Across OECD countries, there is nearly universal coverage of basic education for 6-14 year-olds, as enrolment rates for this age group reached or exceeded 95% in all OECD countries. In addition, 84% of the population is enrolled in education between the age of 15 and 19 on average across OECD countries. The highest share is in Belgium, Ireland and Slovenia, where the overall enrolment rate reaches 94% (Table B1.1).

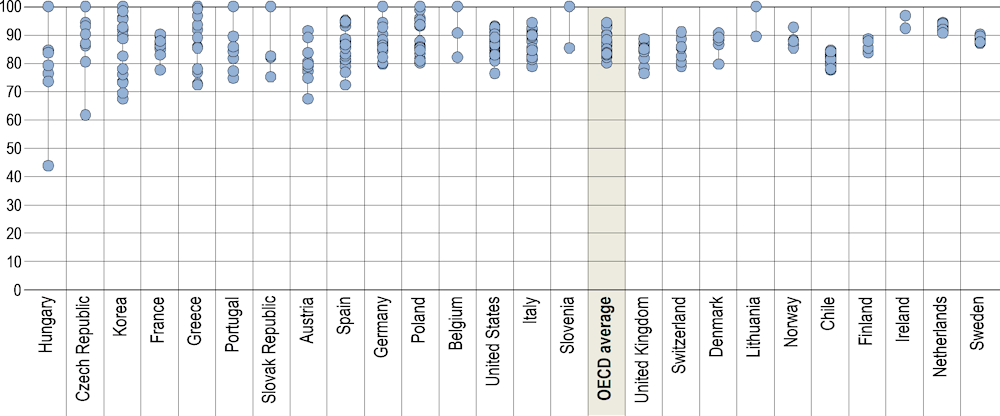

Over all education levels combined, enrolment rates are 7 percentage points higher on average for 20-24 year‑old women than for men. The largest gap in this age group is found in Slovenia (20 percentage points) and the gap is at least 15 percentage points in Argentina, Israel and Poland (Figure B1.1).

On average across OECD countries with available data, boys are more likely to repeat a grade than girls and represent 61% of the number of repeaters in lower secondary education and 57% in upper secondary education (Figure B1.2).

Education at a Glance 2021

Indicator B1. Who participates in education?

Highlights

1. Year of reference 2018.

2. Excludes post-secondary non-tertiary programmes.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the difference between 20-24 year-old women and men.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2021), Education at a Glance Database. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Context

Pathways through education can be diverse, both across countries and for different individuals within the same country. Experiences in primary and secondary education are probably the most similar across countries. Compulsory education is usually relatively homogeneous as pupils progress through primary and lower secondary education, but as people have different abilities, needs and preferences, most education systems try to offer different types of education programmes and modes of participation, especially at the more advanced levels of education, including upper secondary and tertiary education.

Ensuring that people have suitable opportunities to attain adequate levels of education is a critical challenge and depends on their ability to progress through the different levels of an educational system. Developing and strengthening both general and vocational education at upper secondary level can make education more inclusive and appealing to individuals with different preferences and aptitudes. Vocational education and training (VET) programmes are an attractive option for youth who are more interested in practical occupations and for those who want to enter the labour market earlier (OECD, 2019[1]). In many education systems, VET enables some adults to reintegrate into a learning environment and develop skills that will increase their employability.

To some extent, the type of upper secondary programme students attend conditions their educational tracks. Successful completion of upper secondary programmes gives students access to post-secondary non-tertiary education programmes, where available, or to tertiary education. Upper secondary vocational education and post-secondary non-tertiary programmes, which are mostly vocational in nature, can allow students to enter the labour market earlier, but higher levels of education often lead to higher earnings and better employment opportunities (see Indicators A3 and A4). Tertiary education has become a key driver of today’s economic and societal development. The deep changes that have occurred in the labour market over the past decades suggest that better-educated individuals have (and will continue to have) an advantage as the labour market becomes increasingly knowledge-based. As a result, ensuring that a large share of the population has access to a high-quality tertiary education capable of adapting to a fast-changing labour market are some of the main challenges tertiary educational institutions, and educational systems more generally, face today.

Other findings

In more than half of the countries with data available, the variation of the enrolment rate of 15-19 year-olds between subnational regions is larger than the variation of national values across different OECD countries. In Chile, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, the difference between maximum and minimum enrolment rates within each country is relatively small (7 percentage points or less) (Figure B1.3).

Enrolment in education is less common among the older population, as students graduate and transition to the labour market: the OECD average enrolment rates in all levels of education reach 16% among 25-29 year-olds, 6% among 30-39 year-olds and 2% among 40-64 year-olds (Table B1.1)..

The share of repeaters varies to a large extent by country and by educational level. It reaches 2% in lower secondary general programmes and 3% in upper secondary general education. Grade repetition is more common in upper rather than lower secondary education, especially in Austria, the Czech Republic, Portugal and Spain, where repeaters represent at least 7% of the enrolled students (Figure B1.2).

The range of enrolment rates is widest in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Korea with a difference of at least 33 percentage points between the highest and lowest enrolment rate of 15-19 year-olds across subnational regions (Figure B1.3).

Analysis

Compulsory education

In OECD countries, compulsory education typically begins with primary education, starting at the age of 6 (see Table X1.5 in Annex 1). However, in about one-third of OECD and partner countries, compulsory education begins earlier, while in Estonia, Finland, Indonesia, Lithuania, the Russian Federation and South Africa, compulsory education does not begin until the age of 7. Compulsory education usually ends with the completion or partial completion of upper secondary education at the age of 16 on average across OECD countries, ranging from 13 (Indonesia) or 14 (Korea) to 18 ( Belgium, Chile, Germany and Portugal). In Slovenia, compulsory education ends at age 14 with the completion of the primary and lower secondary education integrated programme. In the Netherlands, there is partial compulsory education (i.e. students must attend some form of education for at least two days a week) from the age of 16 until they are 18 or until they have completed a diploma. However, high enrolment rates extend beyond the end of compulsory education in a number of countries. On average across OECD countries, full enrolment (the age range when at least 90% of the population is enrolled in education) lasts 14 years, from the age of 4 to the age of 17. The period of full enrolment lasts between 11 and 16 years in most countries and reaches 17 years in Norway. It is shorter in Colombia, Mexico, the Slovak Republic and Turkey, and in partner countries such as Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa (Table B1.1).

In almost all OECD countries, the enrolment rate among 4-5 year-olds in education exceeded 90% in 2019. Enrolment at an early age is relatively common in OECD countries, with about one-third achieving full enrolment for 3-year-olds. Iceland, Korea, Norway and Sweden also have full enrolment for 2-year-olds (see Indicator B2). In other OECD countries, full enrolment is achieved for children at the age of 5, but this rises to the age of 6 in Finland, the Slovak Republic and Turkey. In all OECD countries, compulsory education comprises primary and lower secondary programmes. In most countries, compulsory education also covers, at least partially, upper secondary education, depending on the theoretical age range associated with the different levels of education in each country. There is nearly universal coverage of basic education, as enrolment rates among 6-14 year-olds reached or exceeded 95% in all OECD countries (Table B1.1).

Participation of 15-19 year-olds in education

In recent years, countries have increased the diversity of their upper secondary programmes. This diversification is both a response to the growing demand for upper secondary education and a result of changes in curricula and labour-market needs. Curricula have gradually evolved from separating general and vocational programmes to offering more comprehensive programmes that include both types of learning, leading to more flexible pathways into further education or the labour market.

Overall, 84% of the population is enrolled in education between the age of 15 and 19 on average across OECD countries. The share is the highest in Belgium, Ireland and Slovenia, where the overall enrolment rate reaches 94%. The enrolment rate of 15-19 year-olds was 1 percentage point higher in 2019 than in 2013, with the largest increases observed in Italy and Mexico (8 percentage points or more). Enrolment levels did not, however, improve in all OECD countries: for example, they fell by more than 3 percentage points among 15-19 year-olds in Germany, Hungary and Iceland (Table B1.1).

In 2019, enrolment rates among 15-16 year-olds (i.e. those typically in upper secondary programmes) reached at least 94% on average across the OECD. At age 17, 90% of individuals were enrolled in education on average across the OECD, reaching 100% in Ireland and Portugal. By contrast, fewer than 70% of 17-year-olds were enrolled in education in Colombia, Costa Rica and Mexico. Enrolment patterns start dropping significantly at age 18: 75% of 18-year-olds are enrolled in secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary, or tertiary education, on average across OECD countries. Declines in enrolment for this age group coincide with the end of upper secondary education. The drop in enrolment between age 17 and age 18 is at least 25 percentage points in Chile, Israel, Korea and Turkey. By the time students reach age 19, enrolment rates decrease to 60% on average across OECD countries (Table B1.3).

The share of students enrolled in each education level and at each age is illustrative of the different educational systems and pathways in different countries. As students get older, they move on to higher educational levels or types of programmes, and the enrolment rate in upper secondary education (combined general and vocational) decreases. Depending on the structure of the educational system, students across the OECD may start enrolling in post-secondary non-tertiary or tertiary education from the age of 17. However, this is still the exception for this age group, with 88% of 17-year-olds still enrolled in secondary education, on average across OECD countries. Students start diversifying their pathways significantly from age 18, although the age of transition between upper secondary and tertiary education varies substantially among countries. While at least 90% of 18-year-olds are still enrolled in upper secondary in Finland, Norway, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden, at least 50% of 18 year-olds in Greece and Korea are already starting their tertiary education. On average across OECD countries, 24% of 19-year-olds are still enrolled in secondary education. However, in Denmark and Iceland, at least 50% of 19‑year‑olds are still enrolled in secondary education. These high shares may partly be explained by the structure of the education system and the strength of the labour opportunities offered by vocational upper secondary programmes in these countries, making them more attractive than tertiary education. Enrolment of 19-year-olds in tertiary education averages 34% across OECD countries, ranging from 5% in Luxembourg (the low share is due in large part to the high number of students studying abroad) to 73% in Korea (Table B1.3).

Participation in formal education varies by gender, as female students outnumber male students in almost all age groups and at all education levels. However, the difference in enrolment rates between 15-19 year-old women and men reaches only 2 percentage points on average across the OECD. It is 5% in Israel and slightly negative (higher enrolment rate for men) in Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey (Figure B1.1). The largest differences between men and women in this age group are found in tertiary education in Australia, Austria, Belgium and the United States and in upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education in Luxembourg, where the enrolment rate is at least 6 percentage points higher for women than for men (Table B1.2).

Lower enrolment rates are often related to school drop-out and, indirectly, to lower school performance and grade repetition. Women have higher enrolment rates and better performance, while repetition rates are higher among men. Repetition rates are relatively low among OECD countries, but they also highlight a gender gap dimension that could help explain enrolment and performance gaps (see Box B1.1).

Box B1.1. Cross-country differences in grade repetition

Completing educational programmes at different ISCED levels over their lifetime allows individuals to progress to higher levels of education and empowers them throughout life to access and have better opportunities in the labour market. At the same time, dropping out or repeating a grade can lead to premature withdrawal from school and lower employability of school leavers, causing a loss for educational systems in terms of social and financial resources, such as students’ learning, school buildings’ usage and teachers’ work time (UNESCO International Bureau of Education, 1970[2]).

Equity in education can be related to the policies that schools employ to sort and select students. Grade repetition, the practice of retaining students in the same grade, is used to give struggling students more time to master grade-appropriate content before moving on to the next grade (and prevent them from dropping out). Even if research finds that grade repetition can be ineffective in enhancing the achievement of low performers in the short run (OECD, 2019[3]), early retention may lead to better outcomes than late retention and retained students may catch up after several years (Fruehwirth, Navarro and Takahashi, 2016[4]).

Socio-economically disadvantaged students with an immigrant background and boys are more likely to repeat grades than advantaged students (OECD, 2019[3]), and this could also lead to persisting socio-economic inequalities. Completion rates are usually lower for students from a disadvantaged background (e.g. lower educational status of parents, first-generation immigrants).

The way educational systems cope with students who repeat grades may differ to a large extent between countries and within the same countries, depending on educational levels, programmes, rural or urban areas, socio‑economic conditions, or other factors. In most countries, repeaters tend to be concentrated in the last two years before graduation, while in others, the distribution over different grades is more even. In a smaller number of countries, repeating grades is restricted by law and school regulations, and the concept of repeating does not even exist, especially at lower educational levels. This is the case for lower secondary education programmes in Norway, for upper secondary programmes in Finland and for both types of programmes in the United Kingdom. In Canada, lower and upper secondary school students generally repeat only courses that they have failed, not whole grades, while primary students are typically not made to repeat grades.

The share of repeaters varies to a large extent by country and by educational level. It reaches 2% in lower secondary general programmes and increases with higher levels of education. Grade repetition is relatively uncommon in lower secondary general programmes and is below 5% in most countries. However, the share of repeaters exceeds 5% in Belgium, Portugal and Spain (Figure B1.2). Grade repetition is more common in upper secondary education, especially in Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Portugal and Spain, where repeaters represent at least 7% of the enrolled students. The share of repeaters in upper secondary education is 3% on average across OECD countries, 1 percentage point higher than for lower secondary education.

1. Year of reference 2018.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of repeaters in lower secondary education.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2021), Education at a Glance Database. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

On average across OECD countries with available data, boys are more likely to repeat a grade in general programmes than girls and represent 61% of the number of repeaters in lower secondary education and 57% in upper secondary education (Figure B1.2). This is true for all OECD countries in lower secondary education and for all countries but Austria, Estonia and Italy in upper secondary education. In lower secondary programmes in Israel, Lithuania, Mexico and Turkey and in upper secondary programmes in Greece, Israel and Poland, two out of three repeaters are boys.

Participation of 20-24 year-olds in education

The transition from secondary to tertiary education is characterised by a drop in enrolment rates on average. The 20‑24 year‑old age group does not include any years of compulsory education (in contrast to ages 15-19) and is the one that most typically corresponds to the ages of enrolment in tertiary education in OECD countries. The average enrolment rate of 20‑24 year‑olds across OECD countries is about half that of 15-19 year-olds: only 41% of the population aged 20-24 is enrolled in education. Enrolment rates among 20-24 year-olds are the highest in Australia and Slovenia, where 55% or more are in education. In contrast, the enrolment rate is as low as 21% in Israel (partly related to the compulsory nature of military service at the age of 18) and 20% in Luxembourg (where studying abroad in neighbouring countries is relatively common; see Indicator B6). Enrolment levels increased by 4 percentage points between 2005 and 2019 on average across the OECD. Enrolment levels increased significantly in a number of countries, especially in Australia, Ireland, Spain and Switzerland, where the enrolment rate was at least 11 percentage points higher in 2019 than in 2005. At the other end of the spectrum, the largest drop in enrolment in the same period was observed in Finland and Iceland, where rates fell by 7 percentage points (Table B1.1).

Across OECD countries, 20-24 year-old students are most commonly enrolled in tertiary education, typically in long-cycle programmes, but not entirely. On average across OECD countries, 29% of the male population in this age group and 37% of their female peers are enrolled in tertiary education (Table B1.2). The gender gap in enrolment widens with this age group. Over all education levels combined, enrolment rates are 7 percentage points higher on average for 20‑24 year‑old women than for men of the same age group. The largest gap in this age group is found for Slovenia (20 percentage points) and the gap is at least 15 percentage points for Argentina, Israel and Poland (Figure B1.1). In contrast, in Luxembourg, Korea and Turkey, enrolment rates of 20-24 year-olds are higher for men than for women and this gap is the highest in Korea, at 13 percentage points.

Participation of adults aged 25 and older in education

Enrolment in education is less common among the older population, as students graduate and transition to the labour market: the OECD average enrolment rate in all levels of education reaches 16% among 25-29 year-olds. The highest enrolment rates among 25-29 year-olds are in Australia, Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Turkey, where more than 25% of the population in this age group is still in education. The largest drops in enrolment rates for 25-29 year-olds compared to 20‑24 year-olds occur in Korea and Slovenia, where the enrolment rate is more than 40 percentage points lower (Table B1.1).

As enrolment rates are lower above age 24, the gender gap also decreases and enrolment rates are only 1 percentage point higher for 25-29 year-old women on average. This gap reaches 9 percentage points in Iceland and Sweden and is negative (more men than women are enrolled) for a few countries, including Korea and Turkey, with at least 5 percentage points (Figure B1.1).

Enrolment levels are lower among 30-39-year-olds (OECD average: 6%) and reach at least 15% only in Australia, Finland, Sweden and Turkey. The OECD average enrolment rate for the population aged 40-64 is 2%, with the highest enrolment rate observed in Australia (7%) (Table B1.1).

Subnational variations in enrolment

Subnational variation in enrolment patterns reveals the equality of access to education across a country, as well as labour-market opportunities and perceptions on lifelong learning for levels beyond compulsory education or tertiary education. While enrolment between the ages 6 and 14 is rather homogenous across regions, enrolment rates for 15-19 year-olds vary to some extent within countries. In more than half of the countries with data available, the variation of the enrolment rate between subnational regions is larger than the variation of national values across different OECD countries. The range of enrolment rates is widest in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Korea with a difference of at least 33 percentage points between the highest and lowest enrolment rate of 15-19 year-olds across subnational regions. In Chile, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, the range of enrolment rates for this age group is relatively small with a difference of 7 percentage points or less within countries (Figure B1.3).

Figure B1.3. Regional variation of the enrolment rate of 15-19 year-olds (2019)

Enrolment rates in all levels of education combined, in per cent

Note: National averages are presented under the OECD label.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the range between the maximum and minimum enrolment rate.

Source: OECD (2021), Regional Statistics Database. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Definitions

The data in this indicator cover formal education programmes that represent at least the equivalent of one semester (or half of a school/academic year) of full-time study and take place entirely in educational institutions or are delivered as combined school- and work-based programmes.

Full enrolment, for the purposes of this indicator, is defined as enrolment rates exceeding 90%.

General education programmes are designed to develop learners’ general knowledge, skills and competencies, often to prepare them for other general or vocational education programmes at the same or a higher education level. General education does not prepare people for employment in a particular occupation, trade, or class of occupations or trades.

Vocational education and training (VET) programmes prepare participants for direct entry into specific occupations without further training. Successful completion of such programmes leads to a vocational or technical qualification that is relevant to the labour market.

A full-time student is someone who is enrolled in an education programme whose intended study load amounts to at least 75% of the normal full-time annual study load. A part-time student is someone who is enrolled in an education programme whose intended study load is less than 75% of the normal full-time annual study load.

Methodology

Except where otherwise noted, figures are based on head counts, because of the difficulty for some countries to quantify part‑time study. Net enrolment rates are calculated by dividing the number of students of a particular age group enrolled in all levels of education by the size of the population of that age group. While enrolment and population figures refer to the same period in most cases, mismatches may occur due to data availability in some countries, resulting in enrolment rates exceeding 100%.

For more information, please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018 (OECD, 2018[5]) and Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Source

Data refer to the 2018/19 academic year and are based on the UNESCO-UIS/OECD/Eurostat data collection on education statistics administered by the OECD in 2020 (for details, see Annex 3 at: https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Data on subnational regions for selected indicators are available in the OECD Regional Statistics (database) (OECD, 2021[6]).

References

[4] Fruehwirth, J., S. Navarro and Y. Takahashi (2016), “How the timing of grade retention affects outcomes: Identification and estimation of time-varying treatment effects”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 34/4, pp. 979-1021, http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/686262.

[6] OECD (2021), “Regional education”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/213e806c-en (accessed on 25 June 2021).

[3] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

[1] OECD (2019), “What characterises upper secondary vocational education and training?”, Education Indicators in Focus, No. 68, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a1a7e2f1-en.

[5] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[2] UNESCO International Bureau of Education (1970), Educational Trends in 1970: An International Survey, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Paris, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000000673 (accessed on 9 June 2021).

Indicator B1 tables

Tables Indicator B1. Who participates in education?

|

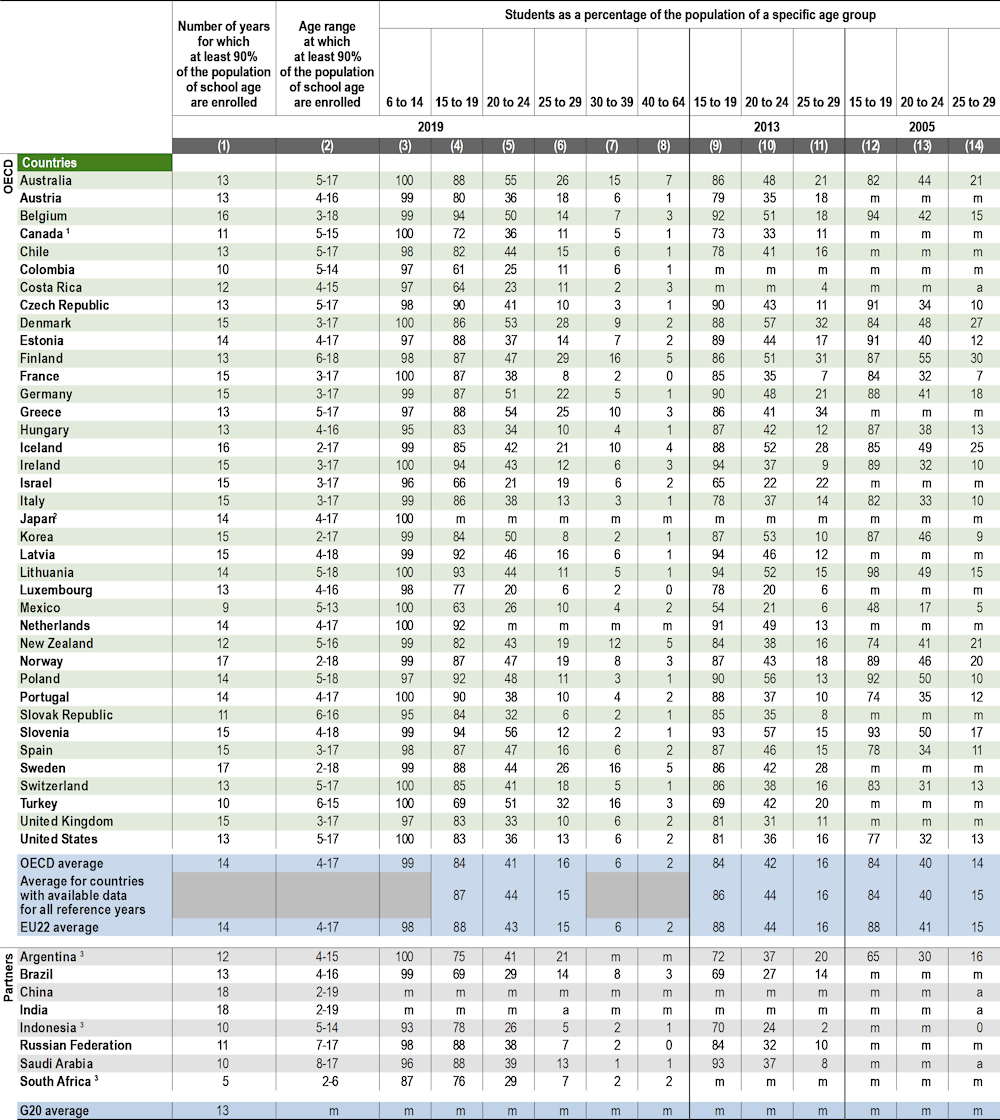

Table B1.1 |

Enrolment rates by age group (2005, 2013 and 2019) |

|

Table B1.2 |

Enrolment rates of 15-19, 20-24 and 25-29 year-olds by gender and level of education (2019) |

|

Table B1.3 |

Enrolment rates from age 15 to 20 by level of education (2013 and 2019) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2021. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table B1.1. Enrolment rates by age group (2005, 2013 and 2019)

Students in full-time and part-time programmes in both public and private institutions

1. Excludes post-secondary non-tertiary education.

2. Breakdown by age not available after 15 years old.

3. Year of reference 2018.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

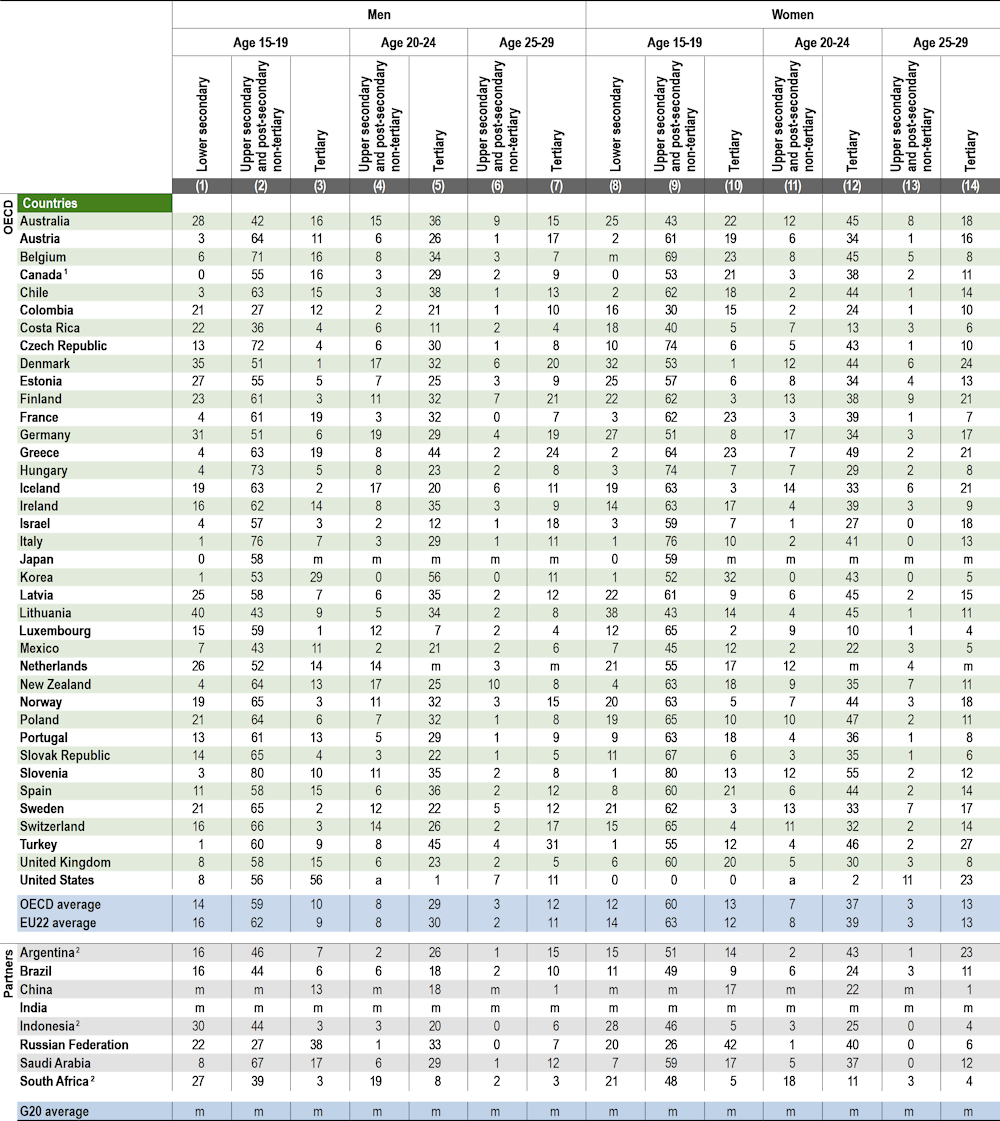

Table B1.2. Enrolment rates of 15-19, 20-24 and 25-29 year-olds by gender and level of education (2019)

Students enrolled in full-time and part-time programmes in both public and private institutions

1. Excludes post-secondary non-tertiary education.

2. Year of reference 2018.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

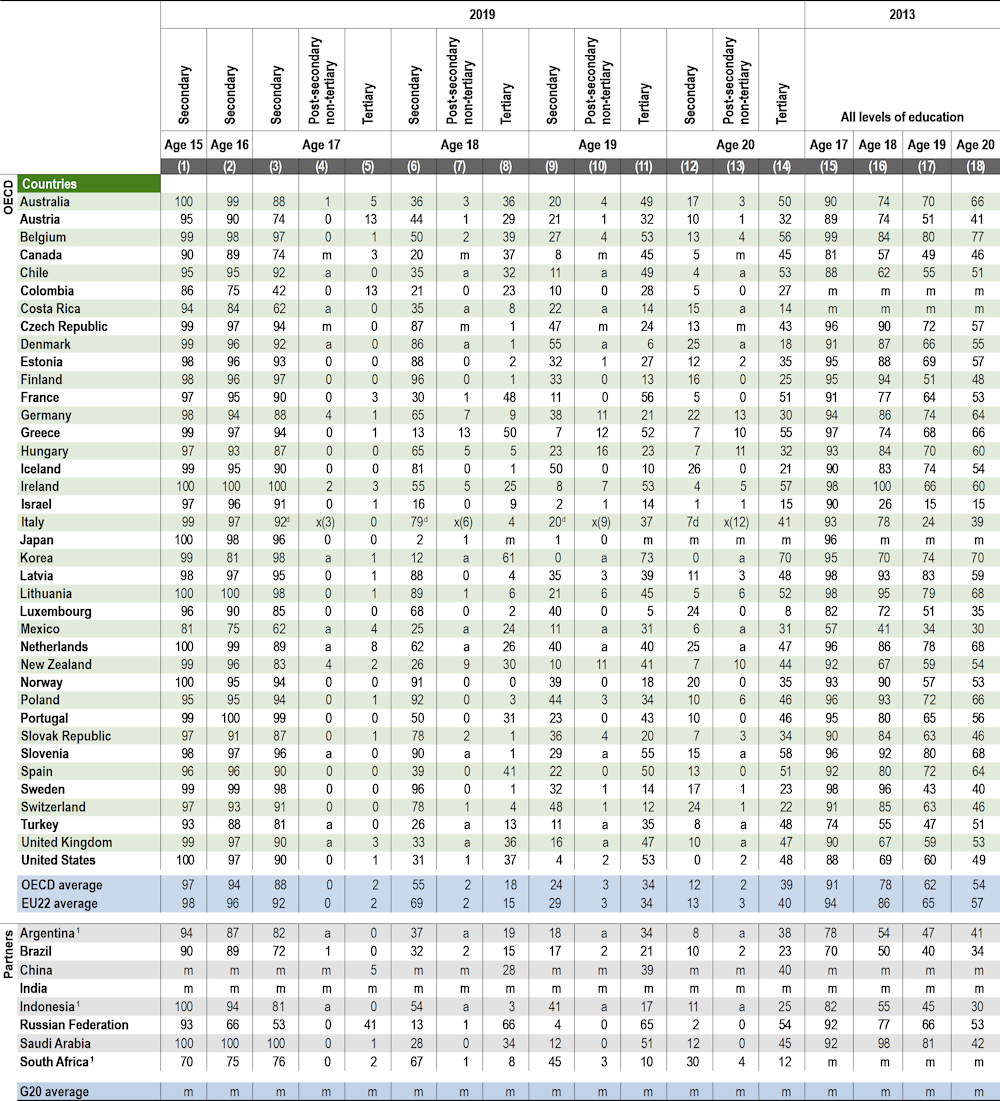

Table B1.3. Enrolment rates from age 15 to 20 by level of education (2013 and 2019)

Students enrolled in full-time and part-time programmes in both public and private institutions

1. Year of reference 2018.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterB.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.