This chapter provides an overview of the Ukrainian refugee crisis and the policy responses in OECD countries. Discussing the scale and nature of migration flows triggered by the unprovoked war of aggression of Russia against Ukraine, it covers information on migration permits and rights granted to Ukrainians. The chapter then examines both initial and medium-to-longer term reception support that is available to Ukrainian refugees, focusing specifically on housing, access to immediate assistance and public services, education, and employment. As countries are beginning to transition towards integration efforts, new challenges are emerging. These are explored in the last section of the chapter.

International Migration Outlook 2022

4. Responding to the Ukrainian refugee crisis

Abstract

In Brief

Russia’s unjustifiable, unprovoked, and illegal war of aggression against Ukraine has generated a historic mass outflow of people fleeing the war. By mid-September 2022, close to 5 million individual refugees from Ukraine had been recorded across the EU and other OECD countries, out of whom about 4 million had registered for temporary protection or similar national protection schemes in Europe.

OECD countries in Europe and beyond responded swiftly to the refugee crisis, granting immigration concessions to Ukrainian nationals, such as visa exemptions, extended stays or prioritisation of immigration applications.

The Council of the European Union enacted, for the first time, the Temporary Protection Directive 2001/55/EC (TPD), which provides a set of harmonised rights for the beneficiaries in all EU Member States.

Non-EU OECD countries also responded swiftly to the Ukraine crisis and took, to varying degrees, measures to facilitate the entry and stay of Ukrainian people fleeing the war. In some cases, non-EU countries use existing pathways to admit Ukrainians. Other countries, however, have established new Ukraine‑specific schemes and policies, including Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. The scope of these policies is often limited to Ukrainian citizens and their immediate family members with preference given to people with existing connections to the host country.

OECD countries extended different types of support and assistance to new arrivals to mitigate the risk of social and economic exclusion of refugees and to assist them in meeting basic needs. These measures generally include providing emergency shelter, financial subsidies and cash benefits, as well as ensuring access to education and health services. The extent of different formal reception measures in countries often depends on the type of permit granted.

Although there is a widespread expectation that Ukrainians fleeing the war will return after its end, countries are increasingly extending access to different integration measures.

Ensuring access to housing has been a major challenge in many receiving countries. The rapid influx of Ukrainian refugees to Europe happened in the context of significant pre‑existing housing challenges, such as insufficient housing supply and rising costs. This is limiting available options for housing refugees both in the short and medium-to-long term in many host countries, including Poland.

Access to public education for minor children is available in all OECD and EU countries, yet in the first months of the crisis, many students continued to follow a Ukrainian curriculum online. Most countries are now looking to integrate students fully into national systems and have made efforts to scale up their classroom and teaching capacities to facilitate this, including by hiring Ukrainian teachers.

Outside compulsory education, providing VET to Ukrainian refugees is often seen as a particularly promising pathway with high expected returns, which is why many countries have taken special measures to facilitate access to both upper secondary and adult vocational training.

While immediate access to higher education is not common, most countries have introduced some support measures to help Ukrainian refugees with this. These include host language training, academic guidance, financial assistance and grants, and reserved study places. Moreover, many higher education institutions in OECD countries have implemented their own exceptional measures to support Ukrainian students and scholars.

Some of the characteristics of Ukrainian refugees, especially their educational profile, are likely to improve their labour market integration prospects and employability compared to other refugees, while others, namely that most arrivals are women with children, may hinder them.

Ukrainian refugees have been granted the right to work in most host countries. Despite this, they have been relatively slow to enter the labour force, though the number of people wanting to do so is expected to rise.

Many OECD countries offer help with finding a job, although the degree and nature of the support provided varies significantly. Focus has been on facilitating successful matching: many online portals have been launched or are in development with varying degrees of in-built matching systems to connect Ukrainian refugees to companies and suitable jobs.

The transition to medium- and longer-term solutions has exposed emerging challenges, including moving away from temporary and other similar subsidiary statuses towards permanent statuses, mainstreaming support measures, addressing secondary flows and preparing for changes in public opinion and support.

Introduction

The large‑scale unprovoked aggression of Russia against Ukraine that started on 24 February 2022 has created a massive refugee1 crisis unseen in Europe since World War II. While it took two years to reach 3 million Syrian refugees, this number was hit in less than three weeks in the case of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. By mid-September 2022, close to 5 million individual refugees from Ukraine had been recorded across the EU and other OECD countries, out of whom about 4 million had registered for temporary protection or similar national protection schemes in Europe. OECD countries in Europe and beyond responded swiftly to the new situation, opening their doors and extending support to new arrivals. The duration of inflows, however, remains unknown and countries are only beginning to grasp and address longer-term challenges related to this massive influx.

Many OECD countries have faced displacement crises over the last decade, notably in 2014‑17 in Europe and in the context of the Venezuelan migration and refugee crisis in South America. The Ukrainian refugee crisis, however, has many unique characteristics. First, pre‑existing visa facilitations for Ukrainian nationals in Europe greatly promoted orderly cross-border movements. Second, compared to other refugee flows, the profile of arrivals is atypical: it is highly skewed, as mostly women with children are leaving the country, and a higher share of arrivals are tertiary educated. Third, there is a widespread expectation that Ukrainians fleeing the war will return after its end. And finally, in many respects, the response in receiving countries has also been unique. The crisis has attracted unprecedented political and public support from host populations, and there has been an exceptional mobilisation of institutions and host communities.

The policy responses built on lessons from previous experiences with large‑scale refugee inflows. In addition to ensuring the immediate needs of new arrivals are met (e.g. temporary shelter and subsistence), most governments have introduced further measures. Such measures include financial subsidies (e.g. cash benefits), free services (e.g. transport), and facilitating access to education, health services and employment. The extent of such measures, however, has varied between countries and depended on the type of permit granted. As the war drags on and the task of rebuilding Ukraine is still ahead, countries are recognising that a quick return of displaced persons is unlikely and are transitioning from providing short-term immediate support to medium- and long-term responses. Such transitions towards more durable solutions have been particularly pressing in the case of housing, where reception capacities in many countries and regions are severely challenged. Yet the need to adapt and revise approaches goes beyond that. As people stay for longer, the availability of meaningful learning and career opportunities becomes critical, as does general integration support.

In the context of this transition, a number of new challenges are also emerging. The majority of Ukrainian refugees in OECD countries have temporary and subsidiary statuses, which may raise issues in the event of protracted war and displacement. As many exceptional measures introduced in the outbreak of the refugee crisis have sunset clauses, countries need to devise ways for providing sufficient support to Ukrainian refugees through mainstream measures without overburdening general social security systems. At the same time, the questions about possible implications of secondary movements to other countries and changes in public opinion and support are also becoming key policy considerations.

This chapter gives an overview of the nature and scope of the refugee crisis and the policy responses in OECD countries. It covers information on associated migration flows, permits and rights granted to Ukrainians as well as immediate and medium-to-longer term support available to the new arrivals, including measures related to housing, education, and employment. Finally, the main challenges ahead are discussed.

Migration flows triggered by the Russian large‑scale invasion of Ukraine

Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine generated a historic mass flight. Daily outflows from Ukraine increased rapidly during the first days of the war, peaking at over 200 000 border crossings on 6 March 2022. The numbers have, however, declined progressively since then and net migration from Ukraine is currently zero or even slightly negative as the number of returns to Ukraine increased. By mid-September 2022, close to 5 million individual refugees from Ukraine had been recorded across the EU and other OECD countries, out of whom about 4 million had registered for temporary protection or similar national protection schemes in Europe.

The majority of people fleeing Ukraine went to Poland, which has recorded more than 6 million border crossings from the country since February. During this period, 1.3 million people also entered Hungary, 1.2 million Romania, followed by the Slovak Republic (780 000) and Moldova (600 000). Many Ukrainian refugees continued to travel towards other destination countries and cross-border travel remains substantial in both directions. Consequently, despite the large number of border crossings, there are only about 29 000 refugees in Hungary and 86 000 in Romania.

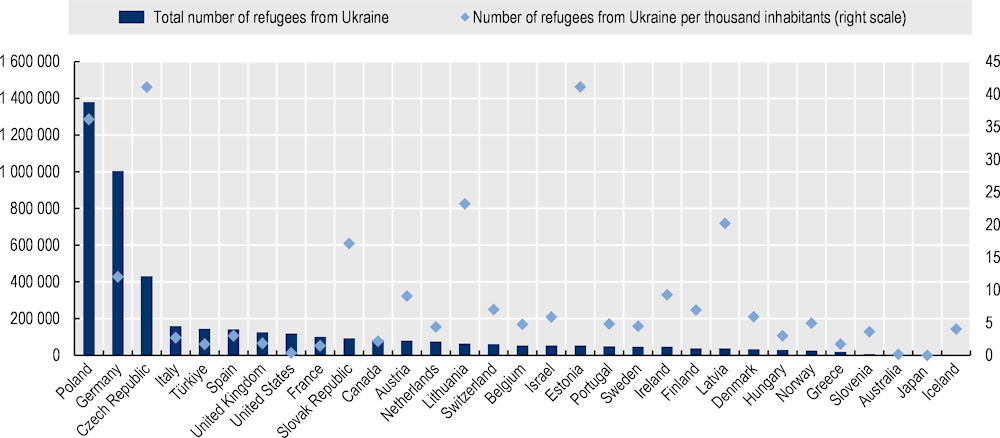

As of mid-September 2022, Poland is the main receiving country in absolute numbers with 1.38 million refugees from Ukraine recorded for temporary protection in the country (Figure 4.1). Poland is followed by Germany with about 1 million and the Czech Republic with more than 400 000 refugees.

Outside the EU, more than 550 000 Ukrainian nationals and family members have applied through the Canada-Ukraine authorisation for emergency travel (CUAET) for a temporary resident visa to travel to and stay in Canada. Almost 240 000 have been approved and more than 82 000 people have arrived in the country. In the United States, since 25 April, 124 000 people have applied to financially sponsor Ukrainian refugees through a private sponsorship programme (United for Ukraine) and almost 51 000 Ukrainians have arrived through this initiative. Tens of thousands of additional Ukrainians obtained a non-immigrant or an immigrant visa or were admitted along the Mexico US border. In the United Kingdom, total arrivals of Ukrainians through the Ukraine sponsorship scheme or the Ukraine family scheme has now reached 126 000.

Figure 4.1. Number of refugees from Ukraine recorded in OECD countries, absolute numbers and per thousand of total population, mid-September 2022

As a percentage of total population, across OECD countries, the main receiving countries are Estonia and the Czech Republic with more than 40 refugees per thousand inhabitants. They are followed by Poland (36 ⁰⁄₀₀), Lithuania (23 ⁰⁄₀₀) and Latvia (20 ⁰⁄₀₀) (Figure 4.1).

The general mobilisation in Ukraine prevents most men aged 18 to 60 from leaving the country. As a result, mostly women with children, some elderly people but very few working age men have left the country so far. As a result, in virtually all host countries, at least 70% of the adults are women and over a third of all refugees are children. Shares of both groups are larger in countries geographically closer to Ukraine. In Poland, for instance, children account for over 40% of refugees and about 87% of all adults are female. Similarly, in Lithuania, about 36% of all Ukrainian refugees are minor children and 83% of the adults are women. In Spain, 33% of the arrivals have been minors and 70% women, while in Italy the figures are respectively 30% and 75%.

The limited information currently available on the level of education of Ukrainian refugees suggests not only that a higher share of them are tertiary educated than among other refugee groups, but that they are also more highly educated than the general Ukrainian active population (among which 34% were tertiary educated in 2019). The exact figures, however, vary across countries. According to administrative data from Spain, 62% of Ukrainian adults have a tertiary degree, 28% upper secondary or a professional qualification, 9% a secondary degree, while around 1% have no more than primary education. Two non-representative studies from Germany found even higher educational levels among the refugee population in the country: less than 2% of the respondents were low-educated, while the share of tertiary-educated exceeded 73% (INFO GmbH, 2022[1]; Panchenko, 2022[2]).

In the same vein, data collected by the European Union Agency for Asylum (EUAA) and the OECD across several EU countries found that 71% of respondents overall had a completed tertiary degree with 41% holding a master’s degree or higher. A further 11% have completed professional (vocational) education. There are, however, some differences in qualification levels of respondents by their region of origin, with Ukrainians fleeing from Kyiv City having a higher education level than other groups.

Immigration permits and rights granted to Ukrainians

When Russia began its war of aggression against Ukraine, many OECD countries quickly granted immigration concessions to Ukrainian nationals, such as visa exemptions, extended stays or prioritisation of immigration applications. Significant differences in pathways, approaches to granting permits and associated rights, however, prevail between the European Union (EU) and non-EU OECD member countries.

The EU activated the Temporary Protection Directive

Since 2017, Ukrainian citizens holding biometric passports can travel to the Schengen Zone, which includes Iceland, Switzerland and Norway, without a visa for a period of 90 days, which allowed the majority of Ukrainians to enter the EU through regular pathways. The visa requirement for Ukrainian nationals travelling to Ireland was also lifted as an emergency measure on 25 February 2022. While some Ukrainian refugees continue onwards to non-EU countries, most have stayed in Europe.

On 4 March 2022, the Council of the European Union enacted by means of the Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/382, for the first time ever, the Temporary Protection Directive 2001/55/EC (TPD). The EU Member States (MSs) are bound to grant TPD status to both Ukrainian nationals who resided in Ukraine before or on 24 February 2022, as well as stateless people and foreign citizens who benefited from international (or equivalent national) protection in Ukraine before that date. Although some national variations may apply (e.g. scope extended to other categories, varying registration processes, longer permit validity, wider rights and benefits), MSs are bound by this legal framework and cannot offer a lower set of rights than those foreseen by the Directive to the beneficiaries of temporary protection (BTPs).

Denmark, while not bound by the TPD, mirrored the directive in its Special Act except for a few differences: stateless persons from Ukraine are not included, and a permit will be given for two years at first, with the possibility of extension for a further year. Switzerland, Norway and Iceland also offer similar protection schemes to Ukrainians through, respectively, the special “S permit” visa programme, the temporary collective protection scheme and a residence permit on humanitarian grounds.

Poland and Hungary distinguished from the beginning beneficiaries of protection arriving from Ukraine according to their nationality under national law. In both countries, the national temporary protection regime (provided in Poland by the Special Law adopted on 7 March 2022 and by the Gov. Decree 86/2022 in Hungary) only applies to Ukrainian nationals and their family members, while third-country nationals or permanent residents in Ukraine are subject to a distinct protection scheme, with different status or registration process. In July 2022, the Netherlands stopped granting temporary protection to third-country nationals with a temporary Ukrainian residence permit.

Moreover, people fleeing Ukraine have been able to apply for international protection. The availability of alternative protection routes is particularly important for those Ukrainian nationals who may not be eligible for temporary protection but are still in need of protection. This includes, for instance, Ukrainian nationals who were already present on the territory of a current host country prior to 24 February 2022 and thus are outside the scope of temporary protection in several EU MSs.

Approaches in other OECD countries

Other OECD countries outside the EU/EFTA responded to the Ukraine crisis and took, to varying degrees, measures to facilitate the entry and stay of people fleeing the war. The scope of these policies is often limited to Ukrainian citizens and their immediate family members with preference given to people with existing connections to the host country.

In some cases, non-EU/EFTA countries have established new Ukraine‑specific schemes and policies. The primary pathway for Ukrainians into the United States is through the Uniting for Ukraine (U4U) programme. While not a visa programme, this humanitarian parole option, launched on 25 April 2022, allows Ukrainian citizens and their immediate family members, who have a US sponsor, to travel to the United States and stay there for up to two years. During their stay, they are permitted to apply for work authorisation, and benefits including food stamps, Supplemental Security Income and Medicaid. The Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel (CUAET) offers Ukrainians and their family members free, extended temporary status for up to 3 years, allowing them to stay, work and study in Canada. Unlike applications for resettlement as a refugee and streams for permanent residence, there is no cap on the number of applications accepted under the CUAET. The 2022 Special Ukraine Visa scheme in New Zealand allows New Zealanders of Ukrainian origin to apply to bring family members still in Ukraine to the country. The United Kingdom meanwhile administers multiple parallel Ukraine‑specific schemes based on the applicants’ existing links to the country (the Ukraine Family Scheme, the Ukraine Extension Scheme, and the Homes for Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme).

Other non-EU/EFTA OECD countries use existing pathways to admit Ukrainians. Japan is granting the new arrivals 90‑day visas and the opportunity to switch to Designated Activities Visa for a year. Israel admits as immigrants Ukrainians approved to enter under the Law of Return. Those who are eligible but have not been approved may enter provisionally and complete their immigration process after arrival. In Australia, the Temporary Humanitarian Concern (THC) visa was made available for all Ukrainian nationals between February and the end of July. After this pathway expired, Ukrainian nationals who have entered Australia on a temporary visa and are unable to access normal visa pathways or return to Ukraine, may seek asylum by applying for a Protection Visa.

While the provisions of the TPD allowed the EU Member States to speed up administrative processes significantly, most non-EU countries did not introduce major changes to their processing procedures. The growth in applications has led to processing delays in some countries, including Australia, Canada, and the United States. In some instances, these delays were not caused just by the Ukrainian refugee crisis but also by an increase in applications after the resumption of visa processing following COVID‑19 lockdowns. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the number of visa applications for the year ending in March 2022 had been almost two and half times higher (+145%) than during the year before (Home Office, 2022[3]). The increase in applications from Ukrainians looking to enter and stay in the United Kingdom via one of the three new Ukraine‑specific schemes put further strain on the system, resulting in significant visa delays.

Initial support measures in OECD countries

OECD countries have also extended different types of support and assistance to new arrivals. The extent of formal reception measures in countries often depends on the type of permit granted. In the European Union, the EU TPD provides a set of harmonised rights for the beneficiaries, including rights to work (although restrictions may apply), accommodation, health care, and education for children under 18. As many arrivals are minors, the accompanying EU Commission (2022[4]) guidelines call for special attention to be paid to the child’s best interest and well-being during the initial response and later. In non-EU OECD countries, in most cases, sponsored arrivals are not eligible for the same levels of reception support as those seeking asylum or protection. The treatment of Ukrainians already present in a country’s territory prior to 24 February 2022 also varies widely across OECD countries. In most cases, these individuals are eligible for full reception support only if they seek asylum.

The unprecedented scale of the crisis prompted the European countries to co‑operate closely to manage the response to the Ukrainian refugee crisis. In March, the European Commission (EC) set up a “Solidarity Platform” to co‑ordinate the operational response among the EU Member States. It is used to collect information about the needs in host countries and to co‑ordinate the operational follow-up. The European Commission also supports non-EU neighbouring countries like the Republic of Moldova in strengthening their response by providing emergency support at border crossing points and transit points, funding to cover basic living conditions in accommodation centres and multipurpose cash assistance for vulnerable displaced people to cover their basic needs in Moldova. Moreover, 18 EU Member States and Norway have offered in-kind assistance to Moldova through the EU Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM).

Emergency shelter

Ensuring access to housing has been one of the main challenges in most receiving countries. The rapid influx of Ukrainian refugees soon exhausted existing reception facilities, especially as the numbers of other asylum arrivals did not decrease during the first half of 2022. Most host countries in Europe had to adapt and scale up their reception capacity. To house the large number of individuals fleeing Ukraine as quickly as possible, countries have relied on a mix of accommodation options, supplementing existing or newly-created reception centres or other emergency solutions with programmes supporting reception by private households (OECD, 2022[5]).

Many Ukrainian refugees found shelter in private accommodation. From the outset, private hosts and households in Europe opened their homes to displaced persons, in an unprecedented show of solidarity. Poland has relied extensively on a system of volunteers to meet housing needs. During first months of the refugee crisis, around half of those who arrived in Norway found shelter in private homes. Finland and Latvia estimated that the share of displaced persons in temporary private accommodation was around two‑thirds, while in Belgium and Italy it reached at times 85‑90%. Acknowledging the financial burden of hosting arrangements, some governments provide financial support to private hosts, including France, Poland, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and the United Kingdom. Ukrainians entering the non-EU OECD countries using sponsorship-based models (e.g. the United Kingdom and the United States) are also typically housed in private homes with the costs for this housing covered by the sponsor. Canada also foresees sponsors being responsible for housing, but some arrivals may be housed for two weeks in emergency accommodation.

Alongside private hosts and households, countries, including Germany, Greece, Ireland, and Sweden, have also relied on existing centres for asylum seekers. Many other countries, including Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Poland and Spain, have had to open new reception centres to cope with the demand. In Norway, more than 85 temporary emergency centres were opened across the country to house 20 000 refugees, with plans to dismantle them as demand dissipates (UDI, 2022[6]). An additional source of accommodation has been found in hotels, hostels, and schools. Some countries have even turned to emergency solutions, such as cruise ships, containers, tents, or mobile sheds.

Unlike previous large refugee flows, most people fleeing Ukraine are women and children. This composition raises specific challenges to the provision of adequate accommodation and countries are looking to mitigate different risks that these groups might face in relation to housing, including the risk of exploitation and gender-based violence. In Luxembourg, for instance, the Red Cross and Caritas organise house visits because of an identified risk of labour and sexual exploitation.

Developing housing solutions for children arriving from Ukraine unaccompanied or separated (accompanied by adults other than their parents) is an area of particular focus, especially in the EU (OECD, 2022[5]). Taking into account the best interest of the child, accommodation options are considered in close consultation with the competent child protection departments and other relevant social services. In the case of unaccompanied minors, these include foster placements, safe houses and specialised centres for minors or private accommodations (of family friends or acquaintances). In Poland and Germany, co‑ordination units have been set up to arrange accommodation of larger groups of unaccompanied minors and orphans, mainly in facilities of youth welfare services, youth hostels or recreation centres.

Access to assistance and public services

Measures have been taken across OECD countries to mitigate the risk of social and economic exclusion of refugees from Ukraine and to assist them in meeting their basic needs. Most host countries provide financial assistance, but levels and mechanisms vary widely across countries. The EU Member States, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, for instance, provide a financial subsidy enabling Ukrainian refugees to cover daily basic living expenses and to access decent accommodation. In Italy, BTPs may receive EUR 300 per person per month (EUR 150 per child) for a period of three months; in the Netherlands, the financial allowance is EUR 260 per person per month. Spain has a two‑phase system. During the first phase, BTPs receive maintenance aid (EUR 170/month for an individual) and pocket money, separately from a rental allowance. The second phase covers an allowance for basic needs. The total cost of providing assistance to Ukrainian refugees for the European OECD countries is estimated to be EUR 26.6 billion in 2022 (Box 4.1).

Outside the EU, financial support and subsidies may be available to Ukrainians only under certain conditions. In Canada, some provinces provide income support. In Korea, arrivals designated as refugees have access to financial support. In New Zealand, sponsoring family must commit to covering expenses for arriving Ukrainians.

All OECD countries offer access to health care, but similarly to financial assistance, the levels vary. Some countries offer access only to urgent primary health care while others have opened their social security systems more broadly to Ukrainians. The Slovak Republic provides access to emergency and necessary care. In Sweden, children have full access to health care, but adults may access only emergency health and dental care. In Australia, recipients of temporary humanitarian visa have access to Medicare. In Canada, Ukrainian arrivals are generally eligible only for urgent primary health care through the Interim Federal Health Program, but some provinces have extended access to include also other health care services (e.g. Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta). Most OECD countries have also recognised the need to provide access to mental health care. Often this is provided via hotlines, for instance in Belgium, Portugal and Poland. The Czech Republic also offers first psychological aid in reception centres.

As many arrivals are minors, access to public education for children has been a priority and it is available in all the EU and other OECD countries. Some countries also reported offering enrolment opportunities to pre‑schoolers, including Finland, France, Hungary and Latvia. The magnitude of inflows during the first months of the crisis, however, was significantly larger than anything some education systems had previously experienced, causing severe strains on classroom capacities, notably in Poland. In turn, several countries have sought to hire Ukrainian teachers to facilitate the teaching of large numbers of Ukrainian children, including Germany, Spain and the Czech Republic. For adults, immediate access to training and education is less common and regular entry requirements of educational institutions apply.

Box 4.1. Preliminary estimates of the financial impact of the Ukrainian refugee crisis in Europe triggered by Russia’s large‑scale war of aggression against Ukraine

While it remains difficult to assess the overall economic consequences of this unprecedented crisis, it is possible to estimate the costs associated with welcoming and supporting Ukrainian refugees in the European OECD countries. The estimates below cover a 10‑month period in 2022 and include direct financial support and housing, as well as education and health care costs. The methodology used follows that adopted in the OECD Brief on “The potential contribution of Ukrainian refugees to the labour force in European host countries” (OECD, 2022[7]). The distribution and demographic composition of the Ukrainian refugee population across these countries is assumed to remain fixed at the level observed in each country at the end of April 2022. However, it appears that the numbers of refugees from Ukraine in Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Romania used for this estimation are an overestimation for these countries as many people have either moved on or returned to Ukraine.

Living costs

The biggest share of all costs in Europe are related to the provision of accommodation and financial subsidies to Ukrainian refugees. Based on the refugee population estimates and the information collected on the financial support that people living in reception centres and private accommodation receive, as well as considering the financial transfers provided to hosting families, we can estimate that the total cost of providing housing and direct financial assistance in Europe is EUR 17.2 billion. The variation between countries, however, is significant. As expected, total costs are expected to be the highest for Poland at EUR 6.2 billion. In Germany, public expenditure on living costs is EUR 4.4 billion, while in Spain it is expected to reach almost a billion – EUR 981 million.

Education costs

To estimate the total cost of education, we assume that the average cost of education per grade equals the marginal cost. This is clearly an overestimation, but at the same time, including Ukrainian children in national school systems will require language training and other additional support for which costs are difficult to estimate at this stage.

The cost of ensuring educational access to Ukrainian refugees is estimated at about EUR 5.1 billion. Countries bordering Ukraine and those with the largest Ukrainian diaspora (i.e. Czech Republic, Italy, Germany and Spain) are expected to have the highest costs. In the Czech Republic, different education costs are estimated at EUR 352 million. In Poland, total educational expenditure is expected to reach EUR 1.5 billion.

Health care costs

On average, Ukrainian refugees are younger than both the general population in Ukraine and in the host countries. The calculations take this into account in relation to health costs. Overall, the health care costs are estimated to be about EUR 4.4 billion. Germany ranks first at EUR 1.4 billion, followed by Poland – which has lower per capita health care costs – at EUR 664 million. The Czech Republic ranks third at EUR 341 million.

Total costs

In total, the mass inflow of refugees from Ukraine is estimated to cost the European OECD countries about EUR 26.6 billion in 2022 (Table 4.1). The related costs are expected to be over EUR 1 billion in five countries – Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Spain and Romania. Germany and Poland are estimated to bear more than 50% of all costs. The highest expenditure per refugee, however, is expected in Switzerland, Belgium and Luxembourg, while the lowest cost per capita are in Hungary, Greece and Romania.

Table 4.1. Component costs (living, education, health) and total costs per country

|

Country |

Living costs, million EUR |

Primary education costs, million EUR |

Secondary education costs, million EUR |

Health costs, million EUR |

Total cost, million EUR |

Per capita cost, EUR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria |

263 |

78 |

88 |

163 |

592 |

7 360 |

|

Belgium |

400 |

51 |

47 |

91 |

589 |

12 626 |

|

Croatia |

49 |

7 |

11 |

17 |

84 |

4 210 |

|

Czech Republic |

1 265 |

144 |

208 |

341 |

1 957 |

5 028 |

|

Denmark |

86 |

66 |

23 |

82 |

257 |

8 288 |

|

Estonia |

90 |

31 |

16 |

30 |

166 |

3 898 |

|

Finland |

74 |

20 |

27 |

45 |

166 |

6 379 |

|

France |

391 |

56 |

73 |

186 |

706 |

8 031 |

|

Germany |

4 428 |

553 |

466 |

1 361 |

6 808 |

11 347 |

|

Greece |

45 |

11 |

8 |

15 |

78 |

2 707 |

|

Ireland |

176 |

29 |

23 |

69 |

297 |

10 064 |

|

Italy |

418 |

98 |

80 |

141 |

737 |

5 710 |

|

Latvia |

70 |

15 |

8 |

14 |

107 |

3 339 |

|

Lithuania |

153 |

14 |

24 |

32 |

223 |

3 581 |

|

Luxembourg |

24 |

13 |

10 |

16 |

63 |

12 487 |

|

Netherlands |

241 |

62 |

53 |

132 |

488 |

8 549 |

|

Norway |

106 |

43 |

13 |

73 |

236 |

12 491 |

|

Portugal |

95 |

24 |

17 |

31 |

168 |

4 028 |

|

Slovenia |

41 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

53 |

8 978 |

|

Spain |

981 |

115 |

81 |

181 |

1 359 |

8 009 |

|

Sweden |

75 |

114 |

21 |

115 |

325 |

7 525 |

|

Switzerland |

394 |

71 |

73 |

177 |

714 |

13 452 |

|

United Kingdom |

96 |

16 |

31 |

63 |

207 |

6 073 |

|

Poland |

6 207 |

1 133 |

356 |

664 |

8 360 |

5 225 |

|

Hungary |

104 |

84 |

96 |

87 |

372 |

1 730 |

|

Slovak Republic |

411 |

68 |

68 |

94 |

642 |

4 217 |

|

Romania |

499 |

149 |

148 |

207 |

1 002 |

3 012 |

|

Total |

17 182 |

3 069 |

2 072 |

4 432 |

26 756 |

|

|

Average |

|

|

|

|

|

6 173 |

Source: OECD Secretariat calculations.

Transitioning towards medium and long-term responses

With no clear end to the refugee crisis in sight, most host countries have started adjusting policies and activities to better address medium to long-term needs of their new Ukrainian communities. Early integration of refugees has many known benefits, particularly for helping newcomers become self-supporting, yet in the context of this refugee crisis, countries are balancing this consideration with their understanding that many Ukrainians intend to go home and will remain in the host country only temporarily. Moreover, the return and reintegration of Ukrainian nationals is seen as vital for rebuilding Ukraine when the time comes. Consequently, the long-term integration of newcomers has not been a priority in most countries.

As a speedy return to Ukraine is becoming less likely, a growing number of OECD countries have expanded Ukrainians’ access to integration measures. Language courses for Ukrainian refugees are now available in most host countries, and several countries, including Australia, Germany, and Canada, offer Ukrainian arrivals similar access to all integration measures – including civics education – as other refugee groups. In July, Estonia made attendance in the Settle in Estonia adaptation programme compulsory for Ukrainian BTPs. Other countries are offering programmes adapted to the circumstances of Ukrainian refugees. Norway, for instance, offers the Norwegian Introduction Programme (NIP) and language training for Ukrainians in English. The English language classes are supposed to prepare Ukrainian refugees for further studies in Norway, as many higher educational programmes require a certain level of English but not necessarily Norwegian.

Securing durable housing

Access to safe, secure and affordable housing is a precondition for refugees to restore stability in their lives, seek new opportunities and to connect with their new host community. Private citizens have stepped forward in many OECD countries, alongside NGOs, the private sector and government services to provide housing for Ukrainian refugees. Most of these solutions, however, are short-term. The transition to more durable accommodation is a looming challenge (OECD, 2022[5]).

Capacity constraints and dispersal

The rapid influx of Ukrainian refugees and the associated demand for housing is occurring in the context of significant pre‑existing capacity constraints and affordability challenges. Housing costs have been increasing in many OECD countries for the last decade with even further increases expected given inflationary pressures (OECD, 2022[8]; OECD, 2021[9]). This has not only limited available short-term housing options but will also have medium-to-long term implications.

The housing capacities are particularly strained in OECD countries bordering Ukraine, but also in countries further afield. The Netherlands, for instance, is one of the countries that identified housing shortages as a main challenge for hosting BTPs. Capacity constraints are particularly severe in metropolitan areas, where migrants generally tend to concentrate. In Poland, this led to a rapid growth of urban populations between February and April: the population of Warsaw grew by 15%, Kraków by 23%, Gdańsk by 34% and Rzeszów – closest to the Ukrainian border – increased by 53% (Wojdat and Cywiński, 2022[10]).

These severe housing pressures require countries to think about how best to distribute BTPs throughout their territory to alleviate regional pressures. Latvia announced that the number of refugees accommodated in each municipality will be in proportion to the municipality’s declared population and when a municipality reaches its capacity, the state will be entitled to transfer BTPs to other municipalities. Germany is using its existing dispersal system and plans to condition access to social assistance on the BTPs’ presence in their designated location. In Switzerland, the reliance on private hosts for housing in the early stages of reception circumvented the traditional cantonal dispersal system, but cantons are increasingly seeking to reclaim responsibility for dispersal to limit unequal pressures on specific municipalities. Some countries (e.g. France) have reported that dwellings in rural areas are unattractive to Ukrainians and remain vacant. Norway compensates municipalities for costs incurred in cases when the designated refugee never arrives.

Assistance with finding and securing accommodation

Alongside capacity constraints, Ukrainian refugees also suffer from an information gap, lack of proper documentation and sufficient income, and in some cases, negative prejudice against foreigners by landlords (OECD, 2022[5]). In this context, assistance with finding and securing accommodation is essential and many countries have implemented support measures. In many cases, financial assistance is provided to support with initial costs of arranging independent housing. Spain has provided funding to BTPs who wish to hire a real estate agent to help with the housing search. In Belgium, the Public Centres for Social Welfare provide an installation allowance that can be used to purchase furniture, among other things. Many countries, including Austria, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Switzerland, provide rent support if Ukrainian refugees do not have their own means of support.

Countries have also sought to address the information gap among arrivals, given their lack of familiarity with the local housing market. Some, for example France and Iceland, have made housing information available at reception centres or on their dedicated online information portals. Most OECD and EU countries have also created online platforms on which Ukrainians can access information about their housing options and their rights. Portugal for Ukraine, for instance, serves as a centralised forum for BTPs to receive information on how to access housing and other support in Portugal.

Ensuring educational continuity

The start of the 2022‑23 school year has seen many more refugee children entering national education systems in host countries, prompting countries to make significant efforts to scale up their classroom and teaching capacities. The implementation of multi-phased and long-term plans to integrate Ukrainian refugees into regular education systems is now a priority in most OECD and EU countries.

During the first months of the refugee crisis, many refugee students continued to follow a Ukrainian curriculum remotely (see Box 4.2). In Latvia, nearly half of all school-aged children continued distance learning until the end of the 2021‑22 school year. This meant that alongside facilitating integration into national systems for some, education ministries in many receiving countries also had to find ways in which to support Ukrainian school leavers, who wished to complete their studies with the Ukrainian high school exam.

Most host countries, however, are now looking to integrate Ukrainian students fully into national systems and classrooms, at least for compulsory education. Education systems are essential vehicles for integration as they provide opportunities for social interactions with locals, help to learn and practice local language and to understand the cultures of the host country. Integrated education systems also help the native population with being open to diversity and change.

Despite this, prior research suggests that the specific needs of refugee students are not always met by education systems in receiving countries, especially as refugees may also suffer from post-traumatic stress due to displacement, family bereavement and separation, and daily material stress (Spaas et al., 2022[11]). There are, however, ways to promote better outcomes, which include applying a holistic model responding to refugees’ learning, social and emotional needs, teaching them the host country’s language while also developing their mother tongue, providing flexible learning options and pathways, and creating opportunities for social interactions between refugee and other students (Cerna, 2019[12]).

It is also important to support learning outside classrooms, especially for children. Some OECD countries, including Austria, Canada, Estonia, Lithuania, Italy, and the United Kingdom, offered summer camps and schools for Ukrainian refugees to support language learning, build social networks and facilitate integration more broadly. Targeted measures to expand early childhood education and care (ECEC) to Ukrainian refugees, including offering financial assistance as most ECEC services still require at least a partial fee payment from parents, are also being considered.

Primary and secondary education

The pressures on education systems have been particularly severe in Europe, where the majority of Ukrainian refugees are located. In June 2022, the European Commission published a Staff Working Document, developed in consultation with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), as well as other stakeholders, outlining good practices and practical insights to support the EU Member States in the inclusion of displaced children from Ukraine in education during the 2022‑23 school year (European Commission, 2022[13]). The European Union law requires that migrant students enrol in the host country schools within three months of moving to the country and the EU Member States are encouraged to actively prepare displaced children to enter non-segregated mainstream education as soon as possible, as opposed to segregated or special schools.

This has not prevented schools from providing additional support to students when deemed necessary, whether by implementing individualised pathways or offering temporary reception classes, especially for pupils in higher grades. Many countries, including Belgium, Denmark, France, the Slovak Republic and Spain, offer some form of reception classes, which involve providing additional language training, psychological support, competency and knowledge assessments or some other assistance that should ease students’ transition into regular classes. In Portugal, a televised distance learning programme has been developed with 14 classes, each co-led by a Ukrainian teacher and a Portuguese teacher, and Ukrainian textbooks are made available to refugee students to provide continuity of learning (OECD, 2022[14]).

Despite the decision to prioritise integration into national education systems, host countries are still faced with a challenge of developing compatible systems and flexible pathways in education that would allow for a possible return to Ukraine in the future. An important element in this needs to be the maintenance of pupils’ mother tongue. In some countries, the teaching of origin-country language is embedded in formal education, for instance, in Sweden, where pupils who do not speak Swedish as their first language have the right to receive tuition in their mother tongue. Other countries, including Estonia, Latvia and Romania, have special Ukrainian schools, where students follow a national curriculum, but study some subjects in Ukrainian. In some Canadian provinces (e.g. Alberta and Manitoba), Ukrainian refugee students have been able to enrol in pre‑existing Ukrainian-English bilingual study programmes.

Box 4.2. Remote learning offered educational continuity for Ukrainian students

Refugees often face interruptions in schooling due to displacement, yet many Ukrainians enrolled in education were able to resume their studies remotely. Similarly to other countries, Ukraine had scaled up its digital learning modalities in response to COVID‑19 pandemic and was able to shift to remote teaching already in March 2022.

Ukraine’s main platform for distance learning is the All-Ukrainian Online School (grades 5‑11), offering lessons in 18 core subjects and methodological support for teachers, but many other resources are also available for all educational levels, including early childhood education. For example, the NUMO online kindergarten, developed in collaboration between UNICEF and the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, offers video classes for children aged 3 to 6. Online learning is also possible at Ukrainian universities.

Many host countries supported the dissemination of digital tools and resources through their platforms, including the School Education Gateway and the New Ukrainian School Hub. Sometimes these sources became part of educational integration. In Germany, some federal states such as Berlin and Saxony offer the possibility to follow online courses of the Ukrainian Ministry of Education for the duration of reception classes, while receiving German language and in-person teaching support.

These existing digital resources are also used to support maintaining a link with Ukraine to support possible return to the country. Ukrainian policy makers view the refugee situation as temporary and the Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Science stresses the need for students to continue their studies in Ukrainian language, culture and history instead of, or at least in addition to, attending schools in host countries (OECD, 2022[15]).

Vocational education and training (VET)

Governments and other interested parties are also laying foundations for more lasting measures that go beyond compulsory education. Providing VET in host countries can be a particularly promising pathway, as occupations typically entered through VET are in high demand. These occupations can grant high expected returns to Ukrainian refugees, host country labour markets, and for the rebuilding of Ukraine (OECD, 2022[16]). The European Commission (2022[17]), in its guidance published on 14 June 2022, invited the EU MSs to ensure swift access to initial VET, including apprenticeships, and to provide, as quickly as possible, targeted upskilling and reskilling opportunities, including VET and/or practical workplace experience.

Refugees, however, often face barriers to entering VET and tend to be less successful in completing their studies than their native peers (Jeon, 2019[18]). Specific challenges include relatively weak language skills, lack of relevant social networks and knowledge about labour market functioning, as well as possible discrimination in the apprenticeship market, which need to be addressed to make VET systems work for all Ukrainian refugees.

Several countries have taken specific measures to facilitate and ease access to both upper secondary and adult vocational training for Ukrainian refugees, including waiving some entry requirements (OECD, 2022[19]). Latvia, for instance, exempts Ukrainian minors from the mandatory state examination for admission in a VET programme. The majority of European OECD countries, as well as Australia and the United States, offer Ukrainians access to adult vocational training as part of job training through public employment services or adult education courses. Countries are also adopting policies to make the hiring of Ukrainian VET teachers easier, for instance Germany and the Netherlands.

Tertiary education

Most host countries have sought to facilitate access to higher education institutions for Ukrainian refugees, yet there is a significant variety in policy responses. In many cases, Ukrainian students have been able to benefit from pre‑existing policies and measures in place for refugee students. In Portugal, for instance, Ukrainian students were able to benefit from the existing framework for the admission of students in humanitarian emergency to Higher Education Institutions with full access to social grants, including scholarships, and equality to national students’ status for the purpose of tuition fees. Most EU countries use and develop measures and instruments already in place, which generally include host language training or support, psychological counselling, academic guidance, introductory courses, scholarships, and reserved study places (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2022[20]). Some countries have also introduced exceptional policies such as full tuition fee exemption for Ukrainian refugees, including Austria, Ireland, Poland, Romania, Slovenia and Sweden.

Higher education institutions (HEIs), however, have a substantial degree of autonomy in most countries and have implemented their own exceptional measures to support Ukrainian students and scholars. These have included opening up of university and research positions, scholarships, and different types of assistance for Ukrainian citizens as well as pledges to enrol students and reducing and in some cases waiving tuition fees. For instance, more than 50 universities and research institutions in France offer Ukrainian refugees different types of assistance, including financial, to resume their studies. Such HEI-led initiatives aimed at Ukrainian tertiary students are to varying degrees in place in most OECD countries.

Measures have also been put in place to support Ukrainian international students, who were already studying in host countries prior to February. The United States announced changes in work rights for Ukrainian students (e.g. suspending certain employment authorisation rules for Ukrainian students who are experiencing severe economic hardship as a direct result of the war). The Canadian Government launched a fund to support research trainees from Ukraine currently in Canada or who wish to come to Canada to study or do their research. The Norwegian Government has also established a grant scheme for Ukrainian students in Norway who are struggling financially due to the war.

Some financial support provided to university students is conditional on return to Ukraine and contributing to reconstruction, most notably that provided by the Ukrainian Global University (UGU). The Ukrainian Global University is a vast network of educational institutions, who, in partnership with the Office of the President of Ukraine, support Ukrainian high school and university students, scholars, tutors to take up studies in host countries by providing them with scholarships and fellowships. The initiative requires all students to return to Ukraine after finishing their studies to help rebuild the country post-war.

Promoting employment and employability

Since the start of this refugee crisis, only a relatively small number of those of working age fleeing Ukraine have entered the labour market in the EU and other OECD countries, though the number of people wanting to do so is expected to rise. This will impact both employment levels and expand labour force in host countries in the coming years. By the end of 2022, between 850 000 and 1.1 million working-age people are expected to enter the labour market in Europe, with the estimated impact on labour force being about 0.5%, about twice as large as that of the 2014‑17 inflows (OECD, 2022[7]). Considering the strong geographical concentration of Ukrainian refugees, most of the impact on labour force will be observed in a few countries, reaching the highest levels in the Czech Republic (2.2%), Poland (2.1%), and Estonia (1.9%). Ensuring a swift and effective labour market integration is essential for allowing refugees to rebuild their lives and achieving stable livelihoods, yet refugees often struggle with finding employment or remain underemployed. Some of the characteristics of Ukrainian refugees are likely to improve their integration prospects and employability, including their educational profile, existing social networks, and immediate labour market access in many host countries, while others on the contrary may hinder them, namely that most arrivals are women with children and other dependents.

Job search and matching

Over the last decade, the global community has been taking steps to improve refugees’ labour market outcomes (OECD/UNHCR, 2018[21]). It remains a priority also during this crisis and Ukrainian refugees have been granted the right to work almost immediately in most host countries – even if this right remains subject to applicable professional rules and national labour-market policies (OECD, 2022[19]). In the EU Member States, the right to work is covered by the Temporary Protection Directive, with the European Commission (2022[17]) encouraging MSs to provide the broadest possible access to the labour market. Other European countries not bound by the directive and non-EU countries, including Canada, Denmark, Japan, Norway and Switzerland, have introduced their own national regulations to ensure immediate labour market access for Ukrainian refugees.

Access to the labour market, however, is not sufficient to guarantee employment and countries choose to offer further support to Ukrainians for finding a job, although the degree and nature of support provided varies significantly. In many countries, including most EU countries, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, public employment services play a key role when it comes to providing information on jobs, offering necessary training and acting as matchmakers between refugees and employers. In some countries, specific units have been created for this. For instance, Portugal’s Institute of Employment and Vocational Training has mobilised a task force to co‑ordinate skills matching between Ukrainian arrivals and Portuguese businesses.

Different matching tools are also available to ease the process. Several countries have created online portals with varying degrees of in-built matching systems to connect BTPs to companies and suitable jobs, including Estonia, France, Poland and Portugal. At the EU level, the European Commission is currently developing a web-based EU Talent Pool for displaced people from Ukraine to post profiles, following a scenario developed by the OECD (2022[22]). Employers will be able to consult an overview of the registered profiles via appointed national contact points to learn if the skills they are looking for are represented in the Ukrainian community in their area.

As with housing provision, many ad hoc matching pages sprung up on social media with private citizens and business owners offering job opportunities to Ukrainian refugees. Despite the general goodwill associated with these initiatives, there are also clear risks. Considering their vulnerabilities, including psychological trauma, lack of financial resources, inability to speak the local language and limited awareness of their rights, Ukrainian refugees are at high risk of exploitation, prompting both labour inspectorates and law enforcement agencies to enforce preventive and corrective interventions. The Ombudsman’s Office in the Czech Republic has warned that Ukrainian refugees should trust only official information and avoid labour brokers.

Entrepreneurship is another pathway for self-reliance among Ukrainian refugees and some host communities and countries provide entrepreneurship training courses for new arrivals (e.g. Ireland). This has also been supported at times by the Ukrainian Government. For instance, the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine, the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology of Poland and the Polish Investment and Trade Agency with the support of Mastercard have opened a support centre (Diia.Business) in Warsaw, where Ukrainian refugees can learn how to start a business in Poland.

Skills assessment and recognition

The information currently available on the educational levels of Ukrainian refugees suggests a higher share of them are tertiary educated compared to most other refugee groups. Recognising their qualifications and educational credentials thus plays a particularly important role in ensuring their successful integration in the labour market. Many Ukrainians arrive with all or partial educational documents, aiding the recognition processes immensely. Ukraine has also been at the forefront in digitalising student data and host countries have been able to call on Ukrainian authorities to verify national educational documents. Despite this, a destruction of infrastructure has increased response times and receiving countries have also used alternate measures to speed up skills assessment and recognition processes.

Numerous tools are available to facilitate skills assessment and recognition in these instances, most of which have been developed in the context of prior refugee crises. The European Qualifications Passport for Refugees (EQPR), developed by the Council of Europe, is a standardised document that explains the qualifications a refugee is likely to have based on the available evidence. While not a formal recognition act, it summarises and presents available information on the applicant’s educational level, work experience and language proficiency. Drawing on similar methodology, the UNESCO Qualifications Passport (UQP) is also available for non-European countries. Different means are also available at national levels. For instance, MYSKILLS test in Germany, available for 30 professions in six languages, allows job seekers to identify and demonstrate their professional skills without corresponding documentation. The European Commission is also working with the European Training Foundation (ETF), Ukrainian authorities and the EU MSs to compare the Ukrainian national qualification framework and the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), to make Ukrainian qualifications more easily understandable across borders for employers, education and training providers alike.

Another form of support available is the removal of qualification requirements or the expedition of skills evaluations and credential recognition. In the case of the Ukrainian refugee crisis, this has been used mainly in relation to teaching and health care professions, where regular recognition procedures can be very lengthy. Poland has shortened the timeline for recognition of medical qualifications for this group, and Spain is undertaking fast-track assessment of medical degrees and other qualifications. Lithuania exempts BTPs from language requirements for employment (including teaching) for a period of two years. Sweden has not introduced a special programme for Ukrainian refugees, but BTPs are able to take advantage of the existing fast-track for teachers, pre‑school teachers and medical professionals.

Addressing gender-specific needs

Despite the often‑immediate access, Ukrainian refugees have been relatively slow to enter the labour force in host countries. In Austria, as of June 2022, only about 10% of all eligible working age BTPs had signed up with the Austrian Public Employment Service. There are several possible reasons behind this, including the uncertainty about the length of stay, but the gender profile of arrivals may also play a role. Immigrant women in general are more prone than native‑born women to be in long-term unemployment, in involuntary inactivity and at risk of over-qualification, yet the risk is even higher for refugee women (Liebig and Tronstad, 2018[23]). Moreover, refugee women can be particularly vulnerable to labour market exploitation and gender-based violence. Authorities uncovered evidence of human trafficking already in the early weeks of the Ukrainian refugee crisis (Hoff and de Volder, 2022[24]). These and other gender-based risks and challenges need to be addressed to facilitate meaningful access to employment for Ukrainian refugees.

A major barrier to labour market entry is access to affordable dependent care, especially as the majority of arrivals are women with children or other dependents. Some host countries have sought to address this. In France, for instance, children up to the age of three have access to public day-care, free of charge until the end of 2022. Poland has opened hundreds of new childcare centres. Yet many countries were facing severe shortages of care places and staff even prior to the new influx, so ensuring longer-term access to affordable care services remains a challenge.

In addition, targeted counselling and job training can help women participate in host countries’ labour market. Access to job training, work placements and professional networks is particularly important to ensure their labour market integration at appropriate skill levels. Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada, for instance, sponsors Her Mentors project (Women’s Economic Council) that connects migrant women (including Ukrainians arriving under the CUAET) to mentors, also offering skills training to advance employment or self-employment opportunities and supporting women in joining professional associations.

Emerging challenges

Phasing out temporary protection in the EU and beyond

Considering the scale of flows, rapid activation of the Temporary Protection Directive helped avoid overwhelming national asylum systems, better manage unprecedented levels of arrivals and ensure the immediate protection and rights of those eligible in the EU. Yet as its name indicates, this is by design a temporary solution and intended to last initially for a year. After that, it may be extended for further periods (from six months to a two‑year maximum). A further extension for up to a third year is also possible, but on a qualified majority vote on a proposal from the European Commission. Once the temporary protection regime ends, the regular rules and regulations on protection and on foreigners again apply. Considering the total numbers of BTPs to date, transitioning from temporary protection to other legal bases for stay will be a major administrative undertaking in many countries, requiring them to start preparing for this transition as soon as possible.

Temporary and subsidiary statuses also come with several embedded challenges that countries need to take into account as the refugee crisis continues. They make sense for short-lived crises, but are less appropriate in the event of long-term displacement as temporary protection generally grants fewer rights than conventional refugee status. Displaced persons may find themselves living with precarious situations with limited integration prospects (OECD, 2016[25]). Moreover, temporary protection is based on an expectation of eventual return. It can be, however, nearly impossible to predict return flows. Returns can vary significantly between groups. In the context of large‑scale displacement experienced in Europe due to armed conflicts during the Yugoslav Wars from 1991 to 2001, which led to the adoption of the TPD in 2001, the majority of Bosnian refugees did not go home after active warfare ended in Bosnia, while in contrast, most Kosovar refugees returned to Kosovo en masse (Koser and Black, 1999[26]; OECD, 2016[25]). The return decisions within Ukrainian refugee groups will most likely vary significantly as well, depending on a range of factors, including the region of origin, cultural background, economic and family circumstances. While many will return, there is a need to ensure that alternative pathways for settlement are available for those who cannot return or who decide against returning to Ukraine when temporary protection regime ends.

Some EU countries, most notably Poland, are already taking first steps towards phasing out temporary protection. Legal amendments have been introduced stipulating that Ukrainians who left their homeland because of Russian aggression can apply directly for a three‑year temporary residence permit. The application may be submitted no earlier than 9 months from the date of entry and no later than 18 months from 24 February 2022. This is in place to ensure continuity regardless of whether temporary protection is extended or not. This pathway, however, is not available to those Ukrainians who already have another legal basis for staying in Poland independently from temporary protection, including recipients of international protection.

Challenges with transitioning away from temporary solutions may also arise elsewhere. Initial steps to phase out such systems have already been taken also outside the European Union. In particular, Australia has closed its Temporary Humanitarian Stay pathway, guiding Ukrainian nationals who have arrived on a temporary visa and are unable to return to Ukraine to apply for asylum. However, with some temporary schemes it is unclear if and how Ukrainians could transition to other statuses if these programmes were to end before return to Ukraine is possible. In the United States, Ukrainians arriving through the Uniting for Ukraine (U4U) parole programme are not provided with an immigration status and in most cases are not eligible for immigration status or lawful permanent residence after their parole ends. In Norway, contrary to other humanitarian permits, temporary collective protection granted to Ukrainians does not count towards a permanent residence and there is no clear pathway to long-term residence.

Transitioning from exceptional measures to mainstream solutions

Most host countries have introduced temporary exceptional measures to support the reception of new arrivals. In some cases, such measures have been directed at refugees themselves, for instance, as one‑time or temporary cash assistance or as free services. Many European countries, for instance, have made provisions for temporary free travel for Ukrainian displaced persons, including Austria, Belgium, France, Germany Lithuania, Italy, Poland and Sweden. In other cases, host communities have been the recipients, e.g. financial support provided for hosting private households. In many cases, such exceptional measures have been essential for managing the influx. Poland and the Slovak Republic, for instance, report that the provision of financial compensation for hosting has been an increasingly important consideration for private hosts over time and has helped to ensure the availability of temporary housing options in otherwise over-strained market conditions (OECD, 2022[5]).

These temporary measures, however, are not expected to last forever. Many of them have already expired or are expected to end later in 2022. As the refugee crisis continues, countries either need to extend these measures or provide support through mainstream measures and social security systems. Some EU countries have tried to mainstream general support measures from the start. In the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Luxembourg, for instance, BTPs access social services on the same basis as other residents. Since 1 June, Ukrainian BTPs also have access to the general social security system in Germany.

While mainstreaming should be a longer-term goal in most contexts, supplementary exceptional measures may still be needed medium-term to prevent general social security systems from becoming overwhelmed. This is particularly important in the context of housing. In July, several Latvian cities, including Riga, stopped accepting Ukrainian refugees, as the previous state allocation for the accommodation of the refugees was substantially reduced (to EUR 3.5 per day) and municipalities deemed this to be insufficient to secure private housing in local market conditions. There are also limited alternatives available in such cases. Access to social housing is generally not an option as available stocks are limited and under great pressure. Social housing stock ranges from over 20% of the housing stock in the Netherlands, Denmark and Austria, to less than 2% in Latvia, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Estonia, Lithuania and the Czech Republic (OECD, n.d.[27]). Stock is particularly sparse in the main countries of first reception for Ukrainians, and allocation is already managed by waitlists in many countries. In this situation, giving priority placement to Ukrainian refugees in social housing ahead of other eligible groups is unlikely to be an option.

Addressing secondary movements

Mobility inside and outside the EU of Ukrainians has remained at a high level ever since 24 February. Right from the start, cross-border movements went in both directions, as people fleeing the country crossed those from the diaspora returning to fight. Meanwhile visa-free travel in the EU allowed refugees to move between the EU Member States before registering for temporary protection or seeking protection outside Europe. Many Ukrainians are also beginning to return to Ukraine – whether temporarily or permanently – and in July 2022, about the same number of Ukrainian citizens were crossing the border in both directions for the first time since early February.

While expected, these movements can become a source of concern for many host countries, especially in Europe and the Schengen Area. In recent years, the EU Member States have seen an increase in secondary movements by beneficiaries of international protection and limiting secondary movements of asylum seekers has been a policy priority since the 2015‑16 crisis (EASO, 2021[28]). In the context of temporary protection and the current crisis, concerns may arise that some individuals could abuse the system by registering for protection and collecting social assistance in one or more EU Member States, while residing elsewhere, including Ukraine.

The European Commission has developed an EU platform for the exchange of information on BTPs, allowing the EU MSs to exchange information on registered persons in real time, including addressing instances of double or multiple registrations and limiting possible misuse of the system. Some countries are also taking steps to manage secondary movements of Ukrainian arrivals. In Switzerland for example, protection status S may be revoked in case of prolonged travel home or abroad. Following consultation with the cantonal and city authorities, the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM) decided that it may revoke the protection status of persons if they return to their home country for more than 15 days in a quarterly period. This also applies if a Ukrainian refugee spends more than two months in a third country. While there are no plans to revoke residence permits granted on the grounds of protection under the TPD, Sweden and some other EU Member States have stated that BTPs may lose the right to aid (including housing and financial support) if they leave the country for extended periods.

Preparing for changes in public opinion and support

Across host countries, Ukrainian refugees have been welcomed with unprecedented and overwhelming support. During the first months of the refugee crisis, many host governments were able to rely heavily on civil society and private citizens, who volunteered their time and resources to help Ukrainian refugees, ensuring that reception systems did not collapse under the influx of new arrivals. Public opinion and support for displaced populations, however, tends to wane over time, making it unlikely that host governments can rely on this high level of public support in the long term. Incoming evidence is already suggesting that compassion fatigue is beginning to set in as donations and volunteering efforts are declining, and public anxieties are on the rise in response to record inflation in Europe and beyond.

Changes in public mood and support are not necessarily a sign for governments to change their policies towards Ukrainian refugees, but, instead, an indicator that more attention needs to be paid to addressing public anxieties and restoring confidence in migration and integration systems. Public narratives around migration tend to be depicted as swaying from one extreme to another: from full solidarity to anti‑immigrant hostility. In reality, public opinions are less binary and people hold multiple, competing beliefs and opinions at the same time, creating opportunities to prepare for changes by promoting solidarity and defusing tensions (Banulescu-Bogdan, 2022[29]).

Perceptions of unfairness in particular can undermine solidarity and harm public support for refugees. Resentment is easily triggered in response to perceived privileged treatment of newcomers compared to other groups. For instance, some political parties in Ireland have already voiced their opposition to housing Ukrainian refugees ahead of existing long-term housing applicants. To minimise possible backlash, some countries (e.g. Belgium) are deliberately avoiding introducing Ukraine‑specific social programmes and measures where possible to minimise the appearance of special treatment.

Countries are also taking steps to demonstrate that the concerns of local citizens are treated seriously and that there are long-term plans in place to manage these pressures on host societies. Several countries, such as Australia, Denmark, Ireland and Italy, already follow a co‑ordinated approach to communicating their crisis response to the public as well as presenting a coherent long-term strategy for Ukrainians’ integration (OECD, 2022[30]). In other countries, regular exchanges and close communication with local communities to identify turning points in public opinion are a core part of their longer-term response plans to the refugee crisis. Estonia, for instance, is planning to start organising regular community-based roundtables to hear and respond to the concerns people may have in relation to the Ukrainian refugee crisis. While it is impossible to entirely allay the fears of the public, addressing these anxieties head on can prevent them from growing into existential threats fuelling anti‑immigrant sentiment.

References