This chapter introduces the concept of child vulnerability and the factors that contribute to it. If offers an analytical framework for overcoming it. This framework looks at the factors contributing to vulnerability and seeks to integrate resilience building into the design of policies. The chapter summarises the relationship between vulnerability and low child well-being, and the case for strengthening children’s resilience. Finally, it outlines a set of recommendations through which OECD countries can develop child well-being strategies with a particular focus on vulnerable children, organised around six key policy areas.

Changing the Odds for Vulnerable Children

1. What is child vulnerability and how can it be overcome?

Abstract

Introduction

Over the past three decades, growing inequalities in OECD countries have exacerbated the challenges faced by society’s most vulnerable groups. Children in particular are suffering the consequences. This report positions investing in the well-being of vulnerable children as a central action for inclusive growth, in line with the recommendation of the OECD Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth to invest in people and places that have been left behind (Box 1).

The OECD has defined child well-being in terms of a number of life dimensions that matter for children, now and in the future.1 This report builds upon the OECD’s understanding by focusing on vulnerable children as a group with the lowest levels of well-being and worthy of the greatest investment. It introduces an analytical framework that looks at the individual and environmental factors that contribute to child vulnerability, as well as the application of resilience-building into policy design.

This report recommends that OECD countries develop cross-cutting well-being strategies with a focus on vulnerable children, in order to build their resilience to overcome the range of adversities experienced from an early age. Investing in vulnerable children is not only an investment in disadvantaged individuals, families and communities, it is an investment in more resilient societies and inclusive economies.

Box 1.1. Opportunities for All: A Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth

In 2018, the OECD Inclusive Growth Initiative launched the Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth to help countries sustain and ensure a more equitable distribution of the benefits from economic growth. The Framework is supported by a dashboard of indictors and consolidates key OECD policy recommendations into three areas for action:

1. Invest in people and places that have been left behind through (i) targeted quality childcare, early education and life-long acquisition of skills; (ii) effective access to quality health care, justice, housing and infrastructures; and (iii) optimal natural resource management for sustainable growth.

2. Support business dynamism and inclusive labour markets through (i) broad-based innovation and technology diffusion; (ii) strong competition and vibrant entrepreneurship; (ii) access to good quality jobs, especially for women and under-represented groups; and (iv) enhanced resilience and adaptation to the future of work.

3. Build efficient and responsive governments through (i) aligned policy packages across the whole of government; (ii) integration of distributional aspects upfront in the design of policy; and (iii) assessing policies for their impact on inclusiveness and growth.

Source: (OECD, 2018[1]) Opportunities for All: A Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth.

What is child vulnerability?

The concept of child vulnerability is frequently referred to in child development and children’s rights literature; but is neither well defined nor analysed (Schweiger, 2019[2]; Jopling and Vincent, 2016[3]; Brown, 2011[4]).

Child vulnerability is the outcome of the interaction of a range of individual and environmental factors that compound dynamically over time. Types and degrees of child vulnerability vary as these factors change and evolve. Age, for example, shapes children’s needs while also exposing them to potential new risks. Infants, who are completely dependent and require responsive and predictable caregiving, are particularly sensitive to parents’ health and material deprivation. Young children under three years old are especially affected by family stress and material deprivation because of the rapid pace of early brain development. Young children can benefit from early childcare and education (ECEC) interventions and time away from the home environment. The independence of older adolescents makes them more susceptible to opportunities and risks in the community, making the presence of supportive adults, school quality, and local economic opportunities important for well-being.

The special vulnerability of children is recognised by the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which underlines the need to extend special care and protection to children on grounds of physical and mental immaturity. The UNCRC stipulates governments’ responsibility to take protective and preventative measures against all forms of child maltreatment, and to support parents in meeting child‑rearing responsibilities through the development of institutions, facilities and services. OECD and non-OECD countries provide for the special vulnerability of children through specific legalisation and policies across education, health, labour regulations, juvenile justice and child protection, though specific approaches vary according to countries’ traditions and definitions of the issue.

Factors contributing to child vulnerability

Individual factors contributing to child vulnerability stem from cognitive, emotional and physical capabilities or personal circumstances, for instance age, disability, a child’s own disposition or mental health difficulties. They can be invariable, such as belonging to an ethnic minority or having an immigrant background, or situational, such as experiencing maltreatment, being an unaccompanied minor or placed in out-of- home care. Chapter 2 provides a more detailed analysis of the following individual factors.

Disability

Children with disabilities are a very broad group with varying capabilities and needs whose individual functioning is limited by physical, intellectual, communication and sensory impairments and various chronic conditions. Though the outlook for children with disabilities has improved considerably over the last few decades, they are still overrepresented in institutional care settings and more likely to experience maltreatment, particularly neglect. Compared to non-disabled peers, children with disabilities are more likely to live in in low socio-economic households and to be bullied.

Mental health difficulties

Evidence suggests that childhood mental health difficulties are becoming more common. Some OECD countries, for example England (United Kingdom), have recorded a gradual increase over the last 20 years. Potential explanations are better detection and increased interest in emotional well-being and help‑seeking behaviours. High academic pressures and weakening of family and support units also play a part.

Inequality contributes to pronounced differences in children’s mental health. Children from low socio-economic backgrounds are two to three times more likely to develop mental difficulties than those from high socio-economic backgrounds; material deprivation. Perceived inferior social status and a stronger parent-child transmission are factors. Highly educated parents are more able to access timely and specialist support for children.

Immigrant background

Children with immigrant backgrounds are a large and growing group. Factors such as parents with lower educational attainment and fewer economic resources in the household can affect their ability to succeed in or complete school. These children also tend to have fewer social networks established in their host country, speak a language at home that differs from the one spoken at school, and are more mobile than students without an immigrant background. On average, across the OECD, native-born students perform better academically; the gap between children with immigrant background is largest among children who arrive after age 12.

Unaccompanied minors face particular integration challenges. Most arrive just before or after the age of compulsory schooling and have little or no formal education. The challenges are greatest for those without a guardian to provide emotional, financial, social and practical support.

Maltreatment

Environmental risk factors for maltreatment include poverty, living in a poor neighbourhood, overcrowded housing, intimate partner violence and parental substance misuse. Child factors include disability and poor child-parent attachment. Identifying children at risk is difficult, as many children exposed to similar risks are not maltreated.

Maltreatment has long and enduring economic consequences for individuals and society. Adult who were maltreated are more likely to have lower levels of educational attainment, to earn less and own fewer assets. Maltreatment negatively predicts poor adult mental health and convictions for non-violent crime.

Out-of-home care

Children in out-of-home care are a particularly vulnerable group. Child protection systems in OECD countries operate quite differently, shaping the numbers of children entering and leaving the care system. These differences are linked to countries’ social, political and cultural contexts, legislative and policy frameworks, child protection system resources and constraints, and child protection workers’ training and decision-making.

The outcomes for children in out-of-home care are lower than for the general population, across education, health, adult employment and future earnings. There are opportunities to help these children catch up, for example by providing care placements with well-supported foster carers. Support for young adults ageing out of the care system can be critical for eventual labour market participation.

Environmental factors contributing to child vulnerability operate at both family and community levels. Family factors include income poverty and material deprivation, parents’ health and health behaviours, parents’ education level, family stress and exposure to intimate partner violence. Community factors are associated with school and neighbourhood environments. Environmental factors illustrate the inter-generational aspect of child vulnerability and the concentration of vulnerable children within certain families and communities. Chapter 3 provides a more detailed analysis of the following environmental factors.

Material deprivation

Children are overrepresented in income-poor households. In OECD countries, on average, one in seven children lives in income poverty. The poverty risk varies by family type and parent’s employment status; it is six times higher in families with no working-parent than families with at least one working-parent, and three times higher for single-parent families.

Material deprivation is strongly linked to income poverty. OECD measures material deprivation across seven dimensions: nutrition, clothing, educational materials, housing conditions, social environment, leisure opportunities and social opportunities. One in six children in European OECD countries experiences severe deprivation, measured as being deprived in four dimensions. In a number of countries, sub-groups of children are deprived across all seven.

Family homelessness is growing by significant levels in some OECD countries, for example England (United Kingdom), Ireland, New Zealand and some US states. Children in homeless families are much more likely to suffer from low well-being. Homelessness imposes on children a difficult set of stressors and adversities including poor diet and missing meals, increased anxiety, loss of independence, overcrowded living conditions and lack of privacy, repeated accommodation moves, loss of parental care if accommodated separately, loss of contact and support from family and friends, school placement disruption, and stigmatisation.

Parents’ health and health behaviours

Childhood conditions have a lifelong impact on health: 6% of poor health at age 50 is associated with poor health at age 10, controlling for adult socio-demographic factors. Parents transmit risk factors for poor health to children, including genetic predispositions and poor health behaviours. High socio-economic status moderates certain genetic risk, for example smoking, and can influence gene variants that predict higher educational attainment. Epigenetics also shows that stressful early life experiences and exposure to environmental toxins can affect gene expression and long-term outcomes.

Parents’ education level

Parents’ level of education strongly influences children’s educational achievements. Across the OECD, the likelihood of attaining a tertiary education is over 60% for those with at least one parent who has a tertiary education. The likelihood of attaining children only the level of education of their parents corresponds to 41% and 42% for those whose parents have upper secondary and below upper secondary, respectively. The OECD PIACC survey highlights the influence of parents’ education on adult literacy and numeracy skills levels: 25% of adults whose parents had less than an upper secondary education achieved the lowest scores compared to only 5% of those whose parents had a tertiary education.

The OECD PIACC survey shows that individuals from advantaged family backgrounds are more likely to be highly educated than cognitive skills assessments would suggest: 4.5% of adults with low numeracy test scores have a tertiary education, just as their parents before them. This suggests that parents’ levels of education and income help children succeed regardless of ability and skills, as children benefit from many opportunities to overcome shortcomings and accumulate skills valued by the labour market.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

IPV significantly influences child well-being. Exposure to IPV during pregnancy is associated with low birth weight and pre-term delivery, after controlling for socio-economic and other factors. In early childhood, it can have long-term consequences on social and emotional development. There is a strong co-occurrence of IPV and child maltreatment.

There is no available OECD-wide data on the numbers of children exposed to IPV. Some country‑level studies based on children’s exposure to violence or women’s reports of IPV suggest that the numbers are significant. Overall, households with IPV are twice as likely to contain children, particularly under five years old.

Family Stress

Family stress is caused by the co-occurring factors that contribute to child vulnerability. The manner in which children learn to respond to stress is shaped by individual traits and the risks and protective factors in their environment. Children’s stress responses can become excessive and prolonged without adequate support from a supportive adult. The presence of chronic stress in early childhood is serious and contributes to health and emotional and behaviour difficulties. It weakens the foundation of the brain architecture, causes epigenetic adaptions, disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical and compromises the immune system.

Schools

Early childhood care and education (ECEC)

Estimates suggest that the economic returns of investment in early learning, including higher adult earnings, better health across the life-cycle and lower crime, are between 2% and 13% per annum. A number of studies suggest that children from lower socio-economic status families experience particular benefits in the areas of cognitive and social skills development compared to peers from higher socio-economic backgrounds. Participation in ECEC can influence parents to engage more frequently in cognitively stimulating and less passive activities with their children, helping to close the gap between disadvantaged children and children from non-disadvantaged families. Yet children from low socio-economic backgrounds access ECEC at much lower rates, in some countries up to half.

Participation in ECEC is beneficial for children who speak a different language at home than the one spoken in school. PISA 2015 shows that immigrant students who attended ECEC for at least one year scored 36 points higher in the science assessment domain. After accounting for student economic status, this gap remained significant at 25 score-points (i.e. ten months of formal schooling).

Primary and secondary education

PISA 2015 shows that across OECD countries disadvantaged students performed worse than advantaged students across all assessment domains. For example, for mathematics test scores, school effects are the most important explanatory factor (33%) followed by family background (14%), student characteristics (11%) and school policy effects (8%). School effects include the sorting of students of similar ability or background into the same schools. In all countries, there are clear advantages to attending a school where students, on average, come from more advantaged backgrounds.

The aspirations and self-expectations of disadvantaged students can be raised by attending the same school as advantaged students. PISA 2015 shows that children of blue-collar workers who attend schools alongside children of white-collar workers are around twice as likely to expect to earn a university degree and work in a management or professional occupation compared to children of blue-collar workers who perform similarly but attend other schools. The clustering of poor students in poor schools can have the effect of dampening students’ expectations and beliefs in themselves.

Neighbourhoods

Neighbourhoods have a causal effect on child and later adult outcomes, distinct from family factors. Neighbourhoods vary in the opportunities available for children to do well; some have supportive mechanisms in place that enhance child development, while others have too many stressors and not enough protective factors. Neighbourhoods can increase the difficulties experienced by families through concentrated poverty, social isolation and joblessness.

Neighbourhoods can be high-opportunity places for low-income children to grow up in. High‑opportunity neighbourhoods improve the likelihood of social mobility by transmitting advantages that favour human capital development, such as good schools, more adults in employment, and lower spatial segregation and crime. Several studies looking at the benefits for children and adolescents of moving to a high-opportunity neighbourhood point to positive place exposure effects that are cumulative and linear.

Building resilience to overcome child vulnerability

Child vulnerability is not caused by a single contributing factor, but the interaction of several over time. For instance, children living in income poverty may also live in high-poverty neighbourhoods that lack social capital and social cohesion (Wikle, 2018[5]). In addition to housing insecurity, homeless children encounter other stressors such as poor parental mental health and family separation (Radcliff et al., 2019[6]). Intimate partner violence can be more harmful to young children because of the critical stage of their development, high level of dependence and high concentration of time spent in the home environment (Schnurr and Lohman, 2013[7]). Low household income can compound the barriers faced by children with disabilities to performing well in school (Sentenac et al., 2019[8]). Maltreatment is present in all socio-economic groups, but children from low‑income families are more exposed due to lack protective factors such as adequate living space, access to high-quality education and childcare, and good social and family support (Ellenbogen, Klein and Wekerle, 2014[9]). The interaction of factors mediating child vulnerability calls for an across-childhood approach to well-being.

The framework introduced in this report applies the concept of building resilience to policy design in order to improve the well-being of vulnerable children. In general, children are identified as resilient if they succeed in spite of significant adversity and stress. Resilience is a dynamic process, not a fixed characteristic of a child. Therefore, resilience can be built upon (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2016[10]; Ungar, Ghazinour and Richter, 2013[11]). Building resilience requires reducing the number of risks and increasing the number of protective factors in a child’s world.

Box 1.2. Brief review of the literature on resilience

Since the 1970s a rich literature has developed on the resilience of children who experience significant adversity. Children’s ability to be resilient is attributed to possessing certain strengths and the presence of protective factors (Zolkoski and Bullock, 2012[12]). The single most common protective factor shared by resilient children is the support of one stable and committed relationship with an adult, be it a parent, caregiver or other adult (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2015[13]).

Resilience has been studied across an array of child outcomes and sub-populations: high educational attainment of students from low socio-economic backgrounds (OECD, 2011[14]); high life satisfaction, social integration and low academic anxiety of students from low socio-economic backgrounds (OECD, 2018[15]); baseline academic proficiency, school connectedness and high life satisfaction of students from immigrant backgrounds (OECD., 2018[16]); and resilience functioning among maltreated children (Cicchetti, 2013[17]). The common thread in these studies is that resilient children beat the odds and manage to have good and robust well-being outcomes over the longer term.

Risk factors prevalent in the lives of vulnerable children increase the likelihood of negative outcomes in childhood and later in adulthood. They disrupt healthy child development, family functioning and community prosperity. Risk factors include lack of a healthy diet, poor quality housing, limited access to leisure activities, limited parental understanding of child development and children’s needs, negative parental health behaviours, the absence of supportive adults, and high neighbourhood crime, among others.

Protective factors mitigate risk and reduce negative outcomes. They allow children to benefit from positive experiences, form key capabilities and access resources in favour of good outcomes. Over time, the cumulative impact of protective factors makes it easier for children to achieve positive outcomes. Protective factors include a child’s disposition, such as temperament and ability to adapt to stress, and good social and emotional skills, as these help children respond to or avoid adversity. Protective factors are present in the family and community; some are embedded in relationships children have with adult family members, schoolteachers and other adult role models, and others through local resources such as access to quality health care, effective schools and neighbourhoods, and strong child protection systems (VicHealth, 2015[18]).

Efforts to build resilience interventions should be targeted to where they can be most effective. Research suggests that enhancing the quality of the environment and making resources to nurture and sustain well‑being available are very important for children experiencing high levels of adversity (Ungar, Ghazinour and Richter, 2013[11]). This makes reducing risks such as inequalities and hazards at the environmental level critical. Generating more resilience in children is the culmination of stronger support systems, better opportunities, secure child-parent attachment, high self-efficacy and optimism and adequate economic resources (Southwick et al., 2014[19]).

Towards child well-being strategies

This report recommends that OECD countries approach improving the well-being of children through cross‑cutting child well-being strategies with a particular focus on vulnerable children, and deliver policies that develop these children’s capacities to be resilient. The value of a strategic approach is that in considering the different dimensions of child well-being, synergies, trade-offs and unintended consequences of policy actions can be identified in principle. A strategic approach also increases accountability and aligns effort and investment to make the greatest impact.

Vulnerable children need consistent, coherent and coordinated support throughout childhood. In most OECD countries, child policies are developed in silos without adequate consideration of how the range of factors shaping child well-being interact, for instance the effect of poor mental health on school performance and engagement, or poor housing quality on children’s health and family relationships. Disparate approaches that focus on single aspects of well-being are unlikely to be effective if they do not address other barriers to healthy child development (OECD, 2015[20]).

A whole-of-government approach to child policy is required for the development and implementation of child well-being strategies. Such an approach embeds horizontal co-ordination and integration into policy design and implementation processes to strengthen responses to complex issues. It allows the required consideration of the inter-connection between policy areas. For instance, mental health policy interacts with education policy when schools operate programmes to support students with emerging mental health difficulties. A whole-of-government approach is effective at resetting systems that have moved into sector‑based silos and have poor co-ordination and cooperation. It also requires that one ministry or a stand-alone agency take responsibility for coordinating the strategy and ensuring overall accountability (OECD, 2011[21]).

The well-being of society is most improved when investments are made in children. An analysis of 133 significant policy changes in the United States over the past fifty years shows that public investment during childhood has the strongest returns over any part of the life course. Direct investments in low‑income children’s health and education generate the highest pay-offs, many paying for themselves in the long run through increased tax revenue and lower social transfers. This potential does not decline as children get older. Moreover, returns on adult investment can be higher when there are positive spillover effects on children (Hendren and Sprung-Keyser, 2019[22]).

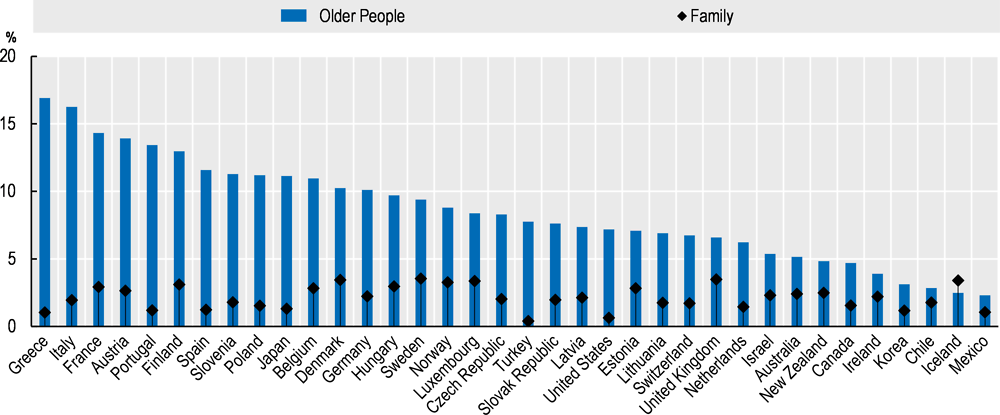

Investing in vulnerable children is most effective when it happens across the life-cycle. The factors determining the level of investment needed differs by the country context. In some cases, it may mean spending more (greater investment). In OECD countries overall, the share of public expenditure on families with children is much lower than that on older people (Figure 1.1). In other cases, it may mean redirecting expenditure (better investment) into areas that improve value for money. Interventions that substantially enrich the early learning environment are important for closing gaps that emerge early in life. However, if maximum benefits for children and economies are to be realised, early investments should be followed by later investments (Heckman, 2008[23]).

Figure 1.1. A much smaller share of public expenditure is allocated to families

Note: Data refer to cash and services expenditure.

Source: OECD, Social Expenditure Database (SOCX, www.oecd.org/els/social/expenditure).

Policies that build resilience in vulnerable children

This report puts forward six areas of policy action around which child well-being strategies could be organised: empowering vulnerable families; strengthening children’s emotional and social skills; strengthening child protection; improving children’s educational outcomes; improving children’s health; and reducing child poverty and material deprivation. New Zealand is one example of a country that is starting to implement a child well-being strategy close to this set of policy actions (Box 1.3.). These policies build resilience in children by reducing the barriers to healthy child development and well-being (risk factors) and increasing opportunities and resources (protective factors).

Box 1.3. New Zealand Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy

New Zealand’s first Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy was launched in August 2019. The Strategy sets out a shared understanding of what young New Zealanders want and need for good wellbeing, what government is doing and how others can help.

The strategy was developed with input from 10,000 people – including over 6000 children and young people, who shared what makes for a good life and what gets in the way. It also draws on the best evidence from social science and cultural wellbeing frameworks.

Led by the Prime Minister, the Minister for Children and a newly established Child Wellbeing Unit, the work is underpinned by new child wellbeing and poverty reduction legislation which ensures ongoing political accountability for reducing child poverty and requires successive governments to develop and publish a strategy to improve the wellbeing of all children, with a particular focus on those with greater needs.

The newly published Strategy provides a unifying framework and way of aligning efforts across government and with other sectors. It includes an aspirational vision, nine guiding principles, and six wellbeing outcomes that outline what children and young people want and need for a good life.

The current Programme of Action that accompanies the Strategy brings together 75 actions and 49 supporting actions led by 20 government agencies. While the Strategy is aimed at improving the wellbeing outcomes for all young New Zealanders under 25 years old, it also reflects the strong call to urgently reduce the current inequity of outcomes.

The Government has prioritised the wellbeing of children and young people who are living in poverty and disadvantaged circumstances, and those with greatest needs, including children and young people of interest to Oranga Tamariki (New Zealand’s child protection and youth justice agency). This involves work to address child poverty, family violence, and inadequate housing, and improving early years, learning support and mental wellbeing for children, young people and their families.

A set of indicators has been established to help inform an annual report to Parliament on achievement of the outcomes. The legislation also requires that the Strategy be reviewed at least every three years, to ensure it continues to address the issues and challenges facing New Zealand’s children and young people.

Many of the issues facing children, young people and their families are complex, stubborn and inter-generational, so change will take time. It will also require a unified response, so the Strategy seeks to support, encourage and mobilise action by others, and empower and enable people and communities to drive the solutions that work for them.

Note: For more information go to www.childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz.

Source: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, New Zealand Government.

Empower vulnerable families

Parenting Support. Vulnerable families benefit from access to a range of services to reduce stressors and build protective factors. Family based interventions, such as home visiting programmes, improve children’s home environment by helping parents enhance parenting skills, learn more about child development and access local resources. Parenting programmes, delivered in group settings tailored to different age-groups, can help parents work alongside each other to gain a better understanding of children’s needs and learn more effective and consistent parenting approaches. An example is the Incredible Years programme, which has been ran in a number of OECD countries and there is evidence of its effectiveness on positive child behavioural changes and improved family relationships.

Policies that take a whole-family approach. Working with different family members has the potential to reduce family-level risk factors and build protective factors. Taking a whole-family approach to working with men who perpetrate intimate partner violence (IPV), for example, can reduce reported incidences of IPV and improve children’s sense of safety.

Neighbourhood based programmes. Neighbourhoods can be a resource for vulnerable families. Neighbourhood based programmes can take a whole-community approach to early intervention and prevention and develop services that address families’ multiple needs, for example parenting support, childcare and employment advice. Whole-community approaches can reduce the stigmatisation attached to accessing support and build neighbourhood collective efficacy to improve child well-being. Australia and the United Kingdom have experience over the past decade in applying this approach to work with the most vulnerable families.

Emotional and social well-being

Schools play a key role in supporting children’s social and emotional well-being, and identifying and assisting children who need support. Many countries are integrating emotional and social skills development into the national and subnational curricula. Some countries, for example France, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Koran and Scotland (United Kingdom), have gone a step further by developing emotional well-being frameworks that integrate health services and strengthening protective factors in the school environment.

Children need to be able to access mental health information and interventions more easily, at the school and neighbourhood level. Schools can build stronger relationships and collaborations with local mental health professionals, including psychologists and social workers and cultural mediators. Early intervention and open to all services should be accessible in communities to target children with emerging and mild to moderate mental health difficulties. E-counselling can fill in gaps as it is accessible for longer hours and has a broad geographical reach.

Clear policies need to be in place to support young people through the critical transition onto adult mental health services. These policies need to be centred on the young person’s needs, incorporate the inclusion of young people and families in care planning, and provide clear transitions guidelines. The United Kingdom has issued working guidelines on supporting the planned transition of young people onto adult services.

Adolescent mentoring programmes. Vulnerable adolescents exposed to high environmental risks and/or behavioural problems benefit from having the opportunity to build relationships with supportive adults and role models. Some of the best-known programmes are Big Brother Big Sister of America (United States) and Youth Advocate Programme (Ireland, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

Vulnerable children need to be provided with the same opportunities as peers to participate in leisure activities. Leisure activities provide children opportunities to engage in developmental appropriate tasks and build relationships with supportive adults. This has benefits for the development of social and emotional skills, and educational outcomes.

Schools and the broader community are important stakeholders in building children’s digital resilience and digital skills. Professional development programmes need to prepare teachers and schools to educate students on online safety and privacy. Integrating online safety or digital citizenship responsibilities in the curriculum is an option. Beyond schools, policy makers should better measure and monitor existing policies and countries should consider co-ordinated regulatory responses to children protection.

Child protection

Child protection services should be accessible to children and families in need. The key tenets of child protection legalisation and policies in the OECD include safeguarding children from maltreatment, promoting children’s best interests and family preservation. Child protection services in OECD countries generally fall between “child protection systems”, for instance in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, and “family welfare systems” as in Denmark, Finland and Norway. Some countries have made efforts to become more accessible and provide more appropriate responses by adopting the differential response (DR) model, for example Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and the United States. An overarching aim of DR is to facilitate a more nuanced approach to working with vulnerable families and to extend access to services to lower-risk families and to families who voluntarily accept help.

To enhance the well-being of children placed in out-of-home care, greater investments is needed in resources to build protective factors in those systems. Overall, better outcomes for children in out-of-home care are associated with reception into care at a younger age, minimal care and school placement disruptions, placement in kinship or foster care, maintenance of positive contact with birth family, and the continued support of an adult after ageing out of the care system.

Aftercare policies to support young people ageing out of the care system. In recent years, some OECD countries have strengthened access to aftercare services, for example France, Ireland and Scotland (United Kingdom). The quality of out-of-home care and the opportunities provided to build human and social capital influence the level of support young care leavers need. Young care leavers may need assistance with matters that other young people can rely on their family for, such as advice and support, and help securing accommodation and employment, and attending medical appointments. They also need reliable contact with positive role models.

Education

Participation in early childcare and education (ECEC) can be an important protective factor in the lives of vulnerable children. A number of countries have defined education policies specifically to increase children from lower socio-economic backgrounds, for instance the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom (Scotland). In Norway, preliminary evidence shows increased participation in ECEC among minority-language children by 15%, leading to better results on mapping tests in the first and second grade compared to areas with no intervention.

Ensuring the quality of ECEC is fundamental for maximising the benefits for vulnerable children. High quality childcare is associated more positively with school readiness and language skills for low-income 3 year-olds than children from non-disadvantaged families. Yet greater positive benefits for children from low-income families are not consistently found, but this could be explained by the fact that children from lower-income families are less likely to benefit from the highest quality of care.

Building teacher capacity to detect individual students’ needs, particularly in diverse classroom settings, can help close the well-being gap. This could be done by providing schools with inputs such as specialised teacher support and training to identify students at risk and to foster self-esteem and positive attitudes.

Polices should address the concentration of disadvantaged students in schools and adopt proactive measure to prevent further educational segregation. This involves counteracting residential segregation and the greater sorting of children by academic ability and socio-economic status. In addition, addressing the practical barriers to accessing certain schools such as tuition costs and availability of public transport is important.

Preventing early school leaving and youth unemployment requires intensive and targeted support at groups of young people most at risk. Policies need to ensure that school disengagement is detected early for young people to receive the support the need. In Sweden, for instance, municipalities are required to report to the national education authority every six months to report on interventions tried to help engage young people in education. In Norway, school have the flexibility to exempt teachers from teaching commitments to work directly with students and parents on the factors driving school disengagement. Extra-circular activities delivered through well deigned after school programmes can contribute to young people’s social and emotional development, and keep them engaged in school. Empirical evidence suggests that positive effect of extra-curricular on schooling outcomes and careers prospects and these benefits tend to be largest for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Quality vocational education and training (VET) can help smooth school-to-work transitions. Yet, on average, slightly less than half of upper-secondary students in the OECD follow a VET courses, although proportions vary considerably between countries. Apprenticeships may also be effective against early school leaving as they appeal to more practically-minded young people who may lack the aptitude for further classroom-based learning, and reduce incentives to leave school for paid work. There is renewed interest in apprenticeship training due to the positive results produced by apprenticeship programmes – in particular favourable youth labour market outcomes- in countries with a tradition of strong apprenticeship systems like Austria, Germany and Switzerland.

Responding to the different set of vulnerabilities linked to migrant displacement can support the integration of students with immigration background. Education systems play important roles in providing students with learning opportunities and promoting overall well-being, and this can be enhance through partnerships with collaborations amongst schools, universities and community-based services. Unaccompanied minors and later arrivals with limited schooling can benefit from targeted educational programmes. On example in Germany is the SchlaU-Schule programme, which supports students in securing a school diploma through specially adapted programmes and later first workplace experiences through internships.

Many immigrant children have lower socio-economic status and attend schools in disadvantaged classrooms. This can amplify difference in academic performance and overall student well-being. Reviewing resource allocations to provide greater support to disadvantaged students and schools can help overcome some of the socio-economic barriers facing immigrant students.

Health

Broadening access to health insurance and family-planning services is effective in improving neo‑natal outcomes. In the United States, expansion of Medicaid in the 1980s increased health insurance coverage for pregnant women and reduced the numbers of low-birth weight babies and infant mortality. Better access to family planning lowers the risk of low-birth weight, pre-term birth and small size for gestational age by reducing incidences of unplanned pregnancies and better spacing of pregnancies.

Access to adequate health care from an early age facilitates early intervention and saves on future costs. Some vulnerable families face barriers in accessing preventative health care, for instance limited access to transport, other family and social priorities, poor understanding of need, and in the case of children in out-of-home care difficulties in gaining parental medical consent. Addressing these barriers is vital. Food and nutrition programmes can address malnutrition and poor nutrition, especially for families who experience food insecurity. The United States has substantial experience in nutrition assistance programmes, including Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), whose benefits are linked to better neo-natal health, and children’s cognitive development and educational achievements.

Routine pre-natal care should screen for individual and family factors that have potential to impact on neo-natal health and parents’ ability to meet the needs of new-born babies, for instance intimate partner violence, and parental drug and alcohol use. Support and advice on making positive health behaviour changes should be targeted better at specific groups for whom harmful health behaviours are more common, for instance smoking among young women and those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds and ethnic groups.

Paid family leave promotes good maternal health and child health and developmental outcomes. Paid parental leave is associated with reduced maternal stress and improved mother’s life satisfaction during early infancy, and some evidence suggest positive effects into the long-term. On child well‑being, the evidence is more mixed. Nonetheless, in Australia, longitudinal data has linked paid leave, if the duration of leave is at least 6 weeks, to reduced incidences of childhood asthmas and bronchitis and to significantly increased breast-feeding uptake.

Child poverty and material deprivation

OECD analysis suggests that a broad reduction in child poverty can only be achieved through the following actions: increasing parental employment and the quality of jobs, supporting maternal employment as well as a stronger redistributive system. Tax and benefit systems can be designed to make work pay by providing first and second earners in two-parent families equal incentives to work. Maternal employment can be supported by access to affordable all-day childcare. In addition, more intensive job placement support and opportunities to build skills to access better quality jobs, particularly for parents whose health status, family circumstance or low skill levels keep them out of the labour market.

Social expenditure seems to have the strongest effect on child poverty when it is earmarked to low‑income households. This association can be strongest when the 10% poorest households receive a higher share of total spending. Countries could decide to intensify the support given, by either increasing spending or by reallocating family cash benefits, or both. How the greatest reduction in child poverty is achieved varies across countries. In some countries, the redistribution of family allowances could be very effective, while in others, improving the distribution of housing benefits.

Families benefit from adequate social benefits to help meet the additional care needs of children with disabilities. Caring for a child with a disability restricts parents’ capacity to work outside of the home and/or to take up better-paid employment. Definitions and assessment procedures of disability differ across countries. In general, payment rates vary by the level of impairment, child’s age, family status and income. For example, children with disabilities in single-parent families in Australia and Portugal are entitled to higher allowances than two-parent families. In some countries, parents may receive a supplementary payment, a carer’s allowance, for taking full-time care of their children.

References

[4] Brown, K. (2011), “‘Vulnerability’: Handle with care”, Ethics and Social Welfare, Vol. 5/3, pp. 313-321, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2011.597165.

[10] Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2016), From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts, http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu (accessed on 23 May 2019).

[13] Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2015), In Brief: The Science of Resilience, http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu (accessed on 23 October 2019).

[17] Cicchetti, D. (2013), “Annual Research Review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children - past, present, and future perspectives”, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Vol. 54/4, pp. 402-422, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x.

[9] Ellenbogen, S., B. Klein and C. Wekerle (2014), “Early childhood education as a resilience intervention for maltreated children”, Early Child Development and Care, Vol. 184/9-10, pp. 1364-1377, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.916076.

[23] Heckman, J. (2008), “The Case for Investing in Disadvantaged Young Children”, CESifo DICE Report, Vol. 06/2, pp. 3-8, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/166932/1/ifo-dice-report-v06-y2008-i2-p03-08.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2019).

[22] Hendren, N. and B. Sprung-Keyser (2019), “A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies”, Department of Economics, Harvard University, https://scholar.harvard.edu/hendren/publications/unified-welfare-analysis-government-policies (accessed on 12 September 2019).

[3] Jopling, M. and S. Vincent (2016), Vulnerable Children: Needs and Provision in the Primary Phase, CPRT Research Survey 6 (new series), Cambridge Primary Review Trust, Cambridge, http://www.cprtrust.org.uk (accessed on 3 May 2019).

[15] OECD (2018), Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264073234-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Opportunities for All: A Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264301665-en.

[25] OECD (2015), How’s Life? 2015., OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/23089679 (accessed on 6 May 2019).

[20] OECD (2015), Integrating Social Services for Vulnerable Groups: Bridging Sectors for Better Service Delivery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264233775-en.

[14] OECD (2011), Against the Odds: Disadvantaged Students Who Succeed in School, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264090873-en.

[21] OECD (2011), Estonia: Towards a Single Government Approach, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264104860-en.

[24] OECD (2009), Doing Better for Children, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://www.sourceoecd.org/education/9789264059337www.sourceoecd.org/socialissues/9789264059337www.sourceoecd.org/9789264059337 (accessed on 2 July 2019).

[16] OECD. (2018), The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background Factors that Shape Well-being, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292093-en (accessed on 14 May 2019).

[6] Radcliff, E. et al. (2019), “Homelessness in Childhood and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)”, Maternal and Child Health Journal, Vol. 23/6, pp. 811-820, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-02698-w.

[7] Schnurr, M. and B. Lohman (2013), “Longitudinal Impact of Toddlers’ Exposure to Domestic Violence”, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, Vol. 22/9, pp. 1015-1031, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2013.834019.

[2] Schweiger, G. (2019), “Ethics, poverty and children’s vulnerability”, Ethics and Social Welfare, pp. 1-14, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2019.1593480.

[8] Sentenac, M. et al. (2019), “Education disparities in young people with and without neurodisabilities”, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, Vol. 61/2, pp. 226-231, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14014.

[19] Southwick, S. et al. (2014), “Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives”, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, Vol. 5/1, p. 25338, http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338.

[11] Ungar, M., M. Ghazinour and J. Richter (2013), “Annual Research Review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development?”, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Vol. 54/4, pp. 348-366, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12025.

[18] VicHealth (2015), Current theories relating to resilience and young people: a literature review, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Melbourne.

[5] Wikle, J. (2018), “Adolescent Exposure to Community and Family in Neighborhoods with High Intergenerational Mobility”, https://www.popcenter.umd.edu/research/sponsored-events/tu2018/papers/wikle (accessed on 5 June 2019).

[12] Zolkoski, S. and L. Bullock (2012), “Resilience in children and youth: A review”, Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 34/12, pp. 2295-2303, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2012.08.009.

Note

← 1. The OECD began working on child well-being in 2009 and developed a measurement framework that was used to provide an extensive analysis of child well-being in the reports Doing Better for Children (OECD, 2009[24]) and How’s Life 2015 (OECD, 2015[25]). The OECD has a Child Well-Being Portal to conduct policy-oriented research on children, enhance child well-being and promote equal opportunities among children.