Digital Government Review of Slovenia

1. Contextual factors and institutional models

Abstract

This chapter analyses and assesses the governance for digital government in Slovenia focusing on the contextual factors and institutional models that underpin the digital transformation of the public sector in the country. The first two sections review the overall political and administrative culture as well as socio-economic factors and the technological context that determine Slovenia’s path towards digitalisation of the public sector. A third section focuses on macro-structure and leading public sector organisation in charge of digital government policy. The fourth and last section discusses the existing co-ordination and compliance mechanisms meant to secure policy coherence and alignment across sectors and levels of government.

Introduction

Given the rapid and disruptive digital progress transforming economies and societies, governments around the world face the challenge of using digital technologies and data throughout the public sector to spur productivity, to design and deliver user and data-driven policies and services in expectation of creating public value and facilitating the day-to-day life of citizens. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced this trend, highlighting the importance of investment in digital transformation to demonstrate the resilience, responsiveness and agility required of public sector organisations. Public sectors are expected to adjust quickly and without interruption to continuously generate public value in an inclusive and fair way. In order to enhance the impact of the digital transformation, government-wide cohesive approaches are essential.

This can be achieved through the establishment of a governance framework that secures sound leadership, strategic coordination and the involvement of a stakeholder ecosystem drawn from both inside and outside government, to enable administrations to ensure coherent and sustainable implementation of digital government policies. Therefore, it is as important for the governance framework to support digital transformation to fit the national context as it is to secure the necessary financial investment..

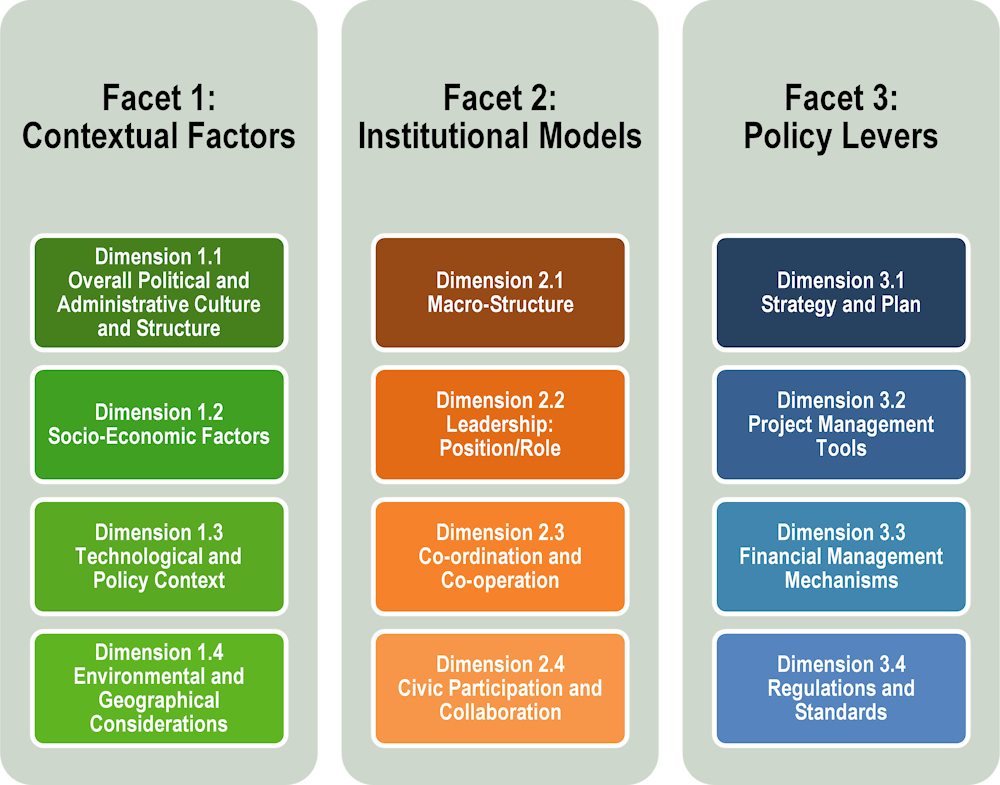

Building on the knowledge and experience of OECD member and non-member countries, the E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government provides a framework to guide policy makers in assessing and improving their digital governance principles, arrangements and mechanisms that would ultimately contribute to bettere design, co-‑ordination and implementation of digital government policies (see Figure 1.1). Additionally, it offers policy options and recommendations based on global good practices with the idea that no single solution fits all (OECD, forthcoming[24]).

The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government presents three governance facets:

Contextual factors that provide a definite knowledge of country-specific characteristics and define the most suitable governance principles, arrangements and mechanisms according to the domestic social, economic and political conditions (applied to the Slovenian context and analysed in Chapter 1);

Institutional models that defines the institutional set-up and mechanisms in place (e.g. leadership, responsibilities, co-ordination, collaboration) that guide the design and implementation of digital government policies and achieve a sustainable digitalisation of the public sector (applied to the Slovenian context and analysed in Chapter 1);

Policy levers that support the coherent implementation of digital government strategies and use of digital technologies across policy areas and levels of government (applied to the Slovenian context and analysed in Chapter 2).

Figure 1.1. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government

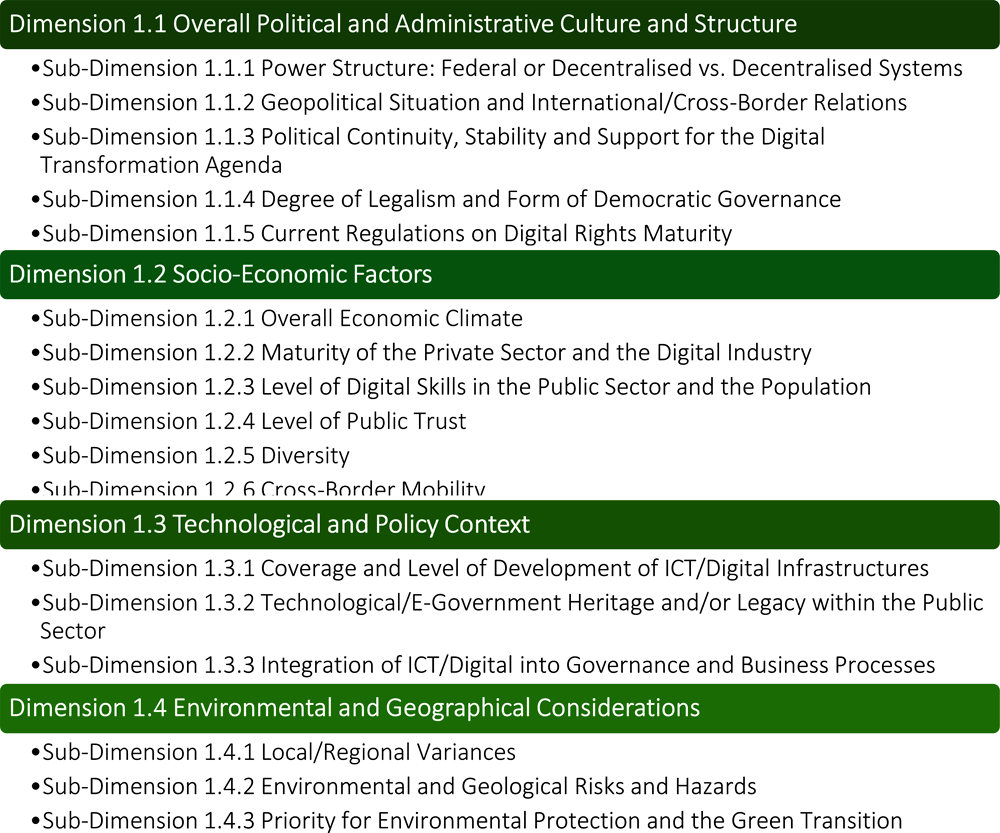

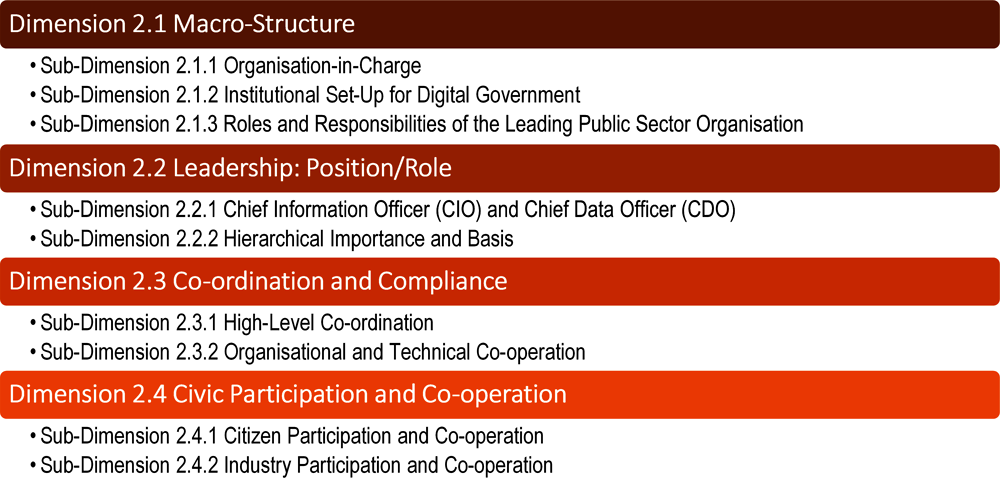

The current chapter applies the first two facets of the E-Leaders Governance Framework – contextual factors and institutional models (see Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3) – to the Slovenian digital government landscape. The analysis starts by assessing and discussing the overall political and administrative culture in place, including sub-dimensions such as the country’s power structure, the existing political continuity and stability, as well as the level of centralisation/decentralisation of the Slovenian public sector. The second section analyses the socio-economic factors and technological context in the country, including Slovenian’s well-being1, the levels of digitalisation across the population and the overall maturity of digital government. The third section focuses on macro-structure and the public sector organisation leading the digital government policy in Slovenia, analysing its mandate, role, practises and recognition across the Slovenian public sector. The last section of the chapter concentrates on the co‑ordination and compliance mechanisms in place to secure a coherent and sustainable digitalisation of the Slovenian public administration.

Figure 1.2. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government: Contextual factors

Figure 1.3. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government: Institutional models

Overall political and administrative culture

The administrative and institutional features of countries vary substantially, and this can represent different opportunities or challenges for policy implementation. The geopolitical situation, the various possible structures of the executive branch, the division of power between the central and sub-national levels of government, as well as political stability and continuity are variables that determine how policy approaches need to be designed and implemented in order to be effective. This institutional variety among countries explains why successful policy approaches in one country cannot necessarily be replicated in different contexts. When considering OECD member countries, this institutional diversity is naturally high, determining different grounds, paths and models for digital government policy development.

Slovenia is a parliamentary democratic republic with a population of approximately 2.1 million inhabitants of a geographically small stature (the fourth smallest in the European Union (EU)). Since independence in 1991 the country has benefitted from stable international relations with its neighbours, both in the broader European context and in the Balkans region. A former Yugoslavian republic, the country quickly achieved democratic political stability, implementing the necessary social and economic reforms to help Slovenia progressively strengthen relations in the European continent. Slovenia’s accession to the OECD in 2010 reflects impressive political, economic and social progress in the two decades following independence.

The government system is based on a president – head of state – directly elected by universal suffrage and a prime minister – head of government – elected by the parliament with mandates of four years. However, since independence, the longevity of governments has been relatively short: only exceptionally have governments completed their four-year mandates. This follows from the country’s parliamentary system where government longevity depends on a parliamentary majority to support it and it being rare for any single party to secure an absolute electoral majority. In thirty years of independence Slovenia has already had 14 governments (see Table 1.1). Although the democratic system is stable, the limited duration of governments and political cycles are a policy challenge identified by public and private stakeholders during the OECD fact-finding mission held in Ljubljana in October 2019. Changes to political leadership at a government level contributed to changing policy priorities. The frequent need of the Slovenian public sector to respond to new policy orientations is a challenge to stable, coherent and durable policy development in several critical digital government areas including interoperability policies, digital identity approaches or coherent approaches to service design and delivery.

Table 1.1. List of governments in Slovenia between 1990 and 2021

|

Government |

Prime minister |

Start of term |

End of term |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1st |

Lojze Peterle |

16 May 1990 |

14 May 1992 |

|

2nd |

Janez Drnovšek |

14 May 1992 |

25 January 1995 |

|

3rd |

25 January 1995 |

27 February 1997 |

|

|

4th |

27 February 1997 |

7 June 2000 |

|

|

5th |

Andrej Bajuk |

7 June 2000 |

30 November 2000 |

|

6th |

Janez Drnovšek |

30 November 2000 |

19 December 2002 |

|

7th |

Anton Rop |

19 December 2002 |

3 December 2004 |

|

8th |

Janez Janša |

3 December 2004 |

21 November 2008 |

|

9th |

Borut Pahor |

21 November 2008 |

10 February 2012 |

|

10th |

Janez Janša |

10 February 2012 |

20 March 2013 |

|

11th |

Alenka Bratušek |

20 March 2013 |

18 September 2014 |

|

12th |

Miro Cerar |

18 September 2014 |

13 September 2018 |

|

13th |

Marjan Šarec |

13 September 2018 |

13 March 2020 |

|

14th |

Janez Janša |

13 March 2020 |

Source: Wikipedia (2020[25]), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_governments_of_Slovenia (edited 17 March 2020), based on Vlada Republike Slovenije, https://www.gov.si/drzavni-organi/vlada/o-vladi.

Regarding territorial administration, Slovenia has been considered a decentralised unitary state since 1993, with 12 regions and 212 municipalities. The country’s sub-national levels of government benefit from strong autonomy in policy areas such as internal affairs, traffic, construction and agriculture. (European Committee of the Regions, 2021[26]) Nevertheless, when compared to OECD countries, Slovenia has a relatively centralised administration. The central government has national legislative powers in all policy areas, and state authorities supervise the legality of the work of sub-national levels of government. Considering the size and relatively homogenous territory, the fact that the administration model is relatively centralised can be an asset for coherent and sustainable digital government policy development. Provided that space is left to address sub-national specificities, clear policies from central government can in principle be quickly adopted throughout the territory, avoiding policy fragmentation and pulverised implementation.

Slovenia has been a member of the EU member since 2004 and a member of the Schengen area since 2007. Its legal, regulatory and administrative context in the areas of digital economy, society and government is strongly influenced by existing EU policies. The European directives and regulations in these policy areas applied in the country determine the philosophy and fabrics of Slovenian digital transformation. This policy integration and context stimulate strong co‑operation and synergies with other EU member states. Given that Europe is one of the leading actors of the worldwide digital transformation underway, Slovenia has strongly benefited from its EU membership, allowing its public sector to join efforts and keep the pace of development of other member states.

In line with its European peers, Slovenia has also benefited from considerable EU financial support for the development of its digital government. The EU has consistently funded its member states digitalisation efforts, at least since the approval of the Lisbon Strategy, launched in March 2000 by the European heads of state and government in order to make Europe "the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion" (European Parliament, 2021[27]). Numerous European strategies, actions plans, initiatives and projects have guided strong funding mechanisms that have allowed EU member states to consistently invest in the digital transformation of different social and economic sectors. The European public sectors have benefited from important investments, and Slovenia has not been immune to these strong and consistent investment efforts.

In this sense, the contextual political and administrative culture generally favours digital government development in Slovenia. As a geographically small, relatively centralised country that is strongly involved in European co‑operation, Slovenia has the capacity to move fast, in an agile manner, and to quickly leapfrog digital government maturity stages. The country’s government should increasingly consider these contextual factors as comparative assets of the digital government policy and properly leverage them for improved public processes and services.

Socio-economic factors and technological context

Understanding, considering and leveraging the socio-economic, technological and geographic context of a country is fundamental for a sound digital government policy. The governance in place needs to take into account fundamental contextual factors such as the overall economic climate, the levels of digitalisation within the population and adoption of digital public services, the coverage and development of information technology (IT) infrastructures, but also the regional variances and the heterogeneity of local economies.

Slovenia performs around the EU average when considering gross domestic product per capita in purchasing power standards (European Union, 2021[28]). Since its independence from former Yugoslavia, the country has benefited from continuous economic growth that has allowed improved living standards for its population. Although the financial crisis in late 2000 had strong impacts on the country and the current COVID-19 pandemic context probably threatens gains made over the past five years (OECD, 2020[29]), Slovenia ranks 22nd on the United Nations Human Development Index (UNDP, 2020[30]).

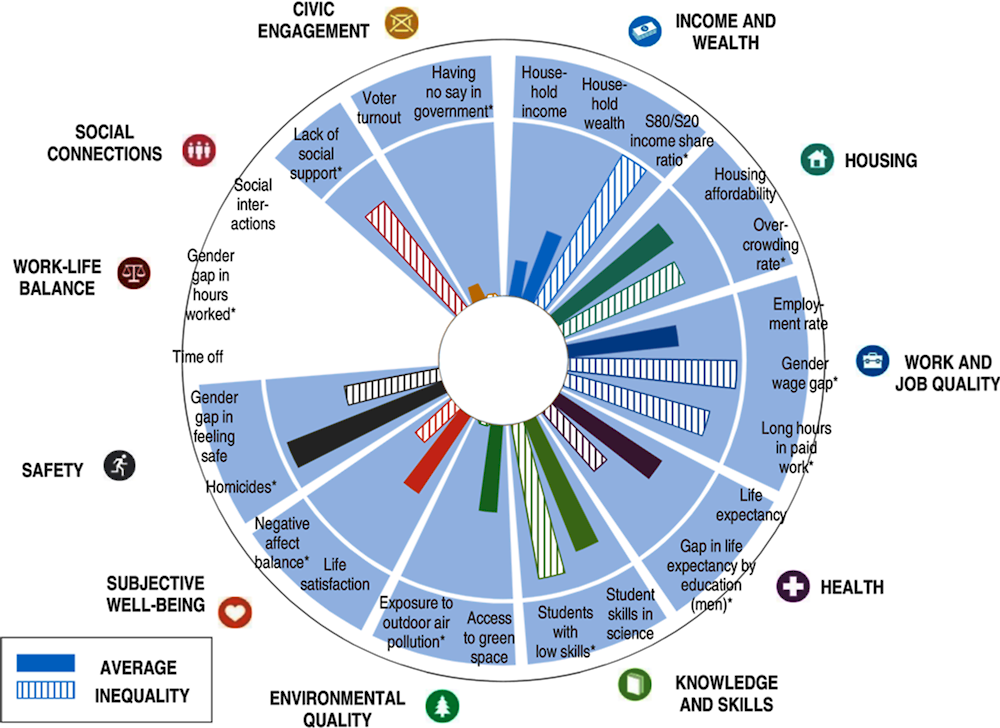

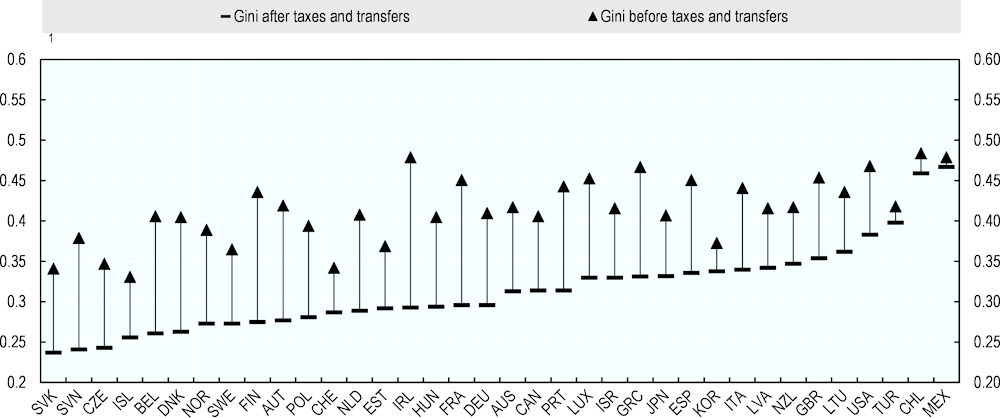

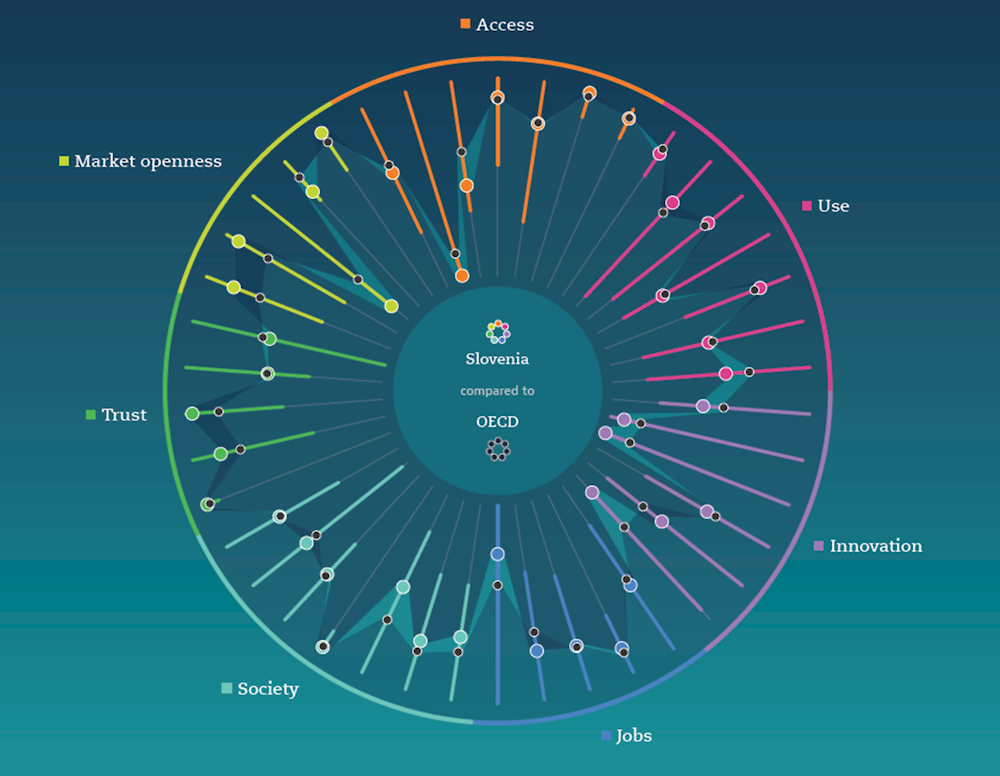

The country presents positively evolving well-being standards according to the OECD How's Life? 2020 report (OECD, 2020[2]). As can be seen in Figure 1.4, areas of high well-being in the OECD context relate to levels of housing affordability, work and job quality, health, knowledge and skills, as well as safety. It is also important to notice that Slovenia is one of the top OECD performers in the Gini coefficient (that measures the distribution of income across population), with taxation being an important variable in reducing social inequality in the country (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.4. Slovenia’s current well-being, 2018 or latest available year

Note: This figure shows Slovenia’s relative strengths and weaknesses in well-being compared to other OECD countries. Longer bars always indicate better outcomes (i.e. higher well-being), whereas shorter bars always indicate worse outcomes (lower well-being) – including for negative indicators, marked with an *, which have been reverse-scored. Inequalities (gaps between top and bottom, differences between groups and people falling under a deprivation threshold) are shaded with stripes, and missing data are in white.

Source: OECD (2020[2]), “How’s Life in Slovenia?”, in How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

Figure 1.5. Social inequality – changes in the Gini coefficient due to taxation and transfers, working-age population, 2017 or latest available year

Note: The Gini coefficient has a range from zero (when everybody has identical incomes) to one (when all income goes to only one person). An increasing Gini coefficient indicates higher inequality in the income distribution. Data for Australia and Israel are from 2018, and data for Slovenia are from 2017

Source: OECD (2021[31]), OECD Income Distribution Database, www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm

However, the most identifiable challenges for the well-being of the country relate to voter turnout and participation in government affairs, as well as household health and household income (Figure 1.4). The OECD Economic Survey of 2020 also identified the ageing of the Slovenian population as one of the biggest challenges the country faces in the middle term. For instance, the old-age dependency ratio that measures the share of the population older than 65 over the working-age population (20-64 years old) in Slovenia is projected to reach 60% in 2055. This forecast scenario shows that policies to tackle an ageing population are one of the priorities the country should consider adopting once the COVID-19 post-recovery has become self-sustained (OECD, 2020[29]).

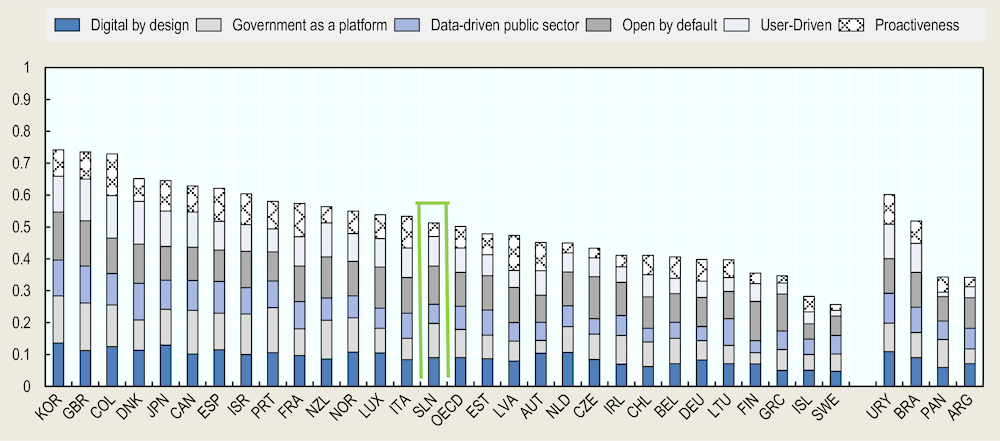

The observed human development and well-being are important underlying conditions that favour Slovenia’s reasonable levels of economic and social digitalisation when compared with OECD countries. According to the OECD Going Digital Toolkit (Figure 1.6),2 in the dimension of access to communications infrastructures, services and data, the country performs very well in 4G broadband coverage and household broadband access. Mobile broadband mobile penetration is nevertheless an indicator where Slovenia performs clearly below the OECD average (a score of 47 for Slovenia against the OECD average of 64). The country performs reasonably well on effective use of digital technologies and data, with good scores, for instance, in businesses with a web presence or people buying online. Digital market openness is high in Slovenia, with good scores when compared with the OECD average, for instance, in cross-border e-commerce. It is also important to notice that 87% of Slovenians aged between 16 and 64 use the Internet, which corresponds exactly to the average of the EU.

Figure 1.6. Going Digital – Slovenia

Source: OECD (2020[4]), OECD Going Digital Toolkit (database), https://goingdigital.oecd.org/ (accessed December 2020).

Note: M2M stands for Machine to Machine. STEM stands for science, technology, engineering and math. FDI stands for foreign direct investment.

The biggest limitations highlighted by the OECD Going Digital Toolkit refer to the data-driven and digital innovation policy dimension. Whether considering information and communications technology (ICT) investment intensity, research and development in information industries, ICT venture capital investment or ICT patents, the country performs always considerably below the OECD average. Although these innovation indicators reflect mostly private sector performance, they can also mirror structural innovation-adverse contextual factors that affect the public sector practice and culture. In fact, during the fact-finding mission organised in Ljubljana in October 2019, as well as in the capacity-building workshop on digital talent and skills held remotely in December 2020, the limited public sector innovation culture was frequently highlighted as a challenge by various Slovenian stakeholders involved.

The good levels of digitalisation of the Slovenian economy and society can be seen in increasing online interaction with government. In 2005, only 19% of individuals were using the internet to visit public authority websites in Slovenia but by 2020 that figure had progressed to 67%, well above the EU average of 56% (OECD, 2020[4]). Box 1.1 describes the OECD approach to determining digital government maturity against which the Digital Government Index is measured and the results of which in Figure 1.7 show Slovenia performing slightly above the OECD average ranking 15th of 29 OECD countries, and 7th among 19 participating EU countries (OECD, 2020[15]).

Box 1.1. OECD Digital Government Policy Framework and Digital Government Index

The Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[32]) underscores the paradigm shift from e-government to digital government required to realise the digital transformation of the public sector. The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework (OECD, 2020[14]) builds on its provisions to help governments identify the key factors for effectively designing and implementing strategic approaches to achieve higher levels of digital maturity. Digital government maturity is then measured by the OECD Digital Government Index (OECD, 2020[15]) against its six dimensions, which are:

1. Digital by design: establishing clear leadership, paired with effective co-ordination and enforcement mechanisms so that “digital” is not only a technical topic, but a transformational element for rethinking and re-engineering public processes, simplifying procedures, and creating new channels of communication and engagement with public stakeholders.

2. Data-driven public sector: recognising data as a strategic asset and establishing the governance to generate public value through planning, delivering and monitoring public policies and services while adopting rules and ethical principles for trustworthy and safe access, sharing and re-use.

3. Government as a platform: an ecosystem of guidelines, tools, data, standards and common components that equip teams to focus on user needs in public service design and delivery.

4. Open by default: making government data and policy-making (including algorithms) available for the public, within the limits of legislation and in balance with the national and public interest.

5. User-driven: awarding a central role to people’ needs and convenience in the shaping of processes, services and policies; and by adopting inclusive mechanisms for this to happen.

6. Proactiveness: the ability to anticipate people’s needs and respond rapidly, so that users do not have to engage with cumbersome processes associated with service delivery and data.

Figure 1.7. The OECD Digital Government Index 2019 Composite Results

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index. Information on data for Israel is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2020[14]), The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six Dimensions of a Digital Government, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en; OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en

Slovenia’s best results are attained by making government data and policy-making processes accessible to the public, within the limits of existing legislation (Open by Default dimension), and by according a central role to people’s needs in shaping processes, services and policies (User-Driven dimension). Slovenia’s average performance in the Index, with results particularly low in the Data-Driven Public Sector and Proactiveness dimensions (respectively 19th and 23rd out of 29 OECD countries) suggests the country can further improve the use of data as a strategic asset to inform decision-making and service delivery processes (Table 1.2). This might equip Slovenia with important foundations to anticipate people’s needs and respond to them proactively.

Table 1.2. Digital Government Index – Snapshot of results from Slovenia

|

Digital by Design |

Data-Driven Public Sector |

Government as a Platform |

Open by Default |

User-driven |

Proactiveness |

Composite Score |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DGI Score |

0.54 |

0.36 |

0.64 |

0.72 |

0.56 |

0.25 |

0.51 |

|

Ranking position among OECD countries |

15 |

19 |

11 |

7 |

8 |

23 |

15 |

|

Ranking position among EU countries |

8 |

11 |

3 |

5 |

2 |

13 |

7 |

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index (DGI) are Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 EU countries participated in the Digital Government Index.

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

Overall, the socio-economic and technological context in Slovenia is generally very positive. The human development and population well-being levels in the country provide strong pillars for a robust, resilient and sustainable digital transformation of the economy, society and government. Despite the cultural weaknesses identified in innovation, there are generally good conditions to enhance the benefits of the digital transformation in the public sector, to reinforce the country’s path for improved social well-being and sustainable economic development.

Macro-structure and leading public sector organisation

The clarity, stability and simplicity of the institutional model that supports priorities of digital government are foundational elements for good policy leadership, co‑ordination and implementation. Established roles and duties agreed and recognised across the administration are critical for consistent, coherent and sustainable digital change. The existence of a public sector organisation responsible for guiding and co‑ordinating digital government policies is a central element of governance analysis. Considering the different contextual factors, namely the country’s institutional culture and legacy, this public sector organisation needs to be properly located in the government structure, benefit from a clear political mandate and be equipped with the human and financial resources that can enable it to be a real driver of change across the different levels and sectors of government.

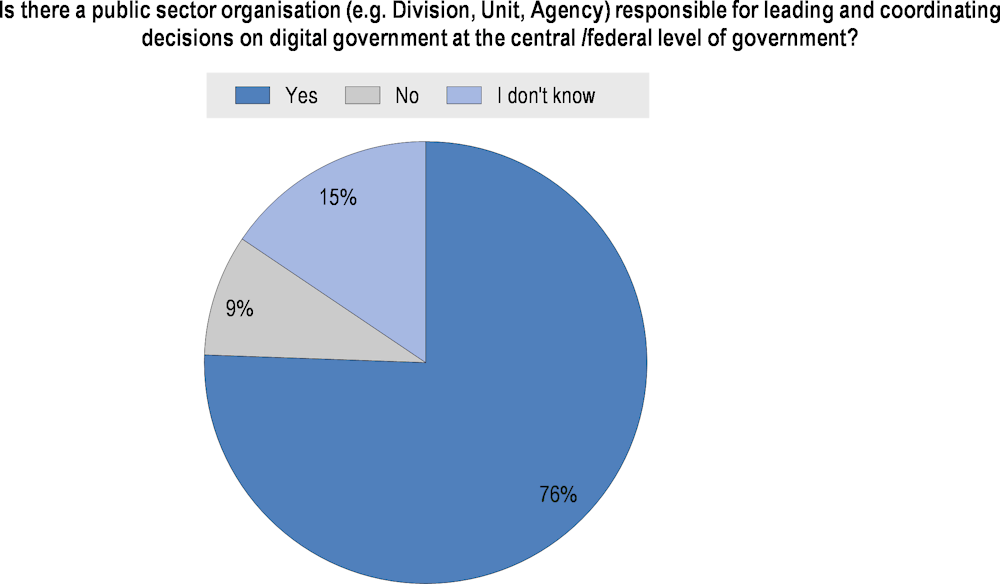

As presented in Figure 1.8, all countries that participated in the OECD Survey on Digital Government confirmed that a public sector organisation leads and co‑ordinates digital government at the central/federal level of government. However, the institutional shape of this leading public sector institution can be diverse (OECD, 2020[15]). Some countries locate this institution in the centre of government (e.g. Chile, France and the United Kingdom); others drive the digital government policy through a co‑ordinating ministry such as finance or public administration (e.g. Denmark, Italy, Portugal and Sweden) or through a line ministry (e.g. Estonia, Greece and Luxembourg). The leading public sector institution can also have different institutional shapes such as a public sector agency approach (e.g. Denmark and the United Kingdom as discussed in Box 1.2), a unit, office or directorate (e.g. Colombia and Korea) or a political level ranking authority such as a minister or secretary of state (e.g. Brazil, Estonia and Greece).

Figure 1.8. Existence of a public sector organisation leading and co-ordinating digital government in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index. Information on data for Israel is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Question 59 “Is there a public sector organisation (e.g. Division, Unit, Agency) responsible for leading and coordinating decisions on digital government at the central /federal level of government?”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

Box 1.2. Digital Government Leadership – Examples from Denmark and the United Kingdom

Agency for Digitisation – Denmark

Within the Ministry of Finance, the Agency for Digitisation was established in 2011 to lead the Danish government digitisation policies. With the aim of renewing the Danish welfare, the agency is responsible for the implementation of the government's digital ambitions and policies in the public sector.

The agency leads numerous emblematic digital government projects such as the Digital Post, the digital driver’s license, the digital Health Insurance Card, the Danish digital identity and the national citizen portal borger.dk. Due to its clear leading and co‑ordination role, the Agency is commonly recognised by senior digital government officials from other countries as one of the critical reasons for the high maturity of the digital government policy in Denmark.

Government Digital Service – United Kingdom

The Government Digital Service (GDS) was founded in December 2011. It is part of the Cabinet Office, the United Kingdom’s centre of government, and works across the whole of the government to help departments meet user needs and transform end-to-end services. GDS’ responsibilities are to:

1. maintain and develop government information and services on GOV.UK

2. work towards providing personalised, seamless and intuitive online services and information for users through GOV.UK accounts and towards a digital identity solution

3. build and support common platforms, services, components and tools

4. provide digital, data and technology experts to support government transformation.

GDS builds and maintains several cross-government platforms and tools, including GOV.UK, GOV.UK Verify, GOV.UK Pay, GOV.UK Notify and the Digital Marketplace. It also administers a number of standards, including the Government Service Standard, the Technology Code of Practice and Cabinet Office spend controls for digital and technology.

Source: Danish Ministry of Finance (2021), Agency for Digitisation website, https://en.digst.dk/about-us; UK Government (2021), Government Digital Service website, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-digital-service/about.

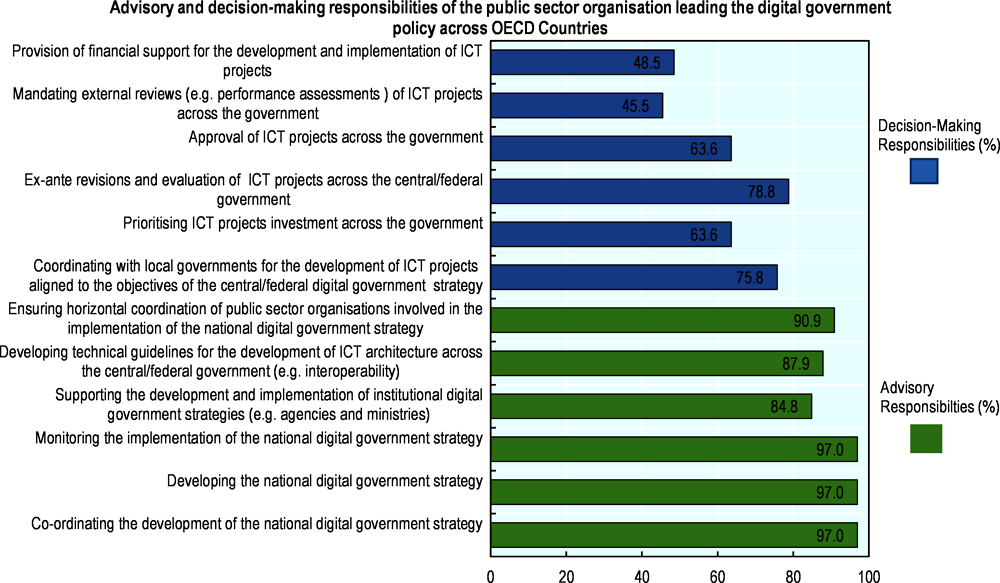

The majority of countries that participated in the OECD Survey on Digital Government 1.0 declared that their leading institutions had advisory responsibilities that include developing and monitoring the national digital government strategy (97%), ensuring horizontal co‑ordination of public sector organisations responsible for the implementation of the strategy (91%) and developing technical guidelines for interoperability across the central/federal government (88%) (see Figure 1.9). These advisory responsibilities are soft policy levers that entitle the leading public sector organisation to make recommendations but not to take action to enforce them. These responsibilities can be effective and sufficient in more horizontal, decentralised and consensus-based administrative cultures. By contrast, decision-making responsibilities, understood as hard policy levers that can better enforce the implementation of the digital government policy, are typically observed in more centralised and hierarchical administrative cultures. Among the countries that answered the OECD Survey on Digital Government 1.0, 79% of public sector organisations leading the digital government policy are responsible for ex-ante revision and evaluation of ICT projects across the administration and 64% for approval of ICT projects and prioritising ICT investments across the government. Nevertheless, less than half of the countries that answered the survey declared that their leading public sector organisation provides financial support (49%) and requests external reviews for ICT projects across the public sector (46%) (see Figure 1.9) (OECD, 2020[15]).

Figure 1.9. Responsibilities of the public sector organisation leading the digital government policy in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index. Information on data for Israel is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Questions 59a and 59b “What are the main advisory responsibilities of this public sector organisation”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

The role of the Ministry of Public Administration in Slovenia

The Slovenian government is composed of 14 ministries covering different areas of work. Each ministry is led by a minister and typically one or more secretaries of state. The Ministry of Public Administration (MPA) is responsible for leading the digital government policy, securing cross-sector and cross-level co‑ordination in the country’s public sector in this policy field. The mandate of the MPA is naturally much broader, covering areas related to public sector organisation and functioning, public sector employee system, wages, and cross-cutting administrative management. Improving the quality of public administration in collaboration with other line ministries is one of its main functions (Republic of Slovenia, 2021[33]).

With a minister and two secretaries of state, the MPA functions as a co‑ordinating ministry since its cross-cutting mandate on public administration affairs provides a government status that can be considered beyond the mandate of other line ministries. Its different responsibilities include, among others, ensuring transparency and integrity in the public sector, reducing administrative burdens, managing public procurement, as well as co‑ordinating local governments. The creation and provision of support for the development of digital services are also underlined by its mission statement.

Within the ministry, the Directorate of Informatics is responsible for the broad policy co‑ordination and implementation of public sector digitalisation. The directorate is led by a director general that responds to one of the two secretaries of state of the MPA. The Directorate of Informatics leads some of the most emblematic and structural digital government projects and initiatives in the country, such as the interoperability policies and guidelines, digital identity, emblematic digital services and applications, cloud frameworks, data management policy in the public sector, digital talent and skills, and digital security (see Chapters 3, 4 and 5).

During the OECD fact-finding mission to Ljubljana in October 2019 and during several virtual workshops and events in 2020 and 2021 with different stakeholders related with the current OECD review, the leadership of the MPA and the role of its Directorate of Informatics regarding the national digital government policy was consensually recognised across the different stakeholders involved. This consensus was also observed in the OECD Digital Government Survey of Slovenia, where 78% of public sector institutions recognised this leadership role of the ministry; only 15% did not recognise the existence of a public sector institution leading digital government in the country (Figure 1.10) (OECD, 2020[34]).

Figure 1.10. Recognition of a public sector organisation leading digital government in Slovenia

Note: Based on the responses of 45 institutions.

Source: OECD (2020[35]), Digital Government Survey of Slovenia, Public Sector Organisations Version, Question 4a “Is there a public sector organisation (e.g. Division, Unit, Agency) responsible for leading and coordinating decisions on digital government at the central /federal level of government?”.

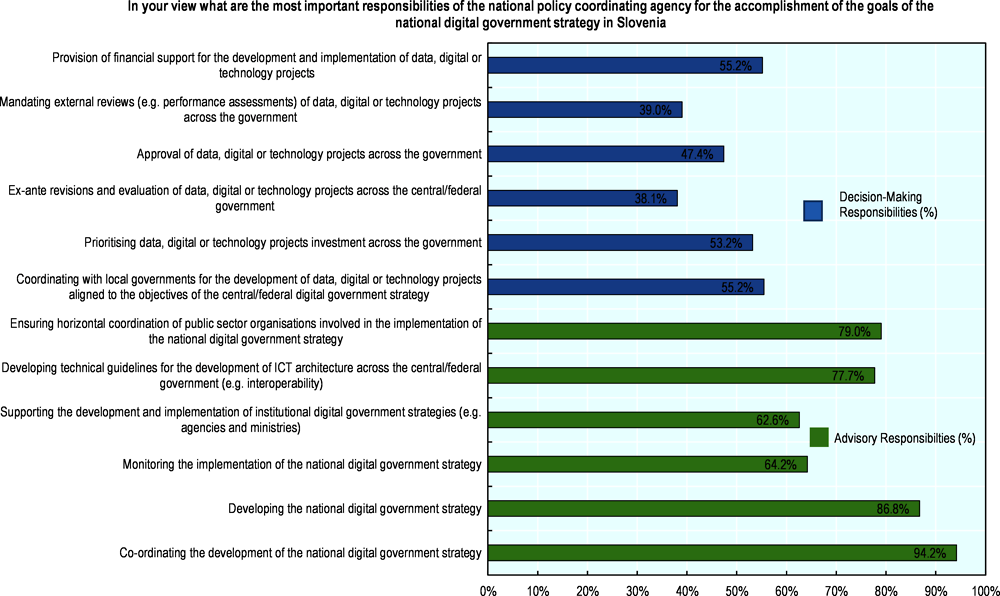

Figure 1.11 provides an insightful panorama on how Slovenian public sector institutions understand the leading role of the MPA and its Directorate of Informatics. The highest scores are observed in advisory responsibilities such as the co‑ordination of the national digital government strategy (94%), ensuring horizontal co‑ordination across public sector organisations (79%) and developing technical guidelines (78%). Decision-making responsibilities such as the provision of financial support (55%), prioritising data, digital and technology investments (53%) and approval of these projects across the public sector (47%) have substantially lower scores.

Figure 1.11. Responsibilities of the public sector organisation leading the digital government policy in Slovenia

Note: Based on the responses of 45 institutions.

Source: OECD (2020[35]), Digital Government Survey of Slovenia, Public Sector Organisations Version, Question 4c “In your view what are the most important responsibilities of the national policy coordinating agency for the accomplishment of the goals of the national digital government strategy in Slovenia?”.

In discussions with the various stakeholders during the fact-finding mission, a broad consensus was found on the importance of reinforcing the mandate and policy levers that can enable the MPA and its Directorate of Informatics to better govern the digital government policy in Slovenia (see Chapter 2). Reinforcing the decision-making responsibilities would enable empowered co‑ordination across the different sectors and levels of government that would sustain more coherent and sustainable policy approaches. Consistent and high-level political support is also necessary to co‑ordinate efforts across different line ministries and make the digital government ecosystem more resilient to changes in political cycles. More than a policy area that belongs to MPA or to its minister and/or secretary of state, the digital transformation of the public sector policy needs to be understood as a shared and jointly co‑owned imperative among its different stakeholders.

Reinforced institutional empowerment, political support and high-level visibility of the role of Director General of Informatics could also contribute to underlining the strategic importance of an advanced and mature digital government policy in Slovenia. The director general should be considered the champion and leader of the digital transformation of the public sector. Selecting the right profile for this position, can help ensure that beyond their IT background, the Director General of Informatics is seen and acknowledged as a visionary leader that is critical to consult and follow in all strategic policy decisions where digital transformation is a relevant variable.

In order to improve citizens’ well-being and sustain economic development and sustainability, the Government of Slovenia should reinforce its vision as well as its analytical and systems thinking about the role of digital technologies and data. Strengthening the mandate and increasing the policy levers of the MPA’s Directorate of Informatics would improve leadership’s ability to embrace and enhance the digital disruptiveness underway.

In the summer of 2021, a new Government Office for Digital Transformation was established, accompanied by a new dedicated Minister for Digital Transformation. This new organisation is hoped to be an important ally for the MPA is delivering on the promise of digital transformation within the public sector. At the time of writing the allocation of work, responsibilities and resources between the MPA and the new Government Office were still being established but as Slovenia moves forward with its digital transformation agenda the relationship between these two organisations will be essential in ensuring continuity and clarity for the overall direction of digital transformation as well as initiatives such as digital identity, interoperability and service design and delivery.

Co‑ordination and compliance

A co‑operative and collaborative culture across the public sector is fundamental to securing appropriate policy co‑ordination mechanisms for coherent policy design, development, delivery and monitoring. Institutional co‑ordination helps to avoid siloed policy action, to prevent policy gaps and mismatches, to encourage the interchange of opinions, mobility of skills and sharing practices, and to enable synergies between public sector stakeholders. Sound institutional co‑ordination also supports a shift from agency-thinking and government-centred methods to systems-thinking approaches in policy making and implementation capable of being synchronised with the expectations and needs of citizens and businesses (OECD, forthcoming[24]).

In line with the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[32]) and the diverse experiences and practices of OECD member and several non-member countries, successful co‑ordination approaches typically rely on two stages of co‑operation: a high-level co‑operation and management, putting together ministers or secretaries of state, and ensuring extensive collaboration and supervision of the digital government strategy. Alongside this high-level co‑operation, an organisational and technical co‑operation system is also needed to address execution difficulties and bottlenecks (OECD, 2016[36]).

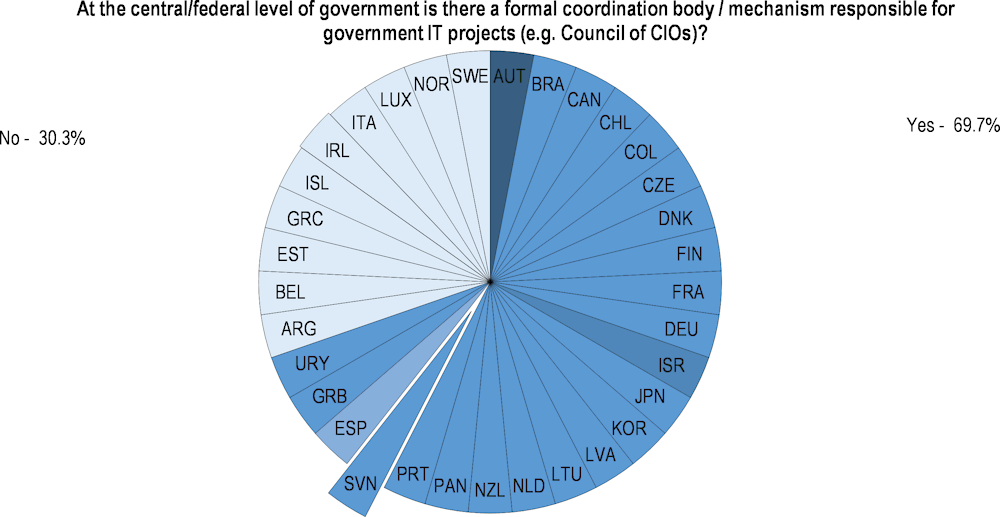

When questioned through the OECD Digital Government Survey, almost 70% of countries confirmed having a formal co‑ordinating body/mechanism responsible for government IT projects (e.g. Council of CIOs). Although other mechanisms of co‑ordination are certainly effective, it is nonetheless important to flag that 30% of countries that answered the survey do not have this kind of institutional mechanism in place (Figure 1.12) (OECD, 2020[15]). Considering that the lack of institutional co‑ordination is one of the most highlighted challenges of digital government policies at national level, such a percentage can be considered a number beyond reasonable expectations.

Figure 1.12. Existence of a co‑ordination body of digital government in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index. Information on data for Israel is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Question 60. “At the central/federal level of government is there a formal coordination body / mechanism responsible for government IT projects (e.g. Council of CIOs)?”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

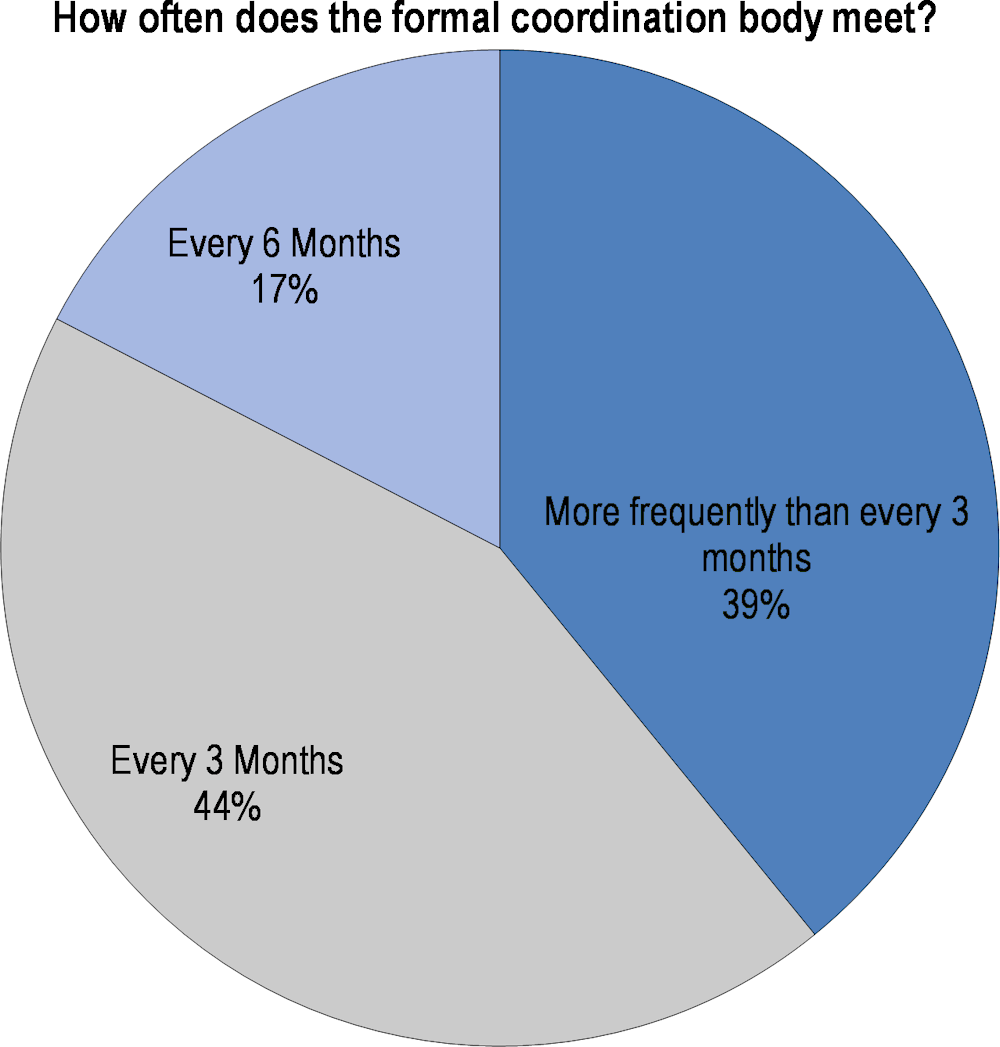

On the positive side, the regularity of meetings of the co‑ordination bodies is generally high. Thirty-nine percent of the countries that declared the existence of such a body in their national context confirmed that the meetings take place more frequently than every three months, and 44% confirmed meetings every three months (Figure 1.13). Considering the importance, intensity and fast evolution of most policy topics related to the digital transformation underway, a high level of regularity of a co‑ordination body’s meetings demonstrates the effort and commitment of central government stakeholders towards the digitalisation of its public sector.

Figure 1.13. Meeting regularity of the co‑ordination body in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index. Information on data for Israel is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Question 60a. “How often does this body and/or mechanism meet”,http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

In Slovenia, the Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration, led by the MPA and composed of secretaries of state of of the most relevant ministeries and other public institutions, is the government highest decision-making authority responsible for the digital government policy (OECD, 2019[6]). The Council has a threefold structure that, with different levels of mandates and political seniority of the stakeholders involved, allows an important distribution of co‑ordination responsibilities across the different sectors of government (Table 1.3). Provided that the distinction of roles is clear, the existence of co‑ordination at minister, secretary of state and director general levels is also an important mechanism to maintain the involvement, ownership and responsibility of different stakeholders and improve policy coherence and sustainability.

Table 1.3. Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration

|

Strategic Council |

Led by the Minister of Public Administration, the council is responsible for co‑ordination and control of deployment of digital technologies in the public sector, review and approval of the strategic orientations, confirmation of action plans and other operational documents, and validation of projects of line ministries above a certain threshold. |

|

Coordination Working Group |

Led by the Secretary of State of the Ministry of Public Administration, this group is responsible for the preparation of proposals and action plans and for the co‑ordination as well as compliance of digital government measures in line ministries and other public sector organisations. |

|

Operational Working Group |

Led by the director of the Directorate of Informatics, the Operational Working Group is responsible for the implementation of activities, the preparation and implementation of operational documents, and work reports based on action plans. It provides its consent to line ministries and government services for all projects and activities that result in the acquisition, maintenance, or development of IT equipment and solutions. |

Source: OECD (2020[15]), Digital Government Index: 2019 results, Answer from Slovenia

The Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration is a central mechanism in the country to steer the digital government policy, maintaining the involvement and commitment of the different stakeholders involved. In line with the responsibilities presented in Table 1.3, the Council is responsible, for instance, for the review and approval of digital projects in the public sector above the threshold of EUR 20 000 (see Chapter 2. This mechanism of pre-approval is an important policy lever to secure a coherent implementation of the digital government policy across the different sectors and levels of government).

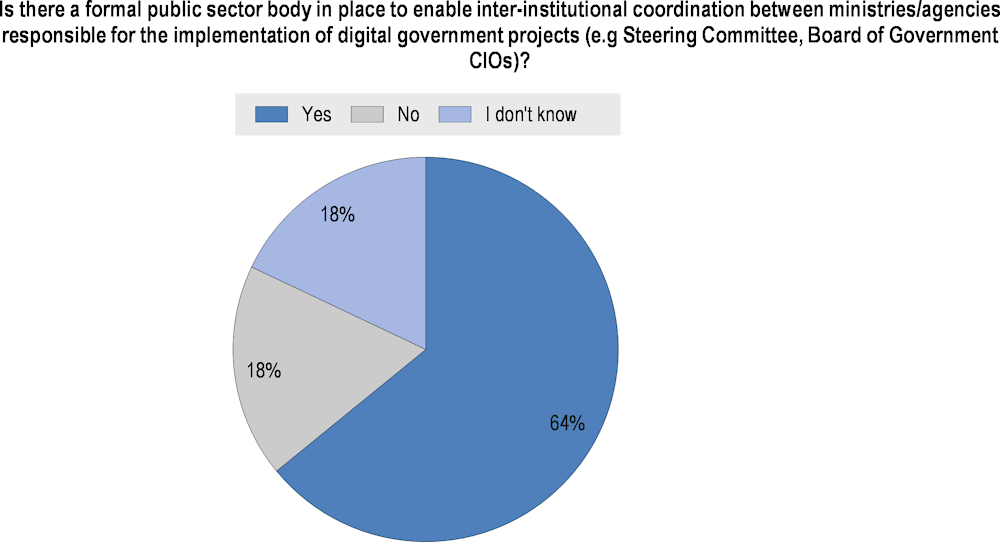

The level of acknowledgement of the existence of the Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration among the Slovenian public sector stakeholders is substantively high. Sixty-four percent of Slovenian public sector institutions that participated in the OECD Digital Government Survey of Slovenia reported the existence of the Council (Figure 1.14) (OECD, 2020[34]). During the fact-finding mission in Ljubljana in October 2019, the stakeholders interviewed by the OECD team constantly mentioned the Council as the central mechanism of policy co‑ordination among different sectors of government. For improved collaboration, shared goals and the definition of priorities, as well as the adoption of joint processes and guidelines, the Council was frequently referred to as a critical consensus-building instrument to overcome siloed approaches and reinforce systems thinking in the Slovenian public sector.

Figure 1.14. Existence of public sector body to enable digital government co‑ordination in Slovenia

Note: Based on the responses of 45 institutions.

Source: OECD (2020[35]), Digital Government Survey of Slovenia, Public Sector Organisations Version, Question 6 “Is there a formal public sector body in place to enable inter-institutional coordination between ministries/agencies responsible for the implementation of digital government projects (e.g Steering Committee, Board of Government CIOs)?”.

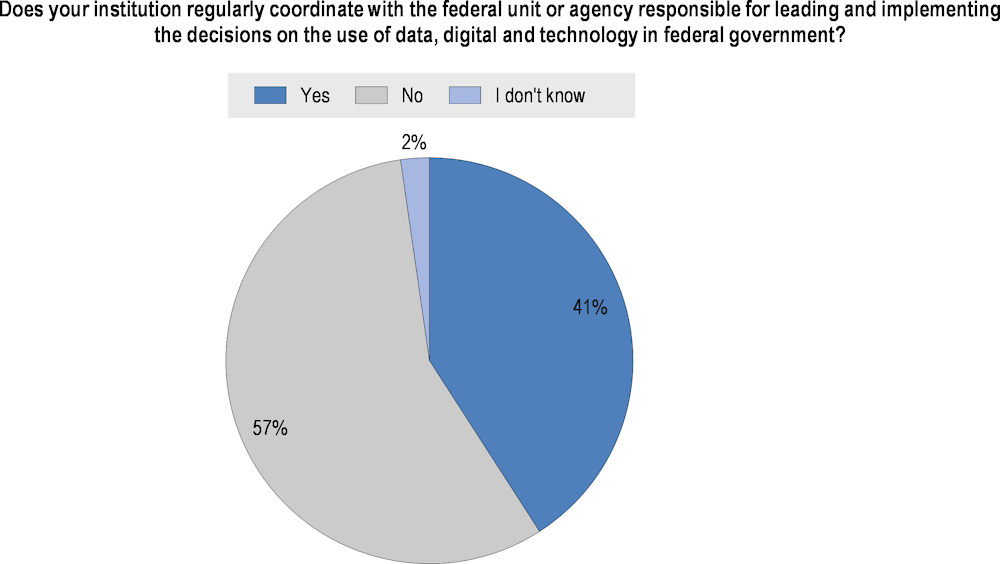

Despite the interesting structure and the high level of acknowledgement among the Slovenian ecosystem of digital government stakeholders, the absence of Strategic Council meetings from April 2018 until the writing of the current report is the biggest limitation identified in the Slovenian governance of digital government. In the OECD survey, lack of horizontal co‑ordination was the most commonly raised challenge by Slovenian public sector institutions for improved consistency in the digitalisation of the public sector. When questioned about policy co‑ordination with the unit or agency responsible for leading the digital government policy, the majority of Slovenian public sector institutions that answered the survey declared not organising meetings regularly (Figure 1.15) (OECD, 2020[34]). This lack of regular coordination meetings for the definition of common goals, synchronised policy implementation and even improved knowledge sharing challenges the consistency of the policy efforts underway to digitise the country’s public sector.

Figure 1.15. Co‑ordination regularity with the public sector organisation leading digital government in Slovenia

Note: Based on the responses of 45 institutions.

Source: OECD (2020[35]), Digital Government Survey of Slovenia, Public Sector Organisations Version, Question 5 “Does your institution regularly coordinate with the federal unit or agency responsible for leading and implementing the decisions on the use of data, digital and technology in federal government?”

Securing the functioning of the existing horizontal co‑ordination mechanisms would reinforce the coherent implementation of the digital government policy. During the drafting of this report, the Government of Slovenia launched a new council, the Strategic Council for Digitalisation in the Office of the Prime Minister, mobilising public, private and civil society stakeholders. This council has the immediate and specific purpose of discussing and preparing proposals that can boost the country’s performance in the current digital transformation context. In this sense, six working groups were set up to focus on the following topics: 1) public administration and the digital society, 2) health, 3) digitalisation of education, 4) economy and the business environment, 5) new technologies, and 6) digital diplomacy. This initiative reflects the Slovenian government’s efforts and commitment to embrace an open, inclusive and collaborative process in the development of digital transformation policies.

During the drafting of the current report, the OECD team was also informed that the reactivation of the Governmental Council of Informatics Development in Public Administration was being discussed and is foreseen for the upcoming months. This reactivation can be an opportunity to rethink its design and functioning. For instance, instead of the current threefold structure, the Slovenian government could consider a twofold approach based on a high-level policy definition body bringing together ministers and/or secretaries of state and a technical co‑operation body constituted at director general level more focused on implementation-oriented topics. Such a twofold approach could bring additional agility and simplicity for digital government co‑ordination in Slovenia. Reinforcing the collaboration of the Council with civil society stakeholders, through open meetings, frequent consultation and joint policy development, should also be considered to improve the alignment of the digital government policy with the expectations and needs of the civil society ecosystem of stakeholders.

Notes

← 1. Analysis based on the OECD How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being publication (OECD, 2020[2]).

← 2. The Going Digital Toolkit (OECD, 2020[4]) helps countries navigate the digital transformation affecting many aspects of the economy and society in complex and interrelated ways. This OECD policy instrument is based on a framework of seven policy dimensions: 1) access to communications infrastructures, services and data, 2) effective use of digital technologies and data, 3) data-driven and digital innovation, 4) good jobs for all, 5) social prosperity and inclusion, 6) trust in the digital age, and 7) market openness in digital business environments. The Toolkit maps a core set of indicators to each of the seven policy dimensions. More information is available at https://goingdigital.oecd.org.