Chapter 2 examines whether Africa’s urban transformations could lead to an increase in conflicts on the continent. It shows that West Africa is currently characterised by a rapid increase in the number and size of cities, a trend followed by North African countries several decades ago. The Sahel region, especially, is experiencing rapid urbanisation in conjunction with a continuous growth of its rural population. The chapter then discusses some factors that may explain the concentration of conflicts in urban or rural areas. Intra-elite competition and new models of political organisation in democratizing states are two factors that could potentially lead to more violence in cities. However, armed groups can also flourish in rural areas, especially if they can control the population and natural resources. Finally, the chapter shows that urban and rural areas play a crucial role in the life cycle of armed conflicts in the region. As conflicts start, expand and end, the locations of violent events can shift from one area to the other, depending on local dynamics.

Urbanisation and Conflicts in North and West Africa

2. Cities, urbanisation and violence

Abstract

Key messages

Africa is experiencing unprecedented urban growth driven by high fertility rates, the emergence of new cities and migration.

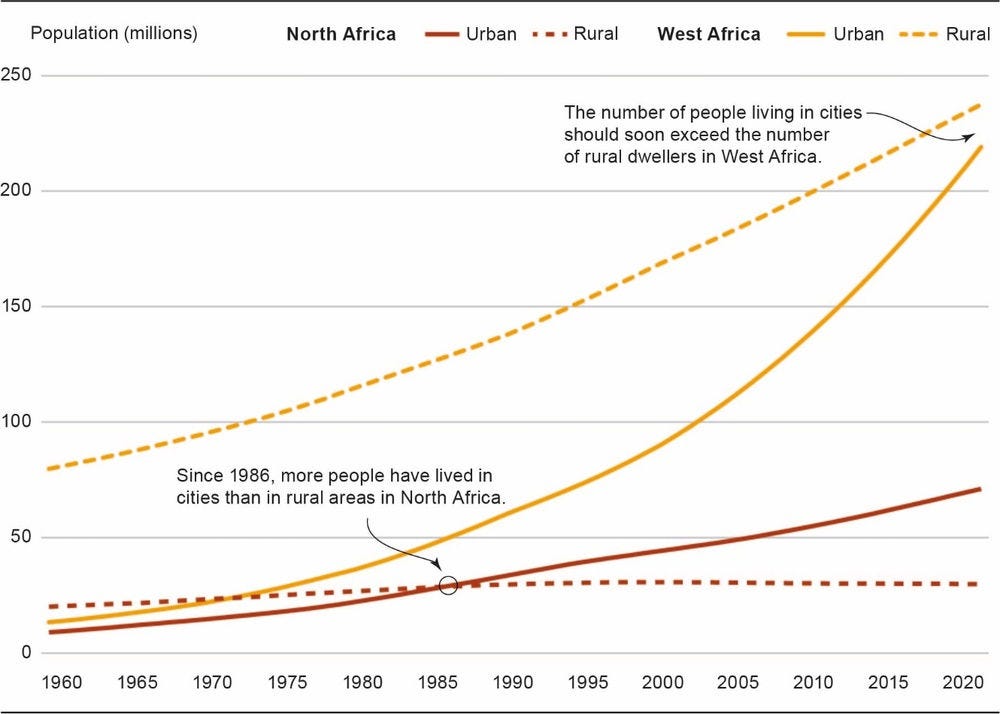

North and West Africa have followed similar urbanisation paths several decades apart from each other. In North Africa, more people have lived in cities than in rural areas for 35 years, while the urban population will soon reach 50% in West Africa.

The question of the relationship between cities and violence is particularly salient in North and West Africa, given the ongoing urban transformations and deepening political crisis.

While conflicts can concentrate around areas with distinctly urban attributes, rural hinterlands provide ideal resources for the belligerents to flourish and, potentially, challenge state forces.

The fact that armed groups have vacillated between urban and rural areas in North and West Africa could be explained by the “spatial life cycle” followed by each conflict.

Cities have long been synonymous with warfare, insurgency and politically motivated violence. Many of the world’s cities originated in part as military sites and places of commerce and, thus have been historically fought over and within. In recent years, the crucial importance of cities and urban areas as sites of conflict has attracted increasing attention in the context of the global trend toward urbanisation. As an increasing number and proportion of people live in cities, will urban conflicts increase in number and intensity? The question of the relationship between cities and violence is particularly salient in North and West Africa, given the ongoing urban transformations and the deepening political crisis that has subsumed numerous states.

Urbanisation in Africa

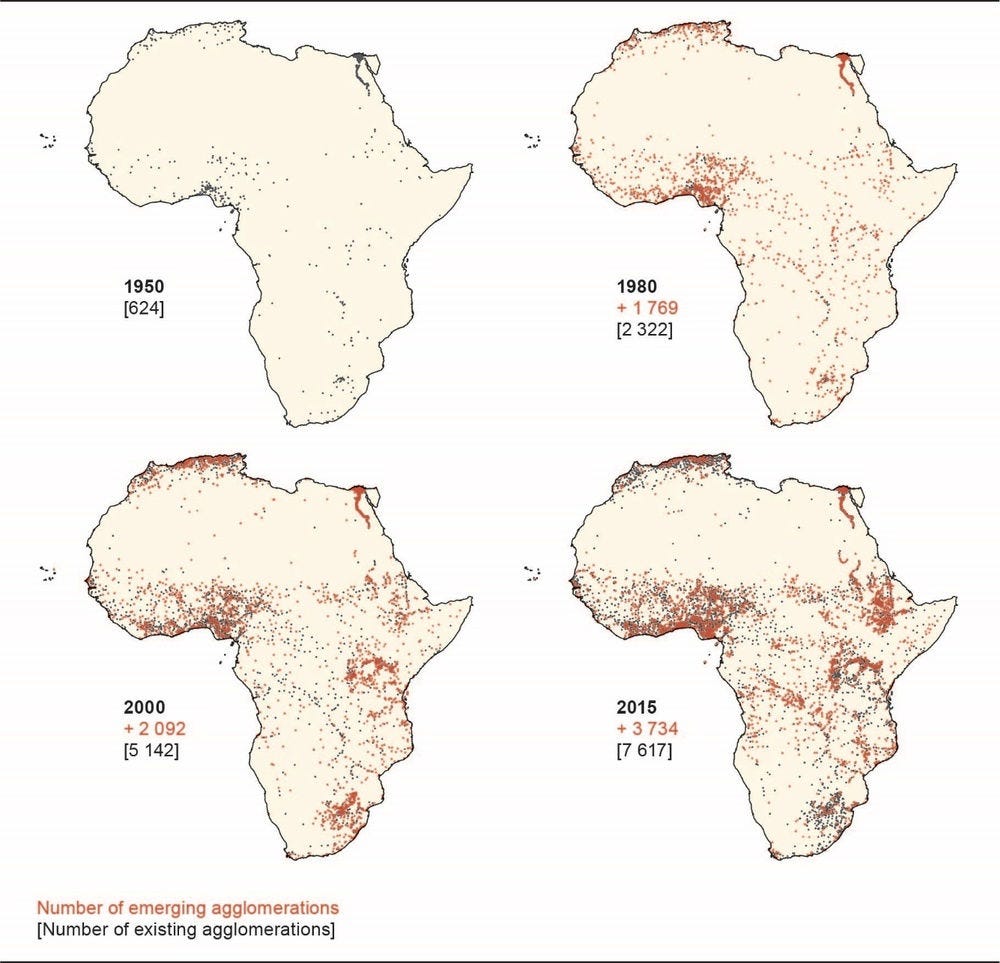

Africa is undergoing rapid urban transition in terms of the absolute size and number of cities. This process is driven by high fertility rates in urban areas, rural-to-urban migration, and an associated shift of rural into urban land use. While Africa remains the least urbanised of all regions, it has the fastest urbanisation growth rates in the world. Africa’s urban population has increased from 27 million in 1950 to 567 million in 2015. The continent’s population is expected to double by 2050, and two-thirds of this growth will occur in cities. More than half of Africa’s population lives in cities today, up from 18% in 1960 and 31% in 1990 (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]). The number of urban agglomerations also increased at an unprecedented rate. The continent counted more than 7 600 agglomerations of more than 10 000 inhabitants in 2015, against 5 142 in 2000 (Map 2.1).

Map 2.1. Emergence of new agglomerations in Africa since 1950

Source: OECD/SWAC (2020[1]), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en

This urban growth is a major driver of the current economic and social transformations observed in North and West Africa. As cities grow and multiply, so too does a diversification towards more perishable, more convenient to consume and higher quality products — all factors influencing agricultural production, trade and food consumption (Staatz and Hollinger, 2016[2]; Minten, Reardon and Chen, 2017[3]). The multiplication of small towns and intermediary cities also facilitates access to new markets, provides new economic opportunities, and helps disseminate innovative practices in rural areas (Banjo, Gordon and Riverson, 2012[4]). Further, urbanisation brings a wide range of social services, health infrastructure, and cultural amenities that had long been absent from rural areas and can enhance the level of human development in the region.

The benefits of urbanisation and improved accessibility also contribute to a shift from a subsistence-based economy to an economy based on regional markets (Allen and Heinrigs, 2016[5]). In southern Niger, for example, the production of onion and rice along the Niger River valley feeds local markets as well as the growing demand of the Gulf of Guinea and of Northern Nigeria, more than 500 kilometres away (Walther, 2015[6]). Finally, well-connected cities attract a growing number of entrepreneurs and service providers that explains the recent increase in non-agricultural employment observed in rural areas (Berg, Blankespoor and Selod, 2018[7]).

In West Africa, such rural-urban linkages are further encouraged by a relatively young urban network dominated numerically by small cities that play a crucial role in facilitating agricultural, commercialisation and economic diversification (Owusu, 2008[8]; Tacoli and Agergaard, 2017[9]). In northern Ghana, for example, cereals and cash crops flow through a dense network of urban markets, such as Bawku, Bolgatanga or Nyankpala, before being exported regionally or internationally (Karg et al., 2019[10]).

Strong urban growth

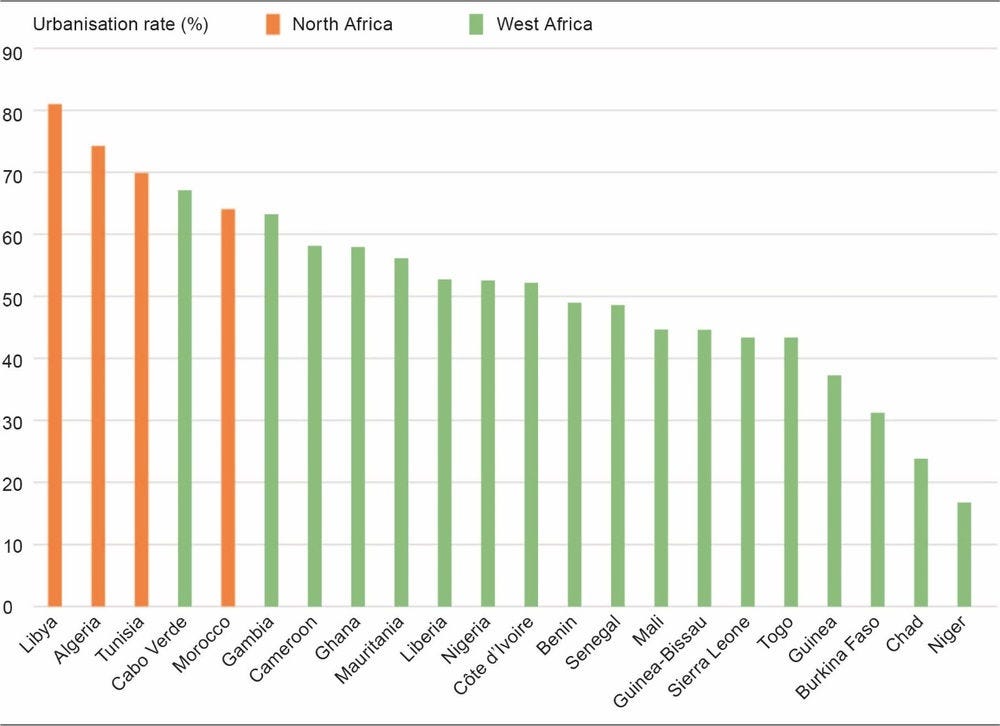

North Africa has gone through the demographic transition much earlier than West Africa, which explains why the regional urbanisation rate of the countries located north of the Sahara is 20% higher than it is in the rest of the region.1 Since 1950, the gap between the two regions has remained relatively constant (Walther, 2021[11]). In 2021, seven out of ten people live in cities in North Africa, while a little less than half of the West African population (48%) is urban. The least urbanised country of North Africa (Morocco, 64%) still has a higher share of urban population than the most urbanised country of continental West Africa (Gambia, 63%), excluding Cabo Verde. Cabo Verde’s demographic profile is similar to North African countries, characterised by low fertility and natality rates and high urbanisation rates. More than three-quarters of the population are urban in Libya and Algeria, where most cities are concentrated along the Mediterranean coast. Significant differences can be observed within West Africa: while urbanisation rates exceed 50% in several countries, such as Cameroon and Mauritania, less than 30% of the population in Chad and Niger is urban (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Urbanisation rate by country in North and West Africa, 2021

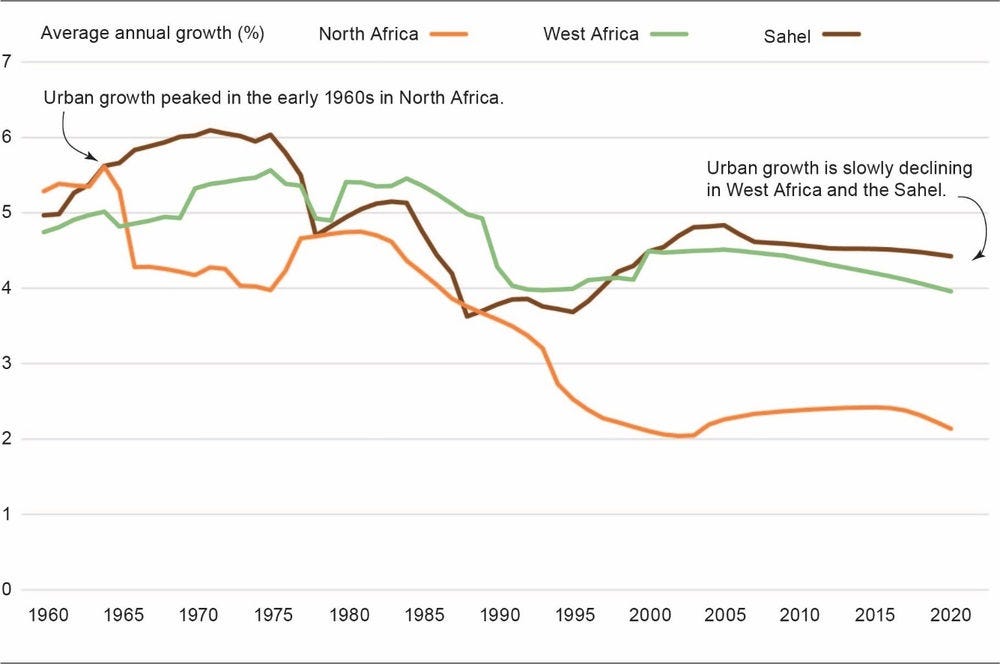

Over the past 70 years, the urban population has grown faster than the rural population in the region. North of the Sahara, it has been 35 years since there were more rural than urban dwellers. The urban population of Algeria, Morocco, Libya and Tunisia was close to 71 million people in 2021. In the West African countries considered in this report, the number of people living in cities now approaches 200 million, whereas the rural population is more than 238 million (Figure 2.2). Urban growth in North African countries has fallen by more than half between 1965 and 2000. West Africa is experiencing a similar evolution, but with a considerable temporal delay. In the Sahel, especially, urban growth has remained at high levels throughout the 2000s and has only recently been declining. The urban population of Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Chad is estimated at more than 19 million people in 2020 (UN, 2021[12]) Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.2. Settlement dynamics in North and West Africa, 1961-2021

Figure 2.3. Urban population growth per sub-region, 1961-2021

Note: Sahelian countries include Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Senegal.

Source: (UN, 2021[12]), World Population Prospects 2019.

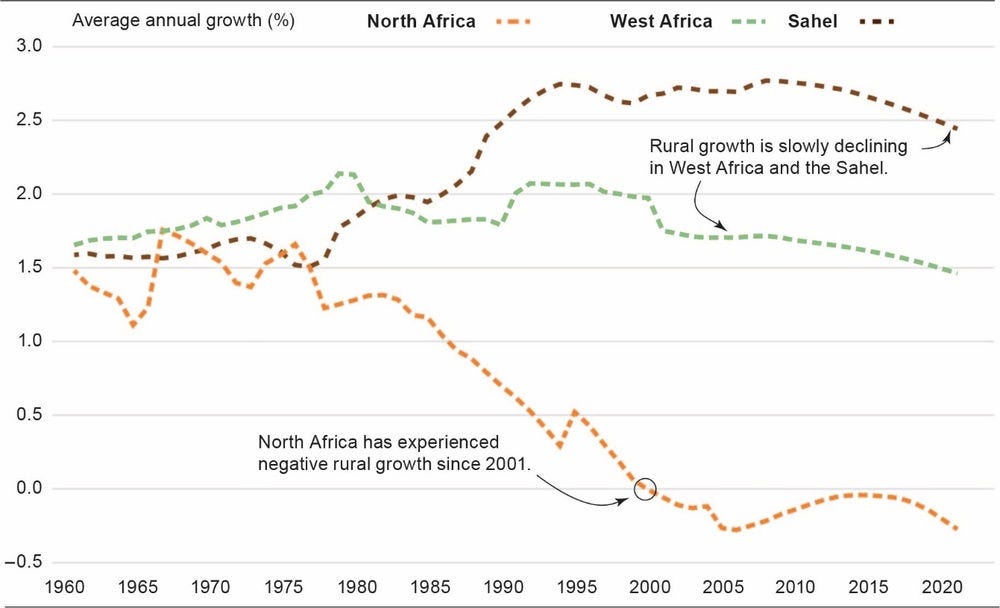

In the four North African countries covered by this report, population growth was seen mostly in cities. The annual average growth rate of rural populations has been declining sharply since the end of the 1990s. It was negative between 2000 and 2010, and zero between 2010 and 2020. The absolute number of people in rural Algeria, Morocco, Libya and Tunisia has been stagnant at about 30 million for the past 20 years. Rural growth is still high in West Africa (+1.5% in 2021) but is slowly declining. It is in the Sahel that the annual growth of the rural population is the strongest (+2.5% in 2021). The rural population of the Sahel is estimated at 46 million people in 2020, as compared with 26 million 20 years earlier (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4. Rural population growth per sub-region, 1961-2021

Note: Sahelian countries include Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Senegal.

Source: (UN, 2021[12]), World Population Prospects 2019.

The primacy of capital cities

Many countries in the region have a macrocephalic urban network, in which most of the country’s essential commercial and political functions and a large percentage of its urban population are concentrated in one urban area. This situation represents a deviation from the theoretical urban population distribution according to which the largest city is twice as large as the city with the next smallest population. If the largest city in the country has 1 million inhabitants, for example, the second will, in theory, have a population of half a million, for a ratio of 2:1. In Liberia, Guinea, Togo and Mali, the ratio between the first and second city is greater than 10, a high indicator of urban primacy for Monrovia, Conakry, Lomé and Bamako (OECD/SWAC, 2019[13]). Guinea-Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Chad and Sierra Leone also have urban networks dominated by a single large city.

Further, as countries in the region urbanise, the importance of political (or economic) capitals will continue to grow over time, as compared with the second-largest city (OECD/SWAC, 2019[13]). For example, with over 2.8 million inhabitants, Ouagadougou is 3.6 times more populous than Bobo-Dioulasso in 2020, whereas the two cities were approximately the same size in 1950. In Cameroon, Yaoundé doubled in size, from 2.3 million to 4.6 million inhabitants between 2010 and 2020, while the population of Douala only increased from 2.2 million to 3 million.

Nigeria is the only West African country with a truly multicephalic network, in which a number of large cities occupy the upper echelon of the urban hierarchy. The metropolitan areas of Lagos, Kano and Onitsha function as de facto capital cities of the country’s three main ethno-linguistic regions (OECD/SWAC, 2019[13]). In the southwestern part of the country, the presence of high urban densities and numerous cities of varied sizes has been documented since the precolonial era. The transatlantic slave trade fostered the urban development of the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo and the kingdom of Benin before these areas came to rely on agricultural products such as palm oil. In the north, the urban network of Hausa city-states and the Kanem-Borno empire in the Lake Chad basin owes its existence, in large part, to regional and trans-Saharan trade. In the southwest, the Igbo and Ibibio urbanisation of the Niger Delta and its hinterland has colonial origins.

Macrocephaly explains the relatively small number of large cities on the continent. In 2015, 92% of cities had fewer than 100 000 inhabitants in West Africa, for example (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]). Africa has only 11 agglomerations with more than 5 million people: Alexandria, Cairo, Dar es Salaam, Johannesburg, Khartoum, Kinshasa, Kisumu, Lagos, Luanda, Nairobi and Onitsha. The 29 cities in the region with a population of one million inhabitants account for 80 million people, or 44% of the total urban population. That is nearly twice the population of the 182 cities with between 100 000 and 1 million inhabitants (25%) which account for some 45 million people (OECD/SWAC, 2019[13]). Cities are also quite unevenly distributed across the continent. Two countries, Kenya and Nigeria, contain 20 of the 50 largest urban agglomerations by built-up area (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]). Close to half of West Africa’s 2 469 agglomerations with more than 10 000 inhabitants are located in Nigeria, and less than 10% of them in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Small countries such as Cabo Verde, Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, sparsely populated ones like Mauritania and countries dominated by one large city, like Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, have fewer than 50 cities each with more than 10 000 inhabitants.

Historical evolution of cities

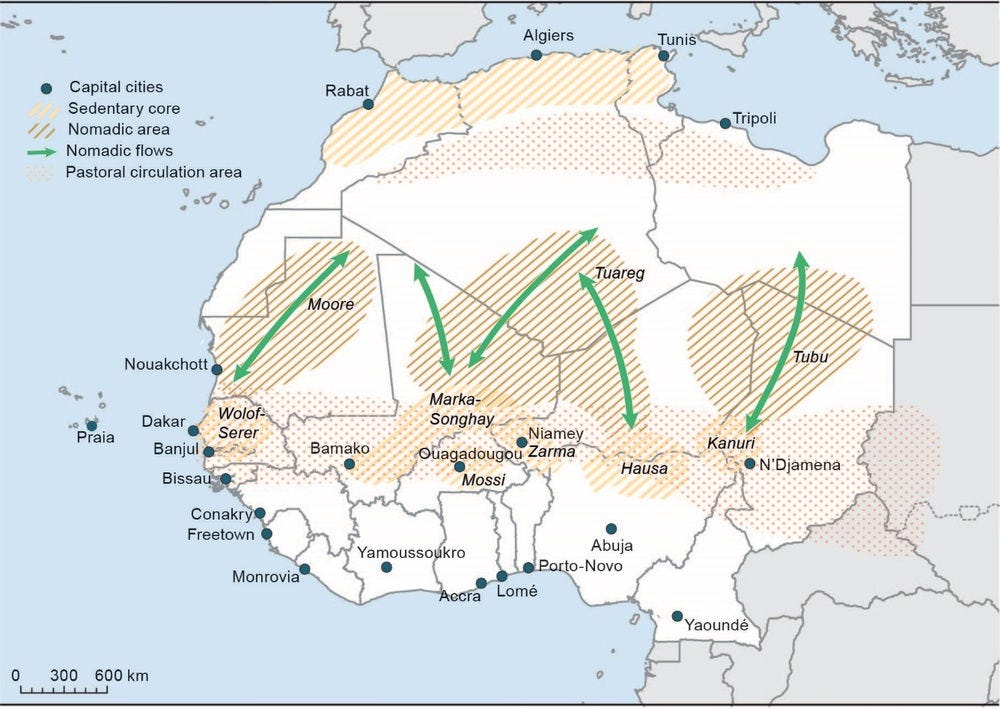

The distribution of the population in North and West Africa follows a well-known pattern according to which high densities are explained by human factors, such as the existence of precolonial empires or man-made oases, while low densities are explained by natural factors, particularly the absence of rainfall. Historically, the West African Sahel region has played a key role in the circulation of people, ideas and goods between the two “shores” of the Sahara. In this region, human settlement is marked by alternating sedentary cores with high-population densities and intercalary voids (Retaillé, 1989[14]) (Map 2.2). Each of the Sahelian sedentary cores is associated with a nomadic area in the Sahara. Between the Senegal and Gambia rivers, the Wolof-Serer core is connected to the nomadic space of the Moors. Further east, the Marka-Songhay core occupying the loop of the Niger River, the Mossi core in Burkina Faso, and the Hausa core located between Sokoto, Kano and Maradi are all connected to the Tuareg sphere. In the Lake Chad region, the Kanuri core is open to the Tubu sphere. The presence of these high densities is of precolonial origin and corresponds to the influence zones of the Ghana and Mali empires, the Mossi kingdoms, the Hausa city-states and the Kanem-Borno empire.

Map 2.2. Sedentary cores and nomadic areas in North and West Africa

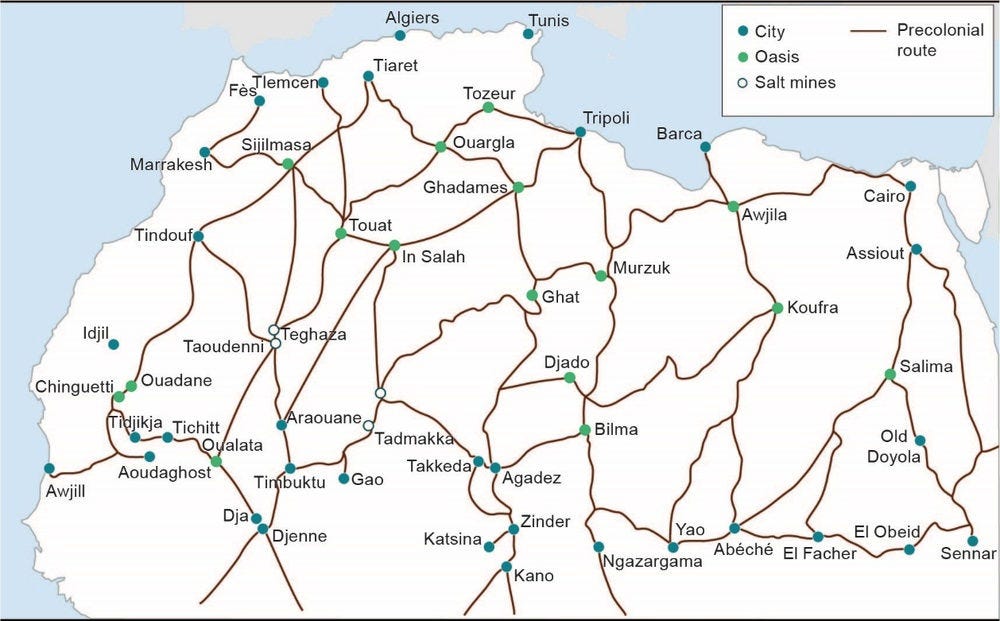

Until the colonial period, Sahelian cities occupied the political and economic centre of these sedentary cores. These cities were linked by trade routes to the Mediterranean coast through a string of Saharan oases and to precolonial kingdoms, such as the Ashanti in today’s Ghana or the Yoruba kingdom of Oyo in today’s Nigeria (Map 2.3). Such Sahelian cities have been defined as “a crossroads in which the spatial structure, made up of cities and markets, could adapt to climatic variations and political crises” (Walther and Retaillé, 2021, p. 30[16]).

Map 2.3. Precolonial routes, oases and cities

The colonial and postcolonial eras have considerably reshaped this spatial organisation, without completely erasing its specificities. While precolonial West Africa had several agglomerations located inland and not a single major city along the coast, colonial powers established and emphasised coastal cities to facilitate trade and export. The introduction of new cities, the establishment of political boundaries, and the reorganisation of trade routes toward the Gulf of Guinea considerably disrupted the regional urban network inherited from precolonial times. Precolonial urban centres such as Timbuktu and Djenné, for example, were cut from the trade networks that sustained their growth, while other centres emerged by gradually being assigned administrative functions to support an increasing colonial and post-colonial territorial organisation.

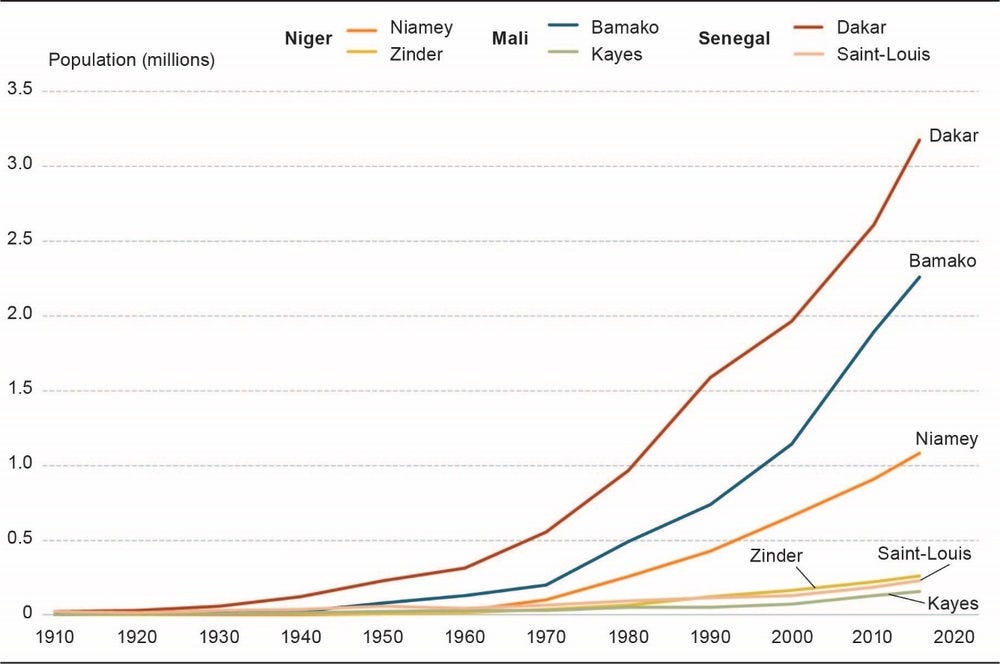

As a consequence, the growth of colonial cities has often been more spectacular than that of older urban centres. In Niger, for example, Niamey was home to less than 10 000 people in 1950, as compared with 12 000 in Zinder, the historic capital city of the Damagaram Sultanate. By 2020, the population of Niamey was estimated to exceed 1.2 million people, almost 5.5 times the size of Zinder. A similar change is taking place in Mali and Senegal, where Bamako and Dakar’s population exceeded those of Kayes and Saint-Louis well before decolonisation (Figure 2.5).

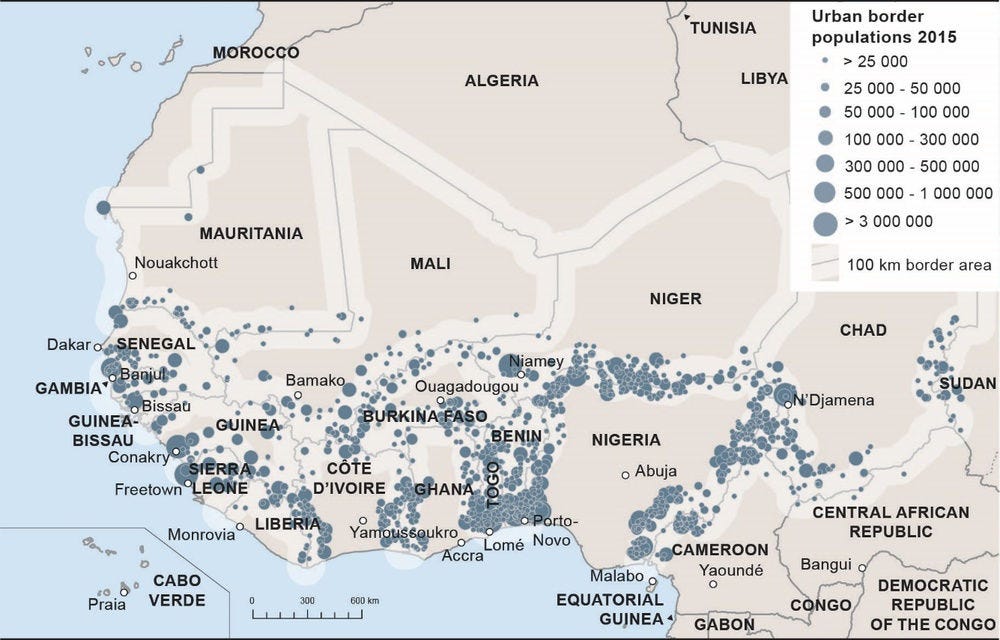

Figure 2.5. Demographic changes in Niger, Mali and Senegal, 1910-2015

In an attempt to exploit localised natural resources, colonial and postcolonial powers also contributed to oppose sedentary and nomadic livelihoods (Walther and Retaillé, 2021[16]). By dividing the region into states and assigning social groups to a particular territory, these initiatives disorganised the mobility patterns of West African societies and encouraged the development of informal trade activities that bypass formal regulations. Nowhere is the impact of the territorial policies of the colonial and postcolonial states more visible than in border regions (Nugent, 2019[17]). Recent research shows that border cities are smaller, grow faster and have higher density than other cities in West Africa (OECD/SWAC, 2019[13]). This rapid growth is especially visible within 50 kilometres of national borders, where the most dynamic markets are located, such as along Nigeria’s borders and in the Gulf of Guinea. A third of the West African population lives within 100 kilometres of a border in 2020 (Map 2.4).

Map 2.4. West African urban population within 100 km of a border, 2015

Source: (OECD/SWAC, 2019[13]), Population and Morphology of Border Cities, https://doi.org/10.1787/80dfd9d8-en.

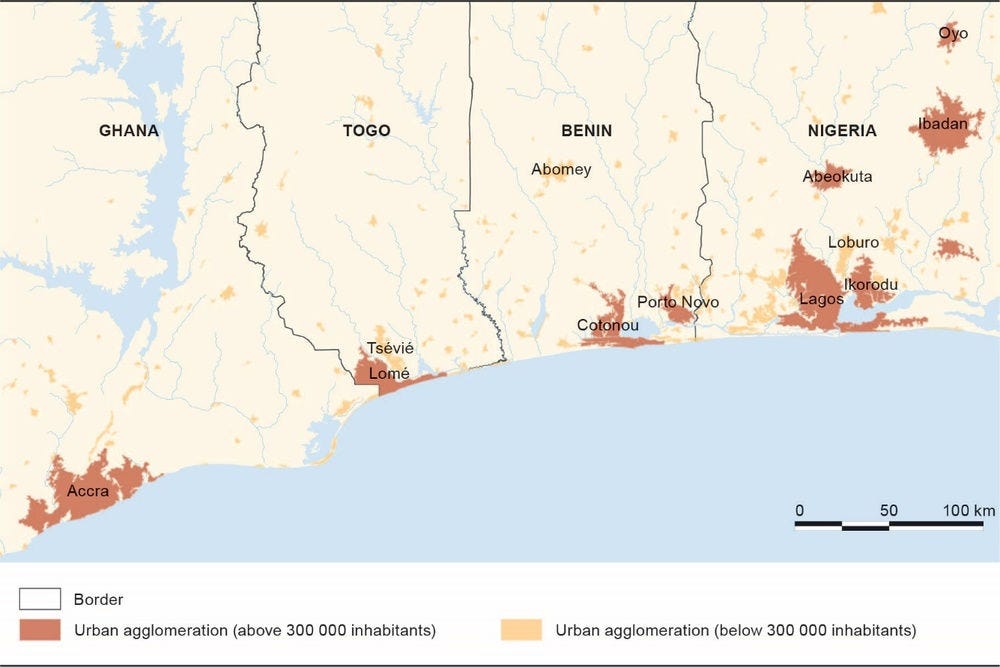

Border cities and markets play a crucial role in the transnational circulation of agricultural goods produced in the region (OECD/SWAC, 2017[18]) and of manufactured products imported from the world markets, such as used cars, cereals, petroleum, plastic materials and electronics (Walther, 2015[6]). Some of these cities are a major component of the transnational metropolitan areas that have emerged in recent decades, such as the conurbation that stretches from Accra in Ghana to Ibadan in Nigeria (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]). The large population, high densities and as yet unexploited potential of this coastal area has led the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to identify the Abidjan-Lagos corridor as a priority for regional integration (AfDB-UEMOA, 2017[19]) (Map 2.5). Yet, the ambition to use the corridor as an instrument of regional integration faces numerous challenges, including roadblocks, high transit fees imposed on vehicles, and numerous bans of commodities Nigeria imposes on its neighbours. Thus far, regional trade remains segmented by country, and much of the investment is dedicated to the north-south corridors connecting the ports of the Gulf of Guinea to the Sahel (Nugent, 2022[20]).

Map 2.5. Urban agglomerations between Accra and Ibadan, 2015

Source: (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en.

Recent urban transformations

As in other regions of the world, North and West African cities differ from rural areas in their size, density and social heterogeneity. As sites of diversification and innovation, cities are characterised by the presence of a specialised workforce employed in non-agricultural activities, such as trade, education and administration. Cities also tend to juxtapose people of different backgrounds, origin and wealth, which makes social inequalities and ostentation more visible in urban than in rural areas (Coquery-Vidrovitch, 1993[21]). The social diversity created by the urban fabric encourages the autonomy of individuals from traditional social structures. In that sense, larger towns are distinguished from small villages by the fact that they allow the juxtaposition of differentiated social groups in a shared setting.

In recent years, a redistribution of population from the coast inland can be observed (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]). These rapidly shifting and expanding urban processes have produced several notable examples of rapidly growing agglomerations, such as Onitsha in Nigeria, which has been transformed from a small urban agglomeration into one of the largest agglomerations in West Africa, with 8.5 million (2015) and a city cluster size of 28 million (OECD, UNECA, AfDB, 2022[22]). This expansion has generated cities in close proximity, creating opportunities for networks and growth through trade, knowledge and employment. Economically and socially, urban areas in Africa are much more productive, wealthy, innovative and with greater access to infrastructure than other areas: piped water, electricity access and mobile and car ownership, for example, are all higher in cities (OECD, UNECA, AfDB, 2022[22]).

Even small and medium-sized cities, which constitute the vast majority of urban centres, perform well relative to rural areas. Underemployment and the percentage of adults without jobs are both lower in urban areas, while salaries are on average more than double those in rural areas. The number of years in education is on average 2.5 to 4 years more than in rural areas, and fertility rates, while high, are more than a third lower in urban areas (Corker, 2017[23]). Proximity to a major city is one of the strongest predictors of cell phones, healthcare, education and higher wages. Yet, despite their economic role in the regional economy, African cities have long suffered from low expenditure on local governments and a low degree of autonomy. Urban municipalities, for example, must contend with limited resources and poorly defined political and fiscal roles that prevent them from offering adequate social services to urban dwellers.

An urbanisation of conflict?

A key spatial aspect of armed conflicts is that they tend to be unevenly distributed across the world and form clusters of violence that can either be contained within national boundaries, or spread across entire regions, as in the Sahel-Sahara today. Due to the shifting strategies adopted by the belligerents and the changing nature of warfare since the end of the Cold War, the geography of such armed conflicts is a subject of lively debate. While some have argued that conflicts tend to concentrate around areas with distinctly urban attributes, including high population densities and good infrastructure (Buhaug and Rød, 2006[24]; Raleigh and Hegre, 2009[25]), others have noted that rural hinterlands provide the best resources for belligerents to flourish and, potentially, challenge state forces (Mkandawire, 2002[26]). The question whether conflict is more urban or rural in nature is still contested (Dorward, 2022[27]; Radil et al., 2022[28]).

More urban conflicts?

Recent research on the geography of violence shows that irregular conflicts are increasingly taking place in cities such as Baghdad, London, Madrid, Mumbai, Paris or Tel Aviv, and away from open fields, deserts and jungles (2011[29]). The idea that cities represent a new battlefield has also gained traction in the African Studies literature, where authors have documented cities’ political and economic characteristics that make them important sites of contestation and control. Cities often represent potent symbols of state authority, while also serving as key nodes in (trans)national economic networks and sites of capital accumulation that can be fought for and captured to meaningful effect (Beall, Goodfellow and Rodgers, 2013[30]; Büscher, 2018[31]; Goodfellow and Jackman, 2020[32]). The last decade has provided numerous examples of political violence carried out both by state and non-state actors that illustrate the potential for conflict to be highly urbanised. In January 2017, for example, a suicide bomber from Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) attacked the joint French-United Nations (UN) military base in Gao, a commercial hub along the Niger river. The attack, which killed 77 and injured more than 100, was the deadliest suicide bombing to date in Mali (ACLED, 2021[33]) (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. How the Malian conflict affects the city of Gao

The city and region of Gao were significantly affected by the northern Malian rebellion of 2012. Gao was captured first by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), and later by the jihadist coalition under the control of the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) that took over northern Mali from the MNLA. Both the MNLA and the MUJAO inflicted serious human rights violations on the population of Gao, including amputations and beatings (HRW, 2012[34]).

The violence unleashed in Gao in 2012 set the stage for enduring intercommunal tensions after the town was liberated in 2013. In February and March 2013, there was more jihadist resistance against the French and Malian military presence in Gao than there was in Kidal and Timbuktu. Gao was the site of what has been called Mali’s first suicide bombing, in February 2013, and of a suicide bombing in January 2017 targeting a mixed patrol of the Coalition des Mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA), Plateforme and Malian army personnel.

More recently, ethnic tensions flared in incidents such as the 2020 intercommunal clashes involving what appeared to be Songhai-led lynching of Arabs accused of theft. Gao has also been repeatedly targeted by jihadists, in part because the city emerged as the nexus of various security initiatives in northern Mali . Gao hosted the Malian headquarters of France’s counterterrorism mission for the Sahel, Operation Barkhane, and was the last of Barkhane’s bases that France turned over to Malian forces as French forces withdrew from Mali in 2021-2022. Gao is also the eastern headquarters of the United Nations’ Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), and thus remains important for international security architectures.

Source: Alexander Thurston for this publication.

The idea that African conflicts can redefine the urban landscape is now well established in the literature, given the destructive impact of civil wars and terrorist attacks on cities (Büscher, 2018[31]). While the consequences of conflict on cities are well documented, the factors that drive belligerents to urban areas are more difficult to identify. This difficulty stems from the fact that the conflicts observed in Africa take very different forms depending on the region. Since the end of the Cold War, the nature, forms and locations of conflicts in Africa have been fundamentally transformed (Williams, 2016[35]). Conventional forms of rural armed conflict have shifted towards alternative modes of political violence, including riots, demonstrations, and ‘civic conflict’ which result from the competition of several social groups for the resources and services offered by cities (Golooba-Mutebi and Sjögren, 2017[36]). In April 2008, for example, thousands of people marched in the streets of Abidjan, Dakar and Ouagadougou to protest against rising food and fuel prices, and at least 24 were killed in similar demonstrations in Cameroun. More recently, thousands have violently taken to the streets of Bamako in Mali to demand that President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita resign or that French forces leave the country.

The first factor that can explain why conflict may be concentrated in cities is population size and density (Table 2.1). As African cities grow, they can potentially bring antagonistic social groups into closer proximity within multi-ethnic cities, increasing the probability that disputes will turn violent (Buhaug and Urdal, 2013[37]). Rapid population growth may also generate conflict by amplifying social strain and competition surrounding access to urban resources, labour and housing (Østby, 2016[38]; Gizelis, Pickering and Urdal, 2021[39]). In Nigeria’s Middle Belt, for example, the frequency of violent riots in Jos, where several ethnic and religious minorities live together, lends credibility to this view (Krause, 2018[40]). Finally, the absolute size of the urban population may also lead to increased levels of violence in urban areas. Larger cities include more disaffected youths who could be tempted to resort to political violence and protest movements (Urdal and Hoelscher, 2012[41]; Menashe-Oren, 2020[42]).

Table 2.1. Possible reasons for the concentration of conflicts in urban areas

|

Potential factor |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Population size and density |

Increasing population and density encourage social proximity and political mobilisation. |

|

Intra-elite competition |

Cities provide an arena for political, economic, and religious elites to compete within democratising states. |

|

Migration |

Cities attract migrants, refugees or other marginalised groups that can be recruited by armed groups. |

|

Targets |

Cities represent a symbol of state authority and a military target. |

Source: Compiled by the authors from Staniland (2010[43]), Beall et al. (2013[30]), Büscher (2018[31]), Dorward (2022[27]) and Radil et al. (2022[28]).

Urbanisation also encourages intra-elite competition and new models of political and civil society organisation that allow politically motivated and often highly educated urban residents to organise (Straus, 2012[44]). The urban poor population is often mobilised by political elites seeking to capture power, support and resources, which could explain the increase in urban violence. In that sense, Africa’s recent transition towards multiparty politics has turned its cities into key political battlegrounds for political and religious elites (Raleigh, 2015[45]). These forms of violence are fuelled by institutional changes adopted by countries undergoing political transitions. For example, democratisation without free elections has disenfranchised a fringe of urban residents, who feel politically and economically marginalised (Golooba-Mutebi and Sjögren, 2017[36]; Harding, 2020[46]).

Another factor that could make African cities susceptible to violence is that they tend to attract an increasing number of migrants more likely to experience marginalisation and find difficulty in adjusting socially and psychologically to urban life (Buhaug and Urdal, 2013[37]). In some regions, such as the Lake Chad basin, the Great Lakes or Darfur, cities also attract numerous refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) who are victims of both government forces and violent extremist organisations. The persistence of forced displacements and insecurity has led to new urban forms that either shape existing cities or give rise to new urban patterns in previously rural areas. The strong urban growth observed in the eastern and southern part of Chad, for example, is due to the forced migration of refugees from Sudan and the Central African Republic. In this border region, conflicts tend to create dense agglomerations that expand or shrink in size on the Chadian side of the border, depending on the political context in neighbouring countries.

In addition, cities represent a symbol of state authority and a military target that armed groups must defeat if they wish to overthrow the central government. Capturing capital cities obviates the need to capture larger territories and can decide the fate of whole conflicts. In 2011, for example, the Second Ivoirian civil war ended with the capture of Laurent Gbagbo in Abidjan and the reinstallation of president-elect Alassane Ouattara. The strategic role of capital cities in Africa is so important that it often determines whether or not regional bodies and international alliances intervene in a conflict. For example, the siege of Monrovia by the Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) in 2003 was a major episode of the second Sierra Leone conflict that led to the intervention of the United States Joint Task Force Liberia and the ECOWAS force.

The conflict in Mali offers yet another example of how strategic capital cities can be. If Bamako has been relatively peaceful, the city and its environs nevertheless remain vital pieces of the security mosaic in the country. Because control of Bamako is equated with control of the Malian state, even distant threats to the capital can generate dramatic responses. During 2012, for example, the jihadist takeover of the north of the country did not provoke an immediate response from regional and international actors. Towards the end of the year, jihadist advances into central Mali, which appeared to some observers to be an initial step towards an attempted takeover of Bamako, triggered a rapid French-led response in the form of Operation Serval, which reversed jihadists’ territorial gains in the centre and broke their control over northern cities (Chivvis, 2015[47]).

Cities are sites where extreme wealth and extreme poverty coexist, sometimes within a few hundred meters of each other. In Lagos and Nairobi, for example, the slums of Makoko and Kibera are located a stone’s throw away from affluent neighbourhoods and business districts, where many poor employees work. In the absence of affordable and reliable public transportation system, living in slums is the only option left to the urban poor. This combination of ostentatious signs of success and abject poverty, typical of large African urban centres, provides ample economic resources to those who wish to challenge or evade the state. Violent organisations may be drained into the cities, where money can be more easily obtained through criminal activities. This scenario is however relatively uncommon in North and West Africa, where jihadist organisations have focused on drug trafficking, cattle rustling and illegal gold mining to fuel their international development, training and arms purchases. None of these activities take place in cities.

Finally, rebels motivated by assuming political power in capital cities may emerge in urban areas or have an urban component, but persistent urban guerrilla movements are rare in Africa. Capturing urban areas and state institutions remains largely out of reach of Africa’s violent organisations. Thus, as in Latin America since the 1970s (Holmes, 2015[48]), urban guerrilla movements often have to retreat to rural or peripheral areas, where it is easier to recruit, get resources and maintain a territorial presence.

More rural conflicts?

While conflicts are related in complex ways within urban areas, there is no straightforward association between the two. Indeed, an important strand of the literature argues that armed conflicts, especially civil wars and rebellions, have traditionally been associated with rural areas. Cities may provide potential resources for armed groups to flourish, but physical proximity can also be used by government forces to repress them more efficiently than in rural areas (Table 2.2). Urban guerrillas thus have very short lifespans and tend to relocate to areas where rugged terrain (Hendrix, 2011[49]), dense forests (Raleigh, 2010[50]) and porous borders (Radil et al., 2022[28]) can provide safe havens. This makes rural and remote areas favourable settings for asymmetric conflicts between armed groups and the state.

In some regions, cities may also remain relatively unaffected by political violence (Beall, Goodfellow and Rodgers, 2013[30]). Kinshasa, for example, fell without much resistance to the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL) during the First Congo War in May 1997. In the Sahel, Niamey in Niger and N’Djamena in Chad have largely been spared by terrorist attacks, despite being very close to the main theatre of operation of the insurgency. In Mali, Bamako was a hub for the displaced (Sangaré and Cold-Ravnkilde, 2020[51]), including displaced local elites such as the mayors and other officials from central Mali fleeing from jihadist threat.

Table 2.2. Possible reasons for the concentration of conflicts in rural areas

|

Potential factors |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Safe haven |

Insurgents are more easily defeated in urban areas than rural areas. Sometimes cities or urban areas can remain places of “calm” or refuge despite surrounding conflicts. |

|

Security |

Rural areas are less well defended than cities. States work hard to maintain security of urban areas. |

|

Resources |

Rural areas provide agricultural, mineral and human resources that armed groups can use to control local communities. |

Source: Compiled by the authors from Beall et al., (2013[30]), Büscher (2018[31]), Dorward (2022[27]) and Radil et al. (2022[28]).

Many African states struggle to project power and authority to the rural periphery (Herbst, 2000[52]). As a result, states struggle to effectively counter insurgents in rural areas, giving rebels an advantage when operating far from the state’s urban bastions of coercive power. Indeed, civil wars are more likely to be located far from a nation’s capital and are typically longer in duration (Buhaug, Gates and Lujala, 2009[53]). This is particularly true of secessionist conflicts. In Mali and Niger, for example, Tuareg rebellions have typically developed in some of the most remote regions of the country, where state power had long been weak. Further east, in Chad, political power has since independence been challenged by rebel groups whose main base of operations lies more than 1 000 kilometres north of N’Djamena, in the Tibesti region.

From a demographic perspective, one could argue that the development of rebel movements in the Adrar des Ifoghas in Mali, Aïr Mountains of Niger, and Tibesti massif of Chad is less due to their rural nature than to the remoteness of the regions. After all, arid regions consistently have the highest urbanisation rates of the country, since the vast majority of the population lives in cities (Bossard, 2015[54]). In Niger, for example, the proportion of the population that lives in cities is three times higher in the Saharan region of Agadez (45%) than in the rest of the country (16%) according to the Niger Institute of Statistics (2022[55]). However, while these regions remain fundamentally more urban than the rest of the country, a significant portion of the violent events observed in recent decades are located away from cities, in rural areas where armed groups compete for the control of local resources or trade routes (Walther et al., 2021[56]).

Rural areas have a high potential for conflict, because rural scarcity can be associated with ethnic tensions over resources that central governments rarely address (Buhaug and Urdal, 2013[37]; Gizelis, Pickering and Urdal, 2021[39]). These tensions can potentially lead to two principal violent outcomes: communal clashes between native populations and settlers, and reactions by rural residents to land seizures or ecological damage caused by the state. The Ogoni uprising in Nigeria’s Niger Delta, protesting land degradation by the government and the oil industry, is a case in point (Watts, 2004[57]). However, the neglect of the rural areas has rarely led to peasant rebellions in the West Africa context, unlike in Uganda and Mozambique, where rebel movements demonstrate the potential violent involvement of the countryside, often after aggressive oppression by state forces (Mkandawire, 2002[26]).

The conflict life cycle

Rather than debating whether violence is inherently urban or rural, some have argued that conflicts are not exclusive to either setting, as they often relocate throughout the duration of a conflict in a way that exploits the strengths and weaknesses of both cities and their hinterlands. One of the earliest proponents of this approach was (Tse-Tung, 1937, 2005[58]), who suggested during the Chinese Revolution that rebellions necessarily first emerge in the countryside and later try to conquer cities. Mao’s theory built on his own revolutionary activity: the Chinese Communist Party initially followed the Marxist belief that the socialist revolution should be led by the urban proletariat but later moved away from the cities of Shanghai, Beijing and Guangzhou to first mobilise the rural peasantry. Mao argued that the support of the rural civilian population was key to building a territorial support base from which to launch a campaign against the central government. His theory proved highly influential in the anticolonial wars that started in the 1950s across the developing world, even though the Chinese revolutionary context differed significantly from that of Africa (Box 2.2).

In Algeria, for example, the National Liberation Front (FLN) initially launched a series of attacks against government targets and French settlers in the interior of the country that were severely repressed by colonial forces. Realising that fighting in rural areas would not gather much attention for their cause, the FLN launched a campaign of urban terrorism to coincide with the United Nations General Assembly in 1957. The FLN focused its terror campaign on the capital city, Algiers. After a brutal counterinsurgency campaign led by French forces, the FLN was eventually defeated in the city and returned to the countryside, where its guerrilla tactics increasingly targeted civilians who did not support them. The FLN ultimately gained control of the mountainous regions of Kabylie and Aurès and used neighbouring countries to launch attacks against the French (Galula, 1963, 2006[59]), before independence was declared in 1962.

More recently, the Lake Chad area has followed a similar evolution. Until 2002, what would ultimately become Boko Haram was largely an urban movement formed around a small number of radical Islamist youth, many from the social upper class, who gathered at the Alhaji Muhammadu Ndimi Mosque in Maiduguri (Agbiboa, 2022[60]). In 2002, an offshoot of the sect led by Mohammed Ali declared the city and its social establishment corrupt and left Maiduguri for the rural community of Kanam, near the Nigerien border (Walker, 2012[61]). After a dispute with the police over fishing rights, the surviving members returned to Maiduguri in late 2003, where they established their own mosque, the Ibn Taimiyyah Masjid, near the railway station.

The following years were marked by a gradual expansion of Boko Haram to other cities in Bauchi, Yobe and Niger states that culminated in the 2009 uprising in Maiduguri, one of the most violent urban events ever recorded in West Africa. The government crackdown that followed the uprising led Boko Haram to flee to rural areas and neighbouring countries. From its strongholds in the countryside, Boko Haram started a campaign of assassinations in several cities of the northeast and in the federal capital of Abuja. Boko Haram was expelled a second time from the major cities of the region by the government and the Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) in 2015 and fled to the Mandara Mountains, Gwoza Hills and Sambisa Forest.

Box 2.2. Mao and the Chinese guerrilla model

The back-and-forth nature of African insurgencies help to highlight why many conflicts in North and West Africa differ from the classic rural-to-urban trajectory theorised by Mao. Mkandawire (2002, p. 182[26]) summarised this by arguing that the “social terrain of rural Africa [is] highly unsuitable for classical guerrilla warfare” for several reasons. Primarily, unlike in China, where the rural peasantry was exploited by a landlord class, most African farmers have access to labour and land, and their activities are mediated by markets. Since the rebels have little to offer peasants in the rural areas in terms of political rights, land rights or agrarian reform, there is little incentive for this “uncaptured peasantry” to join a rebel movement. In fact, many insurgencies and armed movements have instead aggressively killed and hurt civilians, instilling fear and coercing the populace, indicating that there is little consideration of voluntary participation or widespread appeal to the rural populations.

Another key difference is the limited state capacity to extract surplus goods from farmers, due to adjustment programs and informal trade networks. This means that African rebel movements are often driven more by social and religious issues such as ethnicity or implementation of religious laws than by Maoist-style economic ideology. As an implication of this shift to identity-based rather than ideology-based movements, Africa is characterised by an exceedingly large number of rebel groups, whose motivations and relationships with urban areas often differ from group to group. For example, externally supported movements returning from exile may simply pass through rural areas on their way to capture power in the capital city (Mkandawire, 2002[26]). Alternatively, rebel movements that have become rural after a defeat in an urban setting usually struggle to mobilise popular support among local populations and tend to cause enormous suffering in rural areas, as in the Sahel today. Ethnic-based regionalist and secessionist movements seeking autonomy tend to rely the most on rural populations, since one of their primary objectives is to seize territory seen as the group’s homeland

Source: Authors.

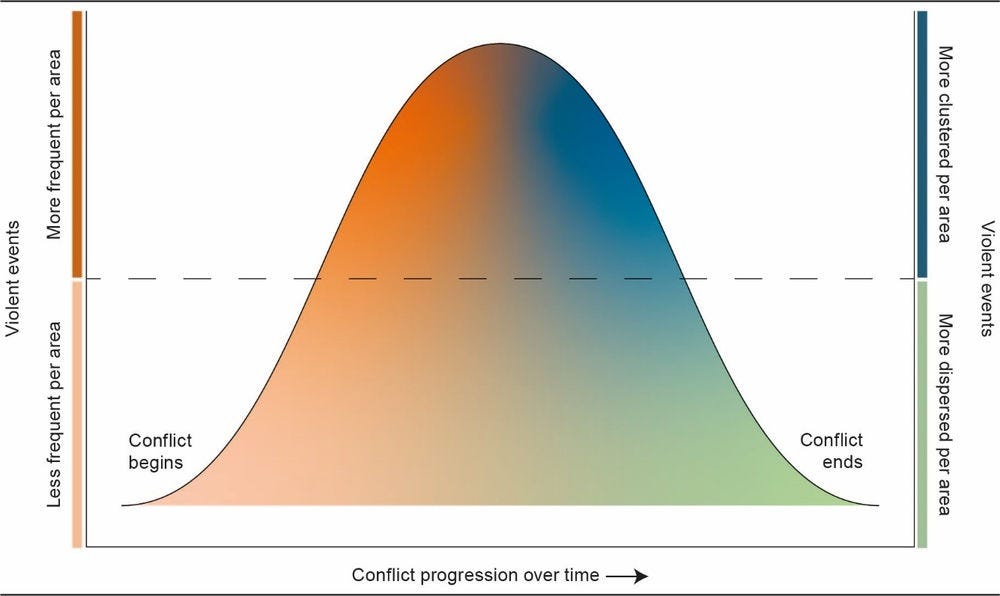

The fact that armed groups have vacillated between urban and rural areas in response to government opposition suggests that conflicts in North and West Africa may differ from the Maoist pattern. Previous research into the locations of political violence in the region has identified the concept of a conflict “spatial life cycle”, which may provide additional insight into why a conflict occurs where it does. The spatial life cycle theory notes that many conflicts exhibit distinct locational patterns in their early, middle and late stages (Walther et al., 2021[56]). For example, the locations of violent events tend to be dispersed from one another, with events that also occur less frequently in each area during the beginning and concluding stages of a conflict. Conversely, violent events occurring during the middle stages of a conflict are often closely clustered together and tend to happen more frequently in an area (Figure 2.6).

What remains unknown is a fuller account of what produces the patterns summarised by the spatial life cycle theory. Urban-rural conflict patterns may indeed be related. For example, if the beginning and ending stages of a conflict tend to be more rural, that could help explain the dispersal and lower frequency of violent events common to those phases, as fewer targets are likely to be present in less populated areas (resulting in lower event frequency) with more distance between those targets that are present (resulting in more event dispersal). And if violence tends to move into urban areas during a conflict’s middle stage, it could help to explain the tendency for violence to cluster and increase in frequency. From this perspective, a closer understanding of the region’s urban-rural conflict trajectories has the potential to fill in some of the process that leads to the patterns of the spatial life cycle.

Figure 2.6. The conflict life cycle

Source: Authors.

References

[33] ACLED (2021), Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (database), https://acleddata.com.

[19] AfDB-UEMOA (2017), Benin/Togo multinational Project to Upgrade the Lomé-Cotonou route and Facilitate Trade and Transport on the Abidjan-Lagos corridor, African Development Bank, http://www.afdb.org.

[60] Agbiboa, D. (2022), Mobility, Mobilization, and Counter/Insurgency: The Routes of Terror in an African Context, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11472497.

[5] Allen, T. and P. Heinrigs (2016), “Emerging Opportunities in the West African Food Economy”, West African Papers, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlvfj4968jb-en.

[4] Banjo, G., H. Gordon and J. Riverson (2012), “Rural transport: Improving its contribution to growth and poverty reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa”, World Bank SSATP Working Paper 93.

[30] Beall, J., T. Goodfellow and D. Rodgers (2013), “Cities and conflict in fragile states in the developing world”, Urban Studies, Vol. 50/15, pp. 3 065–3 083.

[7] Berg, C., B. Blankespoor and H. Selod (2018), “Roads and rural development in Sub-Saharan Africa”, The Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 54/5, pp. 856–874.

[54] Bossard, L. (2015), “Les régions maliennes de Gao, Kidal et Tombouctou. Perspectives nationales et régionales”, Paris, OECD Sahel and West Africa Club.

[53] Buhaug, H., S. Gates and P. Lujala (2009), “Geography, rebel capability, and the duration of civil conflict”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 53/4, pp. 544–569.

[24] Buhaug, H. and J. Rød (2006), “Local determinants of African civil wars, 1970–2001”, Political Geography, Vol. 25/3, pp. 315–335.

[37] Buhaug, H. and H. Urdal (2013), “An urbanization bomb? Population growth and social disorder in cities”, Global Environmental Change, Vol. 23/1, pp. 1–10.

[31] Büscher, K. (2018), “African cities and violent conflict: The urban dimension of conflict and post conflict dynamics in Central and Eastern Africa”, Journal of Eastern African Studies, Vol. 12/2, pp. 193–210.

[47] Chivvis, C. (2015), The French War on Al Qa’ida in Africa, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[21] Coquery-Vidrovitch, C. (1993), Histoire des villes d’Afrique noire : Des origines à la colonisation, Albin Michel, Paris.

[23] Corker, J. (2017), “Fertility and child mortality in urban West Africa: Leveraging geo-referenced data to move beyond the urban/rural dichotomy”, Population, Space and Place, Vol. 23/3, p. e2009, https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2009.

[27] Dorward, N. (2022), Essays on the geography of contentious collective action in Africa, University of Bristol, unpublished PhD dissertation.

[59] Galula, D. (1963, 2006), Pacification in Algeria, 1956-1958, Rand Corporation, Santa Barbara, California.

[39] Gizelis, T., S. Pickering and H. Urdal (2021), “Conflict on the urban fringe: Urbanization, environmental stress, and urban unrest in Africa”, Political Geography, Vol. 86/6, p. 102 357.

[36] Golooba-Mutebi, F. and A. Sjögren (2017), “From rural rebellions to urban riots: political competition and changing patterns of violent political revolt in Uganda”, Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, Vol. 55/1, pp. 22–40.

[32] Goodfellow, T. and D. Jackman (2020), “Control the capital: Cities and political dominance”, Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre Working Paper 135.

[29] Graham, S. (2011), Cities under siege: The new military urbanism, Verso Books, London.

[46] Harding, R. (2020), “Who is democracy good for? Elections, rural bias, and health and education outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa”, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 82/1, pp. 241–254.

[49] Hendrix, C. (2011), “Head for the hills? Rough terrain, state capacity, and civil war onset”, Civil Wars, Vol. 13/4, pp. 345–370.

[52] Herbst, J. (2000), States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

[48] Holmes, J. (2015), “The urban guerrilla, terrorism, and state terror in Latin America”, in Law, R. (ed.), The Routledge History of Terrorism, Routledge, New York.

[34] HRW (2012), “Mali: Islamist Armed Groups Spread Fear in North”, Human Rights Watch, 25 September.

[10] Karg, H. et al. (2019), “Small-town agricultural markets in Northern Ghana and their connection to rural and urban transformation”, The European Journal of Development Research, Vol. 31/1, pp. 95–117.

[40] Krause, J. (2018), Resilient Communities: Non-violence and Civilian Agency in Communal War, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[42] Menashe-Oren, A. (2020), “Migrant-based youth bulges and social conflict in urban sub-Saharan Africa”, Demographic Research, Vol. 42, pp. 57–98.

[3] Minten, B., T. Reardon and K. Chen (2017), “Agricultural value chains: How cities reshape food systems”, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) Global Food Policy Report, pp. 42–49.

[26] Mkandawire, T. (2002), “The terrible toll of post-colonial ‘rebel movements’ in Africa: Towards an explanation of the violence against the peasantry”, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 40/2, pp. 181–215.

[55] Niger Institute of Statistics (2022), Statistiques par région, http://www.stat-niger.org.

[20] Nugent, P. (2022), “When is a corridor just a road? Understanding thwarted ambitions along the Abidjan–Lagos corridor”, in Lamarque, H. and P. Nugent (eds.), Transport Corridors in Africa, Boydell and Brewer, Martlesham, pp. 211-230.

[17] Nugent, P. (2019), Boundaries, Communities and State-making in West Africa: The Centrality of the Margins, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[22] OECD, UNECA, AfDB (2022), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2022: The Economic Power of Africa’s Cities, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3834ed5b-en.

[1] OECD/SWAC (2020), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en.

[13] OECD/SWAC (2019), “Population and Morphology of Border Cities”, West African Papers, No. 21, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/80dfd9d8-en.

[18] OECD/SWAC (2017), Cross-border Co-operation and Policy Networks in West Africa, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264265875-en.

[15] OECD/SWAC (2014), An Atlas of the Sahara-Sahel: Geography, Economics and Security, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264222359-en.

[38] Østby, G. (2016), “Rural–urban migration, inequality and urban social disorder: Evidence from African and Asian cities”, Conflict Management and Peace Science, Vol. 33/5, pp. 491–515.

[8] Owusu, G. (2008), “The role of small towns in regional development and poverty reduction in Ghana”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 32/2, pp. 453–472.

[28] Radil, S. et al. (2022), “Urban-rural geographies of political violence in North and West Africa”, SSRN 4171240, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4171240.

[45] Raleigh, C. (2015), “Urban violence patterns across African states”, International Studies Review, Vol. 17/1, pp. 90–106.

[50] Raleigh, C. (2010), “Seeing the forest for the trees: Does physical geography affect a state’s conflict risk?”, International Interactions, Vol. 36/4, pp. 384–410.

[25] Raleigh, C. and H. Hegre (2009), “Population size, concentration, and civil war: A geographically disaggregated analysis”, Political Geography, Vol. 28/4, pp. 224–238.

[14] Retaillé, D. (1989), “Comment lire le contact Sahara-Sahel”, in Ministère de la Coopération (ed.), De l’Atlantique à Ennedi, Ministère de la Coopération and Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

[51] Sangaré, B. and S. Cold-Ravnkilde (2020), “Internally displaced people in Mali’s capital city”, Danish Institute for International Studies Policy Brief, 8 December.

[2] Staatz, J. and F. Hollinger (2016), “West African Food Systems and Changing Consumer Demands”, West African Papers, No. 4, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b165522b-en.

[43] Staniland, P. (2010), “Cities on fire: social mobilization, state policy, and urban insurgency”, Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 43/12, pp. 1 623–1 649.

[44] Straus, S. (2012), “Wars do end! Changing patterns of political violence in sub-Saharan Africa”, African Affairs, Vol. 111/443, pp. 179–201.

[9] Tacoli, C. and J. Agergaard (2017), “Urbanisation, Rural Transformations and Food Systems: The Role of Small Towns”, Working Paper, International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

[58] Tse-Tung, M. (1937, 2005), On Guerrilla Warfare, Courier Corporation, North Chelmsford, U.K.

[12] UN (2021), World Population Prospects 2019, United Nations, Department of Social and Economic Affairs, Population Division, New York.

[41] Urdal, H. and K. Hoelscher (2012), “Explaining urban social disorder and violence: An empirical study of event data from Asian and sub-Saharan African cities”, International Interactions, Vol. 38/4, pp. 512–528.

[61] Walker, A. (2012), What is Boko Haram?, U.S. Institute of Peace, Vol. 17, Washington, D.C.

[11] Walther, O. (2021), “Urbanisation and demography in North and West Africa, 1950-2020”, West African Papers, No. 33, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4fa52e9c-en.

[6] Walther, O. (2015), “Business, brokers and borders: The structure of West African trade networks”, The Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 51/5, pp. 603–620.

[56] Walther, O. et al. (2021), “Introducing the Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator of political violence”, Terrorism and Political Violence, pp. 1–20, http://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1957846.

[16] Walther, O. and D. Retaillé (2021), “Mapping the Sahelian space”, in Villalón, L. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the African Sahel, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 15–34.

[57] Watts, M. (2004), “Resource curse? Governmentality, oil and power in the Niger Delta, Nigeria”, Geopolitics, Vol. 9/1, pp. 50–80.

[35] Williams, P. (2016), War and Conflict in Africa, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

Note

← 1. This section builds on OECD/SWAC (2019[13]) and Walther (2021[11]).