This chapter presents a policy roadmap for making early childhood education and care (ECEC) responsive to digitalisation. It discusses the main challenges brought about by digitalisation for ECEC and then provides a roadmap of policies to address these key challenges, building on the policy directions stemming from the report’s findings. It also identifies examples of countries that are relatively active in some of these policy areas to inform policy reflection in other countries.

Empowering Young Children in the Digital Age

1. Making early childhood education and care responsive to digitalisation: A policy roadmap

Abstract

Introduction

Digitalisation is transforming education and social and economic life, with far-reaching implications for today’s children. Studies across countries show young children interacting with digital technologies with increasing frequency and precocity, and the range of their digital activities broadening with age. The evidence base on the effects that these digital experiences have on children’s development and well-being is still incipient and inconclusive, but the stakes are high. The accelerating pace of digitalisation urges policy makers, educators and families to identify effective ways to protect children while equipping them to thrive in the digital age. Early childhood education and care (ECEC), with its immense potential to shape children’s early development, learning and well-being, can play a significant role in addressing the opportunities and risks of digitalisation for young children.

Furthermore, digitalisation brings new ways of working, communicating and networking and amplifies the power of data, all of which are relevant for the ECEC sector, as for other levels of education and other sectors of activity more generally. Digitalisation brings many challenges but also solutions for modernising work processes, expanding opportunities for workforce training and developing quality assurance processes.

This report provides a 360-degree view of the challenges and opportunities brought about by digitalisation for ECEC and of the possible policy responses. This chapter summarises the policy directions stemming from the report’s findings and provides a roadmap of policies to address the key challenges. It also identifies examples of countries that are active in some of these policy areas to inform policy reflection in other countries. However, the report recognises that given the lack of evidence, the rapidness of changes in this space and the varied contexts of ECEC systems across countries, ECEC policies can respond to digitalisation at different paces and in different directions.

Key digitalisation challenges for early childhood education and care

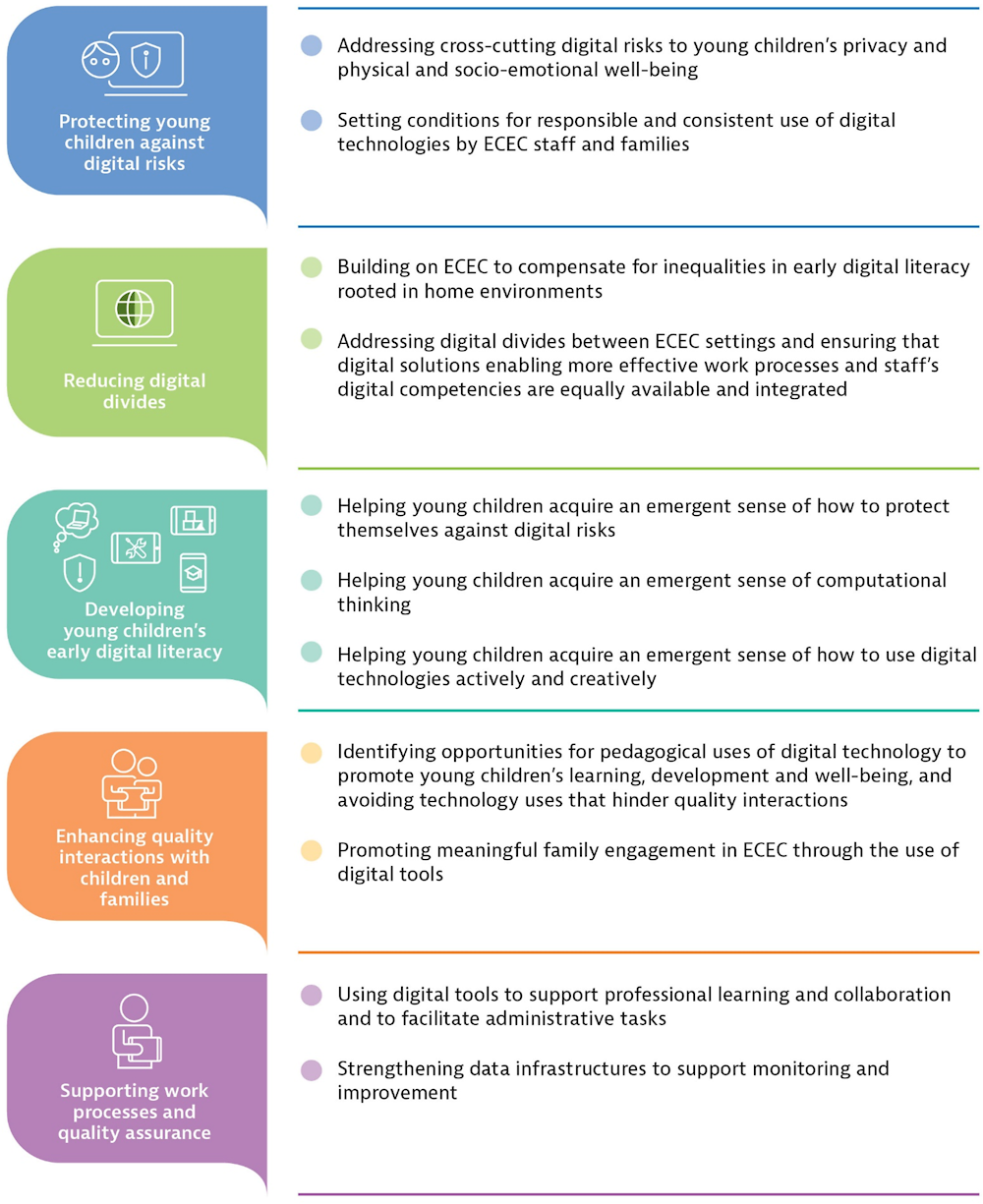

Digitalisation engenders complex and multi-faceted challenges for ECEC, which can be summarised in five key areas (Figure 1.1). Countries value these challenges differently depending on their policy priorities, views on the role and objectives of ECEC, and the context and history of their ECEC policies.

The first challenge is to protect young children against digital risks, addressing their limited awareness of risks and protective behaviours in digital environments. This is a serious concern indicated by the 26 countries and jurisdictions that responded to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) (see Chapter 2). A second challenge is to mitigate digital divides: divides between children, compensating for unequal access to quality resources and unequal experience with positive digital mediation in home environments; and divides between ECEC settings, enabling more effective work processes in all settings. These are key reasons to make ECEC responsive to digitalisation. The third challenge concerns laying the foundations for young children to develop their digital literacy, attending to its multiple dimensions and without detriment to other curricular goals. The fourth challenge relates to enhancing the quality of the interactions children experience in ECEC settings and between the ECEC workforce and children’s families to promote their cognitive and socio-emotional development in the digital age. The fifth challenge is to mobilise digital tools and data to improve opportunities for professional learning and collaboration among ECEC staff, as well as for quality monitoring and service co-ordination. This might be a less controversial challenge than some of the others, but it is important given the characteristics of ECEC settings and staff.

Figure 1.1. Five key challenges for early childhood education and care in the digital age

These five challenges highlight the close intertwinement between digital opportunities and risks and the need for policy solutions that strike a careful balance between the two. Risks are inherent to an increasing reliance on digital tools, from young children’s extended screen time to growing digital divides and diverting the focus from the in-person interactions that constitute the core of high-quality ECEC. However, preparing all young children to engage in safe and creative uses of digital technology can be an effective strategy for reducing most of these risks. Supporting staff to integrate digital tools into their work selectively and meaningfully can open the door to quality improvements. Making ECEC responsive to digitalisation involves managing rather than trying to eliminate these risks and exploring rather than ignoring these opportunities.

Addressing these five challenges also involves paying attention to age differences among young children. The age gradient in early development requires age-specific and evolving responses, with little exposure to digital tools for children between birth and age 3 and a growing emphasis on children’s experience with digital tools as a foundation for digital literacy as children get older.

Fifteen policy pointers to make early childhood education and care responsive to digitalisation

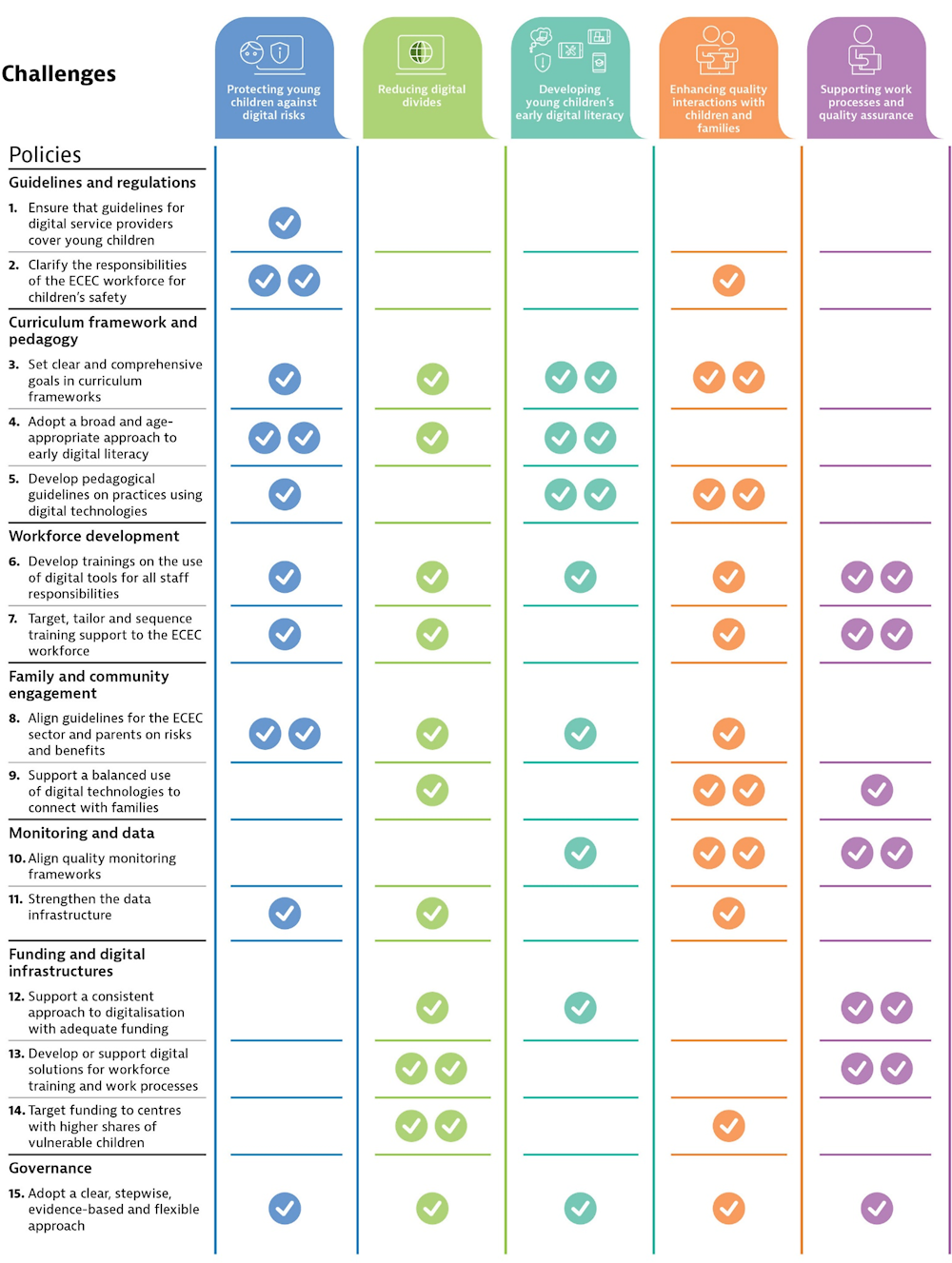

Research consistently underscores the importance of ensuring ECEC is of high quality to support children’s development and well-being and to realise the numerous benefits of investing in this period of the life course (OECD, 2021[1]). The new challenges and opportunities brought about by digitalisation call for reviewing the main policy areas to promote quality ECEC. Drawing on the policy levers of the Starting Strong framework, this report identifies 15 policy pointers to meet the 5 key challenges in making ECEC responsive to digitalisation (see Figure 1.2 and Box 1.1).

Countries put different weights on these challenges (see Chapter 2) and there can be rationales for focusing on a limited number of challenges, at least in the short run. The roadmap can help inform these choices by identifying policy pointers to address each of these challenges. However, the roadmap also shows that even when focusing on a particular challenge, a broad policy approach that combines actions across multiple policy levers is recommended. Another way to look at the roadmap is to consider all policy levers simultaneously and identify directions to update these policies in light of digitalisation. This would lead to a comprehensive strategy for making ECEC responsive to digitalisation. However, care is needed when revisiting one policy lever alone, as this can lead to inconsistencies in the approach, such as setting ambitious goals in curriculum frameworks without adequately preparing the ECEC workforce.

Box 1.1. Methodology of the policy roadmap

This policy roadmap draws on a variety of sources to identify policy challenges, pointers and examples. The five key challenges for ECEC in the digital age are derived from an analysis of the associations between specific challenges regarding digitalisation, young children and ECEC presented in Chapter 2 of this report. The 15 policy pointers synthesise strategies, across multiple policy levers, from the specific policy directions discussed in the concluding sections of Chapters 3-8. Countries and jurisdictions implementing relevant policy developments, as well as examples of specific programmes or initiatives, at multiple levels, are identified based on information provided through the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey and the project case studies. More detailed information on the methodology is provided in Annex A.

Figure 1.2. A policy roadmap to respond to key digitalisation challenges in early childhood education and care

Notes: This figure presents a summary of the policy pointers identified in the report. A discussion of the policy pointers can be found at the end of each chapter of the report. These are short versions of each policy pointer. For more details on each policy pointer, see Table 1.1. Two check marks indicate a direct strong link between the policy pointer and the challenge. One check mark indicates an indirect, weaker link.

Guidelines and regulations should set the preconditions for any use of digital technologies in ECEC settings

Guidelines and regulations for digital service providers need to include dispositions relating specifically to young children, apply to any type of digital technology or service amenable to use in ECEC settings, and set some responsibilities on digital service providers for protecting young children’s safety and well-being in digital environments (Policy Pointer 1). The responsibilities of the ECEC workforce for protecting children against digital risks need to be clarified and spelt out, depending on their role, children’s age and type of ECEC setting (Policy Pointer 2). These are preconditions for digital technologies to be used in ECEC settings, including for collecting or processing their personal data, and for ECEC professionals to have clear standards about digital safety in their work.

Policies around curriculum frameworks and workforce development are at the core of the response of ECEC to digitalisation

Curriculum frameworks can set clear goals for ECEC in light of the digital transformation. These goals can be comprehensive and reflect the broad impact of digitalisation on children’s development, learning and well-being rather than focusing only on the use of digital technologies (Policy Pointer 3). The holistic approach of ECEC that aims to support comprehensive cognitive, social and emotional developments is well-aligned with a 21st century curriculum. In addition, curriculum frameworks and other documents, such as digital education strategies, can set clear goals for children’s early digital literacy development and adopt a broad view on digital literacy (Chapter 4), including on how technology works (computational thinking); developing risk awareness and safe behaviours in the use of technology; and learning to use technology in support of play, creativity and self-expression (Policy Pointer 4).

ECEC professionals hold most of the responsibilities for providing a mix of care and education that aligns with the evolving goals set by curriculum frameworks. Developing pedagogical guidelines for digital practices with children and choosing digital materials aligned with curriculum goals can help them implement these frameworks (Policy Pointer 5). ECEC professionals also have large responsibilities for documenting children’s development, learning and well-being; engaging with families; ensuring compliance with standards; and engaging in continuous professional development. Digitalisation has implications for all these processes. Providing training opportunities for ECEC staff on the use of digital technologies for the breadth of their responsibilities, both in initial preparation programmes and continuous professional development, is a key policy action (Policy Pointer 6). The timing and content of the training for the ECEC workforce to develop digital competencies must be carefully considered. This training needs to come prior to or in parallel with the introduction of policies that aim to adapt ECEC to digitalisation. Not all staff need to develop the same set of digital competencies. All staff should acquire foundational knowledge on how digital technologies can be safely and meaningfully integrated into ECEC settings, but some staff could develop enhanced and specialised digital competencies to meet greater responsibilities in some aspects of their work (e.g. initiating creative work with children in a digital space or using data to improve monitoring or management) (Policy Pointer 7).

Digitalisation is an additional reason for ECEC to engage with parents but is also a tool

Family and community engagement are becoming even more important as digital technologies become a fixture of children’s home environments, bringing new risks but also new opportunities for play, learning and socialisation. Guidance for parents that generally focuses on risks can be complemented by information about the opportunities and educational uses of digital technologies and therefore be better aligned with objectives for the ECEC sector (Policy Pointer 8). This can reduce the potential dissonance between digital attitudes and practices in ECEC and in home environments. Additionally, digital technologies offer opportunities to facilitate more frequent and wider communication with parents, communities and other institutions in charge of education and young children (Policy Pointer 9).

Improved monitoring and data use and adequate funding and investment in infrastructures can support responses to digitalisation in ECEC

As ECEC policies are modified or adapted in response to digitalisation, monitoring frameworks should reflect these changes. For instance, the implementation of changes to the curriculum framework and pedagogical approaches on process quality and on learning, development and well-being should be monitored. The quality of ECEC workforce training on digital competencies also needs to be monitored (Policy Pointer 10). At the same time, digitalisation brings new tools for monitoring the equity and quality of ECEC. The data infrastructure can be strengthened through improved data collection and data sharing, enabling a wider range and more actionable uses of ECEC data (Policy Pointer 11). This also implies paying greater attention to data security and privacy protection in ECEC.

A consistent approach to ECEC and digitalisation requires adequate funding to support workforce training in particular (Policy Pointer 12). Governments can ensure that all ECEC settings have access to the needed solutions (e.g. digital infrastructures and materials, material for unplugged approaches) for work processes and uses with children (Policy Pointer 13).

Promoting equal opportunities and inclusion in ECEC are key reasons for making ECEC responsive to digitalisation

For many children, digital divides are already emerging in early childhood, driven by differences in the level of digital resources and digital skills in their family environments. ECEC can play a role in redressing these inequalities by providing opportunities to build early digital literacy for all children. Furthermore, the potential for digital technologies to improve a range of work practices is particularly important for centres with a high proportion of disadvantaged children or a lack of financial and human resources. Finally, digitalisation can also help promote more inclusive and responsive practices for learning and development. For these reasons, funding for digital infrastructure and related workforce training can be targeted to centres with larger shares of children from disadvantaged backgrounds, and on how to better reach out to and increase the engagement of their families in ECEC (Policy Pointer 14).

The policy response needs to take children’s age into account

There are multiple facets to the question of making ECEC responsive to digitalisation. Some call for age-specific policy responses while others hold for young children generally.

An important argument is around making ECEC more anchored in today’s childhood and ready to prepare children for the future. The ability to learn, capacity to solve problems with complex sets of information and creative thinking are viewed as crucial skills in a rapidly changing environment. ECEC can adapt to these changes. While practices with children to support these developmental areas depend on the children’s age, the goal holds for the entire education sector, including for very young children.

Another facet is that children should become digitally literate. This report adopts the notion of “early digital literacy”, which is about laying the foundations of digital literacy, and can be seen as including several dimensions (see Chapter 4): getting a sense of how to protect oneself against digital risks; how to use digital technologies for play, self-expression and learning; and how a computer works (computational thinking). Likewise, while practices to support these developmental areas depend on the children’s age, the goal holds for all children.

Using digital technologies with children to support the development of early digital literacy or other areas of development calls for an approach differentiated by age. Approaches that can support early digital literacy without exposure to screens, such as robotic kits and “unplugged approaches”, are well-suited for ECEC children, especially the youngest ones. When digital technologies are used with children in ECEC settings, research points to usages that make children active and interact with others, and not in place of other activities. These situations might be more difficult to realise in ECEC settings with the youngest children. Responses to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) indicate that governments tend to invest in materials that can lead to passive uses if not well integrated into an age-appropriate pedagogical approach.

Uncertainties call for a balanced but consistent and timely approach

Many risks come to mind when planning to make ECEC responsive to digitalisation: young children’s passive and excessive exposure to screens, displacement of meaningful in-person interactions with children, ineffective communication with families through digital channels, or privacy violations in the processing of children’s or staff’s personal data. Not only is robust scientific evidence lacking on many aspects, but the speedy pace of developments also turns many questions into moving targets. Uncertainties relating to the impact of digital technologies on children and ECEC and to the effectiveness of potential policy responses are therefore bound to persist. Nonetheless, attempts to fully isolate ECEC from digitalisation appear futile and countries’ responses to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey indicate that preserving ECEC as a space where children have no contact with digital technology is not a priority.

This report explores the various policy levers for ECEC to prepare children for a digital world and build on digitalisation for better ECEC quality. The policy response needs to be proportionate to the capacity of the sector to adapt. In many countries, the ECEC sector has a number of fragilities relating to the lack of resources, the heterogeneity of the workforce and the inherent difficulties of providing high-quality experiences for young children. There is no single direction and countries can have different objectives. However, it is important that the goals of ECEC responses to digitalisation are clear and articulated around an approach that involves all relevant stakeholders, is informed by the best available evidence, and can be implemented gradually and flexibly (Policy Pointer 15). The timing of the adaptation is important. Infrastructure in a broad sense – including digital solutions, funding and workforce training – have to be in place to accompany change in curriculum frameworks and pedagogical approaches. Monitoring needs to follow.

Learning from countries on the multiple strategies

This report does not take a stance on how far countries should go in their response to digitalisation. Each country is transforming its ECEC policies to account for digitalisation at its own pace. The landscape can also change quickly, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to an expansion in the use of digital technologies to maintain children’s learning as centres were closed, to engage with parents and to support ECEC workforce training.

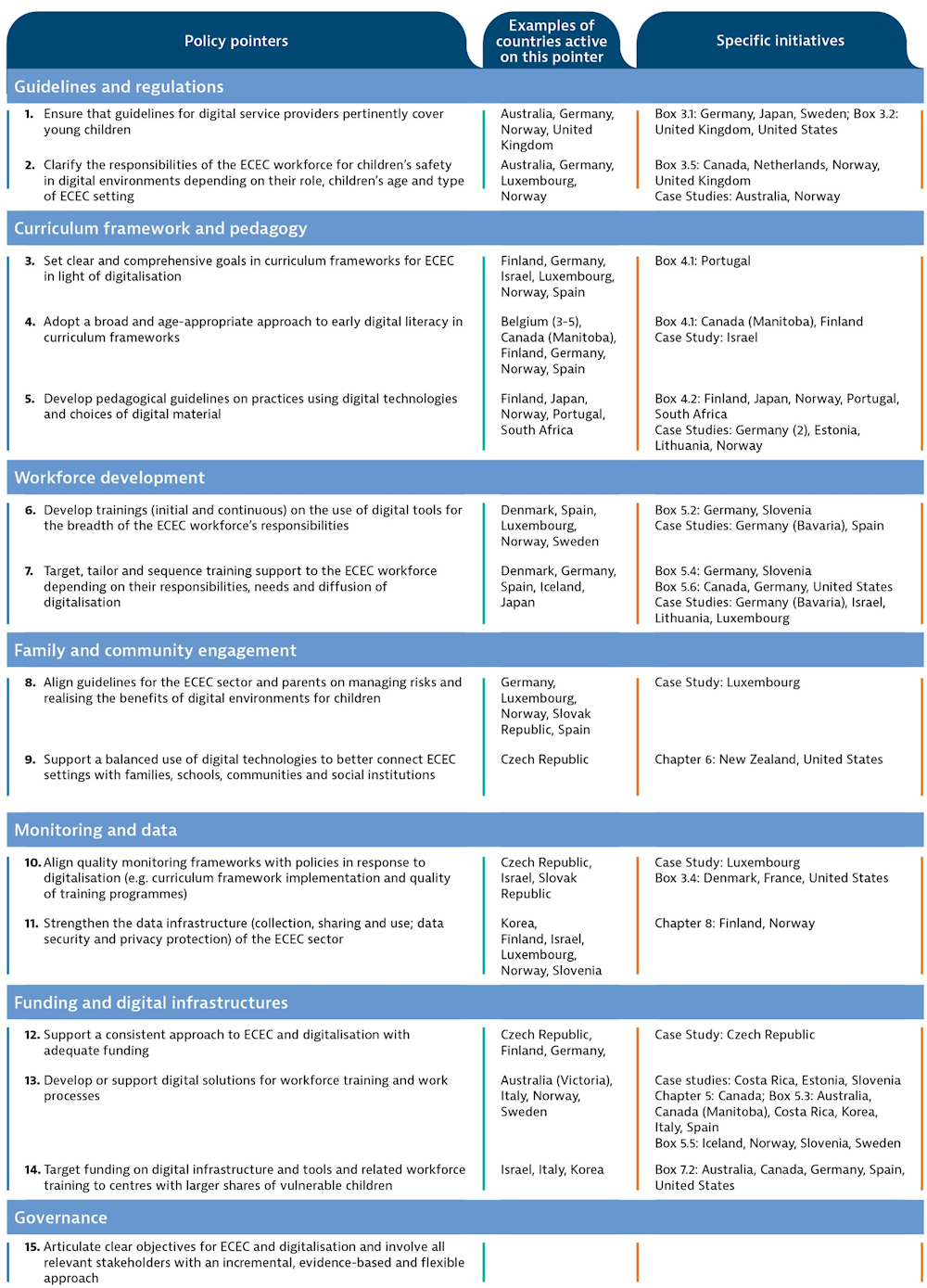

The roadmap identifies examples of countries that are active on some policy pointers and may provide peer-learning experiences to other countries (Table 1.1). The report and its compendium of case studies provide multiple examples of policy initiatives that are also indicated in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Policy pointers for making early childhood education and care responsive to digitalisation and country examples

Notes: Countries and jurisdictions “active” for these policy pointers are selected following an approach that combines answers to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) and analysis presented in the chapters of this report. “Specific initiatives” point to case studies of the compendium and parts of the report. Initiatives can be at any level, not necessarily at the country level.

Canada (Manitoba): kindergarten sector only.

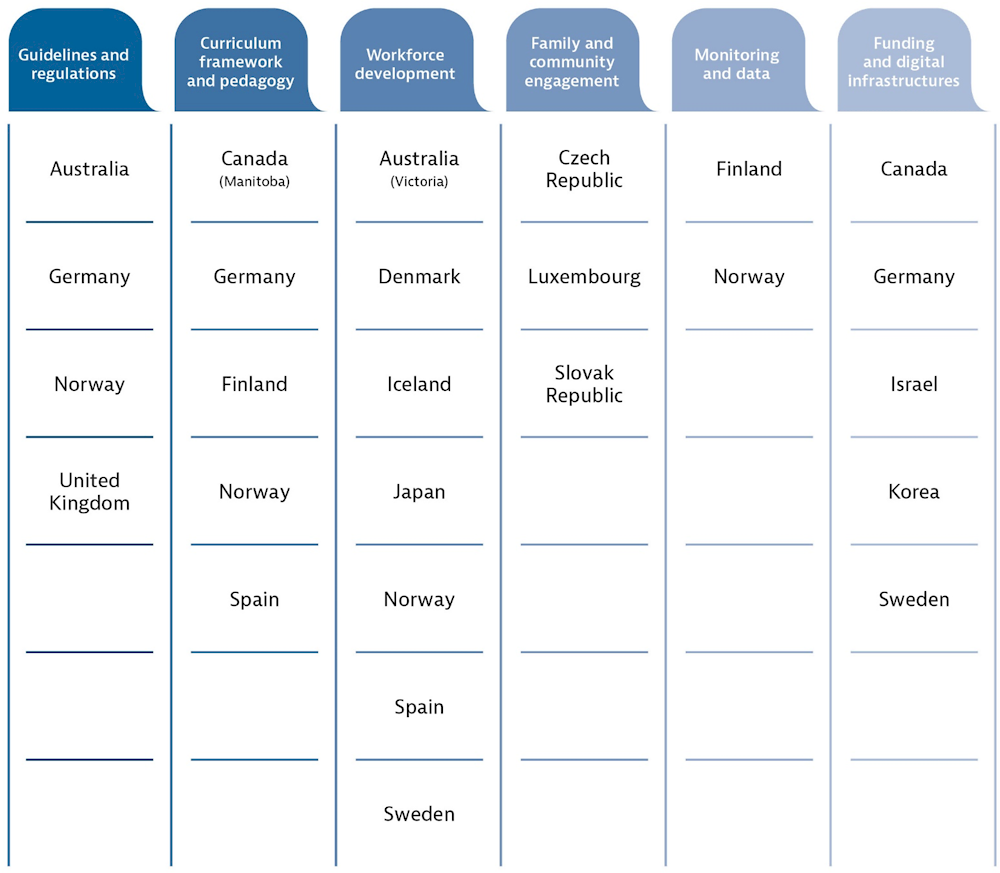

Examples of countries active in a specific policy lever

Some countries are particularly active in at least one of the five policy levers (Table 1.2). This information can be helpful to countries that have identified areas of policies for which they plan to do more to make ECEC responsive to digitalisation.

Answers to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) and analysis carried out for this report show that several countries are implementing policies and initiatives to prepare the workforce for changing demands brought about by the digital transformation. The ECEC workforce can create momentum for adopting modernised work processes and preparing children for the digital age. Furthermore, several countries invest in workforce training and infrastructures relating to digitalisation. However, funding needs to be sufficient and part of it should target centres with the least favourable conditions. Ensuring that the monitoring framework is adjusted to include goals of ECEC relating to digitalisation and workforce development on digital technologies remains a priority in many countries.

Table 1.2. Which countries are active in a particular policy lever?

Note: Countries and jurisdictions “active” for these policy levers are “active” for multiple policy pointers of the policy lever according to answers to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) and analysis presented in this report. Canada (Manitoba): kindergarten sector only.

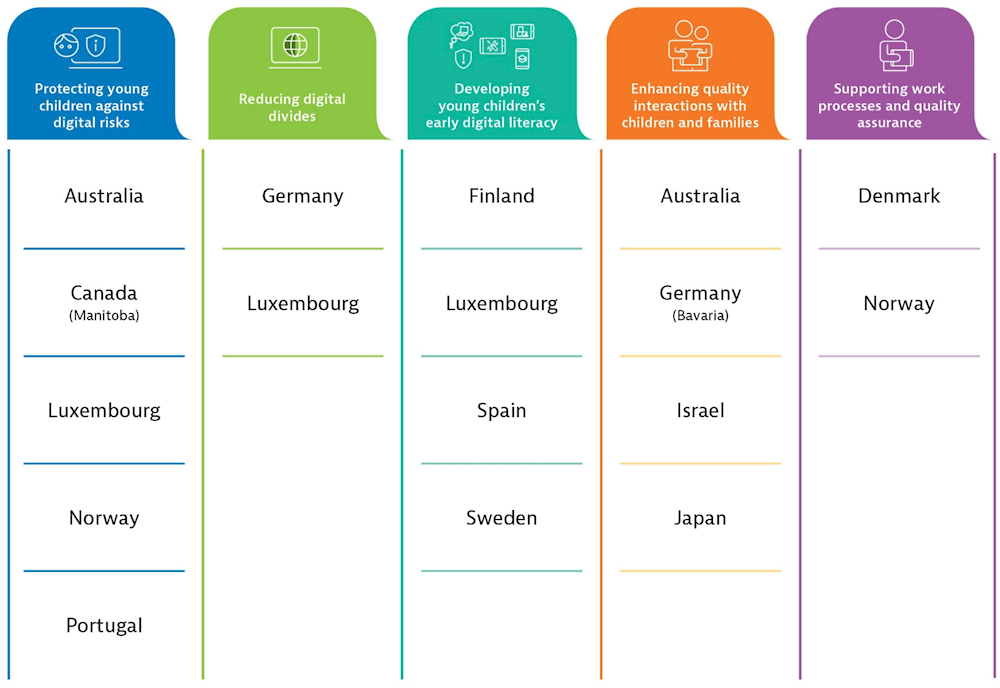

Examples of countries combining multiple policies to address a particular challenge

Some countries have implemented a mix of policies related to the same challenge. These countries offer opportunities for learning how to address a particular challenge through a consistent set of policies.

Protecting children against digital risks is a challenge for which some countries appear to advance with a consistent set of policies. This is also the challenge ranked the highest by countries participating in the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022). For other challenges, not many countries can be identified as putting forward a comprehensive policy response.

Table 1.3. Which countries have a set of policies to address a particular challenge?

Notes: Countries and jurisdictions shown are “active” on policy pointers that address the same challenge (see Table 1.1) according to answers to the ECEC in a Digital World policy survey (2022) and analysis presented in this report. Canada (Manitoba): kindergarten sector only.

Going forward

Even more than higher levels of education, ECEC systems around the world respond to the challenges brought about by digitalisation with thin evidence on its impact on young children, and in the context of rapidly evolving technological developments and broader questions on how to design ECEC policies that benefit all children equally. This report presents a snapshot of countries and jurisdictions’ policy responses as of 2022 and a synthesis of research to propose possible policy directions. Further research and analysis will be needed to strengthen the evidence base and provide additional policy insights. Among the priorities for follow-up work could be investigating in greater detail implications for different age groups of young children, capitalising on the data generated by the monitoring of current policy initiatives, paying close attention to the voices of the ECEC workforce as new policies are introduced, and better understanding connections between the dynamics of digitalisation in ECEC settings and in home environments.

Reference

[1] OECD (2021), Starting Strong VI: Supporting Meaningful Interactions in Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f47a06ae-en.