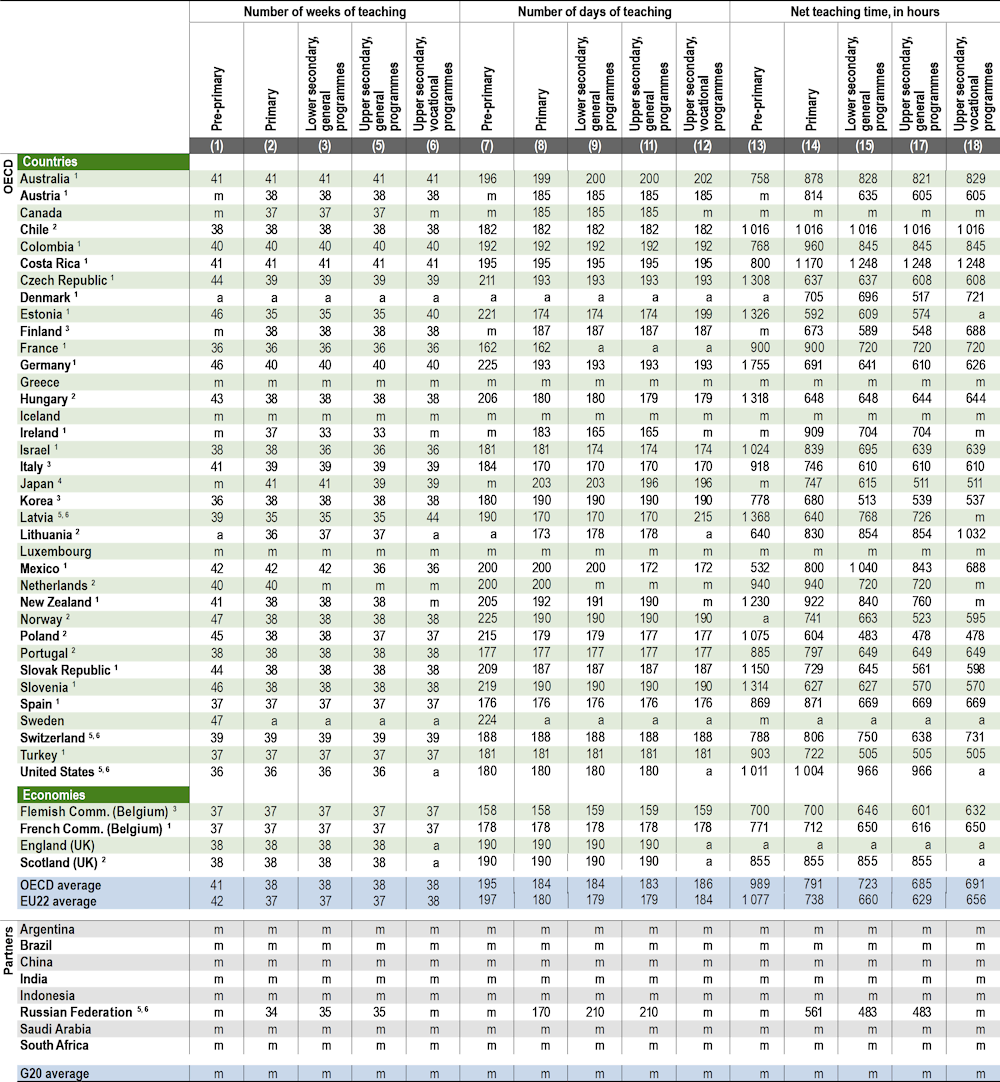

According to official regulations or agreements, teachers in public schools in OECD countries and economies are required to teach on average 989 hours per year at pre-primary level, 791 hours at primary level, 723 hours at lower secondary level (general programmes) and 685 hours at upper secondary level (general programmes).

The way teachers’ total working time is divided between teaching and non-teaching activities, and the distribution of working hours taking place within the school or elsewhere, varies greatly across countries.

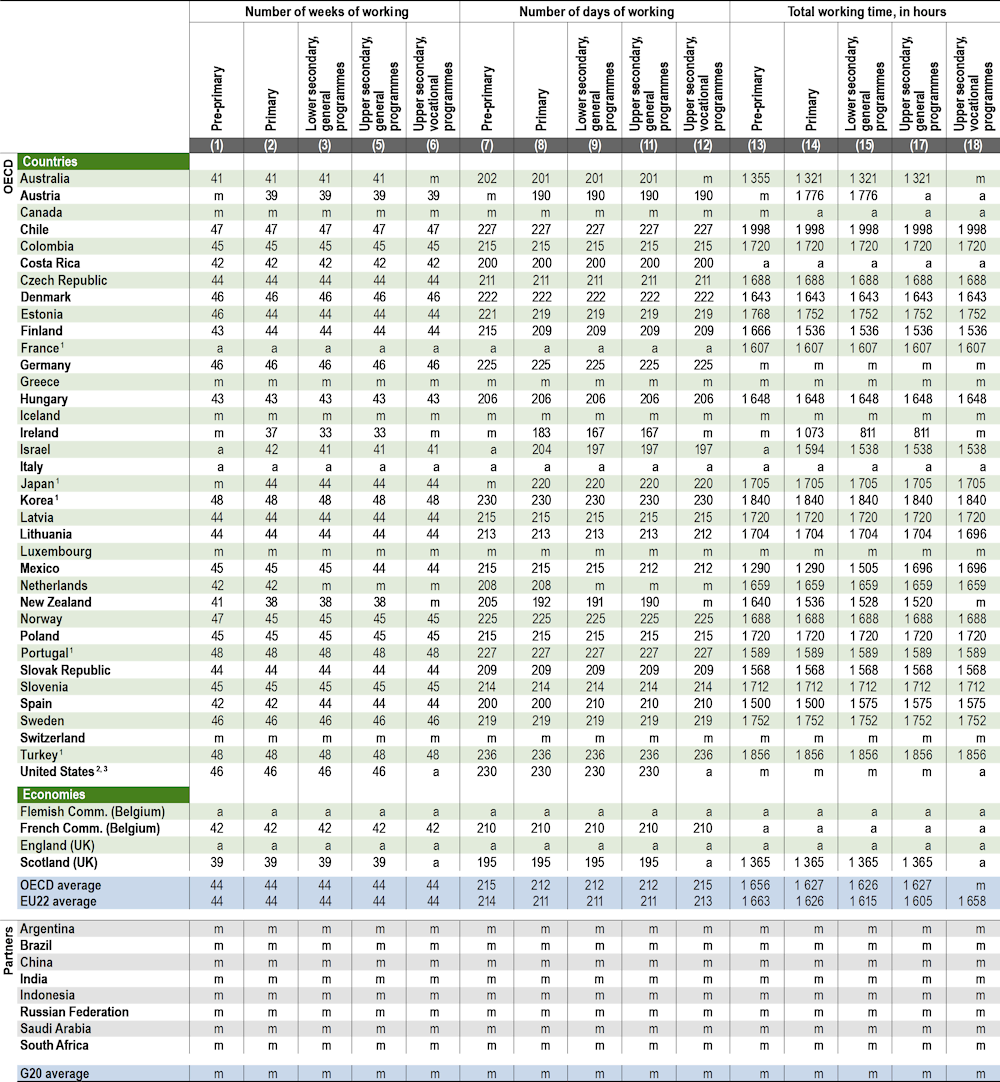

School heads in OECD countries and economies work an average of 44 weeks per year at pre-primary, primary and secondary levels of education. Their annual statutory working time averages to 1 656 hours at pre-primary level, 1 627 hours at primary level, 1 626 hours at lower secondary level and 1 627 hours at upper secondary level. In about two-thirds of OECD countries, school heads are required to work during students’ school holidays.

Education at a Glance 2021

Indicator D4. How much time do teachers and school heads spend teaching and working?

Highlights

1. Actual teaching time (in Latvia except for pre-primary level).

2. Reference year differs from 2020. Refer to the source table for details.

3. Average planned teaching time in each school at the beginning of the school year.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the number of teaching hours per year in general upper secondary education.

Source: OECD (2021), Table D4.1. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Context

Although statutory working and teaching hours only partly determine the actual workload of teachers and school heads, they do offer valuable insights into the demands placed on teachers and school heads in different countries. Teaching hours and the extent of non-teaching duties may also affect the attractiveness of the teaching profession. Together with salaries (see Indicator D3) and average class sizes (see Indicator D2), this indicator presents some key measures of the working lives of teachers and school heads.

For teachers, the proportion of their statutory working time spent teaching provides information on the amount of time available for non-teaching activities, such as lesson preparation, marking students’ work, in-service training and staff meetings. A larger proportion of statutory working time spent teaching may indicate that a lower proportion of working time is devoted to tasks such as assessing students and preparing lessons, as stated in regulations. It could also indicate that teachers have to perform these tasks in their own time and hence work more hours than required by their statutory working hours. In some countries, actual working practices of teachers and school heads may have differed from the statutory requirements during the COVID-19 pandemic, due to school closures and changes in learning environment related to the sanitary measures (e.g. remote learning, sanitary restrictions upon school reopening) (see The state of global education – 18 months into the pandemic (OECD, 2021[1]) and Annex 3 for more information).

In addition to class size and the ratio of students to teaching staff (see Indicator D2), students’ hours of instruction (see Indicator D1), and teachers’ salaries (see Indicator D3), the amount of time teachers spend teaching also affects the financial resources countries need to allocate to education (see Indicator C7).

Other findings

The number of teaching hours per year required of the average teacher in pre-primary, primary and secondary public schools varies considerably across OECD countries and tends to decrease as the level of education increases.

Required teaching time in public schools varies more across OECD countries and economies at pre-primary level than at any other level, ranging from 532 hours in Mexico to 1 755 hours in Germany.

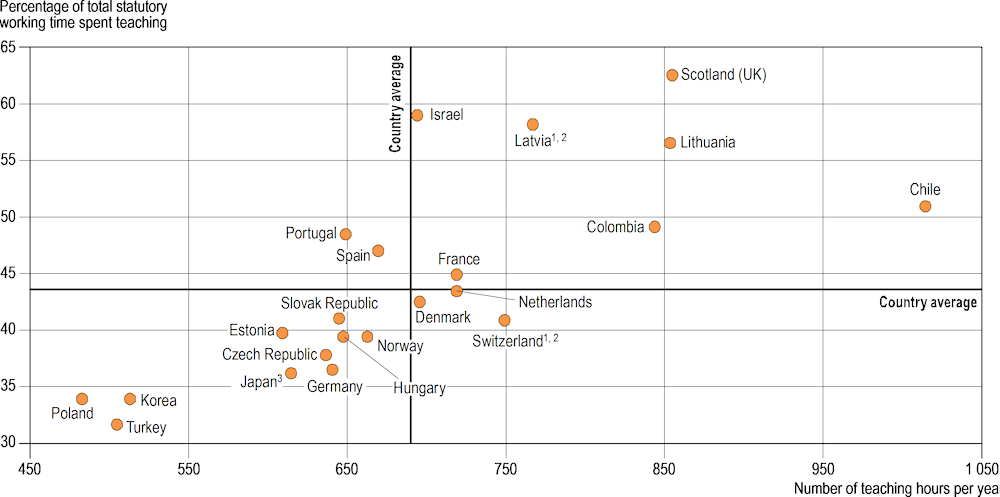

At lower secondary level, teachers spend 44% of their working time on teaching on average, ranging from 35% or less in Korea, Poland and Turkey to 63% in Scotland (United Kingdom). During their working time, teachers in most countries are required to perform various non-teaching tasks, such as lesson planning/preparation, marking students’ work, and communicating or co-operating with parents or guardians.

In 17 OECD countries and economies, teachers’ statutory working time includes working time during students’ school holidays in at least one level of education. In most of these countries, working time during school holidays is required to be spent on specific activities, such as preparing for the next school term, or individual and/or collective professional development activities.

In more than half of OECD countries, official documents explicitly state that school heads have additional tasks and responsibilities (e.g. teaching students, communication with parents) on top of their managerial and leadership roles.

Analysis

Teaching time of teachers

At pre-primary, primary and secondary levels, countries vary considerably in their annual statutory teaching time – the number of teaching hours per year required of a full-time teacher in a public school. Variations in how teaching time is regulated and/or reported across countries may explain some of the differences in statutory teaching time between countries (Box D4.1). In some countries, teaching time also varies at the subnational level (Box D4.2).

Box D4.1. Comparability of statutory teaching and working time data

Teaching time of teachers

Data on teaching time in this indicator refer to net contact time as stated in the regulations of each country. The international data collection exercise gathering this information ensures that similar definitions and methodologies are used when compiling the data in all countries. For example, teaching time is converted into hours (of 60 minutes) to avoid differences resulting from the varying length of teaching periods between countries. The impact on the comparability of data of differences in the way teaching time is reported in regulations is also minimised as much as possible.

Moreover, official documents might regulate teaching time as a minimum, typical or maximum time, and these differences may explain some of the differences reported between countries. While most data refer to typical teaching time, about one-third of countries report maximum or minimum values for teaching time (see Table X3.D4.3 in Annex 3).

Statutory teaching time in this international comparison excludes preparation time and periods of time formally allowed for breaks between lessons or groups of lessons. However, at pre-primary and primary levels, short breaks (of ten minutes or less) are included in the teaching time if the classroom teacher is responsible for the class during these breaks (see the Definitions section).

Other activities of teachers, such as professional development days (including attending conferences) and student examination days, are also requested to be excluded from the teaching hours reported in this indicator. At each level of general education, about two-thirds of the countries and economies with available information are able to exclude the number of days spent on these activities from statutory teaching time. However, in the remaining countries, the regulations do not always specify the number of days devoted to some of these activities and/or whether teachers are required to conduct these activities outside of scheduled teaching times, making it difficult to estimate and exclude them from teaching time.

One in four countries and economies cannot exclude professional development days from teaching time at all levels of general education. In these countries, the regulations specify some days of professional development activities for all teachers, but the impact on reported teaching time is difficult to estimate as the number of days and how they are organised during the school year may vary across schools or subnational entities. Similarly, about one-quarter of countries and economies with available information cannot exclude student examination days from teaching time at each level of general education. In many of these countries, regulations include some guidelines on the number of student examination days, but they are not clear about whether scheduled teaching time is reduced by the time devoted to examinations, or by how much. Overall, not excluding the time devoted to professional development and student examinations may result in annual teaching time being overestimated by approximately one to five days in these countries (see Table X3.D4.4 in Annex 3 for more information).

Other forms of professional development activities and student examinations may result in the overestimation of teaching time, even if they are not required to be excluded from teaching time. Examples include professional development activities required for specific groups of teachers only (when regulations do not explicitly forbid them from participating during their scheduled teaching time) and compulsory standardised student assessments conducted for only a few hours of the school day. The complexity of estimation and the fact that only some teachers participate in these activities make it difficult to standardise the reporting practice across all countries to exclude these activities from teaching time.

Working time for teachers and school heads

Total working time data in this indicator refer to required working hours during the reference year as indicated in the official documents such as legal documents and collective agreements for teachers and/or school heads, or general labour law with specific guidance for these professions. In some countries such as France, Japan, Korea, Portugal (school heads), Switzerland (teachers) and Turkey, the statutory working time for teachers and/or school heads is not specific to these professions and refers to working time of civil servants or other workers in general. Since working time can be defined in various units (hours per week, per month or per annum, for example), some calculation may be required to estimate the annual working time when working time is defined based on a unit other than annual number of hours.

Total working time refers to typical working time of teachers in 64% of countries and economies and to typical working time of school heads in 71% of countries and economies. In other countries and economies, total working time refers to either maximum or minimum required working time. For example, statutory total working time for teachers in England (United Kingdom) and Korea and for school heads in Ireland refers to a minimum number of working hours. On the contrary, total statutory working time of teachers and school heads is defined as a maximum number of working hours in some countries, for example, in Chile, Norway, Poland and Scotland (United Kingdom) (see Tables X3.D4.3 and X3.D4.8 in Annex 3).

More detailed information on the reporting practices on teaching time and working time for all participating countries and economies is available in Annex 3.

Box D4.2. Teaching and working time at the subnational level (2020)

There are regional differences in teachers’ statutory teaching and working time in the four countries reporting subnational data (Belgium, Canada, Korea and the United Kingdom). Only in Canada did the number of weeks of teaching (at pre-primary, primary, and lower and upper secondary levels) vary between regions (from 36 to 38 weeks) in 2020; in Belgium, Korea and the United Kingdom, the number of weeks of teaching is the same across subnational regions. However, overall figures for the number of weeks of teaching can mask differences in teaching time in terms of days or hours of teaching at the subnational level.

The four countries show different patterns of variation at the subnational level. In Belgium, the number of days of teaching varies much more (in relative terms) between the Flemish and French Communities than the number of hours of teaching (except in vocational upper secondary programmes). For example, in general upper secondary programmes, the number of days of teaching is 12% higher in the French Community than it is in the Flemish Community (178 days compared to 159 days) due to differences in how a school day is defined in the regulations. However, teaching hours vary by only 3% between the two communities (616 hours in the Flemish Community compared to 601 hours in the French Community). In contrast, in Canada, the number of days teaching at primary and secondary levels varies by 6% across the different provinces and territories (between 180 days and 190 days), but teaching hours vary much more. At the primary level, teaching time in the region with the longest teaching hours is 35% higher than teaching time in the region with the shortest teaching hours (945 hours compared to 700 hours). For lower and upper secondary general programmes, the difference reaches 54% (947 hours compared to 615 hours). In Korea, there is no variation between subnational entities in the number of teaching days, but teaching hours for general programmes vary by 7% at upper secondary level (from 514 hours to 551 hours) and by 32% at lower secondary level (from 437 hours to 575 hours). They also vary by 12% at the primary level (from 632 hours to 706 hours) and by 21% at the pre-primary level (from 728 hours to 878 hours).

However, caution is necessary when comparing information at the subnational level due to the following considerations: potential differences in the regulations between countries and between subnational regions within countries, how data are reported for the different subnational regions, and varying data availability for subnational regions within countries. For example, typical teaching time is reported for the subnational regions of Belgium, but mandated or estimated teaching time is reported for the different subnational regions in Canada (for more information on potential differences in the data reported, see Box D4.1).

Source: Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org.

Across countries and economies with available data, statutory teaching time in public schools varies more at pre‑primary level than at any other level. On average across OECD countries and economies, pre-primary teachers are required to teach 989 hours per year, spread over 41 weeks or 195 days. Their annual number of teaching days ranges from 158 days in the Flemish Community of Belgium to 225 days in Germany and Norway and their annual teaching hours range from 532 hours in Mexico to 1 755 hours in Germany. These large variations across countries and economies result from the combination of the variations in the length of school year and the number of daily teaching hours. For example, pre-primary teachers in Mexico teach an average of 2.7 hours per day over 200 days, whereas in Germany they teach an average of 7.8 hours per day over 225 days (Table D4.1).

Primary school teachers are required to teach 791 hours per year in public institutions on average. In most countries and economies with available data, daily teaching time ranges from three to six hours a day, with an OECD average of more than four hours per day. There is no set rule on how teaching time is distributed throughout the year. For example, primary school teachers in Mexico teach 800 hours per year, 78 hours more than in Turkey. However, as teachers teach more days in Mexico than in Turkey (200 days compared to 181 days), teachers in both countries teach 4 hours a day on average (Table D4.1).

Lower secondary school teachers in general programmes in public institutions are required to teach an average of 723 hours per year. Teaching time is less than 600 hours in Finland, Korea, Poland, the Russian Federation and Turkey, and exceeds 1 000 hours in Chile, Costa Rica and Mexico (Table D4.1)

However, the reported hours for Finland and Korea refer to the minimum time teachers are required to teach (Box D4.1) and teachers in Poland can be obliged to teach as much as 25% of the statutory time as additional overtime, at the discretion of the school head.

A teacher in general upper secondary education in public institutions has an average teaching load of 685 hours per year. Teaching time ranges from fewer than 500 hours per year in Poland and the Russian Federation to more than 1 000 hours in Chile and Costa Rica. Teachers in Finland, Japan, Korea, Norway, Poland, the Russian Federation and Turkey teach for less than three hours per day, on average, compared to more than six hours in Costa Rica (Table D4.1).

Teaching time requirements may, however, change throughout a teacher’s career. In a number of countries, some new teachers have a reduced teaching load as part of their induction programmes. Some countries also encourage older teachers to stay in the teaching profession by reducing their teaching hours. For example, in Chile and Portugal, teachers may have a reduced teaching workload based on their number of years in the profession and/or age.

Differences in teaching time by level of education

Teaching time tends to decrease as the level of education increases. In most countries, statutory teaching time at the pre-primary level is more than at the upper secondary level (general programmes). The exceptions are Chile and Scotland (United Kingdom), where teachers are required to teach the same number of hours at all levels of education; and Australia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Lithuania and Mexico, where upper secondary school teachers are required to teach more hours than pre-primary school teachers (Table D4.1).

The largest difference in teaching time requirements is between the pre-primary and primary levels of education. On average, pre-primary school teachers are required to spend about 25% more time in the classroom than primary school teachers. In the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Latvia and Slovenia, pre-primary school teachers are required to teach at least twice the number of hours per year as primary school teachers (Table D4.1).

In Austria, France, Ireland, Korea, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain and Turkey, primary school teachers have at least 25% more annual teaching hours than lower secondary school teachers, while there is no difference in Chile, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Scotland (United Kingdom) and Slovenia. The teaching load for primary school teachers is 3-6% lighter than for lower secondary school teachers in Costa Rica, Estonia and Lithuania; 17% lighter in Latvia; and 23% lighter in Mexico (Table D4.1).

Teaching time at lower and upper secondary levels is similar across most countries. However, annual required teaching time at the lower secondary level is at least 20% more than at the upper secondary level in Japan, Mexico and Norway, and up to 35% in Denmark (Table D4.1).

Actual teaching time

Statutory teaching time, as reported by most of the countries in this indicator, refers to teaching time as defined in regulations. However, individual teachers’ teaching time may differ from the regulations, because of overtime for example. Actual teaching time is the annual average number of hours that full-time teachers teach a group or a class of students, including overtime (it also includes activities other than teaching, such as keeping order and administrative tasks), and it thus provides a full picture of teachers’ actual teaching load.

While only a few countries were able to report both statutory and actual teaching time, these data suggest that actual teaching time can sometimes differ from the statutory requirements. For example, lower secondary teachers actually teach 6-10% more hours than their statutory teaching time in Lithuania, New Zealand and Slovenia, and up to 21% more hours in Poland (OECD, 2021[2]).

Differences between statutory and actual teaching time can be the result of overtime due to teacher absenteeism or shortages, or may be explained by the nature of the data, as figures on statutory teaching time refer to official requirements and agreements, whereas actual teaching time is based on administrative registers, statistical databases, representative sample surveys or other representative sources (Box D4.1).

Teaching time of school heads

Whereas teaching is the primary or main responsibility of teachers, it can also be part of the responsibilities of school heads in some countries.

Among the 28 countries and economies with available information, school heads in pre-primary institutions are required to take some teaching responsibility in 13 countries and economies (46%), can voluntarily teach in 3 countries (11%) and are not required to teach in 12 countries (43%). In primary education, teaching is required from school heads in more than half of the countries with available data (17 out of 33 countries and economies). Teaching responsibilities become less common for school heads at secondary level. In general lower and upper secondary education, school heads are required to teach in 13 out of 33 countries and economies (39%), are free to teach at their own discretion in 5 countries and economies (15%), and are not required to teach in 15 countries (45%). In all the countries and economies with available data, the teaching responsibilities of school heads in secondary education are similar in general and vocational programmes (Table D4.6, available on line).

Most of the countries where teaching is one of the responsibilities of school heads do not set a specific number of teaching hours for them, but rather define a minimum and/or maximum number of teaching hours. In lower secondary general programmes, for example, the minimum statutory teaching time for school heads (converted into hours per year) ranges from 0 hours (i.e. exempt from teaching) to 194 hours, and the maximum statutory teaching time from 144 hours to 594 hours. In most of these countries, teaching represents less than 30% of school heads’ statutory working time, but the proportion reaches 32% in the Slovak Republic and exceeds 73% in Ireland (in the Education and Training Board sector) (Table D4.6, available on line). The maximum teaching time is usually only required for school heads in specific circumstances. For example, in Ireland, almost all school heads at secondary level actually have either no or minimal teaching hours (for more information on minimum and/or maximum teaching time requirements, refer to Table X3.D4.10 in Annex 3).

Although teaching may be required for school heads at all levels of education in a given country, their minimum and maximum teaching requirements could vary across levels of education. In a majority of the countries with teaching requirements, the number of teaching hours required from school heads decreases as the level of education increases. The exception is Turkey, where teaching requirements for school heads are the same at all levels of education (Table D4.6, available on line). In almost all countries, the teaching requirements for school heads do not vary between general and vocational programmes (Table D4.6, available on line).

In all countries where school heads have teaching responsibilities except Turkey, the requirements vary based on specific criteria related to school heads. In a large majority of these countries, the characteristics of the school, such as its size (number of students, teachers and/or classes) and/or the level of education it covers, are important determinants of the teaching requirements. Other criteria can also be considered, for example the socio-economic status of the regions in Ireland.

Working time of teachers

In the majority of countries, teachers’ working time is partly determined by the statutory teaching time specified in working regulations. In addition, in most countries, teachers are formally required to work a specific number of hours per year, as stipulated in collective agreements or other contractual arrangements. This may be specified either as the number of hours teachers must be available at school for teaching and non-teaching activities, or as the number of total working hours. Both correspond to official working hours as specified in contractual agreements, and countries differ in how they allocate time for each activity.

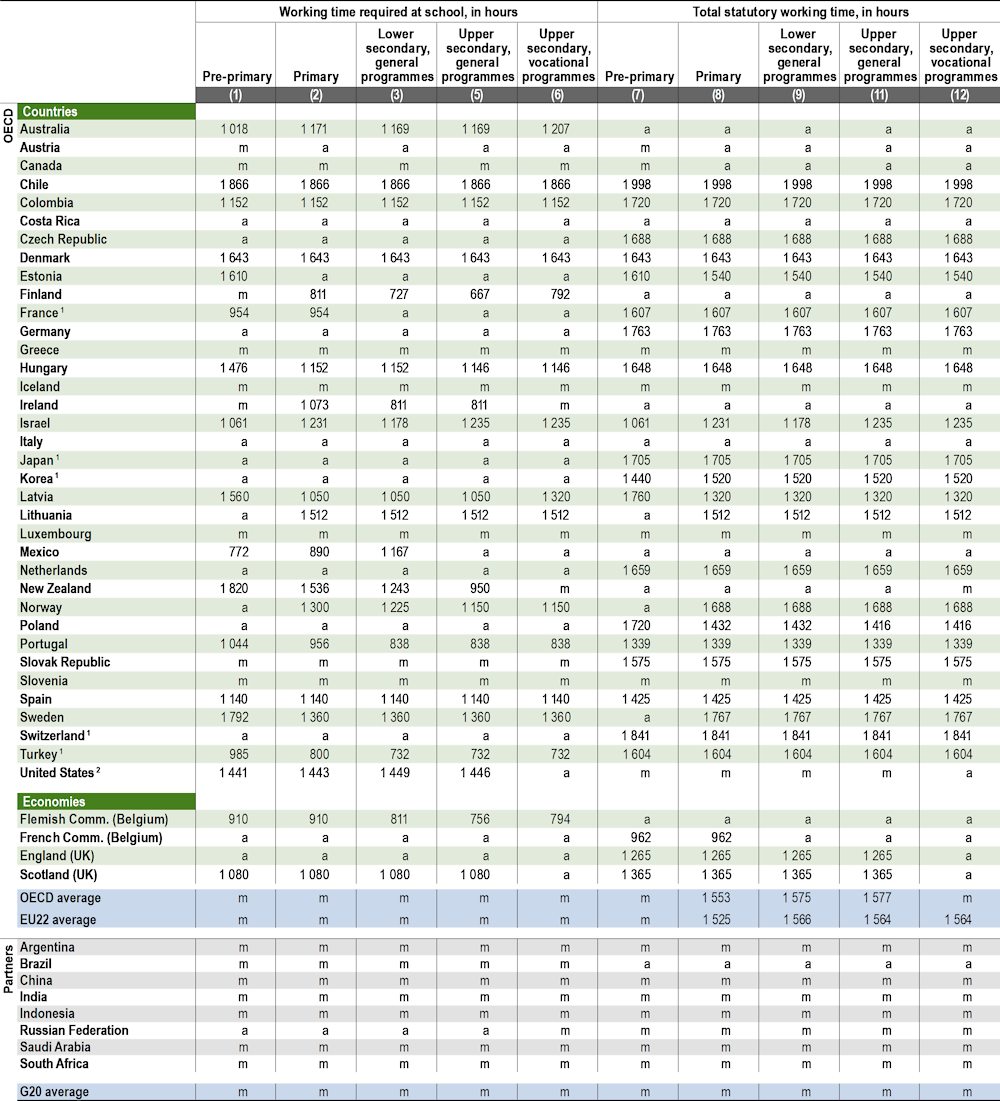

More than half of OECD countries and economies specify the length of time teachers are required to be available at school, for both teaching and non-teaching activities, for at least one level of education. In over one-third of these countries with data, the difference between the time upper secondary school teachers and pre-primary school teachers are required to be available at school is less than 5%. However, in nearly half of these countries and economies (the Flemish Community of Belgium, Hungary, Latvia, New Zealand, Portugal, Sweden and Turkey), pre-primary teachers are required to be available at school for at least 20% more hours than upper secondary school teachers and the difference even exceeds 40% in Latvia and New Zealand (although total statutory working time is the same for both levels in Hungary, Sweden and Turkey) (Table D4.2).

In some other countries, teachers’ total annual statutory working time (at school and elsewhere) is specified, but the allocation of time spent at school and time spent elsewhere is not (however, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, actual working practices could have been different from statutory requirements (OECD, 2021[1])). This is the case in the Czech Republic, England (United Kingdom), Estonia (in primary and secondary education), the French Community of Belgium (in pre-primary and primary education), Germany, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Poland and Switzerland (Table D4.2). The variation across countries in the number of annual working hours of teachers can also result from the fact that total working time spans over students’ school vacations. For example, at general lower secondary level, teachers’ total working time ranges from 1 178 hours in Israel, where teachers are not required to work during school vacation, to 1 998 hours in Chile, where teachers work up to 3 weeks during school vacations (Figure D4.2). In 17 OECD countries and economies, teachers’ statutory working time includes working time during students’ school holidays in at least one level of education. In many countries, working time during school holidays is required to be spent on specific activities, such as preparing for the next school term, and individual and/or collective professional development activities (see Table X3.D4.5 in Annex 3 for details).

1. Teachers' working time requirements refer to those of civil servants.

2. Reference year differs from 2020. Refer to the source table for details.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of teachers’ total working hours and then working hours at school in general lower secondary education.

Source: OECD (2021), Tables D4.2 and D4.3. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Non-teaching time

Although teaching time is a substantial component of teachers’ workloads, other activities such as assessing students, preparing lessons, correcting students’ work, in-service training and staff meetings should also be taken into account when analysing the demands placed on them in different countries. The amount of time available for these non-teaching activities varies across countries; a larger proportion of statutory working time spent teaching may indicate that a lower proportion of working time is devoted to these activities.

Even though teaching is a core activity for teachers, in a large number of countries, teachers spend most of their working time on activities other than teaching. In the 22 countries and economies with data for both teaching and total working time for lower secondary teachers, 44% of teachers’ working time is spent on teaching on average, with the proportion ranging from 35% or less in Korea, Poland and Turkey to at least 50% in Chile, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania and Scotland (United Kingdom) (Figure D4.3).

Figure D4.3. Percentage of lower secondary teachers’ working time spent teaching (2020)

Net teaching time as a percentage of total statutory working time in general programmes in public institutions

Note: For better interpretation, please refer to the notes on the nature of the data in Table D4.1.

1. Actual teaching time.

2. Reference year differs from 2020. Refer to the source table for details.

3. Average planned teaching time in each school at the beginning of the school year.

Source: OECD (2021), Tables D4.1 and D4.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

While the proportion of working time spent teaching increases with the number of teaching hours per year, there are some variations between countries. For example, Denmark and Israel have a similar number of teaching hours (696 hours in Denmark and 695 hours in Israel), but 42% of teachers’ working time is spent on teaching in Denmark, compared to 59% in Israel. In some countries, teachers devote similar proportions of their working time to teaching, despite having considerably different teaching hours. For example, in Estonia and Switzerland, lower secondary teachers spend about 40-41% of their working time teaching, but teachers teach 609 hours in Estonia, compared to 750 hours in Switzerland (Figure D4.3).

In some countries, such as Austria (primary and secondary levels), Costa Rica, the French Community of Belgium (lower and upper secondary levels), Italy, Lithuania (pre-primary) and Mexico (upper secondary level), there are no formal requirements for time spent on non-teaching activities (Table D4.2). However, this does not mean that teachers are given total freedom to carry out other tasks. In Italy, teachers are required to perform up to 80 hours of scheduled non-teaching collegial work at school per year. Of these 80 hours, up to 40 are dedicated to meetings of the teachers’ assembly, staff planning meetings and meetings with parents, with the remaining 40 compulsory hours dedicated to class councils.

Non-teaching tasks and responsibilities of teachers

Non-teaching tasks are a part of teachers’ workload and working conditions. The non-teaching activities required by legislation, regulations or agreements between stakeholders (e.g. teachers’ unions, local authorities and school boards) do not necessarily reflect teachers’ actual participation in non-teaching activities, but they provide insight into the breadth and complexity of teachers’ roles.

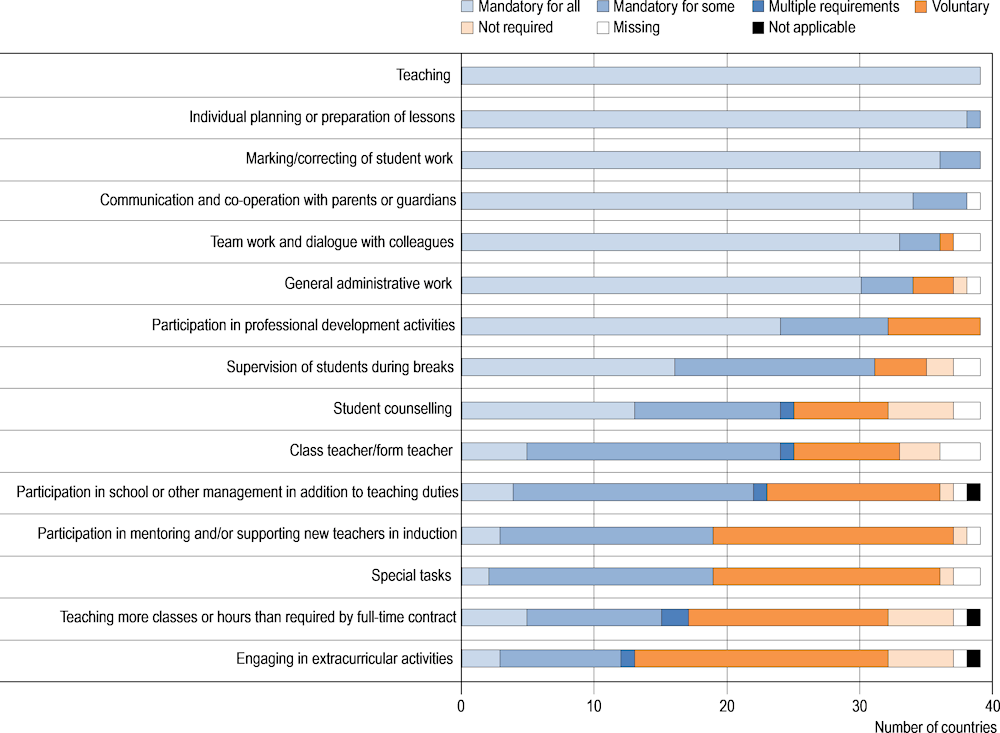

Individual teachers often do not have the authority to choose whether to perform certain tasks related to teaching. According to regulations for general lower secondary teachers, non-teaching tasks for teachers such as individual planning or preparing lessons, marking and correcting student work, and communicating and co-operating with parents are mandatory during their statutory working time in more than 34 out of the 39 countries and economies with available data. General administrative work and teamwork and dialogue with colleagues are also required in at least 30 countries and economies, and can be decided at the school level in at least 3 other countries with available data for each type of task. For such mandatory tasks, incentives such as reductions in teaching time and financial compensation are rare (Table D4.4, available on line).

Responsibilities such as being class/form teacher, participating in mentoring programmes, and/or supporting new teachers in induction programmes or participating in school or other management in addition to teaching duties are not required for all general lower secondary teachers in more than two out of five countries. In more than half of these countries, participation in school or other management activities can result in specific compensation for teachers. In some countries, their teaching time might be reduced to balance the workload between teaching and the other responsibilities, in addition to financial compensation (Figure D4.4 and Table D4.5, available on line).

Of the various tasks teachers might perform, full-time classroom teachers (in general lower secondary education) are either required or asked to perform student counselling in about two out of three countries and economies with available information. However, in some countries, not all teachers can perform student counselling. For example, in Israel, only teachers with a master’s degree or higher can perform this duty (Table D4.5, available on line).

Teachers not only perform the tasks that are required by regulations or school heads, they also often perform tasks voluntarily. In at least 17 countries and economies at the general lower secondary level, individual teachers decide themselves whether to engage in extracurricular activities or whether to train student teachers. Teaching more classes or hours than their full-time contract requires is also a voluntary decision by teachers in more than two-fifths of the countries and more than two‑thirds of these countries offer financial compensation for this additional teaching (Table D4.5, available on line).

Participation in professional development activities is considered an important responsibility of teachers at all levels of education, as it is mandatory for teachers at all levels in 23 countries. Participation is required at the discretion of individual schools in ten countries for at least one level of education. Only eight countries allow teachers to participate in professional development activities at their own discretion at all levels with data (Table D4.5, available on line). Regardless of the requirement, a large majority of teachers in OECD countries participate in professional development activities (OECD, 2019[3]).

In general, requirements to perform certain tasks and responsibilities do not vary much across levels of education. However, there can be some differences, reflecting the changing needs of students at different levels of education. For example, lower secondary teachers are required to supervise students during breaks in 16 countries, but this is much more widespread at pre-primary (22 countries) and primary (21 countries) level (Table D4.4).

Differences in task requirements between countries could explain the differences in the proportion of statutory working time spent on non-teaching tasks. For example, Japan is one of the four countries where engaging in extracurricular activities is mandatory at lower secondary level. Indeed, lower secondary teachers in Japan reported having spent the highest proportion of actual working time among OECD countries (13%) on this task (OECD, 2019[3]).

Figure D4.4. Task requirements of teachers, by tasks and responsibilities (2020)

Lower secondary teachers in public institutions

Note: "Mandatory for some" indicates that the specified task or responsibility is mandatory at the discretion of individual schools or in some subnational entities.

Tasks and responsibilities are listed in decreasing order of the number of countries where the specified item is mandatory to some extent.

Source: OECD (2021), Tables D4.4 and D4.5, available on line only. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Working time of school heads

As with teachers’ working time, many OECD and partner countries define school heads’ statutory working time under relevant regulations or collective or individual contracts. In France, Japan, Korea, Mexico (upper secondary education), Portugal and Turkey, civil servants’ regulations apply for school heads’ working time (as for teachers, except in Mexico). Only in England (United Kingdom), the Flemish Community of Belgium, Germany (in most Länder) and Italy are there no official documents specifying quantitative information on the working time for school heads (Figure D4.2 and Table X3.D4.9 in Annex 3).

According to level of education, on average across OECD countries and economies, school heads work 44 weeks or 212-215 days per year. On average, school heads’ annual statutory working hours do not vary much between levels of education: they average 1 656 hours at pre-primary level, 1 627 hours at primary level, 1 626 hours at lower secondary level, and 1 627 hours at upper secondary level. There is no difference in the number of statutory working hours between general and vocational programmes in the countries with both programmes in lower and/or upper secondary education, except in Lithuania. Across all levels of education, school heads in Chile have the longest hours (1 998 hours per year). In contrast, school heads’ statutory working hours are the lowest in Mexico (at pre-primary level) and Ireland (for primary and lower and upper secondary general programmes) where statutory working hours are below 1 300 hours per year (Table D4.3).

In 20 out of the 28 OECD and partner countries and economies with available data (71% of countries), school heads’ annual working hours do not vary much across levels of education. In the remaining eight countries where their statutory working time does vary, school heads in pre-primary and primary education generally work more hours per year than those in secondary education. For example, school heads’ statutory hours in pre-primary schools are 1-8% higher than in primary and secondary schools in Australia, Estonia, Finland and New Zealand. In Mexico, school heads have shorter working hours at pre-primary and primary levels than at lower secondary level (by 14%) and at upper secondary level (by 24%) (Table D4.3).

In about two-thirds of the OECD countries and economies with available data, the statutory working time of school heads includes working during students’ (seasonal) school holidays. The amount worked during students’ school holidays could range from about 1 week in Austria and the Netherlands (at the request of the school heads’ employers) to 11 weeks in Turkey. During students’ school holidays, school heads in some of these countries are required to prepare for the new school semester and arrange professional development programmes, etc. In the other one-third of countries, the regulations do not require school heads to work during students’ school holidays. Nevertheless, the actual practice could be different. For example, school heads in Ireland may work during at least a part of students’ school holidays, although it is not included in their statutory working time (Table X3.D4.9 in Annex 3).

Tasks and responsibilities of school heads

In more than half of the OECD and partner countries with available data, regulations explicitly state that school heads are expected to play managerial and leadership roles. In addition, school heads can be required to perform other tasks and responsibilities, such as managing human/financial resources, organising professional development activities and students’ educational activities, and teaching students, as well as facilitating good relations with parents, education inspectorates and/or the government. In a majority of countries, the tasks and responsibilities required from school heads do not vary across levels of education or educational programmes (for more details, refer to Table X3.D4.9 in Annex 3).

However, in about one-quarter of countries with available information (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden), official documents on the working conditions of school heads do not detail their responsibilities and tasks. School heads in these countries may have more autonomy in organising their work and responsibilities (Table X3.D4.9 in Annex 3).

Definitions

Actual teaching time is the annual average number of hours that full-time teachers teach a group or class of students. It includes all extra hours, such as overtime. Data on these hours can be sourced from administrative registers, statistical databases, representative sample surveys or other representative sources.

The number of teaching days is the number of teaching weeks multiplied by the number of days per week a teacher teaches, minus the number of days on which the school is closed for holidays.

The number of teaching weeks refers to the number of weeks of instruction excluding holiday weeks.

Statutory teaching time is defined as the scheduled number of 60-minute hours per year that a full-time teacher (or a school head) teaches a group or class of students, as set by policy, their employment contract or other official documents. Teaching time can be defined on a weekly or annual basis. Annual teaching time is normally calculated as the number of teaching days per year multiplied by the number of hours a teacher teaches per day (excluding preparation time). It is a net contact time for instruction, as it excludes periods of time formally allowed for breaks between lessons or groups of lessons and the days that the school is closed for holidays. At pre-primary and primary levels, short breaks between lessons are included if the classroom teacher is responsible for the class during these breaks.

Total statutory working time refers to the number of hours that a full-time teacher or school head is expected to work as set by policy. It can be defined on a weekly or annual basis. It does not include paid overtime. According to a country’s formal policy, working time can refer to:

the time directly associated with teaching and other curricular activities for students, such as assignments and tests

the time directly associated with teaching and other activities related to teaching, such as preparing lessons, counselling students, correcting assignments and tests, professional development, meetings with parents, staff meetings, and general school tasks.

Working time required at school (of teachers) refers to the time teachers are required to spend working at school, including teaching and non-teaching time.

Methodology

In interpreting differences in teaching hours among countries, net contact time, as used here, does not necessarily correspond to the teaching load. Although contact time is a substantial component of teachers’ workloads, preparing for classes and necessary follow-up, including correcting students’ work, also need to be included when making comparisons. Other relevant elements, such as the number of subjects taught, the number of students taught and the number of years a teacher teaches the same students, should also be taken into account.

For more information please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparable Education Statistics 2018 (OECD, 2018[4]) and Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Source

Data are from the 2020 OECD-INES-NESLI Survey on Working Time of Teachers and School Heads and refer to the school year 2019/20 (statutory information) or school year 2018/19 (actual data).

References

[2] OECD (2021), “Education at a Glance: Teachers’ teaching and working time”, OECD Education Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/d3ca76db-en (accessed on 14 September 2021).

[1] OECD (2021), The State of Global Education: 18 Months into the Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1a23bb23-en.

[3] OECD (2019), TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners, TALIS, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

[4] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[5] OECD/UIS/UNESCO/UNICEF/WB (2021), Special Survey on COVID Database, https://www.oecd.org/education/Preliminary-Findings-COVID-Survey-OECD-database.xlsx (accessed on 17 May 2021).

Indicator D4 tables

Tables Indicator D4. How much time do teachers and school heads spend teaching and working?

|

Table D4.1 |

Organisation of teachers’ teaching time (2020) |

|

Table D4.2 |

Organisation of teachers’ working time (2020) |

|

Table D4.3 |

Organisation of school heads’ working time (2020) |

|

WEB Table D4.4 |

Tasks of teachers, by level of education (2020) |

|

WEB Table D4.5 |

Other responsibilities of teachers, by level of education (2020) |

|

WEB Table D4.6 |

Teaching requirements of school heads (2020) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2021. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table D4.1. Organisation of teachers' teaching time (2020)

Number of statutory teaching weeks, teaching days and net teaching hours in public institutions over the school year

Note: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, statutory requirements on organisation of teachers’ teaching time may be adjusted temporarily in some countries. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data on vocational programmes at lower secondary level (i.e. Columns 4, 10 and 16) are available for consultation on line. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Typical teaching time (teaching time required from most teachers when no specific circumstances apply to teachers).

2. Maximum teaching time.

3. Minimum teaching time.

4. Average planned teaching time in each school at the beginning of the school year.

5. Actual teaching time (in Latvia except for pre-primary level).

6. Year of reference 2019 for Latvia (except for pre-primary level) and Switzerland, 2017 for the Russian Federation and 2016 for the United States.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D4.2. Organisation of teachers' working time (2020)

Teachers' statutory working time at school and total working time in public institutions over the reference year

Note: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, statutory requirements on organisation of teachers’ working time may be adjusted temporarily in some countries. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data on vocational programmes at lower secondary level (i.e. Columns 4 and 10) are available for consultation on line. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Working time requirements refer to those of civil servants.

2. Year of reference 2016.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D4.3. Organisation of school heads' working time (2020)

Number of statutory working weeks, working days and total working hours in public institutions over the reference year

Note: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, statutory requirements on the organisation of school heads' working time may be adjusted temporarily in some countries. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data on vocational programmes at lower secondary level (i.e. Columns 4, 10 and 16) are available for consultation on line. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Working time requirements refer to those of civil servants.

2. Actual data.

3. Year of reference 2016.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.