This chapter builds on the insights gained in the previous chapters and identifies six policy areas around which child well-being strategies could be organised. They are policies empowering vulnerable families; policies strengthening children’s emotional and social skills; child protection policies; policies improving educational outcomes; and policies improving health outcomes.

Changing the Odds for Vulnerable Children

4. Building resilience: policies to improve child well-being

Abstract

Introduction

The previous chapters analysed the various individual and environmental factors contributing to child vulnerability. In summary, child vulnerability is the outcome of the interaction of a range of individual and environmental factors that compound dynamically over time. This chapter identifies six policy areas around which child well-being strategies could be organised These policies reduce the barriers to healthy child development and well-being (risk factors) and increase opportunities and resources (protective factors), thereby building resilience. The chapter presents a selection of best-practice programmes and policy initiatives suited to building resilience in children that have been recently implemented in OECD countries.

Which policies can empower vulnerable families?

Provide opportunities for parents to gain parenting skills, knowledge and resources

Vulnerable children and their families benefit from access to a range of services aimed at reducing stressors and building protective factors to promote healthy child development and well‑being. These family services are often publically provided or community-led and tend to invest in crisis interventions over preventative and early intervention (Lonne et al., 2008[1]).

By helping families with day-to-day tasks and parenting skills, family-based interventions can prevent or remedy dysfunctions that are harmful to child well-being and development. Family-based interventions play a crucial role in improving children's living environments, and are important for parents with limited access to material and/or cultural resources to help children learn and develop (Acquah and Thévenon, forthcoming[2]). They are particularly relevant for meeting the specific needs of individual children, building parental capacity and reducing stress and hazards in the family environment. Although the benefits of these programmes can be considerable, so too can be the costs (Michalopoulos et al., 2017[3]).

Home visits following the birth of a child reach families who would otherwise lack the information or social capital to use the services to which they are entitled. Certain vulnerable groups, such as young first‑time mothers and parents with intellectual disabilities, benefit from this intensive support. The Nurse‑Family Partnership is an intensive programme delivered in the United States by specially recruited and trained nurses who visit first‑time teenage mothers from early pregnancy until their child reaches two years of age. During visits, mothers receive information on prenatal health care and child development and learn to respond sensitively and competently to their children’s needs. Evidence shows that this type of programme has positive effects on child cognitive development, well‑being and school achievement (Olds et al., 2004[4]) (Robling et al., 2016[5]), and reduces exposure to intimate partner violence (Mejdoubi et al., 2013[6]) and child maltreatment (Olds et al., 1986[7]). Parents with disabilities may find it more difficult to provide adequate care and need support in acquiring basic parenting skills. A review of randomised control trials on in-home training interventions for parents with intellectual disabilities in Australia, Canada, the United States and the Netherlands suggests that such programmes can improve safe home practices and the recognition of childhood illness, and reduce parental stress (Coren, Ramsbotham and Gschwandtner, 2018[8]).

Group‑based parenting programmes can help parents gain a better understanding of child development and learn more effective and consistent discipline methods. There is evidence that parenting programmes can have moderate effects on children’s behaviour over time (Mingebach et al., 2018[9]). An example in a number of OECD countries is the Incredible Years programme, delivered through weekly group sessions for parents of children up to 12 years of age. A New Zealand study on this programme found clear evidence at the six‑month follow-up of child behaviour changes and improvements in parenting behaviour and family relationships. Effect sizes in parenting behaviours and family relationships were smaller than the effect size in child behaviour, suggesting that small changes in parenting and family relationships produce substantial improvements in child behaviour. Broadly similar gains were recorded among Māori and non‑Māori children, though evidence suggests that Māori families could benefit from further support to maximise gains in improved child behaviour (Sturrock et al., 2013[10]).

The OECD is building an inventory of family services to support parents in the raising and care of children. This inventory also compares the policies implemented to assist the development of these services. Overall, the aim is to strengthen the implementation of evidence-based family support programmes and the more efficient use of resources. This inventory will be available from the second half of 2020.

Work together with families to reduce specific risks to child well-being

Policy needs to respond to specific family-level risks to child well-being such as intimate partner violence (IPV) and high family stress.

IPV interventions that work jointly with children and parents yield positive results for both. For example, the Community Group Programme, run in both Canada and the United Kingdom, helps children process their family experience of IPV through psycho-education delivered in separate groups to children and mothers over a 12-week period. A UK evaluation of the programme found that participating children developed better safety strategies (e.g. not to intervene in fights and to seek help from neighbours) and learned to prioritise their own well-being. Mothers found the programme helpful for learning how to move on from violent relationships and to strengthen parent‑child relationships (Nolas, Neville and Sanders-McDonagh, 2012[11]).

The Caring Dads: Safer Children (CDSC) programme, also run in Canada and the United Kingdom, motivates men who have perpetrated IPV to change their behaviour by focusing on their roles as fathers. The programme comprises three interventions over a 17-week period: group work with fathers, partner engagement and coordinated family case management. Programme participation is linked with a reduction in reported IPV, reduced parental stress for fathers, and improvements in children’s feelings of safety, although some men continue to pose a risk. Delivering the programme effectively relies on project workers having strong skill sets and good relationships with external agencies (McConnell, Barnard and Taylor, 2017[12]).

Invest in communities to support vulnerable families

Some OECD countries operationalise whole‑community approaches to early intervention and prevention. In Australia, Communities for Children Facilitating Partners, present in 52 disadvantaged communities, aims at improving the health and well-being of families and the development of young children from birth until 12 years by delivering early intervention and prevention services including parenting support, group peer support, case management, home visits, community events and life skills courses. A minimum of 50% of the budget is allocated to evidence-based programming (ACIL Allen Consulting, 2016[13]). A review of the programme’s initial implementation stage (2004-2009) found small but positive effects on children, families and the community; improvements in child behaviour and social, motor and language skills; successful transitions to mainstream services; increased parenting and coping skills; improved parental attitudes towards children; higher levels of reported neighbourhood social cohesion; and increased interaction between local agencies (Muir et al., 2009[14]).

In the United States, Strong Communities for Children (SC) develops neighbourhood‑based child protection systems to support families, making child protection a shared responsibility. Rather than specific interventions, the model is based on a set of guiding principles, for example integrating support into settings where children and families are normally found, broadly mobilising community residents and leaders to become involved, and providing support universally and in non-stigmatizing ways. An evaluation measuring the model’s effect in SC communities and control communities showed gains in social support and collective efficacy, improved perceptions of neighbours’ parenting, decreased parental stress, and a small decrease in child maltreatment (McDonell, Ben-Arieh and Melton, 2015[15]).

In the United Kingdom, Sure Start centres support children’s school readiness, health, and social and emotional well-being by providing services to families in socially‑disadvantaged areas who have high support needs, including early childcare and education, health services and parenting and employment advice. Evaluations of programme outcomes showed reductions in family disorganisation and parental stress, and improvements in home learning environments and parent-child relationships. For children aged 5-11 years, long-term health benefits were captured through reductions in hospital admissions and fewer infections among younger children (possibly because increased interaction with other children strengthens immune systems; the centres also support immunisation). Among older children (10-11 years), injury‑related hospital admissions decreased by 30% (Cattan et al., 2019[16]; Sammons and et al, 2015[17]).

Which policies can strengthen children’s emotional and social well-being?

Enhance the role of schools in promoting good emotional and social well-being

Education systems play a primary role in supporting children’s emotional well-being and identifying and assisting students who need support.

Promotion of emotional well-being in school environments differs between and within OECD countries. Twenty out of 24 countries responding to the OECD’s 21st Century Children Policy Questionnaire reported that emotional well-being is covered in existing teacher education training and professional development, though many respondents could not describe, as a general rule, how teachers dealt with emotional well‑being in practice given existing regional, teacher and school autonomy (Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[18]).

On top of teacher training, schools can promote emotional and social well-being by providing students with opportunities to develop social and emotional skills. Many countries have already integrated social and emotional skill development into their national and sub-national curricula (Table 4.1). For example, Norway has introduced building life-skills and learning about mental health as a cross-curricular theme. Ireland has introduced a framework for use in early years and primary school settings to promote well-being and a sense of identity and belonging (Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[18]).

Some countries have gone a step further by developing emotional well-being frameworks drawn up by central governments and implemented locally. These often integrate health services, with increased focus on strengthening the protective factors and resilience of children through different aspects of the school environment (Burns, 2019). For example, the Australian Student Wellbeing Framework concentrates on five areas (leadership, inclusion, support, student voice and partnerships) to support school communities in building positive and inclusive learning environments.

Provide timely and accessible early intervention for children with mental health difficulties

Improving outcomes for children with mental health difficulties requires timely access to early intervention and treatment. This requires building partnerships between the professionals involved in children’s lives, sharing knowledge and information on local services.

Table 4.1. Integrating social and emotional skills into the curriculum – selected examples

|

Programme |

Type |

Skills and content addressed |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ireland |

Aistear (Early Childhood Curriculum Framework for children from birth to 6 years) |

Curricular |

|

|

Ireland |

Social Personal and Health Education (SPHE) curriculum |

Curricular |

|

|

Norway |

Curriculum reform and legislation regarding the School Health Service (2017) |

Curricular and regulatory |

|

|

Portugal |

Student Profile by the End of Compulsory Schooling (Perfil dos Alunos à Saída da Escolaridade Obrigatória, PA) |

Curricular |

|

|

Scotland |

Health and Well-being area (Curricular for Excellence) |

Curricular |

|

|

Korea |

Child Welfare Act, School Health Act, Character Education Promotion Act |

Curricular and regulatory |

|

Source: Adapted from 21st Century Children Policy Questionnaire (Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[18]).

A good example is the United States’ Healthy Students, Promising Futures toolkit, which compiles information on resources, programmes and services offered by non-governmental organisations in different states to outline high-impact opportunities. In New Zealand, the Ministries of Health and Education, the Ministry for Children and non‑governmental organisations have collaborated to provide schools access to social workers, youth workers and nurses. Nurses carry out a HEEADSSS (Home, Education, Eating, Activities, Drugs and Alcohol, Suicide and Depression, Sexuality and Safety) wellness assessment for students in the first year of secondary school to identify any medical or mental health issues and refer students for further treatment.

Early intervention services can be more effective if delivered at the community level (Castillo et al., 2019[19]). An example is Ireland’s Jigsaw project, a prevention and early intervention service aimed at young people (12-25 years) with mild to moderate mental health difficulties. The service is delivered across different sites, often in socially disadvantaged communities, with efforts made to engage the most vulnerable groups of young people. Jigsaw works to provide accessible brief counselling interventions (six sessions) and to increase local mental health literacy through youth-led action. Evaluation of Jigsaw interventions found evidence of significant reductions in the level of distress experienced by young people and progress in setting and achieving personal goals (Community Consultants, 2018[20]).

Many youth services offer online or “e-counselling”, for example Australia’s eHeadspace, which allows young people (12-25 years) to connect with trained counsellors through online chat and e-mail. The plus side of e-counselling is that it increases service accessibility and geographical reach and provides an alternative to face-face contact, which some young people may prefer. After engaging with the service, typically after a few sessions, a more thorough assessment is completed with the young person to draw up a treatment plan. An evaluation of the effectiveness of eHeadspace found a small but significant correlation in the reduction of psychological distress (Dowling and Rickwood, 2014[21]). The longer a young person engages with the service, the more beneficial it may be. Retaining young people over the longer term is a challenge for online services in general.

Ensure smooth transitions of young people onto adult mental health services

Clear policies can aid the successful transition of vulnerable young people from child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) into adult services and avoid discontinuity of care. This entails specific policies such as the development of youth‑tailored care pathways and standardised assessment frameworks for young people approaching the transition age-boundary. Importantly, policies should incorporate the inclusion of young people and their families in the care planning process (Signorini et al., 2018[22]).

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines support the planned transition of young people to adult services. These guidelines require CAMHS to provide direct support to young people who are failing to engage with adult services. The Guidelines include the allocation of one consistent social worker from the transition assessment and planning process through to the first review of care and until the support plan has been completed by adult services (NICE, 2016[23]).

Provide opportunities for vulnerable children to build relationships with supportive adults and role models

Mentoring is a popular and longstanding intervention for vulnerable adolescents. Mentoring programmes match adolescents with positive adult role models who support them in taking part in productive activities and committing to socially appropriate personal goals (Whybra et al., 2018[24]). Successful mentoring is associated with higher subjective well-being, greater sense of belonging within the family and community, and resilience during episodes of adversity (Devlin et al., 2014[25]).

Two of the better-known mentoring programmes are Big Brothers Big Sisters of America (United States) and the Youth Advocate Programme (Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States). In these programmes an adult role model is selected based on common interests and trained to work with an adolescent for an agreed period of time. The effectiveness of mentoring is strongest for adolescents exposed to high environmental risks (e.g. maltreatment, peer rejection and parental separation and abandonment), and those with behavioural and conduct problems. Research suggests that this type of intervention works best if the young person is working to improve outcomes across a number of areas in life and when mentors are properly screened and trained (Dubois et al., 2011[26]).

Provide vulnerable children with access to extra-circular activities

Organised sporting activities can foster positive outcomes in vulnerable children through developmentally appropriate tasks and positive child-adult relationships (Lubans, Plotnikoff and Lubans, 2012[27]). Sport helps children learn how to follow rules, develop self-control and conflict resolution skills, and cope with disappointment. There is evidence that participation in sport is a protective factor against youth delinquency. OECD evidence shows that one in three children in European OECD countries does not have the opportunity to regularly participate in leisure activities.

In the Netherlands, AJB, a sports-based programme funded through the Ministry of Security and Justice targeted at adolescents at risk of developing delinquent behaviours, has had a positive impact on youth behaviour with observed decreases in aggressive behaviour, better acceptance of authority and resistance to peer pressure, and improved educational performance. The success of this programme was correlated to the level of education of coaches and how they built relationships with young people (Spruit et al., 2018[28]).

Research suggests that opportunities to develop musical and artistic abilities benefit vulnerable children’s school performance and socio-emotional skills. In the United States, a randomised control trial was conducted to examine the benefits of the introduction of arts education (Houston Arts Access Initiative) through community art partnerships to 3rd to 8th grade children (8 to 14 year-olds) with limited exposure to cultural activities. Over 10,000 children in 42 schools were provided with substantial arts education inputs over the course of an academic year. The findings showed significant reductions in the number of students receiving disciplinary infractions, and improvements in writing achievement, school engagement and level of compassion for fellow students (Daniel Bowen, Kisida and Roeder, 2019[29]).

Empower children online and build digital resilience

The digital environment presents both opportunities and risks for children. Preparing children for the digital society needs to begin early, in families and schools where parents and teachers equip children not only with cognitive skills but also with digital resilience, defined as the ability to manage the risks and opportunities of going online (Hooft Graafland, 2018[30]; Hatlevik and Hatlevik, 2018[31]).

Parents’ involvement in their children’s digital education is increasingly important, as many children first access digital devices at home. When parents lack the skills required to help children manage their online activity, others need to step in to build children’s digital resilience and avoid further exacerbating digital inequalities. Digital inequality is not only about access to ICT but also about how it is used. PISA 2015 data shows that advantaged students and disadvantaged students use ICT differently: advantaged students use it more to access news (70%) and obtain practical information (74%), in comparison to disadvantaged students (55 and 56% respectively).

The digital environment can sometimes reproduce and amplify harmful behaviour that exists outside the digital sphere (Livingstone et al., 2011[32]). Cyber-stalking, online harassment and cyberbullying are only a few examples of such behaviours. Tackling these problems requires a coordinated response from parents, schools, social media and tech companies, as well as lawmakers. This multi‑stakeholder approach is key, as children from disadvantaged homes are more likely to have parents with lower digital skills, and those parents less likely to be involved in their schooling. This makes the involvement of schools and the broader community even more important for building digital resilience and skills more generally (Burns and Gottschalk, 2019).

The increasing use of new technologies and devices has triggered fears that they may harm well‑being in other ways, including negatively affecting users’ mental health. This link is proving difficult to establish, however. To date, the research suggests that moderate use of digital technologies seems mostly to have beneficial effects on mental well-being, with no or excessive use having small negative consequences. The impacts of new technologies and devices on mental health may vary significantly across children. Highly skilled individuals are likely to be better informed about the risks associated with extreme usage of technology and to pay more attention to screen time and use of personal devices. Data from PISA suggest that top-performing students are less likely to feel bad without an Internet connection. On average across OECD countries with available data, 45% of students with top performance in reading, mathematics and science reported negative feelings in the absence of an Internet connection, in contrast to 62% among low performers (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Feeling bad without Internet connection, by students’ performance

Note: Students who are low performers are students who score at less than Level 2 in the reading, mathematics and science assessments. Level 2 is considered to be the baseline level of proficiency in reading, mathematics and science. Students who are top performers are students who are proficient at Level 5 or 6 in reading, mathematics and science. Shares for countries with less than 100 observations available for top or low performer categories are not reported in the figure.

Source: OECD (2019), "Feeling bad without Internet connection, by students’ performance: Percentage of students who reported to agree or strongly agree to feel bad without Internet connection", in OECD Skills Outlook 2019: Thriving in a Digital World, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b707fe08-en.

Parents’ digital skills and awareness affect the types of opportunities and threats their children experience online. Digitally skilled parents are more likely to have an enabling approach to Internet use, encouraging their children to explore and learn things online and sharing online activities them, but also explaining the inappropriate nature of some websites (Livingstone et al., 2017[33]). While such a strategy may also expose children to more risks, it also enables them to develop resilience and be better prepared to grapple with risks when they arise. Policies that seek to minimise digital inequalities as well as the risks faced by children and adults online should also aim to boost parents’ and children’s digital skills, using skills development as levers.

On another hand, increasing evidence suggests parental use of mobile devices adversely affects child-parent interactions. In the United States, 51% of US adolescents (13-17 years old) said their parents were “often” (14%) or “sometimes” (34%) distracted by their cell phone during attempts to have a face-to-face conversation (Pew Research Center, 2018[34]). Parents who use smartphones during parent-child play are usually less sensitive and responsive to their children, verbally and non-verbally, and children are more likely to engage in potentially harmful attention-seeking behaviours (Kildare and Middlemiss, 2017[35]). More longitudinal studies are needed to assess robustly how these changes in parent-child interactions affect children’s long-term socio-emotional skills development, and whether the context in which interactions take place (e.g. during meals, playtime, vacation) or the type of mobile phone activity engaged in by the parent make a difference (Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[18])

Teachers and schools are natural candidates to support the development of digital skills and resilience. To ensure education systems are able to adapt to new requirements, professional development programmes need to prepare teachers and school to educate students on online safety and privacy, understand the implications of some online behaviours and identify various forms of online harassment that build up in schools. Integrating online safety or digital citizenship responsibilities in the curriculum can also be considered, although more evaluations are needed to establish the effectiveness of such interventions (Hooft Graafland, 2018[30]). Beyond education systems, policy makers could also consider a co-ordinated regulatory response to child protection and better measuring and monitoring of existing policies (OECD, 2018[36]).

The OECD is currently reviewing the 2012 OECD Recommendation on the Protection of Children Online with a view to updating these recommendations to reflect persistent, evolving and emerging risks. For example, although cyberbullying was a definite concern in 2011, in 2017 an OECD country survey showed that it was now the highest priority for member countries. Issues that did not yet exist or were not highly visible during the 2011 consultation, such as sexting or sextortion, are now common. Although government action is moving in the right direction, the policy environment is very fragmented and without a sufficient understanding of the impacts of policy and legalisation. International and regional cooperation is key in addressing the cross-border challenges of digital participation.

Which policies can strengthen child protection?

Make child protection services more child-centred and accessible

Child protection services should offer support to vulnerable families to prevent poor outcomes for children and exercise their mandated power to intervene when children are in real need of protection. The key tenets of child protection legalisation and policies in the OECD include safeguarding children from maltreatment, promoting children’s best interests and family preservation. OECD countries operate different types of child protection services that in general fall between ‘child protection system’ and ‘family welfare system’ approaches. A child protection system approach operates high thresholds for interventions and focuses on preventing and stopping serious harm. A family welfare system approach aims to promote a healthy childhood and prevent serious harm though universally accessible services (Križ and Skivenes, 2014[37]).Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, the US and the UK and operate closer to the child protection systems approach whereas in Denmark, Finland and Norway operate closer to the family welfare system approach (Pösö, Skivenes and Hestbæk, 2014[38]).

Child protection services should be accessible to children and families in need. Some countries have made efforts to become more accessible and provide more appropriate responses by adopting the differential response (DR) model, for example Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and the United States. An overarching aim of DR is to facilitate a more nuanced approach to working with vulnerable families and to extend access to services to lower-risk families and to families who voluntarily accept help. DR involves a differential two-pathway approach; one directing families to support services like parenting support (alternative response) and the other to child protection investigations (investigative response). The approach requires strong initial screening and assessment tools to identify which pathway is the most suitable for families (Merkel-Holguin and Bross, 2015[39]). Assessing the effectiveness of DR is problematic as evaluation studies are limited by the use of narrow child protection indicators (like rates of re-referrals to CPS) and focus on substantiated incidences of child maltreatment rather than measuring positive changes in family functioning and child well-being. Moreover, some evaluations have included high-risk families, whose needs the DR system was never designed to meet and therefore much less likely to help (Conley and Duerr Berrick, 2010[40]).

Vulnerable children receive a better service when all agencies involved in children’s lives, such as schools, hospitals, child protection, and the police, work together. In New Zealand, the Ministries of Health, Education, Social Development, Justice, Oranga Tamariki (child protection and youth justice agency) and the police must develop and publish an Oranga Tamariki Action Plan, which is a plan for how agencies will work together to improve the wellbeing of children in or on the cusp of entering the care and protection or youth justice system as well as those young people up to the age of 25 who are transitioning out of the system. The aim is to ensure that these children and young people receive the right level of support, at the right time, in every area of their lives.

Invest in improving outcomes for children in out-of-home care

Harmonised data on children in out-of-care would contribute to raising outcomes of these very vulnerable children by facilitating policy development in OECD countries of similar child protection systems and informing evidence-based policymaking. At a minimum, data should include trends in numbers coming into care, reasons for care admissions, and care placements types. Data should also capture the effect of out-of-home care on the different dimensions of child well-being.

Enhance the well-being of children placed in out-of-home care requires, greater investment is needed in resources that build protective factors. Overall, better outcomes for children in out-of-home care are associated with reception into care at a younger age, minimal care and school placement disruptions, placement in kinship or foster care, maintenance of positive contact with birth family, and the continued support of an adult after ageing out of the care system (Akister, Owens and Goodyer, 2010[41]; Frechon, Breugnot and Marquet, 2017[42]; Gypen et al., 2017[43]).

Supporting kinship care keeps children with their families, can contribute to better outcomes. In kinship care children are cared for by relatives, such as grandparents or aunts and uncles, whose desire to keep children within the family can motivate their commitment. Empirically it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the effect of kinship care on child well-being. In the United States, a change in policy towards a preference for kinship care in some states has shown evidence that kinship care contributes to better child protection outcomes: shorter care admissions, less placement disruptions, and decreased likelihood of future maltreatment by a caregiver (Hayduk, 2017[44]).

It is very important to provide kinship families with financial and emotional support and training opportunities to develop the skill sets to meet children’s high needs. CPS should ensure that all kinship families have access to support workers. A good example of training in the United States is Keeping Foster and Kin Parents Supported and Trained (KEEP), which helps carers to learn and implement strategies to manage challenging behaviours and to create a nurturing home environments. This has been shown to improve children’s behaviour, which in turn contributes to placement stabilities (Chamberlain, 2017[45]).

Policies should support contact between children in out-of-home care and their family of origin; however, not all contact is good for children. Decisions around contact should be made on a case-to-case basis. Moreover, the wishes of children should always be considered. Contact can be harmful if it is poorly planned, of poor quality, and/or poorly supervised. CPS can influence the quality of contact by supporting parents and children –before and during- to make full use of this time (Sen and Broadhurst, 2011[46]).

Countries should have aftercare policies in place to support the transition of young people ageing out of the care system. This entails a statutory entitlement for assistance until reaching a particular age and/or completing education and training. In recent years, some OECD countries have strengthened access to aftercare services, for example France, Ireland and Scotland (United Kingdom) and New Zealand. In France aftercare policies are decided on and operated at a local level. This means that the support young care leavers can accept to receive depends much on where they reside. In New Zealand, there are provisions to allow young people to remain or return living with a carer until 21 years of age and to access transition support and advice until 25 years of age.

The quality of out-of-home care and the opportunities provided to build human and social capital influence the level of support young care leavers need. Young care leaver may need assistance with matters that other young people can rely on their family for, such as advice and support, and help securing accommodation and employment, and attending medical appointments. They also need reliable contact with positive role models. Specific evaluation on support programmes for young care leavers to inform policy are needed as much of the programme evaluations has focused more broadly on vulnerable young people.

Young care leavers are at higher risk of experiencing homelessness (Fowler et al., 2017[47]). In the US, an evaluation of First Place for Youth service, which works on reducing homelessness among young care leavers aged 18 to 24 years by providing accommodation and intensive case management, concluded positive preliminary outcomes (within first six months- year of service induction). The goal of the service is to engage the young people over an 18-month period minimum in building positive life skills, including maintaining stable accommodation, accessing education and/or employment and to improving well-being. In summary, the evaluation found that 68% enrolled in education, 72% were employed, greater self-reported security, safety and quality, and less self-reported depression and greater positive social supports. These outcomes are higher than usual for this population. The relationship between young person and allocated keyworker was a central part of these changes (Goldsmith et al., 2012[48]).

Which policies can improve children’s education outcomes?

Increase participation of vulnerable children in early childhood education and care

Participation in early childhood education and care (ECEC) can be an important protective factor in the lives of vulnerable children. A number of countries have defined education policies specifically to increase children from lower socio-economic backgrounds. In Scotland (UK), 2-4 year-old children from disadvantaged families are entitled to 16 hours of free provision per week (600 hours/year) since 2014, above the normal number of hours of free provision of around 12 hours per week. In the Netherlands, targeted programs for children from disadvantaged backgrounds (age 3 and 4) are available in both childcare and playgroups. In some municipalities of the country, those target-group specific programmes are free (OECD, 2017[49]).

Norway offers an interesting example of a country that implemented a series of measures aimed at improving the enrolment rate of children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds in ECEC. Despite a significant reduction of the amount of parental fees for ECEC between 2004 and 2014, parental fees still appeared as a disincentive for participation in ECEC for more disadvantaged families (Moafi and Bjørkli, 2011[50]). Authorities in Norway reacted by implementing several policies to remedy this situation. In 2015, a regulation capping the maximum annual fee for ECEC participation at not more than 6% of the family income was introduced. In addition, children aged 4 and 5 were given the right to 20 free hours of preschool per week, a measure extended to 3 year-old one year later. Finally, the grant given to municipalities for outreach programmes to families with low socioeconomic and minority backgrounds was increased by 118, 000 USD from 2016 onward (OECD, 2017[49]).

Research on these measures have concluded the positive effect of these policies on the enrolment rates and the outcomes of children from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Preliminary findings on Norway indicate that the availability of 20 hours of free pre-schooling increased the participation of minority-language children by 15%, leading to better results on mapping tests in the first and second grade compared to areas with no intervention (i.e. no free preschool hours allocation) (Bråten et al., 2014[51]; Drange, 2015[52]).

Other studies have demonstrated that an effective policy consists in ensuring the socioeconomically diverse nature of the ECEC centre and avoid the concentration of children form lower socio-economic backgrounds in the same centres. Research led in the US found that children from low-socioeconomic backgrounds who were integrated into ECEC programmes that are socio-economic diverse scored similarly to their peers from non-disadvantaged backgrounds, but only if they spoke only English at home. (Schechter and Bye, 2007[53]). A study comparing socioeconomically mixed preschools and targeted programmes in the Netherlands also found that disadvantaged children in mixed preschool and kindergarten classrooms gained more in literacy and math than disadvantaged children enrolled in programmes specifically targeted at them (de Haan et al., 2013[54]). Ensuring the socioeconomic diversity of preschools therefore appears as a promising way to allow vulnerable children to catch up on their peers.

Improve the quality of early childhood education and care vulnerable children receive

The magnitude of the benefits of ECEC for vulnerable children depends on the level of quality provided in ECEC services. Low-quality can be associated with no benefits or even detrimental effects on children’s development and learning (Britto, Yoshikawa and Boller, 2011[55]; Howes et al., 2008[56]). Quality first includes characteristics of structural quality, such as the infrastructures of the centre and the available physical, human and material resources. These aspects are traditionally the easiest to regulate, through regulations of child-staff ratios for instance (Slot et al., 2015[57]; Barros et al., 2016[58]).

Other aspects of quality include the quality of the interactions between children and ECEC staff or among children, so-called process quality, which involves the more proximal processes of children’s everyday experience in ECEC centres. Process quality covers the social, emotional, physical and instructional aspects of children interactions with staff and other children while being involved in play, activities or routines (Pianta et al., 2005[59]; Anders, 2015[60]; Barros et al., 2016[58]; Ghazvini and Mullis, 2010[61]). The shape of these interactions will then participate in creating an environment in which children feel safe and emotionally supported, in a way that allows their language and socialisation skills to develop.

Some studies brought evidence that an environment of high-quality childcare was more positively associated with school readiness and language skills for low-income 3-year-olds than for children of non-disadvantaged families (McCartney et al., 2007[62]). This positive association was in turn associated with a reduced achievement gap in maths and literacy through elementary school years (Dearing, McCartney and Taylor, 2009[63]). A study led in the UK found that participation in ECEC in centre-based care for children aged 9 months was associated with better cognitive skills at age 3 and 5, and that the effect was more than twice as strong for children of mothers with a low level of education (Cote et al., 2013[64]). Other studies led in the United States and Norway found that ECEC provision for lower-income children contribute to reduce inequalities in language acquisition of children from non-disadvantaged families (Duncan and Sojourner, 2013[65]; Dearing et al., 2018[66]).

However, greater positive effects of ECEC participation for children from lower-income families are not consistently found. Some studies show a positive impact of ECEC on cognitive outcomes for all children, but not more so for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. This could be explained by the fact that children from lower-income families are less likely to benefit from the highest quality ECEC (Ruzek et al., 2014[67]) as well as that ECEC complements the stimulation that children receive at home, and therefore unintentionally favouring advantaged students (Ceci and Papierno, 2005[68]).

Adopt measures to reduce inequity in education

Countries should create and reinforce policies and programmes that support disadvantaged students at the stages when inequity in education is most prevalent, ideally before inequity emerges. Countries could develop age-appropriate national assessments and conduct longitudinal studies to monitor inequities. Countries could also monitor the progress of disadvantaged students by setting progressive benchmarking points that account for equity in education. For example, to improve the academic performance of disadvantaged students, countries might want to distinguish between benchmarks based on national criteria, such as reaching a certain share of disadvantaged students who achieve excellence by national standards.

Policies should focus on building teacher capacity to detect individual student needs, particularly in diverse classroom settings, to close the gap in cognitive and socio-emotional skills related to socio-economic status. Teacher capacity can be built by providing schools with specialised teacher support and training to equip teachers with stronger skills to identify and address learning difficulties, to develop more customised and effective teaching methods, and to foster self-esteem and positive attitudes among disadvantaged students. Furthermore, regular assessments to monitor individual performance can help teachers identify students who are struggling more effectively. These activities could be coupled with greater enthusiasm for personalised learning and the use of technologies that facilitate it.

Additional resources should be allocated to disadvantaged students and disadvantaged schools to equalise opportunities and educational achievement. Schools with larger shares of disadvantaged students require greater investments in both human and material resources. These investments include improvements to school infrastructure, teacher training and support, language-development programmes for immigrant students, tutoring and homework-assistance services, extracurricular activities, and customised instructional programmes to address the learning challenges unique to disadvantaged and minority students. However, it is equally important that school resources reach all students in need, particularly in school with large shares of disadvantaged students.

Policies should address the concentration of disadvantaged students in particular schools and proactively prevent further educational segregation. Importantly, policies need to counteract increasing residential segregation and the greater sorting of students by both ability and socio-economic status. Providing choice to parents without exacerbating segregation can be achieved through the introduction of specific criteria around the allocation of students across schools in the same catchment area. Schools can be incentivised to admit disadvantaged students, for example, by weighting the funds received by the schools, depending on the socio-economic profile of their student populations.

Policies should address the practical barriers against accessing school like tuition costs and availability of public transport. To avoid unfair competition between public and private schools, all publicly funded educational providers should adhere to the same regulations regarding tuition fees and admissions policies. As evidence has shown that attending a school with a large proportion of high achievers does not necessarily result in improvements in individual performance, parents should be provided by prospective schools the relevant information about which advantages, including a measure of the actual “value-added” i.e. whether those schools succeed in improving the performance of all of their students.

Prevent early school leaving and provide early action for school leavers.

Policies should provide intensive, targeted support to address the contributing factors behind early school leaving and youth unemployment. Young people who are not in education or employment (NEETs) are a diverse group. Nevertheless, particular factors including individual (e.g. mental health difficulties, disabilities and migrant background), family (e.g. low parental education, parental unemployment, and caring responsibilities) and school (e.g. low educational attainment, and limited opportunities for vocational training) increase the risk for young people of leaving school early and/or without the necessary skills to secure employment (OECD, 2016[69]).

To tackle the challenge of NEET effectively, countries must ensure that all young people obtain at least an upper secondary school degree that entitles them to pursue third level studies, or the opportunity to develop the vocational skills needed to succeed in the labour market. Policies need to ensure that the signs of school disengagement are detected early, and that young people at risk receive the support they need to complete their education. Strategies to keep at risk students in education yield the most promising results when the address problems at an early stage. Schools should systematically monitor school attendance and keep key stakeholders, notably parents, child protection services and health services, informed to ensure that vulnerable students get the help that they need. Requirements to report attendance to the national education authorities can ensure that parents, schools and municipalities take non-attendance seriously. In Sweden, for instance, municipalities are required to report to the national education authorities on the situation of the young people identified as being at risk, and on what interventions have been tried, every six months.

Making specialised support staff available in schools is key to quickly identifying and addressing the challenges that vulnerable young people may face. Trained psychologists or social workers can be an important first point of call for students, parents and teachers when problems arise. Where schools lack the resources for such specialised staff, designated teaching staff who have received the appropriate training can provide important support (OECD, 2016[70]). In Norway, for instance, schools have the freedom to exempt teachers from some of their teaching duties so that they have the time to address with students and parents the reasons for school absenteeism. These teachers can take students who have concentration or behavioural problems for time out of the classroom for an hour, or drive out to a student’s home in the morning to pick up a pupil who has failed to show up.

Well-designed after-school programmes can make a considerable contribution to the educational and social development of young people, and to staying on in school. Attractive opportunities for young people to engage in sports, learn a musical instrument or get involved in handicraft and other practical activities can help build social and professional skills, while countering the risk of isolation. Empirical evidence confirms the positive effects of extracurricular activities on schooling outcomes and career prospects (OECD, 2012[71]; Carcillo et al., 2015[72]), and these effects tend to be largest for youth from deprived backgrounds (Heckman, 2008[73]). As participation in private after-school schemes is often at the parents’ initiative, however, the young people who take part in such activities tend to in most cases come from well-off backgrounds (OECD, 2011[74])

Quality vocational education and training can help smooth school-to-work transitions. The combination of classroom learning and practical training is an attractive learning pathway (OECD, 2016[70]). Yet, on average, slightly less than half of upper-secondary students in the OECD follow a VET courses, although proportions vary considerably between countries. Apprenticeship courses, which match students with private- or public-sector employers early on in the programme, typically for a period of several years, are often regarded as best practice. Apprenticeships may also be effective against early school leaving: they appeal to more practically-minded young people who may lack the aptitude to for further classroom-based learning, and reduce incentives to leave school for paid work. There is renewed interest in apprenticeship training due to the positive results produced by apprenticeship programmes – in particular favourable youth labour market outcomes- in countries with a tradition of strong apprenticeship systems like Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Countries are increasingly concerned with promoting the attractiveness and relevance of VET programmes to boost participation. A number of European countries, such as Italy and Spain, are working closely with Germany to reform their VET systems, and Korea introduced an apprenticeship system inspired by the German, British and Australian systems in 2014.

While the long-term goal of public policies is to help young people become independent, those on low-incomes, especially NEETs may require income support to avoid poverty. Only a few OECD countries operate income support benefits that exclusively targets young people. Instead, most countries provide access to income support programmes for working-age adults with the exception of Australia, which has a youth job-seekers allowance (16-21 years of age). The actual income support benefits for youth tends to be low because of both low coverage and benefit adequacy (OECD, 2016[70]).

Support the integration of migrant children in schools

Improving the coordination among different actors as well as the evidence basis on what works will help improve the impact and sustainability of policies supporting the integration of migrant children at schools. OECD countries have used a range of responses to support the resilience of students with an immigrant background. Policy makers, civil society organisations, schools and citizens have helped support the educational integration of new arrivals and students with other migration profiles. This experience has led to a range of approaches in regards to integrating immigrant students and communities into the education systems of host countries. Insights from the OECD Strength through Diversity reveal that using a holistic approach that addresses not only academic proficiency but also well-being can be an effective way to support students with an immigrant background.

Grouping individuals based on their immigrant background can help target service delivery and support integration processes. However, this is not always possible, since immigrant populations may have rather heterogeneous characteristics, which could create barriers or fail to address dimensions important for an individual’s well-being, development and integration. Students with an immigrant background can benefit from targeted support but care should be taken to avoid stigmatising individual children.

Education policies should take into account the different sets of vulnerabilities linked to migrant displacements. Considering the differences in social and emotional well-being between immigrant and native populations is crucial to sustaining integration in the long-term. Education systems can play important roles not only in providing migrant students with learning opportunities, but also in promoting their overall well-being. To do so, partnerships and collaboration among schools, hospitals, university and community-based services can help.

Schools and education system can address the multiple needs of refugee children by adopting a holistic approach aimed at supporting their academic, physical, social and psychological development. Refugee children often face a wide array of unique challenges, including the need to overcome interrupted or limited schooling and trauma. Providing individualised development plans and making use of diagnostic assessments can help account for non-standard learning pathways and build professionalism among the teaching community.

Unaccompanied minors and late arrivals with limited schooling can benefit from targeted educational programmes make the transition from school to work. One example is “SchlaU-Schule” in Munich, Germany, which enables unaccompanied minor and young adult refugees to secure secondary school leaving certificates through specially adapted individually based teaching and support in a close-knit school setting, and also their first work experience through internships. The scheme also provides post-school follow-up into mainstream education and the labour market.

School plays an important role in translating the high motivation levels of migrant students into a key asset for immigrant communities (see chapter 3). Schools can do this by strengthening migrant students’ skills, providing new arrivals with educational and career guidance, and helping students and their families develop realistic short-, medium-, and long-term plans can be effective ways to ensure that immigrant students’ motivation and ambition become key assets for their academic and personal outcomes.

Providing language support to ensure that migrants can learn the language of the host country and benefit from education and training opportunities is an essential part of their overall integration. At the same time, migrants’ native languages are important assets in terms of their cultural identity. It is important for education systems to recognise this. Ways of doing so can include supporting plurilingualism, offering mother tongue tuition when feasible and appropriate, building the capacity of teachers to work in linguistically diverse classrooms, and promote opportunities for informal language learning.

Many immigrant children have lower socio-economic status and attend schools in disadvantaged classrooms. The adversity this creates can trigger differences in academic performances but also in the overall individual well-being. Reviewing resource allocations to provide greater support to disadvantaged students and schools can help overcome some of the socio-economic barriers facing immigrant students. Education systems could also consider what institutional and government services are available beyond the education sector to work together in supporting immigrant students with disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds.

As teachers are key actors for immigrant students to reach their full potential, they need the capacity to respond to the individual needs of their students. Providing initial teacher education and professional development that incorporate inclusive education and inter-cultural topics are ways in which countries have built the capacity of teachers to respond to diverse classrooms. Hiring professionals that reflect the student body can be another way to prepare teachers and school leaders for the increasing diversity found in schools.

Which policies can improve children’s health?

Improve the quality and accessibility of pre-natal care for key groups

Broadening access to health insurance and family-planning services are very effective interventions for reducing poor neo-natal outcomes. For instance, the Medicaid expansion in the US in the 1980s increased health insurance coverage for pregnant women, and reduced the numbers of low-birth weight babies and infant mortality among low-income women. Research by (Currie and Gruber, 1996[75]) evidenced that increasing eligibility for Medicaid by 30 percentage points reduced the probability of a low-birth-weight birth by 1.9% and infant mortality by 8.5%. More recent work by (Sonfield, Gold and Benson, 2011[76]) focused on the effects of Medicaid (and other publicly funded) expansions of coverage for family-planning services in certain US states. Better access to family planning was associated with a reduction in unplanned pregnancies, less unprotected sex and improved continuity of contraceptive use. Better pregnancy spacing benefits pregnant women and babies by reducing the risk of low-birth weight, pre-term birth and small size for gestational age.

Support and advice on making positive health behaviour changes during pregnancy should be better targeted to specific groups of expectant mothers. Indeed, all expectant mothers may benefit from advice and information but certain harmful health behaviours are more prevalent among some groups of women, such as smoking during pregnancy among young women and those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds and ethnic groups. These women face unique barriers to quitting smoking, and individual behavioural counselling and reward-based cessation interventions have proven more effective (Scherman, Tolosa and McEvoy, 2018[77]). Again, poor nutrition during pregnancy is related to undernourishment and food insecurity, and low-income, low education and poor living conditions are factors. Certain nutritional programmes can be delivered effectively at the local level, for instance food-distribution systems, or national distribution of calcium supplements to at-risk women to reduce hypertensive disorders and pre-term births (Bhutta et al., 2013[78]). National and regional programmes to reduce pollution in certain regions, improve water quality, hygiene and sanitation conditions are particularly important for low-income mothers.

Routine pre-natal care should screen for individual and family factors that may have an impact on neo‑natal health and parents’ ability to meet infants’ needs. These include intimate partner violence and parental drug and alcohol use. Evidence suggests that one-on-one counselling has some effect on reducing the risk of intimate partner violence during pregnancy and the early post-natal period (Jahanfar, Howard and Medley, 2014[79]). Drug use during pregnancy is a growing problem. Data from the US indicated that in 2013, 5.4% of pregnant women were using illicit drugs. The rate was higher among expectant mothers aged 18-25 years, although overall it is as common across socio-economic classes and racial groups. Multi-disciplinary approach to intervention is needed to help the mother stabilise drug use to minimise the risk of neo-abstinence syndrome (NAS), to implement standardised management of NAS and follow-up on the baby’s discharge from hospital (Shukla and Gomez Pomar, 2019[80]). Overall, more research is needed on the effectiveness of these interventions on neo-natal and maternal health.

Social protection is a crucial policy element for the prevention of pregnancy-related problems. One study from Canada highlighted the association between the allocation of unconditional cash transfers to low-income pregnant women and the reduction in pre-term births, low birth weight and small gestational size (Brownell et al., 2016[81]). Universal simplified perinatal data-collection system with electronic feedback systems, and the improvement in facility-based perinatal care in regions with low coverage are among other recommended measures (WHO, 2014[82]; Rubens et al., 2010[83]).

Improve access to parental leave for low-income families and those with children with additional needs

The provision of paid family leave promotes good maternal health and child health and developmental outcomes. Paid family leave enables mothers to recover from pregnancy and childbirth and allows both parents to care for and bond with their child by providing time off around childbirth and during early infancy. Paid family leave also provides low-income families with time and the economic security to invest in children. In subsequent years, paid family leave may also facilitate parents to care for children when sick (Heymann, Toomey and Furstenberg, 1999[84]).

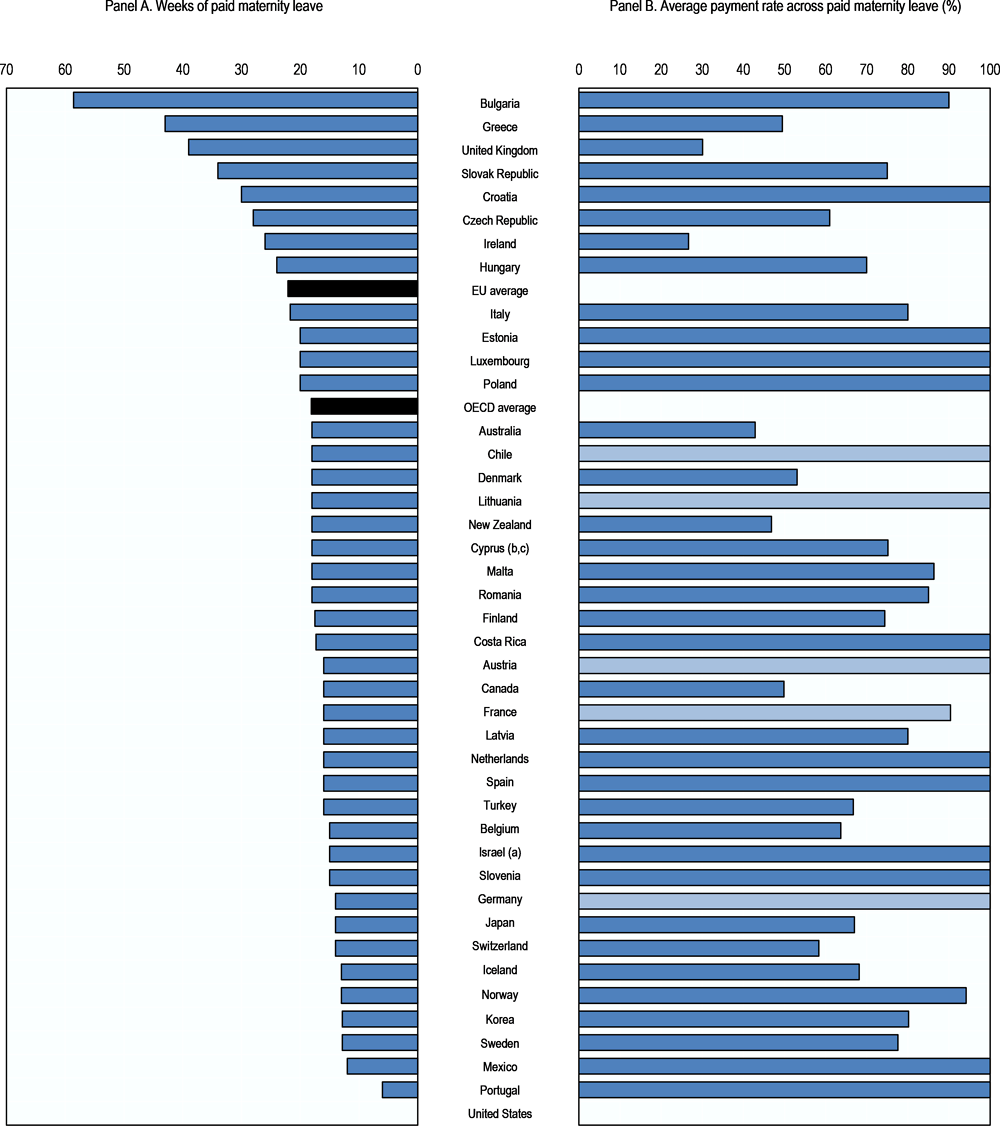

The OECD Family Database provides cross-national on family outcomes and family policies, including child-related leave. The duration of paid family leave and average payment rates varies across the OECD. For example, for paid maternity, Greece and the United Kingdom provided the entitlement at 43 weeks and 39 weeks respectively, while Canada, Portugal and Mexico are among a few countries that provide 100% payment rate (Figure 4.2).

Research points to the positive impact of paid leave on child health, including lower infant mortality and a lower likelihood of low birth weight, although the evidence is mixed. Paid maternity leave gives mothers to have time at home to care for and bond with their baby. Sensitive and responsive caregiving are key for infant development and the formation of secure attachments with a primary caregiver. Research suggests that the quality of the infant-caregiver attachment influences children’s neurophysiological, physical and psychological development (Cozolino, 2013[85]) (Shonkoff, Boyce and McEwen, 2009[86]). Analysis using Australian longitudinal data showed that the effects of paid maternity leave can be significant if the duration of leave is at least 6 weeks. Paid maternity leave reduces the incidences of childhood asthma and bronchitis and significantly increases the likelihood to breastfeed, the duration on breast-feeding and the likelihood of up-to-date immunisation (Khanam, Nghiem and Connelly, 2009[87]). In Canada, the extension in 2011 of paid maternity leave from six to twelve months in 2011 increased the quantity of maternal care and duration of breastfeeding but had no consistent effect on self-reported child health outcomes (Baker and Milligan, 2008[88]).

Evidence from the United States on unpaid leave suggests inconsistent effects on child health outcomes. The introduction of 12 weeks of unpaid leave through the Family and Maternity Leave Act (1993) led to small increases in birth weight, decreases in the likelihood of premature birth and substantial decreases in infant mortality. However, these positive effects hold only for children of educated mothers and not for children of less-educated and single mothers who are less likely to be able to take the unpaid leave (Rossin, 2011[89]). Children whose mothers returned to work after the 12 weeks of unpaid leave were less likely to receive regular medical check-ups, to be breast-feed, and to have all of their DPT/Oral polio immunisations (Berger, Hill and Waldfogel, 2005[90]). OECD analysis on the introduction of paid family leave in the states of California and New Jersey on child immunisation uptake showed significant increases in young children receiving does and full vaccination series. Paid family leave has important effects on the immunisation of children in low-income households, however the effect is much weaker on children living in poverty than children living above or at the poverty line (Adema, Clarke and Frey, 2015[91]).

Figure 4.2. Duration of paid maternity leave and the average payment rate across paid maternity leave for an individual on national average earnings, 2018

Note:Striped bars indicates payment rates based on net earnings. Data for Chile and Costa Rica refer to 2017. Data reflect entitlements at the national or federal level only, and do not reflect regional variations or additional/alternative entitlements provided by states/provinces or local governments in some countries (e.g. Québec in Canada, or California in the United States). The "average payment rate" refers the proportion of previous earnings replaced by the benefit over the length of the paid leave entitlement for a person earning 100% of average national full-time earnings. If this covers more than one period of leave at two different payment rates then a weighted average is calculated based on the length of each period. In most countries benefits are calculated on the basis of gross earnings, with the "payment rates" shown reflecting the proportion of gross earnings replaced by the benefit. In Austria, Chile, Germany, Lithuania and Romania (parental leave only), benefits are calculated based on previous net (post income tax and social security contribution) earnings, while in France benefits are calculated based on post-social-security-contribution earnings. Payment rates for these countries reflect the proportion of the appropriate net earnings replaced by the benefit. Additionally, in some countries maternity benefits may be subject to taxation and may count towards the income base for social security contributions.

Source: OECD (2019), OECD Family Database (website), www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed November 2019).

There is some evidence of the effect of paid leave on children’s cognitive development and educational and labour market outcomes. In Norway, the extension in 1977 of mothers’ paid leave entitlement by four months had a positive effect on school early leaving. Children of mothers who benefitted from paid leave were, on average, 2.7 percentage points less likely to drop out of high school. The effects were even greater for children of less-educated mothers, who were 5.2 percentage points less likely to drop out of high school. In Sweden, the extension of parental leave from 12 to 15 months had no effect on the school achievements of children aged 16 years (Liu and Skans, 2010[92]), while in Germany, evidence on three expansions of the maternity leave system no substantial effects on long-term educational and labour market outcomes, despite the early negative effect the mother’s return to work may have had on children’s behaviour (Dustmann and Schönberg, 2012[93]). The absence of significant long-term effects on children’s outcomes may be due to the fact that children who are not cared for by parents can, in some countries, receive quality early care and education services that have a positive impact on their development, especially for children from the most disadvantaged families (Datta Gupta, 2018[94]).

Paid parental leave can help reduce maternal stress and improve new mothers’ life satisfaction. Several studies find that leave may promote the mental health of mothers following childbirth. For example, at least 15 weeks off work following childbirth has a positive effect on mothers’ self-reported mental health, while at least 20 weeks improves mothers’ ability to perform routine daily activities (McGovern et al., 1997[95]). Similarly, delaying the return to work reduces depressive symptoms, with one week increase in the length of leave associated with as much as a 6-7% decline (Chatterji and Markowitz, 2005[96]). Moreover, having a spouse who did not take any parental leave after childbirth is associated with higher levels of maternal depression (Chatterji and Markowitz, 2008[97]). Evidence on the long-term effects of maternity leave on mental health and life satisfaction is becoming available. Accessing birth-related leave in Germany and the United Kingdom is found to contribute to higher life satisfaction (D’Addio et al., 2014[98]), while more generous maternity leave provision is associated with reductions in the risk of depression in old age

Flexibility in the workplace for parents during their child's early years is especially important to support the development of secure infant-parent attachment. It provides parents with greater opportunity to build this critical relationship with their child, and it helps avoid stressful situations that can harm maternal and/or child’s health. During pregnancy, the job content, working conditions and working schedules may need to be adapted to limit the risks that intense forms of work or exposure to certain working contexts may have on maternal and child health.

Ensure access to health care for children from low-income families and with additional health needs

Ensuring that children from poor families and children with additional health needs have access to adequate health care from an early age facilitates early intervention and saves on future costs. The provision of health insurance to these groups is one support but limited health insurance coverage can leave health care services still unaffordable for families. Evidence from expanded health insurance programmes in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts underlined that for newly enrolled children entering these programmes, being uninsured for a six-month period or more was linked to higher health care needs and higher unmet or delayed care (Hadley, 2003[99]).

The additional barriers that vulnerable families may face in accessing preventative health care need to be considered in programme design. For example, routine interventions such as childhood vaccination programmes are critical foundations for good health for all children, reducing infant mortality, promoting healthy growth and generating significant economic gains for health expenditure savings and the positive effects on human capital formation. Childhood vaccinations also contributes to the prevention of intellectual and physical disabilities, and other large collective externalities that enhance the effectiveness of preventative measures and prevent the failure of curative measure, like increasing antibiotic resistance (Bloom, 2011[100]) (Bärnighausen et al., 2011[101]). Vulnerable families, for instance ethnic minorities, immigrants with poor knowledge of the host country language, poor families, and also children in out-of-home care are more likely to miss or delay childhood vaccinations. Some of the obstacles include limited access to transport, other family and social priorities, poor understanding of need, and in the case of children in out-of-home care difficulties in gaining parental medical consent (Roberts et al., 2017[102]).

Ensure access to adequate nutrition for low-income children and pregnant women have access to adequate nutrition

Food and nutrition programmes can address malnutrition and poor nutrition, especially for families who experience food insecurity. Poorer families are more likely to alter food purchases during difficult times. The United States has substantial experience in nutrition assistance programmes. The available evidence suggests that access to nutrition assistance during childhood can have considerable positive effects, including on subsequent adult health outcomes and on adult economic self-sufficiency (Hoynes, Schanzenbach and Almond, 2016[103]). The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) serves as a gateway to health care by connecting families to resources such as prenatal, obstetric, maternal, and paediatric care; dental care; and counselling for smoking cessation, and drug and alcohol abuse, as well as nutritional assistance. WIC has been associated with mothers giving birth to healthier babies, and to improved access to health care (Carlson and Neuberger, 2017[104]).

There is also some evidence that the receipt of WIC during pregnancy can improve children’s cognitive development and educational achievements (Jackson, 2015[105]). Comparisons of siblings showed that those who benefited from WIC performed significantly better on reading tests, controlling for differences in parental behaviour and family economic circumstances during the child’s first year of life.

Which policies can reduce child income poverty?

Create better quality jobs for working parents and remove barriers to taking up employment

OECD analysis suggests that a broad reduction in child poverty can only be achieved by increasing parental employment and the quality of jobs, supporting maternal employment as well as a stronger redistributive system. On average in OECD countries, slightly less than one in ten families with at least one parent working live below the poverty line, whereas more than six in ten families are income-poor when both parents are not working. Moreover, most countries have their lowest child poverty rates when the poverty rate of two-parent households is at the level of the poverty rate of two-person childless households with the same employment situation.

To make work pay for both parents, tax and benefit systems should provide first and second earners in two-parent families equal financial incentives to work. Enhanced access to affordable all-day childcare is particularly important to facilitate low-income parents to remain in full-time employment, and for mothers to return to work after maternity leave. Yet in many countries, children from low-income families are among the least likely to participate in formal childcare (OECD, 2016[106]).

Removing barriers to employment is crucial, particularly for parents whose health status, family circumstance or low skill levels keep them out of the labour market (OECD, 2011[107]). This requires intensive job placement support, from better tools to profile workers’ skills and support from unemployment caseworkers for hard to-place workers (OECD, 2015[108]). In addition, helping parents in low-income families to improve job skills and access better quality jobs also helps reduce child poverty. Vocational training schemes and financial assistance for training could be targeted at low-skilled parents as a priority and adapted to their family constraints (OECD, 2014[109]).

Ensure social benefits reach the poorest families and those with children with additional needs

Social expenditure seems to have the strongest effect on children poverty when it is earmarked to low-income households. In most OECD countries, the increase in per capita social expenditure over recent decades coincided with a reduction in child poverty. There is some evidence that the association is strongest when the 10% poorest households receive a higher share of total spending. From the mid-1990s until the mid- 2010s, a 1% increase in per capita social expenditure, on average, was associated with roughly a 1% reduction in the relative child poverty rate (Thévenon, 2018[110]). There is, however, no clear association between increases in social spending and poverty rates of jobless families and single-parent families, mainly because the income of these families is often far below the poverty line and cash transfers are not large enough to lift them out of relative-income poverty.

To help low-income families more, countries could decide to intensify the support given, by either increasing spending or by reallocating family cash benefits, or both. In times of public spending constraints, reallocation of cash benefits is an option that keeps social expenditure constant. Under these conditions, substantial decreases in child poverty rates can be achieved through more targeted coverage of poor children (OECD, 2018[111]).

Figure 4.3. Child poverty rates following a reallocation of family and/or housing benefits

Note: The chart shows the estimated child poverty rates that would follow a reallocation of family and/or housing benefits to poor families, keeping constant the total expenditures on family and housing benefits. The first group consists of countries for which the lowest child poverty rate is achieved by redistributing housing allowances to cover all poor children; group 2 corresponds to countries where the lowest rate is achieved by redistributing family allowances or the sum of family and housing allowances. Countries are ranked in each group according to the lowest poverty rate obtained in the best case scenario.

Source: OECD (2018), “Poor children in rich countries: why we need policy action”, Policy Brief on Child Well-Being, www.oecd.org/els/family/publications.htm.

In most OECD countries, family benefits and/or housing benefits are distributed to all families, or to a much larger segment of families than those categorized as income-poor. In these conditions, a re-allocation of benefits towards only income poor children implies that a smaller number of children would receive much larger family transfers, resulting in a reduction of child poverty. Nevertheless, how this outcome can be best achieved varies across countries. In some countries, the redistribution of family allowances could be very effective, while in others, a greater reduction in child poverty could be achieved by improving the distribution of housing benefits (Figure 4.3).