Efficient and equitable resourcing of schools is the foundation for quality education and marks a key challenge for education systems. Beyond a sufficient level of funding, effective resourcing requires adequate governance arrangements and well-designed allocation mechanisms for education funding. This chapter examines whole-system approaches to managing the complexity of school funding governance in the context of fiscal decentralisation and growing school autonomy. It also presents a series of questions that need to be addressed when designing school funding allocation mechanisms, highlighting the potential of needs-based funding formulas. Finally, the chapter underlines the importance of adequate regulatory frameworks for the public funding of private providers to mitigate unintended consequences and harmful effects on equity.

Value for Money in School Education

3. Governing and distributing school funding: Effectively connecting resources and learning

Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a surge of education expenditure among OECD countries: About two-thirds of governments raised their budget, with the remainder maintaining spending at a constant level (OECD, 2021[1]). However, the lagging economic recovery and new budget priorities deriving from the consequences of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine confronts governments across the OECD with difficult budgetary choices. Governments must allocate scare public resources between and within different policy fields, including education, health and welfare programmes, to support the economic recovery and balance short- and long-term economic and social goals. While investment in education plays a crucial role in the economic and social recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, ensuring an efficient and equitable use of education resources becomes a clear policy priority.

The overall levels of school funding clearly matter for the quality of teaching and learning, as has been underlined by recent quasi-experimental research on school spending and student outcomes in the United States (Jackson, 2018[2]). Overall levels of spending arguably also determine the ability of school systems to respond to new challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, school systems that lack quality teachers, school leaders and support staff as well as adequate educational facilities and materials will struggle to promote quality education (OECD, 2017[3]). Insufficient investments in education staff reduces the attractiveness of a career in schools and makes it harder to recruit and retain qualified professionals. Resource constraints, such as a lack of quality staff, may also hinder schools’ capacity for pedagogical innovation (OECD, 2019[4]). Similarly, although investments in physical resources are rarely the most effective way to improve students’ learning, inadequate facilities that fail to support teaching and learning can thwart a school system’s pursuit of excellence (OECD, 2018[5]; Gunter and Shao, 2016[6]).

Overall levels of spending matter, but beyond a certain level of investment, the governance and distribution of school funding is at least as important to promote student learning.

Beyond a certain level of investment, however, the governance, distribution and effective use of school funding is at least as important to promote student learning at its overall amount. The governance of school funding concerns the different authorities involved in raising, managing and allocating resources and the relationship between these authorities. In many countries, the governance of school funding is characterised by increasing financial decentralisation, enhanced school autonomy and growing public funding of private school providers. While these trends come with new challenges, they can provide opportunities for the more effective and equitable use of funds, insofar as they are accompanied by adequate institutional arrangements. Further, the design of effective mechanisms to allocate and distribute funding – across levels of administration or to individual schools – is also essential to ensure that school funding advances student learning, equity and related policy objectives (OECD, 2017[3]).

This chapter describes practices and procedures involved in effectively governing and distributing school funding and analyses the key challenges involved. The chapter is organised around five themes:

First, this chapter reviews the distribution of responsibilities for raising and allocating funding for school education. This includes the role and design of fiscal transfers to equalise spending capacity across jurisdictions as well as the use of monitoring and evaluation to ensure transparency in the flow of resources.

Second, this chapter explores the importance of whole-system approaches to address complexity challenges in school funding governance, which can give rise to inefficiency and a lack of transparency. Effective school funding governance requires a clear delineation of responsibilities for school funding, adequate co-ordination mechanisms and systematic capacity building.

Third, this chapter analyses the trend towards giving schools greater autonomy in managing their own budgets, and the conditions that need to be in place for schools to use this autonomy in a constructive way. This includes competent education leadership, technical support and accountability, as well as adequate institutional frameworks to address the risk of increased inequities across schools.

Fourth, the note reviews the public funding of private providers as part of broader policies to promote parental choice and education quality, and the design of adequate regulatory frameworks to counteract potential adverse effects of such policies on equity.

Finally, the note discusses a series of fundamental questions that need to be addressed when designing a funding allocation model to ensure that resources are distributed in a transparent and predictable way. This includes the balance between regular and targeted funding, the methods used to determine the size of funding allocations as well as the implementation of new funding allocation mechanisms. This theme covers country approaches for distributing funding for current and capital expenditures. For current expenditures, the analysis also focuses on the design of funding formulas that can be adjusted to support policy objectives aiming for greater efficiency, equity and quality.

Distributing responsibilities for revenue raising and spending in school education

The majority of initial funding for school education originates at the central level, but in many countries sub-central authorities are important actors in school funding

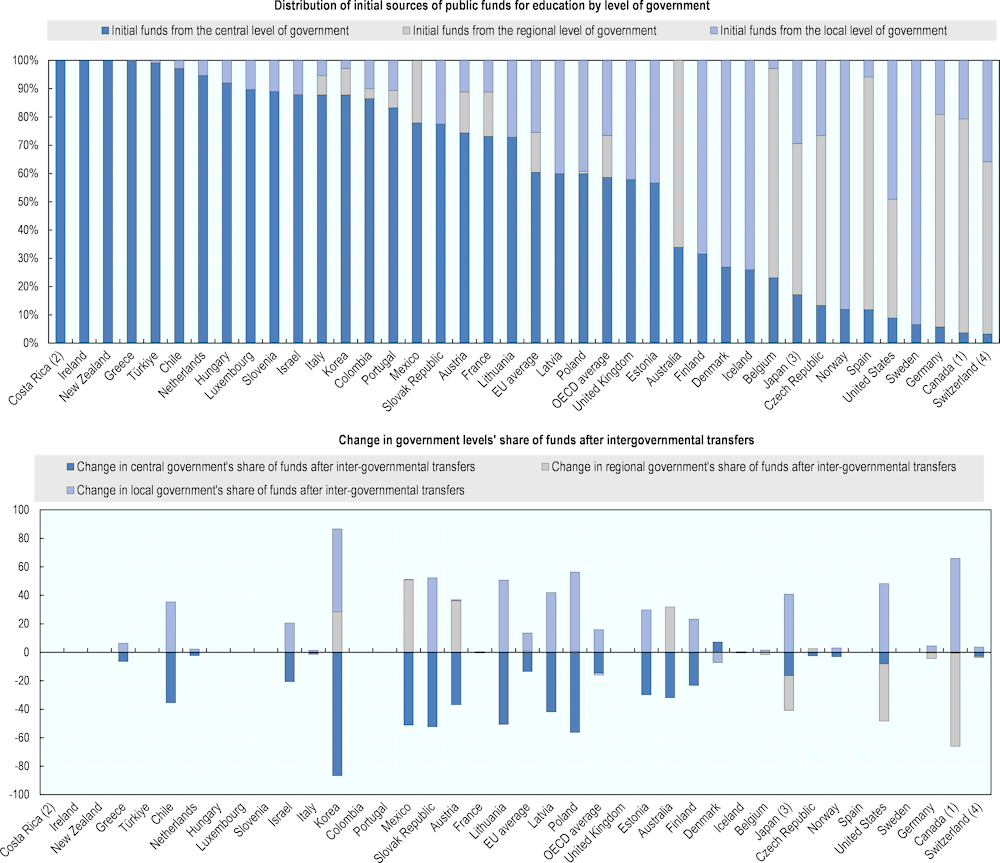

The majority of initial funding for school education is raised at the level of central governments, mainly through tax revenues. However, sub-central authorities typically complement central funding from their own revenues generated for instance through local taxes or user fees (OECD, 2017[3]).1 In 2019, on average across OECD countries, 59% of the public funds for non-tertiary education came from the central government prior to intergovernmental transfers (Figure 3.1) (OECD, 2022[7]). Local authorities contributed another 27% of initial funding, and regional governments 15% (OECD, 2022[7])2.

Figure 3.1. Distribution of initial sources of public funds for education and change in government levels' share of funds after intergovernmental transfers (2019)

Note: Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of initial sources of funds from the central level of government.

1 Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

2 Year of reference 2020.

3 Data do not cover day care centres and integrated centres for early childhood education.

4 Year of reference 2018.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2022[7]), Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/3197152b-en, Table C4.2.

Decentralised school funding arrangements require an alignment of revenue raising and spending powers and a careful balancing of accountability and trust between actors

In many countries, sub-central authorities have emerged as important actors in the allocation and management of school funding (OECD, 2017[3]). While fiscal decentralisation offers the potential for sub‑central governments to adapt school funding decisions to local needs, there are also trade-offs involved (e.g. loss of economies of scale) (OECD, 2021[8]). Hence, decentralised approaches to school funding need to be designed in ways that ensure sub-central authorities have both adequate resources to meet the needs of their students and the capacity to fulfil their funding responsibilities. This requires efforts among different levels of government to arrive at a shared assessment of funding needs as well as a careful balancing of accountability and trust between levels of governance (OECD, 2017[3]). Even if funding responsibilities are decentralised, the central government often remains responsible for ensuring high quality, efficient and equitable education nationally. Therefore, it may have an interest in controlling sub‑central spending and performance. Sub-central authorities, on the other hand, may perceive such central monitoring as interference in their areas of responsibility (Schaeffer and Yilmaz, 2008[9]).

Responsibilities for raising and spending school funding need to be well aligned to encourage an efficient use of fiscal resources (OECD, 2017[3]). The dispersion of responsibilities for education financing and spending across different levels of government might result in a lack of incentives for a fair allocation of resources on the one hand and responsible use of resources on the other (OECD, 2017[3]). For instance, where responsibilities for raising funds to cover the teacher payroll and for deciding on teacher employment are misaligned, incentives to ensure efficient staffing levels in line with changing enrolment are reduced (OECD, 2019[4]).

School systems that grant sub-central authorities large spending powers might address this tension by increasing sub-central responsibilities for revenue raising and fiscal autonomy at the margin. For example, the Nordic countries typically give local governments substantial control over personal income tax rates, a practice that has also been picked up by some Central and Eastern European countries. Reliance on own tax revenues may support sub-central authorities in determining public service levels in line with local preferences, help mobilise additional resources for school education, and discourage overspending by creating a hard budget constraint (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2021[8]).

Fiscal decentralisation entails risks of creating inequalities in available resources across localities, which requires adequate fiscal equalisation mechanisms

At the same time, raising the proportion of own revenue in sub-central education budgets also entails the risk of creating inequities in the availability of funding for schools across different localities. Typically, wealthier jurisdictions will be in a better position to raise their own revenues and to provide adequate funding per student. In the United States, for example, prior to the 1970s the vast majority of resources spent on compulsory schooling was raised at the local level, primarily through local property taxes. Since the local property tax base is generally higher in areas with higher home values, the heavy reliance on local financing contributed to higher per-student spending in wealthier jurisdictions (Jackson, Johnson and Persico, 2015[10]).

Schemes that transfer fiscal resources from the central government to sub-central authorities (vertical transfers) or between sub-central governments (horizontal transfers) can help ensure that all jurisdictions have the necessary resources to provide similar services at similar tax levels, and to provide equal opportunities for their students. Fiscal transfers can also help address gaps in sub-central revenues and expenditures. Indeed, sub-central spending responsibilities have grown much faster than their tax collection responsibilities, creating fiscal imbalances (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2021[8]). Once transfers to sub-central levels of government are accounted for, the share of central funding for non-tertiary education falls from 59% to 44%, while the share of local funds rises as a result, from 26% to 42% (Figure 3.1. above). In Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland and the Slovak Republic, the difference in funding power before and after transfers represents more than 50 percentage points (OECD, 2021[11]).

The OECD School Resources Review provides examples from different countries that have introduced fiscal transfer and equalisation mechanisms alongside reforms devolving funding responsibilities to sub‑central governments (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Fiscal transfer and equalisation mechanisms as part of education finance decentralisation reforms in select countries

When Brazil decentralised its education finance system in the mid-1990s, it created the Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Schools and the Valorisation of the Teaching Profession (Fundo para Manutenção e Desenvolvimento do Ensino Fundamental e Valorização do Magistério, FUNDEF) to reduce the large regional inequalities in per-student spending. State and municipal governments were required to transfer a proportion of their tax revenue to FUNDEF, which was then redistributed to state and municipal governments that could not meet specified minimum levels of per-student expenditure. Although FUNDEF did not prevent wealthier regions from increasing their overall expenditure at a higher rate than poorer regions, it did play a highly redistributive role and increased both the absolute level of spending and the predictability of transfers. In 2007, FUNDEF was revised and transformed into the Maintenance and Development Fund for Basic Education (Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica, FUNDEB) and, in 2021, relaunched with a new mandate and as a permanent feature of the school funding system.

Colombia’s school system is relatively decentralised: The regional and local authorities that serve as education providers are mostly funded from the central budget but can contribute their own resources. The main financing mechanism is the General System of Transfers (Sistema General de Participaciones, SGP) which allocates revenues for different public services among the central and sub-central governments. The distribution of SGP resources is specific to each sector. In education, the SGP allocates a specific budget share for every student to the sub-central governments. These shares are determined based on different criteria related to equity and efficiency, the geographic area (urban-rural) and based on the number of students enrolled the previous year. Additional funding is provided for specific student characteristics (e.g. students with special education needs). In addition, the SGP allocates resources for quality improvement in schools or the financing of pensions and healthcare in education.

In Denmark, municipalities are the main providers of public services, including primary and lower secondary education. Municipal spending is primarily financed through central government grants and local taxes. The total volume of the grants is decided through annual negotiations between the central and local governments. The grant level for a given municipality is primarily based on the size of its population. In addition, there is a fiscal equalisation scheme which takes into account both tax revenues and expenditure needs depending on the age composition and socio‑economic structure in the municipalities. Thus, the fiscal equalisation scheme seeks to ensure a similar level of service provision across municipalities by adjusting local budgets to the size and composition of local populations.

In Poland, the decentralisation of education was part of the wider national decentralisation process initiated in 1990. The main transfer of funding from the central to local budgets (the “general subvention”) comprises several components that are separately calculated. The education component is calculated based on student numbers and a range of coefficients reflecting cost differences in educating different groups of students. The equalisation component is based on a formula and provides poorer jurisdictions with up to 90% of the discrepancy in average per-capita revenues compared to local governments with similar student populations.

Source: OECD (2017[3]), The Funding of School Education: Connecting Resources and Learning, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276147-en; Radinger et al. (2018[12]), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Colombia 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303751-en.

The nature of fiscal transfers influences sub-central autonomy for and central steering of spending in school education

The conditions attached to intergovernmental transfer can have considerable influence on how the money is spent. Grants may be tied to a particular purpose (i.e. earmarked grants), allocated to a certain type of expenditure more generally (i.e. a block grant), or transferred for general use for the public sector (i.e. lump sum grants). The type of conditions attached to a grant will influence the actual balance of responsibilities between levels of governance and determine the scope of decision making for sub-central authorities as well as the steering power of the central level (OECD, 2017[3]).

Lump sum grants give sub-central authorities the greatest degree of freedom by allowing them full discretion over the proportion of funding allocated to school education. Lump sum funding may, however, make it more difficult to shield local education budgets from pressures arising from the funding needs of other public services provided at a local level. Block grants are allocated on the condition that they are spent on a certain type of expenditure (e.g. current spending in pre-school and primary education). They still leave a high degree of discretion to sub-central authorities, for example, over the share to spend on salaries vs. operational costs. Earmarked grants impose greater restrictions and offer greater central control over local spending and policy by requiring grants to be used for a specific purpose or item of expenditure (OECD, 2017[3]). Funding can, for example, be earmarked to ensure a minimum level of expenditure on particular staff types, education materials, or a specific student group (OECD, 2018[5]; OECD, 2019[4])

Some countries, like Denmark and Sweden, have increased the use of targeted subsidies over the years as a means to steer municipal funding allocation (OECD, 2017[3]). However, across the public sector and internationally, a slight trend from earmarked grants to non-earmarked grants could be observed, combined with steering through regulations and a focus on outcomes and performance (Blöchliger and Kim, 2016[13]; OECD, 2021[8]).

The design of fiscal transfer mechanisms needs to address a range of challenges

While fiscal transfers play an important role in providing sub-central revenue for service provision and equalising sub-central revenue levels, they come with a set of challenges (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2021[8]). First, fiscal transfers from central governments may exacerbate fluctuations in sub-central revenues and complicate medium‑term planning as they are often pro-cyclical (i.e. likely to increase in times of strong growth and decrease in times of crisis). Second, if grants are adjusted on the basis of local revenues, sub-central authorities might be discouraged from raising their own resources, reducing the total mobilisation of resources for education. This incentive effect is particularly pronounced for wealthy municipalities which might need to raise significant additional revenues in order to marginally increase their spending on local public goods (Hoxby, 1998[14]). Third, a high reliance on central grants may encourage overspending in the hope that it will be compensated with additional grants, and thereby increase deficits and debt. Finally, the determination of grant levels and calculation methods themselves may also be problematic (Blöchliger and Kim, 2016[13]; Busemeyer, 2008[15]). In the design of fiscal transfer mechanisms, it is therefore important to strike a balance between ensuring stakeholder involvement and limiting the risk of rent-seeking and political distortions (e.g. through independent agencies or two-stage budget procedures) (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2021[8]).

The COVID‑19 pandemic has introduced a particular set of challenges for equalisation systems that are not well-adapted to respond to emerging, short-term crises. Where funds for equalising transfers are tied to dedicated revenue streams or capped at a certain growth rate, revenues may shrink as a result of the pandemic, thus lowering transfers. Moreover, it is common for countries to link equalising transfers to lagged indicators of fiscal capacity or to a moving average .Thus, intergovernmental transfers might further drive inequalities between localities in times of crises when the need for support might deviate from previous patterns (OECD, 2021[8]).

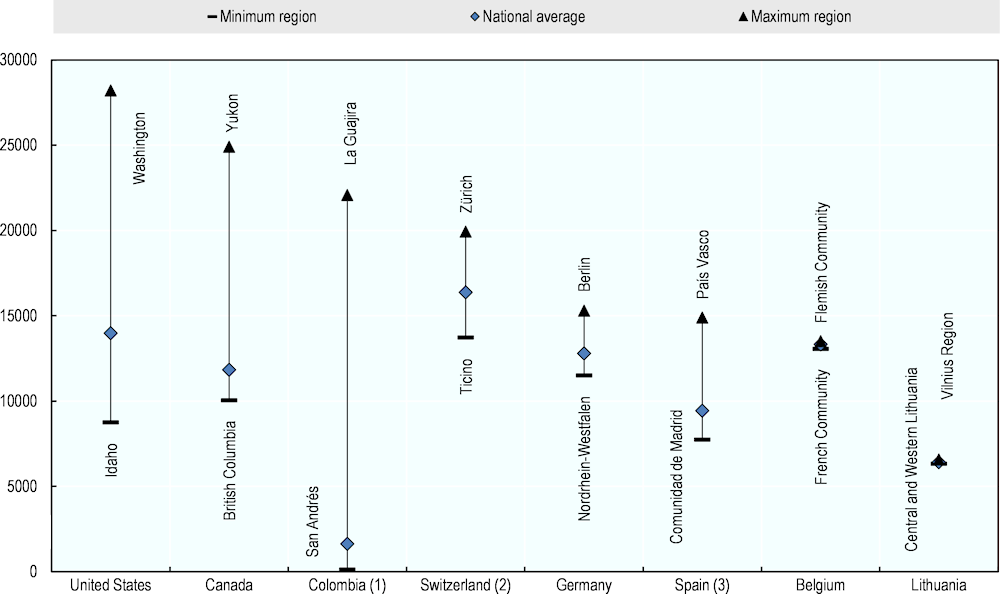

Even if well-designed fiscal equalisation mechanisms are in place, education spending might still differ considerably across jurisdictions in decentralised systems. For example, according to data from Education at a Glance 2021, the region with the highest level of per-student expenditure in the United States spends almost three times as much as the region with the lowest level of spending. Smaller regional differences are found in Germany, Spain and Switzerland (Figure 3.2) (OECD, 2021[11]). Such spending differences might indicate different priorities for public education, a potential for efficiency savings in some jurisdictions and/or potential inequities in the education services provided to students. One option to ensure a basic level of funding for all schools is to earmark some central funding for schools based on assessed needs while another part can be used at the discretion of sub-central authorities. Sharing experiences in approaches to school funding between sub-central jurisdictions should also be encouraged and facilitated (OECD, 2017[3]).

Fiscal decentralisation should be accompanied by adequate monitoring, evaluation and reporting to ensure transparency in the flow of resources

Finally, the expansion of sub-central spending, revenue collection and borrowing powers creates challenges for fiscal control and financial reporting (Schaeffer and Yilmaz, 2008[9]). Adequate monitoring, evaluation and reporting processes need to be in place to ensure that funds transferred from central to sub-central governments are used efficiently and in line with laws and regulations. Sub-central authorities should provide adequate information about their education budgets to increase transparency about the flow of resources (OECD, 2017[3]).

Figure 3.2. Subnational expenditure on educational institutions per full-time equivalent student (2018)

Note: To ensure comparability across countries, expenditure figures were converted into common currency (USD) using national purchasing power parities (PPPs). However, differences in the cost of living within countries were not taken into account. Countries are ranked in descending order of maximum subnational expenditure on educational institutions per full-time equivalent student.

1 Government expenditure data transferred to subnational entities.

2 Only expenditure for teaching and non-teaching staff.

3 Public expenditure on education in public institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[11]), Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en, Figure C1.2.

Addressing the complexities of decentralised school funding systems through whole-system approaches

The distribution of responsibilities for school funding is complex in many countries

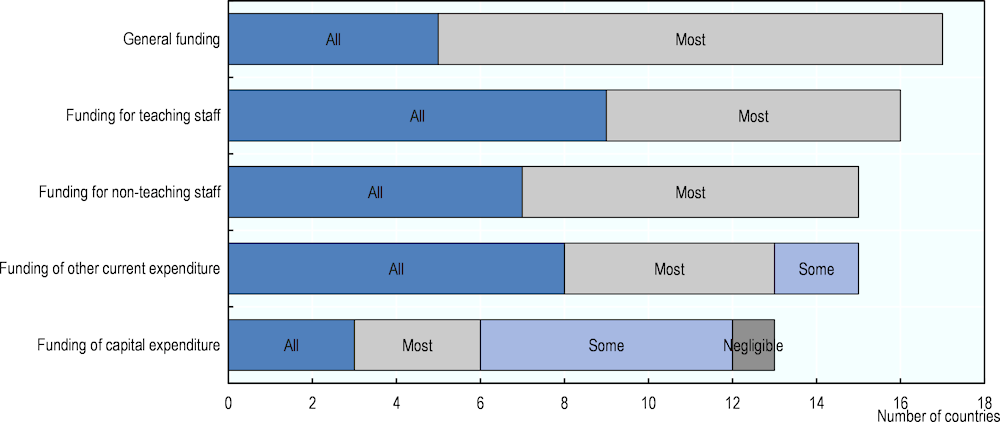

Many school systems have a complex distribution of funding responsibilities, which may differ by resource category (e.g. current or capital spending), by level of education (e.g. primary or secondary) and by type of school education (e.g. general or vocational education) (OECD, 2021[11]). For instance, in most countries the local government levels have retained responsibility for managing and funding lower levels of schooling (mainly pre-primary, primary and sometimes lower secondary education) whereas regional or central governments are more often in charge of secondary and upper secondary education (OECD, 2017[3]). Another example is the more centralised control over capital investments as compared to current expenditure. While the OECD School Resources Review indicates that central authorities are more involved in capital investment compared to current expenditure, all except one participating country declared that responsibilities for capital investments were shared between more than one actor, most commonly involving both central and local authorities (OECD, 2018[5]). Finally, the staffing of schools and the management of the related budgets also typically involves multiple actors. For example, schools may be responsible for employing their teachers for which they receive central funding, while local authorities cover the payroll of administrative staff (OECD, 2019[4]).

Successful decentralisation requires clearly delineating responsibilities, establishing well-functioning co-ordination mechanisms and adequate data management

In order to ensure the effectiveness and transparency of school funding, a clear distribution of responsibilities as well as mechanisms for co-ordination between different actors are required. It needs to be clear which authority is responsible for funding particular levels and types of education as well as categories of resources, such as the employment of teachers, school leaders and other staff; infrastructure investment and maintenance; and ancillary services, including school meals and transportation. In decentralised contexts, it is important that each level of government is accountable for its specific spending decisions. Effective accountability of sub-central authorities likewise requires reliable and co‑operative control structures across levels of government (OECD, 2017[3]).

Co-ordination is also crucial for managing trade-offs and balancing short and long-term considerations in the use of school resources in multi-level systems. For instance, the distribution of responsibilities for the use of staff funding will influence actors’ scope to determine the number and profile of staff hired and the degree to which hiring decisions reflect specific school needs (OECD, 2019[4]). Similarly, the division of responsibilities for capital investments and current maintenance funding will influence the scope for assessing the interactions between both types of spending and for determining the most efficient resource allocations. Capital investments can have a significant long-term impact on maintenance costs, just as putting off repairs can result in the need for major overhauls (OECD, 2018[5]).

As the experience of the OECD School Resources Review participants shows, complex governance arrangements for school funding entail the risk of inefficiency arising from overlapping responsibilities as well as a lack of transparency, accountability and trust in the use and flow of financial resources. Efficiency challenges may emerge where parts of a school system are managed by different levels of administration in relative isolation. This may also raise difficulties for managing information on the use of funding and its impact on equity and quality in student learning, well-being and development (OECD, 2017[3]).

Solving such complexity challenges in school funding governance requires a whole‑system approach that involves a reflection about both structures (e.g. the most efficient number of governance levels involved in school funding) and processes (e.g. stakeholder involvement, open dialogue and use of evidence and research). Thinking of structures in isolation without connecting them to supporting processes will not provide systemic and sustainable solutions. In general, reducing the number of intermediary government tiers that funding flows through before reaching schools, can decrease the bureaucratic burden and promote possibilities for central steering. Further, improving the availability of data on different aspects of school funding across levels of governance and institutions, can help monitoring the effectiveness of school funding and create transparency in resource use at different levels of a school system (OECD, 2017[3]).Box 3.2 provides an example from Austria for a large-scale reform aiming to reduce complexity in the management and distribution of resources.

Box 3.2. School funding governance reform: the example of Austria

As part of a larger school reform package adopted in 2017, Austria reorganised its administration of federal and provincial schools. The reform entailed the creation of joint Boards of Education (Bildungsdirektionen) in each province as of 2019. Previously, responsibilities were fragmented by school level and type between the federal government and the provinces, resulting in an obscure and inefficient use of resources. Next to the administrative re-organisation, the reform sought to improve transparency, effectiveness and efficiency in resource use through the introduction of a more comprehensive education controlling system. The controlling system covers all schools and includes quality management, education monitoring and resource controlling. Further, a framework for index-based resource allocations (Chancenindex) was introduced to establish more uniform and transparent criteria for the distribution of funding teacher resources. The Chancenindex allocates additional resources based on student background and school inspections are used to enable more nuanced targeting of schools. Transparency and efficiency in resource use should also be improved through a uniform electronic personnel management system for all federal and provincial teachers.

Sources: OECD (2019[16]), Education Policy Outlook 2019: Working Together to Help Students Achieve their Potential, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/2b8ad56e-en; OECD (2017[3]), The Funding of School Education: Connecting Resources and Learning, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276147-en; BMBWF (2017[17]) Bildungsreform: Autonomiepaket und Bildungsdirektion Informationsunterlage (Education reform: school autonomy deal and Joint Boards of Education Information sheet), https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/dam/jcr:24746cd7-9c94-4468-90e0-bac523eb225a/brf_ueb.pdf.

In decentralised systems, building capacity at the local level for managing school funding is also essential

Wherever sub-central authorities play a key role for managing school funding, it is crucial to build the necessary technical skills and administrative capacity at a local level. Decentralised school funding arrangements place significant demands on local authorities for budget planning and financial management. Smaller municipalities may have less experience and staff and thus face significant capacity constraints, which can create or exacerbate regional inequities (Dafflon, 2006[18]). Capacity building at a local level is of particular importance in countries with a large number of small municipalities, such as the Czech Republic, France, the Slovak Republic, Hungary, Switzerland and Austria. In these countries, the horizontal fragmentation of responsibilities for school funding can undermine the quality of public services and cause inefficiency (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2021[8]).

Professional training and support are important aspects to consider for improving capacity at the local level. Competency frameworks for local leaders and administrators that reflect the skills necessary for financial management can be used to guide training and professional development as well as recruitment processes (OECD, 2017[3]). However, the professionalisation of local management depends not only on the capacity of local actors themselves, but also on the institutional settings in which they operate. This includes their access to key information, as well as mechanisms to monitor and provide feedback on the work of municipalities and their services. A further – so far often underdeveloped – way for building the capacity of local authorities lies in the creation of networks and collaborative practices (e.g. jointly employing specialised staff for budgeting, financial control and the use of performance data) (OECD, 2017[3]). Since capacity building is a complex enterprise and takes time, it is ideally thought out from the beginning and planned strategically (Burns, Köster and Fuster, 2016[19]).

Norway provides an example for systematic investment in building capacity at all levels of the system, based on local analysis and decision making in networks of municipalities. The country has a long-standing tradition of decentralisation, with counties responsible for upper secondary schools and municipalities responsible for early childhood, primary and lower secondary education. While governance arrangements promote local engagement, there have been concerns about local capacity. To establish a more sustainable approach for education improvement and address capacity differences across local authorities, a new collective competence development model for schools has been introduced. The model relies on three complementary pillars: 1) a decentralised scheme that aims to ensure that all municipalities implement competence-building measures, by channelling state funds to the municipalities; 2) a follow-up scheme in which municipalities and county authorities that report weak results in key education and training areas over time are offered state support and guidance; and 3) an innovation scheme that is intended to result in research-based insights on the school system. As part of a local government reform in effect since 2020, the number of municipalities and counties was reduced, also seeking to improve quality, equity and efficiency (OECD, 2019[20]; OECD, 2020[21]).

Networks of advisors can also support the education work of local authorities and complement other capacity building strategies. In Denmark, for instance, the education ministry has created a national body of education consultants who advise municipalities (and schools) in their improvement efforts. This initiative promotes mutual learning processes by both sharing expertise with local authorities and reporting back local experiences to the central level (OECD, 2019[4]).

Some countries with a large number of small providers have responded to capacity challenges by merging providers and thereby consolidating capacity for effective resource management (see the example of Norway above). Others are considering to move responsibilities to higher levels of the administration or to create new administrative bodies to administer resources for a larger number of schools. Chile, for example, has been undergoing a process of recentralisation of its public school system since 2015, with a number of Local Education Services and a national Directorate for Public Education gradually taking over responsibilities from municipalities. This process is expected to be completed by 2025 (OECD, 2019[16]). An evaluation of the reform’s first year of implementation suggests that such structural reorganisations should be accompanied by sustained capacity building, including the formation of horizontal networks, in order to lead to tangible improvements in teaching and learning (Anderson, Uribe and Valenzuela, 2021[22]). In a similar reform, the central government in Hungary took over the maintenance of schools from local governments in 2011 to respond to challenges identified with decentralisation (OECD, 2019[16]). Where responsibilities are re-centralised, it is important that funding decisions involve consultation with local stakeholders and remain responsive to local needs (OECD, 2017[3]).

Giving schools autonomy for managing and allocating funding

Schools have different degrees of resource autonomy across countries

Since the early 1980s, many countries within and outside the OECD, such as Canada, Finland, Hong Kong (China), Singapore, Spain and Sweden have granted their schools greater autonomy with respect to both curricular design and resource allocation decisions, albeit starting from different levels (Eurydice, 2007[23]; Wang, 2013[24]). While the motivation for these reforms varied across countries, they were typically expected to increase schools’ responsiveness to the demands of local communities, reduce bureaucracy and create an environment conducive to innovation (Burns and Köster, 2016[25]; Bullock and Thomas, 1997[26]).

Schools enjoy most freedom over the use of their resources when central or sub-central authorities allocate a large proportion of their funding in the form of unrestricted block grants, which gives schools the discretion to allocate resources freely across all areas of spending. In other school systems, schools have intermediate levels of autonomy since they receive financial resources linked to certain conditions for spending. Grants may, for instance, be restricted to a particular area of spending (e.g. operating costs) or be earmarked for a specific item (e.g. professional development). By contrast, systems that provide schools with “in kind” resources or cover payments directly through higher authorities provide little resource autonomy (OECD, 2017[3]).

Reaping the benefits of resource autonomy requires strong educational school leadership and technical support

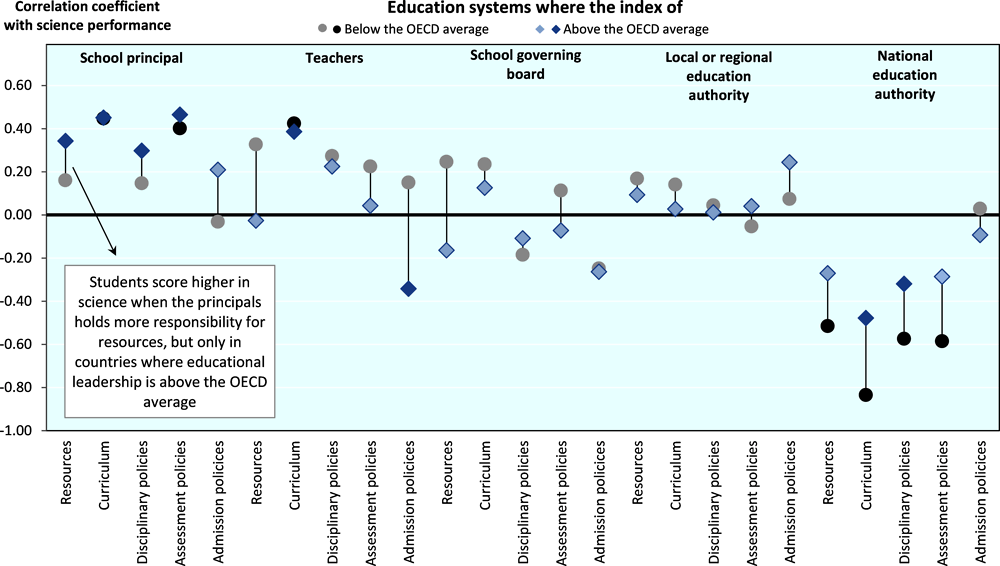

While budgetary autonomy for schools may yield a range of benefits, research and experience suggest that the relationship between budgetary autonomy and school performance is not clear cut and that greater financial responsibility is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Overall, students’ science performance in PISA 2015 was higher where school leaders held more responsibility for managing resources (e.g. formulating the budget, hiring and firing staff), but only when comparing countries where principals’ reported stronger educational leadership than the OECD average (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. Correlations between the responsibilities for school governance and science performance, by index of educational leadership (2015)

Note: The responsibilities for school governance are measured by the share distribution of responsibilities for school governance in PISA 2015 Table II.4.2; Results based on 26 education systems where the index of educational leadership is below the OECD average, and 44 education systems where it is above the OECD average; Statistically significant correlation coefficients are shown in a darker tone.

Source: OECD (2016[27]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en, Figure II.4.10.

The benefits of budgetary devolution therefore likely depend on schools’ ability to use their autonomy in a constructive way and to deal with the related challenges. This requires investment in school leadership, as well as adequate administrative and technical support. Measures that are comparatively easy to implement, such as training on time‑management, could help school leaders to resolve tensions between pedagogical and administrative leadership responsibilities, increase their time spent on high-priority tasks and reduce stress (OECD, 2019[4]). As schools administer their own funds, they need to set up budgeting and accounting systems, manage contracts and procurement, and discuss resource matters with the school community. Some systems, such as England (United Kingdom) provide practical support to schools to meet such responsibilities and improve efficiency in spending (e.g. on non-staff goods and services) (Box 3.3).

Extending the budgetary responsibilities of schools requires strategies to mitigate potential inequalities and to hold schools accountable for resource use

Furthermore, if school autonomy is not to exacerbate inequities across schools, a comprehensive regulatory and institutional framework needs to be in place (Bullock and Thomas, 1997[26]). Building capacity for resource management tasks is particularly challenging for small schools and those in disadvantaged circumstances. One way to reduce potential inequities is to extend budgetary autonomy selectively to schools with sufficient capacity or to pool administrative resources across multiple schools (e.g. sharing human resources, facilities and back-end infrastructure). The school associations established in the Flemish Community of Belgium provide a good example of collaborative platforms that promote cost saving across schools by allowing them to share resources. While the formation of and participation in school communities is voluntary, the government provides incentives in the form of additional staff resources that can be shared between the schools of an association (OECD, 2017[3]).

Finally, extending schools’ budgetary autonomy needs to be accompanied by effective monitoring and evaluation processes to ensure that funds are used in line with overall objectives and that all students receive a high-quality education. School boards can play a key role in local monitoring and in providing horizontal accountability, and should be supported through guidance, resources and information. Approaches to school evaluation should consider how schools use their funds to promote the general goals of the school system as well as student learning and development. Countries with a large degree of school autonomy should also encourage the dissemination of information about school budgets together with information about school development plans and other activities at the school (OECD, 2017[3]).

Box 3.3. Initiatives to support schools in their resource management responsibilities and increase the efficiency of non-staff spending in England (United Kingdom)

England (United Kingdom) has launched multiple initiatives to support schools in their resource management and increase the efficiency of school’s non-staff spending to respond to the budgetary pressures.

The Schools’ Buying Strategy, launched by the Department for Education in 2017, sought to support schools in saving on their non-staff-expenditure by sharing various tools and knowledge on budget management with school leaders and financial administrators (typically “School Business Managers”). As part of a wider effort to advance the professionalisation of schools’ financial staff, the ministry collected best-practice guidance and practical support such as templates for each step of an effective procurement procedure. The tools provided by the ministry also include an online benchmarking system that allows schools to compare their overall spending patterns and specific expenditure lines with those of similar schools to identify inefficiency and cost‑saving potentials.

Since many schools have difficulty procuring a wide range of goods and services in a complex market environment, the ministry has offered them the opportunity to take advantage of prices negotiated at the national level and benefit from economies of scale through “National Deals” – framework agreements. These National Deals give schools an opportunity to save on their existing contracts, for instance on water and electricity; software licenses; and Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) supplies. The National Deals programme also offers interest-free loans to fund energy‑saving improvements and the popular Risk Protection Arrangement, which provides schools with a cheaper alternative to commercial insurance providers.

By April 2020, the Schools’ Buying Strategy had secured savings of GBP 425 million and was being evaluated and revised based on lessons learnt throughout the implementation.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2018[5]), Responsive School Systems: Connecting Facilities, Sectors and Programmes for Student Success, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264306707-en; Department for Education (2021[28]), Schools’ Buying Strategy, London, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/schools-buying-strategy (accessed on 10 January 2022).

Setting regulatory frameworks for the public funding of private providers

The public funding of private providers seeks to improve choice and efficiency…

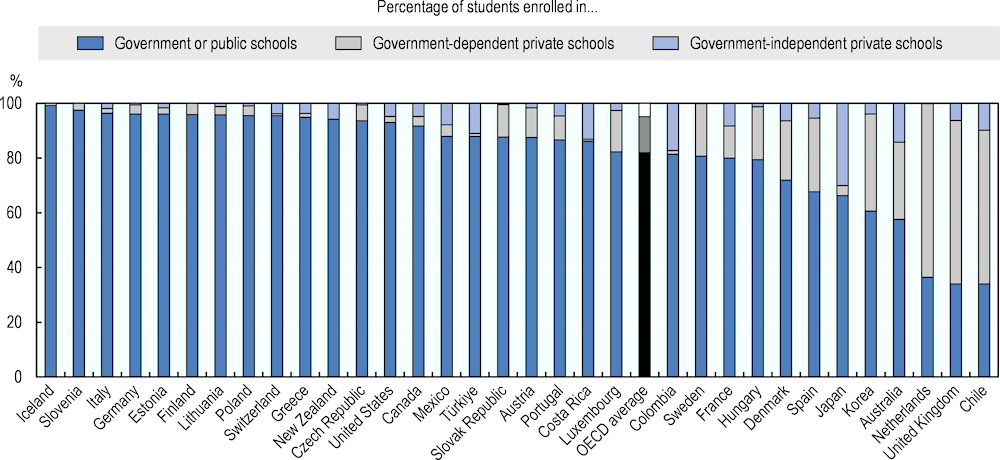

Over the past 30 years, more than two‑thirds of OECD countries have introduced measures to increase school choice (Musset, 2012[29]), often by publicly funding private providers and letting students and families decide which schools to attend. Financial support for private providers is usually embedded in parental choice systems where public funding either “follows the students” to whichever eligible school they choose to attend or is used to compensate parents for their expenses on private school tuition fees through vouchers or tax credits. These measures have resulted in some countries developing a substantial publicly funded private sector (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2018[5]) (Figure 3.4).

The public funding of private schools may be motivated by a range of different arguments whose relative importance varies across national contexts (for a review, see (Boeskens, 2016[30])). In some countries the policy is intended to guarantee the right of families to send their children to their preferred school, free of legal restrictions or financial barriers. In other countries, there is greater focus on school choice as a means to stimulate competition among schools and incentivise them to improve quality, stimulate greater diversity in the educational offer or encourage innovative pedagogical and governance arrangements that will increase efficiency and improve learning outcomes in the long run (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2018[5]).

Figure 3.4. Student enrolment in public and private schools (2018)

Note: Countries are ranked in descending order of the percentage of students enrolled in government or public schools.

Public schools are those managed by a public education authority, government agency, or governing board appointed by government or elected by public franchise. Government-independent private schools are those funded mainly through student fees or other private contributions (e.g. benefactors, donations); government-dependent private schools are privately managed schools that receive more than half of their funding from government sources

Source: Adapted from OECD (2020[31]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume V): Effective Policies, Successful Schools, https://doi.org/10.1787/ca768d40-en, Figure V.7.2.

…but there are risks of increasing social segregation and harming the public system

Experience from multiple countries indicates that the impact on equity and education quality of publicly funding private providers is influenced by the institutional arrangements in which they are embedded (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2018[5]). In particular, the conditions which private schools must fulfil to qualify for public funding are central to the successful governance of school choice systems. Among these eligibility criteria, private schools’ ability to select students and charge add-on tuition fees are particularly salient concerns. Allowing subsidised schools to select their students based on prior performance and aptitude tests may create barriers to inclusion which might jeopardise equity and education quality (OECD, 2017[3]).

Selective admission permits private schools to “cream skim” high-ability students from the public sector. Since parents often mistakenly evaluate a school’s quality based on its student composition, engaging in selective admission can allow schools to attain a competitive advantage without actually improving their education provision. Selectivity threatens to exacerbate student segregation between the public and private sectors and can widen existing achievement gaps. This process might deprive the public school system of high-ability students and harm those who are left behind by depleting public schools of vital resources and leaving them with a high share of disadvantaged students with greater resource needs (Boeskens, 2016[30]). In addition, school choice systems that permit private schools to demand significant parental contributions beyond the amount covered by the public subsidy could aggravate socio-economic segregation across schools (OECD, 2017[3]).

To mitigate this risk, adequate regulatory frameworks are required for the public funding of private providers

To mitigate risks to equity, it is important that all publicly funded providers are required to adhere to the same regulations regarding tuition and admission policies, and that compliance with these regulations is effectively monitored. In order to ensure that vouchers and other forms of public funding increase the accessibility of private schooling options, regulations should prevent subsidised private schools from charging fees that could constitute barriers to entry. Also, in order to ensure that school choice improves access to high-quality education rather than leading to selectivity and “cream skimming”, governments should regulate admission procedures and ensure that private providers adhere to the same standards of selection as public schools. Admission practices for oversubscribed schools should therefore be transparent and homogeneous across school sectors. The use of lottery systems to assign places in oversubscribed schools or formulas aimed at maintaining a diverse student composition could be considered (OECD, 2017[3]).

Chile’s 2015 Inclusion Law (Ley de Inclusión Escolar) reformed the regulation of the public funding of private providers to ensure an effective exercise of free school choice and reduce socio-economic segregation. Three main changes were made to the eligibility for public funding. First, the law mandated that private, subsidised schools must be owned by non-profit organisations to ensure that public funds are used for education purposes only. Second, the law eliminated “shared financing” (co-pago) where tuition fees were paid to schools by families to supplement public grants, although voluntary contributions by parents for extracurricular activities are still allowed. To compensate for the loss of funds for private, subsidised schools, the law increased the amount of resources allocated to school providers. Finally, the law prevented public and private-subsidised schools from employing any form of selection criteria when enrolling students (OECD, 2019[16]).

Mechanisms to ensure accountability and transparency are also important to ensure that subsidised private schools serve the public interest by delivering high-quality education, as well as to provide parents with the information they need to evaluate different schools’ processes and outcomes. Finally, these measures need to be complemented with initiatives to raise awareness of school choice options, improve disadvantaged families’ access to school information, and to support them in making better-informed choices (OECD, 2017[3]).

Establishing the overall approach to school funding

Different mechanisms can be used to allocate funding in school education, whether this is between different levels of the education administration or to individual schools. As a basic principle, a funding model needs to ensure that resources are allocated in a transparent and predictable way. A stable and publicly known system to allocate public funding allows schools and authorities to plan their development in the coming years. At the same time, a degree of flexibility in funding is also necessary to respond to unforeseen financial needs arising, for instance, from changes in student enrolment (e.g. through negotiations in the application of funding rules or an adjustable component) (OECD, 2017[3]). Even a small decrease in student numbers can result in a decrease of funding for staff salaries, which remain fixed. Flexibility is also provided through human resource management tools, such as working time (e.g. full-time and part-time work) and contract conditions (e.g. permanent and temporary employment) (OECD, 2019[4]).

In designing a funding allocation model that best fits the school system’s governance structures, school systems need to consider a series of questions that are discussed below.

The overall approach to school funding needs to balance regular funding to schools and targeted funding to support given objectives

Targeted funding has the potential to support specific policy objectives…

Besides the distribution of responsibilities for school funding and the conditions that are attached to different funding allocations, it is important to consider the channels through which funding is distributed. In particular, systems must choose the proportion of public funding that will be distributed via the main allocation mechanism as opposed to other mechanisms, such as targeted funding offered via special programmes. The main allocation mechanism refers to the regular funding to cover the payroll of staff as well as other fixed expenditures and is typically based on student enrolment, but also other factors depending on policy goals (OECD, 2017[3]).

While the funding of special programmes has its drawbacks, funding mechanisms external to the main allocation offer a certain degree of flexibility to the overall funding model and can support specific policy objectives and pilots of innovative practice. Targeted programmes can also help to compensate for inequities, especially if combined with a stable funding allocation. Other arguments for retaining a proportion of funding at a more central level for targeted programmes include: the need to respond to short-term or emergency expenditures occurring unevenly across schools (e.g. structural repairs); to support emerging needs (e.g. digital learning, tutoring interventions); and to ensure the adequate provision of services (e.g. in-service training for staff, availability of support staff) (OECD, 2017[3]).

A number of countries have employed targeted programmes for different purposes (e.g. to support mainstreaming of students with special education needs or to support rural schools) (Box 3.4). During the COVID-19 pandemic, a range of targeted programmes have been used to bridge socio-economic gaps in education. Across OECD countries, subsidies for ICT devices (personal computers, laptops) were the most common measure to target populations at risk of exclusion from distance education platforms. Some countries also provided financial incentives and support to vulnerable students, such as for food or transport (OECD, 2021[32]). Programmes to minimise declines in achievement due to remote learning have also been instituted (Box 3.4).

…but should be used in adequate balance vis-à-vis regular funding

Although targeted funding affords greater flexibility and control, distributing a larger proportion of funding through the main allocation mechanism can promote stability and lead to efficiency gains. In England (United Kingdom), for example, the central funding mechanism was found to be more efficient as a greater proportion of overall funding was delegated to schools, excluding only major capital expenditures and a few local services from the main funding allocation. This was coupled with a requirement that the major proportion of the local funding formula must be driven by student numbers and characteristics (OECD, 2017[3]).

An excessive reliance on targeted funding can result in overlaps and create a lack of predictability about future resource allocations. While targeted programmes allow for better steering and monitoring of resource use, they come with greater transaction costs and an administrative burden. Moreover, the accumulation of numerous targeted funds can lead to a piece‑meal re‑centralisation of funding, increase complexity and reduce transparency in school funding. Indeed, the use of targeted funding mechanisms – external to the main allocation– can lead to governance challenges and a lack of clarity on how funding is used at sub-central or school levels (OECD, 2017[3]).

The OECD School Resources Review thus highlighted the importance of striking a balance between regular and targeted funding to achieve the goals of funding systems more efficiently and simplify funding systems overall. This includes decisions about the best mechanism to support equity and channel extra resources to student groups with additional needs. There are arguments to reduce transaction costs by including equity-enhancing adjustments for particular student groups within the major part of the funding allocation rather than relying on targeted funding (OECD, 2017[3]).

Box 3.4. Examples for targeted funding for specific programmes in selected countries

Programmes to promote policy objectives and priorities

In Colombia, the education ministry is the main institution that plans, manages and supervises the financing of public education. The ministry can also support initiatives in the school system, according to government priorities through the ministry’s investment budget. In the past, financing has promoted teacher development as well as initiatives related to rural education.

In the Czech Republic, a number of specific education grants are used to fund specific experimental or piloting programmes and new education initiatives, often developed or proposed at a local level. If these programmes show positive outcomes, they may eventually be integrated into the mainstream financing scheme.

In England (United Kingdom), schools serving disadvantaged students receive resources through a targeted programme (Pupil Premium), in addition to their regular funding allocation. They are free to spend these according to their needs but are also held accountable for their decisions.

In New Zealand, the education ministry funds schools (which are administered by boards of trustees) directly, but may also provide targeted services and programmes. For instance, the ministry funds a dedicated learning and behaviour service (Resource Teachers: Learning and Behaviour, RTLB) which is more efficiently provided for a greater number of schools. This service covers education support, release time for classroom teachers, and professional development in behaviour management or curriculum development.

Programmes to minimise declines in achievement due to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

In France the programme “Learning Holidays” was implemented in 2020 and 2021 to support students that may have been particularly affected by school closures. This initiative builds on co-operation with local authorities and associations and has two main objectives: 1) addressing learning gaps and reducing the risk of dropout; and 2) ensuring children’s access to enriching experiences during summer vacations.

In Portugal, all public schools have been able to apply for additional resources under the umbrella of the "Plano 21|23 - Escola+", a programme with more than 40 measures for education recovery.

Sources: OECD (2021[32]), The State of School Education: One Year into the COVID Pandemic, https://doi.org/10.1787/201dde84-en; OECD (2017[3]), The Funding of School Education: Connecting Resources and Learning, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264276147-en, OECD (2019[4]), Working and Learning Together: Rethinking Human Resource Policies for Schools, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b7aaf050-en.

It is important to choose the right method to determine the amount of regular funding for schools…

Regular funding can be allocated to schools using broadly one of four main approaches, the use of which also differs depending on whether funding is allocated for current or capital spending:

Administrative discretion, which is based on an individual assessment of the resources that each school needs. While this can involve the use of indicators, these indicator-based calculations are non-binding and might not be universally applied to all schools.

Incremental costs, which consider historical expenditure to calculate the allocation for the following year, with minor modifications to take into account specific changes (e.g. student numbers, school facilities, input prices). This approach is often combined with the use of administrative discretion, and both approaches are usually used in centralised systems.

Bidding and bargaining, which involves schools responding to open competitions for additional funding offered via a particular programme or making a case for additional resources.

Formula funding, which involves the use of objective criteria through a universally applied rule to establish the amount of resources to which each school is entitled. Formula funding relies on a mathematical formula which contains a number of variables, each of which has a coefficient attached to it to determine school budgets (OECD, 2017[3]).

Allocating funding based on the needs of a given school (i.e. administrative discretion and bidding and bargaining) is more direct than funding based on a set of indicators of needs. However, when allocating resources to a large number of schools it is difficult to be aware of specific needs, and the distribution of funding on a discretionary or incremental basis is rarely efficient or equitable. When funding is allocated on a historical basis, this funds existing staff year after year and gives no incentives for schools to reduce their expenditures, increase their efficiency, or improve quality of provision. Historical funding provides stability and predictability, but it may also inhibit the expansion of schools with increasing demand, while supporting those whose development is lagging behind (European Commission/Eurydice, 2000[33]).

While administrative discretion plays an important role in the allocation of school funding in many countries, the use of formula funding is well suited to the distribution of current expenditure and has been taken up in many countries (see Figure 3.5). The use of formula funding contributes to more transparent and predictable allocation systems, in particular when funding is linked to student numbers (European Commission/Eurydice, 2000[33]). The transparency that a funding formula provides can have a beneficial impact on policy debates and help building general acceptance of a funding model as funding criteria and allocations can be scrutinised and debated. A well-designed funding formula is, under certain conditions, the most efficient, equitable, stable and transparent method of distributing funding for current expenditures to schools (OECD, 2017[3]).

Figure 3.5. Proportion of public funding allocated by central or state governments to public primary educational institutions (or the lowest level of governance) using funding formulas (2019)

Source: OECD (2021[11]), Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en, Figure D6.3.

… and to regularly review funding mechanisms and establish implementation strategies when introducing new funding mechanisms

To succeed, funding mechanisms must not only be well-designed but also implemented effectively. This is particularly so as the introduction of any new funding model will create winners and losers - unless additional resources are made available (OECD, 2017[3]).

In Austria, for example, the introduction of socio-economic criteria into the existing formula to distribute resources caused significant tensions. While social partners supported the introduction of an index‑based resource distribution, some provinces with a large share of rural schools opposed this change since it would likely have resulted in the redistribution of funding from rural to urban schools. Finally, as part of a major school reform in 2017, the education ministry was given the opportunity to introduce a socio‑economic index into the resource allocation, but this required the introduction of new regulations (see Box 3.2).

Funding model reforms in England (United Kingdom) and New Zealand have also been controversial (OECD, 2017[3]). As of January 2022, both countries were considering and debating further changes to their school funding systems. England (UK) is still exploring the introduction of a hard national funding formula which would reduce the role of local authorities in deciding funding allocations to schools (Roberts, 2022[34]), while New Zealand continues to assess how resources might enhance equal learning opportunities, especially for socio-economically disadvantaged students (Ministry of Education, 2021[35]).

Experiences in many countries thus highlight the importance of effectively managing the political economy of reforms and forming realistic expectations of their implementation costs. Adequate stakeholder consultation is important to increase the perceived fairness of an allocation system and can help ensure that funding mechanisms respond to unanticipated challenges. For instance, the introduction of a new funding model based on per-capita financing can set incentives for efficiency and balanced student-teacher ratios. However, when facing a decline in the school-age population schools under such funding systems may struggle to keep existing teaching staff on the payroll or to find them alternative employment in the school system. In such contexts, securing additional funding for teacher redundancy packages in advance may be an important factor for success (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2019[4]).

The examples of Australia, the Flemish Community of Belgium and the Czech Republic demonstrate the need to form realistic expectations about the costs of rolling out new funding models. In Australia, the government explicitly assured the public that no school would lose funding as a consequence of a major review of the country’s funding model. The aim of the review was to better ensure adequate funding for students with greater education needs. As such, the government needed to commit significant additional resources to implement the reform. In the Flemish Community of Belgium, changes to the system for distributing operating grants and staffing went in line with substantial increases in the overall budget (OECD, 2017[3]). In the Czech Republic, a school funding reform in force since 2020 shifted the basis of national funding from student numbers to the number of teachers or hours taught. This change was accompanied by an increase in the total amount of resources for public education in the national budget (about 12 % in 2020) (OECD, 2019[16]; Eurydice, 2022[36]).

The OECD School Resources Review has also highlighted the importance of conducting periodic reviews of funding allocation mechanisms to ensure they optimally serve the goals of the education system. The experience of countries that engaged in such reviews, such as England (United Kingdom) and the Flemish Community of Belgium suggest some common procedural and design practices. For instance, independent bodies (e.g. an existing independent agency or a panel of independent researchers) typically take a substantive role in providing recommendations for reform, with government officials providing data, administrative and analytical support. Other common elements include: a clear mandate for the review in terms of focus and scope; a designated timeline and positioning of the review within the broader policy context; information on mechanisms for collecting evidence (e.g. for stakeholder consultations, the analysis of funding in a sample of schools and research) (OECD, 2017[3]).

Current expenditure needs to be distributed in a predictable and transparent way

Funding formulas are a transparent mechanism to align the distribution of funding to schools with policy objectives…

Any funding allocation mechanism should be designed to fit the governance and policy context of the school system. In the allocation of funding for current expenditure, there may be different goals that are more important than others depending on the overarching policy objectives (OECD, 2017[3])

Funding formulas are used in many countries to distribute regular funding for current expenditure such as staff salaries. Through differential weighting given to each of the main components included in the formula, funding formulas can be designed to support a balance of different policy goals (OECD, 2017[3]):

Promoting equity is one of the most important functions of formula-based funding. Universal per-capita allocations for students in specific grades can ensure horizontal equity (i.e. the similar treatment of recipients with similar needs). To promote vertical equity (i.e. the provision of different funding levels for recipients with different needs), the basic allocation can be adjusted systematically using need-based coefficients.

Setting incentives for funding recipients and supporting particular policies (i.e. a directive function).

Regulating the market (i.e. supporting school choice policies). The greater the proportion of funding that is allocated on a simple per-student basis, the more this function will be emphasised.

While there is no single best-practice funding formula, there are a set of principles that can guide the design of an effective formula. One major challenge lies in accounting for the differences in costs associated with the varying education needs of students and providing different funding levels to schools based on legitimate differences in unit costs that are beyond the control of the school. This calls for a formula which incorporates coefficients to adjust for these differences. However, funding formulas must strike a balance between complexity – which is needed to capture differences in schools’ needs – and transparency – which ensures that the funding model is accessible and understandable to stakeholders.

As a guide for designing formulas to better meet differential needs, research has identified four main components: 1) a basic allocation per-student or per class that is differentiated based on students’ grade or level of schooling; 2) an allocation for specific education profiles or curriculum programmes (e.g. different vocational fields or special education needs programmes); 3) an allocation for students with additional education needs adjusting for different student characteristics or types of disadvantage; and 4) an allocation for specific needs related to school site and location, adjusting for structural differences in operational costs, such as for rural areas with lower class sizes. Comprehensive and compelling analysis and empirical evidence on the exact cost differences can support policy discussions to adjust parameters included in funding mechanisms. Reliable evidence should be gathered on the adequacy of funding in general, and for specific elements that the funding mechanism aims to address (OECD, 2017[3]).

… and can be designed to set desirable incentives for schools

Funding formulas should also promote budgetary discipline at the local and school levels. Student enrolments will be an important factor determining resource allocations in all school systems to ensure sufficient teaching staff for the required instruction time. The required resources can be determined based on student numbers or the number of classes. Allocating funding on a per-student basis promotes competition and efficiency. At the same time, fixed costs are not responsive to changing student numbers. Per-student funding can therefore create pressures for schools with small or declining enrolments and increasing staff-student ratios. To acknowledge that not all costs are linear, a funding formula can incorporate weights for smaller schools. Such an approach would incentivise most schools to reduce the number of classes by raising class sizes, while granting more resources to particular schools (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2018[5]). Box 3.5 provides examples of some approaches to funding formulas in OECD countries.

Teachers’ salaries (over which sub-central authorities or schools may have no control) will be a further important factor that determines schools’ resource needs. Some school systems therefore allocate funding based on some kind of estimation of average cost as part of their funding formula. Such systems: 1) provide a framework for balancing actual teacher salary expenses with the amount of funding available to pay for staff and 2) can act in an equalising way as they promote similar staffing levels across schools. In Estonia and Lithuania, for example, average teacher salaries have been important input variables in the formula determining resource allocations (OECD, 2017[3]; OECD, 2019[4])

Periodical reviews are necessary to ensure funding formulas remain fit to address dynamic policy needs. Such reviews can allow governments to identify whether there is a need to revise the formulas’ adjustments for student and school needs, as well as the weight of formula‑based funding relative to targeted funding programmes within the overall funding envelope (OECD, 2017[3]).

Box 3.5. Examples for formula-based funding to schools in select jurisdictions

The Netherlands have introduced formula-based funding for both primary and secondary education. Since a reform in 2019, the equity funding for primary education estimates students’ disadvantage on the basis of an indicator, which consists of five background characteristics: the level of education of both the mother and the father, the country of origin of the parents, whether parents are in debt restructuring, the duration of the mother's stay in the Netherlands, and the average level of education of mothers of students at school. Schools receive additional resources for students belonging to the 15% with the greatest estimated disadvantage. The additional budget for secondary schools used to be calculated based on the number of students whose parents have a weak education background and the socio-economic characteristics of the school’s neighbourhood. A corresponding indicator of student disadvantage in secondary education is currently under development. The Dutch equity funding system is an example of an encompassing index-based approach, although the share of index-based funding as a percentage of total education funding is relatively low (about 4.5%).

Toronto (Canada) applies a “Learning Opportunities Index” (LOI) to govern the distribution of resources across schools in the municipal school district. The funding needs of schools are evaluated based on six variables: 1) Median income in the students’ residential area; 2) the share of low-income families in a particular area; 3) the share of families receiving social assistance; 4) the share of adults without high school diploma; 5) the share of adults with a university degree; and 6) the share of single parents. Students are matched to neighbourhoods based on postal codes. Similar to the Netherlands, the share of resources distributed according to the needs-based formula only amounts to about 5% of total education spending.

The Swiss canton of Zurich uses a social index to distribute teaching resources across schools since 2004/05. The social index contains three elements based on official statistics: first, the share of foreigners (excluding immigrants from Austria, Germany and Liechtenstein), the share of children receiving social assistance, the share of tax-payers with a low income. Different from the other indices, this index does not provide additional resources for disadvantaged students but uses the index to distribute regular teaching resources.

Source: Nusche, D., et al. (2016[37]), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Austria 2016, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264256729-en.

… but indicators to distribute funding to schools need to be carefully selected

The OECD School Resources Review has revealed the importance of paying adequate attention to the choice of indicators for allocating funding and understanding the technical and analytical demands for the design of effective allocation mechanisms. This applies both to systems using funding formulas as well as those using other methods, even if they do not systematically use a single set of criteria to allocate funding (OECD, 2017[3]).

A range of different indicators can be used to determine the proportion of students with identified needs for additional resources. For instance, area-based funding aims to address the additional challenges that arise from a high concentration of socio-economically disadvantaged students. However, such approaches risk leaving out a proportion of the disadvantaged population and include many individuals who are not disadvantaged. There is also evidence that the “target area” label can be stigmatising and encourage the flight of middle-class families from these areas. As a result, there has been a broad shift to using indicators that are more specific to the actual composition of the student body in schools (OECD, 2017[3]), as illustrated in Box 3.6.

Box 3.6. Initiatives to account for school-specific student characteristics in the allocation of funding: Examples from the French and Flemish Communities of Belgium

In the French Community of Belgium, the socio-economic index (indice socio‑économique) is based on the student's residential area, using indicators such as income, qualification level and unemployment rate. These indicators are subject to review every five years. School leaders report the required information on their students annually which - upon verification from central authorities – is used to attribute a value on the socio-economic index to each student. The funding allocation is determined by ranking schools based on the average of students’ socio-economic indexes. The bottom quartile of schools then qualifies for additional teaching periods or funding allocations.