After a decade of strong export-led growth, decreasing unemployment and fiscal surpluses, the pandemic and the energy crisis have revealed structural vulnerabilities and emphasised the need for accelerating the green and digital transitions. At the same time, rapid population ageing increases public spending pressures and exacerbates skilled labour shortages. Reducing labour taxes, particularly for low-income and second earners, facilitating skilled migration, and improving adult education and training, particularly for low-skilled and older workers, is key to address skilled labour shortages. Education quality needs to improve, with a particular focus on children from disadvantaged households, to better equip younger generations with the skills needed for the green and digital transition. Fostering business dynamism, investment and innovation by lowering market entry barriers, strengthening competition, and improving access to finance for start-ups is crucial to raise productivity growth. This requires, in particular, the modernisation of the public administration to lower the administrative burden and improve the quality of public services. Addressing the existing infrastructure backlog and investment needs for the green and digital transitions will require significant public resources. To tackle these challenges while safeguarding fiscal sustainability, it is crucial to reduce tax expenditures, strengthen tax enforcement, increase public sector spending efficiency and better prioritise spending.

OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 2023

1. Key policy insights

Abstract

The energy crisis emphasises the need for accelerating the green transition and structural reforms

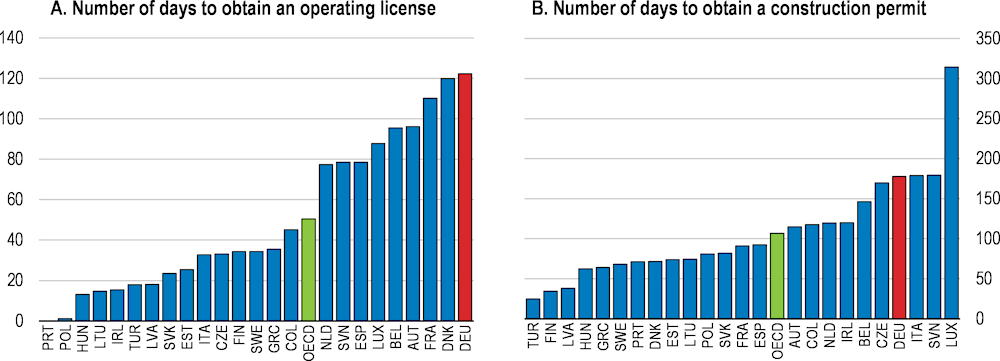

After a decade of strong export-led growth, decreasing unemployment and fiscal surpluses, a strong recovery from the pandemic was under way when Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine started. A spike in energy prices due to the war has fuelled inflation and reduced the purchasing power of households (Figure 1.1). It also weighs on the competitiveness of firms, particularly energy-intensive ones, and increases uncertainty related to energy security, as Germany is highly dependent on energy imports. The government has acted swiftly to secure energy supply and support households and firms facing record high energy prices, but this comes at a significant fiscal cost, compounded by rising defence spending. Energy prices will likely stay high for longer, deteriorating Germany’s terms of trade and weighing on potential growth.

Figure 1.1. Energy prices remain high

Gas and electricity prices (January 2020 = 100)

1. Producer price index of natural gas when supplied to industry.

2. Producer price index of electricity when delivered to special contract customers.

Source: Federal Statistical Office.

Accelerating the green transition holds great potential to strengthen energy security, encourage the development of new business models and support growth, but this will have costs and require more investment and support for workers that need to change jobs (see Chapter 2). Germany has made great progress in greening its economy, with the share of renewables in total electricity production reaching 41% in 2021, up from 8% in 2000. However, reducing greenhouse gas emissions to net zero in 2045 will require more ambitious mitigation policies.

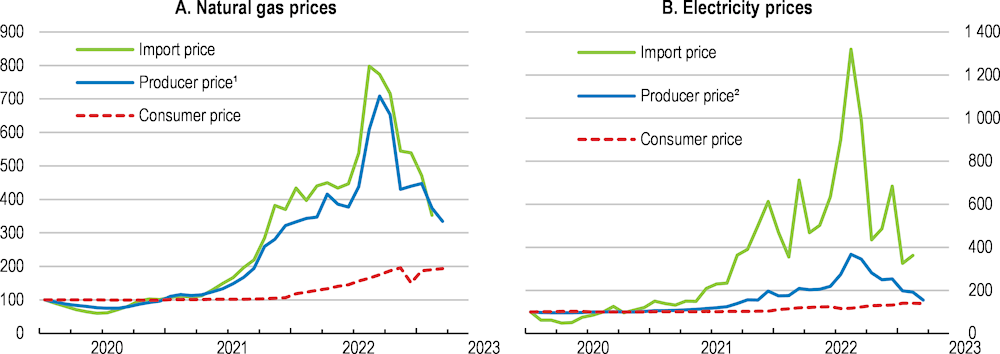

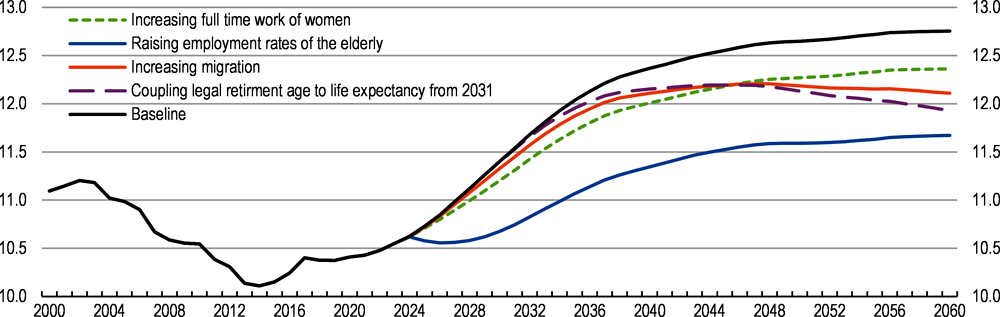

At the same time, rapid population ageing puts pressure on public pension, health and long-term care spending (Figure 1.2). It exacerbates skilled labour shortages lowering potential growth and the comparative advantage of many manufacturing sectors, in addition to energy security concerns (Bickmann, Grundke and Smith, forthcoming[1]). According to the United Nations, the working age population is projected to shrink by more than 8% by 2030, which is far more than in the average OECD country (Figure 1.2). Labour shortages will not only become a severe bottleneck for increasing investments in green, digital and housing infrastructure, but will also affect public administration. Labour shortages already pose a significant challenge to the provision of high-quality services in education, health and long-term care (KOFA, 2022[2]).

Figure 1.2. Rapid population ageing will exacerbate labour shortages and increase fiscal pressure

Note: The graphs show baseline projections for Germany based on latest policy announcements and following the methodology of (Guillemette and Turner, 2021[3]).

Source: Panel A: United Nations (2022), World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision, Online Edition. Panel B: OECD Long Term Model.

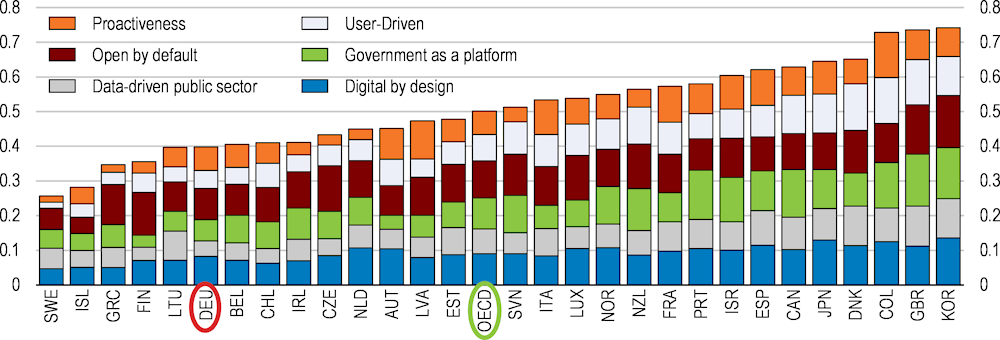

Although Germany managed the initial stages of the COVID-19 crisis well, consecutive waves of the pandemic have underscored the lack of digitalisation in the public sector as well as significant coordination problems across levels of government (Nationaler Normenkontrollrat, 2021[4]). This is hampering the capacity of the state to deliver high-quality public services and risks to hold back the green transition. Complex and lengthy planning and approval procedures for infrastructure investments are a major bottleneck for the expansion of renewable energy supply and other crucial infrastructure (as discussed in the previous OECD Economic Survey of Germany). Accelerating the digitalisation of the public administration will require further investments in digital infrastructure and the skills of public employees as well as better coordination and harmonisation of administrative procedures across levels of government (BMWK, 2021[5]).

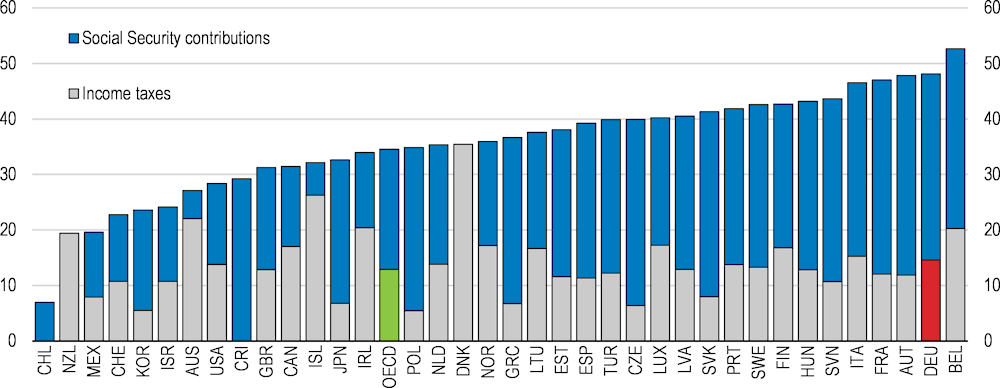

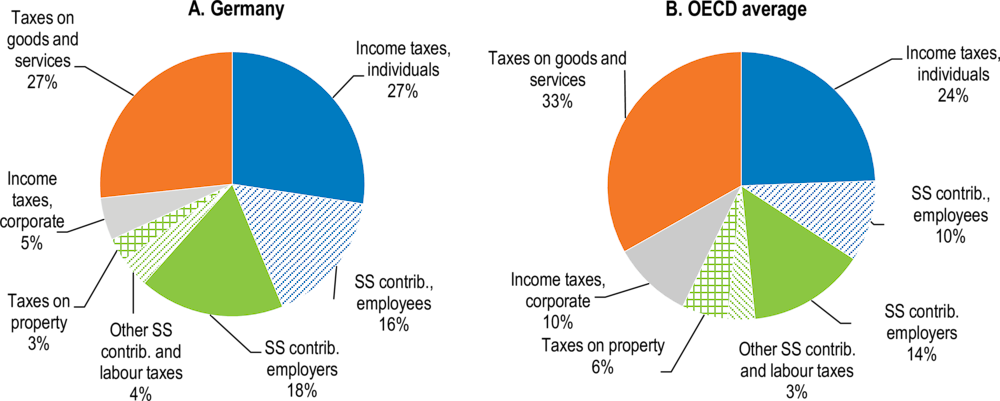

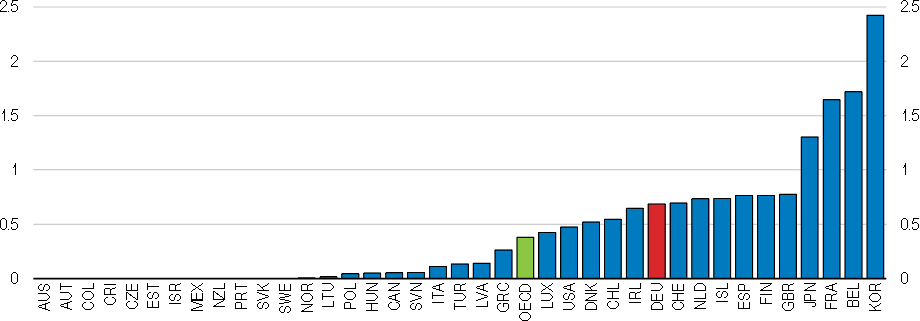

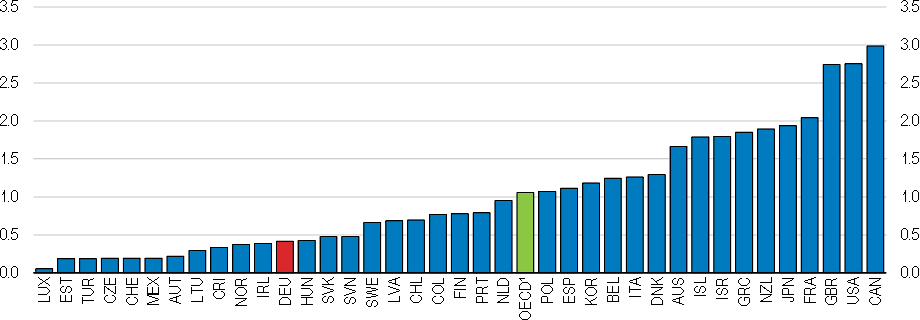

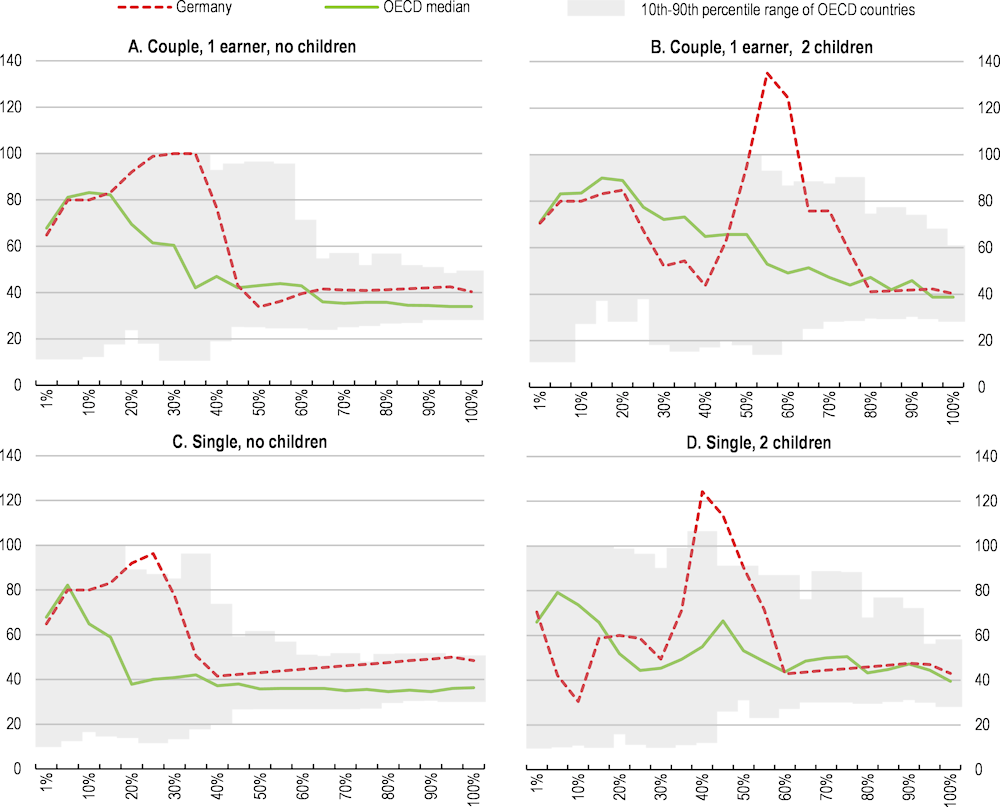

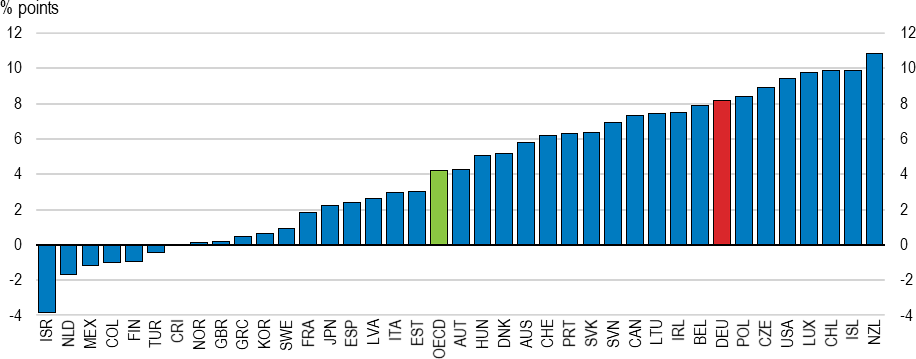

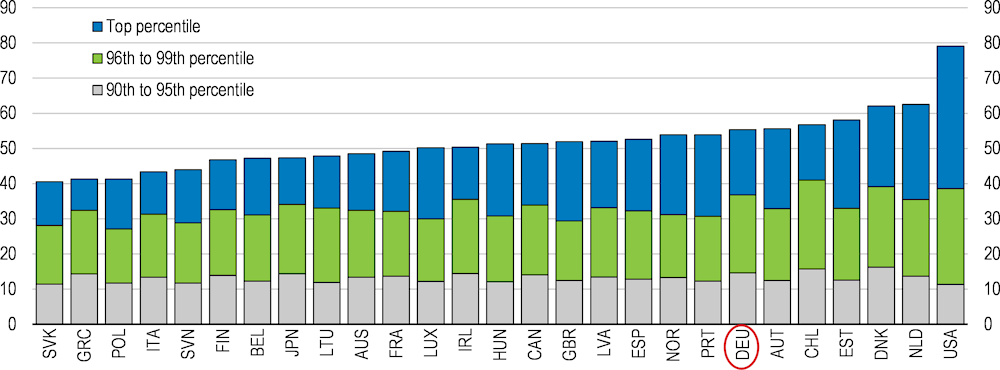

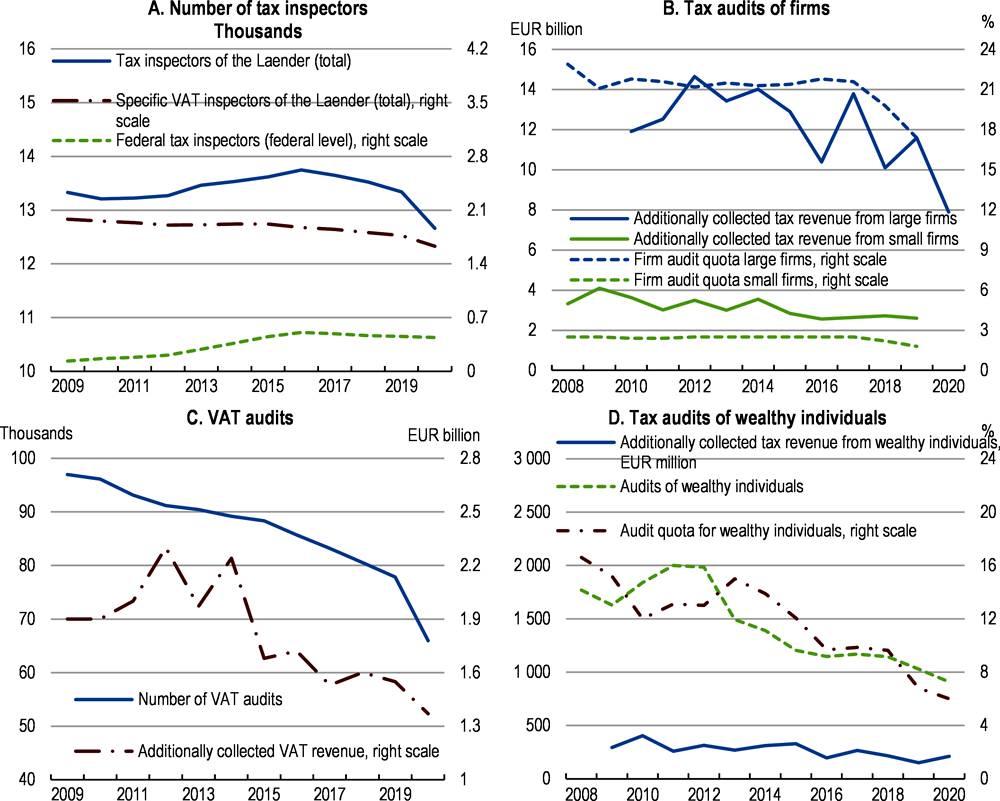

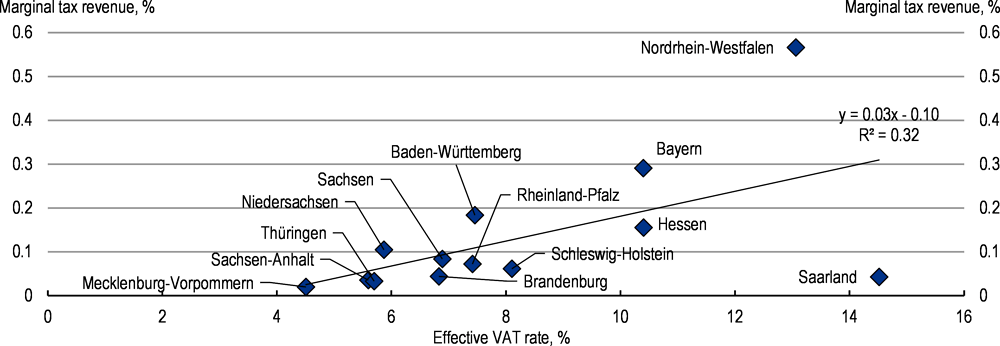

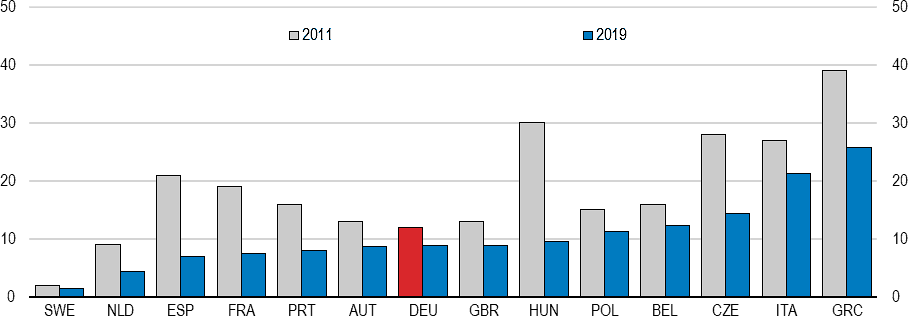

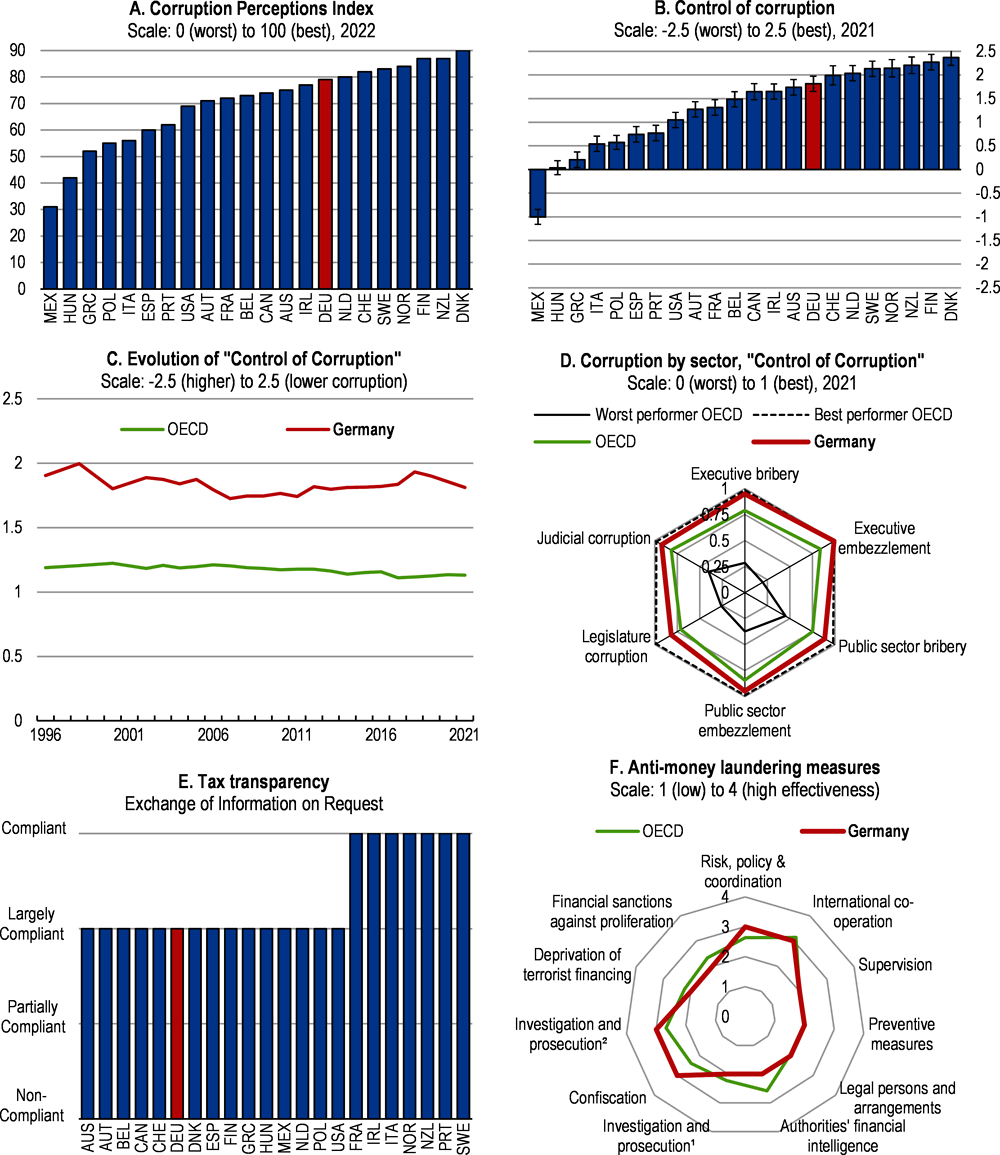

Managing the green and digital transformation and addressing the infrastructure backlog will require significant public resources. The average tax burden including social security contributions stood at 39.5% of GDP in 2021, which is around five percentage points higher than the OECD average, but reaching net-zero would significantly reduce revenue from environmental taxes, which amounted to about 2.6% of GDP in 2022 (OECD, 2022[6]; Baer et al., 2023[7]). Moreover, raising labour supply to address skilled labour shortages will require lowering labour taxes, particularly for low-income and second earners. As statutory tax rates are already high in international comparison, the necessary fiscal space should be created by reducing tax expenditures, strengthening tax enforcement, increasing public sector spending efficiency and better prioritising spending. Subsidies and tax expenditures are high and, in many cases, introduce distortions that counteract the key policy objective of greening the economy (see chapter 2). Simplifying the tax system and closing regressive tax exemptions, for example concerning capital gains and inheritance taxes, and strengthening tax enforcement could raise a significant amount of revenue and reduce inequality. It would also lower administrative burden and level the playing field, contributing to a more efficient allocation of capital and fostering entrepreneurship and innovation. Strengthening impact evaluation of policy programmes and making broader use of spending reviews have the potential to significantly raise public spending efficiency and help to better prioritise spending.

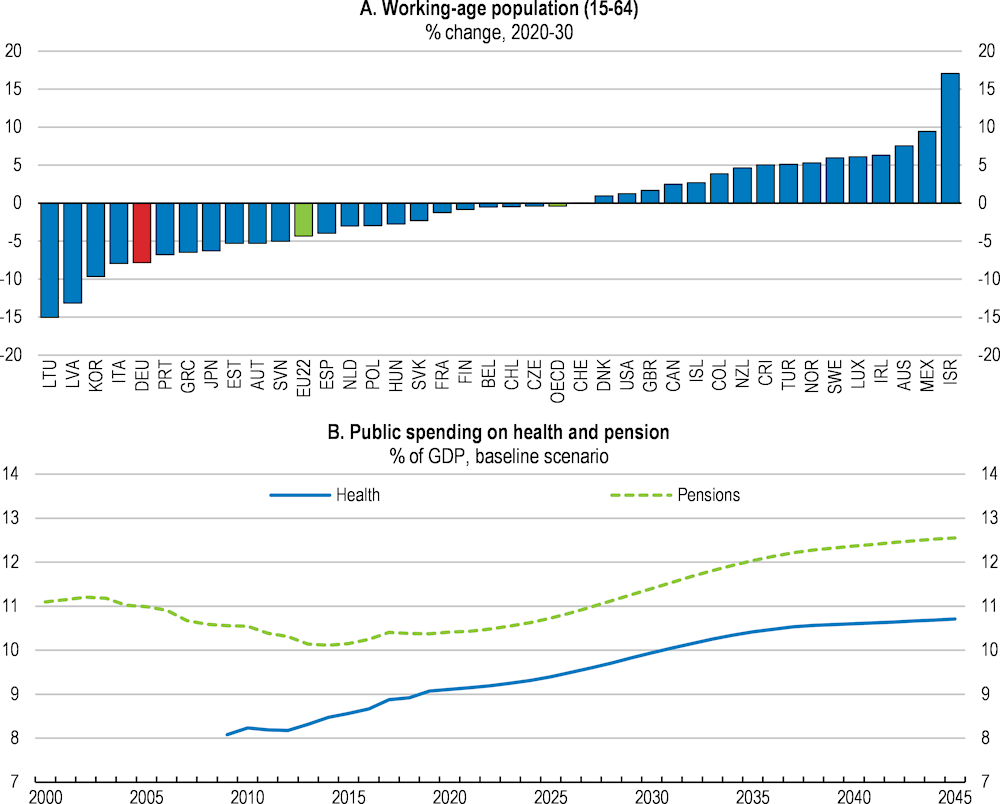

Structural reforms are needed to raise productivity and sustain growth despite a declining workforce and to reduce fiscal pressure from rapid population ageing (Figure 1.3, Table 1.1). Improving work incentives in the tax and transfer system, adult education and training programmes and working conditions is key to raise the labour supply of women, low-skilled workers and the elderly. This should be combined with facilitating skilled labour migration and better preparing younger generations with the skills needed for the green and digital transitions, with a particular focus on children from disadvantaged households. It is also crucial to revive business dynamism, investment and innovation. This requires more public investment in infrastructure and research and development (R&D), but also lowering market entry and growth barriers for young and innovative firms. This entails reducing the administrative burden, strengthening the competition framework, raising transparency on political lobbying from established incumbent firms, and improving access to finance. Creating a more favourable environment for start-ups will contribute to developing and adopting the disruptive technologies necessary for the green transition and maintaining Germany’s export strength in the future (see the previous OECD Economic Survey of Germany).

Against this background, the main messages of the Survey are:

Create fiscal space for the green and digital transitions by reducing tax expenditures, strengthening tax enforcement, increasing public sector spending efficiency and better prioritising spending. Accelerate the modernisation of the public administration to improve public governance.

Continue to address the economic consequences of ageing by implementing a comprehensive policy package to support the labour market integration of women, elderly and low-skilled workers, facilitate skilled labour migration, and expand adult learning opportunities. Raise education quality, particularly for children from disadvantaged households, and improve access to early-childhood education.

Reduce emissions cost-effectively by aligning the emission cap in the national trading system with the targets, phasing out environmentally harmful subsidies and tax expenditures, and expanding support for green R&D, focusing on insurance mechanisms and unmatured technologies. Use carbon tax revenues to support vulnerable households and expand the scope of active labour market and adult learning policies to facilitate structural change and reduce inequalities.

Figure 1.3. Structural reforms are needed to preserve growth and reduce fiscal pressures

Note: The effects of structural reforms are quantified using the methodology of (Guillemette and Turner, 2021[3]). The set of structural reforms comprises: a reduction in labour tax wedges by a quarter of the difference to the OECD average; improving the Product Market regulation Index to the average of top five performers and the quality of public governance by half of the difference to the average of top five performers; reducing the distance between educational outcomes of children from the highest and the lowest decile of the household income distribution and average education outcomes to the ones observed in Canada, which is a top performer; improving access to adult education to lower the share of adults without completed basic education by 50% and raising spending for active labour market policies by 50%; increasing public investment as a share of GDP to the OECD average and R&D expenditure to the average of top five performers; improving access and quality of child care and early child hood education by increasing public spending as a share of GDP to the average of top five performers.

Source: OECD Long Term Model.

Table 1.1. Structural reforms will address the negative consequences of ageing and raise living standards

Average yearly additional growth in GDP per capita during the next 10 years (in percentage points)

|

Structural reform |

Additional GDP per capita growth (in percentage points) |

|---|---|

|

Raising public investment in infrastructure and R&D |

0.1 |

|

Improving public governance and reducing the administrative burden |

0.1 |

|

Reducing labour taxes, particularly for low-income and second earners |

0.1 |

|

Improving access to childcare and early-childhood education |

0.1 |

|

Improving adult education and expanding active labour market policies |

0.2 |

|

Improving education quality, particularly for children from disadvantaged households |

0.1 |

|

Total |

0.7 |

Note: Same as for Figure 1.3.

Source: OECD Long Term Model.

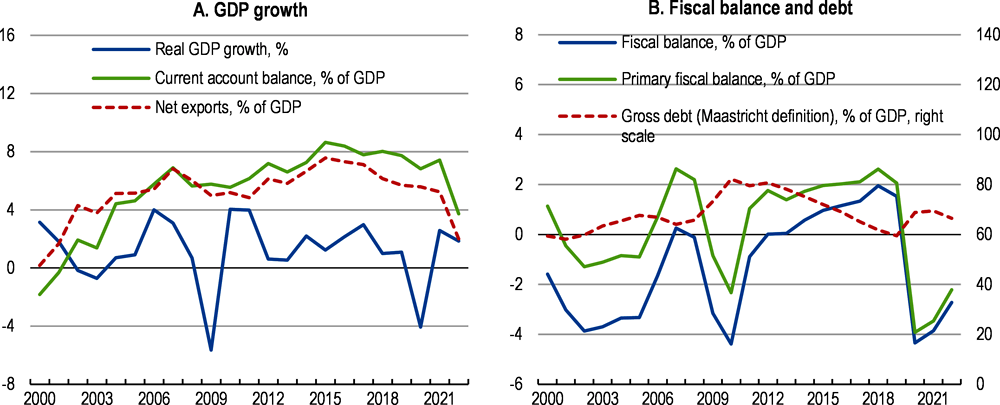

Learning from recent crises to lay the foundations for a strong recovery

Before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the economy had prospered on the basis of a strong export-oriented manufacturing sector and booming construction (Figure 1.4, Panel A). Skilled labour migration from other European countries supported a strong expansion of employment and mitigated labour shortages related to population ageing. The unemployment rate declined from 11% in 2005 to 3% in 2022. The introduction of a national debt brake, which limits the federal structural deficit to -0.35% of GDP and those of the Laender to zero, contributed to strong fiscal consolidation with positive fiscal balances and rapidly decreasing public debt (Panel B).

Figure 1.4. Germany enjoyed strong export-led growth and fiscal surpluses over the past decade

When the pandemic hit, the government used its ample fiscal space to support households and firms with measures amounting to a total of 5.5% of GDP from 2020 until 2022 (Box 1.1). This was enabled by a suspension of the national debt brake for 2020 and 2021, which was extended to 2022. While grants to firms and the short-term work scheme helped to protect jobs and sustain domestic demand, their design likely hindered the reallocation of production factors to booming sectors and firms, thereby exacerbating existing labour shortages and capacity constraints (Box 1.1). To better target support measures during the next crisis, policy impact evaluation needs to improve, which notably requires abolishing legal constraints to access, merge and analyse administrative micro data. The short-term work scheme would benefit from stronger incentives for training and job-search, which should increase over time.

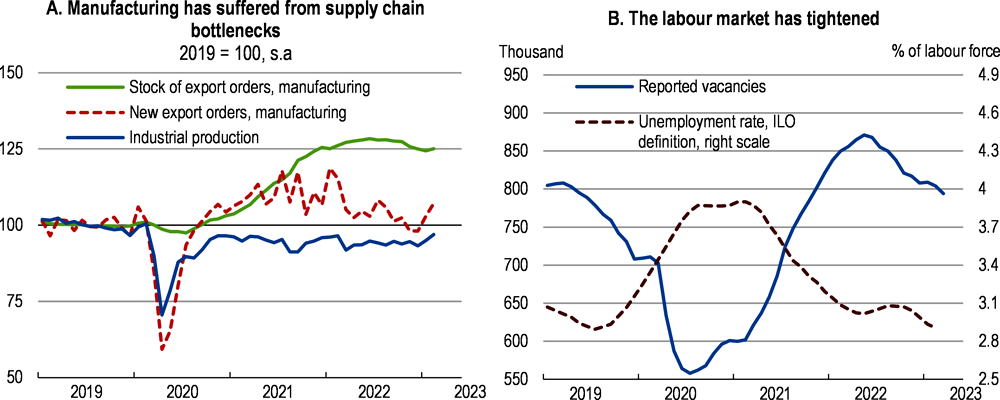

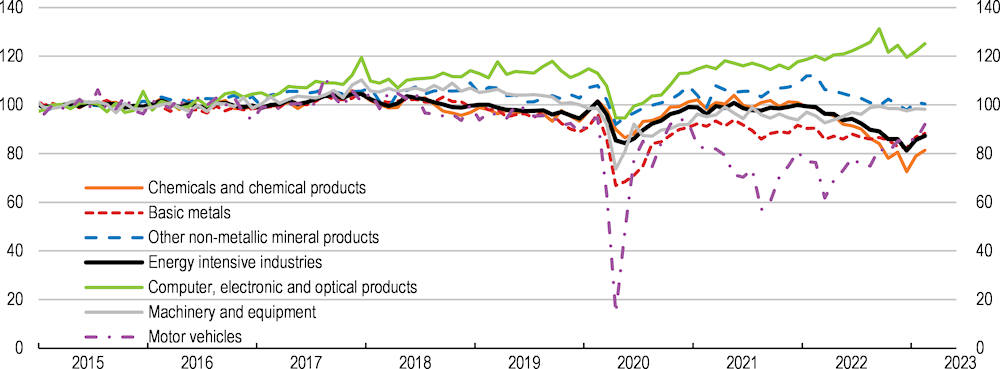

A strong health system kept COVID-19 related death rates lower than in many other EU countries (OECD, 2022[8]). However, a lack of digitalisation in health administration complicated test-track-and-trace strategies, and an initially limited availability of vaccines made the extension of containment measures necessary, hampering the effect of the strong fiscal support on private consumption (Schularick, 2021[9]). Supply chain bottlenecks related to the swift global recovery from the pandemic particularly hit German manufacturing sectors, which are highly integrated into global value chains, leading to a large export order backlog (Figure 1.5). Intensifying labour shortages, exacerbated by mobility restrictions during the pandemic, also help to explain the weak recovery of industrial production, particularly in construction.

Figure 1.5. A strong post-pandemic recovery was mitigated by supply chain bottlenecks and labour shortages

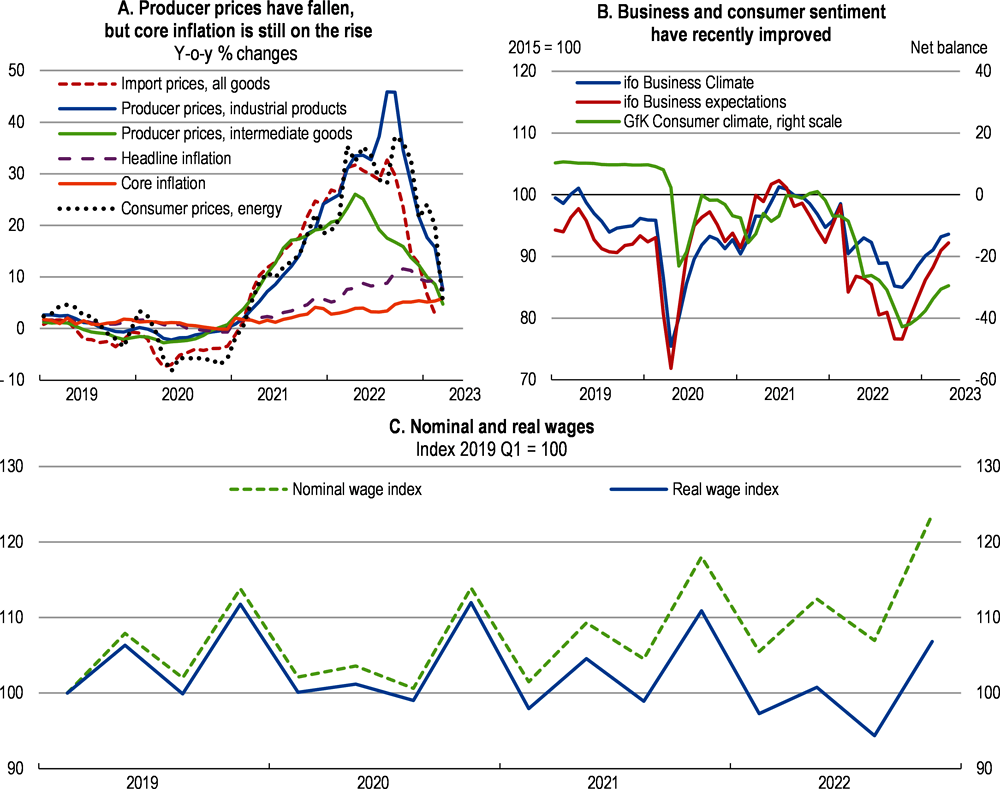

When Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine began, a strong recovery was under way. Private consumption started to rebound due to large excess savings of households and the easing of pandemic-related containment measures. Manufacturing was set to rebound with the loosening of supply chain bottlenecks later in the year. However, rising inflation and plummeting consumer and investor confidence due to the war have slowed down the recovery (Figure 1.6). Producer prices had strongly increased due to soaring energy costs and persistent supply chain bottlenecks, and the pass-through to consumer prices has broadened inflationary pressures. High inflation has reduced real incomes and excess savings, dampening the rebound of private consumption. Real wages were down by 4.6% in the third quarter of 2022 compared to a year earlier, but have recovered since then due to rising nominal wages (Figure 1.6, Panel C). Business confidence has plunged, particularly related to rising uncertainty about energy security, weighing on investment.

The government took bold actions to support households and firms, reduce uncertainty and secure energy supply, contributing to recent improvements in business and consumer confidence (Figure 1.6). Three relief packages estimated at EUR 95 billion (2.6% of GDP) and an energy support fund of EUR 200 billion (5.5% of GDP) financed by credit allowances were put in place. The relief packages include various measures to support real incomes, comprising both targeted transfers through social assistance and housing allowances, and non-targeted ones such as one-off payments to all employees, pensioners and students as well as a temporary VAT tax reduction for gas and hospitality services. Besides temporary measures and one-off transfers for 2022 and 2023, the three relief packages also include many permanent policy changes, which had been planned by the government in the 2022 and 2023 budgets, such as an inflation adjustment of the income tax schedule, the abolishment of the renewable energy surcharge or a reform of the housing allowance system. These measures can be executed within the current budgets for 2022 and 2023, as high inflation led to upward revisions for tax revenues.

Figure 1.6. Inflation and uncertainty are high and nominal wages have started to pick up

The debt-financed energy support fund will finance liquidity support, equity injections and grants for firms as well as a subsidy of electricity and gas bills until December 2023, with an option to prolong it until April 2024 (Box 1.2). The subsidy scheme preserves incentives to save energy and adapt to potentially permanently higher prices, but it is not well targeted at vulnerable households and highly exposed firms. Although the government made the subsidies subject to personal income taxes above a threshold of yearly income of EUR 67,000, which introduces a progressive element, improving energy use data, for example by accelerating the roll-out of smart meters, and allowing linking this with other household data is key to improve the targeting of future support measures. A cash-transfer system is being developed to support vulnerable households during the green transition. While the system could also have helped to better target energy price support, its development has been hampered by IT and data protection issues and a lack of coordination and cooperation across ministries and levels of government. Accelerating the development of the system should be a key priority. Developing short-term monthly indicators on the financial situation and cost structures of firms, such as indicators used for the German Business Panel, could help to better target firm support measures ex-ante (Box 1.1). Early-warning systems to detect firms at risk of insolvency can help to target support during and after a crisis and have been implemented in Denmark and France (Moeller and Mukherjee, 2019[10]; Epaulard and Zapha, 2022[11]; Demmou et al., 2021[12]).

Excluding permanent policy measures that are not related to the energy crisis as well as equity injections, total energy price support is estimated at about 1% of GDP in 2022, 2.4% in 2023, and 0.6% in 2024, although falling retail energy prices resulting from falling wholesale prices, as observed since December 2022, would strongly reduce the fiscal costs (Box 1.2) (OECD, 2022[13]). The electricity price subsidy is to be partly financed by a windfall tax on electricity producers. To stabilise the gas market, the government nationalised the biggest gas importer, which was on the brink of default due to the stop to Russian gas imports and high spot market prices, with an estimated budgetary cost of EUR 40 billion (around 1% of GDP). Allowing for the adjustment of contract prices for its clients to reflect higher purchasing costs could help to reduce fiscal costs and provide additional incentives for gas savings, but could also imply a higher number of gas consumers applying for energy price support (Bundesbank, 2022[14]).

To become independent from gas imports from Russia, the government has required private operators to fill up gas storage tanks while providing guaranteed loans (gas storage levels reached 100% in November 2022 and stood at 66% in April 2023), accelerated the construction of LNG terminals and helped to negotiate trade deals with LNG exporters. Electricity production using gas has been reduced and replaced by reactivated coal power plants, while the three remaining nuclear power plants, which were to shut down on 1 January 2023, continued operating until April 2023. The possibility of further postponing the end of nuclear power use to stabilise energy supply in the short term has been discussed, but was rejected, as the extension for a short duration would be costly in regard of the need to order the necessary nuclear fuel and update security measures.

Box 1.1. Evaluation of Covid-19 support measures

Pandemic related fiscal support was high compared to other EU countries and comprised grants to firms (2.1% of GDP), subsidised credit lines (1.65% of GDP), loan guarantees (0.5% of GDP) and more generous short-term work support (1.3%) (BMWK, 2022[15]). Analysis using data from the German Business Panel shows a positive stabilisation effect of these measures (Bischof et al., 2021[16]). In industries most affected by the pandemic, which also received the highest share in distributed grants (hospitality with 33%, retail with 14% and culture, recreation, and entertainment with 12%), the firm survival probability increased on average by 35 percentage points compared to a counterfactual without support measures.

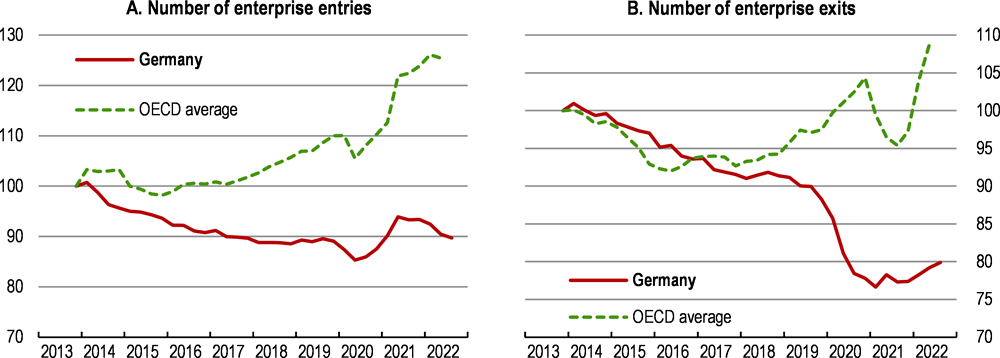

However, there are signs that the generous support might have also slowed down business dynamism (Barnes et al., 2021[17]). The number of firm exits fell significantly below the OECD average and is still significantly lower than before the pandemic (Figure 1.7). Firm entries have slightly increased, but the gap to other OECD countries has widened significantly. Most firms did not use available credit lines but opted for generous grants that reimbursed a share of fixed costs depending on firm-specific revenue losses. These grants have not only covered the aggregate pandemic shock, but potentially also firm-specific shocks. This could have been prevented by conditioning grants on sector-wide revenue losses and cost structures, for example by using indicators from the German Business Panel, or focusing support on liquidity provision through subsidised loans and loan guarantees or tax deferrals (Bischof et al., 2021[16]; Demmou et al., 2021[12]). Focusing on liquidity support instead of grants might have been a better solution, as the equity ratio of small and medium size firms had strongly increased from 18% in 2002 to 32% in 2019, making corporate over-indebtedness due to increased emergency loans less likely (KFW, 2022[18]).

Moreover, Germany was the only EU country with rising replacement rates over time in the short-term work scheme. This in combination with an extended eligibility period of 24 months has strongly reduced job-search incentives and labour reallocation (Heinemann, 2022[19]; Calligaris et al., forthcoming[20]). Training uptake within the scheme was low as the pandemic-related special clause, which reimbursed 100% of social security contributions for employers, counteracted the training incentives of the main scheme, which consist in reimbursing 50% of social security contribution during training periods. The total fiscal costs of the short-term work scheme amounted to about EUR 42 billion in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 1.7. Business dynamism has markedly slowed down

Enterprise entries and exits (2013 Q4 = 100, 4-quarter moving average)

Box 1.2. Electricity and gas price support

The gas price subsidy follows a two-step approach. In the first step, households and SMEs received a transfer equal to one twelfth of the estimated annual consumption for 2022 multiplied by the gas price for December 2022. To provide timely relief, the upfront payment for the gas bill was waived in December, while the actual transfer will be settled later. In the second step, the gas bill will be subsidised from January 2023 until December 2023 with an option to be prolonged until April 2024. Households and SMEs will receive a discount equal to the difference between their contract price and the targeted subsidised price level (12 cent/kWh) multiplied by 80% of past average consumption. This lump-sum scheme fully preserves gas savings incentives, as lower consumption reduces the final gas bill without affecting the transfer. For large industrial clients, a gas price subsidy based on 70% of past average consumption is in place since January 2023. The subsidy is capped between 2 and 150 million euros, depending on whether a company is part of an energy-intensive sector, proves to have suffered a sufficiently high rise in energy costs and drop in earnings, accepts restrictions on paid bonuses and dividends, and agrees to keep its employment in Germany at current levels until 2025. Similar to gas, the use of other heating materials is subsidised. The subsidy for electricity prices, in place from January 2023 onwards, is designed similarly and partly financed by a windfall tax on electricity producers. Estimates for the fiscal costs of the gas, heating and electricity price subsidies amount to EUR 54 billion and EUR 43 billion, respectively.

A main advantage of the schemes is that the subsidised price levels for households and SMEs remain about 100% and 33% above pre-crisis levels for gas and electricity, respectively, which preserves incentives to raise energy efficiency and adapt to permanently higher fossil energy prices which will come along with carbon pricing. Moreover, the lump-sum nature of the subsidy preserves saving incentives even below the level of 80% of past average consumption, which is key to bring down energy wholesale prices and reduce the likelihood of gas rationing. As the subsidy is tied to contract prices, this ensures that the subsidy declines if retail energy prices fall as a consequence of decreasing wholesale prices.

High energy prices and uncertainty related to energy security particularly affect energy-intensive industries, which compete with foreign firms in domestic and foreign markets (Figure 1.1, Figure 1.8). Average output in energy-intensive industries has dropped by about 10% in 2022, but has increased since then due to falling energy prices. Not all industries and firms have been equally affected, and total industrial production has been broadly stable since the onset of the war (Figure 1.5). Even in high energy-intensity industries, the import substitution of certain highly energy-intensive products stabilised other production processes. Although output in the chemical industry has declined by 26% in 2022, substituting ammoniac production by imports has allowed to continue other key production processes and helped to mitigate negative spill-overs to other sectors (Bachmann et al., 2022[21]; Mertens and Mueller, 2022[22]). Production in automotive, machinery and equipment and computer, electronic and optical goods industries has significantly increased since the onset of the war, mainly driven by easing supply chain bottlenecks.

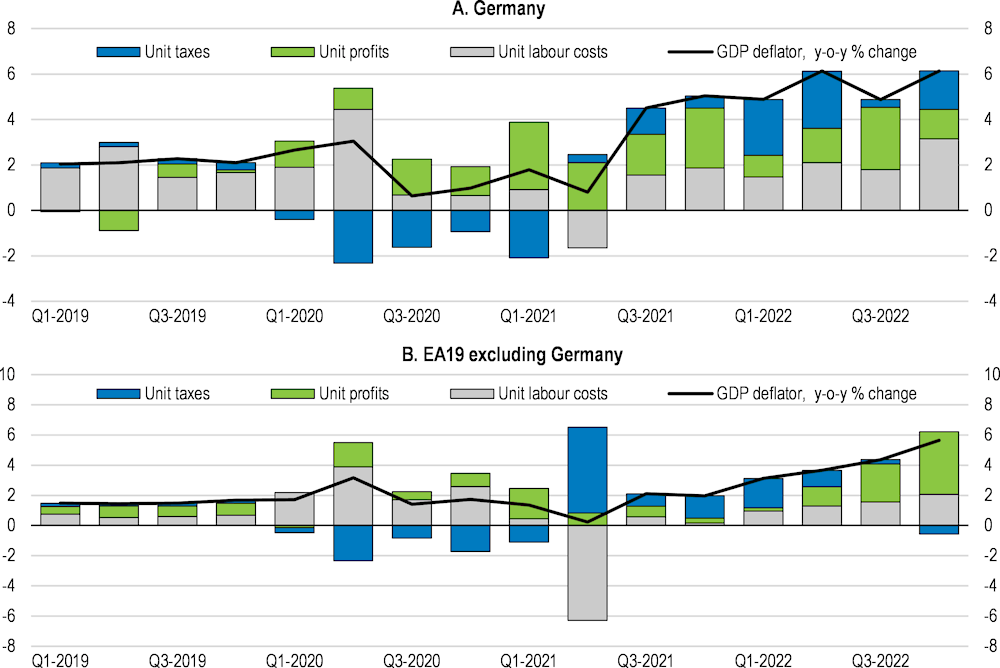

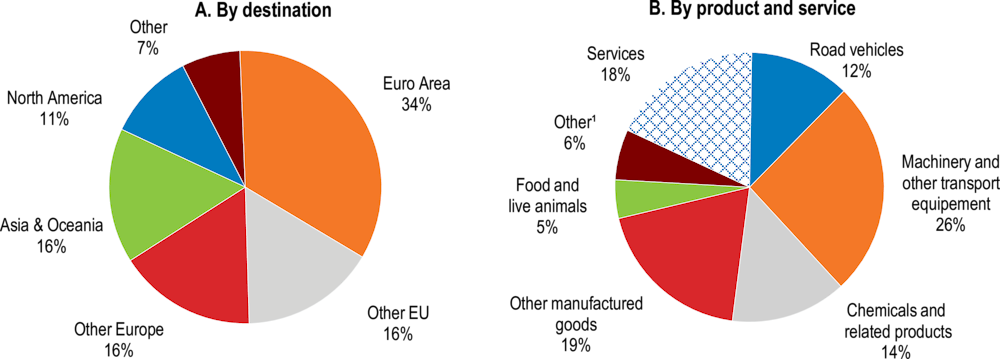

Many firms sell high-quality products and have considerable market power to pass-on higher input costs to domestic and international clients (Figure 1.9) (Böhringer, Rutherford and Schneider, 2021[23]; Rangnitz, 2022[24]). Despite increasing relative export prices, export quantities expanded by 3% in 2022, particularly driven by automotive, computer and electronic products, and machinery and equipment, which account for a major share of exports (Figure 1.8, Figure 1.10). Many large firms made record profits up to the third quarter of 2022 (Sommer, 2022[25]). Thus, firm support for rising energy costs should be well-targeted to firms that have difficulties to obtain short-term financing. It should mainly consist of short-term liquidity provision to not impede necessary structural change, for example by providing subsidised loans and credit guarantees or tax deferrals, and maintain energy saving incentives (Box 1.1,Box 1.2) (Heinemann, 2022[19]).

As higher energy costs may persist during the green transition, the best policy to support firms is to improve the business environment and foster innovation to enable quality upgrades of products and services. This should include lowering the administrative burden by accelerating the digitalisation of public administration, streamlining planning and approval procedures for infrastructure investments, simplifying the tax system, strengthening competition enforcement and addressing skilled labour shortages (see below). To ensure affordable and stable energy supply in the medium run, it is key to accelerate the expansion of renewable energy supply, upgrade the grid and storage infrastructure and better integrate European electricity and energy markets (see Chapter 2) (Bundesnetzagentur, 2023[26]; Abrizio et al., 2022[27]). Simulations for this survey using a multi-sector and multi-country computable equilibrium model show that emission abatement and higher carbon prices will negatively affect some energy-intensive and trade-exposed industries in the medium term, such as metal and oil refinery industries (see Chapter 2). However, other industries, such as machinery and equipment and the automotive industry, can more easily substitute away from fossil fuel, replace highly energy-intensive domestic inputs by imports and pass on higher input costs to domestic and foreign consumers. Electricity prices are likely to increase, but a better integration of the European electricity grid and facilitating the expansion of renewable energy supply can significantly mitigate risks.

Figure 1.8. Not all industries suffer equally from high energy prices

Output of energy intensive and other industries (Production index, 2015 = 100)

Figure 1.9. Many firms were able to pass on higher inputs costs and raise profits

GDP deflator decomposition by income side, contributions, % points

Figure 1.10. Manufactured capital goods dominate exports

Exports of goods and services, % of total, 2020

Note:1. Other category includes crude materials and inedible materials, mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials, animal and vegetable oils, fats and waxes, commodities and transactions.

Source: OECD International Trade Statistics.

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and related economic sanctions have affected trade with Russia, which amounted to 2.3% of total trade in 2021. Before the start of the war, Germany was highly dependent on Russian gas, oil and coal, with around one-third of primary energy supply coming from Russia. Since then, energy imports from Russia have strongly declined due to the EU coal and oil embargo, the destruction of gas pipelines, and the rapid diversification of energy suppliers. In February 2023, less than 1% of German energy imports still came from Russia. The value of German exports to Russia has decreased by 45% on average in 2022 compared to 2021, mainly driven by plummeting exports of automotive, machinery and equipment and chemical products, while pharmaceutical exports strongly increased. In 2020, the stock of German foreign direct investment (FDI) in Russia amounted to about EUR 20 billion, 1.5% of the total German FDI stock abroad. Many German companies have closed their subsidiaries and production plants in Russia, but the losses from trade with Russia have not led to major firm failures.

The war has also led to a net inflow of about 1 million refugees from Ukraine by February 2023 (1.3% of the population), many of them women and children. In 2022 and 2023, the federal government supports municipalities and the Laender with EUR 4.25 billion to facilitate the integration of children into schools and to provide housing and social assistance for refugees. The Laender, which are responsible for the education system, offer online courses and Ukrainian teaching material to help pupils to continue Ukrainian school classes. Moreover, several hundred Ukrainian teachers have been temporarily hired by German schools via fast-track procedures. For adult refugees, free access to labour market programmes and language courses and a two-year residence permit was granted. However, less than 22% have found a job so far, partly due to limited transferability of skills and weak German language skills (Panchenko and Poutvaara, 2022[28]). Further facilitating recognition procedures for qualifications through skill validation, particularly in highly regulated sectors with high labour shortages such as education and health, and improving the supply of childcare facilities are key to support labour market integration.

The economy will slowly recover, driven by exports

The economy will slowly recover due to the easing of supply chain bottlenecks, a large export order backlog and a pickup in export demand (Table 1.2, Figure 1.5). Real GDP is projected to grow by 0.3% in 2023 and 1.3% in 2024. Growth will be subdued in 2023 as high inflation reduces real incomes and savings and holds back private consumption (Figure 1.6). Rising interest rates and uncertainty amidst energy price volatility weigh on investment, particularly in housing, but strong government support and lower energy prices will continue to improve investor confidence. Investment will eventually pick up due to high corporate savings and investment needs related to the relocation of supply chains and renewable energy expansion, as well as rising public investment. The unemployment rate will slightly decrease to 2.9% in 2024.

Inflation will remain high in 2023, averaging 6.6%, due to the pass-through of energy and producer prices to consumers and rising wage pressures, but will gradually moderate over the projection period. Due to longer-term contracts expiring in 2023, consumer prices for electricity and gas will continue to rise as providers pass on higher input costs when contracts are renewed (Figure 1.1). Wage growth will rise, helped by the minimum wage increase from 48% to 60% of the median wage in October 2022, continued labour shortages and pressure from unions to preserve the purchasing power of workers. Tighter monetary conditions, fading energy price pressures and fiscal tightening will help to bring down inflation to 3% in 2024. Real wages will grow in 2024 supporting a recovery of private consumption.

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Annual percentage change, volume (2015 prices)

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Projections |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Current prices (billion EUR) |

2023 |

2024 |

||||

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) |

3 479.4 |

-4.1 |

2.6 |

1.9 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

|

Private consumption |

1 807.4 |

-5.9 |

0.4 |

4.4 |

-0.2 |

1.4 |

|

Government consumption |

703.2 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

1.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

|

Gross fixed capital formation |

745.4 |

-3.0 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

-1.8 |

1.3 |

|

Housing |

222.4 |

3.7 |

0.3 |

-2.0 |

-5.8 |

-1.5 |

|

Final domestic demand |

3 256.0 |

-3.1 |

1.3 |

2.7 |

-0.5 |

1.2 |

|

Stockbuilding1 |

24.9 |

-0.2 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.0 |

|

Total domestic demand |

3 280.9 |

-3.3 |

2.0 |

3.2 |

0.1 |

1.1 |

|

Exports of goods and services |

1 627.6 |

-10.1 |

9.5 |

3.0 |

1.8 |

3.1 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

1 429.1 |

-9.1 |

8.9 |

6.1 |

1.4 |

2.9 |

|

Net exports1 |

198.5 |

-1.0 |

0.8 |

-1.1 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Other indicators (growth rates, unless specified) |

|

|||||

|

GDP without working day adjustments |

3,473.3 |

-3.7 |

2.6 |

1.8 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

|

Potential GDP |

. . |

1.0 |

1.0 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

|

Output gap² |

. . |

-3.7 |

-2.2 |

-1.3 |

-1.7 |

-1.1 |

|

Employment |

. . |

-0.9 |

0.4 |

2.6 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

|

Unemployment rate (% of labour force) |

. . |

3.7 |

3.6 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

2.9 |

|

GDP deflator |

. . |

1.8 |

3.1 |

5.5 |

6.6 |

3.1 |

|

Harmonised index of consumer prices |

. . |

0.4 |

3.2 |

8.7 |

6.6 |

3.0 |

|

Harmonised index of core inflation³ |

. . |

0.7 |

2.2 |

3.9 |

5.7 |

3.4 |

|

Household saving ratio, net (% of disposable income) |

. . |

16.4 |

15.1 |

11.3 |

11.3 |

11.5 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

6.8 |

7.4 |

3.7 |

5.7 |

6.3 |

|

General government financial balance (% of GDP) |

. . |

-4.3 |

-3.9 |

-2.7 |

-2.2 |

-1.0 |

|

Underlying government primary financial balance² |

. . |

-1.9 |

-2.3 |

-1.6 |

-0.7 |

0.4 |

|

General government gross debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

78.5 |

77.6 |

78.4 |

77.7 |

77.5 |

|

General government gross debt (Maastricht, % of GDP) |

. . |

68.9 |

69.4 |

66.5 |

65.8 |

65.6 |

|

General government net debt (% of GDP) |

. . |

32.2 |

30.7 |

31.3 |

31.4 |

31.2 |

|

Three-month money market rate, average |

. . |

-0.4 |

-0.5 |

0.3 |

3.2 |

3.4 |

|

Ten-year government bond yield, average |

. . |

-0.5 |

-0.4 |

1.1 |

3.0 |

3.3 |

1. Contribution to changes in real GDP.

2. Percentage of potential GDP.

3. Harmonised consumer price index excluding food and energy, alcohol and tobacco.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Economic Outlook 112 database.

A major downside risk arises from rising gas prices and potential gas rationing next winter that could imply severe production disruptions, if planned fiscal support measures do not sufficiently preserve price incentives for gas savings, weather conditions are unfavourable, and delays occur in building up the LNG infrastructure. Despite filled up gas storage and the opening of three LNG terminals since December 2022, gas consumption needs to be reduced by around 20% to further reduce the risk of gas shortages next winter. Industry has reduced gas consumption by around 23% in January (compared to the average over 2018-21), including through imports of gas-intensive products and modest output reductions in some energy-intensive industries (Mertens and Mueller, 2022[22]). Energy savings should be further incentivised by a gas auction mechanism for firms to supply their excess gas capacity. Households and small firms reduced gas consumption by 23% due to high prices and relatively warm weather in January compared to the 2018-21 average, indicating that maintaining price incentives is key to incentivise gas savings.

New waves of the pandemic could further depress private consumption or exacerbate supply chain bottlenecks. Geopolitical tensions could lead to further trade disruptions and the need to relocate supply chains. Reshoring and rising protectionism will particularly hurt export sectors. Rising interest rates could cause strong corrections in housing markets, affecting financial markets. On the upside, a quicker end of the war could restore investor and consumer confidence and lower energy prices. The easing of containment measures in China will raise demand for German exports and contribute to the easing of supply chain bottlenecks (Box 1.3).

Table 1.3. Events that could lead to major changes in the outlook

|

Risks |

Possible outcomes |

|---|---|

|

A cold winter and high gas demand leading to gas rationing. |

The closing down of activities that are not easily substitutable by imports would lead to cascade effects and decreasing production in other sectors. Unemployment would rise and firm failures would raise banking sector risks. Inflation would further increase damping private consumption. |

|

New disruptive waves of the pandemic. |

New containment measures could constrain consumption, leading to firm failures and increased unemployment. Disrupted supply chains would hurt production, while depressed global demand would weigh on exports. |

|

Further increases in trade barriers and other trade distorting measures, such as subsidies and local-content rules, globally. |

A new wave of protectionism, trade distorting subsidies and local-content rules would lower global trade and would be particularly harmful for the German economy, which is highly integrated in international supply chains. |

|

High and persistent inflation requiring steep monetary tightening. |

High mortgage rates could lead to falling housing prices, reducing mortgage values, which together with falling real incomes could raise loan defaults and expose vulnerabilities in the financial system. Higher interest rates could complicate loan rollovers, particularly for energy-intensive firms suffering from high energy prices, raising firm insolvencies and defaults. |

|

The war in Ukraine ends faster than expected and geopolitical tensions decrease. |

Confidence would recover spurring investment and private consumption. Energy prices could decrease, lowering inflationary pressures and allowing central banks to loosen monetary policy, which would stimulate domestic demand. |

Germany’s high exposure to global value chain risk underlines the need for diversification. For example, the share of semiconductors imported from outside of Europe is much higher than in the United Kingdom and Italy (Haramboure et al., forthcoming[29]). Expanding research and development for high-end technology, such as semiconductors which are key for the green and digital transition, can help to reduce supply-chain risks but should be done in close cooperation with other EU countries to realise economies of scale. Higher demand for resilient supply chains will provide sufficient incentives to scale up production of mature technologies in the European Union. As resilience is a top priority for many trading partners, international coordination is key to prevent a subsidy race, which would distort international investment decisions and have a high fiscal cost.

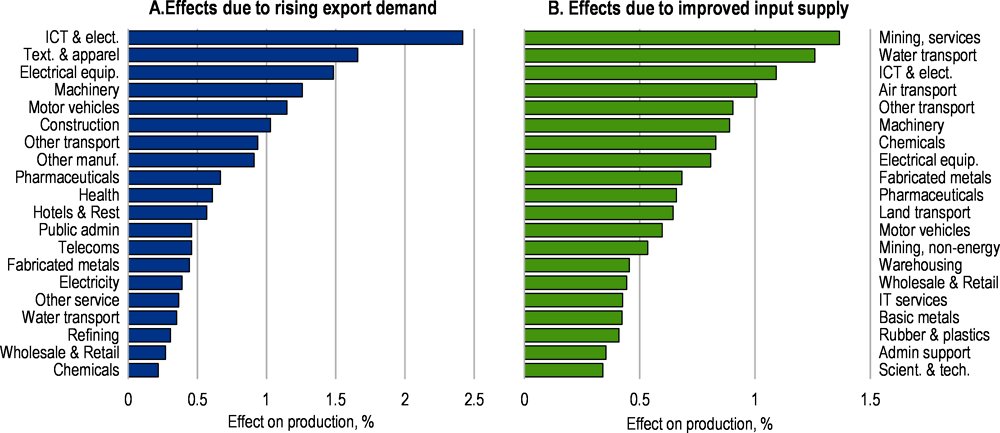

Box 1.3. The effects of an easing of mobility restrictions in China on German industries

An OECD analysis conducted for this survey estimates the effects of reduced mobility restrictions in China on industrial production through rising export demand and improved input supply (Haramboure et al., forthcoming[29]). The demand shock leads to significant output gains, particular in the ICT, textile and electrical equipment sectors (Figure 1.11). The positive effects through easing supply chain bottlenecks are smaller, but still significant and most pronounced in mining, ICT and transport.

Figure 1.11. Germany benefits from easing mobility restrictions in China

Simulated effect of a decrease in Chinese mobility restrictions by 20 percentage points of the Oxford stringency index

Note: The mobility shock roughly corresponds to the decrease in mobility restrictions observed in China from August to December this year, measures by the Oxford stringency index. The sample is restricted to the 20 most affected industries in Germany.

Source: OECD calculations based on (Haramboure et al., forthcoming[29]).

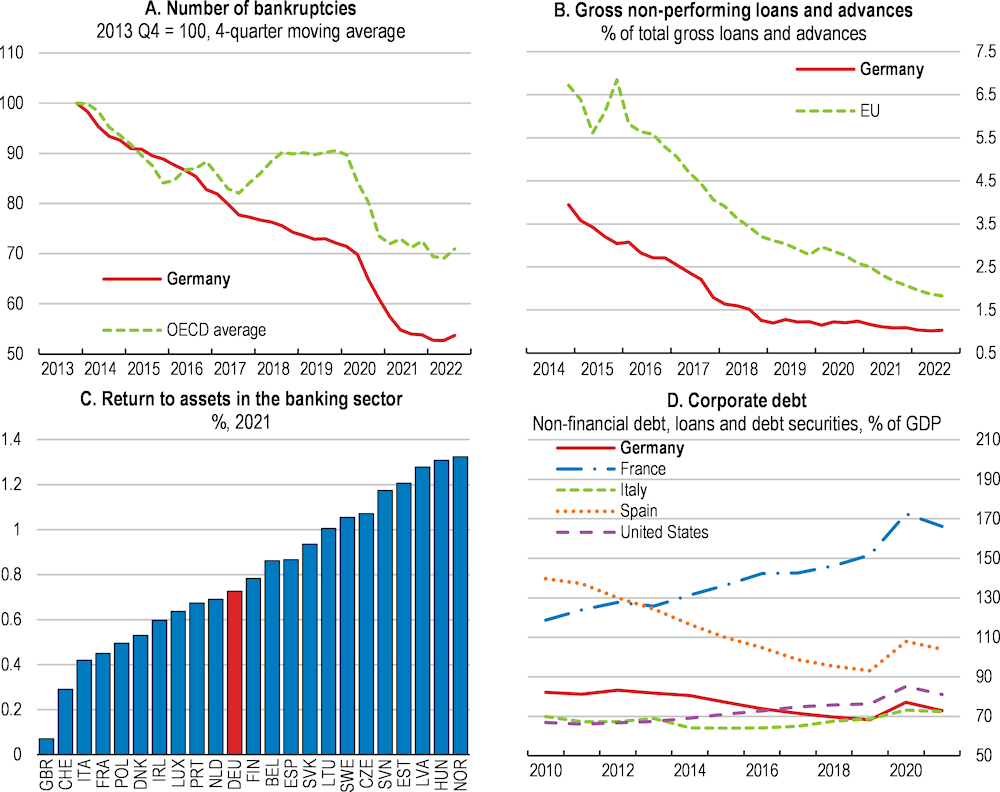

Tightening monetary conditions and high energy prices increase financial market vulnerabilities

The financial sector has weathered the COVID-19 crisis well owing to generous support measures for firms, low interest rates, and high non-financial corporate savings in previous years, as well as to macroprudential and supervisory measures taken during and before the pandemic. The number of corporate insolvencies declined in 2020 and 2021, and is still much lower than in 2019 (Figure 1.12, Panel A). The ratio of non-performing loans stood at 1.1% in the second quarter of 2022 (Figure 1.12, Panel B). Nonetheless, faster-than-expected rises in interest rates, the expiration of COVID-19 support measures in June 2022 and persistently high energy prices might raise the number of firm insolvencies, particularly of energy-intensive companies. Unlike the pandemic, the war might have longer-term structural impacts on energy markets and supply chains. Concerns over short-term liquidity of energy utilities have prompted the government to implement a EUR 67 billion emergency support scheme in the form of short-term liquidity lines and loan guarantees. However, uptake has been low, as the nationalisation of the two biggest gas importers with a fiscal cost of up to EUR 50 billion has stabilised the sector.

Structurally low bank profitability remains a persistent source of vulnerability, even though it has improved since 2021 due to rising interest rates (Figure 1.12, Panel C) (Altavilla, Canova and Ciccarelli, 2020[30]; IMF, 2022[31]). The recent turmoil in the European and US banking sector could lead to higher risks, increased costs and lower profitability. After narrowing since the pandemic, the fallout from the war has raised spreads for Credit Default Swaps (CDS) on the back of low profitability, and the two largest German commercial banks continue trading at a discount relative to many European peers. The value of some bank assets, such as long-term bonds, could further decline due to the rise in interest rates. Nonetheless, the share of bonds in the balance sheets of banks and the net duration risk, which measures how much banks lose if interest rates rise, are relatively low (ECB, 2022[32]). The capital buffers of German banks remain at comfortable risk-weighted levels due to tighter regulatory measures since the global financial crisis (IMF, 2022[31]; ECB, 2022[32]). Credit growth was in line with GDP growth in recent years and, in contrast to other OECD countries, the debt of non-financial firms remains stable and at moderate levels (Figure 1.12,Panel D).

Figure 1.12. Vulnerabilities related to corporate debt remain contained so far

Source: OECD Timely Indicators of Entrepreneurship database; ECB; IMF Financial Soundness Indicators database; IMF.

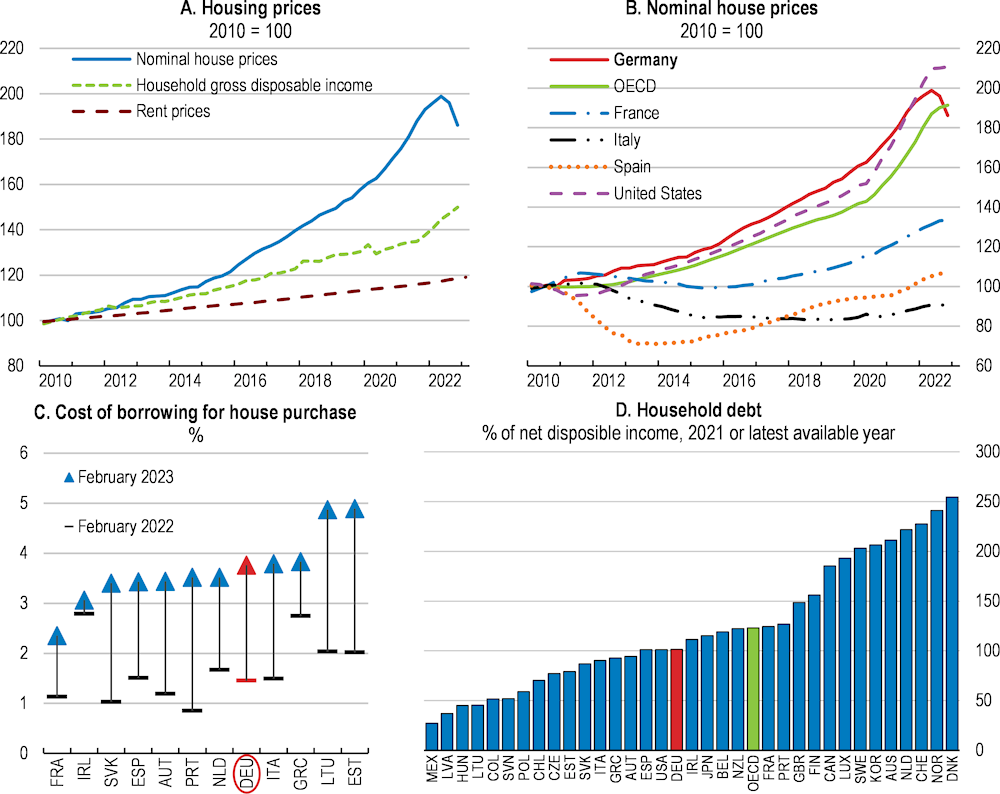

Monetary policy tightening and rising mortgage rates might lead to strong corrections in housing prices, raising risks related to household debt. House prices have outpaced rents and household income significantly since 2012 (Figure 1.13, Panel A and B). Housing loans continued to grow at record levels until the second quarter of 2022, but have sharply declined thereafter (IMF, 2022[31]). The Bundesbank estimated that residential property was overvalued by 15% to 40% in 2021 (Bundesbank, 2022[33]). Mortgage borrowing costs have risen by 1.6 percentage points since September 2021, raising the risk of a strong downward correction in housing prices (Battistini, Gareis and Moreno, 2022[34]). As the share of fixed-rate loans is high, rising mortgage rates will mainly affect credit risk through decreasing housing prices and mortgage values (Figure 1.13, Panel C). Moreover, high energy prices and inflation strongly reduce real incomes, raising default risks, particularly for poorer households, although average household debt remains below the OECD average (Figure 1.13, Panel D).

The sensitivity of banks' balance sheets to evolving risks related to housing markets and corporate debt should be closely monitored. Recently tightened macroprudential measures should remain in place. To reduce banks' vulnerability to changes in housing prices, the authorities appropriately raised the counter-cyclical capital buffer to 0.75%, from zero previously, and introduced a sectoral systemic risk buffer of 2% on loans secured by domestic residential real estate to apply from February 2023. Borrower-based measures, such as limits on loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios on new lending, should be strengthened, which requires more granular data on borrowers’ risk profiles and lending standards of banks as well as credit statistics by region and type of lender. In addition, financial sector resilience can be strengthened by better assessing and disclosing risks from climate change and mitigation policies (Chapter 2).

Figure 1.13. Housing market related risks have increased

Source: OECD Analytical House Price database; Eurostat; ECB; OECD National Accounts database.

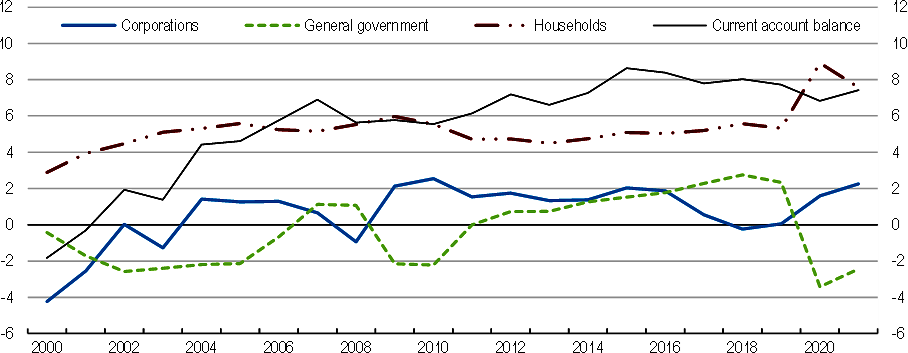

High domestic saving could help to support start-ups and innovation

Germany’s large current account surplus reflects the gap between high saving of corporates and households and low domestic investment, leading to substantial capital outflows (Figure 1.14). High capital outflows are strongly related to structural factors that weaken domestic investment demand and business dynamism (see the previous OECD Economic Survey of Germany). These include high administrative burden and other regulatory barriers to market entry and competition, but also skilled labour shortages, weak entrepreneurship skills and a banking sector that has difficulties in providing credit to young and innovative firms with high growth potential (Falck et al., 2022[35]; Klug, Mayer and Schuler, 2021[36]). Moreover, generous tax exemptions for income from selling or renting real estate distort investment decisions and hinder allocation of capital to innovative start-ups (see below). Rising public investment in the green and digital transition has the potential to crowd in more private investment but should be complemented by addressing existing structural barriers.

Figure 1.14. A large share of domestic saving is not invested in Germany

Saving-investment balances by sector and current account, % of GDP

Investment in ICT and knowledge-based capital (KBC) is particularly low, and the contribution of ICT capital to growth in Germany is half that of the United States (see the previous OECD Economic Survey of Germany). This is related to an underdeveloped venture capital sector and the risk-aversion and limited expertise on new technologies in many banks. The government established an equity fund for future technologies, which is administered by the public development bank KfW, directly providing funding for the growth phase of start-ups and high-risk innovation and crowding in private capital. However, more should be done to foster the contribution of institutional investors to risk-related finance. Less than 8% of assets of retirement saving plans are invested in equity, as against 27% on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[37]). The contribution of institutional investors to VC funds is much smaller in Germany than in Nordic countries. Allowing public and private pension funds, such as company pension funds, and other retirement saving plans to invest a larger share of their assets in VC funds, while introducing loss-prevention guarantees for VC investments, could help to improve innovation finance (OECD, 2022[38]). Facilitating the use of stock-ownership option plans (ESOPs) could ease financing constraints of start-ups, allowing them to substitute wage payments by offering employees company shares.

Table 1.4. Past recommendations and actions taken on support for start-ups and innovation

|

Previous recommendations |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Improve conditions for firms to invest in knowledge-based capital, including by reviewing the cap for R&D tax incentives to make them more applicable to mid-range companies. |

No action taken. |

|

Improve the effectiveness of start-up and growth financing instruments, including by avoiding complexity, scaling up later stage funding and improving conditions for institutional investors to invest in venture capital. |

In 2021, the government established the Future Fund, which was equipped with EUR 10 billion, to improve access to credit for the growth phase of start-ups and further develop the venture capital market. |

|

Accelerate SMEs’ digital transformation by swiftly implementing existing SME support, increasing it if needed, and ensuring that investment incentives for physical capital do not discourage expenditures on digital services. |

The new start-up strategy published in July 2022 aims to improve access to data and finance for young firms, tackle the shortage of skilled workers, and reduce bureaucratic hurdles. |

Addressing skilled labour shortages is key to improve the business environment

Skilled labour shortages have intensified and pose a major business risk to many companies (Figure 1.15) (DIHK, 2022[39]). The average duration of vacancies increased from 61 days in 2009 to 119 in 2021, with shortages particularly severe in the areas of nursing, medical professions, construction, craft occupations as well as information technology (IT) (BA, 2022[40]). Capacity constraints in the construction sector pose a serious challenge to expand renewable energy supply and greening the housing and transport sectors (see Chapter 2). Population ageing will further aggravate these shortages with negative effects on potential growth (Figure 1.2). This also risks to significantly reduce the competitiveness of many manufacturing sectors (Box 1.4).

To address skilled labour shortages, it is crucial to support the labour market integration of women, elderly and low-skilled workers, facilitate skilled labour migration, and expand adult learning opportunities (Table 1.1). A labour tax reform would help to raise labour supply of women and low-skilled workers, while better incentives to work longer combined with better working conditions would help to raise effective retirement ages (see below). Improving adult learning and continued vocational education and training (CVET) opportunities, with a specific focus on low-skilled and older workers, and supporting labour mobility are key to help workers affected by the green and digital transition to adjust to changing skill demands and relocate to booming sectors and occupations (see Chapter 2). Improving educational quality to equip younger generations with the skills needed for the green and digital transition, with a particular focus on children from disadvantaged households, will support potential growth in the medium to long term. This should be combined with policies to strengthen business dynamism and innovation, including the adoption of digital technologies, which has large potential to raise productivity and mitigate labour shortages (see Chapter 2 and the previous OECD Economic Survey of Germany).

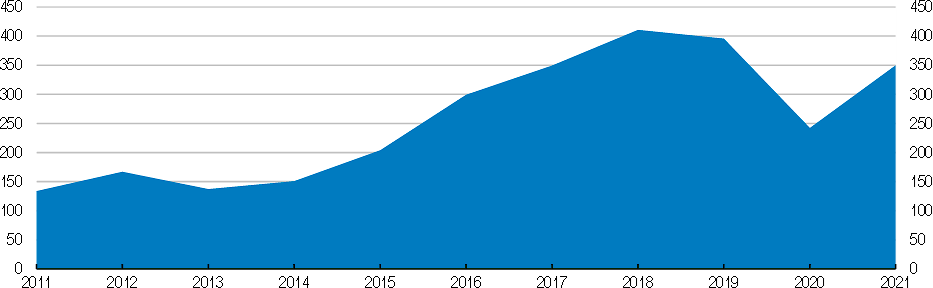

Figure 1.15. Skilled labour shortages are mounting

Skilled labour gap (number of vacancies that cannot be filled), thousand

Note: The skilled labour gap is equal to the number of qualified workers missing in a specific occupation to fill all open positions within a region aggregated over all occupations and regions.

Source: KOFA (2022).

Increasing skilled migration is one key policy lever to address skilled labour shortages and would also help to stabilise the pension system (see below). To maintain competitiveness of export-oriented manufacturing sectors, supply of workers with vocational education and training (VET) is particularly important (Box 1.4) (Bickmann, Grundke and Smith, forthcoming[1]). A recent draft bill aims to facilitate obtaining a work permit for migrants with a job offer and job experience by waiving the obligatory recognition of foreign degrees in non-regulated professions under certain conditions. It also aims to promote job seeker visas through a point-based system, where a recognised foreign degree is an advantage but not a pre-condition anymore. This planned point-based system should not be confused with the point-based systems used in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, which are used to select migrants with a long-term capacity to integrate and grant immediate permanent residence without the requirement to find a job within a certain period. Despite these significant reform steps, complex and lengthy administrative procedures necessary to receive a visa and work permit and a lack of digitalisation cause uncertainty and high costs for migrants and potential employers. Accelerating the digitalisation of bureaucratic processes, particularly the visa application, and establishing centralised migration offices in the Laender that coordinate the different necessary administrative processes is key. A recent OECD survey points to large potential demand for high-skilled migrants in the German labour market, particularly engineers and IT experts. Potential migrants value the career and employment opportunities, high quality of life and security in Germany and are willing to learn German if this improves their chances to work in Germany (OECD, 2022[41]). As intra-EU migration will likely slow down due to population ageing, scaling up current advertisement and recruitment measures in non-EU countries, improving support for job-search and promoting German language courses abroad is crucial to make the most of this migration potential. Since Germany is already highly active in the field of international VET cooperation, these initiatives could also help to attract future skilled migrants (Azahaf, 2020[42]).

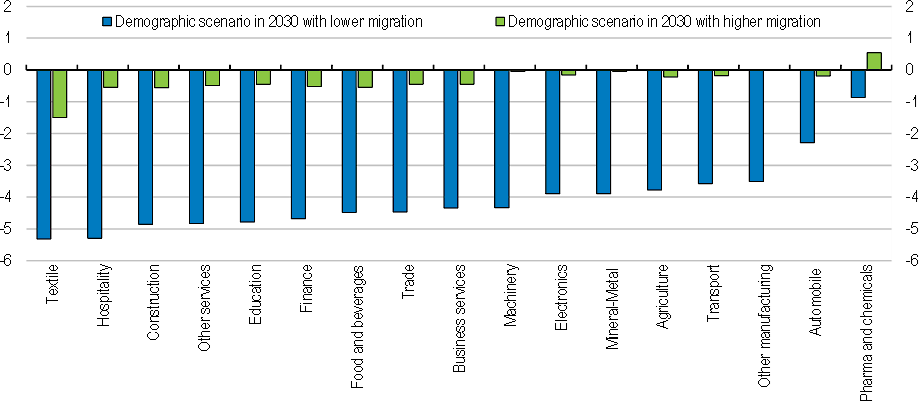

Box 1.4. Migration can help to maintain the competitiveness of manufacturing

The OECD’s METRO model is a multi-country and multi-sector computable general equilibrium (CGE) model that allows to analyse the consequences of global demographic change and migration on the German economy (Bickmann, Grundke and Smith, forthcoming[1]; Smith, Kowalski and van Tongeren, 2022[43]). The United Nations (UN) World Population Prospects for 2030 are used to simulate the economic effects of various migration scenarios compared to a baseline with working age population data from 2020 and average international migration flows from 2010-2020. The simulations abstract from technological change and automation, which could mitigate negative effects of labour shortages on production potential. However, they allow for the substitution between capital and labour. Capital is mobile across sectors, but the total endowment is fixed. The structural parameters of the model are calibrated using data on international input-output tables from 2014.

In a scenario that uses the UN mid-point estimates for population projections for 2030, population ageing leads to a strongly declining workforce in many countries compared to 2020 (Figure 1.2). This decreases GDP in Germany by 4.5% and leads to large output losses in almost all sectors and strong decreases in exports (Bickmann, Grundke and Smith, forthcoming[1]). Labour-intensive sectors such as textiles, construction and hospitality contract the most, but export-oriented manufacturing sectors are also strongly hit and decrease output and exports, such as electronic equipment, machinery, motor vehicles as well as minerals and metals (Figure 1.16). Raising net-immigration to around 600 000 per year, however, can significantly mitigate the adverse effects of ageing, provided that migrants are well integrated into the labour market (Figure 1.16). To maintain export competitiveness, attracting professionals with vocational skills is crucial. Machinery and equipment, electronics, mineral-metal and automobile industries, which account for over half of total exports (Figure 1.10), depend mostly on VET professionals for their production processes.

Figure 1.16. Labour shortages can be mitigated by higher levels of labour immigration

Changes in sectoral output, in % (compared to the baseline with working age population in 2020)

Note: The low migration scenario is based on the mid-point estimate of the UN World Population Prospects for 2030, which presumes an average yearly net immigration of around 130 000 in Germany. The higher migration scenario adds the average net migration for Germany observed in the past ten years, equal to around 500 000.

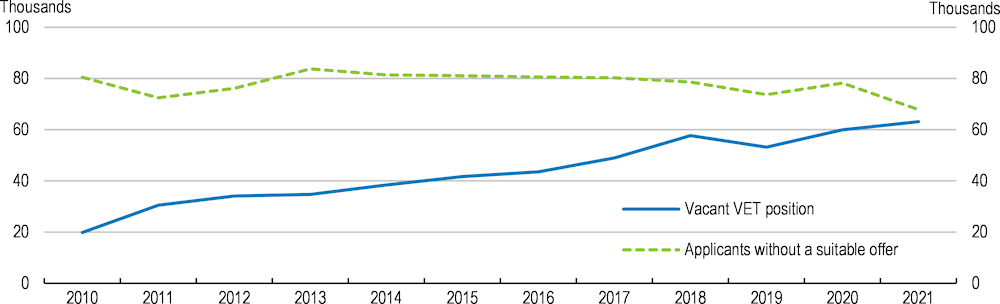

Better informing students in lower secondary education about occupations in high demand is also key to reduce skilled labour shortages. A rising number of VET positions remains unfilled, yet about 16% of applicants did not receive a suitable offer in 2021 (Figure 1.17). Vacancy rates are highest for many occupations in the construction and health sectors. To reduce the existing mismatch, it is key to improve the current VET transition system (Übergangsbereich), which supports young adults who have not succeeded in finding a VET position in a firm on their own. So far, several federal and state-level programmes coexist, with a lack of coordination, systematic information and guidance services (Enquete-Kommission Berufliche Bildung, 2021[44]). Furthermore, on-the job training needs to be strengthened in the transition system. An internship programme subsidised by the federal employment agency proved to be successful in matching VET applicants with employers and should be expanded (BIBB, 2022[45]; Enquete-Kommission Berufliche Bildung, 2021[44]). Implementing plans to guarantee every interested lower secondary student a VET position (Ausbildungsgarantie) in combination with personalised counselling services and mobility subsidies would be an important step forward. Moreover, unemployment rates among low-skilled adults without a professional degree are high, even for workers with job experience in sectors with severe labour shortages. This calls for better supporting low-skilled workers to start and complete a VET degree, for example by strengthening the recognition of prior learning and expanding the use of partial-qualifications and adult education opportunities (see Chapter 2). The social security reform (Buergergeld) is welcome, as it abolishes the obligation to prioritise job uptake and facilitates adult education and the completion of VET degrees, including by improving financial assistance.

Figure 1.17. A rising number of VET positions remains unfilled, yet many applicants do not receive a suitable offer

Note: The graph shows the number of vacant VET positions and applicants without a suitable offer at the end of the application cycle in each year (30 September).

Source: Datenreport zum Berfufsbilungsbericht 2022 (BIBB).

Better equipping children with the skills needed for the green and digital transition is another important policy lever to address future labour shortages and support potential growth (Figure 1.1, Table 1.1). Inequality in education outcomes is among the highest across OECD countries and has been exacerbated by school closures during the pandemic (DIPF, 2022[46]; OECD, 2019[47]). This is related to weak access to early-childhood education, particularly for children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Although special federal funds support municipalities to expand infrastructure for early-childhood education, many disadvantaged households have difficulties finding a place (Jessen, Schmitz and Waights, 2020[48]). This is because information and applications are not centralised within municipalities, selection is based on bilateral interviews, and access costs are high in some Laender (Hermes et al., 2021[49]). Raising subsidies for vulnerable households should be combined with centralising application procedures within municipalities and improving guidance. It is also key to address severe labour shortages in childcare and basic education, which risk reducing educational quality, by improving recruitment and training, and raising salaries (Bock-Famulla et al., 2022[50]). Weak targeting of support measures for disadvantaged school children is another important issue, which should be addressed by using more frequent learning evaluations to better target support, as for example successfully done in Hamburg. The federal EUR 2 billion fund to address pandemic-related learning losses is welcome but should be complemented by an evaluation of learning deficits and policy tools across Laender to improve spending efficiency and foster peer learning.

Table 1.5. Past recommendations and actions taken on training, education and labour market policies

|

Recommendations |

Action taken |

|---|---|

|

Prioritise early education by increasing spending on primary education, and improve foundational skills of VET graduates, for example by strengthening general education within the VET track or postponing between-school tracking. |

In the context of the pandemic-related stimulus package, the federal government has increased financial transfers to lower levels of government in 2020 and 2021 to improve access to and quality of early-childhood education. |

|

Increase ICT training for teachers to ensure effective use of ICTs. Introduce computational thinking earlier (particularly benefitting girls) while avoiding gender stereotypes in education and career guidance. |

No action taken. |

|

Strengthen support for unskilled adults to obtain professional qualifications. |

The 2023 reform of basic income support for jobseekers (introducing the new citizen’s benefit Buergergeld) is a major step forward. It prioritises training over job uptake and improves financial support for longer-term training and education courses for job seekers to obtain professional qualifications. It also aims to improve access to basic education for jobseekers. |

|

Provide financial incentives for employers to provide workplace learning for the low-skilled. |

The government plans to significantly improve financial support for employees to participate in adult learning and to obtain professional degrees. |

|

Facilitate participation of low-skilled individuals in adult education by taking further steps to validate uncertified skills, including those acquired-on-the job, and through workplace outreach. |

No action taken. The pilot project ValiKom has not been expanded so far. |

|

Improve transparency in the adult education market and facilitate access to guidance on adult training. Carefully monitor the outcome of financial support programmes for adult learning and education. |

A National Continuing Education Online Platform (“Nationale Online-Weiterbildungsplattform - NOW”) is being developed to increase transparency in and access to adult learning by providing appropriate information on courses, financing opportunities and skill needs in the labour market. The platform is planned to be launched in early 2024. |

|

Liberalise occupational entry conditions, prioritising sectors subject to supply constraints (such as construction) and preserving the strengths of the vocational education and training system. |

In 2020, the obligation to hold a master’s craftsman degree when owning a craftsman business was reintroduced in 12 occupations, which restricted entry conditions further. |

|

Scrutinise compulsory membership and chamber self-regulation in the professional services and crafts chambers for entry barriers and lower entry requirements where possible. |

No action taken. |

Modernising the state to support the green and digital transition

After a decade of fiscal surpluses and strongly decreasing public debt, the fiscal balance turned negative due to pandemic-related fiscal support (Table 1.6). The fiscal deficit is likely to remain high in 2023 due to energy price support, although falling retail energy prices would lead to a lower deficit as support measures are conditional on retail energy price levels (Box 1.2). If the announced volume of energy price support of more than 2.4% of GDP in 2023 materialises, an expansionary fiscal stance would risk further increasing core inflation (Figure 1.6) (Bundesbank, 2023[51]). To contain inflationary pressures, it is key to avoid an expansionary fiscal stance, while standing ready to further support vulnerable households if needed. Possible adjustments could comprise financing a larger part of the energy price support by cutting spending in other areas and raising tax revenue, for example by lowering the threshold above which the energy price subsidy is subject to personal income taxation. If energy price support is smaller than expected due to lower retail energy prices or if tax revenues are higher than expected in 2023, the additional resources should be used to reduce the fiscal deficit.

Table 1.6. The fiscal balance has turned negative during the pandemic

General government, % of GDP

|

|

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total revenues |

45.0 |

44.9 |

45.1 |

45.5 |

45.5 |

46.3 |

46.5 |

46.1 |

47.5 |

|

Taxes on production and imports |

10.9 |

10.7 |

10.8 |

10.7 |

10.6 |

10.6 |

10.6 |

10.2 |

10.9 |

|

Current taxes on income and wealth |

12.1 |

12.1 |

12.3 |

12.7 |

12.9 |

13.2 |

13.2 |

12.6 |

13.5 |

|

Social contributions received |

16.6 |

16.5 |

16.6 |

16.7 |

16.8 |

17.0 |

17.2 |

17.9 |

17.6 |

|

Capital taxes and other revenues |

5.4 |

5.6 |

5.4 |

5.4 |

5.2 |

5.4 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.6 |

|

Total expenditures |

44.9 |

44.3 |

44.1 |

44.4 |

44.2 |

44.3 |

45.0 |

50.4 |

51.3 |

|

Social protection |

19.0 |

18.8 |

19.1 |

19.5 |

19.4 |

19.3 |

19.6 |

21.6 |

20.9 |

|

Education and health |

11.4 |

11.5 |

11.4 |

11.4 |

11.3 |

11.4 |

11.6 |

13.0 |

13.2 |

|

General public services |

6.5 |

6.3 |

5.9 |

5.8 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

5.8 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

|

Economic affairs |

3.3 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

4.6 |

6.0 |

|

Other1 |

4.7 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

5.1 |

4.9 |

|

Net lending |

0.0 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.9 |

1.5 |

-4.3 |

-3.9 |

|

Primary balance |

1.4 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

2.6 |

2.1 |

-3.9 |

-3.5 |

|

Gross debt |

84.0 |

83.8 |

79.8 |

77.1 |

72.3 |

69.1 |

67.5 |

78.5 |

77.6 |

|

Gross debt, Maastricht definition |

78.2 |

75.2 |

72.0 |

69.1 |

65.1 |

61.8 |

59.5 |

68.9 |

69.4 |

|

Net debt |

44.0 |

43.6 |

40.0 |

37.7 |

33.1 |

30.2 |

27.1 |

32.2 |

30.7 |

1. Defence; public order and safety; housing and community amenities; recreation, culture and religion; environment protection.

Source: OECD National Accounts database; Economic Outlook database.

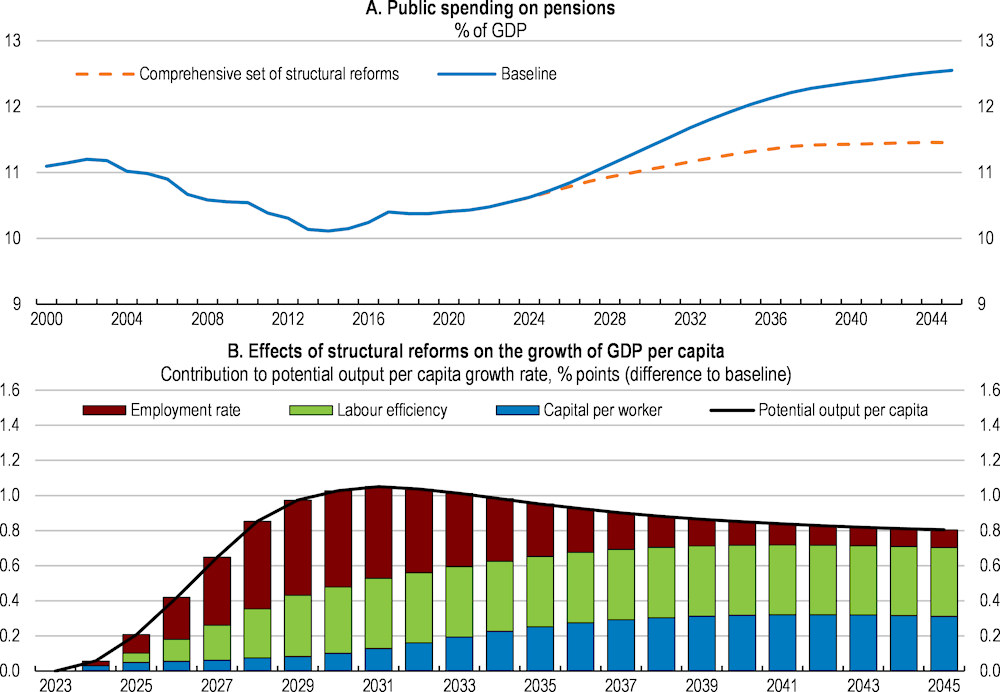

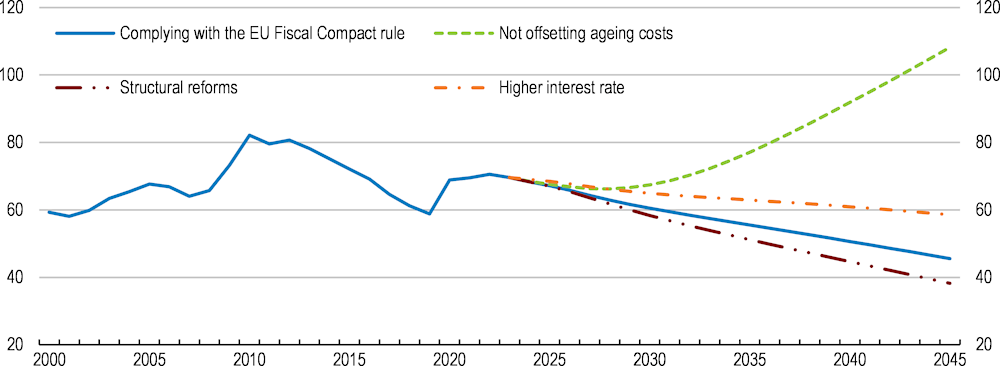

In the medium term, it is crucial to address rising fiscal pressures from ageing to maintain fiscal sustainability. This will require structural reforms to address skilled labour shortages and raise productivity (Figure 1.18, Figure 1.3, Table 1.1). Moreover, offsetting ageing-related costs while preserving fiscal space to address high investment needs in times of rising interest rates and adverse economic effects of the war of Russia against Ukraine will also require better prioritising spending, increasing spending efficiency, reducing tax expenditures and strengthening tax enforcement (Table 1.7). Reducing labour taxes, particularly for low-income and second earners, should be financed by reducing tax expenditures and strengthening tax enforcement, while not raising the overall tax burden. As reaching net zero in 2045 will significantly reduce revenue from environmental taxes, which amounted to about 2.6% of GDP in 2022, further adjustments in the tax mix will be necessary, for example by raising property taxes (see below) (Baer et al., 2023[7]). On the spending side, significant fiscal space can be created by better prioritising spending and raising spending efficiency across levels of government, which can be used to finance important investment needs in infrastructure and innovation as well as to improve the quality and access to education and training. Importantly, these investments in physical and human capital will raise potential growth in the medium and long term, reducing their total fiscal costs and creating additional fiscal space by 2045 (Table 1.1, Table 1.7). This will help to mitigate the strongly rising fiscal pressures due to ageing, as pension and health related spending is estimated to increase by about 4.6 percentage points of GDP until 2045 (Figure 1.2, Figure 1.18).

Figure 1.18. Addressing the fiscal effects of ageing is key to safeguard fiscal sustainability

Gross government debt, % of GDP (Maastricht definition)

Note: The scenario “Complying with the EU Fiscal Compact rule” uses the projected growth path from the OECD Long-Term model and assumes that the structural fiscal deficit reaches 0.5% of GDP in 2026 and is constant thereafter. The scenario “not offsetting ageing related costs” builds on the previous scenario, but assumes that ageing related additional costs in pension, health and long-term care systems are not offset and deteriorate the primary fiscal balance by 4.6 percentage points until 2045. The “Structural reform scenario” shows the effect of a comprehensive set of structural reforms on public debt (Table 1.1). The scenario “Higher interest rates” raises interest rates by 1 percentage point during the projection horizon.

Source: OECD Long term model.

Table 1.7. Potential fiscal impact of OECD recommendations

|

Recommendation |

Short-term fiscal impact (in percentage points of GDP) |

Long-term fiscal impact (in percentage points of GDP) in 2045 |

|---|---|---|

|

Tax revenue related recommendations |

||

|

Reduce the labour tax wedge, in particular for low-income and second earners, and reform the joint taxation for couples |

-1.4 |

-0.9 |

|

Abolish tax expenditures for income from selling or renting real estate |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

Reduce generous allowance thresholds for gift and inheritance taxes and reduce exemptions for business assets |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Use the ongoing update of property values to better link property taxation to asset values and raise revenue |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Reducing VAT exemptions and improving tax enforcement |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

Reduce environmentally harmful tax expenditures |

0.4 |

0 |

|

Total fiscal impact tax revenue measures |

0.0 |

0.1 |

|

Spending related recommendations |

||

|

Reduce environmentally harmful subsidies |

0.1 |

0.0 |

|

Strengthening spending reviews in budgeting procedures and raise spending efficiency through better impact evaluation and policy targeting at all levels of government |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Improving public procurement procedures at all levels of government |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Expand active labour market policies and improve adult education |

-0.1 |

0.3 |

|

Raise public investment in infrastructure and R&D |

-1.0 |

-0.5 |

|

Improve educational quality and access to childcare and early-childhood education |

-0.2 |

-0.1 |

|

Total fiscal impact spending related measures |

0.1 |

1.0 |

|

Total fiscal impact of revenue and spending related measures |

0.1 |

1.1 |

Note: The effects of reforms related to prioritising spending and raising spending efficiency at all levels of government are difficult to quantify using available methodologies, but would significantly contribute to increasing fiscal space. The estimate for the fiscal impact of improved public procurement procedures is derived from an OECD study which has estimated the gains in spending efficiency to be about 1 percentage point of GDP, if risk assessment and analysis of market capacity for infrastructure contracting decisions are improved across all levels of government by applying the OECD Support Tool for Effective Procurement Strategies (STEPS) (Makovšek and Bridge, 2021[52]; OECD, 2021[53]).

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Long-Term Model.

Updating the fiscal policy framework

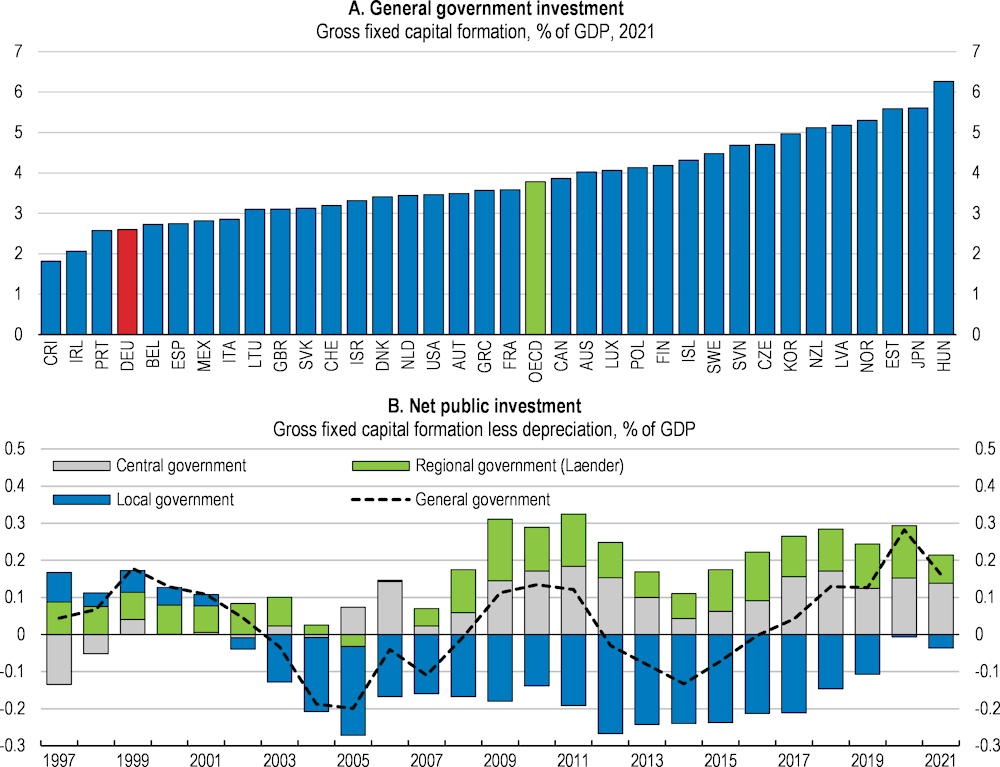

Since the 2000s, weak public investment has led to a large investment backlog in education, transport and digital infrastructure (see the previous OECD Economic Survey of Germany). The net capital stock has strongly declined since 2003, especially in municipalities, which are responsible for school and transport infrastructure. During the pandemic, many schools were not equipped with the necessary digital infrastructure to continue classes online, causing average learning times to drop more than in other European countries (Freundl, Stiegler and Zierow, 2021[54]). School closures had strong negative consequences on skills development, particularly among children from disadvantaged households, adding to existing structural weaknesses in basic education, increasing inequality and lowering future growth potential (see above) (Fuchs-Schuendeln, 2022[55]; DIPF, 2022[46]).

Figure 1.19. Public investment has increased, but remains low