Interventions to prevent or manage key public health issues are complex. As discussed in Step 1b (Section 1.3), they involve several interacting components, often target heterogeneous populations and interact with their context. They are usually delivered by people who are part of established health or social care organisations and they may be supported by technical tools, including information and communications technology. Crucially, to achieve their desired effects on relevant health outcomes, they often aim to create an interplay between their individual components to change the behaviour of health and social care providers and enhance the delivery of services, to inform the population or patient group targeted, and, ultimately, change the behaviour of citizens and patients. While research is constantly identifying many possible ways of improving population health, for instance through changing living environments and personal behaviours, these changes do not usually occur automatically to benefit populations. Many advances are not put into practice adequately, often because the will, or skill, to change behaviour are missing (Jenkins, 2003[96]).

Because such interventions rely on the interactions of many people, tools and processes, they only succeed if these interactions are co‑ordinated through careful implementation. While appropriate selection and adaptation of interventions (as discussed in Step 1a (Section 1.2) and Step 1b (Section 1.3) are prerequisites for achieving intended outcomes, these steps on their own are insufficient to ensure success. Even an appropriate and well-designed intervention can fail if it is poorly implemented. Many studies have shown that factors related to implementation affect the outcomes achieved by health promotion and prevention interventions (see, for instance, Durlak and DuPre (2008[97]) or Nielsen (2015[98])).

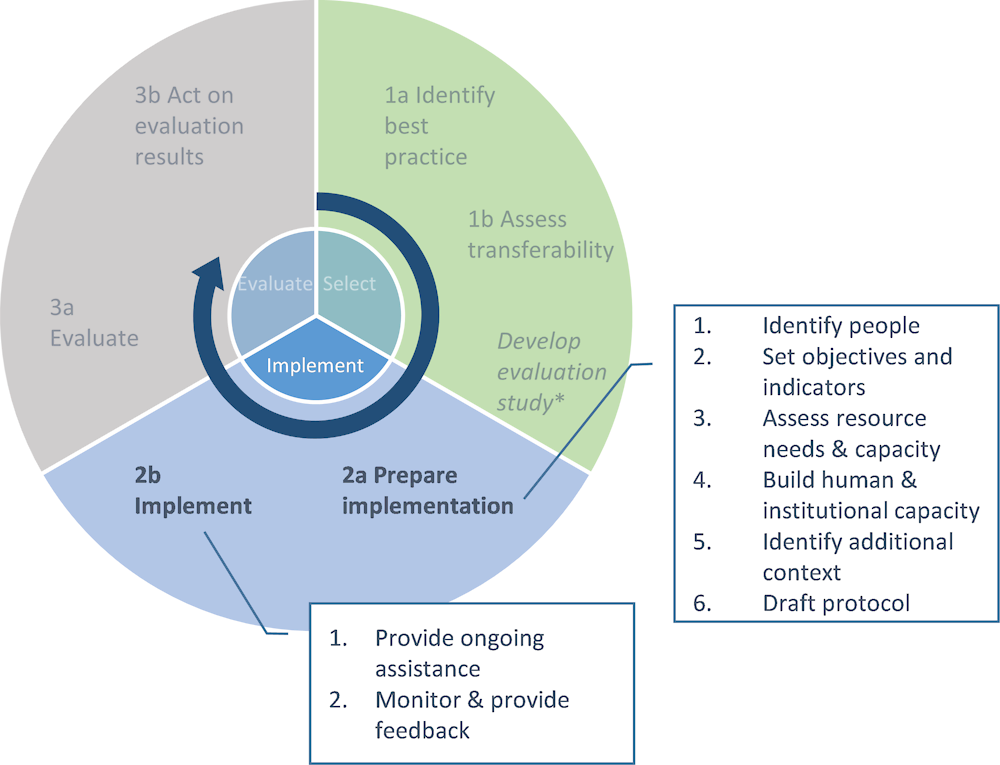

For the purpose of this guidebook, implementation generally refers to “the process of putting to use or integrating evidence‑based interventions within a setting” (Brownson et al., 2015, p. 305[99]). Specifically, this section guides policy makers in ensuring that interventions identified as best practice (Step 1a, Section 1.2) and suitable for transfer (Step 1b, Section 1.3) are implemented in a specified target setting. In other words, it helps ensure that the protocols and standards defined in the intervention are effectively applied in practice.

Beyond increasing the chances that new interventions achieve their desired outcomes, implementation is important for at least two other reasons. First, policy makers need to understand how an intervention was implemented to correctly interpret its effects in terms of outcomes measured. Even if a quantitative evaluation of an intervention shows that it is effective in terms of relevant health outcomes observed, policy makers can only understand causality if they know which components of the planned intervention were actually delivered and how well this was done. Again, an observed failure could result from poor implementation while success could be due to an intervention that, in practice, was very different from what was intended (Durlak and DuPre, 2008[97]). As discussed further below and in the section on preparing implementation and in Step 3 (Evaluate), an evaluation of the intervention should therefore also include implementation-related indicators. Second, an understanding of the process of implementation, and in particular the factors that contributed to success or failure of initial implementation of a new intervention, is necessary to understand whether an intervention has to be adapted further. A problem related to implementation is that interventions, even if successful in an initial test or pilot phase, are often not sustained over time and therefore fail to deliver their potential in the longer term (ibid.).