Shunta Takino

Pedro Isaac Vazquez-Venegas

Shunta Takino

Pedro Isaac Vazquez-Venegas

Investors integrating human capital and environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria in investment decisions show a growing interest in companies that promote the health and well-being of their own employees. This special focus chapter provides a description of developments to steer investment towards companies that promote the health and well-being of employees. It also maps ongoing initiatives to facilitate standardised disclosure and reporting by companies on how they are promoting the health and well-being of their employees.

Investing in companies that promote health and well-being ensures that investments are socially responsible and aligned with environmental, social and governance considerations (ESG). Such practices may also be financially profitable for investors.

A growing number of investors is seeking to promote socially responsible and sustainable investments, for example on those in line with the Sustainable Development Goals. This is reflected in the growing consideration of human capital and ESG criteria in investment decisions.

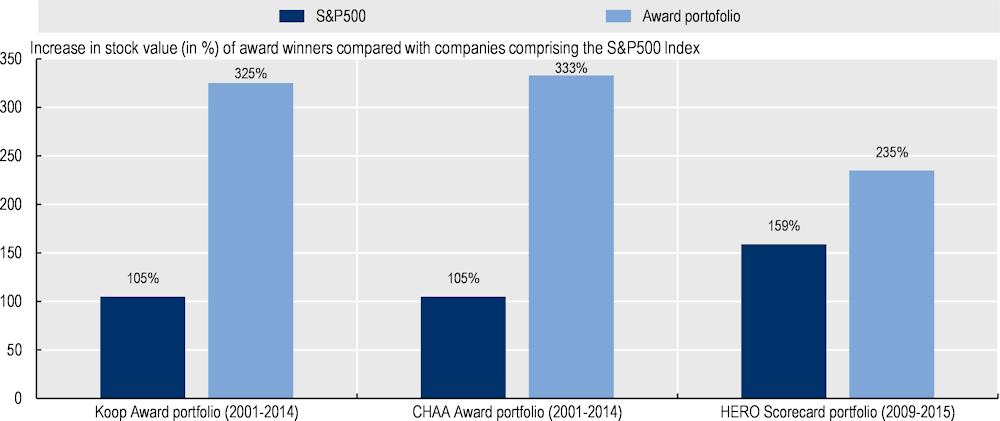

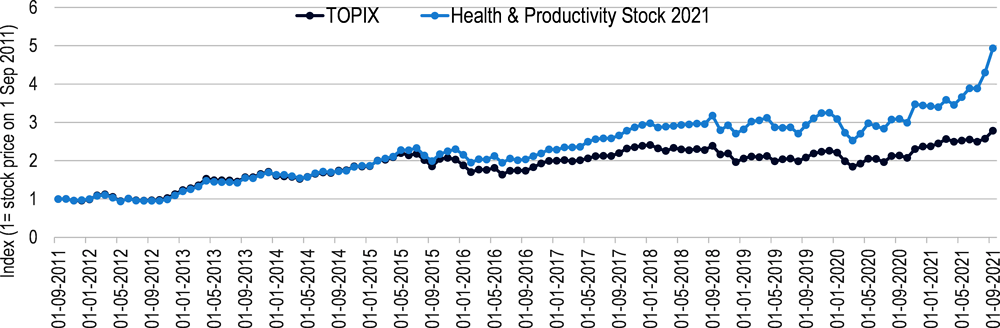

The effective implementation of workplace health and well-being programmes is correlated with stronger financial performance, although further evidence is needed to determine if this relationship is causal. In the United States, between 2001 and 2014, the stock value of companies awarded for their workplace health programmes appreciated up to three times more than the group of companies comprising the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index. In Japan, between 2011‑21, the stock value of the group of companies selected for the Health and Productivity Stock Selection in 2021 outperformed the average of companies comprising the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

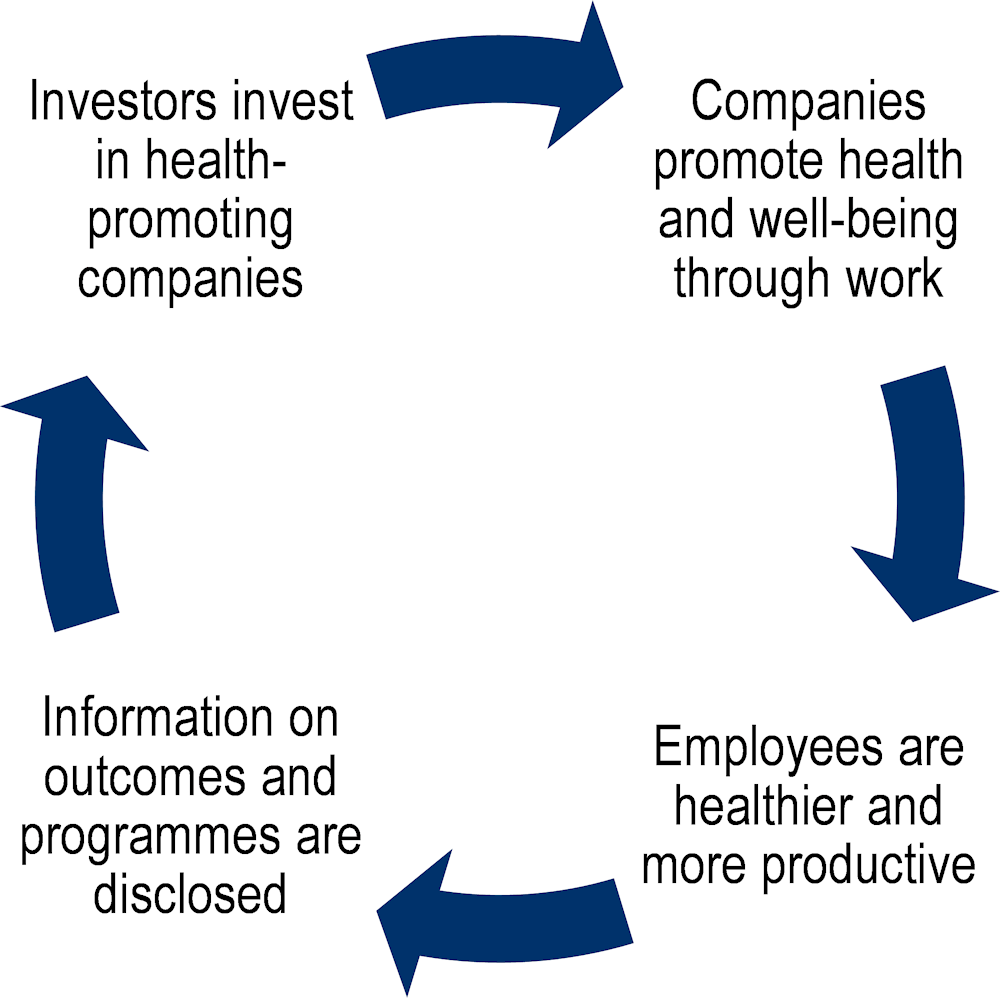

Steering investment in health-promoting companies can create a virtuous cycle that amplifies the incentive for companies to promote the health and well-being of their employees. The lack of standardised information and data allowing the identification of health-promoting companies limits the possibility for this virtuous cycle from being unlocked.

If investment can be steered towards health-promoting companies, this creates a virtuous cycle because a company that promotes the health and well-being of employees is rewarded not only with a healthier workforce, but also with an increased likelihood of receiving investment.

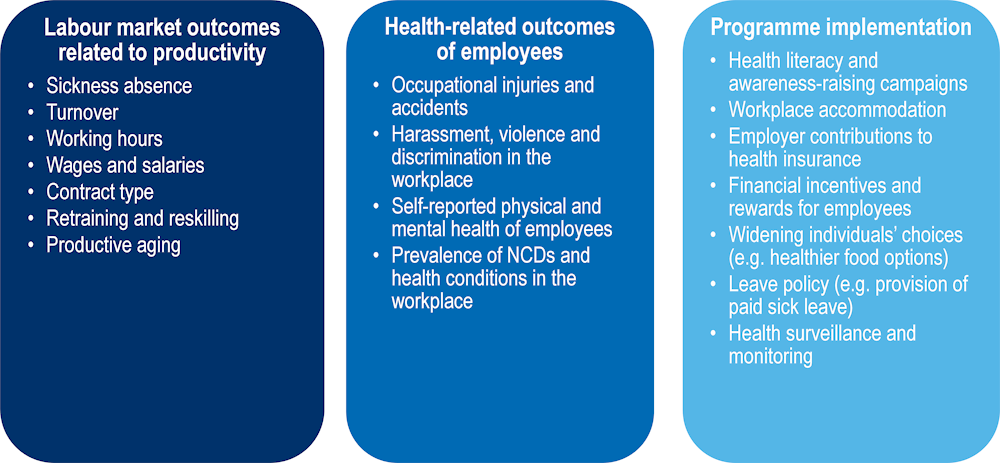

Information that offers insight into how well companies are promoting the health and well-being at the workplace falls into three categories. These are (1) labour market outcomes related to productivity, (2) health status of employees and (3) the implementation of health promotion programmes by companies.

The protection of data privacy and preventing discrimination must be a key consideration when collecting or processing any personal data, especially in relation to health and well-being. Existing regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) forbid the collection of health data at the individual level except under certain exemptions.

Governments thus have an important role – working together with relevant stakeholders – to encourage the disclosure and reporting of companies’ efforts to promote health and well-being at the workplace. It is important that companies not only report relevant information, but also that standardised and harmonised mechanisms and indicators are used. Three types of initiatives were identified which include:

Government-led reforms for mandatory disclosure: in the United States, a bill has been introduced to the Senate but not yet passed, which would require disclosure of a range of human capital metrics. The European Union has reporting requirements on non-financial performance, but these are limited and not centred on employee health and well-being.

Voluntary initiatives to promote disclosure: these are widespread and led by a range of stakeholders and often involve governments, charities and investors. ShareAction, a charity promoting responsible investment, heads the Workforce Disclosure Initiative, whereas the Japanese Government leads the Health and Productivity Management Programme in Japan.

Initiatives to standardise and harmonise disclosure mechanisms: such initiatives are typically led by organisations with a standard-setting influence, which in turn enhances comparability across countries and companies. The Global Reporting Initiative, which sets standards used by 75% of the world’s largest companies in their ESG reporting, includes the implementation of health promotion programmes in its reporting guidelines.

Institutional investors and private funds are showing a growing interest to direct investment towards companies that promote the health and well-being of their employees, and the COVID‑19 pandemic has placed an additional spotlight on the importance of the health and well-being at the workplace. This special focus chapter begins by looking at how and why investors are increasingly interested in employee health and well-being (Section 5.2), then discusses how a lack of standardised information, data and metrics hampers efforts to invest in companies that promote health and well-being at work (Section 5.3). Section 5.4 proposes a categorisation of disclosure mechanisms – both voluntary and obligatory – as well as efforts to standardise and harmonise indicators used across countries. Section 5.5 highlights other financing mechanisms such as social impact bonds in the case of financing health prevention and return-to-work programmes, and Section 5.6 concludes the chapter.

Investing in companies that guarantee safety at work and promote health and well-being, ensures that investments are socially responsible and aligned with environmental, social and governance criteria (ESG) (described in more detail in Box 5.1) and with the Sustainable Development Goals. While the use of ESG criteria by investors has been mainstreamed with over USD 30 trillion in assets incorporate ESG assessments (OECD, 2020[1]), the focus has primarily been placed on the environmental ‘E’ pillar.

ESG criteria are used by institutional investors and private funds as they seek to align their investments with sustainability and social goals.

The environmental ‘E’ pillar encompasses the effect that companies’ activities have on the environment (directly or indirectly). The ‘E’ pillar is being increasingly used by investors who seek long-term value and alignment with the green transition (OECD, 2021[2]).

The social ‘S’ pillar encompasses how a company manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates. It includes workforce‑related issues (such as health, diversity, training), as well as broader societal issues such as human rights.

The governance ‘G’ pillar encompasses a company’s leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls, transparency policies for public information, codes of conduct or shareholder rights.

To ride the wave of ESG investments, there has thus been a call from investors, health experts and other stakeholders to better integrate employee health and well-being and broader public health considerations within ESG criteria. This could be in part addressed by strengthening the social ‘S’ pillar and human capital considerations which have remained underdeveloped within ESG criteria (Siegerink, Shinwell and Žarnic, 2022[3]). This underdevelopment of the ‘S’ pillar is in part due to the challenge of quantifying social impact, but it may also reflect biases towards data that already exists or is easier to collect for companies. Others have called for the addition of a separate health ‘H’ pillar. For instance, the initial report of a four‑year partnership between Legal & General, a UK-based asset management company, and the Institute of Health Equity at University College London, outlines that the expansion of ESG to “ESHG” could be an important measure to ensure businesses play a role in promoting health and reducing health inequities (Institute of Health Equity, 2022[4]).

Some companies – recognising the importance of employee health – are also integrating health and well-being in their ESG reporting. In 2020, Centene, which is among the 100 largest companies in the United States, added health to its ESG reporting in line with its commitment to “cultivate healthier lives”, and thus since then, it has published an annual report on its ESHG performance to the community and investors (Centene, 2021[5]). Johnson & Johnson, the pharmaceutical and health multinational corporation, also includes employee health within its Health for Humanity 2025 Goals, and in 2021, identified indicators to be used to assess their progress in ensuring the healthiest workforce possible (Johnson & Johnson, 2022[6]).

Many investors also see employee health and well-being as a key component of human capital (defined in Box 5.2) which is another area of growing interest among investors. There is increasing awareness that the performance of companies hinges on their employees. According to an estimate by the Global Intangible Finance Tracker,1 intangible assets such as human capital, employee health and culture hold more than half (54%) of a company’s market value (Brand Finance, 2021[7]). A separate assessment by Ocean Tomo2 has also found that intangible assets account for 90% of the market value of the Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500), the stock market index tracking the 500 largest publicly traded companies in the United States, and for 74% of the market value of the S&P Europe 350 (2021[8]).

Human capital refers to “the stock of knowledge, skills and other personal characteristics embodied in people that help them to be more productive” (Botev et al., 2019[9]). As discussed in Chapter 2, health status – including physical and mental health – directly affects productivity, and is thus by definition, an important component of human capital. In the OECD Well-being Framework, premature mortality, smoking prevalence, and obesity prevalence are thus all included as human capital indicators (OECD, 2020[10]). In the context of efforts to assess the performance of companies by their human capital, proposed and existing indicators include a range of measures that are closely related to health, such as turnover rates, incidence of sickness absence, and working hours.

The world’s leading investment funds and asset management companies have clearly outlined their expectation that companies disclose their human capital. This has at time extended to include considerations around employee health and well-being. For instance, BlackRock, one of the largest investment management companies worldwide, states in a document outlining its approach to human capital management from 2022 that it “believes that companies that successfully engage and support their workforce, are better positioned to deliver sustainable financial returns” (BlackRock, 2022[11]). The document cites the importance for businesses to create a healthy workplace culture and to support the physical and mental health and safety of employees through measures such as paid sick leave and counselling support.

The implementation of workplace health programmes is also correlated with stronger financial performance, potentially attracting investors and private funds. As shown in Figure 5.1, studies suggest an association between the implementation of workplace health and well-being programmes and stock market performance at the company level, according to data from three types of workplace health programme award or self-scoring measures (Goetzel et al., 2016[12]; Grossmeier et al., 2016[13]; Fabius et al., 2016[14]). For instance, the stock performance of recipients of the C. Everett Koop National Health Award – which provides awards for companies with outstanding measures to improve health promotion in the workplace – appreciated three times more than the average among companies comprising the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) 500 Index in the period from 2001 to 2014 (Goetzel et al., 2016[12]). This association also holds for two other measures, the Corporate Health Achievement Award (CHAA) that rewards employee health programme, and the Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) Scorecard that is based on self-scoring of the health programme performance by employers themselves. The lower effect of the HERO Scorecard may also be the result of a shorter time period. As discussed in Box 5.4, there is also promising evidence that suggests that companies that have been chosen for Stock Selection in the Health & Productivity Management Programme in Japan perform better on the Tokyo Stock Exchange (Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry of Japan, 2021[15]). The evidence from the United States and Japan should be interpreted with caution as the association of health promotion and financial performance is not evidence of a causal relationship. Such an association may also reflect strong business management and leadership that is conducive both to the implementation of effective workplace health programmes and to increases in profitability and revenue (O’Donnell, 2016[16]).

Note: S&P500 refer to companies comprising the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index, which includes the 500 largest companies listed on stock exchanges in the United States. CHAA Corporate Health Achievement Award. HERO Health Enhancement Research Organization. The period over which stock value increases are compared, is 2001‑14 for both the Koop Award and the CHAA Award, but is less than half the length (2009‑15) for the comparison of stock values for the HERO Scorecard. This may explain the smaller differential between the stock values of companies comprising the S&P 500 and HERO award-winners.

Source: Goetzel, R. et al. (2016[12]), “The Stock Performance of C. Everett Koop Award Winners Compared With the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index”, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000632; Grossmeier, J. et al. (2016[13]), “Linking workplace health promotion best practices and organizational financial performance: Tracking market performance of companies with highest scores on the HERO Scorecard”, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000631; Fabius, R. et al. (2016[14]), “Tracking the Market performance of companies that integrate a culture of health and safety: An assessment of corporate health achievement award applicants”, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000638.

As shown in Figure 5.2, if both investors and companies value the health and well-being of employees, this can create a virtuous cycle, where the incentive for companies to promote employee health and well-being is amplified. This is because a company that promotes the health and well-being of employees is rewarded not only with a healthier workforce, but also with an increased likelihood of receiving investment. However, one main challenge prevents the unlocking of this virtuous cycle. This is the lack of standardised disclosure mechanisms to ensure information on health outcomes and programmes are comparable across companies. This information is necessary for investors to differentiate companies that implement best practices to promote health and well-being from those that do not. The next sections look at this challenge (Section 5.3) and existing initiatives that seek to address it (Section 5.4).

Source: Authors.

The lack of standardised ESG indicators, metrics3 and ratings4 on health and well-being at work, and the shortage of information on health and well-being of employees are key factors that limit investment in companies that promote the health and well-being of its employees. This section looks at this issue in relation to ESG investment broadly, before looking specifically at the challenges associated with collecting and then disclosing data related to health and well-being at work.

The growing demand for ESG investing is currently hampered by a lack of transparency, international inconsistencies and comparability challenges, and this is a risk that also exists for health and well-being indicators. There are many ESG ratings providers, each using different data sources, methodologies and frameworks to establish ratings (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[17]). This leaves the concept of ESG-promoting companies subject to interpretation rather than objective standards, and can result in companies seeking to show that they are more sustainable than they are in reality, a practice often dubbed as “ESG-washing” or “greenwashing” when used in relation to the environmental pillar. In its review of ESG and climate‑themed equity funds in 2021, InfluenceMap, an independent think tank, found that more than two‑thirds of ESG funds (71%) were not aligned with the global climate targets (InfluenceMap, 2021[18]). There has been less of a “health-washing” issue thus far. This may merely reflect the lack of integration of employee health and well-being considerations within ESG criteria thus far, as there is currently very little collection of standardised information on employee health and well-being that gives a good overview of employer performance. This is, however, an evolving area with a number of initiatives to promote the standardisation of indicators on employee health and well-being, such as the one led by the OECD on the measurement framework for understanding the non-financial performance of firms (Siegerink, Shinwell and Žarnic, 2022[3]), further discussed in Section 5.4.

As shown in Figure 5.3, there are a range of indicators that could provide insight into the health and well-being of employees at the company level, and these fall into three broad categories.

1. Labour market outcomes related to productivity are indicators of work productivity related to employee health and well-being such as sickness absence, working hours and turnover. It may also include indicators on productive ageing, a concept that refers to engaging in productive activities at older ages, applied here in the context of work. These indicators may already be collected by employers in an anonymised form and thus easier to disclose, and are often used as indicators to measure the human capital performance of companies. The weakness with such indicators is that they provide limited insight into employee health.

2. Health and well-being outcomes are direct indicators of health and well-being such as the incidence of accidents and injuries, or self-reported physical and mental health. While these indicators are useful to show the actual health of employees, many companies do not or are unable to collect or process such data on grounds of employee privacy, even in cases where the data are de‑identified5 or anonymised. The collection of such data – if not well-managed – also opens the risk of discrimination of employees by their health status. Even in cases where collection of health data is permissible, it would place an additional burden on companies to collect new data, as companies do not usually collect such data.

3. Indicators related to the implementation of health and well-being programmes by companies show to what extent companies are implementing measures to promote health and well-being in the workplace. The issue with such indicators is the risk of “health-washing” especially if indicators rely heavily or solely on company-reported information. It is therefore important to be able to assess whether programmes implemented are actually implemented, if they are evidence‑based and if they account for and reflect employee experiences and perspectives. This could be for instance to consider not only whether a company reports offering mental health support for workers, but also whether it integrates data on employees’ participation levels and experience as to whether the support they receive is adequate.

Note: Figure developed based on the range of indicators used in disclosure mechanisms which are described in Table 5.1.

A key consideration when collecting or processing any data on employee health and well-being is how to ensure the protection of privacy and prevent discrimination against individuals with health issues. The use of health data is unlikely to be straightforward, and it would be limited to cases where employees voluntarily participate in a workplace health programme and consent to the use of their data. For example, under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the framework for data protection in the European Union, any data related to an individual’s physical or mental health is considered personal and protected data, and cannot be processed unless specific exemptions apply or the employee provides explicit permission (European Union, 2016[19]). Although one of the cases where an exception applies is if processing is necessary “for the purposes of preventive or occupational medicine”, data collection for the purposes of providing insights into the performance of companies promoting employee health would not be covered under such an exemption. Without adequate measures, there is also potential that employers could use employee health data to inform their decisions about whether to retain, dismiss or promote employees, which would result in discrimination (Esmonde, 2021[20]). For instance, in the United States, although the American with Disabilities Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in employment, only one state (Michigan) and several cities prohibit discrimination on the grounds of weight (Eidelson, 2022[21]).

Governments – working with relevant stakeholders such as the finance sector, rating agencies, investors, employers, and employee associations – are addressing the lack of standardised indicators on health and well-being at the workplace by facilitating the disclosure of standardised information and indicators. An overview of initiatives identified that seek to close this gap is presented in Table 5.1, and through this exercise, three types of initiatives were identified. These are:

government-led regulatory reforms to require disclosure on human capital indicators related to health and well-being;

voluntary initiatives (often led by non-governmental stakeholders) that seek to promote disclosure on health and well-being programmes implemented by companies; and

initiatives that seek to standardise indicators and disclosure mechanisms used to assess company performance in promoting health and well-being in the workplace.

A key limitation identified with disclosure mechanisms (whether regulatory or voluntary) is that they primarily target large corporations and are less accessible and available for small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). For instance, SMEs may have weaker incentives to invest in strengthening their non-financial and ESG disclosure given that the initial costs of such disclosure may outweigh the benefits in the short-term. Past OECD evidence has also shown that ESG reporting favours larger companies over SMEs and this bias could also apply to reporting on health and well-being (Boffo and Patalano, 2020[17]). This is reflected in existing initiatives, which tend to primarily target larger corporations, with limited impact on SMEs. The Directive for Non-Financial Reporting of the European Union only applies to the companies with more than 500 employees, while the Corporate Mental Health Benchmark focuses explicitly on the 100 largest UK-limited companies. This also points to the importance of initiatives that seek to standardise indicators and disclosure mechanisms ensuring accessibility to SMEs and levelling the playing field.

|

Name |

Description |

Organisation |

Stage and scale |

Scope |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Category 1. Government-led regulatory reforms to require disclosure |

Workforce Investment Disclosure Act, United States |

Aims to make it mandatory for employers to disclose, information regarding workforce management policies, practices and performance. |

Legislation introduced to the Senate of the United States. |

The bill was introduced to the Senate in 2021. As of May 2022, it has not been discussed or approved. |

Labour market outcomes, health and well-being outcomes, and programme implementation |

|

Non-Financial Reporting Directive, European Union (2013[23]) |

Requires companies to disclose information on their operations and ways of managing social and environmental challenges. Mandatory for specific enterprises |

European Commission |

Applies to large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees, which equates to around 11 700 –companies and groups across the EU. |

Labour market outcomes and health and well-being outcomes. |

|

|

Category 2: voluntary initiatives that seek to promote disclosure on health and well-being |

Health & Productivity Management, Japan (see Box 5.4 for details) |

Provides certification and awards (for 500 SMEs, 500 large enterprises and around 50 for Stock Selection) for companies promoting health in the workplace in Japan. Specific focus on nudging investment to health-promoting companies. |

Led by Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry, with involvement of Tokyo Stock Exchange. |

Launched in 2014, as of 2022, more than 2000 large enterprises and 12 000 SMEs had been certified. The next stage is to include the health of employees in supply chains in company assessment. |

Labour market outcomes related to health and well-being, health and well-being outcomes, and programme implementation |

|

Workforce Disclosure Initiative, United Kingdom (ShareAction, 2022[24]) |

Performs an annual survey for companies interested in reporting on transparency and accountability related to workforce Issues |

Led by a charity (ShareAction) and partially funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office of the United Kingdom. |

Launched in 2017. The survey received responses from 140 companies in 2020 and 178 responses in 2021. |

Primarily programme implementation (Some use of health outcomes and labour market outcomes) |

|

|

Corporate Mental Health Benchmark UK 100, United Kingdom (CCLA, 2022[25]) |

Uses published information to assess the mental health promotion practice of companies. |

CCLA, charity fund manager in the United Kingdom |

The first edition, published in 2022, includes the 100 biggest companies of the UK |

Health and well-being outcomes and programme implementation |

|

|

WELL Building Standard Certification (IWBI, 2022[26]) |

It proposes counseling, support and certification for improving health, safety, equity and performance outcomes in the workplace. |

International WELL Building Institute, corporation |

It aims to work with companies of any size. The standard was launched in 2004 and has reached about 2000 organisations. |

Labour market outcomes, health and well-being outcomes, and programme implementation |

|

|

Category 3: Initiatives that seek to standardise indicators used to assess company performance in promoting health and well-being in the workplace |

Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark Standard (GRESB, 2022[27]) |

GRESB standards measure performance of individual assets and portfolios within the Real State and Infrastructure industries. GRESB collects data and provides business intelligence. |

Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark, composed of an independent foundation and a for profit corporation. |

Health and Well-being indicators were integrated into the Stakeholder Engagement aspect, included in 2018. |

Programme implementation. |

|

Global Reporting Initiative and Culture of Health for Business (COH4B) (GRI, 2020[28]) |

GRI Standard 403 provides guidelines on disclosure on occupational safety and health, including on worker health promotion. GRI is also working to contribute to a common framework for businesses to report on their culture of health in a partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. |

Global Reporting Initiative, non-governmental standard-setting organisation. |

Around three‑quarters of the G250 – the largest companies worldwide by revenue – use GRI. Standard 403 was first published in 2018 |

Labour market outcomes, health and well-being outcomes, and programme implementation |

|

|

WISE framework for “Scope 1” social performance. |

Proposes a conceptual framework and set of indicators to measure the impact of business action on the well-being of their employees. |

OECD |

Released in 2022. The framework is aspirational and efforts will be made to continue to address measurement gaps. |

Health and well-being outcomes. |

|

|

Sustainability and Accountability Standards Board Standards (SASB, 2020[29]) |

A set of standards designed for specific industries rather than to assess particular topics. Existing standards incorporate employee health and safety considerations but with a focus on preventing injuries, fatalities and illness. |

Value Reporting Foundation, global non-profit organisation. |

Standards were first published in 2015 and as of 2021,1325 companies worldwide reported using SASB standards. |

Health and well-being outcomes |

|

|

ISO 45 000 family of standards |

This group of standards aims to enable any company to put in place occupational health and safety management systems. |

International Standards Organization, standard-setting organisation |

These standards initially focused on occupational safety and health alone, but the latest standard (ISO 450 003) looks more broadly at mental health and well-being at work. |

Programme implementation |

Note: Information collected and categorisation of initiatives by authors.

Government-led reforms can make it mandatory for companies to disclose certain information related to health and well-being. Such initiatives are, however, in their infancy or very limited in coverage, which may reflect a reluctance to enforce disclosure and the administrative work this entails upon companies. In the United States, the Workforce Investment Disclosure Act proposal introduced to the Senate in 2021 would – if passed – make it compulsory for publicly traded companies to disclose human capital metrics, including many indicators related to workforce health (United States Congress, 2021[22]). The information proposed for disclosure not only includes labour market outcomes related to health and well-being (such as retention rate; lost time due to injuries, illness and death; and leave entitlements), it also proposes disclosure of information on “engagement, productivity and mental well-being of employees” and “total expenditure on workplace health, safety and well-being programmes.” By comparison, the Directive for Non-Financial Reporting of the European Union already requires large companies to disclose information on their practices to manage social and environmental challenges, although the focus on employee health is very limited, and it merely requires a non-financial statement with no requirements to disclose specific information (European Union, 2013[23]).

There are a wide range of voluntary disclosure initiatives, which invite companies to disclose information on health and well-being. Many of these voluntary initiatives are embedded in award and certification schemes, which are discussed in detail in Chapter 4. Voluntary initiatives are typically led by, or involve, investors and asset management companies. A notable example is the Workforce Disclosure Initiative, which is led by ShareAction, a charity group and financially supported by the UK Government, and invites companies to disclose information on what measures they are taking to address workforce issues (Box 5.3). The Corporate Mental Health UK 100 Benchmark, led by CCLA, a large charity fund manager, differs in the mechanisms it uses, as instead of asking for disclosure, it uses publicly available information to assess the mental health promotion practices of companies (CCLA, 2022[25]). Meanwhile, the Health and Productivity Management Programme in Japan, which is described in Box 5.4, also involves the Tokyo Stock Exchange, but is led by the government.

The Workforce Disclosure Initiative (WDI) was created to improve the transparency and accountability on workforce issues within the corporate sector. Spearheaded by the ShareAction, a charity group, WDI is partially funded by the UK Government’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. WDI invites companies to disclose information on what measures they are taking to address workforce issues in ten areas of management – “governance, risk assessment, contractual status and remuneration, gender diversity, stability, training, well-being and rights issues” – including in their supply chains (ShareAction, 2022[24]). Within the area of well-being, information requested from companies is primarily based on programme implementation (see data analysis in Chapter 4). For instance, disclosing companies are asked about how they identify and manage health and safety risks; whether they provide a health and well-being plan; and what measures they are taking to mitigate the impact of COVID‑19 on employee health. There are also some questions related to outcomes such as the number of cases of work-related injuries and ill-health, although these are limited to issues around the prevention of accidents, illnesses and deaths. WDI has been collecting information on workforce measures annually since 2017, with the number of companies disclosing information increasing from 34 companies to 173 worldwide companies over the course of five years. While WDI originated in the United Kingdom, it has expanded in recent years including through partnerships in Canada and Australia.

The Health & Productivity Management Programme, which is described in Box 4.8 in Chapter 4, is an example of a certification and award scheme launched in 2014 by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) that also includes a heavy emphasis on facilitating investment in large companies that promote the health and well-being of their employees. To participate in this voluntary scheme, large companies are required to respond to a questionnaire annually, which acts to promote standardisation of the information reported by companies. The questions cover a vast range of areas including labour market outcomes related to productivity (e.g. indicators for absenteeism and presenteeism), health and well-being outcomes (e.g. prevalence of smoking and exercise habits since financial year 2016) and programme implementation (e.g. measures taken to increase literacy, promote physical activity and support smoking cessation). The uptake and results of health and stress checks that employers are required to offer in Japan by law which are described in Chapter 4, are also included in the survey.

METI recently began to publicly release the information reported by large corporations – with their approval – in order to increase transparency, while also giving investors an insight into which companies may be taking greater steps towards promoting the health and well-being of their employees. A total of 2000 companies agreed to disclosure of their evaluation sheets for 2021 based on the H&PM survey, which includes 634 listed companies and around 70% of the largest publicly owned companies in Japan (Nikkei 225) (2022[30]). The results for each of these companies are now available on the METI website.

METI also awards specific companies for the Health and Productivity Stock Selection. This is an award given jointly by METI and the Tokyo Stock Exchange for a select number of employers that score in the top 20% of H&PM screened by METI, but are also considered financially profitable.6 The idea behind this is to signpost investment towards companies with Health and Productivity Stock Selection. 50 enterprises were announced as having been chosen for Stock Selection in 2022 (based on financial year 2021) (2022[31]). Although no causal relationship can be assumed as described in Section 5.2, companies selected for Stock Selection seem to perform well in the Tokyo Stock Exchange. As shown in Figure 5.4, between 2011‑21, the stock value of the group of companies selected for the Health and Productivity Stock Selection in 2021 outperformed the average of companies comprising the Tokyo Stock Exchange.

Note: The index was created using the companies’ closing price on the first day of each month, using 1 September 2011 as the baseline (1.0). TOPIX refers to the average stock price of the companies comprising the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Four companies that had no baseline data, such as newly listed companies are excluded.

Source: Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry of Japan (2021[15]), Enhancing Health and Productivity Management Programme [Kenkō keiei no suishin ni tsuite].

The ministry has also collected information from major institutional investors in Japan on what information they would like to be able to have access to better differentiate companies that promote the health and well-being of companies and those that do not. In a 2021 survey covering 16 major institutional investors, more than two‑thirds of surveyed investors stated that overtime hours (88%), worker engagement (88%) and turnover rates (81%) should be disclosed by companies when evaluating health management. Half or more of the surveyed investors also stated that health literacy of employees (56%), the execution rate of the stress check (56%) and presenteeism and absenteeism rates (both 50%) should also be disclosed (Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry, 2021[32]). The collection of such information could allow for the fine‑tuning and adjustment of the questions included in the H&PM survey in future years.

The third category of initiatives are those that seek to standardise and harmonise practices across countries and companies on disclosure mechanisms of company performance. Organisations such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) – which sets standards used by 75% of the world’s largest companies in their ESG reporting – play a sizable role in this area given their global reach. ISO offers a collection of domain specific standards, whereas GRI proposes universal and topic specific standards (KPMG, 2020[33]). While these organisations have in the past assumed a focus on accident and injury prevention, they are now bridging this gap and introducing aspects of health promotion. For instance, ISO developed a new standard in 2021 – ISO 45 003 – which focuses on the management of psychosocial risks in the workplace (ISO, 2021[34]), while GRI integrates the expectation that companies implement voluntary health promotion programmes within its occupational health and safety reporting guidelines – GRI 403 (GRI, 2018[35]). GRI has also partnered with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in order to align GRI 403 with a complementary framework on Culture of Health for Business (GRI, 2020[28]). The OECD Centre on Well-being, Inclusion, Sustainability and Equal Opportunity (WISE) is also developing a framework to assess the non-financial performance of companies, and this framework includes components related to health and well-being outcomes in the workplace (Siegerink, Shinwell and Žarnic, 2022[3]).

By encouraging the disclosure of standardised information and indicators on health and well-being at the workplace, governments can steer investors to invest in health-promoting companies and thus activate the virtuous cycle of health and productivity benefiting to both employees and employers. Another, different mechanism to finance health promotion at work, social impact bonds, is discussed in Section 5.5.

Public-private partnership financing mechanisms, such as social impact bonds or health impact bonds, also hold potential to support government expenditure to promote health and well-being at work. Social impact bonds are issued by governments to seek financing for projects with positive social outcomes (such as access to education or improving food security, but also workforce development). While social impact bonds are referred to as “bonds”, they are not actual bonds, but rather represent contracts based on future social outcomes (OECD, 2019[36]). If social outcomes improve, investors receive their initial investment plus a financial return, measured as a fraction of the public sector saving. As the terms of payment depends on the successful delivery of outcomes, social impact bonds are considered an example of a pay-for-success approach. When the outcomes relate to health and social sector, social impact bonds are called health impact bonds. While evidence is still emerging, health impact bonds can help to finance prevention of chronic conditions and return-to-work programmes targeted at high-risk populations who face socio-economic disadvantages (see Box 5.5).

The first social impact bond for health was launched in the United States in 2013, when the California Endowment, a private health foundation, provided funding of USD 600 000 over two years to Social Finance, Inc. and Collective Health to implement a project to reduce chronic asthma in low-income children residing in Fresno, California (Social Finance, 2013[37]). Evidence from the first year of the pilot found that rates of asthma-related hospital visits declined, and an analysis estimated that for every one dollar spent, almost four dollars (USD 3.63) was saved in health care costs.

According to the Impact Bond Global Database, in early 2022, there are 138 impact bonds in 26 countries worldwide, with USD 441 million capital raised and benefitting to more than 1.7 million people (Social Finance, 2022[38]). The database highlights 22 examples of health impact bonds, and two examples related to chronic diseases prevention and employment are described below.

In New Zealand, a mental health and employment social impact bond was launched in 2017 (for a duration of 5 years), with a capital of NZD 1.5 million (USD 1 million). The programme aims to help 1 700 people diagnosed with a mental health condition to return to work in six Auckland suburbs (Social Finance, 2022[38]; New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2019[39]). It provides a holistic employment service to jobseekers, including pre‑employment screening and assessment, preparation for work, job matching and placement, and post-placement support. The client is the New Zealand Ministry of Social Development. APM Workcare Ltd is the service provider of vocational rehabilitation and disability services, and also one of the investors. The three other investors are a private philanthropic fund, Wilberforce Foundation, a health care company, Janssen, and an investment fund, Prospect Investment Management Ltd. The programme is still ongoing, and evaluation is not yet available. The two metrics by which success will be measured are the percentage of people that enter employment, and the extent to which employment is sustained. Potential benefit of the programme include the direct benefits from the cessation of jobseeker benefit payment and expected income tax gain from work, that will serve to reimburse the investors.

In the Netherlands, the Cancer and Work Health Impact Bond was launched in 2017 (for a duration of 3 years), with a capital of EUR 640 000 (USD 758 000) (Social Finance, 2022[38]; ABN AMRO, 2018[40]). The programme aims to help 140 cancer survivors return to work, providing a newly developed intensive rehabilitation programme over 2 years. The intervention hinges on exercise, both physically and mentally, at home and at work, and enrols coaches to guide participants through the programme. The key players are: the insurer De Amersfoortse (the client), the occupational health and safety service ArboNed and the rehabilitation agency Re‑turn (the operational practitioners), and the ABN AMRO Social Impact Fund and Start Foundation (the investors). The investors offered the finance for the rehabilitation programme and they will not receive any return until the envisaged results – evaluated based on whether participants have returned to work – have been reached. The client will then pay the investors based on the savings it has achieved on policies for absenteeism insurance. Evaluation on social and financial performance is not yet available.

The rising interest among investors in human capital and ESG criteria provides an opportunity to steer investment towards companies that promote the health and well-being of employees. This presents the opportunity of a virtuous cycle where companies that promote the health and well-being of employees are rewarded both with a healthier workforce and with investment. The challenge that remains to unlock this virtuous cycle is to develop and agree on a set of standardised disclosure mechanisms and indicators that allow investors to differentiate between companies across different countries.

[40] ABN AMRO (2018), Cancer & Work Health Impact Bond - ABN AMRO Bank, https://www.abnamro.com/en/news/cancer-and-work-health-impact-bond (accessed on 20 April 2022).

[11] BlackRock (2022), Our approach to engagement on human capital management, BlackRock, https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/publication/blk-commentary-engagement-on-human-capital.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

[17] Boffo, R. and R. Patalano (2020), “ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges”, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf.

[9] Botev, J. et al. (2019), “A new macroeconomic measure of human capital with strong empirical links to productivity”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1575, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d12d7305-en.

[7] Brand Finance (2021), Global Intangible Finance Tracker 2021, https://brandirectory.com/download-report/brand-finance-gift-2021.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2022).

[25] CCLA (2022), CCLA Corporate Mental Health Benchmark UK 100 Report 2022, https://www.ccla.co.uk/sites/default/files/2022_Benchmark_UK%20_100_Report.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2022).

[5] Centene (2021), Environmental, Social, Health and Governance Report the Community, https://www.centene.com/content/dam/centenedotcom/investor_docs/Centene_2021_ESHG_Report.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2022).

[21] Eidelson, J. (2022), “Yes, You Can Still Be Fired for Being Fat”, Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-03-15/weight-discrimination-remains-legal-in-most-of-the-u-s (accessed on 14 June 2022).

[20] Esmonde, K. (2021), “‘From fat and frazzled to fit and happy’: governing the unhealthy employee through quantification and wearable technologies”, Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, Vol. 13/1, pp. 113-127, https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1836510.

[19] European Union (2016), “Regulation 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC”, Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. 59, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2016:119:TOC (accessed on 6 April 2022).

[23] European Union (2013), “Directive 2013/34/EU of the European Parliament on the annual financial statements”, Official Journal of the European Union, Vol. 56, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2013.182.01.0019.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2013%3A182%3ATOC (accessed on 6 June 2022).

[14] Fabius, R. et al. (2016), “Tracking the Market performance of companies that integrate a culture of health and safety: An assessment of corporate health achievement award applicants”, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 58/1, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000638.

[12] Goetzel, R. et al. (2016), “The Stock Performance of C. Everett Koop Award Winners Compared With the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index”, Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, Vol. 58/1, pp. 9-15, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000632.

[27] GRESB (2022), Real State Assessment, https://documents.gresb.com/generated_files/real_estate/2022/real_estate/assessment/complete.html (accessed on 9 June 2022).

[28] GRI (2020), Culture of Health for Business, https://www.globalreporting.org/public-policy-partnerships/strategic-partners-programs/culture-of-health-for-business/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

[35] GRI (2018), GRI 403: Occupational health and safety, https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/media/1910/gri-403-occupational-health-and-safety-2018.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2022).

[13] Grossmeier, J. et al. (2016), “Linking workplace health promotion best practices and organizational financial performance: Tracking market performance of companies with highest scores on the HERO Scorecard”, Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 58/1, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000631.

[18] InfluenceMap (2021), Climate Funds: Are They Paris Aligned? An analysis of ESG and climate-themed equity funds, https://influencemap.org/report/Climate-Funds-Are-They-Paris-Aligned-3eb83347267949847084306dae01c7b0 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

[4] Institute of Health Equity (2022), The Business of Health Equity: The Marmot Review for Industry - IHE, Institute of Health Equity, https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-business-of-health-equity-the-marmot-review-for-industry (accessed on 9 April 2022).

[34] ISO (2021), ISO 45003:2021(en), Occupational health and safety management — Psychological health and safety at work — Guidelines for managing psychosocial risks, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:45003:ed-1:v1:en (accessed on 9 June 2022).

[26] IWBI (2022), WELL ESG Reporting Guide.

[6] Johnson & Johnson (2022), Employee Health, Safety and Wellness, https://healthforhumanityreport.jnj.com/our-employees/employee-health-safety-wellness (accessed on 10 June 2022).

[33] KPMG (2020), The time has come - the KPMG Survey of Sustainability Reporting 2020, https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2020/11/the-time-has-come.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2022).

[30] Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry (2022), Evaluation Sheets Published for 2,000 Enterprises Under the FY2021 Survey on Health and Productivity Management, https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2022/0315_002.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

[31] Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry (2022), Fifty Enterprises Selected under the 2022 Health & Productivity Stock Selection, https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2022/0309_001.html (accessed on 15 June 2022).

[32] Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry (2021), Presentation by METI on progress in 2021 and long-term direction, 4th Meeting of the Health Investment Working Group [Dai 4-kai kenkō tōshi WG: kon-nendo no shincoku to chū-chōki-tekina hōkō-sei], https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/mono_info_service/kenko_iryo/kenko_toshi/pdf/004_02_00.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

[15] Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry of Japan (2021), Enhancing Health and Productivity Management Programme - October 2021 update [Kenkō keiei no suishin ni tsuite], https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/downloadfiles/211006_kenkokeiei_gaiyo.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2022).

[39] New Zealand Ministry of Health (2019), Social Bonds – Progress to date.

[8] Ocean Tomo (2021), Intangible Asset Market Value Study, https://www.oceantomo.com/intangible-asset-market-value-study/ (accessed on 27 May 2022).

[16] O’Donnell, M. (2016), Is There a Link between Stock Market Price Growth and Having a Great Employee Wellness Program? Maybe, https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000634.

[41] OECD (2022), Report on the Implementation of the OECD Recommendation on Health Data Governance, OECD, Paris, https://one.oecd.org/document/C(2022)25/en/pdf.

[2] OECD (ed.) (2021), ESG Investing and Climate Transition: Market Practices, Issues and Policy Considerations, https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-investing-and-climate-transition-market-practices-issues-and-policy-considerations.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

[10] OECD (2020), How’s Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9870c393-en.

[1] OECD (2020), OECD Business and Finance Outlook 2020: Sustainable and Resilient Finance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eb61fd29-en.

[36] OECD (2019), Social Impact Investment 2019: The Impact Imperative for Sustainable Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311299-en.

[29] SASB (2020), SASB Human Capital Bulletin.

[24] ShareAction (2022), Workforce Disclosure Initiative: FAQs, https://shareaction.org/workforce-disclosure-initiative/workforce-disclosure-initiative-faqs (accessed on 9 June 2022).

[3] Siegerink, V., M. Shinwell and Ž. Žarnic (2022), “Measuring the non-financial performance of firms through the lens of the OECD Well-being Framework: A common measurement framework for “Scope 1” Social performance”, OECD Papers on Well-being and Inequalities, No. 03, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/28850c7f-en.

[38] Social Finance (2022), Impact Bond Global Database, https://sibdatabase.socialfinance.org.uk/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

[37] Social Finance (2013), The California Endowment Awards Grant to Social Finance and Collective Health, https://nchh.org/resource-library/pdfs/fresno_asthma_demonstration_project_press_release.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

[22] United States Congress (2021), S. 1815 - Workforce Investment 5 Disclosure Act of 2021, https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/s1815/BILLS-117s1815is.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

← 1. The Global Finance Tracker is an annual review which highlights important trends in the value of companies in the form of their intangible assets. It is conducted by Brand Finance, a consultancy firm that estimates to the value of brands.

← 2. Ocean Tomo is a company that provides a range of financial services related to intellectual property and other intangible assets to client companies, governments and institutional investor’s.

← 3. e.g. data and standards used for assessing, comparing, tracking performance of companies relative to ESG factors.

← 4. Including scoring and ranking.

← 5. De‑identification refers to the “process by which a set of a personal health data is altered, so that the resulting information cannot be readily associated with particular individuals.” (OECD, 2022[41])

← 6. The requirement is that the return on equity (RoE) is at least 0% or in other words not negative.