Participation rates in adult learning (formal and/or non-formal education and training) for women increased in almost all OECD countries with data from the Adult Education Survey (AES) in 2007 and 2016, and on average from 38% in 2007 to 48% in 2016. For men, the average increased from 37% in 2007 to 47% in 2016.

On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, 55% of 25-64 year-olds that are employed participated in formal and/or non-formal education and training, compared to only 27% of those that are unemployed. In addition, data show that employed women were more likely to participate in training compared with employed men.

On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, 40% of women cited family responsibilities as a barrier to enrolment, compared to 25% of men.

Education at a Glance 2021

Indicator A7. To what extent do adults participate equally in education and learning?

Highlights

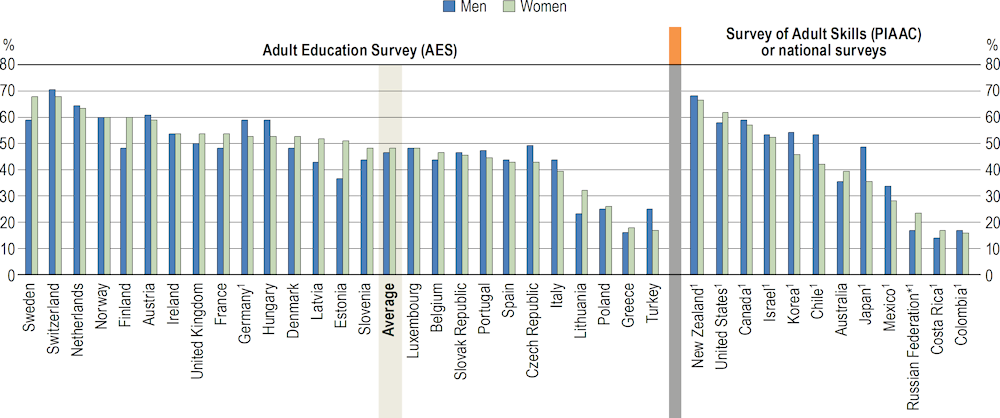

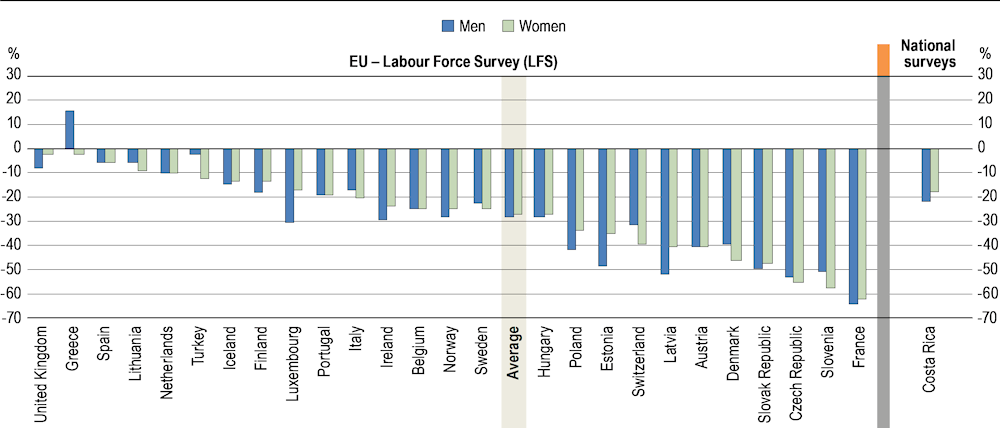

Figure A7.1. Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender (2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) or national surveys, 25-64 year-olds

1. Year of reference differs from 2016. Refer to the source table for more details.

* See note on data for the Russian Federation in the Source section.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the percentage of 25-64 year-old women participating in formal and non-formal education and training in 2016.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A7.1. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Context

Policy makers have long recognised that adult learning is crucial for workers, firms and entire economies seeking to prevent human capital depreciation and to remain competitive in a globalised and ever-changing work environment.

There is ample evidence that the provision of adult learning allows adults, whether employed or looking for a job, to maintain and upgrade their skills, acquire the competencies needed to be successful in the labour market and strengthen their overall resistance to exogenous shocks such as the current COVID-19 pandemic (OECD, 2021[1]).

The benefits of adult learning extend beyond employment and other labour market outcomes. In fact, adult learning can also contribute to non-economic goals, such as personal fulfilment, improved health, civic participation and social inclusion (Ruhose, Thomsen and Weilage, 2019[2]).

However, across OECD countries, it is common that those who need training the most, train the least. These groups include lower skilled, older adults, displaced workers, those whose jobs are most at risk of automation, and non‑standard workers as, for example, part-time and on-call workers. To give a few examples, participation by low-skilled adults is a staggering 40 percentage points below that of high-skilled adults, across the OECD on average. Older adults are 25 percentage points less likely to train than 25-34 year-olds. Workers whose jobs are at high risk of automation are 30 percentage points less likely to engage in adult learning than their peers in less-exposed jobs (OECD, 2021[1]).

This year’s Education at a Glance looks at the association between participation in adult learning and gender as well as the role played by some mediating factors like, for example, the presence of young children in the household.

Still, it is worth noting that the analyses presented in the following sections are based on results of simple bivariate correlations and do not take into account many of the factors influencing the likelihood to participate in adult learning, such as age, firm size and sector of employment – to mention just a few important ones.

Other findings

Participation in non-formal education and training by adults aged 25-64 years-old surpasses participation in formal education and in all countries with available data from the AES. On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, in 2016, 7% of 25-64 year-olds took part in formal education and training, while 44% took part in non-formal education and training.

Participation rates in non-formal education do not differ much by gender (45% for women and 44% for men); however, data show that men and women tend to pursue different fields of training.

Relative to the same quarter, in 2019, the number of adults reporting they participated in formal and/or non-formal education and training in the past month dropped significantly in the second quarter of 2020 in all countries with available data.

Analysis

Trends in participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender

On average across countries with data from the Adult Education Survey (AES), about half of the surveyed adults (aged 25‑64) had participated in adult learning (formal and/or non-formal education and training) in 2016. Participation rates varied widely, from 30% or less in Greece, Lithuania, Poland and Turkey to more than 60% in the Netherlands, Sweden and Switzerland (Table A7.1).

Participation in non-formal education training by adults aged 25-64 years-old and training surpasses participation in formal education and training in all countries with available data from the AES. On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, in 2016, 7% of 25-64 year-olds took part in formal education and training while the rate was 44% for non-formal education and training. Participation rates in formal education and training were 10% or more in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom; on the contrary, at least 50% of 25-64 year-olds took part in non-formal education and training in Austria, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland (Table A7.1).

Between 2007 and 2016, participation rates in adult learning (formal and/or non-formal education and training) increased in almost all countries with available data. On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, participation rates in adult learning increased from 38% in 2007 to 48% in 2016. Over this period, they increased by 20 percentage points or more in Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal and Switzerland while they decreased by at least 5 percentage points in Lithuania (Table A7.1).

Participation rates in adult learning (formal and/or non-formal education and training) for women increased in almost all countries with available data for 2007 and 2016, and on average from 38% in 2007 to 48% in 2016. For men, the average increased from 37% in 2007 to 47% in 2016. In most countries, there are no big differences in participation rates between women and men, and this holds true for 2007 and 2016. The change over time has been similar for men and women, meaning that the situation observed in 2007 has mostly been carried over time (Table A7.1).

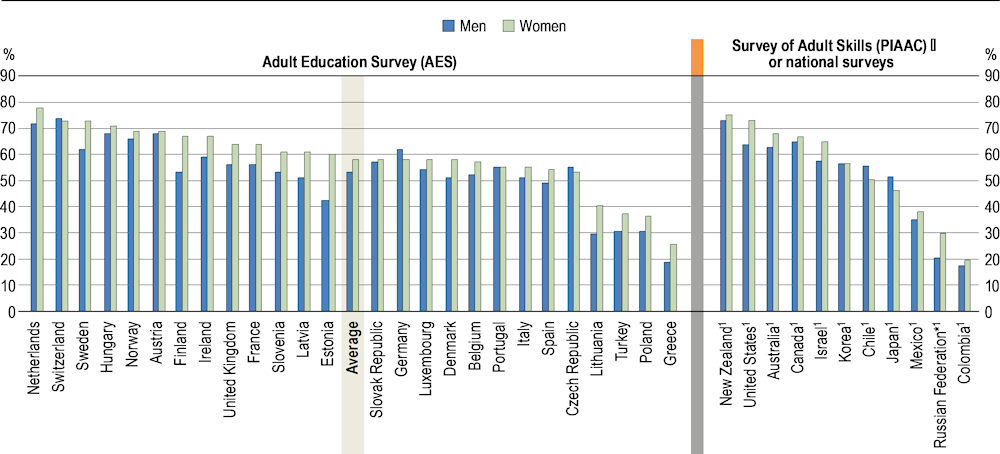

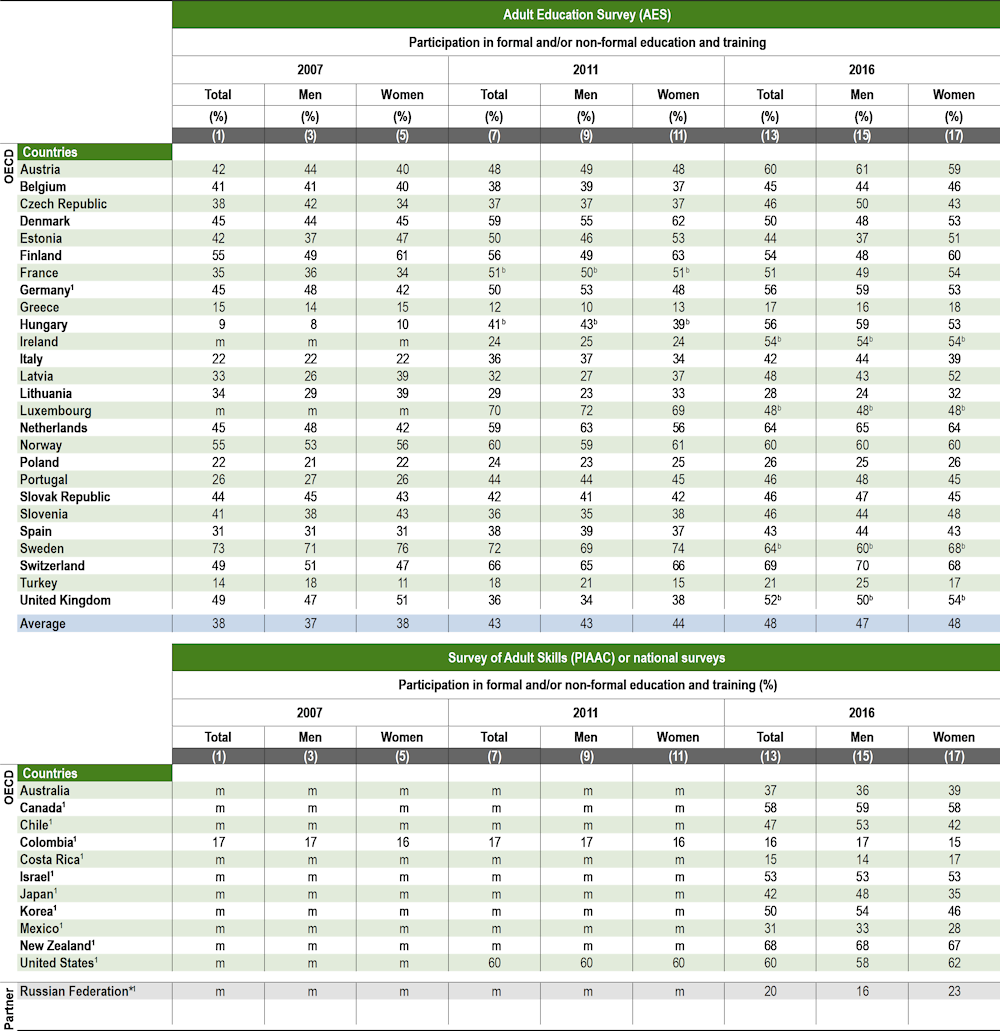

Figure A7.2. Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training for employed persons, by gender (2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) or national surveys, 25-64 year-olds

1. Year of reference differs from 2016. Refer to the source table for more details.

* See note on data for the Russian Federation in the Source section.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the percentage of 25-64 year-old employed women participating in formal and/or non-formal education and training.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A7.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

In 2016, in Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Sweden, men participated less than women in formal and/or non-formal education and training. In these countries, the gender gap in participation rates was at least 9 percentage points in favour of women (Figure A7.1).

Differences in participation rates by gender are also small when only looking at participation in formal or non-formal education and training. Differences by gender are not substantial for participation in formal education. In countries with rather high overall participation rates, women participate more in formal education than men. For the majority of other countries, women participate more, but the differences are rather small. The differences between men and women are also small for participation in non-formal education and training and there is no pattern observed in the participation rate by gender (Table A7.1).

Participation and labour market status, by gender

On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, 55% of 25-64 year-olds that are employed participated in formal and/or non-formal education and training, compared to only 27% of those that are unemployed (Table A7.2).

In addition, data show that employed women were more likely to participate in training compared with employed men. In addition, across OECD countries with available data from the AES, 25-64 year-old women tend to participate slightly more in adult learning than men of the same age (formal and/or non-formal education and training), regardless of their labour market status. In particular, among the employed, the average gender gap in participation rate is 6 percentage points in favour of women; it is 9 percentage points or more in Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden Table A7.2).

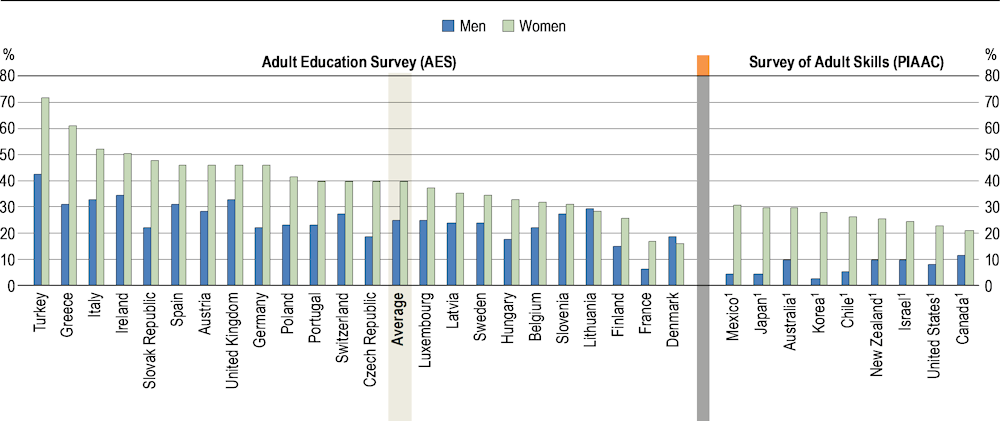

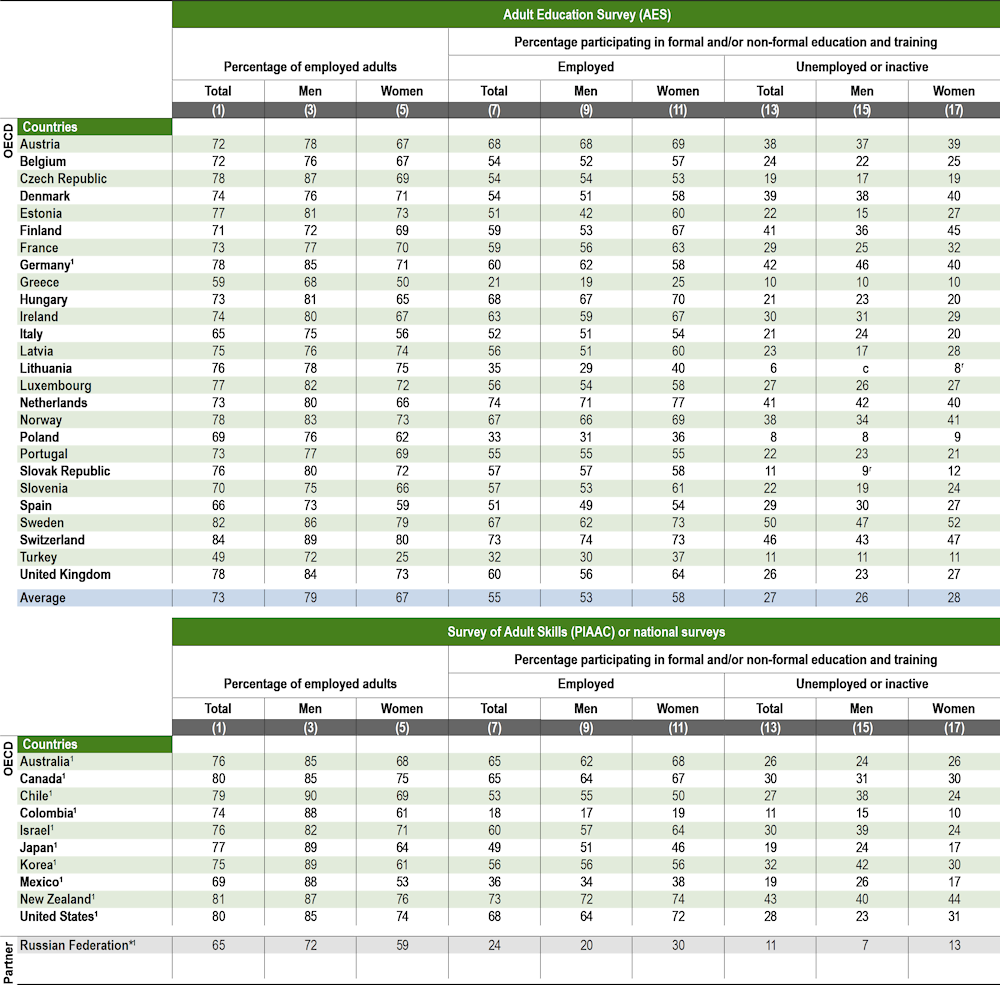

Figure A7.3. Percentage of adults reporting wanting to participate in education and training but could not because of family responsibilities, by gender (2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES) or Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 25-64 year-olds

1. Year of reference differs from 2016. Refer to the source table for more details.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the percentage of 25-64 year-old men reporting to want to participate in formal and/or non-formal education and training but could not because of family responsibilities.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A7.6, available on line. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Barriers to participation, by gender

Cost, schedule and family responsibilities are the most common reasons for not participating in formal and/or non‑formal education and training (Table A7.6, available on line).

In particular, data suggest that family responsibilities, such as caring for children or elderly in the household, are a strong barrier to participation in adult learning (in formal and/or non-formal education and training) for women than for men. On average across OECD countries taking part in the AES, 40% of women cited family responsibilities as a barrier to enrolment, compared to 25% of men. Gender differences are particularly evident in Australia, Chile, the Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the Slovak Republic and Turkey. In these countries, the share of 25-64 year-old women stating that they wanted to participate in education and training but could not because of family responsibilities is at least 20 percentage points higher than the share of men (Figure A7.3).

Having young children in the household represents important responsibilities and it is therefore interesting to see whether this status is associated with greater or less participation in adult education – because of a lack of time. Looking at participation rates by gender can also shed some light on how responsibilities are shared between men and women.

When there are no children under 13 (i.e. young children) in the household, 25-64 year-old women tend to participate slightly more than men in formal and/or non-formal education in most of the countries with available data. This is particularly evident in Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Lithuania, where the participation rates of women are more than 10 percentage points higher than those of men (Table A7.3).

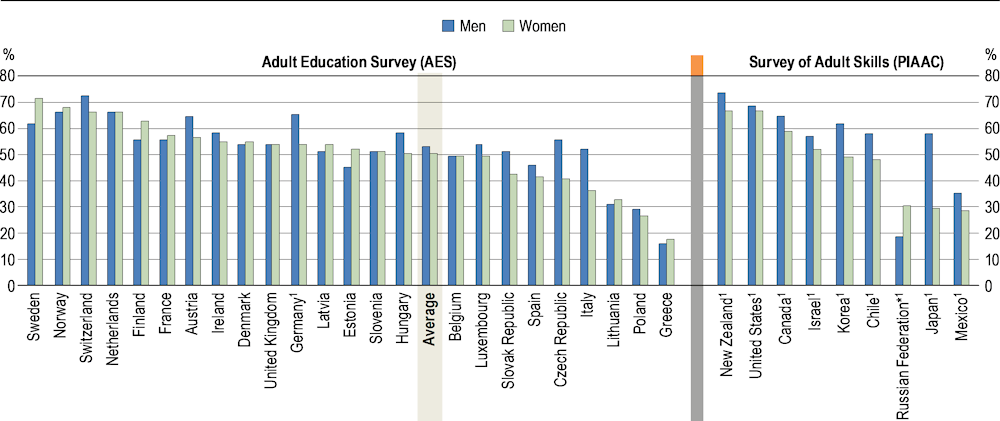

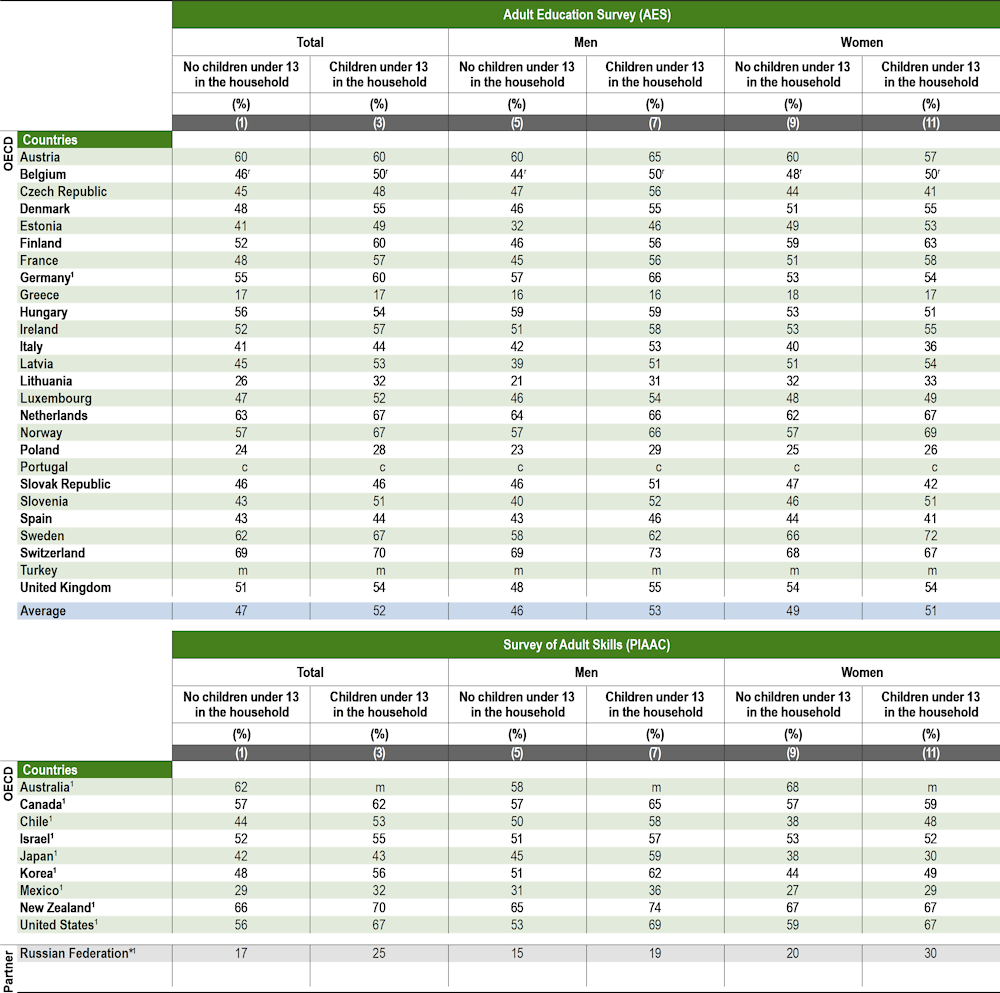

Figure A7.4. Participation in formal and/or non-formal education when there are young children in the household, by gender (2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES) or Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 25-64 year-olds

1. Year of reference differs from 2016. Refer to the source table for more details.

* See note on data for the Russian Federation in the Source section.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the percentage of 25-64 year-old women with young children in the household participating in formal and/or non-formal education and training.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A7.3. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

On the contrary, when there are young children in the household, data suggest that men participate somewhat more than women in formal and/or non-formal education. In this case, participation rates of men are more than 10 percentage points higher than those of women in the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Japan and Korea. Even when there are young children in the household, participation rates are relatively higher for women than for men (i.e. 5 percentage points or more) in Estonia, Finland, the Russian Federation and Sweden (Figure A7.4).

It is important to highlight that the results presented in Figure A7.4 do not account for several confounding factors that could influence the relationship between having young children in the household and participating in adult learning as, for example, age, family socio-economic background and grandparents’ support.

Participation before and during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic

A recent OECD brief shows that, under a certain number of assumption, COVID-19 induced shutdowns of economic activities decreased workers’ participation in non-formal learning by an average of 18%, and in informal learning by 25% (OECD, 2021[1]).

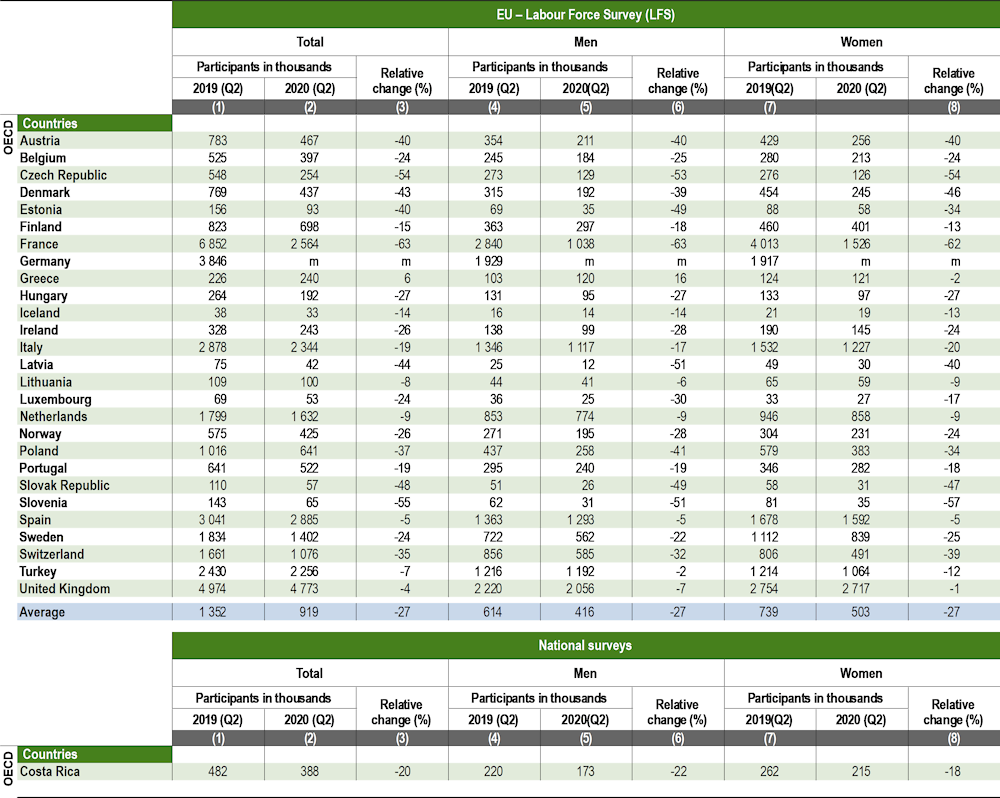

This section uses data from the EU Labour Force Survey for European countries and from the Continuous Employment Survey for Costa Rica, to examine how the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has affected participation in adult learning (formal and/or non-formal education and training).

Figure A7.5 shows that relative to the same quarter, in 2019, the number of adults reporting they participated in formal and/or non-formal education and training in the month prior to the survey decreased significantly in the second quarter of 2020. This is particularly evident in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Latvia, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Switzerland, where the number of adults participating in formal and/or non-formal education and training decreased by 30% or more between the second quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, for both women and men (i.e. during the peak of the first wave of COVID-19 in Europe). Greece seems to be an outlier, at least when considering male adults. However, it is worth highlighting that participation rates in formal and/or non-formal education and training are rather low in Greece. In this case, small variations of the participation rates over time may have large impact on the relative change over the same period (Figure A7.5).

Figure A7.5. Relative change in the participation in the previous 4 weeks in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender (second quarter of 2020 compared to second quarter of 2019)

EU Labour Force Survey (LFS) or national survey, 25-64 year-olds

Countries are ranked in ascending order of the relative change of participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training for women during the second quarter of 2020 relative to the second quarter of 2019.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A7.4. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

The results presented in Figure A7.5 have at least two important limitations. First, as observed in the European Union’s Education and Training Monitor 2018, the way participation in adult learning is measured in the EU Labour Force Survey is rather restrictive, as it measures the “share of population who report having participated in formal and/or non-formal learning activities during the 4 weeks prior to being interviewed”. This is problematic in the context of adult learning, which is a sporadic activity, often taken up once or at most twice a year for a short duration (European Commission, 2018[3]).

Second, this section reports only some preliminary analyses on the impact of COVID-19 on participation in adult learning during the first wave of the pandemic and they must be interpreted with care. Further analyses, covering a wider range of quarters, are needed. In fact, third and fourth quarter data suggest that participation rates increased again considerably in countries as, for example, Latvia and Switzerland. Most likely, the steep drop in participation observed between the second quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020 is a consequence of the widespread lockdown restrictions implemented during the first wave of the pandemic. During this period, non-formal education providers needed some time to adapt to the provision of online-only courses.

Participation by field of education and training and gender

The majority of adult education and training that takes place is non-formal education and training and is usually organised outside of formal institutions of schools, colleges and universities. On average across OECD countries with data from the AES, 44% of adults aged 25-64 took part in non-formal education and training activities in 2016 (Table A7.1). About half of them (51%) attended non-formal education programmes in the field of business, administration and law (18%); health and welfare (14%); or services (19%) (Table A7.5, available on line).

Although participation rates in non-formal education do not differ much by gender (45% for women and 44% for men), men and women tend to pursue different fields of training. Data show that, compared to women, men are more likely to follow training initiatives in the field of information and communication technologies (7% for women and 10% men); engineering, manufacturing and construction (3% and 13%, respectively); and services (15% and 23%, respectively) (Table A7.5, available on line).

On the other hand, compared to men, women are more likely to take part in non-formal and training initiatives in the field of education (4% for men and 10% for women), arts and humanities (7% and 11%, respectively), and health and welfare (9% and 19%, respectively) (Table A7.5, available on line).

Finally, men and women are equally likely to participate in non-formal education and training programmes in the field of social sciences, journalism and information (3% and 4%, respectively) and business, administration and law (18% for both men and women) (Table A7.5, available on line).

Definitions

Adults refer to 25-64 year-olds.

Adult education and learning: the learning that occurs in formal settings such as vocational training and general education as well as resulting from participation in formal, non-formal and informal training.

Formal education is planned education provided in the system of schools, colleges, universities and other formal educational institutions that normally constitutes a continuous “ladder” of full-time education for children and young people. Providers may be public or private. Non-formal education is sustained educational activity that does not correspond exactly to the definition of formal education. Non-formal education may take place both within and outside educational institutions and cater to individuals of all ages. Depending on country contexts, it may cover education programmes in adult literacy, basic education for out-of-school children, life skills, work skills and general culture.

Methodology

The Adult Education Survey (AES) methodology can be found at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Adult_Education_Survey_(AES)_methodology.

For data from the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), observations based on a numerator with fewer than 5 observations or on a denominator with fewer than 30 observations times the number of categories have been replaced by “c” in the tables.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) measures participation in formal and/or non-formal training during a four-week period excluding guided on-the-job training. The reference period and the definition differ from the definitions in the AES. In particular, differences in participation rates in formal and/or non-formal training between the LFS and the AES are due to the short reference period in the LFS compared to participation rates in the AES.

Table A7.6, available on line (Percentage of the population wanting to participate in education and training but did not, by reason for not participating), provides a mapping of the reasons for not participating in adult education, provided by respondents to the AES and PIAAC. The range of possible answers to this question are different in the two surveys. In order to allow for comparison, these answers have been recategorised in Table A7.6 as follows:

1. “Distance” in the AES corresponds to “The course or programme was offered at an inconvenient time or place” in PIAAC

2. “Costs” in the AES corresponds to “Education or training was too expensive/I could not afford it” in PIAAC

3. “Family reasons” in the AES corresponds to “I did not have time because of childcare or family responsibilities” in PIAAC

4. “Other personal reasons” is missing in PIAAC

5. “Health or age reasons” is missing in PIAAC

6. “No suitable offer for education or training” is missing in PIAAC

7. “Lack of support from employer or public services” corresponds to “Lack of employer’s support” in PIAAC

8. “Schedule” corresponds to “I was too busy at work” in PIAAC

9. “Other” corresponds to “Other”, “Something unexpected came up that prevented me from taking education or training” and “I did not have the prerequisites” in PIAAC.

Source

For Table A7.1 (Trends in participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender): The AES for European OECD countries; PIAAC for Canada, Chile, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the Russian Federation and the United States; and national data sources for Australia (Work-Related Training and Adult Learning Survey), Colombia (Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares), Costa Rica (Continuous Employment Survey).

For Table A7.2 (Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by labour market status and gender): The AES for European OECD countries; PIAAC for Australia, Canada, Chile, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the Russian Federation and the United States; and national data sources for Colombia (Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares).

For Table A7.3 (Participation in formal and/or non-formal education, by gender and whether there are young children in the household): The AES for European OECD countries and PIAAC for Australia, Canada, Chile, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the Russian Federation and the United States.

For Table A7.4 (Participants in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender): the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) for European OECD countries and national data sources for Costa Rica (Continuous Employment Survey).

For Table A7.5, available on line (Distribution of fields of study selected among non-formal education participants, by gender): The AES for European OECD countries.

For Table A7.6, available on line (Percentage of the population wanting to participate in education and training but did not, by reason for not participating): The AES for European OECD countries and PIAAC for Australia, Canada, Chile, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, the Russian Federation and the United States.

Note regarding data from the Russian Federation in the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC)

The sample for the Russian Federation does not include the population of the Moscow municipal area. The data published, therefore, do not represent the entire resident population aged 16-65 in the Russian Federation, but rather the population of the Russian Federation excluding the population residing in the Moscow municipal area. More detailed information regarding the data from the Russian Federation as well as that of other countries can be found in the Technical Report of the Survey of Adult Skills, Second Edition (OECD, 2016[4]).

References

[3] European Commission (2018), Education and Training Monitor 2018, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, http://dx.doi.org/10.2766/444804 NC-AJ-18-001-EN-E.

[1] OECD (2021), “Adult learning and COVID-19: How much informal and non-formal learning are workers missing?”, Tackling Coronavirus (COVID-19): Contributing to a Global Effort, OECD, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1069_1069729-q3oh9e4dsm&title=Adult-Learning-and-COVID-19-How-much-informal-and-non-formal-learning-are-workers-missing&_ga=2.236822465.1330067427.1621939082-554327329.1614244310 (accessed on 26 May 2021).

[4] OECD (2016), Technical Report of the Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC), 2nd Edition, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/PIAAC_Technical_Report_2nd_Edition_Full_Report.pdf.

[2] Ruhose, J., S. Thomsen and I. Weilage (2019), “The benefits of adult learning: Work-related training, social capital, and earnings”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 72, pp. 166-186, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2019.05.010.

Indicator A7 tables

Tables Indicator A7. To what extent do adults participate equally in education and learning?

|

Table A7.1 |

Trends in participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender (2007, 2011 and 2016) |

|

Table A7.2 |

Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by labour market status and gender (2016) |

|

Table A7.3 |

Participation in formal and/or non-formal education, by gender and whether there are young children in the household (2016) |

|

Table A7.4 |

Participants in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender (second quarter of 2020 compared to second quarter of 2019) |

|

WEB Table A7.5 |

Distribution of fields of study selected among non-formal education participants, by gender (2016) |

|

WEB Table A7.6 |

Percentage of the population wanting to participate in education and training but did not, by reason for not participating (2016) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2021. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table A7.1. Trends in participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender (2007, 2011 and 2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) or national surveys, 25-64 year-olds

Note: Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training during previous 12 months. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Note that the average differs from the one published by Eurostat as this is an unweighted average and the country coverage is different.

Additional columns showing standard errors (S.E.) as well as data by type of education and training are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below).

1. 2007 refers to 2013 for Colombia; 2011 refers to 2015 for Colombia and 2012/2014 for the United States; 2016 refers to 2020 for Costa Rica, 2019 for Colombia, 2017 for Mexico and the United States, 2015 for Chile, Israel and New Zealand, 2012 for Canada, Japan, Korea and the Russian Federation.

* See note on data for the Russian Federation in the Source section.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table A7.2. Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by labour market status and gender (2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) or national surveys, 25-64 year-olds

Note: Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training during the previous 12 months. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Note that the average differs from the one published by Eurostat as this is an unweighted average and the country coverage is different.

Additional columns showing standard errors (S.E.) are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below).

1. Reference year differs from 2016: 2018 for Germany; 2017 for Colombia, Mexico and the United States; 2015 for Canada, Chile, Israel, Korea and New Zealand; 2012 for Australia, Japan and the Russian Federation.

* See note on data for the Russian Federation in the Source section.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table A7.3. Participation in formal and/or non-formal education, by gender and whether there are young children in the household (2016)

Adult Education Survey (AES), Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) or national surveys, 25-64 year-olds

Note: Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training during the previous 12 months. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Note that the average differs from the one published by Eurostat as this is an unweighted average and the country coverage is different.

Additional columns showing standard errors (S.E.) are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below).

1. Reference year differs from 2016: 2018 for Germany; 2017 for Mexico and the United States; 2015 for Canada, Chile, Israel, Korea and New Zealand; 2012 for Australia, Japan and the Russian Federation

* See note on data for the Russian Federation in the Source section.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table A7.4. Participants in formal and/or non-formal education and training, by gender (second quarter of 2020 compared to second quarter of 2019)

EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) or national surveys, 25-64 year-olds

Note: Participation in formal and/or non-formal education and training in the last 4 weeks. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Note that the average differs from the one published by Eurostat as this is an unweighted average and the country coverage is different.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.