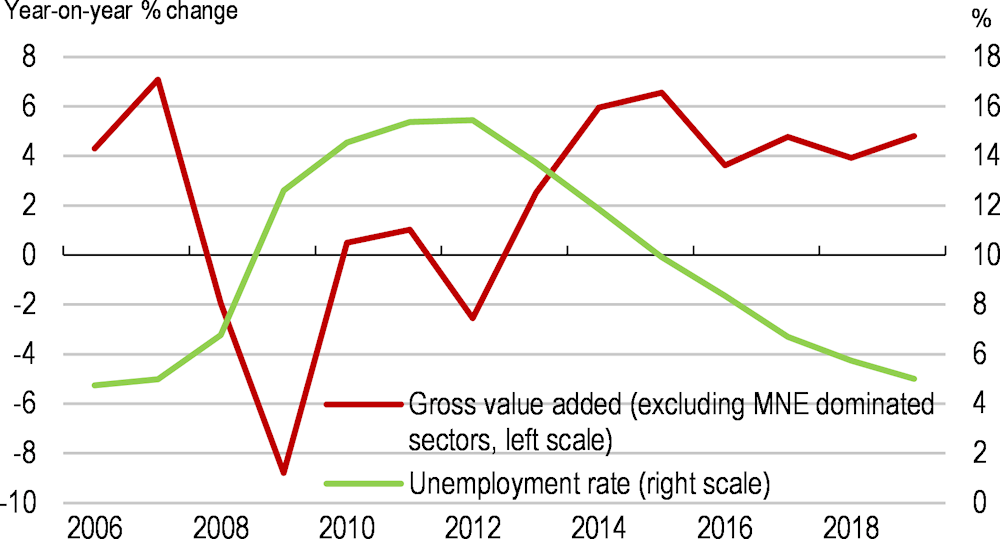

The Irish economy has been growing strongly. The unemployment rate has plummeted by over 10 percentage points since 2012 to around 5% (Figure 1) and the average real wage well exceeds the OECD average. Moreover, the highly redistributive tax and transfer system has contained income inequality. Air pollution is low and dimensions of wellbeing such as perceived personal safety and community engagement are high.

OECD Economic Surveys: Ireland 2020

Executive Summary

Life satisfaction is high, boosted by recent strong economic performance

Figure 1. The economy has performed well

Household consumption has grown steadily, but uncertainty has affected business investment. Job creation and wage gains have encouraged labour market participation. Even so, increased household income has been partly channelled to savings, amid weaker consumer confidence. The prospect of the United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union (“Brexit”) and the broader slowdown in major trading partners have held back investment. Although housing construction has forged ahead in the face of a dwelling shortfall, spending on non-aircraft machinery and equipment and intangible assets has stagnated since 2015.

Exports have supported the domestic economy. Services exports have been particularly strong but Brexit uncertainty appears to have weighed on sales of chemicals, tourism and some capital goods to the United Kingdom.

Economic growth will moderate, with risks elevated

Growth will moderate over the next two years, in the context of capacity constraints and weaker external conditions. The unemployment rate will decline more slowly, but to historically very low levels (Table 1). Labour market tightening will stoke wage pressures, especially in those sectors where labour shortages are most acute.

Table 1. Economic growth will moderate

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Real GDP |

6.2 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

|

Gross value added (exc. MNE sectors) |

4.8 |

3.5 |

3.4 |

|

Unemployment rate |

5.0 |

4.8 |

4.7 |

|

Core inflation |

0.9 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

Source: OECD. Based on the assumption of an orderly Brexit process.

Economic uncertainty will remain very high. Downside risks include an increase in barriers to trade between the United Kingdom and the European Union following the transition period, which could hobble trade activity between Ireland, the United Kingdom and the European Union, undermining domestic consumer and business confidence. Notwithstanding some decoupling in recent years, the United Kingdom remains a key trading partner for Ireland, particularly in the agriculture and food sectors. The nature of the trading arrangement eventually agreed will be an important determinant of Irish economic prospects over the next few years.

Increased protectionism, more generally, would hurt the very open economy. The impact of a negative shock could be exacerbated by high household debt and weak bank profitability, as well as still high general government debt.

The stock of non-performing loans on bank balance sheets remains high. A large share of those that remain stems from long-term owner-occupier housing arrears. These will be difficult to resolve, partly due to slow repossession proceedings, but may be sped up through granting lenders a collateral possession order at a future date.

The high share of foreign-owned firms in Ireland is a great asset but also a downside risk to the economy and tax receipts. Such businesses are typically much more productive than their locally-owned counterparts and often have weak supply-chain links with domestic firms. Rising international tax competition and future international tax agreements as part of the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting process could lower the attractiveness of Ireland to foreign direct investment. This highlights the importance of fostering technological adoption and productivity in domestic firms as well as further skill improvements in the workforce.

Fiscal prudence calls for saving windfall tax receipts. Recent improvements in Ireland’s fiscal position have largely reflected unexpected corporate tax receipts and interest savings. Non-recurring receipts have been partly used to fund within-year cost overruns in areas such as health and social welfare. Going forward, the government should commit to transferring windfall tax revenues to pay down general government debt or to the Rainy Day Fund. In the event of an orderly Brexit process, the stance of fiscal policy should be tightened somewhat.

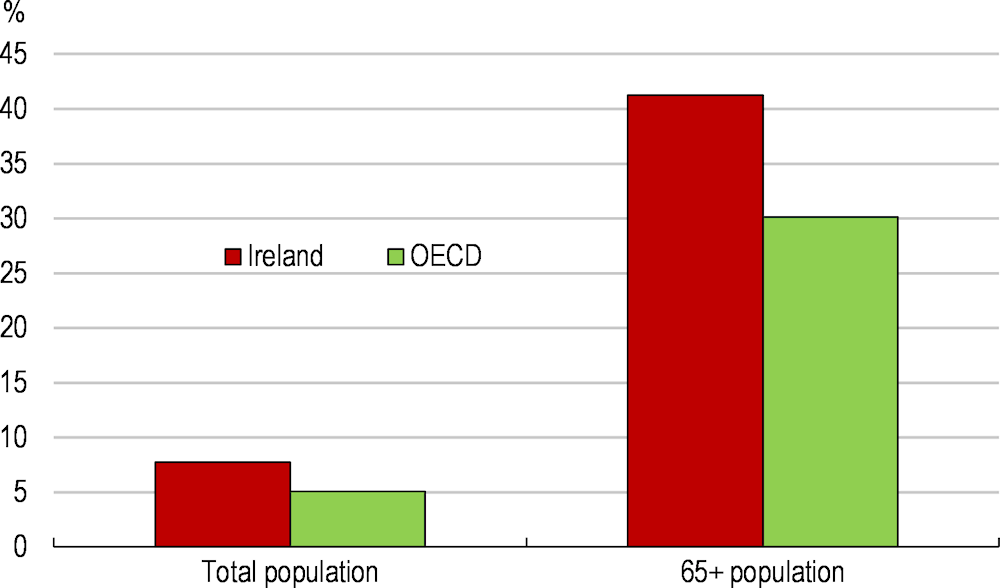

The rapidly ageing population will pose new challenges

Ageing will push up public spending and reduce revenues from labour taxes. The population aged over 65 is expected to grow much more rapidly than in most OECD countries (Figure 2). Simulations suggest that public health and pension costs could rise by 1½ per cent of GDP by 2030 and by 6½ per cent of GDP by 2060. To meet these obligations, opportunities for greater public spending efficiency and revenue sources that minimise economic distortions need to be identified.

Figure 2. The population is ageing fast

Projected percentage change, 2018-2030

Enhanced public spending efficiency is achievable. Health spending per capita is high and recent spending increases have not resulted in greater measured outputs. Budget planning in the health service needs to improve, partly through better adherence to key legislative requirements of budget plans. At the same time, Ireland is the only Western European country without universal coverage for primary healthcare. This contributes to poor disease management and congestion in hospitals. A clearer path to universal access to primary healthcare must be spelled out.

New revenue sources to meet the fiscal costs of ageing should come from tax heads that are less distortionary for economic activity. For instance, recurrent property taxes and consumption taxes could be relied upon more. The authorities should more regularly revalue the local property tax base and streamline the Value Added Tax system, moving from five rates to three. In so doing, the impact on low-income households should be carefully monitored and offsetting policy measures may be needed.

Environmental costs should be better reflected in prices. Environment-related taxation remains low even as Ireland is unlikely to achieve its carbon emission reduction targets for 2020 or 2030. The authorities made welcome progress by raising the carbon tax rate in Budget 2020. Nevertheless, further carbon tax rate hikes will be needed. These should be coupled with other measures such as congestion charging in the busiest locations, abolishing preferential VAT rates for synthetic fertilisers and reforms that mitigate emissions from agriculture, such as greater afforestation.

Further technological diffusion presents opportunities but also policy challenges

Technological change is transforming Ireland’s economy, leading to new jobs and innovative products that benefit consumers. Further technological adoption by firms will boost productivity if the right skills are available. Policy settings in other areas, including competition and the labour market, need to also be revisited as new technologies spread.

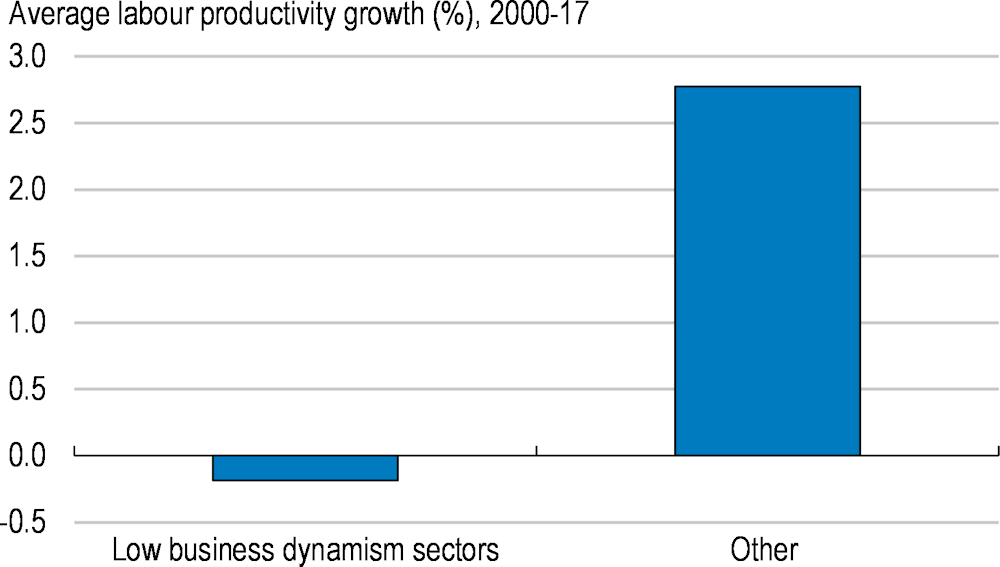

The adoption of new technologies has been uneven across sectors and has had scant productivity impact. Sectors with low firm entry and exit rates have experienced no improvement in labour productivity since 2000 (Figure 3). Further reducing barriers to firm entry will prompt productivity-enhancing technological adoption. Licensing procedures for businesses should continue to be simplified and regulations that restrict the provision of legal services reformed.

Figure 3. Efficiency has not improved in sectors with low firm turnover

Note: Sectors in the bottom third of the distribution for business churn (sum of firm entry and exit) are deemed low dynamism.

Source: CSO, OECD calculations.

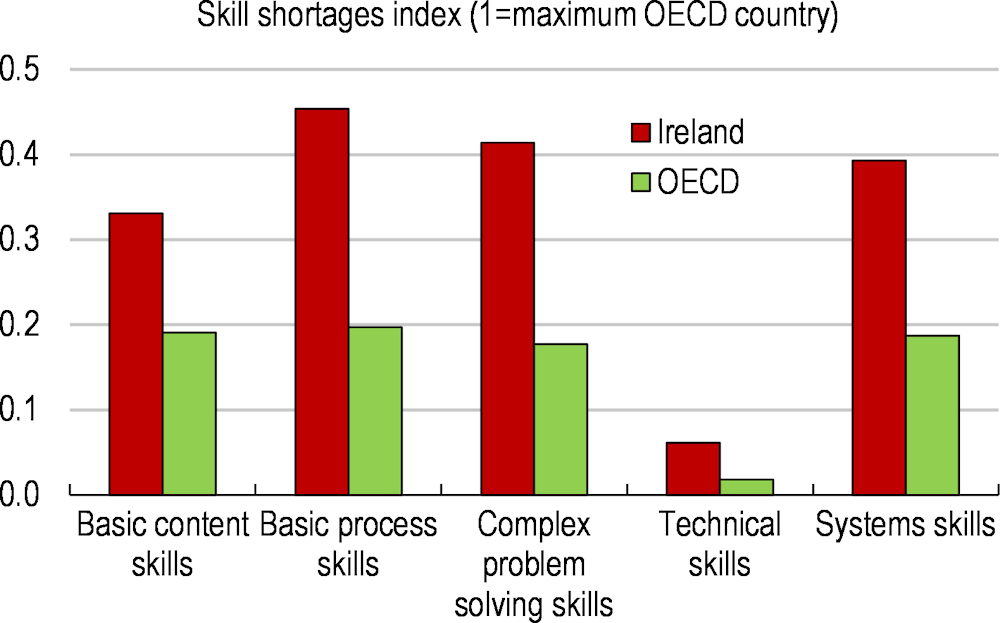

Skill shortages are becoming more apparent (Figure 4). Participation in lifelong learning by the low-skilled is low, partly because many see it as unnecessary and unaffordable. Irish businesses also provide less training to employees than those in other OECD countries. To realise the productivity gains made possible by new technologies, complementary skills need to be cultivated. The government should enhance financial assistance for training programmes and fully implement measures that lower barriers to participation, such as promoting flexible working hour arrangements, including through ensuring adequate and affordable childcare. The latter may also promote female labour force participation given that the gender gap in unpaid work hours remains large.

Policies need to adjust to new types of work. Online platforms can be a channel through which technology creates new jobs and allows more flexible work arrangements. However, these new forms of work create challenges for traditional labour market and social welfare institutions that were created based on stable and ongoing employer-employee relationships. Labour market regulations should be broadened to fully cover workers in the “gig economy” and social protection should be harmonised across different types of employment. This will protect the work standards and bargaining power of employees, thereby promoting participation in such work.

Figure 4. Skill shortages are more pronounced

Note: Positive values represent shortages, with the maximum and minimum values among OECD countries normalised to 1 and -1.

Source: OECD Skills for Jobs database.

New technologies have the potential to displace some workers. Indeed, new analysis undertaken for this Economic Survey indicates that growth in the intangible capital stock has been associated with an increase in job losses in some sectors. Policies should support the reallocation of workers to new parts of the economy that are thriving. This could be through new training programmes targeted at employees in those enterprises with a high risk of dismissing workers in the near future due to technological change. Social protection systems that support displaced workers and reorient them towards new jobs should continue to be fine-tuned. Robust evaluations of the effectiveness of activation programmes will be particularly important.

Regional inequalities have been rising, with Dublin accounting for a larger share of economic activity. Nevertheless, the Dublin-born population is increasingly moving to other counties due to escalating dwelling prices in the capital. The reallocation of workers to new high-growth industries will benefit from policy measures that further boost housing supply in thriving regions. These include replacing some existing taxes on market property values, such as stamp duty, with a broad-based land tax to incentivise both labour reallocation and efficient land use. At the same time, policy measures such as Ireland 2040 are important for establishing strong economic poles outside of Dublin with specialisations that reflect regional endowments.

Competition policies also need to be recalibrated to reflect a more technologically-rich environment. Unique features of digitally-intensive markets, including substantial network effects, could negatively impact competitive dynamics. There has been less start-up activity in Ireland’s digitally-intensive sectors than in other parts of the economy in recent years. Competition authorities should ensure that they have the capacity to closely monitor developments in emerging digital markets. They should also be given adequate enforcement powers to fight anti-competitive behaviour, including the capacity to impose sufficient penalties on competition law infringements to ensure a deterrent effect.

|

MAIN FINDINGS |

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS |

|---|---|

|

Raising fiscal sustainability |

|

|

With robust underlying economic activity and emerging capacity constraints, fiscal policy has been too loose in recent years. Windfall corporate tax receipts have been partly used to fund within-year cost overruns. |

Fiscal policy should be tightened somewhat in the event of an orderly Brexit process. Use windfall corporate tax revenues to pay down general government debt or to further build up the Rainy Day Fund. |

|

Ireland’s upwardly distorted GDP, which relates to the activities of multinational enterprises, contributes to an overly benign assessment of the fiscal position when judged against the fiscal rules of the EU Stability and Growth Pact. |

Create domestic fiscal rules based on measured modified gross national income (GNI*) and an estimate of potential output growth that is tailored to the Irish context. Continue to set, and report progress against, medium-term government debt targets as a share of GNI*. |

|

Ireland relies less than other countries on more efficient tax sources, such as consumption taxes and recurrent taxes on immovable property. The local property tax is currently levied on 2013 market values. |

Streamline the Value Added Tax system, moving from five rates to three. Reassess property values more regularly for the purposes of calculating the local property tax. At the same time, protect those low-income households adversely impacted. |

|

The population is expected to age rapidly over the coming decades. Ireland is the only Western European country that does not have universal coverage for primary healthcare. A two-tier system exists whereby those with the ability to pay for treatment privately get faster access to care in public and private hospitals. A lack of capacity in both primary and secondary care contributes to long waiting times for treatment. |

Implement the main proposals of the Sláintecare report, establishing a single-tiered health service that provides universal access to primary care. |

|

The health sector has seen repeated expenditure overruns since 2015. Key legislative requirements are not being met related to the National Service Plan, which is the main tool for budget planning used by the Health Service Executive. |

Ensure that all legislative requirements for the National Service Plan are fulfilled by the Health Service Executive. |

|

Maintaining financial stability |

|

|

The non-performing loan ratio in the banking sector has declined notably. Nevertheless, it remains elevated relative to European peers. Furthermore, many of the remaining non-performing loans will be difficult to cure, partly due to slow repossession proceedings. |

Consider granting lenders a collateral possession order for a future date. |

|

Only around one-third of fintech firms are regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland. Other fintech firms have no reporting obligations. |

Ensure regulators have the power to obtain relevant information from unregulated financial service providers. |

|

Better protecting the natural environment |

|

|

Environment-related taxation remains low and Ireland will not achieve its carbon emission targets by 2020 or 2030. However, an increase in the carbon tax will be regressive. |

Gradually raise the carbon tax rate according to a schedule that is well communicated to households and businesses. Use some of the revenues from an increase in the carbon tax rate to fund new green investment and measures that offset any adverse distributional effects. |

|

The agriculture sector is the largest single contributor to Ireland’s greenhouse gas emissions. |

Pursue full and early implementation of cost effective measures for the abatement of carbon emissions from agriculture, particularly those related to afforestation. |

|

Promoting inclusive technological diffusion |

|

|

Promoting greater business dynamism is key to encouraging the uptake of new technologies Regulatory burdens on start-ups are relatively onerous in Ireland, due to complex regulatory procedures and the system for licenses and permissions. |

Monitor business licensing requirements and the systems that facilitate them, including by linking more licensing procedures with the Integrated License Application Service. |

|

Participation in lifelong learning by adults is low. |

Enhance financial assistance for training programmes for young workers. More actively establish and promote distance learning programmes. Couple adequate public financial support for childcare with measures to expand childcare capacity. |

|

Gaps in the coverage of social protection and labour market regulations between dependent employees and self-employed workers can distort choices around the form of employment, erode the social protection base and undermine the bargaining position of platform workers. |

Require those freelance platform workers who are effectively dependent employees to pay a Pay-Related Social Insurance premium equivalent to that paid by dependent employees and introduce an employer contribution. |

|

Unique features of digital markets, including substantial network effects, may be negatively impacting competitive dynamics. |

Give the Irish Competition and Consumer Protection Commission adequate enforcement powers to fight anti-competitive behaviour, including the capacity to impose sufficient penalties on competition law infringements to ensure a deterrent effect. |