As part of the broader digitalisation of government activity, electronic procurement (e-procurement) is changing the way the public and private sectors interact. The benefits of this transition include increased efficiency in the execution of tenders, reduced cost of tendering for suppliers and improvements in the collection and use of data. Recent EU directives have imposed deadlines for the implementation of e-procurement in EU member states, yet low maturity in electronic tendering presents timeframe challenges for both contracting authorities and suppliers. This chapter identifies barriers to implementing e-procurement at different levels of German government. Notably, it discusses the complexity of the technological environment, the need to improve visibility of procurement information and enhance systematic data collection. Finally, the chapter offers avenues for expanding and systematising e-procurement usage by embedding efforts into change management plans, building on stakeholder engagement and linking e-procurement to the wider digitalisation agenda in Germany.

Public Procurement in Germany

4. Electronic procurement in Germany

Abstract

A continued challenge for governments is providing adequate public services while containing budgetary pressures (OECD, 2017[1]). In order to meet this challenge, countries have implemented reforms that seek to increase the effectiveness of the public sector, while improving the efficiency of government spending. The digitalisation of government activity presents an opportunity to increase the productivity of civil servants, while also radically improving government’s interaction with citizens, businesses and civil society. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement advocates for the use of electronic procurement (e-procurement) to achieve governmental objectives through the strategic use of public procurement (see Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement: Principle on e‑procurement

VII. RECOMMENDS that Adherents improve the public procurement system by harnessing the use of digital technologies to support appropriate e-procurement innovations throughout the procurement cycle.

To this end, Adherents should:

i. Employ recent digital technology developments that allow integrated e-procurement solutions covering the procurement cycle. Information and communication technologies should be used in public procurement to ensure transparency and access to public tenders, increasing competition, simplifying processes for contract award and management, driving cost savings and integrating public procurement and public finance information.

ii. Pursue state-of-the-art e-procurement tools that are modular, flexible, scalable and secure, in order to assure business continuity, privacy and integrity, provide fair treatment and protect sensitive data, while supplying the core capabilities and functions that allow business innovation. E-procurement tools should be simple to use and appropriate to their purpose, and consistent across procurement agencies, to the extent possible; excessively complicated systems could create implementation risks and challenges for new entrants or small and medium enterprises.

Source: (OECD, 2015[2]), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, http://www.oecd.org/gov/public-procurement/recommendation/.

In 2012, the European Union (EU) presented its view of the benefits of digitalisation of public procurement in member states. These benefits include:

significant savings for all parties

simplified and shortened processes

reductions in red-tape and administrative burdens

increased transparency

greater innovation

increased opportunities due to improved access for businesses to public procurement markets, including increased opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (European Commission, 2012[3]).

E-procurement promotes the diffusion of innovation, investment in knowledge-based capital and investment in information and communications technologies (ICT). E-procurement also enables the spillover of innovation and these investments to the greater economy (OECD, 2015[4]; OECD, 2013[5]; OECD, 2011[6]). Investment in e-procurement is particularly important for Germany. The German federal government’s spending on ICT is one of the lowest among OECD countries (OECD, 2015[7]). In addition, the government’s limited use of electronic governance and procurement techniques, along with restrictive regulations on certain sectors (e.g. telecommunications), hampers growth and valuable competition (OECD, 2017[1]).

A 2017 OECD review of economic policy in Germany found that the country’s “government administrations make little use of electronic governance and procurement techniques” (OECD, 2017[1]). In response, Germany has renewed its focus on increasing the reach and use of electronic procurement. In addition the growing appreciation of the benefits of e-procurement, Germany is taking steps to increase the use of electronic procurement because of legislative timeframes imposed by the European Union. These timeframes aim to encourage the adoption of e-procurement among member states.

As discussed above, the proliferation of e-procurement globally, as well as in Germany, has resulted in efficiencies for procurement practitioners and suppliers (OECD, 2017[8]). However, those efficiencies can be eroded where systems are not designed to avoid mistakes and repetitive tasks and to streamline processes such as data collection. The benefits of e-procurement may seem apparent, yet the measurement of the benefits of e-procurement systems is still in its infancy. Among OECD countries, 66% do not measure the efficiencies or savings generated by e-procurement. A failure to understand or measure the impacts of e-procurement does mean, however, that countries will not still reap the benefits from its implementation (OECD, 2017[8]).

OECD stakeholder interviews revealed that the main barriers to realising the benefits of e-procurement in Germany are the following:

Many contracting authorities, in particular at the Länder (state) and municipal level, have not yet transitioned to the use of e-procurement platforms to execute tenders or broadly, to fully cover the procurement cycle.

Businesses in Germany do not have deep experience with using e-procurement to respond to public tenders.

Some of the e-procurement platforms that are currently used by contracting authorities, particularly in municipalities, do not seem to comply with national standards for sharing of tender information across platforms.

Germany does not collect procurement data on the activity that occurs across different e-procurement platforms for further use and analysis.

Germany has not integrated relevant information on procurement and economic activity held in different government databases at the federal level for comparison and analysis.

Systems are not widely used to manage other parts of the procurement cycle, including payment and contract execution.

The renewed focus on e-procurement in Germany has resulted in the initiation of a number of activities to meet the EU deadline. Germany’s approach to implementing these initiatives and overcoming the current challenges will determine the extent to which potential benefits from e-procurement are fully realised. This chapter analyses the current state of public e-procurement in Germany, its impact on the procurement system and the initiatives in place to make improvements. Based on a comparison with e-procurement practices in other countries, the chapter makes recommendations regarding e-procurement in Germany that are in line with international best practices.

4.1. The regulatory and system landscape for e-procurement in Germany

4.1.1. Implementation of the recent EU directives has provided an opportunity for Germany to enhance its use of e-procurement

At present, contracting authorities at all levels of government in Germany either: 1) do not use e-procurement platforms consistently; or 2) use a number of different platforms. This fragmented approach to the use of e-procurement makes it extremely challenging for federal or sub-national bodies to effectively monitor or analyse procurement activity across the country. This fragmentation also leads to inconsistencies in how government interacts with the supply market. As a result, the federal government has supplemented initiatives to digitalise procurement with an effort to gather data from contracting authorities on their procurement activities.

To encourage the adoption of e-procurement across Europe and ensure both governments and businesses benefit from the digitalisation of processes, the EU directives of 2014 required member states to comply with the following deadlines:

Tender opportunities and tender documents for tenders above the procurement value specified by the EU threshold had to be made electronically available by April 2016. (April 2016 was the date by which each country was required to transpose the revised EU directive to its country-specific legal system).

Central purchasing bodies were required to move to full electronic means of communication, including electronic bid submission for tenders above the EU threshold, by April 2017.

E-submission was made mandatory for all contracting authorities and all procurement procedures above the EU threshold starting in October 2018 (two years after the expected transposition of the revised directive by each member country) (European Commission, 2016[9]).

Germany’s first step towards meeting these milestones was to reform its federal procurement legislation. The recent reforms of German procurement law, which were based on the EU directives of 2014, aimed to achieve the following objectives in relation to e-procurement:

Electronic communication should be mandatory for the procurement process. However, small municipal procurement entities, as well as SMEs, must be given timeframe flexibility to fully achieve electronic processes.

At present, there is no reliable data on public procurement in Germany. Reliable statistics on public procurement needs to be generated through systematic data collection.

Two legal changes have been introduced in order to achieve these objectives:

The mandatory use of electronic communications and the corresponding milestones were enacted through changes made to the Law Against Restraints on Competition (Gesetz gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen, GWB).

An ordinance was passed (the Ordinance on Public Procurement Statistics, Vergabestatistikverordnung, VergStatVO) to mandate the collection of procurement-related data (as discussed in further detail in section 4.2.1).

The scope of the legislation to mandate the use of electronic communications in Germany covers all major stages of the procurement procedure. These stages include the provision of tender documents, the description of services via an online platform, the electronic submission of bids and the publication of contract notices. The transition to electronic means of communication is mandatory for all processes that are subject to procurement legislation, regardless of the good or service that is being purchased (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, 2017[10]).

The procurement legal framework (Code of Procedure for Procuring Suppliers and Services below EU-Thresholds, UVgO) has also been extended to include tenders below the EU threshold. According to the revised legislation, contracting authorities must implement electronic communications for tenders above the EU threshold by 2018. In the case of tenders below the threshold, contracting authorities must implement electronic communications by 2020. This excludes the procurement method of direct awards, which can be applied for procurements below a value of EUR 25 000. In order to be enacted beyond the federal government, these mandates will need to be included in the budget laws of each German state. As of the end of 2017, the city-state of Hamburg became the second state to implement the revised thresholds (Cosinex, 2017[11]).

In the course of advising member countries on the implementation of the e-invoicing directive, the EU suggested a number of approaches for national rollouts of e-procurement tools (European Multi-Stakeholder Forum on e-Invoicing, 2016[12]):

Individual public sector organisations may be integrated for operational purposes into a centrally provided infrastructure, such as a national portal or set of gateways through which public sector transactions are captured and then distributed to the various central, local and autonomous bodies making up the public sector.

In the absence of any centrally provided guidance, contracting authorities may be entirely free to decide on and implement their own e-procurement models.

Alternatively, contracting authorities may be required to establish their own models, but only in accordance with centrally provided guidelines or standards.

Currently, e-procurement in Germany most closely aligns with the third option (contracting authorities can establish their own models as long as they closely align with centrally provided guidelines). The federal system in Germany provides states with a large amount of autonomy over legislation and policy. Each state has an established way of working that does not always align with other states or the approaches taken by the federal government. Because of this, the federal government has attempted to introduce initiatives that co-ordinate activity and set common standards. These initiatives can then reap the benefits of a standardised way of working while respecting states’ autonomy.

Despite the fact that the federal government has a greater degree of control over contracting authorities at the federal level, co-ordination of e-procurement activity at the federal level can be challenging. At this level of government, fragmentation of approaches can persist. This fragmentation underscores how responsibilities for procurement governance are shared across several federal institutions in Germany. For example:

The Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) manages legislation dictating the use of e-procurement and all resulting statistical analyses of procurement data.

The e-procurement project (Projekt E-Beschaffung) is managed by the Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community, (Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat, BMI) and developed and implemented by a unit within the Federal Procurement Office of the BMI (BeschA).

A separate unit within BeschA manages the Kaufhaus des Bundes (KdB), an e-catalogue system for products and services from framework agreements. It is important to note, however, that four different central purchasing bodies develop these framework agreements.

The current focus on e-procurement activity through the implementation of the EU directives presents Germany with an opportunity to find an approach that can be harmonised across different levels of government. Various stakeholder groups should agree on the approach to ensure alignment across the different institutions that will have a key role in ensuring the effective implementation and use of e-procurement systems. At present, an inter-ministerial working group on e-procurement (UAG e-Beschaffung) exists at the federal level. By convening a broader working group on e-procurement at the national level, however, all relevant stakeholders (including representatives of the private sector) can be brought together to ensure that progress towards implementing the EU directives can be monitored. A broader working group would also enable practices to be shared with the goal of working towards standardisation.

4.1.2. The fragmented e-procurement environment requires co-ordination and governance in order to maintain common standards and alignment

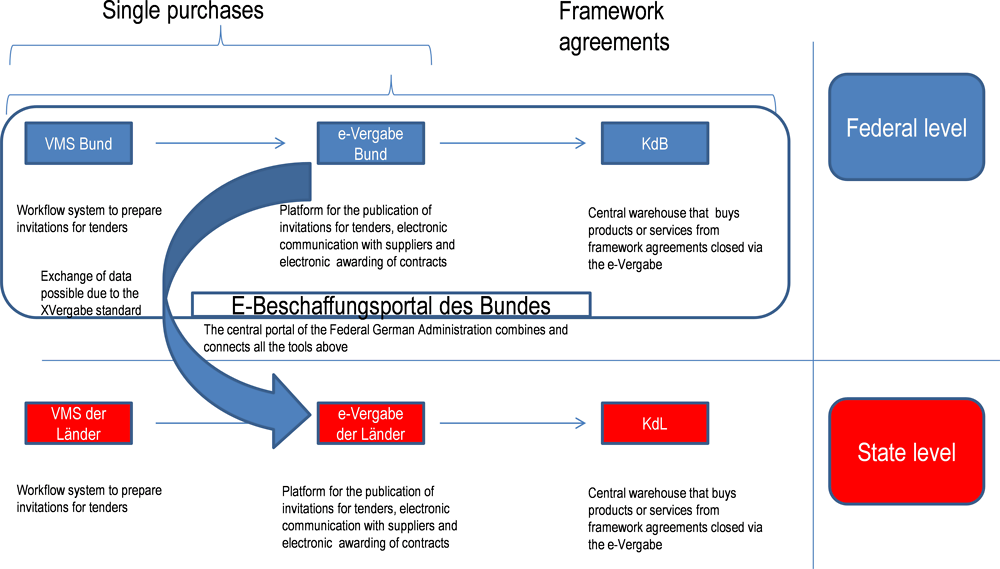

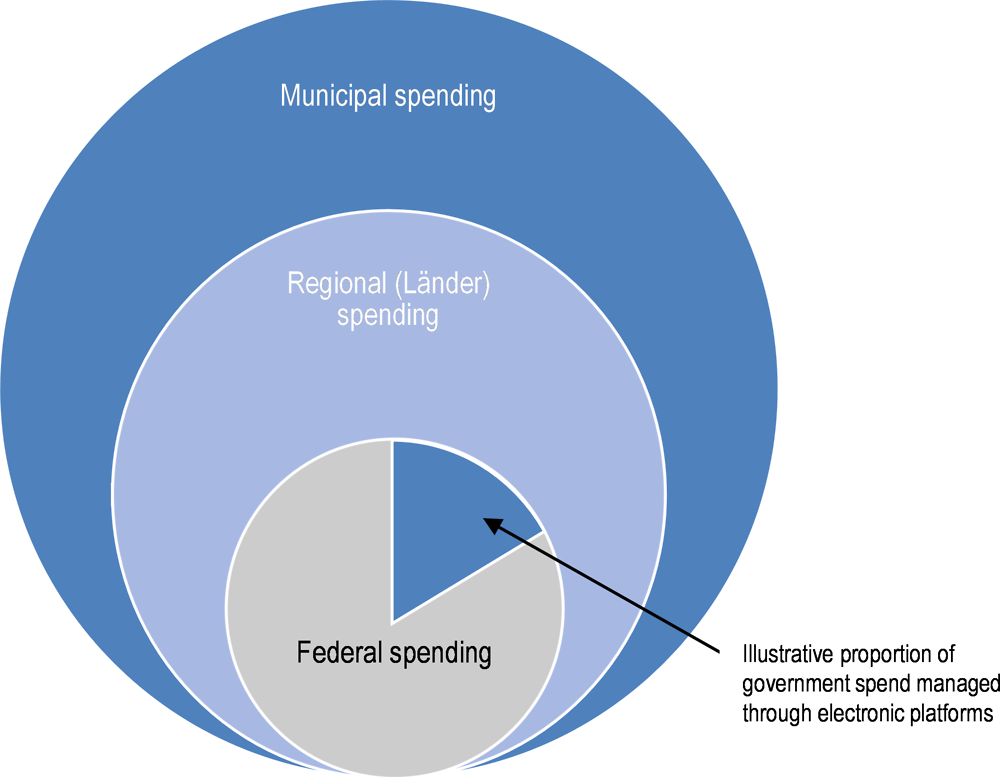

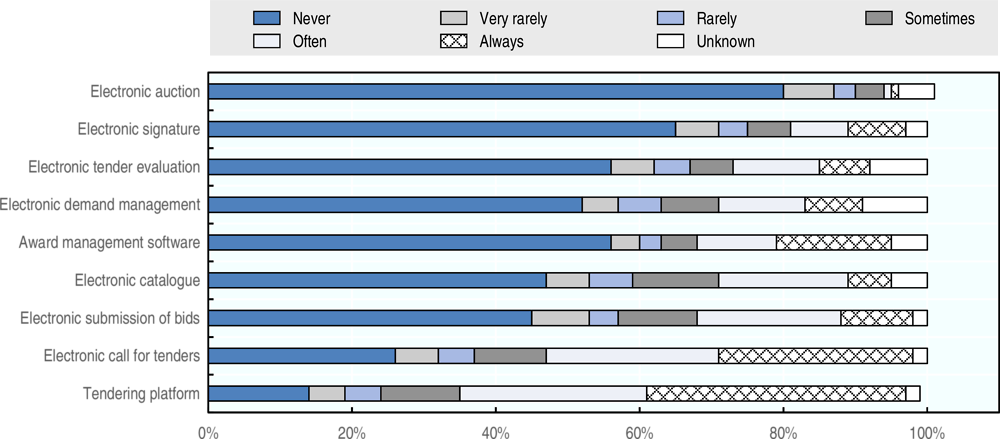

Germany’s federal system and the distribution of responsibilities for e-procurement across a number of different bodies have resulted in a fragmented approach to e-procurement. The variance in e-procurement practices across Germany is acutely apparent in the proliferation of different electronic platforms (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. E-procurement platforms used by contracting authorities across Germany

Source: Responses from German federal and state-level institutions to an OECD questionnaire and interviews.

As Figure 4.1 indicates, the lack of a mandatory e-procurement platform for Germany as a whole has resulted in an open e-procurement market. A number of firms compete to provide e-procurement services to contracting authorities, often competing with platforms that have been developed or managed by the government. The federal level of the German administration has been able to establish a mandatory e-procurement platform for all federal government agencies. This platform is not open to the Länder or municipal authorities, however. The open e-procurement market has led to a situation in which dozens of different platforms exist across different levels of government. To be able to manage tender processes for the federal government, these platforms must comply with federal procurement legislation. The systems used across the Länder must also be able to cater to regional differences in regulation. This system of multiple platforms tailored to different regulations ultimately impacts the ability of Germany to standardise systems across the country.

Over time, e-procurement systems and technologies have evolved. Portals that use the Internet as a communication tool to support traditional procurement have grown into digital tools that automate and increase the efficiency of the procurement process (United Nations, 2006[13]). The significant benefits of modern e-procurement systems include their ability to transfer knowledge and guide procurement staff through legal frameworks, as well as their ability to help staff follow best practices for procurement (EBRD; UNCITRAL, 2015[14]). In Germany’s fragmented environment, however, the automation and standardisation of processes through electronic tools has become increasingly difficult. This is unfortunate, given that procurement professionals are spread widely across 30 000 contracting authorities in Germany (see Chapter 6). This diffusion makes knowledge transfer and standardisation even more important, as such practices can build the capabilities of state- and municipal-level procurement staff.

Nevertheless, opening the e-procurement market to competition offered several benefits, such as providing contracting authorities with the freedom to choose the platform that is best suited to their needs or to the needs of a particular procurement. Opening the e-procurement market to competition also means e-procurement providers have the ability to supply innovative solutions to public buyers. This means public buyers do not have to choose from a monopolised market dominated by one given provider. In turn, this leads to a thriving market.

In order to overcome the challenges of fragmentation, Germany’s federal government took steps to build a level of standardisation across e-procurement systems. By building this level of standardisation, the government attempted to ensure interoperability among the various platforms across the country. As a part of these efforts, Germany developed a common e-procurement standard called xVergabe. XVergabe, according to the Procurement Office of the BMI, “defines a cross-platform data and exchange process standard between bidder clients and tendering platforms which ensures the compatibility of data processed by diverse procurement platforms”. The objective of the xVergabe project was to achieve broader participation in the digital bidding and awarding process. It sought to do so not by achieving standardisation of software products, but by ensuring that data could be exchanged between different platforms (Beschaffungsamt des Bundesministeriums des Innern, 2017[15]). As a result of this project, tenders posted by a contracting authority on a given platform are automatically transmitted to all other registered platforms, as well as (where applicable) to TED.

Thanks to the requirements that xVergabe puts onto platform providers, an automated import is able to export tender information to the federal platform (www.bund.de). This ensures that suppliers are able to visit one site in order to view all tenders above EUR 25 000. The xVergabe standard also introduces a functionality that ensures that suppliers who are registered on one compliant tender portal are automatically registered in all other compliant platforms, including at the state-level. However, according to stakeholder interviews conducted by the OECD, xVergabe has not yet been widely implemented at all levels of government. For example, some states indicated that, while most systems have enabled a connection between their system and the European e-procurement platform (TED), some e-procurement systems have been unable to connect to the federal system. Some authorities in Germany are concerned about the security of sharing procurement information across different platforms. At the same time, however, all over-threshold tenders posted in the majority of German states will be transmitted to TED. Unfortunately, this same functionality has not yet been implemented to enable connectivity across all of Germany.

As a result, a cottage industry of specialised service providers has sprung up in Germany to help economic operators identify suitable opportunities amongst the numerous e-procurement platforms used by government (European Commission, 2016[16]). However, not all suppliers are likely to have the time or resources to either conduct (or outsource) monitoring of a multitude of platforms for tender opportunities. This helps to explain why SME participation in public tenders has fallen (European Commission, 2017[17]). While the share of public contracts awarded to SMEs has increased, the fall in tender participation also correlates to a fall in the number of businesses submitting tender responses electronically (European Commission, 2016[18]).

The new EU directives specifically mention that tools and devices used for communicating tender information electronically should be non-discriminatory, generally available, interoperable and in alignment with the principles of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement. This means that electronic platforms should not restrict the ability of a company to participate in a public procurement procedure. For example, a platform used by a public buyer cannot oblige a company to purchase software that is not generally available for replies to tenders.

Ensuring that platforms in operation at the federal level are compliant with xVergabe and EU directives will require ongoing governance and oversight from the federal government. However, achieving system-wide oversight within a decentralised environment can be challenging. As demonstrated in Box 4.2, Italy’s national government has worked with dedicated regional bodies to promote the use of e-procurement and co-ordinate data gathering across each region.

Box 4.2. Regional coordination of e-procurement in Italy

The public procurement landscape in Italy is complex. One central purchasing body (CPB), Consip, is responsible for centralised procurement, e-procurement and the monitoring of approximately 36 000 contracting authorities. Only 13 ministries operate at the national level in Italy. At the same time, the local government is split into 20 regions, 110 provinces and 8 101 municipalities.

In order to support Consip in co-ordinating procurement activity across the country, Italy gave legal authority to a permanent group of public procurement aggregators in 2014. The 35 institutions given this authority included 21 regional CPBs, Consip itself and a select number of municipal cities. Italy then established a permanent technical working group in 2015 to allow representatives of the 35 institutions to co-ordinate their objectives. These objectives include:

assuring co-ordinated planning activities

strengthening capabilities around needs forecasting

gathering data on the needs expressed by public administrations

defining common methodologies and languages

constructing a common and complete database in order to provide information to policy makers

monitoring the effects of demand aggregation

defining and circulating best practices

promoting the use of e-procurement.

The Italian National Anti-Corruption Authority (ANAC) monitors the work of public procurement aggregators. The ANAC ensures that each CPB is qualified to conduct its work on the basis of a number of basic and additional requirements:

1. basic: appropriate organisational structure, skill levels of employees, training of employees and compliance with payment terms, among others;

2. additional: quality certifications, number of complaints received, use of electronic means of communications and use of social and environmental criteria, among others.

Source: Russo (2016), General Presentation on Consip, http://www.chilecompra.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Chile-12-Dec-consip-general-presentation-.ppt.

In order to manage the proliferation of e-procurement systems in Germany and make it easier for suppliers to identify and respond to tenders, mechanisms are needed to strengthen governance over the e-procurement activity of federal contracting authorities. Any governance structure must also consider how the implementation of xVergabe by suppliers of e-procurement systems to the federal government is monitored and encouraged. At the same time, the government should continue to co-ordinate with state-level partners to ensure that e-procurement platform providers across the country develop platforms that meet national standards.

4.2. Enabling the efficient collection and analysis of public procurement data to deliver insights

4.2.1. Authorities could build on xVergabe and increased automation throughout the system to gain a more holistic set of public procurement statistics for Germany

While implementing the EU directives on public procurement into German federal law, the German government sought to go beyond the implementation of electronic tender processes. In doing so, the government sought to establish measures that allowed for tender data to be collected centrally for further analysis. Subsequently, Germany passed the Ordinance on Public Procurement Statistics (VergStatVO) to mandate the collection of procurement-related data. The federal government’s intent to collect procurement data is in line with international good practices. For example, a key benefit of e-procurement for many countries is that electronic systems facilitate the collection and use of procurement-related data. According to a Deloitte survey of private sector chief procurement officers (CPOs), 65% of CPOs think that analytics is the technology area that will have the largest impact on procurement in the next two years (Deloitte UK, 2017[19]).

The VergStatVO, enacted in April 2016, conveys upon all contracting authorities the obligation to submit information on their procurement activity. All tenders over EUR 25 000 conducted by contracting authorities at the federal, state and local level are compelled to submit a comprehensive suite of information related to the tender (such as the tender value, the type of procedure used, evaluation criteria and a range of information related to the contracting authority and the economic operator).

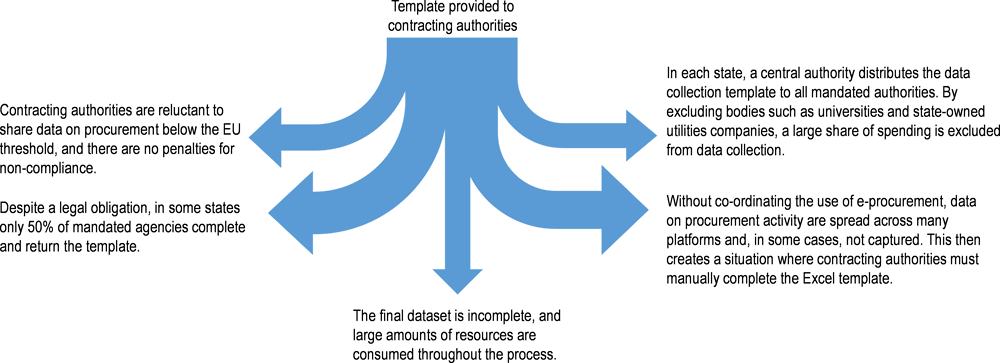

At the same time, the German federal government has acknowledged that there is currently no mechanism to automatically collect and transmit the data mandated by the VergStatVO. Because of this, the VergStatVO grants a transition period during which time contracting authorities can submit data manually until the required infrastructure is in place. A template in Excel format is sent to contracting authorities on an annual basis to facilitate the collection of data. This process has led to errors. Manual data entry also adds to the administrative burden on contracting authorities. It has been a significant undertaking for entities at all levels of government to document, collect, analyse, synthesise and re-format data from the hundreds of thousands of procurement activities that are conducted each year. Despite the legal obligation to comply, rates of return from contracting authorities at all levels of government have been reportedly low. For example, an OECD interview with one German state indicated they had a return rate of 50%. Some of the challenges experienced during the data collection process are outlined in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2. Distribution of all possible procurement data during federal data collection process

Source: Authors’ illustration.

Given the importance of collecting procurement data and the amount of time and effort expended by contracting authorities to comply with the new reporting requirements, it is critical to ensure that more consideration is given to how data from multiple platforms are collected, stored and used. The xVergabe project has succeeded in finding a way for tender information to be transferred between platforms. For now, the project has not been designed to include procedures for the collection and centralisation of data on the procurement activity that takes place across different platforms. So while information about a single tender should be shared across multiple platforms, there has been no focus on how these platforms could collect information on multiple tenders so that the information might be analysed. By more effectively using xVergabe to ensure that e-procurement platforms can help to automate the data gathering process, the quality and quantity of data collected would be greatly improved. This would also help to reduce the current administrative burden on contracting authorities.

The current data collection challenges undermine Germany’s attempts to analyse procurement activity to measure the economic impacts of procurement, identify inefficiencies and set and measure progress against targets. The collection of procurement data can support policy makers in developing insights into how procurement is contributing to governmental goals like economic performance and productivity. Data can also serve the broader purposes of promoting a more open and transparent government, building public trust and serving the needs of a broad range of stakeholders. However, there are limitations to the effectiveness of data when working from an incomplete dataset. Some of these limitations are particularly pronounced in the case of Germany, given the effort and resources required to undertake the current manual collection process. This process can be improved by utilising existing e-procurement systems to collect data.

4.2.2. Establishing a data management strategy will clarify the right format, location and use for procurement data

The current process for data collection in Germany is not only burdensome for contracting authorities, it also requires additional work prior to analysis. Data collected through spreadsheets that contain a number of open text fields may require a degree of cleaning before results can be pooled together and analysed. Furthermore, it may not be straightforward to use the results from these data to identify trends and issues.

In the United States, the absence of a broadly used e-procurement system for the federal government created challenges for data collection. In response, the government developed an electronic solution to collect procurement data in a fragmented e-procurement environment through a format that quickly and easily enabled procurement data to be used to gain insights (see Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Electronic data collection by the US federal government

In the United States, a number of electronic procurement tools have been made available for contracting authorities at the federal level. If contracting authorities choose not use these centralised tools, they must submit federal spending data to the Federal Procurement Data System. Federal contracts over a value of USD 3 500 (as well as contracts that incur subsequent modifications) must also be submitted to the Federal Procurement Data System.

The federal government uses the data kept in this system to measure and assess: 1) the impact of federal procurement on the nation’s economy; 2) how awards are made to businesses in various socio-economic categories; 3) to understand the impact of full and open competition on the acquisition process; and 4) to address changes to procurement policy. These measurements and assessments are made possible through the use of unique identifiers. These identifiers connect the collected information to other systems that hold information on suppliers. Each supplier is given a code that allows authorities to reference the number of transactions with suppliers against other information like company size and tax information.

The System of Award Management (SAM) is a separate database that suppliers must register with before being able to bid for (and provide) services to the federal government. SAM allows government agencies and contractors to search for companies based on ability, size, location, experience and ownership. When connected to information in the Federal Procurement Data System, the government can monitor the success in bidding for public tenders of: SMEs; businesses owned by women, veterans and minorities; and businesses located in economically challenged areas.

Contracts can also be aligned to special spending categories in order to monitor spending at a more granular level. For example, the government has established unique codes for natural disasters. Associated contracts are aligned to the code for natural disasters in order to monitor spending on clean-up efforts.

Source: General Services Administration (n.d.), Federal Procurement Data System, https://www.fpds.gov/fpdsng_cms/index.php/en/reports.html.

In Germany, the xVergabe project has established standards for the format of data so that tender information can be transferred across platforms. However, while these standards focus on how data packages can be transferred, there is no stipulation of what format tender documents must take. Countries increasingly implement data management strategies that align with open data standards.

The use of open data standards can bring about many benefits, one of which is the use of procurement data to increase accountability and enable analysis (see Box 4.4). In many of the systems currently used across Germany, the process for achieving transparency and accountability in procurement involves public disclosure of a large number of documents in formats like scanned PDFs. This means that control entities and other stakeholders (e.g. auditors or the public) must invest considerable effort and resources to identify trends or unique cases worthy of investigation. For example, collusive behaviour is a significant inhibitor to competition. Therefore, providing competition authorities with procurement data in a usable format will enable them to identify and prevent this behaviour. Thus, ensuring accountability for government spending requires the public disclosure of high-quality data in a format that allows analysts to detect trends and exceptions.

Box 4.4. The Open Government Data movement encourages the effective capture and use of procurement data

According to the OECD, Open Government Data “is a philosophy – and increasingly a set of policies – that promotes transparency, accountability and value creation by making government data available to all” (OECD, 2018[20]). The open data approach acknowledges the importance of harmonised processes for capturing data, including procurement data. This approach can be achieved through a highly efficient tender process that is designed with procurement officials and businesses in mind. Due to the benefits of transparency, accountability and value creation, open data is increasingly seen as a key public good.

Implementing open data in relation to procurement can be challenging given that data relating to contracts and tenders are often incomplete. Frequently, these data are incomplete because they do not cover all procurement stages (including payment and delivery), or because certain processes have been left undocumented or captured in different formats. Data can also be fragmented due to different collection methods in numerous government departments. Finally, data can be left largely unused.

The Open Government Data movement regards the availability of high-quality data together with the application of big data analytics to strengthen their interpretation as indispensable conditions to supporting a more efficient use of public resources and more accountable governments. The application of big data analytics techniques to public procurement data can provide a number of opportunities for sounder policy making, stronger oversight of governments’ activities and the assessment of governments’ performance. The transition from open procurement information (which can include unreadable and inflexible formats such as PDFs) to open contracting data supports these aims. This is because open contracting data more easily enables data to be captured and used for monitoring and analytics purposes.

Some of the advantages of Open Government Data include:

Assessing organisational behaviour: Linking open data on multiple transactions over time (such as data on individual tenders, organisations, local governments’ programmes and government programmes) can help officials track patterns in organisational behaviours, decisions, investments and more.

Embedding new performance indicators in policy making: Linking public procurement data with other administrative datasets, such as national company registries, can provide new sources of evidence and statistics to measure government performance.

Using market analytics to detect collusive behaviours: Governments increasingly use public procurement data in an innovative way to detect collusion among suppliers, and to punish anti-competitive behaviour (Cingolani et al., 2016[21]). Signs of collusive behaviour can be detected by analysing price-related variables like: bid distribution characteristics; specific bidding patterns like bid rotation or bid suppression; and market structure-related variables like market concentration.

Holding governments accountable and safeguarding public spending: Recent developments show that many open data portals are being created by civil society organisations with a view to holding governments accountable for their efficiency and transparency in public spending.

Delivering benefits to various stakeholder groups: Several types of users can benefit from public procurement information: citizens can check how projects are being managed and funded in their area of their interest; investigative journalists can gain access to information on public procurement cases; potential suppliers can explore new public procurement markets; and public oversight bodies can use the data to investigate specific cases or identify general trends.

Source: (OECD, 2016[22]), Compendium of good practices on the use of open data for Anti-corruption: Towards data-driven public sector integrity and civic auditing, https://www.oecd.org/gov/digital-government/g20-oecd-compendium.pdf.

While the use of procurement data to achieve strategic and policy objectives may be well understood, there are challenges to the centralisation and analysis of data in Germany. Implementing initiatives such as open data contracting and data gathering at the federal level may be possible in the short to medium term. However, collecting and concentrating a broad range of data from across different states in Germany will be more challenging. The reason for this is that the autonomy of the different Länder also extends to the provision of data to the federal government on state-level activity.

Acknowledging that the use of data to identify trends and challenges is a worthwhile effort, Germany could consider alternative approaches to allow data collection to occur within a decentralised environment. As described in Box 4.5, in 2017, the UK developed a tool to analyse procurement data in order to flag potential indicators of collusive behaviour. Subsequently, however, the UK had to develop an alternative approach because of local authorities’ concerns about sharing commercially sensitive data outside of their IT environments. During this phase of the project, authorities had to develop a decentralised approach to data analysis, resulting in the tool being distributed for use by contracting authorities themselves.

Box 4.5. Using procurement data to screen for anti-competitive behaviour in the UK

As a part of the implementation of the UK’s Anti-Corruption Strategy, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) initiated a project to design and test a tool that could analyse procurement data to identify anti-competitive behaviour. At the time, the UK was hampered by a lack of a central repository for procurement data. This lack of central repository restricted the country’s ability to monitor collusive behaviour over time and track market trends. Discussions with local authorities also unearthed concerns about sharing commercially sensitive procurement data outside of their IT environments.

In response to these limitations, the CMA developed a tool for local authorities that allowed them to analyse their own data. The tool analyses information from tenders (including the underlying meta data from tender documents) to identify patterns related to a number of indicators:

number and pattern of bidders (i.e. a low numbers of bidders)

suspicious pricing patterns (winning price as an outlier, similar pricing across bids)

low endeavour submissions (documents developed by the same author, similar text across bids or small amounts of time spent preparing bidding documents)

combinations of the above factors.

Weighting can be applied to each of the above factors depending on their strength as an indicator within the relevant market, resulting in an overall score. The tool relies on data documents in Microsoft Word or readable PDF files (not including scanned PDFs) to conduct its analysis.

This distributed method for data collection has limitations. The method is dependent on local authorities conducting their own analyses using the tool and flagging issues for the CMA when relevant. By building a network of users of the tool across different regions, CMA hopes that users can share lessons and trends on identification of collusive behaviour.

Source: Competition and Markets Authority (2017), CMA launches digital tool to fight bid-rigging, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-launches-digital-tool-to-fight-bid-rigging.

Where procurement data is captured in the right format, analysis can unlock valuable and insightful findings. Doing so within a federal system requires careful consideration of data. Authorities should differentiate between data that should be concentrated and data that should remain de-concentrated at the sub-national level, yet still put to use by the authorities, when appropriate. The federal government could therefore establish a data management strategy that identifies how data collected by platforms across Germany can be harvested to enable valuable and insightful analysis. At the same time, the federal government should consider providing tools that enable decentralised analysis when necessary.

4.3. Expanding the scope and reach of digitalisation

4.3.1. Co-ordinating e-procurement development with broader e‑government reforms can increase the benefits of digitalisation

OECD countries have identified additional benefits that can be achieved from expanding the scope of digitalisation in procurement to incorporate pre- and post-tender activities. These benefits include increasing efficiency and standardisation across the procurement cycle, and more closely managing government spending and contract compliance. Furthermore, by integrating procurement platforms with finance systems and other federal databases, the federal government can gain broad visibility of the use of federal funds. In turn, this visibility will better enable the monitoring of economic activity.

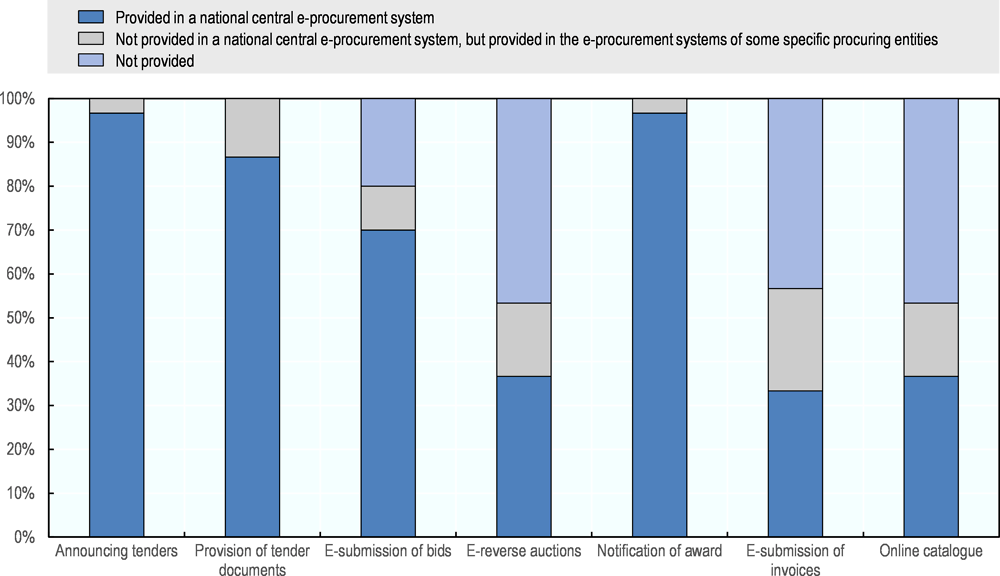

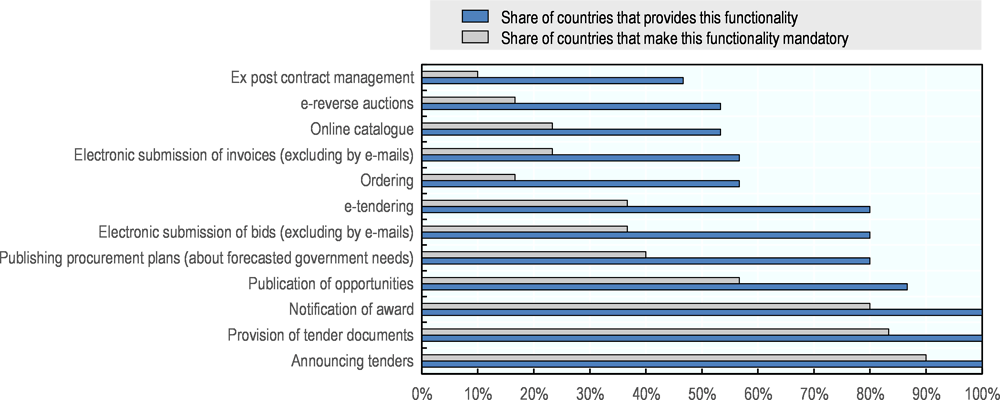

OECD member countries are slowly developing their e-procurement systems to cover more transactional functionalities beyond the core steps of the procurement process (i.e. announcing tenders, providing tender documents and posting contract award notices) (OECD, 2017[8]). As demonstrated in Figure 4.3, survey data shows that all OECD countries have the ability to use electronic platforms for the publication phases of the procurement cycle, namely publishing tenders and award notices. 80% of OECD countries have begun the transition to more transactional systems by enabling the electronic submission of bids. However, most countries (including Germany) do not have national systems that are able to manage post-tender activities such as e-invoicing and reverse auctions.

Figure 4.3. Use of electronic processes for managing procurement cycles in OECD countries

Source: OECD (2016), Survey on Public Procurement.

Procurement data can be used to shape procurement policy, but it can also be combined with other federal information sources to achieve government objectives. The digitalisation of processes across different parts of government presents opportunities to link procurement data with information from other federal systems.

The European Commission recommends that countries link databases across government so that comprehensive information on companies can be made available (European Commission, n.d.[23]). Linking databases can generate efficiencies for both the government and the private sector. For example, as shown in Box 4.6, information on companies in New Zealand is linked through the New Zealand Business Number, an initiative that seeks to streamline interactions between government and businesses.

Box 4.6. Improving interactions between government and businesses in New Zealand

The New Zealand Business Number (NZBN) is a single, unique identifier that helps businesses maintain a singular version of the information that identifies their companies in New Zealand and globally. Businesses of any size can apply for a number.

Each business’ core information (referred to as primary business data) is held securely online in the NZBN Register. This information includes a business’ trading name, its address and other contact details. Businesses can also opt to include additional information such as invoicing details.

The NZBN is intended to ease interactions both between businesses and government, and between businesses. NZBN details can be updated with one government agency as changes are made to their information in the NZBN Registry avoid having to speak to multiple departments to inform them of these changes. Furthermore, other businesses and government agencies can access information in the NZBN Registry to save time during invoicing and procurement processes. Provision of a business’ NBZN in a government tender process eliminates the need to continue to provide generic information.

A number of success stories have been collected by the NZBN project team to demonstrate the benefits that have been provided to government and businesses by the introduction of the NZBN, such as:

A business providing accounting software has highlighted how the NZB was used to ensure that information about other businesses, both customers and suppliers, was accurate.

A bank described how pulling information from the NZBN Register allowed them to gather up-to-date customer data in real time.

The Ministry of Social Development uses the NZBNs of social service providers to prevent duplication and inconsistent information across the sector.

Source: New Zealand Business Number (n.d.), New Zealand Business Number, https://www.nzbn.govt.nz.

Germany’s anti-corruption framework was updated in 2017 with a law that introduced a competition register (Wettbewerbsregister). The register enables procurers to digitally verify whether potential suppliers have committed a criminal offence. Furthermore, the register permits public authorities to access company information. Once the procurement process is digitalised, information from the competition register can be incorporated directly into the e-procurement process.

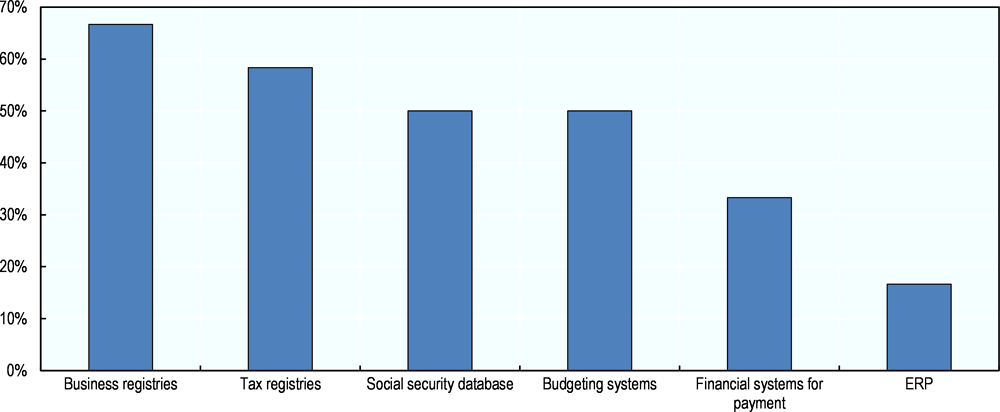

Connecting information across systems ensures that companies listed in the register are prohibited from registering for and participating in tenders. If company information in the register includes information such as company size, it will enable enhanced reporting of SME participation and success in public tenders. At present, OECD countries connect their procurement systems with several other types of national government information systems in order to better monitor procurement and collect more holistic data. The central systems most commonly integrated with procurement systems in OECD countries are demonstrated in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4. Most popular central government information systems integrated with procurement systems in OECD countries

Source: OECD (2016), Survey on Public Procurement.

As described in Box 4.7, countries such as Colombia have benefited from developing a connection between their national e-procurement and financial management systems.

Box 4.7. Horizontal system integration with the national finance system in Colombia

In 2015, Colombia upgraded its e-procurement platform. During the second phase of this upgrade, officials expanded the Electronic System for Public Procurement (Sistema Electrónico para la Contratación Pública, SECOP II) and integrated it with the Integrated System of Financial Information (Sistema Integrado de Información Financiera, SIIF). This direct connection between the e-procurement system and the financial reporting system greatly increased data accuracy and transparency on spending by procurement entities.

Integrating procurement and budget data eliminated risks of corruption, including the separation of financial duties, examples of false accounting and cost misallocation, and late payment of invoices. In Colombia, some government entities are required to use the system, and some are merely encouraged to do so.

To attract government bodies (such as state-owned entities) that are not mandated by law to use the system, Colombia’s public procurement authority Colombia Compra Eficiente has developed a series of key performance indicators that measure the performance of the national procurement system in a number of categories. Each measure uses a baseline result from the preceding year to develop targets in the following areas:

value for money: including metrics on the time required for procurement processes and savings achieved through procurement

integrity and transparency in competition: including measures on the number of contracts awarded to new suppliers and the percentage of contracts awarded through non-competitive processes

accountability: including measures of public entities using SECOP and the percentage of awarded contracts published on SECOP

risk management: features one single measure of the percentage of contracts with modifications of time or value.

Source: (OECD, 2016[24]), Towards Efficient Public Procurement in Colombia: Making the Difference, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252103-en.

Procurement information can help provide a more holistic picture of economic trends and the business environment in a country if it is integrated with information that is collected by other parts of the federal government.

4.3.2. The KdB provides a valuable service, but it is used only for a small proportion of government spending

The scope of centralised post-tender management at the federal level in Germany at present is limited to the KdB. The KdB is an e-catalogue that allows federal contracting authorities to purchase common goods and services from framework agreements. All CPBs at the federal level (except the ZV-BMEL) post framework agreements to the KdB so that eligible contracting authorities can purchase from them.

At present, around 460 contracts are available through the KdB. Approximately 380 contracting authorities and other public institutions use these contracts. However, as illustrated in Figure 4.5, this figure only represents a proportion of spending both at the federal level and across Germany.

Figure 4.5. Illustrative proportion of government spending managed through federal framework agreements

Note: the size of circles is not representative of the amount of spending.

Source: Authors’ illustration.

With the exception of procurement under federal framework agreements, contracting authorities at all levels in Germany have the autonomy to manage post-tender activity (i.e. the execution of a contract, ordering, ongoing contract management, and invoicing) as they see fit. Authorities in this position often use manual and paper-based processes. Stakeholders interviewed by the OECD stated that it is likely that a large proportion of purchases under federal framework agreements are not conducted through the KdB. In these cases, federal contracting authorities may be purchasing from framework agreements, but doing so by dealing directly with suppliers.

The KdB provides access to framework agreements that cover a range of goods and services for which there is a common need across government. Yet, as discussed in Chapter 3, the volume of transactions that go through the KdB indicates that these framework agreements do not represent a large proportion of federal spending, even in common product categories. Even with this relatively low coverage, there are concerns that, in its current form, the KdB platform will not be able to sustain a substantial increase in the number of users or framework agreements. The current transaction volumes are causing system performance issues, and each framework agreement that is added to the system further degrades its performance. Therefore, future projects to enhance e-procurement in Germany could seek to upgrade the KdB so that it is able to cope with the expected expansion of framework agreements. Indeed, this agenda is included in the aims of the IT project ERP/KdB 4.0, which outlines the overall implementation of the reform of Germany’s e-procurement system.

The KdB system acts as a portal for contracting authorities to make purchases from catalogues established by framework agreements. The administrative office of the KdB resides in the Federal Procurement Office of the Ministry of the Interior (BeschA). This office is responsible for managing the system and ensuring that the system’s workflows for purchasing goods and services are structured in accordance with contracting authority approval procedures. The KdB uses electronic signatures to approve contracts, generate invoices automatically and send them to contracting authorities. There is no requirement for interoperability between KdB and the finance systems of contracting authorities for purchases to be made. The KdB undoubtedly adds value to the German procurement system by facilitating the efficient use of framework agreements by federal contracting authorities. However, greater value can be added by expanding the system’s usage and reach.

4.3.3. Digitalising post-tender processes is a necessary next step for enhancing the management of government spending

The European Commission has taken steps to increase the use of electronic methods beyond the traditional tender cycle by introducing a directive on electronic invoicing. Businesses across Europe currently experience inefficiencies in working with different invoicing systems and processes in different countries. Often, these companies must also work with different invoicing systems and processes in the same EU member state. Invoices that vary in format and content cause unnecessary complexity and high costs for businesses and public entities. According to the 2014 European Commission directive, all federal contracting authorities must accept electronic invoices that comply with the European norm by November 2018 (E-Rechnungsgesetz 2018). Smaller contracting authorities have an additional 12 months to comply with the directive. However, nationally specific rules that do not contravene the directive will remain valid. The directive is not intended to result in a European e-invoicing infrastructure. Instead, the supplier market will be responsible for developing compliant solutions (European Commission, 2018[25]).

The implication of the EU directive for contracting authorities is that they must be able to receive and process electronic invoices that comply with the European standard on electronic invoicing. There are a number of ways in which this can be achieved technologically. The most efficient process would involve the automatic transmission of an invoice from a supplier’s system to the system of a contracting authority. This would require contracting authorities to employ an electronic financial management or payment system. Based on findings from OECD interviews, this technology is not commonplace among contracting authorities in Germany, particularly at the state-level. However, contracting authorities that implement these systems do stand to reap considerable benefits, as described in Box 4.8.

Box 4.8. Using systems to enhance financial management at the Federal Ministry of Defence

According to OECD interviews with stakeholders, German contracting authorities that have implemented electronic systems to monitor and manage finances and spending areas have realised substantial benefits from the investment.

Germany’s Federal Ministry of Defence (BMVg) analysed organisation-wide spending, allowing the BMVg to gather 90 contracts in one particular category into one framework agreement. The added visibility that the e-procurement system introduced has enabled BMVg to form a true picture of spending across the organisation. All new contracts and procurement activity are now conducted through the system. In turn, this better spending picture has enabled a greater degree of control over spending, better management of suppliers and increased efficiency in contract management processes.

Source: Responses from German federal and state-level institutions to an OECD questionnaire and interviews.

Less efficient alternatives exist that allow contracting authorities to comply with the EU invoicing directive. For example, a contracting authority will still comply with the directive if it accepts supplier invoices that are in an electronic data file, submitted through a portal, or from data supplied in a machine-generated PDF (European Multi-Stakeholder Forum on e-Invoicing, 2016[12]).

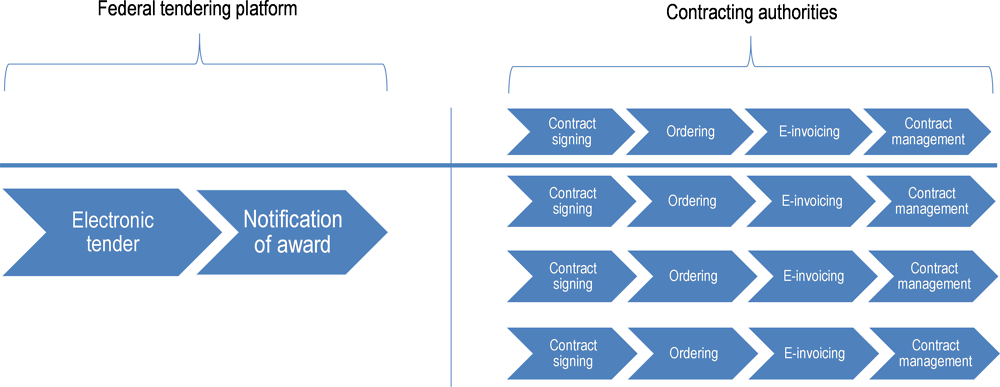

As government processes increasingly transition towards digitalisation, the electronic management of finances across different levels of government – including managing spending with third parties – should be seen as an area of priority for investment. Vertical integration of systems (i.e. integration of the central tendering platform with financial systems or contract management systems of contracting authorities) will result in a fully integrated, end-to-end management of spending. Gaining full visibility of spending and moving away from paper-based transactions will result in efficiency benefits for contracting authorities and the government as a whole. Additional benefits that should occur from a more integrated and end-to-end e-procurement system include:

the ability to collect data on government spending to inform economic and procurement policy

closer monitoring of supplier compliance with government contracts

the establishment of centralised tools such as contract management modules to build contract management capability and increase efficiency in the post-procurement phase of the cycle.

As demonstrated in Figure 4.6, to enable the seamless connection of processes and data across different systems throughout the procurement cycle, each procurement step must be carried out digitally.

Figure 4.6. Illustration of the separation between procurement steps covered by federal systems and contracting authority processes

Source: Author’s illustration based on responses from German federal and state-level institutions to an OECD questionnaire and interviews.

As shown above, the digitalisation of the contract signing and approval process represents a key step in the digitalisation of the procurement cycle. In Germany, the xVergabe standard stipulates the features of the authorisation technology that platforms are required to use. Despite this guidance, many contracting authorities remain reluctant to embrace the digitalisation of this step. This reluctance may stem from concerns related to the privacy and security of digital processes. For example, some public buyers and suppliers in Germany consider electronic signatures to be complicated, error prone and expensive to implement. In a survey of SMEs across the EU, about 7% of SMEs cited the lack of a domestic electronic authentication infrastructure to accept e-signatures as the most crucial problem in connection with the introduction of e-procurement solutions. Overall in this survey, the lack of a domestic authentication infrastructure to accept e-signatures was mentioned the fifth most frequently (Vincze et al., 2010[26]).

According to EU directives, member states may require electronic tenders to be accompanied by an advanced electronic signature. However, EU regulations have clarified that e-signatures are no longer considered a means of authentication, but merely a tool for signing documents.

Many countries have effectively implemented other forms of authentication. Digital submission and acceptance of offers is reliant on electronic authentication and certification technologies. However, there have been recurring challenges with implementation among EU member states. These challenges are due the fact that:

certification can act as a barrier to cross-border trade, as certification for out-of-country suppliers is too difficult or costly

some suppliers do not have the technological means or the human capabilities to use authentication software

some member states do not have the appropriate software to support implementation.

Therefore, federal authorities must consider these factors when selecting an appropriate authentication solution. In addition, federal authorities should act to alleviate concerns about digital authentication among users. These efforts should be supported by the provision of training for contracting authorities and suppliers on how to use authentication tools and how to avoid common pitfalls. Austria, for example, relies on the use of electronic authentication, and has found a technical process that meets its needs (see Box 4.9).

Box 4.9. Implementation of electronic authentication at Bundesbeschaffung GmbH (BBG) in Austria

A key tenet of the Austrian e-procurement system is the ability of users to submit offers (and contracting authorities to accept offers) digitally. Austrian procurement law provides the electronically qualified signature and gives it equal importance to a manual signature.

In order to be able to sign an electronic document in a legally binding manner (e.g. an offer), the signatory requires a qualified certificate. To obtain a certificate, suppliers must meet several formal requirements in Austria. To ensure the security of the certificate, the agency providing certification contacts the supplier to provide them with secret information that is required to activate their signature.

To sign a document, the signatory requires a mobile phone or a signature card and appropriate software, which may be obtained online. The process is similar to the mobile transaction authentication number (TAN) procedure, which is widely used in e-banking.

Source: Information provided by BBG.

Germany can further unlock the benefits of digitalisation by considering how e-procurement reform will fit with a broader e-government agenda. This may involve embracing digital processes for transactions outside of the tender process. Such steps would enable greater end-to-end visibility (i.e., visibility of the entire procurement cycle) and management of public spending, as already planned for in the ERP/KDB 4.0 project. Expanding digital processes for procurement will make the use of taxpayer funds more visible.

4.4. Overcoming barriers to the use of e-procurement

4.4.1. Germany’s efforts to reform the federal e-procurement system must take into account the causes of low system use by contracting authorities

At present, Germany is undertaking a project to harmonise its e-procurement environment into a single platform. The project, which is due to run from spring 2018 until spring 2021, will establish a single platform onto which federal contracting authorities will be mandated to post their tender opportunities. The project will also go beyond the traditional steps of the procurement process by incorporating the current KdB functionality and by providing electronic invoicing. The integration of e-invoicing into the system will allow data to be collected on order volume. The platform will also be available for use by state and municipal contracting authorities. Furthermore, authorities are planning to enhance tender functionalities to fully manage communication between contracting authorities and suppliers during the tender process. These efforts will also enable the timestamping of tender documents so that compliance can be more accurately audited.

If successful, this project should resolve several of the issues that have been identified in this chapter. But beyond the difficulties that are typically associated with this type of project, such as selecting the right solution and successfully rolling out the technology within time and cost constraints, the low use of e-procurement by contracting authorities and suppliers at present will make the implementation of the platform especially challenging.

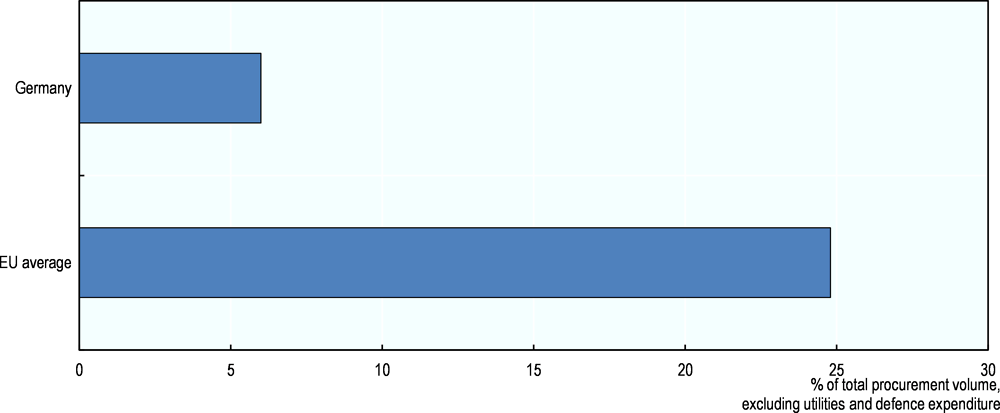

The challenges Germany has faced in adopting e-procurement are evidenced by the country’s performance in different areas when compared to other EU member states. Currently, it is reasonable to say that Germany still lags behind other EU member states in the use of information and communication technologies for public procurement. Considering, for example, online publication of tenders above the thresholds, in 2015, Germany was the country with the lowest publication rate in the EU, with only 6% of all tenders publicly advertised on the European tender site, European Tenders Daily (TED) (see Figure 4.7). This figure is significantly lower than the EU average of 24.8% (European Commission, 2016[16]). The value of public tenders listed on TED represents just 1.1% of Germany’s GDP, or 6.4% of public expenditure (excluding utilities). The European average is 3.2% of GDP, or 19.1% of public spending, meaning that Germany is only providing pan-European visibility of a third of the number of tender opportunities compared to its European counterparts. Although the low publication rate does not automatically imply a low use of e-procurement, it shows there is room for improvement to align Germany with the EU in specific indicators.

Figure 4.7. Publication rates on TED: Germany vs. the EU average

Source: (European Commission, 2016[16]), Public procurement – Study on administrative capacity in the EU: Germany Country Profile, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/how/improving-investment/public-procurement/study/country_profile/de.pdf.

There are mitigating factors that might explain this low number. In EU member states where public procurement is largely decentralised to states and municipalities (as in Germany), tenders tend to be smaller. In addition, in these countries, many tenders do not exceed the EU thresholds above which publication in TED is obligatory (Vincze et al., 2010[26]).

Non-residential investment has declined in Germany since the financial crisis, despite strong a macroeconomic and financial recovery. At present, Germany also has a declining amount of non-residential (i.e. foreign) capital growth, particularly in IT software and infrastructure, which also correlates to a lack of productivity growth. E-procurement could attract non-residential investment and capital growth, but Germany will need to make better use of the electronic procurement system to achieve these results. The implications of failing to attract external businesses to invest in Germany through the use of e-procurement could be significant. There are also concerns that the comparatively low level of investment in infrastructure has resulted in a lack of expertise in delivering complex procurements at the local level, which is where the majority of procurement spend is located (Fuentes Hutfilter et al., 2016[27]).

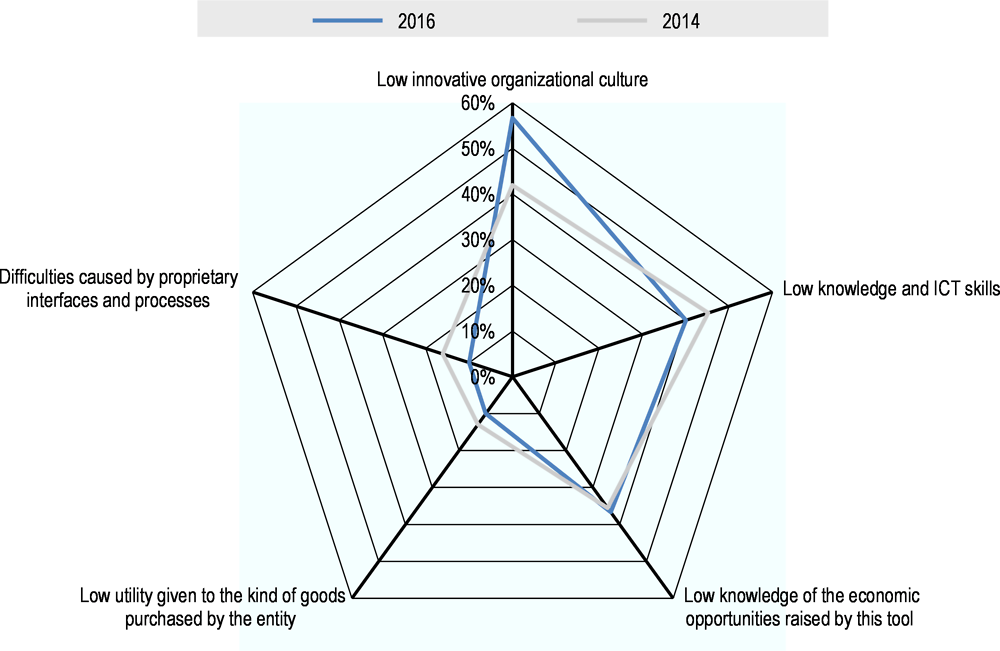

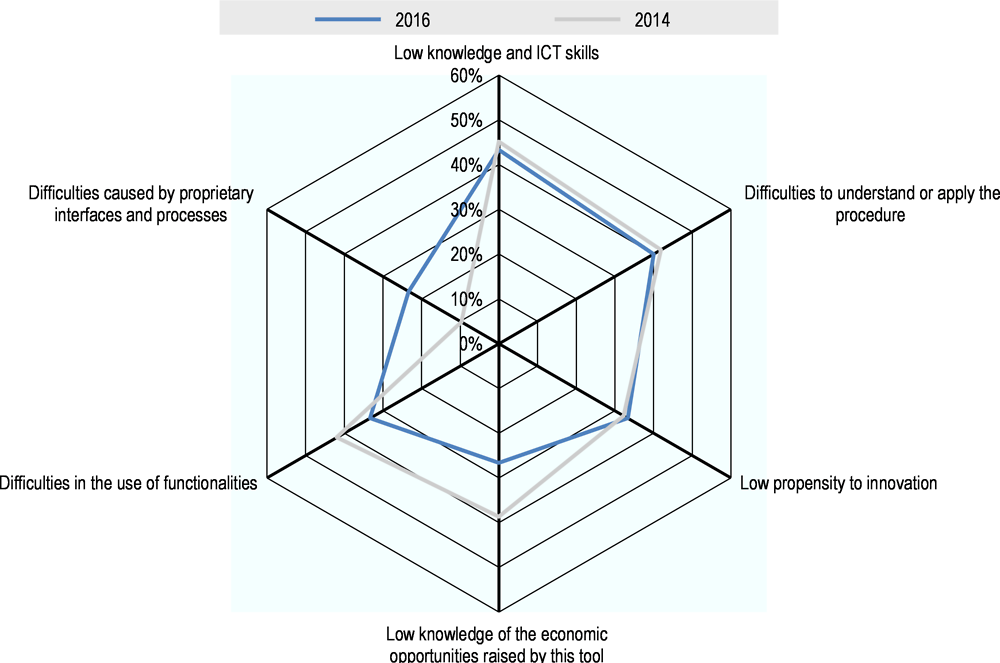

As regularly, in 2016, the OECD undertook a survey on public procurement. The survey found that contracting authorities in OECD countries using e-procurement systems faced many challenges. These challenges included: 1) an organisational culture that was not as innovative as it could be (57%), 2) limited ICT knowledge and skills (40%) and 3) limited familiarity with the economic opportunities that e-procurement systems can offer (37%) (see Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8. Challenges facing contracting authorities using e-procurement in OECD countries

Source: OECD (2016), Survey on Public Procurement.

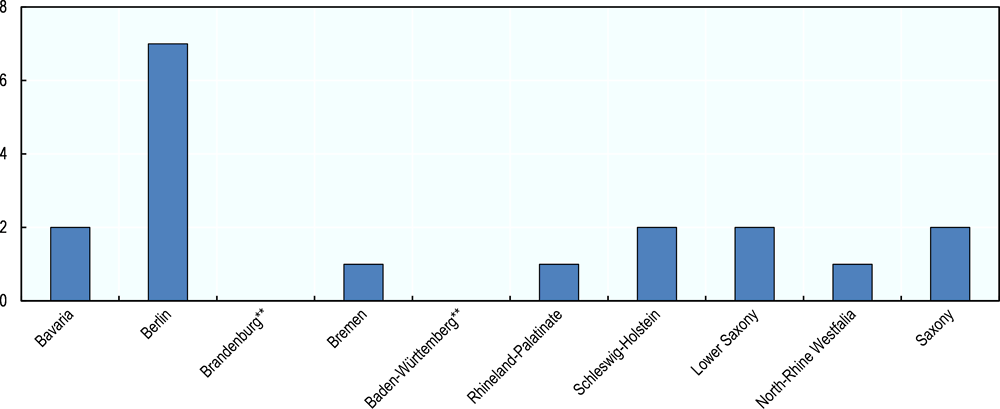

Data collected on the use of e-procurement by contracting authorities in Germany confirms that public buyers experience many of these challenges. As demonstrated in Figure 4.9, familiarity with (and use of) e-procurement in Germany decreases outside of the core stages of the tender process.

Figure 4.9. Use of e-procurement technologies by public buyers in Germany

Source: (Schaupp, Eßig and von Deimling, 2017[28]), Anwendung von Werkzeugen der innovativen öffentlichen Beschaffung in der Praxis: Eine Analyse der TED-Datenbank.

The lower use of e-procurement outside the core stages of the tender process indicates that many contracting authorities may not be complying with the obligation to run tenders electronically. If contracting authorities do not use electronic procurement for the parts of the procurement process that they are mandated to, Germany will fail to comply with EU law on electronic posting of tenders over the EU threshold. In addition, failing to use mandated e-procurement could produce high-levels of inefficiency in the procurement process, an inability to encourage suppliers to transition to digitalisation and lower rates of competition.

4.4.2. Suppliers must be given an incentive to engage in the rollout of e‑procurement – as they stand to benefit too

As discussed above, the transition to e-procurement presents the potential to achieve many benefits, including increasing the efficiency of the procurement process for buyers and suppliers. However, businesses in Germany demonstrate a lower level of maturity in the use of e-procurement when compared with other OECD countries. Therefore, efforts to achieve legislative deadlines and transition to digital processes must consider the business community. If businesses are not sufficiently prepared or trained for the transition, there will be a decrease in efficiency for suppliers – or even a reduction in competition for public tenders.

German businesses are losing the opportunity to increase their productivity through the use of e-procurement. The figure below demonstrates that German businesses do not perform well when compared to other European businesses in the use of electronic procurement (Fuentes Hutfilter et al., 2016[27]). As demonstrated in Figure 4.10, less than 20% of German businesses use electronic platforms to access tender documents and specifications, while less than 10% conduct e-tendering. Research has shown that the use of e-procurement in the manufacturing sector can lift firm productivity by 2.5% (Clayton, Criscuolo and Goodridge, 2004[29]). Therefore, efforts to guide contracting authorities towards digitalisation must also consider the capabilities of the private sector in order to achieve the resulting widespread economic benefits.

Figure 4.10. Use of e-procurement by businesses in OECD countries

Note: Missing OECD member countries are not included in the OECD average.

Source: (OECD, 2013[30]), Government at a Glance 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-en.

The investment required to ensure that businesses are prepared for the transition to e-procurement should not be underestimated. In the state of Lower Saxony for example, an estimated 90% of the e-procurement budget is used to train businesses on how to use the system and to widely promote its use. Indeed, interviews with business representatives indicated that, although the use of e-invoicing and e-submission will soon be mandatory, German businesses are not ready for their implementation. One reason businesses are not ready for implementation is that there are still e-commerce interoperability issues that must be solved.

According to the OECD survey on public procurement, the barriers for businesses in using e-procurement differ from those faced by contracting authorities. As shown in Figure 4.11, barriers for businesses are more diverse and include limitations in their knowledge and skills in using ICT, difficulties in interacting with the system and problems with understanding or applying the necessary procedures.

Figure 4.11. Challenges facing suppliers using e-procurement in OECD countries

Source: OECD (2014, 2016), Survey on Public Procurement.

Germany needs to send a strong message to motivate suppliers to adopt e-procurement. The country should also give suppliers clear incentives to engage. The federal government has already conducted research into the benefits businesses could reap by engaging in an electronic as opposed to paper-based procurement procedure. The findings indicate efficiency savings for businesses. These findings should be shared with suppliers in order to promote the transition.

At the same time, stakeholders that are supportive of e-procurement feel that the role of business in supporting decision making around e-procurement is diminishing. Committees involving the private sector once dominated decision making on German procurement. Now, only the committee responsible for works is functioning, with much of the decision-making power reverting to the government. The business community also feels that consultation with the private sector on recent legal changes related to e-procurement did not allow sufficient time to enable thorough and comprehensive feedback. To avoid significant challenges during implementation, future changes to the e-procurement system in Germany must ensure that concerns and challenges of the private sector are taken into account.

E-procurement can play a significant role in public procurement reform, but it will not necessarily remedy poor procurement practices or solve underlying problems in public procurement operations. Benefits yielded by e-procurement are usually a result of stronger management and co-ordination facilitated by technology, rather than a result of the technology itself (Asian Development Bank, 2013[31]). These facts about the key role human management and operations play in e-procurement highlight the need for a project that takes a comprehensive approach to implementation, and identifies ways to overcome the current barriers to the use of e-procurement.

4.4.3. Efforts to upgrade the e-procurement system must be part of a comprehensive programme to effectively bring about change

Technological change must be part of a comprehensive strategy that removes barriers to the effective use of e-procurement. According to a study carried out by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development on implementing diverse e-procurement solutions, these five pillars are the essential elements of an e-procurement strategy (EBRD; UNCITRAL, 2015[14]):

1. Government and institutional leadership: Government sets the vision for what is to be achieved; the operational implementation of e-procurement must then be owned or co-ordinated by one agency to achieve commonality of standards and approaches.

2. Management, legislation, regulation and policy: E-procurement is a business rather than a technological system, and it requires strong legislative and management frameworks to be successful. Changes to the e-procurement system will result in amendments to the processes and policies surrounding government procurement, including revised audit and compliance regimes and improved management information on all aspects of procurement. These changes must be understood and prepared for in advance of any modifications to the system.

3. Private sector activation: As mentioned in prior, an e-procurement strategy needs to be mindful of the private sector. Government should consult with the private sector to make the e-procurement strategy effective in terms of both supply and demand. Any engagement strategy should consider communication with businesses as a means to building the case for system changes and preparing users for changes in functionality.

4. Infrastructure and web services: The success of a government e-procurement system depends on the extent to which all government procurement practitioners and all actual and potential suppliers to government can access it. In addition, an e-procurement strategy must be anchored by other IT management practices, such as data management, security management and access management.

5. Functionality and standards: The level of functionality required depends on the types of procurement transactions the system is used for. (Conversely, the more complex the transaction, the simpler the system requirements). Selecting open or proprietary technical standards is a complex decision that involves many factors.

Until now, legislation has been the main tool for encouraging the use of e-procurement in Germany. Using legislation to bolster e-procurement is a common approach among OECD countries, with many countries extending the obligation to use e-procurement beyond the core stages of the tendering process (see Figure 4.12).

Figure 4.12. OECD countries offer e-procurement functionalities along the procurement cycle to a differing extent

Source: OECD (2016), Survey on Public Procurement.