Although the HMR boasts a high quality of life, there is potential to harness the region’s full potential through more effective collaborative planning across the HMR. This chapter discusses policies to foster more sustainable and balanced development in the HMR and puts forward recommendations for further action centred on four dimensions: i) housing, land use and spatial planning; ii) mobility; iii) energy efficiency; and iv) quality of life.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Hamburg Metropolitan Region, Germany

Chapter 3. Fostering sustainable and balanced development in the Hamburg Metropolitan Region

Abstract

Box 3.1. Summary of key findings and recommendations

The Hamburg Metropolitan Region (HMR) is an attractive area, endowed with strong assets to face the challenges of population growth and sustainable development. However, this chapter finds that quality of life could be further improved through greater co-ordination across the HMR. More efforts are needed to provide housing in all price segments and improve the accessibility of remote and peripheral areas of the HMR. The high quality of life in the HMR can be further improved and sustained through measures to safeguard natural and cultural resources while making these more accessible to all and utilising the full potential of the renewable energy transition underway in Germany.

To counter the trend of increasing house and rent prices, the stock of low- and medium-income in the housing stock of the HMR should be increased in the places where it is needed. The HMR needs to better match housing supply to the population’s needs both in terms of quantity and quality, encourage compact development of towns and cities, and enhance co-ordinated spatial planning within the HMR. This could be done by conferring spatial planning competencies to a regional planning association covering all or part of the HMR (for example, the Functional Urban Area).

Accessibility in rural areas needs to be improved and the potential of digital mobility solutions could be harnessed to meet environmental goals and reduce spatial disparities in mobility. The proposed course of action includes shifting freight transport from road to rail and alleviating bottlenecks around the core city of Hamburg, implementing a single tariff scheme across the HMR, and increasing the use of public transport where possible.

The energy transition in Germany has the potential to greatly transform the relationship between urban and rural areas, with rural areas poised to become suppliers of renewable energy such as wind energy. The HMR is in a unique position to take advantage of the energy transition. Measures need to be taken to retain and improve the acceptance of renewable energy production, while protecting green spaces through greater co‑operation across administrative boundaries (for example, in biosphere reserves) and promoting energy efficiency to advance environmental sustainability.

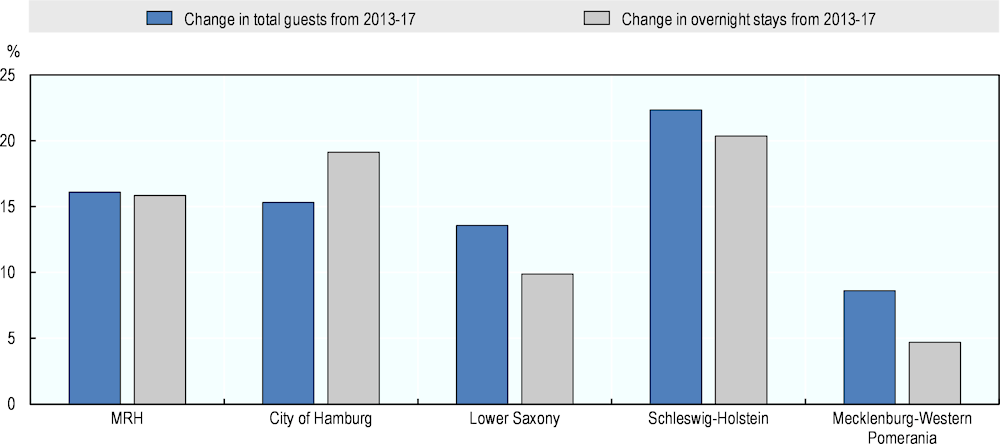

Leveraging the HMR’s cultural assets could help raise the visibility of the whole region to the outside world and strengthen the appeal of the HMR for visitors, firms and skilled workers. Tourism, in particular, could benefit from a shared strategy broadening the focus from the core city of Hamburg to also include joint offers promoting different areas within the HMR.

Introduction

A holistic approach to sustainability should include careful consideration of ecological, social and economic dimensions. Building a strong, sustainable and inclusive HMR not only requires economic development (Chapter 2) but also environmental and social development. The HMR is a monocentric yet heterogeneous region, where the core city, its bordering districts forming the first ring, and the more peripheral districts forming a second ring are experiencing different dynamics (Chapter 1). While housing affordability and availability are central concerns in the core area of the HMR, addressing vacancies and adapting housing to demographic change are more pressing issues in other areas. Many peripheral areas suffer from a low degree of accessibility to the core city by public transport, whereas the core city of Hamburg and its surrounding districts are struggling with bottlenecks both in passenger and freight transport. The outermost districts, where there tends to be less built-up land than in the innermost ones, have the potential to become renewable energy providers for the core city and urban agglomerations in West and Southern Germany, while the energy efficiency of buildings and transport is an important issue for the whole region. Seeing this as a simple urban-rural divide obscures the large diversity of spaces and contexts in the HMR, and thus the innate potential of each space that can be exploited to promote the region’s overall growth and the well-being of its residents.

This chapter discusses policies to foster more sustainable and balanced development in the HMR and puts forward recommendations for further action. It is organised into four sections: i) housing, land use and spatial planning; ii) mobility; iii) energy efficiency; and iv) quality of life. In all these policy areas, different parts of the HMR bring different strengths to the table. It is important to understand these differences as opportunities for co-operation, through which the entire HMR can thrive not despite but because of the interdependencies between different areas. To fully harness this potential, greater collaborative planning in the field of housing, transport, environmental sustainability and branding is needed within the HMR.

Improving housing affordability and making spatial planning more effective

As in many metropolitan areas in which residents may live, work, socialise and commute over various administrative boundaries within a single day, developments affecting one place can spill over these boundaries. One such development is housing in the HMR. As shown in Chapter 1, the city of Hamburg’s population growth has spilled over into its bordering districts and is expected to continue to do so. On the one hand, a housing shortage has been observed in the city of Hamburg, particularly in terms of low- and medium-income housing. On the other hand, other areas of the region must contend with the simultaneous phenomenon of vacancies and a rise in built-up land, as the population grows older and decreases. While the urban core of the city of Hamburg is growing and needs more space for housing and more affordable housing, in particular, areas at the periphery of the HMR often lack housing that is adapted to the needs of the population, such as smaller rental units and housing that is accessible to the disabled.

The Hamburg Metropolitan Region has adopted several policies to address challenges related to housing that differ between the very densified core area, adjacent densifying districts and outer districts, which may feature shrinking and ageing municipalities. Efforts are being made to address different challenges concerning housing at the level of the federal states and through some projects at the level of the HMR.

Responding to a lack of affordable housing and increasing competition between land uses

Housing affordability and provision is a particular concern in the region’s core area, whereas many peripheral municipalities face a mismatch between the quality of housing and the needs of an ageing population.

Increasing the availability of affordable housing

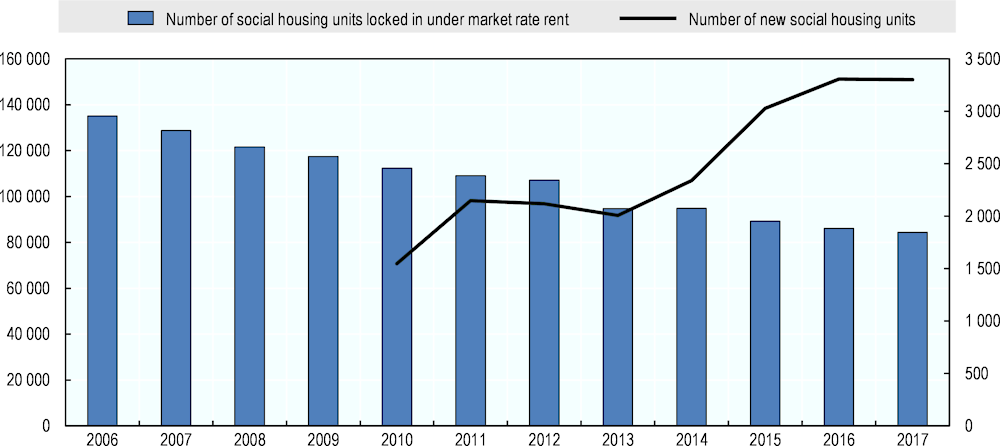

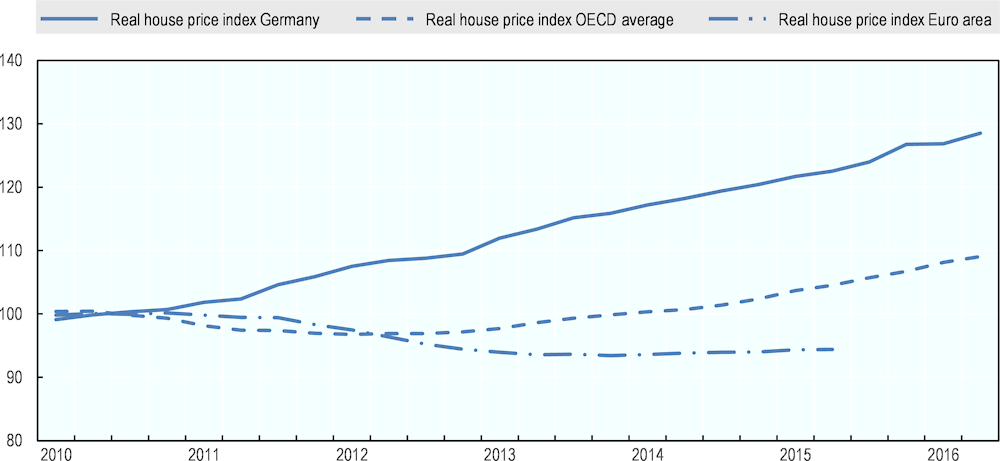

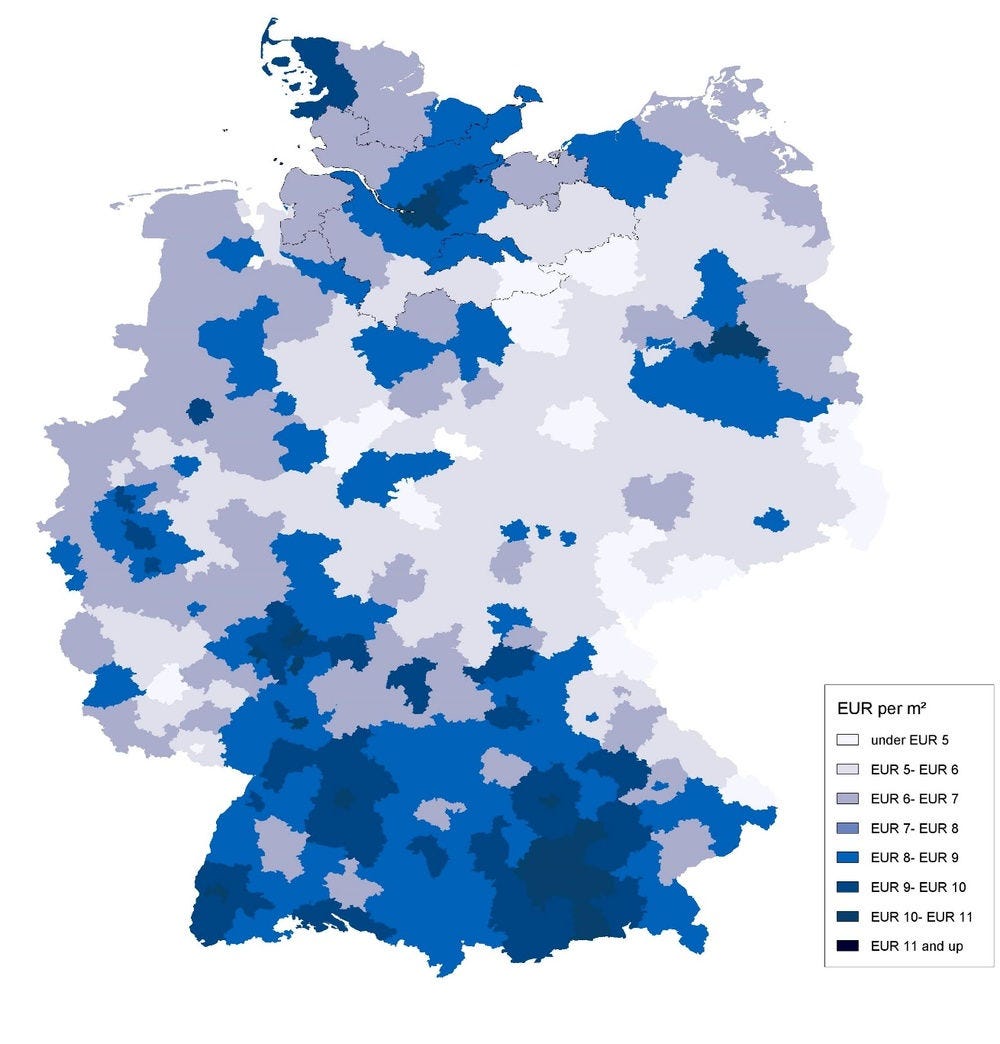

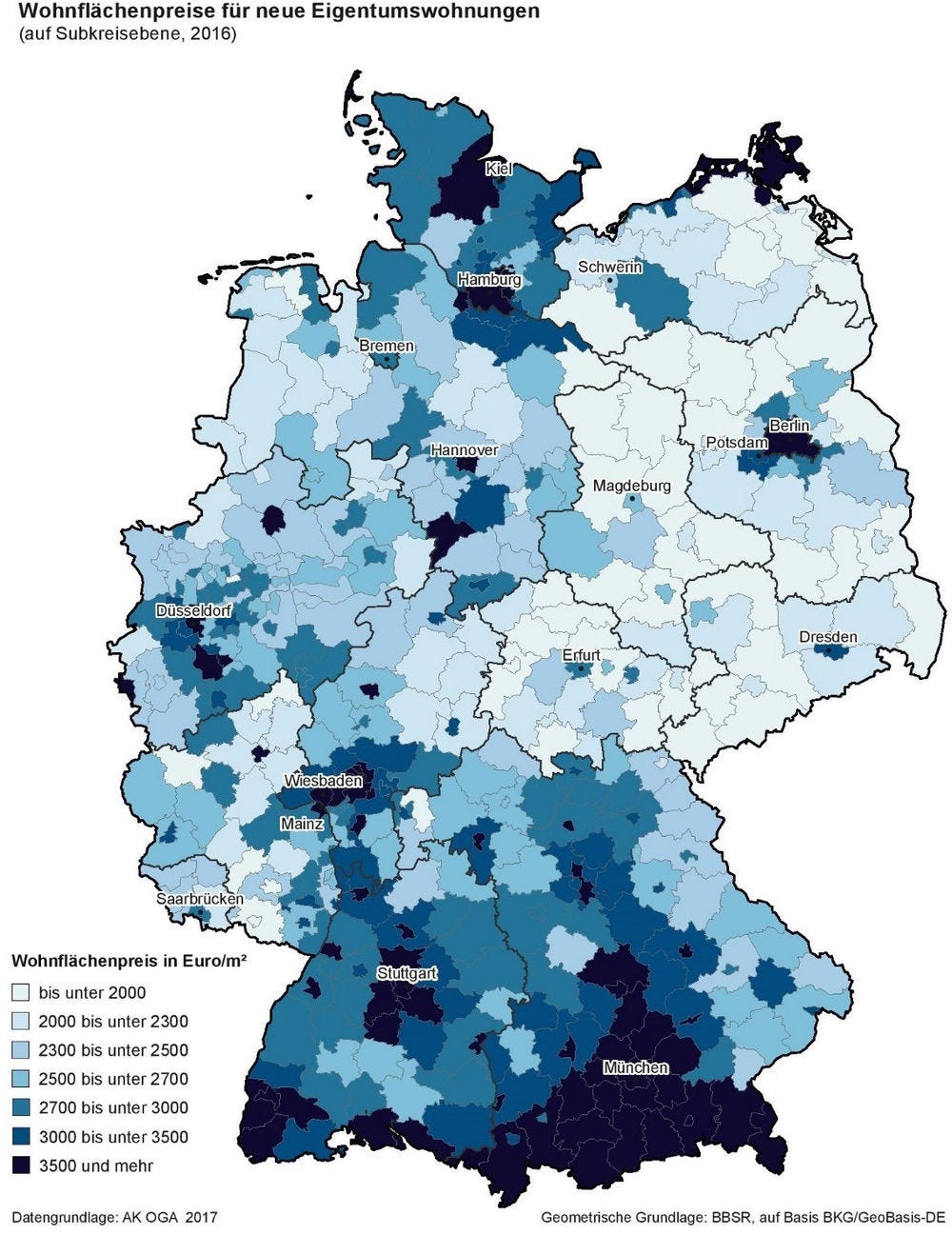

Housing prices decreased or stagnated in the early 2000s in many districts and district-free cities in the HMR, and remained low due to low interest rates in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis (Holtermann and Otto, 2015[1]). However, both rents and housing prices have risen in the years following the financial crisis, and are going up in Hamburg and in districts bordering on it. Even though housing prices in Germany are not among the highest in the OECD, real housing prices have increased faster than the OECD and Euro area average since 2010 (Figure 3.1). If this trend continues, the challenge of providing affordable housing in all price segments will become even more important. As can be seen in Figure 1.3, housing prices in Hamburg were among the highest in Germany in 2016 (Arbeitskreis der Oberen Gutachterausschüsse, Zentralen Geschäftsstellen und Gutachterausschüsse in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 2017[2]) for both apartments and houses. Similarly, rents in the city of Hamburg are some of the highest compared to other German districts and district-free cities (Figure 3.2). While low- and medium-income housing is subsidised by each of the four federal states in the HMR, a main challenge in the upcoming years will be to ensure the affordability of housing for middle-income as well as lower-income groups.

Figure 3.1. Real housing prices have increased more rapidly in Germany than on average in the OECD and the Euro area in the last decade

Note: OECD average data includes all available countries for the OECD area, Euro area data includes the OECD Euro area of 15. Real housing prices have been deflated using the private consumption deflator from the national account statistics.

Source: OECD (n.d.[3]), OECD Housing Price Database, http://www.oecd.org/eco/outlook/House_Prices_indices.xlsx.

Figure 3.2. Rental prices in Hamburg and its surrounding districts are among the most expensive in Germany

Source: IDN ImmoDaten GmbH (2019[4]), BBSR-Wohnungsmarktbeobachtung.

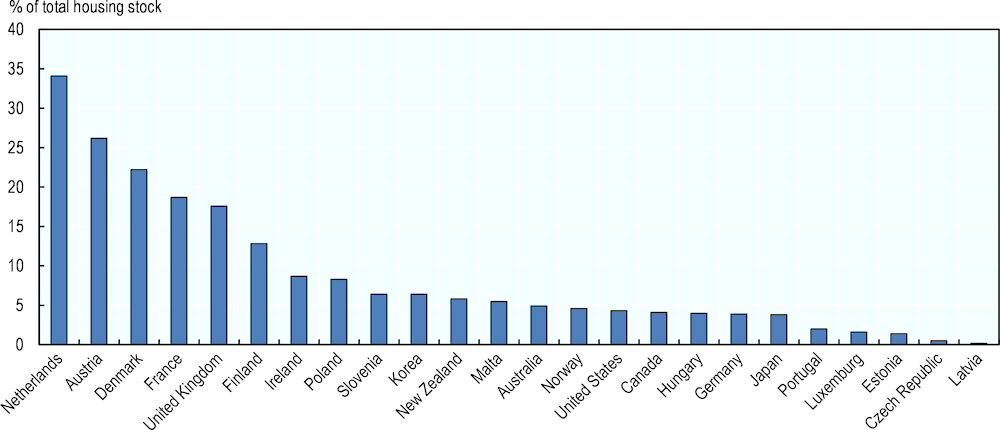

The increase in housing costs can be explained by an increase in land prices and the costs associated with preparing the land for construction. The lack of land made available for development in the urban core of the HMR can contribute to rising land prices by restricting the supply relative to demand. Rising housing costs may also be due to an increase in planning and building costs related to quality and regulatory requirements. An elevation in standards regarding energy efficiency, accessibility, stability and weather safety have all been found to contribute to higher building, and thus higher housing, costs (Walberg, Gniechwitz and Halstenberg, 2015[5]). Rising construction costs are likely to contribute to rising house prices, especially in rural and peri-urban areas, where land is readily available and construction costs constitute a large share of the price of a new dwelling. In contrast, they are less likely to play an important role in expensive areas in cities, where house prices are well above construction costs (Glaeser and Gyourko, 2018[6]). At the federal level, the increase in building costs is being explored by the Baukostensenkungskommission (BKSK or the commission for a decrease in building costs) in the framework of the alliance for affordable housing. Another factor contributing to rising housing and rental costs is the declining stock of subsidised and social housing. Compared to other OECD countries, the share of social rental dwellings in the total housing stock is low in Germany as a whole (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.3. The core city of Hamburg has among the highest housing prices for apartments

Source: Arbeitskreis der Oberen Gutachterausschüsse, Zentralen Geschäftsstellen und Gutachterausschüsse in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (2017[2]), Immobilienmarktbericht Deutschland 2017.

At the federal level, the initiative Bündnis für bezahlbares Wohnen und Bauen- Wohnungsbau Offensive, partially inspired by an earlier effort in Hamburg, aims to increase the pace of housing construction through ten separate measures (Sachs, 2017[7]). Federal guidelines provide a framework for urban and regional planning, within which binding plans are made at different levels. Policy responses to housing shortages and rising rents have also taken the form of policies aimed specifically at supporting low- and medium-income households. Rental caps have been introduced in a number of German municipalities since 2010, including the city of Hamburg and a number of fast-growing municipalities in Lower Saxony and Schleswig-Holstein. However, their effect on breaking the increase in rental prices is contested, with some findings indicating only a small or no effect on rising rents (Kholodilin, Mense and Michelsen, 2016[8]). While rental price brakes may have a positive effect in the short term by taking the sharp edge off of rental increases, they may restrict the housing stock in the medium and long term. They may thus achieve the opposite of their intention, with rents and housing prices increasing in the long term due to an artificially restricted housing market.

In 2017, Germany reformed its urban planning law. The reform lifted barriers to densification and mixed land use in urban areas and lifted some noise pollution restrictions, introducing the “urban territory” category (Urbanes Gebiet) in the building code. This has been a step in the right direction to encourage the construction of housing and compact development. However, more could be done to encourage the construction of housing. While the construction of housing in all price segments is desirable, as a sufficient housing stock can help alleviate prices across the whole region, low- and medium-income housing are important parts of the housing stock and should be encouraged. Affordable housing takes many forms in Germany, among them social housing and housing provided by co-operatives (Wohnungsbaugenossenschaften). In addition, housing benefits are available to pay for market-based rent, providing an important targeted subsidy to alleviate rental burdens. While the stock of directly subsidised social housing is relatively low in Germany compared to other OECD countries (Figure 3.4), providers of publicly subsidised housing include municipal housing companies and co-operatives, individual landlords and commercial developers. Housing co-operatives have a rich history in Germany. They can build new housing and invest in modernising the existing housing stock. In the core city of Hamburg alone, housing co-operatives own around 130 000 housing units, which amounts to 20% of Hamburg’s overall rental housing stock (Hamburger Wohnungsbaugenossenschaften, n.d.[9]). Housing co-operatives are based on a model of joint ownership, in which co‑operative members, who have acquired shares in the co-operative, pay a (typically moderate) fee to live in one of their housing units which belong to all shareholders. Shares are reimbursed if a co-operative member decides to leave the co-operative. As democratic organisations, housing co-operatives regularly elect representatives. The state-owned building company SAGA is another important actor in the housing market of the HMR. Its building stock comprises approximately 130 000 housing units, which are rented, on average at a similar price as subsidised housing units. SAGA and housing co‑operatives combined thus own around 260 000 housing units, making up around one‑third of the rental market in the city of Hamburg.

Box 3.2. The ten goals of the federal initiative Bündnis für bezahlbares Wohnen und Bauen

1. Provide building land and provide public land at a discounted and conceptually-priced standard.

2. Densify housing estates, close fallow land and building gaps.

3. Strengthen social housing promotion and co-operative living.

4. Create targeted tax incentives for more affordable housing.

5. Harmonising building regulations and reducing effort.

6. Reviewing standards and legal requirements in construction.

7. Encouraging serial construction for attractive and affordable living space.

8. Making parking lot regulations more flexible.

9. Structurally redesigning the Renewable Energies Heat Act (Erneuerbare-Energien-Wäremegesetz).

10. Working together to increase the acceptance of new construction projects.

Source: Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (2017[10]), Das Bündnis für bezahlbares Wohnen und Bauen: Das 10-Punkte-Programm, http://www.bmub.bund.de/N54291/.

Figure 3.4. Germany’s directly subsidised social housing stock is low compared to other OECD countries

Note: Data refer to 2011 for Canada, Hungary, Ireland, Luxemburg and Malta; 2012 for Germany; 2013 for Denmark, Estonia, Japan and Poland; 2014 for Australia, Austria, France, Norway and the United Kingdom.

Source: OECD (n.d.[11]), OECD Affordable Housing Database, http://www.oecd.org/social/affordable-housing-database.htm.

Although far from being the only way to ensure affordable housing provision in the HMR, the stock of directly publicly subsidised housing, or social housing, is undergoing several changes that should be taken into account. Since federal reforms in 2006, the construction of social housing is a competency of the Länder, even though it is financed partially by the central government. Within the HMR, there are specific provisions regulating social housing provision. Newly constructed buildings with over 30 housing units must follow the rule of thirds (Drittelmix) in the city of Hamburg: one‑third should contain subsidised housing units, one‑third freely financed rental units and one-third owner-occupied housing units. Despite this requirement, and the fact that Hamburg has had the highest per capita rate of social housing allotment in Germany in recent years, the stock of social housing in the city of Hamburg and in other areas of the HMR has decreased in recent years. This trend has taken hold despite the fact that the number of new social housing units has risen (Figure 3.5). Developers and property owners of social housing are obliged to keep rents “locked in” under the average rate for a minimum of 15 years in return for tax benefits. However, even though many social housing units are being constructed, more units are falling out of their obligation to keep rents lower than average, creating a net decrease in the social housing stock. Monitoring this development and incentivising social housing construction could help formulate long-term strategies to cope with population growth, but it should not be the only type of housing construction encouraged. The construction of housing units in all price segments should be further incentivised to keep the housing stock in line with population growth.

Figure 3.5. The city of Hamburg’s stock of social housing has decreased despite an increase in new social housing units

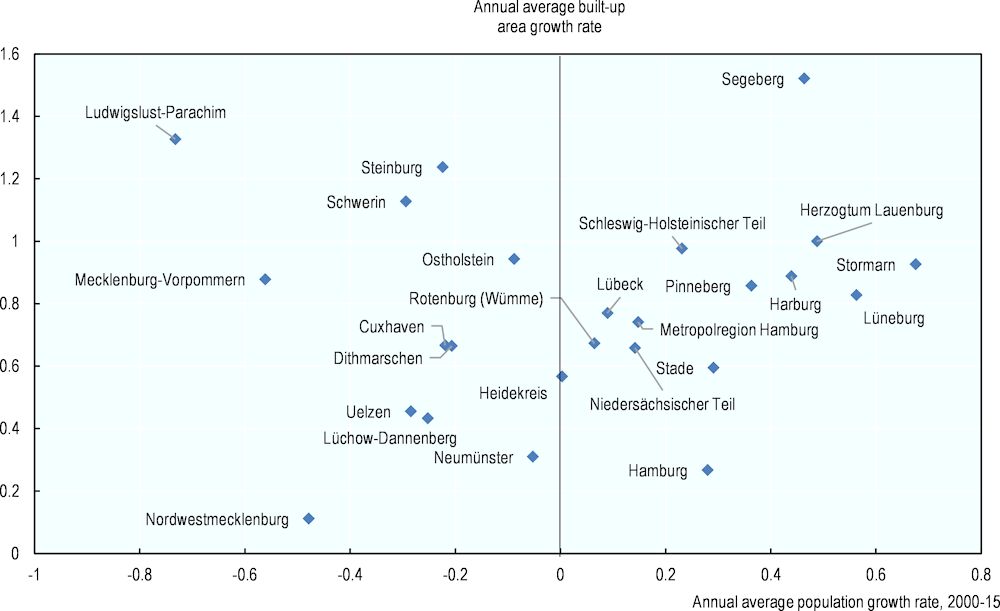

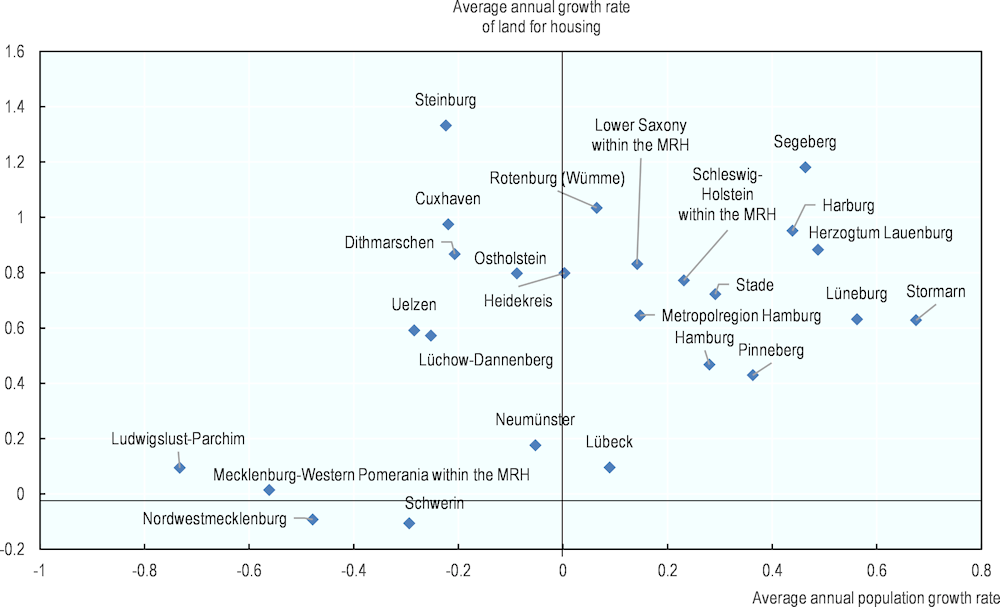

While the HMR is characterised by the coexistence of urban and rural areas within its territory, compact development should not only be considered in relation to large urban agglomerations. Land consumption has increased faster than the population between 2000 and 2015 in all cities and districts of the Hamburg Metropolitan Region except the city of Hamburg (Figure 3.6). The fastest average rates of built-up area growth were attained in the districts of Segeberg (1.52% per year), Ludwigslust-Parachim (1.33% per year), Steinburg (1.24% per year) and the district-free city Schwerin (1.13% per year). At the same time, three of these four areas simultaneously showed negative population growth during this period. Across the OECD, countries increased their built-up areas by 104% between the years of 1950 and 2000 while their population increased only by 66% (OECD, 2012[13]). This tendency is set to continue, with 30 out of 34 OECD countries on track to increase their consumption of land faster than their total population. Looking more closely, however, the disproportionate growth of built-up area occurred primarily outside of large urban agglomerations. In the HMR, each of the ten districts and cities that had a negative annual average population growth rate nonetheless increased their built-up area. A built-up area includes land for the uses of housing, recreation, transport, cemeteries and industry. Examining the growth rate of land used for buildings, a similar picture emerges. Figure 3.7 shows the average annual growth rate of land consumption for buildings plotted against the average annual population growth rate. It shows that the rate of land consumption for building has increased faster than the population in all districts and district-free cities of the HMR except in Stormarn, the district with the fastest population growth. This points to a need to encourage densification in planning and expansion of settlements in the HMR. Even though differing levels of density are among the main differences between “urban” and “rural” areas, compact urban development can have many benefits for residents of large and small cities, such as amenities that are more easily accessible by foot. Compact development can include making village cores more attractive by renovating housing in the centre and thus avoiding the hollowing out of village centres while keeping settlements less dense.

Figure 3.6. From 2000 to 2015, the consumption of land for built-up areas has grown faster than the population in all cities and districts in the HMR except the city of Hamburg

Note: Built-up area (Siedlungs-und Verkehrsfläche) includes area used for buildings, settlement, recreational areas and transport.

Source: Own calculations based on data provided by the office of the Hamburg Metropolitan Region.

Figure 3.7. From 2000 to 2016, land consumption of buildings increased faster than the population everywhere except in the district of Stormarn

Note: Built-up area containing buildings (Gebäude- und Freifläche) includes areas containing buildings and structures as well as open spaces which are subordinate to the purposes of the buildings (gardens, playgrounds, parking lots, etc).

Source: Own calculations based on data provided by the office of the Hamburg Metropolitan Region.

This increasing consumption of land is important to take into account when formulating policy for the HMR, as urban form can affect the environmental and economic performance of cities (OECD, 2012[13]). At the moment, increasing competition between land uses characterises the region, which is trying to develop along specific axes and implement a “central spaces concept” of decentralised concentration and densification. The twofold situation of housing shortages in the core city of Hamburg and its neighbouring districts and an increase in building up of land in most of the region’s periphery calls for a granular approach to land use and construction, which takes into account the nuance of different growth patterns within the region. Urban sprawl in small or large settlements can lead to the loss of agricultural land, the decline of ecosystems and fragmentation of landscapes, less open space and longer distances to recreational areas, and an increased dependency on private car use, leading to “traffic congestion, longer commuting times and distances, climate change emissions, noise and air pollution” (Nilsson et al., 2014[14]). Denser cities can reduce their carbon footprint and provide public services more efficiently. This increasing consumption of land is also important to understand contemporary urban dynamics because of the large economic value of land in the OECD (OECD, 2017[15]), indicating that land should be seen as a resource for cities and regions. Most importantly, a granular approach should be taken to the development of built-up land, as urban sprawl in the second ring can coexist with housing shortages in the urban core. The demand for single-family houses seems to be rising across the HMR in the future, while demand for apartment buildings seems to be increasing in and around its urban core but decreasing at its fringes. Encouraging compact and transit-oriented development can make this new development as sustainable as possible. The nature of the future spatial development of cities in the HMR is crucial if they are to benefit the region and its residents. A holistic approach to land use which takes into account the land requirements for housing, transport, industry, craft and commerce, nature and open areas could help reduce competition among actors, which could, in turn, ease the implementation of strategies seeking more compact development and building where it is most needed.

Even though the HMR does not have concrete competencies in the fields of planning and housing, it has been actively engaged in trying to ensure balanced spatial development and densification of urban areas within its territory. The HMR thus draws on a long tradition of integrating the issue of sustainable land use and inter-municipal co-ordination in regional co-operation. The HMR’s project on inner development (Leitprojekt Innenentwicklung) is a recent example, with projects in five model towns and cities facilitating access to technical knowledge needed to guide densified planning and creating good examples for other municipalities in the HMR to emulate. The project focused on densification, upgrading open spaces in town centres, increasing retail opportunities in town centres, mobility and services, communication strategies, and strategies for participation to involve property owners and residents. The toolkit of instruments which proved to be effective tools in the planning and implementation of these projects were gathered and can provide valuable assistance to other municipalities in implementing similar strategies.

Overcoming a fragmented planning framework to plan long-term infrastructures

In order to develop integrated spatial plans, co-ordination in planning and housing policy within the HMR is indispensable. However, there has been no basis for joint planning since the Regionaler Entwicklungsplan (REK) in the year 2000, which could be entered in on a voluntary basis. In the years since the elaboration of this non-binding agreement, co-operation in planning matters has largely taken the form of individual projects, without an overarching strategy or guideline. Some of these have also been developed making use of the metropolitan funding system but without the direct support of the HMR Office. Co‑operation in spatial planning across federal boundaries would involve co-operation between the supreme planning authorities and/or regional planning agencies in each of the four federal states comprising the HMR. However, co-ordination of housing policy in the region is made more difficult by the fact that spatial planning is organised differently in all four states comprising the HMR. The city of Hamburg, as a city-state, is responsible for the elaboration of its own plans, while the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania has regional planning bodies (Regionale Planungsverbände) and Lower Saxony’s districts themselves are responsible for spatial planning. In Schleswig-Holstein, the state has the planning authority (oberste Landesplanungsbehörde).

The resulting plans at the regional level are not harmonised between each other and operate at different scales, making co-operative planning across administrative boundaries difficult. In other German metropolitan regions (Metropolregion, MR), planning across administrative boundaries is done through the establishment of planning associations, for example in MR Rhein-Neckar (Box 3.3). The differences range from differences in the scale of analysis to the different concepts of planning which create friction between each other. The perceived competition between different forms of land use is a challenge for spatial planning, both at the local and at the regional levels, and is a hurdle for potential HMR-wide planning. While space devoted to housing, green spaces, commercial space and other uses such as transport has increased in areas that used to be sparsely built up and are experiencing rapid population growth, vacant sites are present in some peripheral rural parts of the region. Municipalities have the final say in planning decisions and many have reservations about growing any further due to concerns such as the provision of sufficient infrastructure.

Table 3.1. Spatial planning competencies and guidelines in the HMR

|

City of Hamburg |

Lower Saxony |

Mecklenburg- Western Pomerania |

Schleswig-Holstein |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

State guidelines |

Grüne, gerechte, wachsende Stadt am Wasser“ - Perspektiven der Stadtentwicklung für Hamburg |

Landesraumordnungsprogramm (LROP) 2008, last updated 2017 |

Landesraum-entwicklungs-programm (LEP) 2016 |

Landesentwicklungsplan (LEP) 2010, update started in 2013 ongoing (to be completed in 2021) |

|

Body with regional planning competencies |

City of Hamburg |

Districts Cuxhaven, Harburg, Heidekreis, Lüchow-Dannenberg, Lüneburg, Rotenburg (Wümme), Stade and Uelzen |

Regional planning association Westmecklenburg |

Ministry of the Interior |

|

Regional plans |

Same as federal guidelines |

8 regional development plans |

Regional planning programme Westmecklenburg |

Regional plans for regional areas I, II and IV |

|

Year of most recent plan |

2014 |

2004 (Lüchow-Dannenberg) to 2017 (Cuxhaven) |

2011, partial update started in 2013 is ongoing |

2014, updated in 2018 |

|

Planning scale |

City-state |

District |

Regional (planning region comprising two districts and the state capital Schwerin, a district-free city) |

Regional (three planning regions are part of the HMR) |

Source: Metropolregion Hamburg (n.d.[16]), Regionalplanung in der Metropolregion Hamburg, http://metropolregion.hamburg.de/regionalplanung/.

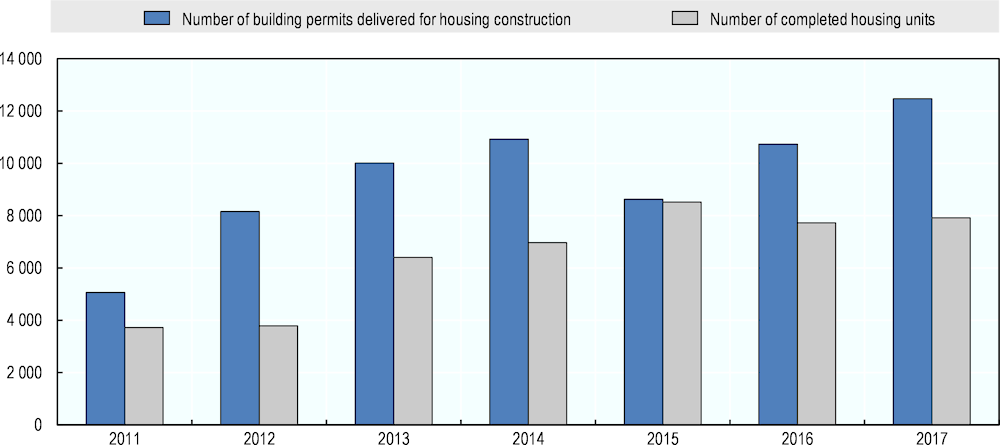

One area in which the fragmented planning structure results in inefficiencies is housing. In the four Länder composing the HMR, strategies and concepts regarding housing are focused mainly on its affordability (Table 3.2). Recognising the looming housing shortage and the need to stimulate the building of housing, Hamburg signed a contract with its seven urban districts (Vertrag für Hamburg) in 2011, to be integrated into the Alliance for Housing in Hamburg (Bündnis für das Wohnen in Hamburg). The main goal of this contract was to speed up the delivery of building permits, with the aim of delivering permits within six months of an application (Senat Hamburg, 2011[17]). The contract also aimed to increase the construction of housing to 6 000 units per year, a goal increased to 10 000 units in 2016. In addition to the faster delivery of permits and construction of housing units, the new contract established that 30% of new housing units would be publicly subsidised, thus benefitting low- and medium-income households which have been particularly affected by the rise in rental prices in Hamburg (Senat Hamburg, 2016[18]) and avoiding a concentration of social housing in specific areas. Hamburg’s efforts to increase the provision of building permits have shown promising results, with the number of building permits having increased from 6 800 in 2011 to 12 411 in 2017. The difference between planned and constructed housing units points to potential growth in the future.

Table 3.2. State housing policies and strategies in the HMR

|

City of Hamburg |

Lower Saxony |

Mecklenburg- Western Pomerania |

Schleswig-Holstein |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Strategy |

Vertrag für Hamburg |

Bündnis für bezahlbares Wohnen in Niedersachsen |

Allianz für das Wohnen mit Zukunft in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern |

Wohnraumförderungsprogramm 2015-2018 (continuation of Offensive für bezahlbares Wohnen in Schleswig-Holstein) |

|

Actors |

City of Hamburg, urban districts, housing industry associations |

Ministry for the Environment, Energy, Construction and Climate Protection of Lower Saxony, Association of Housing and Real Estate in Bremen and Lower Saxony, businesses, chambers, various institutions and associations, districts and municipalities |

Ministry of the Economy, Construction and Tourism of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and housing industry associations |

Ministry of the Interior of Schleswig-Holstein Housing industry associations |

|

Focus and goals |

Construction of 10 000 housing units per year (since 2016), of which 30% are to be publicly subsidised, delivery of building permits within 6 months of application |

Five working groups with the themes: subsidies and financing; land; construction regulations; buildings, planning and construction; development of existing housing stock |

Continuity of financing and subsidies, demographic change, affordability for all, development of the existing housing stock, energy transition, urban planning |

Focus on target regions characterised by a high increase in rents and growing housing demand by supporting the construction and renovation of 4 200 social housing units and supporting student housing, with incentives to increase energy efficiency and accessibility of privately-owned rental units |

Sources: Own elaboration based on Senat Hamburg (2011[17]), Vertrag für Hamburg-Wohnungsneubau Vereinbarung zwischen Senat und Bezirken zum Wohnungsneubau; Senat Hamburg (2016[18]), , Vertrag für Hamburg- Wohnungsneubau Fortschreibung der Vereinbarung zwischen Senat und Bezirken zum Wohnungsneubau; Bündnis für bezahlbares Wohnen in Niedersachsen (n.d.[19]), Startseite, https://www.buendnis-für-bezahlbares-wohnen.niedersachsen.de/startseite/; Ministry of the Economy, Construction and Tourism of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (2014[20]), “Allianz für das Wohnen mit Zukunft in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern”; Innenministerium des Landes Schleswig-Holstein (2013[21]), Rahmen-Vereinbarung zur schleswig-holsteinischen Offensive für bezahlbares Wohnen.

Figure 3.8. The number of building permits issued in the city of Hamburg has increased since the implementation of the Vertrag für Hamburg in 2011

Source: Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein (2018[22]), Hochbautätigkeit und Wohnungsbestand in Hamburg 2017, Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein.

Similar initiatives have been employed in Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig-Holstein, where the Länder have entered into co-operative agreements with housing industry associations to ensure the sustainable provision of affordable housing. The most inclusive of these is the grouping for affordable housing in Lower Saxony (Bündnis für bezahlbares Wohnen in Niedersachsen), which groups together businesses, chambers, various institutions and associations, districts and municipalities in addition to housing industry associations and the Land. The holistic view that many of these strategies bring to affordable housing is a welcome development. The areas of energy transition and efficiency, demographic change, urban planning and the development of existing housing stock are all related and have been used as considerations in affordable housing strategies. In rural areas facing population decline, the renovation and adaptation of the existing housing stock will be important to increase energy efficiency and increase the attractiveness of village cores. Provisions such as the one in Schleswig-Holstein, which sets the amount of social housing to be renovated in addition to that being newly constructed, are a good start toward framing the need for a higher affordable housing stock as a problem of housing provision, not only new construction. The planning of essential infrastructure such as housing could be better co‑ordinated between the four Länder and planned in the long term.

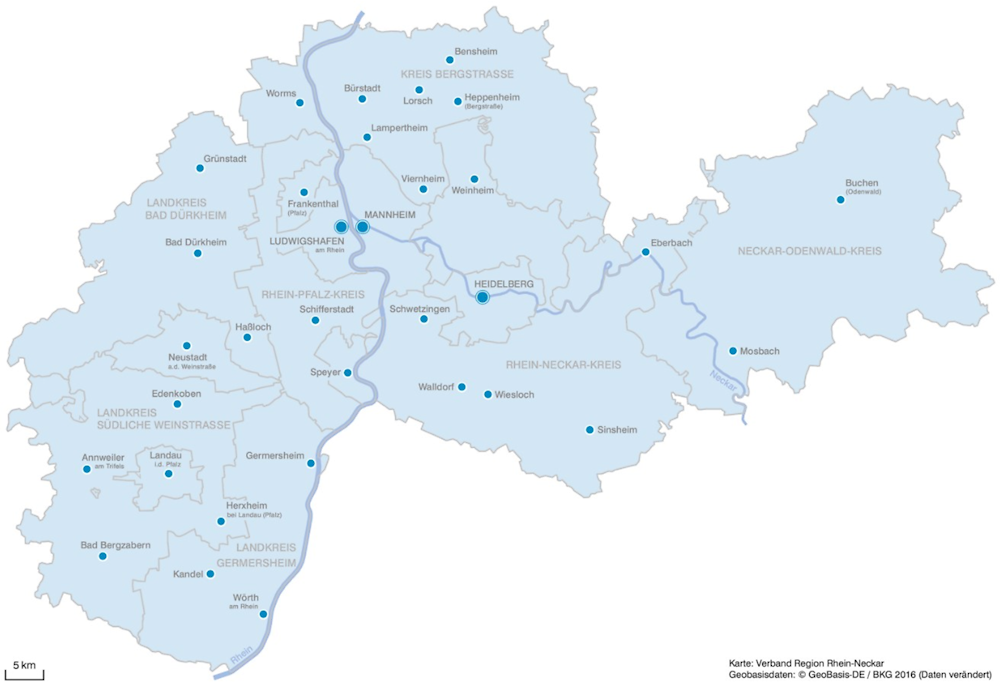

Box 3.3. Spatial planning in the Metropolitan Region of Rhein-Neckar

Spatial planning beyond administrative borders in a German metropolitan region

Metropolregion Rhein-Neckar, or MR Rhein-Neckar, located in the southwest of Germany, is composed of 15 districts and district-free cities spanning 3 Länder: Baden-Württemberg, Hessen and Rheinland-Pfalz.

Figure 3.9. MR Rhein-Neckar

Source: Metropolregion Rhein-Neckar (n.d.[23]), Kartenmaterial, https://www.m-r-n.com/meta/medien-und-publikationen/karte (accessed on 20 December 2018).

A state treaty from the year 2005 gave spatial planning competencies to the Verband Region Rhein-Neckar, a newly formed planning association. Signed by the three Länder, the treaty gave competencies to the Verband in the areas of economic development, to develop a regional landscape park and recreational area, to plan regional congresses, cultural, and sports events and for regional tourism marketing. They were also given the responsibility of co-ordinating activities in integrated traffic planning and energy supply on the basis of regional development plans.

The plans are formulated by the assembly of the association, which is democratically elected. Its 93 members comprise 70 members elected at the district or municipal level. In addition to these, district mayors and mayors of cities with more than 25 000 residents are automatically part of the assembly. The resulting unified regional plan sees its main goals as the maintenance of the region’s high attractiveness as a living and economic area and further increasing its development opportunities.

Sources: Land Baden-Württemberg, Land Hessen, Land Rheinland-Pfalz (2005[24]), Staatsvertrag zwischen den Ländern Baden-Württemberg, Hessen und Rheinland-Pfalz über die Zusammenarbeit bei der Raumordnung und Weiterentwicklung im Rhein-Neckar-Gebiet; Verband Region Rhein-Neckar (2013[25]), Einheitlicher Regionalplan Rhein-Neckar: Plansätze und Begründung.

Targeting housing affordability by improving policy integration and co‑ordination

The progress of Vertrag für Hamburg’s increase in building permits is a good start for the core city of the region to address affordable housing. However, housing must be seen as an essential infrastructure and planned in the long term in order to keep it affordable to all its residents throughout the whole HMR.

Match housing supply to needs

Encouraging housing construction generally should be a main goal followed by all actors of the HMR. While there must be an increase in the number of housing units in areas with a rapidly growing population, it is important that they have the right characteristics and target the right needs in the various areas. Rental units, multi-family homes, social housing units and housing adapted to the needs of an ageing population, for example, will speak to different segments of the population and can respond to their specific needs. Even though rural regions tend to be characterised by single-family homes, it will be necessary to build apartment buildings in some fast-growing rural regions (Chapter 1). In rural districts such as Lüchow-Dannenberg (Lower Saxony), one of the main challenges is densification and changing the nature of buildings, for example ensuring the re-use of farms and other vacant buildings. Projects in the HMR such as Hofleben, an inter-generational housing project in the district of Lüneburg, and neues Leben auf Alten Höfen in Lüchow-Dannenberg (both in Lower Saxony) show how old farms and similar buildings can be rehabilitated. Areas facing demographic change and ageing populations may face the additional challenge of a lack of housing opportunities tailored to the needs of elderly occupants. Zoning thus has to serve the specific needs of the area concerning the nature of housing. The HMR could also provide a platform for providing further transparency on the housing market of the region, using tools such as WoMo which are already at its disposal.

The HMR should carry out qualitative and quantitative needs assessments to make sure that its housing stock matches the different needs of the population and development patterns with regard to both quantity and quality. On the one hand, the supply of housing in the core area should keep up with population growth in order to remain affordable. On the other hand, the quantitative supply of housing must have the right qualitative characteristics of the housing stock.

Quantitatively, different parts of the HMR have different needs regarding the housing stock. The city of Hamburg does not carry out a quantitative needs assessment of housing units but strong population growth will need to be accompanied by an increase in housing stock, particularly in apartments with one or two rooms to match the trend toward smaller households (Holtermann and Otto, 2015[1]). Insufficient housing supply will lead to rising costs if demand for housing increases, which it likely will (Chapter 1). Furthermore, housing should be planned as a long-term infrastructure in the HMR and construction encouraged in all price segments. While incentivising developers to build social housing, and locking them in this designation for a pre-determined amount of time is a good way to increase the stock of social housing, there must be forward-looking planning in order to keep the social housing stock at a stable number even after this period is over. Currently, the city of Hamburg’s social housing stock is declining even though the construction of social housing units is increasing, because older social housing is falling out of this category. This has to be addressed by making long-term housing plans that go beyond electoral cycles and continually monitoring the social housing stock to ensure that it stays stable. Developers should also be provided with incentives to increase the amount of time they rent housing units under the average cost. However, social housing alone cannot ensure affordable housing for all. Increased supply in market housing can help reduce rents in the free market in the areas which are now experiencing a sharp increase in rent and housing prices, and should thus be encouraged. In other, more peripheral areas of the HMR, there should be a focus on the renovation of the existing housing stock to match the needs of its residents and, when new housing must be constructed, there should be a targeted impulse toward building new housing along transport corridors.

Matching between housing quality and needs of residents should be supported in part by tailoring the size of housing units to household size. This would imply encouraging densification and increased housing stock in growing towns and cities while creating solutions for shrinking cities, where ageing and net out-migration can decrease the population substantially. Fostering innovative housing projects and strategies for elderly residents would help adapt housing supply to population characteristics. This approach could include encouraging the adaptive re-use of single-family homes or other buildings, for example through accessory dwellings. Many areas characterised by ageing populations are also facing a decrease in household size, as children age and move out of shared accommodations. However, high transaction costs, including the cost of moving, can inhibit people from leaving their large houses for smaller units. A key recommendation is thus to lower the transition costs of moving for elderly people who are looking to downsize by providing exchange platforms for housing and by providing moving support. This would make larger housing units available to those who might otherwise have constructed a new single-family home, thus limiting the amount of land used for new housing construction in shrinking areas. Another step toward limiting the transaction costs of moving would be to rethink the Grunderwerbsteuer, or land and real estate transfer tax, which today is very high in Germany and may provide disincentives to those trying to move by limiting mobility and leading to an inefficient distribution of the housing stock.

Encourage the compact development of towns and cities

Compact development should be encouraged by providing targeted support to municipalities. Making settlements more compact can benefit residents by providing more walkable spaces with basic services accessible closer to where people live. In cities and towns facing ageing populations, this could increase the autonomy of the elderly, while reducing residents’ reliance on car transport. Municipalities could be encouraged to identify their own potential for re-densification, as well as vacancies and potential vacancies (Baulücken- und Leerstandskataster), and create holistic concepts for their densification. Incentives could be given at different levels, from tax incentives to technical assistance and grants, which could be given out to municipalities with innovative strategies and publicise them as best practices. Preventive vacancy management should also be promoted. Some German municipalities such as the small Bavarian town of Blaibach have successfully provided community spaces such as concert halls in formerly vacant lots that enhance the city with their architectural quality and can provide a point of civic pride (Bundesstiftung Baukultur, 2017, pp. 82-83[26]). The key HMR project Leitprojekt Innenentwicklung has provided valuable impulses for densification, vacancy management and housing adaptation, but the possibilities provided by recent reforms in planning law can be exploited further. The toolkit developed by the HMR through this project is a valuable resource, and expanding the dissemination of successful models featured in it could convince other municipalities of the benefits of densifying their town centres and providing help for new residents to renovate and move into existing housing units. Where greenfield development takes place, efforts should be made to ensure that it is as compact as possible.

Enhance co-ordinated planning within the HMR

Co-ordinating planning through the creation of a planning association covering a portion of the HMR (representing the Functional Urban Area) would benefit the region. Furthermore, an update of the regional development plan (REK 2000) encompassing recent development trends is desirable. Competition for space for housing, commercial activity, industry and free space means that the potential of the HMR is not being fully harnessed. The lack of co-ordination and co-operation may generate a cost for residents, businesses and subnational governments. OECD data shows that a higher level of administrative fragmentation of a metropolitan area, measured by the number of municipalities, is correlated with lower levels of labour productivity (OECD, 2015[27]). Doubling the number of local governments within a metropolitan area diminishes its labour productivity by 6%, thus possibly reducing the gains from agglomeration benefits (OECD, 2015[27]). OECD data suggests that urban areas with metropolitan governance bodies in place show less urban sprawl (Ahrend, Gamper and Schumann, 2014[28]) and can mitigate the aforementioned productivity loss (OECD, 2015[27]).

Housing and land use policy could be better integrated and co-ordinated throughout the HMR through the development of a regional plan. The region, heterogeneous as it may be, shows potential for co-ordination and co-operation which could help stem the perceived competition between land uses and ensure a more balanced spatial development. Co-ordination in planning throughout the HMR can help provide services at the right scale, since not every public service is best provided by individual municipalities or districts. In some cases, a service provided in one municipality, district or Land may also create positive or negative externalities for residents of other places, and co‑ordinated planning can constitute a mechanism to address these. For example, building a new residential neighbourhood in one municipality can increase congestion throughout the metropolitan area if it is not well connected to the public transport network. At the same time, it might also increase the value of land and existing housing in the vicinity of the new development. Therefore, effective policies regarding land use, housing and other sectors go beyond the limits of the current planning regions as they are enmeshed in the functional area of the HMR. Defining the right areas within the territory of the HMR for settlement growth, commercial space, industry and green space by co-ordinating them throughout the HMR can make planning more efficient. Co-operative management and planning of space at the level of the HMR with clear directives of where to target settlement growth could help the region grow in a sustainable manner and should thus be a main goal of the region. Several projects of the HMR already aim at increasing co‑operation in the management of space, for example, its industrial space concept GEFEK (Konzept zur Gewerbeflächenentwicklung) and the commercial space information system GEFIS (Gewerbeflächeninformationssystem). The latter provides information on commercial spaces available in the HMR online for investors. From 2019/20 onward, it will also contain an internal monitoring system for business promoters and planners in the HMR. However, joint planning instead of merely joint marketing could help the HMR avoid urban sprawl and manage land more sustainably. Other metropolitan regions in Germany do engage in joint spatial planning, even across state boundaries (see Box 3.3 on spatial planning in MR Rhein-Neckar). A state treaty between the four Länder composing the HMR could establish a planning association within the office of the HMR and confer spatial planning competencies to it. Alternatively, implementing a more narrowly defined regional planning association could be more feasible politically and logistically, while still contributing to the co-operative planning needed for a sustainable region. The resulting planning region could also encompass the Functional Urban Area (FUA) of the HMR.

Box 3.4. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP)

Created in 2005, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) is the regional planning organisation for the north-eastern Illinois counties of Cook, DuPage, Kane, Kendall, Lake, McHenry and Will, comprising 284 communities. Operating under a public act and local by-laws, it is the official co-ordination and planning body for land use and transport. The CMAP’s board of directors is composed of representatives from across the 7 counties represented in the agency, with 15 members: 5 from the city of Chicago, appointed by the Mayor of Chicago; 5 from suburban Cook County, appointed by county mayors in conjunction with the President of the County Board; and 5 members representing the remaining counties co-operatively appointed by the counties’ mayors and chief elected county officials. The board is chaired by a mayor. The skills and backgrounds represented in the board’s composition are varied, with approximately half of the board members being mayors, several former elected officials and other representatives form business and civic associations.

In its comprehensive plans GO TO 2040 and the subsequent ONTO 2050, the questions of transport, housing, economic development, open space, the environment and other issues impacting quality of life for the residents of the greater Chicagoland area are addressed. In 2010, CMAP established a Local Technical Assistance programme to encourage local planning work that follows the framework of the regional plan. Since then, it has initiated over 200 local projects with local actors including local governments, non-profit and intergovernmental organisations.

Source: CMAP (n.d.[29]), Local Technical Assistance, https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/programs/lta.

Improving mobility management and harnessing new technologies to improve accessibility

As a region whose numerous ports (Brunsbüttel, Hamburg, Lübeck) and infrastructures such as the Kiel Canal support a large maritime and export industry, the HMR’s priorities in sustainably managing transport and mobility throughout the region are twofold. While the metropolitan region requires good passenger transport management, freight traffic is also a major feature of the region and must be considered in tandem with passenger transport.

A crucial challenge for the whole HMR in rail transport is the creation of additional capacities at the bottleneck Hamburg Central Station, which is highly important for international, national and regional rail traffic. This significant role as a railway node has been recognised by the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2030 (Bundesverkehrs-wegeplan 2030). Currently, measures to expand capacity of the Central Station and in other parts of the juncture Hamburg are being further examined by the federal government. The construction of the S4 line between the Central Station and Bad Oldesloe (Schleswig-Holstein) will increase capacity by unbundling regional and long-distance traffic on this part of the trans-European Scandinavian-Mediterranean Corridor. Hence, this project is of particular importance for the HMR. It will additionally create the possibility to increase the capacity of the Central Station by the building of a new platform. Capacities are limited and will not be able to sustain increased passenger numbers (Holtermann et al., 2015[30]). In addition to the rail station, the city of Hamburg itself is considered a bottleneck for road transport. Measures to relieve the traffic network include the extension of the rail node Hamburg and extensive works on the motorways A7, A1 and A26 as foreseen in the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan, as well as the motorways A20, A21 and A23. The A26 (so-called “Hafenpassage”) will also serve to circumvent parts of the city centre. Good accessibility is in general also necessary in terms of symbolic coherence of the territory by connecting peripheral areas. In spite of the commitment to sustainable mobility, the importance of car traffic for the connection within the region must not be neglected. Bicycle traffic is playing an increasingly important role in the regional context, with the design of a network of cycle highways being one of the main projects in the HMR.

Countering disparities in accessibility

Efforts have been made at all levels of the HMR to provide the region with sustainable mobility services. Several large infrastructure projects are underway in the HMR which will have a sustained effect on both freight and passenger transport. Attracting more people to use local public transport will remain the primary objective of sustainable mobility management in the HMR. This is hoped to be achieved by strengthening public transport by increasing its capacity, more frequent scheduling and through tariff adjustments in areas of the region sufficiently populated to maintain transport infrastructure.

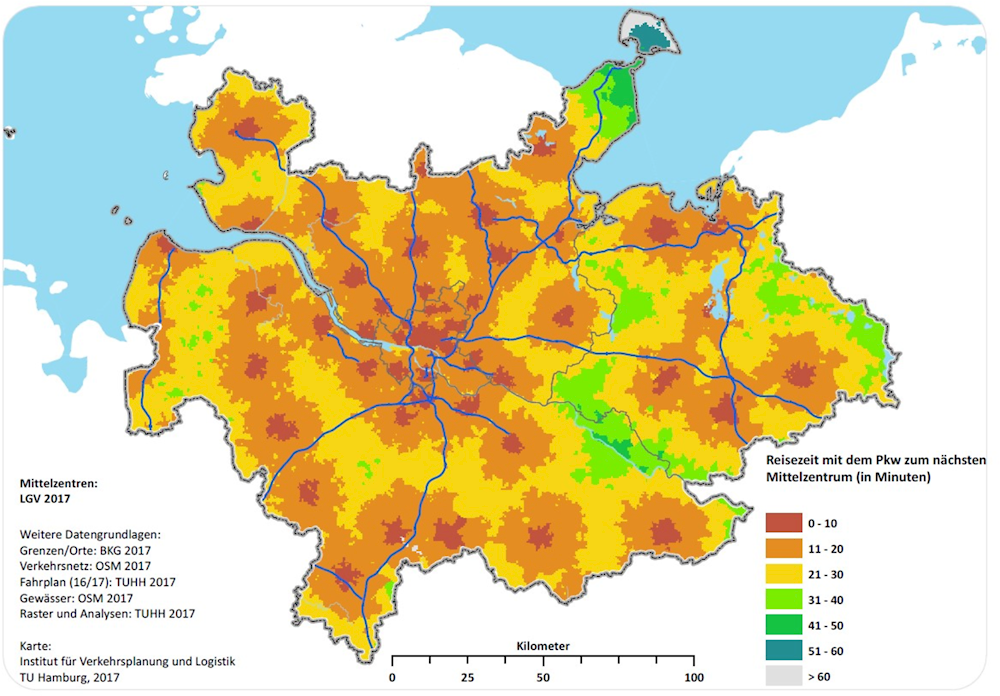

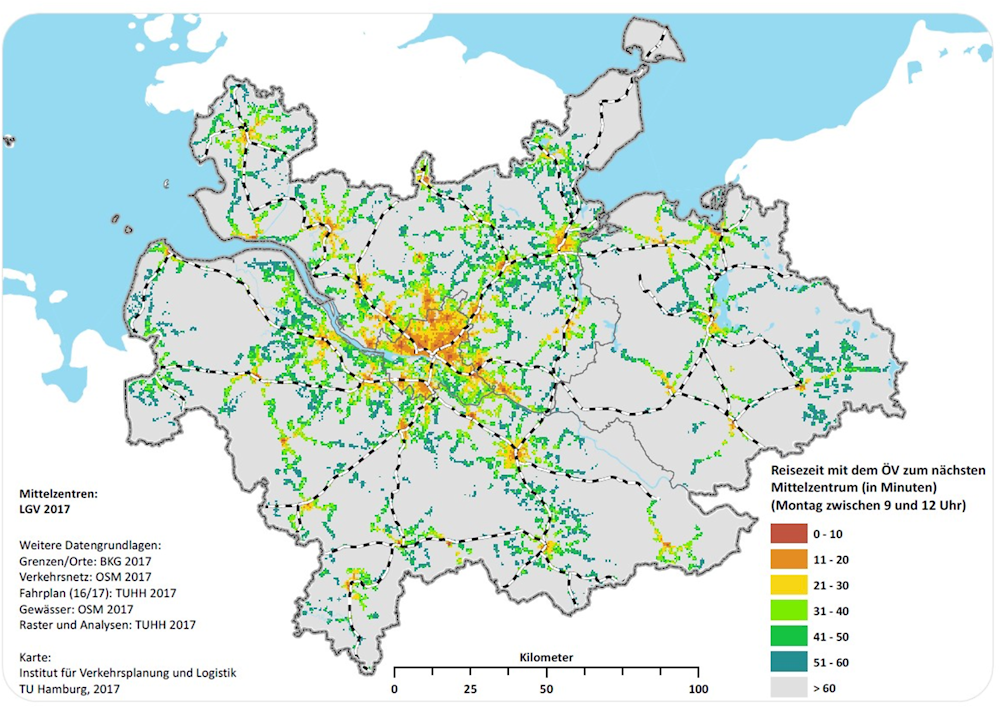

Improving accessibility in rural areas

As in the field of housing, needs and challenges related to mobility vary throughout the heterogeneous region. While there are efforts underway to improve the network of light railways around the city of Hamburg (both the aforementioned S4 and the S21 lines), connectivity to the core city of Hamburg, the next largest agglomeration, or the next urban centre where specific goods and services can be accessed remains an issue in the region. The disparity in connectivity in different parts of the HMR is clearly visible when comparing the amount of time that is necessary to reach the next medium-level centre (Mittelzentrum) by car and by public transport. Figure 3.10 illustrates the accessibility of the next medium-level centre by car, showing that the vast majority of areas within the HMR are within 30 minutes of the next medium-level centre by car. In contrast, public transport only allows for accessibility of medium-level centres in over 60 minutes in much of the region (Figure 3.11).

Figure 3.10. Accessibility of the next medium-level centre by car in the HMR

Note: Medium-level centre (Mittelzentrum) is a qualitative description of an agglomeration in the German central place classificatory system, according to the administrative, social and economic functions it performs in a polycentric system of cities.

Source: Institut für Verkehrsplanung und Logistik TU Hamburg (2017[31]), Leitprojekt Regionale Erreichbarkeitsanalysen: Abschlussbericht und Erreichbarkeitsatlas, http://www.metropolregion.hamburg.de/erreichbarkeitsanalysen.

While residents of the core city of Hamburg use more sustainable modes of transport on a daily basis, including 22% in public transport (BMVI und infas, 2018[32]), peripheral areas of the HMR show a higher rate of car use. Policy goals emphasise the importance of multimodality in the region, but car use cannot be fully discounted in areas that are not well served by public transport. A feasibility study for high-speed cycle-lanes connecting different areas of the HMR has been conducted, laying the ground stone for commuter traffic to move from cars to bicycles. Other policies to facilitate the use of several different modes of transport are Park-and-Ride and Bike-and-Ride facilities, which exist throughout the region. However, these underlie different regulations according to the administrative districts they are situated in. Hamburg and some municipalities are moving to a fee-based model for these facilities. However, this could create a disincentive for those who could otherwise be willing to use them. Furthermore, without harmonisation between these and other districts, the presence of some fee-based and some free park-and-ride facilities greatly influences the conditions for multimodality in these places. Further efforts can be made to ensure that Park-and-Ride facilities provide enough capacity to fulfil demand and to encourage mixed facilities with parking spots for a number of different modes of transport (car, bike, scooters, etc.) to encourage multimodality. In addition, new developments in mobility brought forth by digital solutions should be taken into account when designing these facilities, including digital solutions such as real-time information on capacities and online booking options.

Figure 3.11. Accessibility of the next medium-level centres by public transport in the HMR

Note: Medium-level centre (Mittelzentrum) is a qualitative description of an agglomeration in the German central place classificatory system, according to the administrative, social, and economic functions it performs in a polycentric system of cities.

Source: Institut für Verkehrsplanung und Logistik TU Hamburg (2017[31]), Leitprojekt Regionale Erreichbarkeitsanalysen: Abschlussbericht und Erreichbarkeitsatlas, http://www.metropolregion.hamburg.de/erreichbarkeitsanalysen.

Stakeholders are hopeful that new digital technologies can help improve traffic and mobility management while creating more flexible mobility arrangements for residents of rural areas. Hamburg’s planning tool ROADS, for example, co-ordinates construction site planning within Hamburg and could be expanded to co-ordinate with surrounding communities. Rural areas are also being included in efforts to digitalise freight transport, with inland shipping and sluice management being focal points. Flexible forms of use are also expected to increase the mobility of those in peripheral regions where the public transport network is rather small. At the level of the HMR, a toolkit for flexible mobility services in rural areas has been created, which is available to municipalities looking for specific tools to improve service provision.

Reducing bottlenecks and increasing links with Scandinavia

The steady growth of commuters requires transport infrastructure development to cope with a lack of capacity in rail and road transport. Adding to this is the issue of environmental protection, with Hamburg recently being the first German city to ban older diesel vehicles on two road sections in a centrally located part of the city, and an ambition to shift more freight transport from road to rail and water. The overlapping of passenger and freight transport contributes to bottlenecks within the city of Hamburg. The circumvention of the city of Hamburg is seen as one of the most important ways to reduce bottlenecks in both passenger and freight traffic. The circumvention of Hamburg of freight and passenger transport depends in part on the realisation of large infrastructure projects by the federal government through the Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan 2030 (Bundesverkehrswegeplan 2030). To improve the rail network, the building of the Fehmarn Belt fixed crossing and upgrading of the rail network to South Germany are underway through the federal state. The bottleneck in Hamburg further necessitates increased accessibility toward the south and toward Northern Europe.

The construction of the fixed crossing of the Fehmarn Belt is one of the central infrastructure projects of the trans-European Scandinavian-Mediterranean Corridor. The crossing will be built in the form of a tunnel and connect the Danish island of Lolland with the German island of Fehmarn. By connecting two high value-adding metropolitan regions in the form of Scandinavian urban centres and Northern Germany, it has the potential to stimulate the development of the Fehmarn Belt region and provide opportunities for certain fields of inter-regional co-operation. Districts set to be impacted by the fixed crossing of the Fehmarn Belt are working together to develop strategies on commercial spaces, marketing, tourism and road capacity at junction points. Comprehensive and integrated planning will be needed in order to maximise the opportunities represented by the Fehmarn Belt while minimising potential negative externalities such as reduced road capacity and noise pollution.

Collaborating on a regional level

The HMR shows evidence of collaboration on a regional level in public transport and other aspects of mobility, including transport infrastructures such as road and rail. The monocentric HMR region has no joint transport strategy but is connected by 761 000 commuters daily, of which 350 000 commuters enter Hamburg daily. Many of these commuters are served by the Hamburger Verkehrsverbund, or Hamburg Public Transport Association (HVV). The HVV serves an area of 8 616 km² including the city of Hamburg and parts of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony. HVV acts as the overall co‑ordinating body for transport in the conurbation, providing a successful collaboration within the HMR. Even though transport infrastructures tangibly connect the region into a cohesive whole through the HVV, there is potential for more co-ordination between HMR actors. The fragmented tariff structure of the HMR further complicates the cohesiveness of the region as a whole. While a large part of the HMR is included in the territory covered by the transport association Hamburger Verkehrsverbund (HVV), this extends primarily to the districts immediately adjacent to the city of Hamburg. Three additional tariff associations cover the HMR: Niedersachsentarif, Schleswig-Holstein-Tarif and the tariff of the Verkehrsverbund Bremen-Niedersachsen. Moreover, the districts of Ludwigslust-Parachim, Nordwestmecklenburg and the district-free city of Schwerin are not part of any tariff scheme. The most successful example of a fully integrated tariff exists between the HVV and Schleswig-Holstein, where all tickets can be purchased for destinations within the HVV. However, this is not the case for any of the other tariffs, even though tariffs between the HVV and the transport association of Lower Saxony are partially integrated. This uneven development makes certain trips very expensive to take, and limits extended and intermodal use. For municipalities wishing to become part of the HVV, the financial contribution this entails can be prohibitive, thus creating a high barrier to entry into the transport association. However, concrete steps are being taken to expand the HVV tariff: from the end of 2019 onward, rail transport in four districts of Lower Saxony (Cuxhaven, Heidekreis, Rotenburg (Wümme) and Uelzen) will be covered within the HVV tariff on rail transport and season tickets.

Collaboration on the regional level has also taken place in the form of 5 North German Länder (Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Schleswig-Holstein) agreeing on a list of 24 urgently needed transport projects. The resulting Ahrensburger list sets out necessary, predominantly harbour-relevant traffic projects of supra-regional importance. They also include projects important for the connectivity of the HMR to other metropolitan regions in Germany such as Bremen-Oldenburg and Hannover-Braunschweig-Göttingen-Wolfsburg, including the motorway projects A20 and A39 and the optimisation of railway networks “Alpha-E”. This collaboration can be expanded on to lobby for infrastructure projects that would benefit the whole region. Furthermore, the Fehmarn Belt crossing could provide an impetus to stimulate further inter-regional collaboration with other European metropolitan regions.

Addressing mobility throughout the HMR

Co-operation among HMR actors, and potentially in a larger northern German framework, will be needed in order to build the large infrastructure projects that are already planned. Transport-oriented development along settlement axes could make better use of land value capture mechanisms to recoup some of the public investment in infrastructure. Park-and-ride and bike-and-ride services should be further expanded in areas where a demonstrated need for these exists in order to foster multimodality.

Integrate transport with housing and land use

A common regional plan for the HMR integrating transport with settlement and land use and encouraging transit-oriented development would benefit the region. Actors should also regularly elaborate priority lists of infrastructure development that would benefit the whole region. Developing housing and settlement along transport corridors or axes can be a good approach to the integration of housing and transport, but traditional infrastructure projects will not be the sole answer to demographic change, as large transport infrastructures such as highways can sometimes weaken small urban areas if alternatives to local economies are made more convenient. An integrated planning concept could focus on transit-oriented development and create strategies for places where public services are disappearing. Large infrastructure projects such as the planned highways are likely to have an important effect on mobility in the HMR. However, they will also affect other outcomes, such as housing prices and firm location choices. As many planned transport infrastructures extend across administrative boundaries, their effects on the housing and labour market will cross these boundaries too. Proactive and collaborative planning for these changes can help mitigate adverse effects and exploit the full potential of new infrastructure developments. With projects such as the Fehmarn Belt set to open the labour market even further, co-operation and co-ordination will be needed among the actors of the HMR in order to manage increased traffic and housing needs. Considering the realisation of large infrastructures as a means to increase mobility in the regional labour market rather than an end in itself can facilitate planning for their potential effects on other sectors, such as housing and land prices.

The integration of transport planning, spatial planning and economic development is crucial for sustainable regional development. It could help provide targeted relief of Hamburg through supporting medium-sized cities such as Lübeck and help keep the focus on quality of life rather than on growth. Greater integration of housing and transport can be achieved using instruments that are already partially available in the HMR. The housing and mobility calculator (Wohn‑ und Mobilitätskostenrechner, www.womorechner.de) could serve as a starting point for larger projects.

With the WoMo tool already at its disposal, the HMR could make greater use of it by creating a roadmap for municipalities and districts to use the tool in planning decisions. If this housing and mobility calculator’s potential is fully harnessed, it could encourage the construction of affordable housing in neighbourhoods with higher land costs but lower transport costs, while focusing transit investments such that the amount that remote households spend on transport is reduced (Guerra and Kirschen, 2016[33]). Thus, it should be made more accessible to individuals who may use it to make choices regarding their housing, while also being marketed to planners and policymakers in order to encourage informed and evidence-based policies for greater integration of transport and housing. It is worth considering the uses of a similar tool, the H+T (Housing and Transport) affordability index, developed by the Center for Neighborhood Technology (CNT) in the United States. The tool is specifically aimed at individuals, housing professionals, urban planners and policymakers. The CNT specifically encourages the use of the tool in policymaking and planning decisions and has prompted several successful projects in the US using the H+T index as the basis for decision-making (see Box 3.5). Packaging the WoMo tool into a toolkit with suggested uses and offering technical assistance to municipalities, districts, planning associations and other organisations wishing to integrate it into their planning process may lead to the better integration of transport and housing in places throughout the HMR. Specifically, it could be used as a pillar of a joint planning strategy for the HMR in order to select transport corridors and where to develop affordable housing.

Box 3.5. Selected applications of CNT’s H+T index

The CNT has specifically encouraged the use of its H+T index by regional and local planners, housing professionals such as public housing agencies and non-profits, and policymakers. Beyond helping individuals make informed housing decisions, this has enabled a wide variety of actors to integrate transport and housing in their plans and strategies.

In Chicago, the tool has been used by several agencies and organisations. The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) used H+T costs as a liveability measure in its comprehensive regional plan “GO TO 2040”, while the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) used data from the H+T Index in a corridor selection analysis designed to identify potential bus rapid transit routes, while balancing community goals of increased liveability, reduced travel time and lower environmental impacts.

In San Francisco, the Bay Area Transit-Oriented Affordable Housing (TOAH) Fund was established by the Metropolitan Transport Commission (MTC). This was partially due to the H+T index, which allowed to make the case for the integration of housing affordability and transport.

State of Illinois: The measure of combined housing and transport affordability was adopted into law, with bipartisan support, as a planning tool for five agencies and as a consideration for those agencies’ investment decisions in metro areas. The economic development, transport and housing agencies can use H+T to screen and prioritise public investments in metro areas, while the two financing agencies will recommend the use of the index for new siting decisions.

El Paso, Texas: The City Council directed the City Manager to use the H+T Index for affordability determinations, to initiate the use of the index as a tool to benchmark costs and to adopt a 50% H+T affordability standard for all city funding and policy decisions.

Source: CNT (n.d.[34]), H+T® Index: Applications for Use, https://htaindex.cnt.org/applications/.

Harmonise tariff schemes across the region

Actors across the HMR should make efforts to harmonise public transport and park-and-ride tariff schemes across the whole region and integrate last-mile transportation schemes within these. Although people commute across the HMR on a daily basis, the HMR comprises different tariff zones and structures that are only integrated to a varying degree. At the moment, the HVV (Hamburger Verkehrsbund) comprises seven administrative districts spread over three states. The HVV has expanded several times in the past and continues to envision further expansion, currently planned for the year 2020. The financial costs associated with membership constrain the possibility of expansion to some districts, but tariff co‑operations (Übergangstarife) may be used in these cases. While an expansion of the HVV to the entire HMR is not a necessity, there should be a concerted effort to integrate the tariff structures of different transport associations within the HMR to create a single HMR tariff or make the transition between tariff zones as smooth as possible. This would decrease the friction with which residents must now contend in their commutes while also serving as a marker of shared identity to residents and visitors alike. Integrating last-mile transport and on-demand mobility services into a general tariff for the metropolitan region could increase the number of users and reduce the cost of overlapping tariff schemes for residents of the peripheral HMR. These services will have to make special efforts to attract those who now drive their own car to use their services, instead of merely shifting passengers from other public transport services to new mobility services. The Switchh platform in the city of Hamburg is attempting to increase multimodality by simplifying the switch between public transport, taxis, rental cars and/or bicycles on flexible and short-term notice. Harmonising park-and-ride facilities by instituting a common concept can also promote multimodality.

Harness digitalisation to ensure service provision in peripheral and ageing areas

Municipalities and districts could benefit from using innovative methods, including digital instruments and public-private partnerships, to ensure mobility in rural areas. Flexible Bedienformen, or on-demand mobility services, have the potential to reach HMR residents throughout the whole region and improve accessibility in peripheral areas. Mobility services can also harness digitalisation to improve the accessibility of rural areas to jobs and services. One example can be found in the city of Lauenburg (Schleswig-Holstein), which is located 40 km outside of Hamburg and serves as a testing ground for innovative mobility solutions for rural areas. It is currently co‑operating with the Technical University of Hamburg to implement a fully autonomous public bus transport system. Other ways to improve rural residents’ mobility is the introduction of car sharing projects in villages, such as the project Dörfliches Carsharing im Wendland. Innovative mobility services can also serve to increase inter- and multimodality in peripheral areas of the HMR by connecting residents to other modes of transport. Bike-and-ride stations are now mandatory at every S-Bahn stop and park-and-ride services are set to be expanded upon. Digital solutions could build on these built infrastructures. The upcoming Intelligent Transport System World Congress in 2021 has also stimulated the discussion around new forms of mobility, while innovative mobility solutions using online-based tools for shared buses and taxis have been implemented in some parts of the HMR. One such service is ioki, a subsidiary of Deutsche Bahn based in Frankfurt which provides, among other services, a ridesharing service in parts of the Hamburg area (though not the whole HMR) that is tightly integrated with public transport and the HVV tariff structure. Another example is MOIA, a subsidiary of Volkswagen. Its focus is on the development of app-based, on-demand offerings, including ride-hailing and ride-pooling services. Its services are currently offered in central Hamburg and will be gradually expanded to the outskirts of the city. A third example is Clever Shuttle, another ride-pooling shuttle service using digital technologies to bundle passengers with similar destinations. It has been in service in Hamburg with hydrogen-powered vehicles since 2017. By using digital tools and services to close the gap between public transport and first- and last-mile transport, there is a large potential to enable mobility without the need for car ownership, even areas lesser-served by public transport.

Leveraging the HMR’s potential to advance environmental sustainability

Environmental sustainability can take different forms in the HMR, as it should be integrated into a holistic approach with housing and transport, yet also involves spatial planning through green spaces. Externalities generated by one local government in one of these sectors can adversely affect natural assets in other municipalities, districts or federal states. Co-operation between actors can thus seek to address these negative externalities and avoid them negatively impacting natural assets while maximising the positive impact they can have. Ensuring energy efficiency in the sectors of housing and transport has the potential to reconfigure the relationship between the urban core and rural periphery, with the rural areas as providers of sustainable energy and the core city as consumers. Sustainably managing green spaces and nature reserves can improve residents’ quality of life, the attractiveness of the region for visitors and workers, and the sustainability of the region for the future.

Improving environmental sustainability by protecting natural assets and harnessing the potential of renewable energy production

Protecting green space and biodiversity

The HMR can build improve its environmental sustainability and attractiveness by protecting its many notable natural assets and green spaces. In particular, it can build its sustainability by strengthening and expanding its biosphere reserves. There are currently five United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) biosphere reserves in the HMR region, with further municipalities attempting to become part of one of them. Applications are made through the federal government but approval has to be given by all mayors in the region. There are reservations at the communal level, as these are wary of creating obstacles to further development of infrastructures such as housing. However, biosphere reserves could play a key role in bolstering strategies for development and differentiation within the region. They can have several distinct roles and functions, including an ecological one to combat climate change and preserve biodiversity, a role in sustainable regional development to sustain recreational and green areas, and a potential role in research and education. The protection of species and the maintenance of habitats will require co-operation between actors at all levels across administrative boundaries as sites must be linked through corridors. The Biotopverbund project (Habitat Network Hamburg Metropolitan Region) of the HMR has laid the groundwork for further co-operation by making all relevant plans available digitally, consolidating them in a general map and initiating communication among responsible authorities across administrative borders. Additionally, the project has improved the habitat network by (re)connecting or upgrading a number of biotopes, including across Länder (e.g. between Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein and between Lower Saxony and Mecklenburg-Western-Pomerania).