This section is divided into two main parts. The first part describes and analyses the current decentralisation policies in Portugal. The second part focuses on the regional development policies. Both sections identify a number of challenges in these policy areas. For decentralisation policies, one of the main challenges is the low degree of spending and revenue powers devolved to subnational governments, because this limits the benefits received from decentralisation. Other challenges include the unclear role of inter-municipal co-operation, the volatility of some of the municipal tax bases, and the overlapping assignments between deconcentrated central government units. From the regional development policy perspective, the current challenges include the ability of CCDRs to catalyse a truly cross-sector and strategic approach to regional development, and the mismatches in geographic boundaries of deconcentrated Ministry branches.

Decentralisation and Regionalisation in Portugal

3. The case of Portugal: Diagnosing multilevel governance strengths and challenges

Abstract

Note by Turkey: The information in this document with reference to “Cyprus” relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Turkey recognises the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Turkey shall preserve its position concerning the “Cyprus issue”.

Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union: The Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Turkey. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.

Stage of decentralisation in Portugal

This section will provide a brief description of the Portuguese multilevel governance model from political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation aspects. The section will also discuss Portuguese decentralisation in international comparison. At the end of the chapter, the challenges of the Portuguese model are discussed.

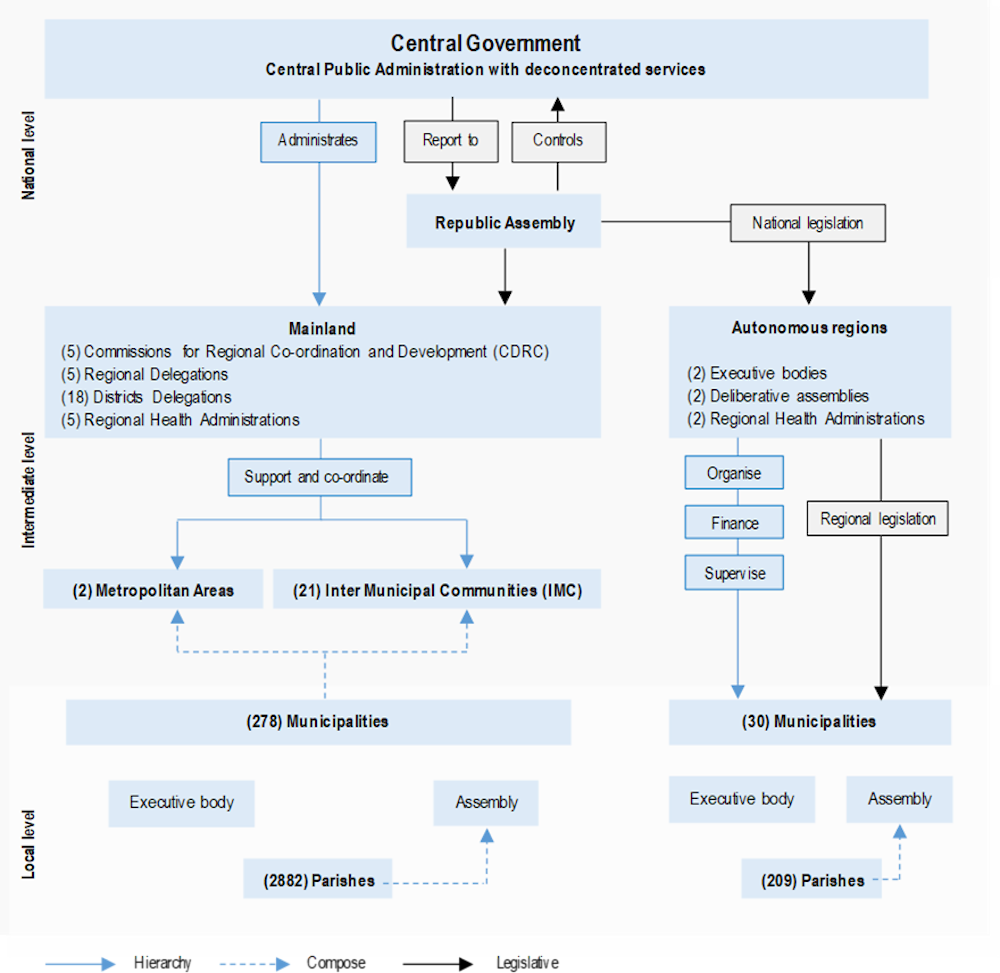

Subnational government structure

Since the 1976 Constitution, there are 308 municipalities (278 in the mainland) and 2 autonomous regions in Portugal. Although the 1976 constitution established the creation of administrative regions in the country, they were not implemented in the mainland and currently, only two exist, namely the islands of Madeira and the Azores. In addition to the autonomous regions and municipalities, currently, there are also 3 091 parishes (2 882 in the mainland, 155 in the Autonomous Region of the Azores and 54 in the Autonomous Region of Madeira) (see also Figure 3.1). All these three layers of government have elected governments.

The current legal framework also includes two additional local administrative entities, run by nominated political representatives of the municipalities/parishes: the intermunicipal entities (IMC) and the associations of municipalities/parishes for specific purposes. The former are associations of municipalities that currently consist of 2 metropolitan areas (MAs, Lisbon and Porto) and 21 intermunicipal communities, all in mainland Portugal. The latter are associations of municipalities or parishes, created to perform specific tasks.

In addition to the local administrative entities, the local public sector also comprises municipal and intermunicipal enterprises (MIEs). These enterprises were built as private-law-based entities, acting in a business-like fashion, however granting oversight powers to the local government. The main driver of this legal initiative was to provide common ground to local government that wanted to explore local entrepreneurship as an alternative to an inhouse solution. The law to allow the creation of municipal enterprises was enacted in 1998 and altered a few times until the current legal framework was enacted in 2012. A municipal enterprise is legally defined as a business-like organisation, which is partially or entirely owned by a municipality, association of municipalities or metropolitan area.

Municipalities can also pursue their tasks through other organisational forms aimed at interinstitutional co‑operation: i) co‑operatives and foundations; and ii) associations. In both cases, other partners can be involved, namely public, private or from the social sector.

It should also be noted that in parallel to the above-mentioned units, there is a large number of consultative entities whose mission is to promote vertical and horizontal dialogue/co‑ordination between levels and sectors of government.

Political decentralisation

Democracy was re-established in Portugal on 25 April 1974, after 48 years of dictatorship. The first elections for the regional governments of the Azores and Madeira took place in 1976 and every four years since then. The first elections for local governments were held in 1976. Initially, the local elections took place every three years (1979, 1982, 1985) and then every four years (1989, 1993, 1997, 2001, 2005, 2009, 2013 and 2017).

Figure 3.1. Portuguese model of multilevel governance

Note: Municipal and intermunicipal enterprises, as well as other organisational forms aimed at interinstitutional co‑operation, are not included in the graph.

Source: Author’s elaboration.

The governing bodies of the Autonomous Regions of the Azores and Madeira are the legislative assembly and the regional government. Members of the legislative assembly are elected directly by voters by proportional rule. The president of the regional government is nominated by the representative of the republic, considering the election results for the legislative assembly and after hearing the political parties represented therein.

Municipalities are governed by the town council (executive power) and the municipal assembly1 (deliberative power). The town councillors are elected directly by voters registered in the municipality by proportional rule. The leader of the party or list2 receiving the majority of votes becomes the president of the town council (mayor) and has a prominent role in the executive. The number of full-time councillors, as well as the total number of councillors, depends on the number of registered voters. Some of the members of the municipal assembly are elected directly by voters registered in the municipality, while the remaining members of the assembly are the presidents of the councils of the parishes that belong to the municipality. Parishes also have executive and deliberative branches. The president of the parish’s council is elected directly by voters living in the area. The total number of seats in the municipal assembly must be at least three times that of the town council.

In the absence of administrative regions, the reinforcement of subnational levels of government occurred through the creation of intermunicipal co-operative units (IMCs). In 2008, a legal framework for municipal associations was adopted. Geographically, the IMCs follow the boundaries of the NUTS 3 regions. While membership in an IMC is not compulsory, all municipalities are currently members, as municipalities are steered to join by upper-level incentives associated with the management of European Union (EU) structural funds. The IMCs are governed3 by the intermunicipal assembly (deliberative power), the intermunicipal council, the executive secretariat (executive power) and the Strategic Council for Intermunicipal Development (advisory power).4

Administrative decentralisation

Subnational government responsibilities

Autonomous regions

The legal background for administrative and fiscal decentralisation of autonomous regional governments is currently established by the Political-Administrative Status of the Autonomous Regions of the Azores (Law no. 39/80, changed by Laws no. 9/87, 61/98 and 2/2009) and Madeira (Law no. 13/91, changed by Laws no. 130/99 and 12/2000), and the Autonomous Region’s Finance Law (Organic Law no. 2/2013). The assignments are different for each autonomous region according to their political-administrative status. The autonomous regions can exercise their own tax power, under the terms of the law, and may adjust the national tax system to regional specificities, in accordance with the framework law of the assembly of the republic.

Local governments

For municipalities and parishes, Law no. 75/2013 defines their assignments and Law no. 73/2013 the financial regime. According to Article 23 of Law no. 75/2013:

1. It is the responsibility of the municipality to promote and safeguard the interests of its people, in articulation with the parishes.

2. The municipalities have assignments, in particular, in the following domains:

a. rural and urban equipment

b. energy

c. transport and communications

d. education, teaching and vocational training

e. heritage, culture and science

f. leisure and sports

g. health

h. social assistance

i. housing

j. civil protection

k. environment and basic sanitation

l. consumer protection

m. fostering development

n. spatial planning and urban planning

o. municipal police

p. external co‑operation.

The list of assignments has been kept relatively stable over the last 20 years. The assignments are valid for all municipalities, regardless of their type or location (e.g. whether they are located in the mainland or islands). Through laws and decree-laws, the government can delegate competencies in the municipalities or intermunicipal entities in any of the above assignments. In 2015, Law no. 69/2015 expanded the local authorities’ competencies in education, teaching and vocational training, and Decree-law no. 30/2015 specified several aspects of the decentralisation process.

In order to clarify the assignments and responsibilities, and to take steps for further decentralisation, Law no. 50/2018 of 16 August defined the framework for the transfers of new additional competencies to local authorities. The transfer of competencies started in 2019 for the local authorities that did not declare, until 15 September, that they were not willing to implement them (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. The ongoing decentralisation process

The current decentralisation process in Portugal is formed by two main dimensions:

1. The reorganisation of the state at the regional and subregional levels, only in the continental part of the country.

2. The transfer of new competencies from the government to the municipalities, a transfer that in some cases can be for the IMC/MA, aiming to strengthen intermunicipal structures.

Regarding the first dimension, the political decision has no fixed schedule.

Regarding the competencies to be transferred to the municipalities, Law no. 50/2018 defined a wide range of new competencies to be transferred until January 2021. The specific conditions of these transfers, namely financial conditions, are currently being clarified.

In general terms, the areas of transference to the municipalities are:

1. Education, all that refers to non-tertiary education, except management of teaching staff and definition of curricular contents.

2. Social action at the local level, especially in the fight against poverty.

3. Justice: "Julgados de Paz” network (volunteer commitment court), social reintegration and support for victims of crimes.

4. Health, local equipment and management of non-clinical personnel.

5. Municipal civil protection.

6. Culture, local heritage and museums not classified as national.

7. State unused real estate assets.

8. Housing, housing of the state and management of urban rental and rehabilitation programmes.

9. Management of port-maritime areas: secondary fishing ports, recreational boating and urban areas for tourism development.

10. Tourism (intermunicipal entities): management of investment funds, planning and subregional tourism promotion.

11. Investment attraction and management of community funds (intermunicipal entities): definition of the territorial strategy for development and management of local development programmes with community funding.

12. Beaches: licensing, management and equipment of sea, river and lake beaches integrated in the public domain of the state.

13. Management of forests and protected areas.

14. Transport: infrastructures and equipment within urban perimeters.

15. Citizen service: citizen's shops.

16. Proximity policing, participation in the definition of a policing model.

17. Protection and animal health.

18. Food safety.

19. Fire safety in buildings.

20. Public parking: regulation, supervision and management of administrative misconduct.

21. Licensing games of chance and fortune at a local level.

Intermunicipal co-operation and metropolitan governance

Currently, intermunicipal communities (IMCs), which are organised at the NUTS 3 level, can take on the functions and tasks assigned by law to the municipalities. However, IMCs can only provide services that are assigned to them by municipalities and the central government. In the current legal framework, IMCs are designed to pursue the following assignments:

1. Promoting the planning and management of the strategy for economic, social and environmental protection of its territory.

2. Co-ordination of municipal investments of intermunicipal interest.

3. Participation in the management of regional development programmes.

4. Planning of the activities of public entities, of supra-municipal character.

It is also the responsibility of the IMC to ensure the co-ordination of actions between municipalities and central government in the following areas:

1. Public supply networks, basic sanitation infrastructures, treatment of wastewater and municipal waste.

2. Network of health equipment.

3. Educational and vocational training network.

4. Spatial planning, nature conservation and natural resources.

5. Security and civil protection.

6. Mobility and transport.

7. Public equipment networks.

8. Promotion of economic, social and cultural development.

9. Network of cultural, sports and leisure equipment.

As said, IMCs are charged with the assignments by the central government and the shared powers delegated by the municipalities. Considering this framework, a recent pilot study conducted by the General-Directorate of Local Administration (DGAL) identified four possible ways to organise the functions of IMCs: i) exclusive management of “municipal” functions, that is, these functions would be solely assigned to the IMC; ii) shared management of municipal functions; iii) exclusive management of functions directly delegated by the national government; and iv) shared management of national government functions. Currently, the intensity and diversity of co‑operation varies across the country’s 23 IMCs (Veiga and Camões, 2019[1]).

Box 3.2. Metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Porto

The national legislation defines the framework for Portugal’s two metropolitan areas (laws enacted in 1991, 2003, 2008 and 2013). The Metropolitan Areas of Lisbon and Porto are intermunicipal co‑operative arrangements, financed with membership payments by the municipalities and by transfers from the central government.

The Lisbon Metropolitan Area is formed by 18 municipalities and governed by a council of 55 members, who are nominated by the municipalities of the metropolitan area (MA). The Porto Metropolitan Area is composed of 17 municipalities and governed by an assembly of composed of 43 members nominated by member municipalities.

The current laws grant the metropolitan areas the authority to “participate”, “promote” and “co‑ordinate” various planning and investment activities of metropolitan scale. But the law also limits the authority of MAs. They are mainly dependent on the will of member municipalities and central government on their tasks and financing.

Currently, the responsibilities of metropolitan areas comprise transport, spatial planning, regional development, waste disposal, water provision and sanitation.

Municipal enterprises

The activities developed by municipal and intermunicipal enterprises remain clearly defined, now restricted to only two groups of specific areas. On the one hand, there are enterprises that exploit activities of general interest, limited to the promotion and management of collective equipment and provision of services in the areas of: education; social support, culture, health and sport; promotion, management and supervision of urban public parking; public water supply; urban wastewater treatment; urban waste management and public cleaning; passenger transportation; and distribution of low voltage electrical energy. On the other hand, companies of local and regional development, which can only operate in the following specific areas: promotion, maintenance and conservation of urban infrastructures and urban management; urban renewal and rehabilitation and management of built heritage; promotion and management of social housing properties; production of electricity; promotion of urban and rural development in the intermunicipal sphere.

Deconcentrated central government regional bodies

In mainland Portugal, according to Decree-law no. 104/2003, the Commissions of Co‑ordination and Regional Development (CCDR) are deconcentrated services of the central administration. Within central government, the CCDRs have administrative and financial autonomy, and they are responsible for carrying out measures that are useful for the development of the respective regions. CCDRs operate under a shared regime of the Ministry of the Environment and Energy Transition and Ministry of Planning. CCDRs’ regional mission is:

To ensure the co‑ordination and articulation of various sectoral policies at regional level.

To implement environmental, spatial and urban planning and urban development policies.

To give technical support to local authorities and their associations.

The organisational structure of the CCDRs is quite complex and comprises a president of the CCDR, an administrative board, a supervisory commission and a regional council. None of these bodies are directly elected, and the president of the CCDR is appointed by the Portuguese government for a period of three years. The area of activity of a CCDR corresponds entirely to that of NUTS 2 statistical units on the continent. There are currently five Regional Co‑ordination and Development Commissions: Alentejo, Algarve, Centre, Lisbon and Tagus Valley, North (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Map of the CCDRs (deconcentrated units)

Source: Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript.

Administrative regions: A description of yet-to-be-established regional governments

Portuguese Constitution establishes a model of regionalisation based on “administrative regions”. These administrative regions have not been implemented, but their possible creation is under discussion. Administrative regions are not to be confused with “autonomous regions”, which are found in the Azores and Madeira.

The organisation and functioning of the so-called administrative regions are defined in Chapter IV of Title VIII of Part III of the Portuguese constitution and Law no. 56/91 (also known as the Administrative Law). Law no. 56/91 establishes that an administrative region is a “territorial legal person, endowed with political, administrative and financial autonomy, of representative bodies that seek to pursue the interests of the respective populations as a factor of national cohesion”. Despite the legal preparations, the administrative regions have not been established.

By law, the administrative regions are local authorities, similarly to the municipalities and parishes, despite certain differences in the way they operate in relation to other local authorities. According to the constitution, administrative regions are a local authority that exists only in the territory of mainland Portugal.

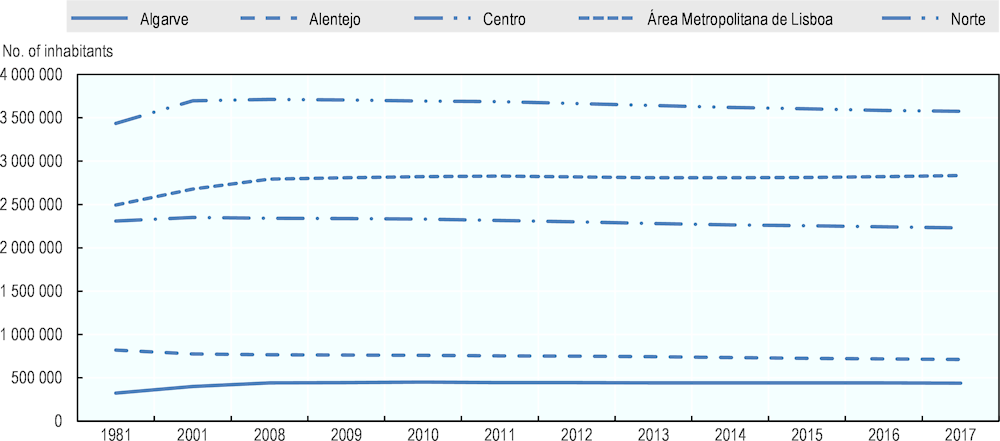

Figure 3.3. The population size of the Portuguese regions (mainland)

Source: OECD elaboration based on population data provided by Statistics Portugal (2019[2]), Resident Population, Estimates at December 31st, https://www.pordata.pt/en/DB/Municipalities/Search+Environment/Table (accessed on 29 May 2019).

According to Law no. 56/91, the administrative regions have a deliberative body (regional assembly) and an executive body (regional board), as well as a regional civil governor, which represents the Portuguese government in the area of the respective region. The regional assembly is composed of two groups of members:

Representatives of municipal assemblies, numbering 15 or 20, depending on whether it is a region with less than 1.5 million voters or 1.5 million and over. These representatives are elected by indirect suffrage, through an electoral college constituted by the members of the municipal assemblies of the region, who, in turn, were directly elected.

Members elected by universal suffrage, direct and secret, by citizens registered in the area of the respective region, numbering 31 or 41, depending on whether the region has less than 1.5 million voters or 1.5 million or more. Members of the regional assembly are called regional deputies and are appointed for four-year terms.

The regional board would consist of the president of the regional board and 4 or 6 members, depending on whether the region has less than 1.5 million voters or 1.5 million or more. The regional board would be elected by the deputies of the regional assembly, being that the president is the first element of the list more voted in the elections for the regional assembly.

There would also be a representative of the government in the administrative regions. The main task of the representative would be to co‑ordinate the work of deconcentrated administration with the administrative regions, especially with the regional board and regional assembly. The central government representatives would be appointed by the Portuguese government at a meeting of the Council of Ministers.

Box 3.3. Regionalisation in Portugal: A short history

Since the mention of regions in the Portuguese constitution and creation of Law no. 56/91 to define the legal base of administrative regions, the discussion on regionalisation in Portugal intensified, especially from the mid-1990s onwards. Based on political discussions, it was concluded that it was necessary and urgent to start the process of creating administrative regions in mainland Portugal.

During the following years, there was a lively debate about the creation of administrative regions and the regional map for mainland Portugal. In 1995, António Guterres was elected as prime minister with the creation of administrative regions in his electoral programme. However, at the time of the constitutional revision of 1997, a mandatory referendum was included as a legal requirement for establishing regions. This is still seen today by many regionalists as an attempt to halt the progress of the regionalisation process in Portugal.

In 1997, two maps for the regional division, both proposing nine regions, were presented and later reduced to eight. The proposal of the eight regions was made official in the Law of Creation of the Administrative Regions (Law no. 19/98), a law that would later be taken to a referendum. The law established the division of mainland Portugal into the following eight administrative regions:

Alentejo

Algarve

Beira Interior

Beira Litoral

Between Douro and Minho

Estremadura and Ribatejo

Lisbon and Setúbal

Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro.

Thus, on 8 November 1998, a referendum was held on the proposal to establish eight administrative regions. The referendum had two questions: one on the establishment of administrative regions and another on the institution of the region where the voter was registered. Probably due to the confusion and the lack of information released during the campaign, the referendum had a weak popular participation. The discussion on regionalisation became an eminently political issue, prompting many voters to withdraw from the issue.

The results of the referendum led to a rejection of the proposal by the electorate, but the referendum was not binding since no more than 50% of voters participated. As a result, there is a “gap” in the country's administrative structure. A number of powers that in the law are attributed to supra-municipal bodies (because they are regional in scope) are not entrusted to the central government nor to the municipalities and cannot be exercised by the administrative regions because they were not created.

The failure to set up administrative regions led to the creation of other bodies, such as urban areas (metropolitan areas and IMCs) and CCDRs. CCDRs were created in 2003 by merging the Regional Co‑ordination Commissions (RACs) and the Regional Directorates of Environment and Spatial Planning, which were also deconcentrated services of the central government. Before 2003, RACs were already functioning with functions similar to those of the current CCDR. RACs were established in 1979 following the planning regions created in 1969 during the government of Marcelo Caetano, with the aim of achieving an equitable regional distribution of development to be achieved by the Third Development Plan. Initially, the RACs had only functions of co‑ordinating the activities of the municipalities, but their competencies were later increased considerably.

Subnational government financing

Under the current legal framework, local governments have financial autonomy with respect to the following powers:

1. Preparing and approving financial plans, annual budget and financial accounts.

2. Deciding and managing their own assets.

3. Managing the tax powers legally granted.

4. Administering and collecting their own revenues.

5. Administering and processing expenditures.

6. Subscribing loans under the established legal limits.

The financial resources of local governments come from two broad types of revenues: own-raised revenues and intergovernmental transfers. Municipal own revenues are mostly tax revenues that come from direct and indirect municipal taxes, namely the Municipal Property Tax, the Municipal Property Sales Tax, the Municipal Surcharge, the Circulation Unique Tax and the amounts received in the process of issuing licences and user charges.

The largest amount of intergovernmental transfers to municipalities comes from the Financial Equilibrium Fund, a general-purpose grant that corresponds to 19.5% of the average of the amount collected with personal income tax, corporate tax and value-added tax. This fund is then divided into two sub-funds with different purposes and subsequently redistributed among municipalities with different criteria:

1. Municipal General Fund – to finance their legal assignments.

2. Municipal Cohesion Fund – with the objective of correcting asymmetries among municipalities, particularly with respect to fiscal capacity and unbalance of opportunities.

Municipalities are also entitled to a conditional transfer from the national budget – the Municipal Social Fund – designed to adjust to the transfer of additional assignments, mainly related with social functions such as health, education and social assistance.

Parishes’ own revenues are based on a small fraction of property tax and user charges related to some public services they provide. Parishes are also entitled to a general-purpose grant – the Financial Fund of Parishes – that corresponds to 2% of the average of the amount collected with personal income tax, corporate tax and value-added tax.

Local governments are limited with regard to indebtedness. The total amount of municipal debt cannot exceed 1.5 times the 3-year average of current revenues. In 2011, 141 (46%) municipalities exceeded the debt limit, which forced the national government to adopt severe measures. In the first place, the 2013 legal regime already recognised the importance of foreseeing the existence of municipalities in need of financial recovery. Accordingly, this law created a Municipal Support Fund, with equal participation of central and local governments, in order to financially assist unsolvable municipalities. The law also created a Regularisation Municipal Fund corresponding to the financial transfers retained by central government when municipalities failed to comply with the recovery plan and used to pay short-run debts.

Local governments’ financial activity has also been conditioned by the new regime of commitments and arrears by the public sector (Law no. 8/2012). For the settlement of the payment of debts of municipalities overdue more than 90 days, the Local Economy Support Programme (PAEL) (Law no. 43/2012) was approved. Through this programme, eligible municipalities can establish loan agreements with the state with a view to restoring the financial situation of the municipality.

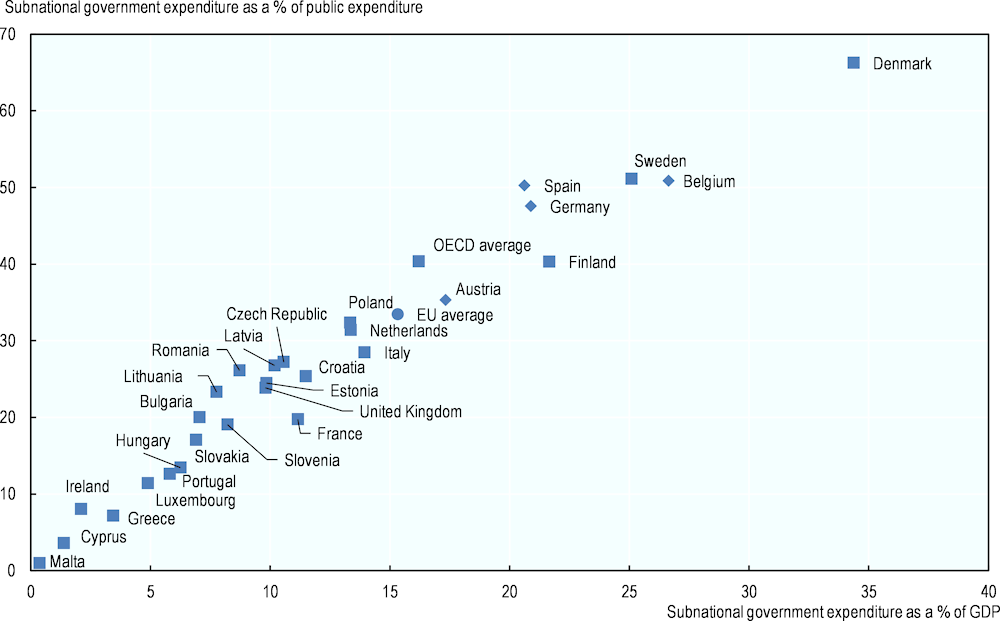

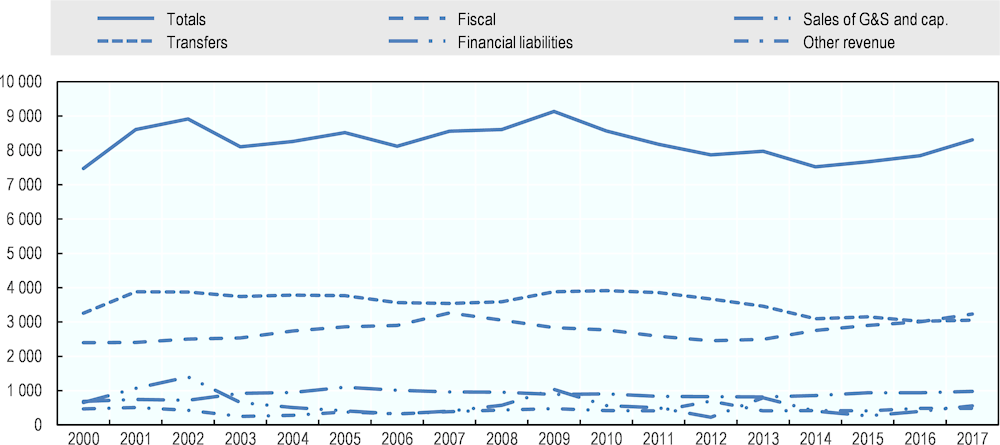

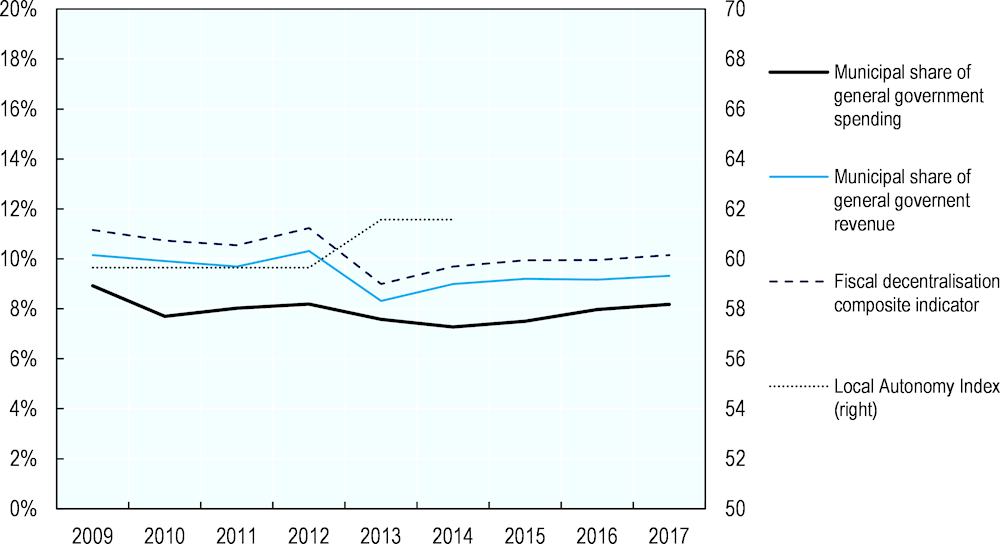

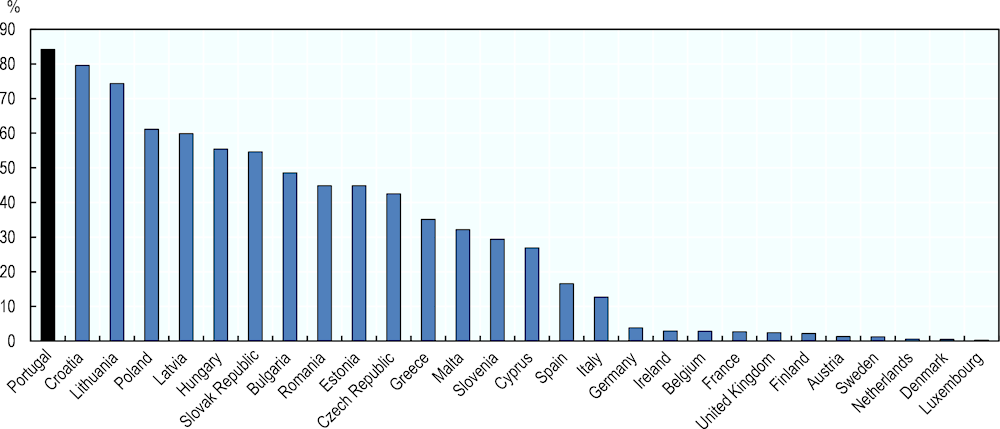

Decentralisation in Portugal in international comparison

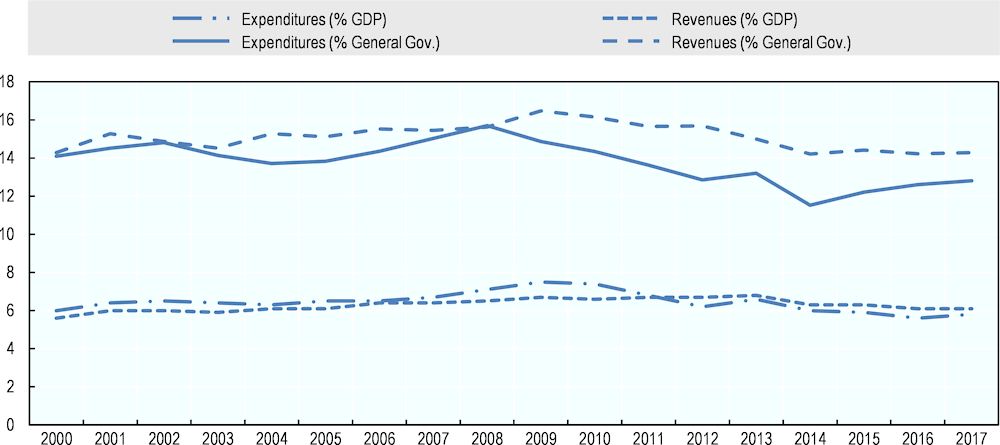

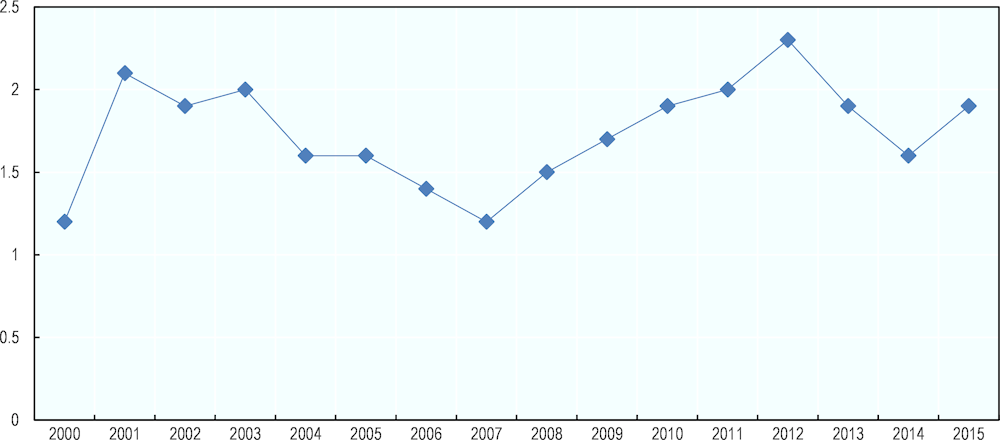

Measured with the usual decentralisation indicators, the degree of fiscal decentralisation in Portugal is relatively low (Figure 3.4). Moreover, there are no signs of major changes in decentralisation in Portugal during the past two decades. Between the years 2000 and 2017, subnational governments’ revenues/expenditures represented around 6% of gross domestic product (GDP) and sat below 17% of general government revenues/expenditures (Figure 3.5). Since 2008, the ratio of subnational governments’ revenues on general government’s revenues has exceeded the ratio of subnational governments’ expenditures on general government’s expenditures. The gap between the two ratios has expanded since the economic and financial crisis. This seems to be mostly because municipalities have adjusted their spending to reduced central government transfers, and because municipalities have been able to slightly increase their own revenues.

Figure 3.4. Portugal is among the least decentralised countries in the EU

Source: OECD (2019[3]), Making Decentralisation Work: A Handbook for Policy-Makers, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/g2g9faa7-en.

Figure 3.5. Regional and local governments’ expenditures/revenues as a percentage of GDP and of general government’s expenditures/revenues

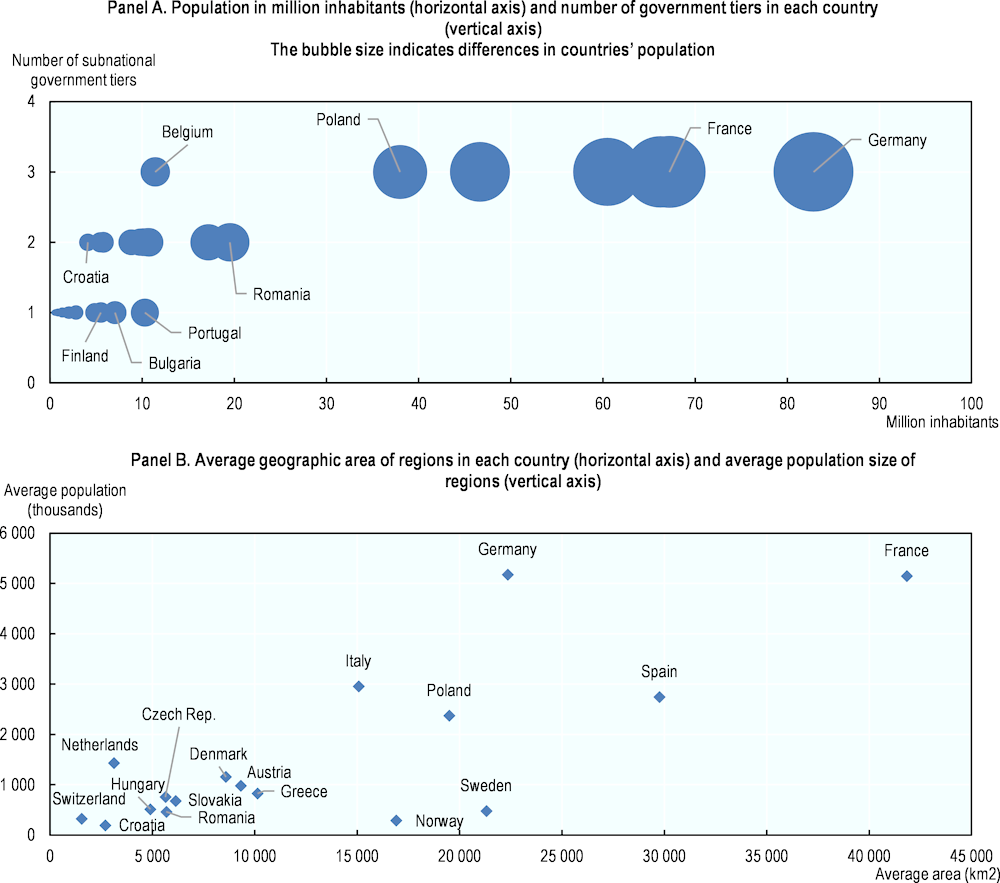

Among EU countries, Portugal belongs to the group of unitary countries with one subnational government level (municipalities and parishes are not counted as separate levels) (Table 3.1). This group consists mostly of countries with small population size, such as Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, the three Baltic countries, and also Bulgaria, Finland and Ireland (Figure 3.6, Panel A). In Bulgaria, Finland and Portugal, the governments are currently planning or discussing regionalisation reforms. The second country group, with two subnational governments, is formed by countries with slightly bigger populations, such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Sweden. The third-country group, with three tiers of subnational government, consist clearly of the biggest countries by population. France, Germany and Poland, among others, belong to this group. The association between a country’s population size and the number of subnational tiers is clear, as bigger countries tend to have more tiers (correlation between population and number of tiers is 0.79). There is nevertheless some overlap between the groups, as can be seen from Figure 3.6 (Panel A). Portugal could, based on its population size, also belong to a group of countries with two levels of subnational government. Panel B of Figure 3.6 shows the considerable variation in the size of administrative regions in the OECD. Among unitary countries in the OECD, France now has the largest regions in terms of population, and Chile in terms of size.

Table 3.1. Subnational government organisation in the EU28

|

Countries with one subnational government level* (n=11) |

Countries with two subnational government levels** (n=10) |

Countries with three subnational government levels** (n=7) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Federations (n=4) |

Austria |

Germany Belgium Spain§ |

|

|

Unitary countries (n=24) |

Bulgaria Cyprus Estonia Finland§ Ireland Latvia Lithuania Luxembourg Malta Portugal§ Slovenia |

Croatia Czech Republic Denmark Greece Hungary Netherlands Romania Slovak Republic Sweden |

France Italy Poland United Kingdom§ |

* Municipalities.

** Municipalities and regions.

*** Municipalities, intermediate governments and regions.

§ : Spain is a quasi-federal country; Portugal has two autonomous regions; Finland has one autonomous region; The United Kingdom has three “devolved nations” at regional level.

Figure 3.6. Population size and number of subnational government tiers among EU28 countries and the OECD countries

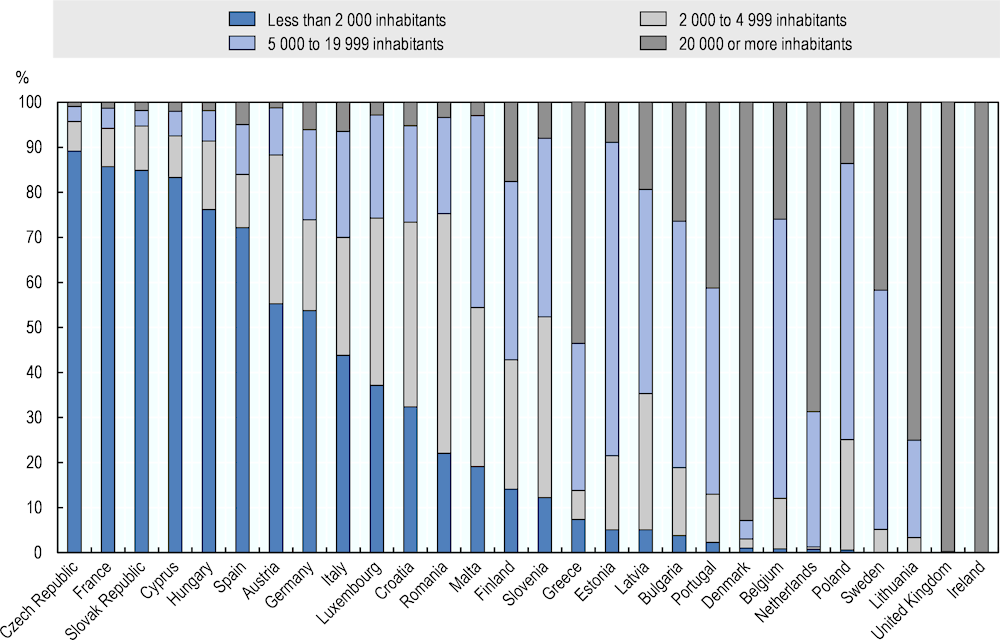

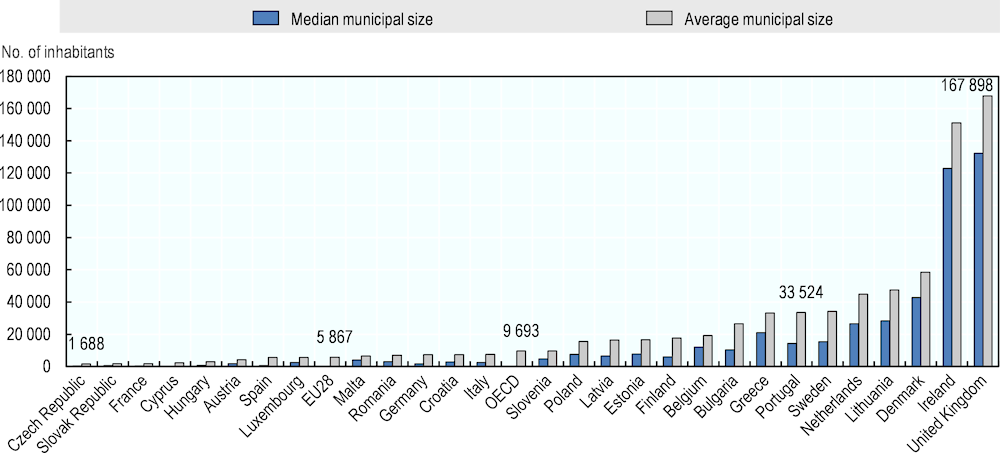

The average population size of Portuguese municipalities is 33 600 inhabitants (35 400 in the mainland) (Table 3.2). This is among the highest municipal population sizes among EU countries, although the size is higher in Denmark, Ireland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom (Figure 3.7). It should be noted, however, that in Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden for example, the municipalities are responsible for many demanding tasks such as social services and healthcare.

Despite of relatively high average population size, the differences between municipalities are nevertheless considerable. Municipal population varies between 460 000 and 504 000 inhabitants. Only 6 municipalities have more than 200 000 inhabitants. Four of these are located in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon (Lisbon, Sintra, Cascais and Loures), while two belong to the Metropolitan Area of Porto (Vila Nova de Gaia and Porto). Altogether 118 municipalities have less than 10 000 inhabitants and 67 municipalities have between 10-20 000 inhabitants. The differences in geographic, demographic and fiscal circumstances are considerable too (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Descriptive statistics for municipalities 2017

Indicators covering all 308 municipalities

|

Dimension |

Variable |

Average |

Standard deviation |

Smallest |

Biggest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scale |

Population (2017) |

33 575.7 |

54 690.1 |

459 |

504 471 |

|

Area (km2) (2017) |

299.4 |

277.8 |

7.9 |

1 720.6 |

|

|

Geography and demography |

Location (inland, coastal, islands) (2017) |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

|

Seasonality (stays per 100 inhabitants) (2017) |

639.2 |

1 689.8 |

6.2 |

20 613.2 |

|

|

Altimetric amplitude (meters) (2017) |

625.5 |

441.3 |

17.0 |

2 351.0 |

|

|

Population density (2015) |

291.5 |

794.0 |

4.3 |

7 426.8 |

|

|

Percentage of elderly population (>=65) (2015) |

23.9 |

6.3 |

8.1 |

45.4 |

|

|

Urbanisation (percentage of land for urban use) (2015) |

10.1 |

12.1 |

0.3 |

75.5 |

|

|

Fiscal |

Total expenditures per capita (EUR) (2017) |

1 145.7 |

646.8 |

353.0 |

6 863.4 |

|

Tax revenues per capita (EUR) (2017) |

222.7 |

157.5 |

64.4 |

1 147.1 |

|

|

Financial independence (own revenues as a percentage of effective revenues) (2017) |

41.9 |

18.8 |

6.7 |

94.5 |

|

|

Weight of transfers (percentage of effective revenues) (2017) |

58.2 |

18.8 |

5.5 |

93.3 |

Sources: Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript; National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2019[6]) and General-Directorate for Local Governments (Direção-Geral das Autarquias Locais, 2019[7]).

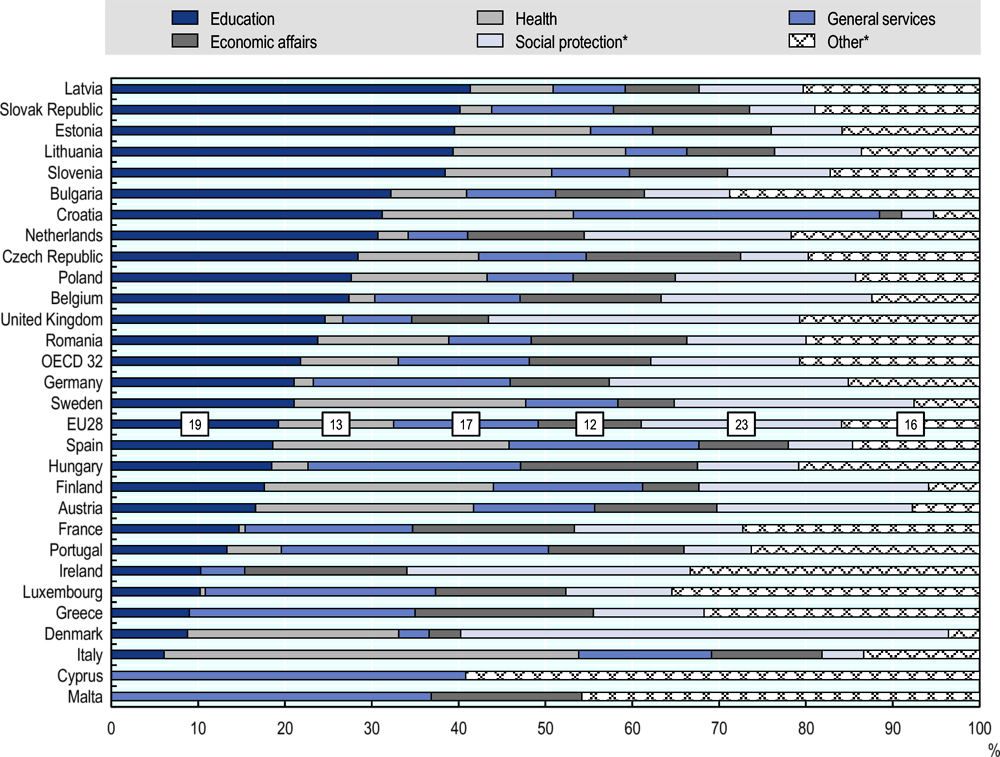

The strong role of central government in Portugal in public service provision is reflected in the responsibilities devolved to subnational governments (Figure 3.8). Compared with the EU average, the spending assignments of Portuguese subnational governments differ markedly. While in the EU, the three biggest sectoral spending categories are social protection, education and general services, in Portugal the main local services comprise general services, economic affairs and other services. In education, health services and social services, the central government bears the main responsibility in Portugal. While this differs from most EU countries, a similar situation prevails also in other centralised EU member countries, such as France and Greece.

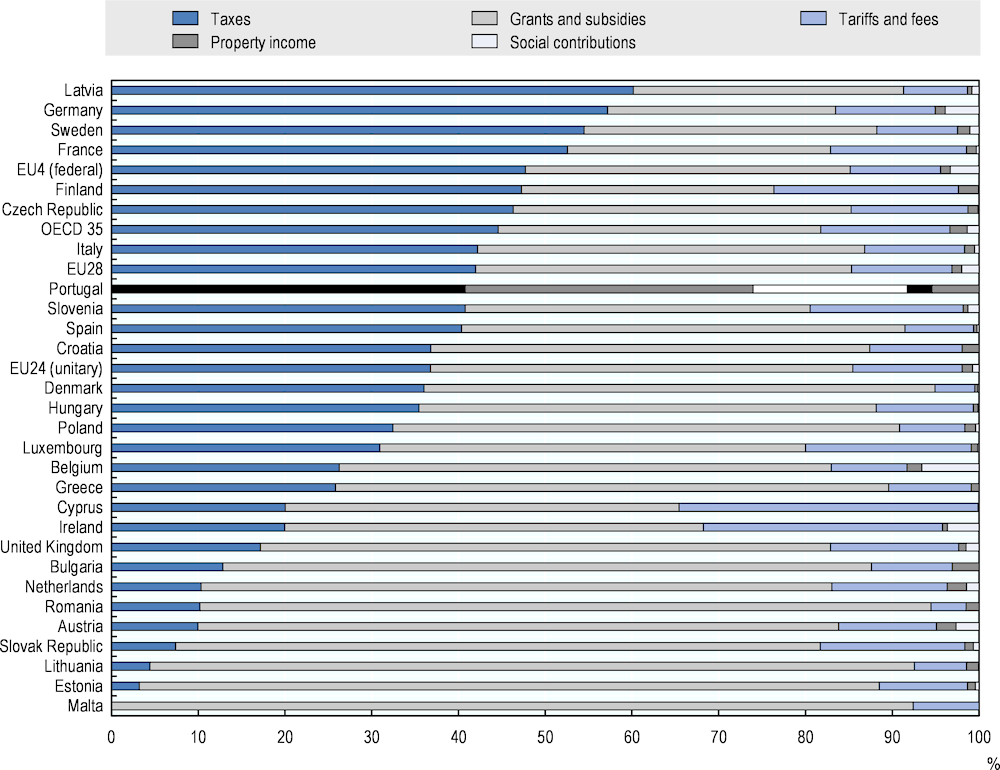

In contrast to the situation in spending responsibilities, the revenue structure of Portuguese subnational governments follows closely the EU and OECD mainstream (Figure 3.9). As in the EU on average, the most important source of revenue is tax revenues, followed by transfers and user fees.

Figure 3.7. Portuguese municipalities are big in terms of population compared with most EU countries

Source: OECD.

Figure 3.8. Portuguese subnational government provides local public goods

Source: OECD.

Figure 3.9. More than half of the subnational government revenues is formed by own-source revenues in Portugal

Source: OECD.

Main challenges faced by Portuguese multilevel governance

This subsection aims to identify policy areas where the current Portuguese multilevel governance could benefit from reform or rethinking of the system. The discussion here focuses on the challenges that can be identified by comparing Portugal to other countries or to the usual recommendations presented in the economics literature.

The current Portuguese multilevel governance model does not directly address regional level problems

In Portugal, regional level issues are currently addressed mainly with deconcentrated central government administration or with central government direct intervention. While the CCDRs are engaged in co‑operation and dialogue with local governments and other relevant stakeholders, due to limited resources and their mandate, the main focus of CCDRs has been on managing EC funding. Therefore, the ability of CCDRs to deal with issues concerning public service provision is restricted. Moreover, CCDRs lack the status and legitimacy that an elected regional government could have.

While there are no clear normative guidelines on how to assign spending responsibilities to different levels of government, the general principle presented in the economics literature is that the central government should be responsible for pure public goods such as national defence or foreign affairs. It is also recommended that the central government is responsible for macroeconomic stabilisation and fiscal policy. Similarly, redistribution should in principle be decided at the national level, although subnational governments may be (and often are in practice) involved in providing and producing services which involve redistribution. Subnational governments are best positioned to provide local public goods such as local roads, water and sewage, as these services’ benefits are mainly local. Subnational governments can also share the responsibility of service provision with central government in many other public services (Table 3.3). As for the regional level, there are many important policy areas where regional level of government could engage either in oversight, service provision or service production, or all three, as can be seen from Table 3.3.

Table 3.3. Assigning spending responsibilities in a multilevel government framework

|

Policy, standards, oversight |

Provision, administration |

Production, distribution |

Comments |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Water and sewers |

R,L |

L |

L, P |

Mainly local benefits |

|

Solid waste |

R, L |

L |

L, P |

Mainly local benefits |

|

Fire protection |

L |

L |

L |

Mainly local benefits |

|

Police |

R,L |

R, L |

R, L |

Mainly local benefits |

|

Parks, recreation |

R,L |

R, L |

R, L, P |

Benefits vary in scope |

|

Roads |

N, R, L |

N, R, L |

R, L, P |

Benefits vary in scope |

|

Natural resources |

N, R |

N, R |

N, R, L, P |

Benefits vary in scope |

|

Environment |

N, R, L |

N, R, L |

N, R, L, P |

Externalities vary in scope |

|

Education |

N, R, L |

N, R, L |

R, L, P |

Externalities, transfers in kind |

|

Health |

N, R, L |

N, R, L |

R, L, P |

Transfers in kind |

|

Social welfare |

N, R, L |

N, R, L |

R, L, P |

Redistribution |

N = National, R = Regional, L = Local, P = Private or non-governmental.

Source: Bahl, R. and R. Bird (2018[8]), Fiscal Decentralization and Local Finance in Developing Countries: Development from Below, https://www.e-elgar.com/shop/fiscal-decentralization-and-local-finance-in-developing-countries.

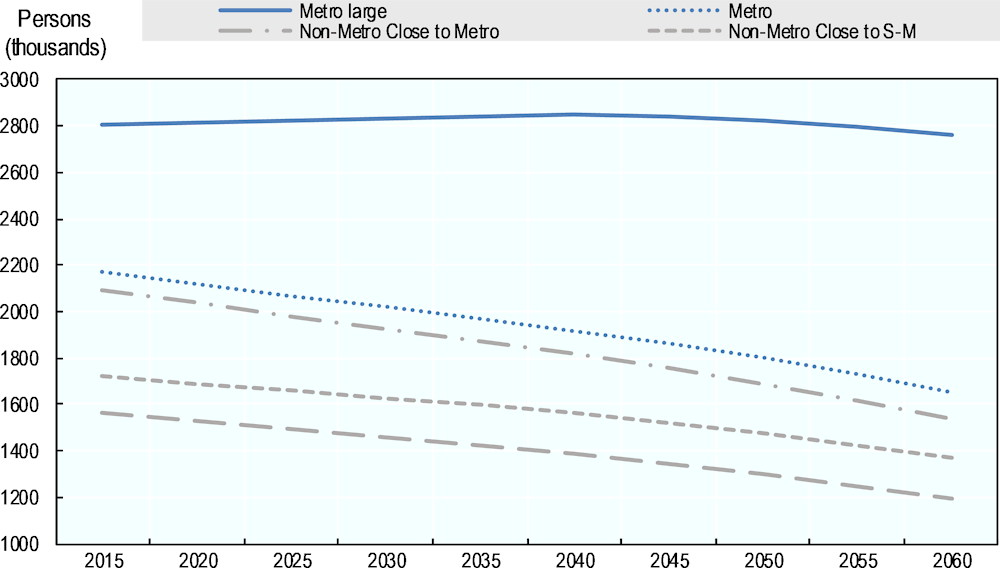

The rapid demographic change and sluggish recovery from the economic and financial crisis form together a tricky policy environment in Portugal

Based on the general principles of public spending assignments, it could be argued that in the Portuguese case, the lack of regional level of government may bring extra costs to public decision-making and public service provision. This is mainly because a regional level government is currently not used in oversight (although CCDRs and other deconcentrated administration do monitor and co-ordinate local tasks to some extent), service provision and service production. This is simply because there is currently no regional level of government in Portugal. Moreover, in Portugal, as in other countries, there are services with regionwide benefits (and which the IMCs are not well-positioned to internalise). In these services, the regional level service delivery could be defended.

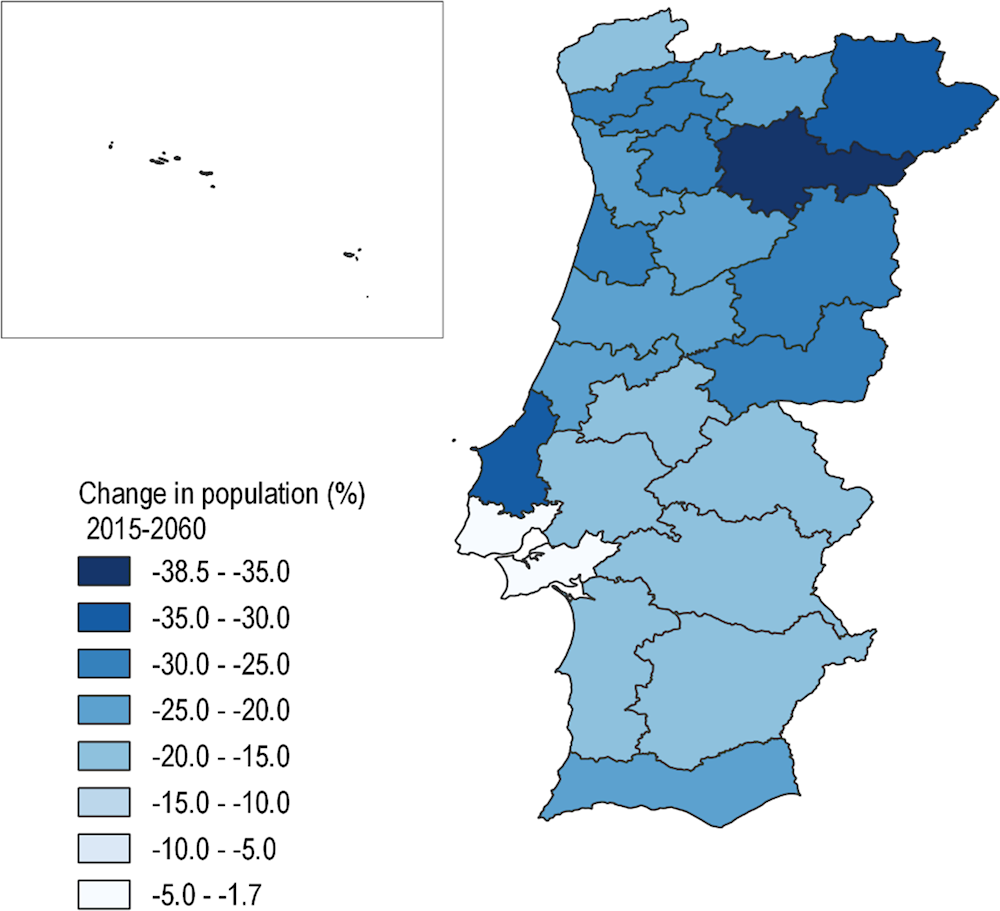

Like many other European Union member countries, in the coming years and decades, Portugal must find ways to solve problems that are formed by rapid population ageing, continuing urbanisation and the decreasing population especially in rural areas. While the population will decrease, especially in remote rural areas, metropolitan areas will also be affected. These trends challenge the Portuguese government both at the central and local levels and form the main pressures for structural reforms in the public sector.

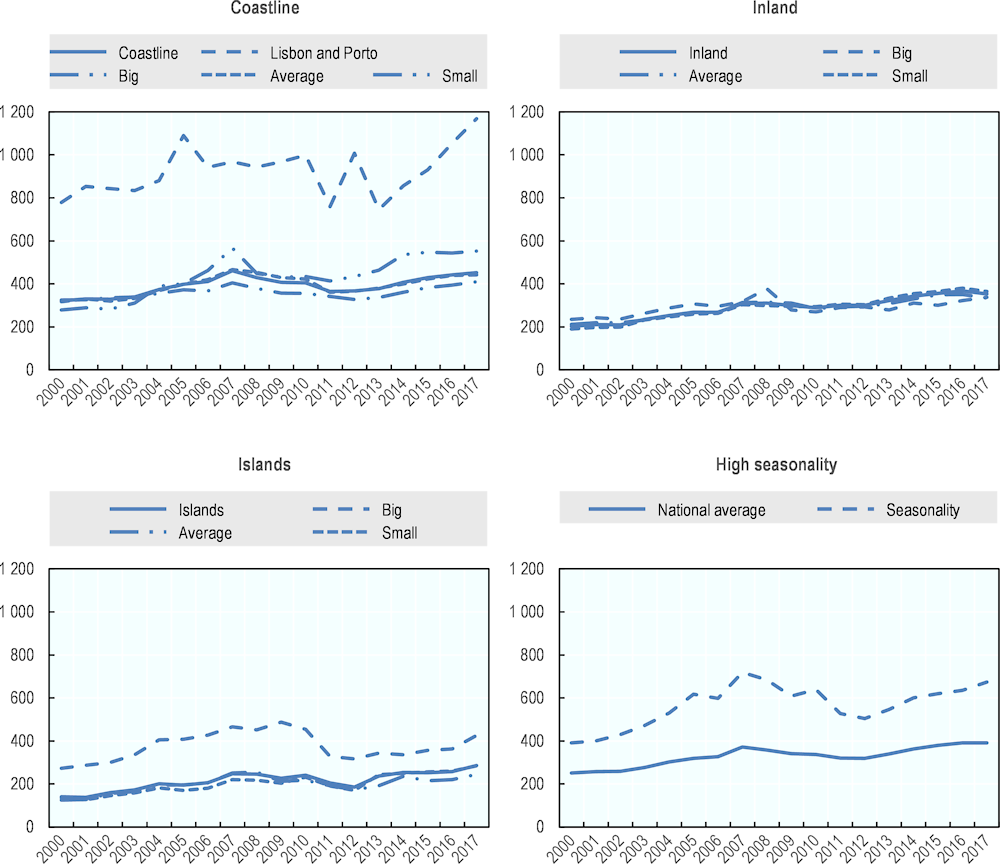

Portugal is currently in the process of adjusting its economy in the aftermath of economic and financial crisis. The austerity measures that have been taken have affected governments at all levels. For municipalities, the policy has meant belt-tightening as the intergovernmental transfers, which have traditionally been a major source for revenue for municipalities, have decreased considerably after 2010 (Figure 3.10). The good news is that the recovery of the overall economy has supported growth in local tax bases and this has helped municipalities to compensate part of the loss in central government funding with an increase in own-source revenues. Nonetheless, the transition from a centrally financed model to a model which is based on greater self-reliance at the subnational government level has been slow.

Figure 3.10. Municipal revenues by category between 2000 and 2017

Note: Each line represents national totals.

Source: Own calculations based on data from the General-Directorate for Local Governments (DGAL) (Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript).

Modest spending and revenue decentralisation miss the potential benefits of decentralisation

Despite current and past efforts to transfer tasks and revenues from central government to municipalities and intermunicipal entities, Portugal is by all measures still a highly centralised country. While the legal and administrative autonomy of Portuguese municipalities has been strengthened during the recent 5‑10 years, not that many important spending assignments have been devolved to local governments at the same time. It is interesting to note that although the Local Autonomy Indicator,5 which measures the local government’s autonomy with mostly legal and regulatory characteristics, shows increased local autonomy in Portugal since 2010, the fiscal data shows the opposite development (Figure 3.11).

The reluctance of the Portuguese central government to decentralise important spending to municipal level during and right after the austerity measures is understandable. During the past 7-8 years, the main focus of fiscal policy has been on spending control and savings. The dilemma is however that without further decentralisation, i.e. devolving more tasks and revenue to municipalities, IMCs and future administrative regions (if they are established), the benefit potential of decentralisation remains underutilised.

Figure 3.11. The legal and administrative status of Portugal’s municipalities has strengthened during the past decade, but fiscal decentralisation has developed in the opposite direction

Note: The municipal share of general government spending is the sum of the 308 Portuguese municipalities expenditures over the sum of expenditures at all levels of government in Portugal. The municipal share of general government revenue is the sum of the 308 Portuguese municipalities revenues over the sum of revenues at all levels of government. The fiscal decentralisation composite indicator summarises information on municipal spending and revenue shares in the general government. The Local Autonomy Index is an expert-based assessment of local governments’ autonomy combing dimensions such as institutional depth, policy scope, effective political discretion, fiscal autonomy, financial transfer system, financial self-reliance, borrowing autonomy, organisational autonomy and self-rule.

Sources: Statistics Portugal (2019[2]), Resident Population, Estimates at December 31st,

https://www.pordata.pt/en/DB/Municipalities/Search+Environment/Table (accessed on 29 May 2019);

Ladner, A., N. Keuffer and H. Baldersheim (2016[9]), “Measuring local autonomy in 39 countries (1990–2014)”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2016.1214911.

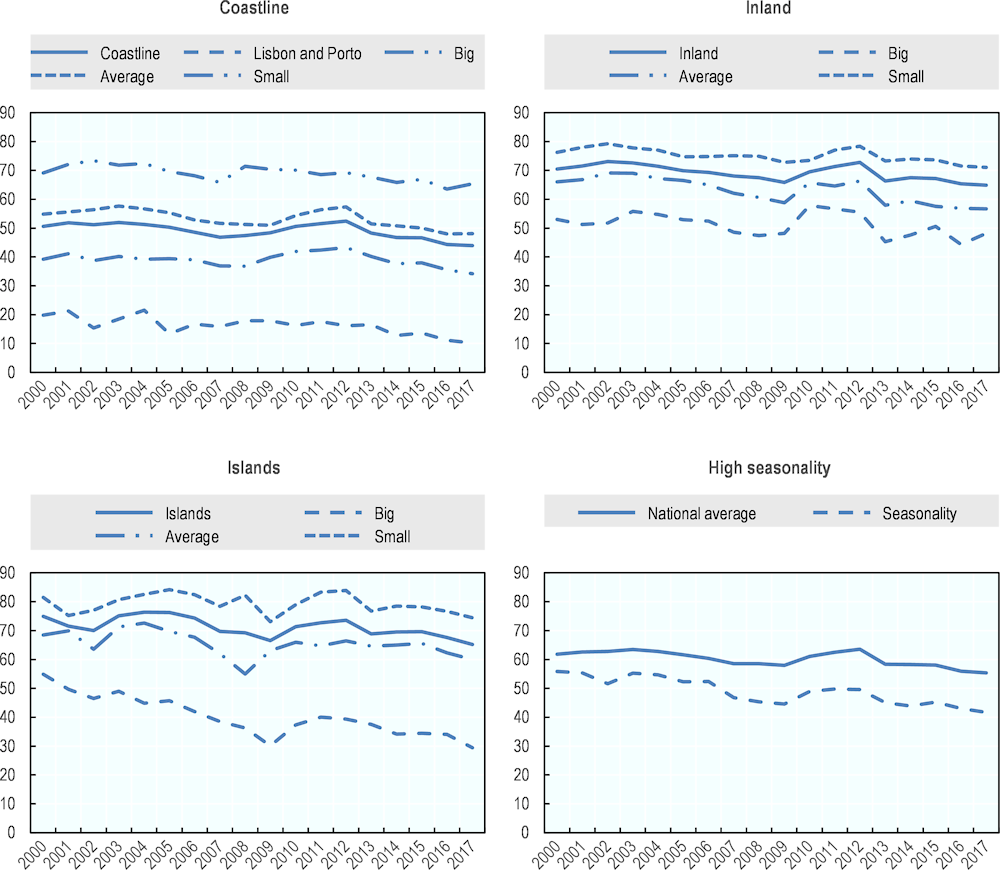

The differences in fiscal capacity between municipalities put pressure on the transfer system and fiscal equalisation

In 2017, on average, transfers represented 36.8% of total revenues for municipalities. Among these transfers, 78.3% corresponded to tax-sharing transfers that are determined by a formula, 10.1% to other transfers from the central government, 6.5% were EU transfers and the remaining 5.1% other transfers.

Municipalities differ considerably in their capacity to generate own revenues. Lisbon and Porto have the highest levels of own revenues per inhabitant, followed by other municipalities in the coastal area (Figure 3.12). At the other extreme are the inland municipalities, which are exceptionally dependent on intergovernmental transfers (Figure 3.13).

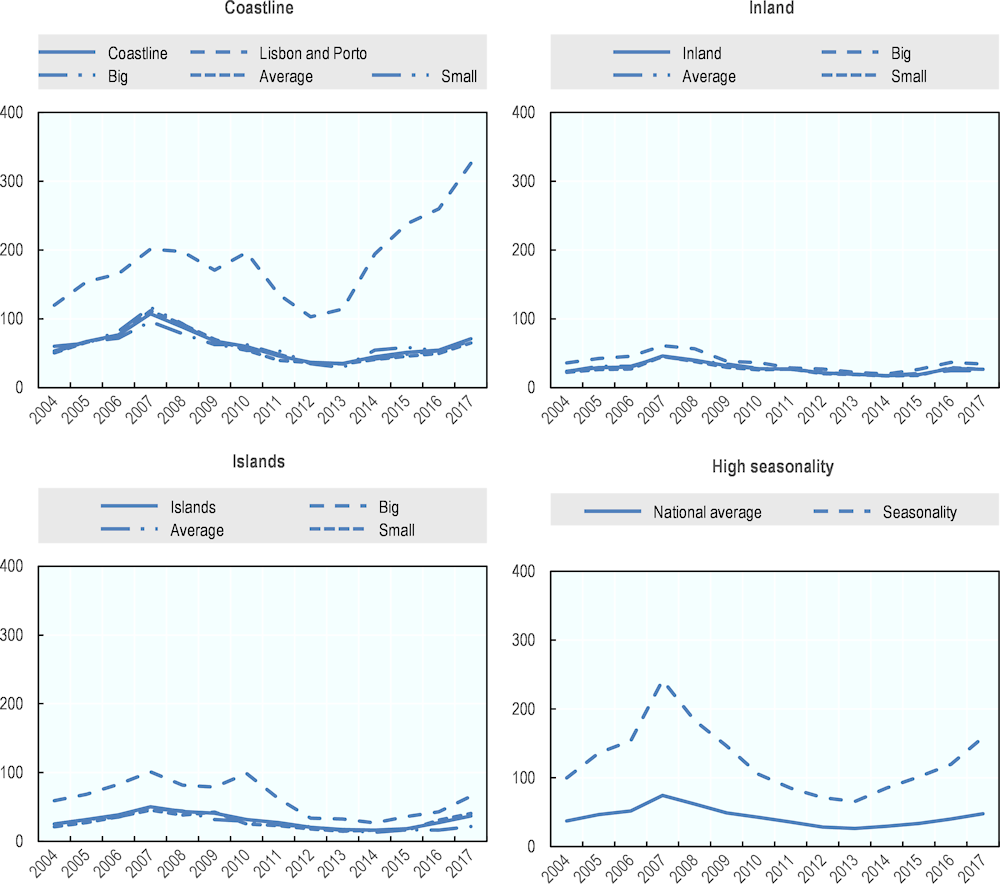

Figure 3.12. Average own revenue in different municipality groups

Note: Each line represents average values for municipalities belonging to each group.

Source: Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript.

Figure 3.13. Weight of transfers on total municipal revenue

Note: Each line represents average values for municipalities belonging to each group.

Source: Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript.

Tax competition between municipalities may have both beneficial and damaging effects

The municipalities with lower fiscal capacity, in the use of their freedom to explore legal fiscal limits, tend to adopt lower tax rates in property tax and surcharge tax (Veiga and Camões, 2019[1]). While this behaviour is understandable from a single municipality’s point of view, as a way to attract private investments and promote local economic development, it may have larger effects which are not all positive. From the positive side, competition between municipalities is beneficial if it enhances the efficiency of public service provision and constrains increase of tax rates. Competition can also be harmful, for example, if it leads to “race to the bottom” behaviour of the tax rate setting. This can erode tax bases and may eventually lead to worse local public services.

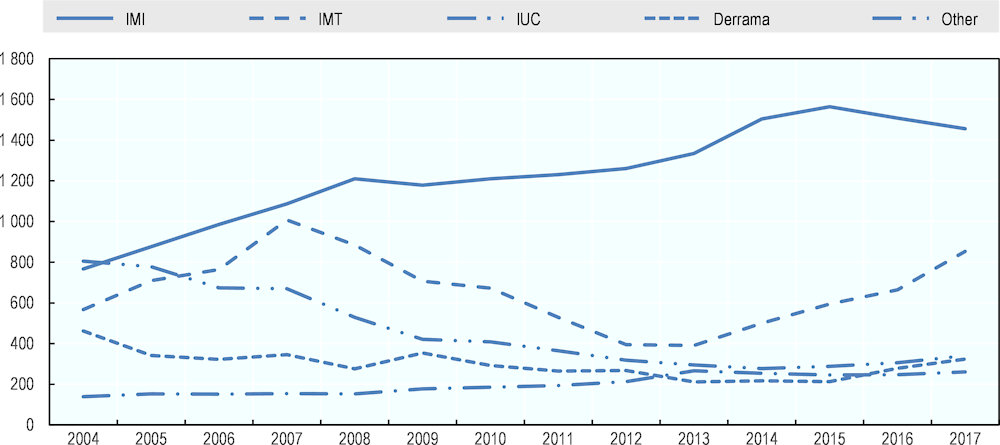

Volatile municipal tax bases may create spending risks

It is usually recommended that local revenues should be relatively stable and predictable over time. Hence, elements of local revenue system that contribute to volatility of taxes should be avoided. In 2017, the Municipal Property Purchase Tax (Imposto Municipal sobre Transmissões Onerosas de Imóveis, IMT) was the second most important tax for municipalities, forming 26% of total municipal tax revenues (Figure 3.14). The IMT reached its highest value in 2007 and declined considerably since then until 2013. The economic and financial crisis can be identified as the main cause of this decline (Veiga and Camões, 2019[1]). Since 2014, the IMT has been rising rapidly. It should also be noted that although Law no. 73/2013 predicted the abolition of the IMT in 2018, this did not happen, resulting in an increase in revenues for municipalities. While the biggest cities, which are the main beneficiaries of the IMT (Figure 3.15), can probably handle the risks created by volatile tax bases better than the small municipalities, in the medium and long run an important tax base with high volatility may create problems in spending side. Exposure to volatile local tax bases can lead to aggregate efficiency losses if expenditure rises in good times and governments find it harder to cut spending than raise taxes during a downturn, leading to a ratchet effect (Sutherland, Price and Joumard, 2005[10]).

Figure 3.14. Fiscal revenue of Portuguese municipalities

Note: IMI is the Municipal Property Tax (Imposto Municipal sobre Imóveis), IMT is the Municipal Property Purchase Tax (Imposto Municipal sobre Transmissões Onerosas de Imóveis), IUC is the Circulation Unique Tax (Imposto Único de Circulação) and Derrama is the Municipal Surcharge.

Source: Own calculations based on data from the DGAL (Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript).

Room for more impact evaluation of public policies concerning subnational governments

A number of reforms on municipal management have been decided during the past 5 years or so.6 While these reforms are expected to bring gains in terms of transparency, simplification and accountability of municipal decision-making, there is not yet much information available on the effects of the changes. For example, the merger reform of parishes was done with the purpose of strengthening the capacity of the parishes and promoting economies of scale to enhance efficiency. However, the impact evaluation of the effects of this reform is yet to be done.

Figure 3.15. Revenue from Municipal Property Purchase Tax is exceptionally volatile

Note: Each line represents average values for municipalities belonging to each group.

Source: Own calculations based on data from the DGAL (Veiga, L. and P. Camões (2019[1]), “Portuguese multilevel governance”, Unpublished manuscript).

Ideally, the impacts of the most important reforms should be evaluated systematically, both ex ante and ex post. Ex ante evaluation is especially useful in case of reforms that assign new responsibilities to subnational governments. An independent evaluation would give information on the feasibility, in particular on the resources and capacity needed for achieving the desired outcomes.

This said, it should be acknowledged that in Portugal there are some practices in place to measure service outcomes and user satisfaction. For example, in healthcare and in education, the efficiency and quality of services are followed systematically. Regarding regional development, the Agency for Development and Cohesion plays an active role in implementing, monitoring and evaluating the policies. Examples of such attempts include the Network of Regional Dynamics and Network of Monitoring and Evaluation.

Unclear role of intermunicipal co-operation

The metropolitan areas (MA) and intermunicipal communities (IMC) still play a marginal role in the public sector. As established in Law no. 73/2013 (Art. 69, no. 2), the amount transferred to IMCs is only 0.5% of the transfer system FEF (1% in the case of metropolitan areas). In addition, intermunicipal bodies have only a restricted capacity to raise own revenues. As a result, IMCs are mainly financed by municipalities. So far, municipalities have been reluctant to assign tasks to IMCs. This is understandable taking into account the relatively modest tasks and the strong population base of most municipalities. It appears that municipalities do not see need for the scale economies that IMCs could provide, or they are unsure of the service level that IMCs could provide for the member municipalities. This may, however, change in the coming years, as more responsibilities will be decentralised to municipalities. In any case, the challenge is to enlarge the role of intermunicipal organisations and guarantee their financial means.

It should also be noted that reforms that aimed to strengthen intermunicipal co-operation (IMC and MA), also increased the regulation. For example, the degree of conditionality in the access to community funds by the municipalities has increased, introducing rigidity in the process. While the aim of the regulation is to improve the quality of the projects and to act in a co‑ordinated way, the flip side of the tightened regulation is that municipalities may tend to adopt investments eligible for community funds as their priorities, in contrast with the real needs of the territories.

Municipal population size is high in European comparison

Municipal population size is under discussion in Portugal. Often the argument seems to be that in Portugal, the municipalities are too small to operate their current services, let alone take on more responsibilities. However, in international comparisons, the Portuguese municipal population size is not particularly small (the current average municipal population of 33 500 inhabitants is above the average of EU28 and OECD countries) (see Figure 3.16). The share of small municipalities in Portugal is not higher than in most other EU or OECD countries. Moreover, the current or planned tasks of Portuguese municipalities, which comprise mostly local public goods and supporting services of centralised health and education services, do not seem to be exceptionally demanding in international comparisons.

Figure 3.16. Municipal population size in Portugal in 2016 compared with other EU28 countries

Source: OECD.

It seems clear that, in any case, the municipal merger reforms will not be a politically feasible solution in Portugal. The question of increased utilisation of IMCs and MAs is therefore important in public service provision. If the administrative regions are established, this will also affect municipalities and co‑operative units, depending on the division of assignments at different levels of government.

Overlapping assignments between deconcentrated central government units may cause unnecessary duplication and be a source for inefficiency

There are currently deconcentrated central government departments in agriculture, education, employment, economy, social security, health and transport. The five CCRDs are responsible for the territorial co‑ordination of central government services in each region. However, there seem to be organisation challenges which may impede the current model in accomplishing all of its goals, for example:

The deconcentrated central government regional administration is based on a number of regionalised departments, which do not seem to always follow the same geographical borders, even within the same ministry. For example, the Ministry of Labour, Solidarity and Social Security has regionalised social security services within 18 district offices, which are deployed in 441 local services for the public. The same ministry is responsible for the Institute of Employment and Professional Training (IEFP), which comprises 5 regional delegations (coinciding with NUTS 2) and 53 local employment centres that may have several municipalities as their area of influence or even infra-municipal areas.

There is currently a large number of consultative entities whose mission is to promote vertical and horizontal dialogue/co‑ordination between levels and sectors of government. The risk is that the roles and responsibilities of various actors overlap and lead to loss of transparency as well as administrative burden.

It also appears that it is difficult for the presidents of CCRDs to co-ordinate the sectoral services as each sector is led independently by a sectoral president who is at the same level as the president of the CCRD.

Portuguese model of multilevel governance in comparison with systems in other EU countries: The path-dependency revisited

Local government in Europe features a wide range of organisations due to historical developments and national traditions. A path-dependent process is often observed in the implementation of regional reforms in Europe. For instance, a country with a strong tradition of centralisation will not immediately launch into political regionalisation. The political, institutional and cultural obstacles are too great. As illustrated by the French case, regionalisation is a slow, step-by-step learning process. Deconcentration towards the regions is often the first stage in moving towards regional governance models with elected self-government and fiscal autonomy and greater democratic legitimacy.

Three types of state exist in Europe: purely unitary states (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, the Slovak Republic, Sweden), federal states (Austria, Belgium, Germany) and hybrid states (Spain, the United Kingdom and even Italy). Three major state traditions influence local organisation: the Napoleonic tradition (e.g. France, Greece, Italy, Spain, Central and Eastern Europe) based on centralisation, uniformity and symmetry; the Germanic tradition (Austria, Germany, the Netherlands) which recognises intermediary bodies alongside a powerful state; and the Scandinavian tradition, which takes a uniformity principle from the French model but applies it within a more decentralised framework.

While this significant diversity makes it impossible to identify any single model of local government, it does not exclude (in fact, quite the opposite), making an inventory of common practices and observing similar trends towards more decentralisation and local responsibilities.

One observation of the practices is that there are a variety of local government tiers. The majority of countries have a one-tier model (Bulgaria, Cyprus,7 Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia),8 then the two-level model (Austria, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom) while the minority have a three-level model (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain). Although country size partly explains this (large countries like Germany, Italy and Spain opt for three levels, as does France), several countries seem to have attempted to unite local administrative areas to form regions, with nevertheless variable results (success of the Swedish experiment, failure of Hungarian project).

Countries with one subnational government tier

In Bulgaria, municipalities were re-established at the beginning of 1990s after several decades of a centralised socialist system in order to restore local democracy. Municipalities are subdivided into smaller towns and villages, totalling 5 267 in 2015. Of these settlements, there are around 2 500 mayoralties (deconcentrated municipal units established by decision of the municipal council, governed by elected mayors and comprising at least 350 inhabitants). There are 25 such units on average per municipality. The three main Bulgarian cities are subdivided into districts or raions (24 in Sofia, 6 in Plovdiv and 5 in Varna). There is also a central government territorial administration composed of 28 regions (oblasts), with governors appointed by the Council of Ministers (OECD/UCLG, 2016[11]).

In Estonia, there are currently 79 local government units. All local government units – towns (linn) and rural municipalities (vald) – are equal in their legal status. All local authorities decide and organise independently all local issues and all local authorities have to implement same tasks and provide the same range of services to their inhabitants regardless of their size (Rahandusministreerium, 2019[12]).

Ireland's subnational government consists of 31 local governments: 3 city councils, 2 city and county councils and 26 county councils. In addition, there are municipal districts, which are part of the relevant county council, acting as constituencies for county councils, with councillors, enjoying devolved local decision-making responsibilities to decide matters relevant to local communities (OECD/UCLG, 2016[11]).

Latvia’s territorial organisation consists of 110 districts and 9 “republican cities”. Districts have resident populations of at least 4 000 inhabitants and must comprise a village of at least 2 000 inhabitants. There are also five planning regions. They have no legal status but have indirectly elected regional governments (councils) made up of local authority representatives (OECD/UCLG, 2016[11]).

Lithuania has one tier of local self-government composed of 60 municipalities. The municipal level comprises 48 districts (rajonas), 6 towns (miestas) and 6 common municipalities, which all have the same status and competencies. Municipalities can set up submunicipal entities called wards (seniūnijos) to manage proximity services. There are around 545 such entities each headed by a civil servant appointed by the director of municipal administration. The ten counties (state administrative regions with centrally appointed governors) were abolished in 2010 and replaced by regional development councils composed of municipal councillors, but which remain under the direction of the Ministry of Interior (OECD/UCLG, 2016[11]).

In Slovenia, there are 212 municipalities. There is also a submunicipal level of 6 035 settlements (local communities and districts which are optional). The country is also divided into 58 administrative districts representing the state at the territorial level in charge of supervising municipalities (OECD/UCLG, 2016[11]).

Countries with two levels of subnational government

Austria has adopted a territorial organisation comprising 9 Länder and 2 356 municipalities (Gemeinden). This organisation is “symmetrical” since each level of authority has the same type of organisation and the same legal system. In Hungary, the 3 174 municipalities constitute the linchpin of the local administration system, with an average population of 3 200 inhabitants. The 19 administrative regions have strong historical legitimacy but their role today is mostly limited to managing social and health centres. The Netherlands also has 2 levels of local authorities: provinces, of which there are 12, and municipalities, which total 441.

The United Kingdom is organised in a particularly diverse manner. Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales each have a regional assembly (named “parliament” in Scotland) and local councils at local level (“unitary authorities”, or “district councils” in Wales). In England (United Kingdom), the situation is more complex: the country, which does not have a regional assembly, is divided into nine “government office regions” which are themselves divided into either unitary authority with a single administration level, or county councils.

In Sweden, the 2 levels of local authorities are the 21 counties (län) and the 290 municipalities (kommuner), with an average county/region population of 456 000 inhabitants and 32 000 in municipalities. These 2 levels are not subordinate and have different jurisdictions, some of which are obligatory and others optional. Two experimental “regions”, Skåne (Malmö region) and Västra Götaland (Göteborg region) were created in 1997-98 by bringing together several counties headed by a regional council that up to 2010 enjoyed a greater delegation of state authority than county councils, in particular in the area of economic development.

Countries with three levels of subnational government

The four countries with three-level organisation are also among the biggest by population in the European Union. In addition, three of them are federal or autonomist states in which the regional level possesses “state” powers.

In Germany, the 16 Länder, whose average population is close to 5 million, are not local authorities in the legal sense of the term since the state is a federation that comes from the Länder and not the opposite: the Länder, therefore, have all of the jurisdictions that are not explicitly attributed to the federation, such as defence and foreign policy. Note that the Länder, in particular, have the exclusive jurisdiction of defining the organisation of local authorities. The second level of local government comprises 323 Landkreise, which have a status somewhere between local government, groups of municipalities and the devolved scale of the Land. Lastly, Germany features 14 000 municipalities with an average population of 6 700 inhabitants.

Spain’s 3 levels of local authorities include 8 111 municipalities, 50 provinces and 17 autonomous communities. One feature of the provinces is that they provide technical assistance to municipalities of fewer than 5 000 inhabitants and participate in financing “supra-municipal” projects.

Portuguese multilevel governance model

It can be argued that Portugal belongs to the country group with one subnational government tier, i.e. the first country group. In Portugal, the municipality is a very old form of local administration and the parish, although also a very old form of organisation, initially a division within the organisation of the Catholic Church, is only part of subnational public administration since the liberal period in the 19th century. The number of municipalities reached 308 and the number of parishes 4 260, in 2013, when the reform of the parishes reduced its number to 3 091 units, as a result of the parish merger reform implemented by the XIX Constitutional Government. The merger reform was done in the context of the economic adjustment programme (2011-14), signed between the Portuguese government and the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund, in 2011, which stated on this issue the following: “central government should develop until July 2012 a consolidation plan for the reorganisation and significant reduction of the number of municipalities and parishes, in articulation with [European Commission] EC and [International Monetary Fund] IMF staff” (Nunes Silva, 2016[13]). In practice, this plan was applied only to the parishes, a reform process that has been questioned by the political parties that support the XXI Constitutional Government formed after the legislative election of 4 October 2015.

The regional tier of public administration in Portugal, between the state and municipalities, has a long history, comprising forms of decentralised as well as de-concentrated institutions (Nunes Silva, 2006[14]). In the 1976 constitution, the first form – political and administrative decentralisation – includes the Autonomous Regions of the Azores and Madeira, a form of political decentralisation, whose boards were first elected in 1976, and the administrative region, a form of administrative decentralisation, applied only to mainland Portugal. The motive for a model of political decentralisation in the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira was the recognition of the specific characteristics of these two regions, as is stated in the 1976 constitution. The implementation of administrative regions in mainland Portugal was however rejected in a national referendum in 1998.

In the case of administrative deconcentration, central government departments have been organised in regional or local tiers. Among them the particularly important case of the five regional planning and co‑ordination entities, the Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional (CCDR), one for each of the five NUTS 2 regions into which mainland Portugal is divided, namely because they were expected to be the support of the future administrative region, at least in some of the political proposals that have been put forward over the years.

The CCDRs carry out important missions in the areas of the environment, land and town planning, and regional development. One of their biggest missions is to manage regional operational programmes of European structural and investment funds on mainland Portugal for 2014-20. The CCDRs are managed by a president assisted by two vice-presidents, a single controller, intersectoral co‑ordination council and regional council. The president of each CCDR is thus appointed by the government from a list of three names drawn up by an independent recruitment and selection commission following a competitive application.

The Portuguese model in comparison with Finland, France and Poland

The Portuguese model appears to be a lot more centralised than the three cases presented, both institutionally and financially.

In the case of Finland, the Scandinavian model traditionally assigns the local level with a strong political capacity in terms of legal jurisdiction and financial autonomy. Compared with Finland, the Portuguese case features bigger municipalities with a low degree of administrative autonomy. Associations of municipalities have been created to counterbalance fragmentation, but do not constitute a genuine intermediate government capable of managing considerable land planning and economic development powers. Finnish co-operative regionalisation is in this respect original and constitutes a form of regional municipality councils. For this model to be efficient in Portugal, it would probably require working more strongly on the basis of associations of municipal co‑operation.

The French case is interesting for Portugal because both countries borrow from the Napoleonic model of public administration. However, France has a 30-year history of legal and financial decentralisation. Although public expenditure is still mostly centralised in France (80%), local and regional authorities are responsible for 57% of public investments. French municipal fragmentation is the highest in Europe. Consistent political decisions have thus attempted to reinforce intermunicipal associations and the regions by reducing their number and giving them greater authority.

Nevertheless, political impediments exist, and the overlapping institutions that still characterise the French system have the effect of making decentralisation relatively expensive (municipalities, intermunicipal co-operative units, departments, regions). If Portugal takes its inspiration from the French model, it should recognise the need to strengthen municipalities and make a choice between two types of intermediate government, i.e. “départements” or regions.

The Polish case differs from the Finnish and the French models since the financial capacities of regions in Poland are much lower. Poland provides, however, an interesting example of a relatively successful implementation of decentralisation reform. While it is not possible to measure precisely the effects of decentralisation on Polish society, Poland has performed well for example in the World Governance Indicator compared with its neighbours and other former communist countries.

As a result of the decentralisation reforms of 1990s and, thereafter, Poland has transformed from a very centralised country to a decentralised one. Thanks to decentralisation reforms in the 1990s, Poland is now considered the most decentralised country in Central and Eastern Europe. Between 1995 and 2014, the share of subnational government expenditure in total public expenditure increased by more than 9 percentage points, from 23% to 32%.

One key factor behind this success was the gradual and systematic way to implement the reform. New responsibilities have been transferred hand in hand with capacity building at the subnational level. In addition, new fiscal rules and territorial contracts have been introduced in order to control and co‑ordinate the decentralisation process. A considerable effort has been made to ensure that all stakeholders understand the reform goals and the likely outcomes. Therefore, training and information activities, often organised using non-governmental organisations, have had a key role in the reform implementation.

Although the Polish decentralisation reforms were decided very quickly after the collapse of communism, the implementation of the reforms has been sequenced. For instance, municipal self-governance was established first and the regional authorities were introduced at the second stage. An important aspect of the Polish reform is also that the revenues of subnational government were developed after the spending assignments were decided. The 2004 Act on Local Government Revenue modified the financing of subnational governments. Subnational governments gained more financial autonomy, with a decrease in the share of central transfers. The use of earmarked grants was especially reduced. At the same time, tax sharing on personal income tax and corporate tax revenues was introduced.

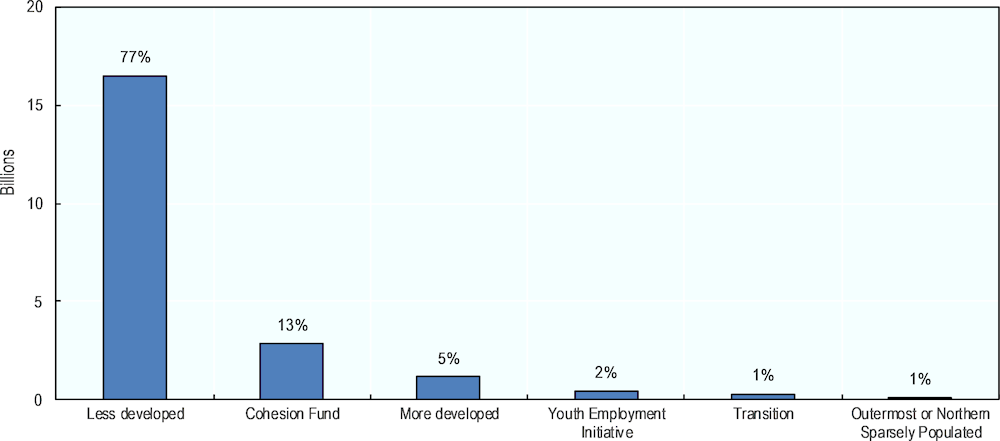

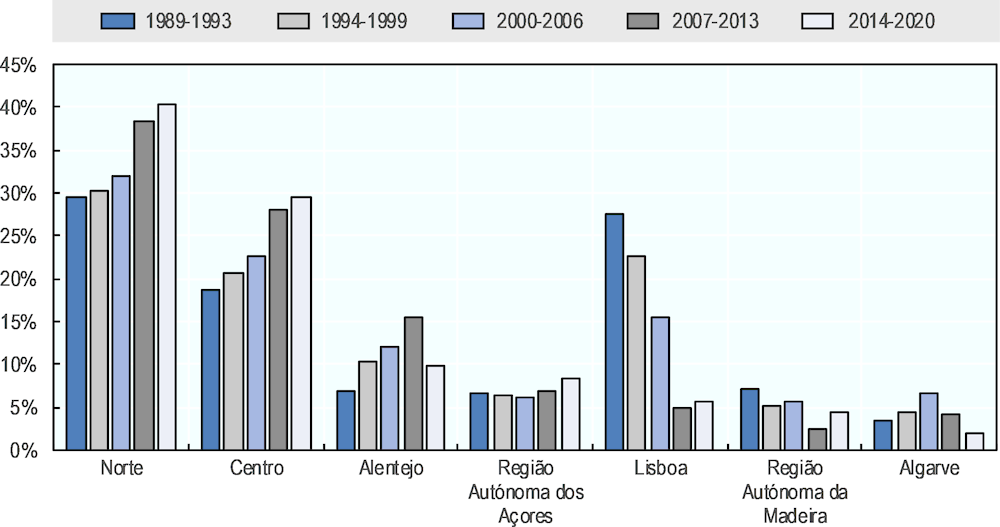

Regional development policy in Portugal

This section will focus on the regional economic issues of Portugal. The first subsection provides a brief discussion on the trends that will affect the regional policy in Portugal. The second subsection will discuss the key achievements and challenges of the current and future regional policy in Portugal.

Regional performance and disparities in Portugal

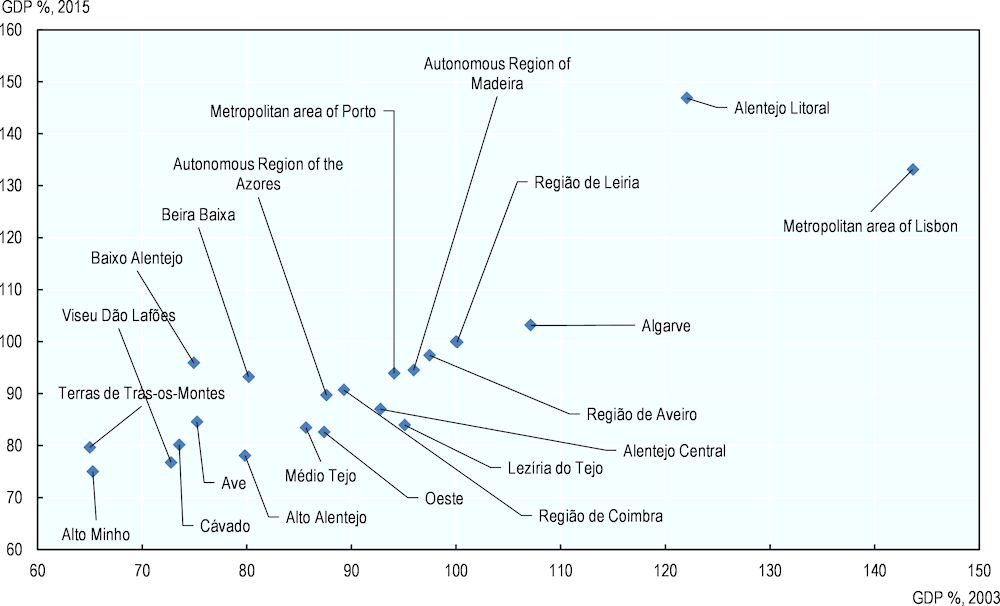

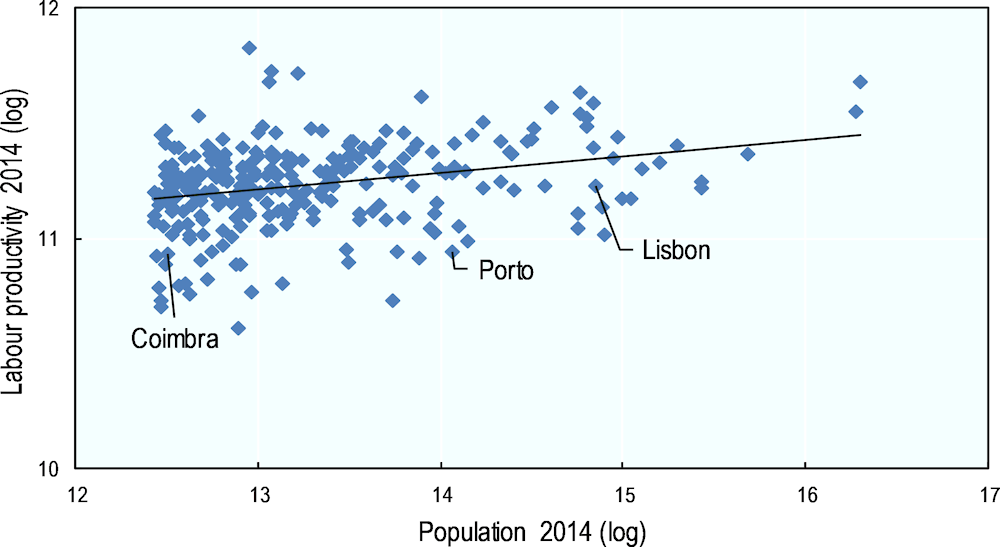

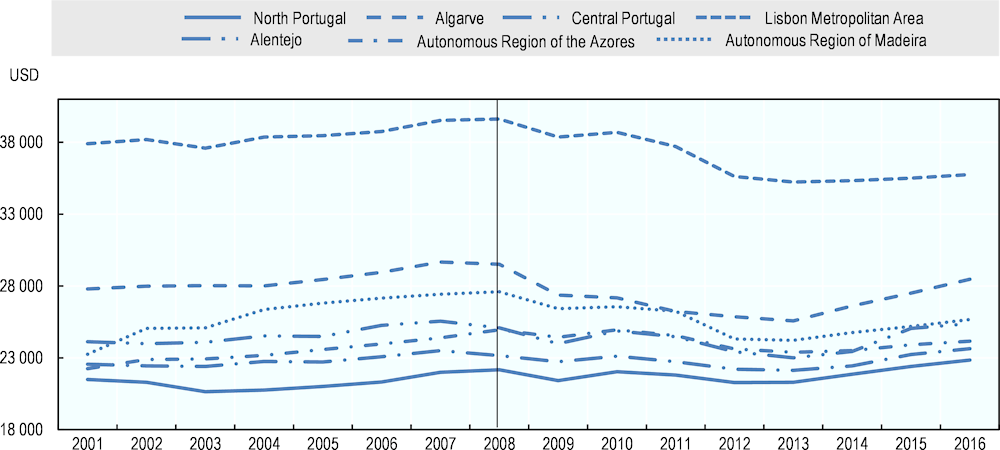

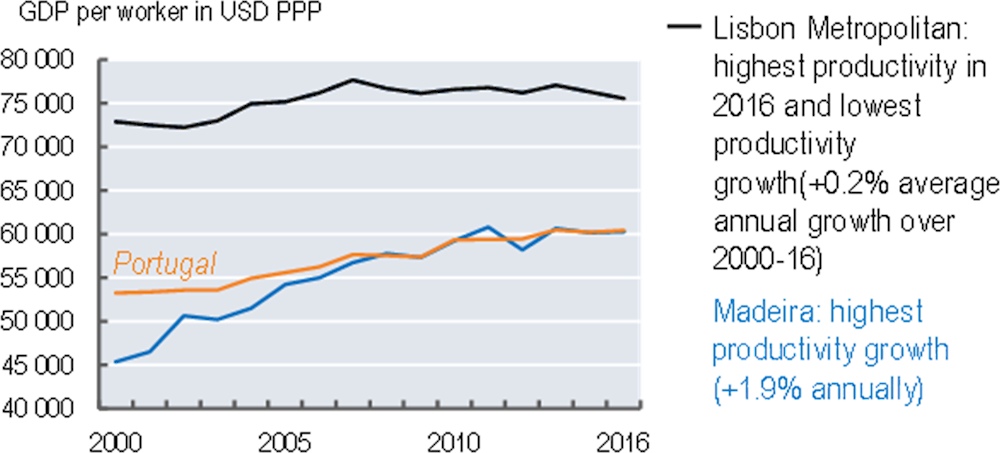

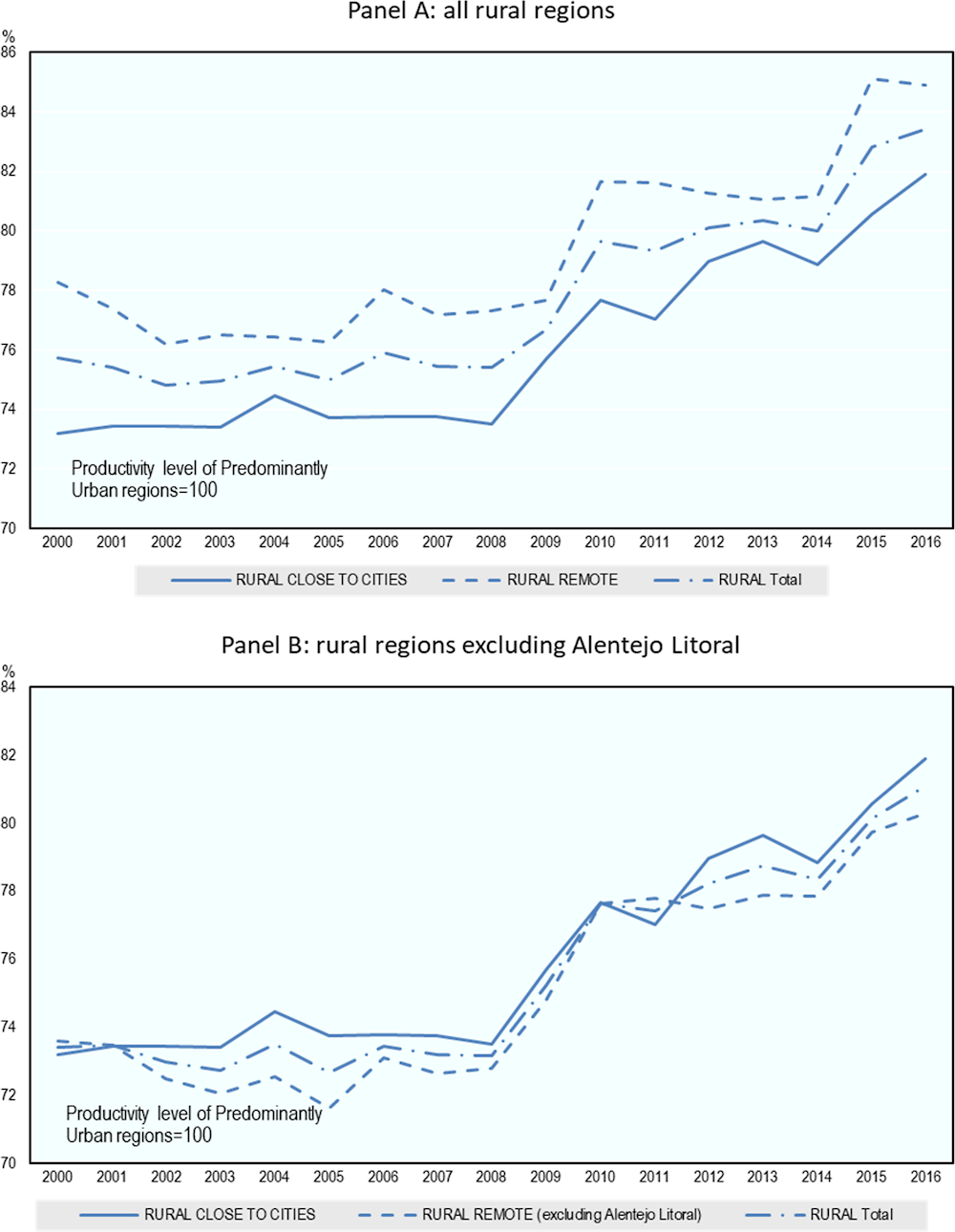

As underlined by the recent OECD Economic Survey, Portugal’s recovery is now well underway (OECD, 2019[15]). Its recent performance has been strong compared to other southern European countries, with exports as an important driving factor, including strong growth in tourism. GDP has now returned to pre‑crisis levels and the economy is expected to continue to expand at a stable pace. However, important challenges remain: long-term unemployment remains comparatively high; productivity growth has slowed over the past two decades; and overall, Portuguese citizens report low life satisfaction compared to their OECD peers. Portugal also continues to lag behind its peers in terms of the skills of its workforce, although younger cohorts are substantially more educated than older cohorts, thanks to extensive reforms to the educations system (OECD, 2018[16]). Additionally, while important progress has been made, a relatively high debt burden continues to limit the ability of governments to respond to future economic shocks.

At the regional level, economic performance and future constraints on growth vary. The Lisbon Metropolitan Area and Norte play an important role in Portugal’s economy – accounting for approximately two-thirds of Portugal’s GDP, yet Portugal’s two largest metropolitan areas, located in these regions, are not fulfilling their full potential as engines for its overall economy. Additionally, demographic changes will put considerable stress on labour markets, service delivery and public revenues, particularly outside of metropolitan areas. While a full accounting of the context, challenges and opportunities for regional development are beyond the scope of this exercise, the following section highlights some of the regional dynamics most relevant for the question of multilevel governance reforms.

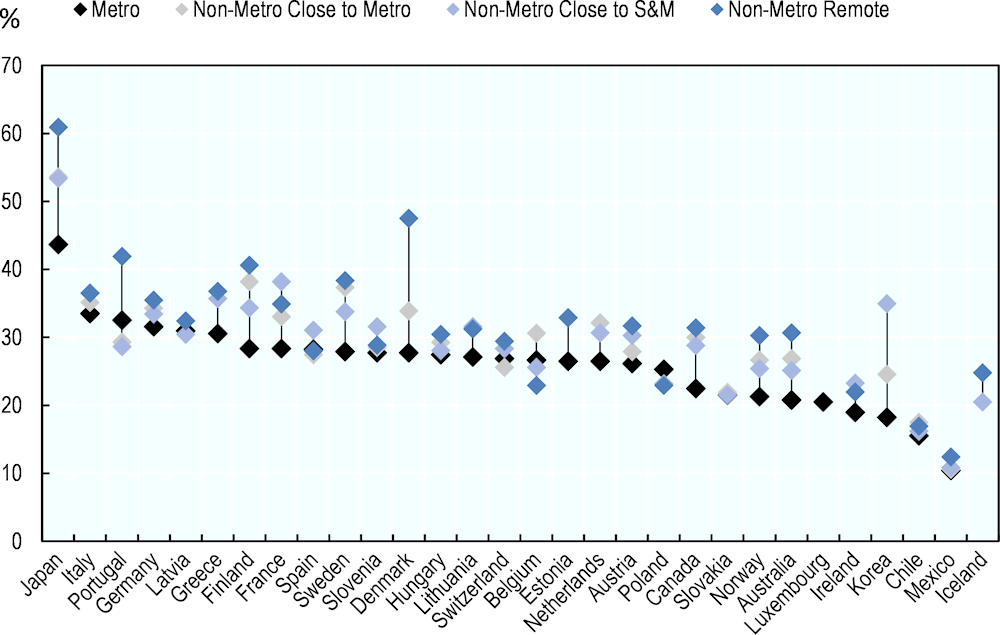

Demographic change poses long-term challenges, particularly in non-metro areas and in the north of Portugal

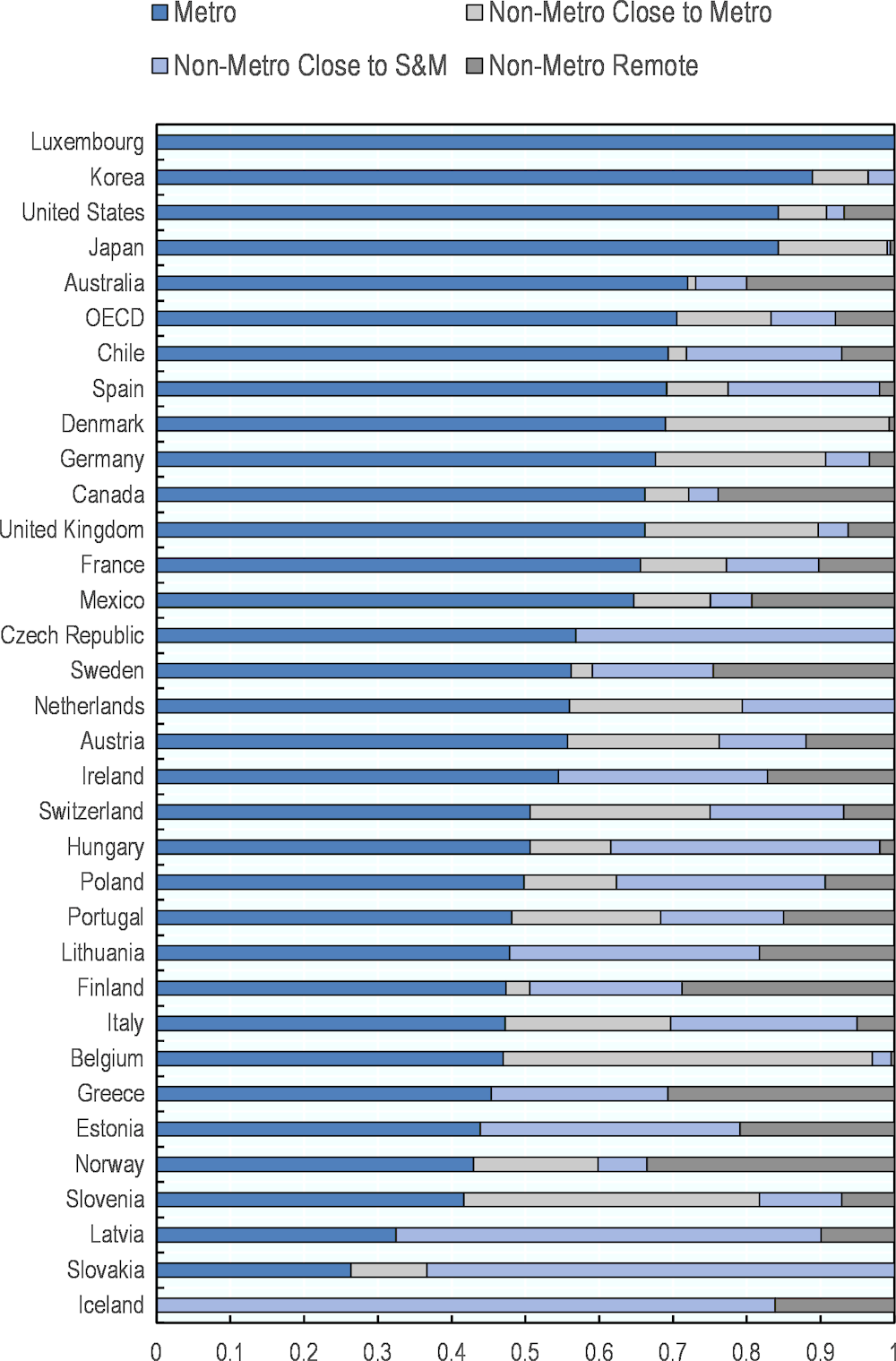

Slightly less than half of Portugal’s population lives in metropolitan TL39 regions (48%), compared to an OECD average of 71% (Figure 3.17, based on the OECD’s method of classifying TL3 regions in metro and non-metro according to their level of access to cities – see Box 3.4). Conversely, a larger share of Portugal’s population lives in non-metro remote regions (15%) compared to the OECD average (8%).

Figure 3.17. Distribution of population by type of region, 2016

Note: Metro is defined as the sum of classifications “metropolitan” and “metropolitan large”.

Sources: OECD (2019[17]), Regional Demography, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en; Fadic, M. et al. (forthcoming[18]), “Classifying small (TL3) regions based on metropolitan population, low density and remoteness”, OECD Regional Development Working Paper, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Box 3.4. An alternative OECD methodology to classify TL3 regions

In 2019, the OECD developed a methodology for classifying TL3 regions across OECD countries based on their level of access to metropolitan areas, based on publicly available grid-level population data and localised information on driving conditions. The figure below summarises this new methodology and the corresponding classifications for Portugal:

|

Metro/non-metro |

Sub-classifications |

Corresponding TL3 regions in Portugal |

|---|---|---|

|

Metropolitan region: 50% or more of its population lives in a metro (i.e. FUA 10of at least 250 000 inhabitants) |

Large metro region (metro large): 50%+ of its population lives in a large metro (i.e. FUA of at least 1.5 million inhabitants) |

Metropolitan Area of Lisbon |

|

Metro region (metro): 50%+ of its population lives in a metro but not a large metro |

Metropolitan Area of Porto Região de Coimbra |

|