Chiara Criscuolo

Antton Haramboure

Alexander Hijzen

Michael Koelle

Cyrille Schwellnus

Chiara Criscuolo

Antton Haramboure

Alexander Hijzen

Michael Koelle

Cyrille Schwellnus

Around one‑third of overall wage inequality can be explained by differences in wage‑setting practices between firms rather than differences in the level and returns to workers’ qualifications. Gaps in firm pay, in turn, reflect differences in productivity, but also disparities in wage‑setting power. To tackle rising income inequality, worker-centred policies (e.g. education, adult learning) need to be complemented with firm-oriented policies. This involves, notably: (1) policies that promote the productivity catch-up of lagging firms, which would not only raise aggregate productivity and wages but also reduce wage inequality; (2) policies that promote job mobility, which would reduce wage inequality at a given level of productivity dispersion while enhancing the allocation of jobs across firms; and (3) policies that curtail the wage‑setting power of firms with dominant positions in local labour markets, which would raise wages and reduce wage inequality without adverse effects on employment and output.

This chapter examines the role of firm performance and wage‑setting practices in wage inequality, including the gender wage gap, and discusses the policy implications. The evidence is based on a new set of harmonised linked employer-employee data covering 20 OECD countries and, as such, represents the most ambitious effort to date to make use of administrative data in a cross-country context in this area. The chapter provides comprehensive evidence that firms tend to have considerable power to set different wages for similarly qualified workers, with important implications for policies aiming to promote broadly shared economic growth. The main message is that complementing worker-centred skills policies with policies centred on firms’ wage‑setting practices would go a long way towards addressing wage inequality while promoting economic growth.

The main findings of the chapter can be summarised as follows:

On average across the 20 countries covered in this chapter, differences in wage‑setting practices between firms, as reflected by firm wage premia (differences in pay between firms unrelated to workforce composition), account for around one‑third of overall wage inequality (the variance of wages across all workers). Moreover, differences in wage-setting practices account for one‑quarter of the gender wage gap (the difference in average wages between similarly qualified men and women). These findings suggest that firms have considerable leeway to set wages independently from their competitors and that wages are not exclusively determined by skills. The firm where someone works matters for their wages.

When firms have wage‑setting power, those with low productivity can compete on the basis of low wages without the risk of losing all their workers, while those with high productivity offer higher wages than low productivity ones to attract workers and grow larger. On average across the countries covered by the analysis, around one‑sixth of productivity gaps between firms translate into gaps in firm wage premia. High-skilled workers and men benefit more from good firm performance in terms of higher wages than low-skilled workers and women overall.

The transmission of productivity gaps to firm pay gaps is particularly pronounced when there is a low rate of job mobility (workers moving jobs voluntarily). In such a situation, low-pay firms face a more limited risk of seeing their workers move to high-pay ones. An increase in the rate of job mobility from that of a low-mobility country such as Italy to that of a high-mobility country like Sweden is estimated to lead to a 15% drop in overall wage inequality. Limited job mobility for women, moreover, contributes to the gender wage gap by limiting access to jobs in high-wage firms and weakening their bargaining power.

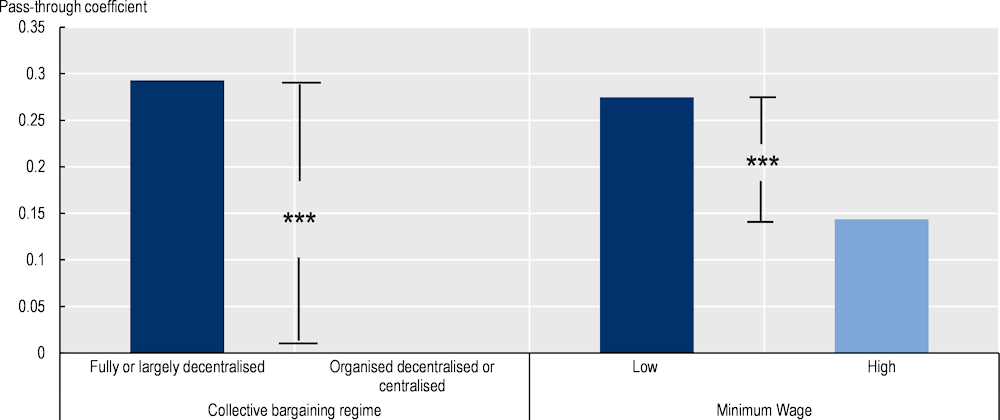

More centralised collective bargaining and higher minimum wages weaken the pass-through of productivity to wage premia by limiting the scope of low-performing firms to compete on the basis of low wages, and hence reduce wage dispersion between firms.

Tackling high wage inequality requires complementing worker-centred skills policies with policies centred on firms’ wage‑setting practices. This involves:

Policies that narrow productivity gaps between firms could significantly reduce overall wage inequality. This could be achieved by helping low-performing firms to adopt new technologies, digital business models and high-performance management practices.

Reducing barriers to job mobility would narrow wage gaps between firms by reducing the capacity of low-performing firms to compete on the basis of low wages. Job mobility could be enhanced by strengthening adult learning and activation policies, reforming labour market regulation, and supporting geographical mobility (e.g. via transport and housing policies) and telework.

Collectively agreed or statutory wage floors represent a complementary policy response – provided that wage floors are not set too high – because they reduce the ability of firms to exploit the consequences of limited job mobility by competing on the basis of low wages.

Many OECD countries have been grappling with low productivity growth and rising income inequality over the past few decades.1 Meanwhile, gaps in business performance have widened, with a small number of high-performing businesses continuing to achieve high productivity growth while others have been increasingly falling behind (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[1]; Berlingieri, Blanchenay and Criscuolo, 2017[2]). Moreover, high-performing firms are also pulling away in terms of sales and profitability, and industry concentration is growing in many countries (Bajgar et al., 2019[3]). The COVID‑19 crisis risks reinforcing these trends, as some unprofitable businesses have been kept afloat and the digitalisation of business models has accelerated. An emerging body of evidence suggests that growing productivity gaps between businesses can at least partly account for low aggregate productivity growth (Berlingieri, Blanchenay and Criscuolo, 2017[2]), but evidence about their implications for wage inequality is still limited. While some degree of wage inequality may simply be the by-product of differences in incentives to work, skill acquisition and job mobility, excessively high levels can become an obstacle to social cohesion by raising overall income inequality and undermining equality of opportunities.2

Until recently, a large part of research into the causes of wage inequality focused on differences in skills between workers in an analytical framework that disregarded differences between firms. In the standard skill demand and supply framework, increases in wage inequality can, to a large extent, be explained by increases in the demand for skills, which are in turn driven by technological progress, including automation and digitalisation, and globalisation. Labour markets are assumed to be perfectly competitive and wages of high-skilled workers are bid up irrespective of the firm in which they work. Consistent with this framework, policy has mainly focused on ensuring that workers have the skills that are demanded by employers through investments in education and adult learning. While this standard framework remains very useful, it cannot account for a number of empirical facts. First, there is large wage inequality even within narrowly defined skill categories, including between similarly qualified men and women (Autor, Katz and Kearney, 2008[4]; Goldin, 2014[5]; Lemieux, 2006[6]). Second, there are large cross-firm differences in average pay for workers with similar qualifications (Card, Heining and Kline, 2013[7]; Song et al., 2018[8]). Third, workers’ mobility decisions are fairly unresponsive to wages, allowing employers to bid them down (Sokolova and Sorensen, 2020[9]), especially in labour markets with a high degree of employer concentration (see Chapter 3) or for specific groups of workers, including women, with fewer job options to balance work and family responsibilities.

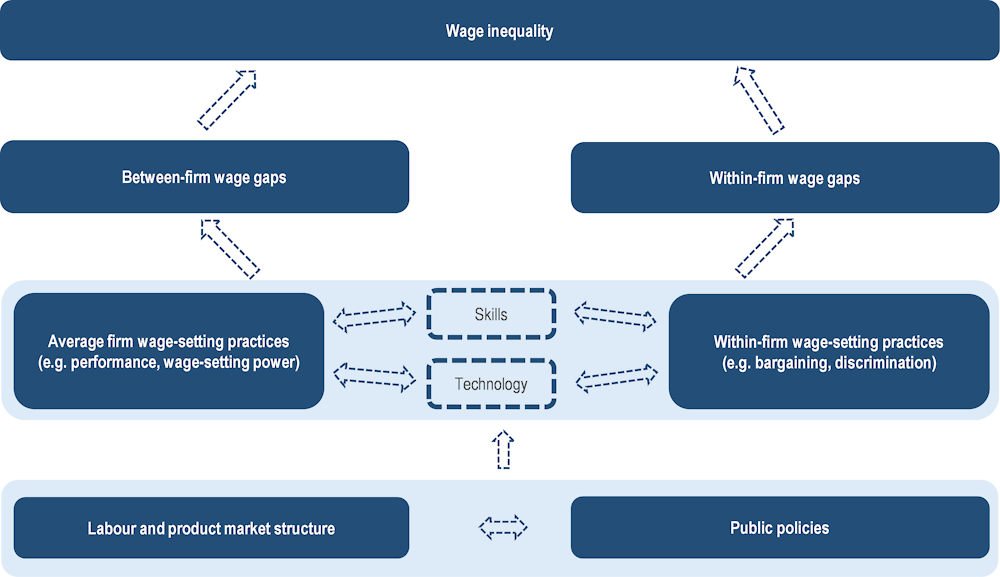

This chapter places the firm at the centre of the analysis into the causes of wage inequality by explicitly taking account of differences in firms’ wage‑setting practices. Wage‑setting practices in this chapter refer to the ability and incentives of firms to set wages differently from those of their competitors for similarly qualified workers, for example depending on their performance, their wage‑setting power and the nature of wage‑setting institutions. The analytical framework explicitly takes labour market frictions and firm heterogeneity into account. In this framework, firms benefit from some degree of wage‑setting power in the sense that wage differences between them are not immediately neutralised by competition between firms hiring perfectly mobile workers. The implication is that between-firm differences in product market performance and specific features of the labour market, such as employer concentration and differences in mobility between specific groups, notably men and women, can lead to wage differences between workers with similar skills. From a policy perspective, placing firms at the centre of the analysis broadens the scope of policies to address wage inequality, coupling worker-centred policies, such as education and adult learning policies, with firm-based policies, including policies to narrow productivity gaps, promote job mobility and limit firms’ wage‑setting power.

The chapter makes three key contributions. First, it quantifies the contribution of differences in firm wage‑setting practices to wage inequality in a cross-country context using a novel set of harmonised linked employer-employee data that contain information on the characteristics of workers and the firms for which they work. Firm wage‑setting practices are captured empirically by firm wage premia, i.e. the part of average firm wages that is not due to the composition of the workforce. Previous research using linked employer-employee data has typically focused on individual countries. A comparison of results based on single‑country studies is unreliable as cross-country differences might reflect variation in data treatment (e.g. data sampling procedures and variable definitions) and empirical methodologies rather than genuine variation in institutional settings and structural conditions across countries. This chapter harmonises the data treatment as far as possible and uses a unified empirical methodology in order to allow direct comparability of results across countries. Second, the chapter analyses the firm, market and policy determinants of firm wage-setting practices in terms of firm performance, the degree of job mobility and the nature of wage-setting institutions by taking advantage of the cross-country dimension of the data. Third, the chapter draws policy conclusions from the empirical evidence, highlighting the need to complement worker-centred policies with firm-centred measures to boost productivity and for a broad sharing of these productivity gains with all workers through higher wages.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. Section 4.1 presents the conceptual framework, the empirical methodology and the harmonised linked employer-employee data used to analyse the role of firms in wage inequality. Section 4.2 presents the results of the analysis. Section 4.3 draws out the policy implications. Section 4.4 concludes.

Aggregate wage inequality arises from wage gaps between firms and wage gaps within them (Figure 4.1). To some extent, wage gaps between firms can be explained by differences in the skill composition of the workforce. For instance, firms employing above‑average shares of high-qualified workers generally pay higher wages than the average firm. But wage gaps between firms are also the result of differences in average wage‑setting practices between them. These may result from differences in performance between firms, differences in wages set unilaterally by employers (as in monopsony or wage‑posting models) or differences in their bargaining position (as in wage‑bargaining and rent-sharing models). For instance, low-wage firms could compete on the basis of low wages without the risk of losing all their workers, while high-productivity firms could offer higher wages to attract workers and grow their business. Wage gaps within firms largely reflect differences in worker skills, such as education and experience. However, even within firms, wage gaps may to some extent be explained by firm wage‑setting practices unrelated to workers’ qualifications. For instance, firms may pay men and women differently despite having similar qualifications. This could be due to differences in women’s bargaining position relative to men, but also to employers’ perceptions of differences in productivity, or employers’ conscious and unconscious biases, leading to discriminatory behaviours.

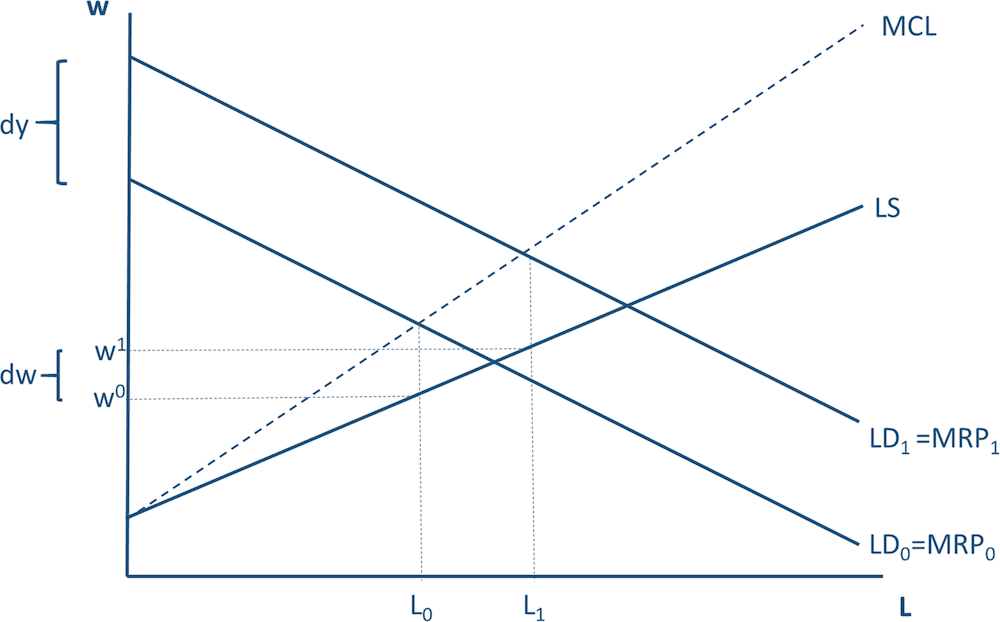

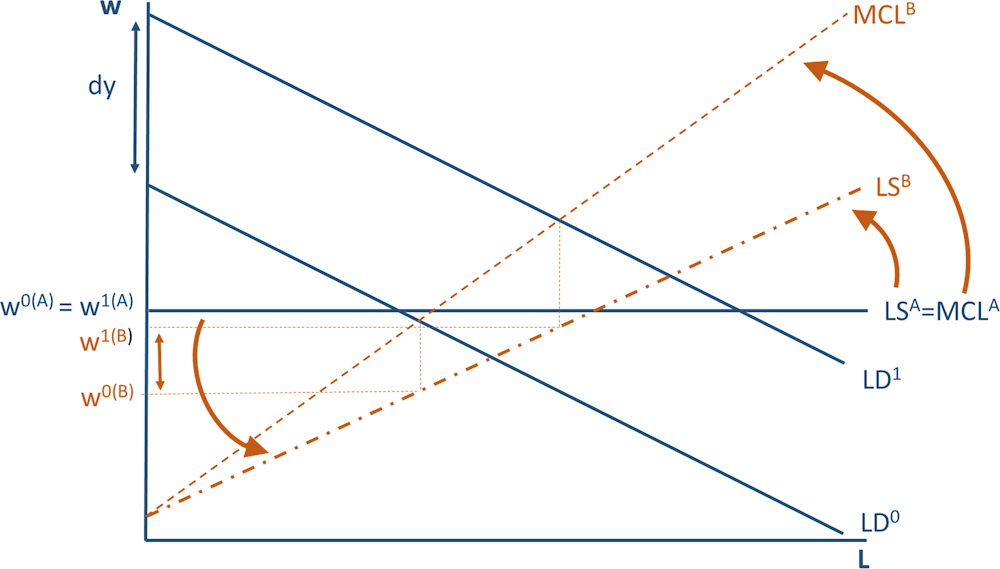

Given skills and non-wage working conditions, differences in wages across firms can only arise in labour markets with frictions. In a labour market without frictions – where job search, job mobility and hiring are costless – a worker with a given set of characteristics (e.g. formal qualifications, experience, motivation, etc.) would immediately move if they were offered a higher wage by a competing firm with similar non-wage working conditions. In this case, workers’ wages are wholly determined by their specific skill set, with firms bidding up wages until they equal workers’ marginal productivity. Firms with high average productivity employ more workers than their lower-productivity competitors but, since marginal productivity tends to decline with employment and equalise across firms, they do not pay higher wages given the skills of workers and non-wage working conditions. Hence, pay differences in the case of a frictionless labour market entirely reflect differences in skill composition or compensating differentials related to differences in non-wage working conditions. For instance, one firm may mainly employ high-skilled workers at high wage rates, whereas another one may mainly employ low-skilled workers at low wage rates, because they perform different economic activities or use technologies with different skill requirements.

In a labour market where job search, job mobility and hiring are costly (or workers differ in their preferences regarding the non-wage aspects of jobs), marginal productivity differences persist across firms and similar workers may be paid differently in different firms. This can be the case when wages equal marginal productivity but marginal productivity is not equalised across firms (competitive wage‑setting), when wages are set unilaterally by employers as a markdown from marginal productivity (monopsonic wage‑setting) or when workers and firms bargain over the rents associated with the job match (wage bargaining or rent-sharing). Low productivity firms will tend to be too large from an efficiency point of view in the sense that even by paying a low wage they do not lose all their workers. Conversely, high productivity firms will tend to be too small since they need to offer higher wages to attract sufficient workers for achieving their optimal size. Consequently, limited job mobility is likely to increase wage differences between firms, thus contributing to higher wage inequality, while weakening the efficiency of job reallocation across firms.3 Moreover, in a labour market with frictions, it becomes possible for firms to set differentiated wages for similarly qualified groups of workers within the firm, if workers’ job search and mobility costs differ and hence their bargaining position, as may be the case, for instance, for similarly skilled men and women.

Differences in firm wage‑setting practices have an immediate impact on overall wage inequality whereas differences in skill composition between firms have no direct impact on overall wage inequality. For instance, at a given composition of skills, it is irrelevant for overall wage inequality whether high-skilled workers cluster in the same firms (which would lead to high between-firm wage inequality and low within-firm wage inequality) or whether they are evenly distributed across firms (which would lead to low between-firm wage inequality and high within-firm inequality). By contrast, differences in firm wage‑setting practices directly raise overall wage inequality even between workers with similar levels of skills. Differences in wage‑setting practices may also lead to differences in skill composition having an indirect impact on overall wage inequality if high-wage workers sort into firms setting high wages. This is more likely to be the case when high-productivity firms use technologies that rely heavily on specific skills.

The analysis focuses on the relevance of firm performance and firm wage‑setting practices in wage inequality (including the gender wage gap) by looking at some of their main determinants – namely firms’ productivity, the degree of job mobility and the nature of wage‑setting institutions. The determinants of returns to skills, skill composition and between-firm productivity gaps are outside the scope of this chapter and have been analysed extensively in previous work (Box 4.1).

While this chapter focuses on the link between public policies and firm wage-setting practices, a large body of work analyses the effect of public policies on returns to skills, skill composition and productivity gaps between firms.

Returns to skills. At a given skill composition of the workforce, within-firm wage inequality reflects the dispersion of returns to skills. For instance, within-firm wage inequality tends to increase when the wage premium associated with a tertiary education degree increases. A large body of work has analysed the structural and policy determinants of returns to skills in the framework of a race between education and technology (Katz and Murphy, 1992[10]; Autor, Goldin and Katz, 2020[11]). The main role of public policies in this framework is to support the supply of skills to meet the increasing demand resulting from technological change. Indeed, the evidence suggests that a more abundant supply of skills relative to demand reduces the skills premium and therefore wage inequality (OECD, 2015[12]). However, the supply and demand framework appears to be less relevant at the extremes of the wage distribution. At the bottom of the wage distribution policies and institutions may be more important than market forces in setting the wages of low-skilled workers, while at the very top superstar effects may be particularly important (Autor, Goldin and Katz, 2020[11]).

Skill composition. An emerging body of evidence analyses the effect of public policies on firms’ skill composition. One strand of work has focused on the increased sorting of workers into firms with similar co-workers which may be linked to domestic outsourcing, including to independent contractors of on-line platforms (Goldschmidt and Schmieder, 2015[13]; OECD, 2021[14]; Weil, 2014[15]), Firms increasingly resort to specialised firms for the provision of low-skilled labour services, such as cleaning, security and restauration. Such worker-to-worker sorting does not have a direct effect on wage inequality, as increased between-firm wage inequality is offset by reduced within-firm wage inequality. But it may weaken lower-qualified workers’ bargaining position and upward mobility, and hence increase the persistence of inequality over the life course. Policies to strengthen collective bargaining and training in firms providing outsourced services could reduce the adverse effects of worker-to-worker sorting. Another strand of work has focused on complementarities between workers’ skills and technologies, which may lead to the sorting of the highest-skilled workers into the highest-paying firms (Card, Heining and Kline, 2013[7]). Such worker-to-firm sorting may be efficiency enhancing but directly raises wage inequality.

Productivity gaps. Between-firm productivity gaps have tended to widen in several OECD countries (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[1]; OECD, 2015[16]), which has contributed to widening firm-wage gaps (Berlingieri, Blanchenay and Criscuolo, 2017[2]) and rising wage inequality. Public policies can directly influence the extent of between-firm productivity gaps and the extent of pay gaps at a given level of productivity gaps.

The role of firms in wage inequality – measured using the variance of logarithmic wages – is analysed in three steps. In a first step, the contribution of firms in overall wage inequality is measured by focusing on the role of firm wage premia, i.e. the part of wages that is determined by the characteristics of firms rather than those of their workers. In a second step, the role of firm performance is analysed by focusing on the link between labour productivity and wage premia at the firm level. In a third step, the role of structural and policy factors in the link between firm performance and wage premia is analysed. See Box 4.2 for the technical details.

To measure the component of wage inequality that is due to firms, the analysis focuses on firm wage premia i.e. the part of average firm wages that is unrelated to the characteristics of the firm’s workforce. Firm wage premia are captured by the estimated firm-fixed effects in an otherwise standard traditional human-capital wage equation with controls for gender, age and education/occupation.4 Overall wage inequality is then decomposed into three components: (i) the contribution of differences in firms’ wage‑setting practices as measured by the dispersion in firm wage premia; (ii) the contribution of worker sorting as measured by the dispersion of average firm wages that can be attributed to differences in workforce composition, including workers’ skills; (iii) the contribution of within-firm inequality as measured by the average dispersion of wages within firms, which captures returns to skills and possibly also within-firm differences in wage-setting practices between similarly qualified workers within firms (e.g. between men and women).

The link between productivity and wages at the firm level (productivity pass-through) is analysed empirically by directly relating firm wage premia to firm labour productivity.5 This approach is used to document differences in pass-through between countries as well as differences between different groups of workers such as low-skilled and high-skilled workers or men and women. A drawback of this approach is that it is only feasible for the subset of countries covered in this chapter where information on firm productivity is available in the worker-level data, making it difficult to systematically relate the degree of pass-through to industry and country characteristics. The firm-level approach is therefore complemented with an industry-level approach that relates between-firm dispersion in wage premia within industries to between-firm dispersion in labour productivity, using external data sources on productivity dispersion from the OECD MultiProd database (Berlingieri et al., 2017[17]). Given the significant variation across countries, industries and over time, the industry-level approach is employed for analysing the structural and institutional determinants of firm-level productivity-wage pass-through.

The analysis of the structural and policy determinants of firm-level wage pass-through concentrates on the role of: i) job mobility, which captures the responsiveness of voluntary worker mobility to firm wages and hence provides a measure of the wage‑setting power of firms; and ii) that of wage‑setting institutions, in the form of statutory minimum wages and collective bargaining systems, which tend to constrain the extent to which productivity differences between firms translate into wage differences between firms. Job mobility is proxied by the share of annual job-to-job transitions in total employment using external data by country and industry from the European Labour Force Survey constructed by Causa et al. (2021[18]). The advantage of focusing on direct job-to-job transitions instead of all worker transitions is that such transitions are most likely to be voluntary, while transitions to non-employment, which are more likely to be involuntary, are excluded.6 The role of collective bargaining is analysed by focusing on the level of decentralisation in collective bargaining systems by distinguishing between fully or largely decentralised systems based on firm-level bargaining and organised decentralised or more centralised systems with a stronger emphasis on sector or national level bargaining (OECD, 2019[19]).7 The level of the statutory minimum wage is expressed as a ratio of the median wage of full-time workers.

Wage inequality is measured as the total variance of logarithmic wages,1 which can be decomposed into the variance of average wages between firms and the variance of individual wages within firms:

where V denotes the variance, the logarithmic wage of worker i in firm j and the average logarithmic wage in firm j.

To disentangle the role of wage premia and workforce composition in between-firm wage dispersion, firm wage premia are estimated using a traditional human-capital earnings equation augmented with firm fixed effects (Barth et al., 2016[20]):

where denotes the logarithmic wage of worker i in firm j; denotes a vector of observable worker characteristics; denotes the estimated return to these characteristics; denotes firm fixed effects; and denotes the error term. The observable worker characteristics considered in the empirical model generally include education and/or occupation, age, gender, indicators for part-time work and interaction terms between these variables. This equation is estimated separately for each country and year. The estimated firm fixed effects provide a measure of firm wage premia.

Based on Equation 4.2, denoting estimated coefficients and variables with superscript ^ and defining (workers’ predicted wages based on observable earnings characteristics) the total variance of can be written as follows:

where is the variance of predicted wages based on observable earnings characteristics; is the variance of firm-specific wage premia; is the covariance of predicted wages with firm-specific wage premia and is the variance of residual wages.

As proposed by Barth et al. (2016[20]), defining and , where is the average of all individual workers’ in the firm, the total variance of can be re‑written as:

where is a measure of similarity between the workers’ predicted wages based on observable earnings characteristics and the estimated firm fixed effects (a measure of worker-to-firm sorting) and is a measure of similarity between the workers’ predicted wages and the average predicted wage in their firm (a measure of worker-to-worker sorting).

The between-firm variance can thus be decomposed into contributions of wage premia (variance of firm-specific wage premia ) and workforce composition (worker-to-worker sorting and worker-to-firm sorting ). The within-firm variance can be decomposed into contributions from the returns to observed and unobserved earnings characteristics minus that from worker-to-worker sorting .

As a robustness check, Annex 4.C reports results of the decomposition based on a version of Equation 4.2 that includes in addition worker fixed effects, following Abowd et al. (1999[21]). This ensures that firm wage premia do not capture unobserved differences in worker composition across firms related to time‑invariant characteristics such as talent or ability.

When information on productivity is available, productivity-wage pass-through at the firm-level can be estimated using the following firm-level equation:

where denotes the estimated firm wage premium in firm j, and year t; logarithmic labour productivity; the estimated pass-through parameter; and industry and year fixed effects; and the error term. Labour productivity is either measured as value added per worker or, if information on value added is not available, as sales per worker. This equation is estimated using employment weights for each country and group of workers within these countries (by skill and gender).2 A significant relationship between wage premia and productivity at the firm-level suggests that wage premia do not merely reflect compensating differentials but also capture the role of labour market frictions.

When there is no information on productivity in the linked employer-employee data but there is external data on productivity dispersion by industry and year, one could alternatively estimate firm-level productivity-wage pass through using industry-level data pooled across countries. More specifically, assuming non-zero productivity-wage pass-through, taking the variance of Equation 4.5 and pooling across countries provides yields:

where denotes the employment-weighted variance of wage premia across firms; the squared pass-through elasticity; , and denote country, industry and time fixed effects; and the error term.

To identify factors associated with productivity wage pass-through, the coefficient on productivity dispersion is allowed to vary according to structural and institutional characteristics:

where the parameter captures the association between wage premia dispersion and the structural and institutional characteristics , while the parameter on the interaction term between the structural and institutional characteristics and the variance of firm productivity captures the association with the squared pass-through elasticity. The structural and institutional characteristics are measured using dummy variables to limit the role of outliers.3

1. The variance as a measure of inequality has a number of properties that are useful in the present context, including that it is additively decomposable, scale independent and more comprehensive than alternative measures of inequality, such as the 90th/10th percentile ratio.

2. This specification effectively uses variation in wage premia and labour productivity within firms over time as well as between firms at any given point in time (and in a given industry) to estimate pass-through. The advantage of using cross-sectional variation on top of the within-firm variation is that the estimated pass-through captures the long-term link between wage premia and productivity rather than the short-term response of wage premia to productivity shocks. Since labour productivity is an equilibrium outcome, there is a potential endogeneity issue, which should be borne in mind when interpreting the results.

3. More specifically, if the underlying variable is continuous, it is set to one when its value exceeds the sample median and zero otherwise. Results using continuous variables yield very similar results (OECD, 2021[22]).

Empirically distinguishing the effects of firm performance and firm wage‑setting practices from that of skill composition requires the use of linked employer-employee data. The linked employer-employee data used in this chapter are drawn from administrative records designed for tax or social security purposes or, in a few cases, mandatory employer surveys. As a result, these data are very comprehensive, often covering the universe of workers and firms in a country, and of high quality, given the financial implications of reporting errors for tax and social security systems.

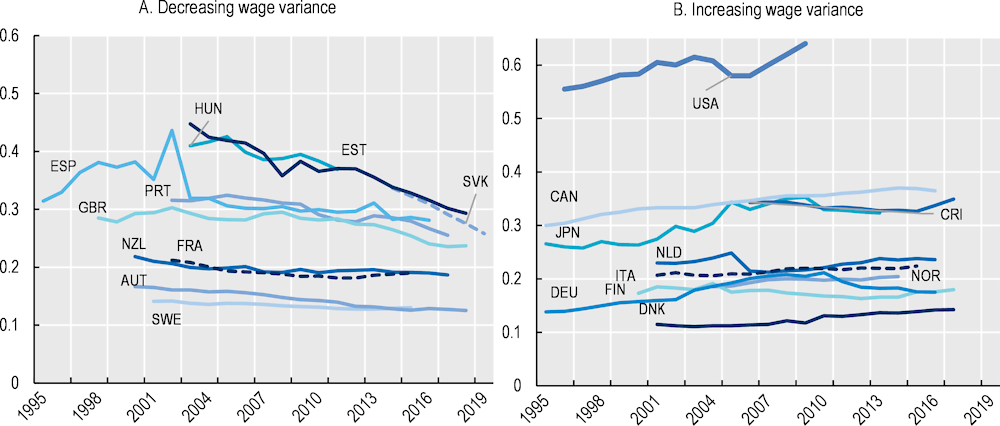

The analysis in this chapter is based on linked employer-employee data for up to 20 OECD countries (see the Annex 4.B for details on the data used).8 Since tax and social security systems differ in their administrative requirements across countries, with potentially important implications for their comparability across countries, considerable effort has been made to harmonise the data (see Box 4.3). The resulting harmonised dataset generally covers the past two decades except for Costa Rica, Hungary, Japan, Norway and the Slovak Republic, where the sample period is about one decade. Moreover, it is broadly consistent with other national and cross-country data sources in terms of levels and changes in overall wage inequality (OECD, 2021[22]).9

The countries covered in this chapter differ widely in terms of the level of wage inequality as well its dynamics over time. The sample encompasses low-inequality countries (e.g. Sweden) as well as high-inequality ones (e.g. United States), and countries with large increases in wage inequality (e.g. Germany) as well as countries with pronounced declines (e.g. Estonia). See Annex 4.B for details on the evolution in wage inequality during the period analysed.

Considerable efforts were made to harmonise the national employer-employee data used in this chapter and enhance their cross-country comparability.

The analysis is restricted to dependent employees in firms with two employees or more in the private sector. Self-employed are excluded directly where possible, while own-account workers are excluded by focusing on firms with two or more employees. Public sector firms are excluded based on their public status or when no such information is available by excluding the “public government and defence” and “education” sectors. Including the self-employed and public-sector firms would increase the importance of between-firm wage inequality at the expense of the within component, since the self-employed constitute overwhelmingly single‑worker firms and the distribution of public sector wages is typically highly compressed.

The analysis focuses on total monthly earnings since information on working time is not available in several countries. In an attempt to exclude part-timers in a consistent manner, all workers with monthly earnings below 90% of the full-time minimum wage are dropped and in the absence of a minimum wage, those below 45% of the full-time median wage. Using hourly wages for the subset of countries where this is possible does not change the qualitative results of this chapter. Earnings information is reported in gross terms, i.e. total labour cost minus employer social security contributions and based on all taxable earnings, including overtime and other bonuses. To deal with the issue of top coding at the contribution threshold in social security data, censored wages are imputed based on methods developed by Dustmann et al. (2009[23]) and Card, Heining and Kline (2013[7]).

The analysis tends to focus on the firm, the level at which wages tend to be set, rather than establishments. While most datasets link workers to their firms, some link them to their establishments (Vilhuber, 2007[24]). Although this could matter for decomposing wage dispersion into between and within-employer components, empirical work suggests that in practice the unit of observation only has a limited impact, partly because most firms have only a single establishment (Barth, Davis and Freeman, 2018[25]; Skans, Edin and Holmlund, 2009[26]; Song et al., 2018[8]).

The data typically cover the universe of workers and their employers, but in some cases represents large representative samples of workers or firms. Worker-based samples only cover a fraction of workers in a firm, introducing measurement error in average firm wages. This tends to bias within-firm wage dispersion down relative to between-firm wage dispersion. The analysis corrects for sampling error in worker-based samples using the correction proposed by (Håkanson, Lindqvist and Vlachos, 2015[27]).

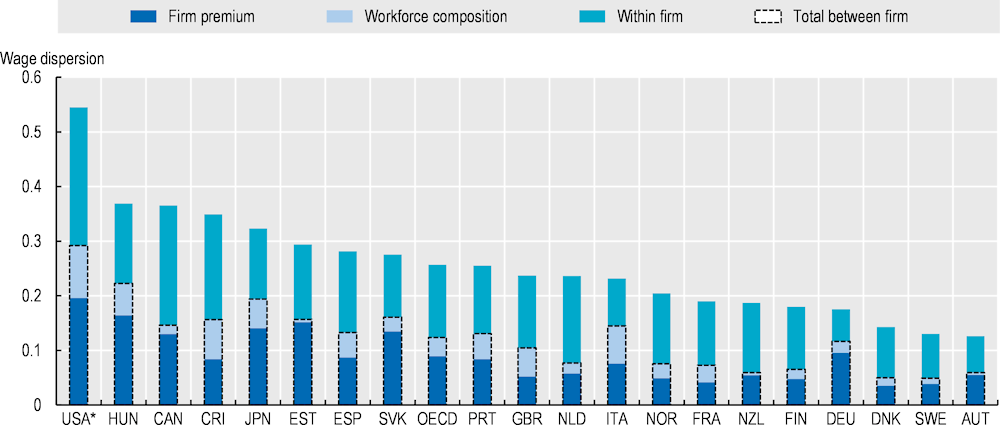

Between-firm wage inequality represents a sizeable component of overall wage inequality and this mainly reflects between-firm differences in pay for workers with similar levels of skills rather than differences in the composition of workers (Figure 4.2). On average across the 20 countries covered by this part of the analysis, between-firm wage inequality accounts for about one‑half of overall wage inequality. Firm wage premia dispersion in turn accounts for around two‑thirds of between-firm wage inequality. The remaining one‑third of between-firm wage inequality is accounted for by differences in workforce composition, i.e. the fact that firms paying higher average wages typically also employ more highly educated and experienced workers.10 Taken together, the results suggest that firms have significant leeway to set wages independently from their competitors, with firm wage‑setting practices accounting for around one‑third of overall wage inequality. Consequently, identifying and quantifying the key determinants of firm wage‑setting practices is crucial for the design of public policies to address wage inequality. A similar decomposition of the gender wage gap is presented in Box 4.4.

Note: The height of the bars denotes the level of overall wage dispersion in the latest available year (2015‑18), with the coloured parts denoting the contributions of firm premia, workforce composition and within-firm inequality. The between-firm component is equal to the sum of the firm premium and workforce composition components. OECD refers to the average of the 20 countries shown. * Figures for the United States are based on Barth et al. (2016[20])” It’s Where You Work: Increases in the Dispersion of Earnings across Establishments and Individuals in the United States”, https://doi.org/10.1086/684045.

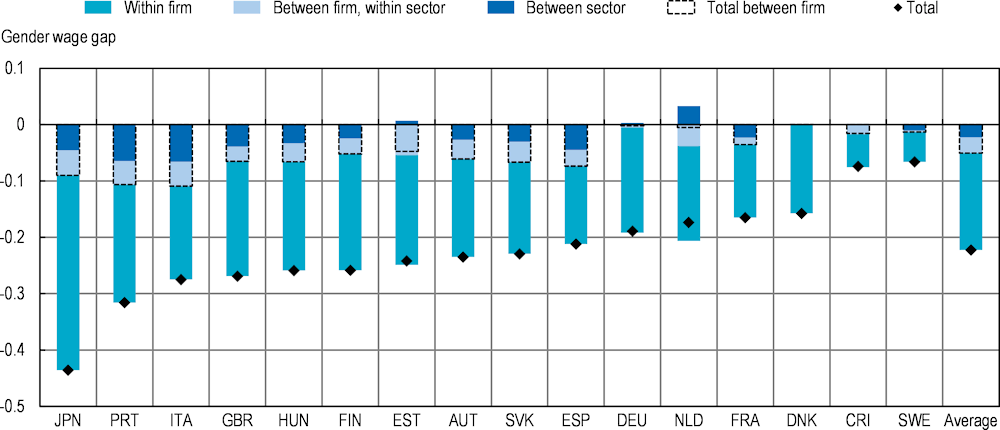

A large part of this chapter focuses on differences in wage‑setting practices between firms, i.e. differences in average pay between firms for similarly qualified workers. To the extent that men and women sort into firms with different wage‑setting practices, this can also have important implications for the gender wage gap. Additionally, there can also be important differences in pay between similarly qualified men and women within firms. Indeed, recent studies have shown that the bulk of the gender wage gap persists even after controlling for differences in skills (Goldin, 2014[5]). Systematic differences in pay between men and women with similar skills within firms reflect differences in tasks and responsibilities or differences in pay for equal work, which may result, amongst other things, from discrimination by employers or unequal opportunities for career progression more generally.

To analyse the role of firms in gender disparities, the wage gap between similarly qualified men and women is decomposed within and between firms (Figure 4.3), in a similar way as was done for overall wage inequality in the main text. About three‑quarters of the wage gap between similarly qualified men and women reflect pay differences within firms. As shown in OECD (2021[22]), this is mainly due to differences in tasks and responsibilities (e.g. men are more likely to have management or supervisory roles) and, to a lesser extent, also differences in pay for work of equal value (e.g. discrimination, bargaining). One-quarter of the gender wage gap is accounted for by differences in pay between firms due to higher employment shares of women in low-wage firms. The latter reflects both differences in wage‑setting practices between firms within industries and differences in wage‑setting practices between industries. The concentration of women in low-wage firms may be the result of a variety of factors including discriminatory hiring practices by employers or women finding it necessary to work for firms with flexible working-time arrangements despite paying lower wages. The concentration of women in particular low-wage industries may also reflect the role of past educational choices and gendered socialisation processes earlier in life.

Note: Decomposition of gender wage gap between similarly qualified men and women within firms, between firms within sectors and between sectors. The wage gap between-similarly qualified men and women is obtained from a regression of log wages on a gender dummy and flexible earnings-experience profiles by education (education is not available for Austria and Estonia) as well as decade‑of-birth dummies to control for cohort effects.

In the majority of countries, the gender wage gap between and within firms increases throughout the working life (OECD, 2021[22]). This reflects important gender differences in opportunities for career advancement, particularly around the age many women become mothers (see Box 4.6), but also the role of career breaks around the age of childbirth. Career breaks following childbirth tend to be associated with significant wage losses and consequently account for an important fraction of the “motherhood penalty”, i.e. the shortfall in wage growth following childbirth.

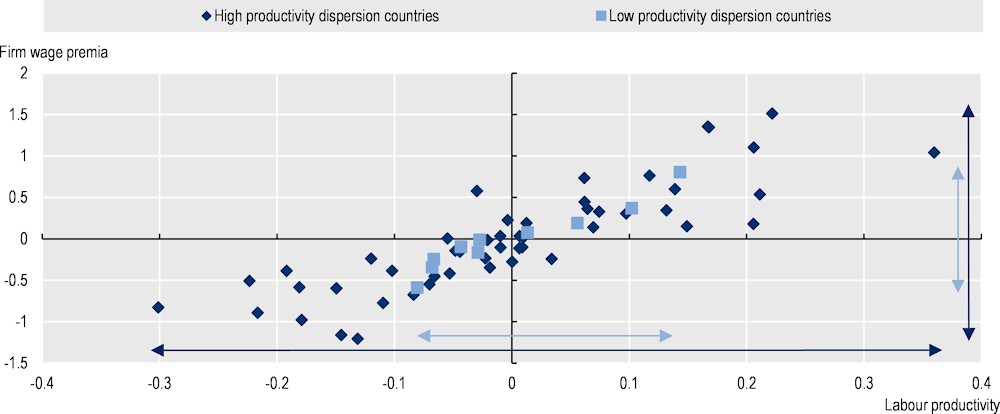

Descriptive evidence suggests that gaps in firm productivity are a key determinant of gaps in firm wage premia and that these are higher in countries with higher productivity dispersion (Figure 4.4). The figure shows that firms with higher productivity tend to pay higher wage premia. It also shows that in countries where gaps in productivity are larger (dark blue dots) – the deciles of the productivity distribution are more dispersed – there are larger gaps in wage premia between firms – the deciles of the wage premia are more dispersed.

Note: The figure shows average wage premia and average labour productivity by decile of the within-industry productivity distribution. Data are reported as deviations from country-specific means to ensure cross-country comparability and can be interpreted as percentage deviations from the country mean. Productivity is defined as log output per worker. Wage premia are the estimated firm fixed effects from a regression of log monthly earnings on firm fixed effects and observable worker characteristics. Included countries are: Costa Rica, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, and Portugal.

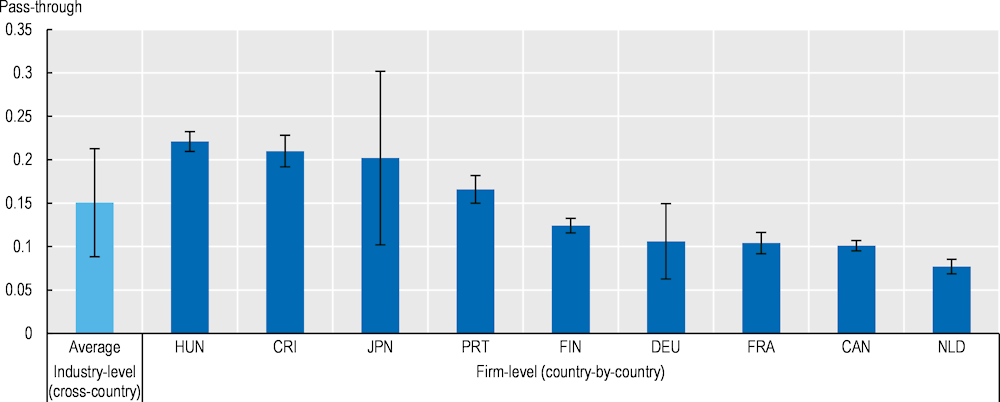

More detailed analysis shows that on average across the covered countries, around one‑sixth of productivity gaps between firms are passed on to gaps in firm wage premia, which corresponds to a pass-through coefficient of about 0.15 (Figure 4.5). This is in the range of estimates of firm-level productivity-wage pass-through in previous research (Card et al., 2018[28]).11 These estimates suggest that wage premia do not merely reflect compensating differentials related to differences in non-wage working. conditions, but also the role of labour frictions by creating a link between pay and productivity at the firm level. In such a context, low productivity firms can afford to pay lower wages and still retain workers and remain in the market, while high-productivity firms need to offer higher wages than low-productivity ones to attract the desired number of workers to overcome barriers to job mobility. Unlike in a perfectly competitive labour market, productivity differences between firms do not only translate into differences in employment but also to some extent in differences in wage premia.

One interpretation of a pass-through coefficient smaller than one is that more productive firms markdown wages more strongly from marginal productivity than less productive firms (Manning, 2020[29]). More productive firms may have more wage‑setting power because they represent a larger share of the market or because they face less competition for workers from other firms (Berger, Herkenhoff and Mongey, 2022[30]; Card et al., 2018[28]). Importantly, this not only leads to larger wage markdowns in more productive firms but also less employment in those firms, and hence a less efficient allocation of employment across firms.

Note: Productivity-wage pass-through at the firm-level refers to the elasticity of wage premia to labour productivity. The figure shows the percentage increase in wage premia associated with a 1% increase in labour productivity. The cross-country model (industry-level approach) is based on Equation 4.6 and estimated for 13 countries. The country-by-country model (worker-level approach) is based on Equation 4.5 and is estimated for a subset of countries where firm productivity is available in the linked employer-employee micro data. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals based on cluster-robust standard errors. Countries included in the cross-country analysis are as follows: Austria (2008‑15), Canada (2001‑12), Finland (2000‑12), France (2002‑15), Germany (2003‑13), Hungary (2003‑11), Italy (2001‑15), Japan (1995‑2013), the Netherlands (2001‑15), New Zealand (2001‑11), Norway (2004‑12), Portugal (2004‑12) and Sweden (2002‑12). Sample periods for the country-by-country analysis are as follows: Canada (2001‑16), Costa Rica (2006‑17), Finland (2000‑17), France (2002‑15), Germany (2000‑16), Hungary (2003‑11), Japan (1995‑2013), the Netherlands (2001‑16), Portugal (2002‑17).

There are further significant differences across countries in the extent to which productivity differences translate into differences in wage premia, with over one‑fifth of productivity gaps passed on in some countries (e.g. Hungary) but less than one‑tenth in others (e.g. the Netherlands), pointing to a potentially important explanatory role for country-wide characteristics related to the structure of product and labour markets as well as policies and institutions. The next sub-section will analyse to what extent differences in job mobility and wage‑setting institutions can help to explain cross-country differences in wage premia dispersion and cross-country differences in the link between firm performance and wage premia, such as those documented in the figure below. Another potentially important factor is the degree of wage‑setting power due to the concentration of local labour markets. This is analysed in Chapter 3 of this publication as well as in OECD (2021[22]).

Across firms within the same industry, productivity-wage pass-through tends to be higher for high-skilled workers than low-skilled workers and higher for men than women (Box 4.5). Differences in pass-through across different groups of workers contribute to both wage inequality between firms and inequality within them. With homogeneous pass-through across different groups of workers, larger productivity dispersion only raises between-firm wage inequality. By contrast, when pass-through is heterogeneous, it may additionally raise within-firm wage inequality if pass-through is larger for high-skilled workers and men who typically earn higher wages to begin with.

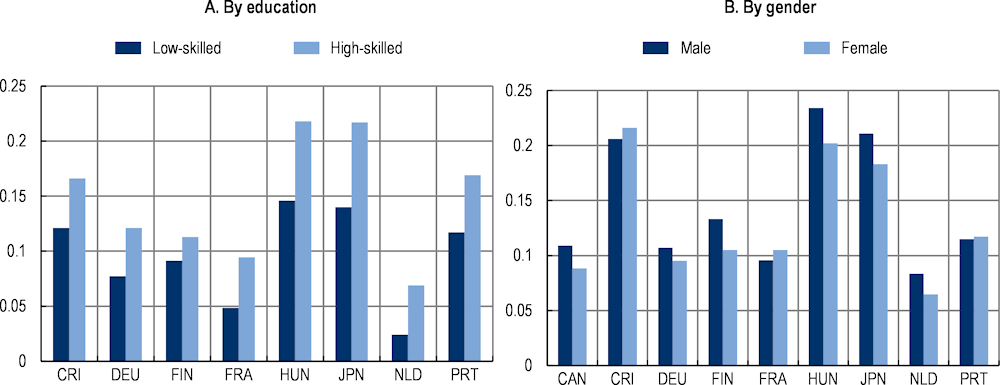

Pass-through is typically larger for high-skilled workers and men (Figure 4.6). On average across the countries analysed, pass-through for high-skilled workers is about 15% compared with about 10% for low-skilled workers. Similarly, pass-though is 15% for men compared with 13% for women. These averages hide some important differences across countries, particularly in the case of gender where the pattern is reversed in Costa Rica, France and Portugal.

Differences in pass-through across groups of workers may partly reflect differences in the responsiveness of labour demand and supply to wages. For instance, a number of empirical studies suggest that low-skilled and women workers are less mobile (Matsudaira, 2014[31]). Less mobile workers receive a larger mark-down from productivity, but also benefit less from productivity increases, as these are disproportionately shared with the most mobile groups of workers in the firm.1

Higher pass-through for skilled workers and men could also reflect complementarities between technology and skills or worker flexibility. For instance, recent evidence suggests that the gender wage gap tends to be larger in exporting firms (which tend to be more productive) than in non-exporting ones (Bøler, Javorcik and Ulltveit-Moe, 2018[32]). A related explanation could be that high-skilled workers and men have a stronger bargaining position and may be able to negotiate higher wages in high-productivity firms.

Note: Productivity-wage pass-through at the firm-level refers to the elasticity of wage premia to labour productivity. The figure shows the percentage increase in wage premia associated with a 1% increase in labour productivity. Productivity-wage pass-through is estimated using a modified version of Equation 4.5 where productivity is interacted with the worker characteristic in question. Separate regression models are estimated for each country. Skills are measured by education (tertiary, secondary and less than secondary) where available, otherwise by occupation. Each regression controls for industry fixed effects so that the coefficients can be interpreted as within-industry pass-through for different types of workers. Education and occupation not available for Canada. Sample periods for each country: Canada (2001‑16), Costa Rica (2006‑17), Finland (2000‑17), France (2002‑15), Germany (2000‑16), Hungary (2003‑11), Japan (1995‑2013), the Netherlands (2001‑16), Portugal (1991‑2009).

1. Low mobility is associated with less pass-through in the group-specific analysis, but more pass-through when focusing on productivity differences between firms. Job mobility reduces the transmission of productivity differences between firms into wage differences between firms because it reduces differences in marginal labour productivity across firms. This channel is switched off when focusing on differences in firm wage premia for different groups of workers within firms. Instead, firms have a tendency to align wages with outside options of different groups of workers and the ease with which they change jobs between firms.

The new evidence on the transmission of productivity gaps to gaps in firm wage premia in this chapter is particularly relevant in light of previous research showing that productivity dispersion has tended to rise in many OECD countries (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[1]; OECD, 2015[16]). OECD research by Berlingieri et al. (2017[2]) already pointed to a relationship between dispersion in productivity and wages, but could not establish whether this is because higher-productivity firms tend to employ higher-skilled workers or because they pay higher wages to all workers. The new evidence in this chapter suggests that productivity gaps and gaps in firm wage‑setting practices are directly linked, implying that rising productivity gaps between firms contribute to rising wage inequality.

The strong relationship between firm performance and firm pay has important implications for policies that seek to enhance inclusive growth. Before the COVID‑19 crisis, increasing productivity gaps between firms mainly reflected stagnating productivity growth among low-productivity firms rather than exceptionally high productivity growth among high-productivity ones. Hence, business-focused initiatives that help lagging firms catch up with leading firms, or leading firms to expand and create new jobs, would support growth of aggregate productivity and wages. Such initiatives may be particularly important in the wake of the COVID‑19 crisis, which may have widened productivity gaps between firms with different access to digital technologies and business models. By directly reducing gaps in firm wage-setting practices between firms, such initiatives would also contribute to lower wage inequality.

The presence of significant differences across countries in the contribution of firm wage‑premia dispersion to overall wage dispersion raises important questions about the role of policies and institutions. At a given level of labour market frictions, policies and institutions may shape the dispersion of firm productivity and thereby the dispersion of firm wage premia (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[1]). But policies and institutions may also shape the transmission of productivity to firm wage premia at a given level of productivity dispersion, either by affecting the degree of frictions in the labour market or by setting institutional limits on the dispersion of wage premia. The transmission of productivity gaps between firms into wage gaps could be more pronounced in labour markets where frictions reduce the rate of job mobility. In such a context, low-productivity firms have more scope for paying lower wages than their competitors while retaining their workers and high-productivity firms need to offer higher wage premia than low-productivity firms to overcome barriers to job mobility and achieve their optimal size. However, the extent to which wage premia vary across firms, and low-productivity firms can pay lower wage premia, also depends on the presence of wage‑setting institutions in the form of collective bargaining or minimum wages.

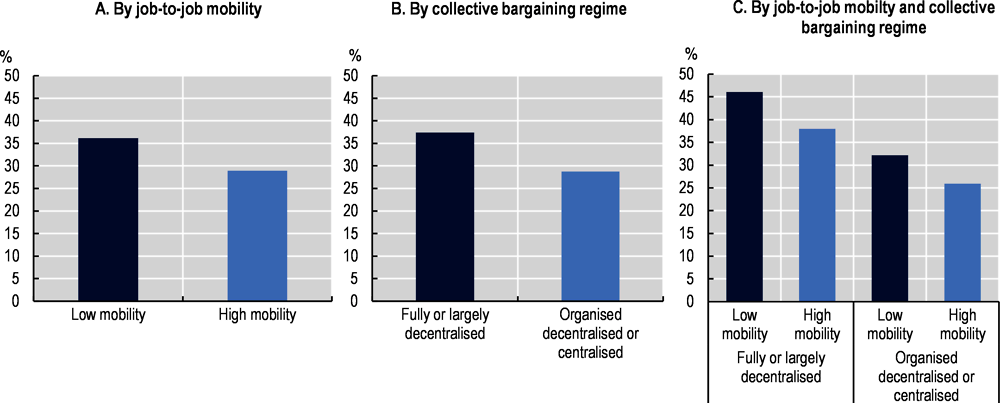

To provide a first indication of the possible role of policies and institutions in the dispersion of firm wage premia, Figure 4.7 compares the contribution of firm wage premia dispersion to overall wage inequality across different groups of countries according to the degree of job-to-job mobility between firms and the degree of centralisation of their collective bargaining systems. This suggests that job-to-job mobility – which is mainly voluntary as it excludes layoffs followed by non-employment – and collective bargaining systems characterised by predominantly sector-level bargaining and relatively high coverage are associated with a lower contribution of wage premia dispersion to overall wage dispersion (Panel A and B). Moreover, conditional on the system of collective bargaining, the share of firm wage premia dispersion tends to be higher in countries with low job mobility (Panel C).12 This is consistent with the view that low-productivity firms can survive by offering lower wages than high-productivity firms without risking to lose all their workers and that high-productivity firms offer higher wages than their low-productivity counterparts to overcome barriers to job mobility that make it harder for them to attract the desired number of workers. The results are qualitatively similar when using the level of wage premia dispersion instead of its share in overall wage dispersion.

The role of job mobility and wage‑setting institutions is analysed in more detail by combining data on firm wage premia dispersion with data on productivity dispersion at the industry level in a regression framework. This allows establishing whether the descriptive statistics presented above reflect the role of job mobility and collective bargaining for the transmission of productivity differences to wage premia or rather the extent of productivity differences in the first place. The use of a regression framework also allows controlling for a number of confounding factors and hence can provide additional credence to the associations shown.

Note: This figure plots the share of wage premia dispersion in overall wage dispersion (based on Figure 4.2) averaged by group of countries. Countries with low job mobility: France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Portugal and the Slovak Republic; countries with high job mobility: Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom. Countries with largely or fully decentralised bargaining regimes: Canada, Costa Rica, Estonia, Japan, Hungary, New Zealand, the Slovak Republic, United Kingdom, United States; countries with organised decentralised or centralised bargaining regimes: Austria, Denmark, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, Portugal, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden.

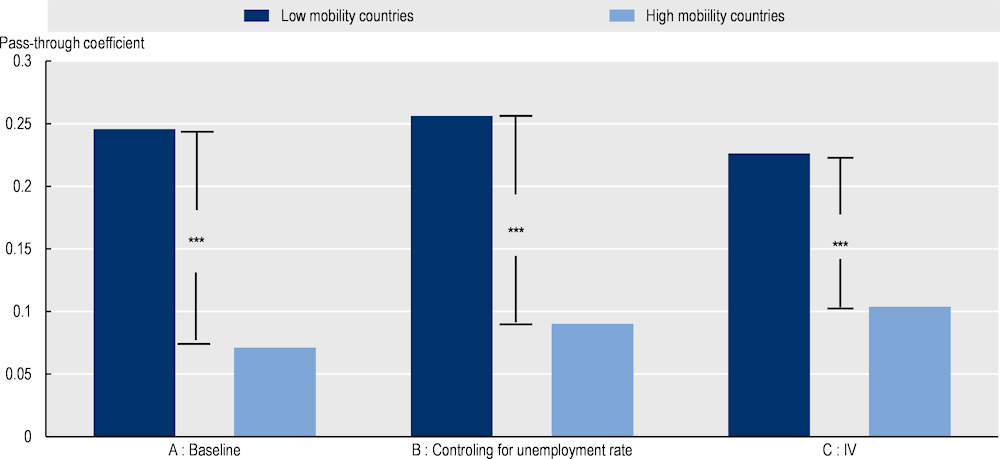

Productivity-wage pass-through is lower the higher the degree of job mobility (Figure 4.8, Panel A). As workers do not easily move from one job to another, low-productivity employers can afford paying low wages relative to high-productivity ones. Conversely, high-productivity employers need to raise wages well above those offered by low-productivity ones to attract workers from them. The effect of raising job mobility on overall wage inequality through the pass-through channel is quantitatively significant: raising job mobility from the average of countries with low job mobility to the average of those with high mobility – roughly equivalent to an increase from the 20th percentile of job mobility (Italy) to the 80th percentile (Sweden) – may reduce overall wage inequality by as much as 15%. To put this reduction in perspective, the median increase in wage inequality across countries over the period 1995‑2015 was around 10% (OECD, 2021[22]).13

The importance of job mobility for productivity pass-through is confirmed in a variety of sensitivity checks. First, job-to-job transitions may be positively correlated with the business cycle so that it may pick up the effects of low unemployment rather than the degree of labour market frictions (omitted variable bias). However, while the estimated coefficient on the interaction between productivity dispersion and unemployment is indeed statistically significant, the rate of job-to-job transitions continues to be negatively related to productivity pass-through (Panel B). Second, job-to-job transitions may be endogenous to the wage structure (endogeneity bias). For a given level of productivity dispersion, a more compressed wage structure may reduce incentives for job-to-job mobility. To address endogeneity, an instrumental variable approach is adopted that uses as instrument the product of average job mobility in all other industries in the same country and average job mobility in the same industry in all other countries. This instrument can reasonably be considered as exogenous to the wage structure in a specific industry and country. The results using this instrumental variable approach are again qualitatively unchanged (Panel C).14

Note: Productivity-wage pass-through at the firm-level refers to the elasticity of wage premia to labour productivity. Job mobility is measured by the industry-level share of job-to-job transitions in employment. This variable is noted high when its value exceeds the sample median and zero otherwise. The baseline results (Specification A) are based on Equation 4.7 where a dummy for job mobility is interacted with productivity. Specification B additionally controls for the interaction of the unemployment rate and productivity. Specification C instruments job mobility by the product of average job mobility in all other industries in the same country and average job mobility in the same industry in all other countries. Countries included in the cross-country analysis are as follows: Austria (2008‑15), Canada (2001‑12), Finland (2000‑12), France (2002‑15), Germany (2003‑13), Hungary (2003‑11), Italy (2001‑15), Japan (1995‑2013), the Netherlands (2001‑15), New Zealand (2001‑11), Norway (2004‑12), Portugal (2004‑12) and Sweden (2002‑12). *** denotes a statistically significant difference across the groups at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels. For the full results, see Annex 4.C.

The decentralisation of collective bargaining tends to increase the pass-through of firm-level productivity to wages (Figure 4.9, Panel A).15 Collective bargaining systems characterised by a predominance of industry-level bargaining (labelled “organised decentralised or centralised”) focus on industry-wide productivity in wage setting, whereas systems based on a predominance of firm-level bargaining (labelled “fully or largely decentralised”) allow for a larger differentiation of wages according to firm-specific productivity.16

Country-specific evidence on decentralisation of collective bargaining in Germany supports the cross-country evidence on the positive link between decentralisation and productivity-wage pass-through at the firm-level. In Germany, there has been a tendency towards more flexibility in wage setting at the firm-level over the past three decades, driven by an increased scope for differentiation at the firm-level within sector-level agreements and declining collective bargaining coverage. This has tended to raise the pass-through of firm-level productivity to wages (Criscuolo et al., 2021[33]).

Inversely, relatively high statutory minimum wages (relative to the median wage) tend to reduce productivity pass-through at the firm-level (Figure 4.9, Panel B). A key argument for the use of minimum wages is to contain the wage‑setting power of employers in imperfectly competitive labour markets. This ensures fair wages for workers with limited skills or a weak bargaining position, and if not set too high, also can have a positive effect on employment – see Chapter 3.17 The results presented in the figure suggest that the impact of minimum wages on overall wage dispersion, as documented for example in OECD (2018[34]), is partly driven by a reduction in wage dispersion between firms for a given level of productivity dispersion.

While strong wage‑setting institutions are likely to reduce wage inequality between firms, they could also have adverse effects. If wage floors are set too high they could reduce employment by pricing low-skilled workers out of the market. There is also a risk that they worsen the efficiency of labour allocation by dampening job mobility between firms. By suppressing wage signals in a frictional labour market, it may be more difficult for high productivity firms to attract workers and expand employment. However, recent evidence for Germany and Israel suggests that this may not necessarily be the case. Higher minimum wages may force low-productivity firms to raise productivity or exit the market, thereby reducing productivity dispersion, without any adverse effects on overall employment (Drucker, Mazirov and Neumark, 2019[35]; Dustmann et al., 2021[36]).

Note: Productivity-wage pass-through at the firm-level refers to the elasticity of wage premia to labour productivity. The graph plots the predicted pass-through elasticity when collective bargaining is centralised or decentralised and the statutory minimum wage is relatively high or low based on Equation 4.7 where a dummy accounting for wage‑setting institutions is interacted with productivity. The minimum wage incidence is measured by the ratio of the statutory minimum wage to the median wage of full-time workers. It is denoted high when its value exceeds the sample median, and zero otherwise. Collective bargaining regimes are differentiated only at the country level following the OECD taxonomy of collective bargaining regimes (OECD, 2018[34]). Country coverage: Austria (2008‑15), Canada (2001‑12), Finland (2000‑12), France (2002‑15), Germany (2003‑13), Hungary (2003‑11), Italy (2001‑15), Japan (1995‑2013), the Netherlands (2001‑15), New Zealand (2001‑11), Norway (2004‑12), Portugal (2004‑12) and Sweden (2002‑12). *** denotes a statistically significant difference across the groups at the 10%, 5% and 1% levels. For the full results, see Annex 4.C.

While job mobility is determined by a range of factors, some of which are outside the scope of public policies (discussed in detail in the next section), these findings nonetheless suggest that policies to promote job mobility could make significant inroads in narrowing gaps in firm pay policies, further reinforcing the importance of job mobility in the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis. By allowing high-productivity firms to expand more easily, they would also raise the efficiency of labour allocation and thereby aggregate productivity, employment and wages. However, some barriers to job mobility are likely to remain even after addressing policy distortions. Workers differ in their preferences for jobs in different firms, industries and geographical areas as well as their ability to perform the tasks involved, and firms differ in terms of non-wage working conditions and skill requirements, which creates inherent barriers to job mobility. Hence, mobility-promoting policies should not be seen as a silver bullet but rather as a complement to policies that aim directly at narrowing productivity gaps between firms and wage‑setting policies such as collective bargaining or statutory minimum wages.

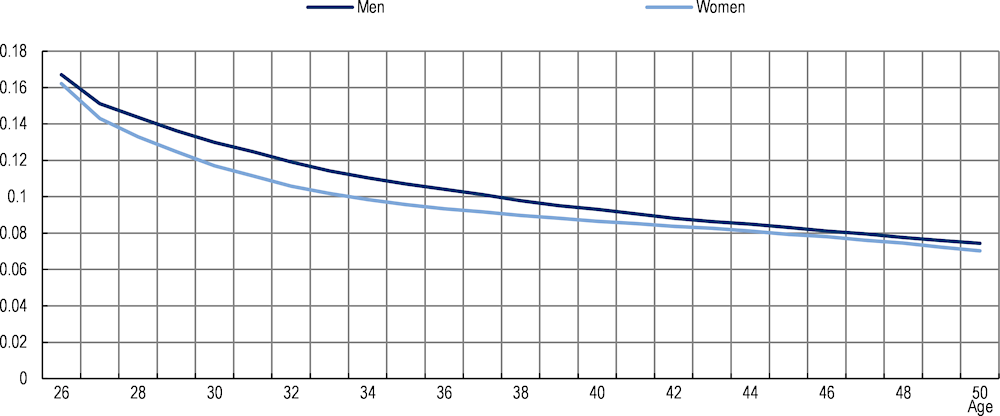

Throughout their careers, women tend to change firm less often than men. The gender gap in job-to-job mobility significantly increases around the age of motherhood, before becoming negligible after the age of 45. At the age of 32, when the mobility gap is at its highest, women are more than 10% less likely than men to change firms. Moreover, when women change firms, this is less likely to take the form of promotions. Compared with men, job transitions among women appear less often motivated by wage increases and more often by personal reasons (e.g. having more flexible working-time arrangements, working closely from home or following a partner). These differences in the incidence and nature of job mobility account for a significant fraction of the increase in the gender wage gap between firms over the working life (OECD, 2021[22]).1

Note: The figure plots the share of worker who experience a job-to-job mobility between age t and t+1 among workers present on the labour market at age t by gender. It is the average of 15 OECD countries. Reference period: 2001‑13 for Japan; 2002‑17 for Portugal; 1996‑2015 for Italy; for Hungary; 2004‑16 for Finland; 2003‑18 for Estonia; 2000‑18 for Austria; 2014‑19 for the Slovak Republic; 2006‑18 for Spain; 2002‑18 for Germany; 2010‑19 for the Netherlands; 2002‑18 for France; 2001‑17 Denmark; 2006‑17 for Costa Rica; and 2002‑17 for Sweden.

1. The lower sensitivity of women to wages can, in turn, induce monopsonistic gender discrimination based on differences in the bargaining position between men and women in the same firm (see also Chapter 3).

The findings in this chapter suggest that a comprehensive strategy to tackle excessive wage inequality requires complementing worker-centred policies with firm-centred policies. Narrowing productivity gaps between firms, promoting worker mobility between them and curtailing the wage‑setting power of firms with dominant positions in local labour markets would reduce gaps in wage‑setting practices between firms, gender pay gaps and overall wage inequality, while likely also raising productivity, wages and employment.

Firm-centred policies that reduce the productivity gap between lagging and leading firms would not only strengthen aggregate productivity growth, but also contribute to lower wage inequality by reducing pay differences between firms. The COVID‑19 crisis has put the importance of these policies into stark relief as firms with digital business models may have pulled away from those with insufficient access to digital technologies and skills. Policies that support investment in intangible assets, promote framework conditions for the digital age and improve access to digital infrastructures can help to close gaps in productivity and wages, while supporting the digital transformation (OECD, 2021[37]).

Support investment, particularly in intangible assets (e.g. managerial talent, software and R&D) that are complementary to new technologies. Easing financial market imperfections, accelerating the development of equity markets and providing more generous and targeted support to intangible investment can allow more firms, especially small ones, to seize the opportunities offered by the digital transformation (Bajgar, Criscuolo and Timmis, 2021[38]; Nicoletti, von Rueden and Andrews, 2020[39]; Demmou and Franco, 2021[40]). Scaling up public support to innovation, for instance through public procurement, grants, loans and loan guarantees, can disproportionately benefit lagging firms (Berlingieri et al., 2020[41]).

Promote framework market conditions. This involves reducing market entry barriers and strengthening the enforcement of competition policy to counter widespread declines in business dynamism and increases in market concentration, especially in digital-intensive industries where incentives for digital adoption are key (Nicoletti, von Rueden and Andrews, 2020[39]; Berlingieri et al., 2020[41]) It may also involve levelling the playing field between multinational and domestic firms in terms of tax policies and reducing differences in the scope for tax optimisation across borders (Johansson et al., 2017[42]). Appropriately designed insolvency regimes can facilitate restructuring or the orderly exit of underperforming firms (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2018[43]), promoting their catching up or the reallocation of resources from low to high-performing firms (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2016[44]).

Improve access to digital infrastructures. Digital infrastructure is a necessity for exploiting the opportunities offered by digital technologies and a strong determinant of productivity gains (Gal et al., 2019[45]). However, access to communication networks is still uneven, hampering the take up of digital technologies and technology diffusion. Fiscal incentives to encourage private investment in underserved areas, direct public investment where private investment is not commercially viable, and ensuring competition in telecommunication markets would improve and widen access to communication networks and support the digital transformation of lagging firms (OECD, 2020[46]).

Policies that promote job mobility between firms reduce between-firm wage gaps while enhancing the allocation of employment across firms. Job mobility could be enhanced by strengthening adult learning and activation policies, reforming labour market and housing policies, and supporting telework. Enhancing job mobility is particularly important for the recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis to mitigate labour shortages and support the reallocation of employment from shrinking or unviable businesses to those with better growth prospects.

Strengthening adult learning and taking a more comprehensive approach to activation that goes beyond promoting access to employment would help workers find better jobs in other firms and at the same time reduce productivity gaps between them, yielding double dividends (OECD, 2021[14]). For instance, public employment services in the form of job-search assistance, training and career counselling could be made available to workers in jobs who would like to progress in their careers but face significant barriers in moving to better jobs, including people in non-standard forms of work, workers who are currently employed but lack relevant skills or live in lagging regions and workers in jobs supported by job retention schemes. This would require a more active role of public employment services in advising workers on adult learning opportunities and monitoring evolving skills requirements and a better co‑ordination between public and private providers of employment services (Langenbucher and Vodopivec, 2022[47]). At the same time, continued investments are needed to enhance the training infrastructure, including through individual training accounts, and promote a culture of learning more generally.

Limiting regulatory barriers to job mobility in labour and housing markets can foster transitions across firms, occupations and regions. This includes reforming overly restrictive occupational entry regulations (Bambalaite, Nicoletti and von Rueden, 2020[48]); promoting the portability of social benefits and severance pay entitlements (Kettemann, Kramarz and Zweimüller, 2017[49]); limiting the inappropriate use of non-compete or non-poaching agreements (Krueger and Ashenfelter, 2018[50]; OECD, 2019[51]) (see Chapter 3).

Mobility across geographical areas could be fostered by reforming housing policies, including by redesigning land-use and planning policies that raise house price differences across locations, reducing transaction taxes on selling and buying a home, and relaxing overly strict rental regulations (Causa and Pichelmann, 2020[52]). Social policies in the form of cash transfers and in-kind expenditure on housing could also support residential mobility by raising the affordability of housing for low-income households, especially if such expenditure is designed in such a way that benefits are fully portable across geographical areas.

An expansion of telework could partly compensate for limited geographical mobility. A significant fraction of jobs can potentially be conducted remotely – between one‑quarter and one‑third of all jobs according to some estimates (Dingel and Neiman, 2020[53]; Boeri, Caiumi and Paccagnella, 2020[54]; OECD, 2020[55]) – potentially raising job opportunities for workers and reducing costs to move from one job to another. Promoting telework will require regulating the right to request telework – where this does not exist – and the conditions under which telework arrangements are implemented (OECD, 2021[56]); strengthening digital infrastructure to increase network access and speed for all workers as well as digital adoption by firms; enhancing workers’ ICT skills through training; as well as raising employers’ management capabilities through the diffusion of managerial best practices (Nicoletti, von Rueden and Andrews, 2020[39]; OECD, 2020[55]). Notably, the use of teleworking during the pandemic was higher in countries where there was an enforceable right to request teleworking, and highest in countries where this right to access was granted through collective bargaining (OECD, 2021[56]).

While removing barriers to job mobility can reduce wage inequality and enhance the allocation of jobs across firms, some barriers to job mobility are likely to remain even after addressing policy distortions. Jobs differ in the skills they require and the way they are organised. At the same time, workers differ in their preferences for different jobs and the ability to perform the tasks involved, which create inherent barriers to job mobility. Hence, mobility-promoting policies should be complemented with policies that aim directly at containing the excessive wage‑setting power of dominant firms (see also the discussion in Chapter 3).

Wage‑setting institutions in the form of minimum wages and collectively negotiated wage floors could help to contain the wage‑setting power of firms in labour markets with limited job mobility (OECD, 2019[19]). In areas and occupations where wages are well below workers’ productivity, this could even increase employment by raising labour market participation among people who are unwilling to work at current wages.18 However, it is important to set wage floors at levels that are consistent with workers’ productivity, so as not to have dis-employment effects. This risk could be reduced by combining centralised collective bargaining with sufficient scope for further negotiation at the firm level, and allowing for regional variation in minimum wages and specific minima for very young workers. Ongoing research based on a comparison between Norway and the United States further suggests that wage compression between firms does not necessarily reduce the efficiency of labour allocation between firms (Hijzen, Lillehagen and Zwysen, 2021[57]). The key to achieve high productivity through an efficient allocation of labour is to complement wage‑setting institutions that constrain the ability of firms to pay different wages for similar workers with measures that promote innovation in low productivity firms and strengthen job mobility.

Competition authorities could step up enforcement efforts against anti-competitive agreements in labour markets, including wage fixing, no-poaching agreements and non-compete covenants (OECD, 2019[51]). Such anti-competitive agreements reduce opportunities for job mobility and increase the wage‑setting power of firms. Wage‑fixing represents a form of collusion in which employers agree on the wages and non-wage benefits of specific groups of workers. This may involve an explicit agreement or tacit co‑ordination, based on the exchange of information on compensation with potential competitors. Another way employers may collude is by agreeing to refrain from poaching each other’s workers. A third form of employer collusion is the use of non-compete covenants in employment contracts that prevent employees from working for their employer’s competitors, usually for a limited time or in a specific geographical area. These issue are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

The excessive wage‑setting power of dominant firms in local labour markets could further be addressed by explicitly integrating labour market power considerations into merger control. If merger control authorities focus exclusively on product market developments, this may not be sufficient to limit employers’ wage‑setting power when the definition of the relevant labour market does not perfectly track the definition of the relevant product market. For instance, a competition authority concluding that a merger between two companies does not constitute a threat to competition because there is a sufficient number of competitors (including from abroad) may fail to detect the fact that two companies are hiring in the same local labour market.

This chapter examines the role of differences in performance and wage‑setting practices across firms in wage inequality. The main finding is that, on average across the 20 countries covered in the analysis, differences in wage‑setting practices across firms account for around one‑third of overall wage inequality and one‑quarter of the gender wage gap. To some extent, gaps in firm wage‑setting practices reflect gaps in productivity that are transmitted to pay when frictions prevent workers to move costlessly between firms. But to some extent, they also reflect differences in the wage‑setting power of firms operating in labour markets with different competitive environments and wage‑setting institutions.

From a policy perspective, the main insight is that firm-centred policies should be a key element of a comprehensive strategy to promote broadly shared economic growth. Supporting the productivity catch-up of lagging firms would not only raise aggregate productivity and wages but also reduce wage inequality. Promoting worker mobility between firms would reduce wage inequality at any given level of productivity dispersion while enhancing the allocation of employment across firms. Curtailing the wage‑setting power of firms with dominant positions in local labour markets would reduce gaps in wage‑setting practices between firms, gender pay gaps and overall wage inequality, while likely also raising productivity, wages and employment.

By placing firms at the centre of the analysis, this chapter helps to broaden the policy debate on wage inequality and in doing so fosters a whole‑of-government approach to wage inequality and inclusive growth more generally. While skills policies remain crucial to ensure that skill demands and supplies remain well aligned, many other policies can have significant implications for wage inequality and these need to be taken into account when designing policies that seek to promote inclusive growth.

[21] Abowd, J., F. Kramarz and D. Margolis (1999), “High wage workers and high wage firms”, Econometrica, Vol. 67/2, pp. 251-333.

[43] Adalet McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2018), “Design of insolvency regimes across countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1504, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d44dc56f-en.