Thailand is a fast-emerging country that aspires to become a high-income economy by 2037. Strong growth since the 1970s enabled the country to join the group of upper middle-income economies in the early 2010s. At the same time, the benefits of prosperity have not been shared evenly nationwide and economic development has taken a toll on the environment. Moving forward, Thailand needs to achieve faster but also more inclusive and sustainable economic growth. This chapter provides a synthesis of the constraints analysis across the five critical areas of the Sustainable Development Goals – people, prosperity, partnerships, planet and peace. This is followed by an in-depth analysis of the three main transitions Thailand faces going forward: enabling new growth by unlocking the full potential of each region, developing more effective methods of organisation and collaboration between actors and levels of government, and managing water security and disaster risk.

Multi-dimensional Review of Thailand

Chapter 1. Synthesis of multi-dimensional analysis: New capabilities for Thailand

Abstract

Thailand is striving to realise an ambitious long-term development vision. Strong growth since the 1970s enabled the country to join the group of upper middle-income economies in the early 2010s and has seen Thailand perform well in many areas. Poverty has plummeted and well-being has improved considerably, notably with respect to health and education. At the same time, economic development has taken a toll on the environment and the benefits of prosperity have not been shared evenly nationwide. Moving forward, Thailand needs to achieve faster but also more inclusive and sustainable economic growth. Getting there will require making the most of every region and developing more effective forms of organisation and collaboration between actors and levels of government.

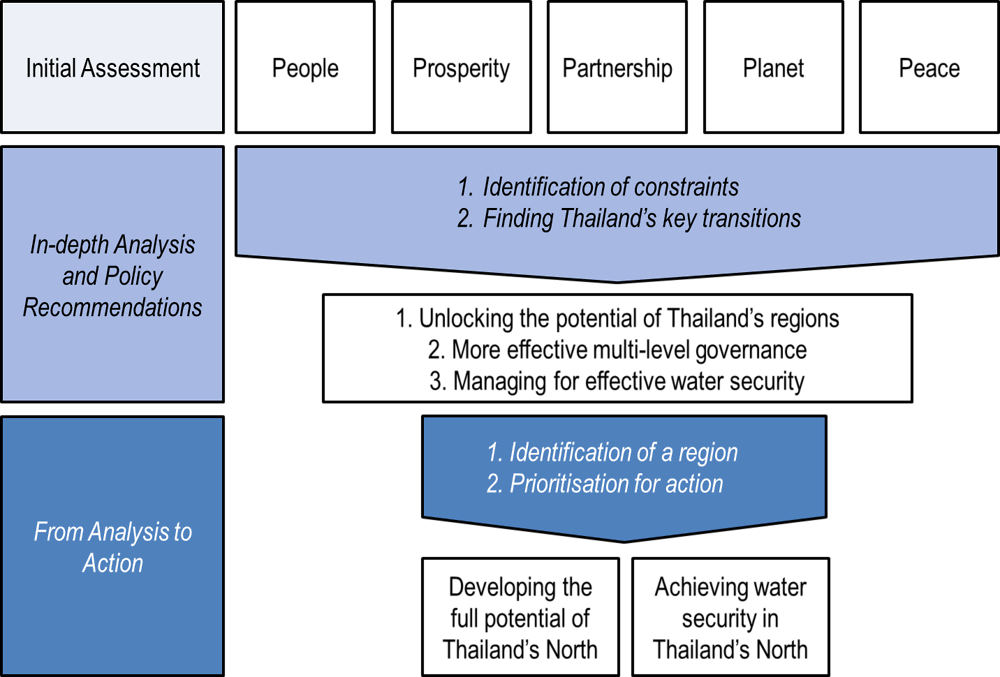

The Multi-dimensional Country Review (MDCR) is being undertaken to support Thailand in achieving its development objectives. It consists of three phases and reports. This third volume provides a synthesis of the analyses and policy recommendations provided in previous volumes – the Initial Assessment (OECD, 2018[1]) and In-depth Analysis and Recommendations (OECD, 2017[2]) – and provides a concrete set of actions and a scorecard of indicators (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Multi-dimensional Review of Thailand – Process

Boosting regional development will need to be a cornerstone of Thailand’s future development strategy. The action plan presented in this volume focuses on the North of Thailand, one of the fastest growing, most diverse and yet the second poorest region of the country.

Stakeholders in the north determined priorities and several of the proposed actions using a “governmental learning spiral” approach – a technique for learning in complex political environments. Participants at two policy dialogue events, held in Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai, worked through the findings and recommendations of the earlier MCDR reports. The purpose of the policy dialogue was to transfer the knowledge embodied in these reports to local actors as a first step towards implementation. These pioneering actions would enable the North to become a “Policy Lab”, setting an example for Thailand’s other regions to embrace structural transformation, more efficient governance and environmental sustainability.

This chapter provides a synthesis of the preceding volumes Initial Assessment and In-depth Analysis and Recommendations. It retraces the constraints analysis based on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the OECD well-being framework and the resulting focus on unlocking the potential of regions, water security and more effective multi-level governance. Chapter 2 contains the action plans for developing the full potential of the North, and Chapter 3 presents the action plan for better managing water resources in the North. The final chapter includes the scorecard proposed for measuring progress.

Initial Assessment: Thailand’s aspirations and key constraints to development

Thailand aspires to become a high-income economy by 2037 enjoying “security, prosperity and sustainability” based on its sufficiency-economy philosophy (2017 National Strategy Preparation Act). The National Strategy sets out five broad objectives in this regard: (i) economic prosperity – to create a strong and competitive economy driven by innovation, technology and creativity; (ii) social well-being – to create an inclusive society that progresses without leaving anyone behind by realising the full potential of all members of society; (iii) human resource development and empowerment – to transform Thai citizens into “competent human beings in the 21st century” and “Thais 4.0 in the first world”; (iv) environmental protection – to become a liveable, low-carbon society with an economic system capable of adjusting to climate change; and (v) public sector governance – to improve public sector administration and reduce corruption.

The Initial Assessment of Thailand (OECD, 2018[1]) focused on existing constraints and capabilities related to these ambitions. The assessment applied the OECD’s well-being framework and was structured in accordance with the UN’s Agenda 2030 and its 17 SDGs, which are divided into five categories: People, Prosperity, Planet, Peace and Institutions, and Partnerships and Financing. For each category the assessment evaluated achievements and current policy and identified key constraints that hinder Thailand’s progress. The constraints analysis identified 20 constraints (about four per P) which point to four cross-cutting challenges that Thailand needs to address in order to achieve its goals.

The assessment distinguished three key transitions: unlocking the potential of Thailand’s regions, better multi-level governance and water security. These became the focus of the subsequent in-depth analysis and policy recommendations.

Well-being: Thailand offers a good quality of life for many, but work, skills and the environment present challenges

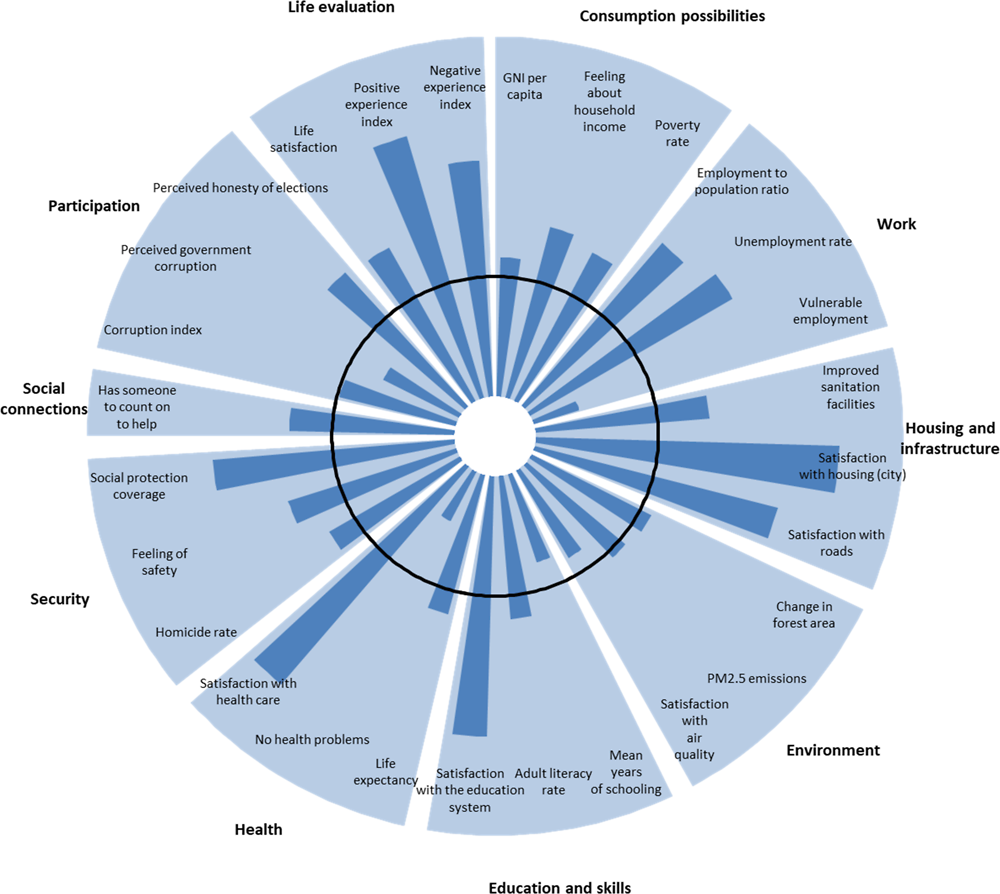

The OECD’s “How’s Life?” index, which benchmarks well-being, indicates that Thailand performs well on several dimensions of quality, particularly housing and social connections, but lags behind on skills, informality and the environment. Well-being relates to material conditions (e.g. income, jobs and housing) but also encompasses the broader quality of people’s lives including their health, education, environment, social connections and subjective well-being (OECD, 2017[2]; Boarini, Kolev and McGregor, 2014[3]). Performance is especially strong with respect to life evaluation, social connections, security, and housing and infrastructure. The picture is more mixed when it comes to other dimensions, such as the environment, education and skills, or work. For instance, while levels of unemployment are very low, working conditions are worse than might be expected given Thailand’s level of development (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Current and expected well-being outcomes for Thailand: Worldwide comparison

Note: The bars represent the observed well-being values for Thailand and the black circle shows the expected values based on Thailand’s level of GDP per capita. The latter stem from a set of bivariate regressions with GDP as the predictor and the various well-being outcomes as dependent variables from a cross-country dataset of around 150 countries with a population of over a million. All indicators are normalised in terms of standard deviations across the panel. The observed values falling inside the black circle indicate areas where Thailand performs poorly in terms of what might be expected from a country with a similar level of GDP per capita. As this figure only shows outcomes at the national level, disparities between regions might be masked.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

The five pillars of Agenda 2030: Thailand has showed impressive performance, the remaining constraints point to the need for further transitions

Thailand generally performs well across the five pillars of the Agenda 2030, but further progress towards a more inclusive and sustainable economy is needed. Overall, benchmarking past performance against SDG targets attests to Thailand’s impressive performance, particularly on outcomes related to people and prosperity. Progress in poverty reduction and boosts to innovation and electricity infrastructure are especially notable. At the same time, the underlying structure of the labour market has hardly changed and about half of the working population continues to work informally with limited access to protection and services. Major environmental challenges remain as well, notably with respect to emissions and pollution (OECD, 2018[1]).

People

The People pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development focuses on quality of life in all its dimensions, and emphasises the international community’s commitment to ensuring all human beings can fulfil their potential in dignity, equality and good health.

Table 1.1. People – four major constraints

|

1. Informality remains widespread and informal workers are not well covered by the social protection system. |

|

2. Pension arrangements do not prevent old-age poverty and will become even more inadequate as the population ages. |

|

3. Basic education outcomes fall short of global benchmarks. |

|

4. Tertiary and vocational education does not adequately equip students with the necessary skills required by industry. |

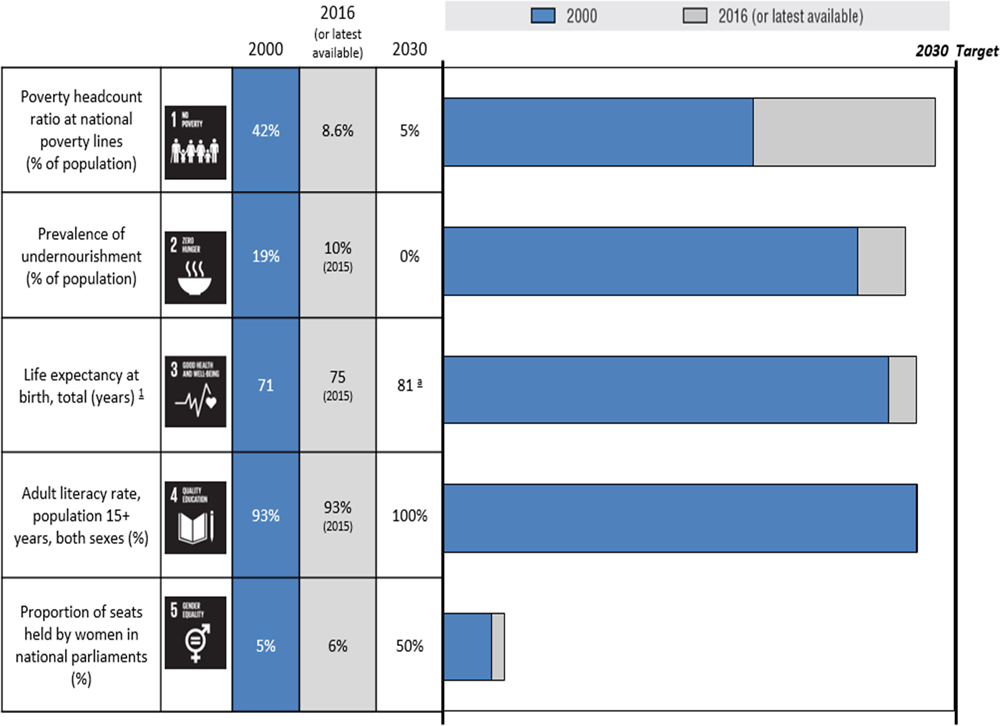

Figure 1.3. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): People

Note: The bars measure Thailand’s performance in 2000 and 2016 (or latest year – as indicated accordingly) for a selection of 26 indicators across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indicators are chosen in line with the UN global framework and to ensure measurability. The 2030 aspirational target values refer to the pre-defined UN target (established by the UN IAEG and available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/metadata-compilation/). Targets are all normalised to 100 for representation and comparison purposes.

a. When UN 2030 targets were not quantifiable, targets were calibrated to the average performance of OECD countries, in accordance with the methodology outlined in a recent OECD study on measuring distance to the SDGs targets (OECD, 2017[4]). However, the target for “Total debt service” was calibrated to the average value of the top 3 performers in the ASEAN region, due to data unavailability in OECD countries.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

Over recent decades, economic success has brought impressive social progress. Poverty has plummeted from 60% in 1990 to 7% today measured against the national poverty line (2% at international USD 3.1 per day; Figure 1.3), while social services in education and health have expanded considerably and improved. The introduction of the Universal Health Coverage Scheme in 2002 represented a major step towards basic social protection for all, including those living in informal circumstances, and was complemented by the introduction of a universal monthly old-age allowance for the elderly in 2009.

However, as transformation slowed, social and spatial imbalances came to the fore. The share of those in precarious employment stagnated at around half of the working population following the mid-2000s (Figure 1.5), after falling from 70% in the late 1980s, when records started. This reflects the high share of poor agricultural workers in rural areas and significant urban informality. The creation of new activities replacing low-productivity employment has slowed down and the skills required for modern urban jobs exceed those of rural migrants and the urban poor. Today, only 11% of Thai citizens say that they can live comfortably with their current income (Gallup, 2017[5]).

Going forward, more efforts are needed to reduce still widespread informality and persistent, substantial regional inequalities, and to further improve living standards, especially for those who currently work informally.

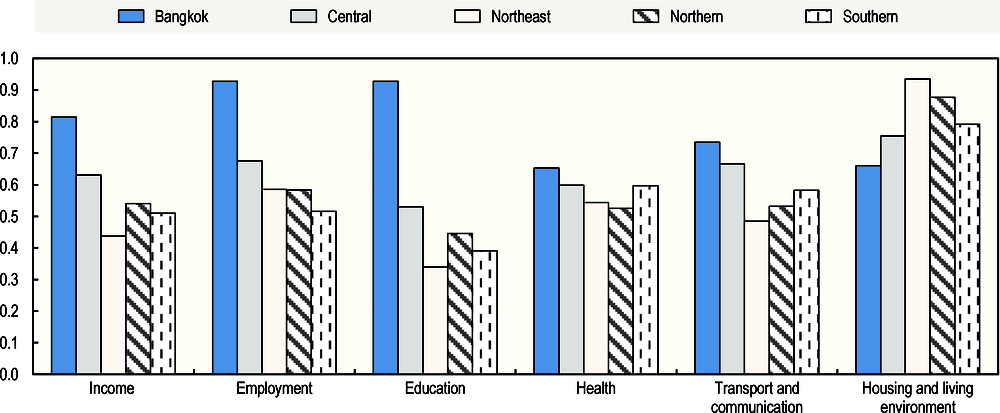

Inequality in Thailand has a strong regional dimension. Inhabitants of the poorer North, Northeast and Southern regions lag behind the more prosperous Bangkok and Central regions, both in terms of income and other dimensions of well-being such as employment conditions, education attainment, health outcomes, and transport and communication infrastructure (Figure 1.4). Mainstreaming equality considerations into the policy formulation process and directing efforts towards narrowing Thailand’s regional gaps, as recognised in the 12th Plan, is likely to improve social cohesion.

Informality remains widespread and informal workers are not well covered by the social protection system. Although the official unemployment rate is exceptionally low, the majority of workers (about 55%) remain in informal occupations and are more likely to be exposed to unstable contractual situations, long hours and hazardous working conditions. Moreover, unemployment insurance is only available to employees in the formal sector and hence informal workers are exposed to greater risk. This is particularly relevant for the 3.5 million migrant workers in Thailand. The relatively strict labour protections, particularly individual dismissal and temporary employment regulations, may contribute to informal employment. However, informality has many other drivers, including tax and social security (dis)incentives to formalise labour, rigid wage structures, low worker productivity and the overall structure of the economy.

Social protection needs to be broadened, notably for informal workers and the elderly. The gradual evolution of Thailand’s social security schemes has resulted in a relatively comprehensive but fragmented system, calling for simplification and harmonisation of programmes. Benefit eligibility is largely tied to employment status, with different programmes for civil servants, people holding formal jobs and informal workers. A universal old-age allowance supports informal workers without pension coverage, but the adequacy of benefits can be improved to prevent old-age poverty. The recent addition of means-tested benefits that target people below a certain income threshold, such as a child grant and a welfare card for low-income earners, is an encouraging step towards reducing inequality.

Figure 1.4. The Bangkok metropolitan region outperforms others in most dimensions of well-being

Note: The Human Achievement Index is a composite index that compares regional performance with achievement scores that use the worst and best performance observed in the provinces. These scores are calculated for a range of indicators for relevant sub-indices (e.g. for employees covered by social security, occupational injuries, unemployment and underemployment rates in the case of the employment sub-index). For the purpose of this report, only the scores for the sub-indices of income, employment, education, health, transport and communication, and housing and living conditions are shown, since their underlying indicators come closest to the SDGs. The Central region as shown here excludes the Bangkok Metropolitan Area.

Source: (NESDC, 2017[6]).

Improving basic education quality and performance will be essential. At around 4% of gross domestic product (GDP), Thailand’s public expenditure on education is among the highest in the region. However, basic education performance falls short of global benchmarks (Figure 1.2). Inefficient and inequitable allocation of resources has undermined investment effectiveness and ultimately hampered learning outcomes. The 2015 results of the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that the performance of Thai students trails most comparator countries and is far below the OECD average. Moreover, compared with PISA 2012, Thailand’s scores declined significantly in science and reading. Reading performance is particularly worrisome, with only around half of Thailand’s 15 year-olds demonstrating reading skills that would classify them as functionally literate. On one estimate, around one-fifth of Thai schools do not meet minimum quality standards, the majority of which are in rural areas (OECD, 2013[7]).

Tertiary and vocational education does not adequately equip students with the necessary skills required by industry. Upgrading human capital is crucial for the success of Thailand 4.0 and managing the transition to an ageing society (OECD, 2018[1]). In tertiary education, enrolment is comparatively high, but the quality and relevance of university programmes needs to be raised. Technical and vocational education does not attract enough students, even though skills shortages are more acute for graduates with vocational training. In 2015, only 34% of upper secondary school students were enrolled in vocational programmes – down from 36% in 2011 and well below the government’s 45-55% target (MOE, 2017[8]). Moreover, the quality of training programmes needs improvement to better equip graduates with the skills needed by industry.

Prosperity

The Prosperity pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development calls for policies that bring together structural transformation with a fair distribution of the growth dividend. To achieve this twofold objective, Thailand needs to improve human resource development, encourage technology diffusion, promote innovation and digitalisation, improve the SME policy framework and expand regional integration. Innovative regional policies will ensure prosperity spreads throughout the regions.

Table 1.2. Prosperity – four major constraints

|

1. Slow economic transformation within sectors and across regions holds back productivity growth. |

|

2. Low innovation and research with limited commercialisation potential adversely affect competitiveness and productivity. |

|

3. SME access to financing is costly and constrains development. |

|

4. Some cross-border barriers to services trade and investment remain significant, notwithstanding ongoing liberalisation in the context of ASEAN. |

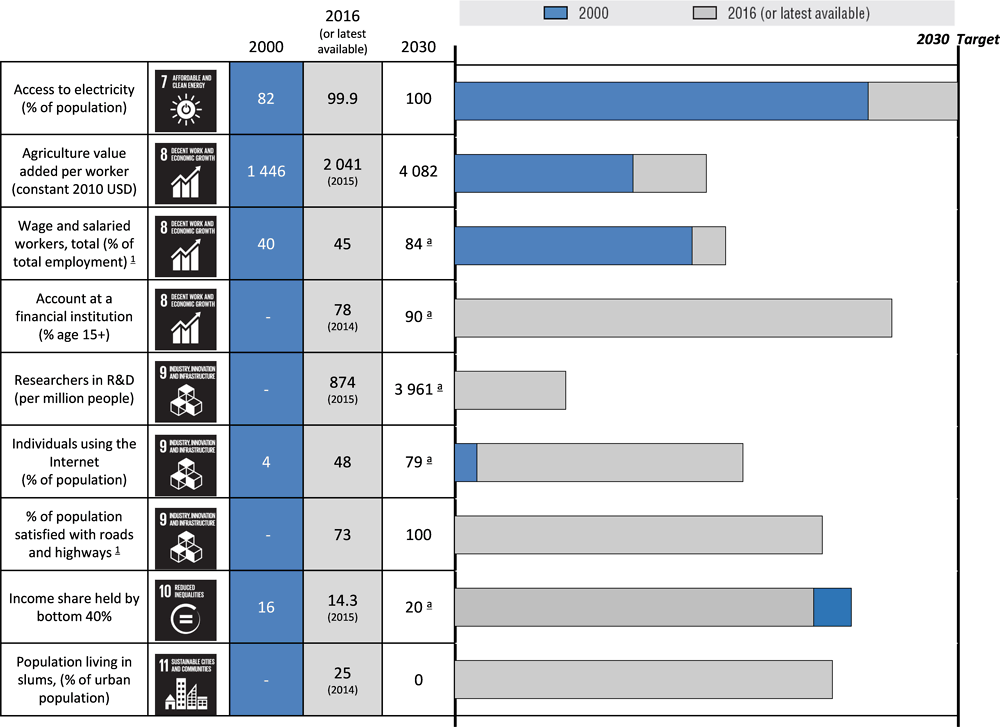

Figure 1.5. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Prosperity

Note: The bars measure Thailand’s performance in 2000 and 2016 (or latest year – as indicated accordingly) for a selection of 26 indicators across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indicators are chosen in line with the UN global framework and to ensure measurability. The 2030 aspirational target values refer to the pre-defined UN target (established by the UN IAEG and available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/metadata-compilation/). Targets are all normalised to 100 for representation and comparison purposes.

a. When UN 2030 targets were not quantifiable, targets were calibrated to the average performance of OECD countries, in accordance with the methodology outlined in a recent OECD study on measuring distance to the SDGs targets (OECD, 2017[4]). However, the target for “Total debt service” was calibrated to the average value of the top 3 performers in the ASEAN region, due to data unavailability in OECD countries.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

Slow economic transformation holds back productivity growth. To attain high-income country status, Thailand’s economic growth needs to be driven by productivity gains, rather than by the sheer accumulation of capital and labour inputs. Accordingly, Thailand’s 12th Plan and Thailand 4.0 are pursuing an economic transformation where productivity improvements resulting from increases in innovation, human capital development, regulatory reform and infrastructure development drive growth. Traditionally, labour reallocation from the agricultural sector in rural areas to more advanced sectors in urban areas supports productivity improvements and is a key feature of catch-up growth and structural transformation. However, over the past 30 years, the contribution of labour reallocation to overall labour productivity growth has declined in Thailand.

To foster the development of more productive and higher value-added industries, the government aims to improve industrial value chains by strengthening linkages among firms, researchers and academic institutions, and public organisations within a geographical area. In particular, the government is targeting a set of priority sectors selected from those that have recorded strong export performance. The sectors consist of “First S-Curve” industries where the industrial base of pre-existing sectors would be upgraded (e.g. next-generation automotive, smart electronics, agriculture and biotechnology, and affluent medical and wellness tourism), and “New S-Curve” industries that can be developed through increased technological sophistication (e.g. robotics, aviation and logistics, biofuels and biochemicals, and digital and medical hubs). To this end, the government has launched a range of investment promotion measures and incentives in designated Special Economic Zones, which include the flagship Eastern Economic Corridor project.

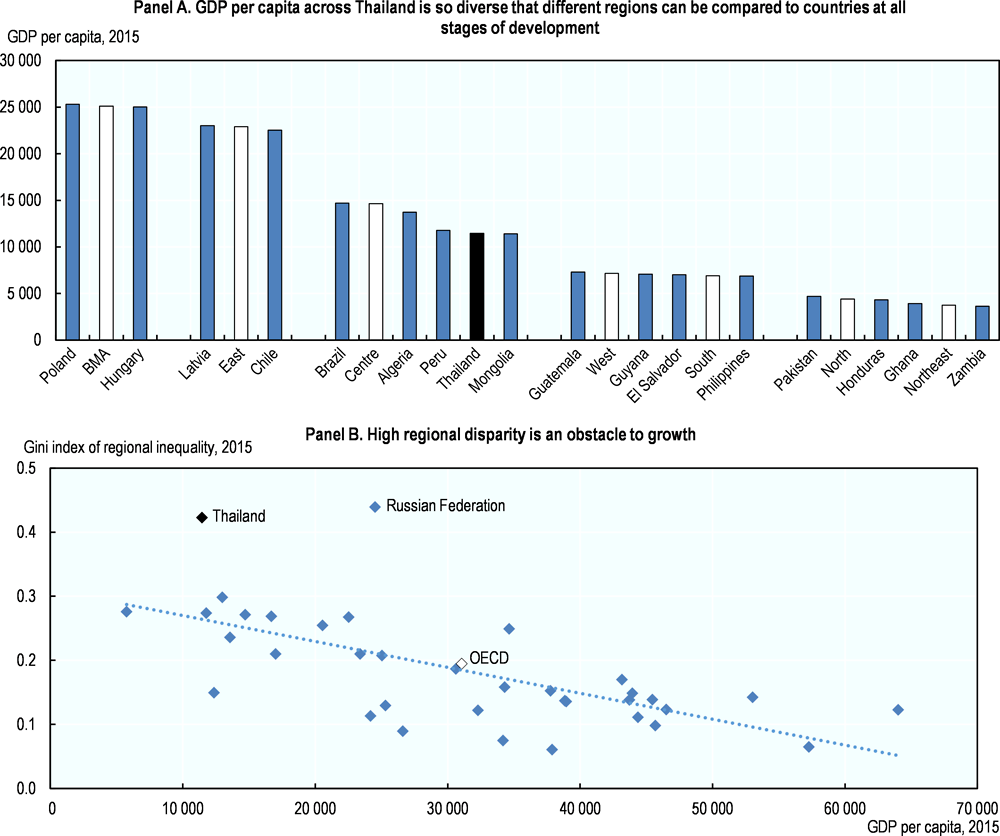

Large disparities between Thailand’s regions pose a significant obstacle to growth and structural transformation. The differences in per capita income between the poorest and richest regions of Thailand can be compared to the difference between Zambia and Poland (Figure 1.6, Panel A). Regional inequality may undermine growth. Only one other country (the Russian Federation) for which comparable data are available has reached a higher level of GDP per capita with a level of regional inequality as high as that of Thailand (Figure 1.6, Panel B). At such levels, workers and investments risk oversaturating labour and capital markets in already advanced areas; at the same time, poorer regions increasingly risk being left behind because of unfulfilled potential.

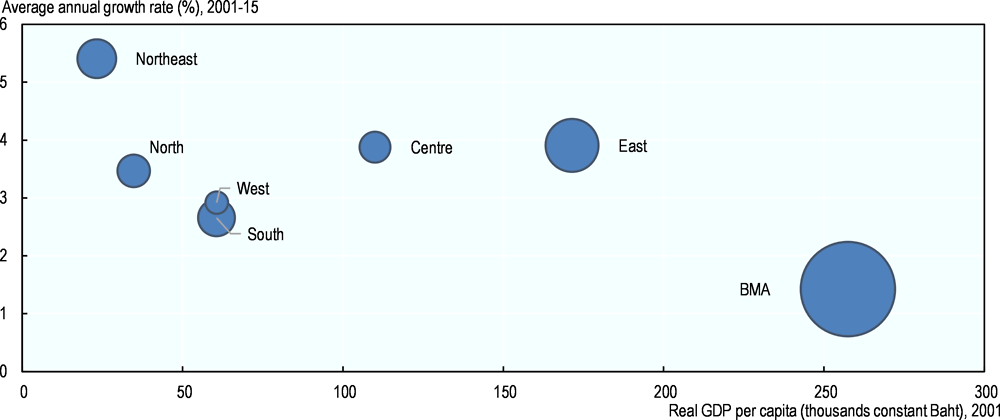

Yet, regional and provincial growth patterns suggest that much potential remains untapped outside the current centres. Although their levels are lower, the poorer regions of Thailand have shown consistently higher growth than Bangkok in both production and productivity since the beginning of the 2000s (Figure 1.11). The “catching-up” process has begun in some areas and has the potential to become a significant driver of further transformation if well supported. This calls for a dedicated approach to the development of all of Thailand’s regions.

Low innovation and research with limited commercialisation potential adversely affect competitiveness and productivity. Improving innovation in existing sectors is critical to boosting competitiveness and productivity, and to producing higher value-added products. However, Thailand’s innovation performance has either fallen behind or lost ground vis-à-vis some comparator East Asian countries. Governance issues including poor co-ordination and lack of clarity around institutional roles and responsibilities have hindered innovation. To address these issues, the government established the National Research and Innovation Policy Council in late 2016 as a single body to set the direction for research and innovation policy.

SME access to financing is costly and constrains development. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) generate about 42% of Thailand’s GDP, mostly in services. Promoting SMEs is crucial for economy-wide growth and reducing inequality between regions and individuals (Lee, Narjoko and Oum, 2017[9]). SMEs face a number of interrelated problems including inadequate financing, insufficient upgrading of capital stock and slower adoption of technology, as well as inadequate regional integration (Charoenrat, 2017[10]). The government has developed an SME Promotion Masterplan (2017-21) with the objective of increasing the SME share in GDP to at least 50% by 2021. Its priorities include streamlining licensing procedures, promoting skills training with an emphasis on ICT, and providing entrepreneurship education and finance.

Figure 1.6. Global patterns suggest that the large disparities between Thailand’s regions pose a significant challenge to the transition to a high-income economy

Note: The Gini index measures the degree of inter-regional inequalities. An index equal to 0 implies no inequality – all resources are equally redistributed across the country. An index equal to 1 implies extreme inequality – all resources are concentrated in only one region. The analysis is based on OECD regional typology, and in particular on regional inequalities among Territorial Level 2 (TL2) regions. TL2 broadly corresponds to the first tier of subnational government. For comparative purposes, TL2 regions in Thailand correspond to the country’s 77 provinces.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on national accounts, as provided by NESDC and (World Bank, 2017[11]).

Global value chain (GVC) participation and regional integration are progressing, but some cross-border barriers to services trade and investment remain significant. Trade and foreign investment have long been major drivers of Thailand’s industrialisation. Foreign trade amounted to 118% of GDP in 2016, more than double the OECD average, reflecting active participation in GVCs. Making the best of opportunities brought about by participation in GVCs calls for efficient and cheap access to imported intermediate and capital goods. In this regard, Thailand has made substantial progress, almost halving the weighted applied mean tariff rate for manufacturing goods over the past decade. Trade liberalisation and facilitation has lagged somewhat in the services sector, which accounts for close to 60% of GDP in Thailand, but is key to productivity and competitiveness. Open and well-regulated services markets are the gateway to GVCs, ensuring access to information, skills and technology, reducing costs and improving service quality (OECD, 2017[12]). This is true in particular for digital, logistics and professional services used in high value-added activities. However, a pilot project to compute the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index for Thailand shows that the country’s regulatory framework creates international trade impediments in both the construction and architecture service sectors.

Partnerships

The Partnerships pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development cuts across all goals focusing on the mobilisation of resources needed to implement the agenda. Thailand’s “sufficiency economy philosophy” encourages the prioritisation of long-term sustainability over short-term benefits. As such, Thailand has a long history of fiscal prudence that has served the country well in times of economic and political instability. However, the country’s rapidly ageing population and shrinking workforce will exert pressure on public finances over the medium term.

Table 1.3. Partnerships and financing – three constraints

|

1. Despite a sound fiscal position, current revenue will not suffice to fund commitments over the medium term. Further improvements to the tax mix are needed to foster growth and competitiveness. |

|

2. Inefficient infrastructure financing increases costs, emphasising the importance of identifying efficiencies. |

|

3. The public cost of healthcare and pension systems will grow and become increasingly unaffordable. |

Despite a sound fiscal position, current revenue will not suffice to fund commitments over the medium term. Further improvements to the tax mix are needed to foster growth and competitiveness. Over the past five years, Thailand’s total tax collections averaged about 18% of GDP, up from 14% in 2000 (OECD, 2018[1]). This is broadly in line with regional comparators, but much lower than the OECD average and insufficient for investing in Thailand’s ambitions for 2037. Recognising the need to boost revenues, the government has set a target of raising total tax collection to 20% of GDP by 2020. To broaden the tax base, Thailand should consider gradually widening the VAT scope and raising its rate, using additional revenues to fund targeted increases in social protection.

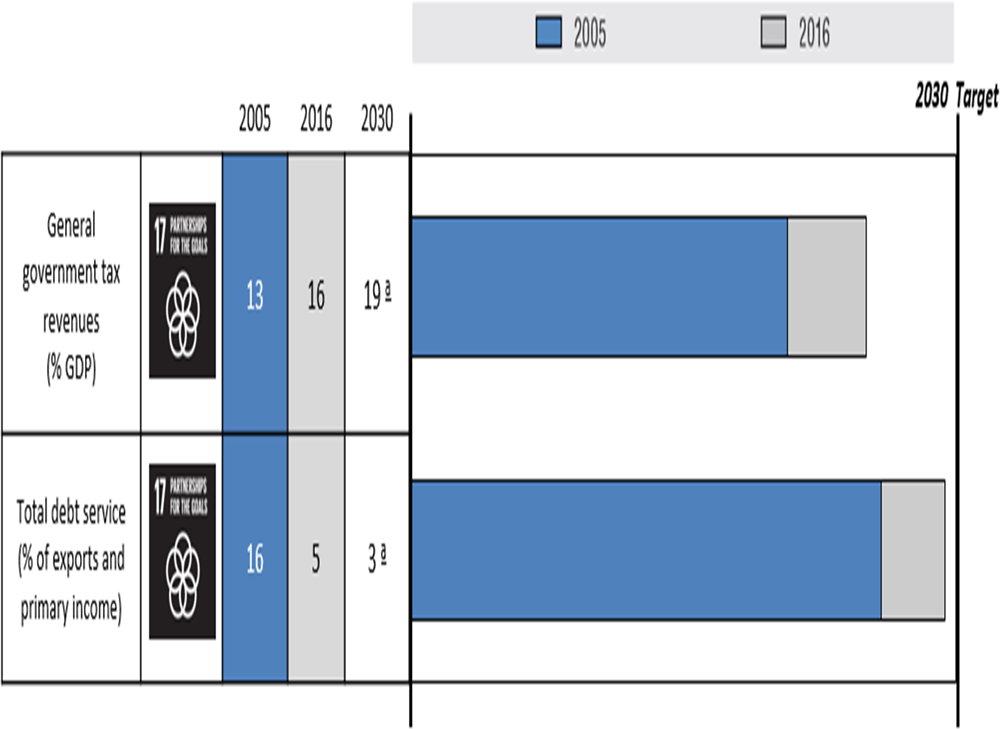

Figure 1.7. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Partnerships

Note: The bars measure Thailand’s performance in 2000 and 2016 (or latest year – as indicated accordingly) for a selection of 26 indicators across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indicators are chosen in line with the UN global framework and to ensure measurability. The 2030 aspirational target values refer to the pre-defined UN target (established by the UN IAEG and available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/metadata-compilation/). Targets are all normalised to 100 for representation and comparison purposes.

a. When UN 2030 targets were not quantifiable, targets were calibrated to the average performance of OECD countries, in accordance with the methodology outlined in a recent OECD study on measuring distance to the SDGs targets (OECD, 2017[4]). However, the target for “Total debt service” was calibrated to the average value of the top 3 performers in the ASEAN region, due to data unavailability in OECD countries.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

Identifying potential efficiencies in the provision of public infrastructure will also be important to reduce the public expenditure burden. Thailand could consider additional infrastructure financing sources to reduce the costs of investment and optimise risk allocation. In particular, infrastructure bonds priced in Thai baht can be less costly than bank financing and better match the long-term nature of such investments. Another way forward is to reinvigorate private sector involvement through improved public-private partnership (PPP) processes. In this regard, the government has sought to reduce red tape and improve bureaucratic efficiency, reforming PPP legislation in 2013 with the introduction of time limits and standardised contracts. Furthermore, Thailand has set up a Future Fund to provide additional instruments to finance major transportation infrastructure.

The public cost of healthcare and pension systems will grow and become increasingly unaffordable. In relation to pensions, Thailand’s shrinking labour force and longer retirements mean that there are fewer work years available to support the burgeoning number of retirees. Thailand’s private pension scheme has a pensionable age of 55, while the public sector scheme and the social pension both have a pensionable age of 60. OECD research suggests that postponing retirement is an efficient way to both boost retirement income and improve the financial sustainability of the system (OECD, 2013[13]) Thailand could align the pensionable age of the private pension scheme with the public sector and social pension scheme, and progressively increase the official retirement age in line with life expectancy. Moreover, the government could slowly increase the private sector contribution rate, which is currently below most comparator countries and the OECD average.

Planet

The Planet pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development covers six environmental areas: water, clean energy, responsible production and consumption, climate action, life below water and life on land.

Thailand’s natural environment is a vital asset and underpins key economic sectors and millions of livelihoods. As in many emerging economies, rapid economic growth has been achieved through intense use of natural resources, which has exerted a heavy environmental toll. Greater attention to environmental issues began in the 1990s, and resulted in the adoption of a framework law that established the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment, and introduced instruments such as Environmental Impact Assessments. Today, renewed commitment to environmental concerns is warranted, as progress on this front has slowed or even reversed in some cases. Thailand’s sustainable development rests on wise management of its natural resources, minimisation of pollution to protect the health of people and ecosystems, and a transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient future.

Table 1.4. Planet – five constraints

|

1. Highly fragmented water management is leading to overlapping responsibilities, conflicting interests and a lack of co-ordination. |

|

2. The repeated pattern of floods and droughts causes loss of life and economic disruption. |

|

3. Environmental quality of life is undermined by insufficient progress on air and water pollution, and waste generation. |

|

4. Current power sector plans may lock Thailand into a more carbon-intensive path. |

|

5. The governance framework does not sufficiently integrate environmental concerns into public plans and policies. |

Thailand is exposed to cycles of flooding and drought that cause loss of life and economic disruption. While natural climatic variables are important drivers of these phenomena, other policy-amenable factors are also at play. Poorly planned urban expansion, the intensification of agriculture, and the deterioration or loss of watershed forests have led to the decline of flood-retention areas and flood plains, while water consumption behaviours, agricultural and industrial land development, urbanisation and population growth have contributed to droughts.

Water management in Thailand is characterised by a highly fragmented institutional framework leading to overlapping responsibilities, conflicting interests and a lack of co-ordination. The government has also tended to focus on hard infrastructure and supply-side solutions, while demand-side measures have received less attention. Thailand would benefit from a more holistic approach to water management and flood defence, complemented by a disaster risk management approach that is sufficiently funded and ensures that local levels have the capacity to prepare and respond to natural disasters.

Challenges remain in securing environmental quality of life, particularly with regard to air pollution and water and waste generation. Levels of some air pollutants, such as PM2.5 particles, have been creeping up since 2010, after modest improvement in the years after 1990. The problem is particularly acute in pollution hotspots such as the country’s major industrial zones, where air pollution frequently exceeds safe limits. Water quality has been improving incrementally, but 23% of surface water is still assessed as poor quality. Greater progress is being held back by a lack of wastewater treatment facilities (only 15% of municipal wastewater is treated), poor compliance with existing regulations and the absence of financial disincentives to pollute. Finally, solid waste generation is a growing problem, as is the case in many countries in the region. The quantity of solid waste has increased by 80% since 2000, and 43% of waste is disposed of inappropriately through open burning or illegal dumping. The composition of waste, however, shows a high potential for reuse: up to 60% could be composted, recycled or used for energy generation. Appropriate pricing mechanisms are also needed to provide incentives to reduce the absolute quantity of waste generated.

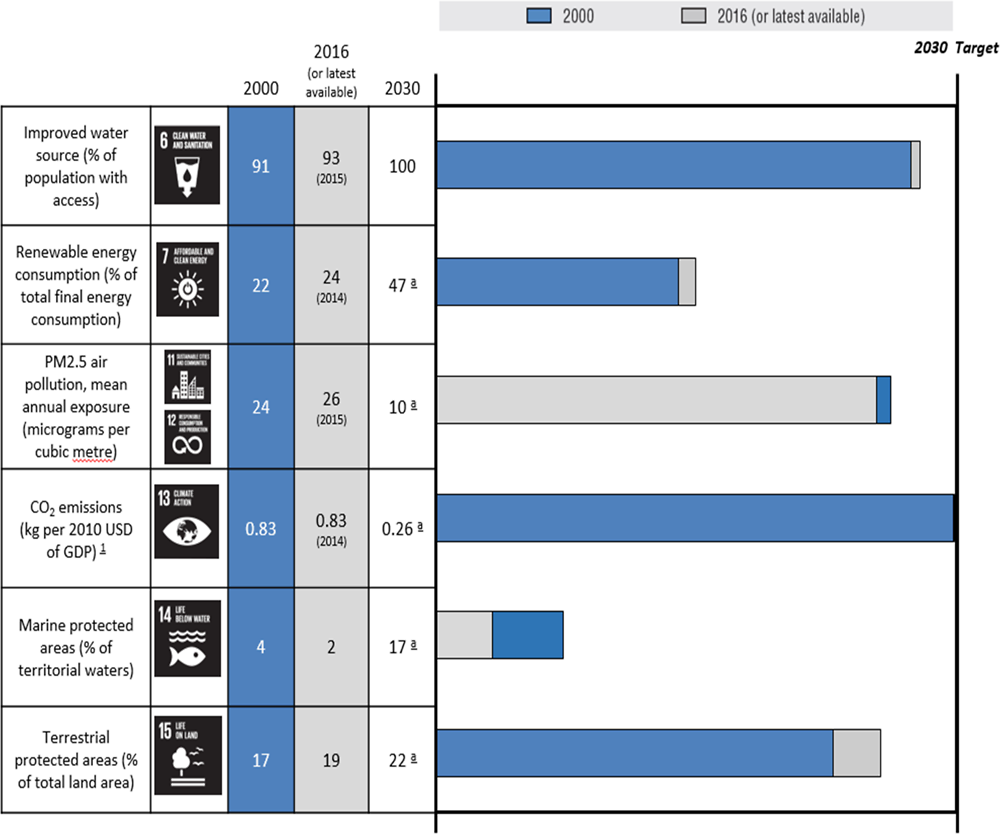

Figure 1.8. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Planet

Note: The bars measure Thailand’s performance in 2000 and 2016 (or latest year – as indicated accordingly) for a selection of 26 indicators across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indicators are chosen in line with the UN global framework and to ensure measurability. The 2030 aspirational target values refer to the pre-defined UN target (established by the UN IAEG and available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/metadata-compilation/). Targets are all normalised to 100 for representation and comparison purposes.

a. When UN 2030 targets were not quantifiable, targets were calibrated to the average performance of OECD countries, in accordance with the methodology outlined in a recent OECD study on measuring distance to the SDGs targets (OECD, 2017[4]). However, the target for “Total debt service” was calibrated to the average value of the top 3 performers in the ASEAN region, due to data unavailability in OECD countries.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

The governance framework does not sufficiently integrate environmental concerns into public plans and policies. Thailand has set ambitious greenhouse gas reduction targets – intended to cut emissions by 20-25% from the projected business-as-usual level by 2030 – and has identified energy and transport as key sectors for mitigation efforts. Some features of current energy plans, however, may be inconsistent with international commitments, which are set to become increasingly stringent. In particular, the planned increase in the share of coal in the energy mix will raise the absolute level of carbon emissions. On a positive note, the share of renewables is also slated to rise under current plans. Thailand could be even more ambitious in its adoption of renewables by exploiting untapped potential in the solar photovoltaic sector. It could also consider higher environmental taxation.

As one of the countries most exposed to the impacts of climate change, Thailand’s mitigation efforts need to be complemented by adaptation. In this regard, the 12th Plan and the National Climate Change Master Plan 2015-2050 aim to enhance the country’s ability to adapt to climate change. This is a welcome move as adaptation is largely neglected in current sectoral plans. The true test will be whether these high-level plans translate into awareness, mainstreaming and implementation of adaptation measures across all sectors from national to local levels. Implementation will require effective central co-ordination involving all relevant stakeholders, a strong evidence base (e.g. for climate projections), capacity building (especially at local levels), sufficient financing, and mechanisms for monitoring, evaluating and adjusting approaches.

Peace

The Peace and Institutions pillar of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development encompasses a diverse range of issues including peace, stability and trust, as well as effective governance and the performance of the public sector more broadly.

Reforming the public sector is high on the government’s agenda, but involves four main challenges. First, the gap between planning and implementation of policy objectives remains large. Second, insufficient public participation in policy making is undermining the efficient allocation of resources toward public needs and development goals. Third, under-development of evidence-based regulations is hampering the creation of a business-friendly environment essential to high value-added activities. Finally, high levels of perceived corruption are weakening business confidence and public trust in the government.

Table 1.5. Peace – four constraints

|

1. Institutional capacity to implement reform falls short, including with respect to co-ordination across ministries and agencies. |

|

2. Imbalance between central and local governments hinders policy reform. |

|

3. Competition legislation has not been adequately enforced. |

|

4. Current corruption levels are high and require strong government measures. |

Imbalance between central and local governments hinders policy reform. Effective action at the local level is a crucial prerequisite for achieving Thailand’s ambitions; however, the authorities recognise the existence of inefficiencies at regional and local level, and have attempted to rationalise the tasks carried out by each layer of government. In practice, responsibilities over service delivery between central and local administrations often remain unclear, and local authorities lack the human capacity and the tools to improve local well-being. Moreover, the current governance design orients accountability upwards, towards central administrators, rather than downwards, towards citizens. In pursuing further decentralisation Thailand needs to sufficiently equip local authorities in terms of both technical capacity and fiscal resources to deliver on their increased responsibility.

Competition legislation has not been adequately enforced. With the adoption of the 1999 Trade Competition Act, Thailand became one of the first ASEAN countries to introduce competition policy. The Act covers both anti-competitive practices (agreements, abuse of dominant position and mergers) and some forms of restrictive/unfair trade and commercial practices. However, despite nearly a hundred complaints submitted since its enactment, there have been no findings of infringement.

A revised Trade Competition Act was adopted in 2017 against the backdrop of the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2015, which called for harmonised competition policies. It strengthens alignment with international best practice, including through the introduction of a prior approval merger control regime. Efforts have also been deployed to reform the Trade Competition Commission (TCC) to build a more independent legal institution, with its own budget and staff separated from the Ministry of Commerce.

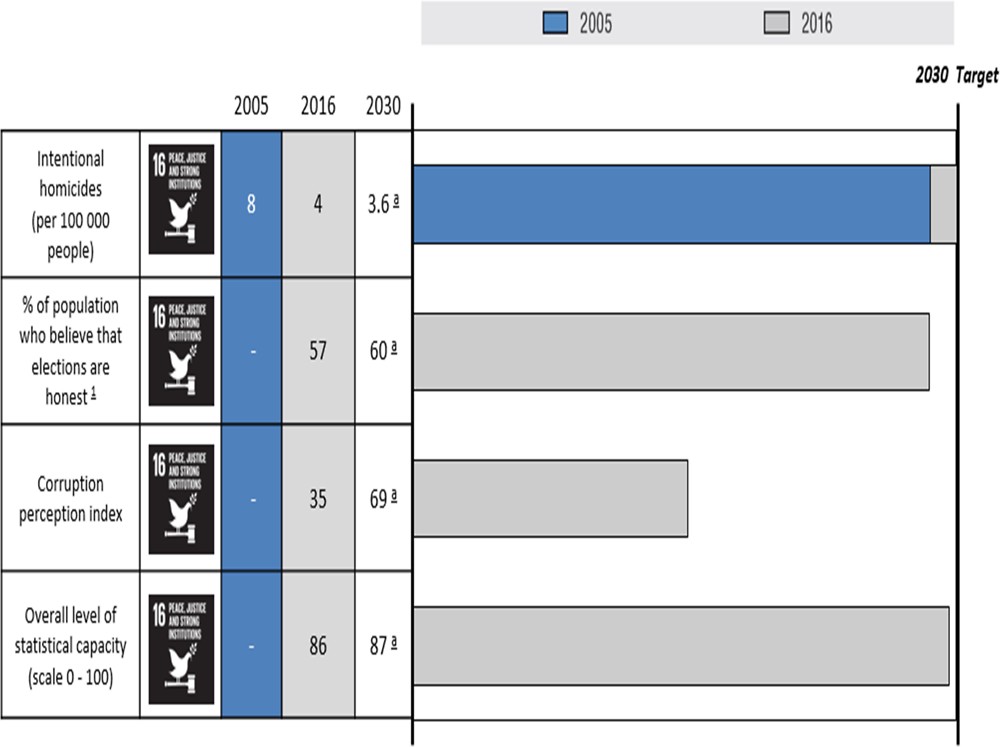

Figure 1.9. Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Peace

Note: The bars measure Thailand’s performance in 2000 and 2016 (or latest year – as indicated accordingly) for a selection of 26 indicators across the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Indicators are chosen in line with the UN global framework and to ensure measurability. The 2030 aspirational target values refer to the pre-defined UN target (established by the UN IAEG and available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/metadata-compilation/). Targets are all normalised to 100 for representation and comparison purposes.

a. When UN 2030 targets were not quantifiable, targets were calibrated to the average performance of OECD countries, in accordance with the methodology outlined in a recent OECD study on measuring distance to the SDGs targets (OECD, 2017[4]). However, the target for “Total debt service” was calibrated to the average value of the top 3 performers in the ASEAN region, due to data unavailability in OECD countries.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]).

Despite government efforts, corruption still holds back development. Thailand has long recognised the need to address corruption, which undermines trust and efficiency. Anti-corruption laws have increased and broadened over time, improving the independence and effectiveness of the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC). Even so, the perception of corruption remains higher than in the average of OECD and ASEAN countries, and over 40% of surveyed citizens report having to pay bribes, offer a gift or perform a favour for somebody when accessing public services.

To intensify anti-corruption efforts, the third phase of Thailand’s National Anti-Corruption Strategy (2017-2021) includes bold strategies to fight corruption and mitigate corruption risks. Thailand could consider streamlining the anti-corruption mandates of various institutions, particularly the NACC and the Public Sector Anti-Corruption Commission (PACC), in order to enhance the coherence of integrity and anti-corruption policies. Thailand could also benefit from further elaborating civil servants’ ethical obligations and ethics training. Setting high ethical standards would help to restore trust in the public sector and the proper use of public funds. In addition, Thailand could develop a dedicated whistleblower protection law to clearly define the scope of whistleblowing, wrongdoings and retaliation, and offer protection to whistleblowers. This would foster an open public organisational culture where integrity concerns can be discussed, leading to effective detection of ethical violations.

Distilling the cross-cutting challenges

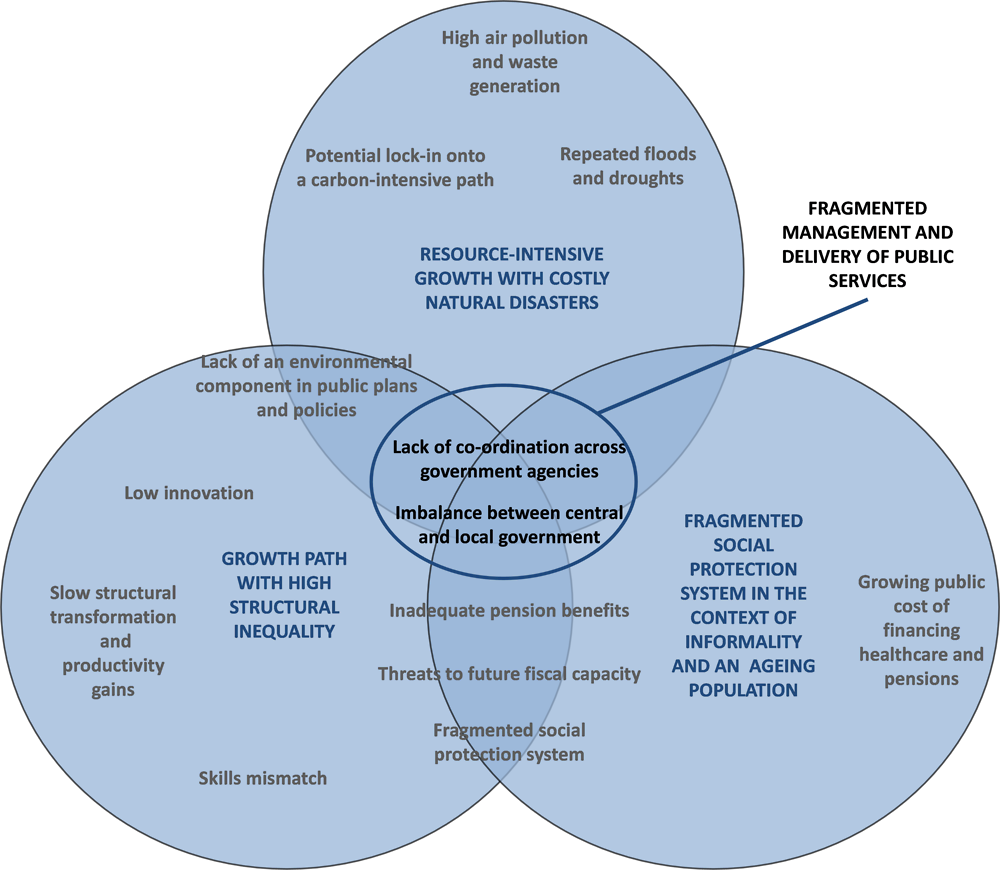

Four cross-cutting challenges emerge from these individual constraints. The Initial Assessment identified 20 constraints spanning the economy, society, government and the environment in Thailand. Mapping these constraints into a context of mutual relationship points to four cross-cutting challenges for Thailand’s development (Figure 1.10): a growth path with high structural and regional inequalities, resource-intensive growth with costly natural disasters, a fragmented social protection system in the context of informality and an ageing population, and fragmented management and delivery of public services.

Thailand needs to transition from a growth path with structural and regional inequalities to one that provides quality jobs for all. The share of basic agricultural and precarious urban employment remains disproportionally high given the level of GDP per capita. Informality impedes productivity growth, entrenches inequality and reduces the tax base. At the same time, the difference in regional economic and social performance remains too large. Better public services, especially in education, infrastructure and business facilitation, reaching all parts of the country, will be key to reinvigorating economic transformation and creating new activities that provide income and security for the whole population.

Figure 1.10. Thailand’s four transversal challenges

A more accessible and better financed social protection system is essential in the face of an ageing population and continuing high informality. Thailand’s age profile is more in line with high-income countries such as Korea and Singapore than regional comparators like Malaysia or Viet Nam. Accordingly, the country has struggled to ensure universal social protection coverage, notwithstanding successes in healthcare. A rapidly ageing population makes it harder to strengthen social protection while maintaining long-term fiscal sustainability. Thailand will need to widen social protection and implement skills upgrading to enable productivity growth to compensate for declining labour input.

Thailand also needs to transition from resource-intensive growth against a backdrop of costly natural disasters to more sustainable development with better-managed natural resources, enhanced disaster risk management and reduced pollution. Rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and intensive agriculture have put pressure on water resources and water quality. The government therefore needs to strengthen water resources management and limit the negative effects of natural disasters. Attention also needs to be paid to improving air quality and reducing waste generation.

Finally, the organisation of government and public service delivery lie at the intersection of the previous three development challenges. The different levels of government in Thailand need to overcome co-ordination issues and integrate more effectively. Under the current system, the complex organisation and uneven distribution of power and resources across central government bodies and local administrations contribute to co-ordination problems and poor institutional capacity. Political participation and accountability should therefore be coupled with reforms that aim to fiscally empower local municipalities, such as building local capacity to raise revenue and determine expenditure, and guaranteeing transparent and fair access to intergovernmental grants.

Building policy recommendations: Thailand must implement three transitions to reach the next level of development

Further prioritisation identified three key transitions Thailand must implement to overcome the cross-cutting challenges and reach the next level of development. First, Thailand needs to unlock the full potential of each of its regions and build on convergence as a driver of structural transformation. Second, the country needs to develop a more effective organisational approach to multi-level governance, particularly with regard to financial resources. This is a crucial capability to support the new growth agenda. Under the current system, the complex organisation and uneven distribution of power and resources across central government bodies and local administrations contributes to co-ordination problems and poor institutional capacity. More effective multi-level governance is also crucial for the third transition, which pertains to water and the environment. Moving from a resource-intensive growth path with costly natural disasters to one characterised by sustainable development will require a new approach. In the case of water, this means moving from ad-hoc responses to effective management of water security.

Figure 1.11. Poor regions have grown faster than richer ones, displaying potential for convergence

Note: Calculations are based on chained volume measure of real GDP per capita. The Compound Average Growth Rate (CAGR) is used to measure the evolution of real GDP from 2001 to 2015. The size of the circle is proportional to the share of regional GDP to national GDP.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on national accounts, as provided by NESDC.

A new growth path: Unlocking the potential of Thailand’s regions

Thailand’s growth path has created large disparities that now represent obstacles to the next stage of development. Past approaches to regional strategies gave rise to path dependence in productivity growth and affected regional productivity potential. Taking a closer look at Thailand’s peripheral provinces and cities suggests that convergence has started; however, not all laggards have caught up (Figure 1.11). To make the most out of the potential of convergence, Thailand must develop the necessary capabilities in terms of organisation and economic geography.

Going forward, Thailand will need more broad-based and innovative regional policies that put local innovation in the driver’s seat, provide flexible support, and capitalise on best practises and learning from top performers. An analysis of provinces at the productivity frontier points to superior human capital and public services as the distinguishing attributes of high-performing provinces and cities. Based on these insights, regional policies will need to support cities as the centrepieces of integrated regional development policies and focus on skills development as a tool of regional and urban policy.

Moving towards more broad-based and innovative regional development policies

The new agenda for regional development must balance economic, social and environmental objectives. Past interventions aimed at boosting development in Thailand’s regions have focused solely on growth in small areas. Future strategies should aim at combining a broader set of objectives, including social cohesion and environmental sustainability. The right mix between social and economic as well as environmental objectives may vary across the country.

Getting regional development planning right will require placing local innovation and discovery in the driver’s seat. Mastering this process of discovery at each level (national, regional and local) is key to successful economic development and continued productivity and employment growth. The overarching lesson from the “smart specialisation” agenda and past attempts at regional development in the European Union and elsewhere is that this process of discovery must be driven and mastered by local and regional actors. The role of government intervention is important but it is subsidiary. Policy intervention is required not to select the areas or activities for investing public resources but to facilitate and support the discovery process (OECD, 2013[14]).

The process and instruments for innovative regional development should be performance-based, flexible, and reflect the specific needs and capabilities of each region. Placing local discovery and ownership in the driver’s seat of innovative regional development requires an open process that is adaptable to the needs of each region. More advanced regions might require less in terms of direct support and can be supported simply with mutually agreed performance targets and related instruments. Areas with lower capabilities might require more in terms of direct assistance and a stronger level of oversight to ensure accountability (OECD, 2018[15]). Strong evaluation and performance measurement frameworks must be built into all approaches from the beginning and should be widely accessible to guarantee transparency, as a key building block of local ownership.

Similarly, the geographic scope of regional development policies should be flexible and focus on functionality. The current administrative organisation in Thailand offers the opportunity to include flexibility in the definition of regions for the new strategies. Data analysis can help here to identify the most functional clusters of provinces for regional strategies. Functional areas may involve different provincial clusters and change over time. Neighbouring administrations that do not find co-ordination over specific issues particularly necessary today, may find it advantageous in the face of future global trends and shocks.

Data analysis should support local discovery processes, building on best performers to profile regions and provinces, assess potential and detect bottlenecks. Identifying each region’s best-performing province in terms of productivity, for example, helps to classify other provinces as “converging” or “diverging” with respect to specific objectives. This convergence-divergence analysis shows that most of the best-performing provinces inherited industrial estates created during the 1980s. In certain cases, agriculture, education and tourism have been pushing some provinces to the productivity frontier. Once regional best performers and their potential for productivity growth are identified, their characteristics can help devise policies for lagging provinces.

Supporting intermediary cities as engines of growth outside of Bangkok

Cities attract talent and economic development. Firms and workers are drawn to cities, thereby decreasing the cost of matching skills with the needs of enterprises in the labour market. Cities facilitate knowledge sharing and provide a vibrant environment to innovate and experiment. Hence, they help to retain the young and educated in regions that they would otherwise leave, leading to the depletion of human capital.

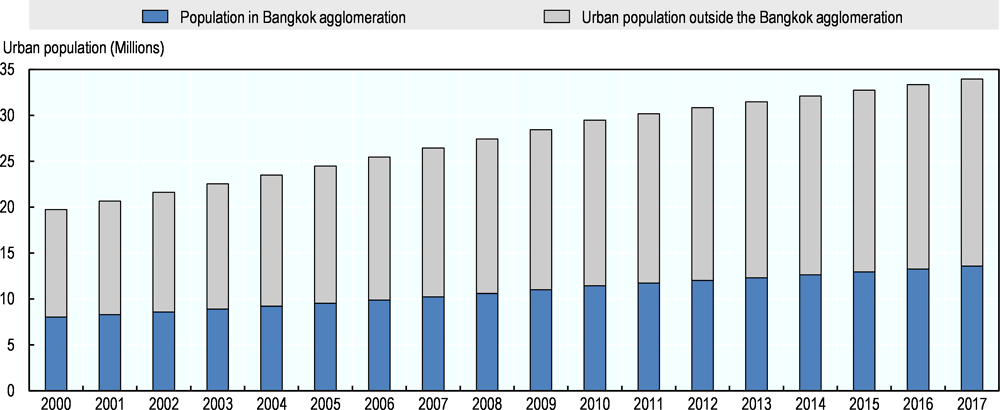

Cities can generate new opportunities for regional development outside of Bangkok, but need more resilient infrastructure. Since the beginning of the 2000s, intermediary cities in Thailand have been attracting more people than the capital, a trend that is increasing (Figure 1.12). In the North, urban centres such as Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai and Lamphun are attracting increasing numbers of people from rural areas who are looking for better salaries than those offered in smaller towns or for an alternative to the congestion of Bangkok. Urbanisation can become a powerful engine of regional growth, but it can also weaken citizens’ well-being and endanger the local environment in the absence of adequate local infrastructure.

Figure 1.12. Intermediary cities are attracting more people

Note: “Population in the Bangkok agglomeration” measures the number of people living in the Bangkok metropolitan area. “Urban population outside the Bangkok agglomeration” measures the number of people living in urban areas outside of the BMA.

Source: Authors’ work based on (World Bank, 2017[11]).

Policies to develop intermediary cities require a new definition of urban areas, which can be elaborated with the help of satellite data. Efforts to support cities with policy require a good understanding of what constitutes an intermediary city and where they are located. At present, there is no clear definition of urban areas in Thailand. However, geospatial data can help to identify intermediary cities by looking beyond traditional administrative boundaries. Satellite imagery of 41 identified intermediary cities show widespread urban agglomerations in the East, while density is highest in the West.

Targeted surveys should support satellite data by assessing the needs of intermediary cities, the structure of the local economy and its dynamics, and the state of local infrastructure. These intermediary cities can trigger growth outside Bangkok and across Thai regions. Unlocking their potential should be at the core of new integrated regional policies.

Intermediary cities need to have the capacity to respond to institutional fragmentation and challenges specific to their location. Cities outside of Bangkok are growing. Integrated regional policies need the right institutional framework to successfully improve the management of network services. Furthermore, citizen participation can help handle challenges such as large seasonal inflows of tourism. Thailand is a major global tourist destination. Seasonal inflows of tourists are an opportunity, but can dangerously stretch the capacity of intermediary cities. Therefore, involving people who live and work in the city in governing the phenomenon and shaping the appeal of their city is paramount to prevent or manage possible negative externalities.

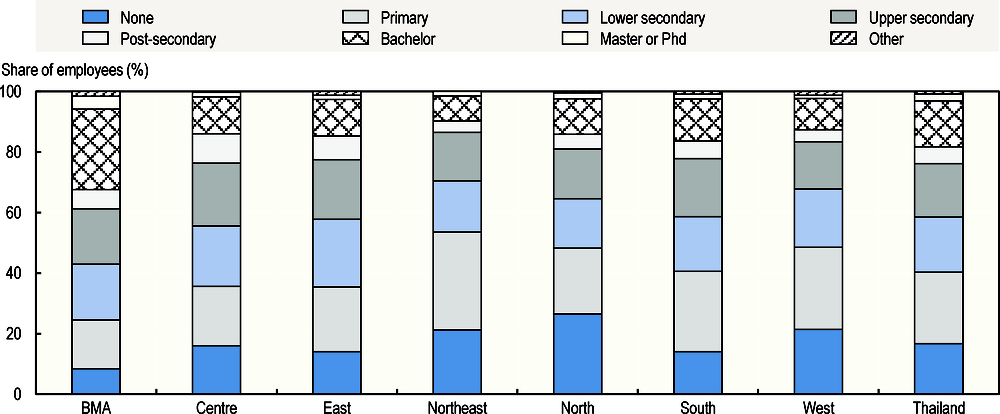

Figure 1.13. There is significant variation in educated workers across regions

Note: The category “None” includes workers that have neither started nor completed primary education. Employees included all Thai citizens aged between 15-60.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on Labour Force Survey (2016) and Socio-Economic Survey (2015).

Adjusting the education system to the regional ambitions

Secondary and tertiary education are important drivers of productivity growth at the level of provinces and must be core elements of regional policy. About 40% of workers have completed at least upper secondary education in Thailand, significantly below the OECD average of 80%. The share moreover varies from 54% in the Bangkok Metropolitan Area to 28% in the Northeast (Figure 1.13). Analysis of best-performing provinces shows that educational attainment is an important element of performance and is significantly lower among lagging provinces. Regional policies should focus particularly on technical and vocational education and training (TVET) concerning secondary education, and on provincial universities for higher education.

Thailand is home to leading universities, but provincial institutions are struggling despite their potential as powerful engines for local innovation and productivity growth. Research universities in Thailand are gaining ground in the global arena and have already introduced innovation into certain industries. However, the country could do more to leverage provincial Rajabhat universities and tighten the partnership between the local private sector and government.

International experience suggests that local tertiary institutions can stimulate local entrepreneurship and innovation. In addition, higher education institutions provide content and audiences for local cultural programmes that ultimately contribute to the appeal of a province. However, local universities can only play their role in development if local leadership enjoys enough autonomy to fine-tune coursework and teaching modalities to local economic structure and issues.

Making multi-level governance work for Thailand’s transitions

The new regional policy framework requires dynamic actors with the freedom to experiment at each level of government. Local and provincial layers of government need to be given the flexibility and means to experiment, as opposed to implementing top-down policies designed at the central level. Experimentation allows policy makers to learn from the “small-step” interventions they pursue to address local issues. Moreover, experimental processes require mechanisms that capture lessons and ensure that these are used to inform future activities (Andrews, Pritchett and Woolcock, 2013[16]).

Decentralisation was mandated in Thailand’s Constitution in 1999; since then, several decentralisation reforms with ambitious quantitative targets have been implemented. However, Thailand’s governance system remains highly centralised. Strong, central government control over subnational governments has not led to uniform service levels or harmonised revenue bases. On the contrary, there are marked fiscal disparities between Thailand’s subnational governments. Thailand’s dual multi-level governance and high number of subnational governments (LAOs) makes the governance system complex and fragmented.

There are four possible alternatives available for Thailand to tackle the current problems. First, a clear nationwide plan should be developed to prepare for reforming the subnational government structure, financing system, and spending and revenue assignments. Second, the LAOs should be empowered by enhancing their spending and revenue autonomy. Third, reorganisation of current spending assignments between government levels should be prioritised. Merger reforms or enhanced co-operation should be considered to build adequate capacity of subnational governments.

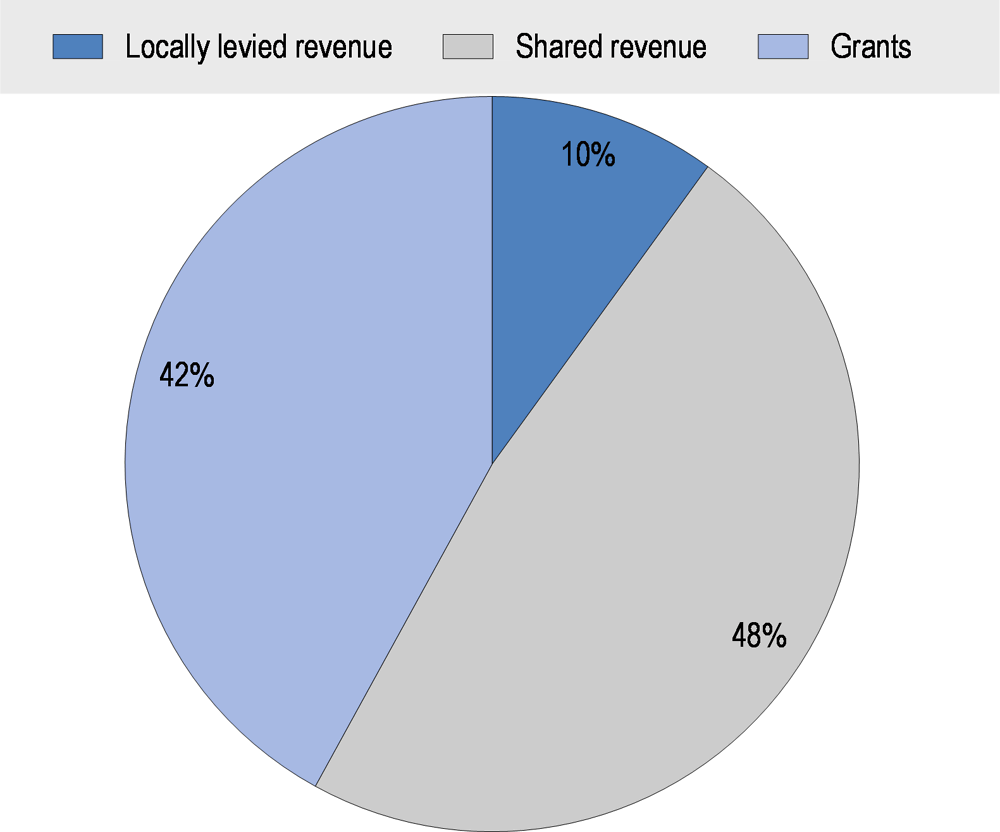

The fiscal autonomy of subnational government is weak, and the share of subnational tax revenue in total tax revenue is one of the lowest among Asia-Pacific countries. Locally levied revenues represent only 10% of the total revenues of local authorities. Lack of capacity to raise taxes forces local authorities to rely mostly on shared revenues – the rates of which cannot be controlled freely by LAOs – and intergovernmental grants (Figure 1.14). Intergovernmental grants further curb the spending capacity of LAOs, since the central governments earmark their distribution to the achievement of specific projects.

A stronger own revenue base would contribute to the self-rule and accountability of Thailand’s subnational governments. Reform of the financing system should include property tax reform and transfer system reform, but a considerable strengthening of local revenue base would include giving LAOs at least one important tax base. One option to consider would be to allow a local surtax on the central government personal income tax.

Figure 1.14. Transfers and tax sharing dominate local administration revenues

Furthermore, subnational capacities to finance infrastructure in order to contribute to regional development need strengthening, as does subnational capacity for strategic planning and territorial development.

Towards effective management of water security

Environmental challenges, in particular those relating to water, must be better managed. Thailand’s natural environment is a vital asset and underpins key economic sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing, with a direct impact upon millions of livelihoods. As in many emerging economies, rapid economic growth has been achieved through the intense use of natural resources, exerting a heavy environmental toll. Thailand is also exposed to cycles of flooding and drought that cause loss of life and economic disruption. While natural climatic variables are important drivers of these phenomena, inefficient water management practices hinder an effective response to these challenges. Poorly planned urban expansion, the intensification of agriculture, and the deterioration or loss of watershed forests have led to the decline of flood-retention areas and flood plains, while water consumption behaviours, agricultural and industrial land development, urbanisation and population growth have all contributed to droughts and increased pollution (OECD, 2018[1]).

Thailand’s water challenges can be captured under the overarching theme of “water security”, described as maintaining acceptable levels of risk in four main areas: the risk of water shortage, the risk of inadequate water quality, the risk of excess water and the risk of undermining the resilience of freshwater systems. In the Thai context, water security concerns issues related in particular to floods and droughts, water use and allocation, water quality and the impacts of pollution.

As poor water security will hold back Thailand’s growth plans, the government needs to move from a crisis response to a risk management approach. Data and information, cohesive policies, strong leadership, and clarity on roles, responsibilities and decision-making are necessary to facilitate the move to a risk-based approach to water security. In addition, better governance and co-ordination between local and national authorities on water management is needed. Thailand should also make better use of economic instruments such as water charges, and ensure stakeholder management and engagement to facilitate any reform.

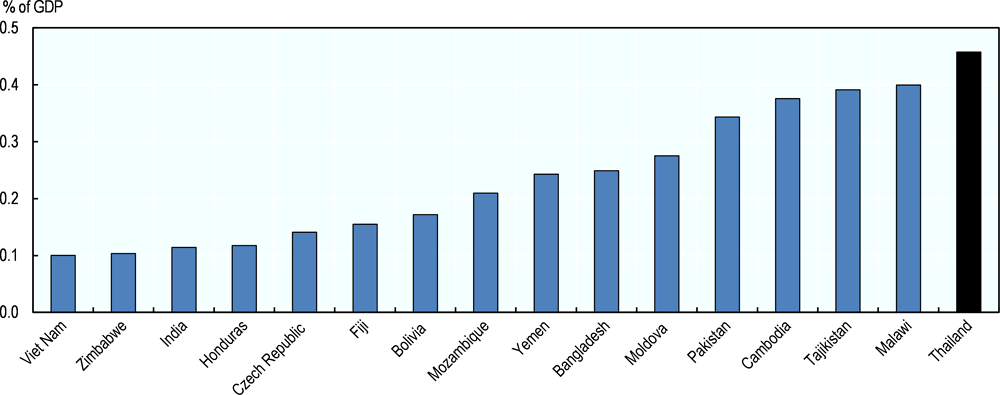

Regional development and water security are closely linked, as water security challenges affect the different regions of Thailand in a variety of ways. The Northeast region suffers from regular droughts but also flash floods, while the South is regularly hit by typhoons and floods. As a result, agricultural productivity in these regions (and the North) have suffered in recent years. Heavy industry and manufacturing is located in areas such as Rayong in the East, resulting in localised water quality challenges. However, the region can also be affected by flooding, as witnessed in 2011, when economic damage and losses from floods in the manufacturing sector were estimated at USD 32 billion (OECD, 2013[18]). As a result of the flooding, a number of international firms relocated to lower risk areas, impacting regional economies and Thailand’s international reputation. In general, annual average recorded damages account for a not insubstantial share of GDP (Figure 1.15).

Figure 1.15. Annual average damage from flood events as a share of GDP

Note: Annual average damage was calculated based on damage reported between 1971 and 2015 and converted to constant 2015 USD based on the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Historical Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). GDP figures are taken from the World Bank for the year 2014 in current USD.

Source: (OECD, 2016[19]) from EM-DAT.

Adopting a risk-based approach to managing water security will signify a shift from reactive to more proactive policies. Instead of responding to water crises, which can often entail excessive costs to society, governments can establish a process to carefully assess and manage risks in advance and review these on a regular basis. Once set, acceptable levels of water risks should be achieved at the least possible cost. Economic instruments, such as charging appropriately for water use and pollution, can help to achieve this (OECD, 2013[20])

References

[16] Andrews, M., L. Pritchett and M. Woolcock (2013), “Escaping capability traps through problem driven iterative adaptation (PDIA)”, World Development, Vol. 51, pp. 234-244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.011.

[3] Boarini, R., A. Kolev and A. McGregor (2014), “Measuring well-being and progress in countries at different stages of development: Towards a more universal conceptual framework”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 325, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/18151949.

[10] Charoenrat, T. (2017), Thailand’s SME participation in ASEAN and East Asian regional economic integration, Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, Vol. 34/1, pp. 148-174, http://dx.doi.org/10.1355/ae34-1f.

[5] Gallup (2017), Gallup World Poll, http://www.gallup.com/services/170945/world-poll.aspx.

[17] Laovakul, D. (2018), Country Profile: Thailand (unpublished memorandum).

[9] Lee, C., D. Narjoko and S. Oum (2017), Southeast Asian SMEs and regional economic integration, Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, Vol. 34, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/657954.

[8] MOE (2017), Education Development Plan 2017-2021 (in Thai), Ministry of Education, Bangkok, http://waa.inter.nstda.or.th/stks/pub/2017/20170313-Education-Development-Plan-12.pdf.

[6] NESDC (2017), Thailand Human Achievement Index 2017, http://www.nesdb.go.th/nesdb_en/download/article/social2-2560-eng.pdf.

[1] OECD (2018), Multi-dimensional Review of Thailand (Volume 1): Initial Assessment, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293311-en.

[15] OECD (2018), Rethinking Regional Development Policy-making, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264293014-en.

[2] OECD (2017), “How’s Life? 2017 Measuring Well-being”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/23089679.

[4] OECD (2017), “Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets: an assessment of where OECD countries stand”, http://www.oecd.org/sdd/OECD-Measuring-Distance-to-SDG-Targets.pdf.

[12] OECD (2017), Services Trade Policies and the Global Economy, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264275232-en.

[19] OECD (2016), Financial Management of Flood Risk, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257689-en.

[13] OECD (2013), Design and Delivery of Defined Contribution (DC) Pension Schemes. Policy challenges and recommendations, Cass Business School, London, http://www.oecd.org/daf/fin/private-pensions/DCPensionDesignHighlights.pdf.

[14] OECD (2013), Innovation-driven Growth in Regions: The Role of Smart Specialisation, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[7] OECD (2013), Southeast Asian Economic Outlook 2013: With Perspectives on China and India, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/saeo-2013-en.

[18] OECD (2013), Water and Climate Change Adaptation: Policies to Navigate Uncharted Waters, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264200449-en.

[20] OECD (2013), Water Security for Better Lives, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264202405-en.

[11] World Bank (2017), World Development Indicators (database), https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators (accessed on January 2019).