Sandrine Cazes

Clara Krämer

Sebastien Martin

Chloé Touzet

Sandrine Cazes

Clara Krämer

Sebastien Martin

Chloé Touzet

Working time is both a key element of workers’ lives and a production factor. Understanding how working time policy relates to well-being and economic outcomes is thus crucial to design measures balancing welfare and efficiency concerns. Evidence so far has largely focused on the use of maximum hours’ regulation to prevent detrimental effects on workers’ health, and the effect of normal hours reductions on employment levels. This chapter brings two new perspectives: first, it accounts for the fact that workers’ well-being is an increasingly central societal objective of working time policies, and therefore considers well-being effects alongside productivity and employment effects. Second, it accounts for the use of flexible hours and the development of teleworking in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis and considers their impact on well-being, productivity and employment. Building on these analyses, the chapter discusses the potential of various working time policies to enhance non-material aspects of workers’ well-being such as health, work-life balance and life satisfaction while preserving employment or productivity.

Working time is a key component of people’s working lives. Regulating its duration and its organisation is necessary to correct market failures leading to an inefficient allocation of working time and inadequate workers’ protection and to prevent negative externalities linked to long hours or variable schedules. Further, working time regulation can help − and historically has helped − enhancing non-material aspects of workers’ well-being. At the same time, working time being a production factor, policies affecting it will also impact employment, wages and productivity, and ultimately workers’ material well-being. On that basis, this chapter discusses the potential of various working-time policies to enhance workers’ well-being, while accounting for their possible effects on employment and productivity. Although data availability and heterogeneity across countries prevent generalisations, interesting insights emerge.

The empirical literature suggests a close relationship between working long hours and poor health outcomes (particularly when workers have little control on their work schedule), but offers less-clear-cut results for other aspects of workers’ non-material well-being, such as life satisfaction. The literature moreover usually points to beneficial effects of reducing normal weekly hours on non-material aspects of workers’ well-being, if the reduction does not result in higher work intensity.

New empirical evidence for selected OECD countries confirms that working long hours (e.g. more than 45 hours per week) tends to be associated with a lower probability to report good health outcomes in the majority of selected countries. Yet, working a reduced amount of hours (e.g. less than 35‑30 hours per week) is not necessarily associated with a higher probability to report good health outcomes across countries. In fact, an inverse U-shape pattern emerges in Australia, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and pooled European data, where working less than 35‑30 hours is also associated with lower health outcomes. By contrast, the relationship between working hours and other non-material well-being outcomes is generally linear, e.g. working long hours decreases the probability that a worker is satisfied with her life, job, and free time, while working a reduced amount of hours increases these probabilities, except for France.

These results suggest that besides regulating maximum hours and overtime, a reduction of normal hours may also be considered as a possible lever of working time policy to enhance workers’ non-material well-being under certain conditions. In particular, such reductions in normal hours should be considered taking into account their potential impact on employment and productivity. To shed light on this, the chapter next analyses the effects of legislative reforms reducing normal hours on employment and productivity in European countries, as well as the relationship between episodes of reductions of contractual hours at firm level observed in the data and the growth in employment, average wage and productivity in Germany, Korea and Portugal.

Results from the analysis of legislative reforms implemented in Belgium, Italy, France, Portugal and Slovenia between 1995 and 2007 reveal a significant reduction of average yearly working hours for those who were affected by the reform, but no significant effects on employment, and similar −yet still insignificant effects− on wages and productivity. The absence of significant effect on employment may at least in part stem from heterogeneous effects cancelling each other at the aggregate level. Importantly, these reforms took place with constant monthly wages, thus leading to higher hourly wages, but they did not systematically include compensatory measures (such as e.g. public subsidies) for firms to limit possible adverse impacts of rising labour costs.

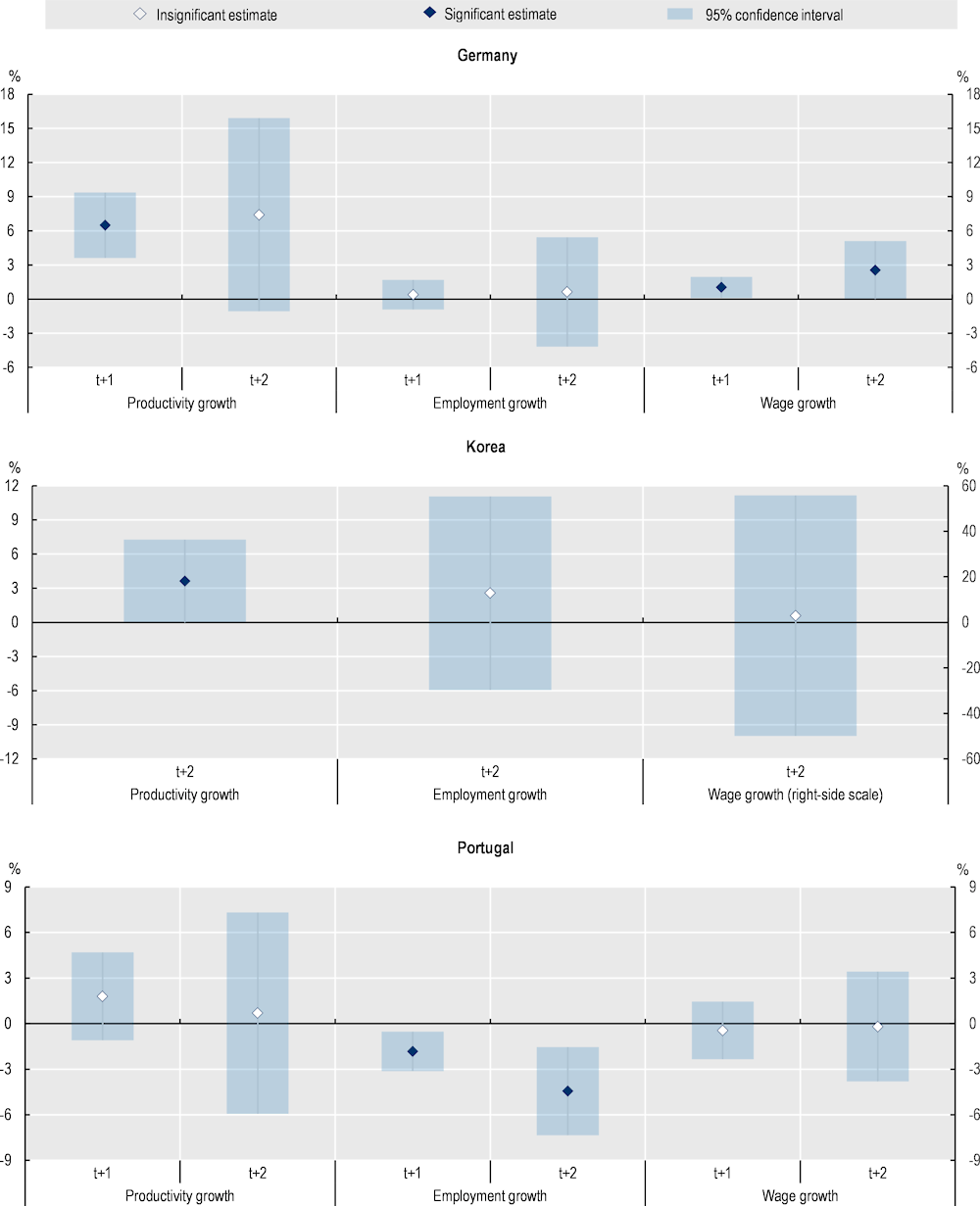

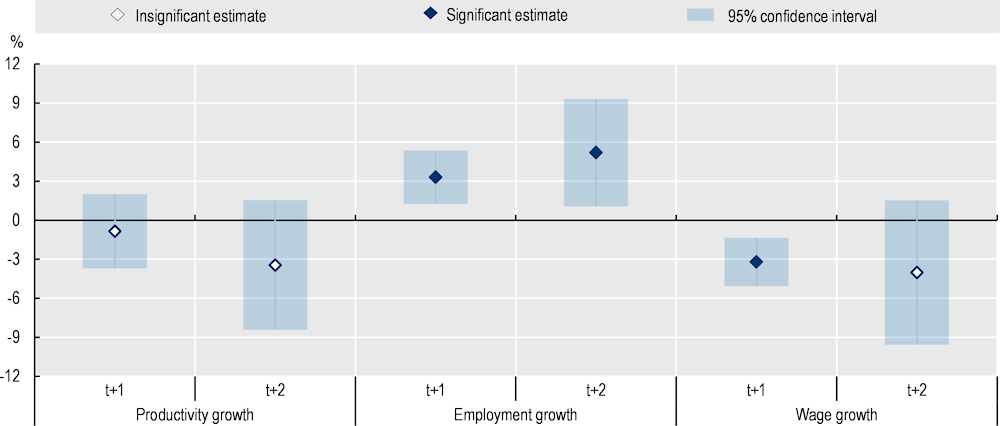

Firm-level analyses of the relationship between observed contractual hours reductions and economic outcomes in Germany, Korea and Portugal − point to contrasted results, but suggest that virtuous circles might exist in some instances, whereby the reduction in hours generates a productivity increase that limits the rise of unit labour cost and therefore prevents the potentially negative effect on employment growth. Understanding why such virtuous circles manifest in some cases and not in others should be investigated in future research, but could be explained by national differences in the institutional context of the decision-making process, notably well-functioning collective bargaining and strong social dialogue.

These two empirical approaches assess two different types of hours reduction. The first one looks at the employment and productivity effects of national legislative reforms generally applying to all firms and sectors and widely anticipated by employers. The second one focuses on contractual hours reductions at firm-level that might result from legislative reforms, collective bargaining or unilateral decisions from employers. Yet, despite their differences, the results emerging from these approaches are consistent and aligned with the majority of the existing literature. Reducing working hours (at constant monthly wage) might preserve employment on average if the impact on unit labour cost remains limited (either due to sufficient induced productivity gains or to public subsidies to affected firms/sectors). These results may also arise if the reduction of hours takes place in a pre‑existing situation of labour market monopsony (where the existence of a profit rent means that firms can absorb higher labour costs, see Chapter 3).

Outside the case of firms enjoying monopsony power, the results of this chapter point to the need to fully factor in the possible impact on unit labour costs when considering reductions of normal hours. This could be done through dedicated accompanying measures, or by designing the reduction so that it taps into the productivity-enhancing potential of the reform. Careful attention should also be devoted to the timing, conditions of implementation and scope of the reduction which are all likely to influence the effect of the reduction.

Workers’ ability to work flexible hours, i.e. to autonomously decide their starting and finishing times, is associated with better non-material well-being for all outcomes considered – both in the literature and in new individual-level evidence available for Australia, Germany, Korea, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (although to varying degrees between countries). The literature to date also points to positive associations with employment, wages and productivity. New evidence on German firms adopting flexible hours suggests that this arrangement might indeed boost employment without significantly affecting productivity per worker. Firms choosing flexible hours also see a decrease in average wage growth – suggesting a possible trade‑off between wage increases and higher autonomy in determining hours.

In contrast to flexible hours, the link between teleworking and workers’ non-material well-being varies for different outcomes and across countries – both in the literature and in the new empirical evidence presented for Australia, Switzerland and in the United Kingdom. Empirical results show a negative association with self-assessed health, positive associations with life‑ and job satisfaction and contrasting associations with work-life balance, which is particularly high for teleworkers in Australia, but very low for teleworkers in Switzerland. As for productivity and employment, associations with teleworking in the empirical literature to date are generally positive, especially in terms of attracting and retaining workers, as well as increasing female labour force attachment.

Working time is a defining aspect of working lives.1 How many hours workers spend at work, how their working hours are scheduled, and how much control they have over them can affect their physical and mental health, work-life balance, job satisfaction and performance. More generally, working time directly affects workers’ allocation of time between work and other activities, such as leisure, which itself is likely to influence their life satisfaction. At the same time, working time is a key production factor that can affect economic outcomes such as employment, productivity and wages, which in turn impact workers’ material well-being. Therefore, understanding how working time policy relates to workers’ well-being and economic outcomes is crucial to identify and carefully design measures balancing welfare and efficiency concerns.

Regulating working time duration and organisation is necessary to correct possible market failures (due e.g. to asymmetry in market power between workers and employers) leading to an inefficient allocation of working time and an inadequate protection of workers’ health and work-life balance, and to prevent negative externalities linked to excessive working hours or variable schedules. Historically, it has also helped enhancing several aspects of workers’ well-being, notably through regulations reducing working time. Yet, this historical trend towards shorter working hours which has been accompanied by productivity gains and could be traced back to the 19th century in most OECD countries has considerably slowed down – if not almost halted in a number of countries (OECD, 2021[1]). While working time is regulated at various levels across OECD countries, statutory regulations on working time have the most effect on actual working time in OECD countries, even where derogations at lower levels of governance are possible (OECD, 2021[1]).

Policy makers interested in using working time measures as a lever to influence workers’ well-being outcomes have several tools at their disposal: they can regulate the maximum number of hours that a worker can legally work in a given period of time and define a premium wage for overtime work; they can regulate the number of normal hours regarded as representing a full-time job; they can allow for greater flexibility in working time arrangements and provide or modify incentives for using various working time arrangements – see OECD (2021[1]). The pros and cons attached to each of these tools, and how they might affect workers’ well-being as well as employment, wages and productivity need to be factored in when designing working time policy.

Policy debates and related empirical evidence on working time policy so far have generally focused on the regulation of maximum hours to prevent any detrimental effects on workers’ health, and on the reduction of normal weekly hours, with a view to increasing employment. This chapter brings in two new perspectives: first it accounts for the fact that workers’ well-being is an increasingly central societal objective of working time policies, and therefore considers well-being effects alongside productivity and employment effects. In particular, in line with the OECD well-being framework, it distinguishes material aspects (earnings, job status, etc.) and non-material aspects (health, work-life balance, life satisfaction, etc.) of workers’ well-being (OECD, 2015[2]). Second, it accounts for the use of flexible hours and the development of teleworking, given its prevalence and relevance in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis, and considers the impact of these schemes on non-material well-being, productivity and employment. Identifying virtuous circles between welfare and efficiency objectives could help square the working time policy circle.

The chapter starts by exploring the relationship between working time (maximum and normal hours, part-time, flexible hours, and teleworking2) and a set of selected measures of non-material well-being, namely health status (both mental and physical), work-life balance and life and job-satisfaction. Drawing on a combination of literature reviews and on analyses of individual-level data, it first investigates how hours worked, flexible hours arrangements, part-time work and teleworking relate to the above‑mentioned non-material well-being outcomes, to identify potential levers of well-being enhancement (Section 5.1). As results suggest that reducing normal weekly hours and fostering the use of flexible hours and teleworking might in some circumstances lead to well-being gains, the chapter next turns to analysing the impact of these policies on employment, wages and productivity (Section 5.2). To shed some light on these key issues, Section 5.2 next analyses the effects of national legislative reforms that reduced normal weekly hours on employment and productivity in various European countries, before studying the relationship between concrete episodes of reductions of contractual hours at firm level and the growth of productivity, average wage and employment, in Germany, Korea and Portugal where data are available. Finally, the chapter concludes by bringing together all the results and discussing policy options while outlining the importance of timing, scope and careful design and implementation.

The amount of time spent at work, how hours are scheduled and the relative flexibility workers have in determining these schedules – see OECD (2021[1]) – have direct implications for several outcomes of workers’ non-material well-being, such as health status, work-life balance and life and job satisfaction. Working time policy might be able to improve these outcomes. Drawing on a mix of literature reviews and new analyses using individual-level data in OECD countries, this section explores the relationship between working hours (both normal hours and overtime), flexible hours, part-time work and teleworking and a set of non-material well-being measures (health status, work-life balance and job- and life satisfaction), to identify possible levers of well-being gains.

The relationship between time spent working and workers’ well-being (both material and non-material) has initially been investigated in the epidemiology and occupational health literature that assesses the effects of working long hours3 on both mental and physical health (Beswick and White, 2003[3]; Sparks et al., 1997[4]). This literature is plagued by the identification problem known as “the healthy worker effect” – a problem of reverse causality when assessing the impact of working time on health, since healthy workers are more likely to be in employment and to be able to work long hours than unhealthy ones – and by the difficulty of dealing with unobserved confounding factors.4 Nonetheless results usually suggest a close relationship between long hours and poor health outcomes. Working long hours and overtime are associated with unhealthy behaviours, such as alcohol consumption, smoking and lack of exercise (Ahn, 2016[5]). Long hours are also directly related to poor physical health outcomes, such as cardiovascular diseases or stroke (Kivimäki et al., 2015[6]) and considered as one of the major risk factors for workplace accidents (Dembe, 2005[7]; Vegso et al., 2007[8]). Beyond physical health and workers’ safety, long working hours are also associated with stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in young Korean employees (Park et al., 2020[9]) and also more generally with negatively impacted cognitive functions (Virtanen et al., 2008[10]). Research has also explored the relationship between long hours and other well-being outcomes, such as life satisfaction, and found less clear-cut results. Hamermesh at al. (2017[11]) find for instance beneficial effects of overtime reduction on workers’ life satisfaction in Japan and Korea; but other studies find that long hours are not necessarily related to lower well-being outcomes, notably for men or fathers (Hewlett and Luce, 2006[12]; Gray et al., 2004[13]). On the other side of the hour spectrum, working a low number of hours also has an impact on workers’ well-being, mainly because it results in insufficient earnings – see for example Friedland and Price (2003[14]) and Heyes and Tomlinson (2021[15]). This idea is also mentioned in the literature on involuntary part-time work, which is further discussed in the next section on working time arrangements.

Beyond the negative well-being impacts of both long and insufficient working hours, authors have also explored the relationship between a reduction of normal weekly working hours and well-being outcomes. While results vary by outcomes considered, the scope of the hours reduction and the extent to which wages are adjusted, studies find that reducing hours tend to positively affect non-material well-being. Lee and Lee (2016[16]) exploit a quasi-natural experiment in Korea, where normal hours were reduced gradually from 44 to 40 hours at different times by industry and establishment size between 2004 and 2011, and find that on average a one‑hour reduction in normal weekly working hours in Korea significantly decreases the injury rate by about 8%. Berniel and Bietenbeck (2020[17]) provide causal evidence on smoking reduction and lower body mass index for France in the context of the reduction of the 35 hours reform. Lepinteur (2019[18]) shows beneficial effects of normal hours reduction on job and leisure satisfaction of workers in France and Portugal, especially for women and workers with heavy family burden. However, other studies point to less clear effects on well-being should the working time reduction result in a higher time pressure on workers (Askenazy, 2004[19]). Rudolf (2013[20]) finds for instance that a reduction of normal hours in Korea did not have the expected positive impact on workers’ job and life satisfaction and suggests that the reduction in hours was offset by greater work intensity.

Further, other factors beyond work intensity are found to interact in the relationship between working time and workers’ non-material well-being, including workers’ control of their schedules and the mismatch between their desired and actual working hours. The extent to which workers can choose or control the number of hours they work is key in determining how detrimental long hours might be for their health (Bassanini and Caroli, 2015[21]; Bell, Otterbach and Sousa-Poza, 2012[22]; Burke et al., 2009[23]; Caruso et al., 2006[24]; Frijters, Johnston and Meng, 2009[25]). Salo et al. (2014[26]) for instance find that for those working 40 hours a week, less control over working time is associated with greater sleep disturbances in Finland (while sleep disturbances were high irrespective of the degree of workers’ control for those working longer hours). Looking then at the link between working hours mismatch (i.e. the difference between workers’ preferred working hours and their actual hours) and job satisfaction, Grund and Tilkes (2021[27]) find a negative link between working time mismatch and a positive − moderating − link between working time autonomy and job satisfaction in Germany. Moreover, Holly and Mohnen (2012[28]) find that the desire to reduce hours has a negative impact on satisfaction although if overtime is appropriately compensated, satisfaction rises and working time mismatch decreases.

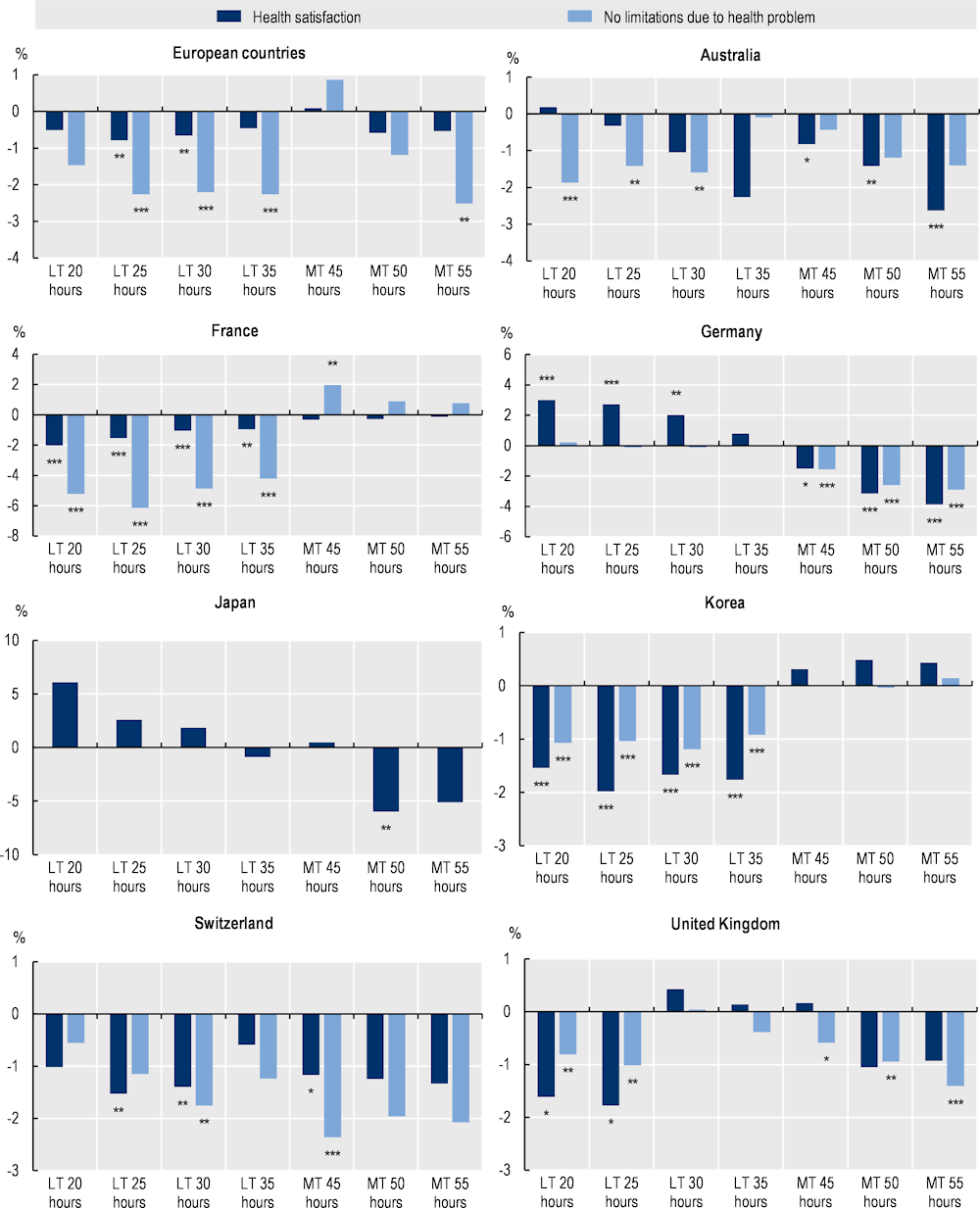

In order to shed further light on the results of this literature review, Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.2 present new OECD empirical evidence exploring the relationship between actual weekly hours in the main job and several measures of workers’ non-material well-being, namely self-assessed health outcomes, life and job satisfaction and satisfaction with free time (as a proxy for work-life balance). Pooled results for European countries are based on European Social Survey (ESS) data, while results for Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Switzerland and the United Kingdom draw on country-specific, individual-level panel data. Results presented in the figures correspond to the marginal effect of working less (or more) than a particular threshold, compared to those working more (or less) than this threshold: for instance, the left light blue bar in the first graph in Figure 5.1 corresponds to the difference in likelihood (in percentage) of being satisfied with one’s health when working less than 20 hours per week, compared to when working more than 20 hours per week in European countries represented in the ESS data.

In terms of workers’ health, (Figure 5.1), results generally confirm the negative relationship found in the literature between working long hours and poor health outcomes in the majority of selected countries. Working more than 45 hours reduces one’s probability to be satisfied with one’s health in Australia, Germany, Switzerland and Japan (for those working more than 50 hours). Those working more than 45 hours are also less likely to report facing no limitations in their work due to health problems in Germany, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and countries covered by the ESS data (for those working more than 55 hours). At the same time, there is no significant effect of working long hours on workers’ health when it is measured by health satisfaction in the ESS data, France, Korea and the United Kingdom, or by health-related limitations in Australia and Korea. Surprisingly, working more than 45 hours even increases the probability of reporting no health-related limitations in France – which might be due to the self-selection issues discussed in note 4, survey biases, or cultural differences affecting subjective well-being survey items differently in different countries.

The relationship with health outcomes is however less clear-cut on the other side of the hours spectrum, and working a short amount of hours (starting from less than 35 hours in some cases) is not associated with a linear improvement of workers’ health across countries. The probability to be satisfied with one’s health is higher for those working less than 30, 25 or 20 hours in Germany, compared to those working more than these thresholds. Health satisfaction is not significantly related to any of the short hours’ threshold in Australia. By contrast, the probability to be satisfied with one’s health is lower for those working less than 25 hours in France and Korea, 30 hours in the ESS data and Switzerland and less than 25 hours in the United Kingdom, compared to those working more than these respective thresholds. Similarly, workers doing less than 35 hours a week in the ESS data and France, 30 hours a week in Australia and Switzerland and less than 25 hours a week in the United Kingdom are less likely to declare facing no health-related limitations, compared to those working more than these respective thresholds (while the relationship is not significant in Germany). Of course, these results at the bottom of the hours distribution could be due to some form of healthy worker effect: workers in poor health may be more likely to work fewer hours.

Overall, these findings primarily emphasise heterogeneity across OECD countries. Yet they also confirm the existence of a link between long hours and poor health outcomes in the majority of the selected countries. In addition, they reveal that health outcomes are not linearly related to hours, and not always improving for those working shorter hours. Rather, an inverted U-shaped pattern emerges in some countries (ESS data, Australia, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) when considering health outcomes, with a lower likelihood to be satisfied with one’s health, and to declare no health-related limitations at both ends of the spectrum.

Note: Marginal effects (at the mean) are derived from individual probit regressions (i.e. regression of an individual’s actual hours worked, measured as a dummy variable capturing whether the individual is in a particular hours bracket, on this individual’s self-assessed health outcome). Regressions are estimated using repeated cross-section data with robust standard errors and controlling for year fixed effects, demographic characteristics, household composition and income, job characteristics (including contract duration) and life events. Categories of actual hours worked shown in this chart refer to dummy variables defined using an increasing threshold of actual hours worked, from 20 hours to 55 hours. Health satisfaction is also coded as a dummy variable; employees are considered satisfied with their health if their answer to the health satisfaction question is between 6 and 10 on a scale from 0 “not at all satisfied” to 10 “completely satisfied”. For the “European countries” (Panel A) France and Korea, health satisfaction refers to employees assessing that they are in good or very health condition. There are no data on limitations due to health problems for Japan. For further details on definitions of health satisfaction, limitations due to health problems and regression specifications by country, see Annex 5.A. “European countries” (Panel A) refers to pooled data of 24 countries: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. ***, **, *: statistically significant at the 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. LT: Less than; MT: More than.

Reading example: In Australia, employees working more than 55 hours per week are expected to be 2.6% less likely satisfied by their health compared to those working 55 hours or less per week.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Social Survey (ESS, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for the European countries; the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA, 2005‑19) for Australia; the enquête Statistiques sur les ressources et conditions de vie (SRCV, 2010‑19) for France; the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for Germany; the Japan Household Panel Survey (KHPS/JHPS, 2010‑17) for Japan; the Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS, 2005‑19) for Korea; the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, 2004‑19) for Switzerland; and University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, Understanding Society: Waves 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for the United Kingdom.

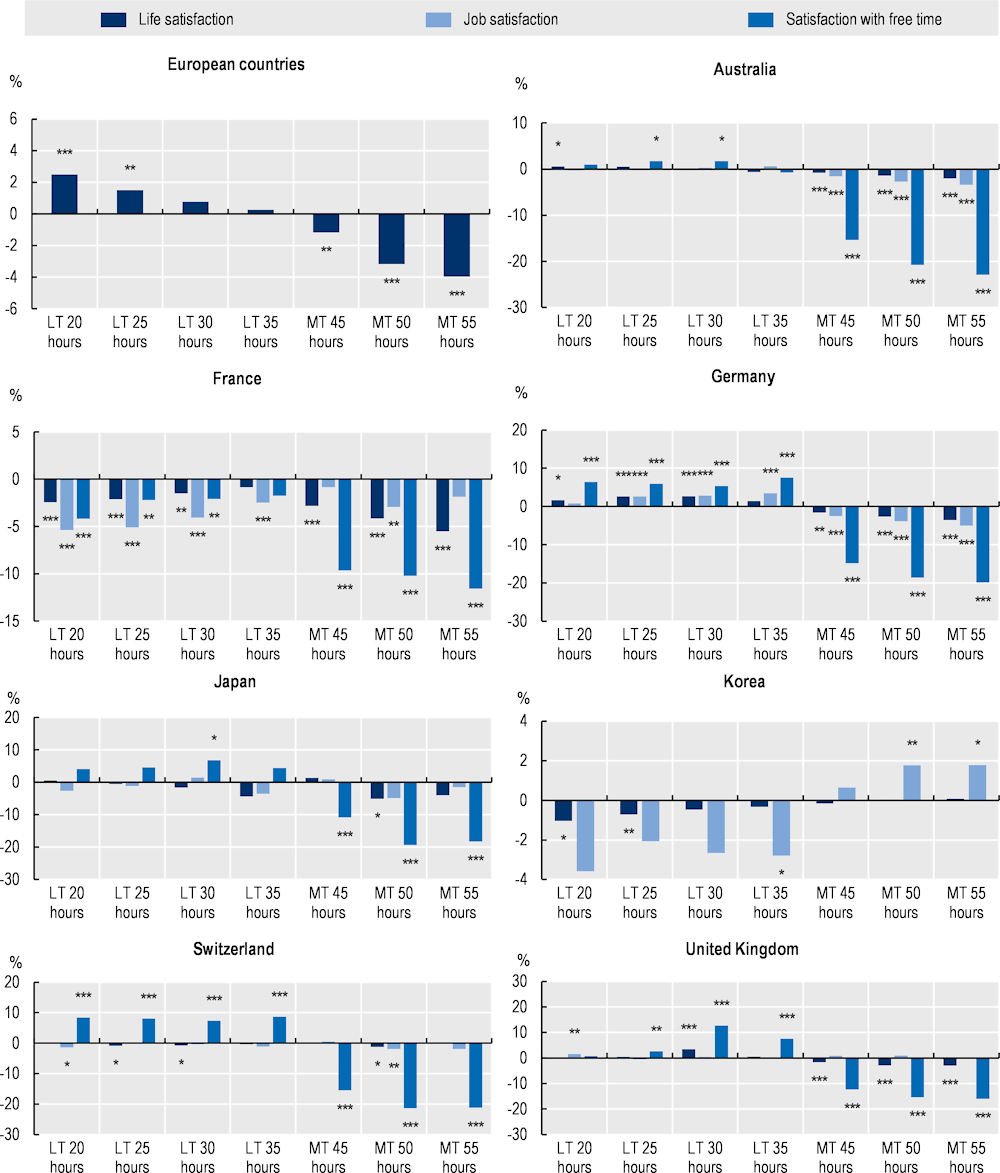

In terms of other non-material well-being outcomes, Figure 5.2 shows the marginal effect of working less than (or more than) particular thresholds on the likelihood of being satisfied with one’s life, job, and free time, the latter as a proxy for work-life balance (effects on different outcomes are tested separately). Results are more linear than for health outcomes, with long hours reducing the probability to be satisfied with all three outcomes (e.g. job, life or free time), and short hours increasing these probabilities in most countries. In particular, the probability to be satisfied with one’s free time is higher for those working less than 30 hours (in Australia and Japan) and less than 35 hours (in Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), while it is lower for those working more than 45 hours (Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). As for life‑and job satisfaction, relationships generally follow a similar pattern but the marginal effects of working shorter hours are generally smaller and less significant. France is again an outlier in that regard, since the marginal effects of working shorter hours show a reverse pattern: the probability to be satisfied with one’s job, life or free time is lower for those working less than 30 hours (and less than 35 for job satisfaction) compared to those working more than these thresholds.5 Another outlier is Korea, where people working shorter hours have a lower probability to be life‑satisfied, and those working long hours a higher probability to be job satisfied, which might again be due to cultural differences affecting subjective well-being survey items differently in different countries.

Note: Marginal effects (at the mean) are derived from individual probit regressions (i.e. regression of an individual’s actual hours worked, measured as a dummy variable capturing whether the individual is in a particular hours bracket, on this individual’s satisfaction outcome). Regressions are estimated using repeated cross-section data with robust standard errors and controlling for year fixed effects, demographic characteristics, household composition and income, job characteristics (including contract duration) and life events. Categories of actual hours worked shown in this chart refer to dummy variables defined using an increasing threshold of actual hours worked, from 20 hours to 55 hours. Life satisfaction, job satisfaction and satisfaction with free time are also coded as dummy variables; employees are considered satisfied if their answer to the satisfaction question is between 6 and 10 on a scale from 0 “not at all satisfied” to 10 “completely satisfied”. Satisfaction with free time refers to satisfaction with leisure for France. No data on satisfaction with free time for Korea and on job satisfaction and satisfaction with free time for the “European countries” (Panel A). For further details on definitions and regression specifications by country, see Annex 5.A. “European countries” (Panel A) refers to pooled data of 24 countries: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. ***, **, *: statistically significant at the 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. LT: Less than; MT: More than.

Reading example: In Australia, employees working more than 55 hours per week are expected to be 22.9% less likely satisfied by their free time compared to those working 55 hours or less per week.

Source: OECD estimates based on the European Social Survey (ESS, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for the European countries; the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA, 2005‑19) for Australia; the enquête Statistiques sur les ressources et conditions de vie (SRCV, 2010‑19) for France; the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for Germany; the Japan Household Panel Survey (KHPS/JHPS, 2010‑17) for Japan; the Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS, 2005‑19) for Korea; the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, 2004‑19) for Switzerland; and University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, Understanding Society: Waves 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for the United Kingdom.

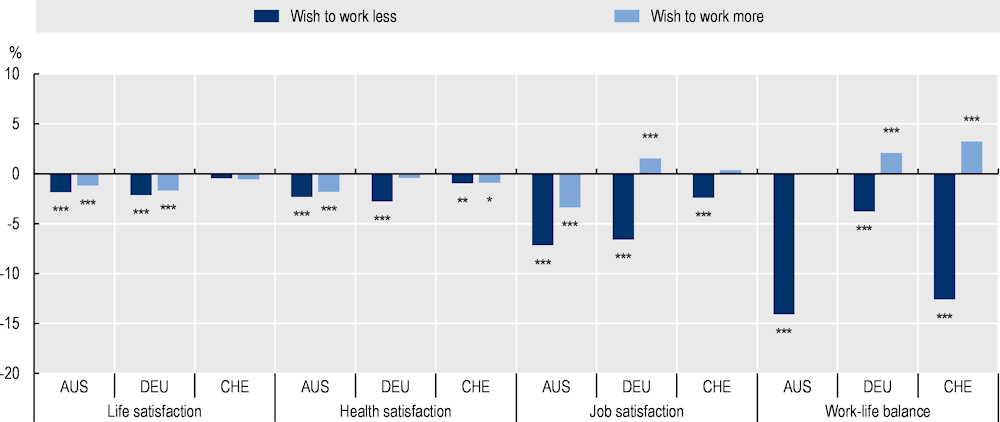

Finally and in line with the literature, OECD estimates available for Australia, Germany and Switzerland also reveal a significant negative relationship linking the mismatch between workers’ preferred working time and their actual working time on the one hand, and the selected measures of non-material well-being on the other hand. Interestingly, this negative relationship is mostly driven by those wanting to work less rather than more: evidence shows that the marginal effects of working more hours than one would like to (excessive hours) are negative for all non-material well-being outcomes, while the marginal effects of working less hours than one would like to (insufficient hours) are also negative but smaller for life and health satisfaction, and are positive for job satisfaction and work-life balance (Figure 5.3). While the data for Australia and Germany in this analysis are based on a precise survey question that asks respondents their preference while stating that their income would be unaffected, this precision is missing for Switzerland. This might bias estimations downward for Switzerland compared to Australia and Germany, if most workers assume that working less would come with a pay cut. The limits inherent to a fixed effects regression analysis also apply, which calls for caution in causally interpreting the results, as the analysis cannot address selection effects, e.g. the fact that workers with different life‑ and health satisfaction might select into jobs with different normal hours.

Note: Marginal effects (at the mean) are derived from individual probit regressions (i.e. regression of an individual’s hours mismatch on this individual’s satisfaction outcome). Regressions are estimated using repeated cross-section data with robust standard errors and controlling for year fixed effects, demographic characteristics, household composition and income, job characteristics (including contract duration) and life events. Hours mismatches are based on preferred weekly hours worked that employees wish to work taking into account that this change may affect their income. However, for Switzerland, the question asked does not explicitly take into account how income may be affected (“How many hours a week would you like to work as regards your main activity?”). Work-life balance refers to employees for which work as no or few impact on their family life. For Germany this indicator is based on satisfaction with housework. See Figure 5.1 and Figure 5.2 for a description of satisfaction outcomes shown in this Chart and Annex 5.A for further details on definitions and regression specifications by country. ***, **, *: statistically significant at the 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively.

Reading example: In Australia, employees wishing to work less than their usual hours are expected to be 1.8% less likely satisfied by their life compared to those wishing to work more or the same number of hours.

Source: OECD estimates based on the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA, 2005‑19) for Australia; the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for Germany; and the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, 2004‑19) for Switzerland.

In contrast, the literature generally6 points to positive effects on non-material well-being of working time arrangements that provide employee‑oriented flexibility, namely flexible hours (e.g. an arrangement whereby workers decide their starting and finishing times), teleworking and, to a lesser extent, part-time work – highlighting again the importance of workers’ control over their schedules as an important factor for their well-being. The underlying mechanism is twofold: on the one hand, flexible working time arrangements help reconcile work with private life and, in the case of flexible hours and teleworking, also coping with job demands and increasing autonomy. Teleworking additionally reduces commuting time. On the other hand, flexible working time arrangements may increase work intensity, (unpaid) overtime hours and work-life conflict (Tucker and Folkard, 2012[29]; Hurtado et al., 2015[30]; Tavares, 2017[31]; Charalampous et al., 2019[32]; Samek Lodovici et al., 2021[33]). Which of these mechanisms outweighs the other likely differs between groups of workers and work contexts, but some patterns emerge from the – mainly correlational – empirical evidence to date.

Overall, the non-material well-being effects of flexible hours, tend to be largely positive − see for example the review by Tucker and Folkard (2012[29]). Moen et al. (2011[34]) for instance find that the introduction of flexible working hours in an experimental setting in the United States improved workers’ health, because it enabled them to get more and better sleep, reduced the postponement of doctors’ appointments and increased the time workers spent on physical activity. Measures of life‑ and job satisfaction are also reportedly higher for workers with flexible hours in Europe and the United States (Atkinson and Hall, 2011[35]; Golden, Henly and Lambert, 2012[36]; De Menezes and Kelliher, 2017[37]; Angelici and Profeta, 2020[38]; Kröll and Nüesch, 2019[39]). At the same time, some studies report none or negative effects, mainly because they find that flexible hours are linked to increases in working hours, particularly for men (Lott and Chung, 2016[40]; Krug, Kemna and Hartosch, 2019[41]), and increases in work-life conflict, particularly for women (Kim et al., 2020[42]). Importantly however, such negative side effects may diminish when analysing flexible hours in connection with supporting policies such as parental leave (see for example, Wanger and Zapf (2021[43])).

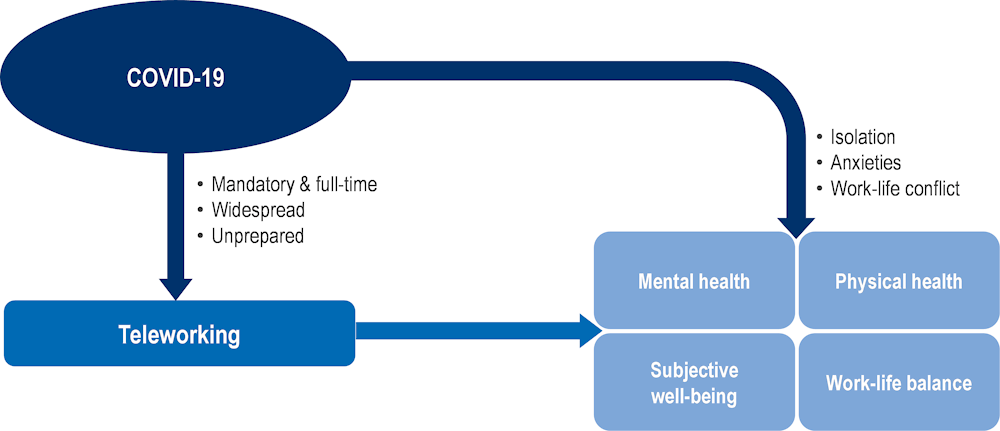

Contrary to flexible hours, the use of teleworking spread only recently because of COVID‑19‑induced lockdown measures in most OECD countries − for a detailed overview, see OECD (2021[1]) – but is often linked to flexible hours as a package deal. Since hybrid arrangements mixing teleworking and work in the office are likely to stay,7 research increasingly investigates the effects of teleworking on well-being during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Yet, drawing on resulting evidence would be ambivalent as a number of confounding factors are at play (see Box 5.1). Pre‑pandemic evidence suggests that the impact of teleworking on workers’ non-material well-being is generally positive but more mixed than for flexible hours − see for example the reviews by Tavares (2017[31]) and Charalampous et al. (2019[32]). Henke et al. (2016[44]) find for instance that teleworking improves a number of health outcomes in the United States, such as lower risks of obesity, alcohol abuse, physical inactivity, tobacco use and depression. Teleworking has also positive effects on work-life balance, but mainly if it is occasional and home‑based (instead of highly mobile) (Kim et al., 2020[42]; Rodríguez-Modroño and López-Igual, 2021[45]; Pabilonia and Vernon, 2022[46]). This is because the resulting regularity mitigates some of the negative consequences of teleworking on work-life balance through increased working hours and intensity – as found for instance by Felstead and Henseke (2017[47]) and Song and Gao (2020[48]). The beneficial effects of teleworking also appear to be at least partially mediated by workers’ attitude towards teleworking (Adamovic, 2022[49]) and perceived autonomy (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007[50]), which is found to decrease stress and buffer teleworking-induced increases in work intensification (Curzi, Pistoresi and Fabbri, 2020[51]). The moderating effect of autonomy on teleworkers’ non-material well-being should be contrasted with the risks of new supervision mechanisms, for instance in the form of surveillance software, being deployed to compensate for the lack of physical supervision, and their possible adverse effect on privacy, autonomy and ultimately well-being.

In terms of commuting time, Frazis (2020[52]) and Pabilonia and Vernon (2022[46]) estimate that teleworking saves workers in the United States an hour to 75 minutes per day of commuting and grooming time, which they instead spend on leisure. While objective health measures (e.g. diagnosed health problems) are barely affected by commuting, subjective health measures (e.g. self-perceived health satisfaction and status) are clearly higher for those commuting less, particularly for women and those commuting by car (Künn-Nelen, 2016[53]). Giménez-Nadal et al. (2019[54]) find that the saving in commuting time also improves life satisfaction, but with larger increase for men than for women, one potential reason being that the former use their saved time primarily on leisure, while women also increase their household production on a workday (but not over the entire work week) – at least according to time‑use data from the United States (Pabilonia and Vernon, 2022[46]). This is in line with findings from Arntz et al. (2019[55]) in Germany and Song and Gao (2020[48]) in the United States, who find positive and non-negative teleworking effects on life satisfaction only for men and women without children.

The outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic in spring 2020 led to a massive shift to teleworking, and an increasing number of studies make use of this exogenous shock to analyse the link between teleworking and workers’ well-being. Yet, COVID-induced restrictions significantly affected both the experience of teleworking and workers’ well-being, thus results from these studies cannot simply be extrapolated to post-pandemic teleworking arrangements. One important issue is that teleworking during COVID‑19 was a forced experiment. Yet, pre‑pandemic evidence suggests that teleworkers’ well-being is higher in occasional and voluntary arrangements (Rodríguez-Modroño and López-Igual, 2021[45]; Adamovic, 2022[49]). Moreover, COVID‑19‑induced teleworking was widespread, concerning also occupations for which it is feasible but suboptimal – see e.g. Eurofound (2021[56]) while the support of colleagues physically co-located in the office can be important to reap the well-being benefits of teleworking (Raghuram et al., 2019[57]), such support was often lacking during the pandemic. The full-time and widespread nature of teleworking during the pandemic also exacerbated risks of work-life conflict, as some had to telework in limited physical space, with insufficient technical equipment, and with other household members also teleworking or following distance schooling (DeFilippis et al., 2020[58]; Bertoni et al., 2021[59]). Finally, the shift to teleworking happened abruptly in many workplaces, without much consideration for health and safety requirements that would otherwise apply (ILO, 2020[60]). Because of this, workers also faced an unprecedented challenge in quickly adapting to teleworking, for example by learning new IT skills, which is a source of mental distress particularly for senior workers (Bertoni et al., 2021[59]).

Against this backdrop, a few studies have already attempted to isolate the effect of teleworking on worker’s well-being from that of other confounders, finding mixed and heterogeneous results for different groups of workers. Sasaki et al. (2020[61]) find positive effects of teleworking on workers’ psychological distress in Japan, but their cross-sectional data is very limited. Using email meta-data from over 3 million workers worldwide, DeFilippis et al. (2020[58]) find an increase in the average workday span, but their analysis is subject to aggregation bias and has unclear implications for workers’ well-being. This is in line with a recent online Eurofound survey (2021[56]), in which over one‑fifth of teleworkers reportedly worked during their free time every or every other day during the pandemic, but at the same time appreciated the absence of commuting to the office; spending more time with their children and spouses; and the flexibility of working hours. Using longitudinal European data, Bertoni et al. (2021[59]) find positive effects of teleworking on mental health only for men and women with no co-residing children.

While flexible hours and teleworking are compatible with full-time employment, part-time work by definition is not. In this respect, part-time jobs in most OECD countries tend to be associated with many labour market disadvantages including lower income, lower job security and reduced access to unemployment benefits, training and promotion (OECD, 2020[62]), which are important factors for job-quality and well-being (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[63]). On the one hand, the disadvantages associated with working part-time appear to be compensated by better health and work-life balance – see for instance the OECD Employment Outlook (2010[64]). On the other hand, part-time workers tend to work more unpaid overtime hours relative to full-time workers (Fernández-Kranz and Rodríguez-Planas, 2011[65]; Chung and van der Horst, 2020[66]), which may hamper some of the non-material well-being effects associated with part-time. More recent evidence confirms positive effects of part-time work on both objective and subjective health measures in the United States and the United Kingdom (Benson et al., 2017[67]; Cho, 2018[68]), and on workers’ satisfaction with work-life balance, but primarily in more gender egalitarian countries (Beham et al., 2019[69]) or where part-time work is more likely to be the norm (Nikolova and Graham, 2014[70]).8 Yet in practice, part-time work is not the norm in most OECD countries, where women make up the vast majority of part-time workers (OECD, 2021[1]) and experience negative impacts on their career progression as a result (OECD, 2018[71]).

Finally, a crucial factor ensuring positive well-being effects of flexible hours, teleworking and part-time work is that they are adopted voluntarily (Joyce et al., 2010[72]; Nikolova and Graham, 2014[70]; Pirani, 2015[73]; Bell and Blanchflower, 2019[74]; Adamovic, 2022[49]). Moreover, workers may have different reasons as to why they voluntarily take up flexible working time arrangements, which can impact well-being differently and be shaped by employers’ reasons to offer these arrangements in the first place. Scholars have pointed out for instance that flexible arrangements lead to more negative side effects like increased overtime hours if they are primarily offered to cut costs or incentivise workers to increase their performance (Chung and van der Horst, 2020[66]). Along these lines and beyond the firm level, promoting part-time work for instance is not only part of countries’ efforts to help workers reconcile work with private life, but also to reduce unemployment and increase labour market flexibility in low-paid occupations (Carrillo-Tudela, Launov and Robin, 2018[75]; Biewen, Fitzenberger and de Lazzer, 2018[76]; Barbieri et al., 2019[77]). Such and other forms of involuntary part-time work can be problematic, because they not only hamper well-being through the lower living standards resulting from income losses associated with part-time work (Bell and Blanchflower, 2019[74]), but also prevent any of the offsetting effects on health and work-life balance discussed above. Those who take‑up a part-time job but would prefer to work more are especially likely to experience negative well-being effects, as insufficient working hours negatively affects their material well-being as discussed in the previous section. Moreover and related to the gendered nature of part-time jobs, women tend to be more constrained in their adoption of flexible working time arrangements, having to opt most often for part-time work, while men tend to be able to use flexible working time arrangements with a greater degree of choice, and to opt most often for flexible hours (Wheatley, 2017[78]).

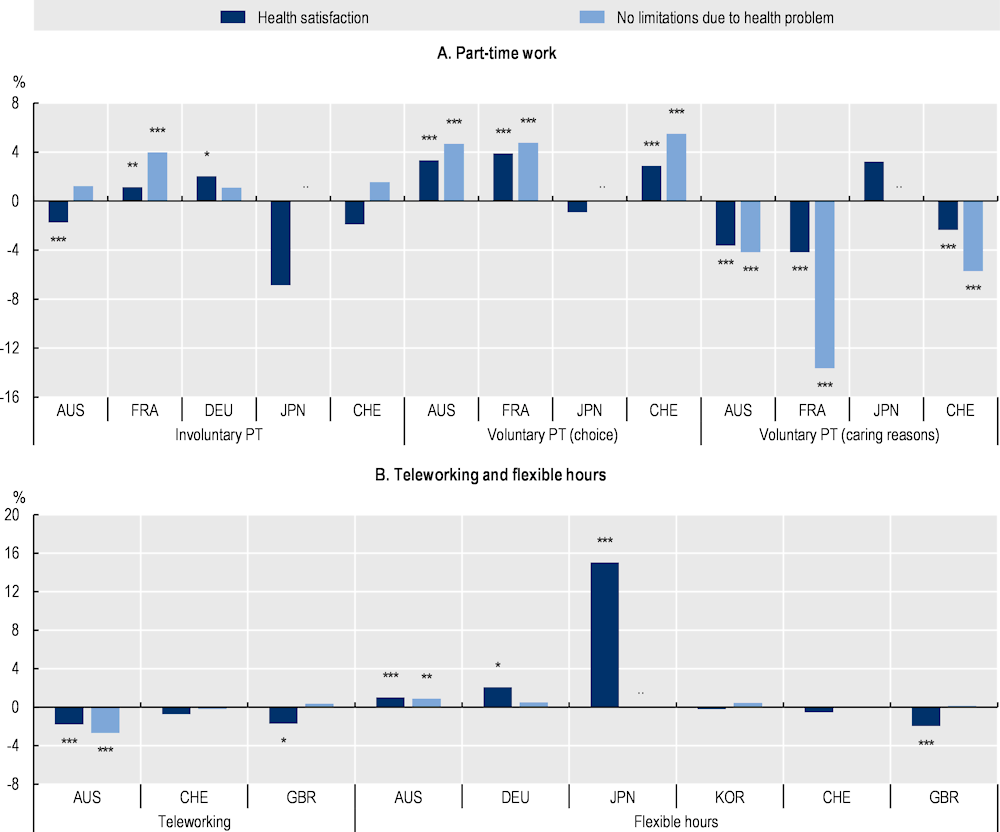

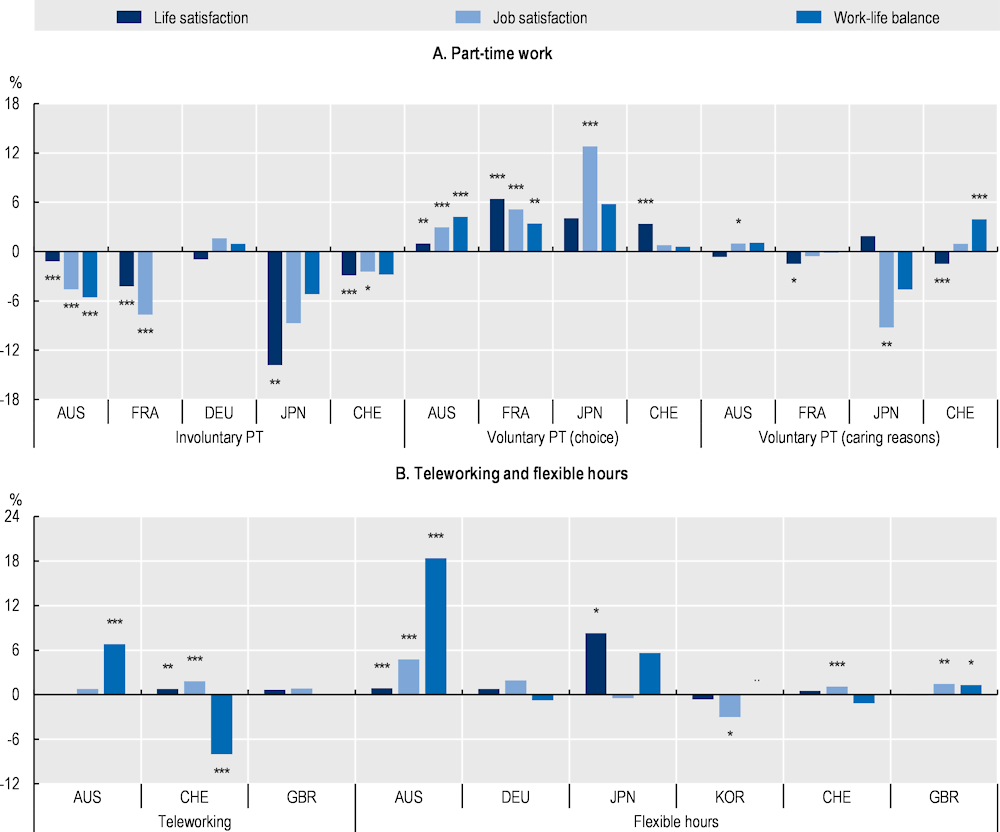

New OECD individual-level evidence presented here (Figure 5.5 and Figure 5.6) explores the relationship between three flexible working time arrangements that promote employee‑oriented flexibility (part-time, flexible hours and teleworking) and the same aspects of workers’ non-material well-being than above (e.g. health, work-life balance and job-and life satisfaction). As data are only available for three to seven OECD countries depending on the working arrangement considered (Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), caution is needed in generalising the results. Nonetheless, they point to interesting results. First, the results confirm the general patterns in the literature: out of the three working time arrangements considered, flexible hours are positively associated with all non-material well-being outcomes, namely self-assessed health, life and job satisfaction, and work-life balance (proxied by satisfaction with free time in Japan and the United Kingdom). Second, the relationship between teleworking and non-material well-being is more mixed, indicating a negative association with self-assessed health, small but positive associations with life‑ and job satisfaction and contrasting associations with work-life balance: while work-life balance is particularly high for teleworkers in Australia, it is particularly low in Switzerland. Finally, both voluntary and involuntary part-time work are negatively associated with all non-material well-being indicators. Interestingly though, distinguishing voluntary part-time workers into those who simply prefer it over full-time work and those who (have to) opt for it because of caring reasons reveals that the latter is associated with negative impacts on well-being, while truly voluntarily adopted part-time work is associated with high well-being. Such granular information is not (yet) available in many surveys and in any case not regarding teleworking and flexible hours, but points to a very important avenue of future research.

Note: Marginal effects (at the mean) are derived from individual probit regressions (i.e. regression of an individual’s flexible working time arrangements, on this individual’s self-assessed health outcome). Regressions are estimated using repeated cross-section data with robust standard errors and controlling for year fixed effects, demographic characteristics, household composition and income, job characteristics (including contract duration) and life events. “Involuntary PT” refers to part-time employees who could not find a full-time job; “Voluntary PT (choice)” refers to part-time employees who prefer part-time job or are not interested in full-time job; and “Voluntary PT (caring reasons)” refers to employees holding a part-time job due to own illness or disability, cares for children, disabled or elderly relatives or other personal or family responsibilities “Telework” refers to employees working any hours at home. “Flexitime” refers to employees who can decide, within certain limits, when to start and finish work each day. See Figure 5.1 for a description of the self-assessed health outcomes and Annex 5.A for further details on definitions of the flexible working time arrangements and regression specifications by country..: not available. ***, **, *: statistically significant at the 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. PT: part time.

Reading example: In Australia, involuntary part-time employees are expected to be 1.8% less likely satisfied by their health compared to full-time workers and other part-time workers.

Source: OECD estimates based on the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA, 2005‑19) for Australia; the enquête Statistiques sur les ressources et conditions de vie (SRCV, 2010‑19) for France; the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for Germany; the Japan Household Panel Survey (KHPS/JHPS, 2010‑17) for Japan; the Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS, 2005‑19) for Korea; the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, 2004‑19) for Switzerland; and University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, Understanding Society: Waves 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for the United Kingdom.

Note: Marginal effects (at the mean) are derived from individual probit regressions (i.e. regression of an individual’s flexible working time arrangements, on this individual’s self-assessed health outcome). Regressions are estimated using repeated cross-section data with robust standard errors and controlling for year fixed effects, demographic characteristics, household composition and income, job characteristics (including contract duration) and life events. Work-life balance refers to satisfaction with free time for Japan and the United Kingdom. No data on work-life balance for Korea. Figure 5.3 for a description of the well-being indicators (life satisfaction, job satisfaction and work-life balance) and Figure 5.5 for the working-time arrangement indicators (involuntary PT, voluntary PT by choice, voluntary PT for caring reasons, telework and flexitime) and Annex 5.A for further details on definitions of the flexible working time arrangements and regression specifications by country..: not available. ***, **, *: statistically significant at the 1%, 5% and 10%, respectively. PT: part time.

Reading example: In Australia, involuntary part-time employees are expected to be 1.2% less likely satisfied by their life compared to full-time workers and other part-time workers.

Source: OECD estimates based on the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA, 2005‑19) for Australia; the enquête Statistiques sur les ressources et conditions de vie (SRCV, 2010‑19) for France; the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for Germany; the Japan Household Panel Survey (KHPS/JHPS, 2010‑17) for Japan; the Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS, 2005‑19) for Korea; the Swiss Household Panel (SHP, 2004‑19) for Switzerland; and University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, Understanding Society: Waves 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018) for the United Kingdom.

Results from the literature and new OECD empirical evidence on working time and workers’ non-material well-being presented in the previous paragraphs suggest that some levers of working time policies exist that might enhance workers’ non-material well-being, such as policies regulating working hours (maximum and normal). While limits on maximum hours and overtime are already in place in most OECD countries to prevent their detrimental effect on workers’ health (OECD, 2021[1]), the regulation of normal weekly hours has less often been considered as a potential instrument to foster workers’ well-being. Yet, available evidence on the link between actual working hours and various non-material well-being outcomes presented above cautiously suggests that a reduction of normal weekly hours could enhance workers’ non-material well-being. Other options to improve workers’ non-material well-being discussed above include flexible hours, teleworking and part-time work. Yet, as shown in Figure 5.5 and Figure 5.6, part-time, even when voluntary, might be associated with negative well-being outcomes, in cases where it is chosen for caring reasons – which is likely to be the case for a large proportion of female workers in particular. In addition, the already existing extensive research on part-time work also suggests that even voluntary forms have limited potential for increasing workers’ non-material, let alone material well-being. By contrast, results in Figure 5.5 and Figure 5.6 suggest that flexible hours might be a more promising means of improving workers’ non-material well-being – and one that has been less researched so far.

Beyond assessing their impact on non-material well-being, the effect of these policy options on employment and productivity should also be evaluated, since these two outcomes have ripple effects on workers’ material well-being. A crucial element to consider in this analysis is the extent to which a reduction in normal working hours would maintain the same monthly/weekly income for workers, thus inducing an increase of hourly pay and potentially on labour cost if increases in hourly productivity do not offset increases in pay. Effects on employment levels should also be carefully assessed.

The remainder of this chapter sets out to investigate the effect of normal hour reductions and flexible hours on employment and productivity. While the effect of teleworking on non-material well-being outcomes is less clear-cut, its effect on employment and productivity are also evaluated, on account of its increased prevalence and relevance in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis – and since teleworking and flexible hours often come as a package deal.

In order to carefully discuss the feasibility of the policies identified above as potentially well-being enhancing, this section starts by presenting comprehensive literature reviews on the employment and productivity effects of changes in normal hours. This assessment of the literature is complemented by new evidence analysing the effects of national legislative reforms reducing normal hours in European Union countries and of firm-level episodes of contractual hours reductions in Germany, Korea and Portugal. This two‑pronged empirical approach helps understanding the effect of concrete episodes of hours reductions implemented in different ways. Finally, the section reviews the literature on the employment and productivity effects of flexible hours and teleworking (the latter, as explained above, on account of its increase prevalence in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 crisis), and presents new evidence on the productivity and employment effect of flexible hours in German firms.

This section presents a summary of the most salient theoretical arguments and of the most robust empirical findings – a more comprehensive literature review is available in Annex Table 5.C.1. Theoretical predictions on the effect of reducing normal hours on employment depend on the underlying mechanisms and assumptions at play on the labour demand side. In this respect, two factors are of particular importance: whether the reduction of hours takes place at constant monthly (or annual) pay – which would lead to a rise in hourly labour cost, and could have adverse effect on employment − or not, and whether hourly productivity gains may be generated and mitigate this potential detrimental employment effect.

Theoretical papers for instance generally assume that working time reductions take place at constant monthly (or annual wage).9 Under this assumption, a reduction of normal hours has an ambiguous effect on employment.10 Simplified versions of the main arguments are as follows (see e.g. Kapteyn et al. (2004[79]) for a more thorough review). Following a simple logic, one could assume that in firms not usually resorting to overtime (i.e. firms where the pre‑reform normal working time was equivalent to the optimal working time), reducing normal hours could incentivise firms to hire more workers in order to meet orders, thus leading to a positive effect on employment. Yet, this logic11 assumes that the optimal working time remains the same after the change, and that hours and workers are substitutable (notably ignoring the fixed costs associated with each additional worker). In firms already using overtime before the reduction in normal hours, the marginal cost of hiring an additional worker goes up after the change (since a larger proportion of her time now has to be paid the overtime premium), while the marginal cost of an additional hour is left unchanged: to compensate for the reduction in normal hours these firms might then choose to pay for more overtime rather than hiring new workers, leading thus to a negative effect on employment (Cahuc et al., 2014[80]; Calmfors and Hoel, 1988[81]).12 More generally, the increase in the hourly labour cost following a normal hours reduction could lead firms to substitute capital for labour, leading to a reduction in employment. However, higher hourly pay could be compensated by gains in hourly productivity induced by the reduction in hours – for instance through productivity-enhancing organisational changes, higher investment, the recruitment of more productive workers, or through labour supply responses (more rested workers could have a higher hourly productivity). Gains in hourly productivity would at the same time limit the negative effect on employment, but also suppress the incentives to hire more workers, therefore preserving employment.

Turning to empirical results, purely correlational studies (i.e. studies that do not account for any possible endogeneity, and that focus on measuring the statistical significance of covariations13) tend to yield mixed results, ranging from studies finding a negative impact of hours reduction on employment (Steiner, Peters and Steiner, 2000[82]; Sagyndykova and Oaxaca, 2019[83]), to the majority of correlational studies finding non-significant effects (Andrews, Schank and Simmons, 2005[84]; Hunt, 1999[85]; Trejo et al., 2016[86]; Kramarz et al., 2008[87]; Brown and Hamermesh, 2019[88]),14 to those finding a positive effect (Fiole, Roger and Rouilleault, 2002[89]; Husson, 2002[90]; Kapteyn, Kalwij and Zaidi, 2004[79]). Among authors using a quasi-causal research design (which, by contrast to purely correlational ones, aim to account for some forms of endogeneity, although they do not correct for all of it), Crépon and Kramarz (2002[91]) find a negative effect of the 1996 statutory reduction of working time from 40 to 39 hours in France on employment. Raposo and van Ours (2010[92]) find that the reduction of working hours in Portugal decreased the separation rate of workers affected by the working time reduction. Crépon et al. (2004[93]) find that employment increased in firms reducing their hours in France (they argue that at least part of this increase is likely to be driven by a concomitant reduction in social security contributions and to wage restraint, rather than by the hours reduction – although on this issue, the meta‑analysis by Gubian et al. (2004[94]) attributes a larger positive effect to the reduction itself). Finally, a majority of quasi-causal studies finds non-significant results – see e.g. (Estevão and Sá, 2006[95]; Costa, 2000[96]; Skuterud, 2007[97]; Sánchez, 2013[98]; Chemin and Wasmer, 2009[99]; Kawaguchi, Naito and Yokoyama, 2017[100]).

Of course, different studies are based on the analysis of different reforms and/or contexts. Hence, differences in results might be due to differences in the parameters of the reforms analysed, such as their size and starting point, and their implementation. Similarly, non-significant results in country-specific analyses could stem from heterogeneous effects in the pool of firms observed. Hence, while the review of existing literature presented above suggests that in most cases, there were no significant effect on employment, it does imply that a reduction of normal hours should not be considered without paying careful attention to its design and implementation.

As explained above, the theoretical prediction that reducing normal hours might have adverse effects on employment rests on two assumptions: first, that monthly (or annual) wages are kept constant; second, that hourly productivity does not increase sufficiently to keep unit labour cost approximately constant. The non-significant results observed in many empirical papers could be explained by the fact that either of these assumptions does not hold in practice.15 Regarding the first assumption, two of the papers reviewed in Annex Table 5.C.1 that use a quasi-causal research design and consider wages as an outcome indeed find evidence of wage cuts or wage restraint (meaning that wage growth was slowed down): Sanchez (2013[98]) in the case of Chile, and Crépon, Leclair and Roux (2004[93]) in the case of France. However, all other papers find that reducing working hours increased hourly wages, but without negatively affecting employment (Estevão and Sá, 2006[95]; Raposo and van Ours, 2010[92]; Kawaguchi, Naito and Yokoyama, 2017[100]). One possible explanation for the results of this second group of papers is that the second assumption does not actually hold and that hourly productivity may have increased sufficiently to maintain unit labour cost approximately constant. This possibility is considered in the literature review on productivity effects below (Sections 5.2.2 and 5.2.3 then present new evidence on this issue).

Another potential explanation for studies finding no negative effect on employment despite an increase in hourly labour cost is that the hours reduction takes place in a context where wages have not fully adjusted to past productivity growth: in that situation, firms can absorb higher labour costs while preserving employment thanks to their accumulated rent. Such rents can typically exist in monopsonistic labour markets. In these contexts, characterised by an asymmetry in market power between employers and workers leading to an inefficient allocation of working time, or a suboptimal wage growth, a reduction in hours inducing a rise in hourly wage can in fact have a similar impact as a minimum wage increase in standard monopsony models, e.g. counteract excessive employers’ market power without creating additional unemployment – see e.g. Manning (2020[101]) and Chapter 3. The possibility that working hours reduction might preserve employment in monopsonistic labour markets is in fact acknowledged and discussed in the literature16.

Compared with employment, the link between working hours and productivity remains understudied in the empirical literature. From a theoretical point of view, reducing normal hours could result in an increase in hourly productivity per worker, sustaining total productivity per worker17 through at least two channels. First, reducing working hours could reduce workers’ fatigue and increase their work engagement, hence resulting in an increase in hourly productivity. Second, reducing working hours could prompt firms to rethink their production processes and implement productivity-enhancing investments as well as organisational and managerial innovations – including potentially through replacing less productive workers with more productive ones to compensate for reduced hours. Beyond these two channels, productivity could also be enhanced at a more aggregate level if the time freed from work helps spark innovation and new firms creation (Gomes, 2021[102]).

However, the limited number of existing studies on working hours and productivity focuses almost exclusively on the potential productivity effect of reducing workers’ fatigue through regulation on maximum hours and overtime. On the latter, the evidence in the literature is rather unanimous:18 productivity decreases with long hours. The evidence on the productivity effect of reducing normal hours is scarcer.19 Delmez and Vandenberghe (2017[103])’s analysis on total hours (which therefore linearly averages effects of normal hours and overtime) shows clear evidence of a declining productivity of hours in Belgian firms (with a 1% increase in firm-level hours leading to a 0.8% increase in firm-level value added). Crépon et al. (2004[93]), however, observe a slight decrease in total factor productivity following the reduction in normal hours from 39 to 35 hours in France in the early 2000s. By contrast, Park and Park (2019[104]) exploit the stepwise reduction in normal hours from 44 to 40 hours between 2004 and 2011 in Korean manufacturing firms, and find that it even increased total output per worker (i.e. not only hourly productivity). Evidence of decreasing marginal returns to normal working hours has been found in cross-country (Cette, Chang and Konte, 2011[105]) as well as micro-level analyses (Collewet and Sauermann, 2017[106]). This last study, based on an experiment – and therefore with particularly robust results – with Dutch call-centre workers in the 2010s, is particularly enlightening. Indeed, it exploits variation in the effective working time (i.e. excluding breaks, slack or training hours) due to random changes in weekly schedules, of workers paid by the hour and employed on average for 6 hours per day, 4 days a week (and effectively working 17.7 hours per week). Using these precise data, Collewet and Sauermann find strong evidence of a fatigue effect, with hourly productivity decreasing with hours, even for workers in intensive part-time jobs.

All of the above suggests that there could be some potential for working time policy to be productivity-enhancing over and above reducing long hours and overtime and also focusing on the reduction in normal working hours. Quests for the “optimal” length of the workday are therefore not over, and answers are likely to vary with job characteristics (Pencavel, 2016[107]; Dolton, Howorth and Abouaziza, 2016[108]).

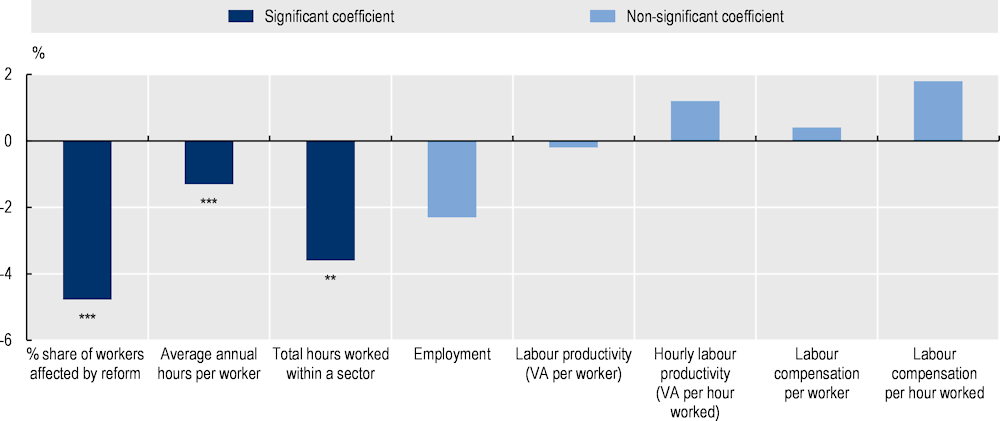

As outlined above (and see also Annex Table 5.C.1), much of the empirical literature on the impact of working time reforms, and in particular on working time reduction, concentrates on the employment effect. When productivity effects are considered, this is often done in isolation from employment effects, so that the broader economic impact of working time reforms (and the potential interaction between employment and productivity effects) remains poorly understood. To overcome these limitations, this section draws on results from Batut, Garnero and Tondini (2022[109]) to consider the employment and productivity effect of several working time reforms that took place in Europe between 1995 and 2007 allowing for general equilibrium effects.

The analysis focuses on national working time reductions reforms that were implemented in five European OECD countries; while these reforms kept monthly wages constant, thus leading to higher hourly wages, they did not all include compensatory measures for firms to buffer the impact on labour cost (see Table 5.1 for an overview of the reforms). By lumping several reforms together in a relatively short time period, in countries with a similar legislative framework (the EU Working Time Directive) and relatively similar societal preferences, this analysis allows presenting average effects and minimise the idiosyncrasies linked to specific national reforms. The causal effect of working time reductions on the outcomes of interest (hours worked, employment, hourly wage and hourly productivity) is identified via a difference‑in-difference approach that exploits the initial differences in the share of workers exposed to the reforms across sectors.20 The treatment group is composed of sectors in reforming countries above the median of the share of affected workers before the reform, i.e. those previously working more hours than the new threshold specified in the reform (see Box 5.2 for a discussion of the specification). The analysis uses information from multiple sources to document working time reforms in European Union countries.21 It relies on sectoral data in 22 countries for hours worked, employment, wages and productivity from EU KLEMS, since they are among the most reliable cross-country comparable sources for industry-level data. Out of 22 countries, 17 serve as full control.

Results are presented in Figure 5.7 for a discrete treatment variable (as in Equation 5.1 in Box 5.2) and for both a discrete and a continuous measures of exposure (Panel A and Panel B in Annex 5.A, as defined in Equation 5.1 and Equation 5.2 in Box 5.2). They show that the reforms examined appear to reduce significantly the share of workers who were working more than the new threshold introduced by the reform (by around 5 percentage points with the specification with the discrete treatment variable i.e. a reduction of one‑third compared to the pre‑reform difference between more and less exposed sectors) and the yearly number of hours worked on average by workers (by 1.3%, relative to sectors below the median, with the discrete treatment variable i.e. a reduction of two‑thirds compared to the pre‑reform difference22). However, reforms had no significant effects on employment, on workers’ compensation nor on hourly productivity (Figure 5.7). Although insignificant, the evidence displayed on employment reduction suggests that effects varied a lot across industries, reflecting perhaps different degrees of monopsonistic labour market situations; so overall, the absence of significant effect for employment is likely to be the average of heterogeneous positive and negative effects.

Results do not vary when the estimation is run only on the sample of countries implementing a reform (i.e. Belgium, France, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia, thus exploiting sectoral differences in the exposition to reforms in these countries only) and are robust to extended checks of alternative specifications, samples and estimators.23

|

Country |

Year |

Implementation |

Reduction of weekly working time |

Monthly wage |

Compensations for firms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Portugal |

1996 |

1997‑98 |

44h -> 40h |

Constant |

None |

|

Italy |

1997 |

1998 |

48h->40h |

No specific adjustment. |

None |

|

France |

1998 |

2000 |

39h->35h |

Constant |

Reduction in Social Security contributions |

|

Belgium |

2001 |

2002 |

40h->38h |

Constant |

Reduction in Social Security contributions |

|

Slovenia |

2002 |

2003 |

42‑>40h |

Constant |

None |

Note: Adoption refers to the year of adoption of the legislation, while implementation refers to the year in which the legislation was actually implemented.

In 1997 and 2002, Poland also reduced weekly working time but the LFS data for Poland do not cover these years and therefore these reforms are not part of the analysis in this section.

Source: Batut C., Garnero A., and Tondini A. (2022[109]) “The Employment Effects of Working Time Reductions: Sector-Level Evidence from European Reforms”, FBK-IRVAPP Working Papers Series.

Batut, Garnero and Tondini (2022[109]) estimate the effect of reductions in working hours on value‑added per hour worked, employment and wages, using the following specification:

where stands for the dependent variable (e.g. productivity, employment, etc.), is a vector of sector and time‑varying controls at the country level (share of self-employed, gender, part-time, temporary contract, occupation, education and age), and are fixed effects (respectively sector × country, sector × year and country × year fixed effects), is the error term, indexes the sector, the country and is the year. is a binary variable indicating whether a sector is above the median of the share of affected workers before the reform (e.g. those working more hours than the threshold specified by the reform) interacted with which indicates the staggered implementation of the reform across countries. The coefficient of interest, , is identified by the evolution of more affected sectors relative to less-affected sectors in reforming countries at the moment of the reform.

There are two important caveats to point out about the β coefficient: first, it is identified only through variation within reforming countries, hence non-reforming countries play a role only in the estimation of the set of sector × year fixed effects; second, it only identifies a relative effect, i.e. the effect of more treated sectors relative to less treated sectors.

Moreover, a second specification is tested that introduces a continuous measure of sectoral exposure to the reform (and not a discrete one as in Equation 5.1. This also allows to recover a relative effect, leveraging the full variation in exposure to the reform, at the price of assuming a linear relation between the effect and the measure of exposure. Equation 5.1 is rewritten as follows:

where exposure indicates the share of workers above the reform level in each sector.

Source: Batut, Garnero and Tondini (2022[109]), “The Employment effects of Working Time Reductions in Europe”, FBK-IRVAPP Working Papers Series.

Several potential explanations could be behind these results, echoing the theoretical arguments discussed in Section 5.2.1. First, between 1995 and 2007, all European countries (with the exception of Italy) experienced relatively robust growth, together with productivity and wage growth (although with a lot of heterogeneity across sectors/countries) and stable, low inflation. It is therefore possible that, even in the context of a standard competitive model, the reduction of working time and the increase in labour cost per hour worked might have been quickly absorbed with no effect on employment (in line with the observed results of insignificant but positive effect on productivity). Second, an alternative partial explanation would be that the classical hypotheses do not hold, and the reductions in working time with constant monthly wage act like an increase in the minimum wage in a monopsony model (e.g. the increase in hourly labour cost induced by the reduction in hours counteracts pre‑existing excessive employers’ market power as described in Section 5.2.1). A third potential explanation could be that some mechanisms limited the rise of labour costs in practice, such as a decrease in social security contributions (as in the French and the Belgian reforms24) or some voluntary wage restraint by social partners in wage negotiations. Finally, as outlined before, even if statistically insignificant, the average estimated employment effect is negative and not small: employment is estimated to have decreased by 2.3% in more exposed industries with respect to less exposed industries. These results suggests that the average estimated effect could result from the aggregation of heterogeneous positive and negative effects in different industries and local labour markets, for example because certain local labour markets are more monopsonistic while others are more competitive (see Chapter 3).

Note: This Chart shows estimates based on Equation 5.1 presented in Box 5.2 (i.e. discrete treatment variable) with standard errors clustered at the country × sector level and including controls at sector level (2‑digits NACE Rev.1.1. from an ad hoc extraction by EUROSTAT) by age, education, gender, type of contracts, tenure and occupation. Share of workers affected by reform indicates the share of workers working more than the value specified by the existing legislation (for countries without a reform) or introduced by the reform (for countries with reform). Sectors are weighted by the within – country share of employment in the pre‑reform period.

Source: Batut, Garnero and Tondini (2022[109]), “The Employment Effects of Working Time Reductions: Sector-Level Evidence from European Reforms”, FBK-IRVAPP Working Papers Series.