wide framework to improve population health through interventions in workplaces, schools and local communities, focusing on diets, physical activity, smoking cessation and alcohol consumption. However, there exists a wide diversity in approach and focus among the isolate local initiatives, and there are few mechanisms to ensure quality or to disseminate successful practices. In addition, Japan should consider implementing population-level policies to support the impact of local interventions by creating a health promoting environment, such as banning smoking in public places, regulating food, tobacco and alcohol advertising, restricting alcohol sales, and labelling of tobacco, alcohol and food products with warning labels.

OECD Reviews of Public Health: Japan

Chapter 2. Primary prevention and the Health Japan 21 strategy

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

2.1. Introduction

The rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is increasing the burden on health systems throughout the world. While some risk factors are less prevalent in Japan, Japan too is seeing the impact of overweight, smoking, alcohol and other behaviours on the burden of disease. Moreover, considerable disparities between prefectures create an additional challenge.

To tackle these issues, Japan has increased its focus on primary prevention. The Health Japan 21 strategy provides a nation-wide framework to improve the health of the population through interventions in workplaces, schools and local communities. It sets targets for a wide range of indicators to increase accountability and monitor progress. Key areas of activity are healthy diets, physical activity, smoking cessation and alcohol consumption, but there exists a wide diversity in approach and focus among the separate local initiatives.

Yet while the reach of the Health Japan 21 strategy and the dedication of the local interventions are impressive, there remain areas where Japan can step up its action. In particular, population-level policies can support the impact of local interventions by creating a health promoting environment.

This chapter first explores the population health trends and challenges that Japan is facing. It then describes Japan’s primary prevention strategy, with a focus on the Health Japan 21 strategy. Examples are given of the prevention programmes implemented by local communities, workplaces and schools. Finally, this chapter provides recommendations for further action that can be taken by Japan to create a health promoting environment through population-level policies.

2.2. Japan faces a range of public health challenges, including smoking, overweight and alcohol consumption

2.2.1. Changing lifestyles are having an impact on population health in Japan

Like many other OECD countries, the health care challenge that Japan is facing due to an aging population are compounded by changing lifestyles. These changes have an impact on the burden of disease, increasing the prevalence of conditions such as cancer, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiovascular disease and dementia (see also chapter 1). Some of the most important risk factors contributing to this burden of disease are smoking, overweight and obesity, and alcohol consumption.

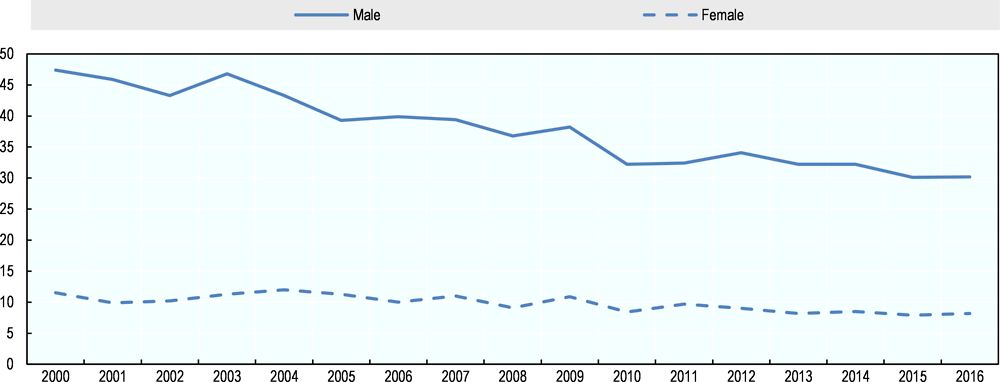

Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body, and causes many diseases including cancer, COPD, heart disease and stroke. Despite a downwards trend in smoking prevalence over the past 15 years, 30% of Japanese men smoke, which is higher than most OECD countries (see Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2) (OECD, 2018[1]). However, only a small proportion of Japanese women smokes compared to other OECD countries. This rate has remained largely stable over the past years.

Figure 2.1. Prevalence of smoking in Japan compared to other OECD countries

Figure 2.2. Smoking prevalence in Japan over time

In addition to differences by gender, smoking rates also differ across socio-economic classes. Studies have shown that people of both sexes in the highest income group are less likely to smoke that people in lower income groups (Fukuda, Nakamura and Takano, 2005[2]). However, while men in non-urban areas smoke more, women in urban areas are more likely to smoke than those living in non-urban areas.

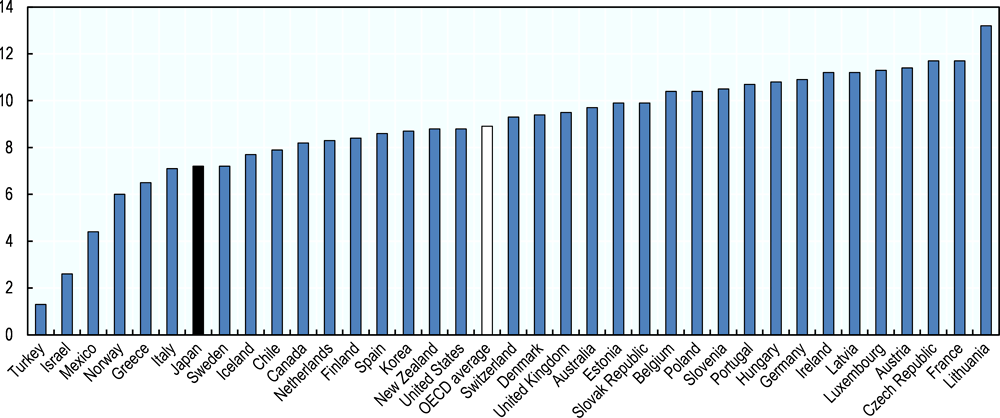

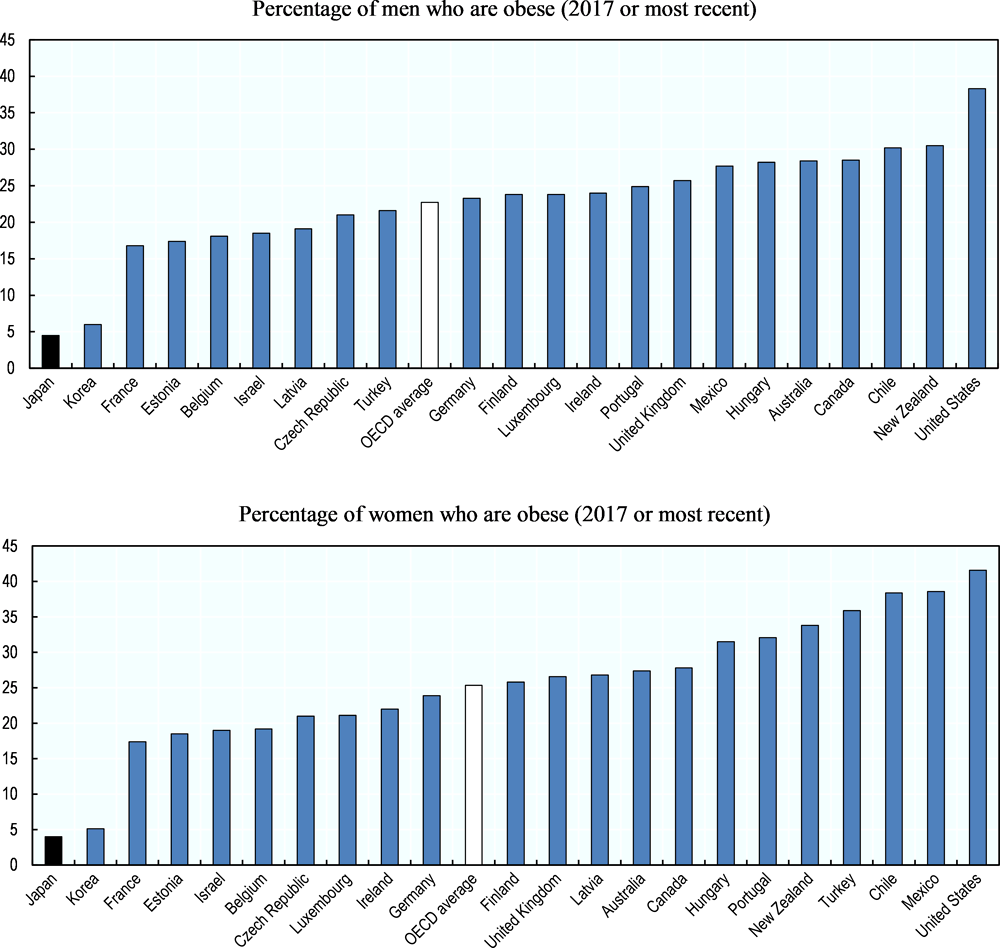

Japan has a very low obesity prevalence compared to other OECD countries (see Figure 2.3). Only 4.5% of men and 4.0% of women are obese according to international standards (OECD, 2018[1]). However, the prevalence of obesity defined as having a BMI of 30 or more may not be an appropriate measure for the Japanese population. Studies have shown that at lower BMI Japanese and other Asian ethnicities have relatively high percentages of body fat, as well as a higher risk of diabetes and heart disease (WHO expert consultation, 2004[3]). For this reason, the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity (JASSO) defines obesity for Japanese as having a BMI of 25 or more.

Figure 2.3. Prevalence of obesity in Japan compared to other OECD countries

Note: Only countries with a measured obesity prevalence, rather than self-reported, were included. These figures define obesity as a BMI of 30 or high.

Source: OECD Health Statistics 2018, https://doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

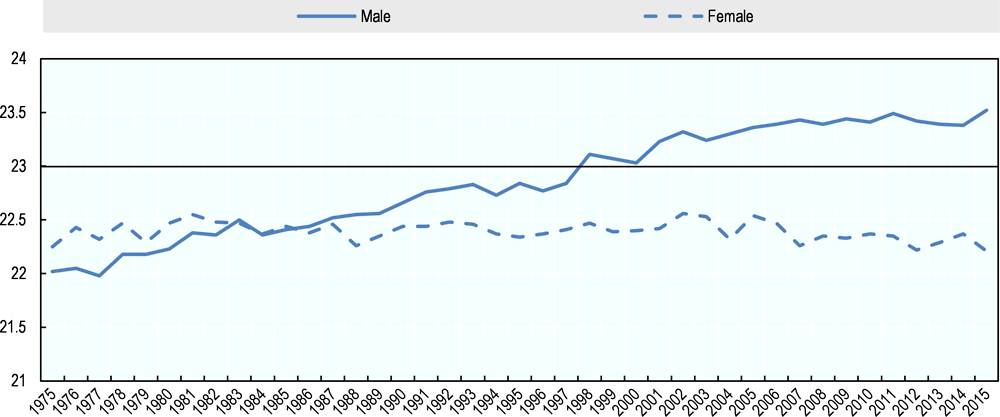

Instead of only looking at obesity, it is recommended to also consider other BMI cut-offs as trigger points for public health action (WHO expert consultation, 2004[3]). A BMI higher than 23 is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in Asian populations and is considered a trigger point for public health action. Data shows that over the last 40 years, the BMI of men has increased by 1.5 points, and the current average BMI is 23.5 in Japan. Notably, BMI of women has remained largely stable over that same time, at around 22.4.

Figure 2.4. Average BMI in Japan over time

Note: Increased risk at BMI=23 is based on the trigger point for public health action in Asian populations, WHO expert consultation (2004[3]).

Source: National Health and Nutrition Survey, via the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2017[4]), Health Japan 21 (the second term), http://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/kenkounippon21/en/.

The prevalence of overweight is more common among older people in Japan. While only 11.3% of people aged 20 to 29 have a BMI of 25 or more, this percentage is 19.4% in 30-39 year olds and around 25% in people over 40 (e-Stat, 2014[5]). For women, the highest rate of overweight is for women over 70 years old, at 24.6%, For men, overweight is most prevalent in the age group 40-49, after which it decreases. However, it should be noted that this is a cross-sectional effect, and that studies comparing cohort results over time observed that BMI consistently increased with age (Funatogawa et al., 2009[6]).

Socioeconomic status also creates differences in the distribution of obesity: a study showed that adolescents in low- and middle-income households were more likely to be overweight that those in high-income households (Kachi, Otsuka and Kawada, 2015[7]). Another study looked at the impact of the 2008 economic downturn, and found that boys and girls from low-income households were at a higher risk of being overweight after the crisis (Ueda, Kondo and Fujiwara, 2015[8]).

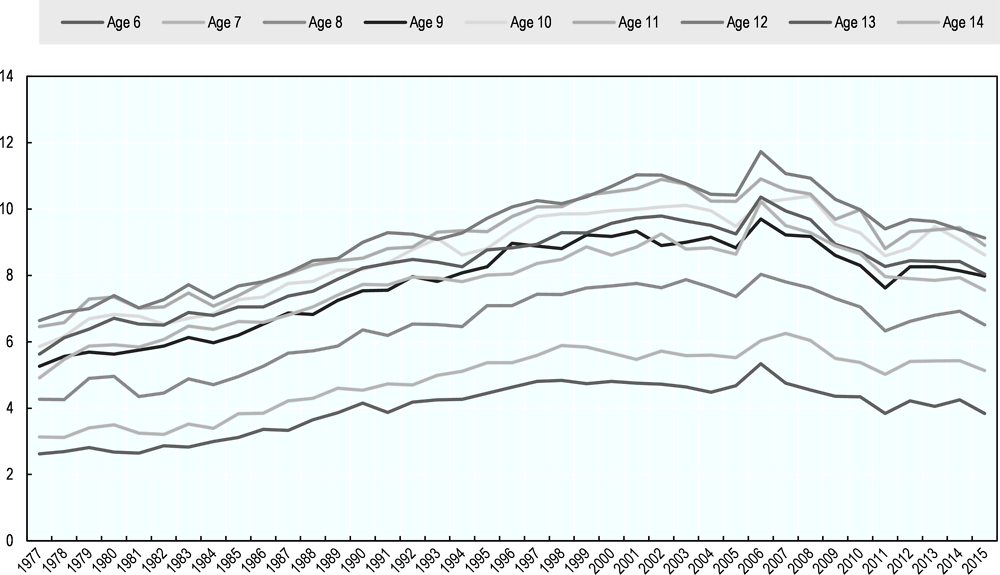

While the prevalence of childhood obesity has decreased in recent years, it remains more prevalent than the decades before (see Figure 2.5). It is important to note however, that obesity in this case is measured as weighing over 20% more than a height-based reference weight. The JASSO does not use BMI to assess obesity in children who are still growing, according to the Clinical Guidelines for Pediatric Obesity 2017. This is a different approach than the BMI cut-off method that is generally used for adult and childhood obesity (de Onis et al., 2007[9]).

Figure 2.5. Childhood obesity in Japan over time

Source: e-Stat (2015[10]), School Health Statistics Survey, https://www.e-stat.go.jp/dbview?sid=0003147100.

While overweight and obesity are becoming more common in Japanese society, social pressures to be thin have led to an increase in underweight among young women (Mori, Asakura and Sasaki, 2016[11]). Nearly 30% of Japanese women between the age 15 and 19 has a BMI below 18.5 (e-Stat, 2014[5]). However, similar to obesity, it is unclear whether this is the appropriate BMI cut-off value when it comes to harmful underweight.

Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of liver disease, cancer, heart disease and mental health conditions. Japan consumes less alcohol than most OECD countries, 7.2 litres on average per capita (see Figure 2.6) (OECD, 2018[1]).

There is a considerable difference between men and women when it comes to alcohol consumption frequency: 28.9% of men drinks every day, compared to only 7.4% of women (Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, 2017[4]). For men, daily consumption of alcohol becomes more prevalent with age, peaking at 38.5% of 60-69 year olds. There are also differences between men and women when it comes to harmful consumption: while 14.6% of men drank at harmful levels1 in 2016, only 9.1% of women do (Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, 2017[4]).

Notably, while in many countries alcohol use is more common in lower economic classes, a survey conducted by the Ministry of Health found that men with a lower income were less likely consume high levels of alcohol. Only 11.5% of men who made less than JPY 2 million (EUR 15 000) per year engaged in harmful drinking, compared to 17% of men earning between JPY 2 million and 6 million, and 15% of men who made more than JPY 6 million (EUR 45 000) (Ministry of Health, 2014[12]).

These differences between sexes and socio-economic classes may in part be driven by the important role that social drinking has in Japanese business and work culture.

Figure 2.6. Alcohol consumption in Japan compared to other OECD countries

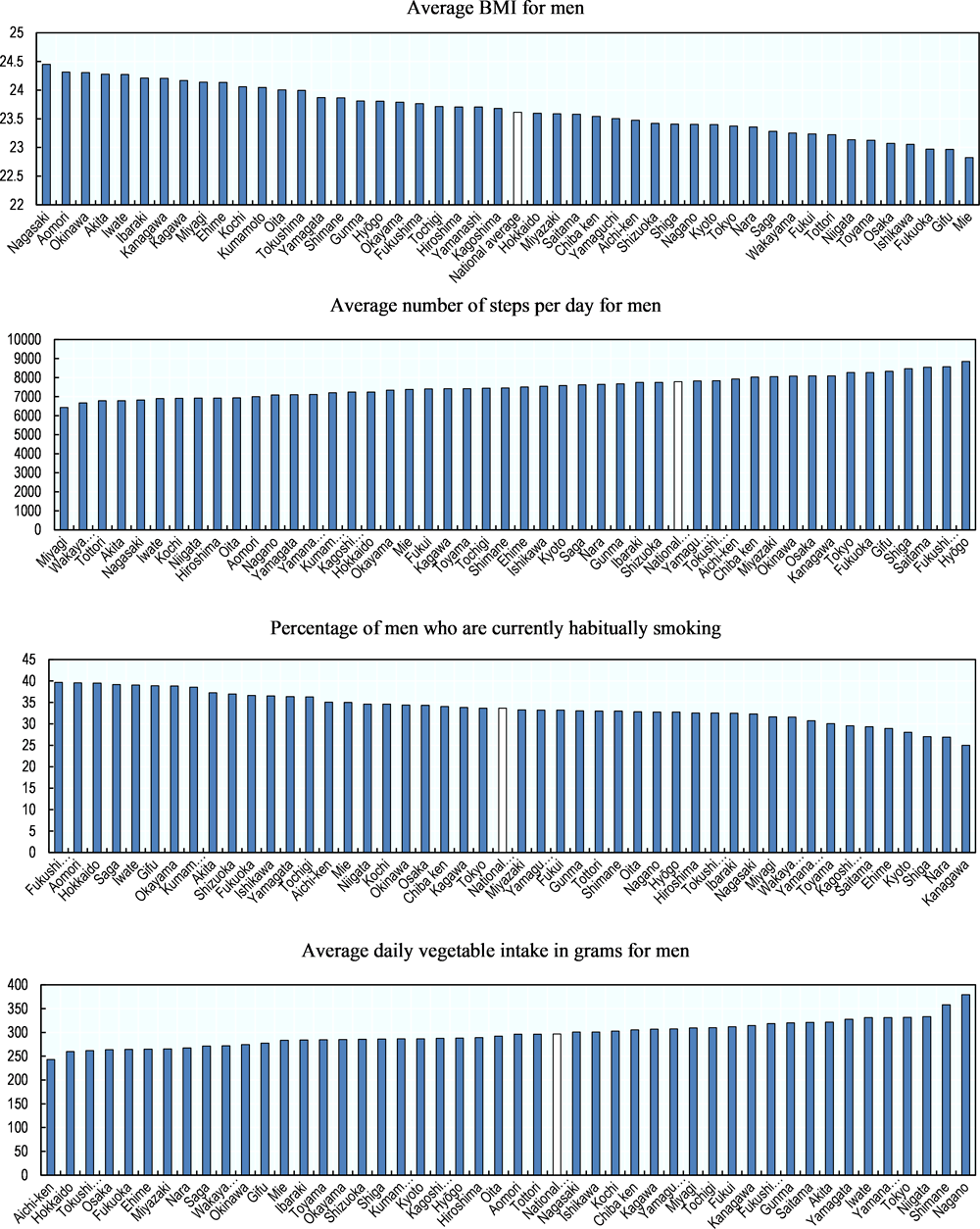

2.2.2. There exist disparities in risk factors between prefectures

The 2012 National Health and Nutrition Survey focused on understanding regional disparities in risk factors and outcomes. Data from this survey shows that risk factors are distributed unevenly across the Japanese population (see Figure 2.7). While men in the Hyōgo prefecture take on average nearly 8 900 steps per day, in Miyagi this is only around 6 400. Nearly 40% of men in Fukushima smoke, compared to only 25% of men in the Kanagawa prefecture. The North experiences a higher mortality that the rest of the country. These differences can be an indication of regional variations in exposure to risks, lifestyles, other socioeconomic or poverty trends, or differences in local public health services (Kanchanachitra and Tangcharoensathien, 2017[13]).

As the health gaps between prefectures had widened over the last 25 years (Nomura et al., 2017[14]), the government has focused on reducing health inequalities as part of the Health Japan 21 strategy. As a result, differences in healthy life expectancy have reduced in recent years: between 2010 and 2016, the gap in healthy life expectancy between prefectures went from 2.79 years for men and 2.95 years for women to 2.00 and 2.70, respectively (Ministry of Health, 2018[15]).

Figure 2.7. Risk factor distribution by prefecture in 2012

Source: e-Stat (2014[5]), National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012, https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&lid=000001118468.

2.3. The Health Japan 21 strategy provides a framework for national, local, workplace-based and school-based health promotion interventions

2.3.1. The Health Japan 21 strategy functions as a framework for primary prevention in Japan

In 2003, Japan implemented the Health Promotion Act, as part of a larger health care reform. This Act provides a framework for primary prevention and overall public health improvement. It lays out the guidelines for the population-wide health checks (see also Chapter 3), implements the National Health and Nutrition Survey to monitor public health and evaluate interventions, and requires facility owners (including schools, hospitals, restaurants, public transport, stores and government offices) prevent passive or second-hand smoking.

The Health Promotion Act also provides a legal basis for the Health Japan 21 (HJ21) strategy, which had been initiated three years prior. The first term of this strategy ran from 2000 to 2012, and its aim was to promote health awareness activities and health promotion efforts, in order to prevent premature death, extend healthy life expectancy, and improve the quality of life.

As part of the first term of HJ21, prefectural governments were required to write and implement health promotion plans for their local population. To guide the development of these plans and measure their impact, 79 targets2 were set in 9 areas (nutrition and diet; physical activity and exercise; rest and promotion of mental health; tobacco; alcohol; dental health; diabetes; circulatory disease; and cancer). These targets focused primarily on intermediary and final outcomes (e.g. decreased salt intake, increased daily steps taken, decreased complications of diabetes), but some process metrics around knowledge and awareness were included as well (e.g. increased use of food labels, increased willingness to diet, increased awareness of metabolic syndrome) (Ministry of Health, 2011[16]).

In the final evaluation of the strategy, it was found that 17% of targets were achieved while an additional 42% showed improvement (Ministry of Health, 2011[16]). The majority of achieved targets were in the area of dental health. Other targets that were achieved were increased awareness of metabolic syndrome, willingness to engage in physical activity, and decreased lack of sleep. However, the remaining targets did not all stay the same: 15% of the metric worsened. There were more diabetic complications, fewer people eating breakfast, fewer steps taken per day, and more stress, among others.

For HJ21’s second term, which runs from 2013 to 2022, a new framework was developed containing 53 targets. While the new framework has a different structure – moving from a disease-based grouping to organisation by overall aim, such as improving risk factors or social engagement – many of the metrics remain the same. However, the updated framework has a greater focus on extending healthy life expectancy and reducing regional health inequalities, includes secondary prevention, and contains new metrics on creating a healthier social environment. The latter includes measures such as the number of corporations, civilian organisations and prefectures that have put in place health promoting measures, and volunteer participation in health promotion.

Yet while this list of tangible targets provides a measurable way to evaluate the strategy, it provides no prioritisation. The targets cover a very wide range of public health issues – with varying urgency and impact on population health – without prioritising them or ranking their relative importance.

Box 2.1. Health Japan 21 Second term – Targets

Note: specific quantitative targets were set for each metric, details of which can be found in Annex 2.A

Targets for achieving extension of healthy life expectancy and reduction of health disparities

1. Extension of healthy life expectancy (average period of time spent without limitation in daily activities)

2. Reduction of health disparities (gap among prefectures in above metric)

Targets for the prevention of onset and progression of life-style related diseases

Cancer

1. Reduction in age-adjusted mortality under age 75

2. Increase in participation rate of cancer screenings

Cardiovascular disease

1. Reduction in age-adjusted mortality rate of cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and ischemic heart disease (IHD)

2. Reduction in average systolic blood pressure

3. Reduction in percentage of adults with dyslipidaemia

4. Reduction in number of definite and at-risk people with metabolic syndrome

5. Increase in participation rates of specified health check-ups and guidance

Diabetes

1. Reduction in complications

2. Increase in percentage of patients who continue treatment

3. Decrease in percentage of individuals with elevated blood glucose levels

4. Prevent increase in number of diabetic persons

5. Reduction in number of definite and at-risk people with metabolic syndrome

6. Increase in participation rates of specified health check-ups and guidance

COPD

1. Increase recognition of COPD

Targets for maintenance and improvement of functions necessary for engaging in social life

Mental health

1. Reduction in suicide rate

2. Decrease in people suffering from mood disorders or anxiety disorders

3. Increase in occupational settings where interventions for mental health are available

4. Increase in number of paediatricians and child psychiatrists

Children's health

1. Increase in percentage of children who maintain healthy lifestyle (eating three meals a day and regular exercise)

2. Increase in percentage of children with ideal body weight (low birthweight and obesity)

3. Health of elderly people

4. Restraint of the increase in Long-Term Care Insurance service users

5. Increase in identification rate of high-risk elderly with low cognitive function

6. Increase in percentage of individuals who know about locomotive syndrome

7. Restraint of the increase in undernourished elderly

8. Decrease number of elderly with back or foot pain

9. Promotion of social participation

Targets for putting in place a social environment to support and protect health

1. Strengthening of community ties

2. Increase in percentage of individuals who are involved in health promotion activities

3. Increase in number of corporations that deal with health promotion and educational activities

4. Increase in number of civilian organisations that offer accessible opportunities for health promotion support or counselling

5. Increase in number of prefectures that identify problems and have intervention programs for those in need

Targets for improvement of everyday habits and social environment

Nutrition and dietary habits

1. Reduction in percentage of obese and underweight individuals

2. Increase in individuals who consume appropriate quality and quantity of food

3. Decrease in percentage of children who eat alone

4. Increase in number of food producers that supply food products low in salt and fat

5. Increase in percentage of specific food service facilities that plan, cook, and evaluate and improve nutritional content of menu based on the needs of clients

Physical activity and exercise

1. Increase in daily number of steps

2. Increase in percentage of individuals who regularly exercise

3. Increase in number of local governments that offer community development and environment to promote physical activity

Rest

1. Reduction in percentage of individuals who do not take rest through sufficient sleep

2. Reduction in percentage of employees who work 60 hours or more per week

Alcohol drinking

1. Reduction in percentage of individuals who consume alcohol over recommended limits

2. Eradication of underage drinking

3. Eradication of alcohol consumption among pregnant women

Tobacco smoking

1. Reduction in percentage of adult smoking rate

2. Eradication of underage smoking

3. Eradication of smoking during pregnancy

4. Reduction in percentage of individuals who are exposed to passive smoking at home, workplace, restaurants, governmental institutions, and medical institutions

Dental and Oral health

1. Increase in percentage of individuals in their 60s with good mastication

2. Prevention of tooth loss

3. Decrease in percentage of individuals with periodontal disease

4. Increase in number of children without dental caries

5. Increase in percentage of individuals who participated in dental check-up

Source: Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (2017[4]), Health Japan 21 (the second term), http://www.nibiohn.go.jp/eiken/kenkounippon21/en/.

2.3.2. The primary role of the central government in HJ21 is setting and monitoring targets, and incentivising action

At the central level, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare is the main actor in the HJ21 strategy. The Ministry leads on the legislative issues and sets the overall framework and targets. Other ministries also play a role, but only in specific elements of the strategy. Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry oversees the Health and Productivity Management (HPM) programme, and the Ministry of Education runs the programmes in schools. Generally speaking, the role of these actors is to set targets and to create guidelines.

Local entities, including prefectures, municipalities, employers, and schools, are expected to implement actions to reach the targets. The prefectural governments write health promotion plans through which they set their own agendas within the overall framework, and tailor their approach to the specific characteristics of the local population and situation. Municipalities are the main actors responsible for implementation, through their health promotion plans. These plans re in tern aligned with the prefectural plans, but tailored to local circumstances. Similarly, employers and schools participate through workplace-based and school schemes.

To monitor the performance of local entities against the HJ21 targets, a range of data sources in used, including data from the National Health and Nutrition survey (see Box 1.6 in Chapter 1). Every year, this survey samples about 15 000 citizens to document their health and nutrition characteristics and behaviours. To correspond with the baseline, interim and final assessments of the second term of HJ21, expanded surveys were or will be conducted in 2012, 2016, and 2020, covering a larger number of districts and triple the sample. However, this survey is too small for monitoring changes at the local level, and many municipalities conduct their own surveys, which vary in quality.

The approach of central oversight and local action allows interventions and programmes to be tailored to local circumstances. It means that local entities can focus on the topics that are the biggest issue in their population, and that they can use interventions that are tailored to the local situation and resources. However, there is no guarantee regarding the quality of each local plan. While the central government has put in place rewards for high-quality practices, there is no regulation, incentive structure or support to ensure a minimum quality level. In addition, the lack of prioritisation by the central government can also translate to the local level, if the framework is rigidly followed and not tailored to the local population.

To entice local schools, employers and other organisations to implement health promotion activities, the central government has put in place programmes that provide guidelines and reward action. One such programme is the Smart Life Project, run by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

The Smart Life Project was started during the first term of HJ21 in 2011. It centres around 4 themes:

Smart Walk: “Plus 10”, promotes an additional 10 minutes of daily exercise, for example brisk walking during the commute, cleaning or gardening

Smart Eat: “Plus one dish every day ”, promotes including an additional plate (or 70g) of vegetables each day

Smart Breath: “Eradication of tobacco smoke”, focuses of smoking cessation

Smart Check: “Regularly knowing your body condition”, promotes the participation in medical check-ups and screening

The Ministry provides guidelines and information on each topic, as well as promotion materials. For example, the ActiveGuide leaflet offers suggestions on how to add 10 minutes of physical activity to your daily routine. Over 4 000 private companies, local organisations and governments participate by distributing information and providing interventions to the public and to their employees.

To encourage participation, the Ministry rewards the most inventive or successful interventions. In 2016, 44 companies, 39 organisations and 25 local governments received an excellence award. The highest prize went to the Kenko Waku Waku Mileage Programme. This programme provides mileage points to employees who form healthy habits such as eating breakfast and having no-alcohol days. The mileage points are accumulated over one year and can result in incentive payments to the employee of up to JPY 130 000 (EUR 1 000) (see Box 2.2) (SCSK Corporation, 2016[17]).

Similar to the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare encouraging health promotion through its Smart Life Project, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) promotes Health and Productivity Management (HPM). HPM programmes consider the health of employees from a corporate management perspective and promote it strategically. Investment in employees’ health as a corporate philosophy is thought to benefit the company as a whole by improving employees’ vitality and productivity, thus enhancing the company’s performance and improving its stock price.

To highlight best practices among companies that engage in HPM, the METI, together with the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE), established the Health & Productivity Stock Selection in 2014 for TSE-listed enterprises. To make this selection, the METI conducts the Survey on Health and Productivity Management and assesses the responses based on five primary criteria: the positioning of health and productivity management in management philosophy and policies; the existence of frameworks for tackling health and productivity management issues; the establishment and implementation of systems for ensuring health-conscious management; the presence of measures for assessing and improving health and productivity management; and adherence to laws and regulations and risk management.

In 2016, the METI established the Certified Health and Productivity Management Organization Recognition Program for large organisations and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that are not TSE-listed. This recognition programme is administered by the Nippon Kenko Kaigi, an organisation collaborating with communities and workplaces to improve health.

In 2018, 26 companies from 26 industries were selected as the 2018 Health & Productivity Stock Selection (Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry, 2018[18]). The Nippon Kenko Kaigi recognised 541 organisations in the large enterprise category and 776 organisations in the SME category (Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry, 2018[19]).

The aim of the HPM recognition programmes is to highlight best practice in HPM and to provide public recognition for the HPM efforts of enterprises. To increase the uptake of HPM, the METI provides information on good practice, cooperates on local awards or recognition schemes with local governments and chambers of commerce, and works with financial institutions and local governments to provide incentives such as low-interest loans, especially for underperforming SMEs. However, the effectiveness of the programme is unclear, as no empirical evaluation exists.

2.3.3. Local communities are developing multisectoral health promotion plans

The targets for health promotion set at the central level are incorporated in prefectural and municipal health promotion plans. Local governments can choose specific focus areas depending on the local health status, and tailor their approach based on the available resources and stakeholders. The aim is to create innovative, multisectoral community-based interventions that bring together different local stakeholders.

One successful example is the Adachi Vegi-tabe Life project. In Adachi City in the Tokyo Prefecture, average vegetable intake was 100g below the recommended 350g in 2012. The Adachi Vegi-tabe Life (“tabe” referring to the Japanese word for “eat”) project was established as part of the city’s local health promotion plan under HJ21. The project aims to increase the consumption of vegetables in the local population, by building a supportive environment that encourages and facilitates vegetable consumption, and educating children on the importance of vegetables.

The focus on vegetable intake was chosen for four reasons. Firstly, interventions in this area were relatively acceptable to citizens with various background. Secondly, a pre-survey identified vegetable intake as sensitive to socioeconomic behavioural disparity. Thirdly, a diet high in vegetables could be used to promote overall health consciousness. Fourthly, a vegetable programme would involve several non-health sectors

Specific interventions included a healthy menu plan, through which 10% of all local restaurants now provide a small salad at the beginning of each meal, or “vegetable rich” meals with over 120g of vegetables. The government provided recipes for cooking with vegetables, and increased their availability at stores and markets. Working with the Local Educational Board, children were educated in school on healthy eating and participated in the cooking of vegetable-rich meals. Support from a local organisation of agricultural producers meant that school lunch schemes had access to affordable fruit and vegetables.

The programme has had a considerable impact. Vegetable consumption in both children and adults increased – notably in both high and low education families. Men and women aged 30 ate 69.1g and 23.6g more vegetables per day, respectively, in 2016 compared to 2014.

In Yokohama City, part of the Kanagawa Prefecture, life expectancy is two years lower than for the top city in the prefecture. To address this, they developed a community health promotion plan that focused on increasing life expectancy by creating healthy behaviours and providing a supportive social environment. These guidelines were developed with the support of various stakeholders including the children bureau, the education committee, medical association, agriculture department, academics and civil society.

One element of this plan is the walking points scheme. This programme encourages participants to walk by providing them with pedometers, and offering prizes as a reward. Participants are allocated walking points based on the number of steps they take per day, which increase their chances of winning gift certificates to spend in one of 1 000 local participating shops.

So far, about 295 000 people out of a population of 3.7 million have enrolled in the scheme. The project is a public-private partnership with the support of the central government. The yearly cost is JPY 300 million (EUR 2.3 million), of which the Ministry of Health contributes JPY 10 million, and the Ministry of Education JPY 50 million.

While these interventions appear successful, and their design evidence-based, it is unclear whether similar examples are widely present across Japan or if the situation is more heterogeneous. It is important to ensure that all regions receive high-quality public health promotion. In addition, local capacity for planning, implementation and monitoring may not be available everywhere. The National Institute of Public Health offers a short training for those involved in monitoring local plans but this is a new task for local public servants and many lack the relevant skills.

2.3.4. Companies play an important part in prevention through workplace-based interventions, though their impact is difficult to measure

Employers play an important role in Japan’s public health system. They are closely involved in the provision of the health checks (see also chapter 3), and they are incentivised by the central and local government to put in place workplace-based health promotion programmes.

Workplace-based programmes are carried out in both public and private organisations on a voluntary basis. The main focus of many of these interventions is on diet and physical activity, smoking and mental wellbeing (e.g. decrease of working hours and increase in leave). Participation in workplace-based programmes for employees is usually not compulsory but coverage is reported to be very high, with virtually all employees participating.

Interventions vary across different employers, for example based on the number of employees (with larger employers implementing more comprehensive interventions), the type of working environment (e.g. whether there is a canteen) and other factors. However, a general pattern can be discerned. The interventions are a mix of actions targeting people at high risk for NCDs, and those that apply to the entire employee population. The former are typically based on the health check-up programme, called Tokutei kenshin, which identifies individuals at high risk who are then followed by health professionals and receive specific advice. This is covered by the health insurance programme to which they are affiliated.

At the employee population-level a range of intervention have been implemented to make the workplace a healthier environment. Interventions focusing on obesity include canteen menu labelling with calories, healthier food options in canteens, pedometers, discouraging the use of cars for short trips, and supporting the use of public transportation. To reduce smoking, some companies have restricted smoking on premises or banned smoking during working hours, and worked with insurers to provide educational material on quitting smoking. To increase physical inactivity, workplace-based interventions can provide standing desks, create places to stretch, decrease the number of printers so that employees have to walk more to get their printed material, and provide places for standing meetings.

To encourage employees to participate, some companies set targets and develop scoring systems (see also Box 2.2). For example, employees may earn points for walking a minimum number of steps, going a number of days without alcohol in a week, or reaching a certain BMI threshold. These points can then be converted into money, leave or other benefits. To encourage action and peer-support, some activities are conducted in teams, with additional benefits if all the members of the team reach a certain threshold.

The impact of these interventions is hard to measure on physiological dimensions (e.g. BMI) and reported evidence on the effectiveness of these interventions is mixed. Some companies report positive changes as well as savings in health care expenditure, physiological risk factors or reduction in absenteeism. But many others did not manage to identify any positive trend.

It is possible however that no effect is observed even if the intervention is effective. First, analyses are often crude and simply look at overall scores, without taking into account underlying trends (e.g. ageing of employees, new employees joining the company). Second, interventions need time to produce positive effects and the follow-up is often relatively shortly after the beginning of the intervention. Third, it may simply be that the effect of the intervention is watered down by an external environment that does not support healthy behaviours (e.g. exposure to second hand smoking not in workplace but in other environments).

In general, while workplace-based interventions can contribute to creating a health promoting environment, they have limitations. These actions are relatively easy to implement in the central offices and headquarters, but local offices are unlikely to be covered by the same services, particularly for actions entailing significant structural changes. Moreover, in the mid- and long-term, these programmes become routine and people lose interest. There is a need for continuous innovation and evaluation to ensure the programme remains appealing to employees and effective. To maintain interest in the programme, the interventions can be further tailored to specific individuals based on their risk factors or attitudes, or by increasing health literacy among employees.

From a public health point of view, workplace-based interventions only cover a limited share of the population, and only during working hours. Their impact on overall population health is therefore limited, and other interventions are needed to target children and elderly, and to improve the environment outside of work. Moreover, it is unclear how many workplaces have health promotion programmes.

Box 2.2. Example of a workplace-based intervention

The IT company SCSK has developed an extensive workplace-based programme to improve the health and wellbeing of its employees.

One element is the Mileage Program, through which employees collect mileage points for healthy habits, including having breakfast, walking 10 000 steps per day, brushing their teeth twice daily and smoking cessation. The mileage points are accumulated over one year, both for the individual and for teams, and can be exchanged for incentive payments. Bonus payments are awarded to employees who achieve improvements in their BMI, blood lipids and glucose level, blood pressure or liver function as measured during the health checks. In total, employees can earn up to JPY 130 000 (EUR 1 000).

In addition to this scheme, the company has also changed the physical environment to encourage healthy behaviour. Smoking at work was prohibited in 2013. A relaxing room is available where employees can receive massage at reasonable price, during office hours. In addition, several sports and cultural activities are offered, including football, tennis, golf and music.

To improve the mental wellbeing of employees and their families, the company has taken steps to improve working conditions. It has introduced policies increasing leave, teleworking, and supporting childcare. Every Wednesday is “no extra work day”, when no overtime is worked and employees leave on time.

A limitation of the programme is that the results of the employees are self-reported, with no clear way of cross-checking. In addition, over time there has been stagnation in the results, and the company is reviewing the programme.

Source: SCSK Corporation (2016[17]), CSR Activities: Health and Productivity Management, https://www.scsk.jp/corp_en/csr/labor/health.html.

2.3.5. Nutritional education and healthy meals are a central part of the curriculum in Japanese schools

The Ministry of Education is in charge of school-based interventions to promote healthy lifestyles among children. School lunches are a central part of health promotion in Japanese schools. Japan has a long history of school lunches, with the 1954 School Lunch Act making them an official part of the education system (Tanaka and Miyoshi, 2012[20]). In 2014, 99% of elementary schools and 85% of junior high schools provided school meals, covering a total of nearly 10 million children (Yotova, 2016[21]). The average monthly fee per student is JPY 4 300-4 900 but there are subsidies for children whose parents cannot afford this (Asakura and Sasaki, 2017[22]).

The Ministry of Education has set specific nutritional standards for school lunches, requiring them to provide, amongst other, 33% of a child's daily energy, 50% of daily magnesium and 33% of daily zinc requirement, and limit fat to 25%-30% of total energy (Ministry of Education Culture Sports Science and Technology, 2013[23]). Based on these requirements, lunch staff and nutrition teachers develop detailed meal plans using fresh ingredients, in some cases with a focus on locally produced products.

A diet record study among students found that, compared to their weekend meals, school meals reduced deficiencies in almost all of 60 different nutrients (Asakura and Sasaki, 2017[22]). Another study found that while overall fruit and vegetable intake was lower in children with a lower socio-economic status (SES), fruit and vegetable intake from school lunch did not vary by SES – indicating that school lunches help reduce SES inequalities (Yamaguchi, Kondo and Hashimoto, 2018[24]). Moreover, the school lunch coverage rate in junior high schools at prefecture level could also be linked a lower prevalence of overweight and obesity among boys (Miyawaki, Lee and Kobayashi, 2018[25]). For girls no significant effects were found.

In addition to providing a healthy meal, school lunches also play an important part in food and nutrition education, or Shokuiku (see also Box 2.3). Shokuiku is an official part of the National Curriculum Standard, which sets the objectives for the material taught in schools. The 2008 School Lunch Act revision included nutritional education as a key aim of the school lunch programme (Tanaka and Miyoshi, 2012[20]). For example, students can learn about cooking and hygiene by helping to prepare the dishes, serving them and assisting in clean up. Teachers are encouraged to discuss the meal, its ingredients and their origins with their students (Ministry of Education, 2010[26]) (Tanaka and Miyoshi, 2012[20]).

Further education on nutrition and healthy eating in schools is provided by specially trained nutrition teachers (Ministry of Education,(n.d.)[27]). These teachers coordinate the food and nutrition education activities, including developing school lunch menus and related Shokuiku materials, teaching during lunchtime or in dedicated home economics classes, organising trips to local farms and other cross-curricular activities. In 2013, 22% of schools had a trained nutrition teacher (Yotova, 2016[21]).

Box 2.3. Shokuiku

Food and nutrition education, or Shokuiku, is an important part of the Japanese school curriculum. However, it is not limited to school-aged children. The Basic Law on Shokuiku, implemented by the Cabinet Office in 2005, sets out a national movement to make nutritional education a part of every person’s life.

To implement this national movement, a Basic Program for Shokuiku Promotion was developed. This lays out the responsibilities of a wide range of players, including schools, local governments and businesses: schools are required to make Shokuiku an integral part of the curriculum; farmers and fisheries are encouraged to collaborate with educators and provide opportunities for visits; food producers are asked to contribute by organising cooking classes or providing Shokuiku information in relation to their products. Similar to the HJ21 approach, prefectures, municipalities, towns and communities are encouraged to develop their own local Shokuiku promotion programmes.

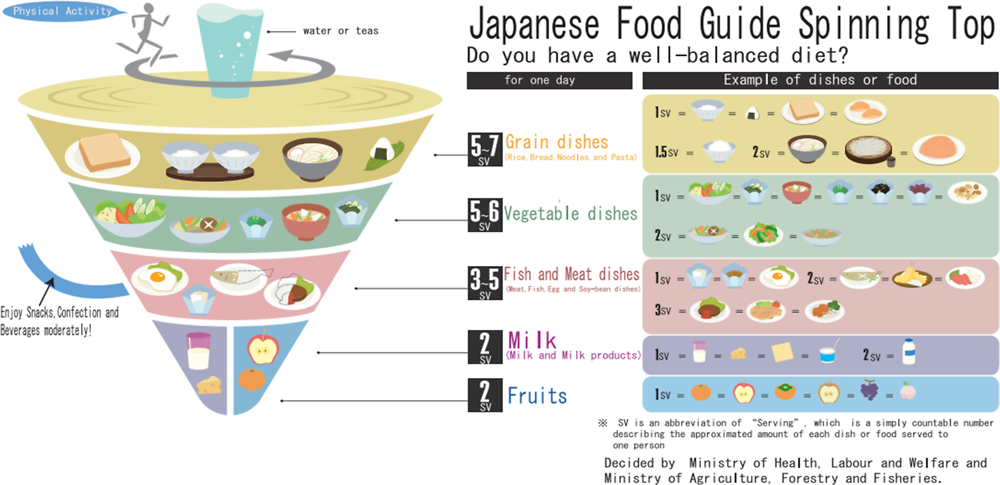

To guide the content of Shokuiku, the Ministries of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) together implemented the new Dietary Guidelines for Japanese in 2016. The original guidelines consisted of 10 basic suggestions (e.g. “assess your daily eating” and “avoid too much fat and salt”). To make the guidelines more specific and easier to use, the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top was developed: an inverted pyramid demonstrating the composition of a balanced diet.

Figure 2.8. Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top

Source: Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries, Promotion of Shokuiku (Food and nutrition education), http://www.maff.go.jp/e/policies/tech_res/shokuiku.html; Yotova (2016[21]), ‘Right’ food, ‘Responsible’ citizens: State-promoted food education and a food dilemma in Japan, https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12135.

To increase physical activity in children, schools are required to provide a minimum number of hours of physical education (PE) classes, as defined in the National Curriculum Standard. All students attend PE class about twice a week in the school term and learn sports skills and rules including traditional martial arts and dance (Tanaka et al., 2016[28]). The Ministry of Education also sets guidelines for school infrastructure and equipment for PE, as part of the very detailed school facilities requirements (Ministry of Education, 2018[29]).

Japan also has a long history of promoting walking to school. The School Education Act of 1953 requires that elementary schools are available within 4 kilometres of each child (Mori, Armada and Willcox, 2012[30]). Moreover, many municipal boards of education have made walking to school mandatory if the students live within a specified walking distance or time from school. Schools are encouraged to invest in safety management, such as organising group walking, inspecting and mapping safe routes, and patrolling by volunteers. A survey by the Ministry of Education in 2008 indicated that 95% of elementary school children and 69% of junior high school students regularly walked to school (Active Healthy Kids Japan, 2016[31]).

In addition to diet and physical activity, mental health issues are also addressed in Japanese schools. For example, psychiatrists or pediatricians are invited to classrooms as guest speakers, to educate the students during their Special Activities period, or “Tokkatsu”.

2.4. Several population-level policies are in place to support the prevention strategy

The HJ21 strategy forms the basis of many local initiatives and programmes to improve population health. In addition to these activities, Japan has a number of population-level policies that contribute to creating a health-promoting environment.

2.4.1. To reduce smoking rates, Japan is trying to implement a ban on smoking in public places – but tobacco marketing is not yet being addresses

Smoking cessation is a part of the HJ21 framework and one of the four pillars of the Smart Life campaign, and there are examples of local programmes that promote cessation and provide support to smokers. In addition to these interventions targeted at individuals, population-level policies can play an important part to reduce the impact of tobacco on public health.

Japan is a signatory of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), and has implemented some of the Convention’s recommended interventions on tobacco control, including taxes, health warning labelling, and public health campaigns. Currently, the total tax on cigarettes, at 63.1%, is slightly below the WHO recommended level of 75% (World Health Organization, 2017[32]) (World Health Organization, 2015[33]). However, the tobacco excise tax rate is set to increase with JPY 1 per cigarette in October 2018, 2020 and 2021, increasing the excise tax by 25% from 12.2 to JPY 15.2 per cigarette (Ministry of Finance, 2018[34]). This will bring the tax rate in line with recommended levels, though the exact level or taxation will depend on consumption tax and retail price.

Japan has recently implemented laws to reduce the impact of passive smoking, by restricting smoking in public places. In 2017, the Ministry of Health proposed a bill that would make all indoor public places smoke-free. Despite strong support from the general public, patient groups, academia, and health-care professionals, including the Japan Medical Association (Tsugawa et al., 2017[35]), the bill did not pass, even after amendments were suggested to exempt smaller establishments. Reasons cited for the bill’s defeat were concerns for bar and restaurant revenue, the perceived small health impact of second-hand smoke, and the perception of punishing smokers.

A revised bill was accepted in Japan’s National Diet in July 2018. This bill extends the exemption from establishments smaller than 30m2 to those smaller than 100m2 (though with a caveat that this is a temporary measure and regulation may become stricter in the future). These smaller establishments where smoking is not banned are required to post a sign warning stating that they allow smoking, and people under the age of 20 are not allowed to enter those establishments. The ban on public facilities was also relaxed in the revision: although smoking in indoor public places is banned, smoking in outdoor space on public premises is allowed as long as the necessary measures are taken to contain smoke. The measures will be fully enforced by April 2020, ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games. Currently, there is already local regulation in place, for example a ban on smoking in public places in the Tokyo prefecture, and a ban on smoking in the street in certain areas of Tokyo and Kyoto.

Japan currently has no comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, as recommended in the FTCT (World Health Organization, 2017[32]). There are voluntary restraints in place, set by the Tobacco Institute of Japan, a trade organisation with directors from all the major tobacco companies. These guidelines discourage the use of TV, radio, cinema, internet sites (unless it is technically possible to target adults only) and outdoor advertising (except at places were tobacco is sold); state that advertisements cannot be appealing to minors, and that advertisements and packaging need to include health warnings (Tobacco Institute of Japan,(n.d.)[36]). However, the evidence suggests that partial and voluntary bans have little to no effect on smoking prevalence (World Health Organization, 2017[37]). Moreover, it is unclear whether these restrictions are being violated with recent e-cigarette advertising (see Box 2.4).

All tobacco products in Japan are required to carry a written health warning covering 30% of the package display area. While this is a commendable policy, it should be noted that it is less than the WHO recommendation of covering at least half of the package (World Health Organization, 2017[37]). In addition, Japan allows packages to carry marketing terms such as “low tar” or “light”, provided they also include a statement that the health impacts are similar to other tobacco problems.

Box 2.4. E-cigarettes in Japan

E-cigarettes, or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), are devices that deliver nicotine through a nicotine-infused vapour, or by heating tobacco rather than burning it (WHO, 2015[38]). Compared to traditional burning cigarettes, e-cigarettes can act as a lower risk substitute – though the exact level of harm reduction is unknown (Wilson et al., 2017[39]). Several major tobacco companies are now also producing and selling e-cigarettes (Pisinger and Døssing, 2014[40]).

Japan is a major market for heat-not-burn e-cigarettes (Reuters, 2016[41]) (Bloomberg, 2018[42]). While in many other countries the most popular e-cigarettes use a nicotine-infused liquid, this is illegal to sell in Japan. Instead, in Japan e-cigarettes work by heating tobacco to create aerosols (though no smoke), or by vaporising a non-nicotine liquid, and passing this through a capsule containing granulated tobacco. It is estimated that tobacco-heating products reached around 20% of the country’s entire tobacco market by the beginning of 2018 (Bloomberg, 2018[42]) (Financial Times, 2018[43]).

As these products are relatively new, their regulation remains largely unclear. As a result, e-cigarettes are widely marketed on television, through sponsorship and celebrity endorsement, on social networks and other websites. Moreover, these advertisements frequently include unsubstantiated or overstated claims of safety and cessation (World Health Organization, 2014[44]).

A marketing push has also been observed in Japan, where traditional tobacco companies are rushing to claim their share of the e-cigarette market (Financial Times, 2018[43]). One of these advertisements promotes e-cigarettes as a way for smokers and non-smokers to live together in harmony (Campaign Asia, 2018[45]). E-cigarettes are provided exemptions under the new ban on smoking in public places (The Japan Times, 2018[46]), and tobacco companies are using this as an opportunity to market their e-cigarette products in places where normal smoking is not allowed.

There are several reasons to introduce regulation on e-cigarettes. Firstly, while they are thought to be less harmful than traditional cigarettes, they are not harm-free (Pisinger and Døssing, 2014[40]). They may therefore be helpful to current smokers to reduce their risk, but they would increase the health risk to never-smokers and ex-smokers. The advertising of e-cigarettes has been shown to increase e-cigarette use susceptibility among non-smoking young adults (Pokhrel et al., 2018[47]). Secondly, smoking e-cigarettes looks similar to smoking normal cigarettes, and it can therefore renormalise all types of smoking (Wilson et al., 2017[39]) (World Health Organization, 2014[44]). Thirdly, there is evidence suggesting that second-hand exposure to e-cigarettes can have adverse health effects (Hess, Lachireddy and Capon, 2016[48]).

2.4.2. New food labelling regulation has been introduced to improve nutritional information

In 2015, Japan introduced the Food Labelling Act, which changed the requirements for nutrition labels on food products. The Act requires food producers to provide nutritional information, including energy, protein, fat, carbohydrate, and sodium (as salt equivalent), on processed foods and additives sold in containers (Consumer Affairs Agency, 2013[49]). This practice had previously been performed at the producers’ discretion.

In addition, a new health claim category was established (USDA Foreign Agriculture Service, 2015[50]). A health claim is any statement about a relationship between food and health. In Japan, there are now three categories of health claims that can be printed on food product labels. “Foods for Specified Health Uses” are food products that can be labelled as achieving specified health effects. The government reviews and evaluates their safety and efficacy based on scientific evidence, and often clinical trials are required. “Foods with Nutrient Function Claims” are food products that contain a nutrient (for example a vitamin) with a preapproved nutrient function claim. These products can be labelled without submitting a notification or application to the government. The newest category is “Foods with Function Claims”, which can be used on the labels of food products that maintain and promote health in individuals who are not suffering from disease. The producers of these products must bear the responsibilities for such claims, and submit information on the safety and effectiveness of the product to the Secretary-General of the Consumer Affairs Agency before the product is marketed. All of these labels must to be accompanied by a statement saying “Maintain a balanced diet including a staple food, a main dish and side dishes”.

2.4.3. Japan is reforming its tax rate on alcohol products and has already implemented strict drink-driving regulation

Japan has implemented a number of population-level alcohol prevention policies, including taxation and a minimum age for alcohol consumption (set at 20 years) (Sassi, 2015[51]). The national alcohol tax law was reformed in 2017, setting out three changes over the next ten years (USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 2018[52]). This staged approach will eventually equalise the tax rates for wine and sake (increasing tax rates for the former, reducing tax rates for the latter), as well as the tax rates for malt based beer and beer-flavoured liquors (decreasing the tax on the former and increase tax on the latter). One of the impacts of having the same rate of tax for alcohol products with a similar production process and consumption pattern is that it may prevent consumers from switching to a lower taxed product. However, the main reason for the change in tax rates is to improve fairness in tax burden among different alcohol types.

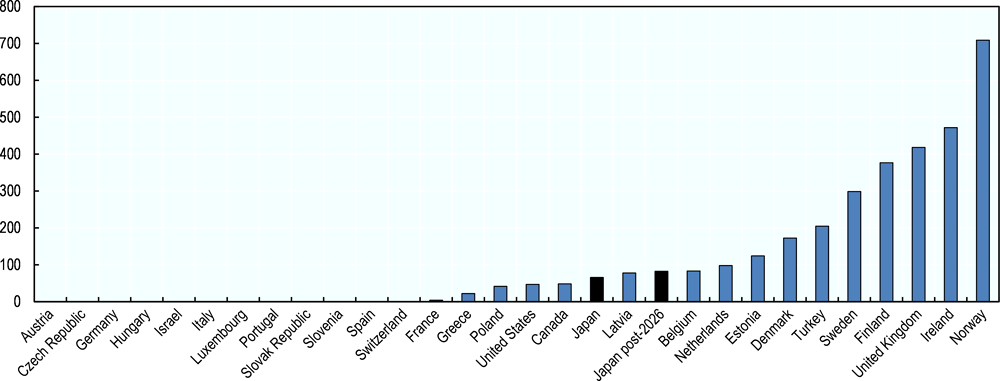

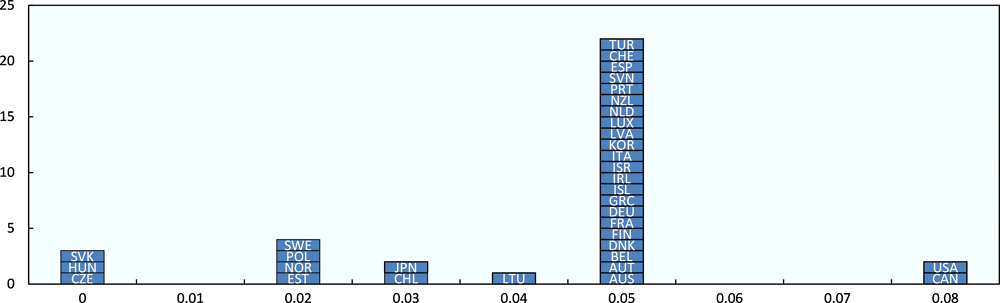

The impact of this reform on the overall taxation level of alcohol is variable by product. For a standard, high malt beer, the tax on a 35cl can will decrease from JPY 77.00 to JPY 54.25, while a standard 750ml bottle of wine will see its JPY 60 tax increase to JPY 75 (USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 2018[52]). The tax on a 750ml bottle of sake, which is currently JPY 90, will be reduced to equal the rate of wine at JPY 75. However, these changes are relatively small compared to the international range of taxation rates (see Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9. Japan’s excise tax on wine compared to other OECD countries

In 2013, the Basic Law on Measures Against Health Problems Caused by Alcohol Intake was enacted, which requires national and local government to implement measures to reduce the impact of alcohol consumption. However, there is little guidance or oversight as to what this action should entail. The Law also established a yearly Alcohol Problems Awareness week, to be held every November.

Japan has enforced strong policy actions to decrease the negative impact of harmful patterns of drinking on others. Since 2000, Japan has implemented successive reforms in its policies on drinking and driving, lowering the legal blood alcohol concentration limit to 0.3 mg/1 ml (compared to 0.5 mg/1 ml in most OECD countries, see Figure 2.10) and increasing the potential fine for drink-driving (Sassi, 2015[51]). People found to be driving while intoxicated can now be fined up to JPY 500 000 million or imprisoned for up to three years (Nagata et al., 2008[53]) (Desapriya et al., 2007[54]). The measures appear to have been successful: one study found that alcohol-related traffic fatalities per billion kilometres driven decreased by 38% in the post-law period (Nagata et al., 2008[53]).

Figure 2.10. National maximum legal blood alcohol concentration (%) for the general population, OECD countries and key partners

Source: World Health Organization (2018[55]), WHO Global Information System on Alcohol and Health, http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.GISAH?lang=en.

2.5. There are a number of steps Japan can take to advance its primary prevention strategy

2.5.1. The HJ21 strategy is ambitious, but would benefit from clearer priorities

The HJ21 strategy sets out an ambitious framework to improve the health of the Japanese population. In 53 targets, it covers a wide range of risk factors, diseases, population groups and outcomes. By setting and monitoring these targets, Japan has ensured that its efforts in prevention are measurable and that the HJ21 strategy can be evaluated.

However, the large number of targets and areas covered means that there are no clear priorities set by the central government. Local governments and other organisations can focus on any of the wide range of issues in the framework. While this allows initiatives to adapt to local characteristics, it can also lead to a dispersion of energy and resources.

It could be preferable to identify a set of priorities where intervention is most needed and where effective interventions are available (World Health Organization, 2018[56]). The successes in these areas can then be used to stimulate further action and expand to a more comprehensive strategy.

2.5.2. Systems need to be put in place to ensure quality prevention programmes across the entire population

The bottom-up approach of the HJ21 strategy relies on local actors to design and implement prevention programmes. This may result in interventions of varying quality, creating patchy population coverage and decreasing the effectiveness of the overall strategy. In addition, it may exacerbate existing inequalities between prefectures. Japan should consider implementing mechanisms and systems to ensure all areas are provided with high-quality prevention programmes, and that successful interventions are disseminated nationally.

Currently, the main mechanism for the central government to encourage local prevention programmes is through awards. However, this focuses attention only on those organisations or local governments that are performing well. Japan could consider combine awards for high-quality interventions with other actions, for example the creation of guidelines with suggested minimum requirements for actions, or the introduction of positive/negative incentives to ensure a minimum level of quality. Underperforming regions could also be provided with dedicated support, advice or funding. This would allow the Ministry to take a more proactive role, and ensure quality interventions are available in all regions and organisations.

In addition, local interventions which have been proven to be successful need to be expanded to other populations. Improving vertical communication between the central and local governments, and horizontal communication between local governments, could encourage the sharing of experiences and insights. To further facilitate the dissemination and uptake of best practices, the Ministry could set up a repository and actively share best practice examples (see Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Approaches to facilitate the dissemination and uptake of best practice initiatives

Providing guidelines and case studies: The EU Physical Activity Guidelines

The dissemination of best practice can be supported by creating and publishing guidelines and case study reviews. The EU Working Group "Sport & Health" has published a report which sets guidelines for member states to implement policies to promote increased physical activity. The handbook includes examples of good practice from various countries, as well as general advice on practical issues such as setting targets, involving different sectors, allocating resources and communication. Overall, 41 guidelines are provided, such as “Public authorities should encourage health insurance schemes to become a main actor in the promotion of physical activity” and “[…] authorities at national, regional and local levels should plan and create appropriate infrastructure to allow citizens to cycle to school and to work” (EU Working Group Sport & Health, 2008[57])

Supporting individuals to drive innovation: The NHS Innovation Accelerator

The uptake of innovation requires committed individuals who can champion the initiative and drive it forward. To speed up the adoption of innovative practices across the National Health Service (NHS) in England, the NHS Innovation Accelerator was established in 2015. This organisation facilitates the systematic uptake of new initiatives across the health system by supporting individuals (“fellows”) who have a high impact, evidence-based innovation. The fellows receive mentorship, bursaries, networking opportunities and workshops to help them disseminate and implement their innovation in the NHS (NHS Innovation Accelerator, 2017[58])

Peer support and collaboration through networking: WHO European Healthy Cities Network

Creating networking opportunities allows different initiatives to learn from each other and collaborate. To provide cities working to improve the health of their population with examples and experiences from other cities, the WHO has established the WHO Health Cities Network. This initiative brings together city officials and other municipal health leaders from different countries, who exchange ideas, lessons learned and practical solutions. Participants submit annual reports to contribute to a growing body of evidence. It also provides an opportunity for collaboration, through the Healthy City marketplace where cities can post opportunities and find partners for multi-city initiatives (World Health Organization, 2018[59]).

2.5.3. Additional population-level policies, following recommended best practice, can help create a health-promoting environment that supports the HJ21 achievements

The HJ21 framework, together with the Smart Life and the Certified HPM Organisations Recognition programme, have resulted in a wide range of local health promotion initiatives, in communities, workplaces and schools. However, there has been less focus on population-wide strategies to improve public health.

There are some example of population-based strategies implemented by local authorities and companies, for example the smoking ban in Tokyo’s street. However, leaving these decisions to local governments or single entities is likely to result in a haphazard approach.

The relative absence of national, population-level interventions can have a detrimental effect on the creation of an environment conducive of a healthy lifestyle – a central aim of HJ21 – and may hinder the positive effects of interventions at the local level. Based on our analyses and international evidence, population-level interventions are cheap and highly cost-effective (and frequently cost-saving) (Chokshi and Farley, 2012[60]; Sassi, 2015[51]; World Health Organization, 2011[61]; World Health Organization, 2003[62]; World Health Organization, 2017[63]).

To strengthen Japan’s primary prevention programme, and support healthier lifestyles and healthy aging, Japan could take a more robust approach to three main risk factors: smoking, diet, and alcohol consumption.

2.5.4. To achieve the HJ21 targets on tobacco, Japan could consider implementing population-level policies in line with international conventions.

Japan has implemented a number of tobacco policies in line with the FCTC, but there remain areas where action can be taken.

While it is encouraging that a bill on passive smoking has been passed, the exemptions to the smoking ban mean that only approximately 45% of eating and drinking establishments is covered by the ban (Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, 2018[64]). In comparison, a ban on smoking in public places in the Tokyo prefecture, which will come into effect at the same time as the national ban, covers around 84% of restaurants (The Japan Times, 2018[65]). Japan should consider increasing the coverage of the ban, to ensure comprehensive protection from second-hand smoke.

In addition to the public health benefits, increasing the coverage of the ban may also contribute to its acceptability. In the Netherlands, an exemption was put in place for hospitality venues smaller than 70m2 without employees in 2012 (Hummel et al., 2017[66]). However, this decision was later overturned, and a full ban came into force in 2014. A study looking at the social acceptability of indoors smoking found that the acceptability of smoking in bars remained higher than for other venues, and suggested that this is due to the disrupted implementation of the ban (Hummel et al., 2017[66]). In Switzerland, the regions can decide whether to tighten the national regulation, which allows smoking in bars and restaurants up to 80m2. In the regions where comprehensive bans were implemented, the acceptance of the ban in both smokers and non-smokers increased after implementation, while in two regions with incomplete smoking bans the acceptance score decreased (Rajkumar et al., 2015[67]).

Japan only has a partial, voluntary tobacco marketing code, which was set by the industry. Partial bans are less effective as the tobacco industry is likely to change focus and reallocate marketing funding to permitted activities. Voluntary bans often focus on advertising by the manufacturers, ignoring the highly effective point-of-sale advertising in retail stores. Comprehensive advertising regulation needs to cover all types of marketing, including direct advertising in all types of mass media, online, promotions and sponsorship, and be strictly enforced (World Health Organization, 2017[37]).

All tobacco products in Japan are required to carry a written health warning, covering 30% of the package display area. To make these warning labels more effective, Japan could consider including graphics or images, and making them cover at least half of the package (World Health Organization, 2017[37]). Japan should also consider tightening regulation around the use of deceptive terms, such as “low tar” or “light”. While these claims are prohibited in main countries and contrary to the FCTC, in Japan they are allowed provided they include a statement that the health impacts are similar to other tobacco problems. Japan could also consider other prevention policies that are in line with the FTCT, such as plain packaging (World Health Organization, 2008[68]) and banning flavoured cigarettes (World Health Organization, 2014[69]).

To achieve the targets set in HJ21 and reduce smoking prevalence from 19.5% in 2010 to 12% in 2020, Japan should consider implementing population-level measures in line with the FCTC, including comprehensive indoor smoking bans, regulation on tobacco product advertising, and effective labelling and packaging. While the opposition to such regulation is strong, recent successes in tobacco legislation in other OECD countries shows that this can be overcome (see Box 2.6).

Box 2.6. Recent successes in tobacco legislation

While tobacco legislation is often met with strong opposition from producers, there have been a number of recent litigation successes against this opposition:

Plain packaging: Australia (2012), the United Kingdom (2016) and France (2016) all won legal challenges brought by tobacco companies against plain packaging proposals on the basis of intellectual property arguments. In Australia it was judged that there was no breach of property rights since neither the government or a third party profited; in France any infringement was considered justified by the public health objective; and in the United Kingdom the ban was considered not an expropriation of property rights but a curtailment of use, introduced for legitimate public interest reasons.

Display ban: Norway’s ban on displaying tobacco products at retail establishments was upheld in court in 2012 after a challenge from a tobacco producer, as the ban was judged to help denormalise tobacco use.

In other cases, pressures from NGOs and other civil groups have led to the enforcement of the FCTC:

Smoke-free places: In 2013 the court in New Zealand upheld a challenge from the Cancer Society, which disagreed with an exception in the public places smoking ban for casinos. The court found that the reasoning behind the exception was flawed and ordered the Ministry to review its policy. In the Netherlands, the Dutch Non-Smokers Association CAN (Club of Active Non-Smokers) challenged the exception for small cafés in court in 2014. The challenge was upheld as a violation of the FCTC.

Source: Tobacco Control Laws (2018[70]), Major Tobacco Control Litigation Victories https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/litigation/major_litigation_decisions.

2.5.5. Recent reform on food labelling could be expanded to promote healthier food choices in combination with other population-level policies

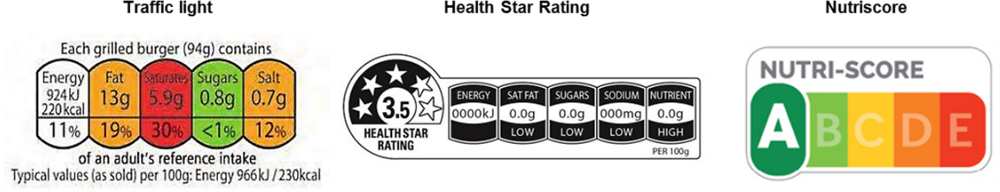

The introduction of the new Food Labelling Act is an important step to creating a health promoting environment, by enabling people to make informed and healthy choices. To take this even further, Japan could consider implementing front-of-pack labels. Evidence shows that easy-to-understand interpretative labels, printed clearly on the front of the package, prompt a greater response rate from consumers in terms of food and diet choices than detailed back-of-package nutrient lists (Cecchini and Warin, 2016[71]). In addition to informing consumers, labelling schemes have also been shown to encourage producers to reformulate their products (Thomson et al., 2016[72]; Vyth et al., 2010[73]). Different approaches to food labels can be taken (see Box 2.7). Labelling initiatives could also be expanded to include restaurants and other catering businesses.

Box 2.7. Front-of-package food labels

Labels to promote healthy food products

Many countries have introduced voluntary labelling schemes for producers of healthy or healthier products (World Cancer Research Fund International, 2017[74]) The label provides at-a-glance information for consumers, as well as an incentive for producers to formulate healthier products (Vyth et al., 2010[73]). It can apply to products that are considered healthy (e.g. where the nutrient content meets specific requirements) or healthier than other products of a similar type (e.g. products with a significant reduction in salt content).

One example is the “Keyhole” logo, which has been used since 2009 in Denmark, Norway and Sweden, and more recently in Iceland and Lithuania (OECD, 2017[75]). The criteria for food to be allowed to carry the logo are set by the national authorities, and favour food lower in fat, sugar or salt, or higher in healthy fat, fibre or wholegrain, compared to other food products in the same category (Swedish National Food Agency, 2013[76]). This allows consumers to select the healthiest option within a category, for example meat, oils or ready meals. Soft drinks, candy and cakes, or foods with artificial sweeteners, are not eligible for the label. The use of the logo by food producers is voluntary and free of charge.

Figure 2.11. The Keyhole logo

Source: Swedish National Food Agency (2013[76]), Nordic keyhole: Experience and challenges, http://www.who.int/nutrition/events/2013_FAO_WHO_workshop_frontofpack_nutritionlabelling_presentation_Sjolin.pdf.

Labels to warn for unhealthy food products

Some countries have introduced warning labels for foods high in salt, sugar, fat or calories. Contrary to the voluntary healthy food labels, these types of schemes need to be mandated. Finland introduced a mandatory label on foods high in salt in 1993, and has since continued to lower the cut-off limit for the label (Pietinen, 2009[77]). Different limits are set for specific food categories, such as bread, crisp bread, breakfast cereals and meat.

In 2016, Chile introduced a mandatory food labelling system that uses four black labels to indicate whether a certain foodstuff is high in calories, salt, sugar or fat (Figure 2.12) (Ramirez, Sternsdorff and Pastor, 2016[78]). The thresholds for the labels are universal rather than per food category. They are being introduced in a phased design, with increasingly strict targets set at 24 and 36 months after implementation.

Figure 2.12. Chile’s food labels

Source: Chile Ministry of Health.

Labels to summarise the overall nutritional profile of food products

In addition to warning and endorsement labels, some countries have introduced front-of-pack labels that aim to describe the overall nutritional profile of a product in an easy-to-understand way. This can be done in a variety of ways. The United Kingdom introduced a “traffic light” system, where different nutrients are colour coded (Department of Health, 2016[79]). New Zealand and Australia use the Health Star Rating, which calculates an overall score (between 0.5 and 5 stars) based on the various nutrients in the product (Ministry for Primary Industries, 2017[80]). The French Nutriscore combines the two, by calculating an overall score (from A to E) which is reinforced by traffic light colours (Santé Publique France, 2017[81]). Participation in these schemes is voluntary.

Figure 2.13. Food labels describing overall nutrient profile

Source: Department of Health (2016[79]), Guide to creating a front of pack (FoP) nutrition label for pre-packed products sold through retail outlets, https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/multimedia/pdfs/pdf-ni/fop-guidance.pdf; Ministry for Primary Industries (2017[80]), How Health Star Ratings work, https://www.mpi.govt.nz/food-safety/whats-in-our-food/food-labelling/health-star-ratings/how-health-star-ratings-work/; Santé Publique France (2017[81]), Nutri-score: un nouveau logo nutritionnel apposé sur les produits alimentaires, http://santepubliquefrance.fr/Actualites/Nutri-score-un-nouveau-logo-nutritionnel-appose-sur-les-produits-alimentaires.

Japan could also implement policies that aim to improve diets by reducing consumption of unhealthy nutrients, for example sugar and trans-fat (World Health Organization, 2016[82]) (World Health Organization, 2018[83]). Both of these nutrients have been proven to contribute to the burden of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, obesity and diabetes (World Health Organization, 2018[83]) (Te Morenga, Mallard and Mann, 2012[84]) (Te Morenga et al., 2014[85]). OECD countries are increasingly using actions to limit consumption of specific nutrients, by regulating their use or making their use economically less attractive, and by providing information to the public through mass media campaigns and labelling.

Currently the Japanese government works with businesses on a voluntary basis to reduce trans-fat levels in food, but it could consider implementing legislative bans, as has been done in many other countries and is recommended by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2018[83]). Denmark for example banned industrially produced trans-fats in food in 2003, setting a precedent for the rest of the European Union (World Health Organization, 2018[86]).

Japan could also consider implementing regulation around the marketing of unhealthy foods and drinks. Children are especially perceptive to advertisement, and restrictions on the marketing of products high in fat, sugar or salt to this population group is recommended (World Health Organization, 2010[87]). A large number of countries have implanted restrictions on the type, medium, content or time of food advertising (World Cancer Research Fund International, 2017[88]).

2.5.6. To reduce alcohol consumption, Japan could consider implementing cost-effective interventions such as marketing regulation

While Japan has adopted some important population-level measures to reduce alcohol consumption and its impact on society, there are a number of other effective and common interventions, such as warning labels and restrictions on advertising, that have not yet been implemented.

Almost all OECD countries have implemented some form of alcohol advertising regulation, considered by the World Health Organization as a “best buy” intervention (World Health Organization, 2014[89]). Japan is a notable exception, with no restrictions on any form of alcohol marketing. In particular advertising to children, which has been proven to be highly effective in increasing alcohol use, should be banned (Sassi, 2015[51]; Burton et al., 2017[90]; World Health Organization, 2011[61]).