The assessment and recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Denmark. The 44 recommendations are intended to help Denmark make further progress towards its environmental policy objectives and international commitments. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance reviewed and approved the assessment and recommendations at its meeting on 25 April 2019. Actions taken to implement selected recommendations from the 2007 Environmental Performance Review are summarised in the Annex.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Denmark 2019

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1.1. Environmental performance: Trends and recent developments

Denmark’s1 population enjoys a very high living standard, one of the lowest income inequality levels in the OECD and strong life satisfaction (OECD, 2017[1]; OECD, 2019[2]). Denmark outperforms the OECD average on most Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It has made good progress in decoupling environmental pressures from economic activity. Denmark significantly reduced its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions over the review period, further progressing in the decarbonisation of its economy. Levels of energy and carbon intensity were among the lowest for International Energy Agency countries in 2017 (IEA, 2018[3]; IEA, 2017[4]). The use of cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis continues to guide environmental policy making.

Despite this progress, Denmark continues to face environmental challenges. In particular, a significant portion of the population of large Danish cities remains exposed to PM2.5 levels above World Health Organization standards. Denmark will struggle to meet its target of reducing ammonia emissions, set by European Union (EU) legislation, by 2020. Biodiversity is under pressure in many regions, with a large number of red-listed species, a poor state of conservation of natural habitats and low connectivity of ecosystems. Water quality needs to be improved, especially with regard to the presence of pesticides in groundwater and the ecological status of rivers, lakes and coastal waters.

1.1.1. The country has made progress in decarbonising its economy, with the energy sector playing a key role

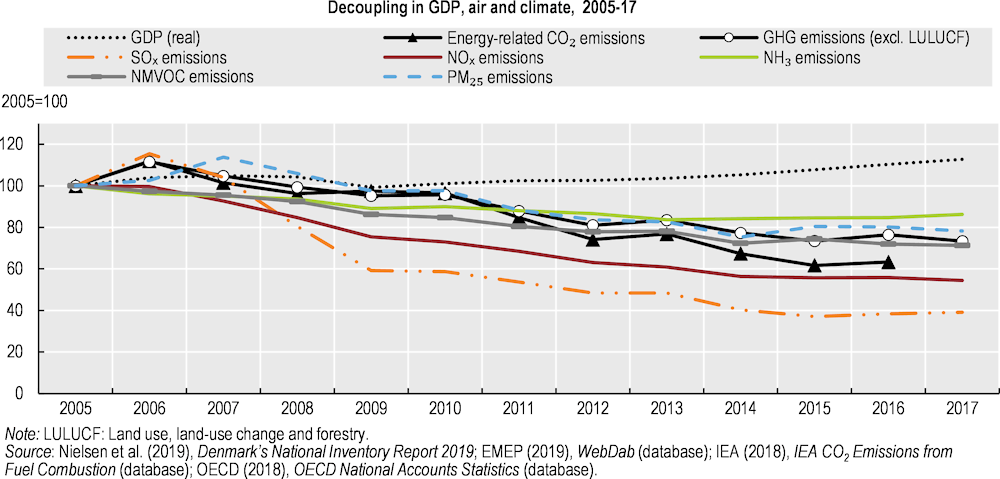

Over the review period, Denmark decoupled energy-related CO2 emissions, GHG emissions and emissions of major air pollutants from growth in gross domestic product (GDP) (Figure 1). The contribution of fossil fuels to total primary energy supply (TPES) dropped significantly, from 82% in 2005 to 60% in 2017.

Figure 1. Denmark has decoupled emissions of GHGs and major air pollutants from GDP growth

The energy intensity of the economy is among the lowest in the OECD and continued to decline over the review period. Energy consumption decreased by 8% between 2005 and 2016. It fell in all sectors except residential, where it remained relatively unchanged. The largest decrease was in the industry sector (25%). The residential and transport sectors are the largest energy consumers, each accounting for one-third of total consumption in 2016 (IEA, 2018[3]).

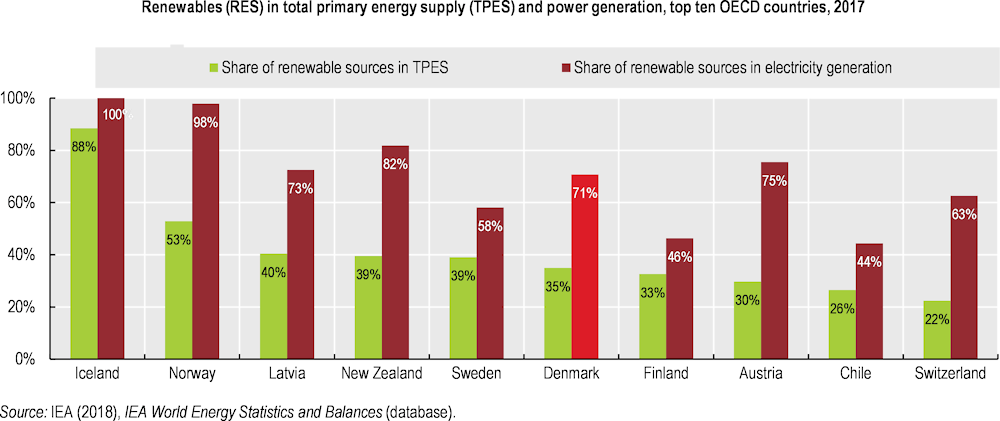

Denmark is one of the leading OECD countries in terms of share of renewable energy sources in TPES, even though its hydropower potential is not comparable to other leading countries (Figure 2). Bioenergy and wind have largely replaced coal in power generation. By 2016, Denmark had already met its 2020 renewables target of 30% of gross final energy consumption. However, bioenergy’s predominant role in the renewables mix raises the issue of environmental sustainability of supply (OECD, 2018[5]), all the more so since Denmark imports nearly half its solid biomass, more than any other OECD country using this resource.

Figure 2. Denmark is one of the leaders in use of renewable energy sources

1.1.2. Denmark has stepped up its efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and is preparing for carbon neutrality by 2050

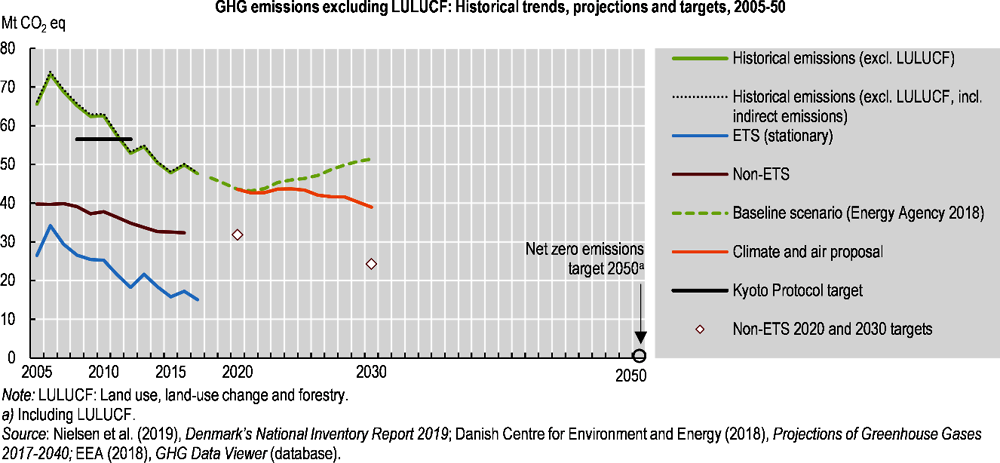

Between 2005 and 2017, Denmark reduced its GHG emissions by 27.7% (Nielsen et al., 2019[6]) (Figure 3). In June 2018, the government and all parties in the Folketing (the Danish Parliament) agreed a new set of measures to be introduced over 2020-24. This Energy Agreement aims for a 55% share of renewables in primary energy supply by 2030 (Government of Denmark et al., 2018[7]). It specifies that, by 2030, renewables are to cover all final electricity consumption – or even more, allowing for net exports to the European grid – and electricity production from coal is to be phased out. Most of the GHG reductions envisioned in the agreement, totalling 10-11 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (Mt CO2 eq), are covered by the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).

In 2016, emissions covered by the EU ETS accounted for one‑third of Denmark’s GHG emissions. Between 2005 and 2017, EU ETS emissions from stationary sources decreased by 43%, well above the EU average of 14% (EEA, 2018[8]; Nielsen et al., 2018[9]). The reduction followed a proactive policy supporting diffusion of renewables, partly financed by an allocation of revenue from the electricity tax paid by Danish households. Under the Energy Agreement, feed-in tariffs will be replaced by technology-neutral one-off investment grants in a move to solutions that are more responsive to changing market conditions. Some DKK 4.2 billion (EUR 564 million) is to be allocated for this purpose from the state budget for 2020‑24.

Figure 3. More measures to reduce GHG emissions are needed if Denmark is to achieve its long-term goal

The EU Effort Sharing Decision commits Denmark to reduce its non-EU ETS emissions by 39% from the 2005 level by 2030. This is one of the most ambitious reduction targets in the EU. Between 2005 and 2017, non-ETS emissions decreased more slowly than EU ETS emissions, by 18% (Eurostat, 2019[10]). Under the Effort Sharing Decision Denmark has chosen for the sake of cost-effectiveness to rely on flexibility mechanisms to achieve the 39% target. Two-thirds of the GHG reductions it envisions for non-EU ETS emissions, about 21 Mt CO2 eq, are to be achieved through credits in the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector and one-third by cancellation of EU ETS quotas.

In October 2018, the government prepared a climate and air proposal, Together for a Greener Future, to reduce non-EU ETS GHG emissions (and air pollutants). Among other measures, it proposes halting sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 and supporting research and development (R&D) to develop low-GHG farming (EUR 12 million) and carbon capture and storage on farmland and in forests (EUR 14 million). Measures approved in the Finance Act for 2019 include an increased premium for scrapping old diesel cars, grants for investing in low-carbon barn technology and research on better estimating carbon sequestration in soil and forests. To help reach a goal of 1 million electric vehicle sales by 2030, electric and plug-in hybrid cars below DKK 400 000 (EUR 54 000) are exempt from the registration tax in 2019 and 2020, and the government has established a transport commission, giving the municipalities the option to offer cheaper and prioritised parking of green vehicles and allowing them to drive in bus lanes. The Energy Agreement and climate and air proposal are key steps for Denmark to make its economy climate-neutral by 2050, in line with the long-term EU strategic vision.

1.1.3. Particle pollution in cities and agricultural ammonia emissions remain problems

Denmark is on track to meet its 2020 targets under the EU National Emissions Ceilings (NEC) Directive for nitrogen oxides (NOX), non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) and sulphur oxides (SOX). It will be more difficult for it to meet its NEC commitments for 2020 and 2030 on fine particles (PM2.5) and ammonia (MEF, 2019[11]). Domestic steps to improve urban air quality include low-emission zones in major cities, registration tax exemption for electric cars, particle filters for new fossil-fuelled cars and enhanced emission limit values for residential wood stoves. Measures have also been taken to reduce ammonia emissions, such as banning manure application by splash plate and a requirement to roof slurry tanks.

Denmark submitted its NEC implementation programme, the National Air Pollution Control Programme, to the European Commission for approval in April 2019. It proposes measures to reduce ammonia emissions, such as financial support for low-emission barns and regulation of urea-based chemical fertilisers. The proposed measures to reduce PM2.5 focus on cleaner transport and accelerated replacement of old residential wood stoves.

The number of premature deaths caused by ambient air pollution continues to be above the OECD average (Figure 4). The Danish Center for Environment and Energy at Aarhus University estimates that 3 200 premature deaths a year are attributable to air pollution, including transboundary pollution, with exposure to PM2.5 implicated in 90% of cases (Ellermann et al., 2018[12]). The welfare cost related to PM2.5 exposure is estimated at 3% of GDP (OECD, 2018[13]).

Figure 4. Good air quality remains a challenge

1.1.4. More coherent and proactive policies are needed to foster nature conservation

The 2014 Biodiversity Strategy does not include targets for protected areas. The vast majority of open habitats (i.e. natural areas with no tree cover and additionally most freshwater lakes), about 10% of the country’s area, are included in Section 3 of the Nature Protection Act, which gives them general protection against activities that can have a direct negative impact on their integrity. This does not mean, however, that some extensive farming practices cannot continue. The area of Section 3 habitats increased by 9% in 2006‑16 (EPA[14]).

Until 2008, Denmark had no national parks. Five have since been created, parts of which are privately owned. The national parks are established by assignment agreements and managed at the local level. Their management imposes regulation on specific activities within the parks by designating different planning zones.

The 2016-19 Nature Package envisages increasing the area of “biodiversity forests” from 11 700 ha in 2016 to 28 300 ha in 2066, mainly in state-owned forest. By January 2019, 22 800 ha had been designated in state-owned forests. “Biodiversity forests” have a stricter biodiversity protection target than other forests and have less intensive or no management. The new National Forest Programme, adopted in 2018, builds on the objectives of its predecessor: i) increase forest cover to 20-25% of the land by the end of the century (it is now less than 15%) and ii) make protecting biodiversity the main goal for 10% of all forests by 2040.

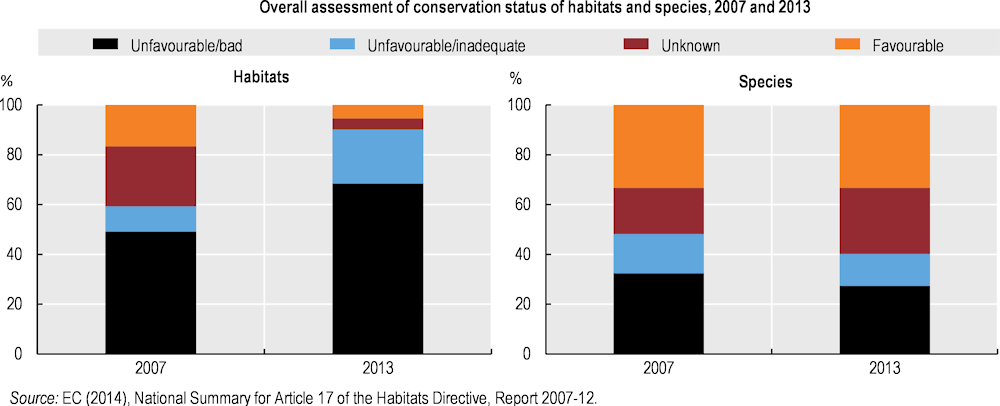

Natura 2000 sites cover some 8% of the land area and 18% of the exclusive economic zone. However, 68% of the total area of habitats and 27% of species covered by the EU Habitats Directive are in unfavourable or bad conservation status (Figure 5), and 27% of assessed plant and animal species are red-listed.

Figure 5. The state of most habitats remains unfavourable

Amendments to the Planning Act in 2015 and 2017 require municipalities to designate the location of areas of special nature protection interest on a map, including Natura 2000 areas on land and other protected natural areas as well as ecological corridors, potential natural areas and potential ecological corridors. The complete designation constitutes the Green Map of Denmark. Preparation of the Green Map is a key element of Danish nature conservation policy. The map should enable targeting of municipalities’ nature protection initiatives. It will be developed gradually as municipalities revise their land-use plans. Once designated, it will provide a clearer picture of the extent and location of existing and potential areas of special nature protection interest and indicate where to create such areas and corridors to link them.

Danish reporting to international organisations has overestimated the number of protected areas compliant with the standards of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Thus any comparison with the Aichi targets under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is distorted. For example, it would appear that the total number of IUCN‑compliant areas protected by specific conservation orders is of the order of 400, rather than the 1 843 previously reported under the CBD. The Ministry of Environment and Food (MEF) estimated in April 2019 that 15% of the land area in Denmark is protected in accordance with the Nature Protection Act or Natura 2000, or both.

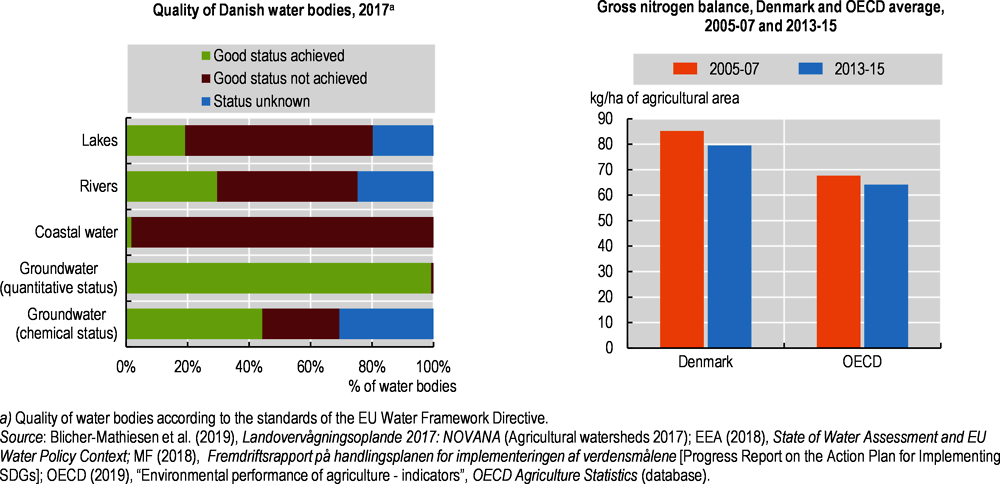

Many water bodies do not achieve the good ecological status required by the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD). This is particularly true of coastal waters, the vast majority of which do not achieve the goal (Figure 6). Measures under the 2005-09 Action Plan for the Aquatic Environment III and 2009-15 River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) helped reduce the agricultural nitrogen surplus by 7% between 2005-07 and 2013-15, though it remains above the OECD average (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The quality of coastal waters is of concern and the agricultural nitrogen surplus remains above the OECD average

To achieve the WFD objectives, Denmark needs to reduce nitrogen discharges to coastal waters to 44 700 tonnes a year by 2027, compared with around 60 000 tonnes in 2013-15. To this end, EUR 830 million, just over half the 2015-21 RBMP budget, is devoted to coastal water protection (wetland creation, afforestation, farmland set-asides, catch crops, ecological focus areas where agricultural production is prohibited), a third goes to wastewater treatment and the remaining 13% is related to lake and river restoration.

The 2015 Food and Agriculture Package introduced a policy shift towards more cost‑effective “targeted regulation”. Until 2017, Denmark had a regulation where the same rules applied to all farmers. With the targeted catch crops programme from 2017 and targeted regulation from 2019, Denmark has implemented a differentiated system. The targeted regulation is based on water pollution risk. This is a step in the right direction, as it improves cost-effectiveness by focusing efforts on vulnerable areas, in line with the spirit of the WFD and the EU Nitrates Directive. Targeted regulation aims to focus on watersheds threatened by nitrogen pollution, leaving farmers in other watersheds more flexibility in managing the use of their nutrients than was the case with non-targeted regulation (MEF, 2015[15]).

The intensity of agricultural pesticide use is below the OECD average in terms of sales. However the presence of pesticides and their metabolites in groundwater remains a concern. In 2015-17, prohibited (legacy) pesticides were detected in groundwater intended for human consumption at levels exceeding the limit value for drinking water of 0.1 μg/litre in 7.2% of the 1 086 intakes studied. By comparison, authorised pesticides and their metabolites were detected at levels exceeding the limit of 0.1 μg/l in 1.6 % of these intakes (GEUS, 2019[16]). In 2019, municipalities were asked to demarcate protection zones around drinking water wells and enforce them using voluntary approaches. If this proves ineffective, from 2022 a political agreement concluded in 2019 reserves the right to impose pesticide-free agriculture in the protection zones. Some water companies have taken the lead in deciding to pay farmers not to use pesticides in the areas concerned.

Recommendations on climate, air, biodiversity and water

Mitigating climate change

Make every effort to achieve the goal of further reducing GHG emissions by 2030, including identifying misalignment of sectoral policies with climate policy, mobilising private finance and seeking synergies with other environmental policies (on air, water, waste, biodiversity).

Develop a vision for a carbon-neutral Denmark by 2050, considering the development and export promotion of technological solutions (for energy efficiency, renewables, and carbon capture and storage) and cost-effectiveness (including using international carbon markets to offset emissions).

Improving air quality

Redouble efforts to reduce ammonia emissions so as to achieve the 2030 target set by the NEC Directive; in particular, seek synergies with nitrate policies, taking into account the nitrogen cycle; ensure policy coherence between ammonia emission management and expansion of biogas as a renewable energy resource.

Continue efforts to address urban PM2.5 pollution, including reducing particle emissions from residential wood burning.

Strengthen international co‑operation to support Denmark’s efforts to control transboundary air pollution from international ship traffic.

Addressing biodiversity

Update the 2014 Biodiversity Strategy in light of initiatives put in place since its launch (e.g. Nature Package, National Forest Programme, Rural Development Programme, Green Map), and ensure their coherence; pending development of the Green Map by 2050, set intermediate targets for protected areas and connectivity, taking into account progress on the CBD Biodiversity Strategic Plan 2021-30.

Provide sufficient public financial support to achieve the goal for “biodiversity forests” on both state-owned and private land; evaluate their impact, as well as that of the policy of increasing forest cover, on carbon sequestration.

Establish a natural area connectivity strategy targeting threatened species, in close partnership with civil society and municipalities.

Improving water quality

Continue to improve the cost-effectiveness of measures to reduce nitrate pollution of coastal waters; in particular, continue to implement the targeted regulation, focusing on watersheds at risk; estimate the effects of this targeted regulation on N2O emissions with a view to seeking synergies.

Improve the effectiveness of voluntary approaches to farmers in preventing pesticide use around drinking water abstraction wells; in particular, incorporate the suggestion that additional instruments will have to be applied if the objective of pesticide-free areas is not achieved.

1.2. Environmental governance and management

Denmark has a well-functioning environmental governance and management system. It is characterised by high levels of co‑operation and consensus. Particular assets include an informal system of cross-party political agreements, strong participation by civil society in policy making and high-quality independent advisory bodies. Denmark also benefits from expertise in socio-economic assessment of policies at its universities and in ministries. Finally, it has a comprehensive risk-based inspection system in place.

There is scope to use the existing expertise in socio-economic assessment more systematically in policy making. Despite the strong risk-based inspection system, analysis of non‑compliance among companies is limited. Given the important responsibilities of municipalities, strengthening their capacity, including by sharing expertise, in domains and regions where they face environmental problems must be a priority, along with ensuring that environmental rules are applied in comparable ways countrywide.

1.2.1. Municipalities are responsible for most aspects of environmental management

In Denmark’s environmental governance and management system, many responsibilities are devolved to the municipalities. The national level sets the legal framework and provides guidance on implementation. It also develops national plans, programmes and strategies. Inter-ministerial co‑ordination on environment-related policies at the central level is well established. Following a landmark reform of the local government structure in 2007, Denmark’s 98 municipalities became responsible for most aspects of environmental management. This is consistent with a tradition of municipal autonomy, enshrined in the Constitution. Municipal responsibilities include municipal and local planning; implementation of policies, plans and programmes; the issuance of most environmental permits; and related inspections. National authorities retain oversight on environmental permits and inspections for the most complex and potentially harmful companies. The five regions have limited environmental responsibilities, which the government has proposed to abolish.

As the 2007 OECD Environmental Performance Review (EPR) recommended, task forces were set up to help build municipal capacity following the 2007 reform. The introduction of management planning at river basin level in 2009 improved inter‑municipal co‑operation in water and nature management. More generally, municipalities share expertise and best practices through Local Government Denmark, an association to which all municipalities belong. Denmark should expand the use of task forces to areas where it faces challenges, such as waste prevention (Section 4). Further guidance on implementation of environmental legislation could be strengthened by learning from international best practice, e.g. Switzerland’s “enforcement aids” to its cantons.

1.2.2. Expertise in socio-economic assessment is extensive, but could be used more systematically

Denmark has a good record on the speed and quality of transposition of EU environmental legislation. The number of complaints and infringement cases is low. To enhance political stability and policy continuity, the government often seeks to form political agreements with parties outside government. This system is a major asset for the country. It has helped bring about positive long-term change, such as stable investment in renewables.

Direct environmental regulation is still the most widely used policy instrument. However, Denmark increasingly favours direct regulation based on results rather than requiring specific practices, e.g. in its targeted approach to nitrogen regulation of farms. This gives producers flexibility on how to comply and improves cost-effectiveness (OECD, 2018[17]). Environmental impact assessment is an integral part of the permitting process.

The EU Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA) Directive was transposed into Danish law in 2004. SEAs were conducted on changes to rules on farmers’ fertiliser use under the 2015 Food and Agriculture Package and on the siting of offshore windfarms, among other things. Important government plans and programmes typically rely on extensive prior assessment of the cost and benefits of targets or the cost-effectiveness of measures. Denmark also implemented a recommendation in the last EPR by prioritising monitoring of national environmental action plans in its national monitoring programme, NOVANA. Advisory bodies, such as the Environmental Economic Council and the Climate Council, evaluate public policies ex post and make ex ante recommendations with a strong focus on improving cost-effectiveness. An independent body, Rigsrevisionen, audits public spending on behalf of Parliament.

In 2017, the government revised guidelines on socio-economic impact assessment (SEIA). Making SEIA mandatory on government decisions that would have a significant environmental impact could further enhance the quality of policy making. It would also allow strengthening of regulatory impact assessment (RIA) of draft laws, which have not always been subject to SEIA (OECD, 2018[18]). In addition to effects within its borders, Denmark should consider separately quantifying the effects of its environmental policies in other countries – such as health benefits in neighbouring countries resulting from Danish air pollution measures – and taking them into account in RIA (OECD, 2018[19]).

1.2.3. Land-use planning should target better distribution between agriculture and nature protection

Municipalities are responsible for translating national guidelines into concrete spatial planning. Municipal plans are issued every 4 years and have a 12 year time frame. Local plans are the most detailed level of spatial planning. They establish rules on how land in a local area can be used and developed (OECD, 2018[19]). Spatial planning must take into account existing and potential natural areas designated on the Green Map. The aim is to improve biodiversity by reinforcing efforts to establish larger and more interconnected natural areas and ensure coherence between designations in neighbouring municipalities.

Farmland takes up more than 60% of the surface area and puts pressure on the environment, especially on peatlands (drained peatlands become net GHG emission sources) and near sensitive natural areas and water bodies. Since 1990, land consolidation and land banking have proved essential in improving both agricultural productivity (through structural adjustment) and nature conservation (by offsetting nature conservation land banked with farmland) (Hartvigsen, 2014[20]). However, public funding for land redistribution has been significantly reduced since the structural adjustment policy was discontinued in 2006. In 2018, a Multifunctional Land Redistribution Fund (MLRF) was established with a budget of EUR 33 million. In February 2019, Denmark’s two main environmental and agricultural interest groups jointly recommended raising the fund’s budget by at least EUR 130 million (Danish Society for Nature Conservation and Danish Agriculture & Food Council, 2019[21]). The aim is to be able to seize opportunities to buy land where farming has a significant environmental impact – e.g. peatlands, farms near ammonia-sensitive nature areas or drinking water wells – and convert it to natural areas or grasslands as well as to support rural development and access to landscapes and nature. This would support Denmark’s ambition to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. It would also deliver co‑benefits on biodiversity, water and air quality, and climate adaptation. However, determining the merits of scaling up public funding of the MLRF with respect to expected environmental policy benefits requires cost-effectiveness analysis.

In addition to budgetary resources, private funds could be mobilised to finance the MLRF. Denmark has already shown leadership in this area through the Climate Investment Fund. Recent OECD work illustrates the range of interventions public actors can use to attract institutional investment in low-carbon infrastructure, which could include the land purchases envisaged by the MLRF (Röttgers, Tandon and Kaminker, 2018[22]).

1.2.4. The environmental inspection system is effective, but enforcement is uneven

Denmark applies a risk-based approach to environmental inspections, in line with the EU Industrial Emissions Directive. It assigns a risk score to companies based on five parameters. The most potentially harmful companies are inspected at least every three years, while the least potentially harmful are inspected at least every six years. Denmark applies a risk-based inspection system even to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which is good practice. In a positive step, a national inspection database called Danish Environmental Administration was set up in 2016. Inspection data from 2017 indicate that the system is effective in finding violations. They also show that the companies posing the biggest potential risks to the environment are subject to the most compliance promotion and enforcement measures. Denmark is starting to use the database more strategically to improve its inspection efforts. From 2020, it plans to target guidance to industries where inspection data point to a need for special efforts to reduce the number of violations. Making fuller use of the database should help Denmark gain a better understanding of non‑compliance among companies and inform policy making.

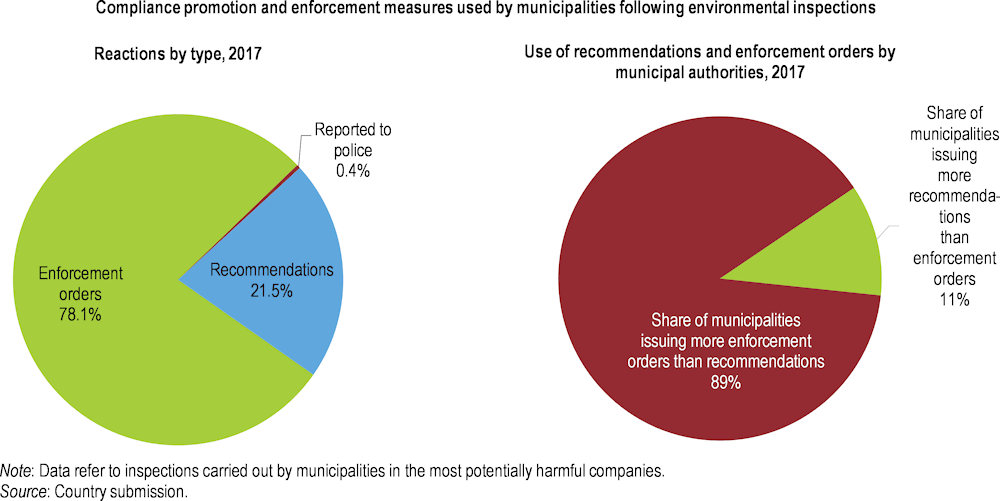

Authorities have three categories of compliance promotion and enforcement measures at their disposal: reporting companies to the police, issuing enforcement orders to prescribe corrective actions and making non‑binding recommendations. Recommendations can take the form of an agreement between authorities and companies on specific improvements to be undertaken. Guidance documents on the use of compliance promotion and enforcement measures have existed since 2005 (EPA, 2005[23]), but in practice, municipalities vary in which measures they use and to what degree (Figure 7). In 2017, recommendations made up 21.5% of all reactions recorded following inspections of the potentially most environmentally harmful companies. However, 11% of municipalities have opted for a more instructive (less punitive) approach by choosing recommendations more often than enforcement orders. Eight municipalities issued five times as many recommendations as enforcement orders.

Figure 7. Compliance promotion and enforcement vary across municipalities

To create a level playing field for companies, national authorities should ensure that municipalities promote compliance with environmental rules and enforce them in a comparable manner (Mazur, 2011[24]) while respecting municipal autonomy and taking differences in the regional distribution of industries into account. In 2017, the MEF launched a new enforcement strategy for its agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The strategy includes scaling up guidance efforts and ensuring transparent and uniform treatment of companies. The results of the strategy should be used to give municipalities additional, evidence-based criteria for identifying appropriate compliance promotion and enforcement measures. In addition, the EPA could illustrate its guidance documents with examples from actual cases in municipalities.

No environmental police or environmental courts exist. Regular police and courts are essentially responsible for imposing fines if violations are reported. However, as municipalities rarely report companies to the police (Figure 7), fines are seldom used. This may indicate that the level of fines is high enough that companies do not expose themselves to the risk of violating environmental legislation. It may also indicate that companies take seriously the possibility of municipalities escalating the choice of compliance promotion and enforcement measures should violations not be corrected (OECD, 2009[25])

Denmark does not have an environmental code. In 2017, a panel of legal experts recommended simplifying the structure of environmental legislation while keeping the current level of protection. It estimated that the number of environmental laws could be reduced from 95 to 43. Initial steps have been taken to follow up on the panel’s recommendations. For example, obsolete rules on agriculture were repealed. Denmark should pursue such efforts to simplify its environmental legislation further in order to promote compliance and enforcement.

Voluntary environmental agreements and formalised partnerships between the public and private sectors are in place. When agreements include quantitative targets, they are backed by the explicit possibility of regulatory action, in line with OECD best practice (OECD, 2003[26]).

1.2.5. Environmental democracy is strong

Public participation in environmental matters is excellent. The Environmental Information Act implements the UNECE Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (the Aarhus Convention). The act has a broad scope of application. The ombudsman of Parliament, a citizens’ watchdog, has contributed to this by issuing opinions on public authorities’ use of the act.

In the absence of environmental courts, an appeal board of judges and experts serves as the first instance of redress for citizens and associations against administrative decisions in the environmental field. From 2011 to 2015, it reduced its average processing time for complaints from 369 days to 182, making access to justice quicker. The trend was partly reversed in 2016 when the board was relocated.

Danish authorities use information campaigns to raise public awareness of environmental issues. In recent years, initiatives have been taken to help elementary schools educate children on environmental issues such as the SDGs, climate change, biodiversity and food waste.

Recommendations on environmental governance and management

Supporting the institutional framework

Expand the use of task forces to build municipal capacity in the areas of environmental management where they face challenges, such as waste prevention.

Further strengthen guidance to municipalities on implementation of environmental legislation to make it easier to use, as Switzerland does with its enforcement aids to cantons.

Making land use more sustainable

Evaluate the cost-effectiveness of scaling up land acquisition and redistribution of environmentally valuable agricultural land through the MLRF.

Strengthening policy evaluation framework

Consider making SEIA mandatory for government policy decisions with a significant environmental impact, including in the context of RIA, based on the 2017 SEIA guidelines.

Consider separately quantifying effects in other countries when conducting cost‑benefit analyses of Danish environmental policies, e.g. health benefits in neighbouring countries resulting from Danish air pollution measures.

Promoting and ensuring compliance

While respecting municipal autonomy, create a level playing field for companies by ensuring that municipalities apply compliance promotion and enforcement measures based on well-established and similar criteria; in particular, update the EPA compliance promotion and enforcement guidance documents with factual findings from the enforcement strategy and concrete examples from municipalities.

Continue efforts to make fuller use of the Danish Environmental Administration database on environmental inspections to gain better understanding of non‑compliance among companies and to inform policy making.

Pursue efforts to simplify environmental legislation to further promote compliance and enforcement.

1.3. Towards green growth

1.3.1. Ambitious targets for green growth and commitment to sustainable development

Green growth ranks high on Denmark’s political agenda. The country aspires to achieve 100% green electricity by 2030 and net zero GHG emissions by 2050. It is one of the first countries to implement a green energy strategy based on a broad political agreement, which helps create a climate of trust for investors. The commitment to address environmental challenges while ensuring economic success through clean technology exports has made Denmark a pioneer of green growth. Exports and revenue from the Danish clean tech industry will become increasingly important for the economy as production and associated revenue from oil and gas extraction decline.

Denmark’s green growth policy increasingly aims for cost-effectiveness in achieving environmental objectives while ensuring that measures benefit employment and competitiveness. This is reflected in the recently adopted Energy Agreement for 2020-24. Pending transition to electric vehicles and development of mitigation technology for agriculture, Denmark has chosen to make significant use of flexibility mechanisms to achieve its ambitious goal of reducing GHG emissions outside the EU ETS (Section 1). Reaching carbon neutrality by 2050 requires continued investment, R&D in low-carbon technology, and options such as carbon capture and storage and carbon sequestration.

Policy making benefits from engagement of stakeholder and expert groups, which are frequently consulted on major policy initiatives. Denmark played a leadership role in the development of Agenda 2030 and was among the first countries to conduct a voluntary national review on progress towards SDGs. Efforts should continue to broaden the statistical base for SDG reporting and to harmonise key indicators with international ones. A comprehensive report on Green National Accounts for Denmark was published in 2018, comprising information on the natural resource stock, resource use and resulting pollution, and green economy aspects. It could be the basis for regular reporting on green growth.

1.3.2. In a long history of green taxation, adjustments are still necessary

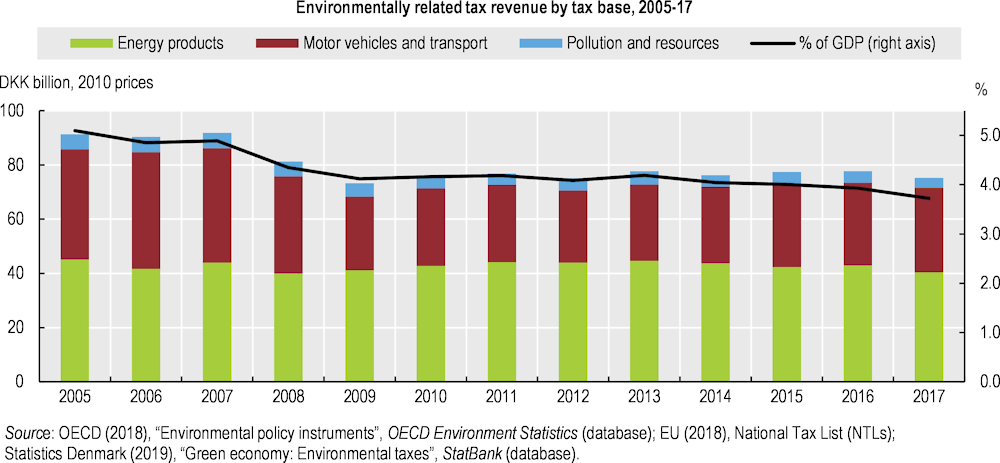

Denmark’s public finances are strong. The country is known for balanced budgets and low public debt levels. The tax burden is high: in 2017 Denmark ranked second among OECD countries for tax/GDP ratio, after France. While revenue from environmentally related taxes has declined in real terms over time (Figure 8) because of a decrease in revenue from motor vehicle registration taxes (mostly due to deductions to fuel efficient cars), it still equalled 3.7% of GDP in 2017, the highest share among OECD countries and more than twice the OECD average.

Denmark is a pioneer in carbon pricing. Nearly all energy-related CO2 emissions face a price signal, except those from burning of woody biomass for heating. The use of bioenergy is assumed to be carbon neutral, in line with EU renewables policy. Overall, 32% of emissions faced a price above EUR 30 per tonne of CO2 in 2015, which is similar to the OECD average.

Figure 8. Environmentally related tax revenue has declined

Taxes on energy imposed on households, like other environmentally related taxes, are generally much higher than those imposed on businesses, for reasons of competitiveness. The ordinary household electricity tax is the most extreme example: it is some 200 times higher than the rate on manufacturing, etc., making it the highest in the European Union. Denmark has had a deliberate policy of allocating revenue from an additional tax on electricity consumption (the Public Service Obligation, PSO, introduced in 2012) to development of renewables, on a kind of “electricity pays for (renewable) electricity” principle. Although this has disadvantages from a macroeconomic point of view (for example, it limits budgetary flexibility), it has proved effective in supporting wind energy deployment. Without this investment subsidy, combined with feed-in tariffs, the rapid deployment of wind energy technology, and reduction in production costs, would not have been possible.

The new Energy Agreement still provides for wind energy investment subsidies. As the PSO is phased out over 2017‑21, the aim is to lower electricity taxes and finance subsidies to wind and other renewables from the general budget. The government’s plans to reduce electricity taxes will encourage more people to abandon fossil-fuelled and wood stove heating. The Energy Agreement also gradually reduces the electricity tax on electric heating in a bid to make this option more attractive than fossil fuel and biomass solutions, while reducing the tax burden.

In the context of overall high energy taxes, exemption of woody biomass from the energy duty and CO2 tax has led to a boom in its use in cogeneration of heat and electricity. However, high reliance on woody biomass is problematic if it leads to unsustainable forest management, including in third countries (almost half the biomass used is imported). Energy utilities have put in place a voluntary programme to ensure sustainable use of biomass, which includes sustainable management of the forests from which the biomass is derived.

As in many other OECD countries, petrol is taxed significantly more heavily than diesel, which is not justifiable from an environmental perspective. Rather than raising diesel taxes, Denmark applies an annual countervailing charge on private diesel cars (in addition to the registration and annual vehicle taxes) in a bid to avoid fuel tourism to neighbouring countries. However, the charge does not fully offset the low diesel tax, notably for cars driving above‑average distances per year. Thus, the charge has not eliminated the effect of the diesel differential. Most trucks, buses and tractors are exempt from the charge or pay a relatively low rate. Denmark would benefit from phasing out the reduced energy duty for diesel, especially if it co‑ordinated the phase-out with similar moves in neighbouring countries. End‑user prices for diesel are lower in Germany, although higher in Sweden and Norway.

Vehicle ownership is heavily taxed, mainly through the high registration tax. This has led to a relatively low vehicle ownership rate, but has also discouraged renewal of the car fleet: passenger cars in Denmark average 8.9 years, above the EU average (EEA, 2018[27]). The registration tax is differentiated by vehicle fuel consumption. The requirements became more stringent in 2017. The annual vehicle tax is also based on fuel efficiency. Both taxes have been effective in encouraging purchases of fuel-efficient cars. The gradual abandonment of exemption of electric vehicles from the registration tax, combined with a reduction in the rate for all vehicles, led to a drop in electric vehicle sales between 2016 and 2018. Hence it was decided to reinforce the fiscal advantage, at least for 2019 and 2020. Denmark should consider additional measures to support the diffusion of electric vehicles, such as interoperable charging stations (each of the three main operators has its own membership system) or free access to bus lanes, as provided for in the climate and air proposal.

Shifting vehicle taxation from ownership to use would enhance environmental effectiveness. The government has reduced the registration tax several times in recent years while the annual vehicle tax has been increased. These changes have not been accompanied by an increase in the fuel tax or introduction of tolls (other than existing tolls on two bridges and Eurovignette for vehicles over 12 tonnes). Reducing the tax burden on vehicles can have a rebound effect, as fleet expansion reverses the emission reductions achieved by increasingly fuel-efficient cars. Plans in 2012 to introduce a congestion charge in Copenhagen have been replaced by an air quality protection plan to reduce particle and NOX pollution. For the past ten years, Denmark’s four largest cities have been implementing low-emission zones to limit diesel truck traffic in city centres. Only trucks that meet the Euro 4 (since 2010), Euro 5 (from 2020) and Euro 6 (from 2022) standards can circulate. Trucks are not subject to registration tax. The current taxation of trucks fails to internalise the external environmental costs. Previous attempts to internalise such costs (e.g. through road tolls per kilometre driven on certain roads) have been abandoned because they were considered very costly. Public spending on rail has increased considerably to modernise network signalling (DKK 20 billion, EUR 2.7 billion) and electrify the railway (DKK 7 billion, EUR 0.9 billion). Announced in March 2019, a new political agreement on infrastructure investment envisages increasing railway investment in coming years to DKK 51.5 billion (EUR 6.9 billion). In addition, there are plans to buy new electric trains, which could cost as much as DKK 20 billion (EUR 2.7 billion).

The climate and air proposal plans to reduce GHG emissions in non-EU ETS sectors. Its ambition is for all new cars from 2030 onwards to be low- or zero-emission vehicles. A commission for a green transition of all passenger cars has been asked to deliver a strategy on how this ambition can best be realised while maintaining adequate revenue. Meanwhile, a partnership between the government and two large agricultural organisations was established to co‑ordinate R&D on GHG mitigation techniques in agriculture and ways to encourage such techniques, in synergy with techniques and policies for managing nitrates and ammonia.

However, Denmark taxes NOX and SOX emissions at rates below the indicative values used by MEF for cost-benefit analysis. Its landfill and waste incineration taxes have reduced the amount of waste going to landfill but not the amount for incineration (Section 4). Nevertheless, it is one of the few countries to tax pesticides, and in 2013 it went from a retail value tax to one that reflects health and environmental risks (Section 5). It and the Netherlands were the first countries to regulate nitrogen and phosphorus excess through a quota system at the farm level.

Denmark and the EU co-finance a Rural Development Programme (RDP), under which DKK 1.1 billion (EUR 148 million) a year was spent on environment-related agricultural activities in 2015-19, including green investment in farms, organic farming and protection of nature and water quality. Payments for protection of the aquatic environment increased from EUR 30 million to EUR 100 million over the period, while payments for biodiversity protection remained in the range of EUR 30 million to EUR 50 million. Farms that convert agricultural peatland to nature areas lose income support under the EU Common Agricultural Policy. Denmark thus decided to compensate farmers converting peatland into nature areas, spending DKK 65 million (EUR 8.7 million) annually in 2016‑19. Denmark should evaluate the side effects of the RDP measures on GHG emissions with a view to seeking co-benefits. For example, conversion of peatlands could reduce some 15% of agricultural GHG emissions through carbon sequestration (Dubgaard and Ståhl, 2018[28]). Incentives could also be developed to mobilise private investment in carbon sequestration, for instance through development of voluntary or, in the medium term, mandatory offset markets. However, current EU policies limit the potential. The EU 2030 Climate and Energy Framework caps how much member states can use carbon sequestration to meet their GHG reduction targets for non-EU ETS sectors.

1.3.3. Denmark invests in renewables and is a leader in innovation

Denmark has experienced an investment boom in renewables over the last decade, driven by strong political leadership and targeted support policies. Support expenditure for renewables has increased significantly since 2010 due to the growing number of eligible projects (notably in wind energy) and low electricity market prices. More than half of electricity now benefits from public support for investment, market price support and tax breaks (compared to 16% across 26 EU countries), mainly for wind energy and combined heat and power (IEA, 2017[4]). The Energy Agreement provides for a switch to yearly technology-neutral tenders for wind and solar-photovoltaic projects in 2018 and 2019, which will be extended to incorporate more technologies in the coming years, reduce public support and thus improve cost-effectiveness.

Subsidies to biogas plants have reached record levels. However, in early 2019, the political parties that signed the Energy Agreement decided to stop support to new plants under the present support programme as of 1 January 2020 and instead introduce a tender system. Yet biogas does not lack environmental benefits. For example, using manure as a raw material for biogas instead of spreading it as fertiliser reduces the risk of air pollution (ammonia) and water pollution (nitrates), and digested manure is a high-quality natural fertiliser that emits much less nitrous oxide than untreated manure.

Several gas, oil, electricity and district heating companies have voluntarily committed to an annual energy savings target as part of the 2012-20 Energy Savings Agreement. This energy efficiency obligation (EEO) is financed by end consumers through their energy bill, on the “energy pays for energy (saving)” principle. The EEO implements the EU Energy Efficiency Directive, which aims for 20% energy savings by 2020 at EU level, in terms of primary and final energy consumption. Due to concerns about limited effectiveness and its impact on consumer tariffs, Denmark decided to have the EEO cease in 2021. A new call for tenders will take over and energy saving costs will be financed from the general budget.

Public expenditure on transport increased by more than 50% in real terms over 2005-16, driven by a large increase in rail infrastructure investment (ITF, 2019[30]). This reflects a commitment in the 2009 Transport Agreement to improve public transport, including an extension of the metro in Copenhagen and financial support to development of light railways in Aarhus and Odense. In addition, in 2014, the government at the time agreed on a DKK 28.5 billion (EUR 3.8 billion) investment in new railways, upgrading of existing railways and electrification of the rail network (IEA, 2017[4]). However, the Train Fund, intended to finance these investments, was later limited in scope. A recent agreement announced an infrastructure investment of DKK 112 billion (EUR 15 billion) for 2021‑30. Denmark should consider re‑evaluating the proposed project pipeline, as it contains projects that were found to have negative socio‑economic effects.

Public spending on environmental protection amounted to about DKK 34 billion (EUR 4.4 billion) in 2017 (SD, 2018[31]), or 1.5% of GDP. This includes expenditure for waste and wastewater management (72%), protection of biodiversity and landscapes (13%) and protection of ground and surface water, air pollution control, and public administration of environmental protection (15%). Most waste and wastewater expenditure is recovered from households through user fees, which is why household spending as a share of total final consumption expenditure (1.6% in 2016) is the highest in the EU (Eurostat, 2019[32]).

High user fees may reflect high quality of service and full cost recovery, but also service provision inefficiency. In the waste sector, for example, municipalities are not required to compete with private companies for waste collection and treatment. In the water sector, cost-effective behaviour is encouraged in the 2009 Water Sector Act, which sets requirements with respect to companies’ operating costs based on benchmarking, as well as a price ceiling. Recap regulation has helped halt water price increases and improve utilities’ efficiency; tariffs have remained relatively stable since 2009.

Denmark is one of the innovation leaders in Europe, and its patents have the highest level of specialisation in environmental technology among OECD countries (Figure 9). Measured per capita, Denmark ranks second for environment-related inventions, after Korea. The Danish wind industry is recognised as a world leader. The budget for innovation in clean technology was reduced by half over 2013‑16 (IEA, 2019[33]). However, Denmark has committed to increasing it again under Mission Innovation. The Energy Agreement confirms this commitment, increasing the clean energy innovation budget to DKK 580 million (EUR 78 million) in 2020 and DKK 1 billion (EUR 134 million) in 2024, bringing it back to 2010 levels. Business R&D spending is highly concentrated in a few large companies; incentives for R&D should also be made available to start-ups, which are often more innovative than their larger counterparts.

Figure 9. Denmark is a leader in green innovation

1.3.4. Dependence on foreign trade is high, as is foreign aid

Denmark has an open economy with high dependence on foreign trade. The transition to a low-carbon, circular economy is seen as an economic opportunity to boost exports of environmental technology and services, notably in energy technology. Clean tech has been the fastest-growing export sector in recent years, supported by Denmark’s international reputation as a front runner in green solutions and its strong framework of export promotion and assistance for internationalisation of innovation and commercial activities. Between 2003 and 2013, Denmark granted more export credits for renewables-based power generation projects than any other OECD country, thanks to strong support for wind energy. The government aims to double energy technology exports’ value to at least DKK 140 billion (EUR 19 billion) by 2030.

Environment and climate change are well covered in Denmark’s official development assistance (ODA). Denmark is one of the few countries that has achieved the UN target of allocating at least 0.7% of gross national income to ODA. The ODA budget was, however, reduced in 2015, affecting environment- and climate-related development finance, which dropped by 44% between 2014 and 2017 in real terms (OECD, 2019[34]). At the same time, the focus has been on enhancing private sector engagement and mobilising private investment. For example, the Danish Climate Investment Fund has committed to support projects with Danish commercial participation and has attracted Danish institutional investors. While this is consistent with global efforts to enhance blended finance, these activities must not come at the expense of untied ODA.

Recommendations on moving towards green growth

Framework for sustainable development

Continue developing green national accounts, publish them regularly and monitor their use in decision making; strengthen the statistical underpinning of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development at the national level and ensure that indicators are as internationally comparable as possible.

Greening the tax system

Reduce the energy taxation gap between households and businesses to equalise incentives for energy savings and CO2 reduction; continue efforts to make electric solutions for heating and mobility more attractive vis-à-vis fossil-fuel-based options.

Improve alignment of transport taxes with transport-generated externalities; in particular, ensure that lower taxes on vehicle ownership are matched by an increase in taxation of vehicle use (e.g. in congested areas).

Investment in a greener economy

Continue to gradually phase out subsidies to renewables technology as it becomes economically competitive, and ensure that remaining support is technology-neutral.

Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of and necessity for biogas subsidies; foster synergies between biogas development policies and nutrient management policies.

Establish mechanisms to mobilise private investment in carbon capture and storage options, including those arising from peatland rewetting.

Eco-innovation and green markets

Continue support for and ensure continuity of R&D in energy and other environmentally relevant areas, including climate mitigation options in agriculture and land use. Strengthen opportunities and incentives for more SMEs to engage in R&D.

Development co-operation

Continue to use ODA to leverage private investment in projects supporting sustainable development, ensuring that it does not come at the expense of untied ODA.

1.4. Waste, materials management and the circular economy

1.4.1. Recycling and recovery rates are high, but so is municipal waste generation

The Danish economy uses a lot of resources. In 2017, domestic material consumption per capita was about 24 tonnes, significantly higher than the averages per capita for OECD Europe (13 tonnes) and the OECD as a whole (16 tonnes). Domestic consumption of materials was decoupled from economic growth in 2008 and subsequent years, coinciding with the economic crisis. However, it has risen again since 2014. About half of national domestic consumption is non‑metallic minerals and related to construction. Driven by large-scale infrastructure projects, construction activity is not expected to slow in coming years.

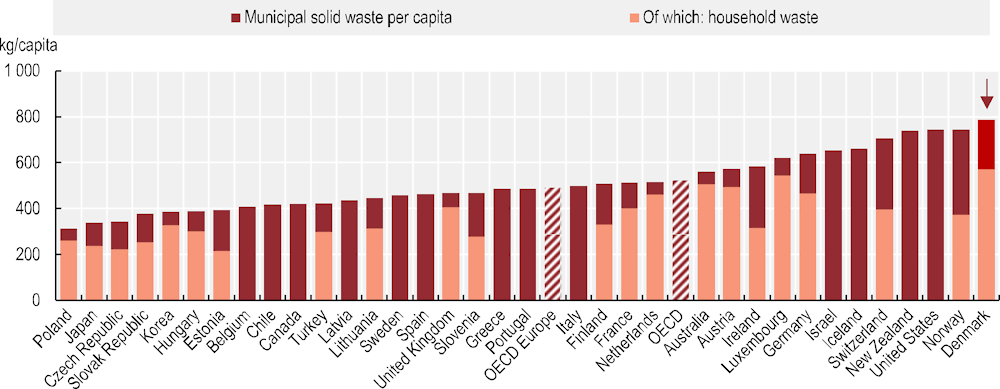

The country is not performing well in terms of waste generation. Total waste generation rose by 30% between 2010 and 2016, to about 20 million tonnes. This increase reflects a rise in construction and demolition waste, which accounted for about 60% of total waste produced in 2016. Municipal waste generation has grown faster than private final consumption, but has been stable since the introduction of a new waste information system in 2010. In 2017, municipal waste generation per capita reached 785 kg, far exceeding the OECD average of 524 kg (Figure 10). Since 2007, Denmark has had the highest levels of municipal waste among OECD countries.

Figure 10. Denmark’s municipal waste generation is the highest in the OECD

With regard to waste treatment, Denmark has nearly eliminated landfilling. Municipal waste landfilling fell from 5% to 1% between 2005 and 2017, mainly due to incineration with energy recovery. In addition, Denmark has achieved impressive results in material recovery of most waste streams. In 2016, it recovered 87% of construction and demolition waste, and recycled 73% of industrial waste, 74% of packaging waste and 89% of end‑of‑life vehicles. Household waste remains a notable exception. Incineration with energy recovery treated about half of municipal waste in 2017; the rest was recycled (27%) or composted (19%). The government estimates that it is on track to reach its goal of increasing the recycling share to 50% by 2022 for seven household waste fractions (plastic, paper, cardboard, glass, metal, wood, organic waste) considered jointly. Recycling increased from 22% in 2011 to 31% in 2016, the latest year for which figures are available.

The cost of waste management services increased significantly over the review period and is now among the highest in OECD Europe. Total public expenditure (current and capital) on waste management increased by 17% between 2005 and 2016. Waste management costs have increased faster than municipal waste generation.

1.4.2. The policy and legal framework in waste management is well established but future organisation is uncertain

Denmark has a strong policy and legal framework for waste and materials management. The main policies are defined in waste management plans and national strategies, such as Denmark without Waste: Recycle More, Incinerate Less (2013) and the circular economy strategy (2018). The main mandatory targets are derived almost exclusively from EU directives. The national regulatory framework includes a general framework law, the Environmental Protection Act, and a specific regulation, the Statutory Order on Waste. These are complemented by regulations on particular waste streams, treatment methods and specific policy aspects of waste management (waste monitoring, deposit-refund programmes).

Denmark has a long history of stakeholder platforms and think tanks, with numerous councils, advisory boards and partnerships involving public authorities. The National Council on the Bio-economy brings together companies, industry associations and universities to promote development of new value chains. It is working on bio-based products, with a focus on plastics, textiles and construction. The advisory board on circular economy has prepared recommendations for the development of Denmark’s circular economy strategy. Partnerships involving industry, businesses and public authorities are set up for a wide range of practical issues related to national strategy implementation (e.g. on green public procurement, collection of waste electrical and electronic equipment [WEEE], sustainable construction, waste prevention, reduction of food waste).

Denmark is well equipped to monitor trends in waste and material management through a robust information system. A waste data system, AffaldsDataSystemet (ADS), launched in 2010, has helped significantly improve data quality with an electronic register for waste collectors, consignees, exporters and importers. Pilot projects under way on material flow accounts, with detailed breakdowns by industry sectors and households, will be useful for enriching information to monitor the transition to a circular economy.

Responsibility for waste management policies is shared between MEF for overall policy objectives (environmental aspects, promotion of recycling, etc.) and the Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities for economic regulation of the waste management sector and provision of waste management services.

At the local level, the 98 municipalities have considerable autonomy in waste management planning. Since they are responsible for waste classification, they are largely free to decide on the treatment for a high proportion of total waste. As 82 municipalities own or co-own incineration plants and there is excess treatment capacity, there is a risk that they could be inclined to direct their waste to their incinerator. Municipal incinerators face no market incentives to compete on price, environmental performance or efficiency. Tipping fees range from around EUR 45 to EUR 96 per tonne of waste incinerated. Heavy public investment in municipal waste incineration has created dependence on steady deliveries of municipal waste and limited incentives for municipal investment in recycling and reuse.

In addition, private companies and industrial sectors have complained that waste classification differs by municipality, resulting in additional administrative burdens for operators. What one municipality considers waste may not be classified as such in a neighbouring municipality. Waste classified as recyclable in one municipality may be considered suitable for incineration in another. This lack of harmonisation makes the playing field uneven for companies operating across municipal boundaries.

The government’s 2016 Utilities for the Future strategy proposes an in-depth reorganisation of the waste management sector, with increased competition in incineration and a larger private-sector role in waste collection and recycling. However, discussions on practical implementation are stalled. This uncertainty about the future waste management framework discourages private and public investment in the circular economy.

1.4.3. A diverse policy mix encourages recycling despite incineration dependency, but more incentives are needed for waste prevention

Denmark has been a front runner in diverting municipal waste from landfill. It effectively combines a ban on landfilling of waste that can be incinerated, in effect since 1997, with a landfill tax, the rate of which has been steadily raised. This policy mix also aims to promote energy recovery from waste.

Several taxes apply to incineration: a tax based on the amount of heat produced (waste heating tax), an additional tax based on the energy content, a tax on CO2 emissions for non‑biodegradable waste, and taxes on NOX and SOX emissions. Incineration taxes are designed to ensure a level playing field in the energy sector and internalise air pollution and carbon externalities; they also provide an incentive to divert waste towards recycling, although no recent analysis has been made of the impact of incineration taxation on recycling rates.

Waste taxes were initially designed with a high rate for landfilling, a lower rate for incineration and no recycling tax, creating an incentive to recycle. The incineration tax was later redesigned to be closer to energy product taxes. The overall difference between incineration versus landfill taxation was kept the same so as to continue to encourage recycling.

The Danish recycling market is characterised by small facilities recycling materials such as glass, wood, plastic, construction materials, WEEE, metals and textiles. Aside from glass packaging, however, most of Denmark’s recyclable waste is exported to recycling centres abroad, including cardboard, plastic, WEEE and treated wood. The fragmentation of recycling markets in Denmark hampers private investment, as does the lack of municipal harmonisation on sorting.

Several municipalities apply volume- or weight-based pricing to unsorted residual household waste. The goal is to create an incentive to reduce waste and recycle more. However, despite the 2015 waste prevention strategy Denmark without Waste II, additional incentives are needed in view of the still high level of municipal waste generated. They are all the more necessary given municipal efforts to fulfil excess incineration capacity, which is not conducive to encouraging recycling and waste minimisation.

Denmark has several extended producer responsibility programmes, in line with EU requirements (e.g. for WEEE, end-of-life vehicles, batteries). In most cases it exceeds the EU recycling targets. Collection of WEEE, however, remains a challenge, as in other OECD countries, as large quantities remain outside the official collection systems.

In the construction sector, a tax on raw material extraction aims to promote rational use of resources. However, the rate (DKK 5/m3) is too low to prevent waste generation. In addition, many imported raw materials and non‑taxed building materials are available.

The weight-based landfill tax and possibility of recovering demolition waste without a permit (provided it is sorted, unpolluted and treated) favour recovery. Yet reuse of demolition waste, e.g. using concrete and crushed bricks instead of gravel in road repairs, often brings little added value. Several knowledge platforms and networks have been established in an effort to foster higher-quality recovery and selective demolition.

1.4.4. Denmark has reached a new political agreement to move towards a circular economy

Denmark has long paved the way for circular economy approaches by promoting eco‑design, clean production, eco‑innovation and sustainable consumption. An EPA analysis in 2017 showed that almost 58% of the population pays attention to ecological or organic labels when they look for environment-friendly products. Fifteen partners from municipal, regional and central authorities joined forces to promote green public procurement with purchasing criteria including recyclability and recycled content. This partnership covers 20% of all Danish public procurement. Green public procurement is supported by mandatory purchasing rules for timber, energy-using products and road vehicles.

In addition to product design, which must meet EU requirements, Denmark has introduced instruments to promote circular business models. These include information tools, such as dissemination of good practices (for example, a circular business web portal for SMEs), and financing instruments, e.g. providing support for eco‑innovation.

In October 2018, political agreement was reached on a circular economy, with a strong focus on how business can become its engine and how government can help (e.g. through one-stop shops, access to finance, digitalisation). The agreement recalls the objectives of the EU waste directives and notes the commitment of the private sector to increase resource productivity by 40% from 2014 to 2030 and to increase the recycling rate to 80% of total waste by 2030, in accordance with recommendations of the advisory board on circular economy. Large and small businesses are represented on the board, which the government established in 2016.

Recommendations on waste, material management and the circular economy

Reinforce waste prevention as a key priority

For household waste, expand pricing based on volume or weight – as in pay‑as‑you-throw programmes – while facilitating recycling and composting.

Accelerate R&D on sorting and recycling technology and innovative reusable and recyclable materials (e.g. biopolymers).

Develop policies to minimise output of single-use products, such as plastics.

Foster competition in incineration and better manage excess capacity

Improve the cost-effectiveness of incineration by reforming municipal waste management, giving companies flexibility to choose where to incinerate their combustible waste and making public tenders mandatory for municipal waste incineration.

Continue efforts to steer the transition to a circular economy

Harmonise criteria for sorting and collecting municipal waste fractions and consider unifying household and business recyclable waste markets to create economies of scale and encourage investment in innovation and large-scale recycling facilities.

Foster circular product design by introducing eco-modulation of fees in extended producer responsibility systems, based on recyclability, reparability and reusability.

Continue encouraging circular design by SMEs (e.g. through training and access to finance) and supporting companies in establishing take-back programmes and circular business models, e.g. with closed loops for products and materials.

Promote voluntary agreements between business and government on circular economy, ensuring that the objectives go beyond what is required by law.

Encourage voluntary initiatives and pilot projects to reduce “downcycling” (recycling that produces material of lesser quality and functionality than the original material) in the construction, textile and plastic sectors.

Secure financing to develop data for circular economy (e.g. green accounts and material flow information for industry sectors).

1.5. Chemicals management

As a small country with few chemical producers, Denmark relies heavily on imports to meet domestic demand for chemicals. Chemical policy is therefore aimed primarily at ensuring that imported chemicals and imported consumer products containing them are safe for the environment and health. To this end, Denmark has developed a high level of expertise in chemical risk assessment, becoming an EU and international standard setter.

The chemical policy framework derives largely from EU legislation, which Denmark has helped shape through its efforts to improve regulation of chemical use both nationally and internationally. There is good synergy and co‑operation on policy implementation between public authorities, industry and civil society. Public health and environmental protection issues are at the heart of Denmark's chemicals management policy, which pays particular attention to substitution of hazardous chemicals.

1.5.1. Pressures on health and the environment from chemicals are monitored, yet remain significant

Serious pressures from chemicals on health and the environment persist. A high prevalence of male reproductive disorders (40% of the male population have reduced semen quality) has been linked to exposure to certain chemicals, such as endocrine disrupters (EPA, 2013[35]). Groundwater contamination by pesticides remains a problem (Section 1). Reducing production and use of chemicals harmful to the environment and health is a strategic objective of the 2014‑17 and 2018‑21 Chemical Initiatives.

A comprehensive and long-standing monitoring system supports development of chemicals management policies. It includes the National Monitoring and Assessment Programme for the Aquatic and Terrestrial Environment, with dedicated programmes, e.g. for groundwater. There is also a pollutant release and transfer register (PRTR), though the number of installations it covers has decreased considerably since 2010. Danish research centres working on endocrine disruptor risk monitoring and prevention have developed biomonitoring programmes; increased public financial support would help fully exploit the centres’ potential (Bourguignon, Hutchinson and Slama, 2017[36]). Since 2001, the Danish Consumer Programme has conducted more than 160 surveys to identify chemicals in consumer products and assess their potential risks.

More generally, allocation of public financial support to chemicals management implies handling trade-offs between monitoring of effects on health and the environment, on one hand, and predictive risk evaluation, on the other. The first relates to chemical use while the second refers to the process of identifying regulatory actions needed before a negative impact can be detected in humans or the environment.

1.5.2. Exemplary policy and institutional frameworks are coupled with stakeholder co‑operation

Multi-year policy documents known as Chemical Initiatives set Denmark’s national strategies, priorities and objectives for industrial chemicals management (Government of Denmark et al., 2017[37]). Negotiations between the government and political parties outside the government precede the adoption of these policy documents and guarantee a broad commitment (and resources) for their implementation. A first ex post evaluation of their effects was carried out in 2017 for the 2014-17 initiative (Sørensen et al., 2017[42]). Denmark should consider making such evaluation standard and improve indicators to track implementation progress. The current occupational health and safety strategy addresses chemicals marginally, which is surprising given, for instance, the important interface between EU industrial chemical and occupational health and safety legislation (Government of Denmark et al., 2011[39]). The prominence of industrial chemicals in the forthcoming strategy on occupational work and safety beyond 2020 should be enhanced.

Denmark has a comprehensive regulatory framework that includes both EU and national instruments, with national rules sometimes going beyond the scope of EU regulations and directives (e.g. on provision of information on chemicals and on hazardous chemical installations). A process is under way to reduce Danish companies’ administrative burden, e.g. by avoiding going beyond EU requirements; it has affected the national regulatory framework by, for example, reducing the scope of reporting for the PRTR and green accounts. Nevertheless, Denmark has maintained the ambition of the Chemical Initiatives, whose 2018‑21 budget is higher than that for 2014‑17.

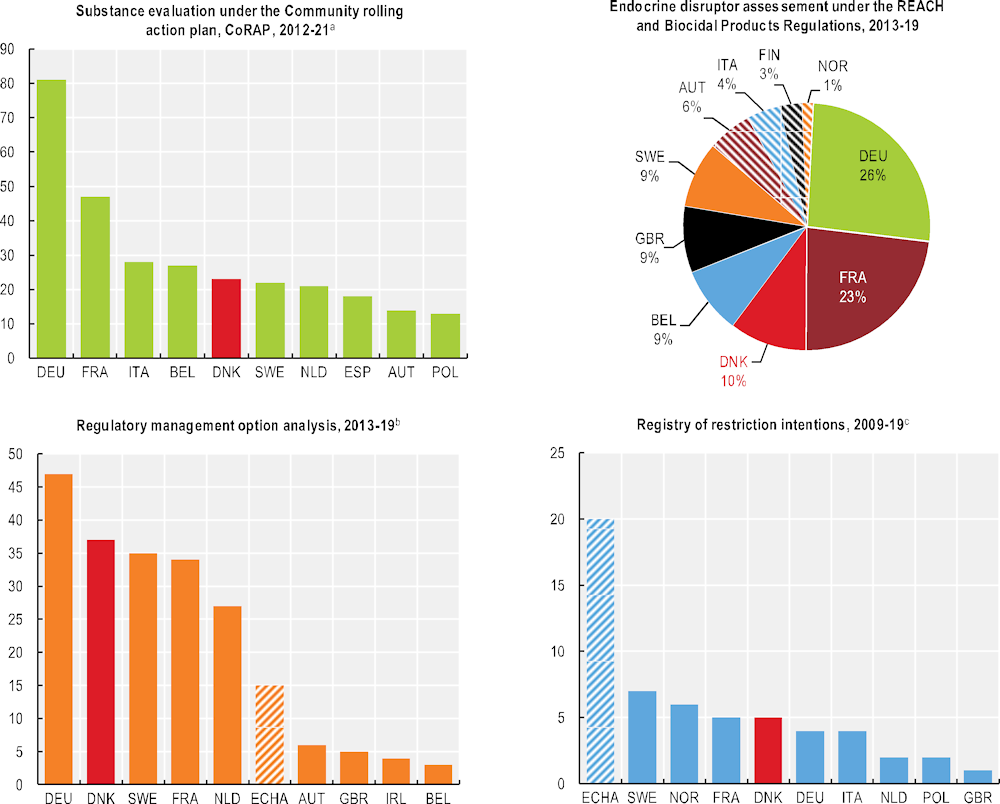

Denmark remains a standard setter in many areas of chemical policy, including systematic investigation and risk management of chemicals, as evidenced by the high number of chemicals assessed and the country’s contribution to regulation and restriction of chemicals at the EU level, among others (Figure 11). It should continue to be proactive in developing chemicals management policies for the benefit of the Danish population and to influence European and other international decision makers.

Figure 11. Denmark is active in evaluation and risk management of chemicals at the EU level

For example, the Danish experience with pesticide taxation could inspire many other OECD countries. In 2013, the taxation in force since 1996 was changed from an ad valorem tax to a differentiated-weight tax based on the effects on health and the environment (Holtze, Hyldebrandt-Larsen and Kühl, 2018[40]). The new tax has four components: a basic tax, a health tax (with rates differing by health hazards), a tax on environmental toxicity (with rates differing by species) and a tax covering persistence, bioaccumulation and leaching. This design has proved effective: it has reduced the pesticide load (in terms of sales) by 40% from the 2011 level. To make it more acceptable, revenue is returned to farmers through a reduction in land taxes.

MEF and EPA are the main institutions responsible for chemical policy, supported by several other authorities. Formal and ad hoc inter‑institutional co‑ordination ensures stakeholder participation in policy development.

Co‑operation of public authorities, industry and other stakeholders has been exemplary and should be continued. Various forums, such as the Special Government Committee for the Environment (in which stakeholders are consulted ahead of EU or international discussion and decisions on chemicals) and the Danish Chemicals Forum, provide a platform for involvement in chemicals management. The public has access to a vast amount of data and information on chemicals. Many campaigns have been held to increase awareness of hazardous chemicals and chemical exposure among the general public and vulnerable populations (Denmark, 2018[41]; Sørensen et al., 2017[38])

The main enforcement authorities are the EPA, the Working Environment Authority and the Maritime Authority. The enforcement strategy is risk based. Since 2015, the enforcement activities of the three authorities in relation to the EU REACH regulation have been aligned with the strategy of the European Chemicals Agency Enforcement Forum. Enforcement in relation to chemicals in products (including imported articles and e‑commerce) is a priority area for Denmark (Government of Denmark et al., 2017[37]), and a major challenge. In relation to the assessment work, a reduction in budget transferred to national authorities for their work under the EU REACH regulation is likely following the decrease in EU REACH registration fees. Testing of emergency response plans of hazardous installations has long been a problem (Amec Foster Wheeler, 2017[43]), but a new guideline to address it was issued in 2018.

1.5.3. The country has long been active in international forums and the regional setting

Denmark has always been at the forefront of discussions on chemicals management at the global and regional levels and has given international co‑operation an important place in national strategic documents. It continues to contribute actively to the work of international organisations involved in chemicals management, including the OECD, and to UN Environment’s Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM) (Denmark, 2018[41]). This leading role should be continued, e.g. in post-SAICM discussions.

Co‑operation within the EU has grown in line with the evolution of EU chemical legislation. Denmark also continues to play its part in the development of chemical policies in the Nordic, Arctic and Baltic Sea regions (Denmark, 2018[41]; Governments of Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands, 2011[44]).

Recommendations on chemicals management

Develop innovative tools to help decision making

Further expand risk-based monitoring of chemicals. For instance, enhance monitoring of legacy pesticides and their metabolites in groundwater and approved pesticides under the Pesticide Leaching Assessment Programme, and consider supplementing it with surface-water monitoring (relevant for biocides). Consider enhanced monitoring of emerging pollutants (e.g. pharmaceuticals in surface water and groundwater) and heavy metals (e.g. zinc in soil and water).

Strengthen biomonitoring to provide better evidence of people’s actual exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and possible effects on human health to support policy making in this area; address trade-offs between monitoring and proactive identification of chemicals requiring regulatory action, taking into account the science-policy nexus (e.g. identification of exposure source).

Make assessment of the Chemical Initiatives’ effects a standard procedure and consider further development such as increasing the use of indicators to track implementation progress.

Make better use of PRTR data (e.g. for tracking trends in releases or benchmarking among companies).

Implement and influence EU legislation