As in other OECD countries, Korea’s system of unemployment support has developed in the context of specific economic and political circumstances and trends. Yet, a number of key challenges and policy trade‑offs are shared across countries. To inform the reform agenda in Korea, this section compares policy designs and outcomes in Korea with other OECD members.

Benefit Reforms for Inclusive Societies in Korea

4. Policy designs and outcomes in the OECD: How does Korea compare?

4.1. Reach of unemployment benefits

4.1.1. Benefit coverage among jobseekers: International comparison and recent trends

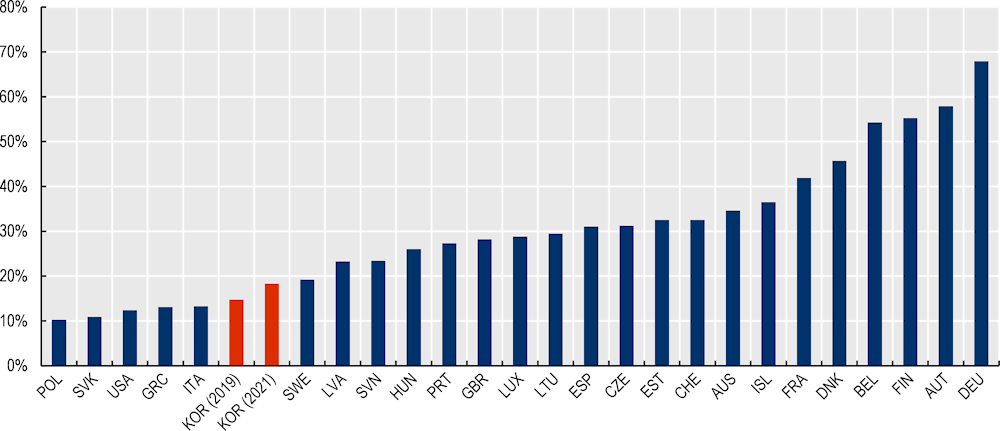

As the Korean unemployment benefit system matured, EI membership of workers has seen an upwards trend, but significant gaps have remained and were among the principal drivers of the 2020 roadmap for EI reform (see section 3 and Figure 3.1). Not all workers have the same unemployment risk, and EI membership does not automatically translate into benefit entitlement upon unemployment. Both in a national and in a comparative perspective, the share of jobseekers who receive income support in practice is therefore a particularly informative indicator of income security during unemployment. In Korea, only around 15% of unemployed jobseekers reported receiving unemployment benefits in 2019 in available survey data (Figure 4.1). Effective coverage rates were also low in several other countries, remaining below 30% in half of the countries shown. Korea’s rate increased notably between 2019 and 2021, in line with the reforms introduced (section 3.2). But the share of jobseekers reporting benefits nevertheless remained markedly lower than 2019 values in most comparator countries, and recipient numbers after the onset of COVID‑19 have increased in other countries as well (see below). Sources and definitions differ across countries and, in the case of Korea, data-related factors can push the estimates up or down relative to other countries (see figure notes). In particular, benefit receipt is measured over a longer time period than in other countries (which makes measured coverage comparatively higher in Korea), but it does not include receipt of unemployment assistance (which makes measured coverage comparatively lower in Korea).1

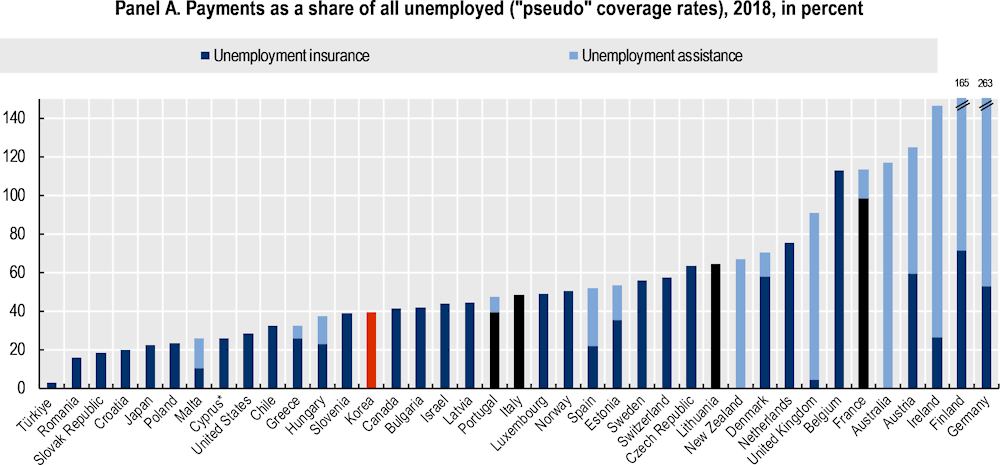

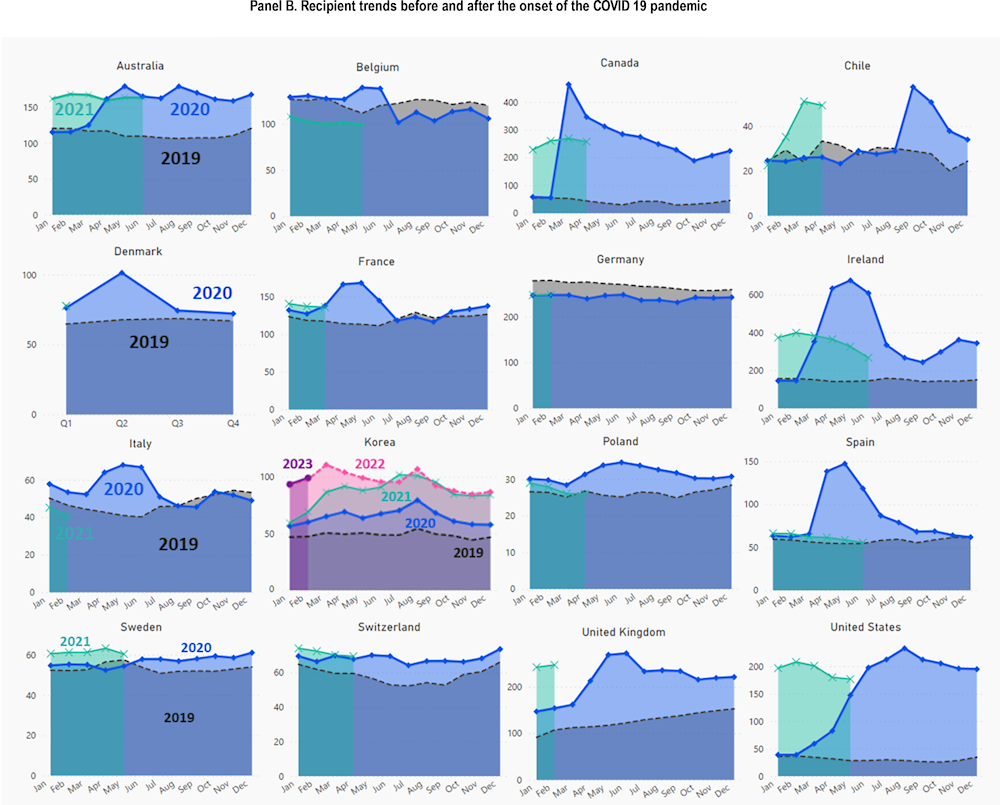

Benefit payment data from administrative sources point to higher recipient shares across OECD countries, including in Korea (Figure 4.2, Panel A). Korea’s position relative to comparator countries is, however, broadly similar for the two different measures. In most countries, the ratio of benefit payments from administrative sources and the number of unemployed is typically at least twice the survey-based coverage rates shown in Figure 4.1. This is because some underreporting in surveys is common, and also because a significant share of benefit payments can – intentionally or not – go to individuals who do not meet the standard definition of unemployment (OECD, 2018[36]). For instance, some benefit recipients may report that they are not actively looking for work, are unable to swiftly take up work when it is offered, or are already engaged in some work activities, such as part-time work. Figure 4.2 also shows that, as in several other countries, recipient rates in Korea have risen markedly since the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic and the introduction of the new unemployment assistance in 2021 (Panel B). The most recently available data indicate that coverage gains in Korea have persisted well into the post-COVID recovery phase.

Figure 4.1. Only a minority of jobseekers receive unemployment benefits

Notes: “Unemployed” refers to the standard ILO definition, i.e. out of work, actively looking for work, and available to start work. In the Korean survey data source (KLIPS), the relevant information is taken from variable “undertook job-seeking activities and able to work if suitable job was available”. In Korea, the relevant variable is “receipt of Job Seeking Allowance of Employment Insurance at any moment between previous and current interview” (which results in a higher number of recipients than the measure in other countries, which looks benefit receipt at the time of interview only). Recipients of unemployment assistance are not included as the information is not reported in KLIPS (ESPP, replaced by NESP in January 2021, see Box 3.1). The total number of recipients during 2018 was 1 062 933 for EI (KEIS, 2019[37]), and 308 290 for ESPP, including both Type‑I and Type‑II (MOEL, 2019[38]). Some European countries are excluded due to missing information in EU-LFS data. 2016 figures for United‑States, 2015 for Australia. LFS data for Sweden do not include a series of benefits that are accessible to jobless individuals who: i) are not in receipt of core unemployment benefits, and who ii) satisfy other conditions such as active participation in employment-support measures.

Source: KLIPS for Korea; Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) for Australia; European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) for European countries; Current Population Survey (CPS) for the United States.

Figure 4.2. Administrative data on benefit payments

Note: “Unemployed” refers to the standard ILO definition, i.e. out of work, actively looking for work, and available to start work. The numerator is the number of beneficiaries taken from administrative sources. The denominator is the number of unemployed as reported in labour force surveys (with the same source as in Figure 4.1). The results are commonly referred to as “pseudo” coverage rates as the population in the numerator and denominator do not fully overlap. For instance, in some countries, significant numbers of people who say they are not actively looking for work (e.g. discouraged jobseekers) may be able to claim unemployment benefits. Pseudo coverage rates can exceed 100% as a result (OECD, 2018[36]). Data for Korea prior to 2021 do not include recipients of unemployment assistance (“Job Search Promotion Allowance” of ESPP see Box 3.1) as the information was not available in the format required for the comparative OECD SOCR database. Recipients data for Korea in Panel B include unemployment assistance from 2021 onwards (NESP “Job Search Promotion Subsidy” or “Type‑I” support).

Source: Panel A: OECD Social Benefit Recipients Database (http://oe.cd/socr), Panel B: OECD SOCR, supplemented with NESP recipient data from the Employment Information Integrated Analysis System of the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

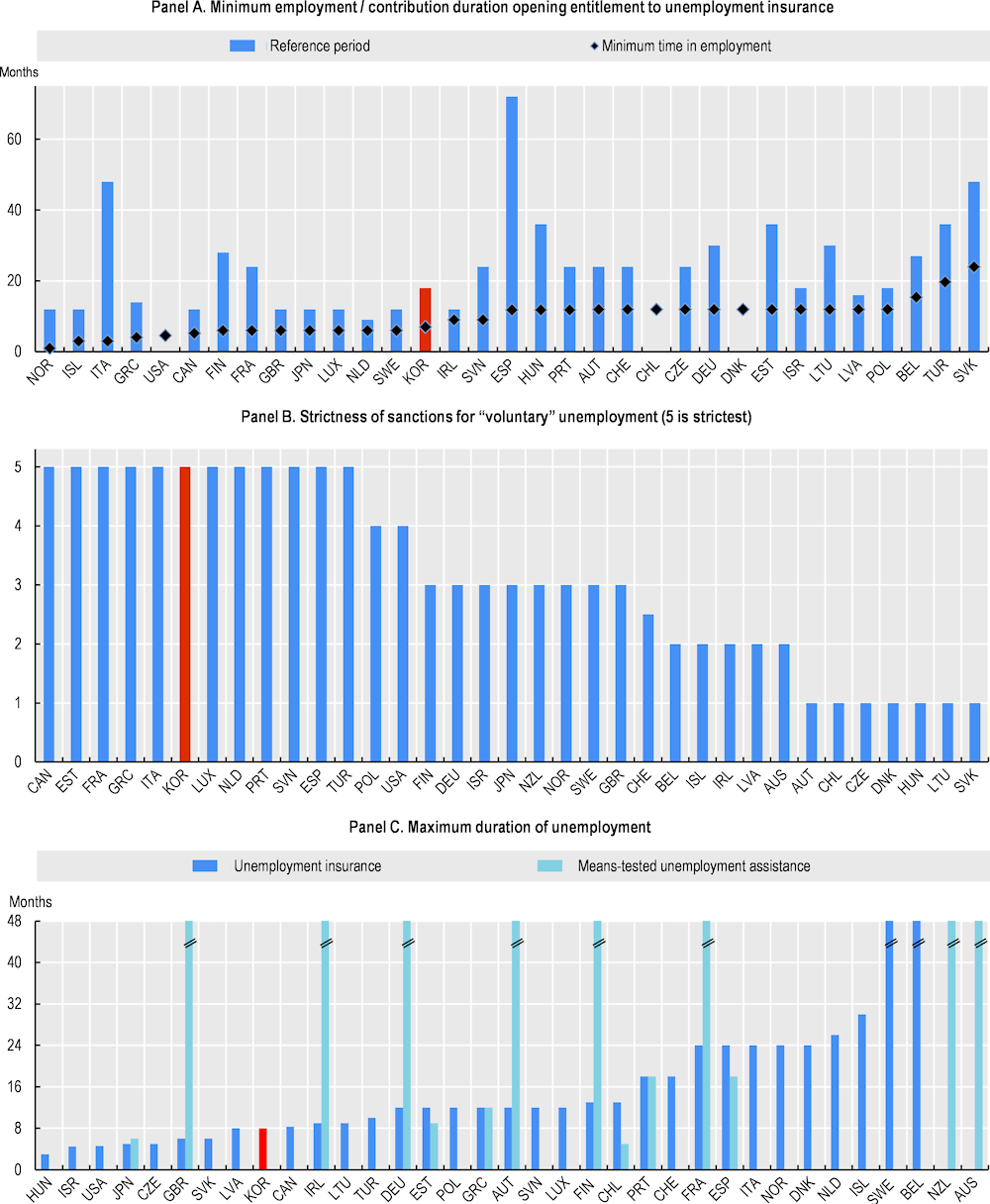

4.1.2. Entitlement conditions and benefit durations

Reasons for low benefit coverage among Korean jobseekers are complex and inter-related. Formal entitlement restrictions are one factor, including for the large number of non-standard workers, but also for regular dependent employees. In comparison with many OECD countries, the contribution period that is required for accessing benefits (ca. 7 months in 2020) is in fact not particularly long in absolute terms (Figure 4.3, Panel A). However, the reference period (the period prior to joblessness during which the contribution requirement needs to be satisfied) is also shorter than in some other countries (e.g. Italy, France, Finland, Slovenia, Spain). Moreover, a given contribution requirement, even a short one, is more likely to be binding in the context of Korea’s very short job tenures (with a median of just over 5 years, compared to an OECD average of just over 8 years, see Figure 2.2 and Table 2.1). According to information provided by the Ministry of Employment and Labour, a majority (75%) of EI members who became jobless did satisfy contribution requirements in 2022, but not necessarily all other eligibility conditions. 25% did not have sufficient contributions, and many others with short employment contracts may have sought to avoid EI membership if they considered it unlikely that they would qualify for EI benefits (see Figure 3.1).

Another factor driving coverage rates is the duration of benefit entitlements, which are comparatively short in international perspective (Figure 4.3, Panel C). Moreover, Korean jobseekers who are judged to have entered unemployment “voluntarily” are ineligible from the outset (Figure 4.3, Panel B). Across the OECD, about a third of countries also consider “voluntary” jobseekers as ineligible for unemployment benefits. Like other countries requiring involuntary unemployment, Korea has provisions that effectively extend EI entitlement to voluntary quits that are acknowledged as inevitable or otherwise legitimate (see Box 1). The new unemployment assistance (NESP), established in 2021, does not require involuntary unemployment (see section 3).

Worryingly, a long-standing problem of non-compliance has translated into large shares of workers who should have access to benefits when becoming unemployed, but who are not participating in the EI system for one reason or another, i.e. their employer did not register them and does not transfer contributions to the EI fund. In 2020, some 23% of wage workers reported that they were not covered in the EI system (Figure 3.1). The drivers of non-compliance are complex and can be difficult to substantiate. While employer and employee insurance premiums are comparatively low, their impact on labour costs can be felt by smaller firms that operate on small profit margins. Perhaps more importantly, the risks of non-compliance as perceived by these firms can be low, as detecting non-compliance is more difficult in micro-businesses. Evidence conclusively and consistently points to significant challenges in enforcing labour regulations.2 In part, this is due to limited enforcement resources. The number of workplaces per labour inspector stood at 770 in 2021 (OECD, 2023[7]). While this was down from 1 270 in 2016, following a boost in staff resources initiated over recent years, these ratios translate into very high enforcement burdens for staff. In addition, and despite evidence of limited success, successive governments have tended to prioritise positive compliance incentives/rewards for employers’ participation in a mandatory programme, over strict enforcement and tough penalties (see the discussion of the costly Duru-Nuri subsidies below).

Workers, too, may perceive incentives for EI membership as weak. In some circumstances, e.g. if their pay is low, they may collude with their employer to avoid paying insurance premiums in order to boost their net wage. Indeed, evasion of EI contributions is mainly a problem among small businesses, where wages tend to be low (Figure 3.1). Relatedly, workers may wish to avoid paying insurance premiums because relatively few of them have, traditionally, received benefits in the case of unemployment. In this sense, low coverage and low participation, can be mutually reinforcing. Reasons for evasion are not a problem only for EI, however. For instance, people who are enrolled in the health insurance as dependents have an incentive to avoid enrolling in any part of social insurance when taking up a job, in order to avoid paying health insurance premia.

In 2020, Korea and 11 other OECD countries operated lower-tier unemployment assistance programmes for those who are not, or no longer, entitled to first-tier insurance benefits (in addition to Australia and New Zealand, where means-tested unemployment assistance is the principal benefit for jobseekers, see https://taxben.oecd.org/policy-tables/TaxBEN-Policy-tables-2020.xlsx). A strong focus on re‑employment support in the Korean unemployment assistance has provided little continuous income support for claimants in the past, and recipient rates, while significant, were modest relative to the number of jobseekers. Korea recently began to strengthen its unemployment assistance programme with the introduction of NESP (see section 3), though it is too early to assess the impact of this reform.

Figure 4.3. Benefit access conditions vary widely across countries, 2020

Note: Panel A: For 40‑year‑old individuals with full-time open-ended contracts prior to employment loss. Norway, the United States: Minimum earnings requirements also apply. Italy: Plus at least 30 days in the 12 months prior to the start of the unemployment spell. Greece: Or 200 days in last two years. Canada: Assuming 40‑hour work week. the United Kingdom: Six months in any one of the past two years. Sweden: Plus minimum membership period in an unemployment insurance fund of 12 months. Ireland: Or 26 weekly contributions in each of previous two years. Must also have 104 weekly contributions in whole career. Austria: For first benefit claim: 12 months within two years (6.5 months within one year for under‑25s). Subsequent claims: 7 months within one year or 12 months within two years. Chile: Plus 12 months of contributions since the previous unemployment spell or withdrawal from the individual account, with last three contributions continuous and with same employer. Türkiye: Plus must have held the labour contract for the last 120 days before termination. Slovak Republic: Reference period is for temporary contracts, 12 months shorter for open-ended contracts.

Panel B: Scores from 1 (least strict, no requirement of involuntary unemployment) to 5 (most strict, complete loss of entitlements for those judged to be unemployed voluntarily without good cause). See (Immervoll and Knotz, 2018[39]) for content and scope of the strictness indicator.

Panel C: For a 40‑year‑old with a “long” employment record. Double slash means durations that are longer than 48 months, or unlimited. Canada: maximum benefit duration depends on regional unemployment rate and is shown for the national rate in December 2019. Chile: Unemployed individuals can draw unemployment insurance pay-outs provided there are sufficient assets in their individual savings account. Japan: up to 300 days of benefits for claimants who are deemed to be difficult to re‑employ. Sweden and in some other countries: additional unemployment support can be available for unemployed individuals participating in activation and employment support programmes. United States: benefit durations vary by State and unemployment rate. The 20‑week duration refers to Michigan.

Source: OECD Tax-Benefit Policy Databases, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN and https://oe.cd/ActivationStrictness.

4.1.3. Provisions for non-standard workers

Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, just over one in five non-standard workers in Korea reported receiving any income support following job loss. As noted above, this was lower than in any of the other 15 OECD countries that were included in the same study (Figure 1.1).

Across OECD countries, statutory access for non-standard workers typically varies by employment type. Temporary and part-time workers are commonly covered in the same way as permanent full-time employees in most countries, as long as they satisfy the same entitlement conditions that also apply to standard workers (applicable employment periods, earnings thresholds, etc.). Some countries operate exemptions for specific non-standard contractual arrangements, such as casual employment, seasonal work or hybrid categories. For instance, in the Slovak Republic, those with temporary employment contracts benefit from a longer reference period during which contribution requirements must be met. Access to unemployment support is also sometimes not conditional on job-search efforts or participation in ALMPs for jobseekers who have engaged in seasonal work (e.g. Greece, as well as Austria for those with an existing re‑employment agreement).

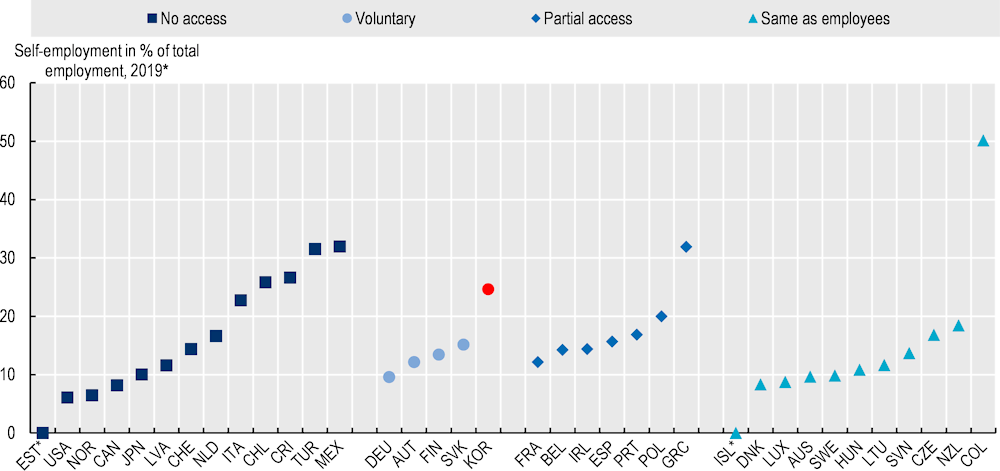

By contrast, statutory access for self-employed workers is very frequently restricted in contributory social protection systems. Indeed, provisions that were mostly set up with a steady employer-employee relationship in mind do not easily accommodate the self-employed (Box 4.1). When self-employed workers do have access to social protection, it is frequently on a voluntary basis, including in Korea (Box 4.2). Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, extensions of unemployment-benefit coverage for self-employed workers were legislated or discussed in a number of other OECD countries, including France, Ireland and Spain. In summer 2018, the French Parliament passed a law that provides for flat-rate unemployment benefits for jobseekers who become unemployed after a period of self-employment with earnings of at least 10 000 euro per year and subject to liquidation of the former business. Ireland introduced the Jobseeker’s Benefit for the Self-Employed in 2019. The programme provides support also for those with low earnings in past self-employment. Benefit durations are somewhat shorter than for dependent workers, and entitlement requires longer contribution records. Spain made a previously voluntary unemployment insurance scheme for self-employed workers compulsory from early 2019.

Figure 4.4 summarises the situation at the onset of the crisis. 11 of 36 countries offered self-employed workers similar unemployment protection provisions as for dependent employees. Another seven offered partial access, i.e. with lower amounts and/or more stringent entitlement criteria than for dependent employees. In 5 countries, the self-employed had the option to join a voluntary unemployment insurance scheme, but membership rates were often low – under 1% of all self-employed workers in Austria and Korea, 3% in the Slovak Republic and 10‑15% in Finland (European Commission, 2022[40]; Park, 2020[41]). The remaining 13 countries did not offer any unemployment insurance benefits for self-employed workers.

Self-employed workers have been particularly vulnerable to income losses during the COVID‑19 crisis and they often did not benefit from headline support measures such as job retention schemes. Incomplete coverage in unemployment support programmes therefore left a significant number of workers exposed as the crisis hit. By contrast, countries where (some) self-employed workers already had access to unemployment benefits were able to quickly shore up support using existing structures: in Denmark, for example, self-employed workers could retrospectively join an Unemployment Insurance Fund by paying a year’s contributions if they were affected by containment measures, while Ireland suspended minimum contribution requirements.

A number of countries without pre‑existing systems for assessing past earnings and entitlements sought to create such structures quickly. Austria, Norway, Switzerland and the United States, among other countries, introduced new emergency benefits for self-employed workers that were tied to previous earnings or crisis-related losses. But in the absence of established administrative procedures, the accurate assessment of previous income (especially the fluctuating income of the self-employed) takes time. Some countries relied on self-reported earnings losses, especially at the beginning of the crisis (e.g. Austria), accepting lower targeting accuracy. Others circumvented time‑consuming earnings-assessments by providing flat rate benefits (e.g. Canada, France, and Italy). Chile, Germany, the Netherlands, and to a lesser extent Mexico extended their existing minimum income programmes to make them more accessible to self-employed workers (Denk and Königs, 2022[42]).

In light of this experience, several countries are currently extending income protection for self-employed workers. Germany is considering extending access to voluntary unemployment benefits for self-employed workers without an insurance record as dependent employees. In France, there are plans to extend unemployment support to those with unviable businesses (currently, only those whose business has been closed by court order are eligible). Italy introduced a new unemployment benefit for the previously uncovered group of para-subordinate professionals (unlicensed professionals, such as web designers, who are legally self-employed but economically dependent on one or very few clients). The new programme is initially time‑limited, lasting from 2021 to 2023. It insures against significant reductions in income (at least 50% over the last three years) and cushions half of this loss. This type of income insurance can be especially well-aligned with the circumstances of freelancers relying on a small number of clients.

Figure 4.4. Statutory access for self-employed workers was limited before the pandemic

Note: Gaps between dependent employees (full-time open-ended contract) and self-employed workers. If there are several legal forms of self-employment in a country, the graph refers to the most prevalent form of self-employment, excluding farming and liberal professions. For Italy, the graph refers to craftspeople, shopkeepers/traders and farmers, and not to para-subordinate workers, who are covered by a separate scheme. For Portugal, the graph refers to dependent self-employed workers. For Belgium, “partial access” refers to the droit passerelle, a separate non-contribution-based programme for self-employed workers. For Germany, “voluntary access” refers to the unemployment insurance benefit Arbeitslosengeld I, not to the needs-based unemployment assistance benefit Arbeitslosengeld II that self-employed workers may also claim. In the Czech Republic, self-employed workers are statutorily insured at half of their taxable income but may choose a higher contribution base. Partial access: self-employed workers are insured through a different scheme, receive lower benefit amounts and/or have more stringent entitlement criteria than dependent employees. “No access”: compulsory for dependent employees but the self-employed are included.

* No data on the incidence of self-employment in Estonia and Iceland. Data on self-employment incidence refers to 2018 for Norway and 2015 for the Slovak Republic.

Source: Adapted and updated from (OECD, 2019[43]), using OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis supplemented with information from the OECD Tax-Benefit Database (http://oe.cd/TaxBEN), MISSOC (2020[44]), Spasova et al. (2017[45]) and (ESPN, 2021[46]) for European countries, Government of Canada (2022[47]) on Canada, and OECD (2023[8]; forthcoming[48]) on Greece and the United States. Incidence of self-employment: OECD (2022[49]), “Labour Force Statistics: Summary tables”.

Box 4.1. Making social insurance available for self-employed workers: Key challenges

Double contribution issue: Who should be liable for employer contributions in the absence of an employer? In practice, total formal contribution burdens are frequently lower for the self-employed than for dependent employees. Requiring the self-employed to pay the equivalent of both employer and employee contributions brings formal burdens in line with dependent employees. But effective burdens may be higher for the self-employed, especially those with lower earnings, because minimum wages typically do not apply to them or because they may lack the bargaining power to shift any contribution-related costs onto their clients by charging higher prices (OECD, 2018[50]).

Fluctuating earnings (and margins for avoiding contribution liabilities): The self-employed, along with some atypical employees such as on-call workers or those with zero-hours contracts, are often paid at irregular intervals, either because of time lags between work and payment, or because demand for their services is erratic (ISSA, 2012[51]). This complicates the calculation of contributions (as well as the assessment of entitlements). In particular, self-employed workers may be able to avoid or lower contributions by optimising their contribution base, e.g. through timing their work or earnings.

Moral hazard: Demand or price fluctuations affecting self-employed workers are difficult to distinguish from voluntary idleness and this complicates the provision of unemployment insurance in particular. For instance, there is no employer to confirm a layoff and efforts to re‑establish a business operation are more difficult to monitor than the search for dependent employment. In addition, earnings levels may fall more readily for self-employed in response to market developments, e.g. because there are no minimum wages and downward wage rigidity does not apply to them. If entitled to unemployment benefits, those with poor earnings prospects may therefore have relatively strong financial incentives to wind down the business and claim unemployment benefits. Where self-employed individuals can claim benefits, they typically need to meet relatively stringent requirements to demonstrate that their business is no longer operational. For instance, claimants of unemployment benefits in Sweden are required to wind down or “freeze” their business and cannot claim benefits again for several years if they once again take up their previous self-employment activity after a benefit spell.

Source: (OECD, 2019[43]), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/bfb2fb55-en

Box 4.2. Voluntary insurance for self-employed: Rationale, problems and country experiences

The provision of income insurance on a voluntary basis partly reflects specific risk patterns and fairness considerations: as entrepreneurs seek to make a profit in return for taking on business risks, they can be less risk averse, and therefore may not “require” insurance to the same extent as employees. However, the same rationale could be invoked more broadly, e.g. for employees who face lower risks or are less risk averse than others. Ultimately, strong reliance on selective or voluntary social protection membership widens the scope for gaming social risk-pooling systems, resulting in insurance becoming inefficiently narrow. With “good risks” able to opt out (or not opting in), actuarially neutral insurance premia will be higher (and possibly unaffordable) for those who need it most (the “bad risks”). Indeed, low-earning individuals may underinsure even when social insurance provisions offer attractive cost-to-risk ratios, see (Codagnone et al., 2018[52]).

In practice, membership in non-mandatory insurance schemes is often organised on an opt-in basis. But there are also examples of auto‑enrolment, e.g. voluntary pension insurance for marginal employees (mini jobs) in Germany since 2013. In all cases, voluntary membership risks adverse selection of members: where insurance premiums are uniform, those with the highest risk have the biggest incentive to join. If the scheme is entirely self-funded, this can lead to a vicious circle of contribution hikes and low-risk members leaving; if the scheme is publicly subsidised, costs can increase. An example of this mechanism is the Canadian Special Benefits for Self-employed Workers scheme, providing maternity and parental, sickness and care benefits since 2010. Self-employed workers pay the same contribution as standard employees but without the employer part that would be due for dependent employees. Over three‑quarters of claims were initially for maternity and parental benefits, two‑thirds of opt-ins were women (who represent only 43% of all self-employed workers), and two‑thirds were between the ages of 25 and 44 (compared to just one‑third of all self-employed). As opt-ins had significantly lower incomes than other self-employed, contributions covered less than one‑third of benefit payments.

In 2007‑08, reforms of the voluntary unemployment insurance in Sweden linked employee contributions to unemployment risk and raised average premia by 300%. Membership in the Unemployment Insurance Funds dropped by around 10 percentage points in the following years. Older workers, who have the lowest unemployment risk of all age groups, were particularly likely to exit the system, as were those under the age of 25, who typically have low earnings and short unemployment durations.

Self-employed workers in Austria can opt into a short-term sickness benefit programme, and about 8% of eligible self-employed workers do. In 2016, close to half of those who were covered received a benefit, and the average benefit duration was nearly twice the average sick leave duration for dependent employees, highlighting moral hazard risks. In response to the resulting deficits in the programme, the minimum benefit was cut significantly in 2017.

As EI in Korea, some schemes offer choice in terms of contribution levels. For example, self-employed in Latvia and Spain can choose their contributions to unemployment and occupational injury insurance. Similar to selectivity mechanisms in insurance provisions with voluntary membership, higher-risk individuals can have an incentive to choose higher contributions in order to maximise their entitlements. Yet, if the system is explicitly redistributive (offering higher replacement rates for low incomes/contributions), there are incentives for keeping contributions low. Indeed, approximately nine out of ten contributors to the schemes in Latvia and Spain chose to pay the minimum.

Source: (OECD, 2019[43]), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, https://doi.org/10.1787/bfb2fb55-en

4.2. Benefit levels

Prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, support levels reported by low-income benefit recipients after recent employment loss were the lowest among 16 OECD countries studied in (Immervoll et al., 2022[6]). Estimates reported in Figure 1.1 above point to values of EI and other available benefits ranging between 20% of median household income for standard workers, and under 10% for non-standard workers.

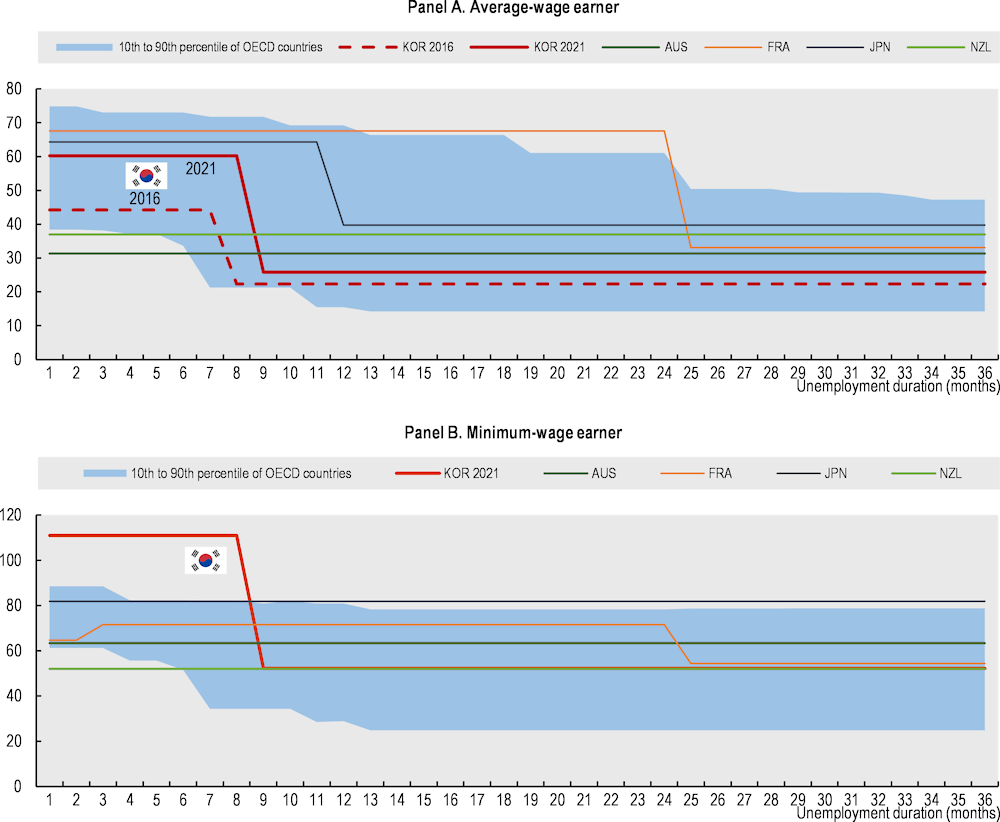

In fact, for average‑wage earners with a long employment history, initial replacement rates after job loss are broadly in line with those in other OECD countries with an unemployment insurance, and they have been boosted as part of a reform in 2019 (Figure 4.5, Panel A). Benefit duration has also been extended, but the income drop (after close to 9 months of unemployment) comes earlier than in comparator countries. The drop is also much larger, even assuming full entitlement to means-tested support (such as BLSS livelihood and housing benefits). Replacement rates for longer-term unemployed in Korea are lower than in Australia and New Zealand, where no unemployment insurance exists, and where all income support for jobseekers takes the form of means-tested benefits.

By contrast, initial replacement rates for low-wage earners are exceptionally high. For minimum-wage workers, they can be above 100% (Figure 4.5, Panel B). Even though benefit durations are comparatively short, such high replacement rates can translate into significant financial disincentives to work, notably for workers who have multiple options for when or how much to work (OECD, 2020[53]). The reason for these substantial disincentives is the unusually high benefit floor described in section 33. The floor can exceed the net income of low-wage earners, a group whose employment decisions tend to be particularly responsive to financial incentives (Immervoll, 2012[54]). The benefit floor’s detrimental impact on work incentives for this group is much stronger than the effects of policies that seek to make work pay, such as the earned income tax credit, and Korea’s comparatively low income tax and social contribution burdens.

Figure 4.5. Replacement rates are too high for low-wage earners, but low for longer jobless spells

Note: Policy rules as of January 2021, as reported by responsible ministries in OECD member countries. The shaded area illustrates the range of replacement rates across most OECD countries. Net replacement rates express net out-of-work income as a percentage of net income while in work. Calculations are for a single‑person household (40‑year‑old, “long” and uninterrupted employment history, involuntary job loss). They account for income tax, social contributions, and the full range of benefits that are available while in work (e.g. tax credits) and unemployed (unemployment benefits, minimum-income benefits, cash housing support). Panel B: Minimum-wage earners in Korea are assumed to earn KRW 8 720 per hour, and to work 209 hours a month. Their EI entitlements were KR 60 120 (the daily EI benefit floor), paid 7 days per week.

Source: OECD tax-benefit models, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

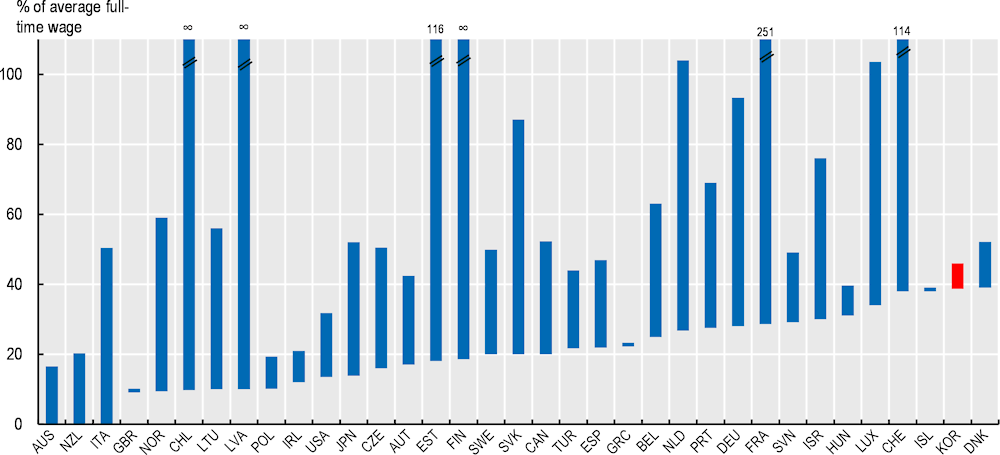

4.2.1. There is no longer a meaningful link between benefit entitlements and past earnings

Even though EI was designed as an insurance benefit, it no longer provides earnings insurance as commonly conceived. This is shown in Figure 4.6, which compares statutory benefit floors and ceilings and, this the interval in which earnings-related benefits operate in practice. In countries where the main unemployment benefit is means-tested (Australia and New Zealand), the ceiling refers to the benefit available for someone without any other resources. In Korea, concerns about negative work incentives, combined with a tight financial situation of the Employment Insurance Fund, have prevented or slowed regular adjustments of benefit ceilings over time. As ceilings did not keep up with wage growth, benefit entitlements for workers with moderate to higher earnings levels kept falling behind. Their low prospective entitlements, in turn, may have contributed to a reluctance of workers above a certain income (and their employers) to actively seek EI membership. Meanwhile, the benefit floor has been effectively linked to the minimum wage. As minimum pay was boosted over time, this pushed the benefit floor much higher than in other OECD countries with earnings-related benefits. In international comparison, the combination of a low benefit ceiling and the absence of a ceiling on contributions is unusual. Effectively, EI still works like an insurance benefit on the financing side, while benefit entitlements are almost flat rate. Rather than providing a degree of earnings insurance for everybody, the current policy configuration therefore mainly redistributes from higher-earning to lower-earning EI members.

Figure 4.6. Korea’s benefit floor is very high, very close to the maximum benefit amount

Note: Average full-time wage refers to the economy-wide average (not to the average for the benefit claimant). Benefit amounts are relevant for jobseekers who meet all applicable eligibility, entitlement and behavioural conditions; are aged 40; and are single and without dependents. Floor amounts shown are whichever is highest between: i) the explicit minimum benefit amount, and ii) the de facto minimum benefit amount a jobseeker would receive after full-time employment paying the applicable minimum wage.

Source: OECD tax-benefit models and policy database, http://oe.cd/TaxBEN

4.3. Employment incentives and support

Weak work incentives due to overly generous out-of-work benefits are rarely the only, or even the main, employment barrier for jobseekers. Korea is no exception to this pattern (Fernandez et al., 2020[13]). Nevertheless, a labour market as fluid as Korea’s – with comparatively short employment durations, less binding constraints on contractual arrangements and working conditions than in most of the OECD, and various options for when and how long to work – creates ample opportunities for acting on positive and negative incentives.

4.3.1. Labour markets in transition: A need to broaden the scope of activation policies?

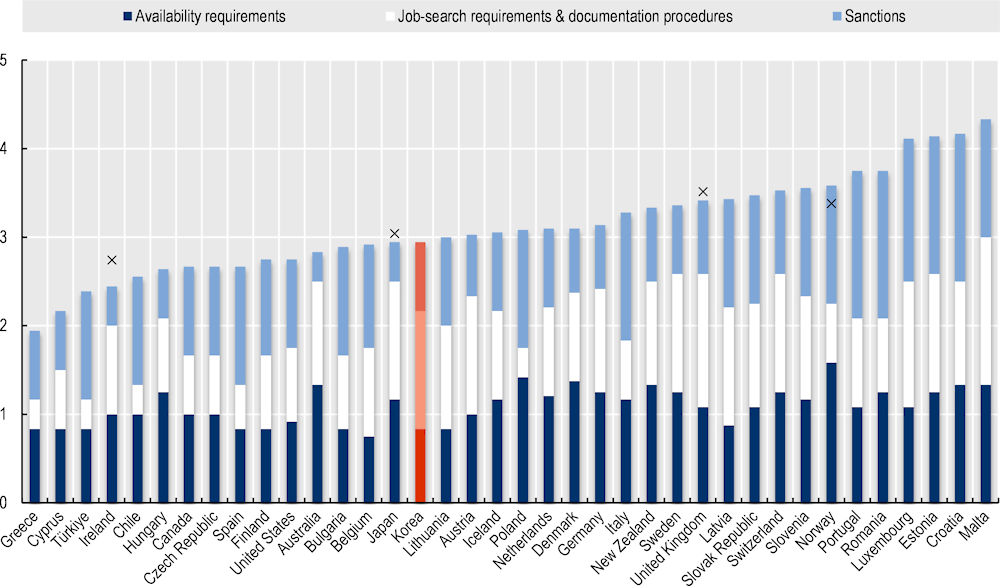

Korea scores close to the OECD average in terms of the overall strictness of activation requirements (Figure 4.7). These activity-related eligibility criteria regulate the requirements that claimants need to meet in order to continue receiving a benefit, they include conditions regarding the availability for employment and job-search activities, as well as benefit sanctions in case conditions are not met. Requirements regarding claimants’ availability for employment (the types of work that benefit claimants need to accept) are relatively lenient in Korea. This is driven by weak demands on occupational mobility, while geographical mobility requirements are in fact strict.3 Legal provisions regarding job-search requirements and related monitoring procedures are more demanding than in many other countries. Sanctions for non-compliance with activity requirements are comparatively lenient overall, reflecting mild sanctions for those refusing job offers or participation in ALMPs. However, as noted earlier in this section, Korea imposes significant sanctions (complete benefit loss) on benefit claimants who are judged to be voluntarily unemployed without good cause.

Figure 4.7. Strictness of activation requirements

Note: Preliminary results, responses from some countries missing or incomplete. Where overall strictness scores changed relative to 2020, crosses indicate previous (2020) values.

Source: (Lee, Immervoll and Knotz, forthcoming[55]), “Activation requirements after COVID: How demanding?”, https://oe.cd/ActivationStrictness.

Changing work patterns and new forms of employment raise novel questions about the scope and ambition of activation policies. For instance, compared with out-of-work individuals with past standard employment, jobseekers with a history of self-employment can be less likely to rely on PES for their job search, e.g. if a lack of benefit entitlements means that there is no immediate financial incentive for regular interaction with the PES. Limited engagement with the PES, for whatever reason, can become a growing concern when independent forms of work increasingly become substitutes for dependent employment.

Extending benefits to additional groups can help to ensure that new forms of work are not left outside the scope of income and employment support. At the same time, there can be a need to review whether benefit reforms that are intended to tackle coverage gaps also create a need to rebalance the demanding and supporting elements of existing rights-and-responsibilities frameworks. An emergence of alternative working arrangements, with additional scope for arranging work or earnings patterns in a way that is compatible with benefit receipt, may call for additional efforts to formulate and enforce clear and reasonable responsibilities for benefit recipients. Likewise, ensuring adherence to job-search responsibilities, and to requirements to actively participate in re‑employment measures, may be a necessary counterweight to any extensions of benefit rights to new groups of jobseekers. Certain elements of Korea’s recent reforms suggest that policy makers generally share the view that adding new groups to the scope of EI necessitates a reconsideration of activation provisions. Examples are the longer benefit waiting periods that apply for artists and dependent self-employed who leave their jobs voluntarily (4 weeks and 2 to 4 weeks, respectively). Nevertheless, a comprehensive review of the full range of activity requirements, and their suitability for different groups of jobseekers, should accompany reforms of income support entitlements.

New or growing forms of non-standard work may also require weighing the intended role and objectives of publicly provided labour market intermediation and employment services. A key issue is to what extent PES should actively connect people to very short-term work engagements (“gigs”), casual work (e.g. on-call employment or “zero hours” contracts) or independent forms of employment. Although the PES’ intermediation role can be partly redundant for platform work that is readily accessible online, some PES today already use web scraping technology to consolidate vacancies from a number (sometimes hundreds) of vacancy repositories. For instance, in the Netherlands, more than one‑third of vacancies that are listed on the PES job portal are sourced from other web resources using such technology. Similarly, the Austrian AlleJobs (http://www.ams.at/allejobs) platform (and a smartphone app) can be searched by everybody (whether or not registered with PES), and seeks to combine all job vacancies, advertised at PES or otherwise, in a single place.

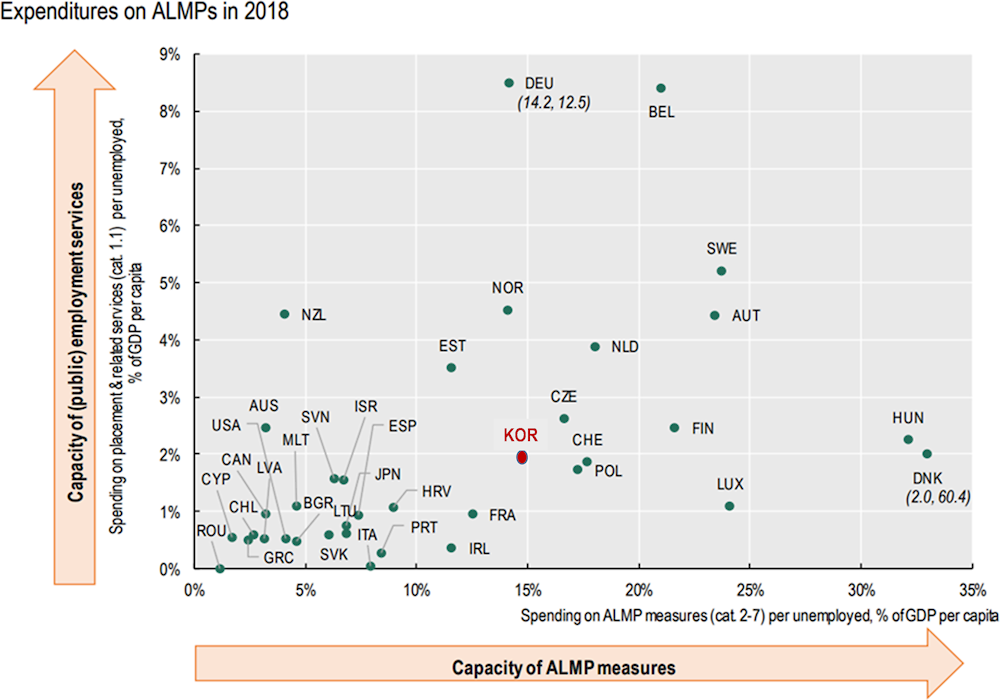

Figure 4.8. Capacity of active labour market policy

Source: (Lauringson and Lüske, 2021[56]), “Institutional set-up of active labour market policy provision in OECD and EU countries: Organisational set-up, regulation and capacity”, https://doi.org/10.1787/9f2cbaa5-en.

Weak financial work incentives for low-paid workers, concerns in the policy debate about the number of repeat benefit claims, and the government’s welcome commitment to tackling blind spots in the EI and NESP programmes, highlight the importance of well-balanced responsibilities for both benefit claimants and employment services. They also underline the need for reviewing resources for active labour market policies, as well as activation approaches, when the scope of unemployment support broadens. For instance, demanding proof of independent job search could be particularly effective when the public employment service (PES) has limited capacity for providing job-search assistance. Relatedly, very strict requirements may be ineffective when monitoring compliance is difficult. Deviations between formal rules and their actual enforcement in day-to-day practice are more likely when resource constraints at the PES or benefit office preclude an effective follow-up and credible monitoring of claimants’ compliance with relevant obligations and responsibilities (Grubb, 2000[57]). These considerations are relevant in the context of Korea’s spending on PES and active employment programmes (ALMPs) per unemployed person (Figure 4.8). Korea’s past experience with the rapid increase in the capacity of employment services also highlights the importance of quality control, notably in a context of contracts with providers of employment services (OECD, 2018[2]).

4.4. Financing

As Korea sought to expand EI coverage in the past, financing needs have risen, resulting in increasing contribution rates for workers and employers (see section 3). At 0.9% and 1.15‑1.75% of wages, respectively, worker and employer contribution burdens for EI have remained comparatively modest, however. Indeed, total contribution burdens for unemployment insurance are notably lower than in most other advanced economies, where they are typically in the order of 4‑8%, see http://oe.cd/TaxBEN and (ILO, 2019[58]). Yet, future expansions will translate into additional resource needs. Any measures to provide more meaningful income security for workers with average wages, by re‑establishing a link between entitlements and past earnings, can also be expected to drive up overall spending. The fiscal context for working-age support is potentially challenging, with fiscal space squeezed from different directions. Labour incomes are the main funding base of most social protection systems, and this base has weakened overall. Labour’s share in national income has declined significantly over the past two decades in many OECD countries, with one of the largest drops in Korea, at more than 10 percentage points of GDP (OECD, 2018[59]).

On the spending side, population ageing puts growing pressures on pension, health and long-term care systems, which absorb increasing shares of available social protection budgets across OECD countries. Indeed, expenditures on old age and survivor benefits over the past 25‑30 years have grown substantially not only in total but, in spite of pension reforms, also on a per capita basis. Averaged across OECD countries with longer series of social spending, the spending on old age and survivor benefits per individual aged 65 and older has grown from 22% of GDP per capita in 1990, to 32% in 2000 and 38% in 2013. In Korea, per person spending levels for old age income protection were lower but the increase was very steep, from 4% of GDP per capita in 2000, to 15% in 2014.4

Indeed, the financial soundness of the EIS has deteriorated following the employment shock in the wake of the pandemic, but also because of additional spending commitments resulting from recent EI reforms. Prior to the announcement of financial consolidation measures in 2021, the EI reserve fund had been expected to become depleted by 2023 and recovering it to sustainable levels has rightly been a prominent topic of discussion in Korea.

The government announced the “Employment Insurance Financial Rehabilitation Plan” at the end of 2021. In response, the government is pursuing policies to increase fund revenue and restructure expenditures. For instance, an additional transfer will be undertaken from the general budget, to cover expenses related to maternity protection benefits, and the employment insurance premium rate will be raised by 0.2 percentage points. In addition, the government plan includes considerations for moderating expenditures through strengthening benefit sanctions, extending benefit waiting periods, and reducing benefits for repeat claims. The fiscal balance of the EI fund positive in 2022 and is currently projected to remain in surplus in 2023.

Notes

← 1. According to OECD calculations based on Ministry of Employment and Labour data, NESP unemployment assistance in 2021 and 2022 accounted for about 14‑15% of all unemployment benefit recipients in any given month on average (NESP Type‑I support and EI). Comparable data on the number of unemployment-assistance recipients were not available for years 2020 or earlier.

← 2. For instance, about half the hours that should attract overtime premia were left unpaid in 2016, and about 10% of employees in 2016‑17 were paid below the minimum wage (Choi, 2018[61]). Overall, around 40% of all wage workers in Korea were found to engage in some form of informal work, defined as work that is not fully covered by minimum wage regulation, labour standards and social insurance (Lee, 2017[21]).

← 3. Strict requirements regarding geographical mobility are accompanied by support payments. A “Wide‑area Job-seeking Allowance” is paid to those seeking work at a distance of more than 50km from their residence, while a “Moving Allowance” is available for jobseekers who relocate for work or training.

← 4. Increasing per capita spending on pensions is in line with growing employment rates, especially among women, and the resulting growth in the number of people with significant pension entitlements. The average spending figures quoted in the text for OECD countries are for: Austria, Australia, Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States.