Falilou Fall

OECD

OECD Economic Surveys: South Africa 2022

2. Strengthening the tax system to reduce inequalities and increase revenues

Abstract

The Covid-19 crisis has exacerbated the already deteriorating fiscal situation in South Africa. The current consolidation strategy, based on spending cuts and reprioritisation of spending items, has reached its limits and is insufficient to stabilise the debt ratio in the medium term and fund unmet public services needs. The tax-benefit system needs to be redesigned to create fiscal space in the years to come to finance growth-enhancing reforms and to reduce inequalities. The challenge is to generate additional revenues without generating inefficiencies or exacerbating inequality. Income taxes represent around half of total tax revenues, but are levied on small tax bases, partly reflecting the unequal distribution of income. Only the value-added tax has a relatively broad basis combined with a moderate tax rate. There is some scope to raise revenues further while reducing existing tax distortions, notably by broadening the base of corporate and personal income taxes, as well as consumption taxes. Taxes with a less harmful impact on growth, such as property taxes, are limited by the inefficient municipal rates system. There remains scope to further increase environmentally-related taxes.

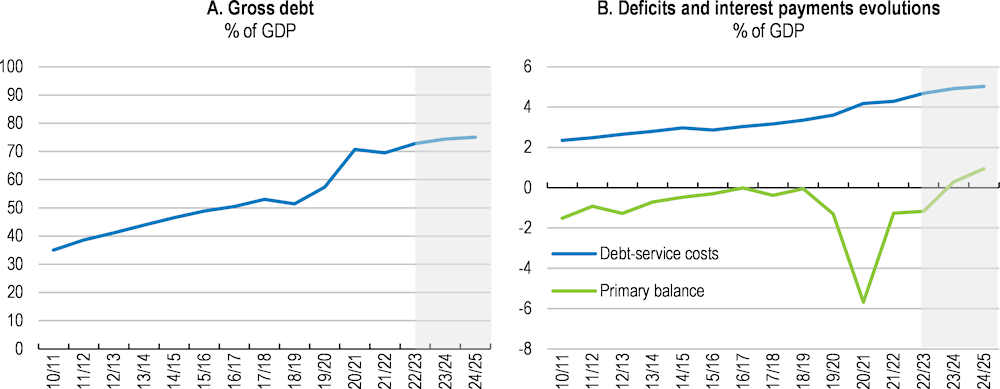

South Africa’s debt trajectory will not be sustainable without higher growth, limited increases of spending and higher revenues for the government. Gross debt rose steadily over the last decade and accelerated during the crisis (Figure 2.1, Panel A). Debt service costs continued to increase as a consequence both of growing debt-to-GDP and rising interest costs (Figure 2.1, Panel B). Even a primary surplus of 1% of GDP over the next ten years would not stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio, given low growth prospects and expected borrowing interest rate levels (chapter 1).

Spending pressures remain high, notably for infrastructure projects and the planned national health insurance scheme and social transfers for unemployed individuals. To enhance fiscal sustainability, the National Treasury’s strategy focuses on improving spending efficiency by reducing waste and corruption. This strategy is a step in the right direction. Tangible improvements in public sector spending efficiency might contribute to raising compliance levels and make tax changes more socially acceptable. Nonetheless, additional measures are needed to create the required fiscal space to finance growth-enhancing reforms. This chapter explores potential directions for a tax reform that would simultaneously raise the effectiveness of tax collection, while reducing income inequality and existing growth distortions in the tax system.

Figure 2.1. The budget situation has worsened

The challenges of a tax reform

Tax revenues remain stable but are slightly tilted toward direct taxes

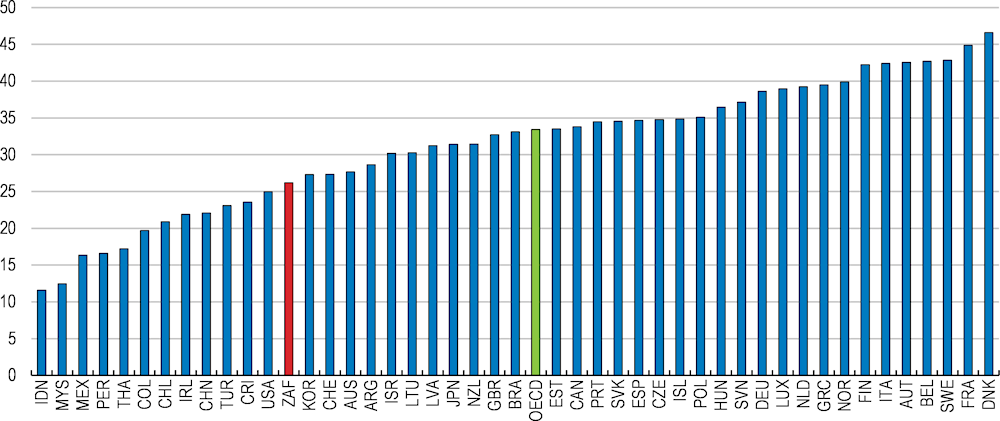

Government revenues, at 26% of GDP in 2019, are lower than the OECD average, but higher than most emerging market countries (Figure 2.2). Like for many other countries, government revenues fell sharply in the fiscal year 2020/21 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The boom in commodity prices is temporarily boosting fiscal revenues and creating fiscal space to finance spending related to the pandemic among other priorities.

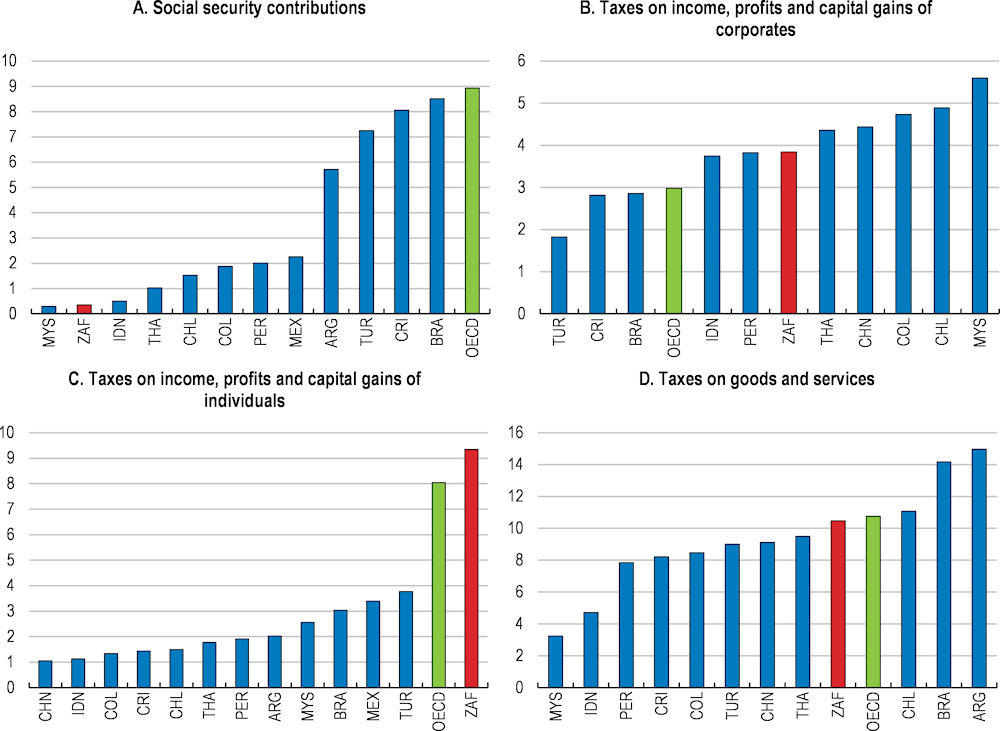

Taxation is relatively balanced between direct and indirect taxes. Direct taxation of individuals and firms represents 60% of government revenues. However, social security contributions and payroll-based contributions are low: government health care spending and social transfers are financed out of the national budget and only a 2% contribution rate is levied on wages for unemployment insurance (Figure 2.3). Taxes influence economic agent’s decisions. For households, the tax system influences work, consumption, and savings. For firms, it changes the relative cost of labour and capital. This has an impact on hiring, investment, innovation and profit distribution decisions of firms. South Africa may consider rebalancing its taxation structure toward more indirect taxation (consumption and property taxes) as they appear broader and less harmful to employment than direct taxes.

Figure 2.2. The Tax-to-GDP ratio is below the OECD average but higher than in most other emerging countries

Government revenue as a % of GDP, 2019

Figure 2.3. The tax structure is tilted toward direct taxation

% of GDP, 2019

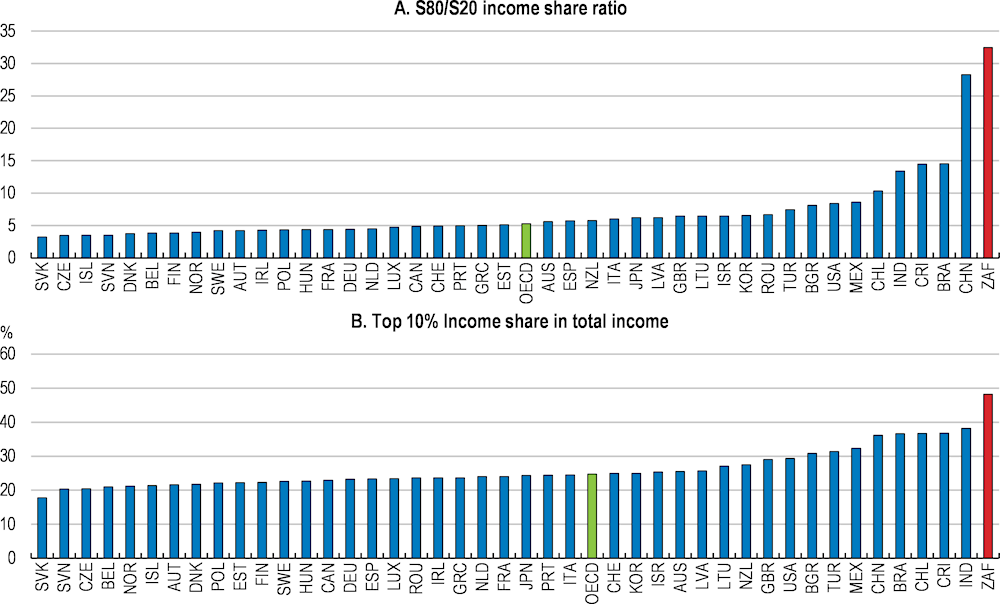

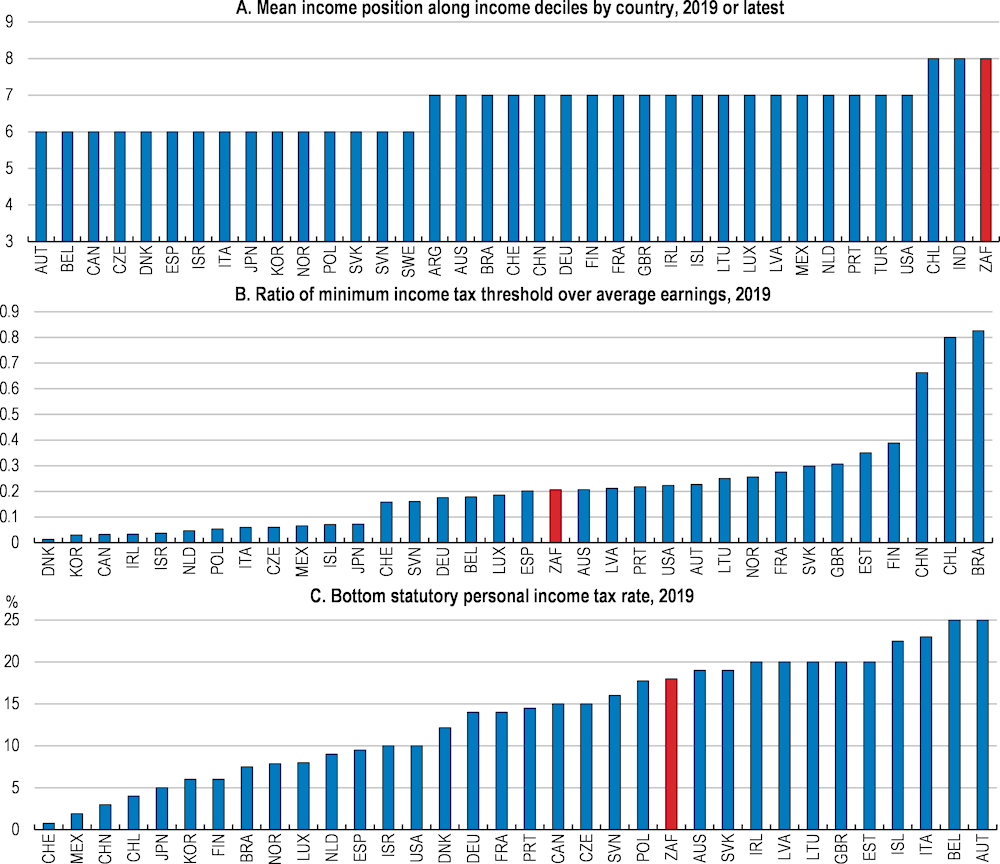

South Africa has one of the highest levels of inequality in the world (Figure 2.4). The low labour market participation rate of 54% implies that large parts of the working age population are not earning any market income. Moreover, almost half of workers earn around the national minimum wage, while a small minority benefits from very high incomes. This income distribution profile makes it difficult to set up a personal income tax rate schedule that reduces income inequalities significantly without resorting to very high marginal tax rates.

Figure 2.4. Income inequality remains the highest in South Africa after tax and transfers

Note: 2019 or latest. Data refer to the total population and are based on equalised household disposable income, i.e. income after taxes and transfers adjusted for household size. The S80/S20 income share ratio refers to the ratio of average income of the top 20% to the average income of the bottom 20% of the income distribution.

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database

Designing tax policy reform

The challenge in designing an optimal tax system is to raise tax revenues while minimising its growth distortion and addressing market imperfections and social concerns, including inequality and climate change. Research across OECD countries shows that most taxes dent short-term activity but have different effects on long-term activity and on equity (Arnold et al., 2011; Cournède et al., 2013; Joumard et al., 2012).

The optimal personal income tax should be progressive to balance equity and efficiency concerns in the presence of asymmetric information (Mirrlees, 1971; Diamond, 1998; and Saez, 2001). However, in South Africa, the capacity of the personal income tax rate schedule to reduce inequalities is affected by the high degree of inequality in the pre-tax income distribution. Reforming the personal income tax has to strike a balance between strongly reducing inequalities and preserving work incentives for middle to high-income earners. As analysed in the following sections, there is room to increase the effectiveness and progressivity of the personal income tax schedule. Bases can be broadened by reducing allowances, deductions, credits and exemptions that are very generous. Such reforms may also increase horizontal equity across taxpayers, reduce distortions and lower administrative costs.

In addition to a standard corporate tax with a rate of 28% (the government plans to reduce it to 27%), South Africa has two business tax regimes targeted at small businesses: a microbusiness regime (with low rates on turn over) and a small business corporations’ tax (with a progressive tax rate schedule). These regimes are reviewed in the following sections and ways to improve their effectiveness are analysed, in particular, as part of a reform that aims at reducing the corporate income tax rate by broadening the tax base.

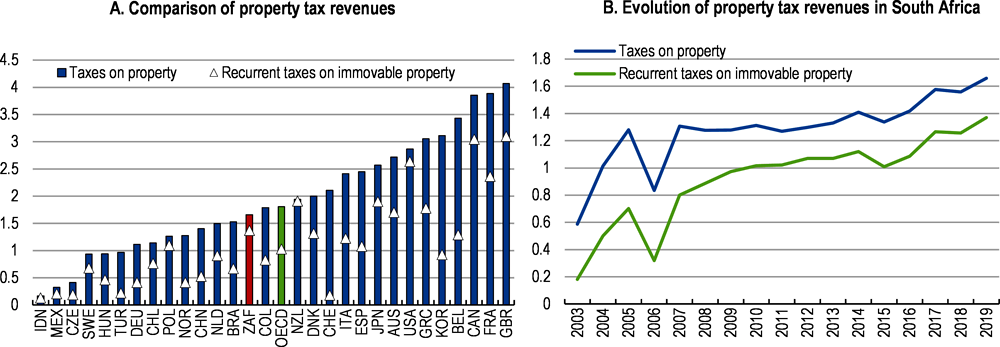

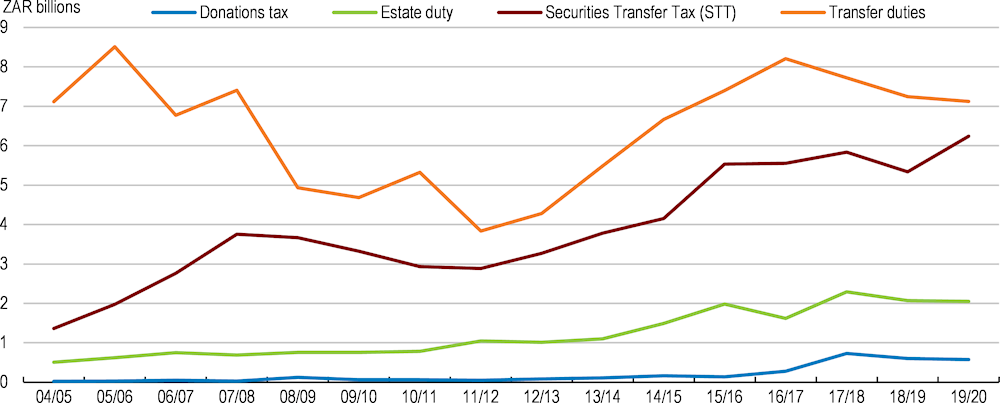

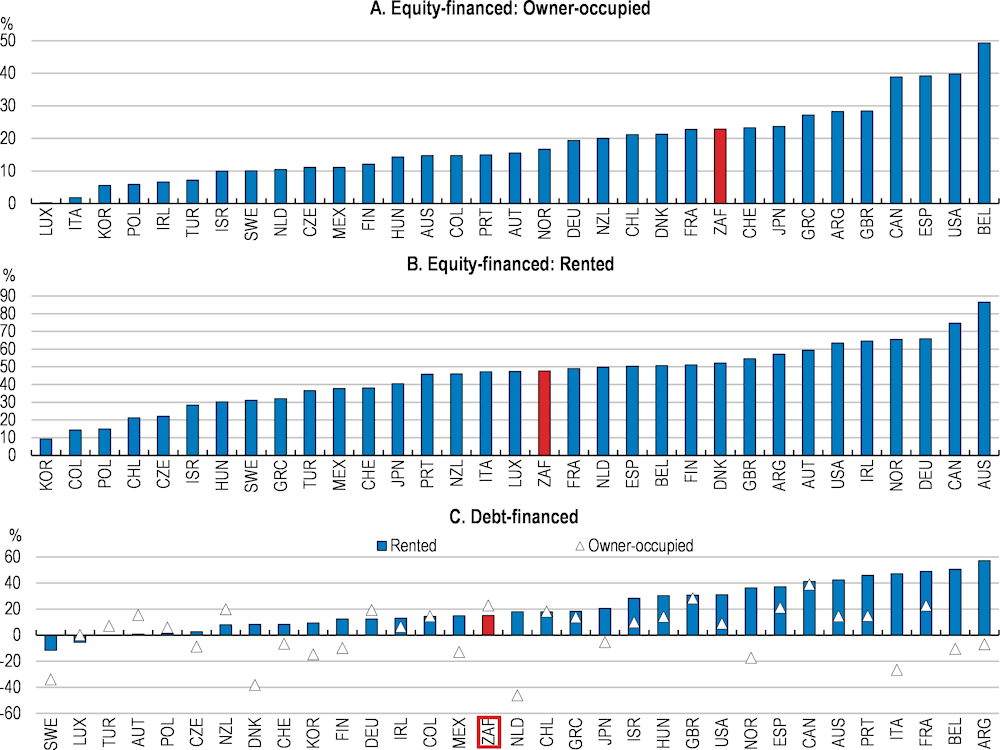

Consumption taxes are more growth-friendly in the long-term but can have short-term effects on inequality that should be offset in other ways. There is also room to increase consumption tax rates, compensated by grant transfers toward low-income households. Recurrent taxes on immovable property are also theoretically more growth-friendly and, depending on their design, can be equity-enhancing. Property taxes are mostly set by local governments in South Africa. Property taxes remain limited, while wealth inequality is the highest in the world. Wealth taxation could be increased by broadening the tax basis and increasing the taxation of donations and estate duties. Finally, gradually increasing the carbon tax rate and broadening its base would reduce the carbon intensity of the economy.

The following sections identify ways to make the tax system less distortive, increase government revenues directly but also indirectly through higher growth and reduce inequalities. Overall, priority should be given to reforms that broaden tax bases, as a more growth-oriented way of raising tax revenues than increasing tax rates (OECD, 2010).

Broadening the personal income tax base would improve its progressivity

The base of the personal income tax system is narrow

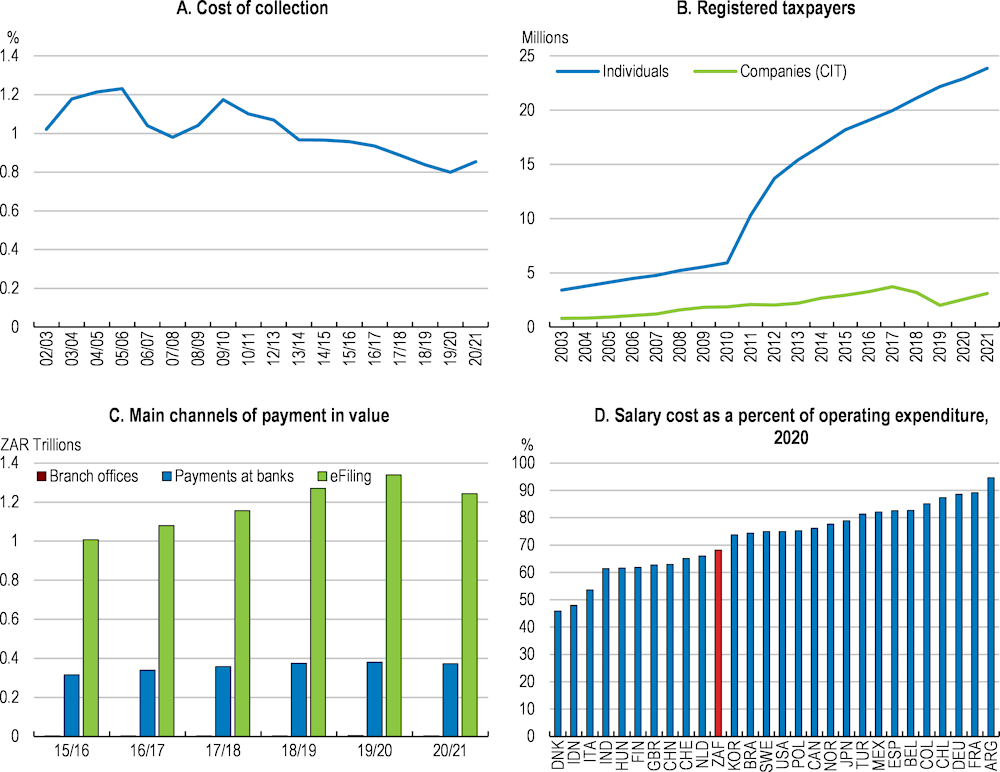

Taxes on personal income are the most important source of revenue. South Africa has been more successful than many other middle-income countries in covering its population by the tax system. This is explained by an efficient registration system, with a long history. Still, only about 52% percent of the working-age population is registered, which is a consequence of the low labour force participation rate of 54% (see KPI Chapter). Informality of firms and of workers also reduces tax bases; informal employment, at 32%, although high, is generally considered to be small relative to other emerging economies (ILO, 2018).

The personal income tax base is narrow. In 2020, the number of taxpayers was 5.2 million compared to 11.3 million employees in the formal sector. Different factors contribute to this narrow tax base. Half of workers are earning below or around the minimum wage and, therefore, their revenue is below the minimum tax threshold. Also, the minimum tax threshold is relatively high; it corresponds to about 20% of average earnings in 2019, which is around the OECD average (Figure 2.5, Panel A). It is, however, high for South Africa, as the average income is high, positioned at the 8th decile of the income distribution, due to a highly skewed wage income distribution.

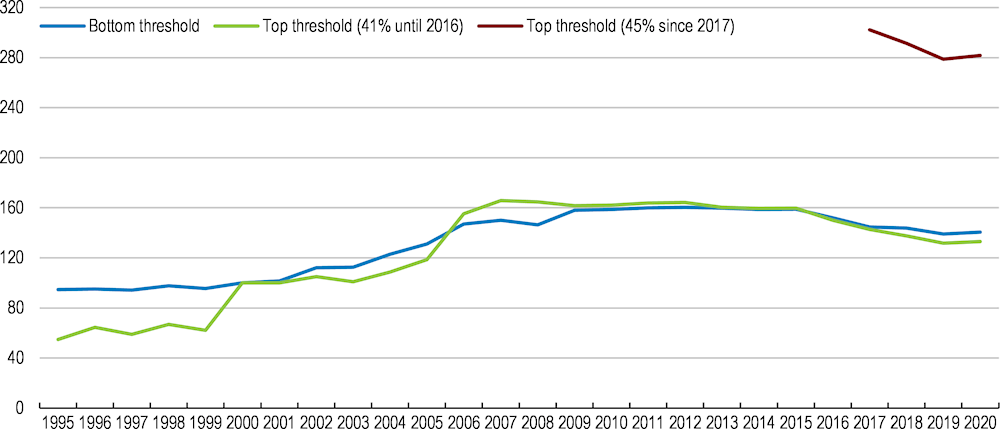

The minimum income tax threshold decreased in real terms recently as it has been uprated below inflation between 2016 and 2020, which increased the number of taxpayers (Figure 2.6). As the top marginal rate was increased from 41% to 45%, options could be considered to broaden the tax base from below as an integral part of a reform that broadens the tax base for higher income earners. Slightly lowering the minimum income tax threshold would include some individuals earning between the minimum wage and the current income tax threshold. (Figure 2.5, Panel C).

Moreover, the taxation, under different regimes, of certain capital incomes affects the personal income tax base. Types of income taxable under the personal income tax include mainly all types of income from employment such as wages, bonuses, overtime pay, taxable benefits (fringe benefits) and allowances, representing around 78% of taxable income in 2019. Also, certain categories of revenues as income from a business (trade, profits arising from a trust beneficiary; etc.), investment income (capital gains, interest, foreign dividends, rental income, etc.) and retirement income (annuities, pensions) are taxed under the personal income tax.

A significant share of realised capital gains is not included in the personal income tax base. Starting from October 2001, taxable capital gains are determined by deducing an annual exclusion amount of ZAR 40 000 and by applying after the deduction a 40% inclusion rate. While these tax provisions take into account the impact of inflation on asset values and the fact that the return on equity has been taxed already by the corporate income tax, the tax exemption seems large, and scope might exist to reduce it somewhat.

Except certain foreign dividends not covered by various exemptions, dividends are excluded from personal income tax, but are taxed at 20% since 2017. The dividends tax was introduced in 2012 at a rate of 15% to replace the Secondary tax on companies of 10%, which was also a tax on dividends but borne by the company. The dividends tax is a withholding tax paid by the company or the regulated intermediary. The effective tax burden on dividends, when considering the standard corporate income tax rate and the dividend tax rate, is 42.4 per cent, which is below the top PIT rate. Scope therefore exists to somewhat increase the dividend tax rate.

Interest received by an individual is taxable personal income. However, an exemption applies to the first ZAR 23,800 of local interest income (ZAR 34,500 for taxpayers who are 65 years of age or older). In 2019 almost 339 000 individual taxpayers earned local interest income that exceeded the interest exemption limit, amounting to an increase in taxable personal income of ZAR 28.9 billion (2% of total taxable income assessed; SARS, 2021).

Figure 2.5. The minimum income tax threshold is high as the mean income is high

Source: OECD Income Distribution Database; OECD Taxing Wages 2020; OECD Tax Database; South Africa Revenue Service; KPMG and Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica - IBGE; National Bureau of Statistics of China; OECD calculations.

Figure 2.6. Tax thresholds have been lowered in real terms

Tax thresholds in real terms, index 2000 = 100

Note: Thresholds are deflated by the CPI for urban areas. Data are for personal income tax years, which begin on 1 March of year shown. The top marginal income tax rate had been 40-41% between 1 March 2014 and 28 February 2017. Since 1 March 2017, in addition to the 41% tax rate, the top marginal income tax rate was redefined to be 45%. Its taxable income threshold in real terms is presented in a separate line, and is benchmarked against the top threshold in 2000.

Source: National Treasury and South African Revenue Service Tax Statistics; OECD Consumer price indices - Complete database; OECD calculations.

Increasing the progressivity of the personal income tax schedule to reduce income inequalities

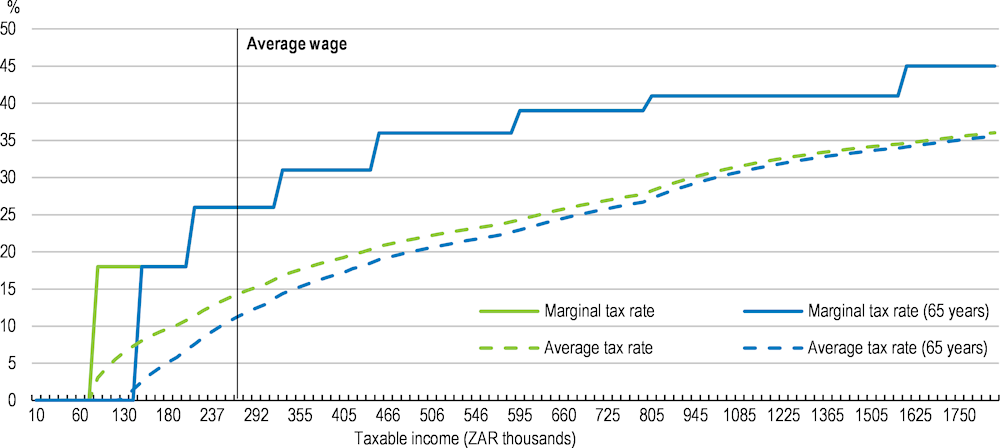

Successive reforms over the last two decades have simplified the tax structure, reduced the number of tax brackets, and broadened the tax base by taxing fringe benefits and capital gains. In 2019/20, all tax thresholds have been frozen to increase government revenues. In 2017/18, an additional bracket with a marginal tax rate at 45% for revenues above ZAR 1.5 million was introduced, further reinforcing the progressivity of the tax rate schedule.

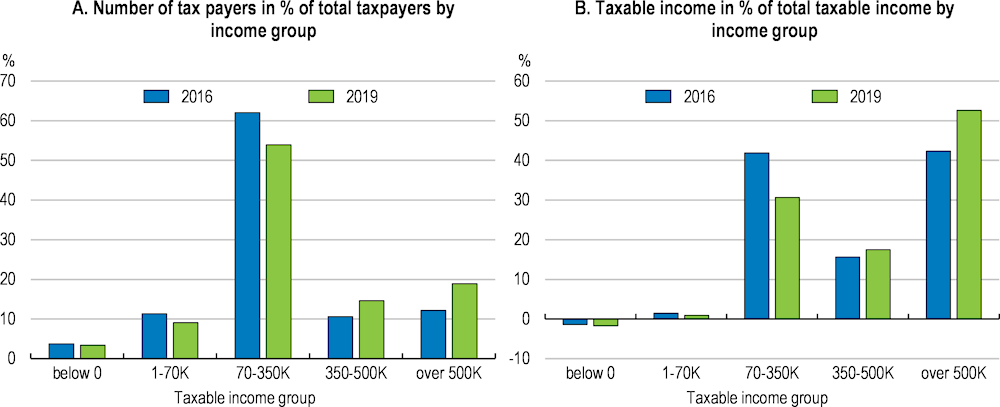

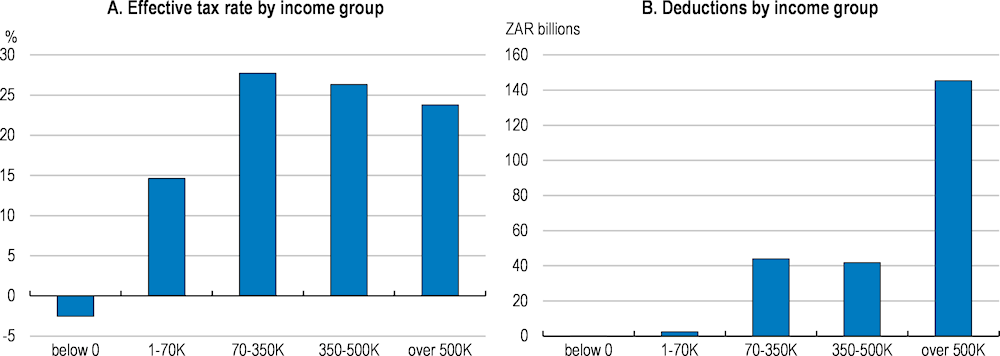

The design of the tax schedule is progressive. The combination of a basic tax allowance and increasing marginal tax rates ensures that the average statutory tax rate rises with income (Figure 2.7Figure ). The personal income tax system raises a much higher share of revenues from the richest households than in other emerging economies (World Bank, 2014). However, the revenue-raising capacity of the tax schedule is limited by the highly unequal income distribution and, in particular, because a large share of taxpayers earns little income. The taxable income of the top 20% of income earners represented more than 50% of total taxable income in 2019 (Figure 2.8Figure ). Therefore, the after-tax income inequality remains high as a result of the skewed market income distribution.

Tax allowances and deductions reduce the effective tax rate and undermine the progressivity of the tax schedule as higher income-earners end up facing lower effective tax rates than middle-income earners (Figure 2.9, Panel A). Tax allowances comprise travel and subsistence allowances, share options exercised and allowances covering savings and equity instruments (other allowances). The travel allowance is the biggest tax allowance, representing 26% of allowances in 2019, and 80% of the travel allowance is tax deductible. Tax allowances represent 21% of collected personal income tax in 2019 and about 7% of taxable income. Fringe benefits as the acquisition of asset at less than the actual value, right of use of motor vehicle, free or cheap residential accommodation, and medical aid paid on behalf of employee and pension and provident fund, among others, are benefits for employees born by the employer. While fringe benefits are included in the PIT base, they are often undervalued for tax purposes. Scope exists to increase the value that is included within the PIT base of the fringe benefits the individual has received.

Deductions represented around 12% of personal taxable income and 41% of personal income tax collected in 2019. Deductions for retirement savings, 85% of total deductions, explain the biggest share. The 2016 reform of incentives for retirement savings harmonised the tax treatment of different saving schemes and introduced a nominal cap on tax-deductible contributions (ZAR 350 000), thereby reducing tax-planning opportunities that disproportionally benefited high-income earners. Nonetheless, such deductions continue to mostly benefit middle- and high-income earners (Figure 2.9). While having levelled the playing field, the introduction of an annual cap on deductible contributions (the lowest value between ZAR 350 000 and 27.5% of the highest between remuneration and taxable income) has increased the amount of deductions that many taxpayers can benefit from. Provident fund members benefit from a tax deduction on contributions made to their provident fund and see an increase in their take-home pay as they now receive a tax deduction for their contributions. All in all, the reform has increased pension contribution deductions. The amount of deductions awarded for pension savings vehicles should be revised when some of those savings are withdrawn before retirement as such savings will not support pension anymore. These early withdrawals could be partly or entirely subject to a tax in line with other personal income. Moreover, taxpayers aged over 65 and 75 years receive additional tax relief in particular a secondary and tertiary rebate on income tax. This tax relief for pensioners is redundant with the tax deductions for pension savings. Also, it breaks the fairness of the tax system between workers and aged taxpayers and will have a growing fiscal cost as population ages. The tax relief for pensioners should therefore be phased out.

Figure 2.7. The personal income tax schedule is progressive

Figure 2.8. The tax base reflects the highly unequal income distribution

Medical tax deductions (around ZAR 40 billion) are large and reduce the progressivity of the tax schedule. Medical tax credit rebates alone amounted to around ZAR 24 billion in 2019. These medical tax credits increase incentives to purchase private medical insurance. South Africa spends around 8.1% of GDP on health, half from the public sector and the other half from the private health sector, which covers only 16% of the population. The government intends to roll out progressively a national health insurance (NHI) system, offering a large basket of health benefits including primary care, emergency and hospital-based services. As the national health insurance system is deployed, the medical tax credit rebates and deductions could be reduced progressively to finance the NHI (OECD Economic Survey, 2020a). Reducing tax deductions and allowances and taxing fringe benefits more adequately would restore the progressivity of the PIT system and contribute to inequality reduction.

Figure 2.9. Tax deductions benefit mostly high-income earners

Taxable income in 2019

Note: The 350-500K category is likely biased as it bundles two income tax brackets with different PIT rate. The data do not allow to separate them.

Source: South African Revenue Service, Tax Statistics, 2021; OECD calculations.

Income tax, transfers, and participation to the labour market

Taxes levied on payroll are relatively low and are not a major barrier to job creation. Contributions to the unemployment insurance and the skill development fund are the only direct social contributions on wages. The unemployment insurance contribution rate is 2% of wages, equally paid by the employee and the employer. Contributions to the unemployment insurance are subject to a maximum earnings ceiling, which was ZAR 17 712 per month in 2021 (around 5 times the minimum wage). A skill development levy on payroll and wage benefits is imposed, collecting 1% of the total amount paid in salaries to employees (including overtime payments, leave pay, bonuses, commissions and lump-sum payments). The revenues from the skill development levy serve to encourage learning and development. Therefore, income taxes on wages are the only other direct tax for wage earners. South Africa’s tax wedge is relatively low, and this is likely to be a minor barrier to job creation, at least for the household types considered in the analysis below (see Table 2.1).

The social transfer system is broad and well-functioning (OECD South Africa Economic survey 2020a). Around 18.2 million out of 57 million South Africans now receive social grants – the majority of which are for children and the elderly. Unemployed working age people are not covered by the social assistance system, while mothers of children receive a relatively low child support (ZAR 450) when compared to the national minimum wage (around ZAR 3 800 per month in 2021). Such level of transfer is not likely to be a direct barrier to labour force participation, although the low amount might prevent parents from paying for childcare and thus, indirectly, may prevent parents and in particular women from entering the labour market. Transport costs are a higher barrier to employment than the lower labour market participation risk some associated with social transfers (Chapter 1).

The tax schedule is probably not a major barrier to labour force participation either. The gap between formal employment earnings and social assistance benefits is huge, in particular for earnings above the average income level. Therefore, increasing marginal income taxes above the average wage should not affect labour participation significantly. To increase labour participation, an in-work tax credit for low-income earners could be considered as a complement to the current wage subsidy that mainly targets youth employment. A tax credit should particularly benefit low-skilled workers and would also reduce rates of in-work poverty, as seen in other countries with highly unequal income distributions, such as the United States. However, an in-work tax credit would not address the labour demand dimension. But it could also encourage informal workers to move into the formal sector and help to offset the high costs of commuting faced by many low-income workers (see Chapter 1).

Table 2.1. Average and marginal tax wedges are relatively low

As % of labour costs, by household type and wage level.

|

|

Average tax wedge |

Marginal tax wedge |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

At: |

|||||

|

no children |

67% |

100% |

167% |

67% |

100% |

167% |

|

|

of the average wage |

of the average wage |

||||

|

OECD average |

30.6 |

34.6 |

39.0 |

40.3 |

43.8 |

45.7 |

|

Australia |

23.3 |

28.4 |

34.7 |

39.6 |

45.3 |

42.4 |

|

Chile |

7.0 |

7.0 |

8.3 |

7.0 |

10.2 |

10.2 |

|

Denmark |

32.4 |

35.2 |

40.8 |

38.7 |

41.7 |

55.5 |

|

Hungary |

43.6 |

43.6 |

43.6 |

43.6 |

43.6 |

43.6 |

|

Iceland |

24.1 |

32.3 |

41.2 |

35.6 |

53.6 |

56.8 |

|

Mexico |

16.5 |

20.2 |

23.2 |

17.5 |

25.2 |

28.4 |

|

Netherlands |

29.0 |

36.4 |

41.5 |

17.5 |

30.0 |

33.0 |

|

New Zealand |

14.0 |

19.1 |

24.5 |

17.5 |

30.0 |

33.0 |

|

Poland |

34.1 |

34.8 |

35.4 |

36.3 |

36.3 |

36.3 |

|

Turkey |

36.4 |

39.7 |

42.9 |

42.8 |

47.8 |

47.8 |

|

Brazil |

31.8 |

32.5 |

36 |

31.8 |

32.5 |

42.9 |

|

China |

34.9 |

30.7 |

30.8 |

22.1 |

22.1 |

32.4 |

|

India |

24.8 |

26.5 (1) |

5.6 |

24.8 |

24.8 |

4.5 |

|

Indonesia |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

7.8 |

|

South Africa |

12.8 |

16.9 |

22.6 |

18.8 |

26.7 |

36.6 |

Note: Average tax wedge is the difference between total labour compensation paid by the employer and the net take-home pay of employees, as a share of total labour compensation. Marginal tax wedge is the difference between the change in compensation and take-home pay as a result of an extra unit of national currency of labour income, as a share of the change in total labour compensation. OECD countries with low social security contributions/payroll taxes are: Australia, Denmark, Iceland and New Zealand. Data are 2020 for OECD countries and 2019 for Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and South Africa. 2) For India, results apply only for the minority case where the employee works in a firm with more than 20 employees

Source: OECD Taxing Wages 2021; OECD Taxing Wages in Selected Partner Countries, 2021.

Broadening the corporate income tax base to reduce the tax rate

Corporate income tax revenues and rate are relatively high

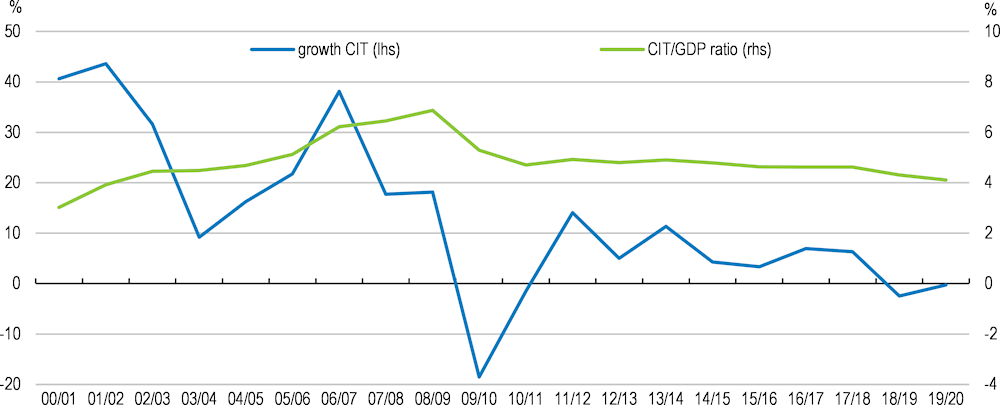

Tax collections from corporates are above the OECD average (Figure 2.3) and concentrated among large companies. Corporate income tax revenues are the third-largest source of government revenues, after taxes on individuals and goods and services. When taxes on dividends (secondary tax on companies) are included, corporate income taxes represented 18.9% and 17.7% of government revenues in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Corporate income tax revenues have been falling with GDP since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (Figure 2.10). Moreover, the economy is highly concentrated, with few companies accounting for the bulk of corporate income tax revenues. Only 381 large companies (0.2% of the companies with positive taxable income) had a taxable income of more than ZAR 200 million in 2019 and were liable for 55.9% of the CIT (SARS, 2021).

Figure 2.10. Corporate tax collection has been trending down since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis

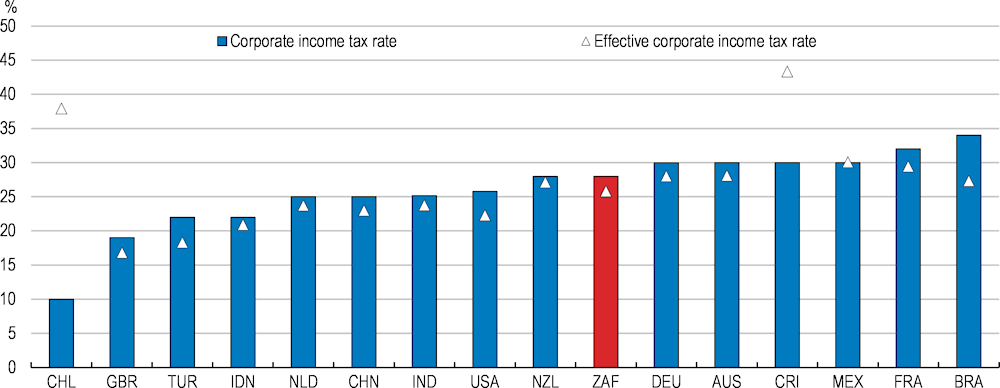

Since the fiscal year 2008/09, the corporate income tax (CIT) rate is levied at a rate of 28%. South Africa’s CIT rate is slightly above the OECD average at 23%, but lower than many emerging market economies, such as Costa Rica, Brazil, India and Mexico (Figure 2.11). The corporate income tax is complemented by a withholding dividend tax of 20%. Dividends are taxed when distributed to individuals or firms, including foreign companies, depending on the provisions of double taxation treaties. In addition, capital gain is included in CIT taxable income at a rate of 80%. The fractional inclusion rate is meant to take into account the effect of inflation on capital gains.

Figure 2.11. The corporate income tax rate is slightly above that in OECD countries

Note: Data for 2020. The effective average tax rate reflects the average tax contribution a firm makes on an investment project earning above-zero economic profits. It is defined as the difference in the net present value (NPV) of pre-tax and post-tax economic profits relative to the NPV of pre-tax income net of real economic depreciation. See OECD Taxation Working Paper No. 38 (Hanappi, 2018).

Source: OECD Tax database.

Reducing tax deductions would allow reducing the headline tax rate

South Africa could reduce its headline CIT rate and aim at offsetting the loss of revenues by broadening the tax base through stronger tax compliance and an improved design of certain tax deductions. The government plans to reduce the CIT rate to 27% in 2022. The corporate income tax gap is high in South Africa, i.e. the gap between what South Africa could theoretically collect and what it actually does (Jansen et al., 2020). The CIT gap (compliance gap for the non-financial sector), as a percentage of the calculated potential current-year tax base, was close to 12% in 2017 as a result of tax evasion.

A company is able to carry forward assessed losses indefinitely, subject only to the requirement that the company continues to carry on trading. The total stock of losses that is carried forward and that have not yet been deducted from taxable profits is large (around 28% of GDP). Corporate tax expenditures in 2019 were around ZAR 20 billion. The government introduced an amendment in November 2021 to limit the amount of losses that can be deducted to 80% of taxable income. Consequently, a minimum of 20% of taxpayers’ income is taxable each year – regardless of the amount of any assessed loss brought forward, which is a positive reform. In addition, the government could consider limiting to 8 years the duration of the carry forward of assessed losses.

Generous interest deductions can bias firms’ behaviour towards the use of debt to finance investment as well as minimise tax liabilities. Multinational groups can use these deductions to optimise intra-group financing (OECD, 2017a). To address these tax optimisation risks, the OECD (2017a) recommended approach is a fixed ratio rule, which limits an entity’s deduction of net interest to a percentage of its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA). As a minimum, this should apply to entities in multinational groups. A ratio between 10% and 30% is recommended. The government introduced an amendment proposing to limit interest deductions through a fixed-ratio limitation for net interest expense to 30% of earnings; and to restrict only connected-party interest rather than total interest (National Treasury, 2020b). The government proposal is in line with the OECD guidelines (2020b) and could be introduced once economic activity recovers from the COVID-19 crisis.

Overall, there is a trade-off between the relatively high headline rate of corporate income tax (28%) and the relatively narrow tax base given the different deductions and the tax gap. One point of corporate income tax collected on average ZAR 7.5 billion in 2019. Therefore, reducing the corporate income tax rate by 3 percentage points, for instance, would cost around ZAR 23 billion, which corresponds to base broadening measures of about ZAR 100 billion (ignoring any behavioural effects that base broadening measures may induce). Lower corporate income tax rates could help boost investment. Such a decrease would need to go hand in hand with a broadening of the tax base so as to not reduce overall corporate income tax revenues.

Tax incentives and investment

Tax incentives reduce tax liabilities and are not always effective in terms of attracting investment and creating jobs. Tax incentives are put in place to encourage local and foreign direct investment. World Bank (2016) analyses show that tax incentives have lowered the cost of capital for all sectors by between 3% and 6.5% and attracted higher investment in the agriculture, construction, manufacturing, trade and services sectors. Overall, the availability of tax incentives was estimated to have generated additional investment of about 2 billion dollars, representing approximately 1% of the capital stock in the long term. The additional investment resulted in approximately 34,000 additional jobs in 2012. More recent evaluations are needed. The cost of tax incentives increased to ZAR 27 billion in 2019 (Table 2.2).

The cost of creating jobs through the tax incentives are high; on average the yearly cost per job created was 116,000 rand. Overall, the World Bank assessment concluded that the tax incentives have mixed effects, depending on the sector. Tax incentives for Small Business Corporations that take the form of reduced corporate income tax rates (see below) were the least efficient in terms of additional investment and cost per additional job. The regime of capital depreciation for Small Business Corporations needs to be reviewed, reduced and harmonised with the regime of other sectors (Table 2.3). The overall system of incentives is also complex for firms to navigate, particularly for smaller firms, and transparency is reduced (and costs likely higher) for schemes that are administered by government departments.

The government’s review of all tax expenditures, among which tax incentives, has revealed that many tax incentives do not result in additional investment. The 2021 Budget Review provides an estimation of the foregone tax revenues of a wide range of corporate tax incentives (Table 2.2). As part of the results of this review, end dates were included for some tax incentives in 2020. A regular evaluation of the economic impact of tax incentives is needed, which in addition to the foregone revenues also measures the additional investment or jobs that have been created.

Venture capital funds are needed to replace the venture capital tax incentive. Taxpayers investing in a venture capital company were allowed an upfront deduction for their investment to encourage the establishment and growth of small, medium and micro enterprises. The National Treasury has determined that the incentive has not adequately achieved its objectives (National Treasury, 2021a). The incentive has instead provided a generous tax deduction to wealthy taxpayers and most support has gone to low-risk ventures that would have attracted funding without the incentive. The incentive was not extended beyond its sunset date of 30 June 2021. However, access to seed funding remains limited for start-ups and SMEs (OECD South Africa Economic Survey, 2017b). In 2017, through the CEO Initiative, the South Africa SME Fund was created, raising around ZAR 1.4 billion with contributions from about 50 firms and the Public Investment Company. The SA SME Fund provides funding to SMEs through market mechanisms and venture funds. The government could consider increasing its support to venture capital through the SA SME Fund.

Table 2.2. Corporate income tax expenditures have been increasing

In Rand million

|

|

2016/17 |

2017/18 |

2018/19 |

2019/20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Small business corporation tax savings |

3,114 |

3,198 |

3,127 |

2,633 |

|

Reduced headline rate |

3,069 |

3,151 |

3,085 |

2,588 |

|

Section 12E depreciation allowance |

44 |

47 |

42 |

45 |

|

Research and development |

234 |

266 |

279 |

119 |

|

Learnership allowances |

1,071 |

721 |

576 |

415 |

|

Strategic industrial projects (12I) |

693 |

563 |

361 |

16 |

|

Film incentive |

15 |

6 |

0 |

19 |

|

Urban development zones |

277 |

318 |

307 |

325 |

|

Employment tax incentive |

4,656 |

4,317 |

4,512 |

4,754 |

|

Energy-efficiency savings |

1,223 |

608 |

1,913 |

120 |

|

Total corporate income tax |

16,827 |

18,380 |

27,334 |

12,572 |

Source: National Treasury, Budget Review 2022.

Tax incentives for specific sectors or economic zones are often not successful. Many developing and emerging countries seek to attract capital investment by setting tax incentives in specific sectors or economic zones. These tax incentives come with different types of economic distortions. For instance, they can disadvantage local firms competing with foreign investors in a sector or direct investment into economic zones at the expense of other economic areas. Tax incentives also create windfall gains for firms that would have invested anyway. In South Africa, tax incentives for certain industries or economic zones take the form of accelerated capital depreciation (i.e. tax depreciation that is quicker than the economic depreciation of the asset, which constitutes a neutral tax treatment). Accelerated capital depreciation allowances are preferred to reduced rates or tax holidays in terms of optimal tax policy as they directly target investment expenses.

Overall, tax depreciation allowances vary widely across sectors, firm size and within special economic or urban development zones for the same type of capital, differing in terms of tax depreciation rates and length of depreciation (Table 2.3). Aligning the tax depreciation rules across sectors for the same type of capital would avoid tax-induced distortions. The government could consider reviewing the regimes of capital depreciation and defining a more neutral regime designed in terms of types of assets and their use rather than varying the tax depreciation treatment across sectors and firm sizes.

Table 2.3. There are various special tax regimes for capital investment in 2021

|

Target |

Capital allowance treatment |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|

|

Manufacturing |

Machinery and plant used in manufacturing activities: 40%, 20%, 20%, 20%. |

. |

|

Agriculture |

Machinery and plant used in farming : 50%, 30%, 20% |

|

|

Mining |

Machinery and plant used in mining: 100% |

Ring fencing applies to 100% deduction, both in respect of mining income and on a per-mine basis. |

|

Renewable energy |

Machinery, plant and equipment for the production of biodiesel or bio-ethanol and the generation of electricity from wind, solar, hydropower or biomass: 50%, 30% 20%. |

Machinery and plant for the production electricity for solar energy not exceeding 1 MW benefits from 100% allowance. |

|

Special Economic Zones |

Non-residential buildings erected within SEZs: 10% straight line |

Industry carve outs and additional requirements apply. |

|

Infrastructure and housing |

Pipelines used for transporting natural oil, lines or cables used for the transmission of electronic communications: 10% straight line Low cost residential units: 10% straight line |

A 5% straight line applies to pipelines, transmission lines and cables for other uses, as well as other types of residential units. |

|

Small Business Corporations (SBC) |

100% capital allowance of Plant and Machinery used in manufacturing; Capital allowance of Plant and Machinery of 50%, 30%, 20% for non-manufacturing activities. |

SBCs are defined as corporations with gross income below a 20 million rand threshold and includes certain restrictions as provided under Section 12E of the Income Tax Act (1962). |

Note: Table does not include incentives in the process of phase out (e.g. section 12I and section 13quat) or depreciation schedules considered part of the standard capital allowance treatment.

Source: Celani, A., L. Dressler and M. Wermelinger (2022), "Building an Investment Tax Incentives database: Methodology and initial findings for 36 developing countries", OECD Working Papers on International Investment, No. 2022/01, OECD Publishing, Paris,

The new international two pillar tax and corporate taxation in South Africa

The OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (IF) has agreed a two-pillar solution to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy (OECD, 2021a). The first pillar is designed to update the international tax rules for the digitalisation of the economy to ensure that MNEs pay taxes where they conduct sustained and significant business, even when they do not have a physical presence. Under the agreement, MNEs will pay more taxes where they sell their goods. The first pillar applies to multinational enterprises (MNEs) with global turnover above 20 billion euros and profitability above 10% (i.e. profit before tax/revenue) with the turnover threshold to be reduced to 10 billion euros contingent on successful implementation. Countries (jurisdictions) where these large MNEs derive at least 1 million euros in revenues will receive additional taxing rights. For smaller jurisdictions with GDP lower than 40 billion euros, the revenue threshold will be set at 250 000 euros (OECD, 2021a).

South Africa should benefit from the introduction of Pillar One as soon as MNEs make more than 1 million euros in revenue from the territory. Pillar One requires the removal of all digital service taxes and relevant similar measures on all companies. South Africa does not have a digital service tax, but has VAT on electronic services, which is a consumer indirect tax and therefore will not be affected by the removal of digital service taxes requirements.

Pillar Two introduces a minimum effective global corporate income tax set at 15%. The second pillar aims to impose multilaterally-agreed limits on tax competition by applying a top-up tax, using an effective tax rate test, to achieve a minimum effective direct tax rate across the globe of 15% (OECD, 2021a). Most South African firms would not be subject to the top-up rate as the effective corporate income tax rate, on average across firms of a particular size, is above 15% as far as their taxable income is positive and only a few South African companies will meet the revenue threshold requirement (Table 2.4). However, in some sectors, the percentage of firms reporting negative or zero taxable income is high. For instance, in mining and quarrying and in manufacturing only 32.3% and 40.5%, respectively, of firms reported a positive taxable income in 2018 (SARS, 2020a). This is likely the result of generous tax incentives that could be affected by the new rule. However, the rule contains a substance-based carve out which may limit the impact on mining firms with substantial tangible assets and employees.

Table 2.4. The effective corporate income tax is above 15%

|

Taxable income group |

Number of Taxpayers |

Taxable income (Rand million) |

Average tax rate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

A: < -10 000 000 |

6,151 |

-877,241 |

-0.1% |

|

B: -5 000 001 to -10 000 000 |

4,936 |

-34,523 |

0.0% |

|

C: -1 000 001 to -5 000 000 |

26,106 |

-57,609 |

0.0% |

|

D: -500 001 to -1 000 000 |

18,045 |

-12,932 |

-0.1% |

|

E: -250 001 to -500 000 |

18,331 |

-6,641 |

0.0% |

|

F: -100 001 to -250 000 |

20,698 |

-3,453 |

-0.1% |

|

G: -1 to -100 000 |

40,533 |

-1,357 |

-2.7% |

|

H: =0 |

109,322 |

- |

0.0% |

|

I: 1 to 100 000 |

40,867 |

1,621 |

17.4% |

|

J: 100 001 to 250 000 |

19,992 |

3,303 |

19.7% |

|

K: 250 001 to 500 000 |

16,825 |

6,062 |

20.2% |

|

L: 500 001 to 750 000 |

9,084 |

5,556 |

23.3% |

|

M: 750 001 to 1 000 000 |

5,596 |

4,868 |

25.7% |

|

N: 1 000 001 to 2 500 000 |

12,510 |

19,868 |

27.6% |

|

O: 2 500 001 to 5 000 000 |

6,214 |

21,789 |

28.8% |

|

P: 5 000 001 to 7 500 000 |

2,654 |

16,233 |

28.3% |

|

Q: 7 500 001 to 10 000 000 |

1,422 |

12,281 |

28.1% |

|

R: 10 000 001 to 25 000 000 |

2,899 |

44,955 |

28.1% |

|

S: 25 000 001 to 50 000 000 |

1,155 |

40,367 |

28.1% |

|

T: 50 000 001 to 75 000 000 |

391 |

23,613 |

27.9% |

|

U: 75 000 001 to 100 000 000 |

224 |

19,480 |

28.5% |

|

V: 100 000 001 to 200 000 000 |

332 |

46,250 |

28.0% |

|

W: >200 000 001 |

342 |

394,905 |

27.1% |

Note: For the 2021 Tax Statistics publication, SARS has reclassified these previously effective rates as average tax rates.

Source: South African Revenue Service (2021), Tax Statistics.

South Africa will benefit from the Pillar Two as it should reduce tax competition from some regional jurisdictions. However, Pillar Two could limit the effectiveness of some generous tax incentives from the point of view of attracting investment. The level of tax benefits that the government can provide to foreign investors will be limited because other jurisdictions will be able to apply a top-up tax up to 15% to the low-taxed profits (OECD, 2020c). South Africa should review its tax incentives policy with respect to this new global taxation rule and ensure its compliance and its effectiveness in terms of reaching its objectives.

Reforming the taxation of SMEs

Small business tax reductions amount to between ZAR 2.5 and ZAR 3 billion per year (Table 2.2). The reduction comes from two special tax regimes for small businesses. First, there is a simplified microbusiness (including self-employed) regime for microenterprises with a turnover below ZAR 1 million. It allows tax-free gross income of ZAR 335 000 and a marginal rate that rises to 3% of turnover. The take up rate of the microbusiness regime is low, in part because loss making firms are also required to pay tax on their turnover. Second, there is a “Small Business Corporations” regime designed for firms with turnover between ZAR 1 million and ZAR 20 million. Currently, small corporations are taxed at 0% on the first ZAR 87,300 of taxable income earned, 7% on the amount above ZAR 87,300 but not exceeding ZAR 365,000, 21% on the amount above ZAR 365,000 but not exceeding ZAR 550,000, and 28% on the amount exceeding ZAR 550,000.

The large jumps in tax rates for small businesses, when their taxable income grows above the thresholds, can create disincentives to grow and incentives to hide income or inflate costs. A disproportionate number of firms is declaring taxable income just below the three thresholds (Boonzaaier et al., 2016; Bell, 2020). An alternative is to merge the two regimes and to introduce a progressive tax rate schedule that would lower the tax burden on businesses with lower turnover, such that they face an incentive to enter the formal economy, and higher presumptive tax rates for larger firms, such that they are induced to enter the standard tax regime. The presumptive tax rates could also vary across sectors, aligned with the average sector-specific profitability rates. The Davis Tax Committee (2014, 2016) has been critical of the Small Business Corporations, noting that it has become ineffective as it largely benefits service-related small businesses (such as financial, education, real estate, medical and veterinary services). In contrast, the system was intended to benefit emerging businesses or to assist ailing enterprises in an assessed loss position. The Small Business Corporations scheme could be restricted to young firms, so that after a fixed period, firms “graduate” to the standard regime (with measures to ensure firms do not abuse the system). Such a reform could be accompanied by a reform of the presumptive tax regime for very small businesses.

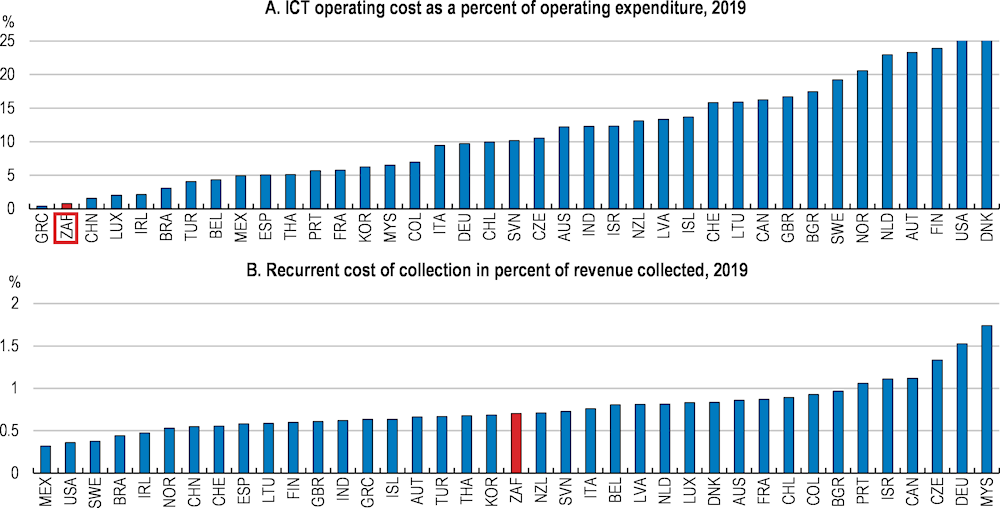

Other concerns with these regimes, and in general, are administrative costs for the South African Revenue Services (SARS), while their share of collected taxes is relatively low (around 4% of tax revenue and around 11% of VAT). In particular, slow processing of VAT refunds has been a source of burden. SARS has increased its assistance for SMEs with 138 small business desks at its branches and a call centre. SARS effort to reduce the delays of VAT refunding should be pursued and monitored (SARS, 2020b). Recent changes to issue tax clearance certificates electronically are welcome. SARS should continue to expand its education and assistance to build capability and encourage compliance.

Revenues from natural resource extraction could be increased

The mining industry accounted for around 8% of economic activity in recent years, but with variation over the economic cycle. Gold and diamonds are the traditional mining activity but platinum, iron ore, copper, coal, manganese and other mineral resources represent an increasing and by now substantial source of activity. In 2010, South Africa adopted a new taxation system for mineral resources.

The government opted in 2010 for a royalties-based system to ensure an upfront and more stable revenue stream, as many countries with mining industries do. The royalty regime adopted is relatively complex as tax rates vary with profitability and imply a determination of taxable income based on sales. There is a floor of 0.5% and rates are capped at 7% for unrefined products and 5% for refined products. Nonetheless, as a royalty, it captures part of the normal return as well as the resource rent, affecting investment incentives. The mining taxation regime has two factors to provide incentives for investing in the sector: (i) an upfront full depreciation on mining investment, which can be carried forward indefinitely, and (ii) specific incentives to encourage exploration and development in the oil and gas industry. However, these incentives are reduced by “ring-fencing” of projects, which prevents depreciation expenses of one project from being offset by profits elsewhere (in the oil and gas industry, 10% of profits can be transferred to another project). This protects the tax base but reduces the immediate benefit of the incentives.

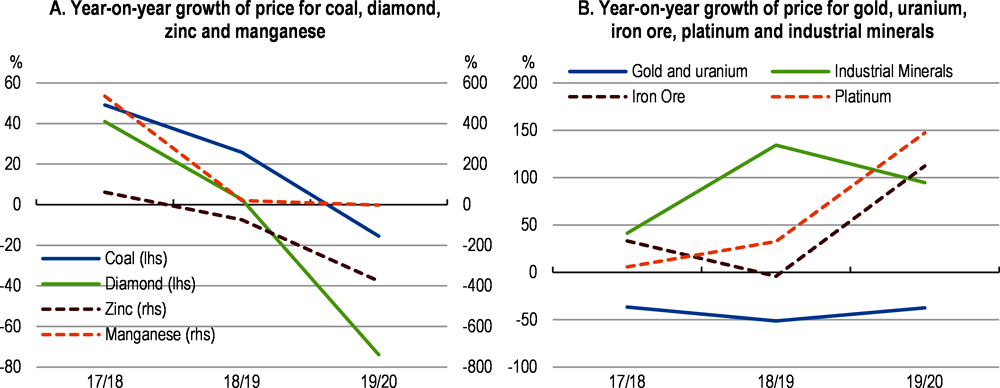

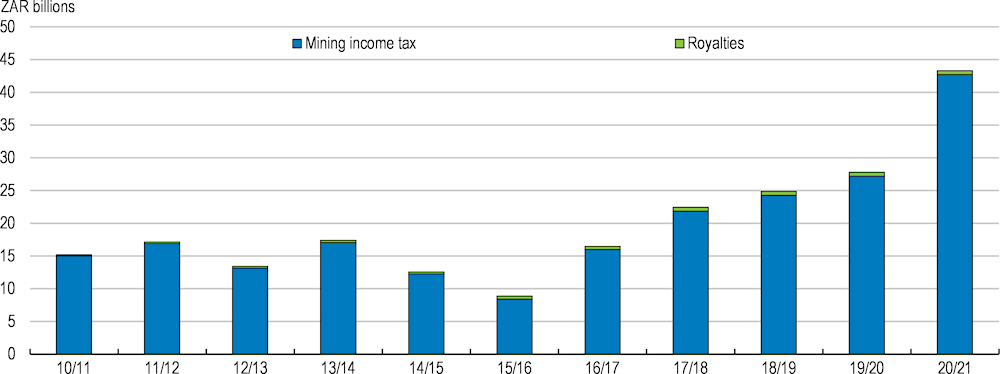

The royalty regime has generated increasing tax revenues (Figure 2.12). Mineral and Petroleum Resources Royalty (MPRR) revenues grew significantly by ZAR 2.4 billion (20.3%) to ZAR 14.2 billion in 2020/21, after an increase by 37.4% in 2019/20, due to a significant improvement in commodity prices such as iron ore as well as platinum (Figure 2.13). It is difficult to compare revenues from natural resources with other countries (OECD Economic Survey of South Africa, 2015a). The structure of ownership (state owned or private), the resources mix (since oil and gas extraction are often taxed more heavily) and the degree of diversification of the tax base make comparisons complicated (Table 2.5). However, comparing with royalty regimes in some countries, there is some scope to increase the effective tax rate in South Africa without overly dampening investment incentives. For example, the combination of corporate income tax and royalty regime could be kept while slightly increasing the marginal rate of the royalty regime.

The Davis tax committee recommended that the upfront capital expenditure deductions be abolished and to replace it with an accelerated deduction scheme as in the manufacturing industry. Aligning further the mining sector’s tax regime with the general taxation regime implies removing the capital depreciation allowance and the ring-fence scheme. The SARS estimated the amount of unredeemed capital expenditure to be around ZAR 140 billion in 2015. An outright removal of these unredeemed capital expenditure would convert them into assessed losses and therefore an important foregone tax revenue. Mining investments are important, and it is relevant to provide incentives to attract investment. However, a 100% capital depreciation regime, including expenses unrelated to capital expenditures seems overly generous. The capital depreciation regime could be amended to reduce its generosity.

Figure 2.12. Royalties added 2.5% to revenues from the mining sector

Note: Mining and quarrying sector.

Source: South African Revenue Service, Tax Statistics 2017 and 2021.

Figure 2.13. Mineral and petroleum resources royalty revenues reflect price volatility

Table 2.5. There is room to increase the marginal rate of the royalty regime

|

Country |

Corporate tax rate |

Royalty rate for key mineral resources |

Tax base for royalty |

Other mining taxes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

30% for entities with turnover greater than AUD10 million. |

2.5-20%, or AUD$0.5-AUD$2.64 per tonne, depending on mineral types and States/Territories [1] |

Value or production volume |

Petroleum resource rent tax at 40% on taxable upstream profits from a petroleum project. |

|

Brazil |

Base rate: 15% High income rate: 25% Social contribution on profits: 9% |

State/municipality royalty: 0.2-3% Surface rights royalty: 0.1-1.5% |

Net revenue |

Inspection tax at up to US$3 per tonne of ore. Social welfare tax at 0.65% (cumulative) and 1.65% (non-cumulative); service importation 1.65% and good importation 9.65%. Municipal service tax at maximum 5%. |

|

Chile |

4–20% for medium-scale operations; 24% for large operations |

0–14% depending on production |

Production volume |

External trade tax of 6% for import of minerals. |

|

Colombia |

32% |

1–12%, depending on mineral types |

Production volume |

Dividends tax: 10%. Industry and trade tax: 0.2-1.1%. |

|

Peru |

29.5% |

1–12% |

Operating profit |

Dividends withholding tax: 5%. Special mining tax: 2–8.4%. Special mining contribution: 4–13.12%. Temporary tax on net assets: 0-0.4%. Financial transaction tax: 0.005%. |

|

South Africa |

28% for all minerals other than gold. Formula for gold mining tax |

0.5-5% for refined minerals and 0.5-7% for unrefined minerals |

Value of the minerals |

Capital gain tax on disposal of assets at 20%. Withholding tax on dividends at 20%, and withholding tax on interest at 15%. |

Note: 1) Royalty rates vary by States/Territories.

Source: Cunsolo and McKenzie (2020); Deloitte (2013); Advogados (2019); Muñoz (2019); Bambach and Pulgar (2020); Salazar, Serrano and Ochoa (2021); Pardo and Lugo (2020); Pickmann (2019); SARS (2021); FERDI (2021).

Taxes on goods and services are large and effective

The VAT system performs relatively well

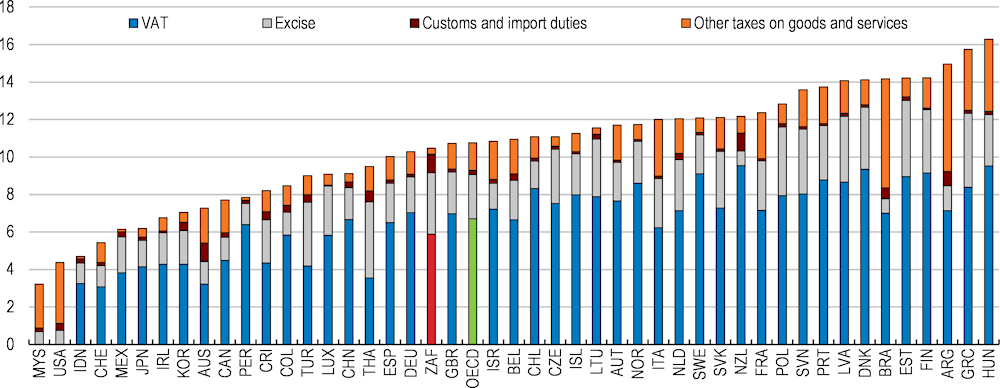

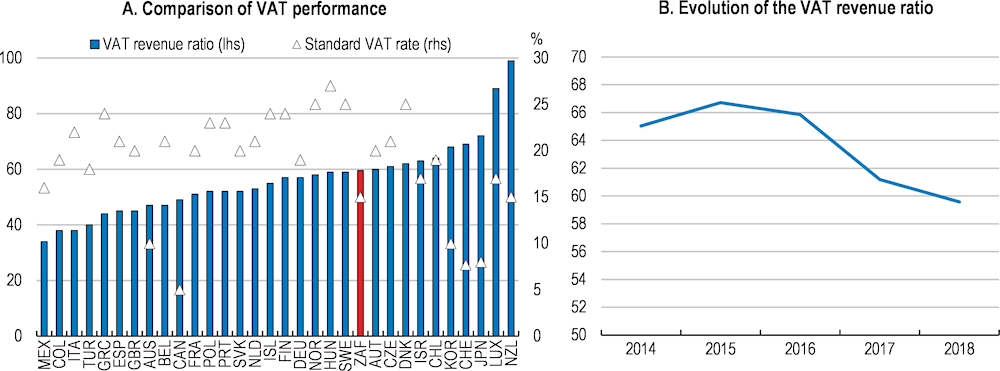

The VAT is the second largest source of tax revenue, on average representing a quarter of government revenue over the past decade and raising revenues comparable to that of OECD countries (Figure 2.14). From 1993 to 2017, the standard VAT rate has remained at the comparatively low level of 14% and applied to the vast majority of goods and services. The VAT rate was increased to 15% in 2018. However, there is preferential treatment for a number of items and services, mostly in the form of a reduced VAT rate (of 0%). Zero-rated items and services include 19 basic food items, petrol and diesel (in addition to exports, which is a basic design feature of a VAT that is levied on a destination basis), while exempted items and services include public transport, education, financial services and childcare services. In 2014, the tax base was broadened to include imports of digital services.

The VAT revenue ratio calculated as the ratio of VAT revenue to consumption net of VAT as the potential base is an indicator of the VAT’s performance in raising revenue. While the VAT revenue ratio compares favourably with OECD countries (Figure 2.15, Panel A), it declined in recent years, from 67% in 2015 to 60% in 2018 (Figure 2.15, Panel B). Although changes in consumption patterns in a low-growth environment where more zero-rated items are consumed may explain a decline in VAT performance, scope exists to strengthen the functioning of the VAT. Further detecting fraud and smuggling, and measures to increase VAT registration and reduce informality will increase revenues.

Figure 2.14. VAT revenues are close to OECD countries

Revenue from taxes on goods and services, % of GDP, 2019

Figure 2.15. The collection of VAT remains performant

Note: The VAT Revenue Ratio is calculated as actual VAT revenue divided by potential VAT revenue (the standard rate applied to total final consumption less VAT revenue). For Panel A, data are for 2018 for OECD countries and 2017/18 for South Africa.

Source: OECD Consumption Tax Trends 2020, Table 2.7. VAT Revenue Ratio (VRR) 2018; OECD National Account Database; Tax Statistics; OECD Calculations.

Many OECD countries have used technology to enhance the reporting of tax relevant data to tax authorities. Thirty-one OECD countries have generalised mandatory e-filing of VAT returns (OECD, 2015b), and have introduced or are considering the introduction of an obligation for taxpayers to provide transaction data electronically to tax authorities, sometimes in real time. These measures generally require that detailed information be provided in an electronic format at the level of each individual taxable transaction. This information can include invoicing information and accounting data or any other information that allows tax authorities to monitor supplies made and/or received by individual taxpayers (OECD, 2020d). As the SARS has stepped up e-filling, using third-party data and cross checking could improve the detection of underreporting and undue claims of VAT refund. Introducing electronic invoices would improve VAT collections and increase information available to detect fraudulent behaviours (see Box 2.1). South Africa could start with mandatory electronic VAT invoicing for business-to-business and business to government transactions.

Box 2.1. Features of electronic invoicing in selected OECD countries

Chile: The obligation to use electronic invoicing and to provide B2B transaction information electronically to tax authorities started in 2003. In 2017, this obligation was extended to the provision of other accounting data to an electronic record kept by the tax authority. Transaction data must be transmitted to tax authorities in real time. As from January 2021, the Law 21210 has introduced the obligation to issue B2C invoices electronically. The electronic invoice can be sent through any electronic method (cell phone, email, etc.) provided that it is accessible to the consumer and the business.

France: Electronic invoicing is not mandatory, except for B2G supplies. Electronic invoicing should become mandatory for all B2B supplies by 2025 at the latest. Electronic transaction information: taxpayers keeping electronic accounts must provide them in the form of digital files upon request by tax administration for control purposes.

Hungary: Invoicing information must be transmitted to the tax authorities at the same time the invoice is emitted by the taxpayer (real time reporting). Information on ‘paper invoices’ must be provided to the tax authorities within a 1 or 5-day deadline (depending on whether the value of VAT figuring in the invoice surpasses – respectively – HUF 500 000 or HUF 100 000). Information must be provided concerning all invoices emitted in respect of domestic supplies to taxable persons registered in Hungary (B2B).

Italy: All VAT-registered businesses established in Italy are obliged to accept and issue invoices in electronic format through the Italian Revenue Agency’s e-invoicing platform, Sistema di Interscambio (SdI), except for VAT exempted transactions. From 1 January 2020 and with a few exceptions, taxpayers engaged in the retail trade and similar activities must register their supplies electronically and transmit them to the Italian Revenue Agency, regardless of their turnover.

Mexico: Electronic invoicing is mandatory since 1 January 2014. The transmission of transaction data to the tax authority is mandatory since 1 January 2015. This obligation applies to all taxpayers and covers the domestic supplies of goods and services for both B2B and B2C transactions. Periodic transmission of transaction information is also imposed to all taxpayers.

Turkey: From 1 January 2020 paper invoices are no longer legally valid. All invoices must be sent under electronic format via the “e-arşiv fatura” system. Every time an electronic invoice is issued, the recipient receives a notification by email. All businesses must file a daily statement with a summary list with all the e-arşiv fatura and send it to the tax administration.

Source: OECD (2020), Consumption Tax Trends 2020: VAT/GST and Excise Rates, Trends and Policy Issues, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/152def2d-en.

Given that consumption taxes are one of the least distortive forms of taxation and that the current VAT rate is relatively low, there is scope to raise additional revenues to help improve fiscal sustainability. Lifting the rate by 1 percentage point could raise VAT revenues by 7%, equivalent to ZAR 17 billion (using the current rate of VAT efficiency to allow for leakage). The VAT rate hike in 2018 from 14% to 15% raised concerns about its impact on poverty and inequality. An alternative proposal consisted of a reduction in the number of zero-rated items and an increase in direct social transfers to counter the effects of raising VAT rates on poorer households.

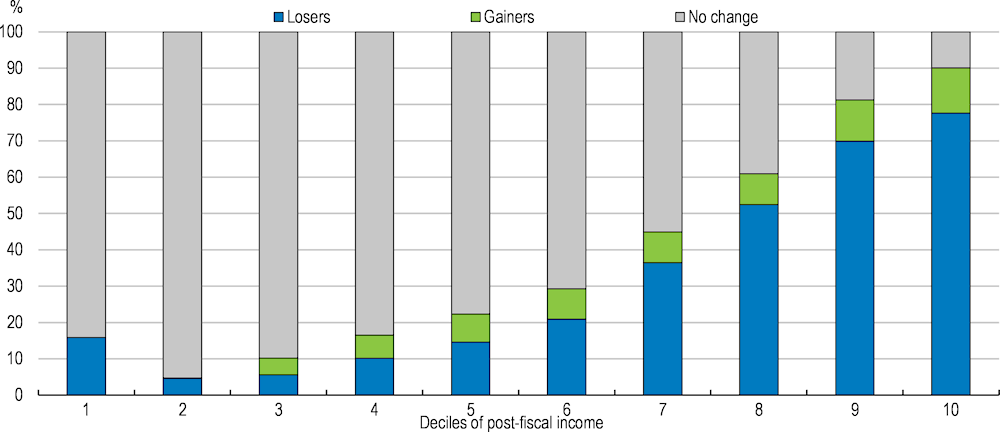

Different analyses show that the VAT is mildly progressive, with the implicit VAT rate (VAT paid as a share of disposable income) rising from 9.5% for the lowest income decile to 12% for the highest income decile (Inchauste et al., 2015). This is largely because food items with preferential VAT treatment are a larger share of overall consumption for poorer households (Jansen and Calitz 2015). A recent assessment of a potential VAT rate increase shows that high-income deciles would be more affected than low-income deciles. The simulation by Gcabo et al. (2019) indicates that the lowest decile is, however, affected even after the increase in social grants (Figure 2.16). Nonetheless, as many adults and youth do not benefit from social transfers, it is preferable for political acceptability to maintain the preferential VAT regime, except with respect to diesel and petrol given their negative impact on climate, and to better target transfers to low-income households (i.e. increasing the amount of the transfer and ensuring that all poor households are reached) when increasing the standard VAT rate.

Figure 2.16. The impact of the VAT rate increase varies across income decile

Percentage of losers, gainers and those neither losing nor gaining by post-fiscal income deciles, 2018

Source: Gcabo et al. (2019), Modelling value-added tax (VAT) in South Africa: Assessing the distributional impact of the recent increase in the VAT rate and options for redress through the benefits system, WIDER Working Paper 2019/13.

Other indirect taxes contribute significantly to government revenues

Excise taxes raise significant revenues

Excise taxes on fuel, alcohol and tobacco are equivalent to 10% of government revenues. Fuel excises are discussed below in relation to environmentally related taxes. Excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco are set to reduce consumption of those products, improving the health of citizens. Tobacco consumption remains high, as 19% of the adult population are daily smokers. Smoking is particularly prevalent among men with 31% of them smoking daily (OECD South Africa Economic Survey, 2020a). Since 1994, the government has raised the excise tax on tobacco significantly. The combined excise tax and the value added tax was increased from 32% of the retail price in 1996 to 52% in 2006. However, the tax burden of 52% (i.e. excise tax plus VAT) of the retail selling price of the most popular brands was changed in 2015 when government decided to no longer levy VAT but only excise duties on tobacco. This reform effectively reduced the overall tax burden to 40%. Since 2017, the tax on tobacco has been increased further every year.

The World Health Organisation recommends that the excise tax on tobacco be at least 70% of the final retail price, given the evidence that taxation is the most cost-effective method of reducing consumption (WHO, 2011). Fuchs et al. (2019) estimate the years of life lost because of premature deaths attributable to smoking is around 100 years for the whole working-age population in South Africa. Stacey et al. (2018) argue that increasing health tax excises significantly in South Africa will lead to improvements in health and raise revenue. Health tax revenues could be earmarked to roll out universal health care across the entire population. Efforts to reduce tobacco consumption should be pursued both by further increasing excise taxes while developing specific information and education campaigns.

The government increased the excise duties on alcohol and tobacco by 8% for 2021/2022. To tax these products more appropriately, excise duties are differentiated by product type. Products comparable to cigarettes that are normally sold in packs of 10 or 20 sticks are taxed accordingly, while other products will be taxed by weight. The increase of the excise duty on tobacco puts its incidence on final retail price to 45% on average.

However, price differentials with neighbouring countries are already inducing smuggling (SARS, 2014; OECD South Africa Economic Survey, 2015a). Estimations conclude that illicit cigarettes represent between 23% and 35% of the market (Van der Zee et al., 2020 and Vellios et al., 2019). The weakening of the South African Revenue Service may have contributed to the development of illicit cigarettes traffic (see section below). Developing border controls, including random controls from SACU countries and traceability of local productions would limit illicit cigarettes trafficking and increase revenues.

Alcohol consumption is also high. About one third of those aged above 15 years report drinking alcohol regularly and 15.9% and 2.7% of men and women, respectively, are alcohol dependent (Health System Trust, 2018). In 2015, it was decided to no longer tax alcohol under the VAT but to levy only excise duties; this reform reduced the tax burden on alcohol to 11%, 23% and 36% from 23%, 35% and 48% for wine, beer and spirits, respectively. In almost all the following years, the excise taxes on alcoholic beverages were raised with a different treatment for local beer with low alcohol content and wine.

Policy measures targeted at reducing alcohol consumption should follow an integrated approach that extends beyond price incentives, including educational and preventive programmes. Additional measures to reduce alcohol consumption could therefore include the banning of advertisement, restricting places of sale as well as strengthening preventive programmes targeted at vulnerable population groups, which tend to consume more alcohol (National Treasury, 2014 and OECD South Africa Economic Survey, 2020a).

South Africa has one of the highest levels of obesity among its population when compared to OECD and emerging countries. 37.3% of adult women are obese (OECD health Statistics). The Health Promotion Levy was implemented on 1 April 2018. It is a levy imposed on sugary beverages to decrease diabetes, obesity and other related diseases in South Africa. The rate was fixed at 2.1 cents per gram in 2018 and increased to 2.21 cents per gram in 2019 with the first 4 grams per 100 ml free of levy. Following the introduction of the health levy, urban households’ consumption of sugary beverages felt by 29% and the highest drop in consumption was found amongst low-income households (Hofman et al., 2021). The sale of sweetened beverages in school should be banned and preventive health messages linked to their advertisement.

Trade taxes remain significant

South Africa receives a small but significant share of its tax revenue from taxes on trade, as do many emerging economies, equivalent to around 4% of government revenues. This mostly comprises customs duties on imports, with a common external tariff applying to imports from outside the Southern African Customs Union (Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa and Swaziland) and a preferential rate for economies with bilateral trade agreements. Revenue from import duties is pooled and redistributed among the customs union members; South Africa acts as a gatekeeper for the Custom Union and retains around 40% of revenue raised and effectively sets tariff levels as a Tariff Board for the Custom Union has not yet been established.

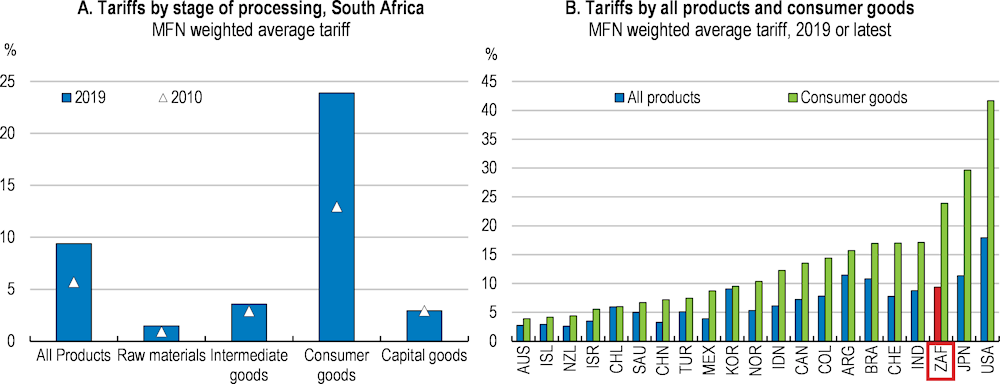

South Africa has largely liberalised its tariffs in the early 2000s. Empirical evidence suggests that earlier trade liberalisation boosted growth and productivity, including through greater domestic market competition (Fall and Laëngle, 2020; Edwards and Rankin, 2015). However, in the past decade, the process of tariff reduction has largely stalled, with rates remaining particularly high on consumer goods (Figure 2.17). These tariffs reflect industrial policy choices to encourage local manufacturing. Tariffs on clothing and footwear (the highest) average almost 40% and particularly affect poorer households, for whom these items represent a larger share of total consumption. Tariffs are also high for motor vehicles and parts as part of the automotive industry programme (under the automotive industry programme local manufacturers can also receive a refund of tariffs paid). In addition, VAT is applied on top of custom tariffs on most imported consumer goods. Better balancing the tariff structure between protection of local industry and sufficient competition could improve consumers’ well-being, in particular poor households. In the long run, competition is also good for industry as it forces firms to become more competitive.

Figure 2.17. Tariffs on consumer goods remain high

Source: UNCTAD Trade Analysis Information System (TRAINS); World Integrated Trade Solution.

Strengthening the tax system to cope with new challenges

Environmental tax policy

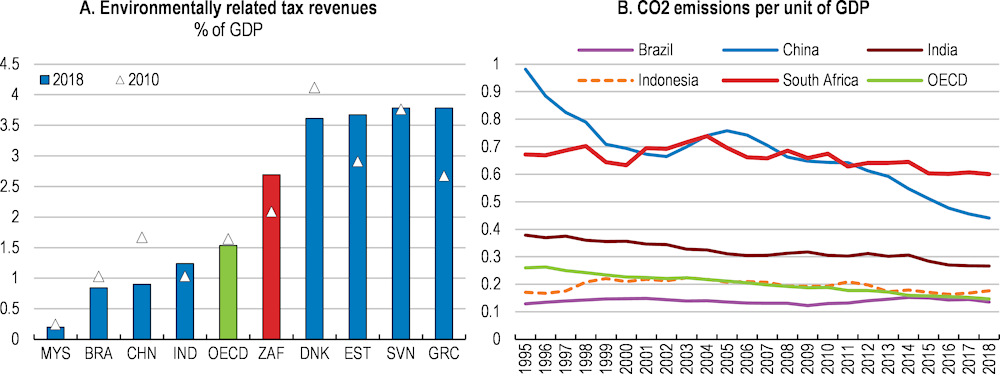

South Africa is increasingly strengthening its environmental tax policy to curb its greenhouse gas emissions. The overall revenue from environmentally related taxes has risen from 2.1% of GDP in 2010 to 2.7% in 2017. This is above the (unweighted) average of OECD countries and higher than in most emerging countries (Figure 2.18, Panel A). Since 2000, several taxes on waste and pollutants have been introduced, with levies on international air travel, plastic bags, incandescent light bulbs, tyres and electricity from non-renewable sources.

The CO2 per GDP emission intensity is high and has fallen little since 2000 (Figure 2.18, Panel B), in part reflecting the high-energy intensity of the economy. This largely stems from the economy’s reliance on coal, which accounts for around 70% of total energy and 85% of electricity generated (see Chapter 1). Coal is the main energy source in industrial processes. In its 2018 draft Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), South Africa announced steps to reduce CO2 emissions in electricity generation. It announced decommissioning of 35 out of currently 42 Gigawatts (GW) of coal-fired capacity by 2050 and to expand renewable electricity generation. However, close to 6 GW of new coal-fired plants are under construction. New plants expose South Africa to the risk of having to write them off early to meet its CO2 emission targets.

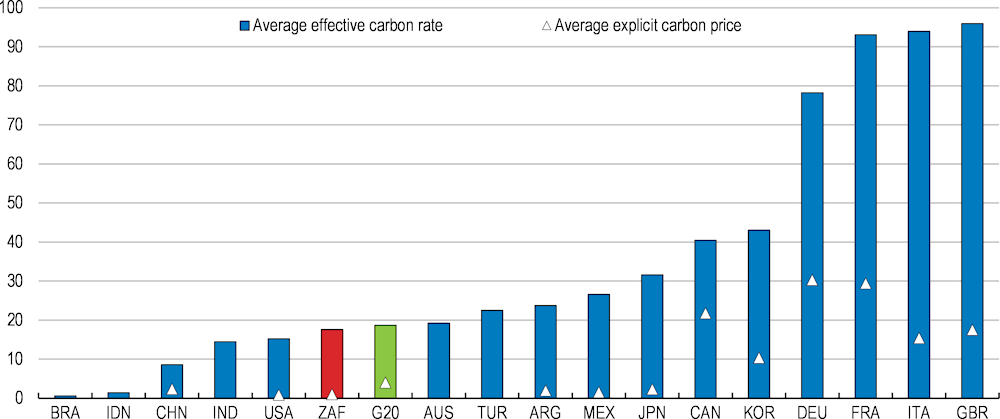

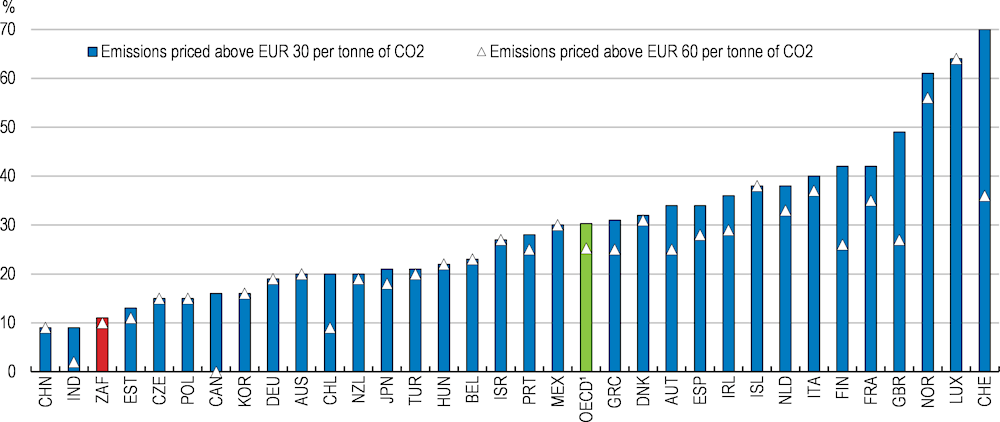

Figure 2.18. Environmentally related tax revenues are increasing but emissions remain high

To reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, South Africa introduced a carbon tax in 2019 at a tax rate of ZAR 120 (EUR 6.5) per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. The gradual implementation of the tax provides for a first phase from 1 June 2019 to 31 December 2022 and a second phase from 2023 to 2030. The carbon tax rate will increase annually by inflation plus 2 per cent until 2022 and annually by inflation thereafter. However, in 2021/22, businesses were granted a delay for the payment of the carbon tax as part of the COVID-19 pandemic response measures. Also, significant industry-specific tax-free emissions allowances, ranging from 60% to 95% of emissions, lead in a mild average carbon tax rate ranging from ZAR 6 to ZAR 48 (EUR 0.3 to EUR 2.7) per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions (OECD, 2021b). Therefore, South Africa’s carbon price is low by international standards (Table 2.5).

The distribution of exemptions across industries places the burden of adjustment disproportionately on low emission sectors and creates unequal price signals, thereby raising the cost of abatement and reducing the share of emissions effectively priced (Table 2.5). An effective and efficient carbon tax requires a uniform marginal rate applied to all sources of emissions (OECD, 2011). This would reduce the economy’s dependence on energy- and carbon-intensive production while making production more labour intensive (Alton et al., 2014). Carbon tax exemptions should be progressively phased out, along with the increase in the share or renewable energy in electricity generation.

In addition, as provided by the 2019 Carbon Act, the National Treasury published amendments to the regulations of the carbon-offset schemes in July 2021 (National Treasury, 2021b). They specify the eligibility criteria for carbon offset projects, procedures for claiming carbon offset allowance and administration of the carbon offset mechanism. The carbon offset tax allowance enables firms to reduce their emissions and carbon tax liability by up to 10% of their total greenhouse gas emissions by investing in carbon mitigation projects. Firms have to register officially their mitigation projects in the Verra registry (an international certificate of voluntary cancellation) or in national registries under the Clean Development Mechanism for claiming carbon offset credits.

To guarantee the integrity of the carbon offsetting mechanism, the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy should finalise quickly the regulations defining local standards that determine whether a project qualifies as a carbon offset project. Also, strict monitoring of the certification process of projects will be key in safeguarding the integrity of the carbon offsetting mechanism.

Finally, the carbon component of other energy taxes, such as the environmental levy on electricity generated from fossil fuels and nuclear, should be reviewed to simplify the policy framework and ensure that the effective rate is increasing over time. A review of the impact of the carbon tax three years after implementation is planned by 2022.

Figure 2.19. The carbon price is low in part due to exemptions

EUR per tonne of CO2, 2021

Note: G20 includes all G20 countries, except Saudi Arabia. Taxes are those applicable on 1 April 2021. Average effective carbon rate is the sum of explicit carbon prices and fuel excise taxes. Explicit carbon price refers to price that uses carbon taxes and emissions trading systems to raise the cost of carbon-intensive fuels, thus encouraging firms and households to make more climate-friendly choices. Emissions refer to energy-related CO2 only and are calculated based on energy use data for 2018 from IEA, World Energy Statistics and Balances 2020. Carbon prices are averaged across all energy-related emissions from G20 countries, including those that are not covered by any carbon pricing instrument. All rates are expressed in real 2021 EUR using the latest available OECD exchange rate and inflation data; change can thus be affected by inflation and exchange-rate fluctuations. Prices are rounded to the nearest euro cent.

Source: OECD (2021), Carbon pricing in times of COVID-19: What has changed in G20 economies? OECD, Paris.

Figure 2.20. The share of emissions taxed remains low

Emissions priced in percentage of total emissions, 2018

1. Average of OECD countries with available data.

Source: OECD (2021). Effective Carbon Rates 2021, http://oe.cd/ECR2021.

Fuel taxes are relatively high and contribute significantly to government revenues (Table 2.6). Taxes on transport fuels represent around 40% of the fuel price (in February 2021). This is around the OECD average and similar to large non-OECD countries. Nonetheless, there is scope for further gradual increases. IMF estimates on the level of taxation needed to correct for externalities revealed that fuel taxes should be increased further to reflect the cost of road accidents, which are high in South Africa, and congestion, though congestion charging would be more efficient. Financing and regulation of road infrastructure should be reformed, including by replacing the ineffective e-toll system by a pre-payment e-toll system (see Chapter 3). Moreover, some industries are currently eligible for a full or partial refund of the fuel levy for diesel use, notably electricity, mining and agriculture, and individuals benefit from under-taxed fringe benefits for the private use of company cars within the personal income tax. These tax benefits for individuals and businesses should be phased out or reduced and public transport developed to reduce the greenhouse footprint.

Table 2.6. Taxes on fuel are high

|

|

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rands/litre |

93 octane petrol |

Diesel |

93 octane petrol |

Diesel |

|

General fuel levy |

3.70 |

3.55 |

3.70 |

3.55 |

|

Road Accident Fund levy |

2.07 |

2.07 |

2.07 |

2.07 |

|

Customs and excise levy |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

0.04 |

|

Carbon tax1 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

|

Total |

5.88 |

5.74 |

5.88 |

5.74 |

|

Pump price2 |

14.44 |

12.75 |

14.44 |

12.75 |

|

Taxes as a percentage of pump price |

40.7% |

45.0% |

40.7% |

45.0% |

|

Fuel levy |

||||

|

|

2020/21 |

2021/22 |

||

|

Rand million |

75 502 |

89 883 |

||

|

% of Total revenue |

6.1% |

5.8% |

||

Note: 1) The carbon tax on fuel became effective from 5 June 2019. 2) Average Gauteng pump price for the 2019/20 and 2020/21 years.

Source: National Treasury, Budget Review, February 2021.

Improving digital economy taxation to avoid revenue leakage

South Africa pioneered the taxation of cross-border e-commerce transactions (referred to as “electronic services”) in 2014. Foreign suppliers have to register and hold a VAT account on these transactions if their turnover of supplies to South African residents exceeds ZAR 50 000. The turnover threshold has been increased to ZAR 1 million in 2019 to align it with the local transaction threshold. However, because electronic services were narrowly defined, few business-to-business transactions were effectively captured. Following the release of the OECD VAT/GST Guidelines, South Africa, like most other VAT jurisdictions, has broadened in 2019 the scope of e-commerce subject to VAT to cover all services electronically provided, including business-to-business transactions (National Treasury, 2019).