Andrea Salvatori

OECD Employment Outlook 2022

1. A tale of two crises: Recent labour market developments across the OECD

Abstract

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has generated a humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people and has sent shockwaves through the world economy. This new crisis threatens the strength of the recovery from the COVID‑19 one, which had been more robust than initially expected. Nevertheless, even before the shock of the war, the labour market recovery appeared uneven across countries and groups of workers. While some of the initial very unequal impact of the crisis has been reabsorbed, young people and workers without tertiary education lag behind in the recovery in many countries. Despite an unprecedented surge in labour demand, nominal wage growth was dwarfed by the high inflation of the first half of 2022. The impact of inflation on living standards is larger for the same lower-income households which have already borne the brunt of the COVID‑19 crisis.

In Brief

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has generated a humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people and has sent shockwaves through the world economy. Europe has seen the largest and fastest growing inflow of refugees since World War II as millions left Ukraine. The economic fallout of the war is threatening the strength of the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis which till early 2022 had turned out to be stronger than initially expected. The disruption of the war on energy and food markets is adding to the significant inflationary pressures that had already emerged at the end of 2021 as a result of supply chain disruptions. In the first of half of 2022, inflation reached levels not seen in decades in many OECD countries eroding workers’ living standards as nominal wage growth remained generally modest despite the tight labour markets. The impact of inflation is felt disproportionally by the same lower-income households that have already borne the brunt of the COVID‑19 crisis.

The latest available evidence at the time of writing suggests that:

Labour market conditions continued to improve across the OECD in the first half of 2022. Total employment in in the OECD area as a whole returned to pre‑crisis levels at the end of 2021, and continued to grow in the first half of 2022. The OECD unemployment rate gradually fell from its peak of 8.8% in April 2020 and stabilised in the first months of 2022. In July 2022, the OECD unemployment rate stood at 4.9%, slightly below the 5.3% value recorded in December 2019.

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has caused a humanitarian crisis affecting millions in Ukraine and beyond, and has disrupted energy and food markets, putting a drag on world growth and fuelling inflation. The refugee flows caused by the war will result in additional public expenditure in the short-term in host countries, although this will be offset over time as refugees enter the labour force. Global GDP growth in 2022 is now projected to slow to 3.0% from 4.5% projected by the OECD in December 2021 and remain at a similar pace in 2023

Before the new shock of the war in Ukraine, some countries were still lagging behind in the recovery. In Q1 2022, employment and inactivity rates had improved relative to pre‑crisis levels in most countries. However, ten countries still had employment rates below pre‑crisis levels, and 11 countries featured inactivity rates higher than just before the crisis. In July 2022, unemployment was below pre‑crisis levels in 24 countries, and above that level by more than 0.5 percentage points only in Finland and Estonia.

In the second half of 2021 and early 2022, vacancies surged to record highs in many countries and the number of firms reporting labour shortages rose significantly above pre‑pandemic levels in many industries and countries. There is currently no indication of systematic mismatches between supply and demand caused by the asymmetric impact of the crisis on different sectors. Rather, the pervasiveness of reports of labour shortages across countries and industries suggests that, in most industries, the ongoing labour market tensions arise primarily from the sheer speed of the increase in labour demand in recent months supported by a strong global demand and massive recovery plans.

Labour shortages have been particularly intense in some low-pay sectors, such as food and accommodation. The lingering pandemic might have made these low-paid jobs that typically involve direct contact with customers less appealing and might have accentuated the perception of the lower quality of these jobs. The tightening of the labour market may help improve working conditions in these industries. Indeed, in some countries nominal wage growth has been stronger than average in these sectors, while still generally remaining well below the high inflation of the last few months.

Despite increasing labour market tightness, nominal wage growth generally remains well below the high inflation of the first half of 2022, causing real wages to fall. The decline in the real value of wages is expected to continue over the course of 2022, as inflation is projected to remain elevated and generally well above the level expected at the time of collective agreements for 2022.

The impact of rising inflation on real incomes is larger for lower-income households which have already borne the brunt of the COVID‑19 crisis. The hike in energy and food prices is hurting low-income households the most because these items represent a higher share of their total spending and because they have more limited scope to draw on savings or to reduce discretionary expenditures. These households disproportionally include low-pay workers who were more likely to have their income reduced during the COVID‑19 crisis either through job loss or a reduction in hours worked.

Employment dynamics across industries are still heavily influenced by the COVID‑19 crisis, as low-pay service industries, in which telework is typically less feasible, lag behind in the recovery. In Q1 2022, on average across the OECD, employment was still below pre‑crisis levels in low-pay services industries. By contrast, some high-pay service sectors expanded over the same period. These patterns have significant implications for the evolution of employment outcomes of different groups of workers during the recovery.

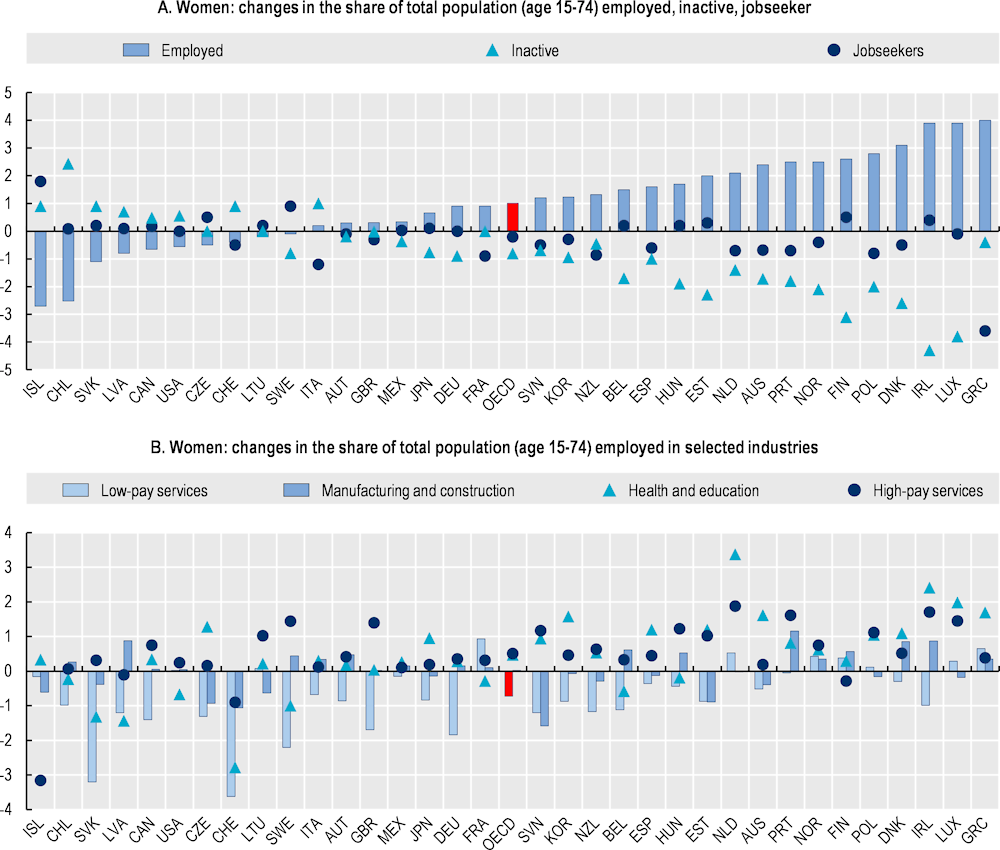

After the initial hard blow, women’s employment progressively improved during the recovery despite the increased burden of unpaid care work. The initial impact of the pandemic was felt more strongly among women than men across the majority of OECD countries, but by 2022 the employment gap between men and women had declined in most countries relative to pre‑crisis levels. Over the course of the crisis, women have shouldered the bulk of the burden from the increase in unpaid care work when schools and childcare facilities were closed. This has occurred even in households where the father was out of work and the mother employed. The labour market consequences of the increased burden from unpaid care work could emerge over time, as women opt for working arrangements that often translate into slower career progression and wage growth – such as part-time, or more flexible jobs with shorter commutes.

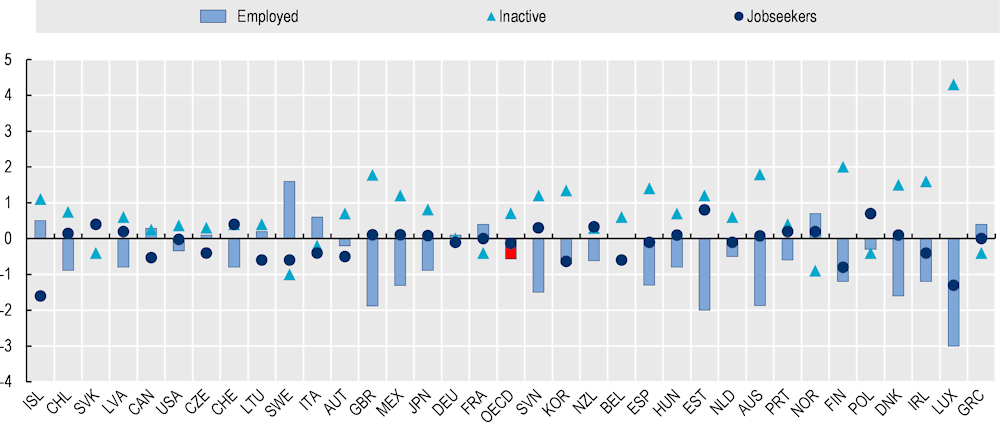

Young people have recovered some of the lost ground at the start of the pandemic but are still lagging behind older adults. Youth employment rate is still below pre‑crisis levels in over half of the countries. The protracted joblessness experienced by many young people over the past two years can have repercussions on their career prospects and the quality of the jobs they obtain. However, data from Q1 2022 show no common increases in the share on temporary contracts across countries despite the heightened economic uncertainty of recent times.

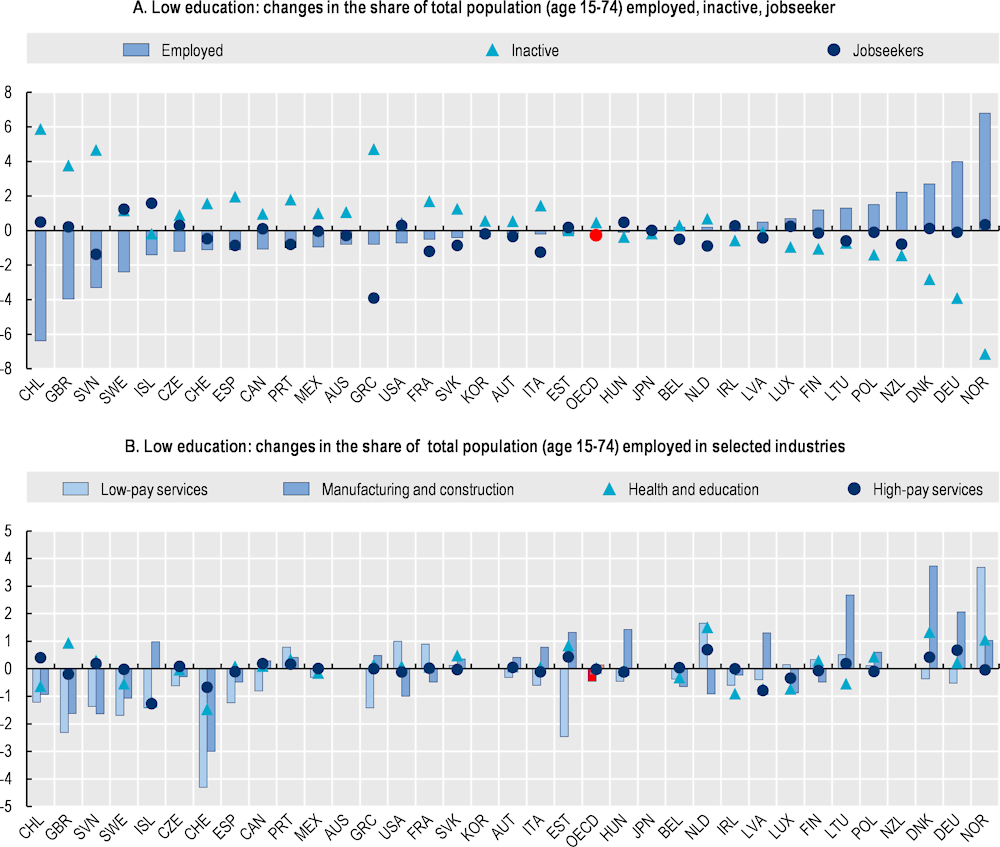

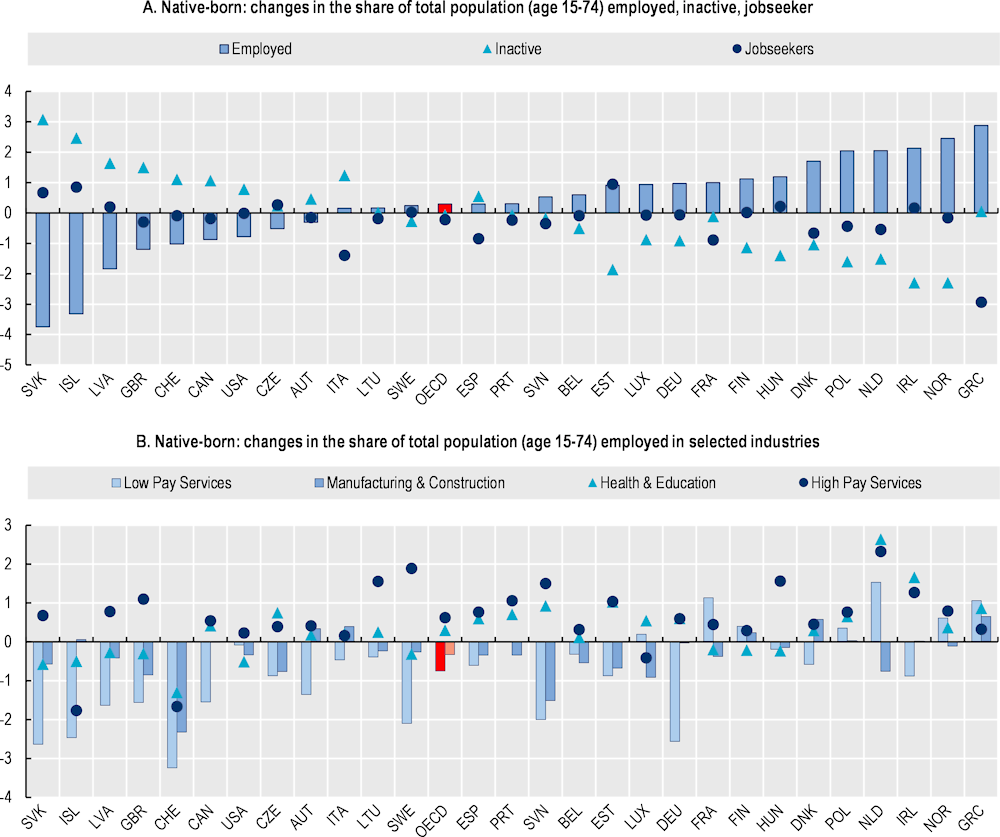

Across the OECD, the employment rate of highly educated workers was slightly above pre‑crisis levels in Q1 2022, while that of low and medium educated workers had not fully recovered yet. Across countries, the decline in employment for workers with less than tertiary education was mostly associated with an increase in inactivity rather than unemployment.

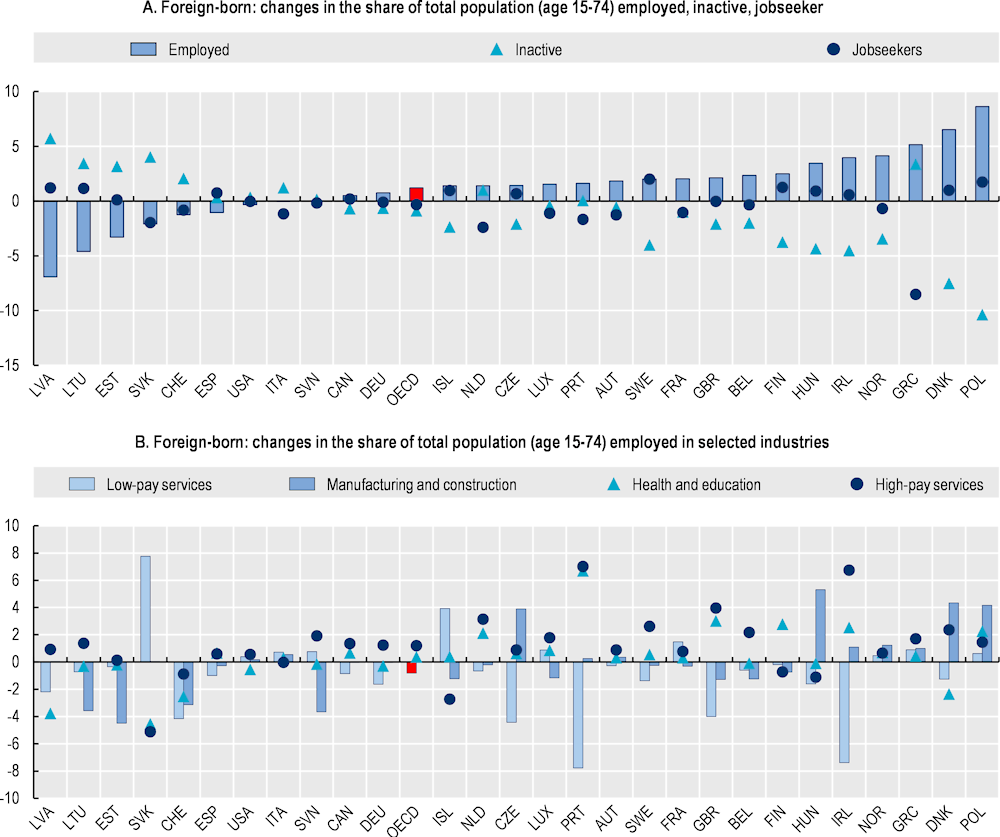

By Q1 2022, on average across OECD countries, the employment gap between native‑born and migrants had narrowed relative to pre‑crisis levels after its initial widening in 2020. However, in seven of the 28 countries with available data, migrants’ employment was still below pre‑crisis levels in Q1 2022 by an average of 2.9 percentage points. In most of these countries, the employment gap between the native‑born and migrants widened – on average by 1.9 percentage points.

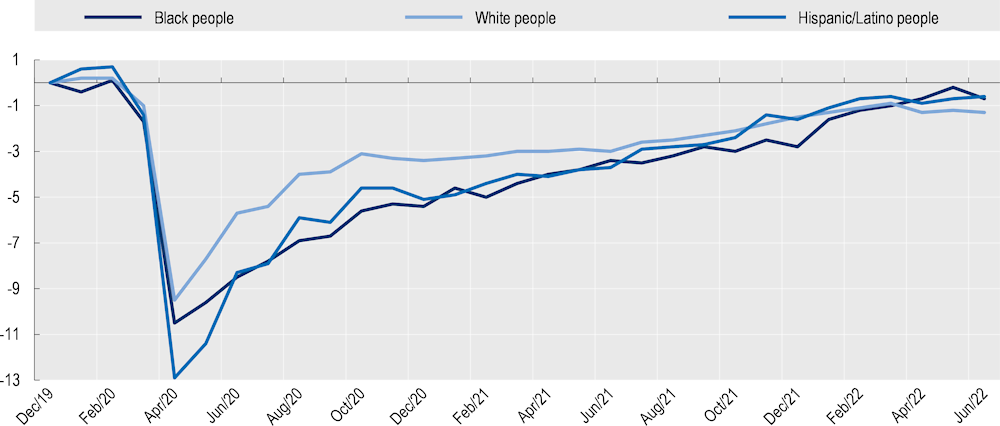

Few countries collect data which allow the impact of the crisis on racial/ethnic minorities to be assessed. In the United States, the United Kingdom, Latvia, and Estonia, racial/ethnic minorities were hit harder by the crisis and experienced a slower recovery. In Canada and Denmark, racial/ethnic minorities saw their labour market outcomes deteriorate more at the beginning of the crisis, but recovered in the successive months. In New Zealand, racial/ethnic minorities have benefited from the recovery more than the largest racial/ethnic group, reducing their employment gap in Q4 2021 relative to Q4 2019.

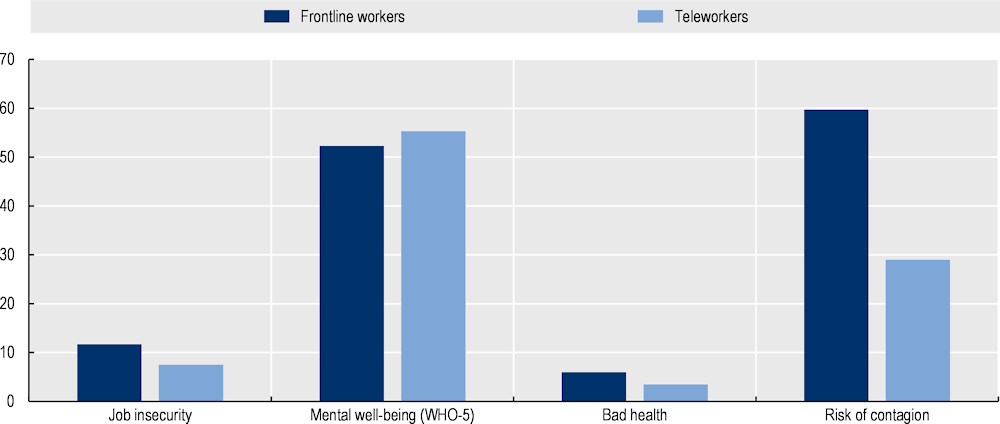

Frontline workers – who continued to work in their physical workplace and in proximity of other people during the pandemic – are disproportionately young, low educated, migrants, racial/ethnic minorities and employed in low-paid occupations. During the crisis, they reported more job insecurity, and lower overall health and mental well-being. Evidence show that they were also much more likely than other workers to become infected with COVID‑19.

Introduction

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is first and foremost a human tragedy with many losses of innocent lives and huge economic and social consequences including the millions who fled their country to escape violence and hunger. The war has also sent shockwaves through the world economy. Europe has seen the largest and fastest growing inflow of refugees since World War II as millions left Ukraine. The economic fallout of the war is threatening the strength of the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis which had been surprisingly robust till the early months of 2022 – in many countries supported by massive recovery plans.1

The impact of the war on energy, food, and commodity markets is adding to the significant inflationary pressures that had already emerged at the end of 2021 because of supply chain disruptions. In the first half of 2022, inflation reached levels not seen in decades in many OECD countries eroding workers’ living standards as nominal wage growth remained generally modest despite the tight labour markets. The impact of inflation is felt more by the same lower-income households which have already borne the brunt of the COVID‑19 crisis.

The economic fallout of the war in Ukraine threatens the strength of the economic recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis. However, even before the new shock and uncertainty introduced by the war, the labour market recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis appeared uneven across countries. The impact of the pandemic continues to shape employment dynamics across industries, which in turn affect the fortunes of the groups of workers that are more likely to work in them. While some of the initial unequal impact of the crisis across workers has been reabsorbed, young people, workers without tertiary education, and racial/ethnic minorities have been lagging behind in the recovery in many countries.

This chapter provides an examination of the latest developments across labour markets in the OECD and is organised as follows. Section 1.1 reviews the latest labour market developments across the OECD. Section 1.2 assesses the progress made in the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis till the first quarter of 2022, when the new crisis generated by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Section 1.3 reviews employment developments since the onset of the COVID‑19 crisis across industries, laying the ground for Section 1.4 to review the progress made by different socio‑economic groups during the recovery. Finally, Section 1.5 describes the labour market experience during the COVID‑19 crisis of frontline workers.

1.1. The economic fallout of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine threatens the strength of the economic recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis

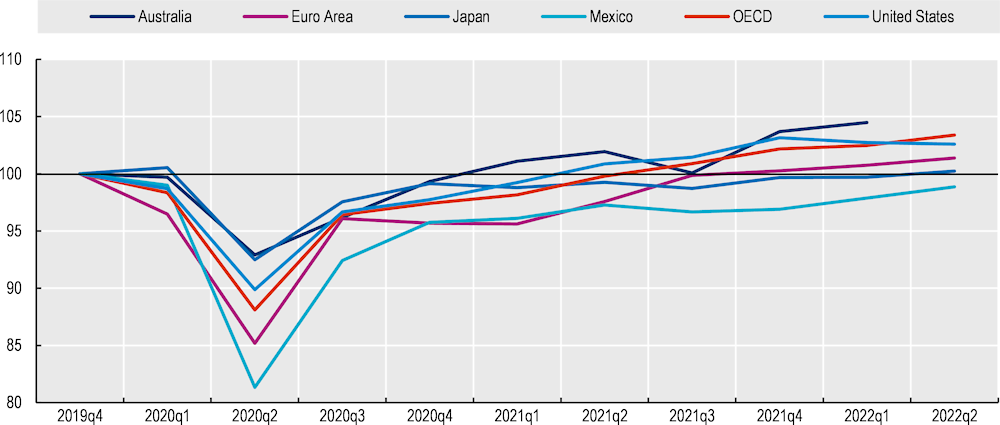

The economic recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis has been faster than expected thanks to the prompt and massive policy support for firms and household deployed throughout the crisis and the rapid rollout of effective vaccines (OECD, 2021[1]). OECD output returned to pre‑crisis levels already in Q3 2021 and continued to grow – albeit at slower pace – into the second quarter of 2022, climbing to 3.4 percentage points above its Q4 2019 level. The economic disruptions from the wave of the pandemic driven by the Omicron variant in late 2021 and the early months of 2022 generally proved mild in most countries, despite some weakness in the United States and Japan, where GDP declined in Q1 2022, and the Euro area, where growth slowed. Preliminary data for Q2 2022 suggests that GDP grew in the Euro Area, Mexico and Japan but contracted slightly in the United States – with positive growth recorded for the OECD as a whole.

The recovery in GDP was uneven across OECD countries (Figure 1.1). In Q1 2022, GDP remained below pre‑pandemic levels in eight countries – with output in Iceland, Spain and Mexico more than 1 percentage points below the Q4 2019 reference level. By contrast, GDP was at least 2.5 percentage points above pre‑pandemic levels in 22 countries, with particularly large gains in Ireland, Chile, Colombia, Türkiye, Israel, and Poland.

Figure 1.1. GDP for the OECD as whole returned to pre‑pandemic levels by Q3 2021, but growth slowed down at the start of 2022

Note: Euro Area refers to the 19 EU member states using the euro as their currency.

Source: OECD National Accounts Database.

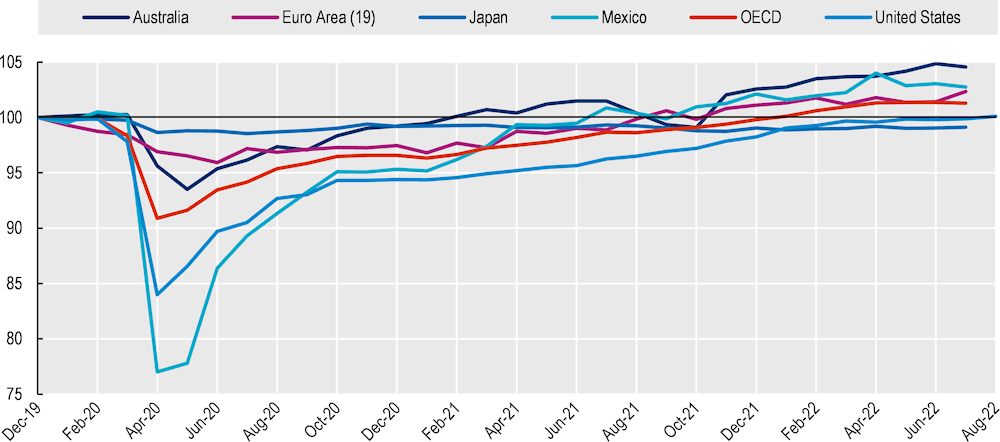

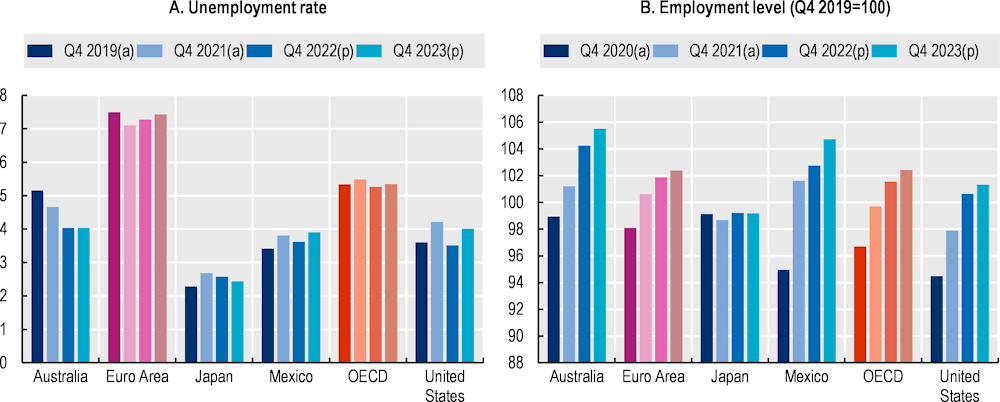

As the economy recovered, total employment in the OECD returned to pre‑crisis levels at the end of 2021 and continued its growth – albeit at a slower pace – into the first half of 2022, reaching a level 1.3% higher than before the crisis in July 2022 (Figure 1.2). Employment growth was particularly strong in Australia – where in July 2022 employment was 4.6% higher than at the end of 2019 – and Mexico – where in July 2022 employment was about 4.5% above its pre‑crisis level. Employment recovery was less pronounced in Japan – where employment was 1% lower than pre-crisis in July 2022 - and in the United States – where employment reached pre-crisis levels in August 2022. In the Euro Area, employment growth slowed down in the spring of 2022, and total employment reached a level around 2.3% higher than before the crisis in July 2022.

Figure 1.2. Employment levels since the onset on the COVID‑19 crisis

Note: Monthly employment figures for the OECD average, Euro Area (19) and Mexico are estimates derived from the OECD Unemployment Statistics estimated as the unemployment level times one minus the unemployment rate, and rescaled on the LFS-based quarterly employment figures.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Statistics for Australia, Japan, Mexico and the United States. OECD estimates based on the OECD Monthly Unemployment Statistics for the OECD average, Euro Area (19) and Mexico.

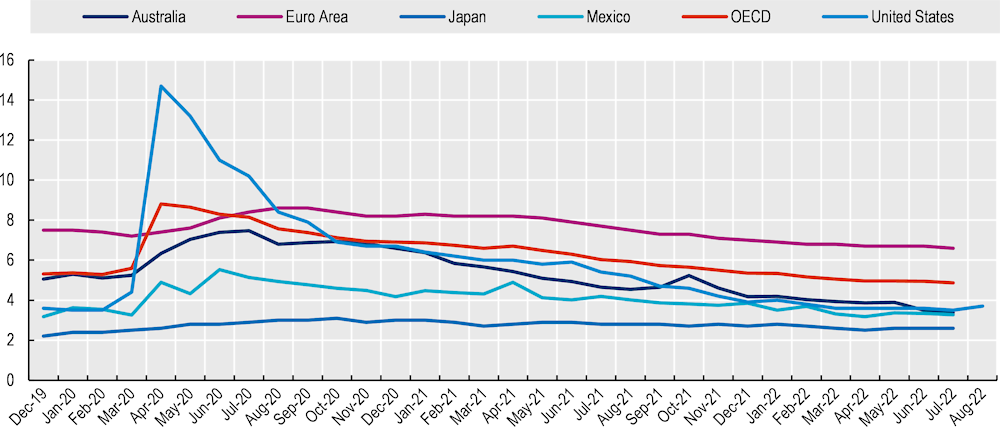

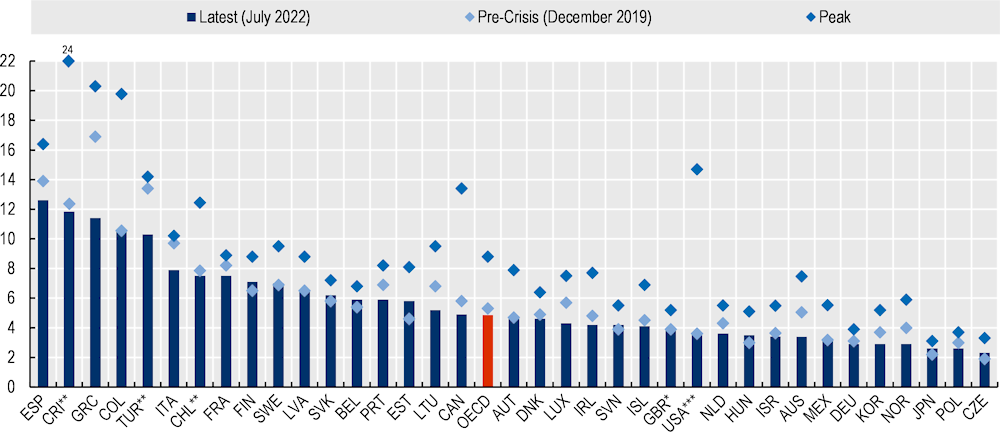

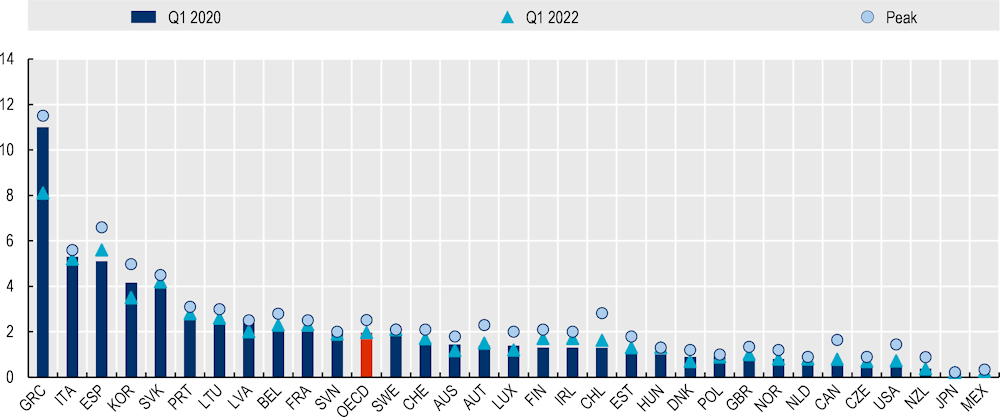

The OECD unemployment rate gradually fell from its peak of 8.8% in April 2020 and stabilised in the first months of 2022. In July 2022, the OECD unemployment rate stood at 4.9%, slightly below the 5.3% value recorded in December 2019 (Figure 1.3). In July 2022, unemployment was below pre‑crisis levels in 24 countries, and above that level by more than 0.5 percentage points only in Finland and Estonia. The peak increase in unemployment rate differed substantially across countries: unemployment increased by a larger amount and more quickly in countries that made limited use of job retentions schemes such as the United States, Colombia, Costa Rica and Chile. However, by early 2022 the unemployment rate had returned close to its pre‑crisis levels in all countries (Figure 1.4).2 The reliance on unemployment compensation does not necessarily imply that workers in those countries were worse off compared to workers in countries with job retentions schemes. For example, the United States significantly boosted and expanded the cash support and eligibility criteria during the first year and a half of the pandemic.

Figure 1.3. The OECD unemployment rate also returned to pre‑pandemic levels by the end of 2021

Note: Euro Area refers to the 19 EU member states using the euro as their currency.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Statistics.

Figure 1.4. Unemployment rate: Pre‑crisis, peak, and most recent

Note: For countries marked with * the latest data refer to May 2022, for those marked with ** to June 2022, and for those marked with *** to August 2022.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Statistics.

1.1.1. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine generated new adverse shocks and increased the uncertainty of the short-term outlook

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has generated a humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people and caused a new set of adverse economic shocks.3 Commodity prices have risen substantially, reflecting the importance of supply from Russia and Ukraine in many markets, adding to inflationary pressures and hitting real incomes, particularly for the most vulnerable households. Supply-side pressures have also intensified as a result of the conflict, as well as the impact of continued shutdowns in major cities and ports in China due to the zero-COVID policy.

More than 6.5 million people have already been forced to flee Ukraine to other countries in Europe, and an even greater number have been displaced within the country.4 The number of people who have already fled Ukraine since the start of the war is several times greater than the annual flow of asylum-seekers into Europe at the height of the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015‑16. The refugee flows caused by the war will result in additional public expenditure in the short-term in host countries, although this will be offset over time as refugees enter the labour force. Box 1.1 reviews lessons learned from recent experiences from across the OECD that can help facilitate the process of integrating the refugees into the labour market of the host countries.

Box 1.1. Good principles for the support and integration of refugees

Following the large inflow of humanitarian migrants to OECD countries in 2015, and building on its longstanding work on refugee integration, the OECD established a number of lessons of good practice from OECD countries (OECD, 2016[2]). The following summarises the most relevant lessons that can help the process of integration of the millions who were forcedly displaced from Ukraine to OECD countries (OECD, 2022[3]).

1. Provide reception services as soon as possible

While there remains uncertainty about the actual length of the forced displacement, it is key that the skills of those concerned are not left idle for long. Experiences of many OECD countries suggest, for example, that early labour market entry soon after arrival is one of the best predictors of future outcomes.

2. Factor employment prospects into dispersal policies

Many governments seek to distribute – or disperse – refugees in locations evenly across the country. This is also the case for refugees from Ukraine. At the same time, local labour market conditions on arrival are a crucial determinant of lasting integration. In areas where jobs are readily available, labour market integration is faster and easier. It is thus important to avoid situations in which new arrivals are placed in areas where cheap housing is available but labour market conditions are poor.

3. Promote equal access to services across the country

The Temporary Protection Directive sets minimum standards for reception of refugees from Ukraine in EU countries. However, there are also sharp differences within countries, with special services available in some regions and not in others. So where refugees are eventually settled – something over which they seldom have any control – affects their integration prospects. To limit disparities, it is important to: i) build the necessary expertise in local authorities; ii) ensure adequate financial support and the right incentives; iii) pool resources between local authorities and to iv) set common standards and monitor how local authorities live up to them.

4. Record and assess foreign qualifications, work experience and skills

Initial data suggest that the average education level of the displaced from Ukraine is high, with the majority having tertiary education. Most have also worked in Ukraine. In spite of similarities, the education, training system and labour market in Ukraine is quite different from that in many host countries – or at least, employers are not familiar with it. To make sure that their skills are well used and build further, it is essential to take stock of the skills that they bring with them. To that end, it is important that the qualifications and skills of refugees from Ukraine are assessed and recognised swiftly and effectively.

5. Take into account the diversity of needs and develop tailor-made approaches

While many refugees from Ukraine are women with tertiary education and their children, there remains considerable diversity regarding skills, family situations, special needs and resources. Such diversity in individual profiles makes integration challenging, as there is obviously no “one‑size‑fits-all” integration trajectory. Reception offers need to account for the specificities of this population, including with respect to childcare.

6. Identify mental and physical health issues early and provide adequate support

A considerable percentage of refugees suffer from psychological complaints like anxiety and depression as a consequence of the traumatic, and often violent, experiences they have endured back in Ukraine. At the same time, poor physical health as a result of abuse and injuries are also common. Such health issues can be a fundamental obstacle to integration, as they impinge on virtually all areas of life and shape the ability to enter employment, learn the host country’s languages, interact with public institutions, and do well in school. Host countries must speedily diagnose and address specific health concerns in ways that take into consideration their particular needs.

7. Build on civil society to integrate humanitarian migrants

The unprecedented scale of the displacement from Ukraine has meant that public reception and support capacities were quickly stretched to the limit, especially in the neighbouring countries of Ukraine which bore the brunt of the displacement from Ukraine but had little prior experience with refugee situations. As a result, there has been an unprecedented solidarity response by the civil society. More generally, civil society often steps in where public policy does not tread or cannot be up scaled sufficiently or quickly. Such support is also crucial for social cohesion.

Note: Box prepared by Thomas Liebig from the International Migration Division of the Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Department of the OECD.

The OECD economic projections from June 2022 point to a slowdown in global GDP growth as a results of the economic fallout from Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Indeed, global GDP growth is now projected to be around 3.0% in 2022 – against the previous projection of 4.5% from December 2019 – and to remain at a similar pace in 2023 (OECD, 2022[4]).

The normalisation of labour markets is projected to continue during 2022‑23, despite the new negative shock of the war in Ukraine, which nevertheless makes the outlook more uncertain (OECD, 2022[4]). As the public health situation improves further, based on rising vaccination rates and improved COVID‑19 treatments, labour force participation is projected to increase in almost all economies. Across the OECD, as seen in Figure 1.2, total employment returned to its pre‑crisis levels already at the end of 2021, but its growth is now expected to slow. In particular, total employment in the OECD is projected to be above its Q4 2019 level by 1.5 percentage points by the end of 2022 and by 2.5 percentage points by the end of 2023. The unemployment rate is expected to stabilise remaining just above 5% both at the end of 2022 and 2023 (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Employment growth is projected to slow down and the unemployment rate to stabilise over 2022 and 2023

Note: (a) Actual value. (p) OECD projection. Euro Area refers to the 17 EU member states using the euro as their currency, which are also OECD member states.

Source: OECD (2022[4]), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 1, https://doi.org/10.1787/62d0ca31-en.

There are a number of prominent downside risks that could lead to a further deterioration of the economic situation with potential repercussions on labour markets. These risks are linked in particular to an abrupt interruption of flows of oil and gas from Russia to Europe, stronger disruptions to global supply chains or financial contagion. Inflationary pressures could also prove stronger than expected, with risks that inflation expectations move up further away from central bank objectives and become reflected in faster wage growth amidst tight labour markets. Sharp changes in policy interest rates could also slow growth by more than projected. Risks also remain from the evolution of the COVID‑19 pandemic: new and more aggressive or contagious variants may emerge, while the application of zero-COVID‑19 policies in large economies like China has the potential to sap global demand and disrupt supply for some time to come.

1.2. The labour market recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis was stronger than expected but uneven across countries

The labour market indicators for the first quarter of 2022 – which were only marginally affected by the consequences of the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – show that the labour market recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis was generally stronger than expected, but some countries were lagging behind.

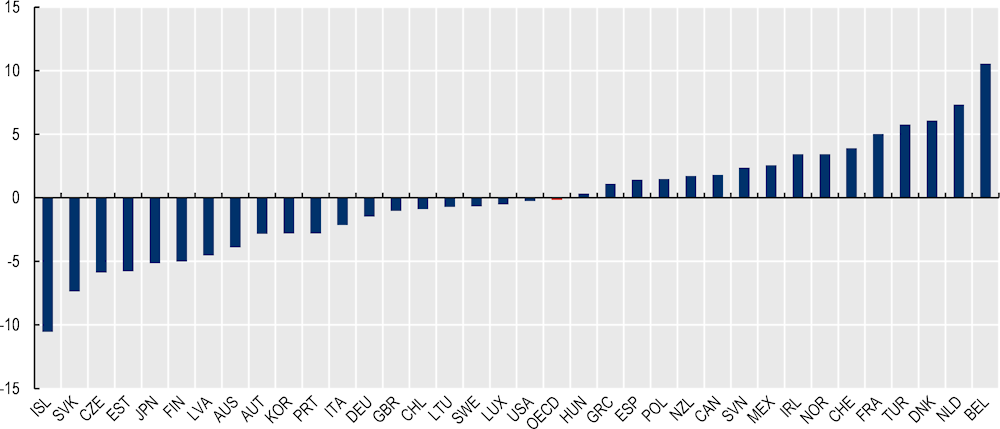

1.2.1. Hours show an incomplete recovery in many countries, and employment and inactivity rates paint a picture that varies across countries

At the beginning of 2022, total hours worked remained below pre‑crisis levels in many countries. On average across the OECD countries with data available, hours were 0.2% lower in Q1 2022 compared to in Q1 2019 (Figure 1.6).5 The recovery in total hours worked was slowed down or even set back in some countries as new restrictions were adopted in the final quarter of 2021 as the Omicron variant drove a new aggressive wave of the pandemic. In early 2022, total hours worked remained below pre‑crisis levels in 19 of the 35 countries with data available. In Finland, Japan, Estonia, the Check Republic, the Slovak Republic, and Iceland the gap was particularly large, exceeding 5%.

Figure 1.6. In Q1 2022, hours worked were still below pre‑crisis levels in most countries

Note: The figure reports percentage change in total hours worked relative to Q1 2019. See the main text for a discussion of seasonality effects in these results. To compute the percentage change for GBR, seasonally adjusted data produced by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) was used. OECD indicates the unweighted average of the countries shown.

Source: EU-LFS for European countries, CPS for the United States, for GBR ONS, Canadian LFS, ENE for Chile, ENOE and ETOE for Mexico, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Statistics New Zealand, Statistics Bureau of Japan (Labour Force Survey), Statistics Korea (Economically Active Population Survey).

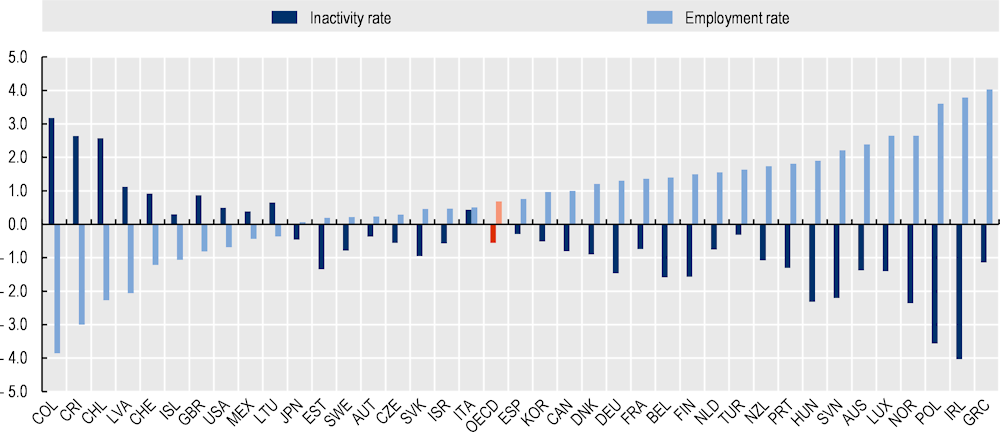

At the start of 2022, employment and inactivity rates had generally improved relative to the pre‑crisis situation, but some countries were lagging behind

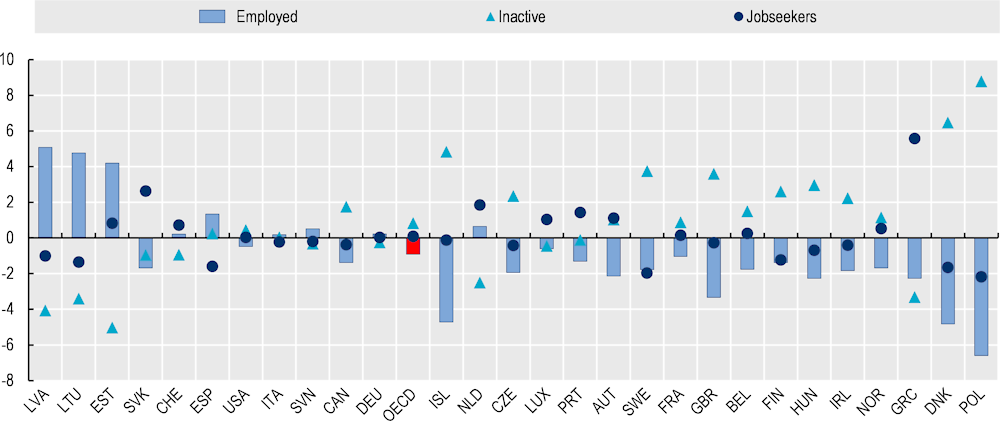

Employment and inactivity rates in early 2022 had generally improved relative to pre‑crisis levels, but some countries were still lagging behind (Figure 1.7). According to the most recent available data (Q1 2022), the employment rate of the working age population was above pre‑pandemic level in 28 of the 38 OECD countries by an average of 1.5 percentage points. In the remaining ten, the employment rate was below its Q4 2019 level by an average of 1.6 percentage points, with the gap exceeding 2 percentage points in Colombia, Costa Rica, Chile, and Latvia.

The initial increase in inactivity that took place in all countries in 2020, as the pandemic discouraged active job search (OECD, 2021[1]), had largely been reabsorbed by early 2022. In the most recent data, inactivity rates were lower than just before the crisis by an average of 1.3 percentage points in 27 OECD countries. In the other 11 countries, inactivity was above pre‑crisis levels by an average of 1.2 percentage points with the largest increases in excess of 2 percentage points in Colombia, Costa Rica, and Chile.

Figure 1.7. Employment and inactivity rates improved relative to the pre‑crisis situation in most countries

Note: Working age population includes all those aged 15 to 64.

Source: OECD Short-term Labour Market Statistics.

Long-term unemployment is higher than before the crisis in many countries but generally receding

At the onset of the crisis, long-term unemployment (i.e. 12 months or more) edged down in several countries (OECD, 2021[5]). This was largely the result of a fall in job search activity in the context of the initial lockdowns that were often accompanied by the suspension of job search obligations, leading to many people being classified as inactive rather than unemployed. Over the course of 2021, however, as job search picked up again, long-term unemployment increased in many countries despite the general improvement in labour market conditions. By Q1 2022, long-term unemployment was still above pre‑crisis levels but generally receding in most countries (Figure 1.8).6 In particular, the long-term unemployment rate was above pre‑crisis levels in 20 of the 32 countries with data available, but the OECD average had already returned to pre‑crisis levels. The increases were above 50% in the United Sates (from 0.5% to 0.7%) and Canada (from 0.5% to 0.8%) – both countries that featured comparatively low levels of long-term unemployment before the start of the crisis.7 Declines in excess of 15% in the long-term unemployment rates were recorded in Greece, South Korea, Latvia, Australia, and Denmark.

Figure 1.8. By Q1 2022, long-term unemployment was higher than before the COVID‑19 crisis in many countries, but generally receding

Note: OECD is the unweighted average of countries shown. Germany and Iceland are not included because data for those countries is missing for Q1 2020. See the main text for a discussion of a break in Q1 2021 in the series provided by Eurostat.

Source: EU-LFS for European countries, CPS for the United States, UK LFS, Canadian LFS, ENE for Chile, ENOE and ETOE for Mexico, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Statistics New Zealand, Statistics Bureau of Japan (Labour Force Survey), Statistics Korea (Economically Active Population Survey).

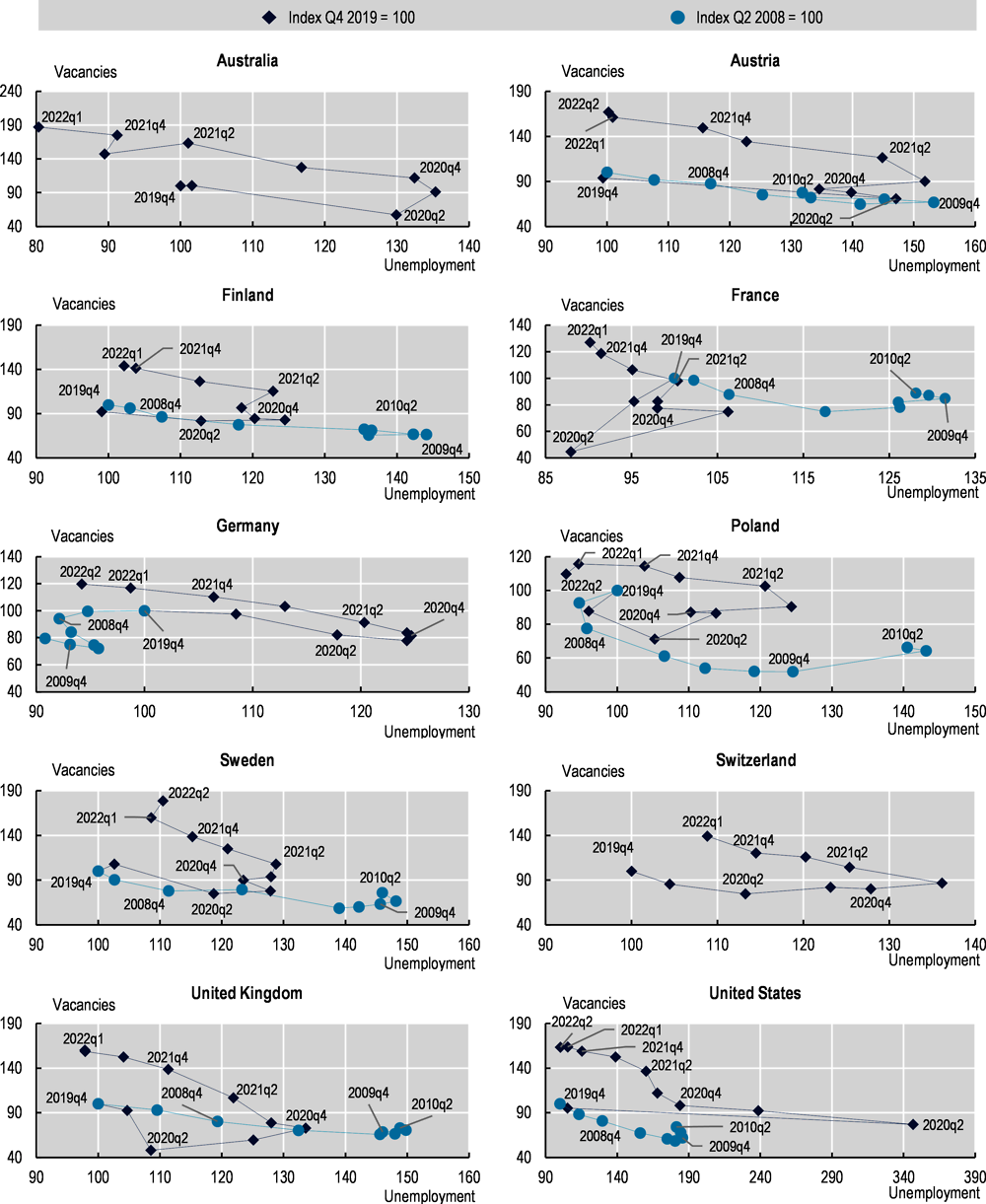

1.2.2. A surge in vacancies has led to a fast tightening of labour markets with widespread reports of labour shortages

The unprecedented rebound of economic activity recorded in many countries in 2021 was coupled with a surge in labour demand, as indicated by the steep increase in labour vacancies in many countries (Figure 1.9). Indeed, in most countries considered, vacancies reached pre‑crisis levels already one year after the on-set of the crisis in Q2 2021 and then continued to increase steadily for the remainder of the year. In the first quarter of 2022, the growth of vacancies generally slowed down, but they remained at historically high levels in many countries. By Q1 2022, vacancies were at least 50% higher than before the crisis in Australia, Austria, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Vacancies increased relatively less in Germany and Poland, still reaching a level just under 20% higher than before the crisis by Q1 2022. Among the countries not included in Figure 1.9, vacancies reached record highs in in Canada (80% higher in Q4 2021 than in Q4 2019)8 and New Zealand (+31% in March 2022 relative to two years earlier).9 In Italy, the vacancy rate reached record levels in the second half of 2021, stabilising around 1.9 in Q1 2022 (ISTAT, 2022[6]).10 Also in Q1 2022, vacancies were at least 40% higher than before the crisis in Luxembourg and Portugal, and only slightly above pre‑crisis levels in Hungary and the Czech Republic.11 Data for Q2 2022 are only available for a few countries at the time of writing, but generally confirm that vacancies remained high throughout the first half of the year. By contrast, two years after the start of the Great Financial Crisis, vacancies remained depressed in all countries reported in Figure 1.9 – highlighting the profound difference in the nature of the two crises.

Figure 1.9. Labour demand has increased very quickly

Note: The number of job vacancies and unemployment in Q2 2008 are indexed to 100 for the period of Q2 2008 to Q2 2010, and those in Q4 2019 are indexed for the period of Q4 2019 onwards. The Q2 2022 data are available for Austria, Germany, Poland, Sweden and the United States, while Q1 2022 is the most up-to-date for the remaining countries. All values are seasonally adjusted. For Switzerland, job vacancy data from the Federal Statistical Office are used and are not seasonally adjusted.

Source: OECD Short Term Labour Market Statistics, Job Statistics (Federal Statistical Office of Switzerland).

Two main factors have likely contributed to the widespread surge in vacancies. First, vacancies rebounded after two or three quarters of unprecedented depression in 2020 when turnover in firms had slowed down considerably due to the health situation. As economies reopened and uncertainty surrounding the economic and health situation decreased over the course of 2021, firms and workers likely pursued (and continue to pursue) hiring and job-moving decisions that had been placed on hold. In countries that made limited use of job retention schemes to preserve jobs – like the United States – the rebound was particularly robust due to the need to re‑fill temporarily closed positions after the various waves of the pandemic.

A second factor fuelling the surge in vacancies is the strong growth in product and service demand of the second half of 2021 and early months of 2022. The generous support deployed by many countries during the crisis helped keep many firms in operation and preserve the spending power of many consumers, thus creating the conditions for a jump-start of the economy as restrictions became progressively more targeted and vaccination rates quickly increased. The strong economic recovery was then fuelled by massive recovery plans in many countries. In addition, demand was also supported by the savings accumulated by many consumers in the first part of the crisis as they reduced spending on services in particular due to the restrictions in place or out of fear of contagion (McGregor, Suphaphiphat and Toscani, 2022[7]).

As already seen in Figure 1.3, unemployment rates fell throughout 2021, but the speed of the decline did not match that of the surge in vacancies. Indeed, while vacancies were well above pre‑crisis levels by early 2022, unemployment was instead close to pre‑crisis levels in all countries. While vacancies do typically grow faster than unemployment falls during recoveries, the unprecedented speed of the vacancy surge during the COVID‑19 recovery means that labour market tightness increased in most countries to levels typically seen much later in the cycle (European Central Bank, 2019[8]). Also, many of the Beveridge curves reported in Figure 1.9 – which capture the negative relationship between unemployment and vacancies – exhibit a pronounced outward shift in the second half of 2021, signalling a decrease in the matching efficiency of labour markets. Two notable exceptions are France and Germany where the increase in vacancies has been less pronounced and unemployment fell below pre‑pandemic levels at the start of 2022.

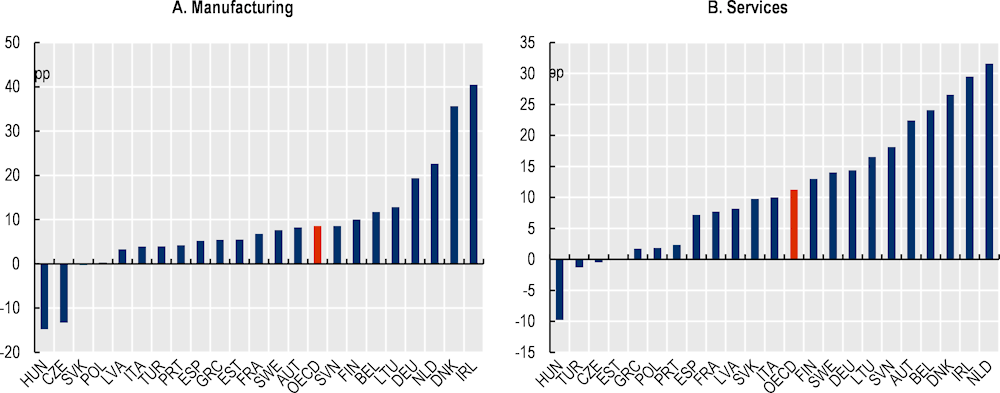

Reports of labour shortages by firms are widespread across sectors

The increase in tightness in the labour market and the decrease in matching efficiency is clearly reflected in the growth in the number of firms reporting production constraints from labour shortages (Figure 1.10). In Q2 2022, the proportion of firms in manufacturing that lamented labour shortages was, on average, 8.5 percentage points higher (at about 26%) than before the crisis in the 22 OECD countries that are members of the European Union and Türkiye. In services, the proportion of firms reporting labour shortages was 27.5% on average across the same countries – or more than 11 percentage points higher than before the crisis. Among these countries, reports of labour shortages did not increase only in Hungary, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic (in manufacturing) and Türkiye (in services). The proportion of businesses reporting labour as the primary constraint was also at a record high in New Zealand in January 2022.12 In Canada, in the first quarter of 2022, 37% of firms expected to face labour shortages in the coming three months.13 An economy-wide indicator of labour shortages in Germany compiled by the Institute of Employment Research (IAB) grew above pre‑crisis levels in early 2022, after rebounding from the low levels of 2020 and early 2021.14

Figure 1.10. The share of firms reporting production constraints from labour shortages has increased across Europe

Note: OECD is an unweighted average of countries shown above. Data in the second quarter of the calendar year are collected in the first two to three weeks of April. For instance, the Q2 2022 data were collected in the first two to three weeks of April 2022. Firm responses are seasonally adjusted.

Source: European Commission Business and Consumer Survey.

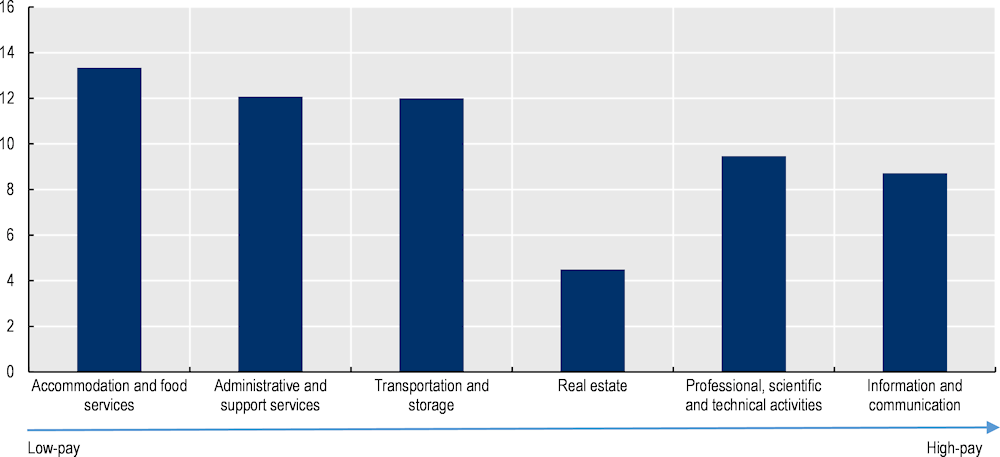

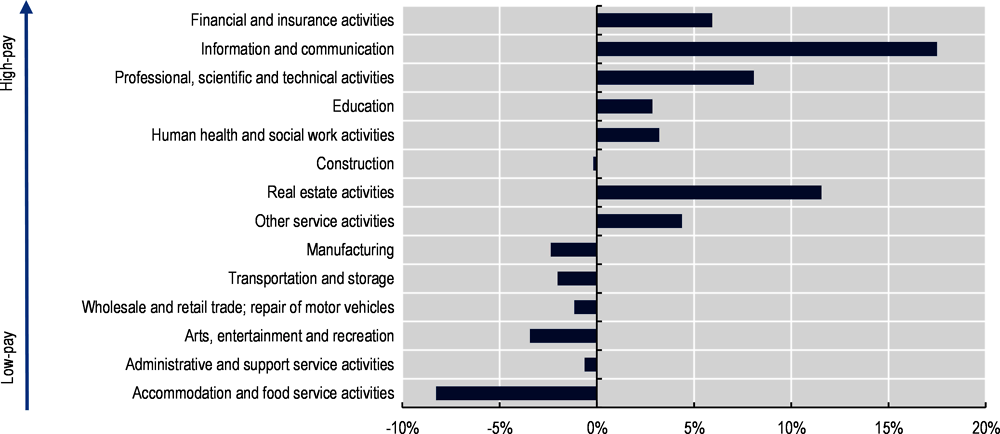

EU-level data by finer sectors indicate that recruiting difficulties have been widespread across sectors in recent months, but they are particularly pronounced in relatively low-pay sectors (Figure 1.11). For example, the share of firms reporting production constraints from labour shortages increased by 13 percentage points relative to its pre‑crisis level of 20% in accommodation and food services and by 12 percentage points (relative to a pre‑crisis level of 23%) in administrative and support services. Firms in accommodation and food services have also been more likely to report labour shortages in the first few months of 2022 in the United Kingdom as well (37% vs an average of 14% in April 2022).15 In Canada, the proportion of firms expecting labour shortages in the first quarter of 2022 was 65% in the accommodation and food services vs an average of 37% across the economy.16

Figure 1.11. Difficulties in recruiting are widespread but particularly acute in low-pay sectors

Note: From left to right, the bars are arranged from low-pay sectors to high-pay sectors. Industries are ranked by the median wage in 2019 in the European Structure of Earnings Survey (SES). For more details, see the note of Figure 1.16. The percentage of firms reporting labour shortages as a business constraint in each sub-sector of the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE) Rev.2 is aggregated to the broad NACE Rev.2 sector level, based on employment weights at the sub-sector level for those aged 15‑64. Both firm responses and employment weights are seasonally adjusted. The Q2 2022 data were collected in the first two to three weeks of April 2022.

Source: The Joint Harmonised EU Services (European Commission), Employment by sex, age and detailed economic activity from 2008 onwards, NACE Rev.2 two‑digit level (Eurostat).

In some countries, quits have increased along with labour market tightness

In the United States, after hovering below pre‑pandemic levels for over a year, quits reached record highs in the second half of 2021 and then remained high in the first few months of 2022, prompting talk of a “Great Resignation”.17 Increases in quits were recorded in almost all sectors, but – relative to the size of the sectors – they were particularly pronounced in manufacturing, retail trade and finance and insurance.18 The evidence on which workers have been quitting varies somewhat depending on the methodology and timing of the survey. A survey covering 4 000 US companies in the summer of 2021 suggested that quits increased more among prime‑age workers (Cook, 2021[9]). A recent survey by the Pew Research Center (Parker and Horowitz, 2022[10]) found that workers under the age of 29 were more likely than all other age groups to have quit their job at some point in 2021, but the study does not provide pre‑crisis baseline figures to assess which groups saw the largest increases. According to this survey, men and women were equally likely to have quit their jobs in 2021, but quits were more frequent among racial/ethnic minorities groups.

There is no indication that the increase in quits is driven by people falling out of the labour force. Indeed, the employment-to-population ratio in the United States continued its steady growth in the first quarter of 2022 even as quit rates remain elevated and GDP growth turned negative (see Section 1.1).19 In addition, at the end of 2021 hiring rates were higher than quit rates in all industries, including in low-pay services (Gould, 2022[11]). This suggests high mobility within sectors in a tight labour market, rather than significant outflows from specific industries because of a change in workers’ preferences. A survey by the Pew Research Center finds that the vast majority of those who quit their job in 2021 report having found a new job without significant difficulties and with similar or better conditions than their previous employment (Parker and Horowitz, 2022[10]).

Beyond the United States, the evidence of a significant increase in quits is limited. In the United Kingdom, job-to-job transitions remained below pre‑pandemic levels until the summer of 2021 and then reached a record high in Q4, at a level about 30% higher than in Q4 2019 driven by an increase in resignations. In Q1 2022, job-to-job moves declined slightly, while still remaining over 20% higher than in the same quarter of 2019.20 However, there was no indication of an increase in cross-sectoral mobility that would be expected if the pandemic had motivated workers to leave certain sectors in particular.21 In France, after a long depression, quits of permanent workers climbed above pre‑crisis levels in the third quarter of 2021 – driven by an increase among workers formerly on job retention schemes – and then remained elevated in the last quarter of the year.22,23 In Germany, however, there was no indication of an increase in quits relative to before the crisis at least until March 2021 (Rottger and Weber, 2021[12]). Similarly, in Australia, the proportion of businesses with open vacancies reporting the need to replace leaving employees was stable over the course of 2021. By February 2022, the figure stood at 79.7% – only 1 percentage point higher than just before the pandemic in February 2020.24

The fast tightening of labour markets is likely a consequence of the speed of the economic rebound

The increasing labour market tightness seen in many countries is likely mostly the result of the sheer speed of the surge in labour demand fuelled by the strong uptake in economic activity as economies reopened. The pervasiveness of reports of labour shortages across countries and sectors suggests that the current situation is not driven by the scarcity of a specific type of labour that could arise, for example, from the asymmetric impact of the crisis across sectors (see Section 1.3). In fact, recent studies have found that the mismatch between types of workers and the types of jobs available grew substantially at the onset of COVID‑19 crisis but was short-lived and generally smaller than during the Great Financial Crisis (Shibata and Pizzinelli, 2022[13]; Duval et al., 2022[14]). Instead, these studies suggests that the sluggish response of employment to the surge in vacancies in the second half of 2021 was in part explained by a contraction in labour supply of low skilled and older workers. Indeed, in the United States and the United Kingdom, the vacancy surge occurred even as inactivity rates remained above pre‑crisis levels. Another potential factor limiting the availability of labour overall might have been the protracted weakness of net migration in many countries. Preliminary evidence suggests that in Q3 2021 the overall size of the labour force in Europe was still below the levels that would have been expected given pre‑crisis trends largely due to the fact that net migration remained depressed (European Central Bank, 2022[15]).

The tightening of the labour market per se might stimulates job-to-job moves – as evidenced by the uptake in quits in some countries – and might encourage jobseekers to search for longer for better opportunities. The generous income support provided by many countries during the crisis might have helped jobseekers to prolong their search for better opportunities – though the evidence from the United States point to mostly small effects (Holzer, Hubbard and Strain, 2021[16]; Coombs et al., 2022[17]; Petrosky-Nadeau and Valletta, 2021[18]). The lingering pandemic might have made frontline low-paid jobs that typically involve direct contact with customers less appealing and might have accentuated the perception of the lower quality of these jobs. Pizzinelli and Shibata (2022[13]) argue that an increase hesitancy to return to these jobs might play a role in the United States and the United Kingdom.

In many sectors – both high and low skill – however the current exceptional circumstances exacerbate pre‑existing difficulties in recruiting workers. In their responses to an OECD questionnaire (see Chapter 2), over 70% of the countries reported that labour shortages were an issue in the long-term care and health sectors during the COVID‑19 crisis – with most indicating that the crisis has aggravated existing problems. Across Europe, reports of labour shortages had been steadily increasing in the aftermath of the financial crisis (Eurofound, 2021[19]). The Beveridge Curve of several countries had gradually shifted outwards after the Great Financial Crisis, signalling increasing difficulties in matching a large number of vacancies to a large number of unemployed because of skill mismatches or unsatisfactory working conditions (European Central Bank, 2019[8]). As the pandemic broke out in 2020, labour shortages were quickly aggravated in agriculture and in the health and ICT sectors in Europe (Eurofound, 2021[19]; Samek Lodovici et al., 2022[20]).

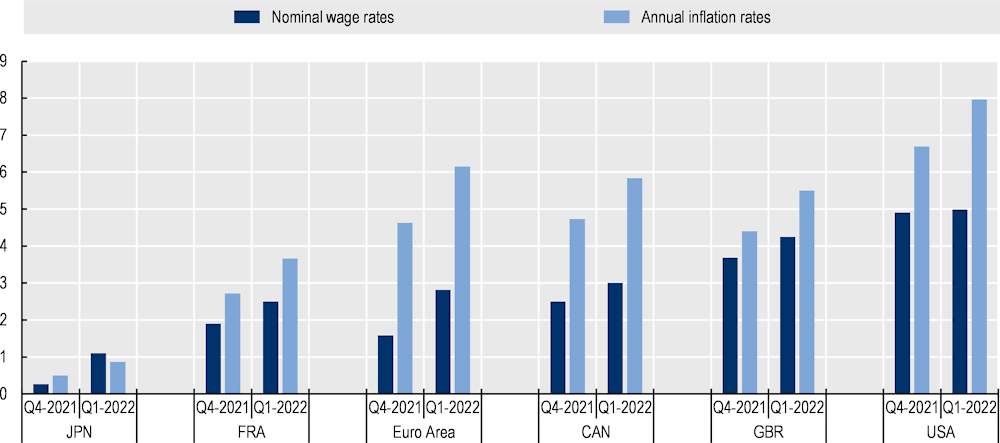

The coming months will help clarify if underneath the vacancy tide affecting all industries – new tensions are arising (or adding to pre‑existing ones) in specific industries linked to qualitative mismatches between labour demand and supply. As discussed below in Section 1.3, industries that have expanded since the onset of the crisis are very different from industries that have seen employment fall, pointing to a potential misalignment in skills between labour demand and the supply that has become available. Geographical mismatches could also be an issue if expanding and retreating sectors are located in different places and as result of changing consumption patterns (for example due to more online spending or to increases in teleworking that shifted some consumption away from urban centres). There is currently very little evidence of mismatches arising in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis. Preliminary evidence based on data for Australia, Spain, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Japan suggests that the problem is limited due to the fast rebound of the most-hardly hit sectors (Duval et al., 2022[14]). Finally, in addition to the pressures arising from changes that might have been triggered or accelerated by the pandemic per se, many countries intend to use their recovery plans to accelerate digitalisation and the transition towards a climate‑neutral economy – further accelerating structural transformations of the labour market which might also contribute to rising qualitative mismatches.

1.2.3. Despite tight labour markets, real wages are falling as high inflation exceeds modest nominal wage growth

Despite the strong labour markets, workers’ wages have declined in real terms in recent months. Indeed, while by the end of 2021 or early 2022 nominal wage growth reached high levels relative to pre‑pandemic levels in some countries, the nominal increases have generally remained well below the fast-growing inflation generated by increasing commodity prices (Figure 1.12).

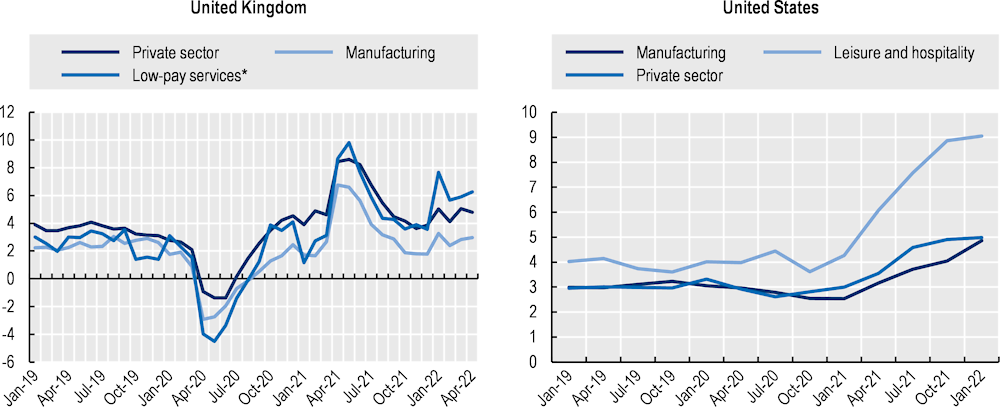

In the United States, nominal wage growth edged up already in the second half of 2021. Even so, real wages fell. Indeed, in the last quarter of 2021, nominal wage growth in the private sector reached 5% – about 2 percentage points higher than in the quarters just before the crisis – while inflation jumped to 6.7%. In the first quarter of 2022, annual nominal wage growth remained stable but inflation reached 8%. Nominal wage growth was particularly strong in leisure and hospitality, reaching 9% in Q1 2022 – in part as a result of increases in minimum wages implemented in a number of states and localities (Box 1.2) – while in the quarters before the start of the pandemic it had hovered around 4% (Figure 1.13).25

In Europe, the ECB index for negotiated wages in the Euro Area picked up slightly in the first quarter of 2022 (+2.8%) but remained well below the rate of inflation of 6.1%. In France, nominal gross hourly wages for non-managerial employees grew by 1.9% in Q4 2021 and 2.5% in Q1 2022, outpaced by inflation rates of 2.7% and 3.7% respectively. In Q1 2022, nominal wage growth was above average but still below inflation in two low-pay industries, retail and food and accommodation.26 In Canada, nominal hourly wage growth remained below pre‑pandemic levels for most of 2021 and reached 3% in the first quarter of 2022, remaining well below inflation at 5.8%. In the United Kingdom, growth in nominal average weekly earnings was below inflation both in Q4 2021 and Q1 2022 – but measures of pay including bonuses increased more in line with inflation. Data by sectors for the United Kingdom show similar patterns in wage changes between low-pay service sectors and the whole private sector until the end of 2021, but larger wage growth in low-pay sectors in the first months of 2022 (Figure 1.13).27 In Japan, the annual growth rate of total cash earnings was slightly below inflation in Q4 2019, but reached 1.1% in Q1 2022 against an inflation rate of 0.9%.

Figure 1.12. Nominal wage growth has generally remained below inflation

Notes: The measurement of nominal wage rates is not harmonised across countries.

Source: Average hourly earnings from the Survey of Employment, Payrolls, Hours (Statistics Canada), Euro Area 19 – Indicator of negotiated wage rates (European Central Bank), Salaire horaire de base des ouvriers et des employés from l’enquête trimestrielle sur l’activité et les conditions d’emploi de la main-d’œuvre (Direction de l’animation de la recherche, des études et des statistiques, France), Total cash earnings from the Monthly Labour Survey (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan), Average weekly earnings – regular pay: whole economy from the Monthly Wages and Salaries Survey (Office for National Statistics, United Kingdom), Employment Cost Index for wages and salaries for private industry workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States), OECD Key Short-Term Economic Indicators: Consumer Prices, Consumer Price Index (Statistics Bureau of Japan).

Figure 1.13. Annual nominal wage growth by sector

Note: * Low-pay services in the United Kingdom include Wholesaling, Retailing, Hotels and Restaurants.

Source: United Kingdom: Average Weekly earnings by sector – Office for National Statistics. United States: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Cost Index: Wages and salaries for Private industry workers, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Tight labour markets might help improve the working conditions of the most disadvantage groups, but high inflation is likely to continue to erode real wages in the months to come

A tight labour market might help improve working conditions in low-pay sectors. Indeed, as mentioned above, there is some evidence that nominal wage growth has been stronger in some low-pay sectors (see Figure 1.13) and Duval et al. (2022[14]) find that wages in low-pay sectors were more responsive to the increasing labour market tightness over the course of 2021. More generally, tight labour markets are associated with improvement in labour market outcomes for vulnerable groups in particular – both in terms of better working conditions for those employed and higher participation to the labour market (Bergman, Matsa and Weber, 2022[21]; Aaronson, Barnes and Edelberg, 2022[22]). In addition, tight labour markets increase opportunities for labour reallocation across firms with a potential beneficial effect for productivity.

Improving working conditions for the most disadvantage groups need not generate significant widespread inflationary pressures (especially in markets where monopsony power is significant – see Chapter 3). Duval et al. (2022[14]) argue that the overall impact on economy-wide wage pressure of rising tightness among low-pay industries in 2021 was limited due to the overall small share of such industries in total labour costs (in the United Kingdom and the United States). Inflationary pressures could arise from the combination of persistent labour shortages across sectors and the high or rising inflation driven by increases in energy and food prices. Faced with increasing wage demands, firms that have seen their profits increase over the pandemic due to an expected increase in demand might be able to accommodate them without significant price increases. However, firms whose profits have instead been eroded by the pandemic or by the increase in the cost of other inputs might not have much room for increasing wages without driving prices up.

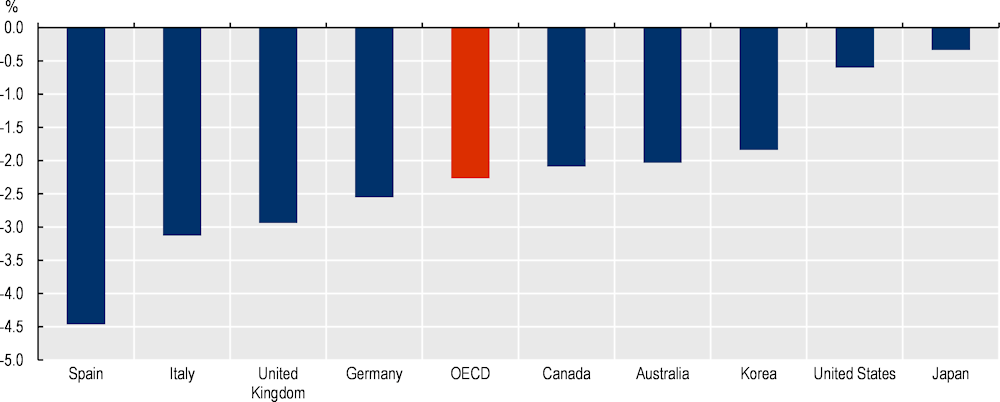

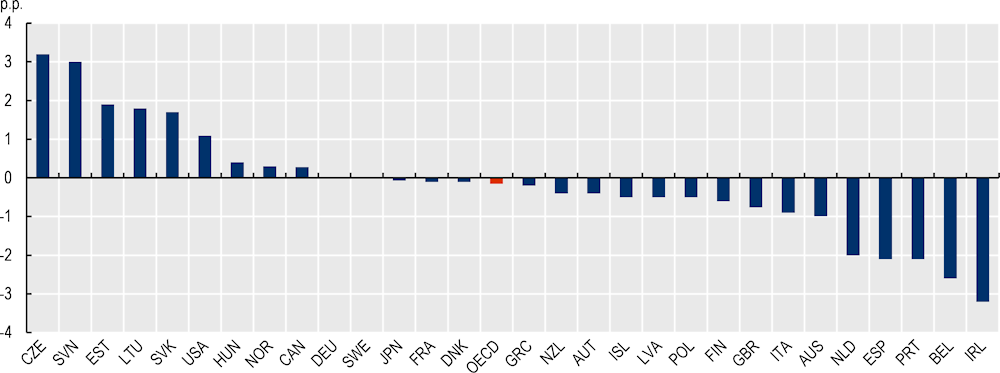

OECD (2022[4]) expects real wages to continue to decline over the course of 2022, as inflation is projected to remain elevated. Indeed, the war in Ukraine has already pushed inflation well above the level expected at the time of collective bargaining to set wage rates for 2022. In addition, nominal wage pressures are likely to ease as international migration picks ups and refugees are absorbed into the labour market of the host countries. For the OECD as a whole the pace of wage increases in nominal terms is projected to decline from around 4.25% in 2022 to 3.5% in 2023 (OECD, 2022[4]). In real terms, wage growth over 2022‑23 is projected to be negative in most countries (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.14. Real wages will decline in most OECD countries in 2022

Note: The figure shows projections for 2022 for real compensation per employee.

Source: OECD (2022), The Price of War: Presentation of the Economic Outlook 111, https://www.oecd.org/economic-outlook/.

The fall in real wages is hitting harder the low-pay groups who have already borne the brunt of the COVID‑19 crisis

The impact of rising inflation on real incomes is larger for lower-income households which have already borne the brunt of the COVID‑19 crisis. Indeed, the increase in expenditure resulting from recent food and energy price changes represents a larger proportion of total spending for lower-income households, and those households have limited scope to offset this by drawing on savings or reducing discretionary expenditures (OECD, 2022[4]). These households disproportionally include low-pay workers who were more likely to have their income reduced during the COVID‑19 crisis either through job loss or a reduction in hours worked (OECD, 2021[5]).

Beyond their role in facilitating collective bargaining, governments have a range of complementary policy tools available to cushion the impact of inflation on low-income households. Available evidence suggests that governments have acted swiftly through temporary energy bonuses and the tax and benefit system, although often with costly, untargeted interventions (see Chapter 2 for a discussion of recent interventions by OECD governments). Statutory minimum wages have also been adjusted in many countries, although they tend to continue to lag behind inflation (Box 1.2).

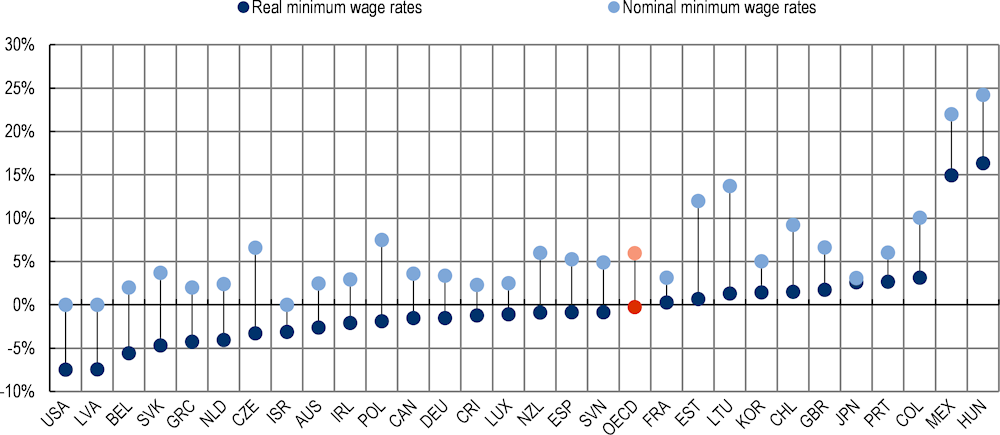

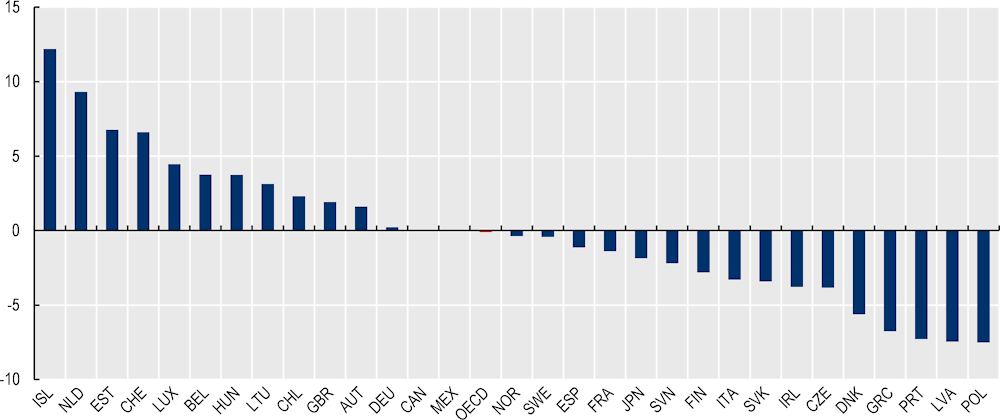

Box 1.2. High inflation is eroding the real value of statutory minimum wages

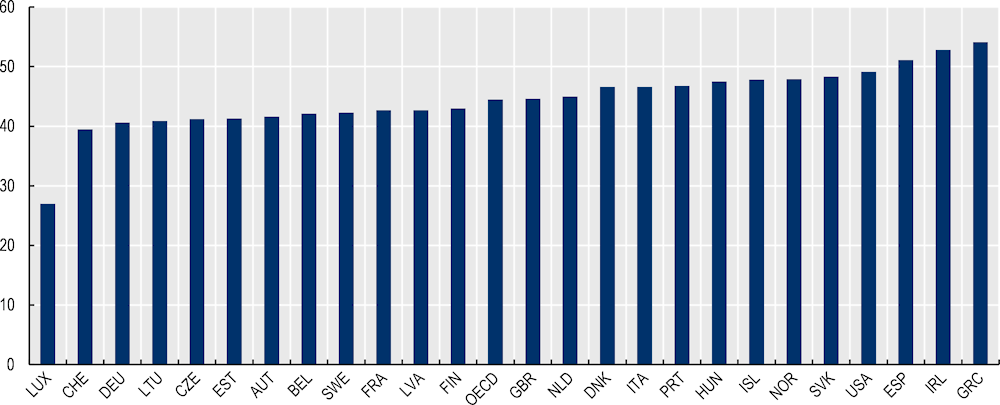

Across the OECD, the real value of statutory minimum wages declined in 2021. Indeed, the increases implemented in several countries have mostly been dwarfed by soaring inflation (Figure 1.15). As of 1 January 2022, on average across the 29 OECD countries where they exist and for which comparable data are available, statutory minimum wages were 6.0% higher than a year before in nominal terms, but 0.3% lower in real terms (Figure 1.15). This is a particular cause for concern given the disproportional impact of the recent rise in inflation on the lower-income households (OECD, 2022[4]).

The real value of the statutory minimum wage decreased in 18 of the 29 countries, with particularly large declines in the United States, Latvia – both countries where the nominal value of the minimum wage did not change between 2021 and 2022 – and Belgium – where instead an adjustment was triggered in September 2021 by the high level of inflation. Latvia was the only Eastern European country that left the minimum wage unchanged at the beginning of 2022, following a significant increase the year before and an increase in the non-taxable part of the wage (Eurofound, 2022[23]). In the United States, the federal minimum wage has not increased since 2009, but 21 states increased their minimum wage as of January 2022 – by an (unweighted) average of 7% (EPI, 2022[24]).

The decline of the real value of statutory minimum wages continued in most countries in the first half of 2022. Indeed, only very few countries have rules in place that trigger automatic adjustments in the minimum wage shortly after a sustained increase in inflation. In Belgium, high inflation triggered three minimum wage adjustments in September 2021, March 2022 and May 2022, in addition to an uprating that came into effect in April 2022 as a result of an earlier agreement. Similarly, France adjusted its minimum wage in response to high inflation in May 2022 and then again in August 2022. In Luxembourg, the automatic adjustment was last triggered in September 2021.

Among the countries where high inflation does not trigger immediate adjustments in the minimum wage, most adjust their rates in regular cycles that typically have an annual frequency. Several of these countries directly index minimum wages to some measure of inflation (including Slovenia, Costa Rica and Mexico) or anyway explicitly take inflation into account in the decision process. However, in an environment with prolonged and accelerating inflation, considerable delays in the adjustment of the minimum wage levels can have substantial detrimental effects on the living standards of the low-paid.

Figure 1.15. Nominal minimum wage increases are falling behind ongoing inflation

Notes: OECD is an unweighted average of the countries shown above. The nominal minimum wage rates effective as of 1 January 2022 are used. Year-on-year inflation rates at the end of January 2022 are used to yield the real minimum wage rates. For Spain, the figure reflects minimum wage rates set in February 2022, which came into effect retroactively from 1 January 2022. For Costa Rica, the unweighted average of four daily minimum wage rates differentiated by skill level is used. For Mexico, the unweighted average of minimum wage rates in the Zona Libre de la Frontera Norte and those in the rest of the country is used. For Australia and New Zealand, year-on-year inflation rates in the first quarter 2022 are used.

Source: Nominal minimum wage rates are referenced from OECD Tax-Benefit Database, Ministro del Trabajo (Colombia), Lista de salarios mínimos del sector privado (Ministerio de Trabajo y Seguridad Social, Costa Rica), Tabla de Salarios Mínimos Generales y Profesionales por Áreas Geográficas (Gobierno de México). Annual inflation rates are referenced from OECD Key Short-Term Economic Indicators: Consumer Prices, Consumer Price Index (Australian Bureau of Statistics), Consumer Price Index (Statistics Bureau of Japan), Consumer Price Index (Stats NZ).

Even within systems that only envisage regular uprating cycles, however, ad-hoc interventions in the face of exceptional circumstances remain a viable option to cushion the impact of inflation on the low-paid in a timelier manner. For example, Greece implemented an exceptional increase in its minimum wage by more than 7% in May 2022 due to inflation concerns (Vacas‑Soriano and Aumayr-Pintar, 2022[25]). In Spain, high inflation gave further impulse to the government’s plan to increase the minimum wage over time. In February 2022, the government decided a +5.2% increase that came into effect retroactively from the start of the year. In Germany, the minimum wage will increase in nominal terms by over 22% over the course of 2022. This is the result of an increase that came into effect in July following the regular uprating process and one that will come into effect in October as a result of a one‑off political decision, which, however, predates the recent inflation concerns.

Increases in the statutory minimum wages can help spread the cost of inflation more equitably between firms and workers, especially in markets where firms have monopsony power (see Chapter 3). The weight of the international evidence suggests that moderate minimum wage increases do not have a substantial negative impact on employment (Dube, 2019[26]; OECD, 2015[27]). Yet, the risk of a negative impact on employment might be higher when the cost of other production factors is increasing steeply, contributing to eroding any margins firms might have to absorb wage increases. In addition, while the minimum wages adjustments are generally effective in raising wages of individual workers at the bottom of the wage distribution, they are a relatively blunt tool for supporting low-income households, as many poor families have no one working and, at the same time, many minimum-wage workers live in households with above‑average incomes (OECD, 2015[27]). Governments can also mobilise other complementary policy tools to support low-income households, including the tax and benefit system and temporary bonuses to help them deal with the increase of energy prices – see Chapter 2 for a review of the range of interventions implemented across OECD countries.

1.3. Low-pay service industries lag behind in the recovery

The markedly asymmetric impact across sectors is a distinctive feature of this crisis that is well documented (OECD, 2021[1]). Industries where telework was not feasible – such as accommodation and food services, arts, and transportation and storage – saw large reduction in hours and employment losses across countries. By contrast, other service industries such as information and communication, as well as financial and insurance activities, saw an increase in activity already over the course of 2020. As the pandemic protracted into 2021, industries with limited teleworking possibilities continued to be affected disproportionally by more targeted restrictions and persistent changes in consumer’s habits even as the overall economic impact of each successive wave became smaller. In the vast majority of countries that made significant use of job retention schemes, the initial impact of the crisis was largely absorbed through reduction in hours, but, as the crisis lingered on, the burden of adjustment moved to the extensive margin, with many on short hours returning to work while jobs destroyed were not fully recovered (OECD, 2021[1]).

The deeply asymmetrical impact across industries and the substantive changes in consumption patterns and in the organisation of work that it prompted raise the concrete possibility that the crisis might lead to some structural and persistent changes in the distribution of employment across firms and sectors. The current phase of rapid developments in the labour markets documented in Section 1.1 makes it difficult to distinguish persistent structural changes from temporary distortions that might subside once the labour market returns to a more ordinary state. Nevertheless, monitoring trends in employment across industries is crucial to highlight possible forthcoming tensions between labour demand and supply. Importantly, the differential impact of the crisis and recovery on different industries remain a significant driver of the impact of the crisis across different groups of workers, as Section 1.4 documents.

To document how different industries and groups of workers have fared in the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis, this section and the next use data from Q1 2022, the most recent data point available for the largest number of OECD countries. Since seasonally adjusted data are not readily available for the outcomes of interest at a disaggregate level, these sections use unadjusted data and take Q1 2019 as the pre‑crisis reference point. Checks performed with data on overall employment indicate that results based on seasonally adjusted data for Q4 2019 vs Q1 2022 are consistent with those based on unadjusted data for Q1 2019 vs Q1 2022.

For the countries covered by Eurostat, all the employment series are affected by a statistical break in Q1 2021 (see Eurostat (2022[28])). Whenever available, break-adjusted series provided by Eurostat are used in the analysis. In the other cases, a correction described in Annex 1.B has been applied.

1.3.1. Employment still lags behind in low-pay services, but has grown in high-pay services

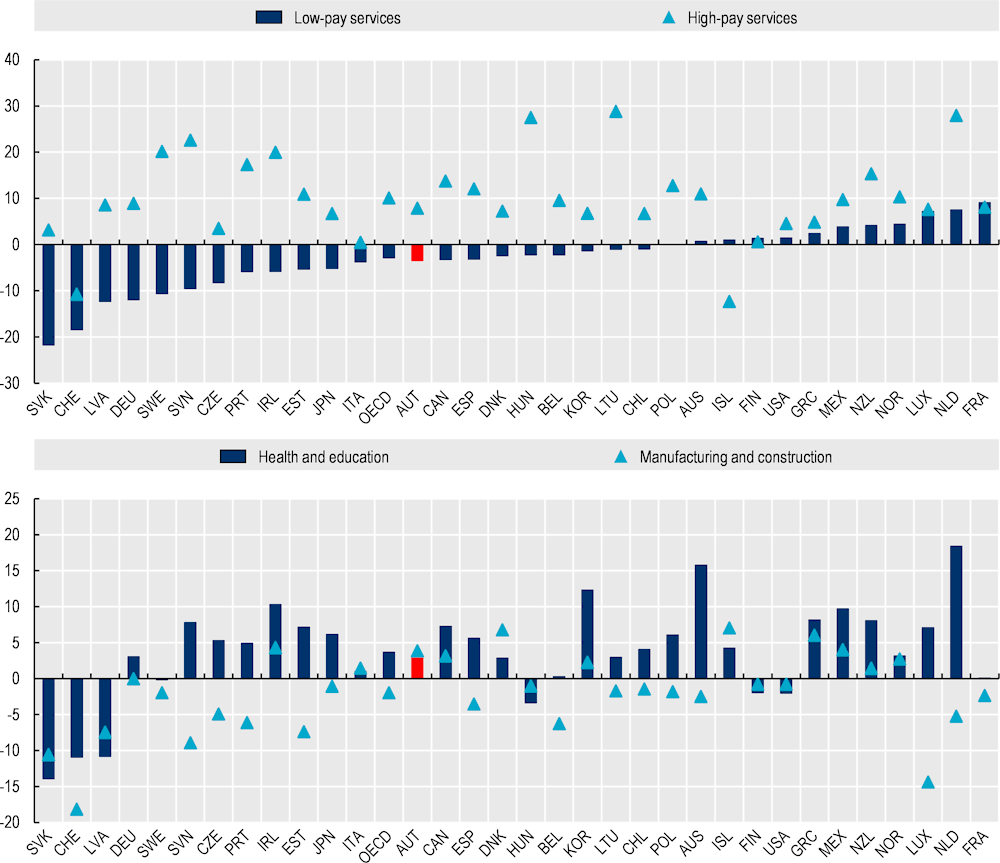

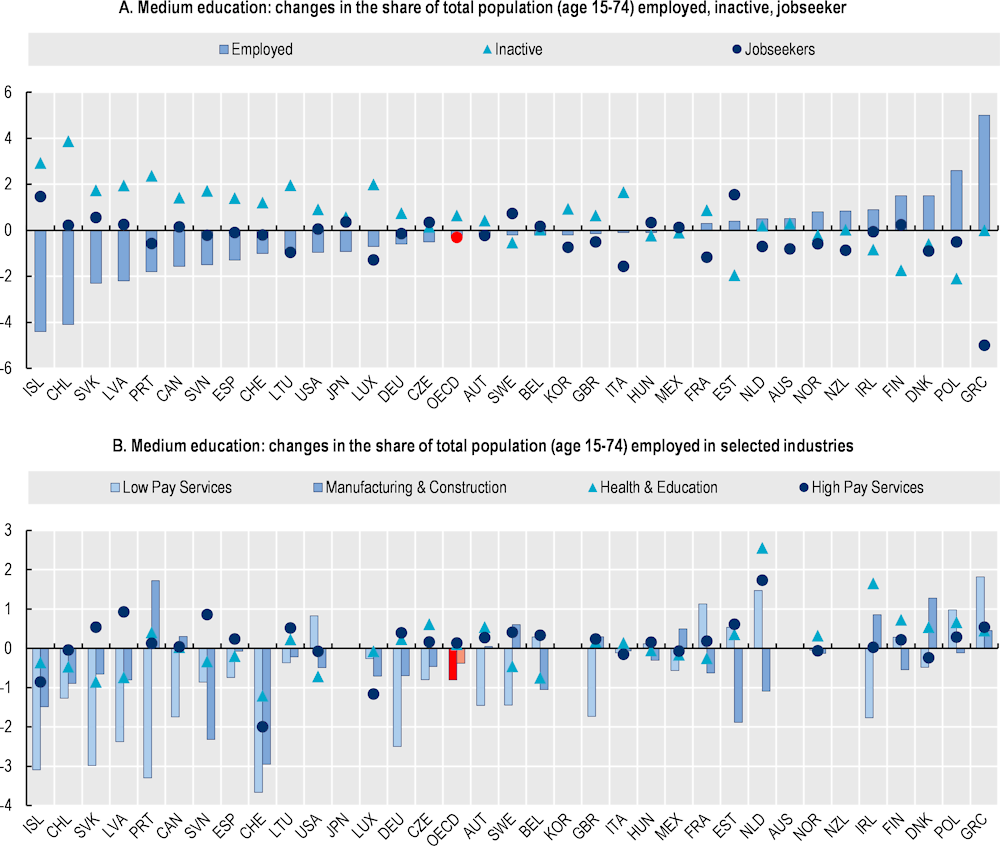

Two years since the onset of the crisis, employment changes by industry across OECD countries are still very clearly shaped by the pandemic (Figure 1.16). Relative to the same quarter of 2019, in Q1 2022, lower-pay industries exhibited employment losses or modest growth, while higher-pay service industries reported larger employment gains. Construction and Manufacturing – two sectors that employ many medium earners – also recorded employment losses. Employment also increased in Health and Education – two medium pay sectors that have been heavily affected by the pandemic.

In order to offer a manageable overview of employment changes by industry across countries given these aggregate results, Figure 1.17 presents results for selected industries aggregated in four broad groups: low-pay service industries (Accommodation and Food Service Activities, Administrative and Support Service Activities, Arts, Entertainment and Recreation, Wholesale and Retail Trade, and Transportation and Storage), Health and Education, Manufacturing and Construction, and high-pay service industries (Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities, Information and Communication, and Financial and Insurance Activities).

Figure 1.16. Low-pay industries are lagging behind in the recovery

Note: The figure reports the unweighted average of the percentage change in employment by industry relative to Q1 2019. Industries are ranked by the median wage in 2019 in the European Structure of Earnings Survey (SES). The ranking of industries is broadly consistent when 2019 data on median wages from the Current Population Survey of the United States are used. Average of Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the United States. Data for Slovenia are not included in the computation of the change in employment for Real Estate Activities due to data anomalies. The United Kingdom is not included due to anomalies in the data. See the main text for a discussion of the statistical break that occurred in the series provided by Eurostat in Q1 2021.

Source: EU-LFS for European countries, Canadian LFS, ENOE and ETOE for Mexico, ENE for Chile, Statistics Bureau of Japan (Labour Force Survey), Statistics Korea (Economically Active Population Survey), Australian Bureau of Statistics, Statistics New Zealand.

Employment gains in high-pay service industries and losses in low-pay services were widespread across countries (Figure 1.17). Indeed, high-pay service industries gained employment in 31 of the 33 countries for which data are available, with particularly large changes in the Netherlands, Hungary and Lithuania. Employment in low-pay service industries was below pre‑pandemic levels in 21 countries, with the largest falls seen in the Slovak Republic, Switzerland, and Latvia. The loss of employment in manufacturing and construction was also widespread (22 countries) and particularly large in Switzerland,28 Luxembourg, Slovenia, and the Slovak Republic.

Figure 1.17. Employment gains in high-pay services and losses in low-pay services are widespread across countries

Note: The figure reports percentage change in employment relative to relative to Q1 2019 for selected industries: Low-pay service industries (Accommodation and Food Service Activities, Administrative and Support Service Activities, Arts, Entertainment and Recreation, Wholesale and Retail Trade, and Transportation and Storage), Health and Education, Manufacturing and Construction, and high-pay service industries (Professional, Scientific and Technical Activities, Information and Communication, and Financial and Insurance Activities). OECD indicates the unweighted average of the countries shown. The United Kingdom is not included due to anomalies in the data.

See the main text for a discussion of the statistical break that occurred in the series provided by Eurostat in Q1 2021.

Source: EU-LFS for European countries, CPS, Canadian LFS, ENOE and ETOE for Mexico, ENE for Chile, Statistics Bureau of Japan (Labour Force Survey), Statistics Korea (Economically Active Population Survey), Australian Bureau of Statistics, Statistics New Zealand.

Given the lack of timely and internationally comparable data on workers’ transitions, there is no simple way to assess the extent to which these differences in employment performances across sectors are associated with significant reallocation of workers across industries (possibly through unemployment spells).29 The few studies that have looked into cross-industry transitions for specific countries report mixed results. Rottger and Weber (2021[12]) find an increase in transitions to other industries for workers who had lost employment in accommodation and food services in Germany towards the end of 2020, but not at the time of the first lockdown in the spring of the same year. In April 2021, Aaronson et al. (2021[29]) found no increase in the United States – a country that relied on temporary layoffs rather than job retention schemes – in the probability that unemployed workers move to new industries, nor an indication of an increase in direct flows from heavily impacted industries towards healthier ones. Similarly, in the United Kingdom – where a new job retention scheme was used massively to preserve jobs (OECD, 2021[1]) – Brewer et al. (2021[30]) found that even as job-to-job transitions reached a record high in Q3 2021, the fraction of such transitions occurring across industries was actually the lowest since the early 2000s. They also found no increase in the share of workers who had changed industry within a given year (including through intermediate unemployment spells) which had remained stable at around 5% since 2014. Basso et al. (2021[31]) use data from before the pandemic from Italy to highlight that, because of their skill profile, workers in the hardest-hit sectors have little reallocation potential if demand for in-person services remains depressed. In France, thanks to the massive use of the country’s job retention scheme, the number of workers leaving the accommodation and food services between the months of February 2020 and 2021 increased only marginally relative to the years before (DARES, 2021[32]).

The limited evidence of cross-sectoral transitions highlights the risk of growing mismatches in the labour market if the differential employment performance across industries persists. The growth in long-term unemployment might be a symptom of these developments (Section 1.2.1), but there are also indications of a particularly strong growth in labour demand in recent times in industries that have been lagging behind, at least in some countries (Section 1.2.2). While this strong growth might have been somewhat tamed by the Omicron wave affecting many OECD countries in late 2021 and early 2022, the broad trends suggest that these industries might recover some of the lost ground if the general epidemic and economic situation continues to progress towards increasing normalisation. Indeed, as discussed in Section 1.2.2, labour supply – rather than structural changes in labour demand – is likely to have slowed down the recovery of these industries in recent times. Aaronson et al. (2021[29]) observe that much of the disequilibrium in the United States labour market is driven by the severe impact of the crisis on accommodation and food services, expressing scepticism that the crisis might permanently set back a sector that has steadily grown over the past 70 years.

In addition to the possible reallocation of employment across industries, the pandemic might also have seen reallocation of employment within industries towards firms better equipped to withstand the pandemic shock. Indeed, there is some evidence of employment reallocation among small businesses towards high-productivity and tech-savvy firms despite the deployment of new job retention schemes in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom (Andrews, Charlton and Moore, 2021[33]). This type of reallocation – especially when occurring on a large scale over a short period of time – can also present challenges for workers if the type of labour demanded by expanding firms is different from that normally employed in the same industry. In this context, a concern is that labour demand might have shifted towards more highly skilled workers who might be better equipped to deal with the new changes in the workplaces. Again, timely and internationally comparable evidence on this is hard to come by. A first tentative exploration of the data available on the education level of new hires across countries reveal no clear increase in the share of workers with higher education hired in different industries compared to the years immediately before the COVID‑19 pandemic. Nevertheless, changes might take more time to appear clearly in aggregate data, or they might affect workers with different skills within the same educational groups. Monitoring the evolution of the demand for different types of skills is an important task for future research that can help inform policies aimed at supporting workers that stand to lose from these potential transformations.

1.4. Much of the initial very unequal impact of the crisis has been re‑absorbed, but some vulnerable groups lags behind in the recovery in many countries

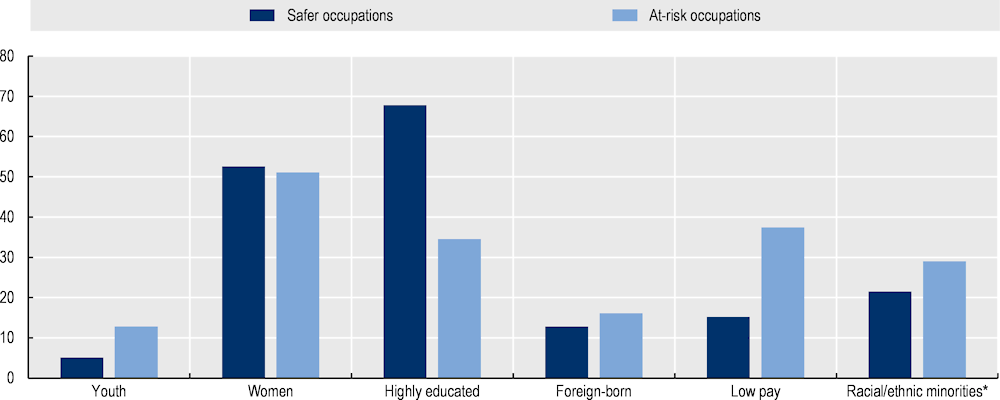

The highly sectoral nature of the crisis has meant that some groups of workers shouldered the bulk of the burden when the crisis broke out. OECD (2021[1]) documented how low-paid workers, those with lower education and young people paid a high and more persistent price during the crisis over the course of 2020. As the pandemic continued to shape employment dynamics across industries in 2021, different groups of workers have benefitted to different extents from the unexpectedly robust recovery described in Section 1.2.30

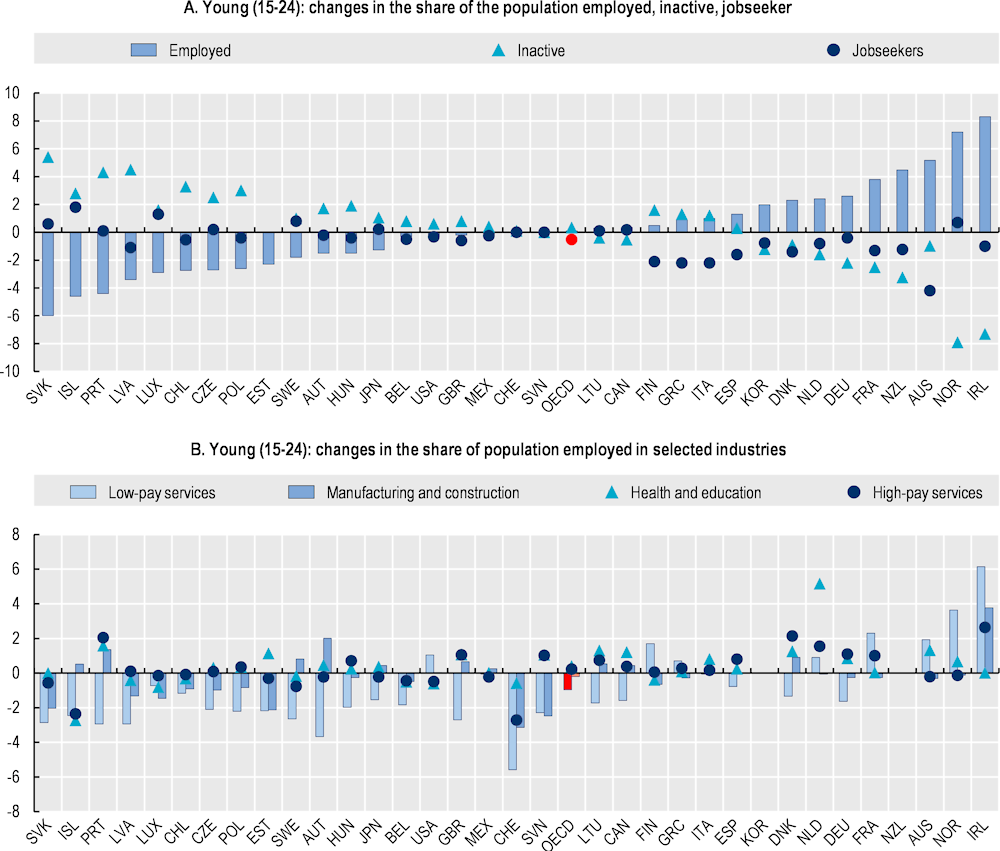

1.4.1. Young people have recovered some of the lost ground but are still lagging behind, especially in some countries

Young people were particularly affected by the initial ravages of the crisis (OECD, 2021[1]). Youth unemployment in the OECD surged at the onset of the pandemic, and hours worked by young people fell by more than 26% – close to double the fall seen among prime‑aged and older workers (15%).

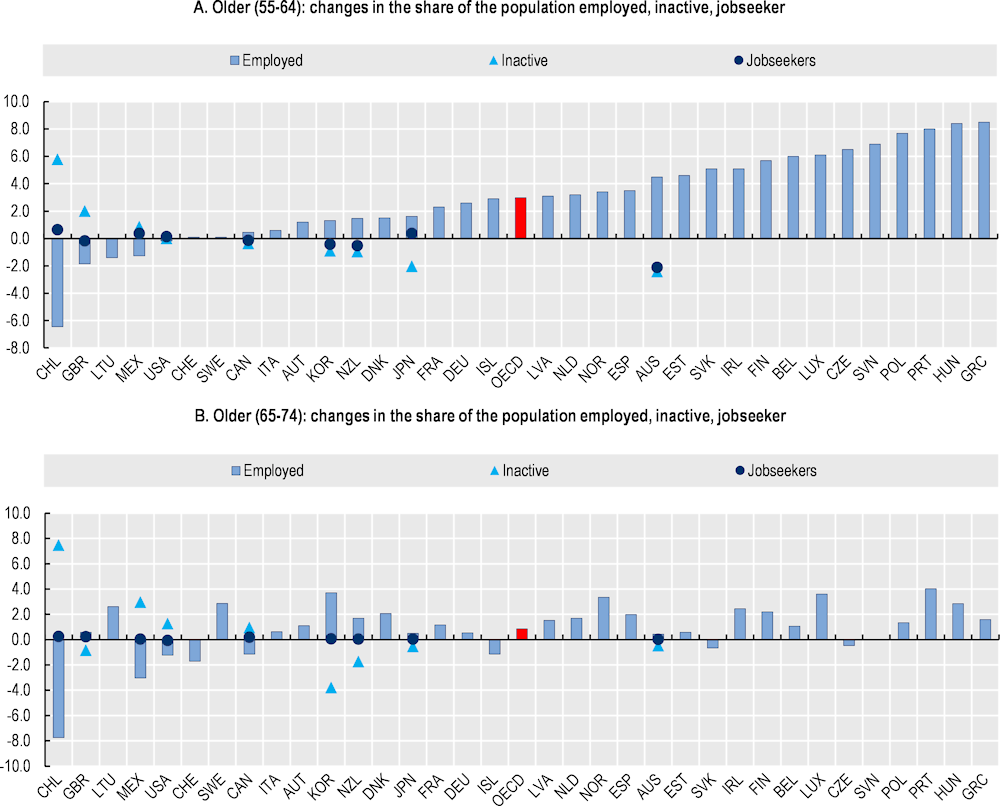

At the start of 2022, on average across the OECD, young people had recovered much of the lost ground, but were still lagging behind older adults. Indeed, on average across the OECD the youth employment rate was 0.1 percentage points above its pre‑crisis levels (as measured by employment rates in Q1 2019), but remained below that level in over half the countries by an average of 2.2 percentage points (Panel A of Figure 1.18). By contrast, the employment rate for workers aged 25 to 54 years was on average 1 percentage points higher than before the crisis and still recovering only in eight countries. Among those aged 55 to 64, the employment rate was 3 percentage points higher than before the crisis and lagging behind only in five countries.

In the countries where the employment rate of young people was still below pre‑crisis levels, this was mostly associated with an increase in inactivity rather than unemployment. Declines in the employment rate of young people exceeded 2 percentage points in nine countries, and exceeded 4 percentage points in Portugal, Iceland, and the Slovak Republic. In the 15 countries where youth employment grew above pre‑crisis levels, this mostly resulted in a decline in inactivity. Employment rates were above pre‑crisis levels by 3.5 percentage points or more in France, New Zealand, Australia, Norway, and Ireland.

The large declines in youth employment are mostly accounted for by losses of employment in low-pay service sectors and to a lesser extent in manufacturing and construction (Panel B of Figure 1.18). While results vary across the 15 countries where the employment of young people increased, on average the broad industry groups that contributed the most to these gains were health and education, low-pay services and high-pay services.

Figure 1.18. Youth employment recovered much of the ground lost at the start of the crisis, but is still lagging behind that of older adults