This chapter examines past labour market transitions that affected regional labour markets and communities. It analyses how digitalisation, globalisation and the transition out of coal compare to the green transition. Furthermore, it examines local success drivers of managing past labour market transitions and aims to draw policy lessons for the green transition. The chapter combines macro analysis of transformations, such as globalisation or the shift away from coal, with local case studies from around the OECD.

Job Creation and Local Economic Development 2023

3. Learning from past and ongoing transitions

Abstract

In Brief

The effects of past and ongoing labour market transitions bear similarities to the green transition. Digitalisation, globalisation and the exit from coal have been disruptive to local labour markets and communities and have had an uneven impact on regions. Some regions benefitted from these changes, whilst others faced new challenges. The economic readjustment and diversification that occurred in negatively impacted regions had varying success. Good practises and success drivers in these regions can serve as lessons for the hardest-hit regions in the green transition.

Past transitions have been largely market-driven, whereas the green transition is largely policy driven. This gives policy makers more opportunities to control both the supply and demand effects of labour markets but it also comes with great responsibility in terms of getting policy right.

Drivers of successful local policy in past transitions:

Share a clear and long-term vision and strategy for local economic transition. This vision can be created top-down, but it is important that stakeholders operating at different levels of government generally agree with this vision. Coherence is important to create trust amongst workers, communities and businesses as well as a willingness to invest and anticipate long-term changes.

Invest in local re-skilling and re-education programmes. Re-skilling the workforce is important to increase resilience. The availability of future-proof skills is also a comparative advantage for a region. It is important to monitor the demand for skills and offer programmes that match demand.

Build strong coalitions focussing on social inclusion. These can include horizontal as well as vertical levels of government, worker representatives, employer representatives, educational institutions and other possible stakeholders.

Invest in the attractiveness of the region and promote innovation. Investment in infrastructure, education, healthcare and recreational facilities can help retain and attract the workforce during an economic downturn. Investment in innovation is needed to stimulate demand for jobs and skills.

Assist laid-off personnel quickly immediately after—or ideally before—they are let go. Providing easily accessible career guidance and well-designed income support to maintain household finances can consolidate trust and cooperation between different institutions and workers while reducing resentment.

Use regional comparative advantages. Regions can use worker skillsets available in the labour market, and exploit existing comparative advantages, thereby significantly lowering adjustment costs. However, locking in ailing business models would need to be avoided.

Introduction

Throughout the past decades, OECD countries have gone through a number of significant economic transitions. Megatrends such as globalisation, digitalisation, automation or demographic change have been transforming economies. For example, globalisation has driven a closer integration of national economies1, which has increased overall prosperity but also heightened the risk of job displacement for some workers. Likewise, technological progress has generated new job opportunities but has also radically reshaped or displaced jobs (Frey and Osborne, 2017[1]; Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[2]; OECD, 2018[3]). More recently, the impact of COVID-19 and rising energy prices have forced both employers and employees to become even more flexible and resilient (OECD, 2020[4]; OECD, 2022[5]; OECD, 2019[6]).2

Implementing the Paris climate goals will require an economic transition to greener economies (see Chapter 1). In order to manage the detrimental effects of climate change, OECD economies have pledged to make efforts to maintain the global temperature increase, relative to pre-industrial levels, to below 2 degrees. Awareness is growing that such a change will require a paradigm shift. Societal and economic systems must undergo a fundamental change to facilitate growth with a lower carbon footprint or in a circular model. This will cause transitions in how firms operate, and how people live, which will have repercussions in the labour market, thus requiring many employers, employees, and governments to be increasingly adaptive. Most research so far agrees that the green economy will provide many opportunities. However, for heavy polluting industries and professions, the future might require a complete overhaul. (OECD, 2019[7])

Labour market transitions in OECD countries are not limited to global megatrends. During a transition, regions may experience the sudden downsizing or disappearance of an important employer or industry (Fouquet and Pearson, 2012[8]). Local communities’ may also face a large-scale economic restructuring. The exit from coal and mining or the offshoring of economic clusters such as textiles or manufacturing to other parts of the world have had a strong impact on affected communities. In many cases, they forced them to rethink their economic development strategy and turn to new sources of job creation.

All of those transitions have a number of features in common with the green transition. First, they entail a readjustment process in the labour market, with the reallocation of employment across sectors and industries, and a transformation of job requirements. Second, they can generate considerable opportunities and gains, as well as new risks. Third, they have an uneven impact across regions and segments of the population, which can exacerbate geographic and socio-economic inequality.

This chapter examines what national and local governments can learn from past and ongoing transitions in managing the transformation to a greener economy. It combines insights from both case study examples, including places that managed a restructuring of their economy successfully, and wider economic trends that affect entire national economies. It will first discuss the importance of policy in economic transitions. Next, it draws on past experiences and economic transitions to identify successful policies. Furthermore, it will explore good practices that could inspire solutions to the challenges associated with the green transition.

The importance of policy for managing the green transition

Regions dependent on carbon-intensive industries face many challenges when it comes to managing the green transition and making it inclusive. Achieving the Paris climate goals will require a fundamental change in carbon-intensive industries (OECD, 2018[9]). Many carbon-intensive industries, such as iron and steel production, chemical production, and extractive industries, tend to be geographically concentrated (OECD, 2022[10]). For communities depending on polluting industries, the green transition might entail large adjustment costs, especially in the short term. Managing the transition efficiently can mitigate both some of the short-term shocks and long-term negative effects (OECD, 2019[7]).

Policy can mitigate the negative effects of forced structural adjustments in regions. Without an adequate policy response, the green transition may exacerbate regional disparities and raise resentment amongst heavily impacted workers and resistance to climate policy (OECD, 2017[11]). Policies at the supranational, national, regional or local level can influence how communities can effectively benefit from the opportunities provided. Policies that helped regions successfully navigate past structural adjustment processes can provide lessons for communities facing such challenges in the near future.

A well-planned and successful economic transition requires time. Transitions take place gradually and often unfold in vastly different ways, making it complex to identify vital moments. Transitions usually involve a broad range of actors and extensive changes in different sectors and dimensions (Fouquet and Pearson, 2012[8]) (Jackson, Lederwasch and Giurco, 2014[12]). In a similar vein, managing a transition requires planning for the long run. It is not enough to act when industries are closing. It is paramount to plan interventions before factories, businesses or mines close down as well as invest in the area afterwards (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Phases of intervention before and during layoffs

Phase 1: Explore the potential for diversification. First, regions need to identify stakeholders in the area, at all levels of government, including workers’ representatives and important employers in the area. At this stage, regions can explore the local potential for diversification, and examine if the necessary infrastructure is in place to support the process. This includes roads, trains, digital infrastructure, etc. but also educational institutions and liveable communities.

Phase 2: Understand the labour market impact. Secondly, it is important to inquire about the specificities of the workers likely to be affected. In particular, it is fundamental to identify the characteristics of the workers (age, skills, etc), to understand potential complications, such as workers’ age when considering a reskilling policy. Furthermore, it is important to map the existing labour market policy.

Phase 3: Announce closing, anticipate layoffs and provide services. It is advised to announce the closing only when there is a clear timeline of the process and when there is an assistance programme in place. Communication is vital in this phase, workers could seek help in the form of retraining offers, career counselling, or unemployment benefits. Monitoring the success rate of programmes will help the effectiveness of future policy.

Source: (World Bank, 2022[13]; OECD, 2022[5]; OECD, 2020[14]).

What are the similarities between other transitions and the green transition?

The negative effects of other megatrends have been highly concentrated geographically making it similar to the green transition’s localised nature. For some areas, the green transition will provide employment opportunities in innovation, R&D and new forms of infrastructure planning. However, in other regions the green transition will be a bigger challenge, including regions where there is a large manufacturing, chemical or extraction industry.

Acting against the current wave of resentment towards globalisation and digitalisation requires decisive actions by governments and international organisations. Individuals in regions that are falling behind are increasingly dissatisfied with these megatrends. A lack of progress in addressing the widening of regional gaps in economic opportunities has been cited as creating public resentment. Certain communities and regions are increasingly sceptical of global developments and policy elites (OECD, 2019[15]; Krugman, 2018[16]). The main priority is ensuring that globalisation works for everyone. This requires the implementation of policies that ensure that benefits of trade, investment automation and digitalisation are widely shared. Tools to achieve such policies are social protection, labour market activation policies, and strategic investments in education, skills, health, innovation, and infrastructure (OECD, 2017[11]). Similarly, the green transition is also likely to increase divergence in development between regions and within them. If the green transition does not coincide with redistributive policies, support for a green agenda can diminish. Failing to address the geography of discontent could extend the current backlash to the green transition, making it increasingly difficult to build essential political coalitions.

Empirical evidence on effective adjustment and transition policies is relatively rare. To design targeted policies to combat structural adjustment failures and to assess their efficiency, empirical evidence is needed. However, very little empirical evidence exists on measures that work well (WTO, 2019[17]). There are still considerable gaps in the research and many questions remain unanswered. Little evidence on the overall effectiveness of adjustment measures (WTO, 2019[17]) is available. The same problem is encountered regarding the green transition. Much attention is devoted to making this transition a just transition, but little empirical evidence on effective policy is available to inform the debate.

The costs of adjusting to a new economic structure can be high and are often borne by specific workers. In the United States, research suggests that adjustment costs can be up to five times the annual wage of a worker (Artuç and McLaren, 2015[18]). Other research suggests that sectoral mobility costs are higher than regional mobility costs. In other words, it is sometimes easier for workers to leave a region to find similar work elsewhere than to stay and re-skill (Cruz, Milet and Olarreaga, 2017[19]). Given the fact that many vulnerable workers are unwilling or unable to move to another region, this can lead to increased regional inequality and erode social cohesion (WTO, 2019[17]).

Many past or ongoing transitions have led to skills-biased changes, requiring higher skills and leading to polarisation as well as increased inequality in the labour market. For example, in the move to a more digital economy, both middle skilled and decently paid low-skilled jobs have been decreasing due to the introduction of digital tools. This can be either because the work can be (partly) automated, thus requiring fewer workers, or because, due to the introduction of digital tools, employees now require a higher level of skills to complete tasks (Muro et al., 2017[20]) (OECD, 2020[21]; Warhurst and Hunt, 2019[22]). These effects put negative pressure on wages for low skilled and middle skilled jobs. Meanwhile, high-skilled digital jobs pay better than average wages, leading to increasing wage divergence. Similarly, so far, mainly high skilled workers are employed in green-task jobs and are paid higher wages as a result. Thus, in absence of effective re- and up-skilling systems, the green transition is likely to increase labour market inequality, just as digitalisation or globalisation has.

The digital transition and green transition are twin transitions, complementing each other. Smart resource management and smart solutions in industry can help polluting industries lower their carbon footprint. For example, digital tools can help lower the demand for energy in the steel industry (Branca et al., 2020[23]). Likewise, many green solutions and innovations require digital skills to be developed and to be used. Thus, green-skills and digital-skills often overlap, and occur simultaneously.

The supply of digital and green skills lags demand, which makes skills a major bottleneck. Almost all workers in almost every business, and every job in OECD member states need to be able to use digital tools (OECD, 2020[24]) (OECD, 2016[25]). This means that digital skills are essential in today’s labour market. Digitalisation is not only causing job creation and displacement but is also changing tasks most jobs require. A successful green transition will likewise require a shift in the way people work. Many workers will require a certain set of green skills to function in a green economy. However, a lack of digital and green skills remains a problem in most places. Many workers do not yet have the necessary skills to thrive in a digital environment. Reskilling the workforce is a bottleneck to realising the full potential of a digital economy. To overcome this problem, the initiative called ‘Training the trainers’ was designed to increase the quality and quantity of digital skills courses in southern Europe. The same initiative is now teaching trainers in the area of green skills.

How does the green transition differ?

Earlier and ongoing transitions are all largely market-driven, whereas the green transition will be primarily policy driven. In previous transitions, technological innovation allowed a niche technique to become more cost-efficient. In the case of past energy transitions, the old energy source experienced increased extraction costs, which made the new energy source a competitive alternative. The same is true for automation and digitalisation. In the case of globalisation, improved communication and transportation techniques made it possible to produce many goods offshore with cheaper labour costs. It became more affordable to produce goods or sell services and thus allowed the new and more efficient forms of production to become dominant over old techniques. However, for the green transition, despite rising prices of oil and natural gas, circular economies and renewable energy are unlikely to become dominant in time to fight climate change by relying only on market forces. Thus, current and past transitions differ, as policy will be a driving force in the green rollout (Fouquet and Pearson, 2012[8]).3

Globalisation largely coincided with deregulation, but the green transition is policy driven and might coincide with reregulation. Institutions at the forefront of globalisation such as the WTO, World Bank, and IMF often pushed for the lowering of trade barriers, tariffs and complex product regulations. Furthermore, many governments cut back on public spending and deregulated non-market orientated social programs and subsidies. The green transition is taking a different approach. In order to foster the development of the green economy, which is not yet competitive on its own in all areas, massive public spending is being allocated to green initiative to subsidise green innovation and production. Moreover, to ensure that the green transition is a ‘just’ transition some governments have rolled out large-scale welfare programmes.

Current environmental policies are insufficient for dealing with the global externalities of climate change and environmental degradation that affect most people. Environmental deprivation left unattended will have a drastic impact on public health and the economy. The positive and negative externalities of environmental policy are not appropriately costed in market mechanisms. The green transition has externalities that are beneficial for all. Successful green policy delivers broad benefits such as clean air, soil, and water, and consequently less extreme weather, natural disasters, and increased longevity. Globalisation on the other hand is, besides its achievements, also associated with negative externalities, such as global warming. Increased trade and consumption have put pressure on environmental preservation.

Digitalisation has a wider impact than the green transition on local labour markets, affecting the majority of OECD employment, whilst the green transition is not affecting most jobs yet. The green transition, like digitalisation, has the potential to change the tasks associated with many jobs. Digitalisation and digital tools have done so already. The number of tasks an average worker preforms using digital tools has risen drastically.

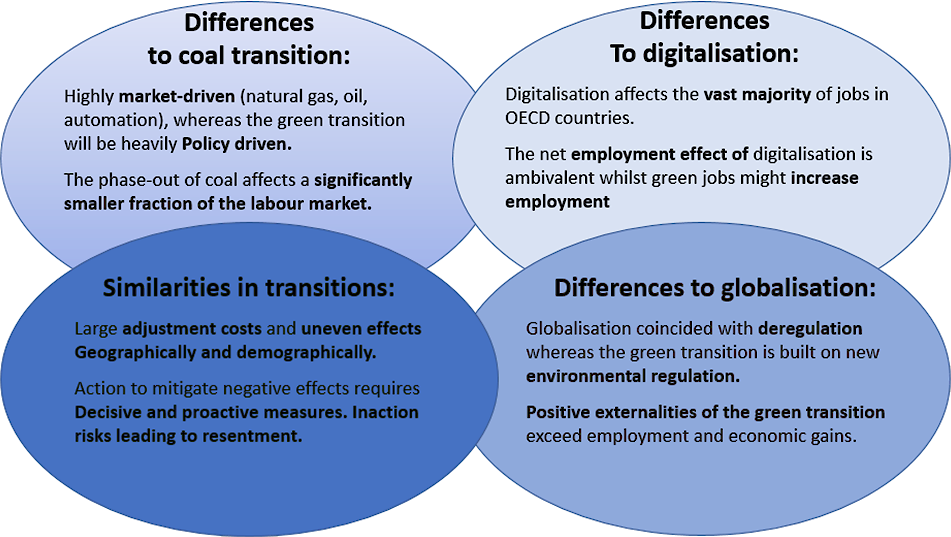

Figure 3.1. Similarities and differences: the green transition, globalisation, digitalisation, and the exit from coal

Source: Author’s elaboration.

The digitalisation transition

This section will look into the effects of digital tools and digital automation on the regional labour market. It will show that digitalisation poses a risk to certain occupations but offers many other opportunities. The case study of Estonia will show how economies can seize the opportunities provided by the digital transition.

What are the effects of digitalisation?

Digitalisation, defined as the process of introducing digital information technology and digital tools to transform business operations, is affecting most jobs in OECD countries (Muro et al., 2017[20]; Gartner IT Glossary, n.d.[26]). Though digitalisation is ongoing, over the last decade, developments have been so fast that many speak of the digitalisation of everything (Muro et al., 2017[20]). The penetration of digital technology into the world of work has been further accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, as many businesses resorted to e-commerce and remote working (OECD, 2020[24]). All of this has changed local economies, jobs, and the way we work and communicate.

OECD regions are increasingly connected to digital infrastructure. Between 2014 and 2020, the amount of high-speed fibre in OECD regions has more than doubled. Amongst businesses, the divide between small and large firms has narrowed as 93% of enterprises are now connected to a broadband connection (OECD, 2020[24]).4 This enabled a quicker and deeper integration of digital tools in the workplace, forcing employees to adapt to new work environments. One of the most extensive efforts to integrate digital tools into industry is found in Germany (see Box 3.2).

Despite increased coverage of digital infrastructure, regional discrepancies in digitalisation are widening. While disparities between OECD countries have decreased over the past decades, regional divergence within countries is generally worsening and remains large (OECD, 2018[27]; OECD, 2018[28]; OECD, 2019[15]). The digital frontrunners are increasing digital usage faster than the regions that are behind, pointing at a first mover advantage.5 Unsurprisingly, this is also reflected in wages, where workers in digitally-advanced regions earn more than workers in regions that are falling behind. Thus, this digital regional divergence has the potential to increase and exacerbate inequality (Muro et al., 2017[20]; European Commission, 2017[29]).

Automation risks driven by digitalisation have an uneven impact on different areas within OECD countries. Overall, risks of automation of jobs are more pronounced in rural areas and regions with a strong manufacturing base, whilst new job opportunities are found in urban areas (OECD, 2019[15]). Moreover, the sectoral composition of business that open in urban areas are more likely to be in knowledge-intensive industries which are less at risk of digital automation. Therefore, the shift to digitalisation not only generates greater employment opportunities in urban areas but also puts fewer jobs in urban areas at risk of displacement (OECD, 2019[15]). Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, without supportive policy, heavy hit regions take a long time to offset job losses by local job creation (OECD, 2017[30]).

Box 3.2. Industry 4.0, Germany

Industry 4.0

The German export industry cooperated on a national level to develop a strategy to stay competitive in an age of far-reaching digitalisation, which is believed to have spurred the advent of what is being hailed as the fourth industrial revolution (Arbeitskreis Industrie 4.0, 2012[31]; Spath et al., 2013[32]). At the core of industry 4.0 is a network in which machines, products, materials, and people are connected through systems of sensors, communication, and artificial intelligence (Kuhlmann, Wiegrefe and Spellt, 2018[33]; Hirsch-Kreinsen, 2018[34]; Haipeter, 2020[35]). Despite being a well-coordinated and thorough plan, in practise the results of the industry 4.0 network have found limited success. Survey data found that although two-thirds of firms had introduced software systems, only one-third used the integrated network for digital logistics. Furthermore, only 44% of the plants were digitally linked, 47% used automated production planning, 12% used AI to take over administrative tasks, and 16% utilised robotic assistants (Haipeter, 2020[35]). This showcased that many potential benefits of digital tools are hard to integrate, as companies and their employees are not always comfortable with their usage.

Arbeit 2020

Given that technology will change the way people work as well as industrial relations, trade unions face a choice between resistance or adaptation. Arbeit 2020, a plan developed by national trade unions in Germany, informs worker councils in companies about the changes and impacts of digitalisation to encourage negotiations and social dialogue between employer and employees. This strategy of cooperation was meant to make sure that workers were included, and their voices heard in the discussion on how to incorporate new digital tools. It clarified how digital tools are used by workers, in what way they are affecting work, and how they can help to create decent jobs (Haipeter, 2020[35]). National Unions also collaborated with universities to do research and gather experts that can help as consultants for local work councils that face challenges in introducing new digital tools (Haipeter, 2020[35]).

Work increasingly relies on digital skills.

Employment increasingly requires deeper knowledge of digital tools. Overall, high skilled jobs that already required far reaching digital knowledge got more complex. Moreover, many jobs that used to require medium digital skills are now evolving to highly digital jobs requiring increased skillsets. But most notably, many jobs in sectors that were not considered digital have rapidly integrated digital tools. Thus, the increasing importance of digital knowledge has transformed the workplace, and especially drastic in low-skilled occupations. (Muro et al., 2017[20]). Yet, some workers struggle to adapt to new digital work practises. Preliminary evidence suggests that increased digitalisation is causing increased stress amongst workers (Haipeter, 2020[35]).6

Strong digital skills are increasingly rewarded in the labour market. Longitudinal research from 1970s to 2000s shows that workers who use digital technology in their work are generally better paid and evidence from the US confirms a digital wage premium between 2002 and 2016 (Muro et al., 2017[20]). A lot of the effect can be attributed to general skills and education level of workers. However, even after correcting for those factors, digital knowledge still significantly relates to pay.

Displacement effect

Automation is causing job displacement. While pessimistic scenarios calling for the end of work are grossly overestimated (OECD, 2020[24]), automation does endanger employment in certain industries. Especially employment in routine non-creative tasks in manufacturing industries faces increased risk of being automated. Furthermore, the introduction of smart AI and digital resources is also replacing routine tasks in management work and service industries. These jobs often require a low or middle skill level. Yet, digitalisation does also stimulate growth in other industries, creating jobs in the area of social media.

There is no clear evidence of net job losses caused by automation. However, since such job losses are concentrated, they pose significant challenges for some regions and sectors. How much risk a region faces varies widely within a country. Regions that depend more on manufacturing will face the greatest challenges (OECD, 2018[28]). These regions require extra investment and policy to encourage job creation in low-risk industries (Muro et al., 2017[20]; OECD, 2018[36]; Warhurst and Hunt, 2019[22]). Even within industries and sectors, big regional differences in automation risks can be observed. For example, in Poland 78% of jobs in the textile sector, and 84% of jobs in the automotive industry are at risk of automation. In France, only 50% of employment in textiles is at risk, and only 30% of jobs in the automotive industry (Warhurst and Hunt, 2019[22]; Cedefop, Eurofund, 2018[37]).

Automation and new digital technologies mainly displace middle skilled and low skilled jobs. It simultaneously creates more high skilled jobs.7 This means that some individuals, especially those with tertiary education levels, will move to higher skilled professions. Others however will move from a middle skilled job into a low skilled job. This may put downward pressure on wages in low-skilled jobs. There has been a real wage loss observed for those workers who are not capable of working with digital sources. All of this is hollowing-out the middle pay segment and increasing polarisation in local labour markets (OECD, 2020[24]; OECD, 2018[36]; OECD, 2018[27]).

New forms of work

Digital forms of communication and interaction have given rise to new forms of work. A prominent example of work that emerged because of digitalisation is gig work or platform work.8 Services can be provided locally, such as ride hailing, housekeeping, or delivery, or completely digitally such as translation, design or clerical and data entry work (Charles, Xia and Coutts, 2022[38]; Biagi et al., 2018[39]; OECD, 2019[40]; OECD, 2019[15]; De Stefano, 2016[41]). In OECD countries, the share of workers who depend on platforms as their main income is small9, but expected to grow in the future.10

Despite platforms being a global phenomenon, there is a regional angle to it. Globally, the platform economy is largest in metropolitan and capital rich regions. (Warhurst and Hunt, 2019[22]; Graham, 2017[42]). However, within the OECD, some more scarcely populated regions including, amongst others, the Baltic states, the Czech Republic, have been able to attract platform work and workers by creating a good environment for digital nomads.

What are the local drivers of successful policy for the digital transition?

Provide workers with the right skillset for the digital transition, which is essential for local economies to thrive. The increased use of digital technologies in almost every sector and industry as well as the rising number of jobs qualifying as ‘highly digital’ show the need for digital skills in the workforce (Muro et al., 2017[20]). However, 50% of the workforce does not have more than very basic digital skills,11 or no digital skills at all (OECD, 2019[43]; OECD, 2019[15]). Therefore, policy should prepare for a massive upskilling of the workforce in line with local labour market demand. Moreover, improving cooperation with relevant stakeholders can lead to increased quality of education and vocational educational training (VET) curricula. This policy should focus on regional needs. How trained the general workforce is with digital tools varies per region. It is important that lagging regions invest extra in catching up as a divide in digital knowledge can lead to further divergence in regional prosperity.

Prepare workers for the digital world of work, by boosting ICT and digital skills for some, but also a wide variety of non-digital skills for many others. Each region or industry requires its own digital skillset. Demand is increasing for high skilled ICT workers, and workers with high levels of digital skills but in different ways in different places. For some regions, it is important to invest in the availability of highly skilled digital workers to capitalise on economic potential. However, for most regions and most workers, increasing knowledge of how to function in an increasingly digital environment is equally desirable. This requires a wide range of skills, including transversal skills. Tasks such as browsing the web and finding credible information is increasingly difficult in an age of information overload. Completing basic digital tasks requires digital knowledge but also solid reading and calculation skills, cognitive intelligence, and socio-emotion abilities (OECD, 2019[43]). It is important that regions map the digital skill demand to be able to offer the right training. Regional actors should determine how much training should focus on complex ICT skills, and how much on general usage of digital tools.

Increase interest and participation in local adult learning to accelerate re- and upskilling. The task of re-skilling and re-training is large. Thus, early and voluntary attendance is required to ease the organisation and logistics. Interest in digital skill courses can be increased by using awareness campaigns that promote the benefits of training. Furthermore, these campaigns can work to increase how directly wages correspond to productivity gains as a result of training participation (OECD, 2019[43]). Lowering barriers to participate can also increase interest. Currently, barriers exist such as: (i) financial, which can be resolved by beneficiary tax schemes, (ii) time, which can be resolved by increasing the flexibility of training hours, (iii) or sustainability, which can be overcome by making training certificates better transferable between employers and industries (OECD, 2019[15]). Regional actors can utilise knowledge of regional digital skill demands to advertise skill courses that best fit the regional needs and thus are more directly applicable in local communities.

Expand the use of digital tools in early education. Digital learning holds many benefits over conventional teaching methods. Benefits include such things as: (i) better and more flexible access to study materials; (ii) better tools to facilitate collaboration amongst children and students, thereby increasing social skills; (iii) easier methods to personalise learning experiences and increase engagement; (iv) and increased transparency to track progress. Providing courses where teachers can learn how to reap the benefits of digital learning tools will lead to better education, and increased digital knowledge among children, students, and teachers (OECD, 2021[44]). Furthermore, digital education provides participants in remote areas with the opportunity to take courses offered only in bigger educational institutions. Digital cooperation can allow regional schools to connect to a main facility, thereby providing education that would otherwise be impossible to facilitate in some areas. While digital attendance cannot fully replace in-person training, a hybrid model can increase the quality, quantity, and range of courses offered in less populated areas.

Learning from Estonia: seizing the benefits of digitalisation

Estonia is one of the most digitally advanced countries in the world. After breaking away from the Soviet Union, the Estonian economy rapidly modernised. Since 1991, digitalisation has been a vital part of the Estonian strategy for economic development. Today, Estonia ranks 7th in the EU Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), above more advanced economies such as Germany and France, and 20th in the IMD world digital competitiveness rankings, one place below Germany (19), and above Japan (29). This is also much higher than most other eastern European countries, many of which lag behind their western and northern counterparts (IMD world competitiveness centre, 2022[45]; European Comission, 2022[46]). This high score in digitalisation has enabled Estonia to excel in the digital economy. To illustrate this point, in the OECD, on average, 9% of jobs are at risk due to digitalisation, in Estonia this is only 6% (OECD, 2017[47]).

The Tiger Leap initiative was designed to establish Estonia as a global digital frontrunner, with a special focus on technology in education. The Estonian government in 1996 wanted to consolidate Estonia with a strong tech industry. Their philosophy was that Estonia, after soviet rule lagged behind in many areas, but the internet was new, and thus in this industry they did not have to catch up. In the 1997 Tiger Leap Plan, digital tools were given a central role to play in Estonia’s development into a competitive modern economy.

The Estonian Tiger Leap had a special focus on education. In Estonian education, both teachers and students work with digital technologies. Teachers attend classes on the optimal usage of digital teaching tools. This has led to deep integration of such tools in schools. Over 70% of kindergartens, and over 90% of schools make use of digital tools in their teaching methods. This strategy was recently modified, which should lead to over 90% of 16-24-year-olds having above average digital skills (European Comission, 2022[46]).

Tech industry and start-ups contribute considerably to the Estonian economy. Considering the country’s size, it is noteworthy that companies like Skype, TransferWise, Playtech, and Taxify (Bolt) all originated in Estonia. Around 6,2% of the Estonian workforce is working in ICT-jobs, significantly higher than the EU average of 4.5%. Estonian ICT exports have also risen consistently, recording a growth of 108% between 2015 and 2022. The ICT industry is responsible for 7% of national GDP. Estonia’s early adaptation to and embrace of digitalisation has allowed the country to seize its benefits and job creation opportunities.

Estonia ranks first in the DESI E-government index. Almost all Estonian citizens use electronic tools provided by the government to streamline both government services (such as taxes) and business operations by providing an open and transparent database and tools for reliable e-signatures. Taken together, the smoothing of these processes is believed to increase Estonian GDP by 2%.

Digital nomad visa and E-residencies have attracted many start-ups and entrepreneurs to Estonia. With the help of E-residency, entrepreneurs from over 176 countries have been able to establish a business, or an EU business branch in Estonia. Over 30% of Estonian start-ups have E-resident amongst their founders, and 20% of companies registered annually in Estonia are created by E-residents (Petrone, 2022[48]). Over a 100 000 people today are registered in Estonia on E-residencies, making it a large part of the population of 1.3 million. The introduction of this transparent and accessible visa has had a major positive impact on Estonian economic growth.

The transition towards a global economy

This chapter will look at the effects of globalisation and outsourcing on the regional labour market. It will show that globalisation has increased net output and economic growth. However, it has also posed risks to certain occupations and regional economies. These risks, if unmanaged, can lead to further regional economic divergence. The case study of Oulu will show how economies can seize opportunities that globalisation is creating.

What are the effects of globalisation?

The impact of globalisation differs across countries and amongst regions within countries. For some countries, globalisation increased trade, information exchange, the availability of capital, and a strong rise in innovation. (Zeibote, Volkova and Todorov, 2019[49]). Trade has led to growth and lifted millions of people out of poverty (OECD, 2022[50]). However, some countries have faced challenging transitions as local businesses lost out to global competitors. Within countries, the costs and benefits of open trade policy and deregulation are not equally shared. In developed economies, some areas dependent on manufacturing have seen the disappearance of important employers without equivalent alternatives (OECD, 2007[51]). Other regions witnessed an increase of high-skilled service demand and steady GPD growth (Stiglitz, 2002[52]; OECD, 2017[11]). In Europe, the benefits of globalisation for the EU have been widespread, whilst the costs were often geographically concentrated (European Commission, 2019[53]). In the US, regions that traded a lot with China recorded greater job losses in manufacturing than regions with lower trade exposure to China (Pierce and Schott, 2016[54]; Autor, Dorn and Hanson, 2013[55]). In many cases these jobs were replaced by jobs in the service industry, requiring a different skillset. Hence, amongst different people with varying levels of skills the impact of globalisation was also diverse. High-skilled individuals were often more resilient and managed to adapt, whilst low-skilled individuals especially in the worst-hit regions struggled to adjust (WTO, 2019[17]).

What are the local drivers of successful policy for globalisation?

Monitor the demand for and supply of skills at the local level, to ensure matching. To create better employment, a holistic approach is required. Just upskilling is in many cases not enough, as there might be a low demand for high-skill jobs. An integrated approach is therefore required. This involves creating incentives for workers to partake in upskilling programmes. In addition, investments in innovation, technology and business development are required to allow firms, especially SMEs, and local employers to create jobs for higher-skilled individuals (OECD, 2014[56]; OECD, 2016[57]). This requires better coordination in investment, innovation and labour market policies at the local level (OECD, 2019[58]).

Proactive initiatives can increase institutional trust and decrease negative economic effects of structural adjustment. If a clear and holistic restructuring plan is presented to workers before they are made redundant, their level of institutional trust might be salvaged, which could motivate them to participate in re-skilling programs (Bailey et al., 2008[59]; Bailey et al., 2014[60]). Furthermore, this type of strategy can mitigate the negative economic effects of industries that are being shuttered (see Box 3.3) (World Bank, 2022[13]).

Engage with a wide range of local stakeholders to get a full grasp of the skills that are needed in the workplace. Local training associations, employers, universities, unions, and civil society actors, often hold much expertise, knowledge and resources regarding the local labour markets. Actively engaging with those stakeholders can improve the identification of skills gaps. If done properly, successful dialogue among stakeholders at the local level can lead to swift and targeted rollouts of up-skilling programmes. Such dialogue requires an active and leading role by regional policy makers (OECD, 2019[58]). This could help identify areas with a high concentration of low skilled and low paid jobs, which is often referred to as a low-skills equilibrium. Furthermore, understanding skills mismatches, either a skill surplus or a skill deficit, is vital to determine whether the focus of future policies should prioritise the investment in skills supply or demand (Froy, Giguère and Meghnagi, 2012[61]).

Look critically at niches to exploit opportunities and comparative advantages of communities and regions. Local governments can assess available skills and ensure they are properly used by local employers. Often, the presence of dominant industries has created infrastructures and knowhow in a specific region of a country. Exploring options to make use of the existing human capital can attract new industries and employers efficiently, and lower adjustment costs. However, the existing skills may be used in new industries. Supporting old industries can cause a harmful lock-in effect. Injecting public credit into ailing business models and outdated technologies is not a sustainable model to boost local employment (OECD, 2019[58]).

Invest to improve the quality of education to foster adoption of new technology and increase resilience and adaptability in communities. There are both market and non-market benefits of good quality education provision. Industrial transitions such as globalisation, and the green transition, require workers to adapt to new circumstances and work with new technologies. Quality initial education and return-to-school policies can help ease the transition to new work opportunities. Active labour market policies provide workers with additional skills that they will need to stay competitive and engaged in emerging sectors. However, good initial education increases the effectiveness of such policies as participants will be quicker to learn new skills, increasing the adaptability and resilience of the general workforce (see Box 3.4) (Heckman, Humphries and Veramendi, 2018[62]; WTO, 2019[17]).

Improved connectivity between urban and rural areas can strengthen the labour market. SMEs and local employers in rural areas benefit from an inward- as well as outward-looking strategy. This can allow local businesses to overcome the problem of remoteness. Connecting local entrepreneurs with resources and strategic actors in urban areas can increase access to knowledge and foreign markets for SMEs in more remote areas. This can be done by creating start-up boot camps, innovation hubs, or similar initiatives (OECD, 2019[7]).

Learning from Oulu, Finland: excelling amid globalisation

In Oulu, external forces led to the collapse of Nokia as an employer in the region, but today employment is higher than before. The information and communication technology (ICT) cluster led by Nokia was vital to the Oulu regional economy. At its peak, Nokia was the world market leader in wireless and mobile ICT, and 16% of regional employment depended on its success. Due to increased globalisation, regional development is now increasingly prone to external shocks (Martin and Gardiner, 2019[63]; Simonen et al., 2016[64]). In the span of just a couple of years, Nokia lost market share to Apple, Samsung, and other producers. This caused a drastic reduction in the Nokia workforce in the Oulu region. However, thanks to an approach based on knowledge creation, entrepreneurship, and communal spirit, employment is now higher than ever. Policy makers had a strong focus on measures exploiting the regional cooperation network and existing human capital that became available because of the Nokia collapse (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]).

The success of a single industry in a region can foster complacency and reduce resilience to large-scale shocks. The growth of Nokia was mainly in the specialised sector of manufacturing of mobile and wireless communication devices. This made the economy of the region overly dependent on the success of one company. Easy and successful collaboration with Nokia caused many subcontractors to ignore global business strategies. Between 2008 and 2014, Nokia, its successor Microsoft, and Broadcom, had all downsized causing the unemployment rate in the region to jump to 18% (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]).

Local and regional actors formed alliances to anticipate the economic downturn. Essential local actors anticipated the massive structural changes that occurred between 2009 and 2014. Many actors created coalitions to coordinate structural adjustment and economic diversification at the local level. The Oulu Innovation Alliance (OIA) was created in 2009,12 pledging to invest in agreed areas, concentrating on diversification of expertise in the tech sector. Another important alliance was the Tar Group,13 which functioned as an informal discussion platform for all relevant stakeholders in the region. They oversaw the funding made available for structural adjustments. Tar Group decided to fund new agents and to avoid subsidising outdated business models. Moreover, business development was reorganised into BusinessOulu, a strategic hub for boosting start-up-ecosystems in the area. All coalitions showed the willingness to take risks. This facilitated a start-up boom, in which over 600 start-ups were created (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]). Finland made good use of the European Globalisation Adjustment fund to finance employment and innovative initiatives (OECD Local Development Forum, 2022[66])

High standards of infrastructure and quality of life avoided mass outmigration of highly skilled workers. Despite the high unemployment rates, and economic downturn between 2008 and 2013, only about 200 out of the 3 500 recently unemployed workers decided to leave the area, reflecting the local population’s willingness to remain in the area (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]). This is partly due to the presence of high-quality transport infrastructure, education institutions, and healthcare services. In return, the presence of a high-skilled and available workforce attracted some businesses to the area (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]). Preventing outmigration of the working population provided the region with the skills needed to fuel the success of other firms.

The high average level of education of the population in Oulu increased workers’ resilience and adaptability during the downturn. The high degree of specialisation in the Oulu region initially made it hard for employees to find new job opportunities. However, education levels, which are in general quite high, facilitated a smoother transition from high-tech manufacturing to the high-tech service sector. The presence of related industries in a region also improves the likelihood that workers will find new work (Hane-Weijman, Eriksson and Henning, 2018[67]; Boschma, Eriksson and Lindgren, 2014[68]). Regional authorities realised the potential of the recently laid-off highly skilled workforce. This was both a challenge and an opportunity as PES had to learn to work with this type of redundant workers. The initial mentality is that those highly skilled workers can manage well for themselves. However, with the number of redundancies in Oulu, this became problematic (OECD Local Development Forum, 2022[66]). The Tar group was responsible for developing re-skilling programmes reflecting a variety of aspects, including the interests of employees, the expertise of education centres, and demand from employers. For this reason, education was fitted towards areas in which new jobs would emerge, reducing the risks of unemployment (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]). As a result, the high-tech sector of Oulu is more diverse. SMEs are much more independent and no longer live off the success of Nokia on the international market. In other words, a shock to the essential member of the regional economy does not affect all industries to the same extent as it did in the early 2000s (Crespo, Suire and Vicente, 2014[69]). The Oulu region has bolstered its resilience considerably, and its resistance and robustness to potential external economic shocks (Simonen, Herala and Svento, 2020[65]).

Box 3.3. Building institutional trust among affected workers, by acting swiftly. West-Midlands, (United Kingdom)

The Midlands in the UK is one of the regions that have faced both gradual and sudden layoffs in car manufacturing resulting from supply chain relocation or automation between 1960 and 2008. During the 1960s, the car manufacturing and dependent industries comprised 65% of total employment in the wider West-Midlands. Ever since, their share of employment has been shrinking. Between 2005 and 2009, several large employers shut down their production, including Jaguar and Peugeot (Coventry, 2006), MG Rover (Birmingham, 2005) and LDV (Birmingham, 2009). Overall, the industry witnessed a 34% employment reduction between 1997 and 2007, with spill-over effects in other industries.

After setbacks related to the financial crisis, the industry grew again between 2011 and 2018. With an increase in output production by roughly 50% and employment by 18.6%, the automotive industry is regaining importance as an economic engine in the midlands. Moreover, electric vehicles increasingly contribute to this growth.

Between 1997 and 2010, the UK government set up multiple taskforces to cope with car manufacturing plants closing down. The government used temporary, non-statutory partnerships with multi-stakeholders and selective membership taskforces as a response to regional shocks caused by car manufacturing closures. The aim of such taskforces was the rapid mobilisation of expertise and resources of national and regional stakeholders in response to the economic challenges.

In Birmingham the high geographic concentration of manufacturing jobs made the region vulnerable economically. At the time of the collapse of the Longbridge plant in Birmingham, it provided more than 6 000 jobs. An estimated 12 000 jobs in the automotive industry and their dependant suppliers were expected to be lost.1 Moreover, the jobs lost in the car manufacturing industry were relatively good jobs, paying a weekly salary of GBP 514 compared to the regional average of GBP 404 for a full-time worker. The unemployment rate in 2008 in Birmingham (9.4%) was the second highest in the UK, making economic policies in this region particularly challenging.

The regional government took a proactive stance and set up diversification and adjustment programmes early on. Programmes incentivising economic diversification started in the early 2000s, as a response to a decline in manufacturing employment. To deal with economic shocks, such as the carmaker MG Rover’s shutdown, the workforce was incentivised to be more resilient before they lost their jobs. Regional stakeholders made efforts to ensure that employees had the necessary skills to cope with industrial change by providing flexible training, education, and information programmes. Thanks to this early intervention, many workers were already reskilled and replaced before the final shutdown, limiting its negative effects.

Authorities created a multi-stakeholder taskforce named Second Rover Taskforce (RTF2) that was mandated with securing re-employment.2Objectives of the task force were: (i) keeping suppliers operational in the short term, whilst supporting and assisting diversification, (ii) aiding those suffering from joblessness to find new work, (iii) supporting the local community.3 The funding for the diversification programme of MG Rover’s suppliers was effective. As MG Rover collapsed, 4 000 fewer jobs than originally forecast were lost, both in the short and long term.

Despite the challenging situation, 90% of the MG Rover employees found employment by 2008, albeit often for lower wages. Yet, after three years, 90% of the ex-MG Rover employees found some form of employment.4 At first sight, the policy approach created for MG Rover employees was thus very successful. However, the need to acquire an entirely new skillset resulted in significant wage loss, GBP 5 640 annually in real terms by 2008. Two-thirds of the workforce suffered wage losses, whilst one-third reported an increase.5 High-quality manufacturing jobs are not easily replicable, especially if skills do not transfer well into new employment. In general, reusing available skills is more effective. However, skills reproduction in this case would require continuity in skills demand, which can be unlikely in the long run.

The availability of training has helped workers both in acquiring skills to switch sectors and in providing the tools to look for new opportunities. Many workers who moved from manufacturing to the service sector required an entirely new skillset. Among them, 60% had undergone some form of education or training course. Two-thirds of them utilised the training schemes offered by local agencies, whilst many others underwent training in their new workplace. Workers reported that training helped them gain confidence to find new employment. Moreover, roughly one-third of workers had managed to upskill, reporting a higher occupational level than at MG Rover. Yet, another third reported a lower occupational level.

The swift and resolute response helped retain employed people, motivate unemployed workers to participate in programmes and build trust in the adjustment policies. In the immediate aftermath, the public employment service brought 160 extra staff members to the Longbridge office, in order to register more than 5 000 employees eligible for benefits within a week. The RTF2 was operational the day of the closure announcement. Such preparation builds confidence in the organisation by those negatively affected. In comparison, a “firefighting” approach after the fact might have resulted in suspicion or lack of confidence in the taskforce, significantly lowering motivation to utilise the assistance provided.

1. In this similar timeframe, the US, Australia, Germany, France, Belgium, and Japan have all seen closures and mass layoffs in the automotive industry.

2. In this task force, there were members from different levels of government as well as different regions. Agencies represented included the Department of Trade and Industry, local members of parliament, local authorities such as the city council of Birmingham, employers, trade unions, skills agencies, and universities.

3. To this end, GBP 176 million was made available. GBP 50 million for retraining and upskilling, 40 million for redundancy payments, 24 million in the form of loans to dependent businesses, 21.6 million to help suppliers diversify and maintain trade, and 40 million to sustain suppliers trade in the short term.

4. Of these workers, 11% were self-employed, 5% percent part-time employed, and 5% percent still unemployed and looking for work.

5. These were mainly workers that found new work in manufacturing and thus did not need to change sector.

Box 3.4. Leveraging existing comparative advantages to create a global industry in Riviera del Brenta (Italy)

To overcome competition from cheap labour in the global market, the Riviera del Brenta area in the Veneto region capitalised on the “Made-in-Italy” brand to capture high-end markets for textiles. The Riviera del Brenta area had traditionally traded on the global markets in medium-range quality textiles, clothing, leather and footwear (TCLF) products. The low- and mid-tier fashion industry in developed economies faced increased pressure from trade liberalisation and cheap labour in the developing world. To stay competitive, Brenta effectively skilled up and became a leader in high-quality TCLF design and production with a focus on leather footwear and accessories, utilising the Made-in-Italy brand to their advantage. Due to greater value added in this segment of the industry, the region could absorb the higher labour costs. Manufacturing, which had dominated employment, dropped to 50% of total employment in design and only 40% in manufacturing during the process.

Bundling local resources allowed employers to market the high quality of the region’s products. The challenges and barriers experienced when entering a new global market are sizeable. The employers’ organisation Associazione dei calzaturieri della Riviera del Brenta (ACRIB) played a decisive role in expanding the brand of the Brenta district. The ACRIB functions as a representative body for employers in wage negotiations and in expanding the brand name globally. Furthermore, the ACRIB also became a hub for sharing business innovation ideas. Combining local resources allowed producers to afford the costs related to entering the global market.

Local education and training institutions played an important role in upskilling the labour force, allowing the transformation to higher value-added market strategies. Originally, the region had a strong craftwork tradition based on informal knowledge transfer. The school of arts and crafts gathered informal knowledge to codify and institutionalise their traditions. In 2003, a public-private partnership funded the institute to evolve into the Politiecnico Calzaturiero. This institute specialised in footwear design, and helped promote initiatives in training, research and technological transfer, development and operational safety. The school enjoyed: (i) a strong tradition exploiting the two hundred years of experience in the region, (ii) cooperation with the private sector, regional governments, and unions, (iii) employing teaching staff comprising entrepreneurs, stylists, designers, experts and workers, and (iv) a strong integration of the offered training courses with increases in skill utilisation and demand. The multi-stakeholder setup of the institution reduced entrepreneurs’ fears of sharing knowledge with regional competitors. This widespread knowledge sharing was fundamental in establishing regional quality control and entering the global high-end market.

Regional unions allowed workers to benefit financially from up-skilling, creating incentives to pursue training. The higher value added in high-end markets allowed for bigger profit margins. Unions negotiated so that such increases in margins went hand-in-hand with increases in wages, benefits, and improved working conditions. As productivity in the industry increased, so did the prosperity of the workers. The strong relationship between the Unions and the ACRIB established the idea that workers and employers both shared in the success of the industry creating incentives on both sides to maintain the high-quality standards.

A tripartite approach helped align the interests of different stakeholders and create the necessary coalitions to manage the difficult economic adjustment processes. Despite the upskilling and rebranding of the region, job losses to Romania and China were still significant. Combined with the financial crisis and increased pressure from automation and digitalisation, many former leatherworkers found themselves unemployed. A pact, formed by the regional governments, employers and unions, with the common goal of better reintegrating former leatherworkers, youth and women into the regional labour force helped tackle these problems. The pact promoted better skills utilisation. However, temporary forms of employment doubled in the area between 2004 and 2012. This development is problematic as there is a strong relationship between adult learning, training, and skill utilisation to the nature of employment contracts.

The transition out of coal

This section will look into the effects of automation, competition, and renewable energies on the coal industry. When societies wean themselves off coal, it often has far reaching consequences as coal generally provides well-paying jobs in economically challenged regions. The case study of the Ruhr region will show that managing such a process well can lead to sustainable economic growth in former coal regions.

What are the effects of phasing out coal?

Phasing out coal is an ongoing transition that is part of most OECD countries’ policy to achieve net zero in 2050. Due to a combination of climate goals, automation and innovation, and competing energy sources, much coal employment in OECD countries is already lost. The trend of phasing out coal is likely to continue as globally, 21 countries have pledged to phase out coal (International Energy Agency, 2021[72]). Some evidence suggests that the coal phase-out will yield substantial local health and environmental benefits that might outweigh the loss of economic activity in the extraction industry (Rauner et al., 2019[73]).

The outsized impact of coal mining jobs in small and/or remote communities makes them vulnerable to significant displacement in the event of mine closure, which poses a risk of destabilising local economies. The costs of phasing out coal are strongly geographically concentrated. Energy transition in coal regions will impact workers directly engaged in mining operations and along the coal supply chain, but also workers with indirect connections to coal activity, such as retail, restaurants, and recreation service providers to coal miners and their families. In this context, government planning is essential to mitigate the negative effects on livelihoods and the sustainability of local economies. Where coal is an important employer, political considerations can delay the energy transition, but delays may in fact increase existing distortions and exacerbate segmentation, making future transitions even more challenging (World Bank, 2022[13]; OECD, 2022[5]).

Direct unemployment due to the exit from coal can lead to larger spill-over effects. The level of coal mining jobs in OECD countries is modest, but the effects of phasing-out coal might include job losses in complex coal supply chains and dependent communities and industries. The effect and range of job losses outside the industry itself is significantly harder to calculate as little data is available (World Bank, 2022[13]). Research has shown varying estimates of the size of those ripple effects of losses of coal mining jobs, ranging from less than one to almost four other jobs lost per mining job. Coal mining jobs often provide economic stimulus to otherwise underfunded remote areas, many of which have above average poverty rates (OECD, 2021[74]).

So far, most policies have focused on miners themselves. Many policies for regional labour market transitions fall short of including workers that are dependent on coal further down the supply chain or in coal communities (World Bank, 2020[75]).

Economic diversification is essential for managing a transition successfully. A commonly observed mistake is that many regions support existing industries in a vain attempt to cling to current employment configurations. This can cause a lock-in effect, in which a too strong focus on current business and employment causes capital to flow into the dominant industries. Market forces or the desire for a clean environment are likely to make many of those industries obsolete in the long term. Investments in ailing industries such as clean coal are not future proof. Economic diversification of the region and the development of new industries increase the resilience of regions in the long term. Successful diversification requires proactive planning, investment in infrastructure, and attracting private investment. Institutional capacity is vital to effectively execute complicated strategies involving a multitude of stakeholders (World Bank, 2020[75]; OECD, 2022[5]; OECD, 2019[76]).

What are the local drivers of successful policy for the transition out of coal?

Clear, ambitious, actionable, and anticipatory policies with a long-term vision, can help to build strong coalitions and gain widespread support. For many businesses, especially those in heavy industry, structural adjustments require large-scale investments. On an individual level, re-skilling bears high transaction costs that will only pay off in the long run. Both for business and for individuals, clarity is needed about where economic opportunities are going to be, in order to make relevant long-term investments. This also means that different levels of government, vertically as well as horizontally, need to agree on objectives and ambitions. At the sub-national level, there is a need to stipulate in a clear way what the ambitions and policy objectives are in a region, this was done well in Spain for instance (Ministery for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challange, 2020[77]; Instituto para la Transición Justa, 2022[78]).

Consolidate collaboration among stakeholders operating at different levels of government. Helping regions to shift to a different economic structure requires commitment at all government levels. It is important that on a national level, there is a clear and proactive ambition. This includes well-communicated goals and a matching budget to achieve those goals. It also requires good organisation and cooperation on a regional and local level (see Box 3.6). In particular, investments in new industries and the exploitation of local comparative advantages are increasingly successful if communities have a strong say in their future direction (Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]). Not only different levels of government but also different parts of government (e.g., ministries of environment, energy, infrastructure, education, and finance) may cooperate and align their objectives in making a coherent plan (International Energy Agency, 2021[80]).

Invest in strengthening local re-skilling and up-skilling programmes. The extent to which employees and regional economies are capable to economically diversify depends on the success of re-skilling and re-education programmes (Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]). Local, bottom-up organised training to leave brown industries are necessary to: (i) help most affected workers transit into new career opportunities, (ii) make the human capital needed for the green transition available, (iii) include more disadvantaged groups in new emerging sectors. To mitigate the economic effects of phasing out coal, a long-term focus is needed on reskilling and re-skilling coal communities (International Energy Agency, 2021[80]; World Bank, 2022[13]).

Set up responsive career guidance to help workers identify sustainable career alternatives. It is often very unclear for former coal industry workers to identify sectors where ‘future-proof employment’ is likely to be found. Unemployment agencies, employers and educational institutions can work together to create easily accessible and relevant information for workers. Initiatives could include career fairs, networking events or personal counselling services (see Box 3.6). Career guidance can help streamline re-employment as workers can acquire the skills they need for future work security (OECD, 2019[81]).

Include workers and their communities in the process of structural changes to create strong coalitions and bolster effective social dialogue. Workers and employers can organise a transition much more smoothly if they work together (ILO, 2016[82]). Employees value an early and open conversation in good faith, in which they are provided with the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process concerning their future (Sartor, 2018 p.27 in (Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]; World Bank, 2022[13]). Social dialogue can be established by directly talking to workers, or by regular contact with workers’ representatives. Other stakeholders, such as unions, employers, as well as academics, wider communities and youth could be involved in the process (International Energy Agency, 2021[80]). When done well, sites can be closed, either slowly or more quickly, without creating major social or political unrest. Alternatively, if employees are not heard, and their needs unmet, it could result in distrust towards political coalitions and the decarbonisation process (Abraham, 2017[83]; Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]). In Spain, coal phase-out strategies have been designed in collaboration with worker representatives, which have largely been pleased with the outcome (see Box 3.5) (Ministery for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challange, 2020[77]; Instituto para la Transición Justa, 2022[78]).

Continue or boost local investment to avoid mass outmigration of workers. This does not only entail investing in universal infrastructure such as transportation (road, rail, air and water), but rather general investments in quality of life in regions. This includes education, healthcare, and public spaces such as cultural heritage sights, national parks and sport facilities. If an area remains attractive despite its economic downturn, an exodus of human capital can be avoided. If the workforce remains in the area, employers will be better able to regroup and avoid further impoverishment of the area. Furthermore, tailored investment in infrastructure supporting SMEs and start-ups can help offset a lack of sufficient capital, capacity and resources that more remote areas might experience. If workers with relevant skills leave the area where they work, a regional economy might implode (see Learning from Oulu, Finland: excelling amid globalisation).

Assist laid-off workers with unemployment aid packages. Opinions on aid packages are mixed. There is almost unanimous agreement that a form of wage-loss compensation is desirable. However, compensation will likely not be enough on its own. If coal miners are given severance or unemployment compensation that is on par with their wages, then they will have little incentive to switch careers, because—as mentioned previously—wages in the coal industry tend to be relatively high. In some cases that mimic the example above, 35-46% of former coal miners exited the labour market rather than undergoing reskilling and re-employment, causing a significant loss of both tax money to pay benefits and human capital in the local labour market (see Box 3.6) (World Bank, 2022[13]).

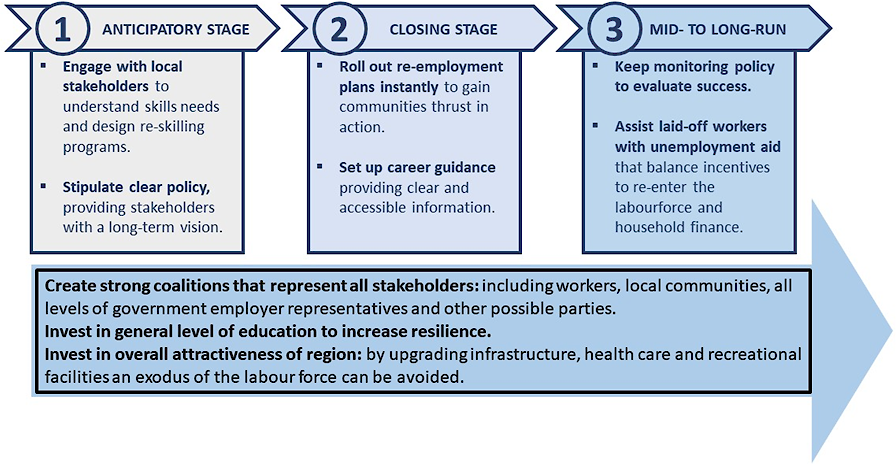

Figure 3.2. Introducing the right policy at the right moment is essential

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Learning from the Ruhr, Germany: successfully phasing out coal

The Ruhr, an essential area for European industry, produces large quantities of coal, steel and chemical products, but offers valuable insights into dealing with structural labour market changes. The Ruhr has a long history of coal mining and steel power plants dating back to the industrial revolution, which made it a centre for extraction and heavy industry. Between 1957 and 2016, the workforce in the coal extraction industry declined from more than 600 000 to less than 6 000, due to automation and large productivity gains and competition from other energy sources. These factors made many workers obsolete (Institut Arbeit und Technik, 2019[84]). While the Ruhr is still reliant on heavy industry, there are many jobs in chemical, steel, and aluminium production (Rhine-Westphalia, 2021[85]). Between 1960 and 2001, 839 000 jobs disappeared in the heavy industries, but they were compensated by 801 000 jobs that were created in the service industry. Moreover, by the mid-2000s, the R&D sector grew, thanks to the creation of 100 000 jobs. By 2009, 24 000 people worked in one of the 3 400 companies specialising in renewable energy, creating a total revenue of EUR 7 billion (World Resources Institute, 2021[86]; Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]).

In the late 1980s and 1990s, policy makers allowed more space for local actors, resulting in a more bottom-up, or regionalised policy approach. The 1970s saw a steady decline in coal-related employment. At first, German government agencies responded with top-down structural policies.14 Policy makers did not sufficiently include the representation and interests of smaller actors in the region. Industries were reluctant to recognise the decline of resource-based production and together with unions lobbied for large-scale investment to maintain competitiveness. This approach hindered efforts of structural reforms and thereby caused a harmful lock-in effect. Later, trade unions started to recognise the inevitability of a gradual phasing-out of coal employment due to a combination of emission reduction goals and market-driven factors. This provided an opportunity for local actors to engage effectively, leading to the adoption of a bottom-up approach. A good example is the creation of the International IBA Emscher Park, where local initiatives could combine public and private input and resources to start new business, scale-up existing ones, or design climate projects. This park led to the creation of 5 000 new jobs in the region (Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]; World Resources Institute, 2021[86]).

Putting education at the centre of long-term employment allowed the Ruhr area to become a frontrunner in renewable energy production and green industry technology. In the 1960s and 70s, there was a common belief that the Ruhr “did not need brains, it required muscle” (Galgóczi, 2014[87]). Between 1990s and 2014, large-scale investment in education, especially aimed at youth changed this image. The Ruhr area exploited its large urban population to create a knowledge hub for the chemical and green industries. By 2014, the Ruhr area had 22 universities with more than 250 000 active students. The large investment was very successful in creating a high skilled workforce that built an innovation-led economy, attracting companies and new employment (Institut Arbeit und Technik, 2019[84]).

Investment in education was supplemented by regulation and subsidies encouraging the development of innovative industries. As early as the 1970s, the German administration tightened laws on environmental policy. This caused the dominant industrial employers of coal, steel and chemical production to take an interest in environmental innovation. In the early 1980s, policy makers made broad investments in infrastructures to avoid mass outmigration and large-scale human capital flight. Investments were made in cultural development to maintain the Ruhr identity, urban and rural planning, ecological preservation for recreational use, and transportation infrastructure (McMaster and Novotny, 2006[88]; Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]; Institut Arbeit und Technik, 2019[84]).15 This boosted innovation and support R&D, which matched with the newly available high skilled workforce. Moreover, it avoided employment in technological development from being outsourced, thereby allowing for a boom in employment in the environmental industry. Now, the Ruhr area employs more workers in environmental related jobs than in the coal and steel industry, which became almost irrelevant (Institut Arbeit und Technik, 2019[84]). Together these policies managed to relocate 80% of workers into new industries and kept the unemployment rates low (Galgóczi, 2014[87]).

Social dialogue at the regional and community level became a cornerstone of adjustment policy. In Germany, the boards of all major industrial firms must comprise 50% employers and 50% employee delegates, which gives workers a strong voice in the gradual downscaling of employment (Abraham, 2017[83]; Galgóczi, 2014[87]). Agreements between workers and employers led to positive outcomes for communities. Collaboration between national and local government led to a widely supported plan for transitioning out of coal. Local communities, regional government, and local stakeholders have an active say in how to allocate investment to boost economic growth (Institut Arbeit und Technik, 2019[84]; Harrahill and Douglas, 2019[79]).

Thanks to the lessons learned from the coal transition, the Ruhr area is a frontrunner in the green transition. In the Ruhr area, the production of heavy industry products is still largely concentrated. In line with the net zero 2050 goals, the regional government has announced plans and investment schemes to turn this production green. Challenges faced in the Ruhr area to achieve net zero 2050 are tackled using a multi-stakeholder approach. New plans have been developed to create the world’s first net zero steel and aluminium industries, avoiding carbon leakage. Contributing to the success in this plan is cooperation, as well as an ambitious and clear industrial strategy (Institut Arbeit und Technik, 2019[84]).

Box 3.5. Institutional and social capital, and investment in infrastructure, determined the success of some counties in the Appalachia region, United States.