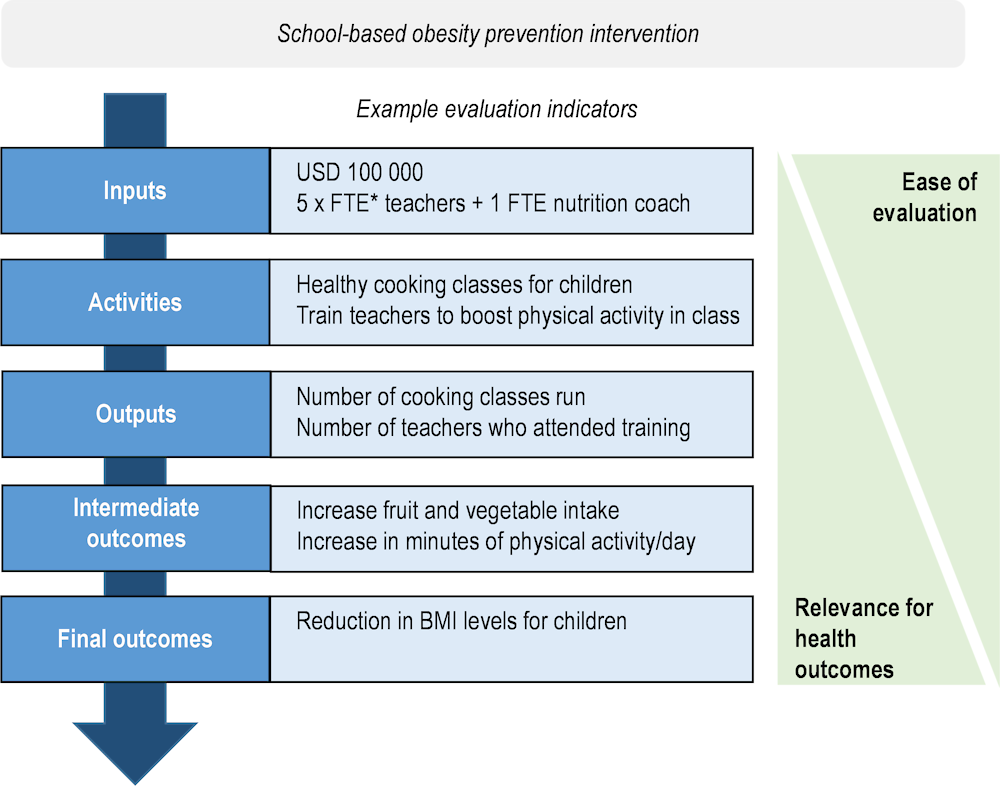

Once the programme logic is developed, indicators for each element within the logic model should be specified (see Table 3.1 for a high-level overview and Figure 3.3 for an example). When choosing indicators, it is important to be realistic by considering the data and resources available.

Inputs: the starting point of an evaluation is the inputs. Input indicators should cover items such as funding (financial resources); personnel required to deliver the intervention (e.g. in FTE); capital infrastructure (e.g. meetings rooms, exercise equipment, community kitchens); other materials and supplies; and in-kind resources. This information is important to put the outcomes in perspective in terms of return on investment of time and money.

Activities: activity indicators reflect the essential activities required to produce intervention outputs (i.e. what to do with intervention inputs). Example activity indicators include training for teachers to deliver obesity prevention curricula; healthy lifestyle workshops for parents and children; and developing advertising material to promote physical activity.

Outputs: output indicators reflect the products/goods/services produced from the intervention’s activities. Using the examples provided under “Activities”, aligning output indicators include: the number of teachers who received training; the number of healthy lifestyle workshops run; and the number of social media ads promoting physical activity. Output indicators, therefore, help measure how well the intervention was implemented. Without this information, it is possible, for example, to assume erroneously that an intervention has no impact, while in reality the intervention did not actually reach participants.

Outcomes: outcome indicators measure whether the intervention has achieved (or is on the path to achieving) its objectives and align with “effectiveness” indicators used in Step 1a of the guidebook. Outcomes can be broken into two categories – final and intermediate. Final outcomes reflect the ultimate objective of policy makers, and, in the field of public health typically refer to changes in population health (for example, a reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD)). Final outcomes, however, can be difficult to measure and can take many years to achieve. For this reason, intermediate outcomes (often referred to as short- and medium-term outcomes) directly related to the final outcome can be measured. Using CVD prevalence as an example, intermediate outcomes of interest may include a reduction in salt intake and improved knowledge on the importance of a healthy diet. Nevertheless, it is important to carefully consider this causal pathway. For example, a reduced calorie intake will only decrease body-mass index if all else stays equal. In reality physical activity may also decline, which could negate the impact on BMI. In this case, it would be useful to also measure any changes in physical activity.

Generally, indicators at the beginning of the logic model are easier to measure, while indicators at the end of the logic model are more relevant to the health impact of the intervention but more difficult to measure.